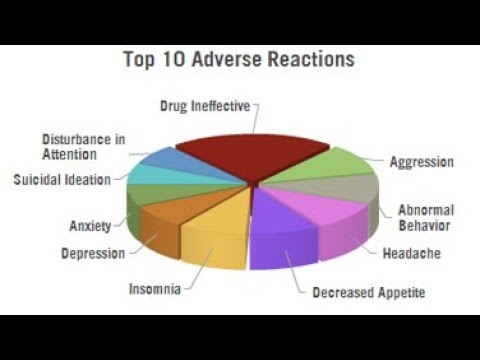

Ritalin emotional side effects

Effects of Ritalin on the Body

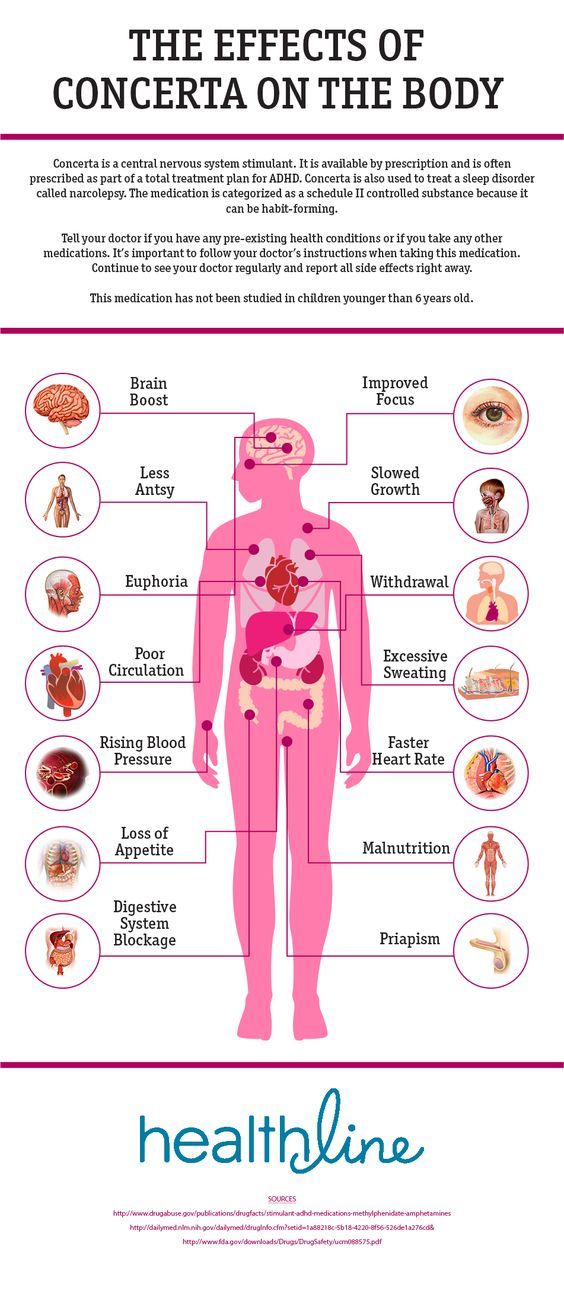

Ritalin is one of the common treatment options used for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Although this stimulant can improve symptoms of ADHD, it can also cause some side effects. Ritalin can be misused, and that comes with the risk of more serious side effects throughout the body. It should only be used with medical supervision.

When you first start taking Ritalin for ADHD, the side effects are usually temporary. See your doctor if any symptoms worsen or last beyond a few days.

Find out more about the various symptoms and side effects that you might be at risk for while using Ritalin.

Ritalin (methylphenidate) is a nervous system stimulant that’s commonly used to treat ADHD in adults and children.

It’s a brand-name prescription medication that targets dopamine and norepinephrine in the brain to reduce common ADHD symptoms.

Though Ritalin is a stimulant, when used in ADHD treatment, it may help with concentration, fidgeting, attention, and listening skills.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), about 6.1 million U.S. children ages 2 to 17 (or 9.4 percent of children) were diagnosed with ADHD as of 2016.

Ritalin is just one form of treatment for ADHD. It’s often complemented with behavioral therapy.

Ritalin is sometimes used to treat narcolepsy, a sleep disorder.

As with all stimulants, this medication is a federally controlled substance. It can be misused, which comes with the risk of serious side effects.

Ritalin should only be used with medical supervision. Your doctor will likely see you every few months to make sure the medication is working as it should.

Even if you take Ritalin correctly and don’t misuse it, it can carry the risk for side effects.

Ritalin influences both dopamine and norepinephrine activity in your brain.

Dopamine is a neurotransmitter that affects pleasure, movement, and attention span. Norepinephrine is a stimulant.

Ritalin increases the action of these neurotransmitters by blocking their reabsorption into your brain’s neurons. The levels of these chemicals increase slowly, so your doctor will start you on the lowest possible dose and increase it in small increments, if necessary.

The levels of these chemicals increase slowly, so your doctor will start you on the lowest possible dose and increase it in small increments, if necessary.

Ritalin may make it easier for you to concentrate, be less fidgety, and gain control of your actions. You may also find it easier to listen and focus at your job or in school.

If you’re already prone to anxiety or agitation, or have an existing psychotic disorder, Ritalin may worsen these symptoms.

If you have a history of seizures, this medication may cause more seizures.

Some people taking Ritalin experience blurred vision or other changes to eyesight. Other potential side effects include:

- headache

- trouble sleeping

- irritability

- moodiness

- nervousness

- increased blood pressure

- racing heartbeat, in rare cases

This medication can temporarily slow a child’s growth, especially in the first two years of taking it. That’s why your child’s doctor will keep an eye on their height.

Your child’s doctor may suggest taking a break from the medication. This is often done during the summer months. This can encourage growth, and also allows them to see how your child does without taking it.

Ritalin, like other central nervous system stimulants, may be habit-forming. If you take a large dose, the quick rise in dopamine can produce a temporary feeling of euphoria.

Taking Ritalin in high doses or for a long time can be habit-forming. If you stop taking it abruptly, you may experience withdrawal.

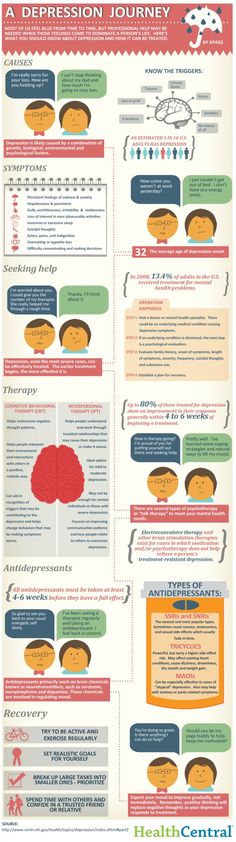

Symptoms of withdrawal include sleep problems, fatigue, and depression. It’s better to taper off slowly and under a doctor’s care.

When misused, stimulants like Ritalin can cause feelings of paranoia and hostility.

Very high doses can lead to:

- shakiness or severe twitching

- mood changes

- confusion

- delusions or hallucinations

- seizures

If you have any of these symptoms, seek medical attention immediately.

Ritalin can cause circulation problems. Your fingers and toes may feel cold and painful, and your skin may turn blue or red.

Use of Ritalin is linked to peripheral vascular disease, including Raynaud’s disease. If you take Ritalin and experience circulatory problems, tell your doctor.

Stimulants can also raise your body temperature, blood pressure, and heart rate. You may feel jittery and irritable. That’s usually not a problem in the short term, but you should have regular exams to check your heart rate and blood pressure.

Stimulants should be taken with caution if you have pre-existing blood pressure or heart problems. Ritalin may increase your risk of heart attack and stroke.

Rare cases of sudden death have occurred in people who have structural heart abnormalities.

Misusing stimulants by crushing pills and injecting them can lead to blocked blood vessels. An overdose can lead to dangerously high blood pressure or irregular heartbeat.

High doses can also lead to life-threatening complications such as heart failure, seizures, and significantly high body temperature.

Ritalin can reduce appetite in some people. Other side effects include stomachache and nausea.

Misusing this drug can also cause vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea.

Over time, misuse of Ritalin can lead to malnutrition and related health problems. It may also lead unintentional weight loss.

When taken as prescribed, Ritalin doesn’t generally cause a problem with the respiratory system.

At first, though, Ritalin can increase your breathing slightly and also open up your airways. Such effects are temporary and will go away after a few days once your body gets used to a new prescription or dosage.

However, very high doses or long-term misuse can cause irregular breathing. Breathing problems should always be considered a medical emergency.

When you first start taking Ritalin, you might experience improved mood, and almost a sense of euphoria. This can translate to everyday physical activities being easier to accomplish.

In the long term, Ritalin can cause musculoskeletal complications when misused or taken in too large of doses.

Such cases can lead to muscle pain and weakness, as well as joint pain.

Males who take Ritalin may experience painful and prolonged erections. When this occurs, it’s usually after prolonged Ritalin use, or after your dose was increased.

It’s rare, but it sometimes requires medical intervention.

Changes in behavior as side effects in methylphenidate treatment: review of the literature

1. Britton GB. Cognitive and emotional behavioral changes associated with methylphenidate treatment: a review of preclinical studies. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(1):41–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Carlezon WA, Mague SD, Andersen SL. Enduring behavioral effects of early exposure to methylphenidate in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(12):1330–1337. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Bolaños CA, Barrot M, Berton O, Wallace-Black D, Nestler EJ. Methylphenidate treatment during pre- and periadolescence alters behavioral responses to emotional stimuli at adulthood. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(12):1317–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54(12):1317–1329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, et al. Dopamine transporter occupancies in the human brain induced by therapeutic doses of oral methylphenidate. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(10):1325–1331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Wang GJ, Volkow ND, Wigal T, et al. Long-term stimulant treatment affects brain dopamine transporter level in patients with attention deficit hyperactive disorder. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Advokat C. What are the cognitive effects of stimulant medications? Emphasis on adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2010;34(8):1256–1266. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Storebø OJ, Ramstad E, Krogh HB, et al. Methylphenidate for children and adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;11:CD009885. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Reiche D. Roche Lexikon Medizin [Medical Encyclopedia] 4th ed. Munich: Urban & Fischer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

Roche Lexikon Medizin [Medical Encyclopedia] 4th ed. Munich: Urban & Fischer; 2003. [Google Scholar]

9. Challman T, Lipsky JJ. Methylphenidate: its pharmacology and uses. Mayo Clin Proc. 2000;75(7):711–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Kuczenski R, Segal D. Effects of methylphenidate on extracellular dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine: comparison with amphetamine. J Neurochem. 1997;68(5):2032–2037. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Gatley SJ, Pan D, Chen R, Chaturvedi G, Ding YS. Affinities of methylphenidate derivatives for dopamine, norepinephrine and serotonin transporters. Life Sci. 1996;58(12):231–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Gray JD, Punsoni M, Tabori NE, et al. Methylphenidate administration to juvenile rats alters brain areas involved in cognition, motivated behaviors, appetite, and stress. J Neurosci. 2007;27(27):7196–7207. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Germany Federal Ministry of Health . Bekanntmachung eines Beschlusses des Gemeinsamen Bundesausschusses über eine Änderung der Arzneimittel-Richtlinie [Declaration of a resolution of the Federal Joint Committee about a modification of the guideline for medicine] Berlin: Bundesministerium für Gesundheit; 2010. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

14. Silva RR, Muniz R, Pestreich L, et al. Efficacy and duration of effect of extended-release dexmethylphenidate versus placebo in schoolchildren with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(3):239–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Bron TI, Bijlenga D, Boonstra AM, et al. OROS-methylphenidate efficacy on specific executive functioning deficits in adults with ADHD: a randomized, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(4):519–528. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Ghuman JK, Ginsburg GS, Subramaniam G, Human HS, Kau AS, Riddle MA. Psychostimulants in preschool children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: clinical evidence from a developmental disorders institution. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(5):516–524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Maayan L, Paykina N, Fried J, Strauss T, Gugga SS, Greenhill L. The open-label treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in 4- and 5-year-old children with beaded methylphenidate. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(2):147–153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(2):147–153. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Leibson CL, Jacobsen SJ. Long-term stimulant medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from a population-based study. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Smith G, Jongeling B, Hartmann P. Raine ADHD Study: Long-Term Outcomes Associated with Stimulant Medication in the Treatment of ADHD in Children. Perth: Government of Western Australia Department of Health; 2010. [Google Scholar]

20. Aagaard L, Hansen EH. The occurrence of adverse drug reactions reported for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications in the pediatric population: a qualitative review of empirical studies. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2011;7:729–744. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Biederman J, Quinn D, Weiss M, et al. Efficacy and safety of Ritalin LA, a new, once daily, extended-release dosage form of methylphenidate, in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Paediatr Drugs. 2003;5(12):833–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Paediatr Drugs. 2003;5(12):833–841. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Arabgol F, Panaghi L, Hebrani P. Reboxetine versus methylphenidate in treatment of children and adolescents with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;18(1):53–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Amiri S, Mohammadi MR, Mohammadi M, Neuroozinejad GH, Kahbazi M, Akhondzadeh S. Modafinil as a treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents: a double blind, randomized clinical trial. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32(1):145–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Findling RL, Quinn D, Hatch SJ, Cameron SJ, DeCory HH, McDowell M. Comparison of the clinical efficacy of twice-daily Ritalin and once-daily Equasym XL with placebo in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(8):450–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Newcorn JH, Kratochvil CJ, Allen AJ. Atomoxetine and osmotically released methylphenidate for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: acute comparison and differential response. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(6):721–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(6):721–730. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Greenhill L, Muniz R, Ball RR, Levine A, Pestreich L, Jiang H. Efficacy and safety of dexmethylphenidate extended-release capsules in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(7):817–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Gau SS, Shen HY, Soong WT, Gau CS. An open-label, randomized, active-controlled equivalent trial of osmotic release oral system methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Taiwan. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(4):441–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Kemner JE, Starr HL, Ciccone PE, Hooper-Wood CG, Crockett RS. Outcomes of OROS methylphenidate compared with atomoxetine in children with ADHD: a multicenter, randomized prospective study. Adv Ther. 2005;22(5):498–512. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

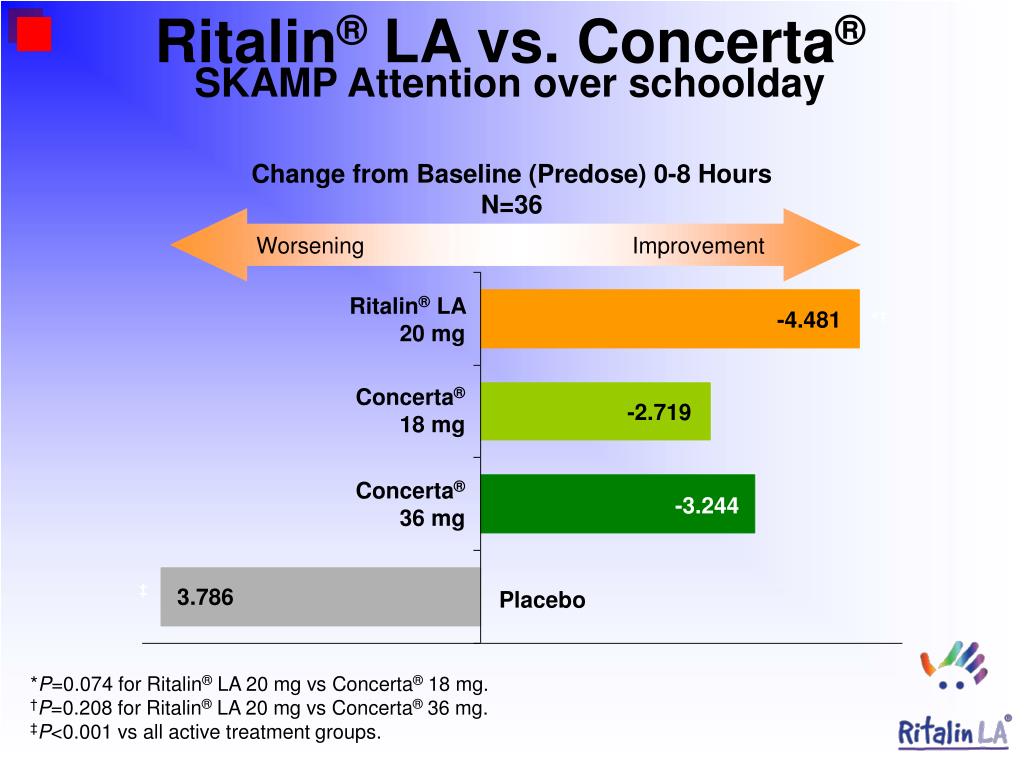

29. Swanson JM, Wigal SB, Wigal T, et al. A comparison of once-daily extended-release methylphenidate formulations in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the laboratory school (the COMACS study) Pediatrics. 2004;113(3 Pt 1):e206–e216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2004;113(3 Pt 1):e206–e216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Kratochvil CJ, Heiligenstein JH, Dittmann R, et al. Atomoxetine and methylphenidate treatment in children with ADHD: a prospective, randomized, open-label trial. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(7):776–784. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Adler LA, Orman C, Starr HL, et al. Long-term safety of OROS methylphenidate in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an open-label, dose-titration, 1-year study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):108–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Buitelaar JK, Ramos-Quiroga A, Casas M, et al. Safety and tolerability of flexible dosages of prolonged-release OROS methylphenidate in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2009;5:457–466. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Casas M, Rösler M, Kooij JJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of prolonged- release OROS methylphenidate in adults with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a 13-week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose study. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14(4):268–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

World J Biol Psychiatry. 2013;14(4):268–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. The MTA Cooperative Group A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(12):1073–1086. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Arnold LE, Howard BA, Cantwell DP, et al. National Institute of Mental Health collaborative multimodal treatment study of children with ADHD (the MTA) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1997;54(9):865–870. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. MTA Cooperative Group National Institute of Mental Health multimodal treatment study of ADHD follow-up: 24-month outcomes of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):754–761. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. MTA Cooperative Group National Institute of Mental Health multimodal treatment study of ADHD follow-up: changes in effectiveness and growth after the end of treatment. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):762–769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Jensen PS, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. 3-Year follow-up of the NIMH MTA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;6(8):989–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Jensen PS, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. 3-Year follow-up of the NIMH MTA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;6(8):989–1002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Molina BS, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, et al. The MTA at 8 years: prospective follow-up of children treated for combined type ADHD in a multisite study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(5):484–500. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Greenhill L, Kollins S, Abikoff H, et al. Efficacy and safety of immediate-release methylphenidate treatment for preschoolers with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1284–1293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Wigal T, Greenhill L, Chuang S, et al. Safety and tolerability of methylphenidate in preschool children with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(11):1294–1303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Riddle MA, Yershova K, Lazzaretto D, et al. The Preschool Attention- Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Treatment Study (PATS) 6-year follow-up. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(3):264–278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2013;52(3):264–278. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Zarinara AR, Mohammadi MR, Hazrati N, et al. Venlafaxine versus methylphenidate in pediatric outpatients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized, double-blind comparison trial. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2010;25(7–8):530–535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Wigal SB, Nordbrock E, Adjei AL, Childress A, Kupper RJ, Greenhill L. Efficacy of methylphenidate hydrochloride extended-release capsules (Aptensio XR) in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a phase III, randomized, double-blind study. CNS Drugs. 2015;29(4):331–340. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Kooij JJ, Burger H, Boonstra AM, Van der Linden PD, Kalma LE, Buitelaar JK. Efficacy and safety of methylphenidate in 45 adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind cross-over trial. Psychol Med. 2004;34(6):973–982. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Barkley RA, McMurray MB, Edelbrock CS, Robbins K. Side effects of methylphenidate in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a systemic-placebo-controlled evaluation. Pediatrics. 1990;86(2):184–192. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Efron D, Jarman F, Barker M. Side effects of methylphenidate and dexamphetamine in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a double-blind, crossover trial. Pediatrics. 1997;100(4):662–666. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Lee J, Grizenko N, Bhat V, Sengputa S, Polotskaia A, Joober R. Relation between therapeutic response and side effects induced by methylphenidate as observed by parents and teachers of children with ADHD. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Pelham WE, Gnagy EM, Burrows-Maclean L, et al. Once-a-day Concerta methylphenidate versus three-times-daily methylphenidate in laboratory and natural settings. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):E105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Stein MA, Sarampote CS, Waldman ID, et al. A dose-response study of OROS methylphenidate in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2003;112(5):e404–e413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Adler LA, Spencer T, McGough JJ, Jiang H, Muniz R. Long-term effectiveness and safety of dexmethylphenidate extended-release capsules in adult ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2009;12(5):449–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Bejerot S, Rydén EM, Arlinde CM. Two-year outcome of treatment with central stimulant medication in adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a prospective study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(12):1590–1597. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Fredriksen M, Dahl AA, Martinsen EW, Klungsoyr O, Haavik J, Peleikis DE. Effectiveness of one-year pharmacological treatment of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): an open-label prospective study of time in treatment, dose, side-effects and comorbidity. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2014;24(12):1873–1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2014;24(12):1873–1884. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Huss M, Ginsberg Y, Tvedten T, et al. Methylphenidate hydrochloride modified-release in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Adv Ther. 2014;31(1):44–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Huss M, Ginsberg Y, Arngrim T, et al. Open-label dose optimization of methylphenidate modified release long acting (MPH-LA): a post hoc analysis of real-life titration from a 40-week randomized trial. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34(9):639–649. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Döpfner M, Görtz-Dorten A, Breuer D, Rothenberger A. An observational study of once-daily modified release methylphenidate in ADHD: effectiveness on symptoms and impairment, and safety. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2011;20(2):243–255. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Garg J, Arun P, Chavan BS. Comparative short term efficacy and tolerability of methylphenidate and atomoxetine in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Indian Pediatr. 2014;51(7):550–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Indian Pediatr. 2014;51(7):550–554. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Haertling F, Mueller B, Bilke-Hentsch O. Effectiveness and safety of a long-acting, once-daily, two-phase release formulation of methylphenidate (Ritalin LA) in school children under daily practice conditions. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2015;7(2):157–164. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Karabekiroglu K, Yazgan YM, Dedeoglu C. Can we predict short-term side effects of methylphenidate immediate-release? Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2008;12(1):48–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Khajehpiri Z, Mahmoudi-Gharaei J, Faghihi T, Karimzadeh I, Khalili H, Mohammadi M. Adverse reactions of methylphenidate in children with attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder: report from a referral center. J Res Pharm Pract. 2015;3(4):130–136. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Robb AS, Findling RL, Childress AC, Berry SA, Belden HW, Wigal SB. Efficacy, safety, and tolerability of a novel methylphenidate extended-release oral suspension (MEROS) in ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2014 May 29; Epub. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Atten Disord. 2014 May 29; Epub. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Valdizán-Usón JR, Cánovas-Martínez A, De Lucas-Taracena MT, et al. A response to methylphenidate by adult and pediatric patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: the Spanish multicenter DIHANA study. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2013;9:211–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Cherland E, Fitzpatrick R. Psychotic side effects of psychostimulants: a 5-year review. Can J Psychiatry. 1999;44(8):811–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Ramtvedt BE, Aabech HS, Sundet K. Minimizing adverse events while maintaining clinical improvement in a pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder crossover trial with dextroamphetamine and methylphenidate. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2014;24(3):130–139. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Buitelaar JK, Trott GE, Hofecker M, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety outcomes with OROS-MPH in adults with ADHD. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;15(1):1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2012;15(1):1–13. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Steele M, Weiss M, Swanson J, Wang J, Prinzo RS, Binder CE. A randomized, controlled, effectiveness trial of OROS-methylphenidate compared to usual care with immediate-release methylphenidate in attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. Can J Clin Pharmacol. 2006;13(1):e50–e62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Inglis SK, Carucci S, Garas P, et al. Prospective observational study protocol to investigate long-term adverse effects of methylphenidate in children and adolescents with ADHD: the Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder Drugs Use Chronic Effects (ADDUCE) Study. BMJ Open. 2016;6(4):e010433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Methylphenidate (Ritalin). Reference - RIA Novosti, 29.01.2009

https://ria.ru/200/160419471.html

Methylphenidate (Ritalin). Help

Methylphenidate (Ritalin). Reference - RIA Novosti, 29.01.2009

Methylphenidate (Ritalin). Reference

Methylphenidate (Meridil, Centedrin, Ritalin) is an aphrodisiac, non-amphetamine psychostimulant. It can be used for depression of the nervous system caused by antipsychotic drugs, narcolepsy. It is also prescribed to treat attention deficit disorder and depression.

It can be used for depression of the nervous system caused by antipsychotic drugs, narcolepsy. It is also prescribed to treat attention deficit disorder and depression.

2009-01-29T11:05

2009-01-29T11:05

2009-01-29T11:05

/html/head/meta[@name='og:title']/@content

3 /html/head/meta[@name='og:description']/@content

https://cdnn21.img.ria.ru/images/sharing/article/160419471.jpg?1233216326

RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7

9000

7 495 645-6601

FSUE MIA Today

https: //xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1aii/ awards/

2009

RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7

9000

7 495 645-6601

FSUE MIA "Russia Today"

https: // XN --c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/awards/

News

en-RU

https://ria.ru/docs/about/copyright.html

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn-- p1ai/

RIA Novosti

1

5

4. 7

7

96

7 495 645-6601

Rossiya Segodnya

https://xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1 News

1

5

4.7

9000

7 495 645-6601

Federal State Unitary Enterprise “Russia Today”

HTTPS: //xn--C1ACBL2ABDLKAB1OG.XN-G. -p1ai/awards/

RIA Novosti

1

5

4.7

9000

7 495 645-6601

FSUE MIA Today

https: //xn--c1acbl2abdlkab1og.xn--p1ai/AWAWARDS /

Society

Society

All American teenagers who participated in the executions of their peers took Ritalin, but for various reasons they did not receive it on the day of the tragedy, scientists say. The withdrawal syndrome is so strong, experts say, that a teenager who is forgotten to give a dose of medication falls into a deep depression, becomes uncontrollable and aggressive, which has led to many tragedies.

Methylphenidate (Meridil, Centedrin, Ritalin) is an aphrodisiac, non-amphetamine psychostimulant.

In medicine, the drug has limited use as a psychostimulant in asthenic conditions, increased fatigue. It can be used for depression of the nervous system caused by antipsychotic drugs, narcolepsy. It is also prescribed for the treatment of lack of attention, activity disorders, depression.

Methylphenidate was synthesized in 1944. At 19In 1961, physicians from around the United States drew attention to the fact that the new generation of central nervous system stimulant drugs methylphenidate and dextroamphetamine helped children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), but compared to the previously used benzedrine, they caused much less side effects. After that, Ciba Geigy proposed the use of Ritalin (methylphenidate) for the treatment of this disease. The remedy was initially rejected by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), but in 1963 was approved for this indication.

Pharmaceutical tablets are most commonly taken orally or crushed and sniffed as a powder.

Methylphenidate is similar in action to amphetamine, but has a less strong stimulating effect and less effect on the peripheral adrenergic systems; does not cause a pronounced increase in blood pressure. Suppresses appetite, causes wakefulness, euphoria, increases concentration and attentiveness.

Possible side effects: insomnia, nausea, sometimes agitation and anxiety, exacerbation of psychopathological symptoms. Addictive.

Complications arising from the use of methylphenidate are due to the insoluble excipients used in the tablets. When injected, these materials block small blood vessels, causing serious damage to the lungs and retina. Methylphenidate also produces an increase in heart rate and blood pressure due to high doses, and can lead to serious psychological dependence.

According to the Australian Medicines Administration (TGA), Ritalin and dexamphetamine have resulted in 400 serious adverse reactions in children aged three to ten years. In particular, there was a case of sudden death of a seven-year-old child and a stroke in a five-year-old child after the use of Ritalin. Dexamphetamine use has been associated with palpitations and shortness of breath in some cases. In addition, adverse reactions such as hair loss, muscle spasms, severe abdominal pain, tremors, insomnia, severe weight loss, depression and paranoia have been reported.

In particular, there was a case of sudden death of a seven-year-old child and a stroke in a five-year-old child after the use of Ritalin. Dexamphetamine use has been associated with palpitations and shortness of breath in some cases. In addition, adverse reactions such as hair loss, muscle spasms, severe abdominal pain, tremors, insomnia, severe weight loss, depression and paranoia have been reported.

In recent years, the use of Ritalin for the purpose of psychological self-improvement has become widespread. Currently, students have begun to widely consume it, according to which the drug helps to concentrate during pre-examination preparation. What may be the long-term effect of such initiative is still unknown.

According to the US Drug Enforcement Administration, street abuse of methylphenidate has become a major problem in the country. The United States consumes 85% of the total production of methylphenidate (Ritalin).

In 2002, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe noted the high levels of legal consumption of methylphenidate in Belgium, Germany, Iceland, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Switzerland and the United Kingdom.

Methylphenidate is on schedule 1 (psychotropic substances) of the list of narcotic drugs, psychotropic substances and their precursors subject to control in the Russian Federation, and produces pharmacological effects similar to those of cocaine and amphetamine.

The material was prepared on the basis of information from open sources

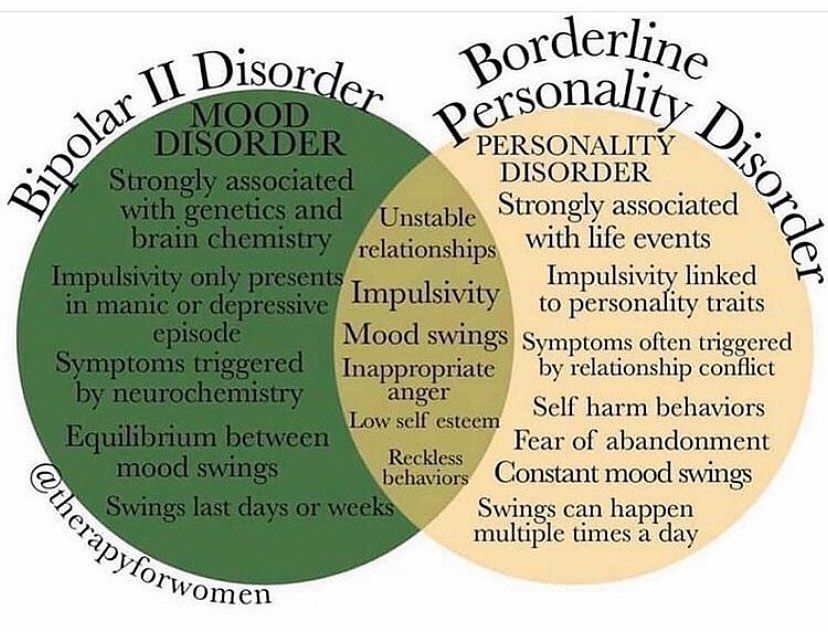

Medicines for mental illness

The effectiveness of drug therapy with psychotropic drugs is determined by the compliance of the choice of the drug with the clinical picture of the disease, the correctness of its dosing regimen, the method of administration and the duration of the therapeutic course. As in any field of medicine, in psychiatry it is necessary to take into account the entire complex of drugs that the patient takes, since their mutual action can lead not only to a change in the nature of the effects of each of them, but also to the occurrence of undesirable consequences.

There are several approaches to the classification of psychotropic drugs. Table 1 shows the classification proposed by the WHO in 1990, adapted to include some domestic medicines.

Table 1 shows the classification proposed by the WHO in 1990, adapted to include some domestic medicines.

Table 1. Classification of psychopharmacological drugs.

| Grade | Chemical group | Generic and common trade names |

| Antipsychotics | Phenothiazines | Chlorpromazine (chlorpromazine), promazine, thioproperazine (majeptil), trifluperazine (stelazine, triftazine), periciazine (neuleptil), alimemazine (teralen) |

| Xanthenes and thioxanthenes | Chlorprothixene, Clopenthixol (Clopexol), Flupentixol (Fluanxol) | |

| Butyrophenones | Haloperidol, trifluperidol (trisedil, triperidol), droperidol | |

| Piperidine derivatives | Fluspirilene (imap), pimozide (orap), penfluridol (semap) | |

| Cyclic derivatives | Risperidone (rispolept), ritanserin, clozapine (leponex, azaleptin) | |

| Indole and naphthol derivatives | Molindol (moban) | |

| Benzamide derivatives | Sulpiride (eglonil), metoclopramide, racloprid, amisulpiride, sultopride, tiapride (tiapridal) | |

| Derivatives of other substances | Olanzapine (Zyprexa) | |

| Tranquilizers | Benzodiazepines | Diazepam (Valium, Seduxen, Relanium), Chlordiazepoxide (Librium, Elenium), Nitrazempam (Radedorm, Eunoctin) |

| Triazolobenzodiazepines | Alprazolam (Xanax), Triazolam (Chalcion), Madizopam (Dormicum) | |

| Heterocyclic | Brotizopam (lendormin) | |

| Diphenylmethane derivatives | Benactizine (staurodorm), hydroxyzine (atarax) | |

| Heterocyclic derivatives | Busperone (buspar), zopiclone (imovan), clometizol, gemineurin, zolpidem (ivadal) | |

| Antidepressants | Tricyclic | Amitriptyline (Triptisol, Elivel), Imipramine (Melipramine), Clomipramine (Anafranil), Tianeptine (Coaxil) |

| Tetracyclic | Mianserin (Lerivon), Maprotiline (Ludiomil), Pyrlindol (Pyrazidol), | |

| Serotonergic | Citalopram (Seroprax), Sertraline (Zoloft), Paroxetine (Paxil), Viloxazine (Vivalan), Fluoxetine (Prozac), Fluvoxamine (Fevarin), | |

| Noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSA) | Mirtazapine (remeron), milnacipran (ixel) | |

| MAO inhibitors (reversible) | Moclobemide (Aurorix) | |

| Nootropics (as well as substances with a nootropic component of action) | Pyrrolidone derivatives | Piracetam (nootropil) |

| Cyclic derivatives, GABA | Pantogam, Phenibut, Gammalon (Aminalone) | |

| Acetylcholine precursors | Deanol (acti-5) | |

| Pyridoxine derivatives | Pyritinol | |

| Devincan derivatives | Vincamine, Vinpocetine (Cavinton) | |

| Neuropeptides | Vasopressin, oxytocin, thyroliberin, cholecystokinin | |

| Antioxidants | Ionol, mexidol, tocopherol | |

| Stimulants | Phenethylamine derivatives | Amphetamine, salbutamol, methamphetamine (Pervitine) |

| Sydnonimine derivatives | Sydnocarb | |

| Heterocyclic | Methylphnidate (Ritalin) | |

| Purine derivatives | Caffeine | |

| Normotimics | Metal salts | Lithium salts (lithium carbonate, lithium hydroxybutyrate, lithonite, micalite), rubidium chloride, cesium chloride |

| Assembly group | Carbamazepine (finlepsin, tegretol), valpromide (depamide), sodium valproate (depakin, convulex) | |

| Additional group | Assembly group | Amino acids (glycine), opium receptor antagonists (naloxone, naltrexone), neuropeptides (bromocriptine, thyroliberin) |

The main clinical characteristics and side effects of the listed classes of pharmacological drugs are given below.

Antipsychotics

Clinical characteristics. This class of drugs is central to the treatment of psychosis. However, the scope of their application is not limited to this, since in small doses in combination with other psychotropic drugs they can be used in the treatment of affective disorders, anxiety-phobic, obsessive-compulsive and somatoform disorders, with decompensation of personality disorders.

Regardless of the characteristics of the chemical structure and mechanism of action, all drugs of this group have similar clinical properties: they have a pronounced antipsychotic effect, reduce psychomotor activity and reduce mental arousal, neurotropic effect, manifested in the development of extrapyramidal and vegetovascular disorders, many of they also have antiemetic properties .

Side effects. The main side effects in the treatment of neuroleptics form the neuroleptic syndrome. The leading clinical manifestations of this syndrome are extrapyramidal disorders with a predominance of either hypo- or hyperkinetic disorders. Hypokinetic disorders include drug-induced parkinsonism, manifested by increased muscle tone, lockjaw, rigidity, stiffness, and slowness of movement and speech. Hyperkinetic disturbances include tremor and hyperkinesis. Usually in the clinical picture in various combinations there are both hypo- and hyperkinetic disorders. The phenomena of dyskinesia can be paroxysmal in nature, localized in the mouth area and manifested by spasmodic contractions of the muscles of the pharynx, tongue, lips, jaws. Often there are phenomena of akathisia - feelings of restlessness, "restlessness in the legs", combined with tasikinesia (the need to move, change position). A special group of dyskinesias includes tardive dyskinesia, which occurs after 2-3 years of taking antipsychotics and is expressed in involuntary movements of the lips, tongue, face.

The leading clinical manifestations of this syndrome are extrapyramidal disorders with a predominance of either hypo- or hyperkinetic disorders. Hypokinetic disorders include drug-induced parkinsonism, manifested by increased muscle tone, lockjaw, rigidity, stiffness, and slowness of movement and speech. Hyperkinetic disturbances include tremor and hyperkinesis. Usually in the clinical picture in various combinations there are both hypo- and hyperkinetic disorders. The phenomena of dyskinesia can be paroxysmal in nature, localized in the mouth area and manifested by spasmodic contractions of the muscles of the pharynx, tongue, lips, jaws. Often there are phenomena of akathisia - feelings of restlessness, "restlessness in the legs", combined with tasikinesia (the need to move, change position). A special group of dyskinesias includes tardive dyskinesia, which occurs after 2-3 years of taking antipsychotics and is expressed in involuntary movements of the lips, tongue, face.

Among the disorders of the autonomic nervous system, orthostatic hypotension, sweating, weight gain, changes in appetite, constipation, diarrhea are most often observed. Sometimes there are anticholinergic effects - visual disturbances, dysuric phenomena. Possible functional disorders of the cardiovascular system with changes in the ECG in the form of an increase in the Q-T interval, a decrease in the T wave or its inversion, tachycardia or bradycardia. Sometimes there are side effects in the form of photosensitivity, dermatitis, skin pigmentation; skin allergic reactions are possible.

Sometimes there are anticholinergic effects - visual disturbances, dysuric phenomena. Possible functional disorders of the cardiovascular system with changes in the ECG in the form of an increase in the Q-T interval, a decrease in the T wave or its inversion, tachycardia or bradycardia. Sometimes there are side effects in the form of photosensitivity, dermatitis, skin pigmentation; skin allergic reactions are possible.

Antipsychotics of new generations, compared with traditional derivatives of phenothiazines and butyrophenones, cause significantly fewer side effects and complications.

Tranquilizers

Clinical characteristics. This group includes psychopharmacological agents that relieve anxiety, emotional tension, fear of non-psychotic origin, and facilitate the process of adaptation to stressful factors. Many of them have anticonvulsant and muscle relaxant properties. Their use in therapeutic doses does not cause significant changes in cognitive activity and perception. Many of the drugs in this group have a pronounced hypnotic effect and are used primarily as hypnotics. Unlike neuroleptics, tranquilizers do not have a pronounced antipsychotic activity and are used as an additional tool in the treatment of psychosis - to stop psychomotor agitation and correct the side effects of neuroleptics.

Many of the drugs in this group have a pronounced hypnotic effect and are used primarily as hypnotics. Unlike neuroleptics, tranquilizers do not have a pronounced antipsychotic activity and are used as an additional tool in the treatment of psychosis - to stop psychomotor agitation and correct the side effects of neuroleptics.

Side effects of during treatment with tranquilizers are most often manifested by daytime drowsiness, lethargy, muscle weakness, impaired concentration, short-term memory, as well as a slowdown in the speed of mental reactions. In some cases, paradoxical reactions develop in the form of anxiety, insomnia, psychomotor agitation, hallucinations. Among the dysfunctions of the autonomic nervous system and other organs and systems, hypotension, constipation, nausea, urinary retention or incontinence, decreased libido are noted. Long-term use of tranquilizers is dangerous due to the possibility of developing addiction to them, i.e. physical and mental dependence.

Antidepressants

Clinical characteristics. This class of drugs includes drugs that increase the pathological hypothymic effect, as well as reduce depression-related somatovegetative disorders. A growing body of scientific evidence now suggests that antidepressants are effective for phobic anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorders. It is assumed that in these cases, not the actual antidepressant, but the anti-obsessional and antiphobic effects are realized. There is data confirming the ability of many antidepressants to increase the threshold of pain sensitivity, to have a preventive effect in migraine and vegetative crises.

Side effects. Side effects related to the central nervous system and the autonomic nervous system are expressed as dizziness, tremor, dysarthria, impaired consciousness in the form of delirium, epileptiform seizures. Possible exacerbation of anxious disorders, activation of suicidal tendencies, inversion of affect, drowsiness or, conversely, insomnia. Side effects may be manifested by hypotension, sinus tachycardia, arrhythmia, impaired atrioventricular conduction.

Side effects may be manifested by hypotension, sinus tachycardia, arrhythmia, impaired atrioventricular conduction.

When taking tricyclic antidepressants, various anticholinergic effects are often observed, as well as an increase in appetite. With the simultaneous use of MAO inhibitors with food products containing tyramine or its precursor - tyrosine (cheeses, etc.), a "cheese effect" occurs, manifested by hypertension, hyperthermia, convulsions and sometimes leading to death.

When prescribing serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and reversible MAO-A inhibitors, there may be disturbances in the activity of the gastrointestinal tract, headaches, insomnia, anxiety, and impotence may develop against the background of SSRIs. In the case of a combination of SSRIs with drugs of the tricyclic group, the formation of the so-called serotonin syndrome, which is manifested by an increase in body temperature and signs of intoxication, is possible.

Normotimics

Clinical characteristics. Normotimics include drugs that regulate affective manifestations and have a prophylactic effect in phasic affective psychoses. Some of these drugs are anticonvulsants.

Normotimics include drugs that regulate affective manifestations and have a prophylactic effect in phasic affective psychoses. Some of these drugs are anticonvulsants.

Side effects of when using lithium salts are most commonly tremors. Often there are violations of the function of the gastrointestinal tract - nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, diarrhea. Often there is an increase in body weight, polydipsia, polyuria, hypothyroidism. Acne, maculo-papular rash, alopecia, as well as worsening of psoriasis are possible.

Signs of severe toxic conditions and overdose of the drug are a metallic taste in the mouth, thirst, severe tremor, dysarthria, ataxia; in these cases, the drug should be stopped immediately.

It should also be noted that side effects may be associated with non-compliance with the diet - a large intake of liquid, salt, smoked meats, cheeses.

Side effects of anticonvulsants are most often associated with functional disorders of the central nervous system and manifest as lethargy, drowsiness, ataxia. Hyperreflexia, myoclonus, tremor can be observed much less frequently. The severity of these phenomena is significantly reduced with a smooth increase in doses.

Hyperreflexia, myoclonus, tremor can be observed much less frequently. The severity of these phenomena is significantly reduced with a smooth increase in doses.

With a pronounced cardiotoxic effect, atrioventricular block may develop.

Nootropics

Clinical characteristics. Nootropics include drugs that can positively affect cognitive functions, stimulate learning, enhance memory processes, increase brain resistance to various adverse factors (in particular, to hypoxia) and extreme stress. However, they do not have a direct stimulating effect on mental activity, although in some cases they can cause anxiety and sleep disturbance.

Side effects - rare. Sometimes there are nervousness, irritability, elements of psychomotor agitation and disinhibition of drives, as well as anxiety and insomnia. Dizziness, headache, nausea and abdominal pain may occur.

Psychostimulants

Clinical characteristics.