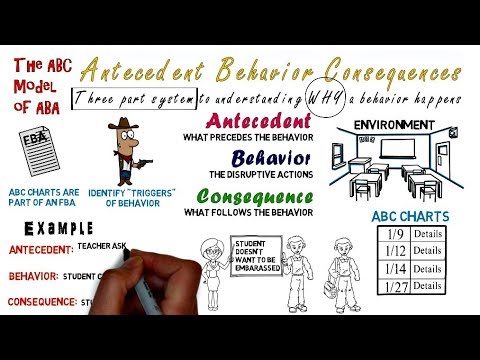

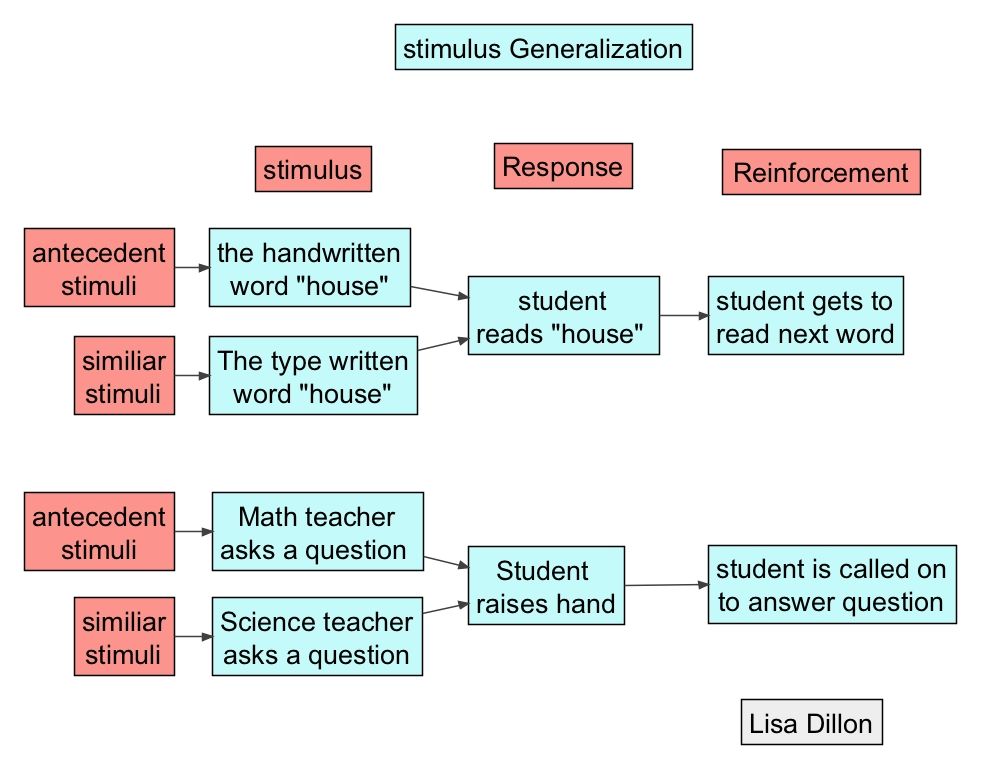

Examples of antecedents in behavior

Basic Behavior Components - Project IDEAL

What is Behavior?

- Behavior serves two purposes: (1) to get something or (2) to avoid something.

- All behavior is learned.

- Behavior is an action that is observable and measurable.

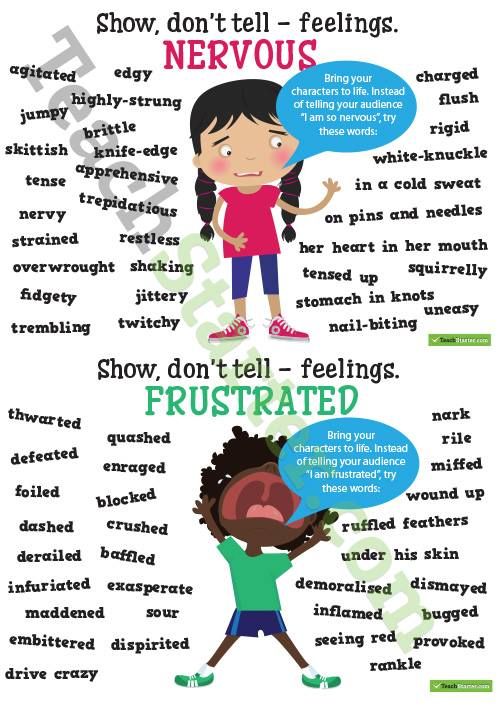

- Behavior is observable. It is what we see or hear, such as a student sitting down, standing up, speaking, whispering, yelling, or writing. Behavior is not what a student is feeling, but rather how the student expresses the feeling. For example, a student may show anger by making a face, yelling, crossing his arms, and turning away from the teacher. These observable actions are more descriptive than just stating that the student looks anxious.

- Behavior is measurable. This means that the teacher can define and describe the behavior. The teacher can easily spot the behavior when it occurs, including when the behavior begins, ends, and how often it occurs. For example, “interrupting the teacher all the time” is not measurable because it is not specific.

However, “yelling ‘Hey, teacher!’ 2-3 times each math period” is specific and measurable. Given the definition, even an outside observer would know exactly which behavior the teacher wants to change.

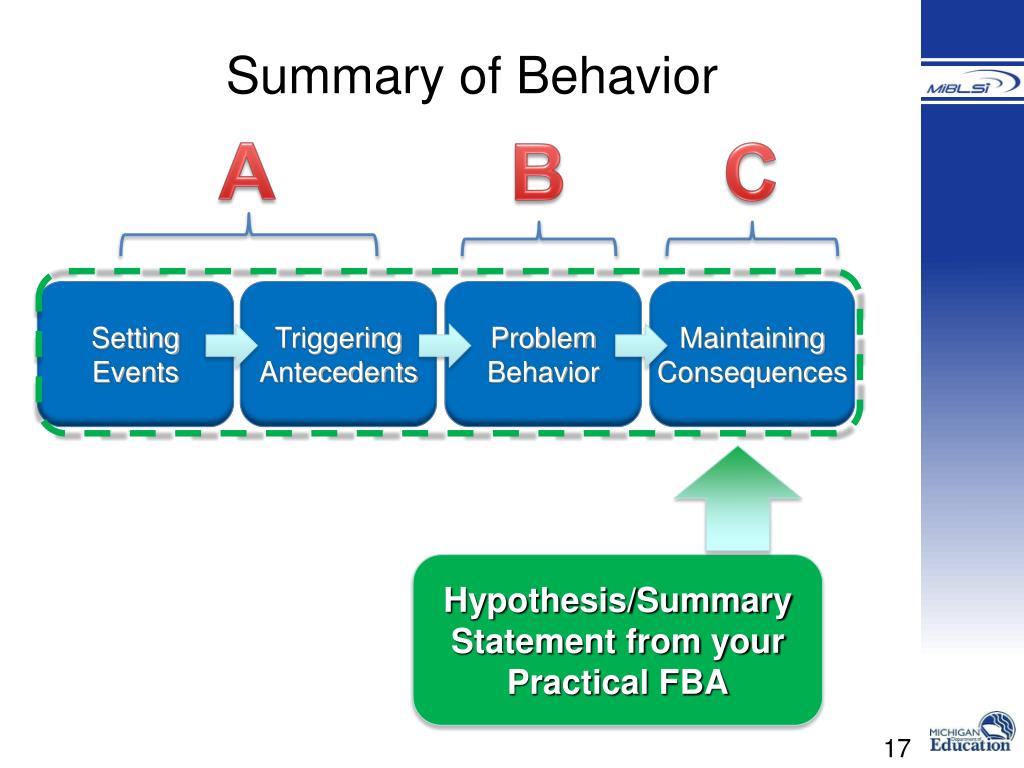

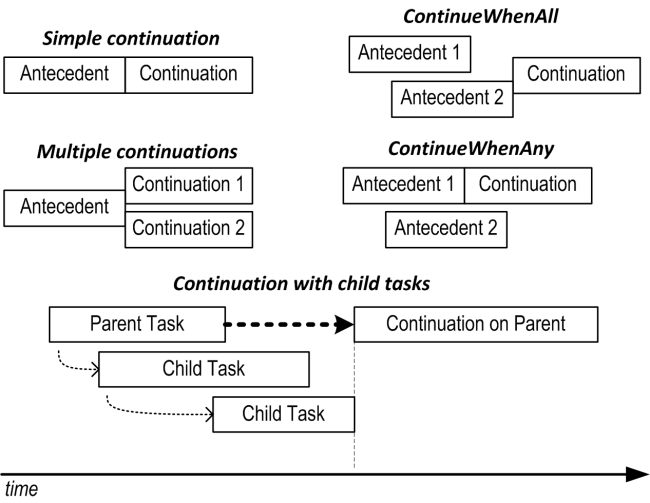

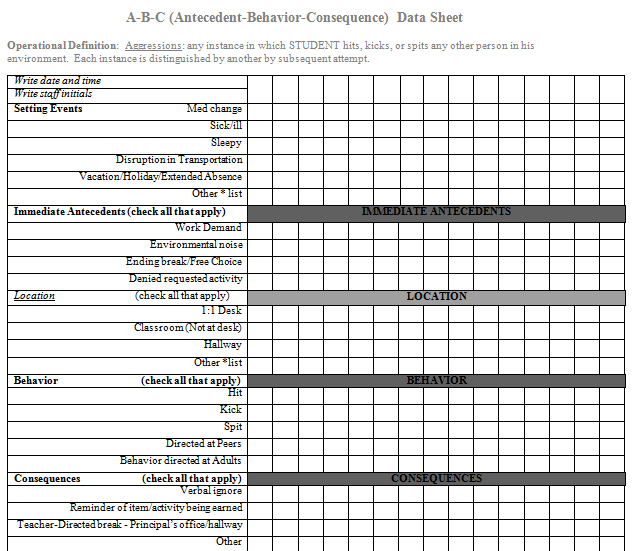

- Behavior has three components:

A (Antecedents) ⇒ B (Behaviors) ⇒ C (Consequences).

Rather than occurring in isolation, behavior is preceded by an antecedent (trigger) that sets off the behavior and is followed by a consequence, or a reaction to the behavior. This process is easily remembered by the acronym ABC.

Antecedents (A):

Antecedents are events or environments that trigger behavior. They can happen immediately before a behavior or be an accumulation of previous events. Examples of immediate antecedent would be: A student walks into class crying because someone called her a name as she was walking down the hall. The antecedent was the name calling in the hallway.

Antecedent can also be a collection of events that have happened in the past that eventually explode into acting out behaviors. For example: A student is constantly bullied and teased by other students on the bus and after two weeks of this, one day the student stands up on the bus and begins fighting with the other students sitting around him. The ongoing bullying and teasing has finally accumulated and resulted in explosive and aggressive behavior by the young man being taunted.

For example: A student is constantly bullied and teased by other students on the bus and after two weeks of this, one day the student stands up on the bus and begins fighting with the other students sitting around him. The ongoing bullying and teasing has finally accumulated and resulted in explosive and aggressive behavior by the young man being taunted.

Behavior can also be enhanced or impacted by setting events such as a lack of sleep, medication, hunger/thirst, etc. For example, the student who is on medication may be drowsy or sleepy in class and unable to perform tasks required by the teacher.

Behaviors (B):

Behavior, as noted above, is an action that is both observable and measurable. It should be described in a way that an outside observer can easily identify the action (behavior) in question.

Examples

Vague behavior: Sandy is being obnoxious during her science lab class.

- What does obnoxious look like?

- Describe an example of a more specific way to identify obnoxious behavior (i.

e., hitting other students, talking out in class, texting on her cell phone).

e., hitting other students, talking out in class, texting on her cell phone). - All behaviors need to be observable (e.g., hitting, talking out, texting).

- All behaviors need to be measurable (how many times, how often, length of time).

An observable and measurable behavior: Sandy hits her lab partner whenever he tries to work on his science lab report.

- The behavior is hitting when the lab partner works on his science paperwork. See the difference?

Consequences (C):

A consequence is the response to the student’s behavior. Consequences are how people in the environment react to the behavior. When a student displays a certain kind of behavior, the teacher may “warn” or “ignore” the student. Warning, ignoring and reinforcing are some examples of consequences.

Here are some examples of the behavior chain (A⇒B⇒C):

Example 1

- Antecedent: Teacher asks question.

- Behavior: Student shouts out an answer without raising her hand.

- Consequence: Teacher verbally reprimands student.

Example 2

- Antecedent: Driver sees a stop sign.

- Behavior: Driver stops the car at the intersection.

- Consequence: Driver avoids a possible wreck and ticket.

Example 3

- Antecedent: Mother asks child to pick up toys and put in toy box.

- Behavior: Child picks ups toys and puts them into the toy box.

- Consequence: Mother verbally praises child and gives him a cookie.

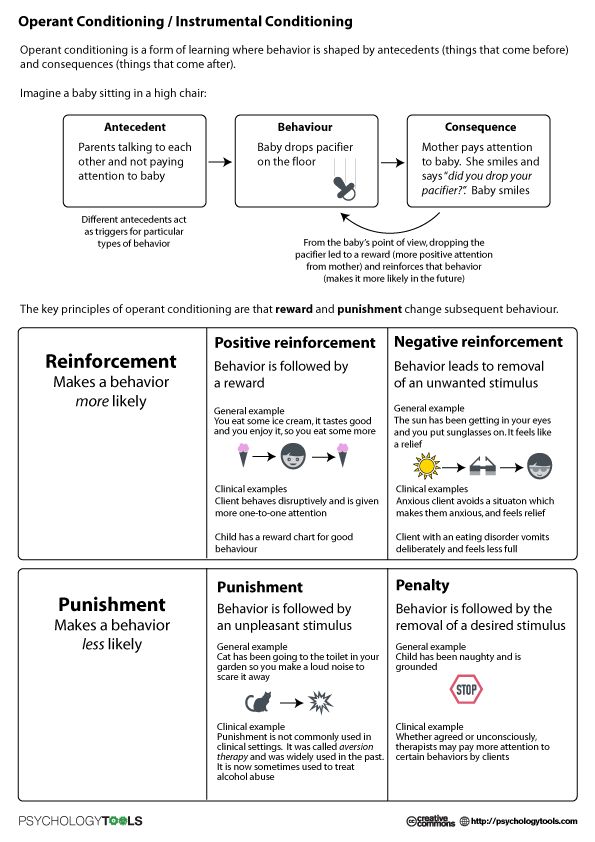

Further Understanding of Consequences: Reinforcement and Punishment

Consequences for behavior can impact the future of the behavior (i.e., increase or decrease the behavior). Pleasant consequences that increase the occurrence of future behavior are called reinforcements. Undesirable consequences that decrease the occurrence of future behavior are called punishments.

Reinforcement

Reinforcement is any type of feedback or consequence that increases future occurrences of a behavior. An increase in the student’s behavior results from a reinforcement even if the teacher does not find the consequence or feedback reinforcing. In other words, a consequence is reinforcing based on an individual student’s response. What is reinforcing to one student may not be to another; therefore planning for behavior change must be individualized.

An increase in the student’s behavior results from a reinforcement even if the teacher does not find the consequence or feedback reinforcing. In other words, a consequence is reinforcing based on an individual student’s response. What is reinforcing to one student may not be to another; therefore planning for behavior change must be individualized.

Positive reinforcement is when something is gained and it increases the occurrence of a behavior. An example would be if a student makes a 100 on a trial spelling test on Thursday, she would get free time. The student performs well on the future tests too. The student’s study behavior for their spelling test has increased due to earning free time on Fridays, which is the positive reinforcer.

Negative reinforcement is when something is taken away and it increases the occurrence of a behavior. An example would be if a student does not finish his homework, his parents tell him that he does not get to watch TV that night at home. The next time the student has homework, he finishes as soon as he can so that he will not miss out on his TV time at home. His homework completion is the behavior that has been reinforced with the loss of TV privileges as the negative reinforcer.

The next time the student has homework, he finishes as soon as he can so that he will not miss out on his TV time at home. His homework completion is the behavior that has been reinforced with the loss of TV privileges as the negative reinforcer.

Reinforcement Example 1

- Antecedent: Teacher says "Walk and talk quietly through the library.”

- Behavior: Students walk quietly, but talk loudly to their friends through the library.

- Consequence: Teacher says "Because the class did not follow directions about walking and talking quietly through the library, we will miss recess today.”

- Future Behavior: Students remember to walk and talk quietly through the library in order to have recess. (Removal of recess is the negative reinforcer.)

Reinforcement Example 2

- Antecedent: Student needs to use the restroom

- Behavior: Student asks politely for restroom pass

- Consequence: Student receives the restroom pass from the teacher

- Future Behavior: Student remembers to ask politely for the pass in the future.

(Gaining permission to take the hall pass and use the restroom is the positive reinforcer for asking politely to use the restroom.)

(Gaining permission to take the hall pass and use the restroom is the positive reinforcer for asking politely to use the restroom.)

Reinforcement Example 3

- Antecedent: Teacher instructs class during math class.

- Behavior: Student yells out without permission.

- Consequence: Student is reprimanded by the teacher as the class laughs (gains attention).

- Future Behavior: Students yells more. (Gaining attention from other students in the class is the positive reinforcer for yelling out in class.)

Punishment:

Punishment is a type of consequence that decreases future occurrences of the behavior. If the student finds the consequence unpleasant or undesirable and decreases the occurrence of the behavior in the future, then it is punishment, even if the teacher or other students do not perceive the consequence as unpleasant.

Punishment Example 1

- Antecedent: Teacher says "Walk in the hall.

"

" - Behavior: Student runs in the hall.

- Consequence: Student is reprimanded by the teacher.

- Future Behavior: Student does not run down the hall. (The punishment is being reprimanded and it decreases the running in the hall behavior.)

Punishment Example 2

- Antecedent: Homework is due as class begins.

- Behavior: Student forgets to turn in his homework.

- Consequence: Student loses points on his homework grade.

- Future Behavior: Student turns future homework in on time. (The punishment is loss of points, and it decreases the student forgetting to turn his homework in on time.)

Punishment Example 3

- Antecedent: Teachers states it is time for silent reading.

- Behavior: Students continue to talk.

- Consequence: Class loses free time for drawing in the afternoon.

- Future Behavior: Class reads silently when requested in the future.

(The punishment is loss of free time for drawing and the class stops talking during silent reading time.)

(The punishment is loss of free time for drawing and the class stops talking during silent reading time.)

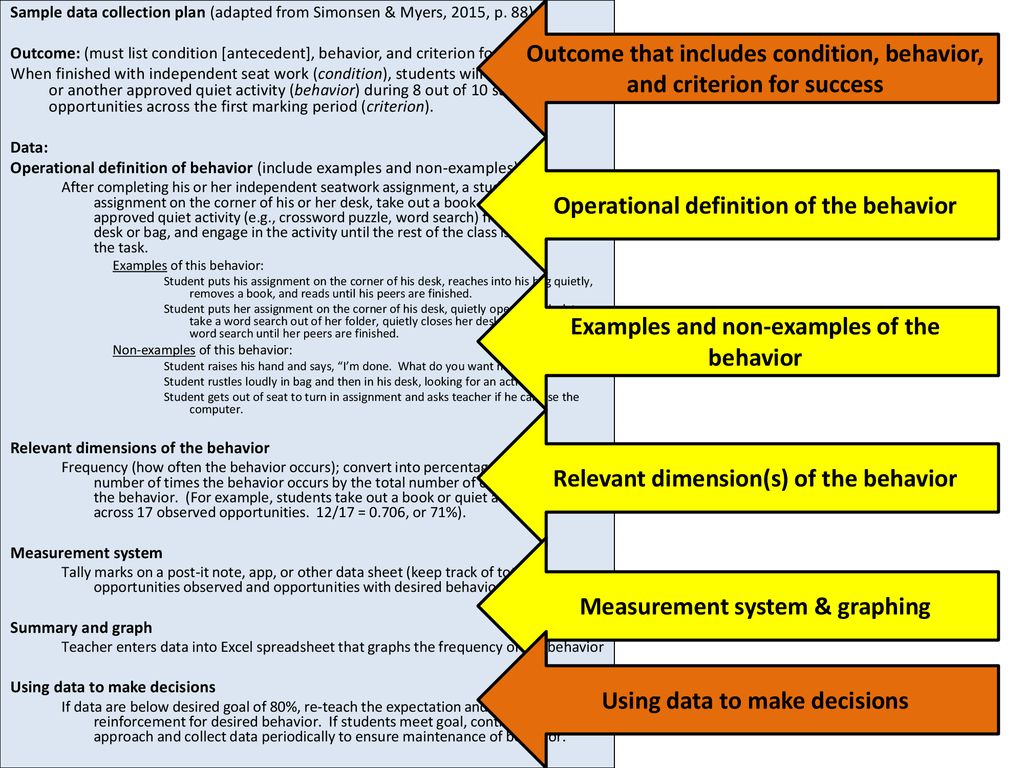

Data Collection with Behavior Change:

It is possible to inadvertently reinforce or punish behavior when trying to do the opposite. Therefore, data collection is a critical component whenever you are trying to change behavior. Data enables you to objectively analyze what is happening and modify the intervention if necessary.

Here is an example of inadvertently reinforcing an inappropriate behavior.

- Antecedent: Teacher asks the student to do a task

- Behavior: Student yells “NO!”

- Consequence: Student is sent to time out and avoids the task

- Inadvertent Reinforcement: Student prefers sitting quietly over working so the student yells out more to avoid tasks.

Here is an example of inadvertently punishing a desired behavior.

- Antecedent: Teacher asks for a student to do a task

- Behavior: Student volunteers and performs the task

- Consequence: Teacher calls the student to the front of the room to praise the student.

- Inadvertent Punishment: Student is embarrassed and does not volunteer again.

Resources

Activities

The ABCs of Behavior Behavior is Observable and Measurable Reinforcement and Punishment Data Collection with Behavior ChangePresentations

Basic Behavior Components Basic Behavior Components TranscriptCase Studies

Olga JeffreyTests

Basic Behavior Components Test Basic Behavior Components Test KeyConversations

To access this section, please sign in to your account. If you don't have an account yet, sign up now. It's free!

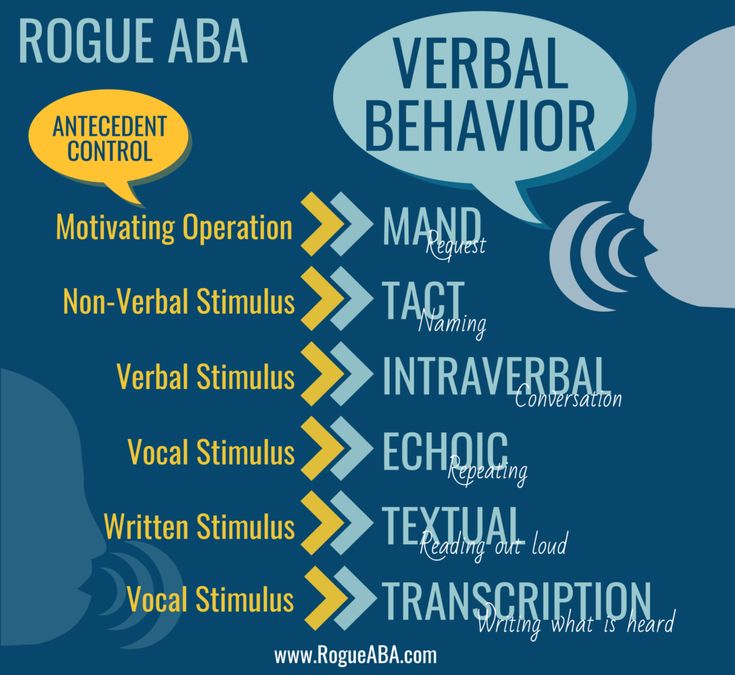

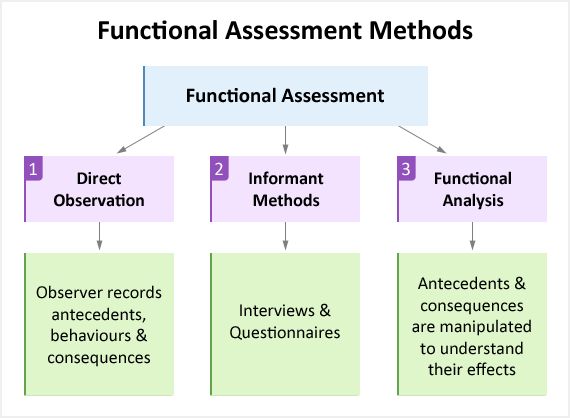

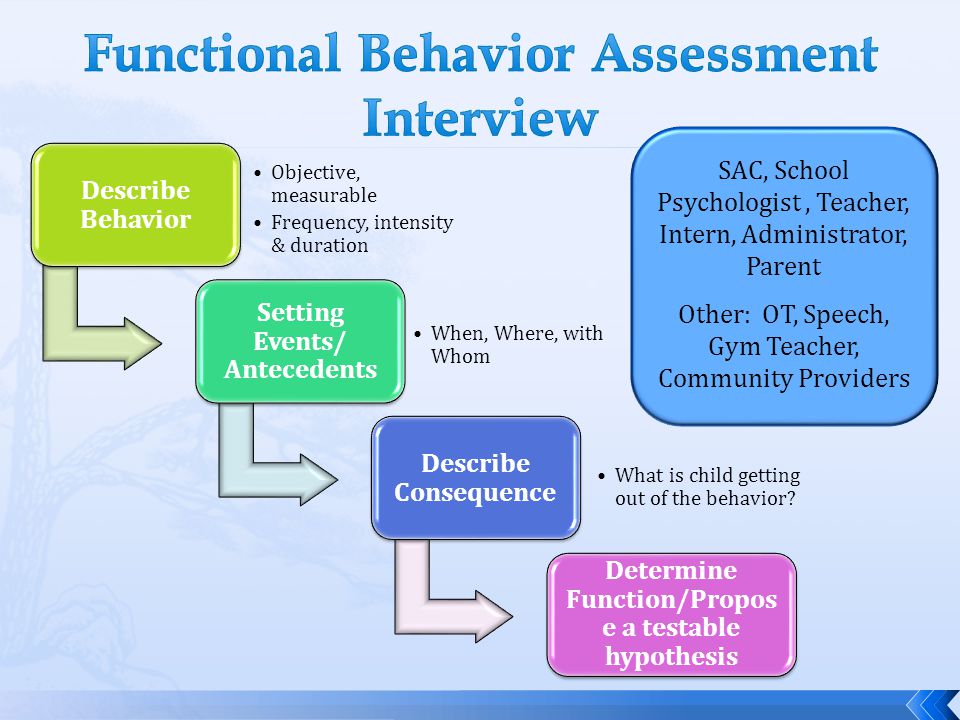

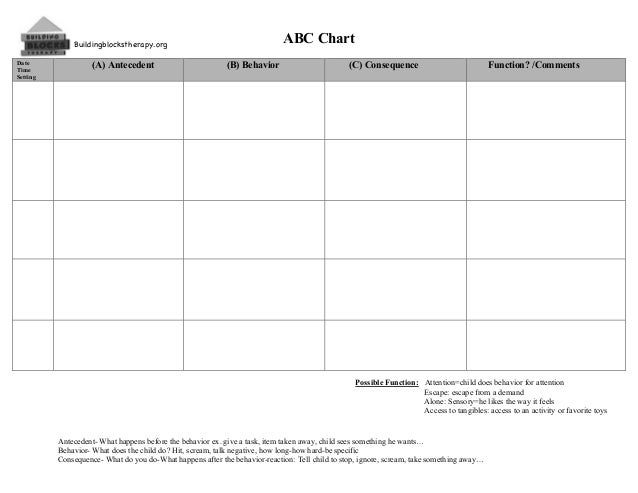

What is Antecedent-Behavior Consequence (ABC)?

Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence (ABC) is a significant component of understanding the function of behavior. If a child is in ABA therapy or a therapeutic preschool program for additional behavioral support, their teachers and therapists will often examine these components of behavior.

If a child is in ABA therapy or a therapeutic preschool program for additional behavioral support, their teachers and therapists will often examine these components of behavior.

What exactly does ABC mean?

Antecedent: This refers to the stimuli or activity that occurs just before a child exhibits the behavior. In some cases, the antecedent is also the root cause of the behavior for the child.

Behavior: This refers to the behavior that follows the antecedent.

Consequence: This refers to the event or consequence that follows the behavior.

By looking at a behavior in a logical chain of progression, it is easier to determine the function of a behavior and better understand why a child is acting in a certain way.

Here’s an example of using ABC to understand a child’s behavior:

Antecedent: The therapeutic preschool teacher prompts the student to come to the carpet for circle time.

Behavior: The child will not move and begins to cry that they do not want to join circle time.

Consequence: The therapeutic preschool aid stays with the child to try and help the child regulate their behavior.

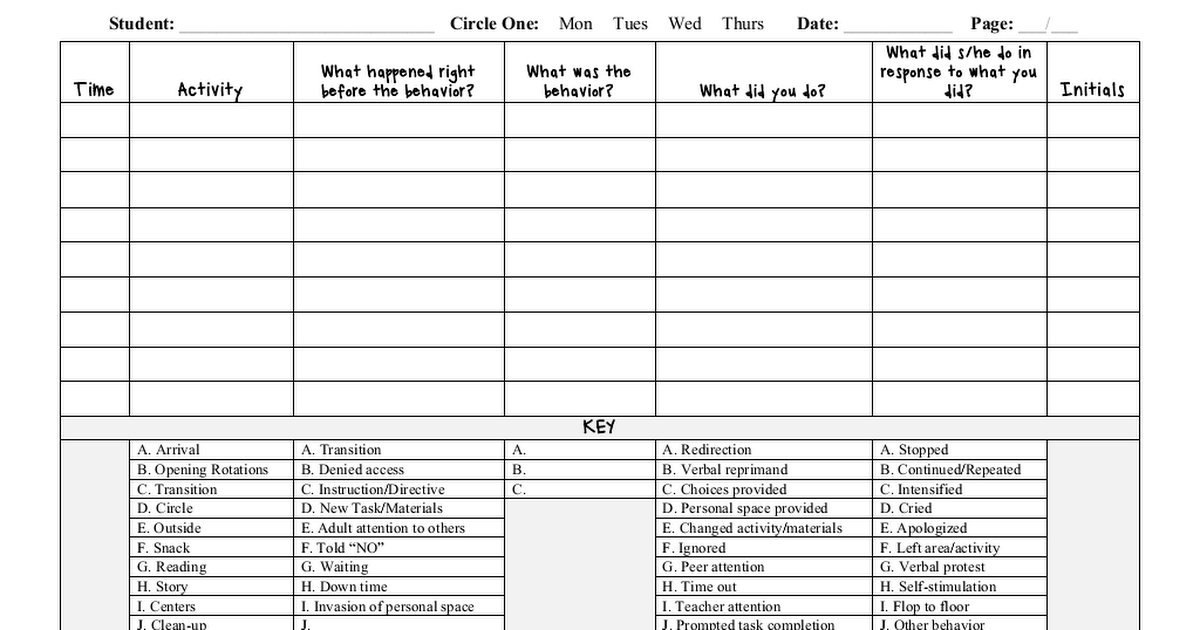

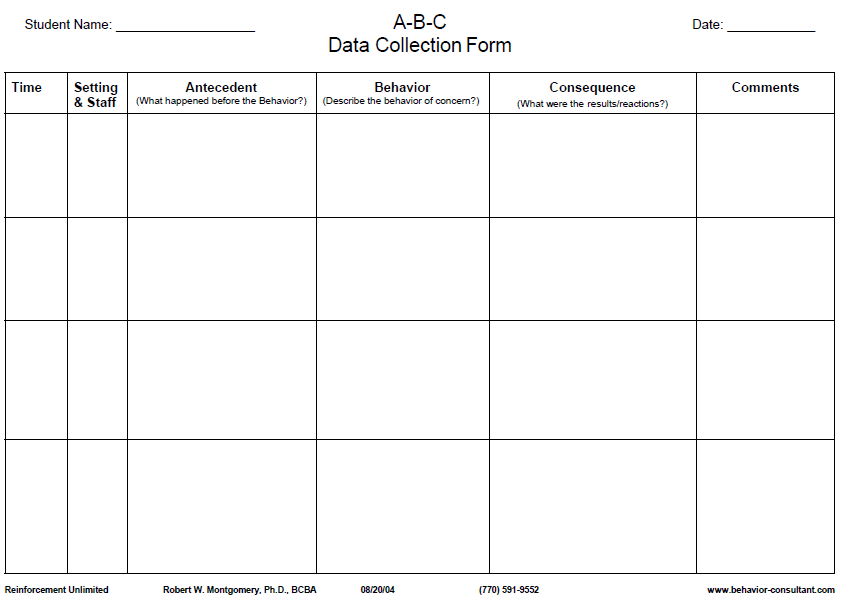

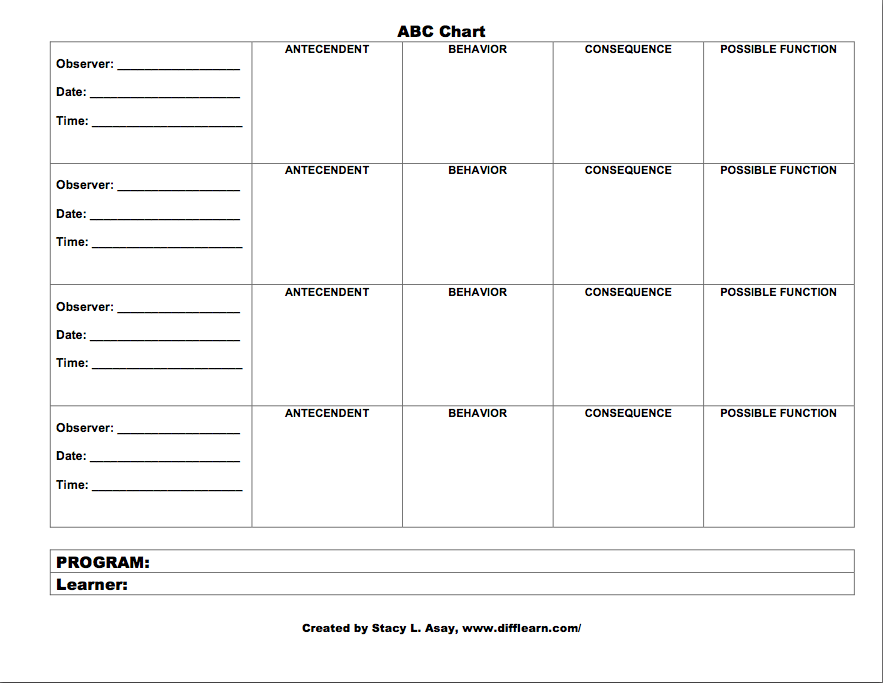

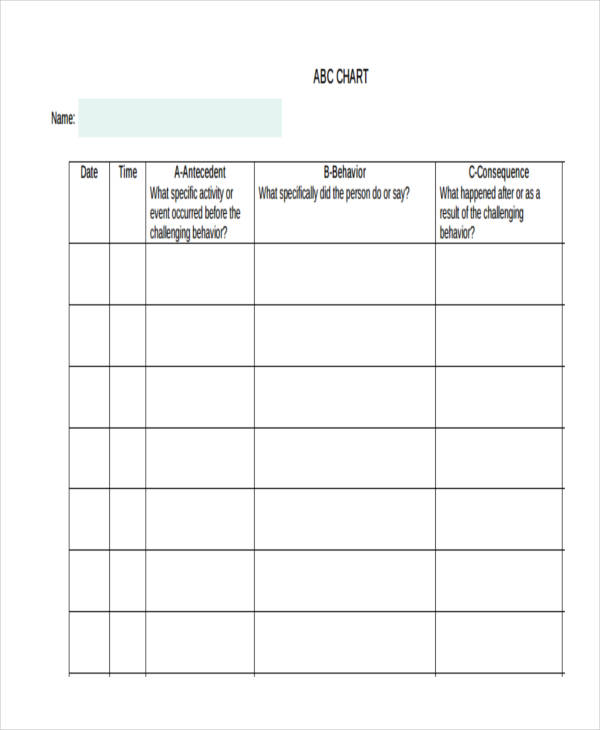

ABC chart

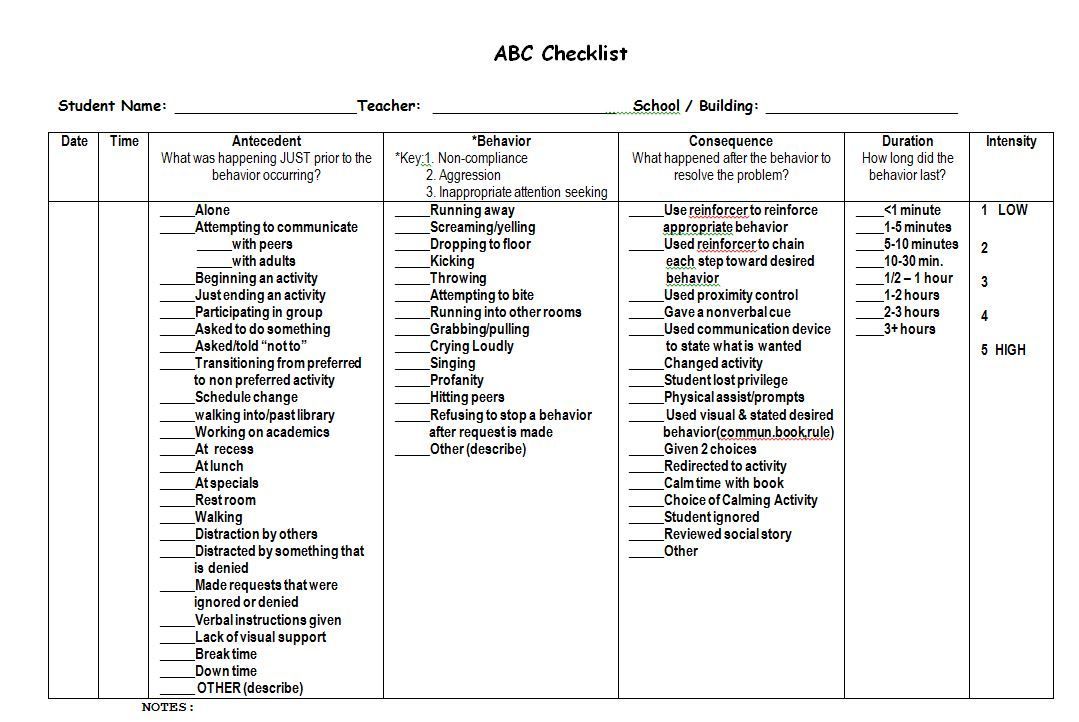

ABA therapists will often use ABC charts to map out specific behaviors and examine the function of behavior in children. By looking at the entire cycle of a behavior, from the stimuli that incites the behavior to the consequence, the therapist or teacher has a greater understanding of a child’s behavioral patterns. The insight that an ABC chart provides also helps to create a comprehensive treatment plan.

Why is ABC important?

If a child is exhibiting problematic behaviors at home or in their therapeutic preschool program, it is critical to understand the function of the behavior, in order to resolve it. Every child has their own way of learning and processing information, so two children who are crying during their therapeutic preschool class may be doing so for two completely different reasons. In order to solve the behavior “puzzle,” an ABA therapist or therapeutic preschool teacher may use ABC charts.

ABC is particularly important in the context of applied behavior analysis or ABA therapy services provided in a therapeutic preschool program. Using this method of intervention, the teacher or therapist will work with the child to build positive behaviors and skills and resolve problematic behaviors. ABA also looks at the function of behavior.

Do you think your child could benefit from a therapeutic preschool program for behavior support? Contact CST Academy by clicking the purple button below or calling 773-620-7800 to learn more about our services for children in Chicago, including ABA therapy, feeding therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy.

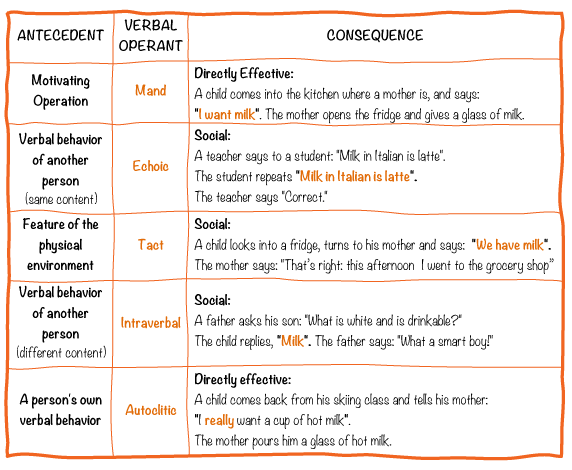

How to teach a child with autism to use "words" instead of "scandals"?

04/12/14

Negative behavior for autism is often a consequence of the difficulties with communication

Source: Let’s Talk

9000

Many children with autism use unwanted forms of behavior to satisfy their needs. This can be very frustrating for parents and educators because this behavior interferes with learning and daily activities. However, the truth of life is that people do what works for them! If any behavior of the child continues, then this means that, to one degree or another, the behavior "works" for this child. In other words, there is a certain need of the child, which is satisfied with the help of this behavior. If we determine what the need is, then we can change the strength of the need and/or teach the child a more appropriate way to communicate it. Beyond that, we have to teach his child that his old way of "communication" no longer works!

This can be very frustrating for parents and educators because this behavior interferes with learning and daily activities. However, the truth of life is that people do what works for them! If any behavior of the child continues, then this means that, to one degree or another, the behavior "works" for this child. In other words, there is a certain need of the child, which is satisfied with the help of this behavior. If we determine what the need is, then we can change the strength of the need and/or teach the child a more appropriate way to communicate it. Beyond that, we have to teach his child that his old way of "communication" no longer works!

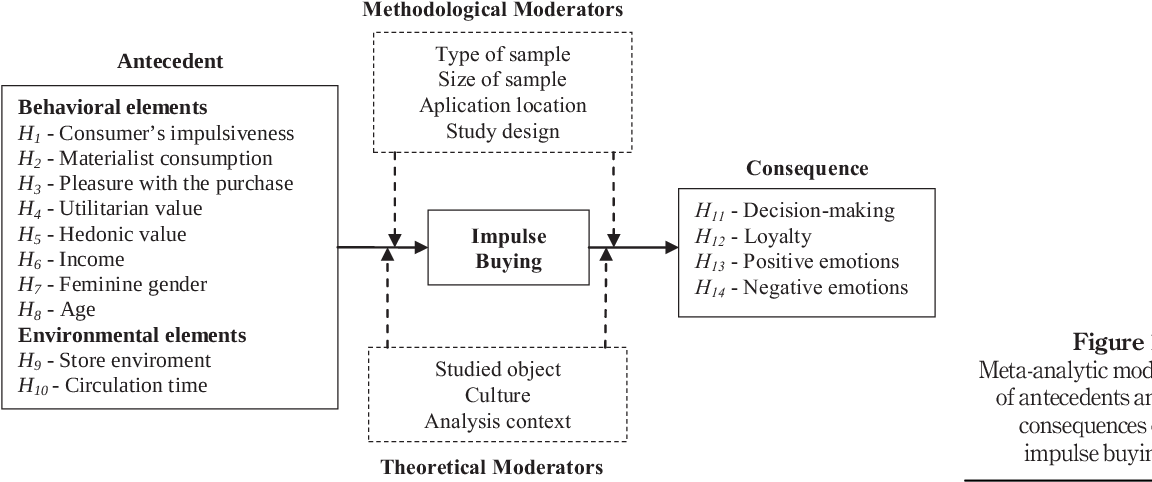

The three main "needs" that negative behavior can communicate (functions of behavior) are:

1. Getting attention or desired items.

2. Avoidance or escape from a requirement or situation.

3. Behavior brings pleasure in itself.

The first step in dealing with a behavioral problem is to try to understand why the child is reacting in a certain way. Parents or educators often have their own preconceived ideas about the cause of behavior. For example, they may claim that the reason is that the child is stubborn, unwell, hungry, or spoiled by his grandmother! Of course, we all get "out of the mood" for a variety of reasons, but if a behavioral problem occurs regularly, then there is a connection between this behavior and what happens before / after the behavior. It is these events that cause the behavior to repeat itself. The task of the behavioral analyst is to determine this connection, which allows you to develop the right plan for correcting this behavior. It is very important that all participants do not look for "guilty" in the behavior of the child. This will only make people defensive and resentful, and this is not a healthy situation for the team or the family. No one teaches a child to “behave badly” consciously! Instead, a team of parents and professionals should collect information about problem behavior and treat it as a problem-solving process.

Parents or educators often have their own preconceived ideas about the cause of behavior. For example, they may claim that the reason is that the child is stubborn, unwell, hungry, or spoiled by his grandmother! Of course, we all get "out of the mood" for a variety of reasons, but if a behavioral problem occurs regularly, then there is a connection between this behavior and what happens before / after the behavior. It is these events that cause the behavior to repeat itself. The task of the behavioral analyst is to determine this connection, which allows you to develop the right plan for correcting this behavior. It is very important that all participants do not look for "guilty" in the behavior of the child. This will only make people defensive and resentful, and this is not a healthy situation for the team or the family. No one teaches a child to “behave badly” consciously! Instead, a team of parents and professionals should collect information about problem behavior and treat it as a problem-solving process.

To identify a connection, it is necessary to observe and record for a long time what happened immediately before the behavior (antecedent) and immediately after it (consequence). Recordings can be made by people who interact directly with the child on a regular basis, or by an independent monitor. Only the information that can be observed is recorded, with no impression of what caused the behavior. For example, instead of writing "Sam was hungry" as an antecedent, the observer should write "Sam stood by the fridge and Mom asked, 'What do you want?' Instead of writing "Sam started acting up" as a description of the behavior, the observer should write "Sam fell to the floor, screamed and kicked the floor." Instead of writing "Mom punished him" as a consequence, the observer should write "Mom picked him up and put him in a chair." From now on, we collect only "facts" and do not try to interpret them. It's also helpful to record what time of day the behavior occurred, as well as other circumstances, to help identify patterns in behavior.

Once you have collected information over a sufficient period of time, the child's team will analyze it to identify patterns in the events that occur before and after the behavior. For example, let's say that when the team analyzed Sam's behavior, they noticed that there were no patterns in what happens after the behavior. Perhaps one person left when the tantrum began, another tried to calm the child, and a third put him in a corner. The only thing that united the situations was that someone asked: “What do you want?” So the team determines that there is a connection between someone asking "What do you want?" (antecedent) and hysteria (behavior).

On the other hand, it is possible that the collected information indicated a different connection. Perhaps one person said, “What do you want?” and another asked, “Are you hungry?” and a third opened the refrigerator and gave Sam juice. The only thing that unites all cases of hysteria is what happened after it (consequence). Everyone started showing Sam various objects until they found what he wanted, after which he stopped crying. This indicates a relationship between the behavior and obtaining the desired item.

This indicates a relationship between the behavior and obtaining the desired item.

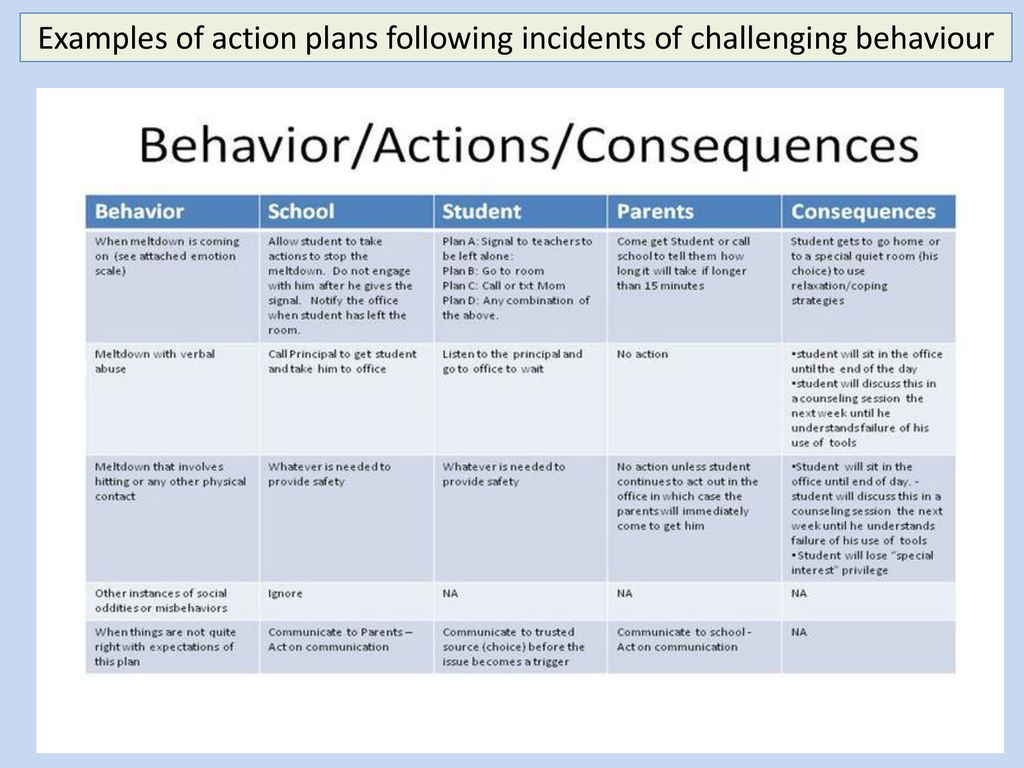

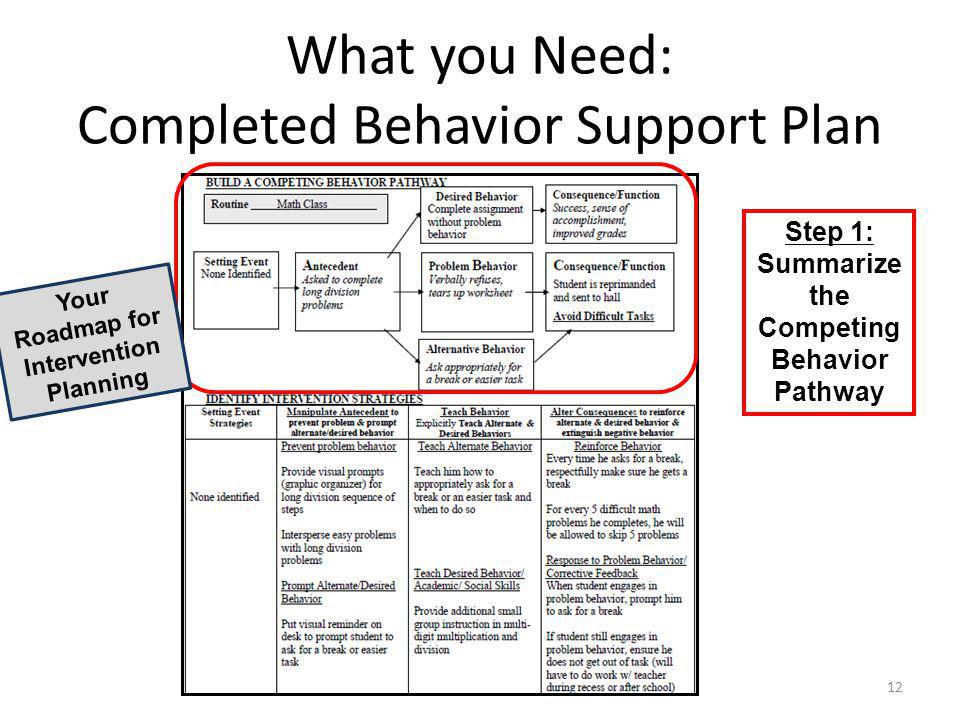

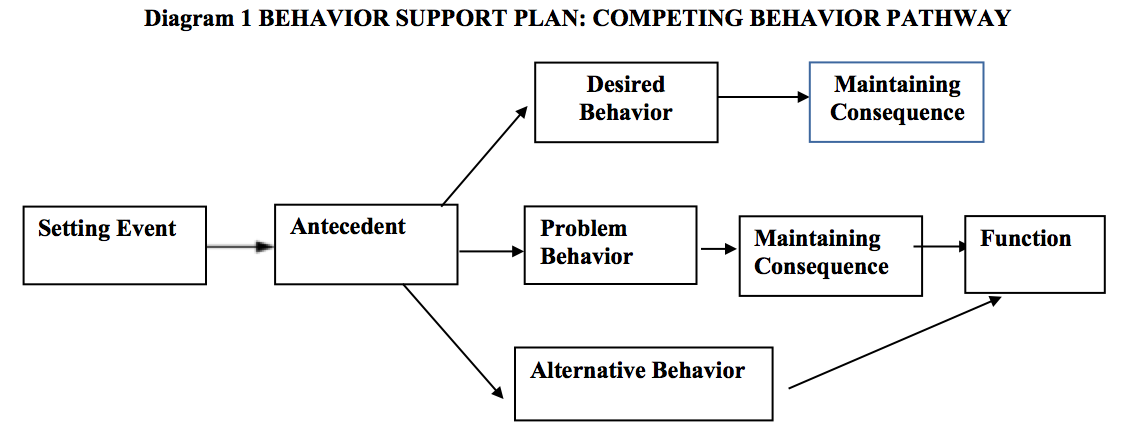

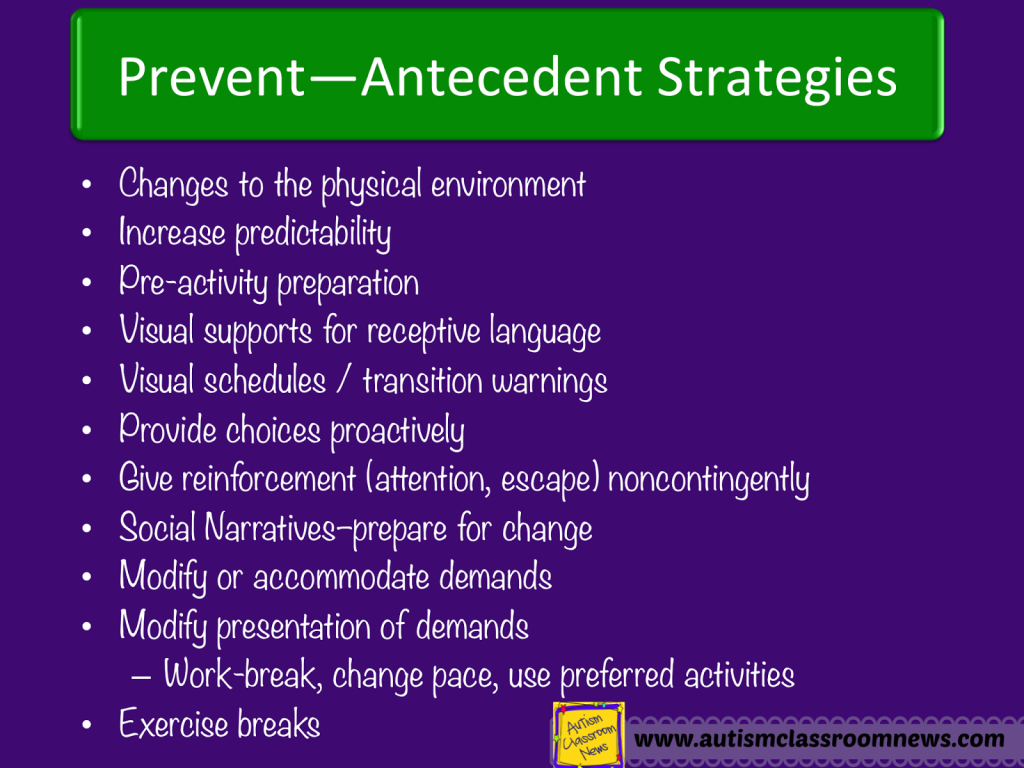

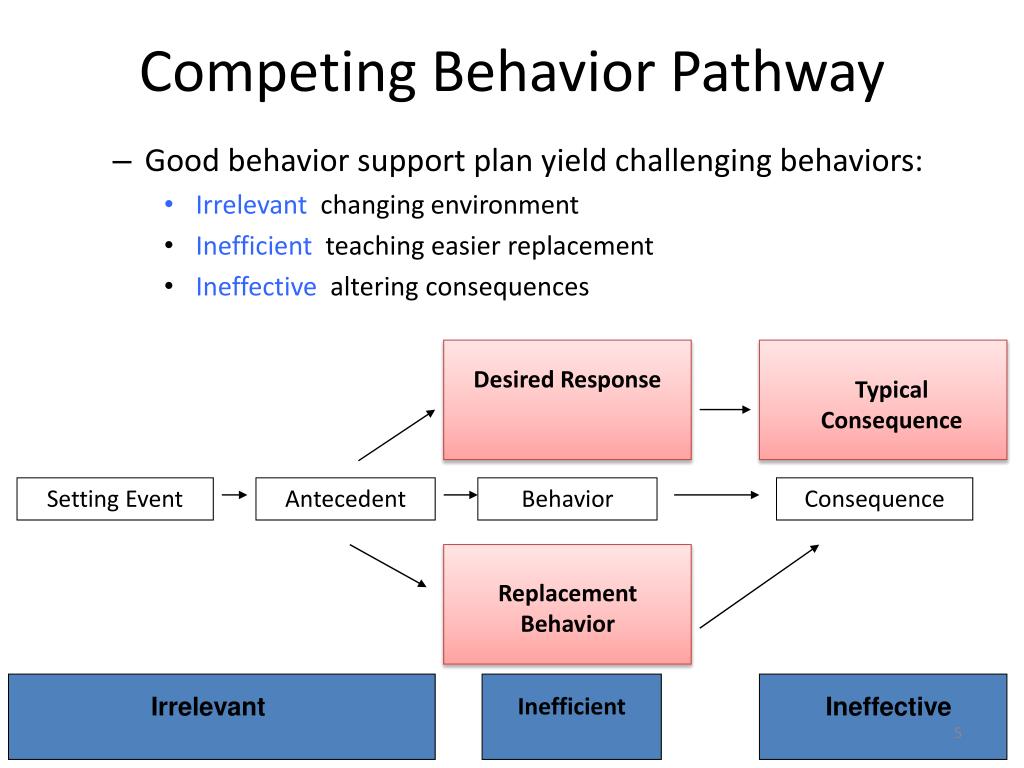

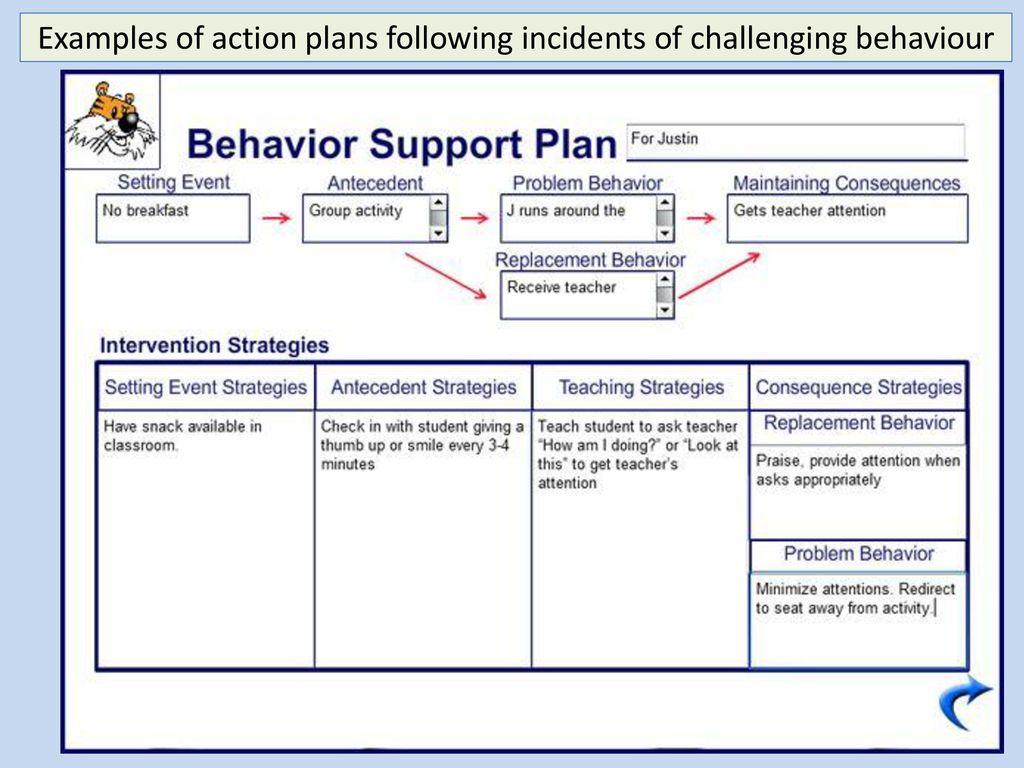

Once the connection is established, a plan is developed to correct the problem behavior. Typically, procedures to reduce unwanted behavior include: 1) modifying what happens before the behavior (control of antecedents), 2) refusing to provide a reward that supports the behavior (extinction), 3) teaching the child an alternative behavior that will be more effective in obtaining the reward. (differential encouragement of alternative behavior). The goal is to teach the child a replacement behavior (words, gestures, or picture/object exchange) that will serve the same function as the negative behavior. The desirable and undesirable behavior in such a situation is called an “equivalent pair”.

For example, Sam's team found that tantrums happen when he is asked "What do you want?" (antecedent), and, therefore, it will be necessary to abandon this phrase for a while. Instead, the team may decide to open the fridge right away and give Sam a choice of items he may want. As soon as he reaches for the object, the adult can prompt Sam to use a word, gesture, picture, or object to indicate what he wants. For such a request, an adult can specifically plan and provide him with more of what he wants than he usually receives (differential reward of alternative behavior). The prompts then gradually decrease until Sam is able to ask for what he wants before even reaching the fridge!

As soon as he reaches for the object, the adult can prompt Sam to use a word, gesture, picture, or object to indicate what he wants. For such a request, an adult can specifically plan and provide him with more of what he wants than he usually receives (differential reward of alternative behavior). The prompts then gradually decrease until Sam is able to ask for what he wants before even reaching the fridge!

Of course, Sam will also need to be taught to be tolerant of the question “What do you want?” because sooner or later he will be asked such a question! Sam clearly has a dislike for these words, and most likely this is due to the fact that he did not like what happened when he heard these words before. For example, maybe someone held his favorite toy in front of his eyes and asked, "What do you want?" over and over without giving him access to the toy. As mentioned earlier, it is important not to dive into the question of how this happened, the blame game is bad for the team and for the family. But it is important that everyone on the team understands how different learning strategies affect the child. And still, the main goal is to solve the problem. In this case, part of Sam's program may be prompting him to ask for a small amount of the desired food and gradually "training" him to the question between servings of his favorite treat. Or perhaps the team will combine these words with encouragement, simply saying them when Sam is doing something enjoyable and not requiring him to respond. For example, when Sam watches a favorite video, he might be told, “What do you want? Video", in a calm and soothing voice. It is very important to say both the question and the answer at once, so that the child does not get used to the fact that after the question no answer is needed. Then, perhaps, the video will be paused, and Sam will be prompted to ask for the video in the form in which he can do it (words, pictures, gestures, objects).

But it is important that everyone on the team understands how different learning strategies affect the child. And still, the main goal is to solve the problem. In this case, part of Sam's program may be prompting him to ask for a small amount of the desired food and gradually "training" him to the question between servings of his favorite treat. Or perhaps the team will combine these words with encouragement, simply saying them when Sam is doing something enjoyable and not requiring him to respond. For example, when Sam watches a favorite video, he might be told, “What do you want? Video", in a calm and soothing voice. It is very important to say both the question and the answer at once, so that the child does not get used to the fact that after the question no answer is needed. Then, perhaps, the video will be paused, and Sam will be prompted to ask for the video in the form in which he can do it (words, pictures, gestures, objects).

While all of this can prevent tantrums in principle, it is very important to plan how to behave if a tantrum does occur. Reward, by definition, comes after the behavior. Even though each person in the first example behaved differently, the behavior was rewarded because it persisted. In fact, if a behavior is only occasionally rewarded (variable reward schedule), then getting rid of such behavior is much more difficult! So the team might decide that every time Sam makes a fuss instead of a request, they will use the following counting procedure. Once Sam stops crying, the adult will count to ten and then tell him how to ask for what he wants. When a child fights to get what he wants, it is very important never to give him what he wants (encouragement) in return for the fight. Unfortunately, if you give him what he wants in response to negative behavior only occasionally, then the likelihood of a new tantrum when he wants something will increase many times over. To understand why this is happening, imagine a slot machine in Las Vegas. The fact that a win (reward) does not happen every time a person puts money into it makes people spend more and more, they always think that the next quarter is sure to hit the jackpot! We are not saying at all that the child is consciously planning this, it just happens if, after the first tantrum, the child got what he wanted.

Reward, by definition, comes after the behavior. Even though each person in the first example behaved differently, the behavior was rewarded because it persisted. In fact, if a behavior is only occasionally rewarded (variable reward schedule), then getting rid of such behavior is much more difficult! So the team might decide that every time Sam makes a fuss instead of a request, they will use the following counting procedure. Once Sam stops crying, the adult will count to ten and then tell him how to ask for what he wants. When a child fights to get what he wants, it is very important never to give him what he wants (encouragement) in return for the fight. Unfortunately, if you give him what he wants in response to negative behavior only occasionally, then the likelihood of a new tantrum when he wants something will increase many times over. To understand why this is happening, imagine a slot machine in Las Vegas. The fact that a win (reward) does not happen every time a person puts money into it makes people spend more and more, they always think that the next quarter is sure to hit the jackpot! We are not saying at all that the child is consciously planning this, it just happens if, after the first tantrum, the child got what he wanted. (Variable reward scheme). Moreover, if the child was always given what he wanted (rewarded) after the tantrum (constant reward scheme), then it would be easier to eradicate such behavior. For example, consider a candy machine. In the past, we always got a candy when we put down the money, and then suddenly the machine stopped dispensing candy. After that, we simply will not put money into it in the future. Unlike the slot machine example, our behavior will stop very quickly!

(Variable reward scheme). Moreover, if the child was always given what he wanted (rewarded) after the tantrum (constant reward scheme), then it would be easier to eradicate such behavior. For example, consider a candy machine. In the past, we always got a candy when we put down the money, and then suddenly the machine stopped dispensing candy. After that, we simply will not put money into it in the future. Unlike the slot machine example, our behavior will stop very quickly!

It is very important to understand that once we start to deny a child the reward of unwanted behavior (extinction procedure), we tend to see a dramatic increase in that behavior. In this case, it could be an escalation of Sam's tantrums and an increase in their duration. This phenomenon is called the "extinction explosion" and it will quickly subside if we are consistent and do not provide incentives. An example of an extinction explosion: a person is used to getting candy from a machine after putting money in it, but after one day he did not receive the expected reward, he starts kicking the machine. It is very important to “survive” the extinction explosion, and not immediately decide that the intervention does not work.

It is very important to “survive” the extinction explosion, and not immediately decide that the intervention does not work.

Sometimes, even if the behavior has stopped due to the denial of the reward (extinction), the child may suddenly resume the old behavior. Again, it is very important to follow the same procedure and not allow the child to access the reward. If this is not done, then the old behavior will return with renewed vigor, and in the future it may be much less prone to extinction!

Because of the importance of consistency in responding to a child's behavior, it is important that everyone who works and interacts with the child is aware of the plan. It is best to explain the procedure in the simplest language so that everyone understands what to do. The procedures should be explained, as well as the importance of everyone, without exception, sticking to the plan. If a behavior is encouraged in some cases but not in others, it will become even more resistant to extinction. For example, let's say that Sam's parents have been working hard to teach Sam to ask for what he wants with gestures, but one day a new nanny comes to babysit. The babysitter didn't know anything about Sam's old temper tantrums or procedures to prevent them, so when Sam went to the fridge and started crying, the babysitter started offering him various foods he might want. All the work the parents had done to die out tantrums went down the drain, and the behavior was more resistant to extinction because tantrums were once again encouraged!

For example, let's say that Sam's parents have been working hard to teach Sam to ask for what he wants with gestures, but one day a new nanny comes to babysit. The babysitter didn't know anything about Sam's old temper tantrums or procedures to prevent them, so when Sam went to the fridge and started crying, the babysitter started offering him various foods he might want. All the work the parents had done to die out tantrums went down the drain, and the behavior was more resistant to extinction because tantrums were once again encouraged!

In summary, we must teach the child to use gestures, words, and images/objects to communicate their wants and needs. At the same time, we must teach the child that negative behaviors will not lead to the desired result!

ABA Therapy and Behavior, Parenting Children with Autism, Communication and Speech, Techniques and Treatment

Teaching Without Mistakes in Autism Treatment with ABA

17.04.13

successfully used in working with children with developmental disabilities, is "learning without errors"

Author: Zukhra Izmailova-Kamar

Applied Behavioral Analysis or ABA (Applied Behavioral Analysis) is a science that studies the issues of behavior analysis and modification. In ABA, "behavior" is any human action that is directly observable and measurable. In the current literature, the term "ABA" is most often used in connection with the therapeutic education of children diagnosed with autism. However, ABA methods are used not only for therapeutic purposes, but also in the process of teaching children any new skills.

In ABA, "behavior" is any human action that is directly observable and measurable. In the current literature, the term "ABA" is most often used in connection with the therapeutic education of children diagnosed with autism. However, ABA methods are used not only for therapeutic purposes, but also in the process of teaching children any new skills.

Burres Frederick Skinner (03/20/1904 - 08/18/1990), an American psychologist and writer, is considered to be the founder of the ABA. B.F. Skinner was the first to use the term "behavioral analysis" and put it at the head of the study of ABA, believing that behavior has the right to be an independent object of study, and not just be an integral part of the study of thought processes, the work of the brain or the human psyche. Skinner suggested leaving the study of the "concept of consciousness" to philosophers, and ABA science to focus on behavior as the object of study.

After Dr. Ivar Lovaas applied ABA methods to children diagnosed with autism, Applied Behavior Analysis gained wide acceptance and acceptance. In modern literature, the term "ABA" is most often mentioned in connection with the therapeutic education of children diagnosed with autism. However, I find it necessary to clarify that ABA methods are used not only for therapeutic purposes, but also in the process of teaching children new skills, for example: working on spelling or identifying shapes, colors, and so on. Methods of Applied Behavior Analysis can be used in work with children with various types of developmental disabilities, in work on behavior correction.

In modern literature, the term "ABA" is most often mentioned in connection with the therapeutic education of children diagnosed with autism. However, I find it necessary to clarify that ABA methods are used not only for therapeutic purposes, but also in the process of teaching children new skills, for example: working on spelling or identifying shapes, colors, and so on. Methods of Applied Behavior Analysis can be used in work with children with various types of developmental disabilities, in work on behavior correction.

Those interested in the history of behaviorism (a trend in the history of psychology that believes that the subject of psychology is not consciousness, but behavior) will find many critical articles that do not agree with Skinner's theory. Criticism, in particular, refers to the "theory of learning", which is different from the pedagogical concepts of learning, education and upbringing known to us. And, nevertheless, it is correct learning, as the mastering of basic skills by the student, that leads to a successful learning process and the achievement of educational goals by the teacher. It is from this point of view that I propose to consider the use of ABA methods in the process of working in a class of correctional pedagogy.

It is from this point of view that I propose to consider the use of ABA methods in the process of working in a class of correctional pedagogy.

One of the ABA methods that has been successfully used in working with children with developmental disabilities is the “learning without mistakes” method.

Learning without errors is a learning procedure that assumes a specific instruction S D (discriminative stimulus) and a specific prompt level with the goal of eliciting a specific and only correct response []. The correct answer is necessarily rewarded with a reinforcing stimulus. In the role of reinforcement, praise, a toy, a cookie, an introduction to a favorite pastime, for example: a walk or watching an excerpt from your favorite cartoon, can be used.

Example: the teacher lays out three figures on the table in front of the student: a square, a triangle and a circle.

Teacher: Show the square (certain, specific instruction).

The teacher points with his finger to the correct answer (gesture prompt).

The student points to a square.

The teacher praises the student: “Well done, excellent!”

To understand how the Learning Without Error theory works, it is necessary to consider some ABA principles. In particular, we will consider the A → B → C paradigm, where A is the antecedent, B is the behavior, and C is the consequence.

The antecedent is what is present in the environment of the child to manifestations of behavior. Everything that precedes behavior is called in Applied Behavior Analysis an antecedent.

If we consider the above example from the point of view of the A → B → C paradigm, then the antecedent is the teacher's instruction: "show the square." The behavior in this example is the student's choice of the correct figure. But any behavior has a consequence, in our example, the consequence is the encouragement of the teacher: “well done, excellent!”. Antecedent, behavior and consequence are the main factors involved in every teacher-student interaction. Knowing that ABC exists is good, however, it is important to know the ethical and systematic ways to manipulate them before we can use these components for learning [2].

Antecedent, behavior and consequence are the main factors involved in every teacher-student interaction. Knowing that ABC exists is good, however, it is important to know the ethical and systematic ways to manipulate them before we can use these components for learning [2].

Not every antecedent can be the same defined instruction that we need so badly in using the Learning Without Errors method. A specific instruction (S D ) is also called a discriminative stimulus. The main goal of the discriminative stimulus (S D ) is to create a history of awakening a certain (specific) behavior. This is the difference between the antecedent S D and any other antecedent. Antecedent to be called S D must have a history of awakening a particular behavior. So, the antecedent (A) “show the square” is a discriminative stimulus (S D ) for the student, giving a signal to choose behavior (B), in this example, to choose the correct answer (A → B). "C" is, as mentioned earlier, the consequence that follows the behavior. What should we know about the aftermath? The consequence, if desired, reinforces the behavior shown. In other words, if we manage to achieve something positive and pleasant, then we will try to perform similar behavior again in the same situation to achieve the same goal. When I talk about the consequence of error-free learning, I'm talking about a reinforcer (S R). The only difference between any consequence and the consequence S R (reinforcing stimulus) is also history. By ending the interaction with the student by providing a targeted, specific consequence, called a reinforcing stimulus or S R (reinforcing stimulus), the teacher creates a reinforcing story. In our example, S R is the teacher’s praise “Well done, excellent!”

"C" is, as mentioned earlier, the consequence that follows the behavior. What should we know about the aftermath? The consequence, if desired, reinforces the behavior shown. In other words, if we manage to achieve something positive and pleasant, then we will try to perform similar behavior again in the same situation to achieve the same goal. When I talk about the consequence of error-free learning, I'm talking about a reinforcer (S R). The only difference between any consequence and the consequence S R (reinforcing stimulus) is also history. By ending the interaction with the student by providing a targeted, specific consequence, called a reinforcing stimulus or S R (reinforcing stimulus), the teacher creates a reinforcing story. In our example, S R is the teacher’s praise “Well done, excellent!”

So we have built a complete formula, according to the principles of ABA science: A→B→C. The ABC paradigm also underlies the Discrete Block Learning method, a method that is used to teach individual skills and is closely related to the “learning without errors” method [3].

Robert Schramm in his book Verbal Behavior as an approach to ABA notes that any learning process in ABA will have these three parts. S D signals to the child that S R is available and S R acts as a reason why the child will exhibit this behavior in the future, namely to choose the correct answer. “Using a learning system that assumes success will allow you to teach without coercion, and will eliminate the child's attempts to evade learning. No matter which reinforcer you use, it will be of more value to your child if the child receives enough support and help from you to work on the skill, which ultimately leads him to success in the learning process” [2].

This is where the hint comes into play. Before I continue, I would like to dwell on the definition of the word "hint". A prompt is a specific action, physical or verbal (verbal), necessary to wake up and get the right answer. The purpose of such a hint is to prevent the child from making a mistake and to reinforce the correct answer or manifestation of the skill that you are teaching. Any hint fulfills its role only when it is not overfulfilled. That is, you should always remember that the child should have space to think about choosing the right answer.

Any hint fulfills its role only when it is not overfulfilled. That is, you should always remember that the child should have space to think about choosing the right answer.

Hints are different. The prompt can be physical or verbal.

A physical prompt involves physical contact, for example: you take a child's hand and help him choose a square among three figures on the table. Physical cues can be used to build spelling skills, work on self-care skills, and teach your child how to properly wash their hands. Reducing the physical cue may be that, by taking the child’s hand and placing it on the table near the “square” figure, you allow him to make the right choice on his own. Or, if in the process of teaching a child to trace a drawing along a contour, you, having begun a “hand in hand” line, remove your hand, allowing the student to complete the work on his own.

Motion simulation is also a kind of hint. It is used when the child knows the answer but may not know when to apply it. As you work on the tossing ball skill, you can give the instruction to "toss the ball" and show the child how to do it.

As you work on the tossing ball skill, you can give the instruction to "toss the ball" and show the child how to do it.

We have already mentioned the gesture prompt at the beginning. The gesture shows the child the direction where to look for the correct answer. For example, the teacher instructs: show the letter "A" and with a look or gesture shows the direction where the student can find the desired letter.

If you, holding a pencil and a pen in your hand, give the instruction: “choose a pen” and, at the same time, bring your hand with a pen closer to the student, you, without giving the correct answer, suggest the answer, helping the child not to make a mistake . R. Schramm calls this type of hint positional.

The verbal prompt may be complete or partial. An example of a complete clue:

Teacher pointing to a picture with a ball: “What is this? It's a ball!"

The child repeats: "Ball!"

Teacher: “That's right, the ball! Well done!"

A partial prompt suggests that the child knows the answer but is either unsure of the correct answer or is unwilling to answer for some other reason.

Teacher: “What is this? This is me…”

Student: “The ball!”

Teacher: “That's right! It's a ball!"

To consolidate the work on the picture, the teacher can make an attempt to reduce the hint:

Teacher: "What is this? This is mmm…”

Student: “The ball…”

Teacher: “The ball! Excellent! (gives a favorite toy and lets the child play).

Reducing the prompt in ABA is called fading. “Fading is the process of giving a certain amount of support and then systematically decreasing that support at a pace that allows your child to continue to be successful in the process of becoming more independent. Any time you use a physical prompt, you should start with the most supportive prompt to help your child succeed. For example, you might want to start with a full physical prompt and scale it down to a partial physical prompt. When your child completes a task with only partial physical cues, you can start using gesture cues, or perhaps positional cues.