Families of schizophrenics

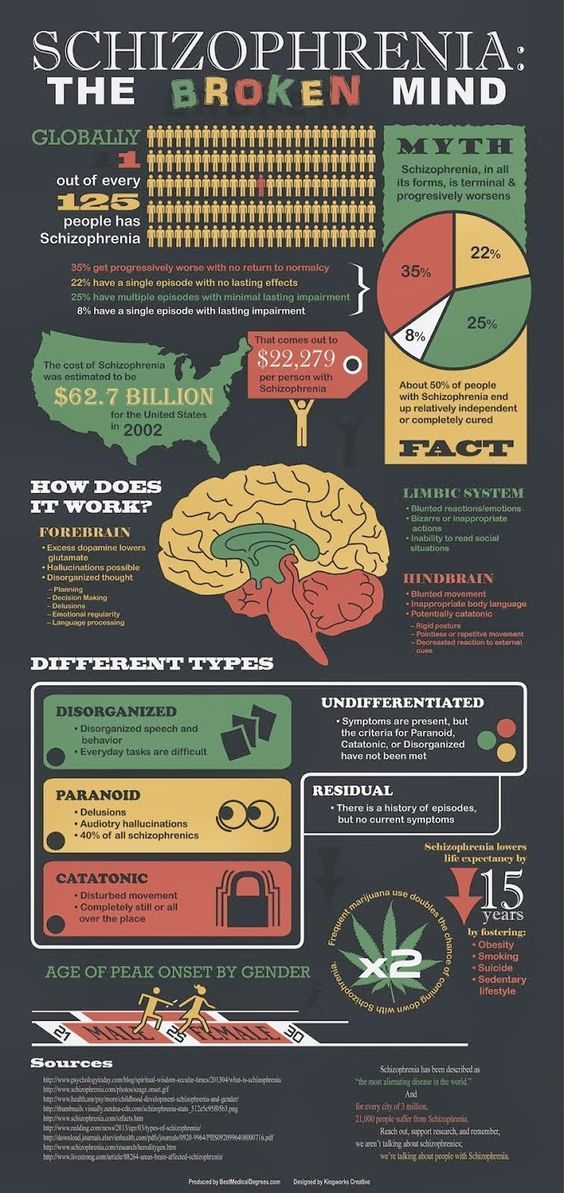

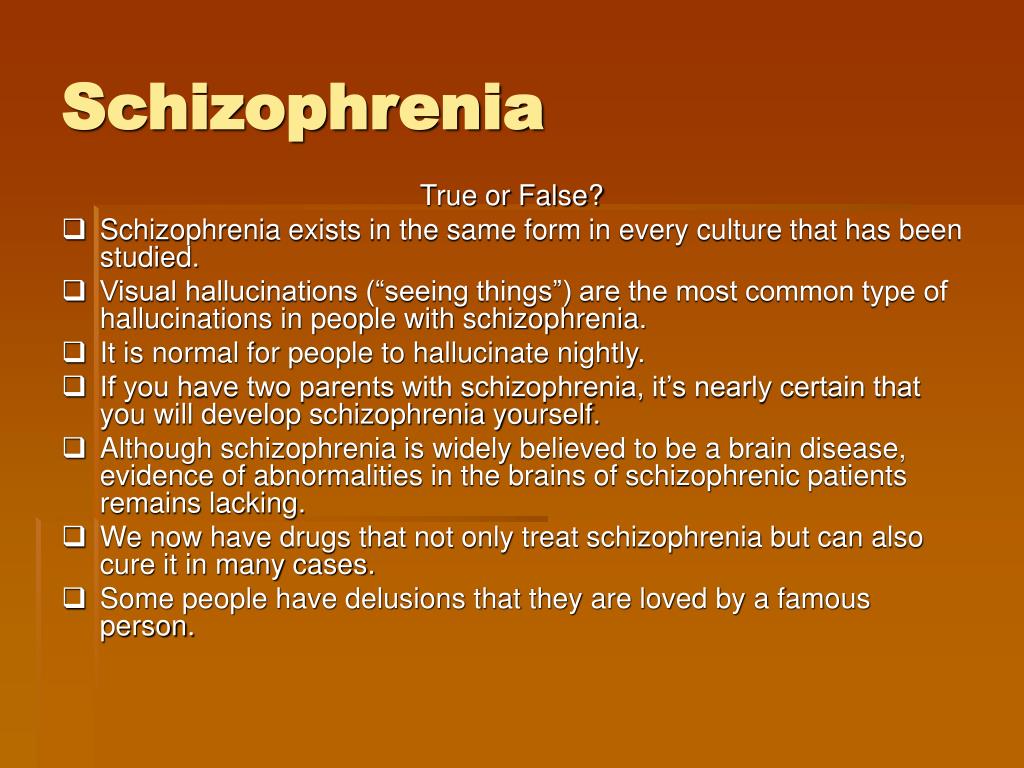

Schizophrenia

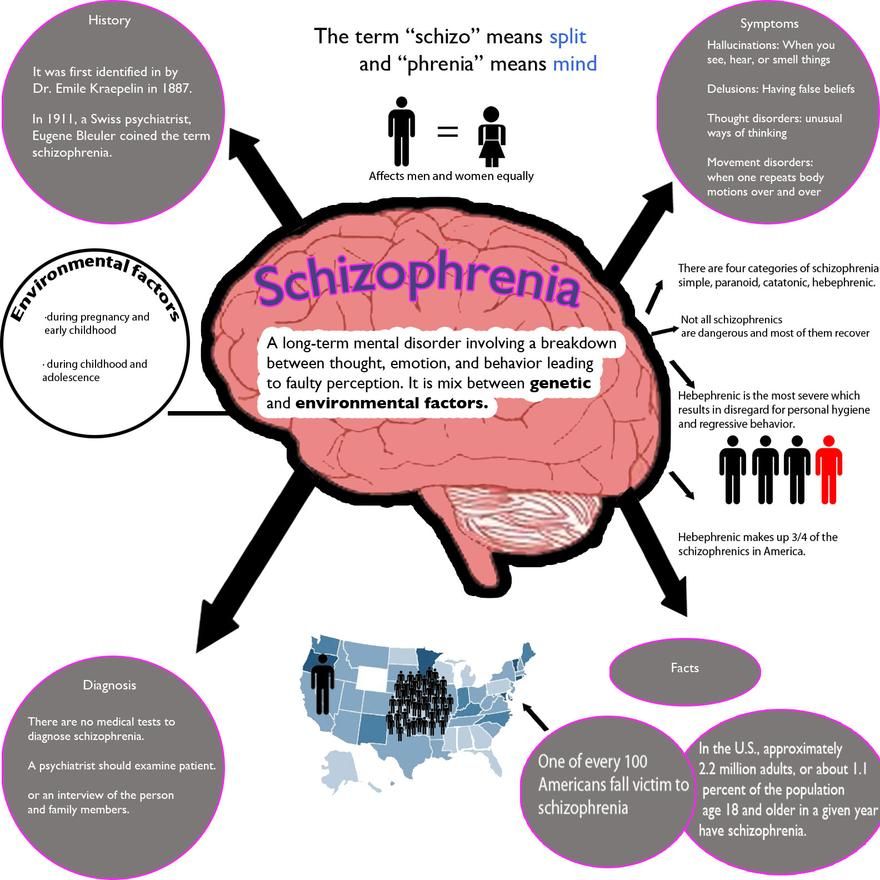

Schizophrenia is a severe and persistent mental disorder that affects 1% of the population. The disorder is marked by the distortion of experiences, thoughts, and feelings, and often weakens the ability to function in such areas as education, work, interpersonal relations, and self-care. Schizophrenia poses significant challenges for both clients and families.

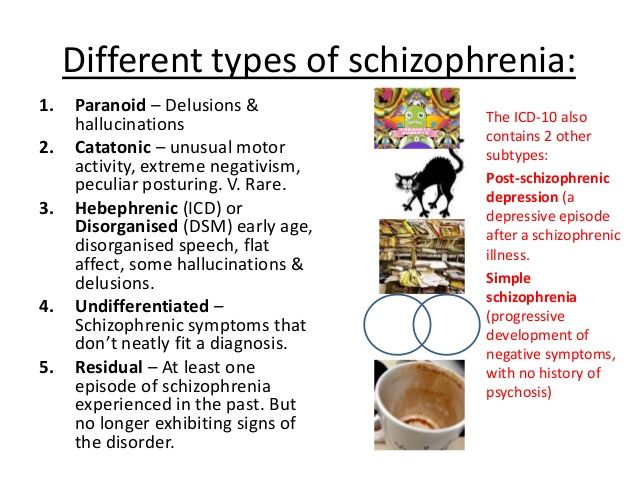

What are the symptoms of schizophrenia?

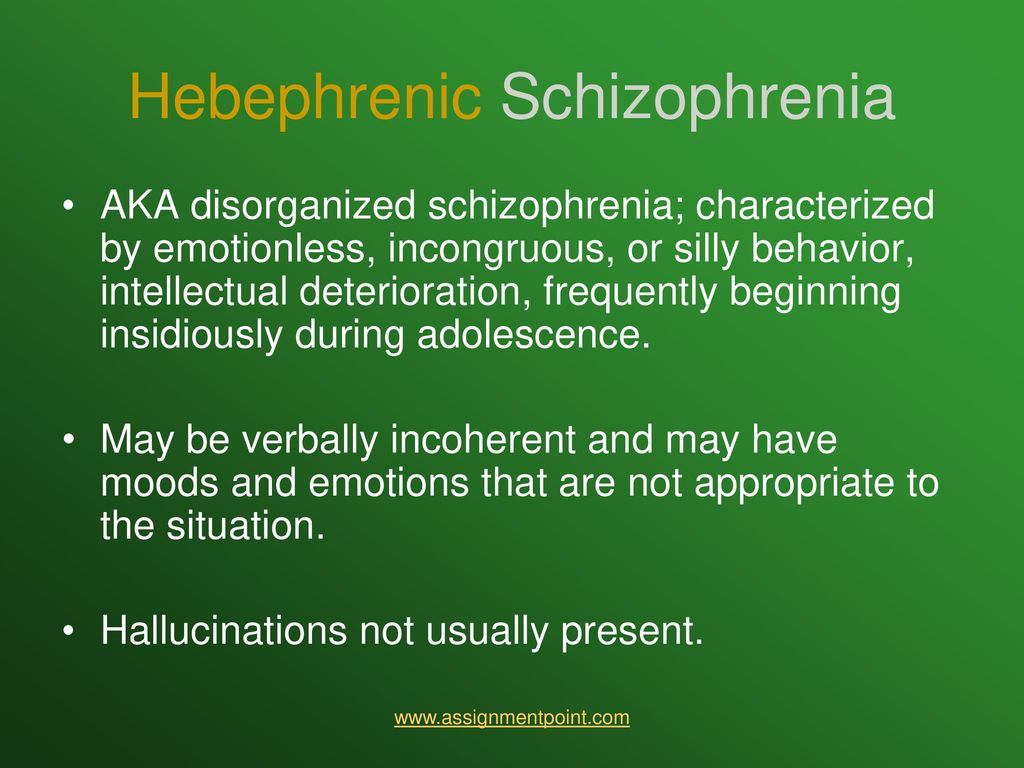

Schizophrenia is characterized by a wide range of "positive" and "negative" symptoms. Positive (psychotic) symptoms-those that occur in people with schizophrenia but not in others-include:

- hallucinations (false perceptions), such as hearing voices

- delusions (false beliefs), such as a conviction that one is being persecuted

- disorganized thinking or speech

- bizarre behavior

"Negative" symptoms-those that are absent in people with schizophrenia but present in others-may also occur, including:

- apathy and inability to follow through on tasks

- inability to experience pleasure and to enjoy relationships

- inability to feel and express emotions

- inability to focus on activities

- impoverished thought and speech

Schizophrenia frequently causes problems in social and cognitive functioning. For instance, people with the disorder may experience problems communicating with others and maintaining attention and concentration.

What causes schizophrenia?

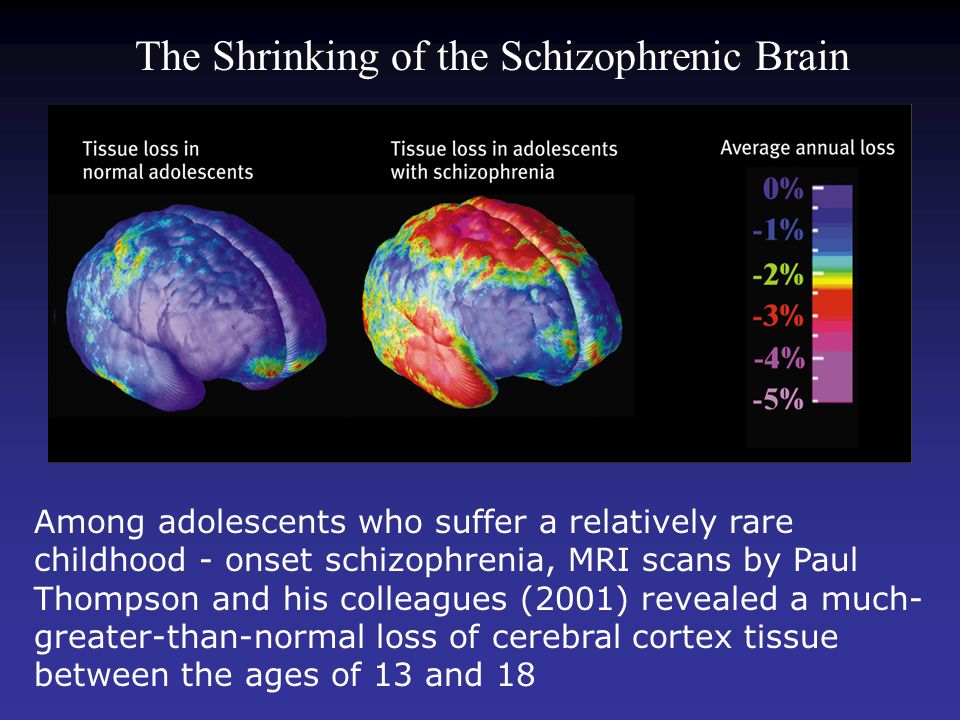

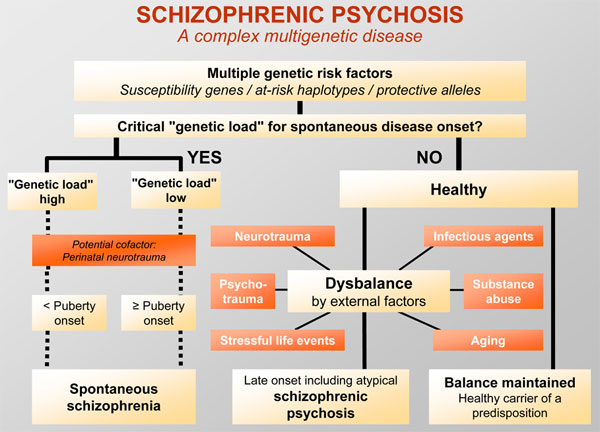

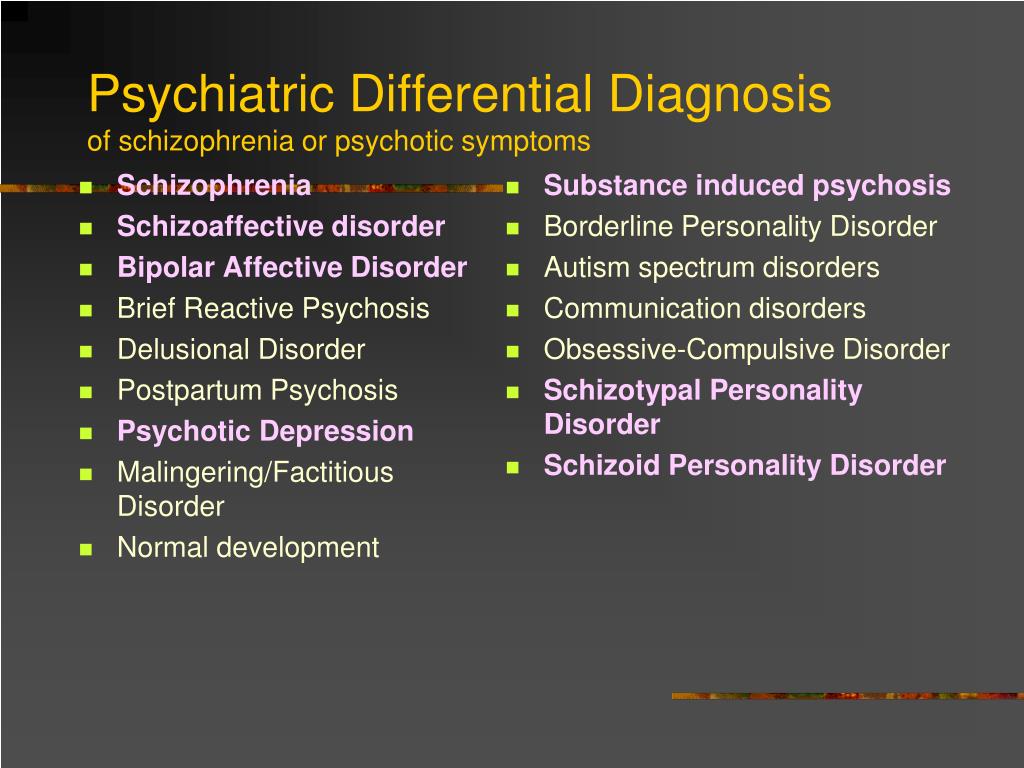

Schizophrenia is associated with abnormalities in brain activity, chemistry, and structure. Approximately one third of people with schizophrenia have a family history of the disorder. Many other biological, psychological, and social factors may also play a role. In fact, there is much that we don't know about schizophrenia-and what we do know points to its enormous complexity.

There is considerable agreement among professionals that schizophrenia involves a vulnerability (or biological predisposition) to develop certain symptoms and that a range of factors can interact with this vulnerability to affect the course of the illness. Some factors, such as substance abuse, are associated with worsening of symptoms and increased likelihood of relapse. Other factors, such as the treatments mentioned below, can improve the symptoms of the illness and make relapse less likely.

In fact, over time and with effective treatment, approximately two thirds of individuals with schizophrenia experience significant recovery and go on to establish satisfying and productive lives in their community. In recent decades, we have greatly increased our understanding of schizophrenia and its treatment. As a result, practitioners can now offer genuine assistance to clients and their families.

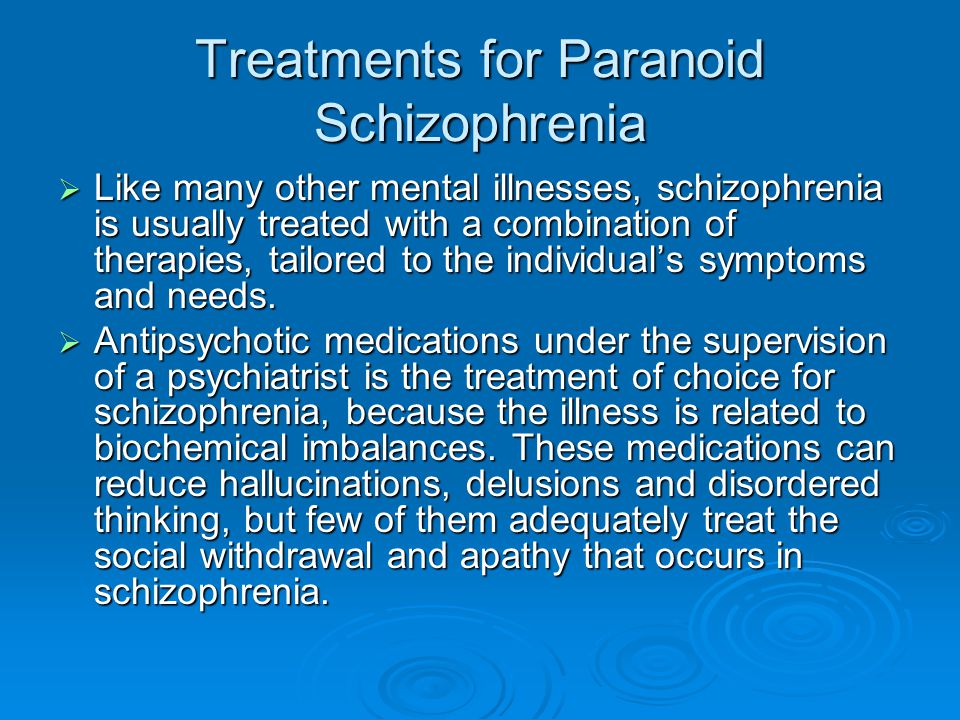

What are the treatments for schizophrenia?

Many effective treatments are now available for schizophrenia. These treatments can result in reduced symptoms, decreased relapses and hospitalizations, improved quality of life, and increased ability to function in home, school, work, and leisure settings. Effective treatments for schizophrenia include:

- a new generation of antipsychotic medications that have fewer unpleasant side effects and that are more effective in treating the positive and negative symptoms of schizophrenia and in reducing the risk of relapse

- Assertive Community Treatment that offers services in the community, on a 24-hour basis, by a multidisciplinary treatment team

- supported employment that assists clients to obtain jobs at competitive wages in normal work settings

- training that assists clients to improve their social skills and manage their illness

- cognitive interventions that help clients cope with persistent symptoms and with limitations in attention, memory, and other cognitive functions

- integrated mental health and substance abuse treatment

- family interventions designed to reduce the client's risk of relapse and re-hospitalization, and to address the needs of families themselves

How does schizophrenia affect families?

Schizophrenia has a devastating impact on all members of the family. For example, family members usually need to cope with:

For example, family members usually need to cope with:

- their caregiving responsibilities

- their own emotional distress

- the symptoms of schizophrenia

- increased stress and disruption

- the mental health system

- social stigma

As caregivers, families share three essential needs: for information about schizophrenia and the mental health system, for skills to cope with the disorder and its consequence for their family, and for support for themselves. Of course, each family has unique concerns and needs, which are likely to change through time. Even within a given family, the needs of individual members differ for parents, spouses, siblings, and offspring of people with schizophrenia. Communities differ as well. Some communities offer excellent services for clients and families, while others offer relatively few.

What services are available for families?

Many services can assist families to cope with schizophrenia. These include:

These include:

- consultation with professionals who can assist them to deal a with a wide range of illness-related concerns

- short-term educational programs, which provide information about schizophrenia and its treatment, caregiving and management issues, and the mental health system and community resources

- long-term psychoeducational programs, which offer support, education, and skills training in stress management, communication, and problem solving

- individual, marriage, family, or group therapy to help family members resolve illness-related concerns and deal with other family issues

- family support and advocacy organizations, such as NAMI (the National Alliance for the Mentally Ill), which offers ongoing support groups and a 12-week Family-to-Family Education Program

A Marriage and Family Therapist can assist families to identify their most pressing needs and to make an informed choice about their use of services. In addition, therapists can offer consultation, education about mental illness, and skills training. All of these services can assist family members to gain insight into the meaning of schizophrenia for themselves and their families, to learn more effective methods of coping, to reduce their level of distress, to develop more positive feelings about themselves and their future, and to obtain support in creating a more fulfilling life.

In addition, therapists can offer consultation, education about mental illness, and skills training. All of these services can assist family members to gain insight into the meaning of schizophrenia for themselves and their families, to learn more effective methods of coping, to reduce their level of distress, to develop more positive feelings about themselves and their future, and to obtain support in creating a more fulfilling life.

How can families help?

Families can play important roles in their relative's treatment, rehabilitation, and recovery. For instance, people with schizophrenia may have difficulty maintaining attention and processing information, so families need to practice good communication skills. Likewise, because schizophrenia is associated with unusual vulnerability to stress, families can help their relative by maintaining a supportive environment and by resolving family problems in a constructive manner. The course of schizophrenia is typically marked by alternating periods of remission and relapse, so families also need to learn and respond to the signs of impending relapse. In fact, professionals now believe that a majority of relapses can be prevented.

In fact, professionals now believe that a majority of relapses can be prevented.

Here are some other suggestions:

- Learn about schizophrenia and community resources.

- Assist your relative to obtain effective treatment.

- Develop skills for coping with schizophrenia.

- Understand the meaning of the illness for your family.

- Obtain services that can meet your family's needs.

- Strengthen your own support network.

- Focus on the strengths of your relative and your family.

- Develop realistic expectations.

- Create a balance that meets the needs of all family members.

- Maintain a hopeful attitude.

For family, online, and more

We include products we think are useful for our readers. If you buy through links on this page, we may earn a small commission. Here’s our process.

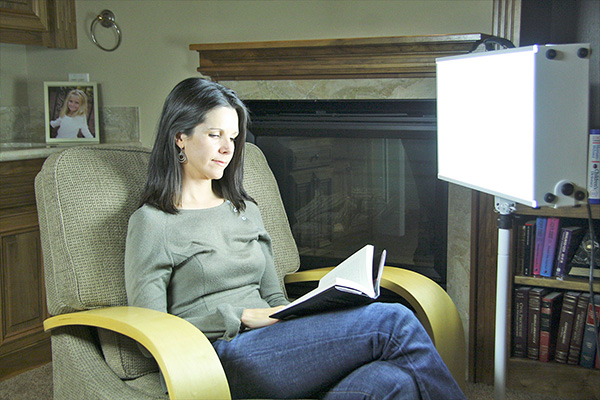

Support groups for people with schizophrenia can foster a sense of connection and community and help a person cope with their condition. They may also improve functioning, reduce the duration of rehospitalizations, and prevent relapses.

Schizophrenia is a chronic mental health condition that causes people to experience distortions of reality, including delusions or hallucinations.

People with schizophrenia may also:

- have difficulty concentrating and communicating

- have difficulty with schoolwork or employment

- isolate themselves from friends and family

Symptoms often start during a person’s teenage years and early 20s. Without treatment, schizophrenia can be disabling.

Several treatments can help people manage their symptoms so that they can function better in their day-to-day lives.

Schizophrenia support groups are one vital treatment option that may offer a sense of community, important coping skills, and improved outcomes.

Support groups are spaces where people who share a common condition or life situation can come together to share their stories and experiences with others so that they feel less isolated.

They may be led by members of the community, nonprofits, or mental health professionals.

Support groups can be held:

- in person

- over the phone

- via text or messenger app

- via smartphone applications

- online, with:

- discussion boards (forums)

- blogs

- virtual communities

In addition to antipsychotic medications, support groups are essential forms of treatment for schizophrenia.

Support groups may help members:

- feel a sense of connection and community

- learn more about how to cope with their condition

- get tips about treatment options

- ask others for advice or help

- grow their social network

Family-led mutual support groups can be crucial to treating schizophrenia. They aim to lessen the burden of schizophrenia within the family and among caregivers.

They aim to lessen the burden of schizophrenia within the family and among caregivers.

In family therapy, caregivers and families work with a therapist to better understand schizophrenia and develop ways to communicate with their loved ones.

This kind of therapy also offers support for family members and caregivers. Taking care of someone with a mental health condition can be stressful and require a lot of time and energy.

The objectives of family support are to:

- provide education and information to better understand schizophrenia

- encourage an atmosphere of mutual trust

- explore strategies for coping with stress

- provide an atmosphere conducive to open, honest sharing of feelings

- discover ways to meet the needs of the person with schizophrenia

- understand how to overcome stigma and foster hope

- learn about services available in the community

Support groups can foster a sense of connection and community and may help a person with schizophrenia better cope with their condition.

Other benefits include the following:

- Peer support groups: These are useful interventions for people with psychiatric disorders. Some studies show that they enable and strengthen relationships in people with mental health conditions such as schizophrenia.

- Online emotional support: This is delivered by trained volunteers and may have many advantages, including the anonymity of the messaging system and the nonjudgmental approach of the volunteers.

- Family-led support groups for schizophrenia: These may help improve functioning in people with schizophrenia. They can provide long-term benefits, including:

- preventing relapse

- improving family functioning

- providing social support

- reducing people’s symptom severity

- reducing the length of rehospitalizations

Several organizations offer affordable family support. These include:

- family and caregiver schizophrenia support forums

- National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) family support groups

- NAMI’s Family-to-Family program, a free, eight-session educational program for family and friends of people with mental health conditions

Online psychotherapy is easily accessible and often more affordable than in-person programs.

Here are a few ways that people with schizophrenia can connect with others online:

- Mental Health America offer their own support group through a platform called Inspire.

- The Schizophrenia & Related Disorders Alliance of America offer a variety of online groups and chats for people with schizophrenia as well as their family and friends.

- 7cups offers online chats and other group resources.

- The NAMI Connection Recovery Support Group offers free, peer-led support for adults with mental health conditions.

It is also possible to also talk with mental health professionals online. Online therapy may cost less than conventional in-person therapy.

Here are a few ways to connect with a professional:

- BetterHelp

- TalkSpace

- Amwell

- 7cups

It sometimes requires trial and error to find the support group or therapist that is right for a person and their family.

Support groups can help people with schizophrenia achieve independence and grow personal relationships. They are also a tool for families to explore strategies for coping with stress and learn ways to better meet the needs of their loved ones with schizophrenia.

They are also a tool for families to explore strategies for coping with stress and learn ways to better meet the needs of their loved ones with schizophrenia.

Online support groups are becoming increasingly available as an affordable option. Healthcare professionals also offer online therapy sessions that may be more affordable and can take place in the comfort of one’s own home.

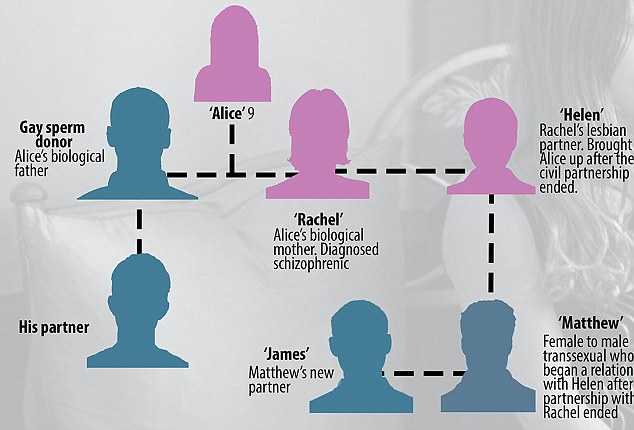

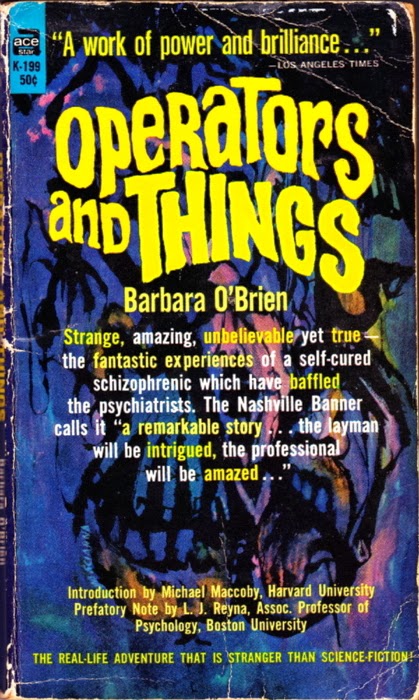

The story of schizophrenia in a model family: an excerpt from the book "Something Wrong with the Galvins"

7 October 2021, 09:45

Article

Fragments of new books

Researchers have long believed that this disease is genetic and inherited. However, it was the study of this case that led to the opposite conclusions, because the parents were absolutely mentally healthy. They tried to pay equal attention to all children, give them a good education, played music and sports with them. But, despite all this, in the end they could not prevent the sad development of events in any way and were forced to helplessly watch the illness of their children.

"Something Wrong with the Galvins. An Ideal Family Destroyed by Madness" (Bombora Publishing House) by American journalist Robert Kolker is a book about the history of this family, about how Don and Mimi noticed for the first time that something was wrong with their son as they tried to deal with it. In parallel, the book tells about how the study of the disease took place, what methods were used to treat patients, and what results the study of the Galvin case led to. Read a short passage about Jim, the second son of Don and Mimi, who suddenly began to hear voices and show aggression towards his wife Kathy.

Read also

Is it possible to contract depression and schizophrenia? In a sense, yes

After studying in Boulder for about two years (and becoming a regular at several of the local bars), Jim met Cathy. He was twenty, she was nineteen. He drew attention to her at a dance at Giuseppe's restaurant. She came with a classmate friend, and Jim asked permission to join them. Then he called her at home (she lived with her parents), and they began to meet.

She came with a classmate friend, and Jim asked permission to join them. Then he called her at home (she lived with her parents), and they began to meet.

From the very beginning, Cathy noticed Jim's dislike for his parents. "So many children have been cut that they can't cope with the little ones," he once said. He also liked to complain about his hated older brother - they say that he was considered a hero in high school, and they took me for some kind of half-wit. The girl decided that all this, probably, was already in the past for him, at least it should have become one.

When Cathy became pregnant, Jim did not hesitate to ask her to marry him. Such an outcome hardly looked ideal from the point of view of Don and Mimi, although, in truth, at Jim's age, they themselves did almost the same thing. In any case, it was useless to say anything. This is Jim, who will definitely do what he wants. In addition, they had just blessed Donald's marriage, and they had no weighty arguments left.

The wedding took place in August 1968, a year after the wedding of Donald and Jean. The newlyweds settled in a small one-story red brick house in the city center. From time to time they invited the Jim brothers to visit - everyone except Donald, just not Donald. Cathy got along well with her younger brothers Galvin, but she had a strained relationship with Jim's mother. Mother-in-law's visits were more like inspections. "You haven't dusted," Mimi said, to which Cathy replied, "I don't have time. There's a rag over there if you want to get busy." Jim was delighted with such dialogues. Katie gave birth to a son, Jimmy, who was only a couple of years younger than Mary, Mimi's youngest daughter. Jim dropped out of school and began working as a bartender at parties. This did not fit in with his former goal of becoming a teacher, like his father. But the main thing was different: now Jim became the father of the family and believed that he had surpassed Donald in all respects. Having landed a full-time job as a bartender at the Broadmoor Hotel, one of the city's most prestigious locations, he felt like a clear winner.

Jim enjoyed his role as husband and father, but never missed an opportunity to break his marriage vows. Being an incorrigible womanizer before marriage, he saw no reason to improve in this regard after her.

Read also

It seems that people have two selves, and one gives meaning to life. Excerpt from a book about dying

One evening Cathy noticed his motorcycle at the entrance to a bar. She went in, saw Jim and his girlfriend, poured beer over them from a carafe on the table, and left. She wanted Jim to understand that she had her own pride. Jim got even with her later, when they were alone. Hearing that Cathy had quit her job and wanted to continue her teacher education, he removed the spark plugs from the car's engine to prevent her from going to school. "Go to work," he said. When Cathy arranged for her mother to pick her up, he waited for her to return and slapped her.

Jim became more and more aggressive, and Cathy realized that it was better not to threaten him with leaving. Once she tried it and got hit in the head so hard that she needed stitches. Besides, she couldn't bring herself to carry out that threat. Every time she was on the verge of leaving, she thought that Jim could improve and that their son needed a father. On the rare occasions when Katie got up the nerve to leave home for a day or two, Jimmy would whine, "I want to go home to my dad."

Once she tried it and got hit in the head so hard that she needed stitches. Besides, she couldn't bring herself to carry out that threat. Every time she was on the verge of leaving, she thought that Jim could improve and that their son needed a father. On the rare occasions when Katie got up the nerve to leave home for a day or two, Jimmy would whine, "I want to go home to my dad."

There was another reason Katie didn't want to leave him. She began to notice that Jim was tormented by something that had nothing to do with her, and this made her feel something like pity for him. He heard some voices. "They were talking to me again," Jim whispered. In a stifled voice from overflowing emotions, he talked about them - some people who spy on him, follow on his heels and plot intrigues at work.

Jim stopped sleeping. All night long he stood at the gas stove, turning the oven on and off and on again. In such states, he was capable of reckless and ruthless acts not in relation to Cathy and his son, but to himself.

While walking through downtown Colorado Springs, Jim suddenly started banging his head against a brick wall. On another occasion, he dived into the pond fully clothed. The first time Jim was hospitalized for a psychotic break was on Halloween Eve 1969, when Jimmy was still an infant. He was admitted to the hospital of St. Francis, from where he fled the very next day. Katie was afraid for herself and for her son, but she was afraid for Jim too. Yet he was the husband, the father of her child, and leaving him now seemed unthinkable.

See also

US Air Force patents DNA test for intelligence. Ahead of the future, they bring back the gloomy past

Jim's parents never liked Katie (which was fine with Jim himself), but she knew she needed to tell Don and Mimi about what had happened. Their reaction startled her. She expected to see tears, compassion, or at least understanding. Instead, two people sat in front of her, desperately trying to pretend that they did not hear anything special, and in response to the insistence on continuing the conversation, they questioned its essence. Did it really happen exactly as Kathy said? Jim's parents were completely unwilling to accept that their son was in trouble or even in danger. On the contrary, they presented what happened as a marital problem of a young couple, which Jim and Kathy should try to solve on their own. Perhaps most notable, at least in retrospect, was Don and Mimi's silence about Jim's brother Donald acting weird too. They did not tell anyone about the eldest son and were not going to share this with Cathy.

Did it really happen exactly as Kathy said? Jim's parents were completely unwilling to accept that their son was in trouble or even in danger. On the contrary, they presented what happened as a marital problem of a young couple, which Jim and Kathy should try to solve on their own. Perhaps most notable, at least in retrospect, was Don and Mimi's silence about Jim's brother Donald acting weird too. They did not tell anyone about the eldest son and were not going to share this with Cathy.

After talking to Don and Mimi, Cathy, on their advice, took Jim to the priest, but it was no good. One evening, when Jim seemed completely helpless, Kathy finally took him to the University of Colorado Hospital in Denver. He stayed there for two months and returned home. Jim agreed to receive outpatient care at Pikes Peak Asylum in Colorado Springs. The doctor gave him medication, and his condition remained stable long enough to give him some hope.

Only from time to time he lost his temper and beat Cathy again. One day a policeman came to see them, but Cathy refused to prosecute. On another occasion, policemen called by neighbors escorted Jim out of the house.

One day a policeman came to see them, but Cathy refused to prosecute. On another occasion, policemen called by neighbors escorted Jim out of the house.

True, after a while he returned. Jim always came back, no matter what happened. In later years, Don and Mimi never interfered. “Except for the cases when Jim dumped and returned to live with them, which suited me very much. Well, then he reappeared on the threshold of my house,” recalls Cathy.

See also

A brief history of the "improvement" of humans and the human race. Eugenics before and after the Nazis

On a spring day in 1969, all twelve of the Galvin children gathered in a relatively peaceful and friendly atmosphere to honor their father in a ceremony at the University of Colorado. At the age of forty-four, Don finally received his degree. The picture taken that day is perhaps the only photograph in which all twelve children and both of their parents are present. Don with already touched with gray hair in a mantle and an academic cap. Next to him is Mimi with slicked back hair, in a cream spring dress with a bright yellow scarf. In front of their parents are the girls, Margaret and Mary, in identical white dresses. And on the right, all ten boys lined up in two rows, like skittles.

Next to him is Mimi with slicked back hair, in a cream spring dress with a bright yellow scarf. In front of their parents are the girls, Margaret and Mary, in identical white dresses. And on the right, all ten boys lined up in two rows, like skittles.

Fourth from the left in the second row is Jim with tousled dark hair and a pale sweaty face. In the future, Mimi will show this photo more than once, saying that in that one of the last carefree happy days of the family, she first realized that Jim was in big trouble - now he is not just a rebel, as he always was, but a madman. Like Donald.

Tags:

Fragments of new books

Mothers of patients with schizophrenia: medical and psychological aspects of the problem. Literature Review | Mrykhina

Schizophrenia: relevance of the problem, prevalence, burden, problems of treatment

Schizophrenia is one of the central problems of modern psychiatry. Its prevalence is from 0. 3 to 2.0%, primary incidence is from 0.3 to 1.2% [1].

3 to 2.0%, primary incidence is from 0.3 to 1.2% [1].

Schizophrenia affects any age category of the population, 90% of patients are persons aged 15 to 55 years. Patients with schizophrenia occupy about 50% of the beds in psychiatric hospitals; they are also the main contingent in the provision of outpatient psychiatric care [2]. Schizophrenia is among the ten diseases with the highest disability, more than 90% of patients with this pathology are disabled [3]. Schizophrenia is a burden on society: in the WHO general list of economic losses from diseases, calculated using the DALYs (Disability-Adjusted Life Year) index, in the age group from 15 to 44 years, schizophrenia ranks 8th (2.6%), ahead of coronary disease heart disease, cerebrovascular disease and the medical consequences of wars. The direct economic costs associated with it amount to 0.2–0.25% of GDP, indirect ones are estimated at least three times higher [2][4]. Schizophrenia is associated with deterioration in social cognition, social isolation is common, difficulties in work, problems with long-term memory and attention are common [5]. In some forms of schizophrenia, the function of speech may be impaired, gross motor impairments may occur [6].

In some forms of schizophrenia, the function of speech may be impaired, gross motor impairments may occur [6].

It is noteworthy that puberty is a critical period for the onset of schizophrenia. In 38% of men and 21% of women diagnosed with schizophrenia, the disease debuted before the age of 18 [6]. Patients diagnosed with schizophrenia may experience both psychotic symptoms and nonspecific manifestations of social isolation, irritability, and dysphoria [7].

The effectiveness of treatment and rehabilitation measures for schizophrenia remains insufficient, a significant proportion of patients are socially unadapted. Modern concepts of providing psychiatric care note the important role of social adaptation and social rehabilitation in the complex of therapeutic and preventive measures for schizophrenia [8]. However, despite the intensification of scientific research in this direction in recent years, the issues of social rehabilitation and readaptation of patients with schizophrenia remain one of the most vulnerable areas of the psychiatric care system. The system of rehabilitation of patients with schizophrenia that exists today is largely formalized, impersonal, does not take into account the depth of the patient's social maladjustment and the characteristics of his social functioning and, as a result, has low efficiency [9].].

The system of rehabilitation of patients with schizophrenia that exists today is largely formalized, impersonal, does not take into account the depth of the patient's social maladjustment and the characteristics of his social functioning and, as a result, has low efficiency [9].].

The basis for providing a complete and adequate assessment of the mental state and psychosocial adaptation of patients is the technology of determining a functional diagnosis, which reflects the clinical and functional characteristics of the patient.

The study of the state of individual system integration of the patient's biopsychosocial features using functional diagnosis makes it possible to qualitatively assess the features of the schizophrenic process in the context of the pathodynamic, psychological and social components, which makes it possible to determine the completeness of the patient's adaptation to the environment.

The general principles of functional psychiatric diagnosis were laid down by V. A. Abramov, S. A. Putsa, and I. I. Kutko. [10], who believed that a functional diagnosis is an assessment of the result of the patient's awareness and intellectual processing of the pathological process, the resulting social situation, individual adaptation and interaction of the patient with the social environment. However, unfortunately, this technology has not been widely implemented in the actual clinical practice of psychiatry, remaining an additional mechanism that psychiatrists used at their own request and at their own discretion.

A. Abramov, S. A. Putsa, and I. I. Kutko. [10], who believed that a functional diagnosis is an assessment of the result of the patient's awareness and intellectual processing of the pathological process, the resulting social situation, individual adaptation and interaction of the patient with the social environment. However, unfortunately, this technology has not been widely implemented in the actual clinical practice of psychiatry, remaining an additional mechanism that psychiatrists used at their own request and at their own discretion.

Modern concepts of the development of schizophrenia

In the origin of schizophrenia, the stress-diathesis model is generally accepted, in which the causes of the development of the disease are not only a hereditary factor, but also environmental and social [10]. If one of the parents is ill, the risk of inheriting schizophrenia is 11%; if both parents are ill, it is up to 42% [11].

Great importance is attached to deviations in the development of the brain, when superthreshold external stimuli lead to a progressive process, which is manifested by psychopathological (positive and negative) symptoms [12].

With regard to neurochemical processes, the following disorders are of great importance:

- Disorders of dopamine neurotransmission.

It has been established that prefrontal dopamine deficiency and hypostimulation of D1 receptors play a role in the development of negative and cognitive manifestations [13]. An excess of subcortical dopamine and hyperstimulation of D2 receptors lead to the appearance of productive disorders [14]. Conceptual evidence for the significance of dopamine dysfunction was presented in a key publication by Arvid Karlsson in 1963 (Nobel laureate 2000) [15]. The concept is based on observations showing that psychostimulants stimulate dopamine receptors, while antipsychotics block them [16]. It was found that the blockade of dopamine receptors leads to extrapyramidal disorders and hyperprolactinemia. When studying the action of neuroleptics, an effect was proved that is associated not only with their action on D2 receptors, but also with the ability to inhibit 5-HT2-serotonin receptors. Later it was proved that some atypical antipsychotics (clozapine, olanzapine) have a stronger effect on serotonin receptors than on dopamine ones [17]. Thus, the involvement of the serotonin system in the formation of dopamine imbalance was established.

Later it was proved that some atypical antipsychotics (clozapine, olanzapine) have a stronger effect on serotonin receptors than on dopamine ones [17]. Thus, the involvement of the serotonin system in the formation of dopamine imbalance was established.

- Disorders of glutamate neurotransmission.

The essence of the concept is a decrease in the conduction of nerve impulses in the brain of patients due to inhibition of NMDA-type glutamate receptors. The search focused on drugs that stimulate NMDA receptors [18]. It was found that these receptors are associated with 5HT2a receptors, and now this concept is more correctly called serotonin-glutamate. Convincing evidence has been accumulated that dysfunction of the serotonin-glutamate complex determines the predisposition to hallucinations.

- Autoimmune disorders.

The hypothesis appeared in the 60-70s. last century [19]. The basis is the detection of antibodies to brain components in the blood. The advantage of the hypothesis is experimental confirmation. At present, there is no doubt about the involvement of the immune system in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia [20]. Disadvantages - the inability to explain the polymorphism of clinical symptoms. In addition, autoantibodies are found in many (if not all) psychiatric disorders [21].

The advantage of the hypothesis is experimental confirmation. At present, there is no doubt about the involvement of the immune system in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia [20]. Disadvantages - the inability to explain the polymorphism of clinical symptoms. In addition, autoantibodies are found in many (if not all) psychiatric disorders [21].

- Disorders of kynurene metabolism.

The basis - in patients with schizophrenia in the cerebrospinal fluid, an increased level of kynurenic acid is detected, which is formed in the brain during the metabolism of the essential amino acid tryptophan. Tryptophan in schizophrenia is metabolized via the kynurenine pathway in 95% of cases, since the enzyme is activated in astrocytes by humoral immunity factors. As a result, kynurenic acid accumulates in the brain. The only known glutamate receptor antagonist is kynurenic acid. As a result of its accumulation, glutamatergic hypofunction and reciprocal dopaminergic hyperfunction develop [22][23]. With the accumulation of kynurenic acid, a decrease in the content of serotonin and the development of depressive symptoms in schizophrenia occur. Currently, inhibitors of the enzyme that directs the exchange of tryptophan through the kynuren pathway are considered as a promising class of drugs in the treatment of schizophrenia.

With the accumulation of kynurenic acid, a decrease in the content of serotonin and the development of depressive symptoms in schizophrenia occur. Currently, inhibitors of the enzyme that directs the exchange of tryptophan through the kynuren pathway are considered as a promising class of drugs in the treatment of schizophrenia.

The role of salience

Salience is the ability to identify significant stimuli and separate them from insignificant, background ones. The function of attention is based on the phenomenon of salience, which ensures the learning and survival of an individual and allows it to focus limited perceptual and cognitive resources on important data sets coming from various sensory systems [24].

Violation of saliens in schizophrenia is a pivotal phenomenon. Some researchers [25] propose to group schizophrenia spectrum disorders in the group of “salyens dysregulation syndromes” in future classifications. Mesolimbic and limbic structures are the main neuroanatomical substrate of saliens. The main neurotransmitter involved in the formation of a response to a significant stimulus is dopamine, which converts an emotionally neutral bit of information into an emotionally colored (positive or negative) reaction, i.e., into a “salience event”.

The main neurotransmitter involved in the formation of a response to a significant stimulus is dopamine, which converts an emotionally neutral bit of information into an emotionally colored (positive or negative) reaction, i.e., into a “salience event”.

- Kapur [26]. suggested that the hyperdopaminergic pathological state of the limbic system that occurs in schizophrenia leads to a violation of the adequate distribution of salience events in response to various internal and external stimuli. This violation causes a wide range of positive symptoms of schizophrenia (hallucinatory-delusional symptoms, disorganization of thinking, etc.).

The role of the mother in the origin of schizophrenia in her son

Biological aspects

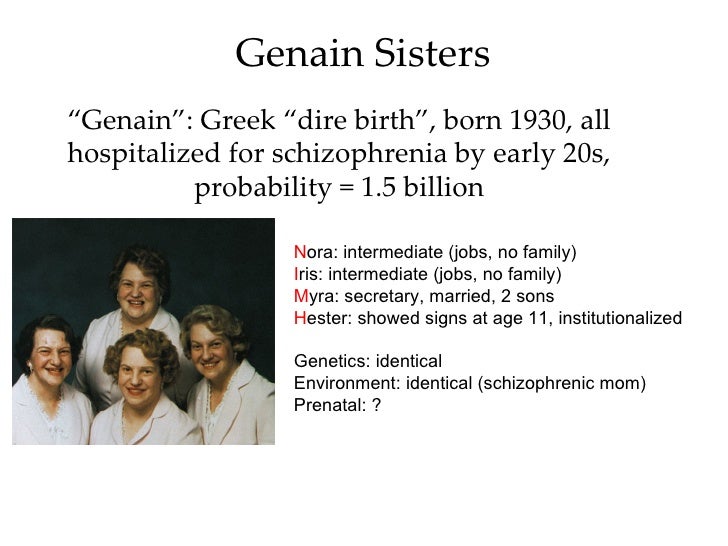

There is no doubt that genetic factors play an important role in the development of schizophrenia. The involvement of genes in the development of schizophrenia is evidenced by numerous results of genetic studies. Most likely, schizophrenia is a polygenic disease, and the risk of inheriting each individual gene is small. Thus, both monozygotic twins do not always suffer from schizophrenia; the development of this disease also requires environmental triggers [27].

Thus, both monozygotic twins do not always suffer from schizophrenia; the development of this disease also requires environmental triggers [27].

The lifetime risk of developing schizophrenia in the general population is about 1%, in monozygotic twins - 35-60%, in dizygotic twins - 10-30%, in siblings with schizophrenia - 10%, in a child whose one of the parents has schizophrenia , - 10-17%, in a child whose both parents have schizophrenia - 30-40% [28].

In a classic study by Torrey E.F. et al. [29] evaluated information from families of monozygotic twins that are not concordant for schizophrenia. In each pair of twins, the age of development of schizophrenia and the differences between the twins from each other were determined. Interestingly, in some couples (30%), changes were noted at an early age (0-5 years), and in most cases, symptoms appeared during adolescence and young age, as expected by the researchers.

Family periods of exacerbations reflect endogenous cyclic processes of the body that have a nonspecific effect on the pathogenetic mechanisms of mental illness, contributing in some cases to their clinical manifestation. One must think that these biorhythms arose and were genetically fixed in the process of phylogenesis, which is unique for each individual family. Identification of the "family stereotype" in the development of the clinical picture of the disease is used in medical genetic prediction and assessment of the development of schizophrenia in close relatives [30].

One must think that these biorhythms arose and were genetically fixed in the process of phylogenesis, which is unique for each individual family. Identification of the "family stereotype" in the development of the clinical picture of the disease is used in medical genetic prediction and assessment of the development of schizophrenia in close relatives [30].

According to the genetic theory of the development of schizophrenia, certain schizophrenia candidate genes are involved in the occurrence of this disease, creating a predisposition to the disease, which is not always realized. In most cases, disorders in this pathology are found in three chromosomal regions: 22q11, 1q42 / 11q14, X-chromosome. In 2014, a scientific paper was published in the journal Nature [31], which was called the largest study of schizophrenia-associated variations of single nucleotide polymorphisms: 108 of them were found. Anomalies of DRD2 (dopamine D2 receptors) can be found there, as well as a large number of genes , which are involved in glutamatergic neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity: GRM3, GRIN2A, CPP, GRIA1.

Variations in the CACNA1C, CACNB2, and CACNA1I genes involved in the functioning of the calcium channel deserve special attention, which can expand previous conclusions about the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. There is an idea that genetic defects create an imbalance in the functioning of the mediator systems of the brain as a result of impaired neurotransmission, arborization, synaptogenesis, selection of neurons during brain maturation, and dysfunction of individual links in the implementation of the synaptic signal (neurotransmitters, systems of intracellular messengers, systems of hormones and enzymes , membrane complexes) [32][33].

A.V. Snezhnevsky [34] suggested that amphetamine is a provoking factor for the "pathos of schizophrenia" and causes an "experimental" model of schizophrenia. Long-term use of methamphetamine causes more severe psychiatric symptoms and markedly reduces the density of dopamine transporters in the brain, which may persist even after methamphetamine use is stopped. With a decrease in the density of dopamine transporters, persistent psychopathological symptoms remain in methamphetamine users, including psychotic [35][36].

With a decrease in the density of dopamine transporters, persistent psychopathological symptoms remain in methamphetamine users, including psychotic [35][36].

Intrauterine developmental disorders are associated with mental disorders in adults due to dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA axis), which leads to increased levels of glucocorticoids and inflammation [37]. One of the hypotheses explaining the formation of schizophrenia notes that such early pathologies as intrauterine infections, maternal starvation, intrauterine growth restriction, caesarean section, as well as pre- and perinatal hypoxia, probably lead to destruction of the nervous tissue and an increased risk of developing schizophrenia.

A number of studies point to the biological mechanisms underlying these associations and include abnormal functioning of the reninangiotensin system, excitable placental function, and epigenetic regulation of gene expression [38]. In addition, cytokine-associated inflammatory responses to intrauterine infection can lead to abnormal brain development, later development of psychosis, and have been shown to cause altered glycemic regulation and excess body fat in adults [39].

The prenatal disorder hypothesis provides an important biological link between abnormal prenatal development, risk of schizophrenia, and somatic disorders. In 2016 Nielson et al. [40] published a retrospective analysis showing that maternal anemia and infections were associated with an increased risk of developing schizophrenia. According to this study, the presence of anemia and infections in the mother led to a 2.49-fold increase in the risk of developing schizophrenia in newborns. The study found that maternal infection and anemia may represent two independent risk factors for schizophrenia. However, the authors did not take into account one unifying factor, which is zinc deficiency, which is known to be often associated with anemia, being a predisposition factor for infections and brain development disorders [41].

Evidence suggests that maternal toxicosis during pregnancy, drug use, and childhood illnesses at an early age are negatively correlated with duration of schizophrenia [42].

Fetal hypoxia, perinatal trauma, hereditary complications (presence of hereditary mental, neurological and other diseases in parents), Rh incompatibility or blood type incompatibility between the fetus and mother correlate with the unfavorable course of schizophrenia [43].

The low level of premorbid education worsens the course of schizophrenia to a lesser extent [44]. Maternal illnesses during pregnancy, including those of an infectious nature, especially the influenza virus, increase the factor associated with the early manifestation of the disease [45][46].

Thus, perinatal influenza infection leads to a limitation of neuronal release of reelin, which regulates cortico-hypocampal migration of neurons, and this causes weakness of those brain structures that are primarily affected in schizophrenia [47][48]. Viral hypotheses of the genesis of schizophrenia allow both direct influence of neurotropic viruses on neurons, which leads to the destruction of these cells, and indirect,

Infection in the postnatal period plays a role in the etiology of schizophrenia. Neuroinfection before the age of 14 leads to a high risk of schizophrenia in adulthood. A correlation has been observed between childhood meningitis before the age of five and psychosis in adulthood. Toxoplasma gondii increases the risk of manifestation of schizophrenia as an intracellular parasite, being one of the etiological agents acting before and after the birth of a child.

Neuroinfection before the age of 14 leads to a high risk of schizophrenia in adulthood. A correlation has been observed between childhood meningitis before the age of five and psychosis in adulthood. Toxoplasma gondii increases the risk of manifestation of schizophrenia as an intracellular parasite, being one of the etiological agents acting before and after the birth of a child.

Late parental age at conception, complications during labor (prolonged pushing, rapid labor, additional stimulation, vacuum extraction of the fetus, obstetric forceps, long anhydrous interval), low Apgar score at birth, and pre-manifest alcohol consumption increase the factor associated with a low level of social functioning [49].

Numerous studies since 1929 have found a relationship between schizophrenia and birth season. In an article by Torrey E.F. et al. [50] published the results of a work on this topic, which analyzed data from studies of the seasonality of the birth of patients with schizophrenia in the southern and northern hemispheres. The prevailing number of births of patients with schizophrenia was noted in the period from December to May [51]. Mortensen P.B. et al. [52] note an increase in the births of patients with schizophrenia in February and March. Vilyanov V.B. and Egorov S.V. [53] studied the seasonality of the birth of patients with schizophrenia in Russia. The largest number of births, according to their data, was in March. Gender-related differences were noted. In men, peak fertility occurred in March and July, in women - only in March. Other authors also pointed to differences in the seasonality of births of patients with schizophrenia, depending on the biological sex. Among women with schizophrenia, Japanese researchers revealed a predominance of the number of births in the winter-spring time, which was not observed in men [54].

The prevailing number of births of patients with schizophrenia was noted in the period from December to May [51]. Mortensen P.B. et al. [52] note an increase in the births of patients with schizophrenia in February and March. Vilyanov V.B. and Egorov S.V. [53] studied the seasonality of the birth of patients with schizophrenia in Russia. The largest number of births, according to their data, was in March. Gender-related differences were noted. In men, peak fertility occurred in March and July, in women - only in March. Other authors also pointed to differences in the seasonality of births of patients with schizophrenia, depending on the biological sex. Among women with schizophrenia, Japanese researchers revealed a predominance of the number of births in the winter-spring time, which was not observed in men [54].

Psychological aspects

Most psychological risk factors are long-term: during childhood and adulthood, immediately before the onset of psychosis. Great importance is attached to a number of factors affecting a child under the age of three, such as "the inability to form an object of affection", "the presence of a cold, emotionally immature mother", "early loss of parents", "cruel attitude or sexual corruption at a young age, before in total, by persons from the primary support group of the child”, “peculiarities of raising a child” [55].

Specific upbringing of a child. For the first time in Israel, the influence of raising a child on the realization of the risk of schizophrenia manifestation was proved [56]. During the observation of two groups of children born to parents with schizophrenia, children brought up in their own family were singled out in the first group, and the children of the other group grew up in an agricultural commune, where living conditions were close to ideal, according to the founders of the commune. After 25 years, it turned out that schizophrenia and affective diseases were more common in the second group of children than in children who grew up in a family. The researchers concluded that raising children in a family, even if they are dysfunctional in their illness, reduces the risk of developing mental disorders.

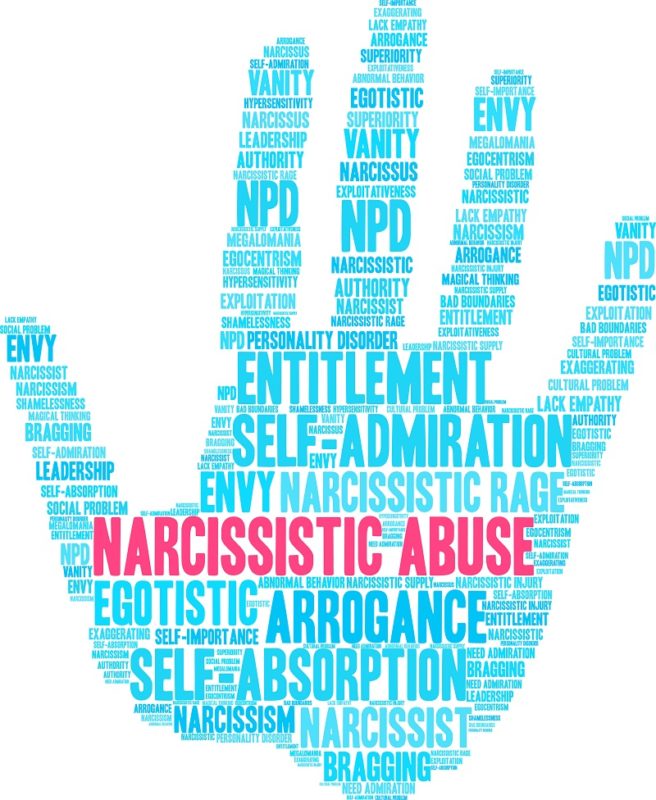

Violation of parental affection. A correlation was noted with atypical interactions in the mother-infant system, which further increases the risk of schizophrenia manifestation in adulthood. Atypical interactions in the mother-child system were noted in mothers of children who were diagnosed with schizophrenia and schizoform disorders in adulthood. Therefore, the concept of “schizogenic mother” arose in psychology - a dominant, internally emotionally alienated woman in relation to the child, who uses the child as a social project to achieve her goals and at the same time demonstrates to the child inconsistency in relation to him in her behavior (from excessive control to aggression , albeit only verbally). There is no doubt that a schizogenic mother cannot be the only or main cause of the onset and development of schizophrenia, but it can provoke the formation of a higher level of schizoidness, subsequent dramatic psychological problems and social maladaptation. Mental disorders such as manic, anxiety or depressive disorders have not been confirmed for mothers of children with other mental disorders [57].

Atypical interactions in the mother-child system were noted in mothers of children who were diagnosed with schizophrenia and schizoform disorders in adulthood. Therefore, the concept of “schizogenic mother” arose in psychology - a dominant, internally emotionally alienated woman in relation to the child, who uses the child as a social project to achieve her goals and at the same time demonstrates to the child inconsistency in relation to him in her behavior (from excessive control to aggression , albeit only verbally). There is no doubt that a schizogenic mother cannot be the only or main cause of the onset and development of schizophrenia, but it can provoke the formation of a higher level of schizoidness, subsequent dramatic psychological problems and social maladaptation. Mental disorders such as manic, anxiety or depressive disorders have not been confirmed for mothers of children with other mental disorders [57].

Historically, the concept of a “schizophrenogenic” mother, and not a “schizogenic” mother, originally arose. Even Sigmund Freud pointed to the possible psychological causes of schizophrenia. Freud assumed that if parents go to extremes in raising a child (for example, parents are excessively harsh, cold and aloof, or, conversely, show excessive concern for the child), then the child experiences psychological stress and develops responses (psychological defenses). According to Freud, the child experiences psychological processes of regression and attempts to regain control of his Ego over the situation. Departing from the emotional stress that is beyond the strength of the child's psyche, the child "escapes" to a world where he felt good - he regresses into childhood and there falls into the extremes of narcissism and egocentric concern exclusively for his needs. That is, the child responds with extreme measures to the extremes of the parents. However, while growing up, the child cannot remain in a state of regression to childhood, since parents and the surrounding reality forcibly “pull out” the child from there (after all, the requirements for the maturing child increase), and then the maturing child tries to regain control of his Ego over the situation.

Even Sigmund Freud pointed to the possible psychological causes of schizophrenia. Freud assumed that if parents go to extremes in raising a child (for example, parents are excessively harsh, cold and aloof, or, conversely, show excessive concern for the child), then the child experiences psychological stress and develops responses (psychological defenses). According to Freud, the child experiences psychological processes of regression and attempts to regain control of his Ego over the situation. Departing from the emotional stress that is beyond the strength of the child's psyche, the child "escapes" to a world where he felt good - he regresses into childhood and there falls into the extremes of narcissism and egocentric concern exclusively for his needs. That is, the child responds with extreme measures to the extremes of the parents. However, while growing up, the child cannot remain in a state of regression to childhood, since parents and the surrounding reality forcibly “pull out” the child from there (after all, the requirements for the maturing child increase), and then the maturing child tries to regain control of his Ego over the situation. This is how delusions of persecution and grandeur arise. According to Sigmund Freud, this is how schizophrenia arises and develops in a person as a result of the influence of parental upbringing. Thus, Freud raised the question of schizophrenogenic parents as well.

This is how delusions of persecution and grandeur arise. According to Sigmund Freud, this is how schizophrenia arises and develops in a person as a result of the influence of parental upbringing. Thus, Freud raised the question of schizophrenogenic parents as well.

However, the concept of "schizophrenogenic mother" was developed in detail not by Sigmund Freud, but by Frieda Fromm-Reichmann in 1948 [58]. In her opinion, a schizophrenogenic mother is a cold dominant woman who does not pay enough attention to the needs of the child. For a schizophrenogenic mother, a child is a social project, not a little loved one. Such mothers can demonstrate the heroic overcoming of difficulties in the birth and upbringing of a child, their maternal self-sacrifice, and in fact use the conditional social project "Child" to achieve their goals in life. A schizogenic mother does not make a purposeful conscious effort to create a high level of schizoidness in her child (who subsequently experiences the natural consequences of schizoidness in adulthood). A schizogenic mother prioritizes her life goals and follows the lead of her character traits (personality). She does not control her behavior towards the child, she gets a schizoid child simply and logically, as a result of her behavior. A schizogenic mother may well love her child, but she loves herself, her personality and her life goals much more. To change for the purposes of raising a psychologically prosperous and socially adaptive child, or at least to control her emotions and behavior, the schizogenic mother cannot or does not want to.

A schizogenic mother prioritizes her life goals and follows the lead of her character traits (personality). She does not control her behavior towards the child, she gets a schizoid child simply and logically, as a result of her behavior. A schizogenic mother may well love her child, but she loves herself, her personality and her life goals much more. To change for the purposes of raising a psychologically prosperous and socially adaptive child, or at least to control her emotions and behavior, the schizogenic mother cannot or does not want to.

Adoption of children with a high family risk of schizophrenia. Children adopted with a high family risk of schizophrenia are at high risk of the disease. Adopted children whose mothers had schizophrenia had a higher incidence of schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and other severe psychiatric disorders.

Harassment and sexual abuse. Child abuse, including child sexual abuse, increases the risk of psychotic disorders, particularly schizophrenia, in adulthood. The impact on the brain of a young child of traumatic events leads to neurobiological changes similar to those described in schizophrenia - to a violation of the differentiation of monoamine neurotransmitter tracts and the process of synaptic contraction with the preservation of an excess density of dopaminergic receptors in the hypocampal structures, ventriculodilatation, mediobasal and cerebral atrophy, activation of the hypothalamus - pituitary-adrenal system. There is a well-established relationship between child abuse during the first three years of life and the risk of schizophrenia during the subsequent time, which is explained by the diathesis-stress model of psychosis.

The impact on the brain of a young child of traumatic events leads to neurobiological changes similar to those described in schizophrenia - to a violation of the differentiation of monoamine neurotransmitter tracts and the process of synaptic contraction with the preservation of an excess density of dopaminergic receptors in the hypocampal structures, ventriculodilatation, mediobasal and cerebral atrophy, activation of the hypothalamus - pituitary-adrenal system. There is a well-established relationship between child abuse during the first three years of life and the risk of schizophrenia during the subsequent time, which is explained by the diathesis-stress model of psychosis.

Childhood trauma is closely associated with neurocognitive impairment, which is similar to cognitive impairment in schizophrenia. Particularly distinguished are violations of emotional cognition and social perception of a person. Such disorders are very often predictors of schizophrenia, which mainly manifest in adulthood.

Combination of biological and psychological factors in the development of schizophrenia

Schizophrenia has a polyetiological and multifactorial etiopathogenesis [59][60][61]. The issue of the influence of environmental factors on the clinical phenotype of the disease is widely discussed [62]. In the anamnesis of patients with schizophrenia spectrum disorders, such factors as past infectious and somatic diseases by the mother during pregnancy, alcohol consumption by the mother during pregnancy, alcohol consumption by patients in adolescence that did not reach the level of dependence, fetal hypoxia or perinatal trauma at birth, problems with a primary support group in the patient's family in childhood (more often antisocial parents, child abuse), pregnancy toxicosis in the mother, crisis relationships in the family (physical or sexual abuse, alcohol abuse), migration to another cultural environment [63].

Son's illness as a factor influencing mother's health

Psychologically it can be difficult to adapt to the social role of motherhood in general, it is even more difficult to accept the situation of the birth of a child with developmental defects or further diagnosis of a mental illness. The mother's pathological perception of the situation of the child's illness, the further formation of disharmonious intra-family relations negatively affects the mental state of all family members, distorting the model of their relationships, disrupting the mother's social behavior and complicating the adequate socialization of the sick child [64].

The mother's pathological perception of the situation of the child's illness, the further formation of disharmonious intra-family relations negatively affects the mental state of all family members, distorting the model of their relationships, disrupting the mother's social behavior and complicating the adequate socialization of the sick child [64].

According to the literature, mothers of children with disabilities are characterized by doubts about the value of their own personality, high conflict, the development of ideas of self-blame for the birth of a child with defects. Often, manifestations of increased self-control act as a protective mechanism that helps in hiding these experiences [65]. Mothers of sick children have a low level of self-awareness, they tend to hide unpleasant information from themselves and others. The following psychological features of mothers of sick children are distinguished: deformation of self-attitude, expressed in its negative emotional background, self-doubt, the presence of various internal conflicts, a pathological defense system, represented by an intense and rigid manifestation of the protective mechanisms of rationalization, reactive formation and projection, as well as an unconscious desire for psychological self-defence, expressed in the intense manifestation of social desirability and the denial of one's own illnesses. The superficiality of adaptation can manifest itself in the form of severe pathologies when the social conditions of life change. Accordingly, mothers of sick children need to be provided with psychocorrectional assistance aimed at forming a positive emotional and value attitude towards themselves, increasing the level of awareness, and teaching adequate forms of behavior [66].

The superficiality of adaptation can manifest itself in the form of severe pathologies when the social conditions of life change. Accordingly, mothers of sick children need to be provided with psychocorrectional assistance aimed at forming a positive emotional and value attitude towards themselves, increasing the level of awareness, and teaching adequate forms of behavior [66].

G.A. Mishina (1998) [67] studied cooperation options in parent-child pairs. The author considered deviations in the psychophysical development of young children not only as a possible consequence of organic and functional disorders, but also as manifestations due to the lack of adequate ways of cooperation between parents and children and a lack of communication. She concluded that parents raising a child with schizophrenia have an unemotional nature of cooperation, do not know how to create a situation of joint activity, and have an inadequate position in relation to the child. In almost every family raising a child with schizophrenia, there are often a wide variety of emotions that are unsafe for the mother and for the sick child.

Below are some common unhealthy mental attitudes [68]:

- Rejection of the situation. The inner selfishness of a woman, the lack of pity, sympathy and love for a sick child.

- Search for the guilty. With this position, enmity occurs between all family members. This further complicates the situation and excludes cooperation in the family.

- Transferring the blame to the child. There is isolation of the child in the family, conflict situations, as a result of which his mental and physical condition worsens.

- Wrong shame. The reason is that disabled people in Russia do not have the opportunity to fully participate in social life, which leads to a stressful situation for the patient and aggravates his condition, as he risks being cut off from society and peers [69].

- Guilt complex. Manifested by increased hyper-custody of a sick child. This can lead to a psychological disruption of his behavior, which will further increase his maladjustment.

- Self-deprecating mood, which manifests itself in the form of neglected complexes. This situation does not lead to an improvement in his condition.

- The syndrome of the victim, manifests itself in the absence of seeing a personality in the child, a tendency to "suffering" and in demonstrative behavior.

- Mania of "difference". Such moods exclude help and support from other people and lead to isolation from society.

- The consumer mood develops the habit of suggesting to oneself, the child and other people that his condition is only getting worse. This leads to the exclusion of the full socialization of a sick child.

- "Deadly pity", when the guardian asserts himself at the expense of a sick child. The only purpose in life is to care for a sick child. Self-importance is measured by the degree of need for a disabled person.

In the empirical study "Socio-psychological problems in children with disabilities" in 2015 Politik O. I. [70] reveals in detail the dependence of the development of a child with schizophrenia on the relationship with the mother and her own attitude towards herself. The author notes: “The mother begins to be burdened by her maternal status, as she puts a lot of effort into raising the child.” There is irritability, neuroticism, a sense of burden of parental responsibility. The parents revealed a sense of guilt for "wrong education", which was eliminated through a strict attitude towards the child (54.5%) or self-elimination (18.2%), which is an indicator of the deformation of the educational approach. Children become fussy, pugnacious, they constantly scream, cry, are very excited, anxiety and hostility are formed, which is often interpreted as capriciousness and spoiledness. O.I. The politician writes: “The feeling of guilt for improper upbringing encourages parents to unconsciously create a stressful situation: frequent punishments, shouting, the desire to insist on parental rights.” The author concludes that deprivation of parental relationships correlates with disorders of emotional and speech development.

I. [70] reveals in detail the dependence of the development of a child with schizophrenia on the relationship with the mother and her own attitude towards herself. The author notes: “The mother begins to be burdened by her maternal status, as she puts a lot of effort into raising the child.” There is irritability, neuroticism, a sense of burden of parental responsibility. The parents revealed a sense of guilt for "wrong education", which was eliminated through a strict attitude towards the child (54.5%) or self-elimination (18.2%), which is an indicator of the deformation of the educational approach. Children become fussy, pugnacious, they constantly scream, cry, are very excited, anxiety and hostility are formed, which is often interpreted as capriciousness and spoiledness. O.I. The politician writes: “The feeling of guilt for improper upbringing encourages parents to unconsciously create a stressful situation: frequent punishments, shouting, the desire to insist on parental rights.” The author concludes that deprivation of parental relationships correlates with disorders of emotional and speech development.

Conclusions

Thus, we can speak of an obvious mutual influence between a child with schizophrenia and his mother. On the one hand, it can manifest itself in the fact that a certain number of personal characteristics of the mother is accompanied by the formation of high rates of schizoidness and neuroticism in the child. Of course, the presence of a certain psychological type of mother (as the only reason) is not enough for the onset and development of schizophrenia, but the subsequent development of personality disorders in a child, as a borderline state between the norm and pathology, can already be the basis for the development of the disease in the presence of other more significant reasons (for example, , hereditary). On the other hand, a child’s illness can be a significant stress factor for a mother, leading to the formation of manifestations of emotional stress and psychological maladjustment in her, which, in turn, can negatively affect not only the characteristics of her relationship with the child, but also the characteristics of its course. diseases. The mechanisms of the formation of such a “vicious circle” are poorly understood even theoretically, not to mention the fact that in routine psychiatric practice these issues do not fall into the focus of attention of a psychiatrist and are not taken into account when developing a therapy strategy. However, the parameters of interaction between mother and child, the level of their mutual empathy, may be important for the formation of compliance in the treatment of schizophrenia, since it is the mother who is the “guide” of therapy in relation to a small patient. There is also no doubt that the level of a mother's mental health is an important resource for maintaining the viability of the entire family system and, in particular, a necessary condition for organizing adequate therapy for a child with schizophrenia. Therefore, the study of the issues of mutual influence of a patient with schizophrenia and his mother, the development of methods for correcting the problems that arise in this case are an important scientific and practical task of modern psychiatry.

diseases. The mechanisms of the formation of such a “vicious circle” are poorly understood even theoretically, not to mention the fact that in routine psychiatric practice these issues do not fall into the focus of attention of a psychiatrist and are not taken into account when developing a therapy strategy. However, the parameters of interaction between mother and child, the level of their mutual empathy, may be important for the formation of compliance in the treatment of schizophrenia, since it is the mother who is the “guide” of therapy in relation to a small patient. There is also no doubt that the level of a mother's mental health is an important resource for maintaining the viability of the entire family system and, in particular, a necessary condition for organizing adequate therapy for a child with schizophrenia. Therefore, the study of the issues of mutual influence of a patient with schizophrenia and his mother, the development of methods for correcting the problems that arise in this case are an important scientific and practical task of modern psychiatry.

1. Smulevich A.B. Low-progressive schizophrenia and borderline states. - M.: MED press-inform, 2009.

2. Dyachenko L.I. Organization of psychiatric care for patients with schizophrenia // Schizophrenia: new approaches to therapy: Collection of scientific papers of the Ukrainian Research Institute of Clinical and Experimental Neurology and Psychiatry and Kharkov City Clinical Psychiatric Hospital No. 15 (Saburova dacha), 1995.

3. Tandon R., Keshavan M.S. , Nasrallah H.A. Schizophrenia: Just the Facts What we know // Schizophr Res. – 2008. – V.102(1-3). – P.1-18. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2008.04.011.

4. Mental health: strengthening the fight against mental disorders. // Newsletter of the World Health Organization. - 2010. - No. 220. - 12 p.

5. Jones P. Cannon M. The new epidemiology of schizophrenia // Psychiatr. Clin. North. Am. - 1998. - V. 21(1). - R. 1-25.

6. Roffman J.L., Brohawn D.G., Nitenson A.Z., Macklin E.A., Smoller J.W., Goff D. C. Genetic Variation Throughout the Folate Metabolic Pathway Influences Negative Symptom Severity in Schizophrenia // Schizophr. Bull. — 2013. — V.39(2). - P. 330-8. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr150

C. Genetic Variation Throughout the Folate Metabolic Pathway Influences Negative Symptom Severity in Schizophrenia // Schizophr. Bull. — 2013. — V.39(2). - P. 330-8. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbr150

7. Susser E., Neugebauer R., Hoek H.W., Brown A.S., Lin S., et al. Schizophrenia after prenatal famine. Further evidence // Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. - 1996. - V. 53(1). - R. 25-31. DOI: 10.1001/archpsyc.1996.01830010027005

8. E.Yu. - Moscow, 2018.

9. Górna K., Jaracz K., Jaracz J., Kiejda J., Grabowska-Fudala B., Rybakowski J. Social functioning and quality of life in schizophrenia patients: relationship with symptomatic remission and duration of illness // Psychiatia Polska. - 2014. - No. 48(2). – P. 277–288. (in Polish)

10. Abramov V.A., Putsay S.A., Kutko I.I. Functional diagnosis of mental illness (guidelines) - Donetsk: Donetsk State Medical Institute; 1990.

11. Semenov S.F. Some features of the clinic and the course of schizophrenia with the phenomena of autoimmunization with brain antigens // Journal of neuropathology and psychiatry - 1964. - V. 64. - No. 3. - P. 398.

- V. 64. - No. 3. - P. 398.

12. Semenov S.F. Schizophrenia. - Kyiv: Medical publishing house of the Ukrainian SSR; 1961.

13. Smulevich A.B. Low-progressive schizophrenia and borderline states. — M.: MED press-inform; 2009.

14. Fuller Torrey E. Schizophrenia. A book to help doctors, patients and their families. - St. Petersburg: Peter Press; 1996.

15. Carlsson A. Progress in the dopamine theory of schizophrenia: A reference book for physicians. - 2003.

16. Alexandrovsky Yu. A. Premorbid conditions and borderline mental disorders (etiology, pathogenesis, specific and nonspecific symptoms, therapy). — M.: Litterra; 2010.

17. Bukhanovsky A.O., Vilkov G.A., Dubatova I.V., Perekhov A.Ya., Cherenkov S.A. The use of plasmapheresis in schizoaffective psychoses // "Affective and schizoaffective psychoses". Conference materials. — M., 1998.—C. 408–409.

18. Kotelnikov G.P., Shpigel A.S., Kuznetsov S.I., Lazarev V.V. Introduction to evidence-based medicine. Evidence-based medical practice: a guide for doctors - Samara: Samara State Medical University, 2001.

Evidence-based medical practice: a guide for doctors - Samara: Samara State Medical University, 2001.

19. Dubatova I.V., Vilkov G.A. Experience in the application of the main parameters of the functions of certain homeostasis systems for the diagnosis, prognosis and treatment of endogenous psychoses // Scientific and Practical Conference of Psychiatrists of the South of Russia "Psychiatry at the turn of the millennium". Conference materials. - Rostov n / a, 1999.—C. 164–166.

20. Dubatova I.V. Influence of "shock" methods of therapy on the processes of free radical oxidation and antioxidant protection in patients with schizophrenia // I scientific session of the Russian State Medical University. Session materials. - Rostov-on-Don, 1996. - P. 39.

21. A short course in psychiatry. Edited by d.m.s. Soldatkina V.A. — Rostov-on-Don; 2019.

22. Zhislin S.G. Essays on clinical psychiatry. - M.: Medicine, 1965.

23. Zatsepitsky R.A. Psychological aspects of psychotherapy of patients with neuroses. In book. Topical issues of medical psychology. - L .: Medicine, 1974. - P. 54–69.

In book. Topical issues of medical psychology. - L .: Medicine, 1974. - P. 54–69.

24. Isurina G.L., Karvasarsky B.D., Leder S., Tashlykov V.A., Tupitsyn Yu.Ya. Development of the pathogenetic concept of neurosis and psychotherapy V.N. Myasishchev at the present stage. In: Theory and practice of medical psychology and psychotherapy. - SPb., 1994. - S. 100-109.

25. Rössler W., Salize H.J., van Os J., Riecher-Rössler A. Size of burden of schizophrenia and psychotic disorders. // Eur Neuropsychopharmacol - 2005. - V.15 (4). - P. 399-409. DOI: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2005.04.009

26. Kapur S. Psychosis as a state of aberrant salience: a framework linking biology, phenomenology, and pharmacology in schizophrenia // Am J Psychiatry. - 2003. - V.160(1). – P.13-23. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.1.13

27. Harrison P.J., Weinberger D.R. Schizophrenia genes, gene expression, and neuropathology: on the matter of their convergence // Molec. Psychiatry. - 2005. - V.10(1). - P. 40-68. DOI: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001558

40-68. DOI: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001558

28. Owen M.J., Williams N.M., O’Donovan M.C. The molecular genetics of schizophrenia: new findings promise new insights // Molec. Psychiatry. — 2004. — V.9(one). — P. 1427. DOI: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001444

29. Torrey E.F., Taylor E.H., Bracha H.S., Bowler A.E., McNeil T.F., et al. Prenatal origin of schizophrenia in a subgroup of discordant monozygotic twins // Schizophr. Bull. - 1994. - V. 20(3). — P. 42332. DOI: 10.1093/schbul/20.3.423

30. Bukhanovsky A.O. Some features of the clinic of family schizophrenia. Abstract - 1977. 20-25.

31. Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. // Nature. - 2014. - No. 5.- R.421-427. doi:10.1038/nature13595.

32. Laruelle M. The role of endogenous sensitization in the pathophysiology of schizophrenia: Implications from recent brain imaging studies // Brain Research Reviews. - 2000.- Vol. 31, No. 1-2.- P.371-384.

1-2.- P.371-384.

33. Lisman J.E., Coyle J.T., Green R.W., Javitt D.C., Benes F.M., et al. Circuit-based framework for understanding neurotransmitter and risk gene interactions in schizophrenia // Trends in Neuroscience.- 2008.- Vol.31, No. 5.- P.234-242. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2008.02.005

34. Lichko A.E., Bitensky V.S. Teenage addiction. SPb., 1991.

35. Sekine Y., Iyo M., Ouchi Y., Matsunaga T., Tsukada H., et al. Methamphetamine-Related Psychiatric Symptoms and Reduced Brain Dopamine Transporters Studied With PET // American Journal of Psychiatry. - 2001. - V.158(8). - P. 1206-1214. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1206

36. Volkow ND. Drug Abuse and Mental Illness: Progress in Understanding Comorbidity // Am J Psychiatry. - 2001. - V.158(8). – P.1181-3. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.8.1181

37. Fabrega H. The self and schizophrenia: a cultural perspective. // Jr Schizophr Bull. - 1989. - V .; 15 (2). – P.277-90. DOI: 10.1093/schbul/15.2.277

38. Chou IJ, Kuo CF, Huang YS, Grainge MJ, Valdes AM, et al. Familial Aggregation and Heritability of Schizophrenia and Co-aggregation of Psychiatric Illnesses in Affected Families. // Schizophr Bull. – 2017. – V.43(5). – P.1070-1078. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw159.

Chou IJ, Kuo CF, Huang YS, Grainge MJ, Valdes AM, et al. Familial Aggregation and Heritability of Schizophrenia and Co-aggregation of Psychiatric Illnesses in Affected Families. // Schizophr Bull. – 2017. – V.43(5). – P.1070-1078. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbw159.

39. Self-consciousness: an integrative approach from philosophy, psychopathology and the neurosciences. Kircher T., David AS eds. - Cambridge University Press; 2003.

40. Nelson C.W. Remembering Austin L. Hughes. // Infect Genet Evol. - 2016. - V.40. - P.262-265. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2016.02.030

41. Martin B., Wittmann M., Franck N., Cermolacce M., Berna F., Giersch A. Temporal structure of consciousness and minimal self in schizophrenia. // Front Psychol. - 2014. - V.5. – P.1175. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01175.

42. Houston J.E., Murphy J., Shevlin M., Adamson G. Cannabis use and psychosis: Re-visiting the role of childhood trauma. // Psychol. Med. – 2011. – V. 41(11). – P. 2339–2348. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000559

43. Konings M., Stefanis N., Kuepper R., de Graaf R., ten Have M., et al. Replication in two independent population-based samples that childhood maltreatment and cannabis use synergistically impact on psychosis risk // Psychol. Med. - 2012. - No. 42(1). - P. 149-159. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711000973