Effects of verbal abuse on the brain

Verbal beatings hurt as much as sexual abuse – Harvard Gazette

Sticks and stones may break my bones,

But names will never hurt me. …

That often repeated children’s rhyme is wrong, according to Harvard University psychiatrists. Scolding, swearing, yelling, blaming, insulting, threatening, ridiculing, demeaning, and criticizing can be as harmful as physical abuse, sexual abuse outside the home, or witnessing physical abuse at home, notes a report in the April issue of the Harvard Mental Health Letter.

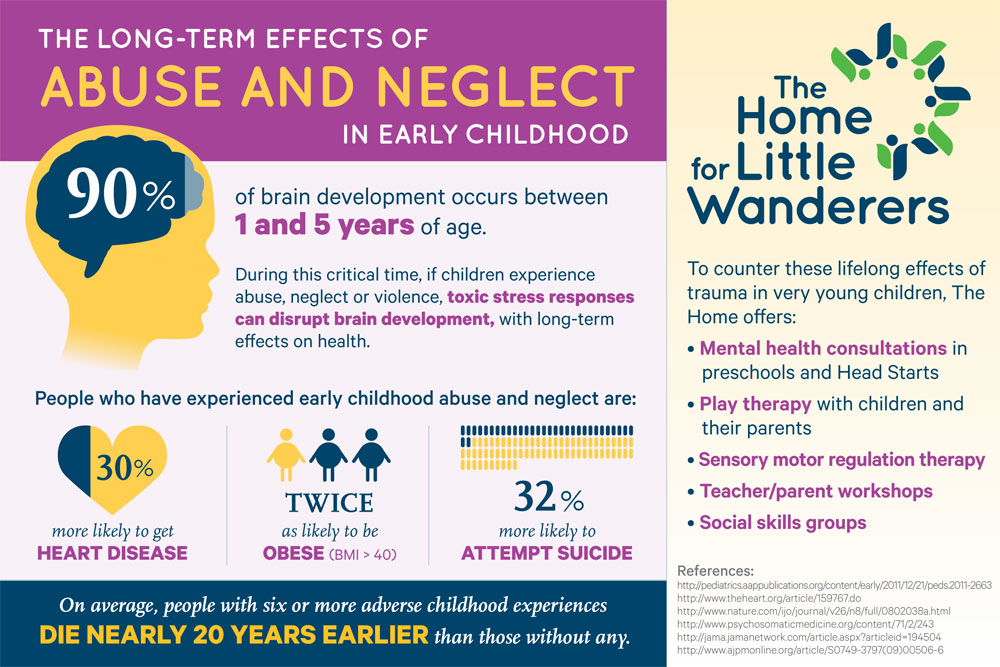

The report suggests that, when verbal abuse is constant and severe, it creates a risk of post-traumatic stress disorder, the same type of psychological collapse experienced by combat troops in Iraq. The research on which the report is based points out that children who are the target of frequent verbal mistreatment exhibit higher rates of physical aggression, delinquency, and social problems than other children.

Many studies tie physical and sexual abuse to lasting effects on the brain and behavior, but emotional mistreatment has not received the same focus. “Exposure to verbal aggression has received little attention as a specific form of abuse,” notes Martin Teicher, associate professor of psychiatry at McLean Hospital, a Harvard-affiliated psychiatric facility. “This despite the fact that one national study found that 63 percent of American parents reported one or more instances of verbal aggression, such as swearing at and insulting their child.”

Other researchers have associated childhood verbal abuse with a significantly higher risk of developing unstable, angry personalities, narcissistic behavior, obsessive-compulsive disorders, and paranoia. “Verbal abuse may also have more lasting consequences than other forms of abuse, because it’s often more continuous,” says Teicher. “And in combination with physical abuse and neglect [it] may produce the most dire outcome. However, child protective service agencies, doctors, and lawyers are most concerned about the impact and prevention of physical or sexual abuse.”

This situation prodded Teicher and three colleagues — Jacqueline Samson, Ann Polcari, and Cynthia McGreenery — to do a study comparing the impact of childhood verbal abuse in both the presence and absence of physical and sexual abuse and exposure to family violence.

Badgering vs. battering

They recruited 554 young people, aged 18 to 22 years, who responded to advertisements. About half were women and most were white. They all filled out questionnaires about unhappy childhoods and verbal abuse.

Typical of the respondents was Angela, an 18-year-old college freshman who enrolled in the study after seeing a subway car advertisement for people who had an unhappy childhood. “This is the first time I have thought about these things in years,” she said, “and the first time I have talked about it.”

Verbal abuse, the researchers found, had as great an effect as physical or nondomestic sexual mistreatment. Verbal aggression alone turns out to be a particularly strong risk factor for depression, anger-hostility, and dissociation disorders. The latter involve cutting off a particular mental function from the rest of the mind. In one type of dissociation, the person can’t recall part of his or her personal history. Other types involve hallucinations, feeling unreal or unstable, unconsciously converting painful emotions into physical symptoms, and multiple personalities.

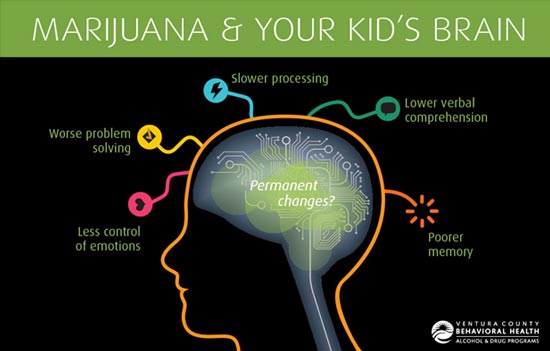

“Our findings raise the possibility that exposure to verbal aggression may affect the development of certain vulnerable brain regions in susceptible individuals,” Teicher’s group warns. “Alternatively, such exposure in childhood may put into force a powerful negative model for interpersonal relationships.” Possible consequences could include insecure attachments to others, negative feelings about oneself in relation to others, poor social functioning, and lowered self-esteem and coping strategies. Worse, says, Teicher, “such possibilities are not mutually exclusive.”

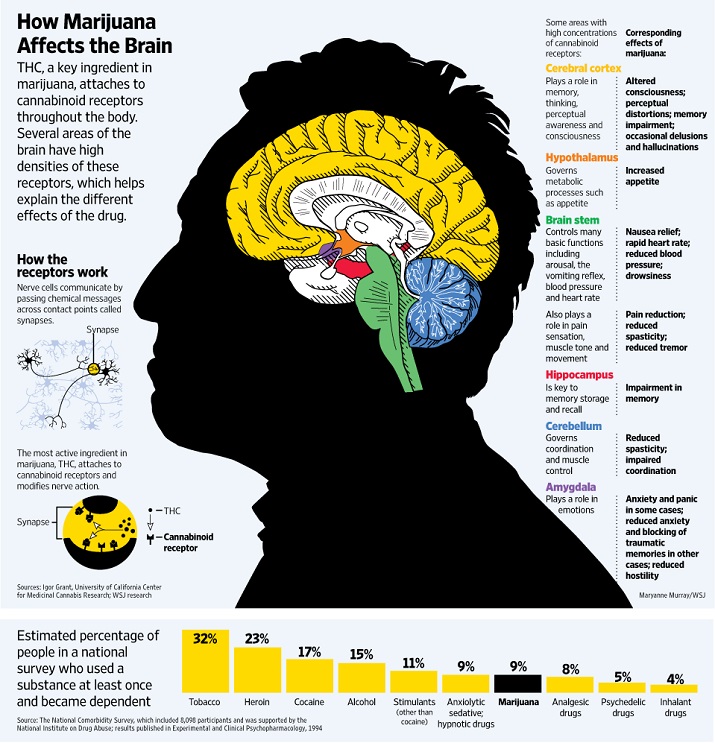

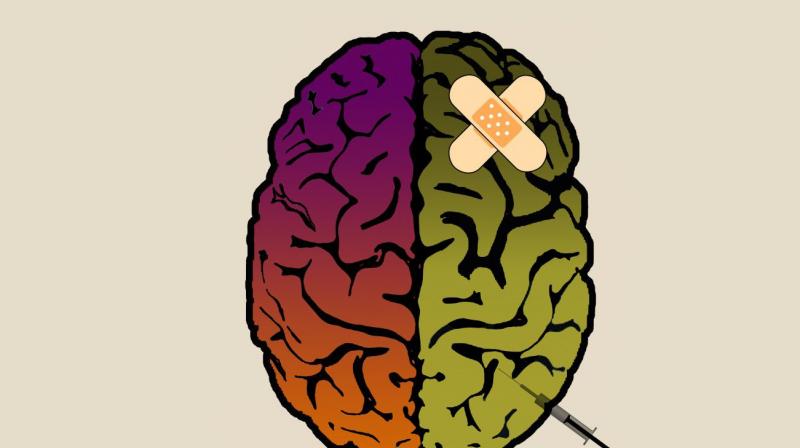

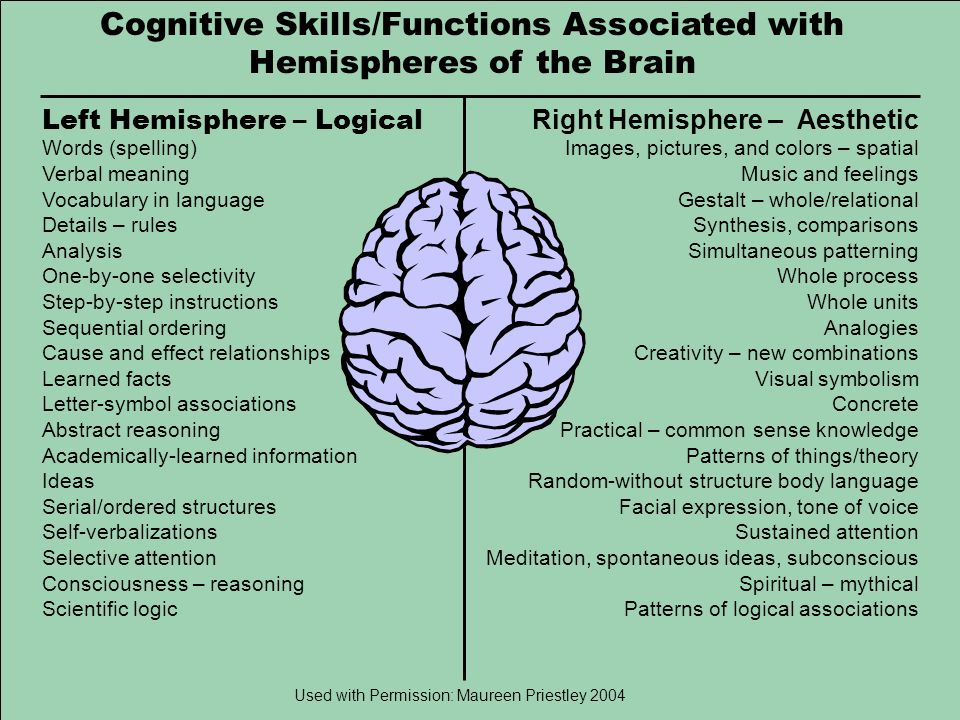

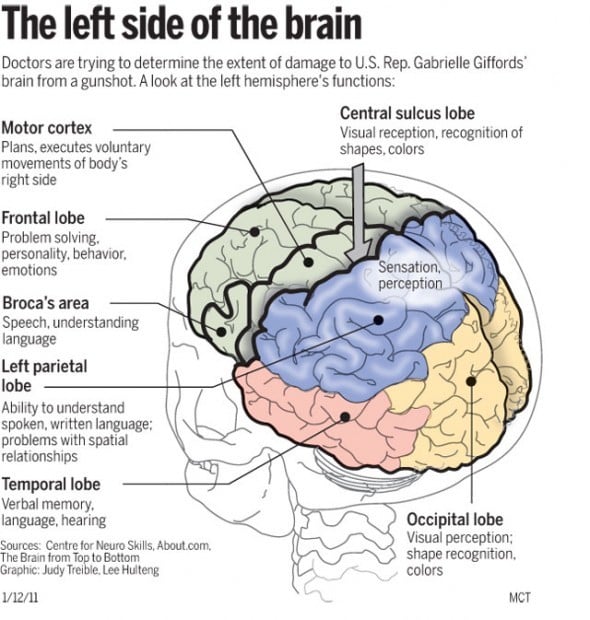

As yet unpublished research by Teicher shows that, indeed, exposure to verbal abuse does affect certain areas of the brain. These areas are associated with changes in verbal IQ and symptoms of depression, dissociation, and anxiety.

Violence at home

The effects of verbal abuse were worse than witnessing serious domestic violence and as serious as sexual abuse outside the home, but not as bad as sexual abuse by a family member. Of 54 people in the study who witnessed domestic violence, 35 saw their mothers being threatened or assaulted. Twenty-three witnessed brothers and sisters being physically mistreated. Thirteen of these attacks involved severe beatings.

Of 54 people in the study who witnessed domestic violence, 35 saw their mothers being threatened or assaulted. Twenty-three witnessed brothers and sisters being physically mistreated. Thirteen of these attacks involved severe beatings.

It is possible, the team points out, “that exposure to domestic emotional, physical, or sexual abuse is greatest in families with mental illness. Thus, genetic factors could contribute to the higher symptom scores we found in subjects exposed to domestic abuse.”

On the other hand, they note that the overall degree of psychological problems they found is probably lower for their college-educated, mainly upper middle-class subjects than it would be for the population in general.

The take-home message is that occasional harsh or angry words are not going to traumatize a child for life. However, frequent verbal bashing could be as bad as sticks and stones that break their bones.

the effects of chronic verbal abuse in childhood • Liberty Counselling Luxembourg

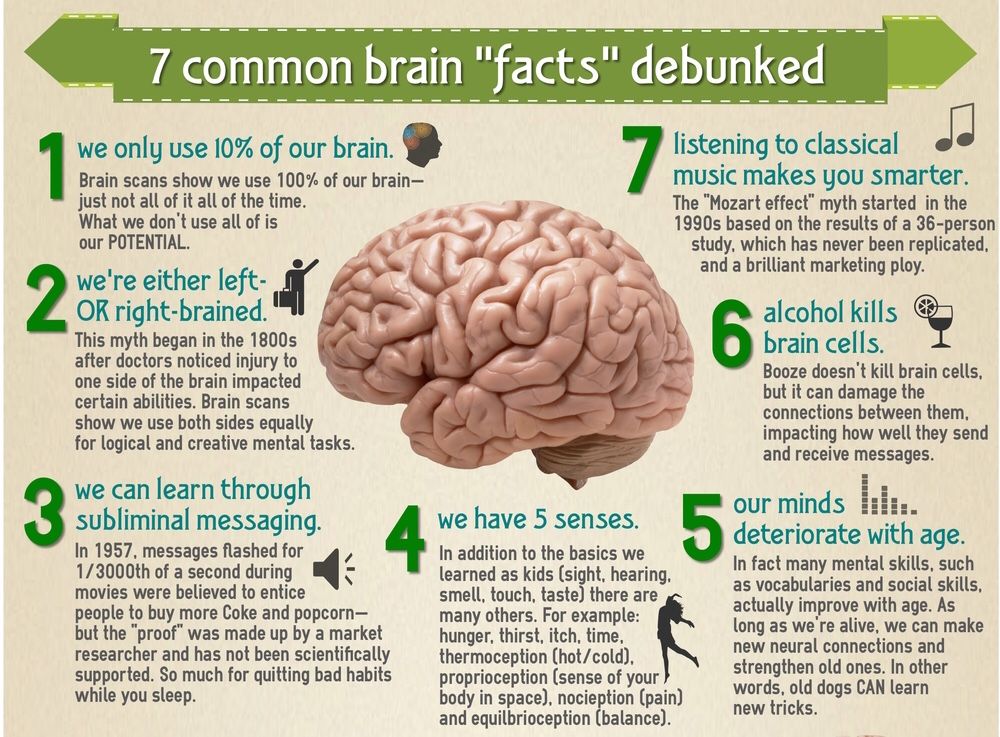

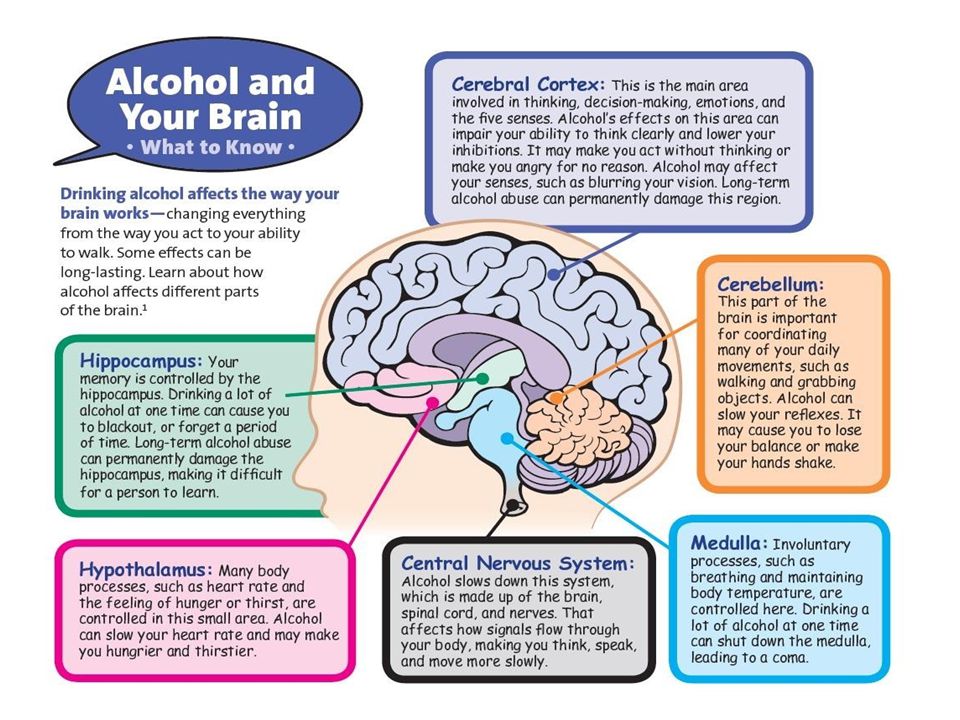

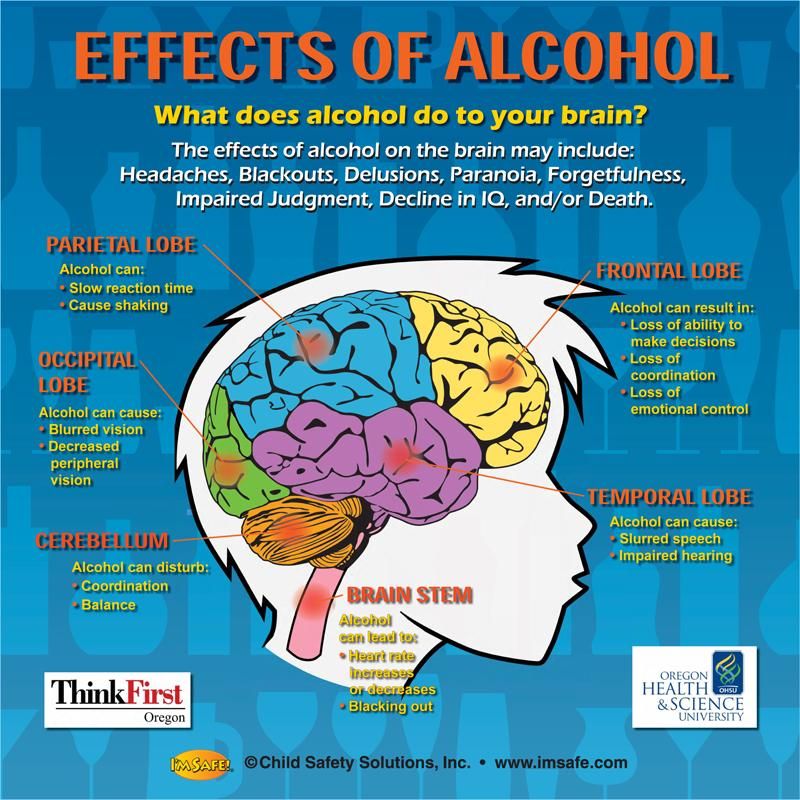

If you still go around saying “Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words can never hurt me”, it is time you revaluated that belief. As neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett explains in her brilliant new book “Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain”, exposure to verbal abuse sustained over a long period has other significant harming effects that go beyond low self-esteem. Because the brain regions that process language also control the insides of our bodies, verbal abuse also impacts heart rate, glucose levels and the flow of chemicals that support our immune system. As kind words make us feel loved, calmer, and stronger, aggressive ones have the power to harm our physical health.

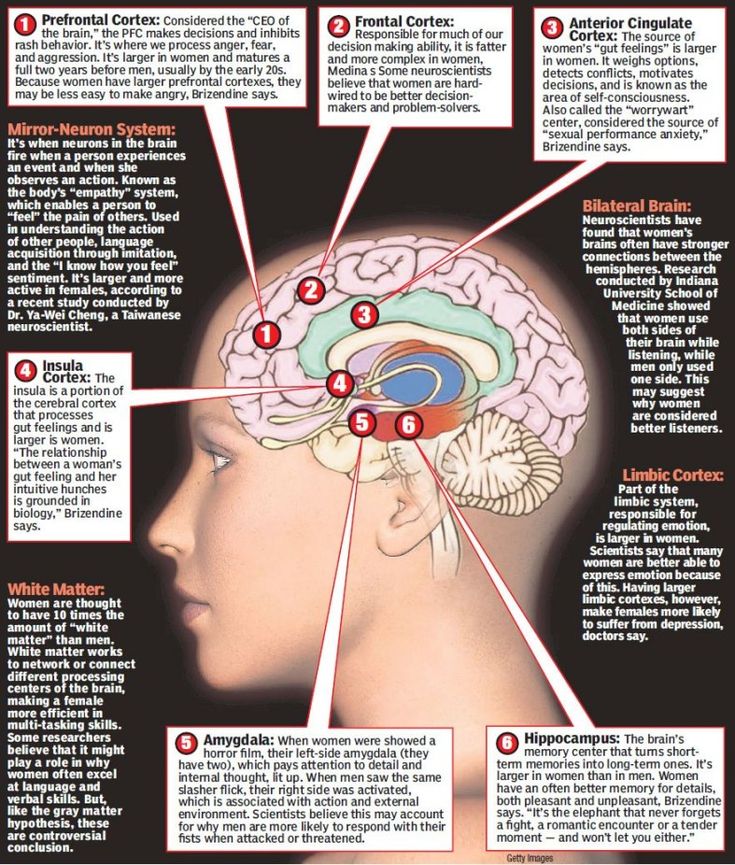

As neuroscientist Lisa Feldman Barrett explains in her brilliant new book “Seven and a Half Lessons About the Brain”, exposure to verbal abuse sustained over a long period has other significant harming effects that go beyond low self-esteem. Because the brain regions that process language also control the insides of our bodies, verbal abuse also impacts heart rate, glucose levels and the flow of chemicals that support our immune system. As kind words make us feel loved, calmer, and stronger, aggressive ones have the power to harm our physical health.

Words, then, are tools for regulating human bodies. Other people’s words have a direct effect on your brain activity and your bodily systems, and your words have the same effect on other people. Whether you intend that effect is irrelevant. It’s how we are wired.

Lisa Feldman Barrett, 2020

When abusive individuals use words as weapons to mistreat, manipulate, and control others, their victims also become more vulnerable to anxiety, depression, anger, mood disorders in young adulthood, Immune dysfunction, and more metabolic dysfunction. In view of such facts, the connection between verbal abuse and illnesses of the mind and body should no longer be downplayed or ignored.

In view of such facts, the connection between verbal abuse and illnesses of the mind and body should no longer be downplayed or ignored.

Although the above is of high concern to anyone who works in mental health, what Barrett and other neuroscientists have demonstrated through extensive research on the effects of emotional and verbal abuse does not surprise me. As a trauma counsellor who specialises in childhood/developmental trauma, I have had several clients who grew up in highly dysfunctional family environments who suffer from at least one chronic illness or physical vulnerability like the ones mentioned above. Interestingly, their onset is mostly felt in their late teens and adult years. When our bodies are submitted to chronic stress through our development, the probability of it having a negative effect on our immune, respiratory, digestive, nervous, endocrine, and cardiovascular systems is great.

It is time our culture stopped normalising verbal abuse, be it in oral or written form. Whether you have witnessed or suffered verbal abuse, be reminded of how toxic it is to everyone involved and take active steps to stop perpetuating it. You can do that autonomously by reassessing your own rigid beliefs about verbal aggression, negative emotions and vulnerability, such as “If I let that get to me, it means I am weak”, and start honouring how you feel with tolerance. Whatever you do, be it getting out of your comfort zone through investing in assertive behaviours or speaking out about abuse, you are actively changing not only your own way of thinking, but that of our collective consciousness.

Whether you have witnessed or suffered verbal abuse, be reminded of how toxic it is to everyone involved and take active steps to stop perpetuating it. You can do that autonomously by reassessing your own rigid beliefs about verbal aggression, negative emotions and vulnerability, such as “If I let that get to me, it means I am weak”, and start honouring how you feel with tolerance. Whatever you do, be it getting out of your comfort zone through investing in assertive behaviours or speaking out about abuse, you are actively changing not only your own way of thinking, but that of our collective consciousness.

Reference:

Barrett, L. F. (2020). Seven and a half lessons about the brain. Picador: London, UK

Lexical impact: why people have a hard time with verbal abuse - Ideonomics - Smart about the main thing

Photo: Carrie Kaufmann/Flickr Words don't hit as hard as stones. But let's not deceive ourselves. We know that some words really hurt. For example, insults. In a new study, researchers from the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands found that hearing insults is like receiving a lexical “mini-slap,” whether the insult is directed at you or another person.

In a new study, researchers from the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands found that hearing insults is like receiving a lexical “mini-slap,” whether the insult is directed at you or another person.

Why insults will always attract attention

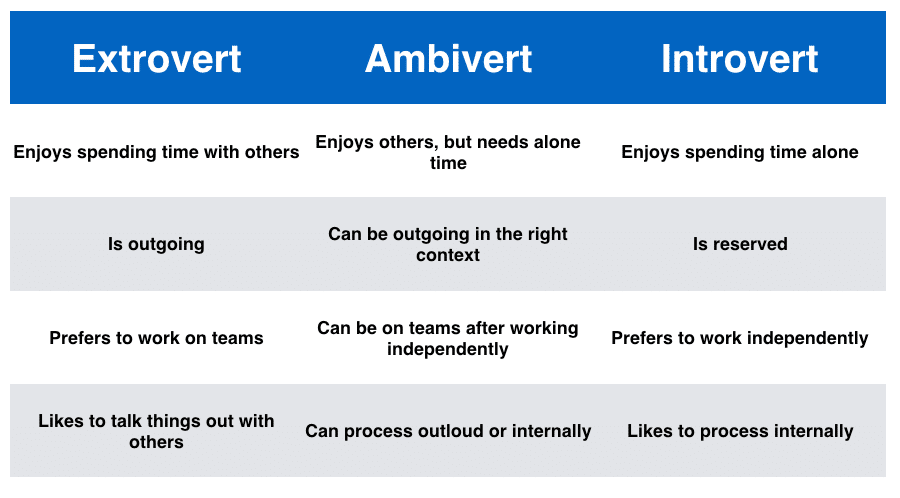

Some words and phrases are boring, while others are fascinating. Some give strength, others are designed to overwhelm you. Sometimes when people talk about love or with love, we start to feel the same. Conversely, speech full of hate makes one feel restless, anxious, perhaps even self-hatred.

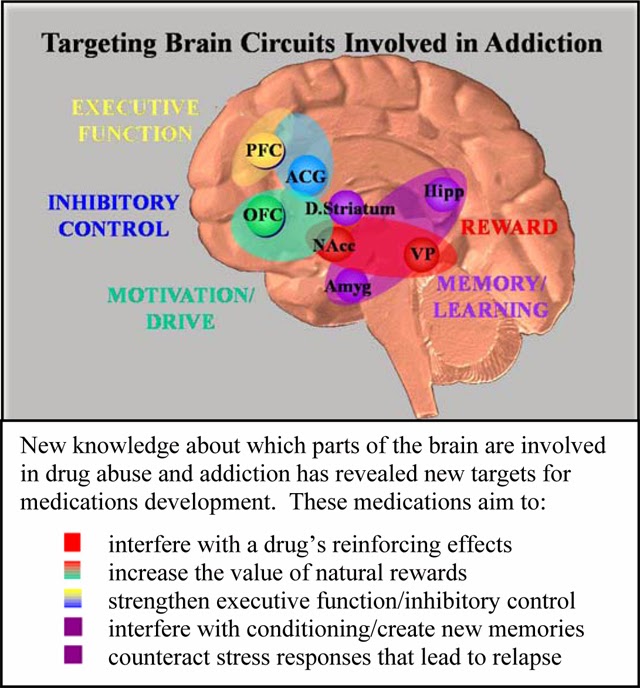

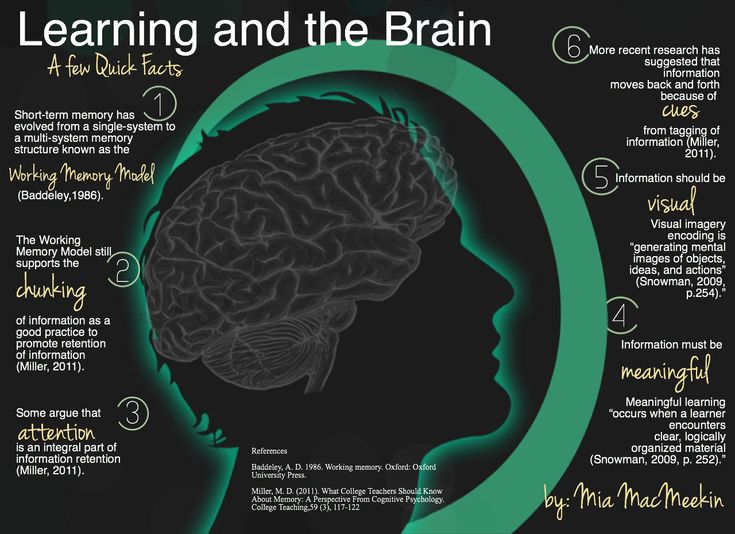

Exactly how language regulates emotions is not yet well understood, but research shows that words have both psychological and physiological effects. In one of them, Maria Richter and her colleagues observed the neural response of people who listened to or read negative words. They found that this increased implicit processing (IMP) in the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sACC) — that it was simply a technical way of saying negative words that released stress and anxiety hormones.

In another similar study, researchers found that children with high levels of negative self-talk had higher levels of anxiety.

We now know that negative language has both short and long term effects on cognition and emotional well-being. But what about deeply hurtful language, such as insults?

As a highly social species, humans have learned to build complex social networks and hierarchies, from humble tribes to powerful empires. Collaboration is one of the keys to success. But it also suggests that if a person is not respected or valued in a community, they will most likely fail to thrive—and at some point in history, they will not survive at all.

It is no wonder that insults that damage reputation and position in society pierce our ears like an arrow.

Researchers led by Mariin Struiksma wanted to learn more about the perception of insult versus compliment. As part of a larger research project looking at the relationship between language and emotion, they set out to find out how sensitive each type of utterance is to repetition (i. e., how do we react when we hear the same insult or compliment over and over again?).

e., how do we react when we hear the same insult or compliment over and over again?).

“The project focuses on the connection between language and emotions, and there is no better topic to explore this connection than insults and compliments. The proverb “Even though you call it a pot, just don’t put it in the stove” was memorized by children to respond to bullying. However, we believe that words hurt. Moreover, unlike compliments, the effect of which quickly passes, insults do not lose their sharpness. In this study, the main goal was to collect informal observations and study them in the laboratory. We wanted to find evidence of rapid adaptation to repeated compliments and a robust response to verbal abuse, and if successful, determine at what stage(s) of language processing this occurs,” says Struiksma.

Lexical slap

Researchers used electroencephalography and conductive electrodes connected to the scalp of 79 female volunteers. Each participant read aloud a series of repeated statements that conveyed three different meanings: insults (“Linda is disgusting”), compliments (“Linda is impressive”), and neutral (“Linda is Dutch”). The words referring to insults were rather mild for people used to Internet trolling, but as it turned out later, even they hurt feelings.

The words referring to insults were rather mild for people used to Internet trolling, but as it turned out later, even they hurt feelings.

“During the pre-testing of our materials, we had to come up with a long list of insults. We've come a long way. Fortunately, assistants helped us. But when we consulted with the members, we learned that insults tend to become outdated!” Struiksma says.

Half of the participants read three sets of statements using their own name, while the other half used someone else's. During the experiment, the participants did not communicate with anyone, but they were told that these were the statements of three different people.

Researching people's reactions to offensive language is not an easy task, as deliberately exposing people to offensive things is unethical in any form.

But despite the obvious limitations of a laboratory study in which there was no real human interaction, and insults were delivered by fictitious people, the participants nevertheless felt them.

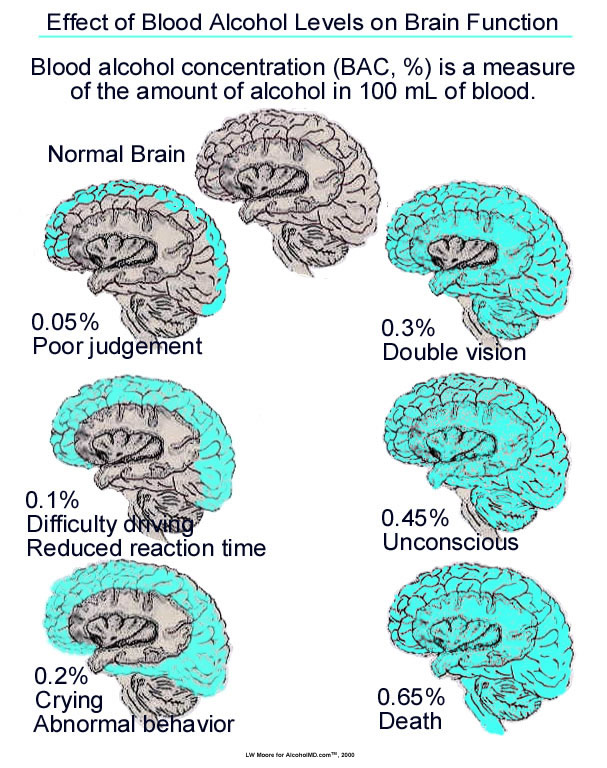

EEG data showed that hearing insult causes changes in the amplitude of P2, the wave component of the event-related potential measured on the human scalp. These effects were recorded regardless of who the insult was directed at, and were found to be consistent with repetition.

“The main findings are that the brain reacts quickly to insults and compliments, and the reaction is stronger to hurtful words. This early P2 component in the EEG signal indicates a very fast and stable capture of emotional attention caused by the extraction of the meaning of insults and compliments from long-term memory. The difference in response between insults and compliments becomes more noticeable over time. Therefore, even after repeated repetition of insults, a “mini-slap” is applied. This finding refers to highly negative evaluative words that automatically attract attention during lexical search. Remarkably, we found this in a lab experiment without any real interaction between the speakers. This not only indicates our sensitivity to unwanted social behavior, but also is consistent with the idea that the assessment of such behavior occurs automatically, ”says Struiksma.

This not only indicates our sensitivity to unwanted social behavior, but also is consistent with the idea that the assessment of such behavior occurs automatically, ”says Struiksma.

Compliments also caused a P2 effect, but not as strong as insults. When the participant's name was used in compliments or insults, the P2 signal was stronger and skin conductance (a measure of arousal) was higher than when participants were not called by name. Perhaps there is an evolutionary pressure that explains why people have become so receptive to compliments and insults, especially when they are directed at ourselves.

“Insults directed at you pose a serious threat to both you and your reputation. For members of an ultrasocial species that specializes in cooperation outside of the family, threats to reputation should not be taken lightly. Insults also harm others, they give information about who is going to do it, and signal social conflict in the environment or in the group. Representatives of ultrasocial species pay attention to such verbal "slaps". For a species that is actively involved in cooperation, the manifestation of aggression (for example, a verbal or physical slap) automatically causes negative emotions in the object of this aggression, as well as in bystanders, ”explains Struiksma.

For a species that is actively involved in cooperation, the manifestation of aggression (for example, a verbal or physical slap) automatically causes negative emotions in the object of this aggression, as well as in bystanders, ”explains Struiksma.

According to the researcher, these findings add to the body of evidence that people tend to be negative, by selectively focusing more on negative rather than positive words and situations.

“Research on negativity bias has shown that people are especially sensitive to negative events: not only do they attract more attention and require more intensive processing than neutral ones, but they also happen more often than positive ones. As you might expect, similar attention-grabbing and subsequent enhanced processing mechanisms operate when people read or listen to emotional speech. The reasons for this bias are currently being debated. Some argue that this is simply a reflection of the statistical properties of the environment, while others propose an evolutionary analysis that includes the extent to which negative and positive incentives affect fitness. Negativity bias does not guarantee that every negative stimulus or set of stimuli will attract more attention than a positive one. After all, a tangled shoelace is a much less emotional event than the birth of a child. The negative bias is real, but it exists as a common occurrence, occurring for reasons that have yet to be fully explained.”

Negativity bias does not guarantee that every negative stimulus or set of stimuli will attract more attention than a positive one. After all, a tangled shoelace is a much less emotional event than the birth of a child. The negative bias is real, but it exists as a common occurrence, occurring for reasons that have yet to be fully explained.”

Source

Interesting article? Subscribe to our Telegram channel for more educational content and fresh ideas.

Fresh materials

Neuroscientists have found that parental screaming destroys the brain of children

Studies show that screaming at a child for educational purposes is completely ineffective. Situations when parents cannot control their emotions are varied, but in fact it is fatigue and nervous exhaustion that are the main causes of such breakdowns.

Screaming affects children's brain development

A study conducted at the University of Pittsburgh (USA) showed that daily scandals have a very negative effect on the mental development of children and can cause the development of aggressive behavior or, conversely, their excessive stiffness and low self-esteem.

Psychologists analyzed 976 families for two years and found that yelling, which was part of parenting, caused behavioral problems in adolescents and depression in toddlers. In addition, the children became even more rebellious, and the injuries caused by such breakdowns were not “healed” by hugs and other gestures of love that parents showed when they came to themselves.

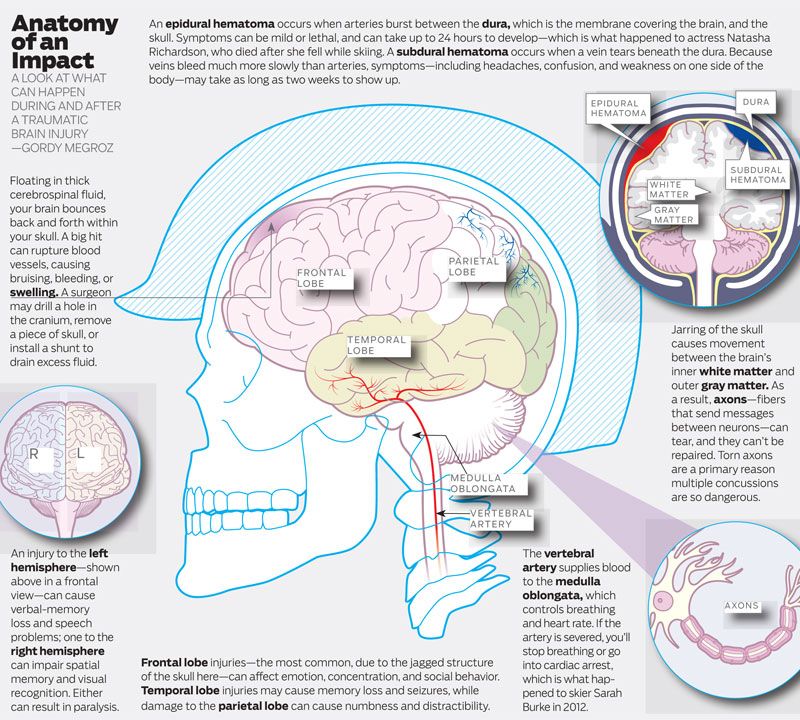

Another study by a group of psychiatrists from Harvard Medical School (USA) showed that verbal abuse, humiliation or reproaches made by mom or dad in a fit of anger can significantly and permanently change the structure of a child's brain. Scientists analyzed 50 babies receiving psychiatric treatment and compared them with 97 healthy children. They found that corporal and verbal punishment caused a significant reduction in the corpus callosum, the "cable" of nerve cells that connects the two hemispheres of the brain. As a result, activity in different parts of the brain decreased, memory and attention worsened, blood flow to the cerebellum decreased, all this ultimately led to a loss of emotional balance in children.

How to stop yelling at children

Observe what situations and at what times force you to yell at your child : before breakfast, before going to school, and so on. This template will help you find the true causes of your relapse, such as rush, stress, or fatigue. Perhaps the child is not to blame.

Try to predict the storm . In order not to break out on a child, you need time to calm down. If you feel like you're about to lose control, take a few slow, deep breaths, or just walk out of the room.

Do not set too high expectations . Often disappointment occurs when your ideas do not come true in reality, for example, you hoped that the child would do his homework on his own, but this did not happen. It is important to remember that your baby is just a child and he annoys you not because he likes it, but simply because of his immaturity.

Don't blame yourself . The feeling of guilt further increases the tension.