Examples of compensation defense mechanism

Compensation (defence mechanism) | Psychology Wiki

Assessment | Biopsychology | Comparative | Cognitive | Developmental | Language | Individual differences | Personality | Philosophy | Social |

Methods | Statistics | Clinical | Educational | Industrial | Professional items | World psychology |

Clinical: Approaches · Group therapy · Techniques · Types of problem · Areas of specialism · Taxonomies · Therapeutic issues · Modes of delivery · Model translation project · Personal experiences ·

In psychoanalysis compensation has a more specific meaning and is the name of a defence mechanism. In psychology, compensation is a strategy whereby one covers up, consciously or unconsciously, weaknesses, frustrations, desires, feelings of inadequacy or incompetence in one life area through the gratification or (drive towards) excellence in another area. Compensation can cover up either real or imagined deficiencies and personal or physical inferiority.

The compensation strategy, however does not truly address the source of this inferiority. Positive compensations may help one to overcome one’s difficulties. On the other hand, negative compensations do not, which results in a reinforced feeling of inferiority. There are two kinds of negative compensation:

Overcompensation, characterized by a superiority goal, leads to striving for power, dominance, self-esteem and self-devaluation.

Undercompensation, which includes a demand for help, leads to a lack of courage and a fear for life.

A well-known example of failing overcompensation, is observed in people going through a the midlife-crisis. Approaching midlife many people (especially men) lack the energy to maintain their psychological defenses, including their compensatory acts.

Contents

- 1 Origin:

- 2 Cultural implications:

- 3 See also

- 4 References

- 5 External links

Origin:

Alfred Adler, founder of the school of individual psychology, introduced the term compensation in relation to inferiority feelings. In his book Study of Organ Inferiority and Its Physical Compensation (1907) he describes this relationship: Each individual has feelings of inferiority. Additionally, Adler states that there is a strong, natural tendency to conceal these feelings, since they are regarded as a sign of weakness. Therefore they find their expression in a striving for superiority. This mechanism may explain why some disabled people come to excel in a certain sphere of activity, see for example: Stevie Wonder, Glenn Cunningham, and Demosthenes. (Interestingly, Adler's interest in the phenomenon developed from his knowledge that he was shy and yet that he pushed himself to give academic lectures to auditoriums of students.) This striving can manifest itself in many different ways, therefore each individual has his or her own way of attempting to achieve perfection.

In his book Study of Organ Inferiority and Its Physical Compensation (1907) he describes this relationship: Each individual has feelings of inferiority. Additionally, Adler states that there is a strong, natural tendency to conceal these feelings, since they are regarded as a sign of weakness. Therefore they find their expression in a striving for superiority. This mechanism may explain why some disabled people come to excel in a certain sphere of activity, see for example: Stevie Wonder, Glenn Cunningham, and Demosthenes. (Interestingly, Adler's interest in the phenomenon developed from his knowledge that he was shy and yet that he pushed himself to give academic lectures to auditoriums of students.) This striving can manifest itself in many different ways, therefore each individual has his or her own way of attempting to achieve perfection.

Thus, Alfred Adler transferred this idea of compensation to the area of psychic training. Contemporary psychoanalysts like Alexander Müller, Kurt Adler, Sophia de Vries, Alexander Neuer and Henry Stein elaborated on the theory of Adler in many different areas.

Cultural implications:

Christopher Lasch, a well-known American historian and social critic described in his book The Culture of Narcissism (1979) the North American society in the 1980’s as one with a narcissistic color. Narcissism in psychoanalytic theory can be seen in the light of compensation: people who are narcissistic suppress feelings of low self-esteem by talking highly about themselves and making contact with persons they admire. Lasch also describes the idea (of Melanie Klein) that narcissistic children try to compensate for their jealousy and anger by fantasizing about power, beauty and richness. The narcissistic society Lasch describes is characterized by worship of consumption, an excessive fear of aging and death, a fascination with fame, and a fear of dependency.

The worship of consuming as Lasch terms it, is described in an article by Allison J. Pugh: From compensation to ‘childhood wonder’. Today’s market economy acquisition of commodities is an important factor in the creation of experience and identity in people’s lives. Consumption therefore has been put forward as a means of compensation. The strong symbolism of using goods to convey human relationships, can for example urge parents into various act of consumption in order to compensate for their guilt. On the one hand parents may feel responsible to make up for a perceived absence in their own youth (e.g. being part of a poverty-stricken family in childhood), and are therefore keen to ensure that their offspring never need to endure a similar loss. When guilt is directed towards something amiss in the life of their offspring (e.g. a family going through a divorce situation) offering of consumer goods can be interpreted as a compensatory reparative statement on behalf of the parent, a symbolic substitute for care.

Consumption therefore has been put forward as a means of compensation. The strong symbolism of using goods to convey human relationships, can for example urge parents into various act of consumption in order to compensate for their guilt. On the one hand parents may feel responsible to make up for a perceived absence in their own youth (e.g. being part of a poverty-stricken family in childhood), and are therefore keen to ensure that their offspring never need to endure a similar loss. When guilt is directed towards something amiss in the life of their offspring (e.g. a family going through a divorce situation) offering of consumer goods can be interpreted as a compensatory reparative statement on behalf of the parent, a symbolic substitute for care.

See also

Compensation neurosis

References

- Ambrogne, J. A. (1999). Patterns of compensation in alcohol-dependent women. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

- Area, R.

, Garcia-Caballero, A., Gomez, I., Somoza, M. J., Garcia-Lado, I., Recimil, M. J., et al. (2003). Conscious Compensations for Thought Insertion: Psychopathology Vol 36(3) May-Jun 2003, 129-131.

, Garcia-Caballero, A., Gomez, I., Somoza, M. J., Garcia-Lado, I., Recimil, M. J., et al. (2003). Conscious Compensations for Thought Insertion: Psychopathology Vol 36(3) May-Jun 2003, 129-131. - Backman, L. (1989). Varieties of memory compensation by older adults in episodic remembering. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Jones, E. E. (1978). When self-presentation is constrained by the target's knowledge: Consistency and compensation: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Vol 36(6) Jun 1978, 608-618.

- Boerner, K., & Jopp, D. (2007). Improvement/maintenance and reorientation as central features of coping with major life change and loss: Contributions of three life-span theories: Human Development Vol 50(4) Jul 2007, 171-195.

- Boker, W., & et al. (1984). Self-healing strategies among schizophrenics: Attempts at compensation for basic disorders: Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Vol 69(5) May 1984, 373-378.

- Boney-McCoy, S.

, Gibbons, F. X., & Gerrard, M. (1999). Self-esteem, compensatory self-enhancement, and the consideration of health risk: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Vol 25(8) Aug 1999, 954-965.

, Gibbons, F. X., & Gerrard, M. (1999). Self-esteem, compensatory self-enhancement, and the consideration of health risk: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Vol 25(8) Aug 1999, 954-965. - Bratt, C. (1999). Consumers' environmental beahvior: Generalized, sector-based, or compensatory? : Environment and Behavior Vol 31(1) Jan 1999, 28-44.

- Brotemarkle, R. A. (1930). Review of The lure of superiority: Psychological Bulletin Vol 27(1) Jan 1930, 72-73.

- Burka, A. A. (1983). The emotional reality of a learning disability: Annals of Dyslexia Vol 33 1983, 289-301.

- Casement, A. (2006). The shadow. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Cervone, D., & Rafaeli-Mor, N. (1999). Living in the future in the past: on the origins and expression of self-regulatory abilities: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 209-212.

- Chalus, G. A. (1976). Defensive compensation as a response to ego threat: A replication: Psychological Reports Vol 38(3, Pt 1) Jun 1976, 699-702.

- Chiland, C. (1992). Transsexualism and psychotic decompensation at adolescence. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Codina, N. (1988). Adler: A proposal for the study of leisure time activities as "compensation." Revista de Historia de la Psicologia Vol 9(1) Jan-Mar 1988, 103-110.

- Coleman, R. L., & Croake, J. W. (1987). Organ inferiority and measured overcompensation: Individual Psychology: Journal of Adlerian Theory, Research & Practice Vol 43(3) Sep 1987, 364-369.

- Colman, S. V. (1991). The sibling of the retarded child: Self-concept, deficit compensation motivation, and perceived parental behavior: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). The rejoining of immediacy and delay: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 213-214.

- Dallett, J. O. (1974). The effect of sensory and social variables on the recalled dream: Complementarity, continuity, and compensation: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Damon, W. (2002). Dominance, Sexism, and Inadequacy: Testing a Compensatory Conceptualization in a Sample of Heterosexual Men Involved in SM: Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality Vol 14(4) 2002, 25-45.

- Dittmann, J., & Schuttler, R. (1990). Autoprotective mechanisms in patients with schizophrenic psychoses: Compensation and coping: Fortschritte der Neurologie, Psychiatrie Vol 58(12) Dec 1990, 473-483.

- Dixon, R. A., & Backman, L. (1999). Principles of compensation in cognitive neurorehabilitation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Domino, G. (1976). Compensatory aspects of dreams: An empirical test of Jung's theory: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Vol 34(4) Oct 1976, 658-662.

- Earleywine, M. S. (1991). Personality risk for alcoholism, drinking habits, and compensatory responses to cues for alcohol: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Eischeid, A. W. (2001). Compensatory self-presentation strategies of physique-anxious individuals.

Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. - Eisenstadt, D., Hicks, J. L., McIntyre, K., Rivers, J. A., & Cahill, M. (2006). Two Paths of Defense: Specific Versus Compensatory Reactions to Self-threat: Self and Identity Vol 5(1) Jan-Mar 2006, 35-50.

- Eiser, J. R. (1999). Et in Arcadia ego: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 214-217.

- Elliott, J. E. (1992). Compensatory buffers, depression, and irrational beliefs: Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy Vol 6(3) Fal 1992, 175-184.

- Elsner, R. J. F. (2002). Changes in eating behavior during the aging process: Eating Behaviors Vol 3(1) Spr 2002, 15-43.

- Erber, R. (1999). The tireless social psychologist: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 217-219.

- Fosshage, J. L. (1997). "Compensatory" or "primary": An alternative view. Discussion of Marian Tolpin's "Compensatory Structures: Paths to the Restoration of the Self". Mahwah, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Gilger, J.

W., Hanebuth, E., Smith, S. D., & Pennington, B. F. (1996). Differential risk for developmental reading disorders in the offspring of compensated versus noncompensated parents: Reading and Writing Vol 8(5) Oct 1996, 407-417.

W., Hanebuth, E., Smith, S. D., & Pennington, B. F. (1996). Differential risk for developmental reading disorders in the offspring of compensated versus noncompensated parents: Reading and Writing Vol 8(5) Oct 1996, 407-417. - Greenberg, J. (1999). On imagined cultures and real ones, and the evolution and operation of human goal striving: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 220-224.

- Greve, W., & Wentura, D. (2007). Personal and subpersonal regulation of human development: Beyond complementary categories: Human Development Vol 50(4) Jul 2007, 201-207.

- Heine, S. J., Kitayama, S., & Lehman, D. R. (2001). Cultural differences in self-evaluation: Japanese readily accept negative self-relevant information: Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology Vol 32(4) Jul 2001, 434-443.

- Hortacsu, N. (1973). Reactions of advantaged and disadvantaged to a situation of inequity: Dissertation Abstracts International Vol.

- Kalizhnyuk, E. S. (1983). Situationally induced reactions of compensation and decompensation in infantile cerebral paralysis: Zhurnal Nevropatologii i Psikhiatrii imeni S S Korsakova Vol 83(10) 1983, 1552-1556.

- Kasari, C., Chamberlain, B., & Bauminger, N. (2001). Social emotions and social relationships: Can children with autism compensate? Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Kasser, T. (1999). I-D compensation theory and intrinsic/extrinsic goals: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 224-226.

- Kennick, C. K. (1999). Of hunter-gatherers, fundamental social motives, and person-situation interactions: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 226-229.

- Kessler, J. J., & Wiener, Y. (1972). Self-consistency and inequity dissonance as factors in undercompensation: Organizational Behavior & Human Performance Vol 8(3) Dec 1972, 456-466.

- Knauper, B., Rabiau, M., Cohen, O., & Patriciu, N. (2004). Compensatory Health Beliefs: Scale Development and Psychometric Properties: Psychology & Health Vol 19(5) Oct 2004, 607-624.

- Lancaster, J. (1975). Coping mechanisms for the working mother: American Journal of Nursing Vol 75(8) Aug 1975, 1322-1323.

- Leary, M. R., & Cottrell, C. A. (1999). Evolution of the self, the need to belong, and life in a delayed-return environment: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 229-232.

- Lehman, H. C. (1928). Review of The Lure of Superiority: Journal of Applied Psychology Vol 12(4) Aug 1928, 451-453.

- Li, K. Z. H., Lindenberger, U., Freund, A. M., & Baltes, P. B. (2001). Walking while memorizing: Age-related differences in compensatory behavior: Psychological Science Vol 12(3) May 2001, 230-237.

- Martin, L. L. (1999). Another look at I-D compensation theory: Addressing some concerns and misconceptions: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 257-267.

- Martin, L. L. (1999). I-D compensation theory: Some implications of trying to satisfy immediate-return needs in a delayed-return culture: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 195-208.

- McKee, H. (2006). The british children evacuees: A life-span developmental perspective on resilience and psychological well-being.

Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering. - Miller, C. T., & Myers, A. M. (1998). Compensating for prejudice: How heavyweight people (and others) control outcomes despite prejudice. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Miller, C. T., Rothblum, E. D., Felicio, D., & Brand, P. (1995). Compensating for stigma: Obese and nonobese women's reactions to being visible: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Vol 21(10) Oct 1995, 1093-1106.

- Miller, C. T., Rothblum, E. D., Felicio, D., & Brand, P. (2000). Compensating for stigma: Obese and non obese women's reactions to being visible. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Minkowski, E., Targowla, R., & Ziadeh, S. (2001). A contribution to the study of autism: The interrogative attitude: Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology Vol 8(4) Dec 2001, 271-278.

- Motazedian, N. (1999). Variables that affect job satisfaction in home health nurses. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

- Naudin, J., & Azorin, J.-M. (2001). Schizophrenia and the void: Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology Vol 8(4) Dec 2001, 291-293.

- O'Maille, P. S. (2001). The impact of compensation on symptom distortion in chronic pain patients: An examination of MMPI-2 symptom distortion measures. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

- Pachoud, B. (2001). Reading Minkowski with Husserl: Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology Vol 8(4) Dec 2001, 299-301.

- Palombo, J. (1991). Neurocognitive differences, self cohesion, and incoherent self narratives: Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal Vol 8(6) Dec 1991, 449-472.

- Payne, A. D. (1983). Communication in the context of failure: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Pyszczynski, T., & Goldenberg, J. L. (1999). Self-awareness, future-orientation, and human social motivation: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 232-235.

- Reichborn-Kjennerud, T.

, Bulik, C. M., Sullivan, P. F., Tambs, K., & Harris, J. R. (2004). Psychiatric and Medical Symptoms in Binge Eating in the Absence of Compensatory Behaviors: Obesity Research Vol 12(9) Sep 2004, 1445-1454.

, Bulik, C. M., Sullivan, P. F., Tambs, K., & Harris, J. R. (2004). Psychiatric and Medical Symptoms in Binge Eating in the Absence of Compensatory Behaviors: Obesity Research Vol 12(9) Sep 2004, 1445-1454. - Riediger, M., & Ebner, N. C. (2007). A broader perspective on three lifespan theories: Comment on Boerner and Jopp: Human Development Vol 50(4) Jul 2007, 196-200.

- Rieken, B. (2003). Compensation and overcompensation within folk tales: Zeitschrift fur Individualpsychologie Vol 28(2) 2003, 174-190.

- Robinson, E. S. (1920). The Compensatory Function of Make-Believe Play: Psychological Review Vol 27(6) Nov 1920, 429-439.

- Robinson, E. S. (1923). A concept of compensation and its psychological setting: The Journal of Abnormal Psychology and Social Psychology Vol 17(4) Jan-Mar 1923, 383-394.

- Roeder, P. C. (1996). Leading women: How women who are leaders evaluate the leadership of others. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Romanova, O. L. (1982). Experimental psychological investigation of the personality of patients suffering from physical defects: Zhurnal Nevropatologii i Psikhiatrii imeni S S Korsakova Vol 82(12) 1982, 1854-1858.

- Ross, S. R., Putnam, S. H., & Adams, K. M. (2006). Psychological Disturbance, Incomplete Effort, and Compensation-Seeking Status as Predictors of Neuropsychological Test Performance in Head Injury: Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology Vol 28(1) Jan 2006, 111-125.

- Rothermund, K., & Brandstadter, J. (2003). Coping With Deficits and Losses in Later Life: From Compensatory Action to Accommodation: Psychology and Aging Vol 18(4) Dec 2003, 896-905.

- Rudman, L. A., Dohn, M. C., & Fairchild, K. (2007). Implicit self-esteem compensation: Automatic threat defense: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Vol 93(5) Nov 2007, 798-813.

- Ryan, R. M., & Couchman, C. E. (1999). Comparing "immediate-return" and "basic psychological" needs: A Self-Determination Theory perspective: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 235-239.

- Schachter, M. (1972). Study of acute psychotic episodes in mentally retarded adolescents and the idea of "decompensation" in child psychiatry: Annales Medico-Psychologiques Vol 1(4) Apr 1972, 507-528.

- Schultheiss, O. C., & Brunstein, J. C. (2000). Choice of difficult tasks as a strategy of compensating for identity-relevant failure: Journal of Research in Personality Vol 34(2) Jun 2000, 269-277.

- Senon, J. L., Lafay, N., & Padet, N. (2003). Pharmacopsychoses: L'Encephale Vol 29(5,Pt2) Sep 2003, 8-11.

- Seta, J. J., Seta, C. E., & McElroy, T. (2003). Attributional biases in the service of stereotype maintenance: A schema-maintenance through compensation analysis: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Vol 29(2) Feb 2003, 151-163.

- Shaver, P. R., & Hendin, H. M. (1999). Imagined hunter-gatherers, happiness without a self, and the preference of neurotic individuals for immediate relief when frightened: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 239-244.

- Silverstein, M. L. (2001). Clinical identification of compensatory structures on projective tests: A self psychological approach: Journal of Personality Assessment Vol 76(3) Jun 2001, 517-536.

- Sipps, G. J. (1982). Masculinity and femininity: Construct validity and unconscious compensation using the EPAQ and TAT: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Solomon, M. (1917). Review of Study of organ inferiority and its psychical compensation: A contribution to clinical medicine: The Journal of Abnormal Psychology Vol 12(5) Dec 1917, 348-351.

- Solomon, S. (1999). Death and the evolution of human social motives: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 244-247.

- Stanghellini, G. (2001). A dialectical conception of autism: Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology Vol 8(4) Dec 2001, 295-298.

- Strube, M. J., Hanson, J. S., & Fargher, K. (1999). Back to basics in the search for the motives of human behavior? : Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 247-250.

- Tolpin, M. (1997). Compensatory structures: Paths to the restoration of the self. Mahwah, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Tolpin, M. (1997). Response to Fosshage. Mahwah, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Trijsburg, R. W., Bal, J. A., Parsowa, W. P., Erdman, R. A., & et al. (1990). Prediction of physical indisposition with the help of a questionnaire for measuring denial and overcompensation: Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics Vol 51(4) 1990, 193-202.

- Usui, W. M. (1977). Causal relations among types of formal and informal social participation: A test of the generalization, cumulative, and compensation hypotheses: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- van Amstel, H., & van der Geest, S. (2004). Doctors and retribution: The hospitalisation of compensation claims in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea: Social Science & Medicine Vol 59(10) Nov 2004, 2087-2094.

- Vaughan, W. F. (1926). The psychology of compensation: Psychological Review Vol 33(6) Nov 1926, 467-479.

- Weary, G., Jacobson, J. A., & Vaughn, L. A. (1999). I-D compensation theory and the Causal Uncertainty model: Related models of self-control? : Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 251-253.

- Wicklund, R. A. (1999). The disappearance of defensiveness via I-D compensation: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 254-256.

- Wood, J. V., Giordano-Beech, M., & Ducharme, M. J. (1999). Compensating for failure through social comparison: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Vol 25(11) Nov 1999, 1370-1386.

- Zemore, R. W., & Greenough, T. J. (1973). Reduction of ego threat following attributive projection: Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association 1973, 343-344.

- Ziegelmann, J. P., & Lippke, S. (2007). Use of selection, optimization, and compensation strategies in health self-regulation: Interplay with resources and successful development: Journal of Aging and Health Vol 19(3) Jun 2007, 500-518.

- Christopher Lasch (1979).

The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations. New York: Norton.

The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations. New York: Norton.

External links

- Claude S. Fisher: Comment On “Anxiety”: Compensation In Social History

- http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/HStein/qu-comp.htm

- http://www.infinityinst.com/articles/alfred_adler.htm

- http://everything2.com/index.pl?node_id=535671

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |

Compensation (defence mechanism) | Psychology Wiki

Assessment | Biopsychology | Comparative | Cognitive | Developmental | Language | Individual differences | Personality | Philosophy | Social |

Methods | Statistics | Clinical | Educational | Industrial | Professional items | World psychology |

Clinical: Approaches · Group therapy · Techniques · Types of problem · Areas of specialism · Taxonomies · Therapeutic issues · Modes of delivery · Model translation project · Personal experiences ·

In psychoanalysis compensation has a more specific meaning and is the name of a defence mechanism. In psychology, compensation is a strategy whereby one covers up, consciously or unconsciously, weaknesses, frustrations, desires, feelings of inadequacy or incompetence in one life area through the gratification or (drive towards) excellence in another area. Compensation can cover up either real or imagined deficiencies and personal or physical inferiority. The compensation strategy, however does not truly address the source of this inferiority. Positive compensations may help one to overcome one’s difficulties. On the other hand, negative compensations do not, which results in a reinforced feeling of inferiority. There are two kinds of negative compensation:

In psychology, compensation is a strategy whereby one covers up, consciously or unconsciously, weaknesses, frustrations, desires, feelings of inadequacy or incompetence in one life area through the gratification or (drive towards) excellence in another area. Compensation can cover up either real or imagined deficiencies and personal or physical inferiority. The compensation strategy, however does not truly address the source of this inferiority. Positive compensations may help one to overcome one’s difficulties. On the other hand, negative compensations do not, which results in a reinforced feeling of inferiority. There are two kinds of negative compensation:

Overcompensation, characterized by a superiority goal, leads to striving for power, dominance, self-esteem and self-devaluation.

Undercompensation, which includes a demand for help, leads to a lack of courage and a fear for life.

A well-known example of failing overcompensation, is observed in people going through a the midlife-crisis. Approaching midlife many people (especially men) lack the energy to maintain their psychological defenses, including their compensatory acts.

Approaching midlife many people (especially men) lack the energy to maintain their psychological defenses, including their compensatory acts.

Contents

- 1 Origin:

- 2 Cultural implications:

- 3 See also

- 4 References

- 5 External links

Origin:

Alfred Adler, founder of the school of individual psychology, introduced the term compensation in relation to inferiority feelings. In his book Study of Organ Inferiority and Its Physical Compensation (1907) he describes this relationship: Each individual has feelings of inferiority. Additionally, Adler states that there is a strong, natural tendency to conceal these feelings, since they are regarded as a sign of weakness. Therefore they find their expression in a striving for superiority. This mechanism may explain why some disabled people come to excel in a certain sphere of activity, see for example: Stevie Wonder, Glenn Cunningham, and Demosthenes. (Interestingly, Adler's interest in the phenomenon developed from his knowledge that he was shy and yet that he pushed himself to give academic lectures to auditoriums of students. ) This striving can manifest itself in many different ways, therefore each individual has his or her own way of attempting to achieve perfection.

) This striving can manifest itself in many different ways, therefore each individual has his or her own way of attempting to achieve perfection.

Thus, Alfred Adler transferred this idea of compensation to the area of psychic training. Contemporary psychoanalysts like Alexander Müller, Kurt Adler, Sophia de Vries, Alexander Neuer and Henry Stein elaborated on the theory of Adler in many different areas.

Cultural implications:

Christopher Lasch, a well-known American historian and social critic described in his book The Culture of Narcissism (1979) the North American society in the 1980’s as one with a narcissistic color. Narcissism in psychoanalytic theory can be seen in the light of compensation: people who are narcissistic suppress feelings of low self-esteem by talking highly about themselves and making contact with persons they admire. Lasch also describes the idea (of Melanie Klein) that narcissistic children try to compensate for their jealousy and anger by fantasizing about power, beauty and richness. The narcissistic society Lasch describes is characterized by worship of consumption, an excessive fear of aging and death, a fascination with fame, and a fear of dependency.

The narcissistic society Lasch describes is characterized by worship of consumption, an excessive fear of aging and death, a fascination with fame, and a fear of dependency.

The worship of consuming as Lasch terms it, is described in an article by Allison J. Pugh: From compensation to ‘childhood wonder’. Today’s market economy acquisition of commodities is an important factor in the creation of experience and identity in people’s lives. Consumption therefore has been put forward as a means of compensation. The strong symbolism of using goods to convey human relationships, can for example urge parents into various act of consumption in order to compensate for their guilt. On the one hand parents may feel responsible to make up for a perceived absence in their own youth (e.g. being part of a poverty-stricken family in childhood), and are therefore keen to ensure that their offspring never need to endure a similar loss. When guilt is directed towards something amiss in the life of their offspring (e. g. a family going through a divorce situation) offering of consumer goods can be interpreted as a compensatory reparative statement on behalf of the parent, a symbolic substitute for care.

g. a family going through a divorce situation) offering of consumer goods can be interpreted as a compensatory reparative statement on behalf of the parent, a symbolic substitute for care.

See also

Compensation neurosis

References

- Ambrogne, J. A. (1999). Patterns of compensation in alcohol-dependent women. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

- Area, R., Garcia-Caballero, A., Gomez, I., Somoza, M. J., Garcia-Lado, I., Recimil, M. J., et al. (2003). Conscious Compensations for Thought Insertion: Psychopathology Vol 36(3) May-Jun 2003, 129-131.

- Backman, L. (1989). Varieties of memory compensation by older adults in episodic remembering. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Jones, E. E. (1978). When self-presentation is constrained by the target's knowledge: Consistency and compensation: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Vol 36(6) Jun 1978, 608-618.

- Boerner, K., & Jopp, D. (2007). Improvement/maintenance and reorientation as central features of coping with major life change and loss: Contributions of three life-span theories: Human Development Vol 50(4) Jul 2007, 171-195.

- Boker, W., & et al. (1984). Self-healing strategies among schizophrenics: Attempts at compensation for basic disorders: Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Vol 69(5) May 1984, 373-378.

- Boney-McCoy, S., Gibbons, F. X., & Gerrard, M. (1999). Self-esteem, compensatory self-enhancement, and the consideration of health risk: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Vol 25(8) Aug 1999, 954-965.

- Bratt, C. (1999). Consumers' environmental beahvior: Generalized, sector-based, or compensatory? : Environment and Behavior Vol 31(1) Jan 1999, 28-44.

- Brotemarkle, R. A. (1930). Review of The lure of superiority: Psychological Bulletin Vol 27(1) Jan 1930, 72-73.

- Burka, A. A. (1983). The emotional reality of a learning disability: Annals of Dyslexia Vol 33 1983, 289-301.

- Casement, A. (2006). The shadow. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Cervone, D., & Rafaeli-Mor, N. (1999). Living in the future in the past: on the origins and expression of self-regulatory abilities: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 209-212.

- Chalus, G. A. (1976). Defensive compensation as a response to ego threat: A replication: Psychological Reports Vol 38(3, Pt 1) Jun 1976, 699-702.

- Chiland, C. (1992). Transsexualism and psychotic decompensation at adolescence. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Codina, N. (1988). Adler: A proposal for the study of leisure time activities as "compensation." Revista de Historia de la Psicologia Vol 9(1) Jan-Mar 1988, 103-110.

- Coleman, R. L., & Croake, J. W. (1987). Organ inferiority and measured overcompensation: Individual Psychology: Journal of Adlerian Theory, Research & Practice Vol 43(3) Sep 1987, 364-369.

- Colman, S. V. (1991). The sibling of the retarded child: Self-concept, deficit compensation motivation, and perceived parental behavior: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). The rejoining of immediacy and delay: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 213-214.

- Dallett, J. O. (1974). The effect of sensory and social variables on the recalled dream: Complementarity, continuity, and compensation: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Damon, W. (2002). Dominance, Sexism, and Inadequacy: Testing a Compensatory Conceptualization in a Sample of Heterosexual Men Involved in SM: Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality Vol 14(4) 2002, 25-45.

- Dittmann, J., & Schuttler, R. (1990). Autoprotective mechanisms in patients with schizophrenic psychoses: Compensation and coping: Fortschritte der Neurologie, Psychiatrie Vol 58(12) Dec 1990, 473-483.

- Dixon, R. A., & Backman, L. (1999). Principles of compensation in cognitive neurorehabilitation. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

- Domino, G. (1976). Compensatory aspects of dreams: An empirical test of Jung's theory: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Vol 34(4) Oct 1976, 658-662.

- Earleywine, M. S. (1991). Personality risk for alcoholism, drinking habits, and compensatory responses to cues for alcohol: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Eischeid, A. W. (2001). Compensatory self-presentation strategies of physique-anxious individuals. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

- Eisenstadt, D., Hicks, J. L., McIntyre, K., Rivers, J. A., & Cahill, M. (2006). Two Paths of Defense: Specific Versus Compensatory Reactions to Self-threat: Self and Identity Vol 5(1) Jan-Mar 2006, 35-50.

- Eiser, J. R. (1999). Et in Arcadia ego: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 214-217.

- Elliott, J. E. (1992). Compensatory buffers, depression, and irrational beliefs: Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy Vol 6(3) Fal 1992, 175-184.

- Elsner, R. J. F. (2002). Changes in eating behavior during the aging process: Eating Behaviors Vol 3(1) Spr 2002, 15-43.

- Erber, R. (1999). The tireless social psychologist: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 217-219.

- Fosshage, J. L. (1997). "Compensatory" or "primary": An alternative view. Discussion of Marian Tolpin's "Compensatory Structures: Paths to the Restoration of the Self". Mahwah, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Gilger, J. W., Hanebuth, E., Smith, S. D., & Pennington, B. F. (1996). Differential risk for developmental reading disorders in the offspring of compensated versus noncompensated parents: Reading and Writing Vol 8(5) Oct 1996, 407-417.

- Greenberg, J. (1999). On imagined cultures and real ones, and the evolution and operation of human goal striving: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 220-224.

- Greve, W., & Wentura, D. (2007). Personal and subpersonal regulation of human development: Beyond complementary categories: Human Development Vol 50(4) Jul 2007, 201-207.

- Heine, S. J., Kitayama, S., & Lehman, D. R. (2001). Cultural differences in self-evaluation: Japanese readily accept negative self-relevant information: Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology Vol 32(4) Jul 2001, 434-443.

- Hortacsu, N. (1973). Reactions of advantaged and disadvantaged to a situation of inequity: Dissertation Abstracts International Vol.

- Kalizhnyuk, E. S. (1983). Situationally induced reactions of compensation and decompensation in infantile cerebral paralysis: Zhurnal Nevropatologii i Psikhiatrii imeni S S Korsakova Vol 83(10) 1983, 1552-1556.

- Kasari, C., Chamberlain, B., & Bauminger, N. (2001). Social emotions and social relationships: Can children with autism compensate? Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Kasser, T. (1999). I-D compensation theory and intrinsic/extrinsic goals: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 224-226.

- Kennick, C. K. (1999). Of hunter-gatherers, fundamental social motives, and person-situation interactions: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 226-229.

- Kessler, J. J., & Wiener, Y. (1972). Self-consistency and inequity dissonance as factors in undercompensation: Organizational Behavior & Human Performance Vol 8(3) Dec 1972, 456-466.

- Knauper, B., Rabiau, M., Cohen, O., & Patriciu, N. (2004). Compensatory Health Beliefs: Scale Development and Psychometric Properties: Psychology & Health Vol 19(5) Oct 2004, 607-624.

- Lancaster, J. (1975). Coping mechanisms for the working mother: American Journal of Nursing Vol 75(8) Aug 1975, 1322-1323.

- Leary, M. R., & Cottrell, C. A. (1999). Evolution of the self, the need to belong, and life in a delayed-return environment: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 229-232.

- Lehman, H. C. (1928). Review of The Lure of Superiority: Journal of Applied Psychology Vol 12(4) Aug 1928, 451-453.

- Li, K. Z. H., Lindenberger, U., Freund, A. M., & Baltes, P. B. (2001). Walking while memorizing: Age-related differences in compensatory behavior: Psychological Science Vol 12(3) May 2001, 230-237.

- Martin, L. L. (1999). Another look at I-D compensation theory: Addressing some concerns and misconceptions: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 257-267.

- Martin, L. L. (1999). I-D compensation theory: Some implications of trying to satisfy immediate-return needs in a delayed-return culture: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 195-208.

- McKee, H. (2006). The british children evacuees: A life-span developmental perspective on resilience and psychological well-being. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

- Miller, C. T., & Myers, A. M. (1998). Compensating for prejudice: How heavyweight people (and others) control outcomes despite prejudice. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Miller, C. T., Rothblum, E. D., Felicio, D., & Brand, P. (1995). Compensating for stigma: Obese and nonobese women's reactions to being visible: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Vol 21(10) Oct 1995, 1093-1106.

- Miller, C. T., Rothblum, E. D., Felicio, D., & Brand, P. (2000). Compensating for stigma: Obese and non obese women's reactions to being visible. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Minkowski, E., Targowla, R., & Ziadeh, S. (2001). A contribution to the study of autism: The interrogative attitude: Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology Vol 8(4) Dec 2001, 271-278.

- Motazedian, N. (1999). Variables that affect job satisfaction in home health nurses. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

- Naudin, J., & Azorin, J.-M. (2001). Schizophrenia and the void: Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology Vol 8(4) Dec 2001, 291-293.

- O'Maille, P. S. (2001). The impact of compensation on symptom distortion in chronic pain patients: An examination of MMPI-2 symptom distortion measures. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering.

- Pachoud, B. (2001). Reading Minkowski with Husserl: Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology Vol 8(4) Dec 2001, 299-301.

- Palombo, J. (1991). Neurocognitive differences, self cohesion, and incoherent self narratives: Child & Adolescent Social Work Journal Vol 8(6) Dec 1991, 449-472.

- Payne, A. D. (1983). Communication in the context of failure: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Pyszczynski, T., & Goldenberg, J. L. (1999). Self-awareness, future-orientation, and human social motivation: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 232-235.

- Reichborn-Kjennerud, T., Bulik, C. M., Sullivan, P. F., Tambs, K., & Harris, J. R. (2004). Psychiatric and Medical Symptoms in Binge Eating in the Absence of Compensatory Behaviors: Obesity Research Vol 12(9) Sep 2004, 1445-1454.

- Riediger, M., & Ebner, N. C. (2007). A broader perspective on three lifespan theories: Comment on Boerner and Jopp: Human Development Vol 50(4) Jul 2007, 196-200.

- Rieken, B. (2003). Compensation and overcompensation within folk tales: Zeitschrift fur Individualpsychologie Vol 28(2) 2003, 174-190.

- Robinson, E. S. (1920). The Compensatory Function of Make-Believe Play: Psychological Review Vol 27(6) Nov 1920, 429-439.

- Robinson, E. S. (1923).

A concept of compensation and its psychological setting: The Journal of Abnormal Psychology and Social Psychology Vol 17(4) Jan-Mar 1923, 383-394.

A concept of compensation and its psychological setting: The Journal of Abnormal Psychology and Social Psychology Vol 17(4) Jan-Mar 1923, 383-394. - Roeder, P. C. (1996). Leading women: How women who are leaders evaluate the leadership of others. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences.

- Romanova, O. L. (1982). Experimental psychological investigation of the personality of patients suffering from physical defects: Zhurnal Nevropatologii i Psikhiatrii imeni S S Korsakova Vol 82(12) 1982, 1854-1858.

- Ross, S. R., Putnam, S. H., & Adams, K. M. (2006). Psychological Disturbance, Incomplete Effort, and Compensation-Seeking Status as Predictors of Neuropsychological Test Performance in Head Injury: Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology Vol 28(1) Jan 2006, 111-125.

- Rothermund, K., & Brandstadter, J. (2003). Coping With Deficits and Losses in Later Life: From Compensatory Action to Accommodation: Psychology and Aging Vol 18(4) Dec 2003, 896-905.

- Rudman, L. A., Dohn, M. C., & Fairchild, K. (2007). Implicit self-esteem compensation: Automatic threat defense: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology Vol 93(5) Nov 2007, 798-813.

- Ryan, R. M., & Couchman, C. E. (1999). Comparing "immediate-return" and "basic psychological" needs: A Self-Determination Theory perspective: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 235-239.

- Schachter, M. (1972). Study of acute psychotic episodes in mentally retarded adolescents and the idea of "decompensation" in child psychiatry: Annales Medico-Psychologiques Vol 1(4) Apr 1972, 507-528.

- Schultheiss, O. C., & Brunstein, J. C. (2000). Choice of difficult tasks as a strategy of compensating for identity-relevant failure: Journal of Research in Personality Vol 34(2) Jun 2000, 269-277.

- Senon, J. L., Lafay, N., & Padet, N. (2003). Pharmacopsychoses: L'Encephale Vol 29(5,Pt2) Sep 2003, 8-11.

- Seta, J. J., Seta, C. E., & McElroy, T. (2003).

Attributional biases in the service of stereotype maintenance: A schema-maintenance through compensation analysis: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Vol 29(2) Feb 2003, 151-163.

Attributional biases in the service of stereotype maintenance: A schema-maintenance through compensation analysis: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Vol 29(2) Feb 2003, 151-163. - Shaver, P. R., & Hendin, H. M. (1999). Imagined hunter-gatherers, happiness without a self, and the preference of neurotic individuals for immediate relief when frightened: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 239-244.

- Silverstein, M. L. (2001). Clinical identification of compensatory structures on projective tests: A self psychological approach: Journal of Personality Assessment Vol 76(3) Jun 2001, 517-536.

- Sipps, G. J. (1982). Masculinity and femininity: Construct validity and unconscious compensation using the EPAQ and TAT: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- Solomon, M. (1917). Review of Study of organ inferiority and its psychical compensation: A contribution to clinical medicine: The Journal of Abnormal Psychology Vol 12(5) Dec 1917, 348-351.

- Solomon, S.

(1999). Death and the evolution of human social motives: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 244-247.

(1999). Death and the evolution of human social motives: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 244-247. - Stanghellini, G. (2001). A dialectical conception of autism: Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology Vol 8(4) Dec 2001, 295-298.

- Strube, M. J., Hanson, J. S., & Fargher, K. (1999). Back to basics in the search for the motives of human behavior? : Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 247-250.

- Tolpin, M. (1997). Compensatory structures: Paths to the restoration of the self. Mahwah, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Tolpin, M. (1997). Response to Fosshage. Mahwah, NJ: Analytic Press.

- Trijsburg, R. W., Bal, J. A., Parsowa, W. P., Erdman, R. A., & et al. (1990). Prediction of physical indisposition with the help of a questionnaire for measuring denial and overcompensation: Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics Vol 51(4) 1990, 193-202.

- Usui, W. M. (1977). Causal relations among types of formal and informal social participation: A test of the generalization, cumulative, and compensation hypotheses: Dissertation Abstracts International.

- van Amstel, H., & van der Geest, S. (2004). Doctors and retribution: The hospitalisation of compensation claims in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea: Social Science & Medicine Vol 59(10) Nov 2004, 2087-2094.

- Vaughan, W. F. (1926). The psychology of compensation: Psychological Review Vol 33(6) Nov 1926, 467-479.

- Weary, G., Jacobson, J. A., & Vaughn, L. A. (1999). I-D compensation theory and the Causal Uncertainty model: Related models of self-control? : Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 251-253.

- Wicklund, R. A. (1999). The disappearance of defensiveness via I-D compensation: Psychological Inquiry Vol 10(3) 1999, 254-256.

- Wood, J. V., Giordano-Beech, M., & Ducharme, M. J. (1999). Compensating for failure through social comparison: Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Vol 25(11) Nov 1999, 1370-1386.

- Zemore, R. W., & Greenough, T. J. (1973). Reduction of ego threat following attributive projection: Proceedings of the Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association 1973, 343-344.

- Ziegelmann, J. P., & Lippke, S. (2007). Use of selection, optimization, and compensation strategies in health self-regulation: Interplay with resources and successful development: Journal of Aging and Health Vol 19(3) Jun 2007, 500-518.

- Christopher Lasch (1979). The Culture of Narcissism: American Life in an Age of Diminishing Expectations. New York: Norton.

External links

- Claude S. Fisher: Comment On “Anxiety”: Compensation In Social History

- http://ourworld.compuserve.com/homepages/HStein/qu-comp.htm

- http://www.infinityinst.com/articles/alfred_adler.htm

- http://everything2.com/index.pl?node_id=535671

| This page uses Creative Commons Licensed content from Wikipedia (view authors). |

Compensation as a defense mechanism

Psychological defenses

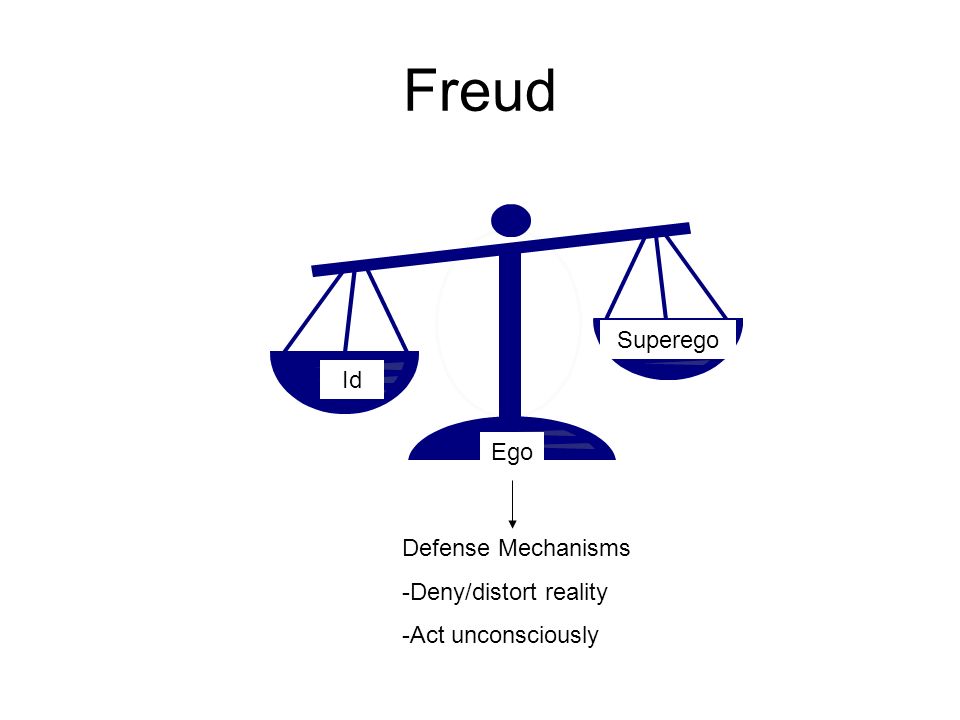

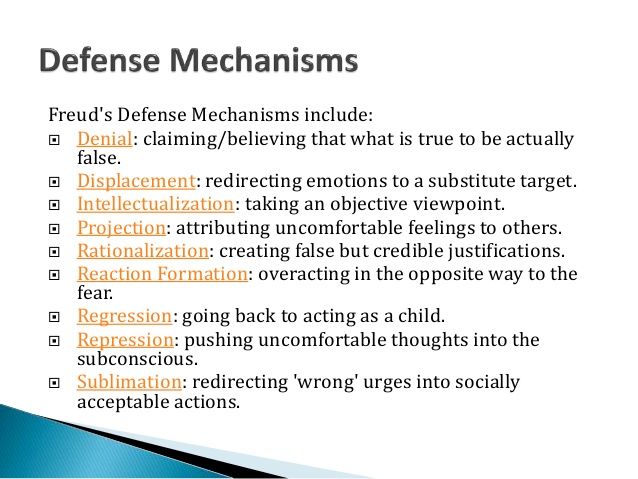

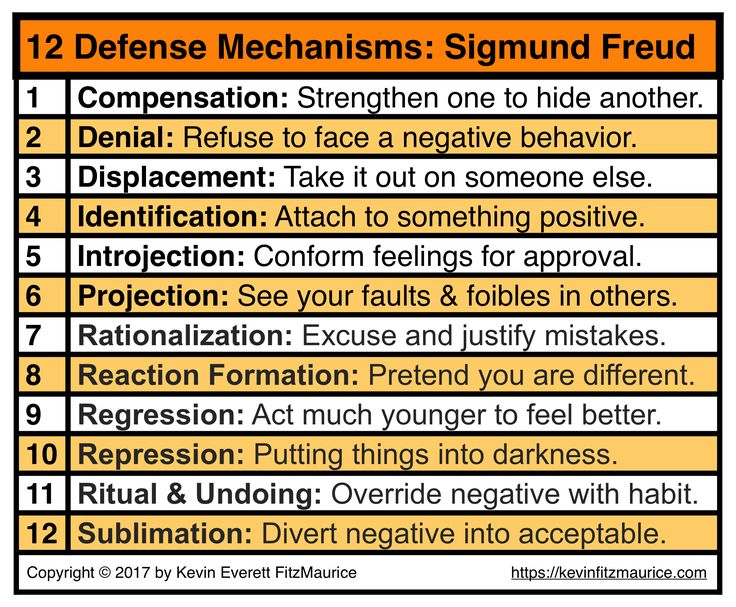

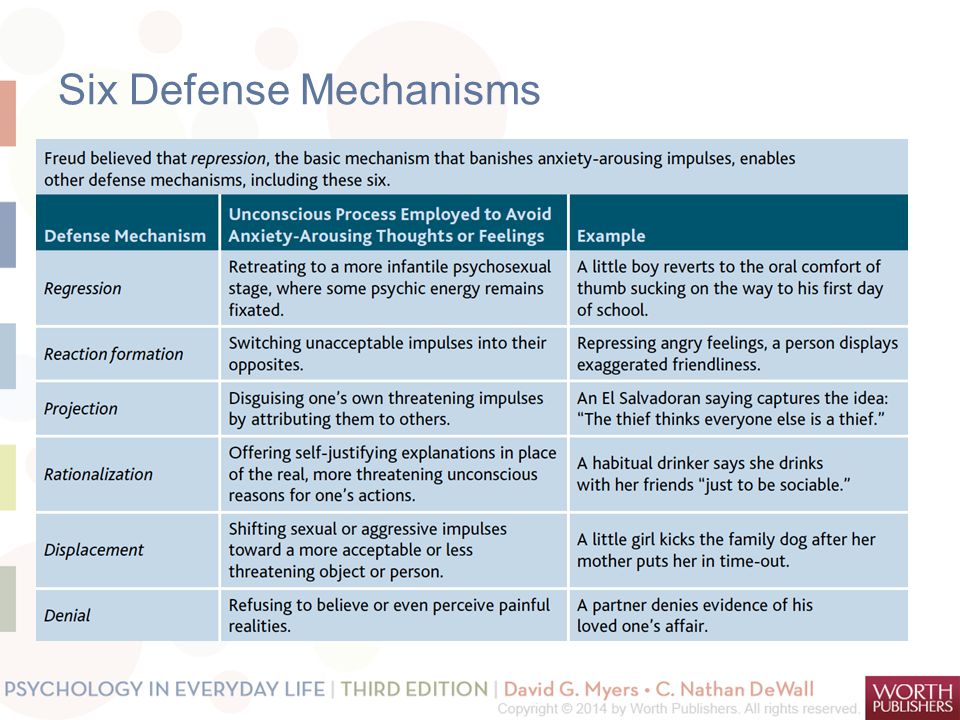

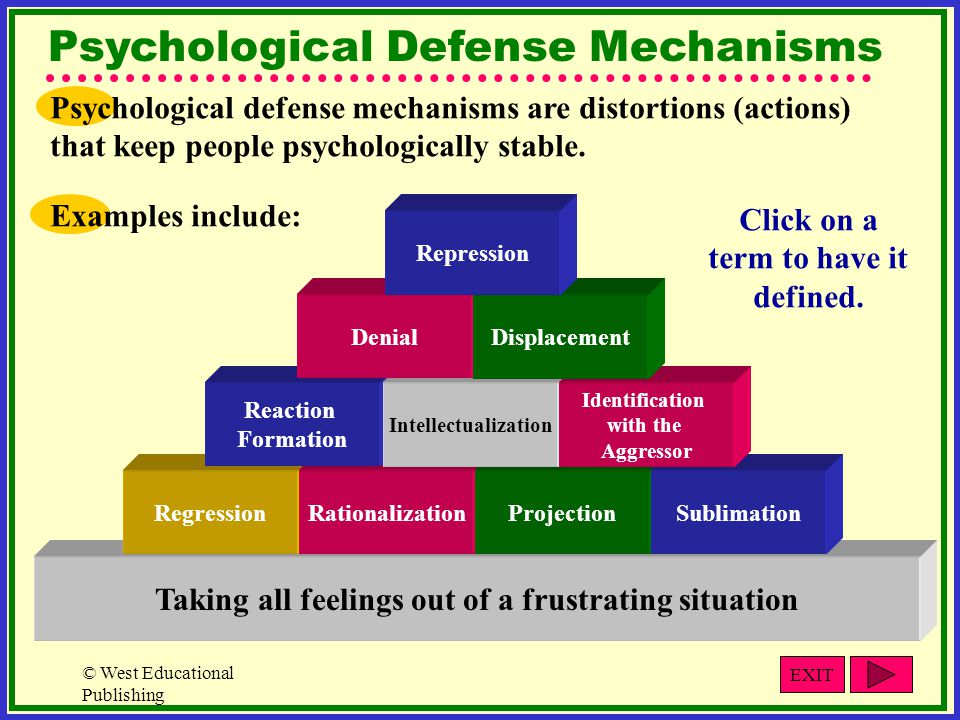

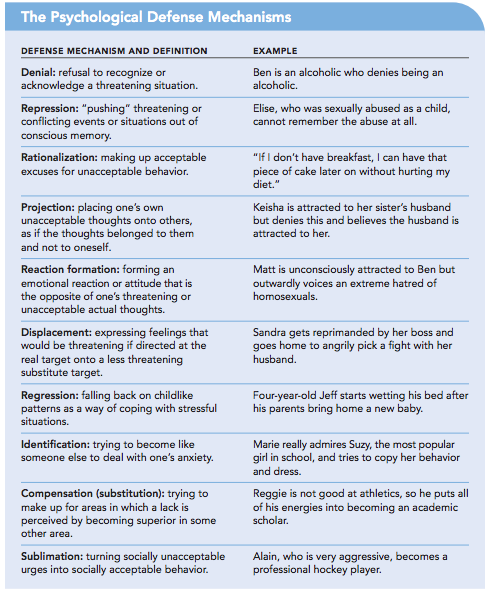

In 1894, Sigmund Freud in his work "Defensive neuropsychoses" for the first time introduces the concept of "psychic defense mechanism". By this term, the psychoanalyst meant the means of fighting the ego against painful or intolerable affects. We can say that defense mechanisms have an adaptive function, they are a kind of mental strategies, using which people get the opportunity to avoid stress or reduce the intensity of negative emotional experiences, such as anxiety, longing, feelings of hopelessness or inferiority, a state of internal conflict.

By this term, the psychoanalyst meant the means of fighting the ego against painful or intolerable affects. We can say that defense mechanisms have an adaptive function, they are a kind of mental strategies, using which people get the opportunity to avoid stress or reduce the intensity of negative emotional experiences, such as anxiety, longing, feelings of hopelessness or inferiority, a state of internal conflict.

Note 1

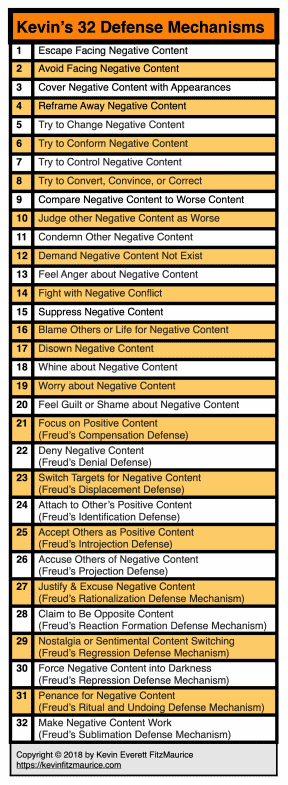

Currently, more than twenty forms of defense mechanisms are mentioned in the psychological science and among practitioners, while some of them are considered by individual authors as a special case of other, more extensive, mental defenses.

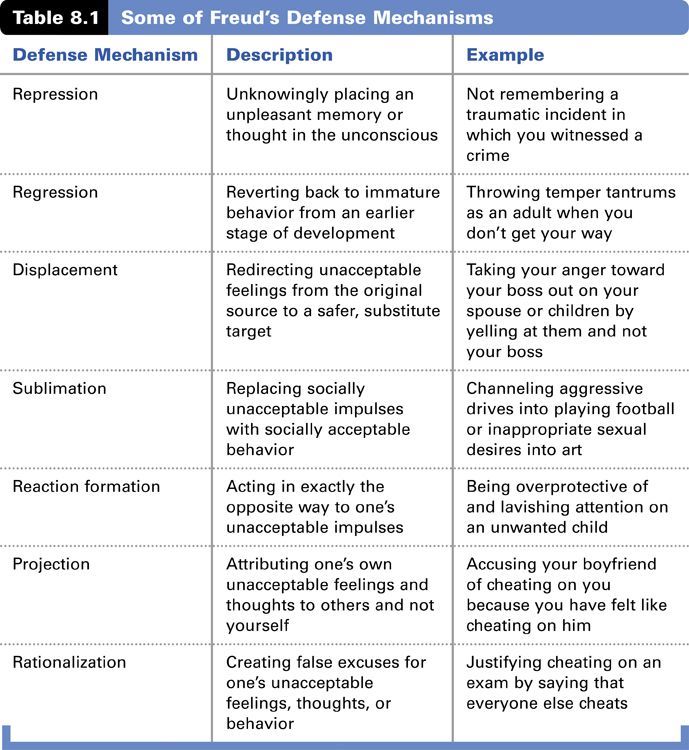

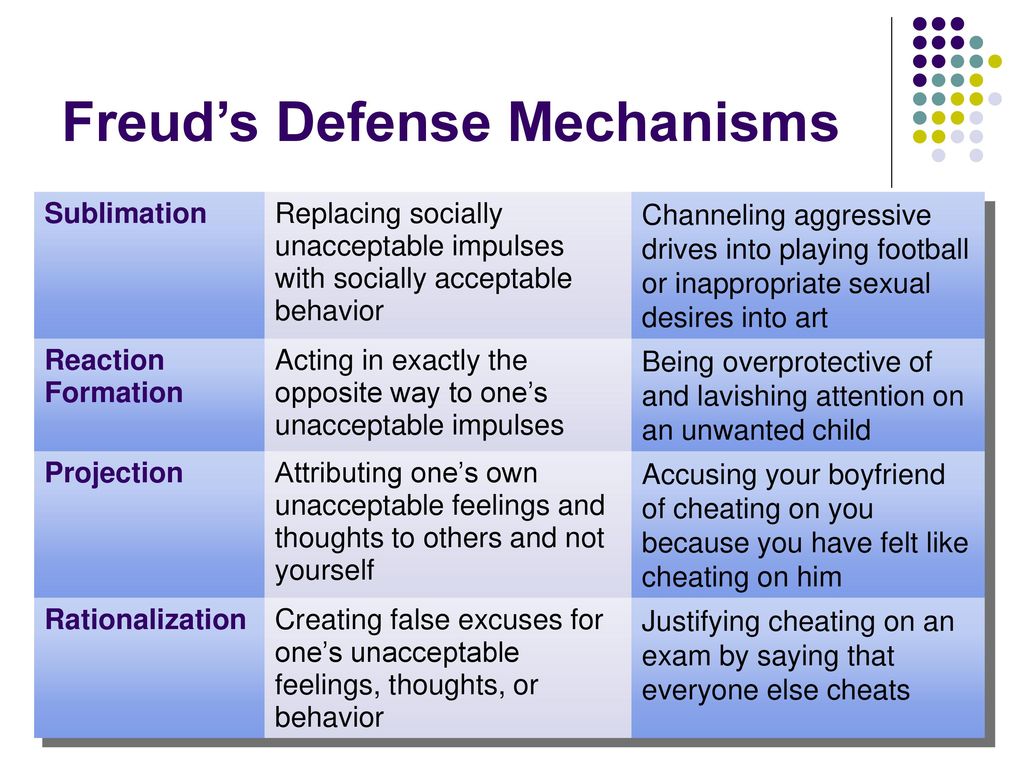

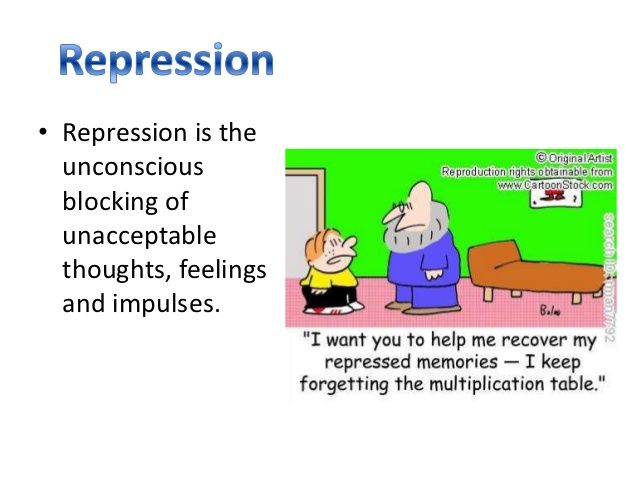

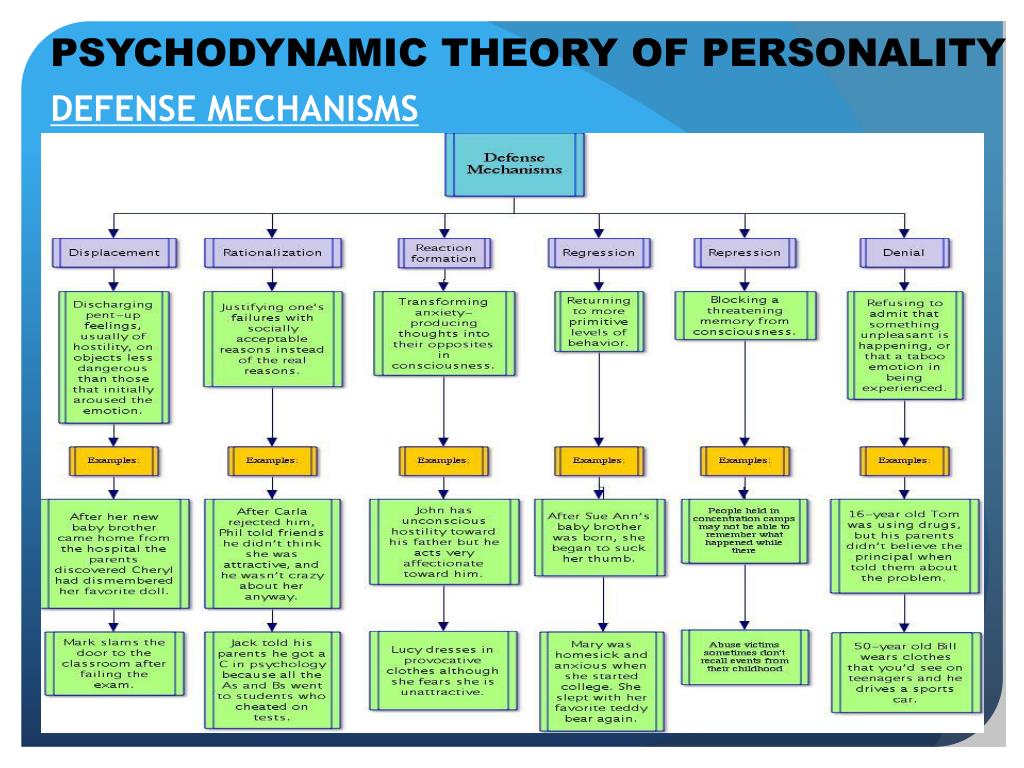

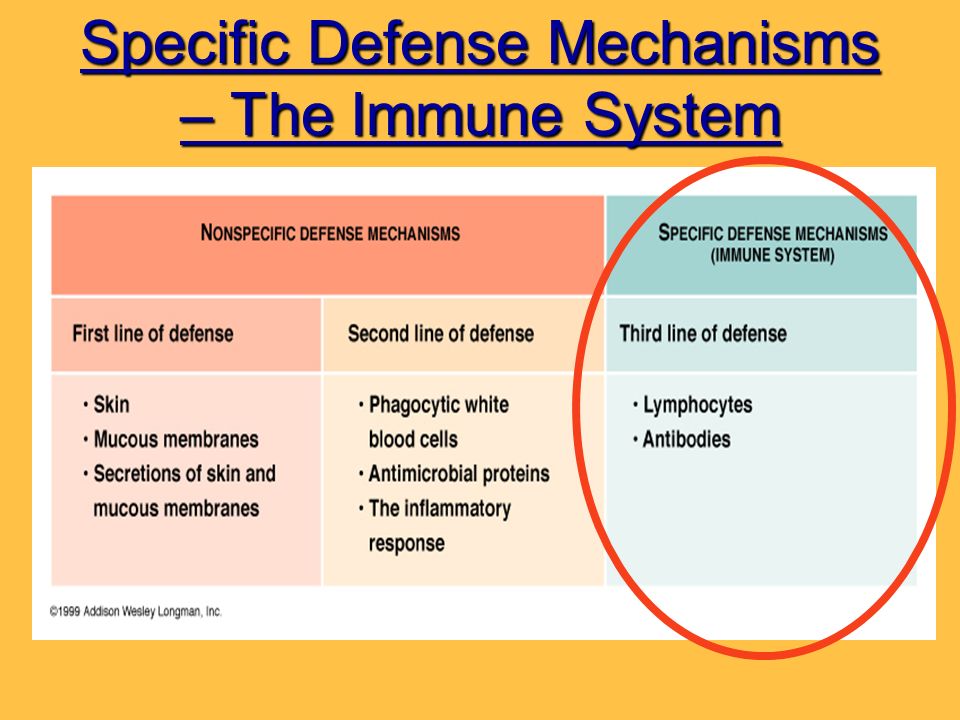

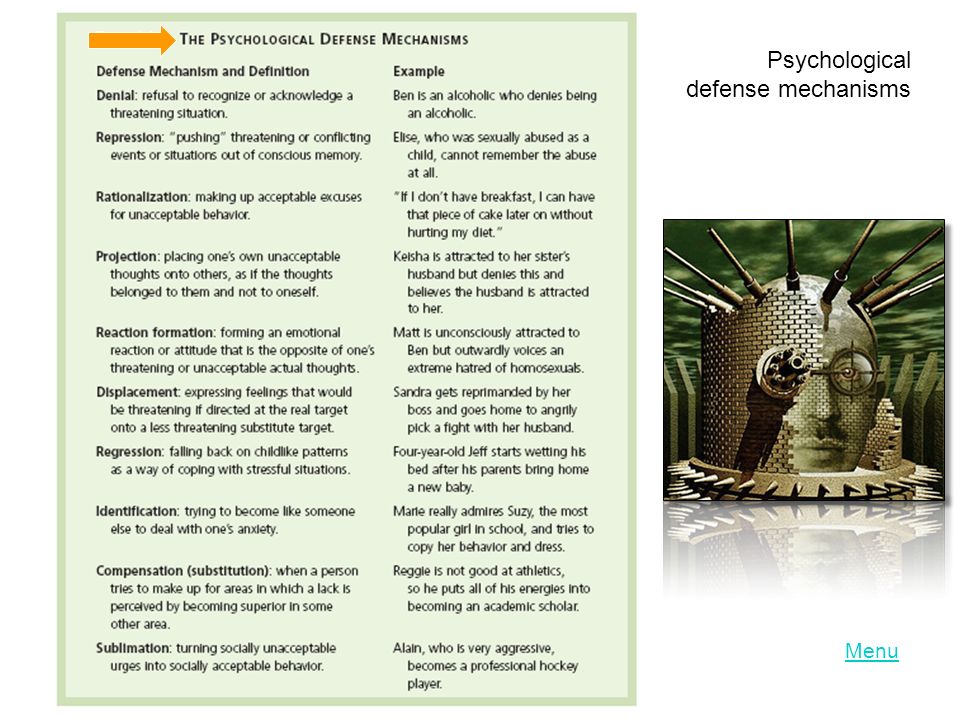

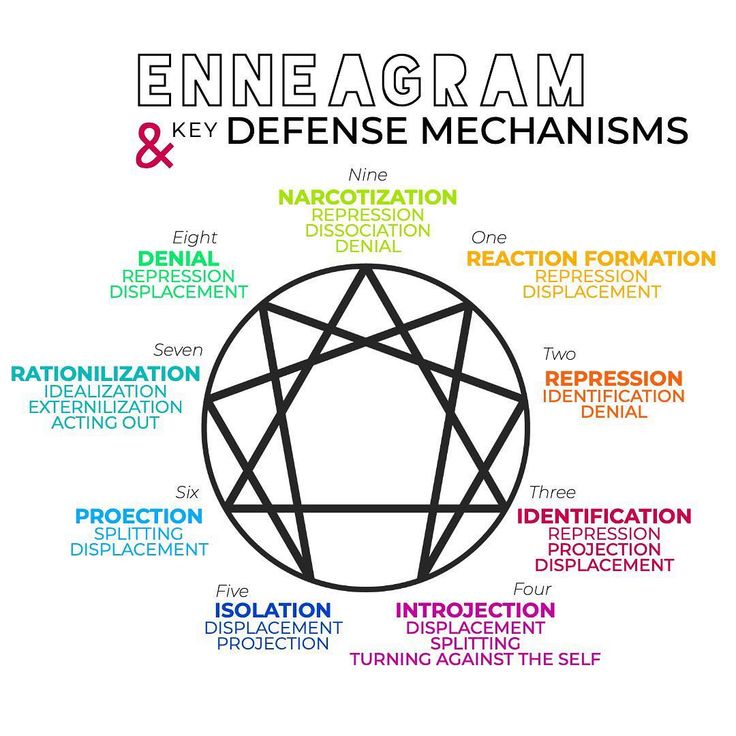

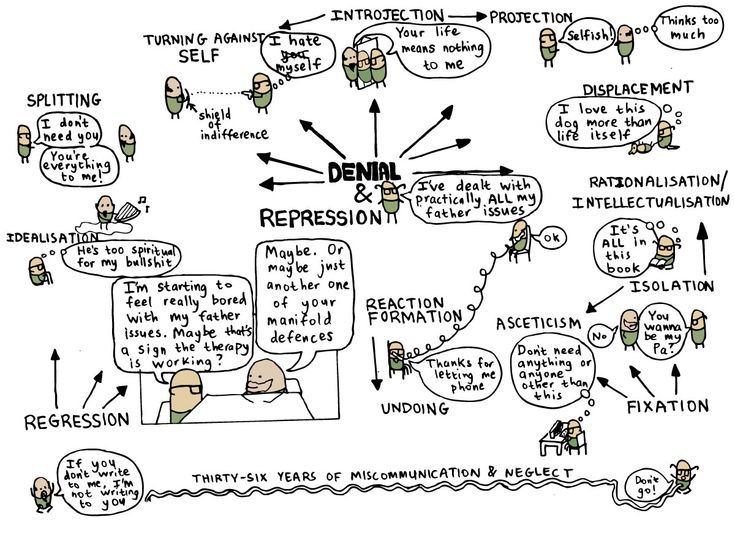

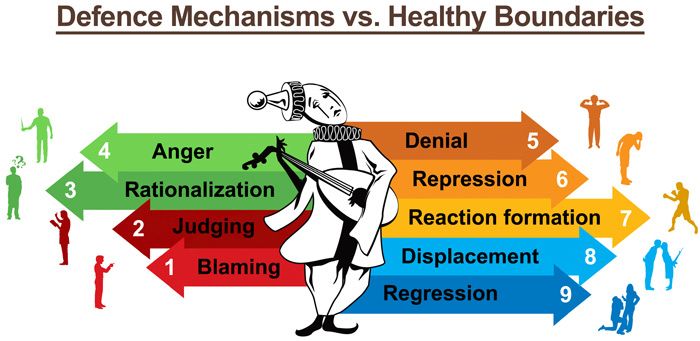

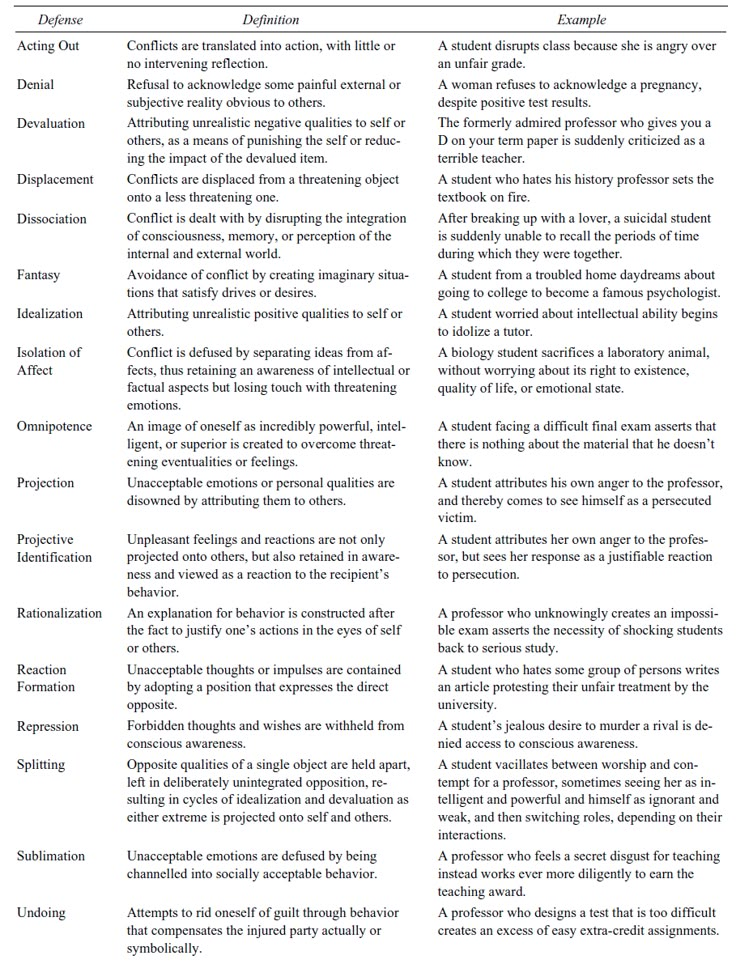

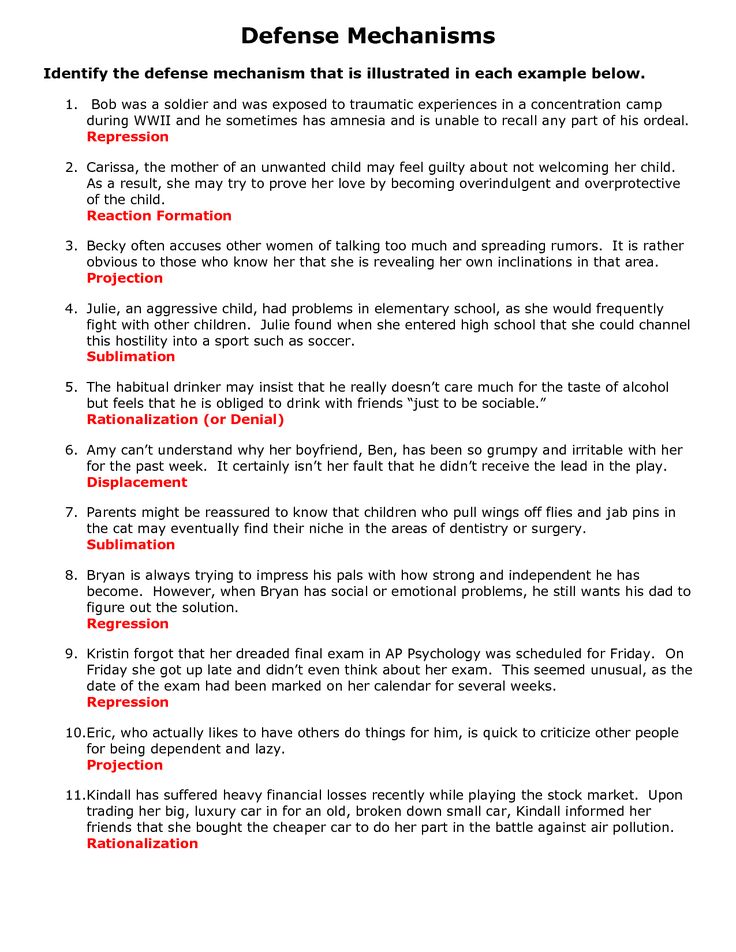

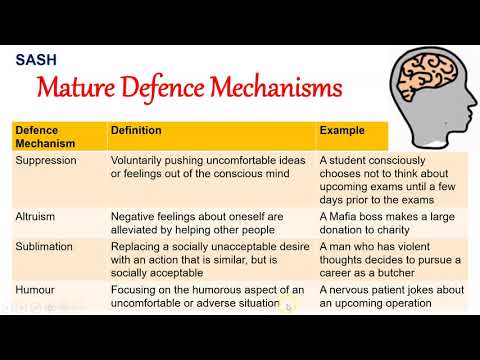

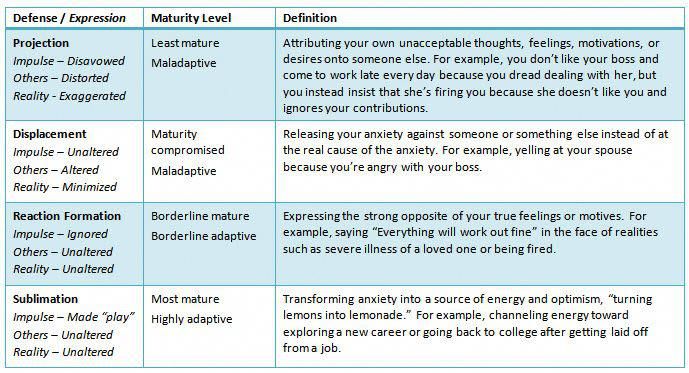

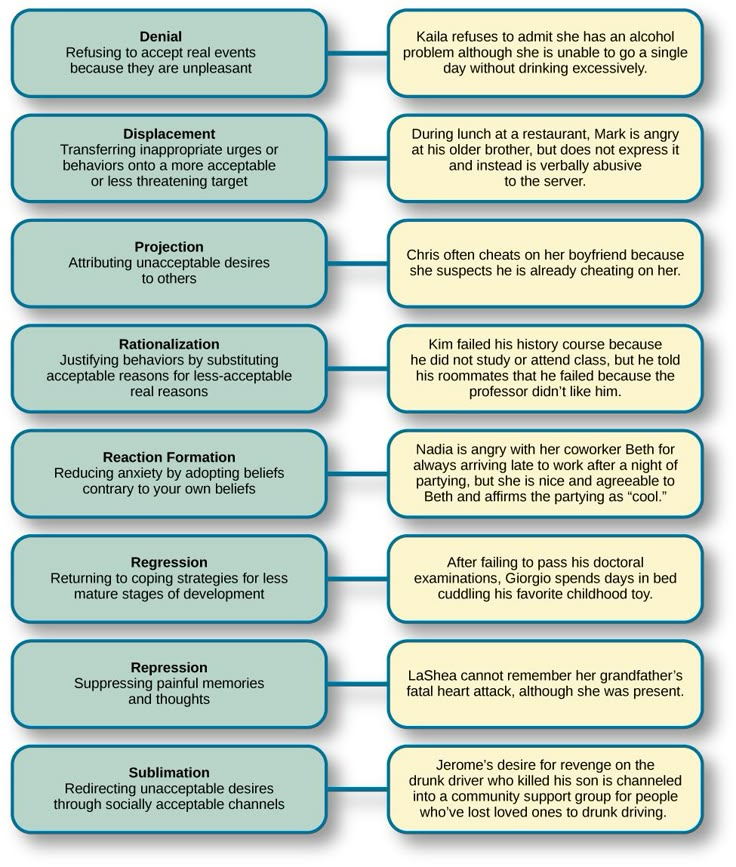

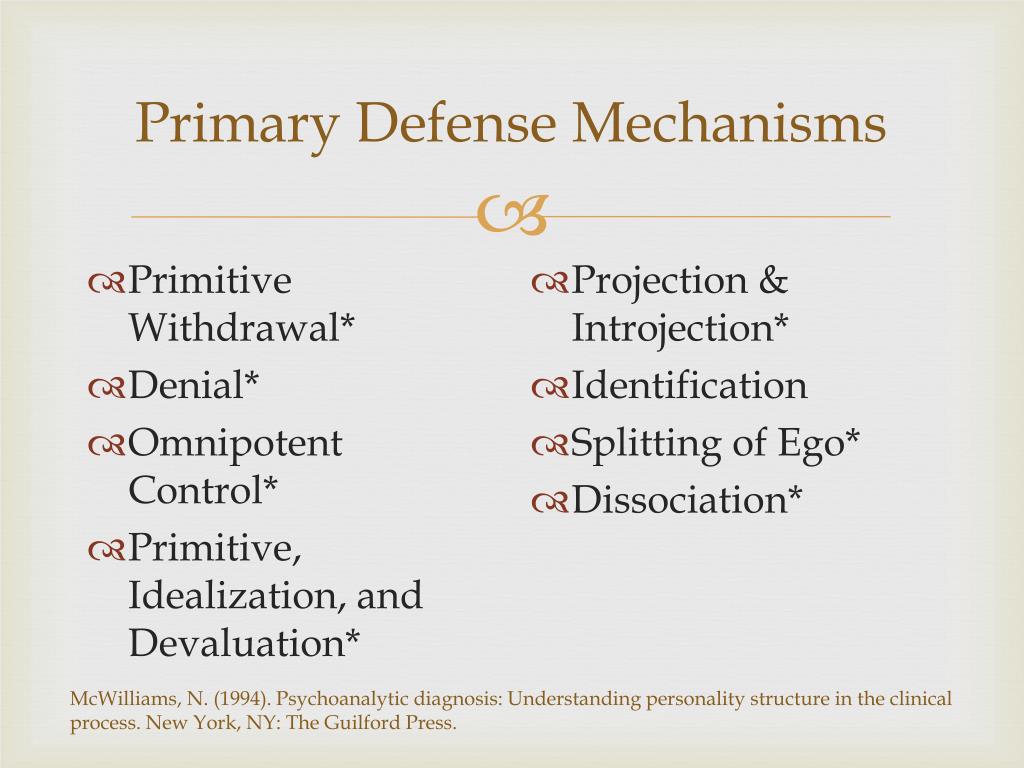

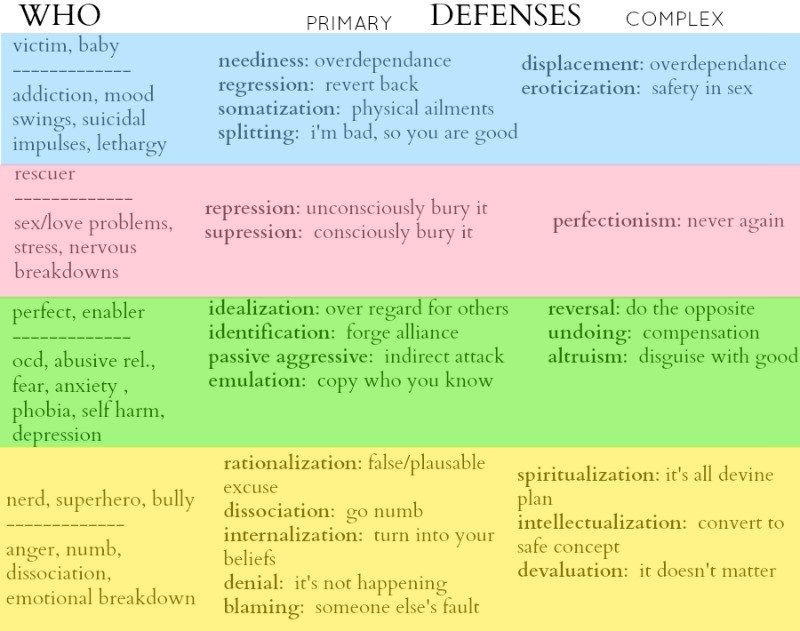

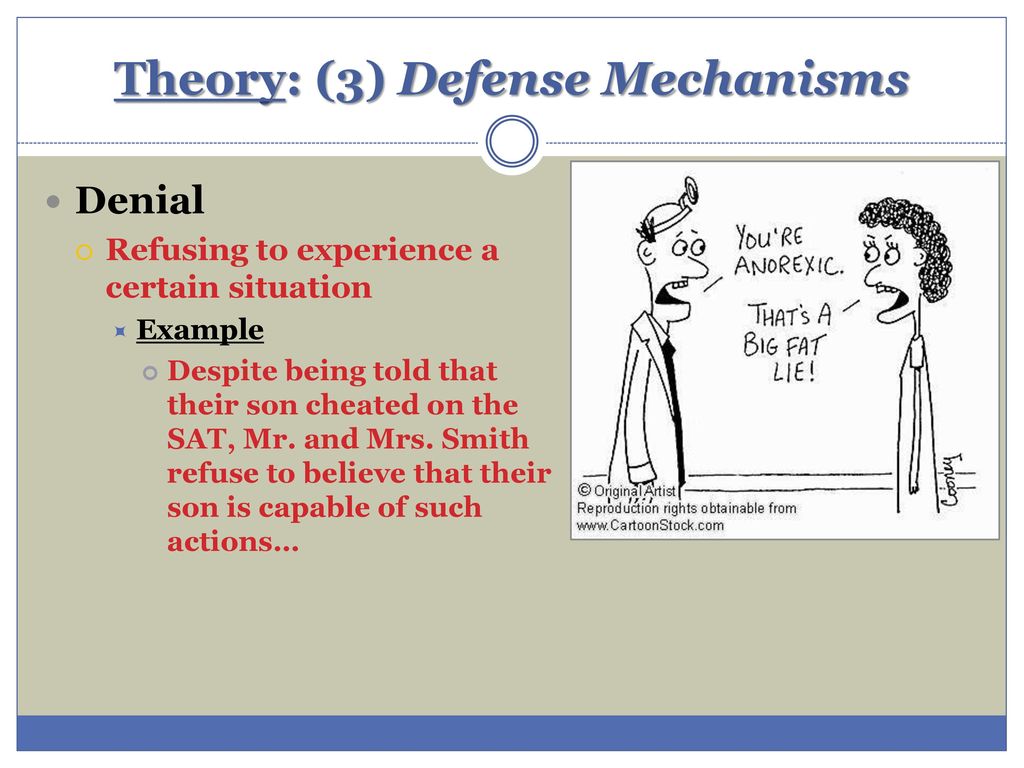

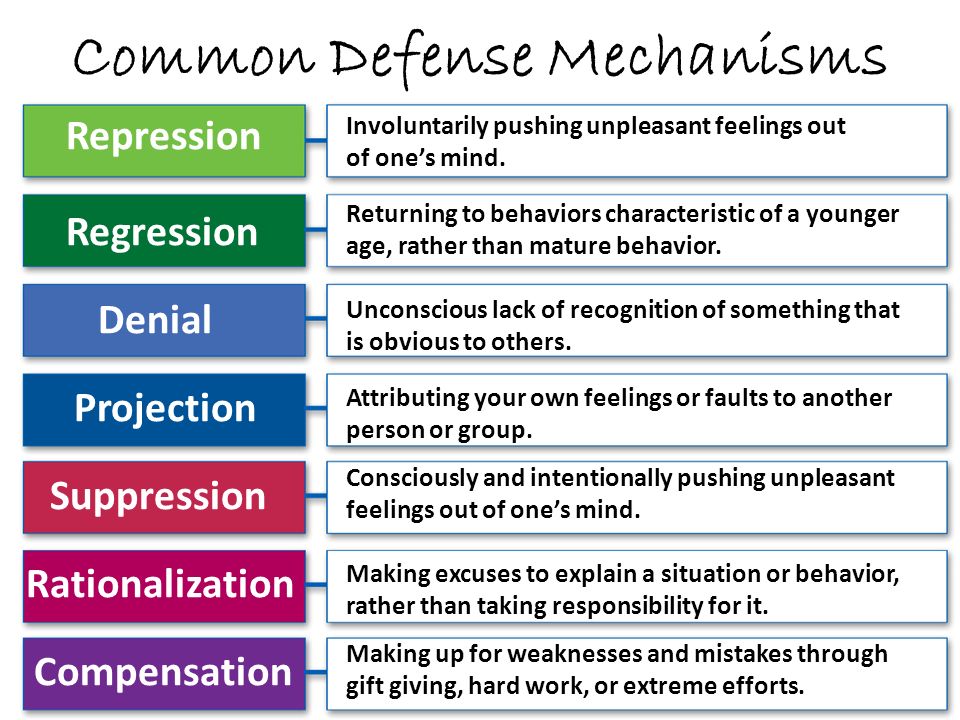

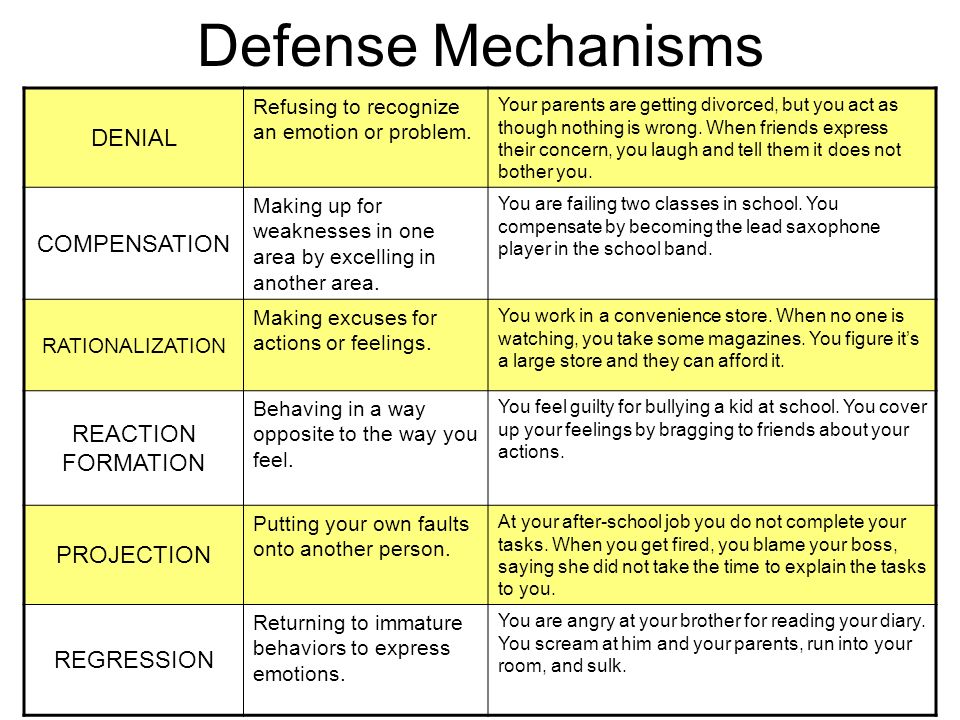

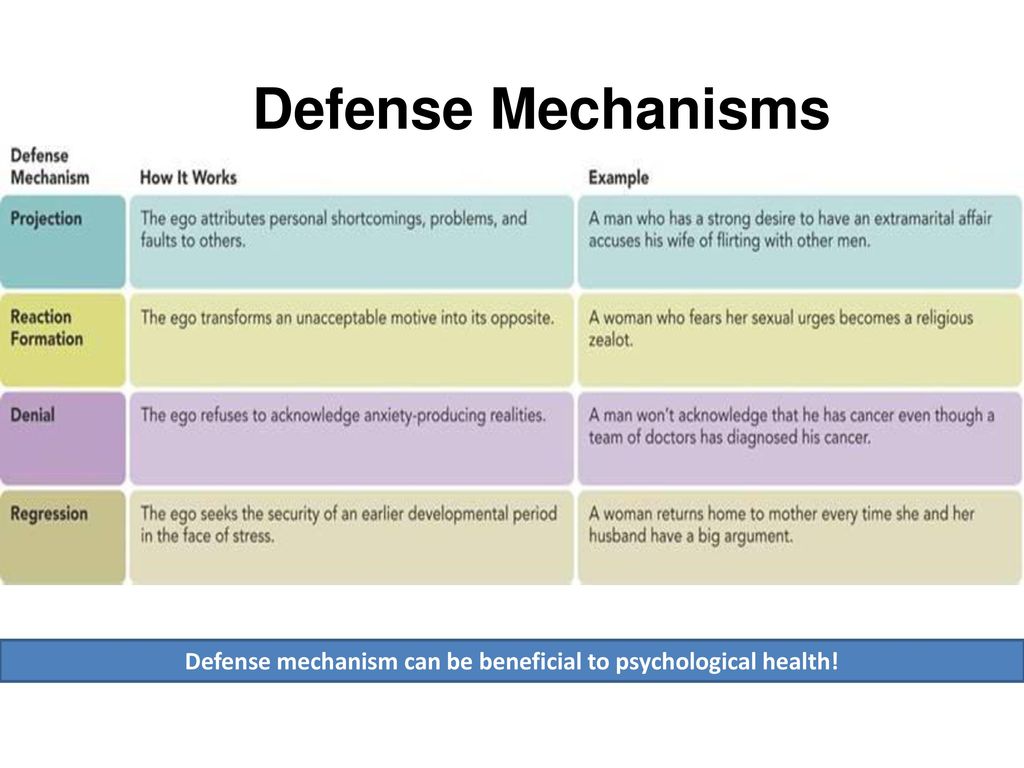

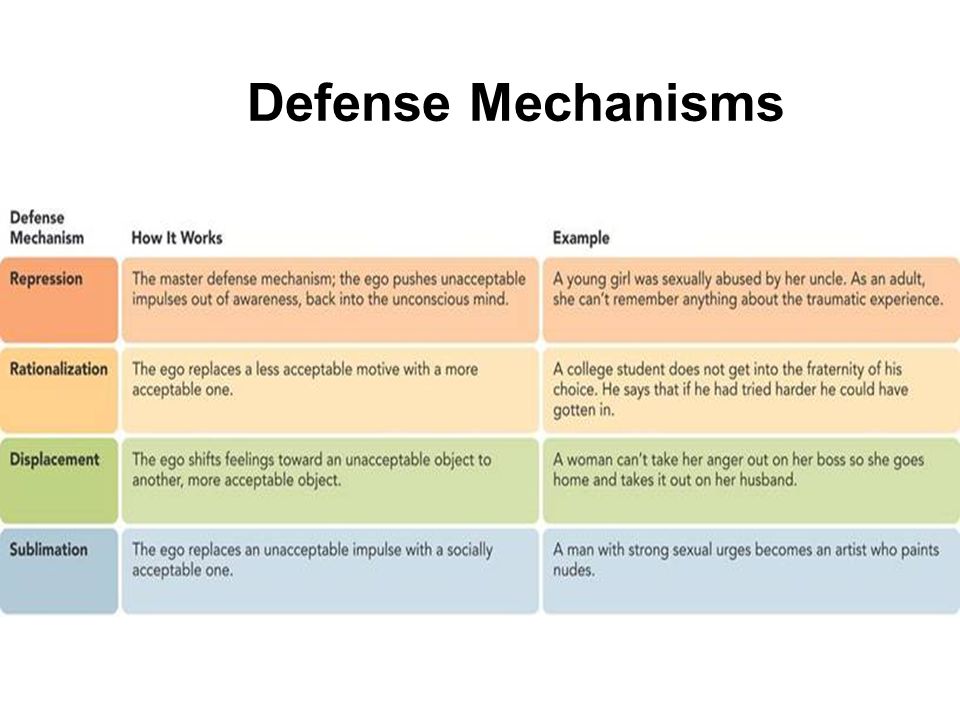

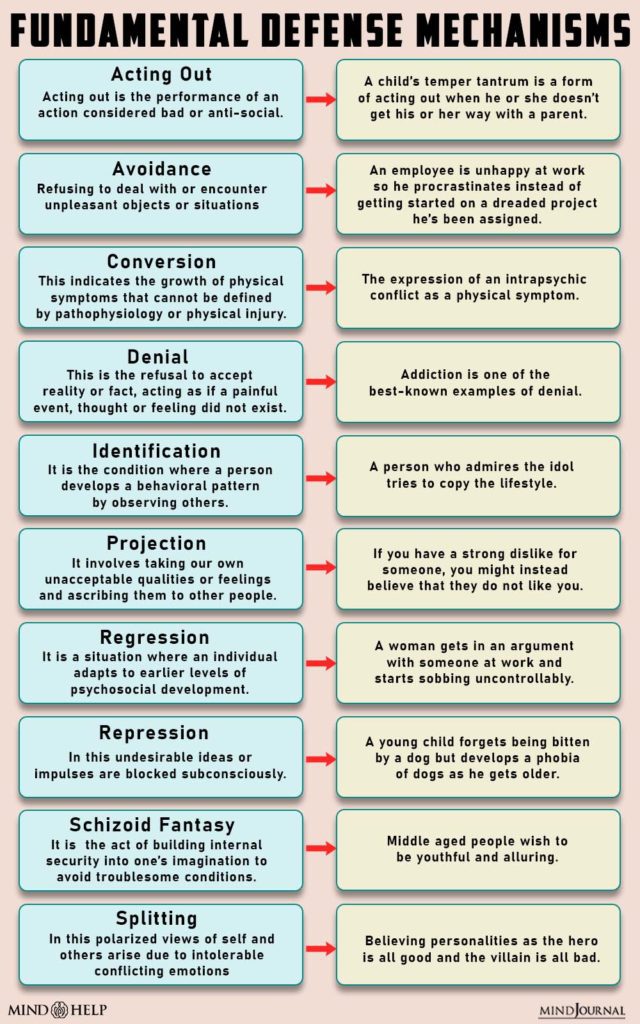

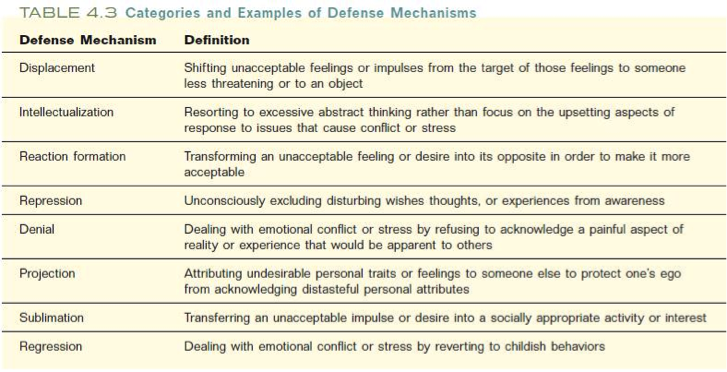

A large number of classification options for defense mechanisms have been proposed: for example, in the book by N. McWilliams, they are all divided into two levels according to the degree of primitiveness, depending on how much their use prevents the individual from objectively perceiving what is happening around. Reality denial, rationalization, repression, projection, reactive formation, substitution, regression, and compensation, which will be the subject of this article, are the most studied defense mechanisms.

Reality denial, rationalization, repression, projection, reactive formation, substitution, regression, and compensation, which will be the subject of this article, are the most studied defense mechanisms.

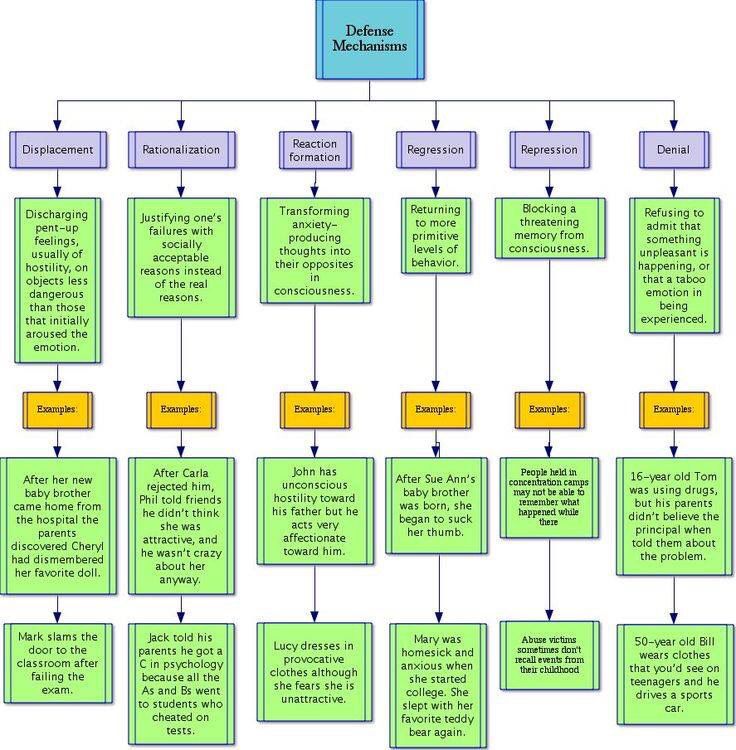

Ways of action of protective mechanisms:

- unwanted information is ignored (not perceived) - denial, avoidance;

- unwanted information is forgotten, having already been perceived - repression;

- undesirable information admitted to the memorization system is interpreted in a way convenient for a person - sexualization, rationalization.

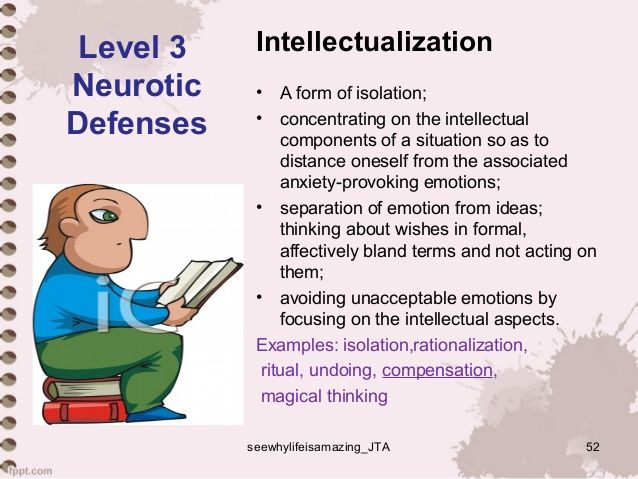

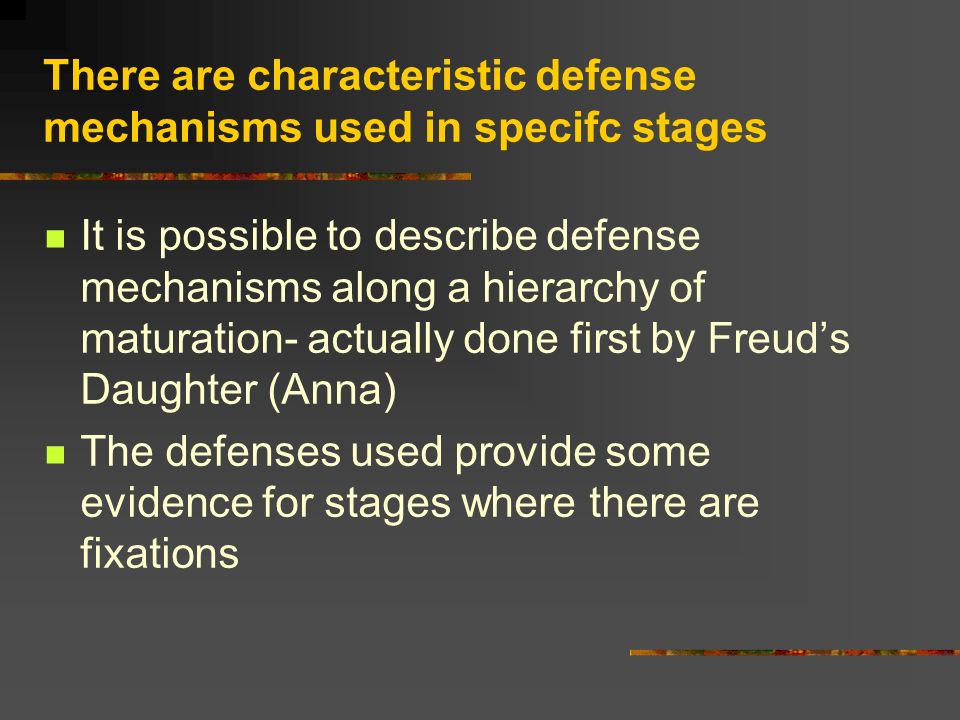

Anna Freud created one of the classifications of psychological defenses; perceptual, intellectual and motor automatisms were singled out. She also most fully worked out the question of the sequence of maturation of defense mechanisms. So, according to the researcher, the age of up to a year is the stage of pre-protection, two-year-old children overcome dangers through denial (in the form of refusal or opposition), as well as through imitation and projection: the child separates himself from the world around him, attributing to the environment everything that is painful for himself and accepting everything is subjectively pleasant. At primary school age, in connection with the development of logical thinking, compensation develops as an immature form of rationalization.

At primary school age, in connection with the development of logical thinking, compensation develops as an immature form of rationalization.

Compensation mechanism

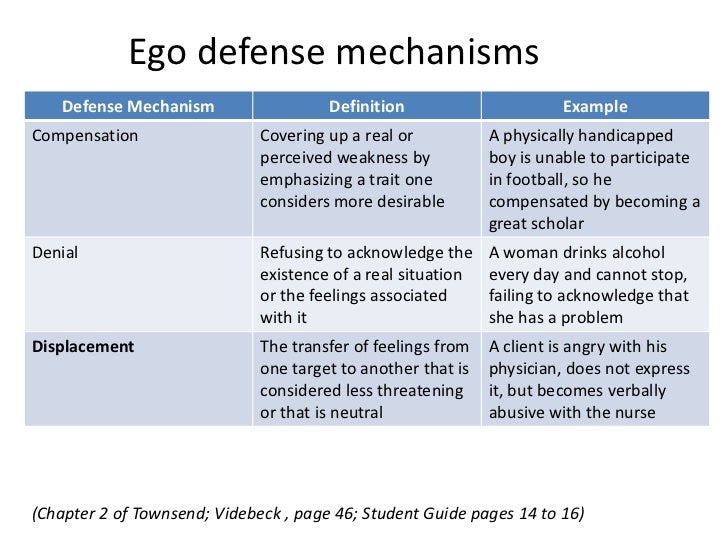

Compensation is considered ontogenetically the latest and most intellectually complex phenomenon among the defense mechanisms of the psyche; it is an attempt by an individual to correct, somehow make up for his personal or physical shortcomings, both real and imaginary. The disproportion of the applied efforts in relation to the existing inferiority, the greater intensity of attempts to overcome it may indicate the presence of the problem of overcompensation, which will be discussed below.

There is socially acceptable compensation that contributes to personal self-improvement and the development of one or more areas of human activity (a disabled girl develops intellectually, masters painting skills and subsequently becomes a famous artist), and, on the contrary, asocial compensation, the consequence of which may be the social maladjustment of an individual (a person compensates for low growth and lack of physical development with excessive lust for power, aggressiveness towards others).

Depending on the area of implementation of the compensatory mechanism, there are:

- Direct compensation: a person seeks to eradicate a real or imagined disadvantage by improving in the area where there is (objectively or subjectively) inferiority;

- Indirect compensation, which can be described as the desire of an individual to compensate for inferiority in one area with success in another.

Compensation can often be intertwined with the identification mechanism: an individual tries to overcome his real or imaginary shortcomings with the help of fantasy, by appropriating the merits or behavioral characteristics of another individual. Such compensation can no longer be called a defense mechanism inherent in a mature personality.

Observations show that people who prefer compensation to other defense mechanisms often turn out to be dreamers who tend to look for an ideal in various spheres of life.

Hypercompensation

In psychology, it is customary to distinguish a special type of compensatory behavior - hypercompensation. The term was first used by Alfred Adler. Unlike ordinary compensation, hypercompensation allows not only to get rid of the feeling of one's own inferiority (real or imagined), but also to take a dominant position among others by achieving a significant result in any area of human activity. Thus, the hallmark and main driving force of overcompensation is the desire for superiority. Despite the fact that sometimes it is overcompensation that “creates” geniuses, the phenomenon also has a negative side.

The term was first used by Alfred Adler. Unlike ordinary compensation, hypercompensation allows not only to get rid of the feeling of one's own inferiority (real or imagined), but also to take a dominant position among others by achieving a significant result in any area of human activity. Thus, the hallmark and main driving force of overcompensation is the desire for superiority. Despite the fact that sometimes it is overcompensation that “creates” geniuses, the phenomenon also has a negative side.

Note 2

An extremely small percentage of people who are subject to this psychological defense mechanism achieve tremendous success.

The majority of people sometimes remain in a neurotic state of pursuit of their own superiority for the rest of their lives; a person is faced with the unrealizability of his claims, a state of frustration arises, a lot of intrapersonal conflicts are formed, which by no means contributes to healthy relationships with others and the preservation of the psycho-emotional balance of the individual. There may be a number of undesirable consequences: the isolation of the individual in the group, the destruction of interpersonal relationships, deviant behavior and inadequate response to criticism. A way to weaken the negative impact of the mechanism of hypercompensation can be the realization by the individual of the fact that his behavior is guided by a deep inferiority complex.

There may be a number of undesirable consequences: the isolation of the individual in the group, the destruction of interpersonal relationships, deviant behavior and inadequate response to criticism. A way to weaken the negative impact of the mechanism of hypercompensation can be the realization by the individual of the fact that his behavior is guided by a deep inferiority complex.

what it is, types of psychological defense mechanisms in a problem situation, examples of compensatory behavior from life - nenumerolog

Compensation in psychology is a set of peculiar defense mechanisms that allow a person to replace shortcomings (and the feeling of inferiority caused by them) with something else. Moreover, literally everything can act as such flaws that need to be "compensated" - from short stature and scars to violations in the work of internal organs and imaginary diseases. Some people manage to come to terms with their problems - they live in peace and harmony, not striving for any significant changes and demonstrations of their own significance. Another category of people, on the contrary, wants to rise in the eyes of others, thereby only aggravating the situation.

Another category of people, on the contrary, wants to rise in the eyes of others, thereby only aggravating the situation.

What are compensatory mechanisms

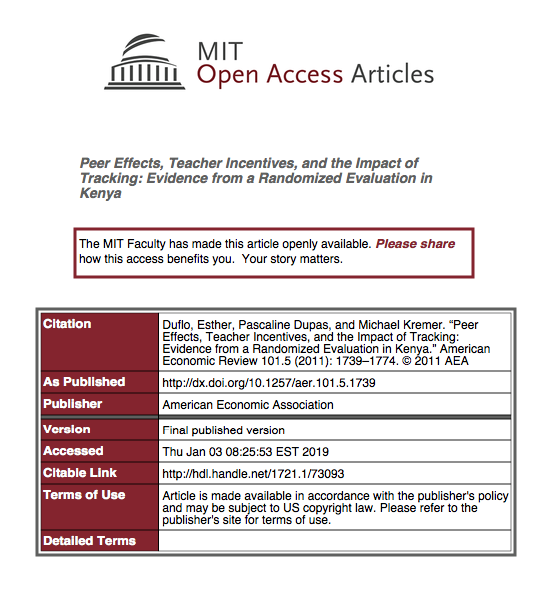

The first works on the study of traditional psychological compensation appeared in 1984. It was then that Sigmund Freud wrote and published a book called Defensive Neuropsychoses. Subsequently, his undertakings were continued by Alfred Adler, who developed the theses of scientific work into a real psychoanalytic discipline. True, both scientists often disagreed with the opponent’s positions, but, as you know, truth is born in a dispute. Thanks to their research, the scientific community was able to form the first more or less accurate definition of the classical compensatory mechanism.

So today, compensation is called a process activated by feelings of inferiority. The easiest way to explain the essence of this term is through a banal example. Short, powerful men tend to buy a huge car or start a relationship with a tall girl. In the framework of the presented situation, we are talking about traditional compensators - a disadvantage (often noticeable only to its owner) acts as a motivator. The procedure for compensating for various imaginary or real flaws is not in itself something bad. Often it becomes an additional incentive to achieve certain success.

In the framework of the presented situation, we are talking about traditional compensators - a disadvantage (often noticeable only to its owner) acts as a motivator. The procedure for compensating for various imaginary or real flaws is not in itself something bad. Often it becomes an additional incentive to achieve certain success.

Types of compensatory mechanisms

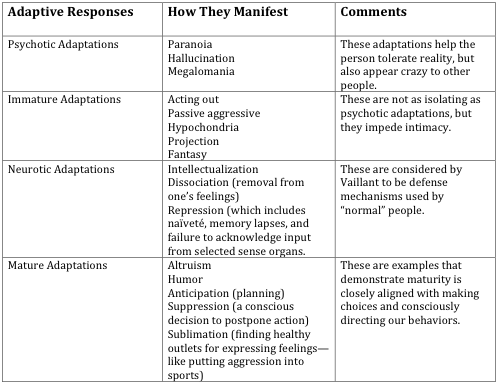

Mental compensation in psychology is a separate discipline, which is the subject of many scientific works. According to Alfred Adler, all compensatory effects should be divided into three groups:

- Physiological - replacement of missing limbs, vision or hearing problems.

- Socio-cultural - an attempt to get rid of age, gender, political and economic differences.

- Primordial - the biological desire of mankind for development and constant progress.

However, the qualification proposed by the Austrian psychologist was not accepted by the authoritative scientific community. It showed certain shortcomings, such as the idea that the desire for compensation deprives people of happiness. That is why experts chose to develop a new way of fractionating compensatory mechanisms, based solely on the results of long-term studies.

It showed certain shortcomings, such as the idea that the desire for compensation deprives people of happiness. That is why experts chose to develop a new way of fractionating compensatory mechanisms, based solely on the results of long-term studies.

Real compensation

This concept is commonly used to denote a person's ability to adapt to new conditions. This applies to people who previously considered themselves inferior, but then managed to cope with shortcomings, and now lead a normal, calm life. With the help of the works of Alfred Adler, psychoanalysts were able to identify a set of situations that contribute to the activation of such an extremely peculiar stimulus:

- Desire to achieve real excellence, to succeed in something.

- Striving for political, economic or physical power.

- The need for great perseverance and great willpower.

- Interest in events taking place in the surrounding world.

It is not difficult to guess that compensatory behavior and the mechanism of compensation are aspects that are present in almost all people. They help to achieve certain results, even in spite of their own imaginary or real failure.

They help to achieve certain results, even in spite of their own imaginary or real failure.

Overcompensation

This is one hundred percent correct designation of a situation in which a person pays increased attention to the abilities of an undeveloped, weak or missing part of his own body. The definition also refers to any organs and skills that can be qualitatively changed through training. The easiest examples of such a psychological pathology include:

- Workaholism - focusing on work and professional activities, the desire to build the best possible career.

- Constant and obsessive talkativeness is an attempt to rid oneself of embarrassment, embarrassment and other similar feelings.

- Sexual promiscuity - fear of adults, serious and truly long-term relationships.

- Obsessive attempts to become stronger, observed in individuals with initially little physical ability.

- Inappropriate behavior exhibited by individuals suffering from insecurity and so on.

According to definitions and examples from life, compensation in psychology is a positive force in its own way, which, however, is not comparable with a normal measure. Hypercompensation is an extreme degree of exaggeration of one or another quality developed by a person through conscious or unconscious actions. Often the presence of the considered pathological tendencies plays into the hands, but more often the presence of the mechanism only harms a normal, happy life. The fight against an inferiority complex is, of course, a just thing, but its implementation should be carried out only with the support of a qualified specialist.

Pseudo-compensation

This term is used to denote situations in which people do not really seek to get rid of any flaws, but simply manipulate other personalities. There may be several reasons for such behavior:

- Real physical disabilities that have a bad effect on health, as well as provoking systematic nervous breakdowns.

- Overprotection and excessive care are things that are the main factors in the development of selfishness, capriciousness and intolerance.

- Lack of love and attention, a small amount of communication with relatives and friends, lack of opportunity for a banal frank conversation.

The movement of compensation along an erroneous path in psychology is a whole list of very different symptoms that are exclusively negative in color and character. As mentioned earlier, persons subject to pseudo-compensation do not seek to level their own shortcomings, but simply turn them into an excuse for manipulation. Complete withdrawal into the disease, obsession with one's weaknesses, unreasonable laziness, constant self-promotion, regular demonstration of superiority - this is a list of the main points that characterize the issues under consideration. It will be possible to get rid of such conditions only with the help of an experienced, qualified psychologist.

What is the name of the type of psychological defense mechanism: the principle of compensation

It is easy to guess that the main, central purpose of compensatory is to protect the psyche of a particular individual from the influence exerted by negative emotions. The processes associated with the functioning of such a system, as in many other situations, begin to manifest themselves from childhood.

The processes associated with the functioning of such a system, as in many other situations, begin to manifest themselves from childhood.

From an early age, people understand exactly how they should behave in order to receive approval from the surrounding society. Parents who are illiterate in matters of upbringing can inspire their kids, for example, with the fact that love and adoration can be achieved only by earning a lot of money. A child who has received an appropriate attitude will transfer it into his adult, active life, putting the amount of income at the forefront of any activity.

It is worth pointing out that the classic compensation is a kind of escape from various troubles. Making up for his own shortcomings (imaginary or real), the individual moves away from real life, instead of understanding why the current circumstances drive him into depression and despondency.

The essence of compensatory behavior in management

So, psychological compensation is a defense mechanism of psychology, which has a dual character. In certain situations, he plays into the hands of people, allowing them to achieve incredible success, regardless of the field of activity. However, most often compensation interferes with normal personal growth, becomes a fixed idea, literally haunting. A user who wants to direct the process of filling deficiencies in a competent direction should be guided by the following rules:

In certain situations, he plays into the hands of people, allowing them to achieve incredible success, regardless of the field of activity. However, most often compensation interferes with normal personal growth, becomes a fixed idea, literally haunting. A user who wants to direct the process of filling deficiencies in a competent direction should be guided by the following rules:

- Don't be afraid to do wrong.

- It is worth counting on yourself and relying on the forces present.

- Be honest in all circumstances.

- Listen to the mind and thoughts.

- Remain absolutely calm and demonstrate peace.

- Don't focus on the faults of others.

- Frame success as a working strategy.

About how exactly all of the listed standards level compensators, say, for example, experts from the nenumerolog.ru platform.

The law of compensation and the psyche

It is easy to guess that the majority of people who feel some kind of inferiority seek to get rid of it by developing certain skills, abilities and skills. Then the hypercompensation mechanism comes into play, accompanied by excessive fixation and dysfunction. Similarly, an overweight person begins going to the gym and jogging, completely ignoring healthy sleep and banal walks in the fresh air. His state of health is gradually deteriorating, and mental deviations continue their progressive growth. Often, the impossibility of quickly removing a certain flaw leads to conflict states: hard drinking, fanaticism, shifting responsibility, and so on.

Then the hypercompensation mechanism comes into play, accompanied by excessive fixation and dysfunction. Similarly, an overweight person begins going to the gym and jogging, completely ignoring healthy sleep and banal walks in the fresh air. His state of health is gradually deteriorating, and mental deviations continue their progressive growth. Often, the impossibility of quickly removing a certain flaw leads to conflict states: hard drinking, fanaticism, shifting responsibility, and so on.

Compensation for deviations as a process

As mentioned earlier, the work of the compensatory mechanism is not always harmful - it can be controlled, however, only by drawing up a competent program with the help of a qualified psychologist. The entire operation to transform destructive energy into positive energy proceeds through several key phases:

- inspection of the body in order to search for various violations;

- evaluation of the parameters of the problem;

- localization and determination of the severity of pathology;

- formation of an algorithm for mobilizing the patient's nervous and psycho-emotional resources;

- implementation of instructions with tracking of all implemented steps;

- consolidation of results.

Determining the types of psychological protection and compensation in psychology is a rather difficult range of cases that requires the most competent approach. It is worth understanding that different therapy is used for adults and children. People who have reached the age of majority have a complex functionality of the central nervous system, with interchangeable blocks. An abnormal child will have to cope with the procedure for creating new functions and systems.

Correction

Modern compensatory includes a lot of scientific works devoted to correctional activities within the profile area. The founder of many methods was L. S. Vygotsky, a Soviet psychoanalyst who published an incredible number of entertaining and extremely valuable manuals. It was he who managed to highlight the main points regarding the interaction of reparative and corrective processes:

- Creation of active and effective forms of children's experience by involving them in all kinds of social activities.

- Proportionate use of medical and pedagogical influence to remove various aspects of primary and secondary deviations.

- Inclusion of adult patients in active work and professional life, with appropriate interpersonal communications.

- Determination of the level of intervention required by assessing the character traits and the degree of defect.

It is easy to guess that only an experienced and qualified psychologist will be able to cope with such a complex of measures.

Compensators and examples of compensation in psychology

Vivid models of compensatory behavior are:

- The body's desire to receive some useful substances while a person is on a diet. The body signals a lack of tryptophan and magnesium by signaling the need for ice cream. Similarly, things are, say, with magnesium deficiency, which causes persistent interest in chocolate.

- The need to obtain successful results in any business. A physically weak teenager can really play chess very well.

Moreover, he will achieve due success in the field of a classical grandmaster, but his “strength” shortcomings will still be a source of irritation.

Moreover, he will achieve due success in the field of a classical grandmaster, but his “strength” shortcomings will still be a source of irritation. - Permanent fixation, e.g. in a quarry. Desperate workaholism, which has replaced family, relatives and friends, also indicates that the individual wants to get a certain position in society, hiding his imaginary or real flaws.

All of the listed cases need competent study together with an experienced and qualified psychologist.

Spheres of influence on inevitable processes

Quite often, compensators appear due to a kind of social impact. People who have received any comments or heard negative statements addressed to them, as a rule, close themselves off from such negativity. However, regular repetition of offensive phrases can have a powerful opposite effect. It manifests itself especially strongly if a close friend, relative or senior comrade with unquestioned authority becomes the source of the words.