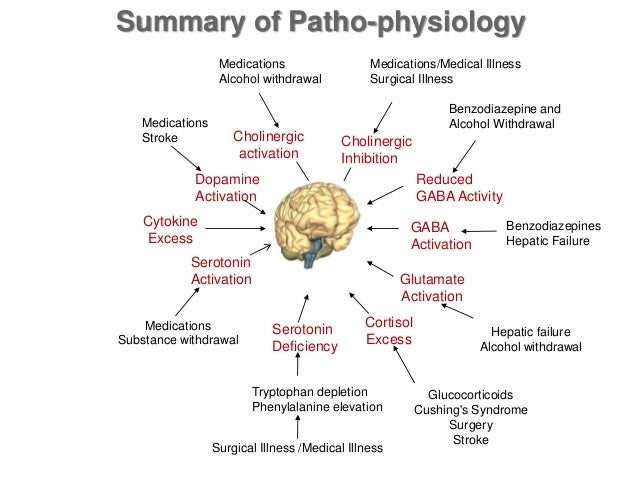

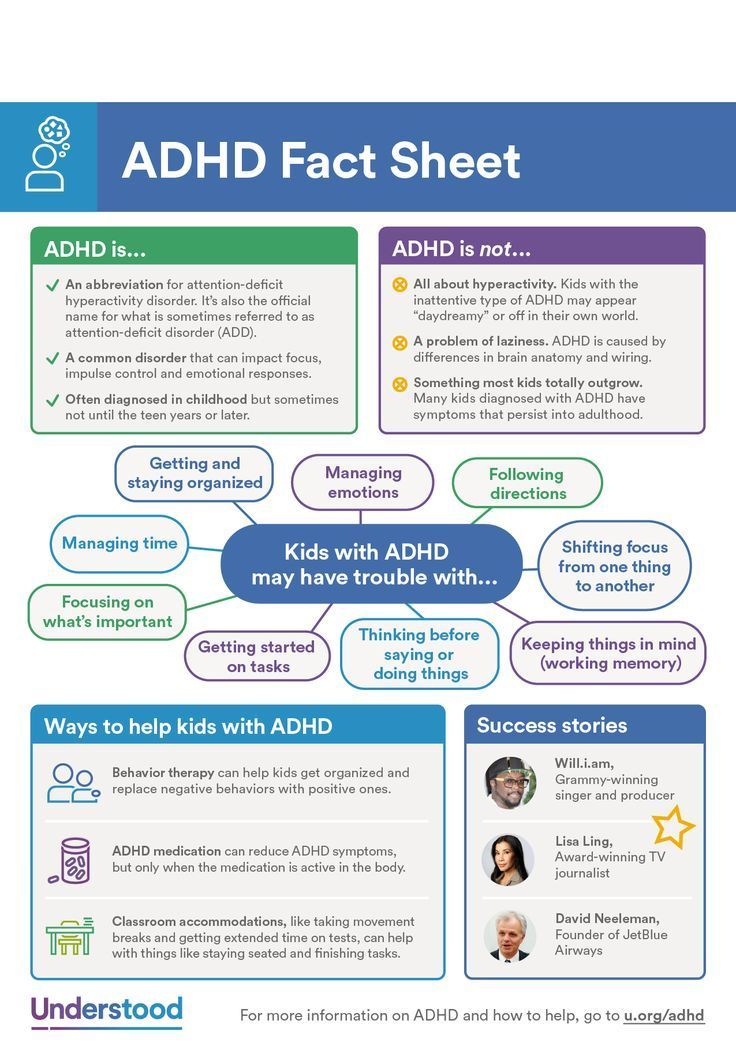

Etiology for adhd

Symptoms and Diagnosis of ADHD

COVID-19: Information for parenting children with ADHD

Learn more

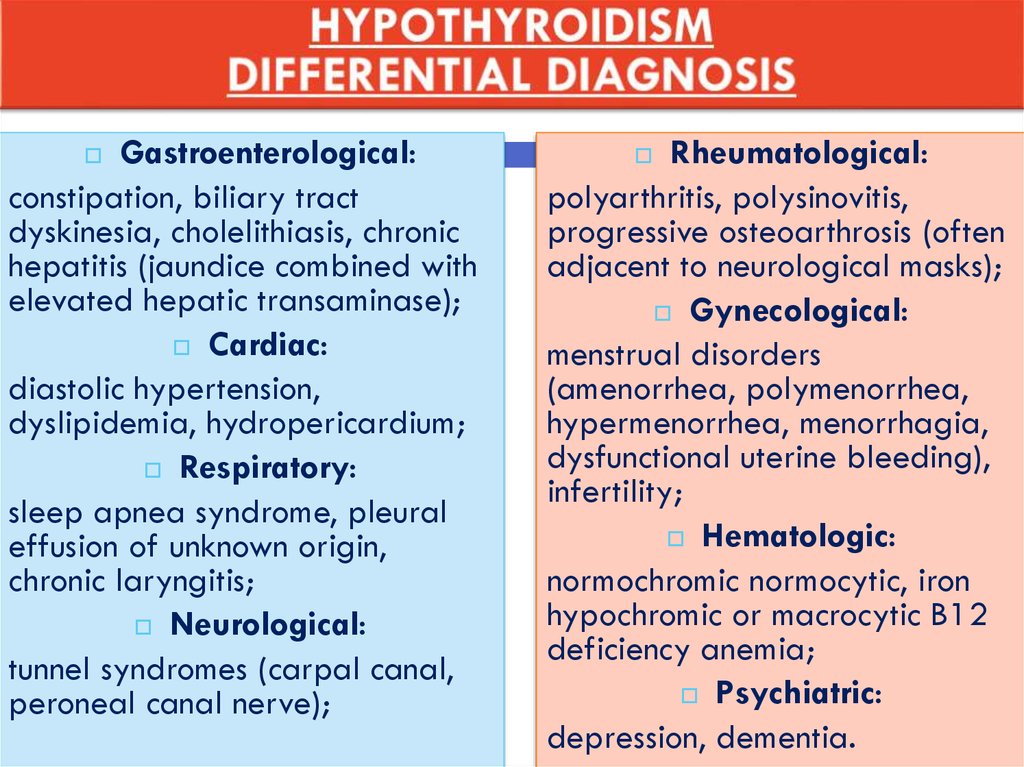

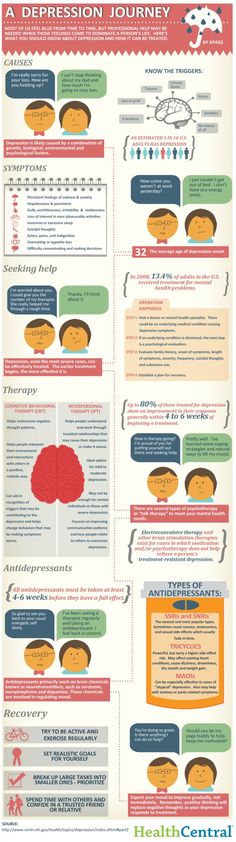

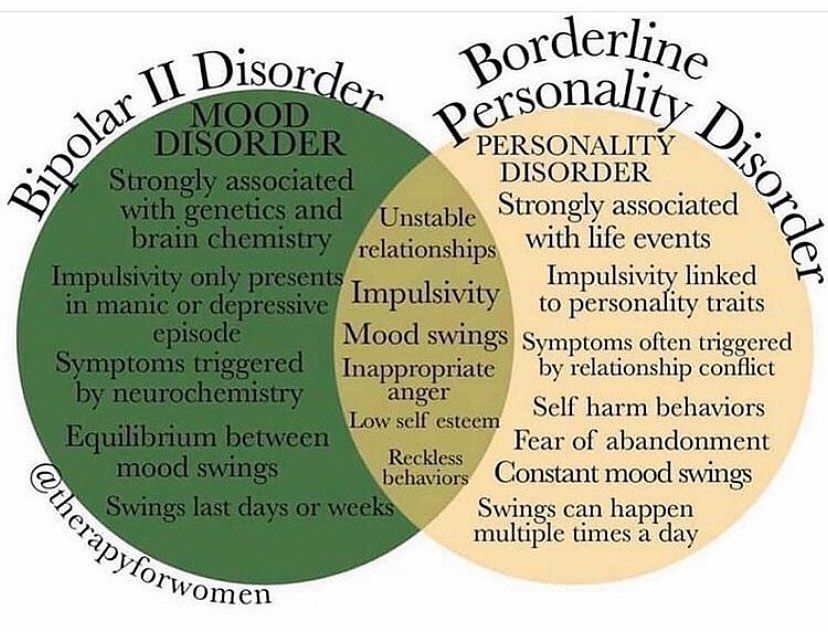

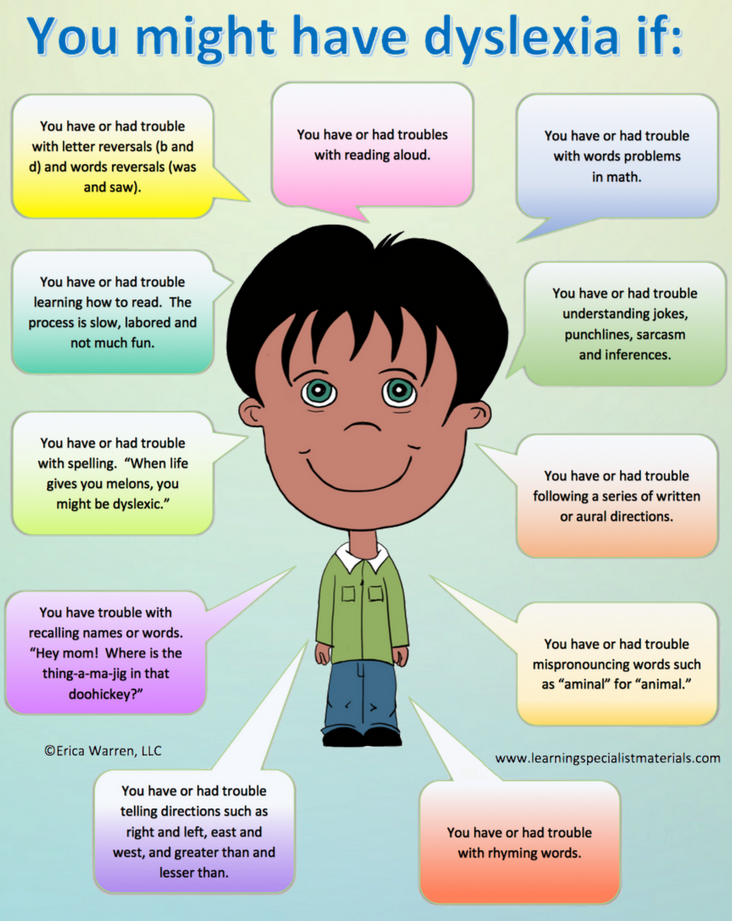

Deciding if a child has ADHD is a process with several steps. This page gives you an overview of how ADHD is diagnosed. There is no single test to diagnose ADHD, and many other problems, like sleep disorders, anxiety, depression, and certain types of learning disabilities, can have similar symptoms.

If you are concerned about whether a child might have ADHD, the first step is to talk with a healthcare provider to find out if the symptoms fit the diagnosis. The diagnosis can be made by a mental health professional, like a psychologist or psychiatrist, or by a primary care provider, like a pediatrician.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends that healthcare providers ask parents, teachers, and other adults who care for the child about the child’s behavior in different settings, like at home, school, or with peers. Read more about the recommendations.

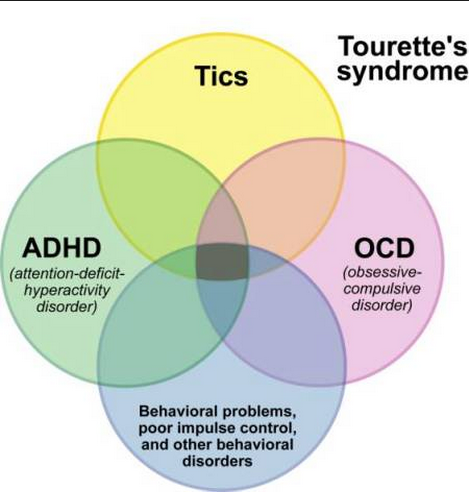

The healthcare provider should also determine whether the child has another condition that can either explain the symptoms better, or that occurs at the same time as ADHD. Read more about other concerns and conditions.

Why Family Health History is Important if Your Child has Attention and Learning Problems

How is ADHD diagnosed?

Healthcare providers use the guidelines in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, Fifth edition (DSM-5)1, to help diagnose ADHD. This diagnostic standard helps ensure that people are appropriately diagnosed and treated for ADHD. Using the same standard across communities can also help determine how many children have ADHD, and how public health is impacted by this condition.

Here are the criteria in shortened form. Please note that they are presented just for your information. Only trained healthcare providers can diagnose or treat ADHD.

Get information and support from the National Resource Center on ADHD

DSM-5 Criteria for ADHD

People with ADHD show a persistent pattern of inattention and/or hyperactivity–impulsivity that interferes with functioning or development:

- Inattention: Six or more symptoms of inattention for children up to age 16 years, or five or more for adolescents age 17 years and older and adults; symptoms of inattention have been present for at least 6 months, and they are inappropriate for developmental level:

- Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or with other activities.

- Often has trouble holding attention on tasks or play activities.

- Often does not seem to listen when spoken to directly.

- Often does not follow through on instructions and fails to finish schoolwork, chores, or duties in the workplace (e.g., loses focus, side-tracked).

- Often has trouble organizing tasks and activities.

- Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to do tasks that require mental effort over a long period of time (such as schoolwork or homework).

- Often loses things necessary for tasks and activities (e.g. school materials, pencils, books, tools, wallets, keys, paperwork, eyeglasses, mobile telephones).

- Is often easily distracted

- Is often forgetful in daily activities.

- Often fails to give close attention to details or makes careless mistakes in schoolwork, at work, or with other activities.

- Hyperactivity and Impulsivity: Six or more symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity for children up to age 16 years, or five or more for adolescents age 17 years and older and adults; symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity have been present for at least 6 months to an extent that is disruptive and inappropriate for the person’s developmental level:

- Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat.

- Often leaves seat in situations when remaining seated is expected.

- Often runs about or climbs in situations where it is not appropriate (adolescents or adults may be limited to feeling restless).

- Often unable to play or take part in leisure activities quietly.

- Is often “on the go” acting as if “driven by a motor”.

- Often talks excessively.

- Often blurts out an answer before a question has been completed.

- Often has trouble waiting their turn.

- Often interrupts or intrudes on others (e.g., butts into conversations or games)

- Often fidgets with or taps hands or feet, or squirms in seat.

In addition, the following conditions must be met:

- Several inattentive or hyperactive-impulsive symptoms were present before age 12 years.

- Several symptoms are present in two or more settings, (such as at home, school or work; with friends or relatives; in other activities).

- There is clear evidence that the symptoms interfere with, or reduce the quality of, social, school, or work functioning.

- The symptoms are not better explained by another mental disorder (such as a mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or a personality disorder). The symptoms do not happen only during the course of schizophrenia or another psychotic disorder.

Based on the types of symptoms, three kinds (presentations) of ADHD can occur:

- Combined Presentation: if enough symptoms of both criteria inattention and hyperactivity-impulsivity were present for the past 6 months

- Predominantly Inattentive Presentation: if enough symptoms of inattention, but not hyperactivity-impulsivity, were present for the past six months

- Predominantly Hyperactive-Impulsive Presentation: if enough symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity, but not inattention, were present for the past six months.

Because symptoms can change over time, the presentation may change over time as well.

Diagnosing ADHD in Adults

ADHD often lasts into adulthood. To diagnose ADHD in adults and adolescents age 17 years or older, only 5 symptoms are needed instead of the 6 needed for younger children. Symptoms might look different at older ages. For example, in adults, hyperactivity may appear as extreme restlessness or wearing others out with their activity.

To diagnose ADHD in adults and adolescents age 17 years or older, only 5 symptoms are needed instead of the 6 needed for younger children. Symptoms might look different at older ages. For example, in adults, hyperactivity may appear as extreme restlessness or wearing others out with their activity.

For more information about diagnosis and treatment throughout the lifespan, please visit the websites of the National Resource Center on ADHD and the National Institutes of Mental Health.

Reference

American Psychiatric Association: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition. Arlington, VA., American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

Treatment of ADHD | CDC

Get information and support from the National Resource Center on ADHD

My Child Has Been Diagnosed with ADHD – Now What?

When a child is diagnosed with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), parents often have concerns about which treatment is right for their child. ADHD can be managed with the right treatment. There are many treatment options, and what works best can depend on the individual child and family. To find the best options, it is recommended that parents work closely with others involved in their child’s life—healthcare providers, therapists, teachers, coaches, and other family members.

ADHD can be managed with the right treatment. There are many treatment options, and what works best can depend on the individual child and family. To find the best options, it is recommended that parents work closely with others involved in their child’s life—healthcare providers, therapists, teachers, coaches, and other family members.

Types of treatment for ADHD include

- Behavior therapy, including training for parents; and

- Medications.

Treatment recommendations for ADHD

For children with ADHD younger than 6 years of age, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends parent training in behavior management as the first line of treatment, before medication is tried. For children 6 years of age and older, the recommendations include medication and behavior therapy together — parent training in behavior management for children up to age 12 and other types of behavior therapy and training for adolescents. Schools can be part of the treatment as well. AAP recommendations also include adding behavioral classroom intervention and school supports. Learn more about how the school environment can be part of treatment.

AAP recommendations also include adding behavioral classroom intervention and school supports. Learn more about how the school environment can be part of treatment.

Good treatment plans will include close monitoring of whether and how much the treatment helps the child’s behavior, as well as making changes as needed along the way. To learn more about AAP recommendations for the treatment of children with ADHD, visit the Recommendations page.

Behavior Therapy, Including Training for Parents

ADHD affects not only a child’s ability to pay attention or sit still at school, it also affects relationships with family and other children. Children with ADHD often show behaviors that can be very disruptive to others. Behavior therapy is a treatment option that can help reduce these behaviors; it is often helpful to start behavior therapy as soon as a diagnosis is made.

The goals of behavior therapy are to learn or strengthen positive behaviors and eliminate unwanted or problem behaviors. Behavior therapy for ADHD can include

Behavior therapy for ADHD can include

- Parent training in behavior management;

- Behavior therapy with children; and

- Behavioral interventions in the classroom.

These approaches can also be used together. For children who attend early childhood programs, it is usually most effective if parents and educators work together to help the child.

Children younger than 6 years of age

For young children with ADHD, behavior therapy is an important first step before trying medication because:

- Parent training in behavior management gives parents the skills and strategies to help their child.

- Parent training in behavior management has been shown to work as well as medication for ADHD in young children.

- Young children have more side effects from ADHD medications than older children.

- The long-term effects of ADHD medications on young children have not been well-studied.

Behavior Therapy for Younger and Older Children with ADHD [PDF – 466 KB]

School-age children and adolescents

For children ages 6 years and older, AAP recommends combining medication treatment with behavior therapy. Several types of behavior therapies are effective, including:

Several types of behavior therapies are effective, including:

- Parent training in behavior management;

- Behavioral interventions in the classroom;

- Peer interventions that focus on behavior; and

- Organizational skills training.

These approaches are often most effective if they are used together, depending on the needs of the individual child and the family.

Learn more about behavior therapy

Learn more about ADHD treatment and support in school

Read about the evidence for effective therapies for ADHD

Top of Page

Medications

Medication can help children manage their ADHD symptoms in their everyday life and can help them control the behaviors that cause difficulties with family, friends, and at school.

Several different types of medications are FDA-approved to treat ADHD in children as young as 6 years of age:

- Stimulants are the best-known and most widely used ADHD medications.

Between 70-80% of children with ADHD have fewer ADHD symptoms when taking these fast-acting medications.

Between 70-80% of children with ADHD have fewer ADHD symptoms when taking these fast-acting medications. - Nonstimulants were approved for the treatment of ADHD in 2003. They do not work as quickly as stimulants, but their effect can last up to 24 hours.

Medications can affect children differently and can have side effects such as decreased appetite or sleep problems. One child may respond well to one medication, but not to another.

Healthcare providers who prescribe medication may need to try different medications and doses. The AAP recommends that healthcare providers observe and adjust the dose of medication to find the right balance between benefits and side effects. It is important for parents to work with their child’s healthcare providers to find the medication that works best for their child.

Top of Page

Parent Education and Support

CDC funds the National Resource Center on ADHD (NRC), a program of Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD). The NRC provides resources, information, and advice for parents on how to help their child. Learn more about the services of the NRC.

The NRC provides resources, information, and advice for parents on how to help their child. Learn more about the services of the NRC.

Tips for Parents

The following are suggestions that may help with your child’s behavior:

- Create a routine. Try to follow the same schedule every day, from wake-up time to bedtime.

- Get organized. Encourage your child to put schoolbags, clothing, and toys in the same place every day so that they will be less likely to lose them.

- Manage distractions. Turn off the TV, limit noise, and provide a clean workspace when your child is doing homework. Some children with ADHD learn well if they are moving or listening to background music. Watch your child and see what works.

- Limit choices. To help your child not feel overwhelmed or overstimulated, offer choices with only a few options. For example, have them choose between this outfit or that one, this meal or that one, or this toy or that one.

- Be clear and specific when you talk with your child. Let your child know you are listening by describing what you heard them say. Use clear, brief directions when they need to do something.

- Help your child plan. Break down complicated tasks into simpler, shorter steps. For long tasks, starting early and taking breaks may help limit stress.

- Use goals and praise or other rewards. Use a chart to list goals and track positive behaviors, then let your child know they have done well by telling them or by rewarding their efforts in other ways. Be sure the goals are realistic—small steps are important!

- Discipline effectively. Instead of scolding, yelling, or spanking, use effective directions, time-outs or removal of privileges as consequences for inappropriate behavior.

- Create positive opportunities. Children with ADHD may find certain situations stressful. Finding out and encouraging what your child does well—whether it’s school, sports, art, music, or play—can help create positive experiences.

- Provide a healthy lifestyle. Nutritious food, lots of physical activity, and sufficient sleep are important; they can help keep ADHD symptoms from getting worse.

Top of Page

ADHD in Adults

ADHD lasts into adulthood for at least one-third of children with ADHD1. Treatments for adults can include medication, psychotherapy, education or training, or a combination of treatments. For more information about diagnosis and treatment throughout the lifespan, please visit the websites of the National Resource Center on ADHD and the National Institutes of Mental Health

More information

For more information on treatments, please click one of the following links:

National Resource Center on ADHD

National Institute of Mental Health

Information for parents from the American Academy of Pediatrics

References:

- Barbaresi WJ, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Voigt RG, Killian JM, Katusic SK. Mortality, ADHD, and psychosocial adversity in adults with childhood ADHD: A prospective study.

Pediatrics 2013;131(4):637-644.

Pediatrics 2013;131(4):637-644.

Parents typically attend 8-16 sessions with a therapist and learn strategies to help their child. Sessions may involve groups or individual families.

- The therapist meets regularly with the family to monitor progress and provide support

- Between sessions, parents practice using the skills they’ve learned from the therapist

After therapy ends families continue to experience improved behavior and reduced stress.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children | Zinov'eva

1. Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–8. DOI:

2. Bryazgunov IP, Kasatikova EV. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. Moscow: Medpraktika; 2002. 128 p. [Bryazgunov IP, Kasatikova EV. Defitsit vnimaniya s giperaktivnost'yu u detei [Deficiency of attention with a hyperactivity at children]. Moscow: Medpraktika; 2002. 128 p. (In Russ.)]

Defitsit vnimaniya s giperaktivnost'yu u detei [Deficiency of attention with a hyperactivity at children]. Moscow: Medpraktika; 2002. 128 p. (In Russ.)]

3. Zavadenko NN. Hyperactivity and attention deficit in childhood. Moscow: ACADEMIA; 2005. 256 p. [Zavadenko N.N. Giperaktivnost' i defitsit vnimaniya v detskom vozraste [Hyperactivity and deficiency of attention at children's age]. Moscow: ACADEMIA; 2005. 256 p. (In Russ.)]

4. Biederman J, Kwon A, Aleardi M, et al. Absence of gender effects on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: findings in nonreferred subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1083–9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1083.

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed.: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

6. Aleksandrov AA, Karpina NV, Stankevich LN. Negativity of mismatch in evoked potentials of the brain in adolescents in the norm and with attention deficit upon presentation of acoustic stimuli of short duration. Russian Physiological Journal. THEM. Sechenov. 2003;33(7):671–5. [Aleksandrov AA, Karpina NV, Stankevich LN. Mismatch negativity in evoked brain potentials in adolescents in normal conditions and attention deficit in response to presentation of short-duration acoustic stimuli. Rossiiskii fiziologicheskii zhurnal im. I.M. Sechenova = Neuroscience and behavioral physiology. 2003;33(7):671–5. (In Russ.)]

Russian Physiological Journal. THEM. Sechenov. 2003;33(7):671–5. [Aleksandrov AA, Karpina NV, Stankevich LN. Mismatch negativity in evoked brain potentials in adolescents in normal conditions and attention deficit in response to presentation of short-duration acoustic stimuli. Rossiiskii fiziologicheskii zhurnal im. I.M. Sechenova = Neuroscience and behavioral physiology. 2003;33(7):671–5. (In Russ.)]

7. Becker SP, Langberg JM, Vaughn AJ, Epstein JN. Clinical utility of the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic parent rating scale comorbidity screening scales. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33(3):221–8. DOI: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318245615b.

8. Gorbachevskaya NL, Zavadenko NN, Sorokin AB, Grigorieva NV. Neurophysiological study of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Siberian Bulletin of Psychiatry and Narcology. 2003;(1):47–51. [Gorbachevskaya NL, Zavadenko NN, Sorokin AB, Grigor'eva NV. Neurophysiological research of a syndrome of deficiency of attention with a hyperactivity. Sibirskii vestnik psikhiatrii i narkologii. 2003;(1):47–51. (In Russ.)]

2003;(1):47–51. (In Russ.)]

9. Biederman J, Faraone S. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2005;366(9481):237–48. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66915-2.

10. Mick E, Faraone SV. Genetics of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17(2):261–84, vii-viii. DOI: 10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.011.

11. Haavik J, Blau N, Thö ny B. Mutations in human monoamine-related neurotransmitter pathway genes. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(7):891–902. DOI: 10.1002/humu.20700.

12. Schulz KP, Himelstein J, Halperin JM, Newcorn JH. Neurobiological models of attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder: a brief review of the empirical evidence. CNS spectra. 2000;5(6):34–44.

13. Arnsten AFT, Pliszka SR. Catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical function: relevance to treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and related disorders. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99(2):211–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.01.020. Epub 2011 Feb 2.

Epub 2011 Feb 2.

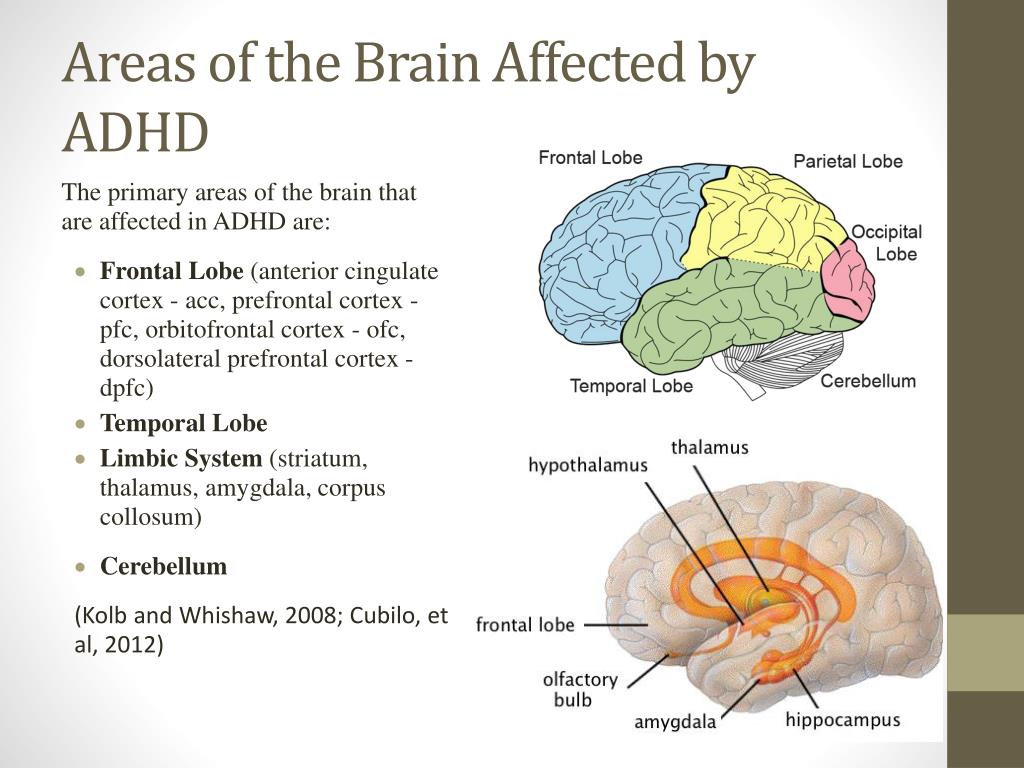

14. McNally MA, Crocetti D, Mahone EM, et al. Corpus callosum segment circumference is associated with response control in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). J Child Neurology. 2010;25(4):453–62. DOI: 10.1177/0883073809350221. Epub 2010 Feb 5.

15. Nakao T, Radua J, Rubia K, Mataix-Cols D. Gray matter volume abnormalities in ADHD: voxelbased meta-analysis exploring the effects of age and stimulant medication. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(11):1154–63. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020281. Epub 2011 Aug 24.

16. Valera EM, Faraone SV, Murray KE, Seidman LJ. Meta-analysis of structural imaging findings in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(12):1361–9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.011. Epub 2006 Sep 1.

17. Finger AB. Lectures on developmental neurology. Moscow: MEDpressinform; 2012. 376 p. [Pal'chik AB. Lektsii po nevrologii razvitiya [Lectures on development neurology]. Moscow: MEDprecsinform; 2012. 376 p. (In Russ.)]

Moscow: MEDprecsinform; 2012. 376 p. (In Russ.)]

18. Reddy DS. Neurosteroids: Endogenous role in the human brian and therapeutic potentials. Prog. Brain Res. 2010;186:113–137.

19. Shaw P, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(49):19649–54. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707741104. Epub 2007 Nov 16.

20. Fair DA, Posner J, Nagel BJ, et al. Atypical default network connectivity in youth with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychology. 2010;68(12):1084–91. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.003. Epub 2010 Aug 21.

21. Makris N, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Seidman LJ. Towards Conceptualizing a Neural Systems-Based Anatomy of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Dev Neurosci. 2009;31(1–2):36–49. DOI: 10.1159/000207492. Epub 2009 Apr 17.

22. Kaplan RF, Stevens MC. A review of adult ADHD: a neuropsychological and neuroimaging perspective. CNS Spectrums. 2002;7(5):355–62.

CNS Spectrums. 2002;7(5):355–62.

23. Krause J. SPECT and PET of the dopamine transporter in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(4):611–25. DOI: 10.1586/14737175.8.4.611.

24. Zametkin A, Liebenauer L, Fitzgerald G, et al. Brain metabolism in teenagers with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:333–40. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820170011002.

25. Arns M, Conners CK, Kraemer HC. A decade of EEG Theta/Beta ratio research in ADHD – a meta-analysis. J Atten Discord. 2013;17(5):374–83. DOI: 10.1177/1087054712460087. Epub 2012 Oct 19.

26. Anjana Y, Khaliq F, Vaney N. Event-related potentials study in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Funct Neurol. 2010;25(2):87–92.

27. Oades RD, Dittman-Balcar A, Schepker R, et al. Auditory event-related potentials (ERPs) and mismatch negativity (MMN) in healthy children and those with attention-deficit or tourettetic symptoms. Biol Psychol. 1996;43(2):163–85. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0301-0511(96)05189-7.

Biol Psychol. 1996;43(2):163–85. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0301-0511(96)05189-7.

28. Meisel V, Servera M, Garcia-Banda G, et al. Neurofeedback and standard pharmacological intervention in ADHD: a randomized controlled trial with six-month follow-up. Biol Psychol. 2013;94(1):12–21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.04.015.

29. Wilens T, Spencer T, Biederman J. A large, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of methylphenidate in the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57(5):456–63. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.043.

30. Lee SS, Humphreys KL, Flory K. Prospective association of childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and substance use and abuse/dependence: a meta-analytic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2011;31(3):328–41. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.006.

31. Hammerness P, McCarthy K, Mancuso E, et al. Atomoxetine for the treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a review. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:215–26. Epub 2009Apr 8.

Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:215–26. Epub 2009Apr 8.

32. Sangal RB, Sangal JM. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: using P300 topography to choose optimal treatment. Expert Rev Neurother. 2006;6(10):1429–37. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1586/14737175.6.10.1429.

Attention Deficit Disorder: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment

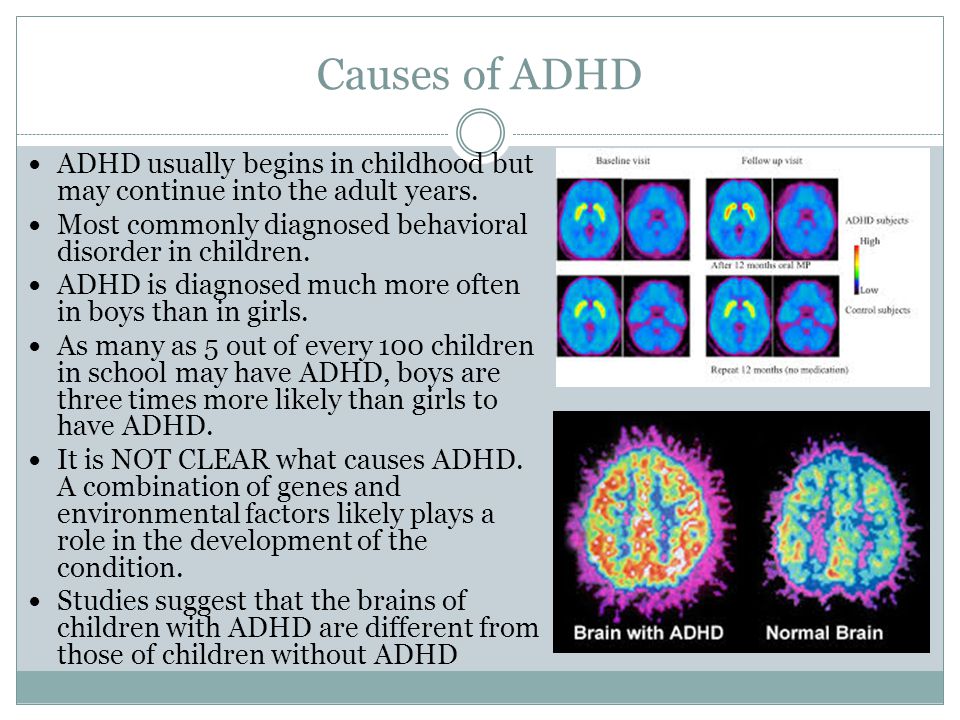

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (abbreviated as ADHD) are certain disorders in the psycho-emotional development of a child. The first symptoms begin to bother from the age of three: the baby cannot sit still and tries in every possible way to attract attention to himself by deliberate disobedience.

Many parents do not consider it necessary to deal with hyperactivity in children, attributing bad behavior to a difficult age. However, in the future, the disease turns into serious problems for the student: inability to concentrate, poor progress, frequent criticism from teachers and friends, social isolation, and nervous breakdowns.

Hyperactivity is a dysfunction of the central nervous system. If left untreated in childhood, the disorder can greatly affect the quality of life of an adult. Therefore, it is worth seeking the advice of a specialist and conducting a comprehensive corrective therapy if you suspect a child has ADHD.

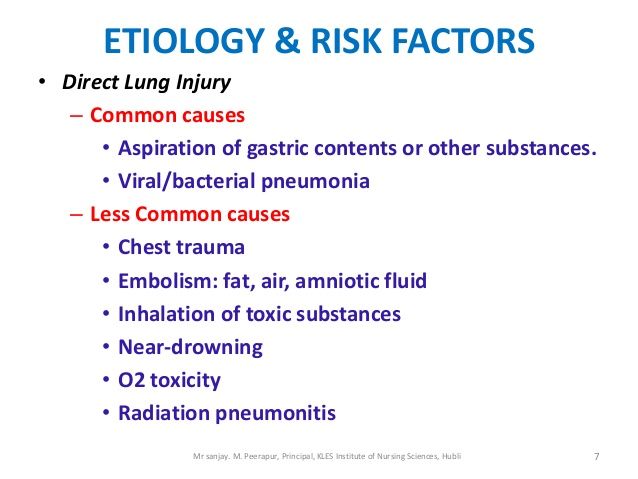

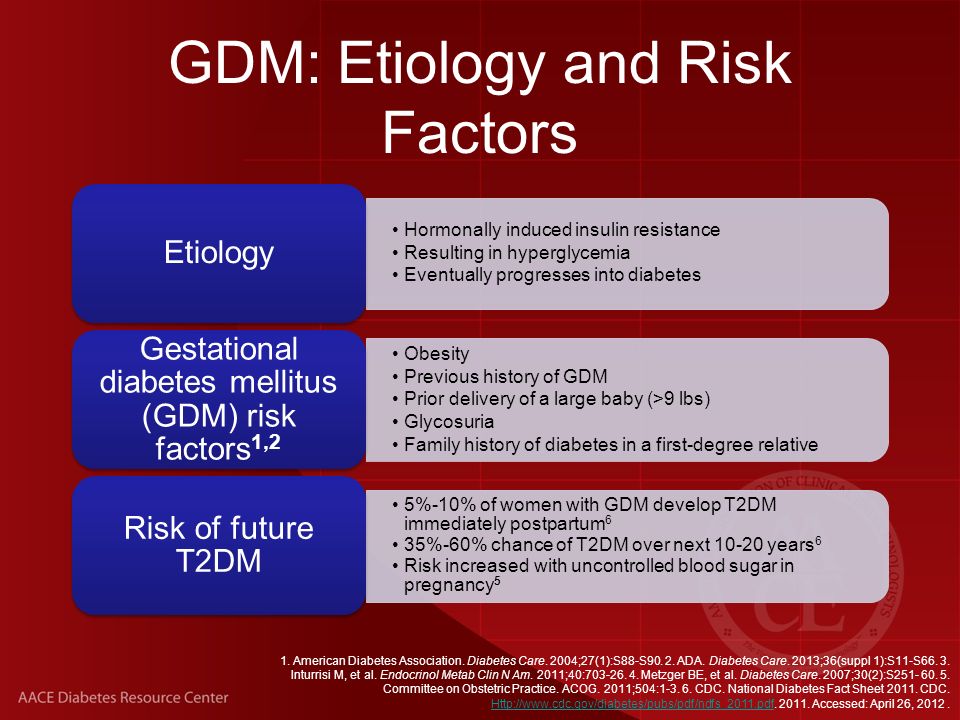

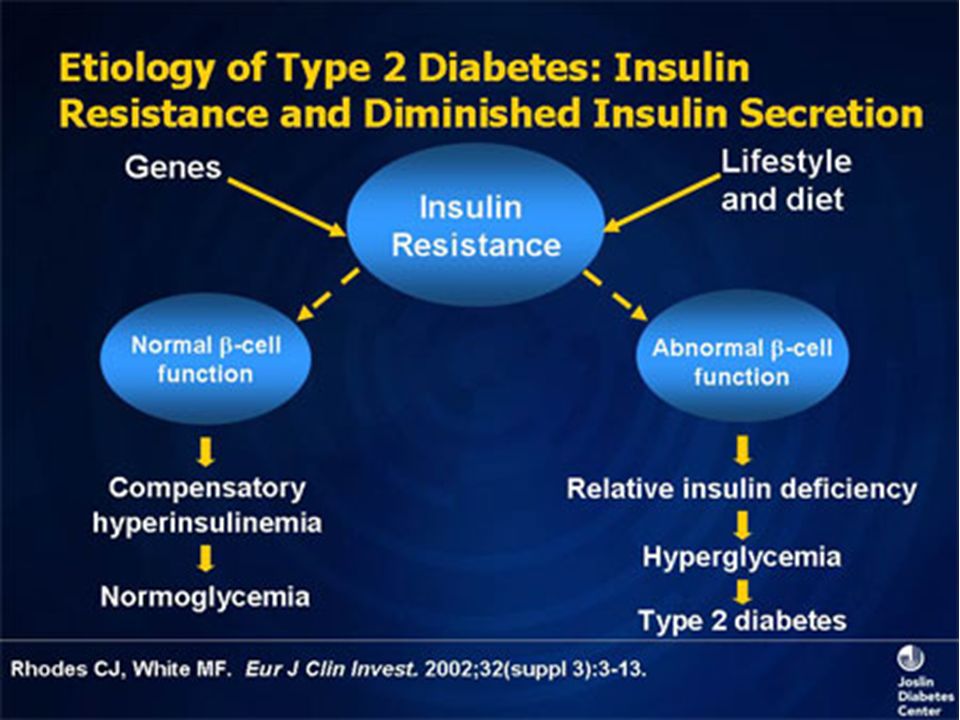

The development of ADHD is hidden in several reasons that have been established by scientists on the basis of facts. These reasons include: genetic predisposition; pathological influence.

Genetic predisposition is the first factor that does not exclude the development of malaise in the patient's relatives. Moreover, in this case, both distant heredity (i.e., the disease was diagnosed in ancestors) and near (parents, grandparents) play a huge role. The first signs of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a child lead caring parents to a medical institution, where it turns out that the predisposition to the disease in a child is associated precisely with genes. After examining the parents, it often becomes clear where this syndrome came from in the child, since in 50% of cases this is exactly the case. Today it is known that scientists are working on isolating the genes that are responsible for this predisposition. Among these genes, an important role is given to DNA regions that control the regulation of dopamine levels. Dopamine is the main substance responsible for the correct functioning of the central nervous system. Dysregulation of dopamine due to genetic predisposition leads to the disease of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pathological influence is of considerable importance in answering the question about the causes of the manifestation of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pathological factors can serve as: the negative impact of narcotic substances; influence of tobacco and alcoholic products; premature or prolonged labor; interrupt threats. If a woman allowed herself to use illegal substances during pregnancy, then the possibility of having a child with hyperactivity or this syndrome is not excluded. There is a high probability of the presence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a child born at 7–8 months of pregnancy, i.

Today it is known that scientists are working on isolating the genes that are responsible for this predisposition. Among these genes, an important role is given to DNA regions that control the regulation of dopamine levels. Dopamine is the main substance responsible for the correct functioning of the central nervous system. Dysregulation of dopamine due to genetic predisposition leads to the disease of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pathological influence is of considerable importance in answering the question about the causes of the manifestation of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pathological factors can serve as: the negative impact of narcotic substances; influence of tobacco and alcoholic products; premature or prolonged labor; interrupt threats. If a woman allowed herself to use illegal substances during pregnancy, then the possibility of having a child with hyperactivity or this syndrome is not excluded. There is a high probability of the presence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in a child born at 7–8 months of pregnancy, i. e. premature.

e. premature.

Symptoms

Attention deficit disorder is expressed primarily in hyperactivity and inattention of the child. These are the main symptoms of the disorder.

Signs of hyperactivity:

- A constant feeling of internal restlessness causes the child to fidget in the chair, jerk his legs, wave his arms or fiddle with something.

- Feelings of anxiety increase when adults are forced to be quiet and calm. This causes a backlash: the children respond to the request not to make noise with stormy laughter, stomping or jumping up from their seats.

- Hyperactivity is expressed in impulsive behavior. For example, a child shouts out an answer in class before the teacher has finished speaking the question. Or he may get into a fight because he is unable to wait his turn in the game competitions.

- The inattention inherent in hyperactivity syndrome is expressed as follows:

- Any task tires very quickly, just a couple of minutes after the start.

It is almost impossible to focus on learning a new subject. Usually children are able to keep their attention on what they are really interested in. But in a child with ADHD, boredom and an absent-minded look appear in any activity, even in the one with which he “fired up” in the first minutes.

It is almost impossible to focus on learning a new subject. Usually children are able to keep their attention on what they are really interested in. But in a child with ADHD, boredom and an absent-minded look appear in any activity, even in the one with which he “fired up” in the first minutes. - Problems with concentration develop absent-mindedness. Sitting down for homework in the language, the child opens a math notebook and does not notice that he is writing the text on a sheet in a cage. He forgets to write down information in a diary, he may forget his textbook and notebooks on his desk, or he may not hear a request addressed to him.

- There is a very poor memory. Trying to learn something by heart, a child can repeat a phrase twenty times and not reproduce it after a minute. This happens due to constant distractibility: children mechanically pronounce the words they are learning, but mentally follow the crawling fly on the wall or listen to the sounds from the street.

Diagnosis

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is diagnosed using a questionnaire, behavioral observation of the child, and an MRI brain examination.

Asking questions to parents, the medical specialist builds a clinical picture, differentiating normal behavioral symptoms from actual abnormalities, in order to accurately determine whether it is ADHD or normal puberty.

Frontal brain scan serves both to investigate attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and to confirm the diagnosis.

Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

The best treatment option for ADHD is a complex - psychological correction in combination with medications.

A lot depends on the actions of mothers and fathers. Do not constantly scold the baby for wrong actions and inappropriate behavior. It is much more useful to offer your help in cleaning things or preparing for school, to praise for the diligence shown and overcoming difficulties.