Effects of stress on child development

How the Body's Response Can Harm a Child's Development

AddictionAllergies & AsthmaAmbulatoryAudiologyAutismAwardsBC4TeensBehavioral HealthBehind the ScenesBurn CenterCancerCardiologyCenter for Healthy Weight and NutritionCenter for Injury Research and PolicyChild BehaviorChild DevelopmentColorectal and Pelvic ReconstructionCommunity EducationCommunity ResourcesCoronavirusDentistryDermatologyDiseases & ConditionsDiversity and InclusionEndocrinologyENTEpilepsyEverything MattersFertility and Reproductive Health ProgramFundraising EventsGastroenterologyGeneticsGynecologyHematologyHomecareHospiceHospital NewsInfants & NewbornsInfectious DiseaseKids & TeensLaboratory ServicesMake Safe HappenMarathonNeonatologyNephrologyNeurologyNeurosurgeryNew HospitalNICUNutrition & FitnessOccupational TherapyOphthalmologyOrthopedicsOur PatientsOur staffPalliative CareParentingPediatric NewsPharmacyPhysical Therapy - Sports and OrthopedicPlastic SurgeryPopulation HealthPregnancyPrimary CarePsychologyPulmonaryRadiologyReach Out and ReadRehabilitationResearchRheumatologySafety & PreventionSports MedicineSurgical ServicesThe Center for Family Safety and HealingTherapeutic RecreationTherapyTHRIVE ProgramToddlers & PreschoolersUrgent CareUrology

Aaron Barber, AT, ATC, PESAbbie Roth, MWCAbby Orkis, MSW, LSWAdam Ostendorf, MDAdriane Baylis, PhD, CCC-SLPAdrienne M. Flood, CPNP-ACAdvanced Healthcare Provider CouncilAila Co, MDAlaina White, AT, ATCAlana Milton, MDAlana Milton, MDAlecia Jayne, AuDAlena SchuckmannAlessandra Gasior, DOAlex Kemper, MDAlexandra Funk, PharmD, DABATAlexandra Sankovic, MDAlexis Klenke, RD, LDAlice Bass, CPNP-PCAlison PeggAllie DePoyAllison Rowland, AT, ATCAllison Strouse, MS, AT, ATCAmanda E. Graf, MDAmanda GoetzAmanda Smith, RN, BSN, CPNAmanda Sonk, LMTAmanda Whitaker, MDAmber Patterson, MDAmberle Prater, PhD, LPCCAmy Brown Schlegel, MDAmy Coleman, LISWAmy Dunn, MDAmy E. Valasek, MD, MScAmy Fanning, PT, DPTAmy Garee, CPNP-PCAmy Hahn, PhDAmy HessAmy Leber, PhDAmy LeRoy, CCLSAmy Moffett, CPNP-PCAmy Randall-McSorley, MMC, EdD CandidateAmy Thomas, BSN, RN, IBCLCAmy Wahl, APNAnastasia Fischer, MD, FACSMAndala HardyAndrea Brun, CPNP-PCAndrea M. Boerger, MEd, CCC-SLPAndrea Sattler, MDAndrew AxelsonAndrew Kroger, MD, MPHAndrew SchwadererAndria Haynes, RNAngela AbenaimAngela Billingslea, LISW-SAnn Pakalnis, MDAnna Lillis, MD, PhDAnnette Haban-BartzAnnie Drapeau, MDAnnie Temple, MS, CCC-SLP, CLCAnnie Truelove, MPHAnthony Audino, MDAnup D.

Patel, MDAri Rabkin, PhDAriana Hoet, PhDArielle Sheftall, PhDArleen KarczewskiAshlee HallAshleigh Kussman, MDAshley Debeljack, PsyDAshley Ebersole, MDAshley EcksteinAshley Kroon Van DiestAshley M. Davidson, AT, ATC, MSAshley Minnick, MSAH, AT, ATCAshley Overall, FNPAshley Parikh, CPNP-PCAshley Parker MSW, LISW-SAshley Parker, LISW-SAshley Tuisku, CTRSAsuncion Mejias, MD, PhDAurelia Wood, MDBailey Young, DOBecky Corbitt, RNBelinda Mills, MDBenjamin Fields, PhD, MEdBenjamin Kopp, MDBernadette Burke, AT, ATC, MSBeth Martin, RNBeth Villanueva, OTD, OTR/LBethany Uhl, MDBethany Walker, PhDBhuvana Setty, MDBill Kulju, MS, ATBlake SkinnerBonnie Gourley, MSW, LSWBrad Childers, RRT, BSBrandi Cogdill, RN, BSN, CFRN, EMT-PBrandon MorganBreanne L. Bowers, PT, DPT, CHT, CFSTBrendan Boyle, MD, MPHBrian Boe, MDBrian K. Kaspar, PhDBrian Kellogg, MDBriana Crowe, PT, DPT, OCSBrigid Pargeon, MS, MT-BCBrittney Hardin, MOT, OTR/LBrooke Sims, LPCC, ATRCagri Toruner, MDCaitlin Bauer, RD, LDCaitlin TullyCaleb MosleyCallista DammannCallista PoppCami Winkelspecht, PhDCamille Wilson, PhDCanice Crerand, PhDCara Inglis, PsyDCarl H.

Patel, MDAri Rabkin, PhDAriana Hoet, PhDArielle Sheftall, PhDArleen KarczewskiAshlee HallAshleigh Kussman, MDAshley Debeljack, PsyDAshley Ebersole, MDAshley EcksteinAshley Kroon Van DiestAshley M. Davidson, AT, ATC, MSAshley Minnick, MSAH, AT, ATCAshley Overall, FNPAshley Parikh, CPNP-PCAshley Parker MSW, LISW-SAshley Parker, LISW-SAshley Tuisku, CTRSAsuncion Mejias, MD, PhDAurelia Wood, MDBailey Young, DOBecky Corbitt, RNBelinda Mills, MDBenjamin Fields, PhD, MEdBenjamin Kopp, MDBernadette Burke, AT, ATC, MSBeth Martin, RNBeth Villanueva, OTD, OTR/LBethany Uhl, MDBethany Walker, PhDBhuvana Setty, MDBill Kulju, MS, ATBlake SkinnerBonnie Gourley, MSW, LSWBrad Childers, RRT, BSBrandi Cogdill, RN, BSN, CFRN, EMT-PBrandon MorganBreanne L. Bowers, PT, DPT, CHT, CFSTBrendan Boyle, MD, MPHBrian Boe, MDBrian K. Kaspar, PhDBrian Kellogg, MDBriana Crowe, PT, DPT, OCSBrigid Pargeon, MS, MT-BCBrittney Hardin, MOT, OTR/LBrooke Sims, LPCC, ATRCagri Toruner, MDCaitlin Bauer, RD, LDCaitlin TullyCaleb MosleyCallista DammannCallista PoppCami Winkelspecht, PhDCamille Wilson, PhDCanice Crerand, PhDCara Inglis, PsyDCarl H. Backes, MDCarlo Di Lorenzo, MDCarly FawcettCarol Baumhardt, LMTCarolyn FigiCarrie Rhodes, CPST-I, MTSA, CHESCasey Cottrill, MD, MPHCasey TrimbleCassandra McNabb, RN-BSNCatherine Earlenbaugh, RNCatherine Sinclair, MDCatherine Trimble, FNPCatrina Litzenburg, PhDCharae Keys, MSW, LISW-SCharles Elmaraghy, MDChelsea Britton, MS, RD, LD, CLC Chelsea Kebodeaux, MDChelsie Doster, BSCheryl Boop, MS, OTR/LCheryl G. Baxter, CPNPCheryl Gariepy, MDChet Kaczor, PharmD, MBAChris MarreroChris Smith, RNChristina Ching, MDChristina DayChristine Johnson, MA, CCC-SLPChristine Koterba, PhDChristine Mansfield, PT, DPT, OCS, ATCChristine PrusaChristopher Goettee, PT, DPT, OCSChristopher Iobst, MDChristopher Ouellette, MDChristy Lumpkins, LISW-SCindy IskeClaire Kopko PT, DPT, OCS, NASM-PESCody Hostutler, PhDConnor McDanel, MSW, LSWCorey Rood, MDCorinne Syfers, CCLSCourtney Bishop. PA-CCourtney Brown, MDCourtney Hall, CPNP-PCCourtney Porter, RN, MSCristina Tomatis Souverbielle, MDCrystal MilnerCurt Daniels, MDCynthia Holland-Hall, MD, MPHDana Lenobel, FNPDana Noffsinger, CPNP-ACDane Snyder, MDDaniel Coury, MDDaniel DaJusta, MDDanielle Peifer, PT, DPTDavid A Wessells, PT, MHADavid Axelson, MDDavid Stukus, MDDean Lee, MD, PhDDebbie Terry, NPDeborah Hill, LSWDeborah Zerkle, LMTDeena Chisolm, PhDDeipanjan Nandi, MD MScDenis King, MDDenise EllDennis Cunningham, MDDennis McTigue, DDSDiane LangDominique R.

Backes, MDCarlo Di Lorenzo, MDCarly FawcettCarol Baumhardt, LMTCarolyn FigiCarrie Rhodes, CPST-I, MTSA, CHESCasey Cottrill, MD, MPHCasey TrimbleCassandra McNabb, RN-BSNCatherine Earlenbaugh, RNCatherine Sinclair, MDCatherine Trimble, FNPCatrina Litzenburg, PhDCharae Keys, MSW, LISW-SCharles Elmaraghy, MDChelsea Britton, MS, RD, LD, CLC Chelsea Kebodeaux, MDChelsie Doster, BSCheryl Boop, MS, OTR/LCheryl G. Baxter, CPNPCheryl Gariepy, MDChet Kaczor, PharmD, MBAChris MarreroChris Smith, RNChristina Ching, MDChristina DayChristine Johnson, MA, CCC-SLPChristine Koterba, PhDChristine Mansfield, PT, DPT, OCS, ATCChristine PrusaChristopher Goettee, PT, DPT, OCSChristopher Iobst, MDChristopher Ouellette, MDChristy Lumpkins, LISW-SCindy IskeClaire Kopko PT, DPT, OCS, NASM-PESCody Hostutler, PhDConnor McDanel, MSW, LSWCorey Rood, MDCorinne Syfers, CCLSCourtney Bishop. PA-CCourtney Brown, MDCourtney Hall, CPNP-PCCourtney Porter, RN, MSCristina Tomatis Souverbielle, MDCrystal MilnerCurt Daniels, MDCynthia Holland-Hall, MD, MPHDana Lenobel, FNPDana Noffsinger, CPNP-ACDane Snyder, MDDaniel Coury, MDDaniel DaJusta, MDDanielle Peifer, PT, DPTDavid A Wessells, PT, MHADavid Axelson, MDDavid Stukus, MDDean Lee, MD, PhDDebbie Terry, NPDeborah Hill, LSWDeborah Zerkle, LMTDeena Chisolm, PhDDeipanjan Nandi, MD MScDenis King, MDDenise EllDennis Cunningham, MDDennis McTigue, DDSDiane LangDominique R. Williams, MD, MPH, FAAP, Dipl ABOMDonna M. Trentel, MSA, CCLSDonna Ruch, PhDDonna TeachDoug WolfDouglas McLaughlin, MDDrew Duerson, MDEd MinerEdward Oberle, MD, RhMSUSEdward Shepherd, MDEileen Chaves, PhDElena CamachoElise Berlan, MDElise DawkinsElizabeth A. Cannon, LPCCElizabeth Cipollone, LPCC-SElizabeth Zmuda, DOEllyn Hamm, MM, MT-BCEmily A. Stuart, MDEmily Decker, MDEmily GetschmanEmma Wysocki, PharmD, RDNEric Butter, PhDEric Leighton, AT, ATCEric Sribnick, MD, PhDErica Domrose, RD, LDEricca L Lovegrove, RD, LDErika RobertsErin Gates, PT, DPTErin Johnson, M.Ed., C.S.C.S.Erin Shann, BSN, RNErin TebbenFarah W. Brink, MDFatimah MasoodFrances Fei, MDGail Bagwell, DNP, APRN, CNSGail Besner, MDGail Swisher, ATGarey Noritz, MDGary A. Smith, MD, DrPHGeri Hewitt, MDGina Hounam, PhDGina McDowellGina MinotGrace Paul, MDGregory D. Pearson, MDGriffin Stout, MDGuliz Erdem, MDHailey Blosser, MA, CCC-SLPHanna MathessHeather Battles, MDHeather ClarkHeather L. Terry, MSN, RN, FNP-C, CUNPHeather Yardley, PhDHenry SpillerHenry Xiang, MD, MPH, PhDHerman Hundley, MS, AT, ATC, CSCSHilary Michel, MDHiren Patel, MDHolly Deckling, MSWHoma Amini, DDS, MPH, MSHoward Jacobs, MDHunter Wernick, DOIbrahim Khansa, MDIhuoma Eneli, MDIlana Moss, PhDIlene Crabtree, PTIrene Mikhail, MDIrina Buhimschi, MDIvor Hill, MDJackie Cronau, RN, CWOCNJacqueline Wynn, PhD, BCBA-DJacquelyn Doxie King, PhDJaime-Dawn Twanow, MDJaimie D.

Williams, MD, MPH, FAAP, Dipl ABOMDonna M. Trentel, MSA, CCLSDonna Ruch, PhDDonna TeachDoug WolfDouglas McLaughlin, MDDrew Duerson, MDEd MinerEdward Oberle, MD, RhMSUSEdward Shepherd, MDEileen Chaves, PhDElena CamachoElise Berlan, MDElise DawkinsElizabeth A. Cannon, LPCCElizabeth Cipollone, LPCC-SElizabeth Zmuda, DOEllyn Hamm, MM, MT-BCEmily A. Stuart, MDEmily Decker, MDEmily GetschmanEmma Wysocki, PharmD, RDNEric Butter, PhDEric Leighton, AT, ATCEric Sribnick, MD, PhDErica Domrose, RD, LDEricca L Lovegrove, RD, LDErika RobertsErin Gates, PT, DPTErin Johnson, M.Ed., C.S.C.S.Erin Shann, BSN, RNErin TebbenFarah W. Brink, MDFatimah MasoodFrances Fei, MDGail Bagwell, DNP, APRN, CNSGail Besner, MDGail Swisher, ATGarey Noritz, MDGary A. Smith, MD, DrPHGeri Hewitt, MDGina Hounam, PhDGina McDowellGina MinotGrace Paul, MDGregory D. Pearson, MDGriffin Stout, MDGuliz Erdem, MDHailey Blosser, MA, CCC-SLPHanna MathessHeather Battles, MDHeather ClarkHeather L. Terry, MSN, RN, FNP-C, CUNPHeather Yardley, PhDHenry SpillerHenry Xiang, MD, MPH, PhDHerman Hundley, MS, AT, ATC, CSCSHilary Michel, MDHiren Patel, MDHolly Deckling, MSWHoma Amini, DDS, MPH, MSHoward Jacobs, MDHunter Wernick, DOIbrahim Khansa, MDIhuoma Eneli, MDIlana Moss, PhDIlene Crabtree, PTIrene Mikhail, MDIrina Buhimschi, MDIvor Hill, MDJackie Cronau, RN, CWOCNJacqueline Wynn, PhD, BCBA-DJacquelyn Doxie King, PhDJaime-Dawn Twanow, MDJaimie D. Nathan, MD, FACSJames Murakami, MDJames Popp, MDJames Ruda, MDJameson Mattingly, MDJamie Macklin, MDJamie ReedyJane AbelJanelle Huefner, MA, CCC-SLPJanice M. Moreland, CPNP-PC, DNPJanice Townsend, DDS, MSJared SylvesterJason JacksonJason P. Garee, PhDJaysson EicholtzJean Hruschak, MA, CCC/SLPJeff Sydes, CSCSJeffery Auletta, MDJeffrey Bennett, MD, PhDJeffrey Hoffman, MDJeffrey Leonard, MDJen Campbell, PT, MSPTJena HeckJenn Gonya, PhDJennie Aldrink, MDJennifer Borda, PT, DPTJennifer HofherrJennifer LockerJennifer PrinzJennifer Reese, PsyDJennifer Smith, MS, RD, CSP, LD, LMTJennifer Walton, MD, MPH, FAAPJenny Worthington, PT, DPTJerry R. Mendell, MDJessalyn Mayer, MSOT, OTR/LJessica Bailey, PsyDJessica Bogacik, MS, MT-BCJessica Bowman, MDJessica BrockJessica Bullock, MA/CCC-SLPJessica Buschmann, RDJessica Scherr, PhDJim O’Shea OT, MOT, CHTJoan Fraser, MSW, LISW-SJohn Ackerman, PhDJohn Caballero, PT, DPT, CSCSJohn Kovalchin, MDJonathan D. Thackeray, MDJonathan Finlay, MB, ChB, FRCPJonathan M.

Nathan, MD, FACSJames Murakami, MDJames Popp, MDJames Ruda, MDJameson Mattingly, MDJamie Macklin, MDJamie ReedyJane AbelJanelle Huefner, MA, CCC-SLPJanice M. Moreland, CPNP-PC, DNPJanice Townsend, DDS, MSJared SylvesterJason JacksonJason P. Garee, PhDJaysson EicholtzJean Hruschak, MA, CCC/SLPJeff Sydes, CSCSJeffery Auletta, MDJeffrey Bennett, MD, PhDJeffrey Hoffman, MDJeffrey Leonard, MDJen Campbell, PT, MSPTJena HeckJenn Gonya, PhDJennie Aldrink, MDJennifer Borda, PT, DPTJennifer HofherrJennifer LockerJennifer PrinzJennifer Reese, PsyDJennifer Smith, MS, RD, CSP, LD, LMTJennifer Walton, MD, MPH, FAAPJenny Worthington, PT, DPTJerry R. Mendell, MDJessalyn Mayer, MSOT, OTR/LJessica Bailey, PsyDJessica Bogacik, MS, MT-BCJessica Bowman, MDJessica BrockJessica Bullock, MA/CCC-SLPJessica Buschmann, RDJessica Scherr, PhDJim O’Shea OT, MOT, CHTJoan Fraser, MSW, LISW-SJohn Ackerman, PhDJohn Caballero, PT, DPT, CSCSJohn Kovalchin, MDJonathan D. Thackeray, MDJonathan Finlay, MB, ChB, FRCPJonathan M. Grischkan, MDJonathan Napolitano, MDJoshua Prudent, MDJoshua Watson, MDJulee Eing, CRA, RT(R)Julia Colman, MOT, OTR/LJulie ApthorpeJulie Lange, MDJulie Leonard, MD, MPHJulie Racine, PhDJulie Samora, MDJustin Indyk, MD, PhDKady LacyKaitrin Kramer, DDS, MS, PhDKaleigh Hague, MA, MT-BCKaleigh MatesickKamilah Twymon, LPCC-SKara Malone, MDKara Miller, OTR/LKaren A. Diefenbach, MDKaren Allen, MDKaren Days, MBAKaren Rachuba, RD, LD, CLCKari A. Meeks, OTKari Cardiff, ODKari Dubro, MS, RD, LD, CWWSKari Phang, MDKarla Vaz, MDKaryn L. Kassis, MD, MPHKasey Strothman, MDKatherine Deans, MDKatherine McCracken, MD FACOGKathleen (Katie) RoushKathryn Blocher, CPNP-PCKathryn J. Junge, RN, BSNKathryn Obrynba, MDKatia Camille Halabi, MDKatie Brind'Amour, MSKatie DonovanKatie Thomas, APRKatrina Hall, MA, CCLSKatrina Ruege, LPCC-SKatya Harfmann, MDKayla Zimpfer, PCCKaylan Guzman Schauer, LPCC-SKeli YoungKelley SwopeKelli Dilver, PT, DPTKelly AbramsKelly BooneKelly HustonKelly J. Kelleher, MDKelly McNally, PhDKelly N.

Grischkan, MDJonathan Napolitano, MDJoshua Prudent, MDJoshua Watson, MDJulee Eing, CRA, RT(R)Julia Colman, MOT, OTR/LJulie ApthorpeJulie Lange, MDJulie Leonard, MD, MPHJulie Racine, PhDJulie Samora, MDJustin Indyk, MD, PhDKady LacyKaitrin Kramer, DDS, MS, PhDKaleigh Hague, MA, MT-BCKaleigh MatesickKamilah Twymon, LPCC-SKara Malone, MDKara Miller, OTR/LKaren A. Diefenbach, MDKaren Allen, MDKaren Days, MBAKaren Rachuba, RD, LD, CLCKari A. Meeks, OTKari Cardiff, ODKari Dubro, MS, RD, LD, CWWSKari Phang, MDKarla Vaz, MDKaryn L. Kassis, MD, MPHKasey Strothman, MDKatherine Deans, MDKatherine McCracken, MD FACOGKathleen (Katie) RoushKathryn Blocher, CPNP-PCKathryn J. Junge, RN, BSNKathryn Obrynba, MDKatia Camille Halabi, MDKatie Brind'Amour, MSKatie DonovanKatie Thomas, APRKatrina Hall, MA, CCLSKatrina Ruege, LPCC-SKatya Harfmann, MDKayla Zimpfer, PCCKaylan Guzman Schauer, LPCC-SKeli YoungKelley SwopeKelli Dilver, PT, DPTKelly AbramsKelly BooneKelly HustonKelly J. Kelleher, MDKelly McNally, PhDKelly N. Day, CPNP-PCKelly Pack, LISW-SKelly Tanner,PhD, OTR/L, BCPKelly Wesolowski, PsyDKelly Wise, PharmDKent Williams, MDKevin Bosse, PhDKevin Klingele, MDKim Bjorklund, MDKim Hammersmith, DDS, MPH, MSKimberly Bates, MDKimberly Sisto, PT, DPT, SCSKimberly Van Camp, PT, DPT, SCSKirk SabalkaKris Jatana, MD, FAAPKrista Winner, AuD, CCC-AKristen Armbrust, LISW-SKristen Cannon, MDKristen E. Beck, MDKristen Martin, OTR/LKristi Roberts, MS MPHKristina Booth, MSN, CFNPKristina Reber, MDKristol Das, MDKyle DavisLance Governale, MDLara McKenzie, PhD, MALaura Brubaker, BSN, RNLaura Dattner, MALaura Martin, MDLaurel Biever, LPCLauren Durinka, AuDLauren Garbacz, PhDLauren Justice, OTR/L, MOTLauren Madhoun, MS, CCC-SLPLauryn Rozum, MS, CCLSLeah Middelberg, MDLee Hlad, DPMLeena Nahata, MDLelia Emery, MT-BCLeslie Appiah, MDLinda Stoverock, DNP, RN NEA-BCLindsay Kneen, MDLindsay Pietruszewski, PT, DPTLindsay SchwartzLindsey Vater, PsyDLisa GoldenLisa Halloran, CNPLisa M. Humphrey, MDLogan Blankemeyer, MA, CCC-SLPLori Grisez PT, DPTLorraine Kelley-QuonLouis Bezold, MDLourdes Hill, LPCC-S Lubna Mazin, PharmDLuke Tipple, MS, CSCSLynda Wolfe, PhDLyndsey MillerLynn RosenthalLynne Ruess, MDMaggy Rule, MS, AT, ATCMahmoud Kallash, MDManmohan K Kamboj, MDMarc P.

Day, CPNP-PCKelly Pack, LISW-SKelly Tanner,PhD, OTR/L, BCPKelly Wesolowski, PsyDKelly Wise, PharmDKent Williams, MDKevin Bosse, PhDKevin Klingele, MDKim Bjorklund, MDKim Hammersmith, DDS, MPH, MSKimberly Bates, MDKimberly Sisto, PT, DPT, SCSKimberly Van Camp, PT, DPT, SCSKirk SabalkaKris Jatana, MD, FAAPKrista Winner, AuD, CCC-AKristen Armbrust, LISW-SKristen Cannon, MDKristen E. Beck, MDKristen Martin, OTR/LKristi Roberts, MS MPHKristina Booth, MSN, CFNPKristina Reber, MDKristol Das, MDKyle DavisLance Governale, MDLara McKenzie, PhD, MALaura Brubaker, BSN, RNLaura Dattner, MALaura Martin, MDLaurel Biever, LPCLauren Durinka, AuDLauren Garbacz, PhDLauren Justice, OTR/L, MOTLauren Madhoun, MS, CCC-SLPLauryn Rozum, MS, CCLSLeah Middelberg, MDLee Hlad, DPMLeena Nahata, MDLelia Emery, MT-BCLeslie Appiah, MDLinda Stoverock, DNP, RN NEA-BCLindsay Kneen, MDLindsay Pietruszewski, PT, DPTLindsay SchwartzLindsey Vater, PsyDLisa GoldenLisa Halloran, CNPLisa M. Humphrey, MDLogan Blankemeyer, MA, CCC-SLPLori Grisez PT, DPTLorraine Kelley-QuonLouis Bezold, MDLourdes Hill, LPCC-S Lubna Mazin, PharmDLuke Tipple, MS, CSCSLynda Wolfe, PhDLyndsey MillerLynn RosenthalLynne Ruess, MDMaggy Rule, MS, AT, ATCMahmoud Kallash, MDManmohan K Kamboj, MDMarc P. Michalsky, MDMarcel J. Casavant, MDMarci Johnson, LISW-SMarcie RehmarMarco Corridore, MDMargaret Bassi, OTR/LMaria HaghnazariMaria Vegh, MSN, RN, CPNMarissa Condon, BSN, RNMarissa E. Larouere, MBA, BSN, RNMark E. Galantowicz, MDMark Smith, MS RT R (MR), ABMP PhysicistMarnie Wagner, MDMary Ann Abrams, MD, MPHMary Fristad, PhD, ABPPMary Kay SharrettMary Shull, MDMatthew Washam, MD, MPHMeagan Horn, MAMegan Brundrett, MDMegan Dominik, OTR/LMegan FrancisMegan Letson, MD, M.EdMeghan Cass, PT, DPTMeghan Fisher, BSN, RNMeika Eby, MDMelanie Fluellen, LPCCMelanie Luken, LISW-SMelissa and Mikael McLarenMelissa McMillen, CTRSMelissa Winterhalter, MDMeredith Merz Lind, MDMichael Flores, PhDMichael T. Brady, MDMichelle Ross, MHA, RD, LD, ALCMike Patrick, MDMindy Deno, PT, DPTMitch Ellinger, CPNP-PCMolly Dienhart, MDMolly Gardner, PhDMonica Ardura, DOMonica EllisMonique Goldschmidt, MDMotao Zhu, MD, MS, PhDMurugu Manickam, MDNancy AuerNancy Cunningham, PsyDNancy Wright, BS, RRT, RCP, AE-C Naomi Kertesz, MDNatalie DeBaccoNatalie I.

Michalsky, MDMarcel J. Casavant, MDMarci Johnson, LISW-SMarcie RehmarMarco Corridore, MDMargaret Bassi, OTR/LMaria HaghnazariMaria Vegh, MSN, RN, CPNMarissa Condon, BSN, RNMarissa E. Larouere, MBA, BSN, RNMark E. Galantowicz, MDMark Smith, MS RT R (MR), ABMP PhysicistMarnie Wagner, MDMary Ann Abrams, MD, MPHMary Fristad, PhD, ABPPMary Kay SharrettMary Shull, MDMatthew Washam, MD, MPHMeagan Horn, MAMegan Brundrett, MDMegan Dominik, OTR/LMegan FrancisMegan Letson, MD, M.EdMeghan Cass, PT, DPTMeghan Fisher, BSN, RNMeika Eby, MDMelanie Fluellen, LPCCMelanie Luken, LISW-SMelissa and Mikael McLarenMelissa McMillen, CTRSMelissa Winterhalter, MDMeredith Merz Lind, MDMichael Flores, PhDMichael T. Brady, MDMichelle Ross, MHA, RD, LD, ALCMike Patrick, MDMindy Deno, PT, DPTMitch Ellinger, CPNP-PCMolly Dienhart, MDMolly Gardner, PhDMonica Ardura, DOMonica EllisMonique Goldschmidt, MDMotao Zhu, MD, MS, PhDMurugu Manickam, MDNancy AuerNancy Cunningham, PsyDNancy Wright, BS, RRT, RCP, AE-C Naomi Kertesz, MDNatalie DeBaccoNatalie I. Rine, PharmD, BCPS, BCCCPNatalie Powell, LPCC-S, LICDC-CSNatalie Rose, BSN, RNNathalie Maitre, MD, PhDNationwide Children's HospitalNationwide Children's Hospital Behavioral Health ExpertsNeetu Bali, MD, MPHNehal Parikh, DO, MSNichole Mayer, OTR/L, MOTNicole Caldwell, MDNicole Dempster, PhDNicole Greenwood, MDNicole Parente, LSWNicole Powell, PsyD, BCBA-DNina WestNkeiruka Orajiaka, MBBSOctavio Ramilo, MDOliver Adunka, MD, FACSOlivia Stranges, CPNP-PCOlivia Thomas, MDOmar Khalid, MD, FAAP, FACCOnnalisa Nash, CPNP-PCOula KhouryPaige Duly, CTRSParker Huston, PhDPatrick C. Walz, MDPatrick Queen, BSN, RNPedro Weisleder, MDPeter Minneci, MDPeter White, PhDPitty JenningsPreeti Jaggi, MDRachael Morocco-Zanotti, DORachel D’Amico, MDRachel Schrader, CPNP-PCRachel Tyson, LSWRajan Thakkar, MDRaymond Troy, MDRebecca Fisher, PTRebecca Hicks, CCLSRebecca Lewis, AuD, CCC-ARebecca M. Romero, RD, LD, CLC Reggie Ash Jr.Reno Ravindran, MDRichard Kirschner, MDRichard Wood, MDRobert A. Kowatch, MD, Ph.D.Robert Hoffman, MDRochelle Krouse, CTRSRohan Henry, MD, MSRose Ayoob, MDRose Schroedl, PhDRosemary Martoma, MDRoss Maltz, MDRyan Ingley AT, ATCSamanta Boddapati, PhDSamantha MaloneSammy CygnorSandra C.

Rine, PharmD, BCPS, BCCCPNatalie Powell, LPCC-S, LICDC-CSNatalie Rose, BSN, RNNathalie Maitre, MD, PhDNationwide Children's HospitalNationwide Children's Hospital Behavioral Health ExpertsNeetu Bali, MD, MPHNehal Parikh, DO, MSNichole Mayer, OTR/L, MOTNicole Caldwell, MDNicole Dempster, PhDNicole Greenwood, MDNicole Parente, LSWNicole Powell, PsyD, BCBA-DNina WestNkeiruka Orajiaka, MBBSOctavio Ramilo, MDOliver Adunka, MD, FACSOlivia Stranges, CPNP-PCOlivia Thomas, MDOmar Khalid, MD, FAAP, FACCOnnalisa Nash, CPNP-PCOula KhouryPaige Duly, CTRSParker Huston, PhDPatrick C. Walz, MDPatrick Queen, BSN, RNPedro Weisleder, MDPeter Minneci, MDPeter White, PhDPitty JenningsPreeti Jaggi, MDRachael Morocco-Zanotti, DORachel D’Amico, MDRachel Schrader, CPNP-PCRachel Tyson, LSWRajan Thakkar, MDRaymond Troy, MDRebecca Fisher, PTRebecca Hicks, CCLSRebecca Lewis, AuD, CCC-ARebecca M. Romero, RD, LD, CLC Reggie Ash Jr.Reno Ravindran, MDRichard Kirschner, MDRichard Wood, MDRobert A. Kowatch, MD, Ph.D.Robert Hoffman, MDRochelle Krouse, CTRSRohan Henry, MD, MSRose Ayoob, MDRose Schroedl, PhDRosemary Martoma, MDRoss Maltz, MDRyan Ingley AT, ATCSamanta Boddapati, PhDSamantha MaloneSammy CygnorSandra C. Kim, MDSara Bentley, MT-BCSara Bode, MDSara Breidigan, MS, AT, ATCSara N. Smith, MSN, APRNSara O'Rourke, MOT, OTR/L, Clinical LeadSara Schroder, MDSarah A. Denny, MDSarah Cline, CRA, RT(R)Sarah Driesbach, CPN, APNSarah GreenbergSarah Hastie, BSN, RNC-NIC Sarah Keim, PhDSarah MyersSarah O'Brien, MDSarah SaxbeSarah Schmidt, LISW-SSarah ScottSarah TraceySarah VerLee, PhDSasigarn Bowden, MDSatya Gedela, MD, MRCP(UK)Scott Coven, DO, MPHScott Hickey, MDSean EingSean Rose, MDSeth Alpert, MDShalini C. Reshmi, PhD, FACMGShana Moore, MA, CCC-AShannon Reinhart, LISW-SShari UncapherSharon Wrona, DNP, PNP, PMHSShaun Coffman PT, DPT, OCSShawn Pitcher, BS, RD, USAWShawNaye Scott-MillerShea SmoskeSheena PaceSheila GilesShelly BrackmanSimon Lee, MDSini James, MDStacy Ardoin, MDStacy Whiteside APRN, MS, CPNP-AC/PC, CPONStefanie Bester, MDStefanie Hirota, OTR/LStephanie Burkhardt, MPH, CCRCStephanie CannonStephanie Santoro, MDStephanie Vyrostek BSN, RNStephen Hersey, MDSteve Allen, MDSteven C. Matson, MDSteven Ciciora, MDSteven CuffSuellen Sharp, OTR/L, MOTSurlina AsamoaSusan Colace, MDSusan Creary, MDSwaroop Pinto, MDTabatha BallardTabbetha GrecoTabi Evans, PsyDTabitha Jones-McKnight, DOTahagod Mohamed, MDTamara MappTammi Young-Saleme, PhDTaylor Hartlaub, MD, MPHTerry Barber, MDTerry Bravender, MD, MPHTerry Laurila, MS, RPhTheresa Miller, BA, RRT, RCP, AE-C, CPFTThomas Pommering, DOTiasha Letostak, PhDTiffanie Ryan, BCBA Tim RobinsonTim Smith, MDTimothy Cripe, MD, PhDTimothy Landers PhD RN APRN-CNP CIC FAANTracey L.

Kim, MDSara Bentley, MT-BCSara Bode, MDSara Breidigan, MS, AT, ATCSara N. Smith, MSN, APRNSara O'Rourke, MOT, OTR/L, Clinical LeadSara Schroder, MDSarah A. Denny, MDSarah Cline, CRA, RT(R)Sarah Driesbach, CPN, APNSarah GreenbergSarah Hastie, BSN, RNC-NIC Sarah Keim, PhDSarah MyersSarah O'Brien, MDSarah SaxbeSarah Schmidt, LISW-SSarah ScottSarah TraceySarah VerLee, PhDSasigarn Bowden, MDSatya Gedela, MD, MRCP(UK)Scott Coven, DO, MPHScott Hickey, MDSean EingSean Rose, MDSeth Alpert, MDShalini C. Reshmi, PhD, FACMGShana Moore, MA, CCC-AShannon Reinhart, LISW-SShari UncapherSharon Wrona, DNP, PNP, PMHSShaun Coffman PT, DPT, OCSShawn Pitcher, BS, RD, USAWShawNaye Scott-MillerShea SmoskeSheena PaceSheila GilesShelly BrackmanSimon Lee, MDSini James, MDStacy Ardoin, MDStacy Whiteside APRN, MS, CPNP-AC/PC, CPONStefanie Bester, MDStefanie Hirota, OTR/LStephanie Burkhardt, MPH, CCRCStephanie CannonStephanie Santoro, MDStephanie Vyrostek BSN, RNStephen Hersey, MDSteve Allen, MDSteven C. Matson, MDSteven Ciciora, MDSteven CuffSuellen Sharp, OTR/L, MOTSurlina AsamoaSusan Colace, MDSusan Creary, MDSwaroop Pinto, MDTabatha BallardTabbetha GrecoTabi Evans, PsyDTabitha Jones-McKnight, DOTahagod Mohamed, MDTamara MappTammi Young-Saleme, PhDTaylor Hartlaub, MD, MPHTerry Barber, MDTerry Bravender, MD, MPHTerry Laurila, MS, RPhTheresa Miller, BA, RRT, RCP, AE-C, CPFTThomas Pommering, DOTiasha Letostak, PhDTiffanie Ryan, BCBA Tim RobinsonTim Smith, MDTimothy Cripe, MD, PhDTimothy Landers PhD RN APRN-CNP CIC FAANTracey L. Sisk, RN, BSN, MHATracie Rohal RD, LD, CDETracy Mehan, MATravis Gallagher, ATTrevor MillerTria Shadeed, NNPTyanna Snider, PsyDTyler Congrove, ATValencia Walker, MD, MPH, FAAPVanessa Shanks, MD, FAAPVenkata Rama Jayanthi, MDVidu Garg, MDVidya Raman, MDW. Garrett Hunt, MDWalter Samora, MDWarren D. Lo, MDWendy Anderson, MDWendy Cleveland, MA, LPCC-SWhitney McCormick, CTRSWhitney Raglin Bignall, PhDWilliam Cotton, MDWilliam J. Barson, MDWilliam Ray, PhDWilliam W. Long, MD

Sisk, RN, BSN, MHATracie Rohal RD, LD, CDETracy Mehan, MATravis Gallagher, ATTrevor MillerTria Shadeed, NNPTyanna Snider, PsyDTyler Congrove, ATValencia Walker, MD, MPH, FAAPVanessa Shanks, MD, FAAPVenkata Rama Jayanthi, MDVidu Garg, MDVidya Raman, MDW. Garrett Hunt, MDWalter Samora, MDWarren D. Lo, MDWendy Anderson, MDWendy Cleveland, MA, LPCC-SWhitney McCormick, CTRSWhitney Raglin Bignall, PhDWilliam Cotton, MDWilliam J. Barson, MDWilliam Ray, PhDWilliam W. Long, MD

Effects of Stress on Child Development

| 3 Types of Psychological Stress | Effects | Stressors for Toxic Stress | Toxic Stress vs Tolerable Stress |

Types Of Stress in Children

Stress is a normal and important part of healthy child development. However, the effects of stress on child development should not be underestimated. Find out why and their impacts on children.

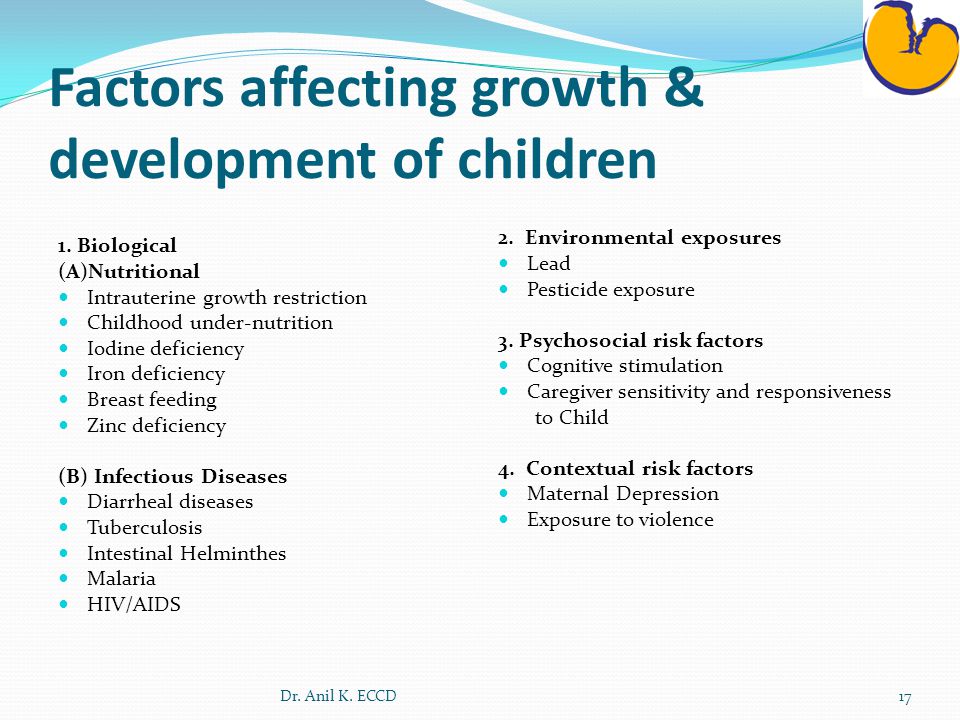

There are two main types of stress affecting humans1 – physiological stress (physical) and psychological stress. Physiological stressors are physical forces that are strong enough to challenge an individual’s physical limits. Psychological stressors are psychosocial strains that result from a person’s subjective interpretation, based on expectations, beliefs, or assumptions stemming from their previous experiences.

Physiological stressors are physical forces that are strong enough to challenge an individual’s physical limits. Psychological stressors are psychosocial strains that result from a person’s subjective interpretation, based on expectations, beliefs, or assumptions stemming from their previous experiences.

Physiological stress results from changes in the outside world, whereas psychological stress is rooted in the brain. Previous experiences affect whether a psychological stress response is triggered.

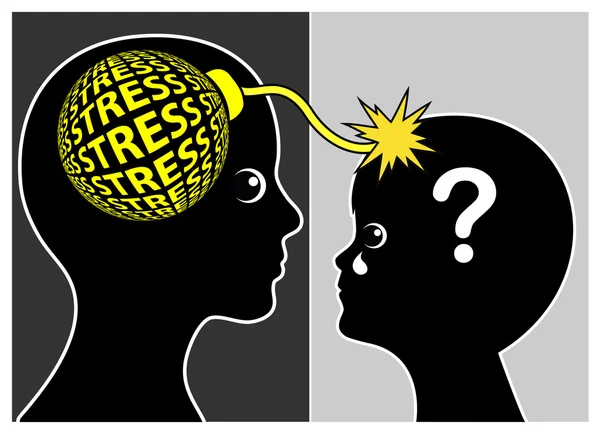

When the stress response is activated, a child’s perception of control over the stressor, based on prior experiences, determines the stress’ intensity, duration, and long-term effects.

That means, given the same stressor, each child perceives the stress differently because of their unique life experiences in the past.

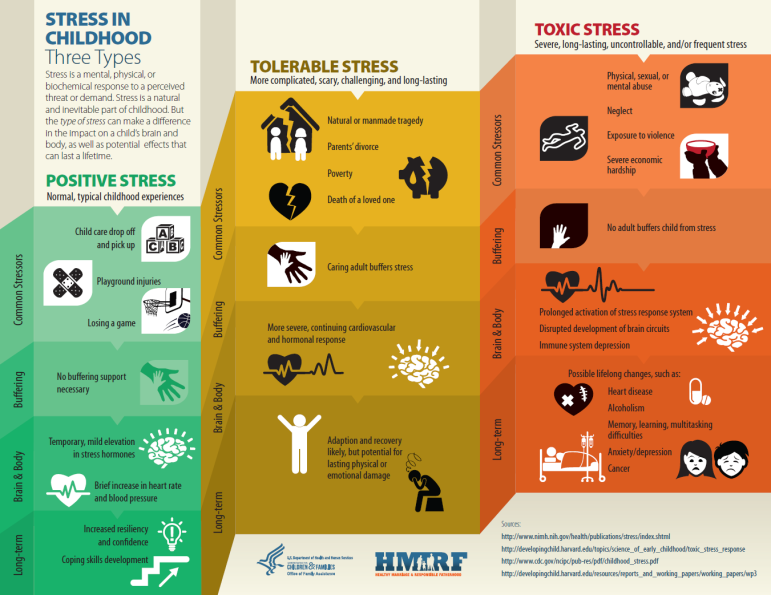

3 Types of psychological stress

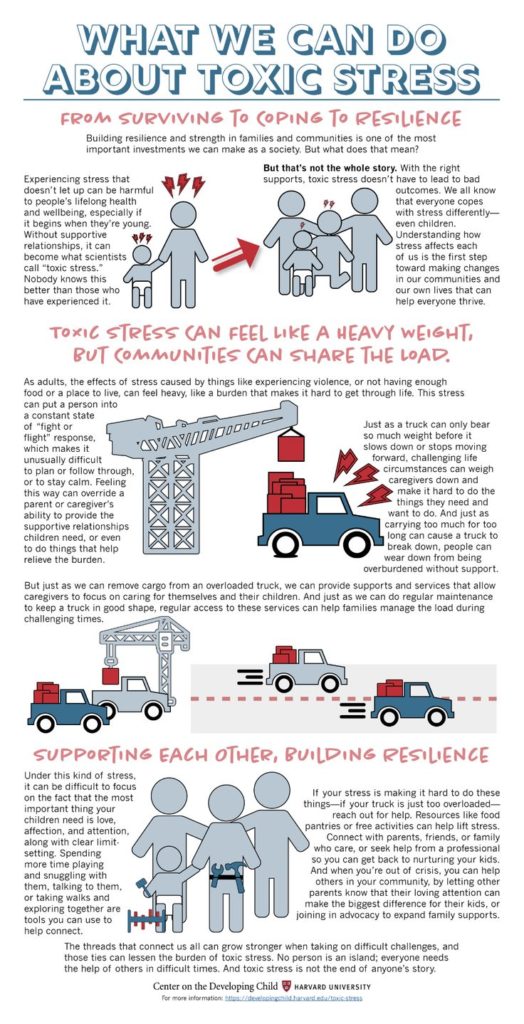

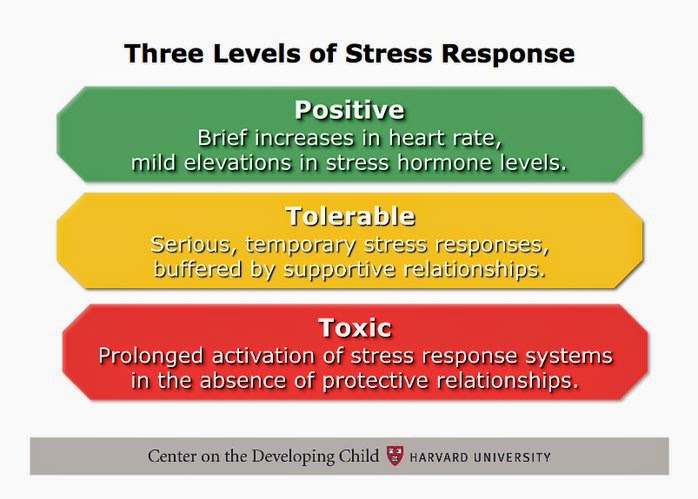

The National Scientific Council on the Developing Child has identified three types of psychological stress that can affect a child’s development2:

Positive stress

Adverse experiences that are short-lived create positive stress, called eustress. Most everyday stress is positive stress. It is normal in daily life. Young children may experience it when they meet a new relative, go to a new daycare, have a toy taken away from them, or attend the first day of school.

Most everyday stress is positive stress. It is normal in daily life. Young children may experience it when they meet a new relative, go to a new daycare, have a toy taken away from them, or attend the first day of school.

Children can learn coping skills to manage and overcome positive stress with the support of caring adults. A child’s ability to cope with this kind of stress is crucial to their healthy development.

Tolerable stress

Tolerable stress refers to adverse experiences that are still relatively short-lived but are more intense.

Examples include the death of a loved one, a natural disaster, a frightful accident, and significant disruptions such as moving to a new city or the separation of parents.

This type of stress can be tolerated if the child has the support of a caring adult. It is possible for tolerable stress in early childhood to improve the child’s development if it becomes positive stress. But this can only happen with adequate adult support. If a child doesn’t receive enough support, even stress that should be tolerable can become toxic and cause long-term health problems discussed below.

If a child doesn’t receive enough support, even stress that should be tolerable can become toxic and cause long-term health problems discussed below.

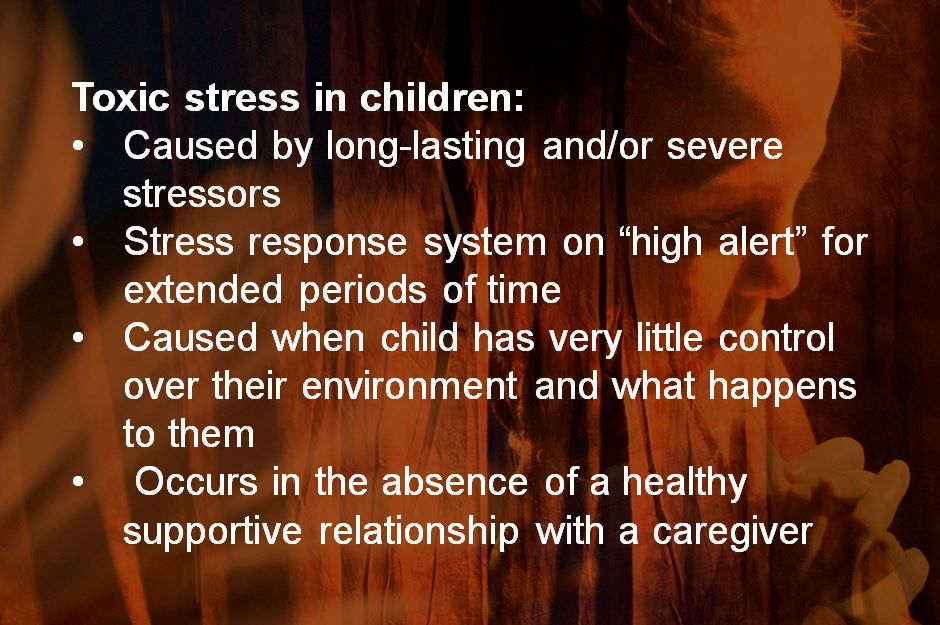

Toxic stress

Adverse childhood experiences (ACE) that last for weeks, months, or even years create stress that is toxic.

Examples of chronic stress include child maltreatment, such as physical abuse, emotional abuse, sexual abuse, and neglect.

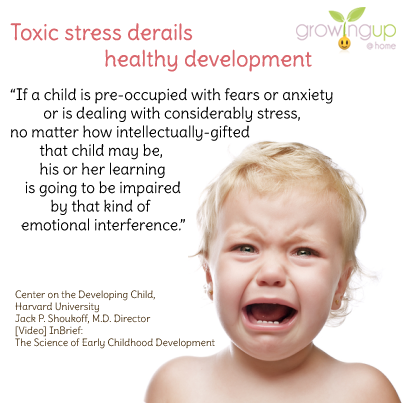

Children cannot effectively manage this type of stress on their own. When a young child’s stress response systems are activated for long periods of time, permanent changes can take place in the developing brain.

Toxic stress is bad news for children’s development.

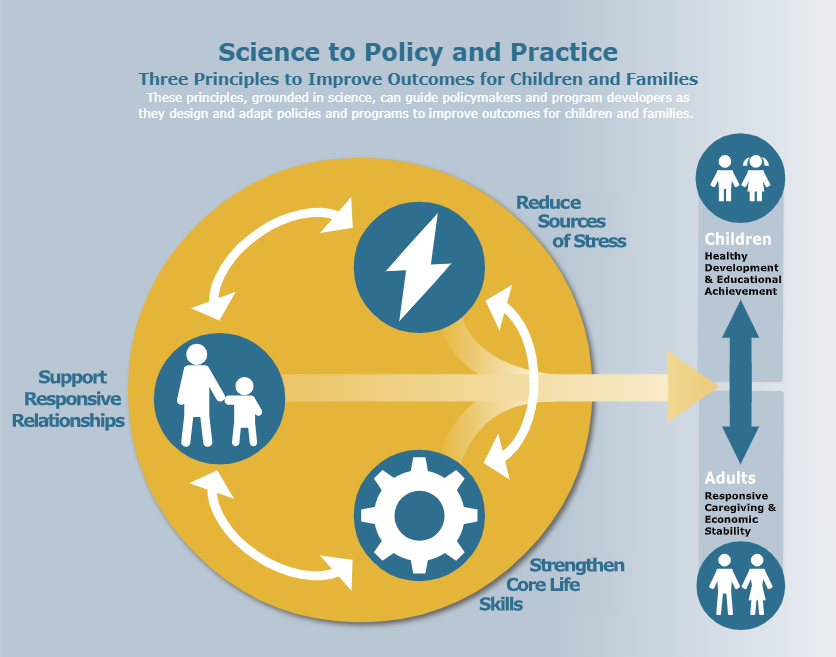

But the good news is caring adults and supportive environments can protect a child from the negative effects of toxic stress. An environment of supportive relationships can bring children’s stress response system back to its normal state.

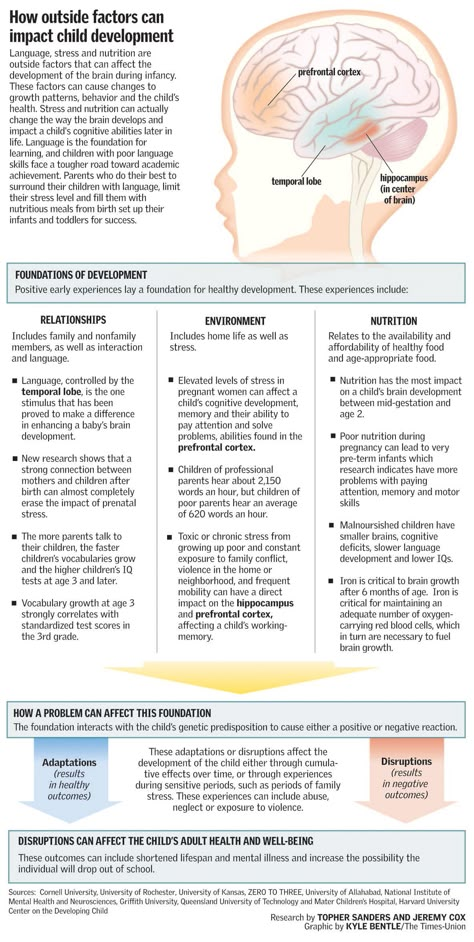

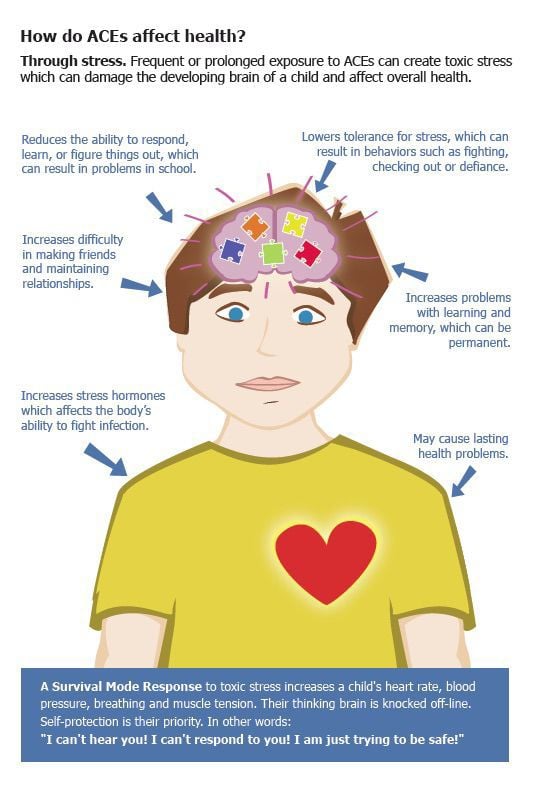

Effects of Stress On Brain Development

Stress is a natural and inevitable part of a child’s life. Fetuses experience stress even before birth.

Fetuses experience stress even before birth.

So how can toxic stress impact brain development?

Some amount of stress is essential for human survival. It helps children develop the skills they will need to cope with new and potentially dangerous situations throughout life.

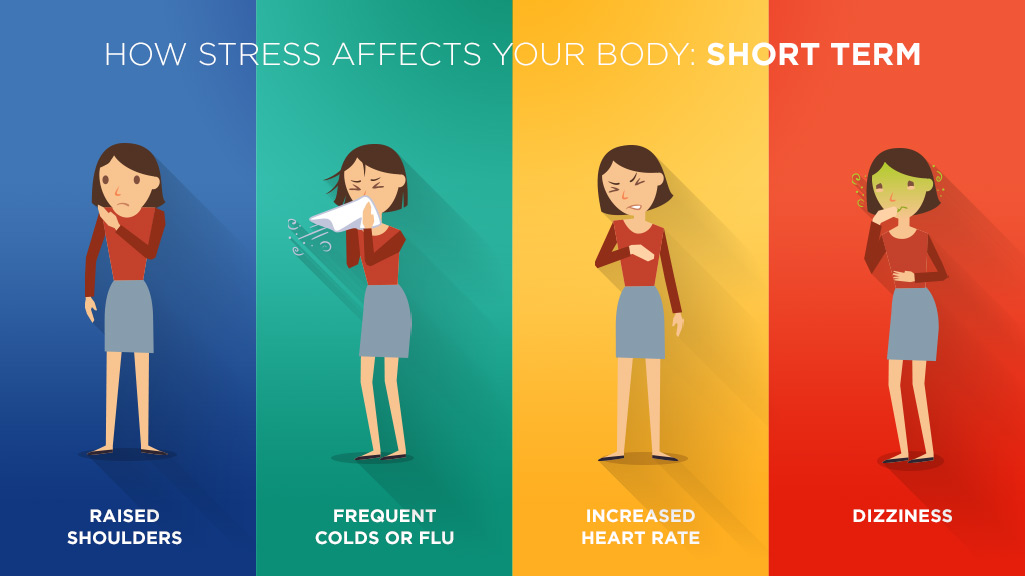

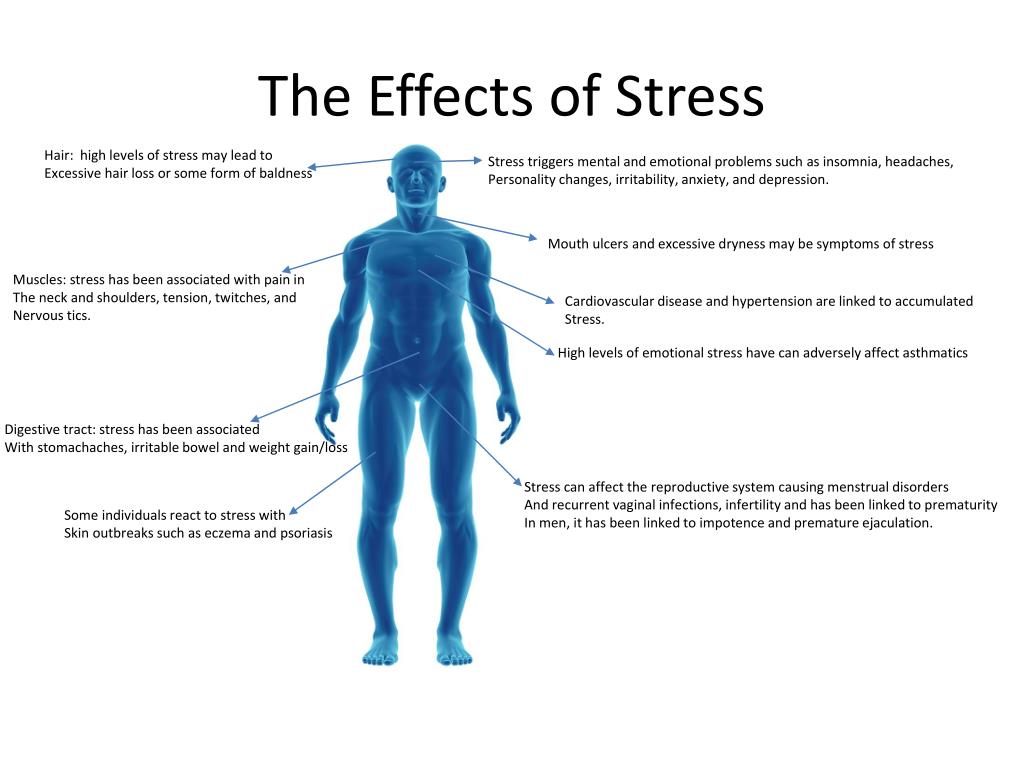

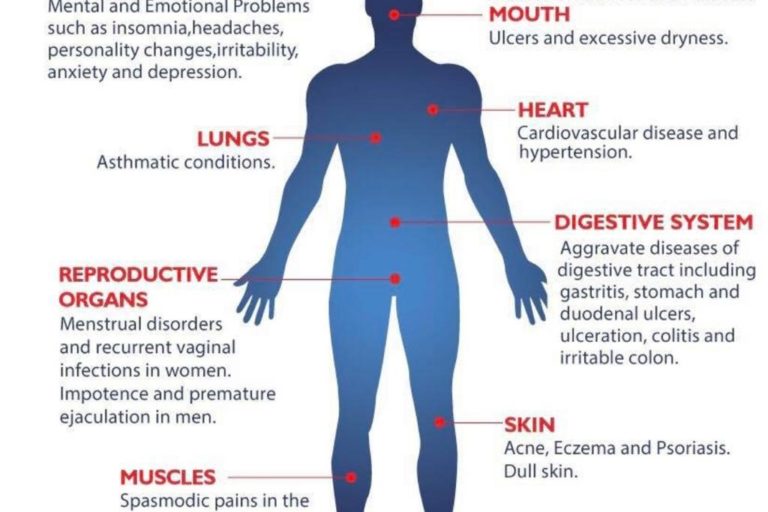

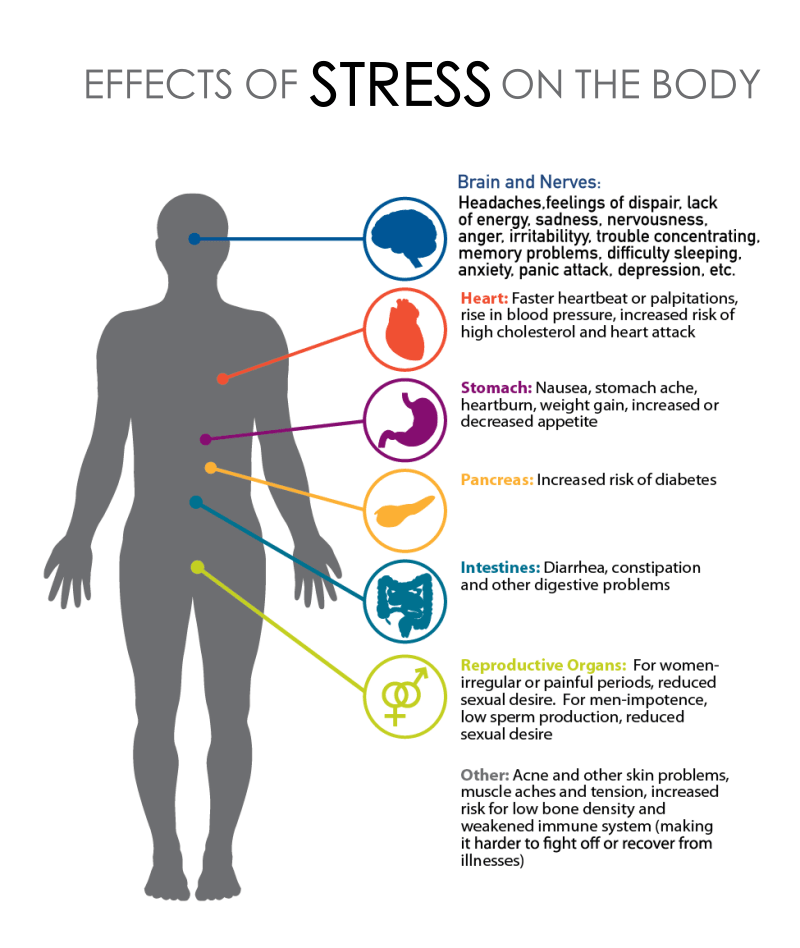

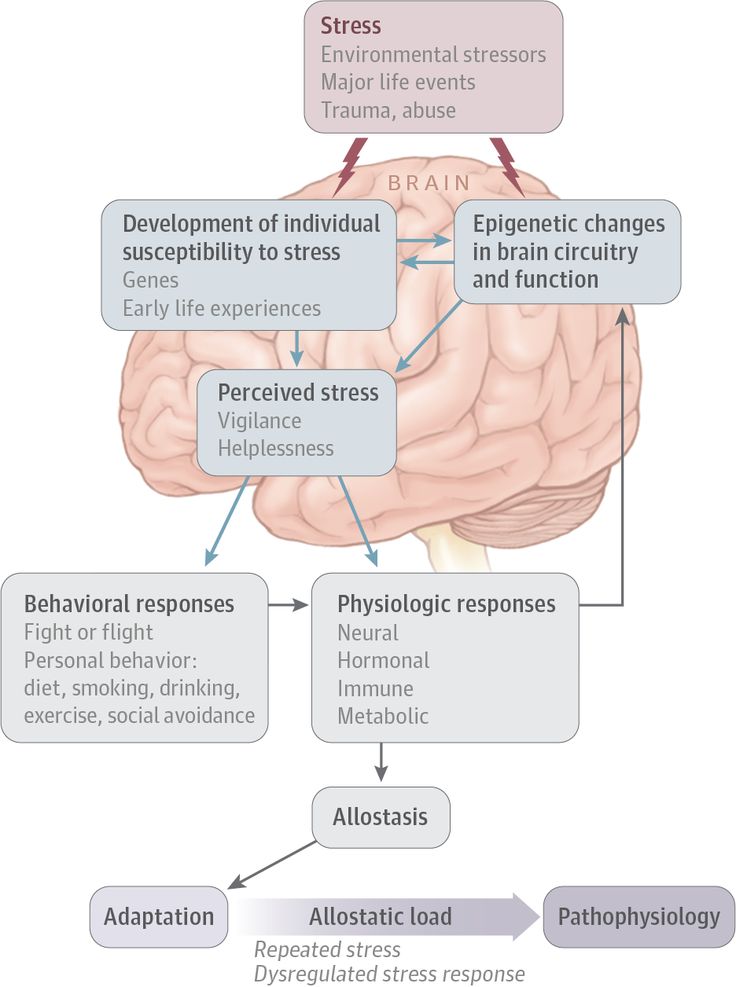

Stressful situations activate the body’s alert systems. The resulting fight-or-flight response generates physiologic effects such as an increase in respiration, heart rate, blood pressure, overall oxygen consumption, and the release of stress hormones.

The stress response to positive and tolerable stressors is transient. Once the stressor is gone, the body returns to its baseline state.

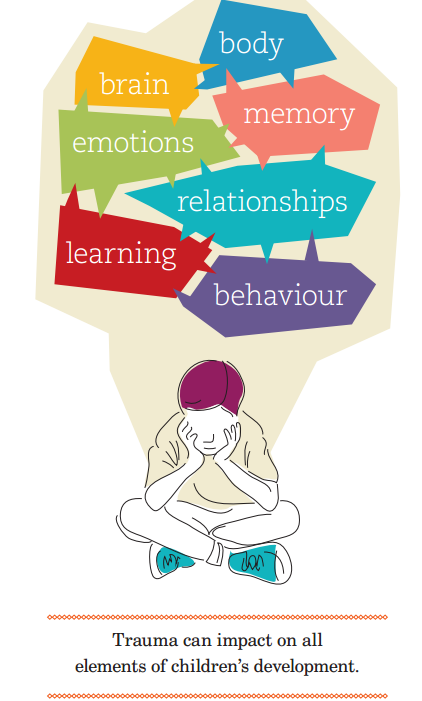

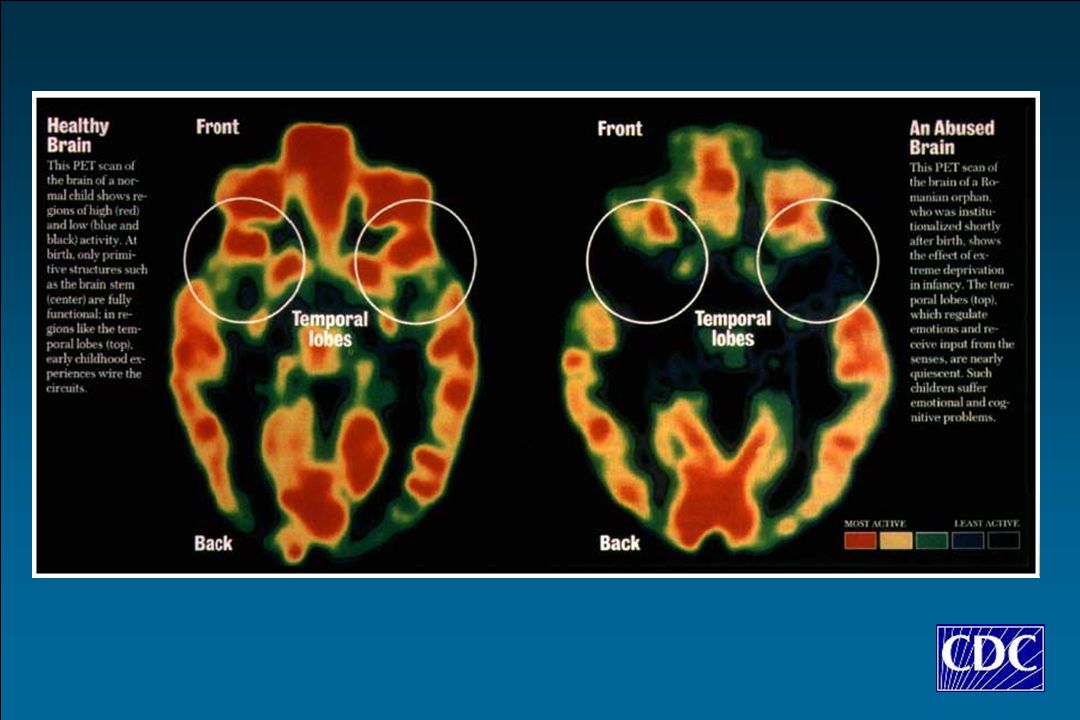

While positive and tolerable stress can promote a child’s development, toxic stress can damage various parts of the brain’s architecture3. The adverse impact of stress on a developing brain includes the following.

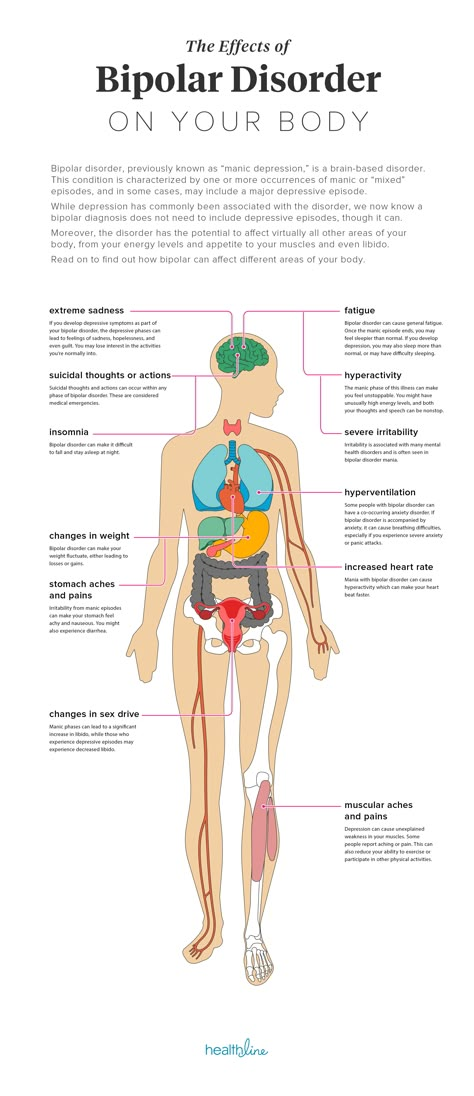

Impaired Cognition, Learning, And Memory

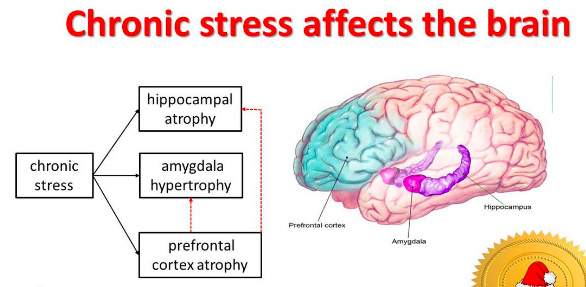

Toxic stress results in an increased release of stress hormones, such as cortisol. Sustained high cortisol levels can cause the learning and memory center (hippocampus)3, and the executive function center (prefrontal cortex)4 to shrink, impairing the child’s cognitive development. The resulting cognitive deficits and poor impulse control can continue into adulthood5.

Sustained high cortisol levels can cause the learning and memory center (hippocampus)3, and the executive function center (prefrontal cortex)4 to shrink, impairing the child’s cognitive development. The resulting cognitive deficits and poor impulse control can continue into adulthood5.

Overactive Stress Response

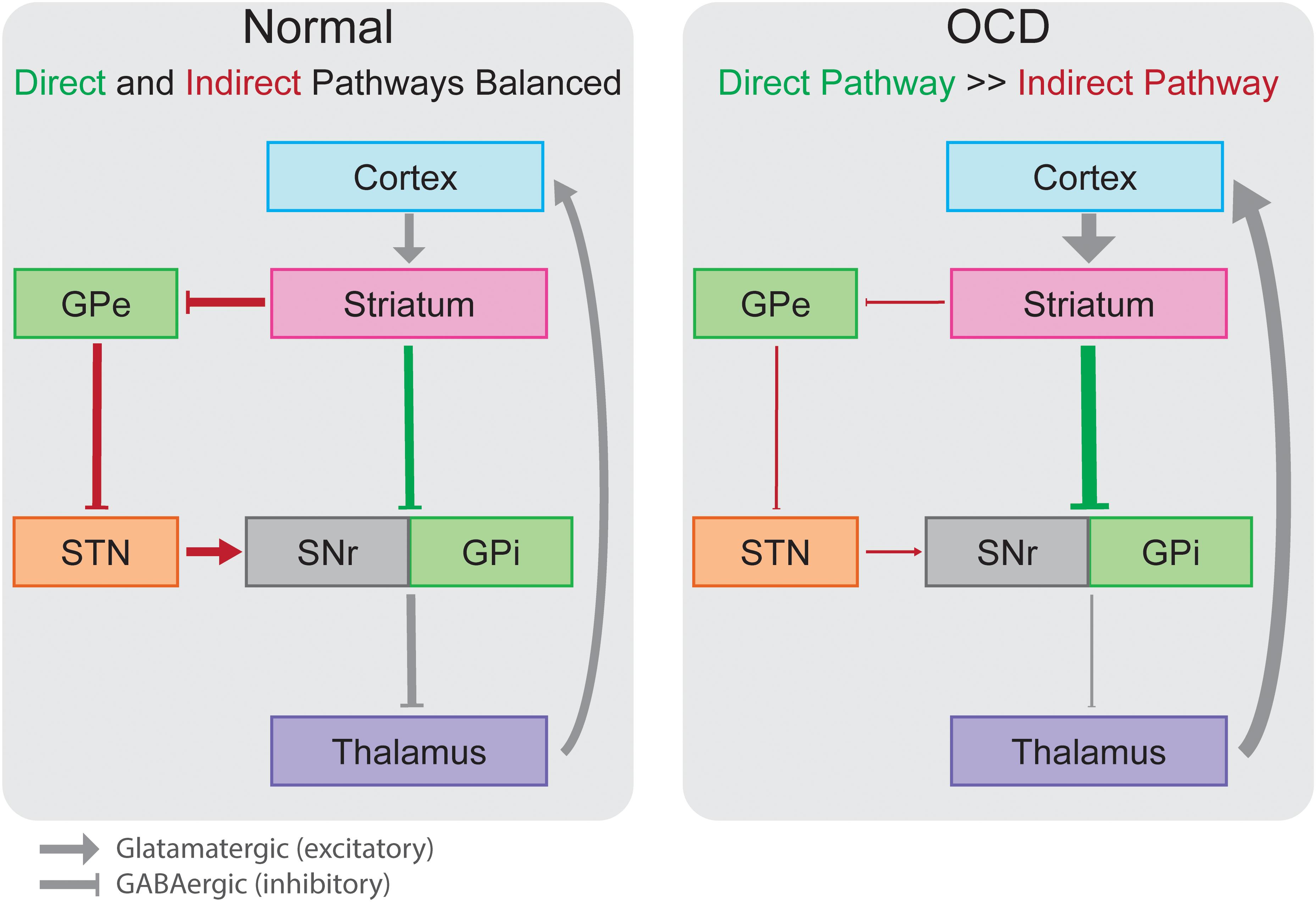

Repetitive and prolonged activation of stress response systems causes the emotional center in the brain (limbic system) to grow and become overactive. As a result, children who grow up with toxic stress are more anxious6 or aggressive7. They often suffer from emotional dysregulation8.

Mental Disorders

Extensive empirical data shows that toxic stress can lead to mental illness later in life, including somatic disorder, hallucinations, anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and suicide attempts.

Dysregulated Immunity

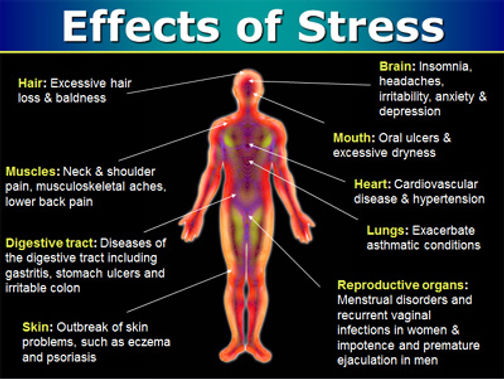

Toxic stress doesn’t only hurt the brain. It can harm physical health as well.

It can harm physical health as well.

The stress hormone, cortisol, released in stressful situations can suppress the immune system, leaving an individual more susceptible to infectious diseases and chronic medical conditions9.

Well-being

Children who grow up with toxic stress are at a higher risk for chronic health conditions such as heart disease. They tend to have a lower sense of well-being, more work-related problems, and premature death by as much as 20 years earlier8.

Toxic stress is very damaging to a child’s physical and mental health. Stress in early childhood can have serious consequences on the child’s lifelong health.

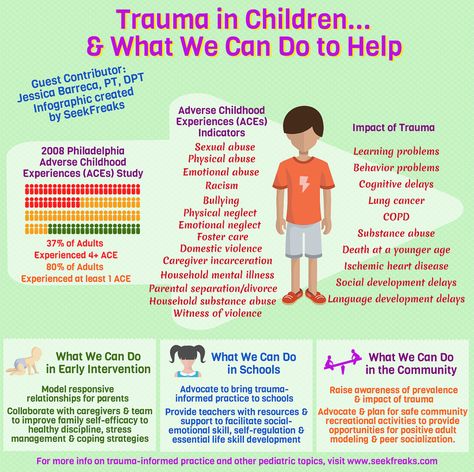

What Types of Stressors Can Lead To Toxic Stress

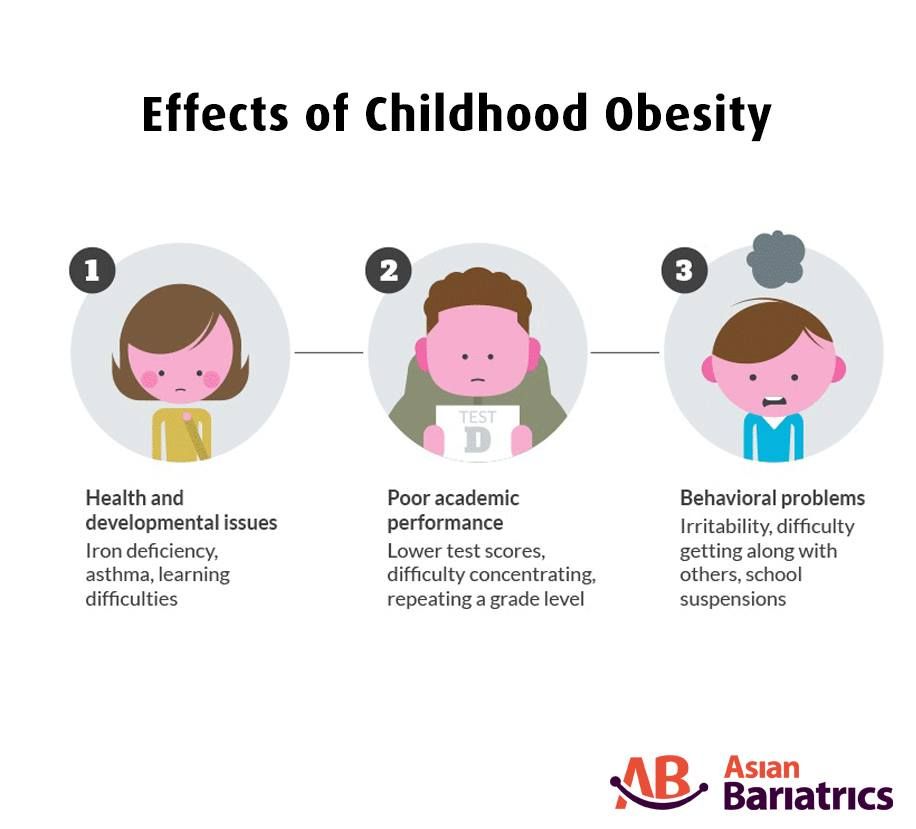

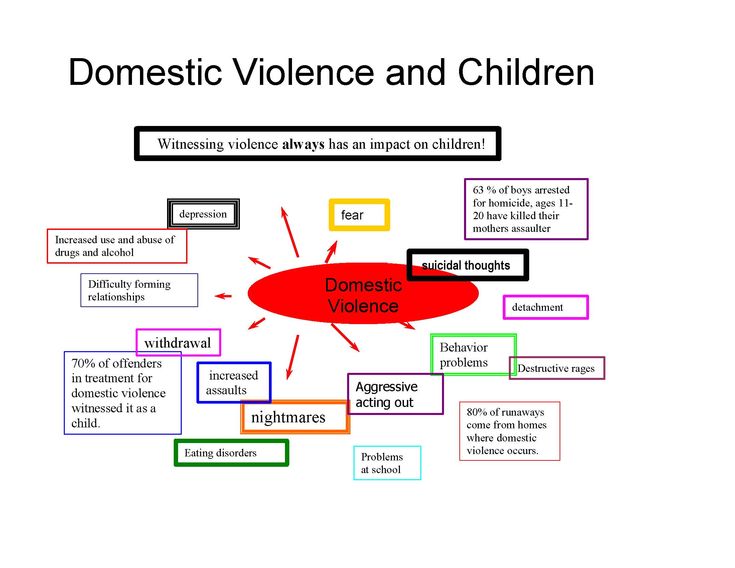

Children’s maltreatment is a leading cause of toxic stress. Maltreatment can take many forms, including physical, psychological, and sexual abuse.

Research shows that there are an estimated 8,755,000 child victims in this country. That means over 1 out of 7 children between the ages of 2 and 17 years have experienced maltreatment2.

However, severe child maltreatment is not the only source of toxic stress. Dysfunctional families, caregiver substance abuse, family economic hardship, domestic abuse, bullying, and food insecurity can also result in toxic stress10.

Toxic stress occurs when a child experiences severe, prolonged, or repetitive adversity and lacks the necessary nurturing or support of a caregiver to prevent an abnormal stress response11.

Exposure to less severe yet chronic, ongoing daily stress can also be toxic to children.

These daily stressors include exposure to a family filled with conflict and aggression and relationships that are cold and unsupportive.

When a child experiences toxic stress, their stress response system is activated and their body cannot fully recover by itself. Therefore, whether or not they are abusive, repeated hostility, unsupportive or negative interactions in the family trigger the stress response the same way.

That’s why these stressors are toxic, and they lay the foundation for long-term physical and mental health problems10.

The Difference Between Toxic And Tolerable Stress

There is a crucial difference between mild and intermittent stressors of daily life and moderate, but chronic, toxic stress.

Failure, disappointment, and rejection are inevitable for children, and kids should not be shielded from them entirely. Mild, intermittent stressors enhance the development of healthy stress response systems.

However, toxic stressors often include sustained family hostility, a lack of warmth among family members, or under-resourced schools and neighborhoods.

Yelling and arguing are common in some families. Most of them are not abusive or extreme in nature. However, they can still be toxic because the negative impacts of stress are not determined by an objective standard, but by the person who experiences them.

For little kids, even minor conflicts can be significant. They experience them differently from grownups. Children experience toxic stress when parents use “tough love” regularly.

The helicopter parents, on the other hand, shield their children from any adversity, thus preventing them from flexing their stress-tolerance muscles.

Final Thoughts On Adverse Effects Of Stress On Child Development

Scientists have found that having safe, stable, and nurturing relationships with caregivers can protect a child from the toxic effects of stress. These relationships keep children safe from physical harm and emotional problems. They provide predictability and consistency in the child’s environment. Close parent-child relationships also nurture a child’s developing self-confidence and sense of self-worth12.

References

-

1.

Huether G. Stress and the adaptive self‐organization of neuronal connectivity during early childhood.

Int j dev neurosci. Published online June 1998:297-306. doi:10.1016/s0736-5748(98)00023-9

Int j dev neurosci. Published online June 1998:297-306. doi:10.1016/s0736-5748(98)00023-9 -

2.

Middlebrooks JS, Audage NC. The Effects of Childhood Stress on Health Across the Lifespan. Published online 2008. doi:10.13016/NERG-FXLD

-

3.

Sheline YI. Neuroimaging studies of mood disorder effects on the brain. Biological Psychiatry. Published online August 2003:338-352. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00347-0

-

4.

Drevets WC, Price JL, Simpson JR Jr, et al. Subgenual prefrontal cortex abnormalities in mood disorders. Nature. Published online April 1997:824-827. doi:10.1038/386824a0

-

5.

Andreescu C, Butters MA, Begley A, et al. Gray Matter Changes in Late Life Depression—a Structural MRI Analysis. Neuropsychopharmacol. Published online December 12, 2007:2566-2572. doi:10.1038/sj.npp.1301655

-

6.

McEwen BS. The ever-changing brain: Cellular and molecular mechanisms for the effects of stressful experiences.

Devel Neurobio. Published online May 14, 2012:878-890. doi:10.1002/dneu.20968

Devel Neurobio. Published online May 14, 2012:878-890. doi:10.1002/dneu.20968 -

7.

Davidson RJ, McEwen BS. Social influences on neuroplasticity: stress and interventions to promote well-being. Nat Neurosci. Published online April 15, 2012:689-695. doi:10.1038/nn.3093

-

8.

Oral R, Ramirez M, Coohey C, et al. Adverse childhood experiences and trauma informed care: the future of health care. Pediatr Res. Published online October 13, 2015:227-233. doi:10.1038/pr.2015.197

-

9.

Morey JN, Boggero IA, Scott AB, Segerstrom SC. Current directions in stress and human immune function. Current Opinion in Psychology. Published online October 2015:13-17. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.03.007

-

10.

Odgers CL, Jaffee SR. Routine Versus Catastrophic Influences on the Developing Child. Annu Rev Public Health. Published online March 18, 2013:29-48. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-031912-114447

-

11.

Franke H. Toxic Stress: Effects, Prevention and Treatment. Children. Published online November 3, 2014:390-402. doi:10.3390/children1030390

-

12.

Shonkoff JP. Protecting Brains, Not Simply Stimulating Minds. Science. Published online August 18, 2011:982-983. doi:10.1126/science.1206014

Stress in a child and ways to avoid it

What is stress

Stress is a non-specific response of the body to any requirements presented to it. This is the reaction of the nervous system to a variety of physical, mental and emotional stimuli.

Stress itself is important in terms of human evolution and survival. But do not confuse this type of stress with chronic, which can be the root cause of a number of physical and mental illnesses.

We are used to the fact that stress is a phenomenon of the adult world. But today, children have a huge burden of responsibilities - school homework, important tests, preparation for which takes place in the mode of intimidation from teachers and, sometimes, parents, the need to comply with imposed standards for academic performance, and much more. In a state of constant pressure, children are also stressed.

In a state of constant pressure, children are also stressed.

Sometimes the symptoms are mild, so it's important to take care of your child to avoid chronic stress.

In this article we will look at the dangers of stress and what causes it. And also try to figure out how to help children who are already stressed.

Stages of stress

Stress does not manifest itself immediately, but consists of three stages, which manifest themselves in increasing order.

1. Primary anxiety (at this stage, children often withdraw into themselves, experiencing unusual melancholy and anxiety, physical changes still do not affect the child, but distrust of the people around them is manifested).

2. Period of resistance (at this time the child's psyche resists the experienced stress, tries to force out memories of a bad event, which is accompanied by a feeling of constant fatigue).

3. Exhaustion (moral exhaustion from stress turns into physical exhaustion, aggression or apathy is caused by the fact that the nervous system ceases to control emotions).

Exhaustion (moral exhaustion from stress turns into physical exhaustion, aggression or apathy is caused by the fact that the nervous system ceases to control emotions).

Each stage is characterized by an increasingly depressed emotional state, and prolonged stress can eventually turn into depression.

Causes of child stress

)

- Constant reproaches from parents, close relatives or teachers

- Bullying (peer bullying)

- Sudden change of routine or daily routine

- Beginning and end of the school year

- Exams and preparation for them

- Passion for aggressive computer games

- Lack of important vitamins and microelements (determined by the attending physician based on a series of tests)

Stress can occur even in children under one year old. For its cause, it is enough to change the diet, the mother goes to work, going to a nursery, a kindergarten, the appearance of a nanny, a strong fright or a long illness, as well as a quarrel between the parents.

Signs of stress in children

It is very important to recognize stress early and not ignore its signs. Stress in children can be identified by a number of symptoms:

- Frequent mood swings

- Aggression

- Sleep disturbance

- Enuresis from a spoon only with the help of parents, etc.)

Frequent headaches, abdominal pain and other physical discomfort people and situations, feigning diseases against this background)

In babies, bad habits can be added to these dangerous signs - thumb sucking, nail biting, picking your nose for no reason, etc. In older children, this is often an inadequate aggressive reaction.

Effects of stress on a child

How does stress affect a child? Under the influence of stress, the risk of cardiovascular diseases increases by 4 times. Various chronic diseases are exacerbated, self-control worsens.

Chronic childhood stress can lead to a number of different mental illnesses in adulthood. After all, most disorders in adults are associated with childhood phobias and psychological trauma.

After all, most disorders in adults are associated with childhood phobias and psychological trauma.

Treatment of stress in children

How can a child deal with stress? The child will not be able to cope with stress on their own. Help from parents and professionals is a must. Treatment is varied, depending on the condition of the child and the capabilities of the parents.

Help from parents themselves . You can start by tracking down and eliminating the source of stress. Become a support for your child, give him the confidence to support him in any situation. Let him vent his emotions. Talk about his experiences together. Raise his self-esteem. With young children, work through stressful situations through play.

Therapist . If the parents have eliminated all stressful sources, but the child is already at the “point of no return”, you should contact your doctor, who will give directions for various body examinations and, most likely, refer you to a neurologist or psychologist.

Psychotherapy . If you have reached this stage, do not worry. A psychologist and even a child psychiatrist will not put an end to the future of your child, but will only help him get out of this situation with minimal loss to health. The help of a psychiatrist is not necessarily a drug treatment that will simply relieve the symptoms that are disturbing at the moment. In any case, a new regimen will be recommended, which will prevent further stress.

Physiotherapy . As supportive procedures, the doctor may prescribe massages, swimming, taking therapeutic baths, and dietary nutrition.

Prevention of stress in a child

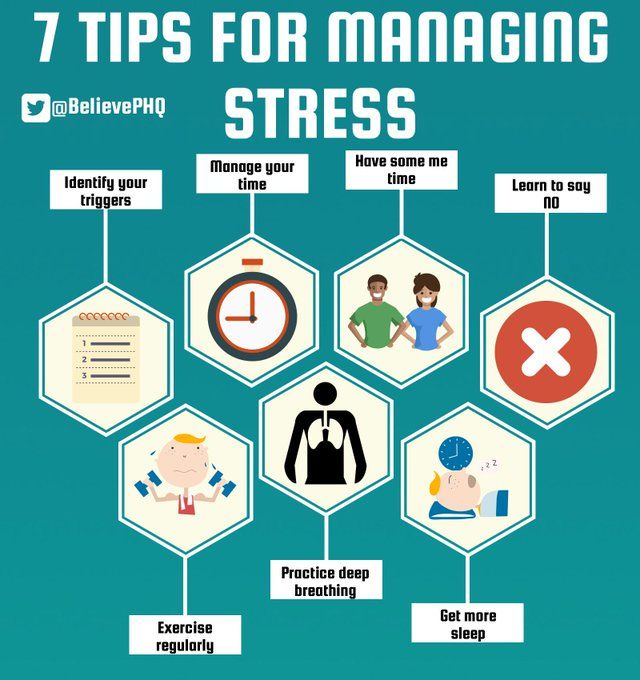

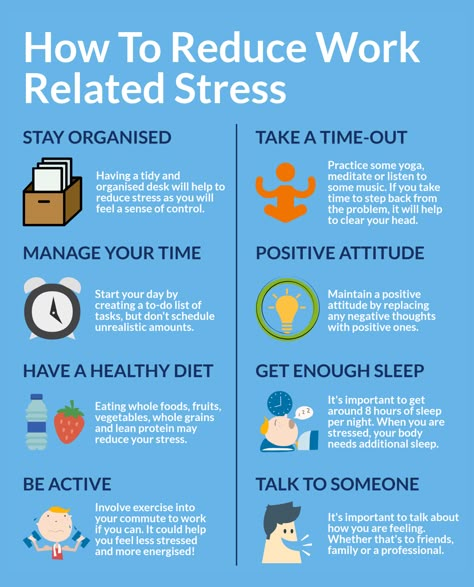

It is very important to develop resistance to stress. The best prevention of stress in children is regular rest, a healthy regimen, and physical education.

Sleep hygiene should be observed - let the child go to bed and wake up at the same time; going to bed should not be in an overexcited or upset state; you need to sleep a sufficient number of hours and continuously; before going to bed, you can take a cool or warm shower to relax the body; do not read or play in bed, especially before going to bed; limit computer games and exercise in the evening.

One of the most important components is physical activity. It helps children to increase stress resistance and relieves excessive emotional stress. Try to have various workouts present in your child's life at least 3 times a week for 30-40 minutes. There can be a lot of options, the most popular and affordable are outdoor walks (especially in the forest and park), swimming in the pool, cycling, dancing, etc. Yoga classes for children are also becoming popular, which will help strengthen the musculoskeletal system, improve stretching and posture. The most important thing is to make classes regular.

Another component of stress prevention is a balanced diet, which contains all the necessary vitamins and microelements.

If the mother is happy and calm, the child will most likely also be in a state of harmony. The model of behavior the child copies first of all from his family. Take a closer look at yourself before sounding the alarm and taking your child to a specialist.

| Note: Will improve communication skills, creative thinking robotics for children. It is easy to buy courses on the development and animation of robots in the POLYCENT educational center. We conduct aeromodelling courses, where children learn the basics of technical modeling. |

Stress and its consequences in children of the first years of life Trushkina

Stress and its consequences in children of the first years of life

Trushkina Svetlana Valerievna - Candidate of Psychological Sciences, Leading Researcher of the Department of Medical Psychology of the Federal State Budgetary Scientific Institution "Scientific Center for Mental Health" (Moscow, Russia), [email protected]

Introduction. The scientific review is devoted to the problem of the influence of severe or prolonged stress on children in the first years of life, which is little studied both in psychiatry and in medical psychology. The study is based on a comparison of the clinical manifestations of stress disorders in young children, described in modern medical and psychological literature, with the symptoms of various stress disorders in adults, reflected in the International Classification of Diseases ICD-10.

The study is based on a comparison of the clinical manifestations of stress disorders in young children, described in modern medical and psychological literature, with the symptoms of various stress disorders in adults, reflected in the International Classification of Diseases ICD-10.

Results. The review shows that infants and young children suffer from stress in the same way as adults or older children, and they can also be diagnosed with a stress disorder. At the same time, specific manifestations of disorders and stressful events may differ in them. Such specific age-related symptoms of stress disorders as post-traumatic play, separation anxiety, developmental regression, etc. are considered. its manifestations and consequences. It is emphasized that the presence of a stress disorder in a child can adversely affect his development, affecting cognitive processes and social relations. The issue of the fundamental importance of mother-child and wider family relations for the emergence and course of stress disorders in children of the first years of life is highlighted, and the need to organize therapeutic assistance for both members of the mother-child dyad is shown. Practical significance. The review is addressed to specialists of preschool education institutions and aims to inform them about the signs of stress disorders in children of the first years of life, so that they can initially recognize them and initiate family referral for specialized help to a child psychiatrist or medical psychologist.

Practical significance. The review is addressed to specialists of preschool education institutions and aims to inform them about the signs of stress disorders in children of the first years of life, so that they can initially recognize them and initiate family referral for specialized help to a child psychiatrist or medical psychologist.

Key words: early childhood, PTSD, adjustment disorders, post-traumatic play, mother-child dyad.

For citation: Trushkina S.V. Stress and its consequences in children of the first years of life // Modern preschool education. - 2018. - No. 3 (85). - S. 24-31. Article materials received on 11/17/2017

In the modern world, an increasing number of specialists are turning to the topic of mental traumatization of a child as a result of experiencing a high degree of stress. This interest extends not only to children of school or adolescence, but also to preschoolers and children of early and even infant age. It should be noted that the problem of the occurrence of stress disorders at these ages was not immediately recognized in professional circles. For quite a long time it was believed that the high plasticity of the psyche

For quite a long time it was believed that the high plasticity of the psyche

prevents the formation of stable cognitive or emotional disorders in a small child due to psychological trauma. It has been suggested that, along with insufficient development of long-term memory, this plasticity allows an infant or two- or three-year-old child to avoid the long-term effects of severe stress, which distinguishes them from adults or older children. At the same time, ideas about early psychic trauma were being developed in psychoanalytic circles.0009

UDC 159.922.73 DOI: 10.2441 1/1997-9657-2018-00011 Stress and its Consequences for Children in the First Years of their Life Svetlana V. Trushkina, PhD of Psychology, Leading Researcher of the Department of Medicine Psychology in the "Mental Health Research Center", Moscow, Russia, [email protected] The scientific review is devoted to the issue of the influence of strong or prolonged stress on children in the first years of life, which is poorly understood both in psychiatry and in medical psychology. The study is based on a comparison of the manifestations of stress disorders in young children, described in modern medical and psychological literature, with the symptoms of various stress disorders in adults, as reflected in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10). results. The survey shows that infants and young children suffer from stressful actions in the same way as adults or older children, and they can also be diagnosed with a stress disorder. In this case, specific manifestations of disorders and stressors within them may differ. Such specific age-related symptoms of stress disorders as a post-traumatic game, separation anxiety, regression in development, etc. are considered. It is shown that the mental health disorders in young children, arising from different types of stressors - a sudden traumatic event of high intensity or chronic psychotraumatic situation, differ in their manifestations and consequences. It is emphasized that the presence of a stress disorder in a child can adversely affect their development, impacting their cognitive processes and social relations.

The study is based on a comparison of the manifestations of stress disorders in young children, described in modern medical and psychological literature, with the symptoms of various stress disorders in adults, as reflected in the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision (ICD-10). results. The survey shows that infants and young children suffer from stressful actions in the same way as adults or older children, and they can also be diagnosed with a stress disorder. In this case, specific manifestations of disorders and stressors within them may differ. Such specific age-related symptoms of stress disorders as a post-traumatic game, separation anxiety, regression in development, etc. are considered. It is shown that the mental health disorders in young children, arising from different types of stressors - a sudden traumatic event of high intensity or chronic psychotraumatic situation, differ in their manifestations and consequences. It is emphasized that the presence of a stress disorder in a child can adversely affect their development, impacting their cognitive processes and social relations. The importance of mother-child and wider family relationships for the emergence of stress disorders and its progression in children of the first years of life is illuminated, and the need for the provision of therapeutic care for both members of the mother-child dyad is also shown. practical significance. The review is addressed to specialists in institutions of preschool education and aims to inform them about the signs of stress disorders in children in the first years of life, so that they can recognize them and initiate a family appeal for specialized assistance to a child psychiatrist or a medical psychologist. Keywords: early childhood, adjustment disorder, post-traumatic game, mother-child dyad. For citation: Trushkina S.V. (2018). Stress and its Consequences in Children of the First Years of the Life. Preschool Education Today. 12:3, 24-31 (in Russian). Original manuscript received 11/17/2017

The importance of mother-child and wider family relationships for the emergence of stress disorders and its progression in children of the first years of life is illuminated, and the need for the provision of therapeutic care for both members of the mother-child dyad is also shown. practical significance. The review is addressed to specialists in institutions of preschool education and aims to inform them about the signs of stress disorders in children in the first years of life, so that they can recognize them and initiate a family appeal for specialized assistance to a child psychiatrist or a medical psychologist. Keywords: early childhood, adjustment disorder, post-traumatic game, mother-child dyad. For citation: Trushkina S.V. (2018). Stress and its Consequences in Children of the First Years of the Life. Preschool Education Today. 12:3, 24-31 (in Russian). Original manuscript received 11/17/2017

me due to events inevitable in the life of every child - birth, weaning, relatively long separation from the mother. Scientific research and observations from clinical practice over the past decades are gradually clarifying the problem of stress disorders in children of the first years of life, but complete certainty in these matters has not yet been achieved.

Scientific research and observations from clinical practice over the past decades are gradually clarifying the problem of stress disorders in children of the first years of life, but complete certainty in these matters has not yet been achieved.

symptoms of stress disorders in young children

As a rule, the study of severe stress disorders in young children starts from knowledge of similar disorders in adults. Thus, according to modern concepts, severe stress can lead to the development of both acute and chronic disease states in a person. In addition, the so-called adaptation disorders are distinguished, which develop in response to the impact of a less intense, but prolonged in time and associated with

significant life changes stressful situation.

Acute stress disorder develops immediately following an unusually severe physical or mental stressor and subsides within days or even hours. Its first manifestations may include conditions characteristic of mental shock - stunnedness, narrowing of the scope of consciousness and attention, disorientation, the impossibility of full awareness of the events taking place and the causes that caused them. A little later, it is possible to develop an emotional “withdrawal” reaction from a traumatic situation in the form of a stupor or, conversely, agitation, hyperactivity and chaotic behavior.

A little later, it is possible to develop an emotional “withdrawal” reaction from a traumatic situation in the form of a stupor or, conversely, agitation, hyperactivity and chaotic behavior.

Another form of the disorder, often defined as chronic, is called post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The appearance of its symptoms is often preceded by a latent (ie, latent, asymptomatic) period after injury, ranging from several weeks to several months, and the course of the disease itself can drag on for a long, up to several years, period. Typical manifestations of PTSD can be classified into three main groups. The first includes episodes of experiences of a traumatic event that are repeated in one form or another. These can be endlessly recurring memories, obsessive thoughts, nightmares or so-called flashback symptoms, i.e. painfully acute flashes of a person's experience of the circumstances of a past trauma, suddenly playing out before his "inner eye". The second group of symptoms forms a specific constantly present emotional background, characterized by general alienation, isolation from other people, inhibition of reactions or a state of unresponsiveness to what is happening around. In addition, a person may actively seek to avoid places, people or situations that can remind him of the events that shocked him. The third group includes states of overexcitation and constant alertness that have not previously taken place, manifested in the form of insomnia, an increased reaction to fear, panic attacks, various symptoms of high anxiety and depression, up to thoughts of suicide. In severe chronic cases, PTSD can lead to permanent changes in a person's personality (International Classification of Diseases ICD-10; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5).

In addition, a person may actively seek to avoid places, people or situations that can remind him of the events that shocked him. The third group includes states of overexcitation and constant alertness that have not previously taken place, manifested in the form of insomnia, an increased reaction to fear, panic attacks, various symptoms of high anxiety and depression, up to thoughts of suicide. In severe chronic cases, PTSD can lead to permanent changes in a person's personality (International Classification of Diseases ICD-10; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, DSM-5).

In children of the first years of life, as observations have shown, the symptoms of PTSD generally fall under the headings allocated for adults, however, they have their own, quite bright, age specificity.

Thus, the re-experiencing of a traumatic event in a young child often takes the form of post-traumatic play. It is characterized by the reproduction by the child of certain aspects of the trauma in actions with objects, toys or people. Compared to ordinary children's play, it is more literal, devoid of creative play, less complex and free. The child simply repeats traumatic events or the circumstances that accompanied them over and over again in his actions, practically without introducing any variability into them. For example, a two-year-old boy bitten by a dog plays a scene several times a day in which he growls, snaps, then suddenly attacks and bites an adult. He does not comment on this game in any way and repeats

Compared to ordinary children's play, it is more literal, devoid of creative play, less complex and free. The child simply repeats traumatic events or the circumstances that accompanied them over and over again in his actions, practically without introducing any variability into them. For example, a two-year-old boy bitten by a dog plays a scene several times a day in which he growls, snaps, then suddenly attacks and bites an adult. He does not comment on this game in any way and repeats

the same scene with minimal differences. For comparison, another child who was also attacked by a dog, but who does not have symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, can also replay the event that frightened him many times, but at the same time he is much more free in choosing the details of the game plot, is able to vary its duration, introduce new characters and change the ending. As a result, after some time, a natural reaction of emotions of anxiety and fear occurs, the intensity of experiences fades, the game plot changes noticeably and ceases to be used by the child too often. Post-traumatic play as a painful symptom has an obsessive character; the child is not able to change it himself and reduce his emotional stress with its help (S: 0-3 2005).

Post-traumatic play as a painful symptom has an obsessive character; the child is not able to change it himself and reduce his emotional stress with its help (S: 0-3 2005).

Painful preoccupation with memories of trauma in children who have already mastered speech may also manifest itself in a less obvious way, for example, in the form of repeated statements about the event or endless questions about it. Thus, a child who has directly observed a death of a person under the wheels of a car can talk all the time only about cars and literally “stick” to their images in pictures or on the screen. At the same time, to an outside observer, this may seem only a manifestation of increased curiosity, and the suffering of the child may not be recognized even by close adults.

In other cases, on the contrary, a reminder of a traumatic event can cause a child to have clear physiological signs of intense distress - palpitations, trembling, sweating, indigestion, chest tightness, or difficulty breathing. Young children who are sufficiently fluent in speech can already (spontaneously or upon questioning) report these symptoms, as well as tell adults about their experiences and fears (Skoblo, Trushkina, 2016). A special channel that carries information about the difficult emotional state of a small child is his play behavior. For example, a girl busy playing with dolls, in response to the sound of a siren in the street, abruptly starts a fight between dolls, being overwhelmed by memories of a terrible quarrel between her parents and the ambulance that came after her. Similar behavior- 92005).

Young children who are sufficiently fluent in speech can already (spontaneously or upon questioning) report these symptoms, as well as tell adults about their experiences and fears (Skoblo, Trushkina, 2016). A special channel that carries information about the difficult emotional state of a small child is his play behavior. For example, a girl busy playing with dolls, in response to the sound of a siren in the street, abruptly starts a fight between dolls, being overwhelmed by memories of a terrible quarrel between her parents and the ambulance that came after her. Similar behavior- 92005).

The second group of PTSD symptoms - avoidance behavior and emotional isolation from people - in children of the first years of life manifests itself in the form of a noticeable increase in social distance with others, limitation of the range of emotional response, decrease in interest in previously significant activities: play, research, social contacts, routine daily employment. Just as in adults, children may experience avoidance of the activities, conversations, places, or people associated with the trauma. The child may begin to experience a blockage of spontaneous emotional responses. The reaction of emotional “withdrawal”, the difficulty in perceiving developmental stimuli that it causes, and the inhibition of emotional and behavioral responses to them, as a rule, noticeably affect the pace of the child’s mental development for the surrounding adults.

The child may begin to experience a blockage of spontaneous emotional responses. The reaction of emotional “withdrawal”, the difficulty in perceiving developmental stimuli that it causes, and the inhibition of emotional and behavioral responses to them, as a rule, noticeably affect the pace of the child’s mental development for the surrounding adults.

Symptoms of increased arousal and alertness include unexplained difficulty going to sleep, strong protests against going to bed, especially when alone, difficulty falling asleep, or recurring nocturnal awakenings associated with nightmares. After the trauma, increased irritability, shyness, outbursts of anger or extreme nervousness, tantrums, aggression towards peers, adults or animals, sexualized behavior (for example, excessive insistent interest in one's or someone else's genitals, masturbation, etc.) may appear. Difficulties in concentrating attention and organizing behavior are no less characteristic. Fears that did not exist before the traumatic event may appear, and their content is not necessarily associated with it. Separation anxiety is a specific age-related symptom. fear of even a short-term separation from a close adult, usually a mother. The kid can start violently protesting

Separation anxiety is a specific age-related symptom. fear of even a short-term separation from a close adult, usually a mother. The kid can start violently protesting

oppose her going even into the next room. Three-four-year-old children refuse to stay without a mother in a kindergarten or with relatives, fearing that without a mother they will be lost, they will be stolen or put in a hospital, that something terrible may happen to their parents in separation, that they will die, leave, forget about him, etc.

Children of infancy, early childhood and preschool age also have symptoms of stress disorders that do not belong to any of the three listed groups. Young children who have experienced traumatic events may temporarily lose previously acquired skills. This may refer to the development of motor skills, play or speech, skills of neatness and self-care, social interaction skills, etc. (Dobryakov, 2013; Dobryakov and Trushkina, 2015; Portnova, 2011; Portnova and Serebrovskaya, 2013; Scheeringa, 2009; Black, 2002). For example, a one and a half year old boy, whose mother was suddenly and for a long time hospitalized with a serious illness, began to move on all fours, although before that he had been walking confidently for several months.

For example, a one and a half year old boy, whose mother was suddenly and for a long time hospitalized with a serious illness, began to move on all fours, although before that he had been walking confidently for several months.

An attempt to best consider the specifics of clinical manifestations in young children when making a diagnosis of PTSD was made in the international Diagnostic Classification of Mental Health and Developmental Disorders in Infancy and Early Childhood (DC:0-5, 2016).

Types of stressors

Stressors, i.e. those circumstances or events that shocked him and which resulted in the development of a stress disorder. For adults, as a rule, natural or man-made disasters, wars, attacks, forced migration, all kinds of heavy losses (relatives, home, livelihood, social status, life meanings, prospects, etc.) and other events that threaten life and health. Not only people directly affected by the events are at risk of developing PTSD, but also those who witnessed them, as well as family members of the victims. Another recognized source of psychopathological changes in humans is chronic ill health.0009

Another recognized source of psychopathological changes in humans is chronic ill health.0009

irradiation that causes prolonged stress, even if this stress is not characterized by high intensity.

An infant or young child may be directly involved in events that include death, threat of death or serious injury to himself or others, threat to the psychological or physical integrity of himself or other people, or to be a witness to them. The stressor can be a sudden and unexpected event (eg, a car accident, earthquake, terrorist attack, animal attack), a series of related and expected events (eg, air raids), or a prolonged life situation (eg, living in a family where adults constantly fight and hit). each other, prolonged bullying or sexual use of a child) (Axis IV, DC:0-5, 2016). Research shows that for many children, different stressors often exist at the same time. The cumulative risk hypothesis developed in recent years suggests that the existence of a combination of stress factors is a more significant predictor for the subsequent mental traumatization of a child than individual stressors. For example, it is highly revealing that long-term psychiatric problems in a child are more likely to follow the loss of a parent through divorce than through death. This can be explained by the cumulative effect of stress on a child during a long-term traumatic situation, usually preceding the parents' divorce and often not ending for a long time after it. And while the death of a parent can be very hard on a child, scientific evidence suggests that, compared with divorce, the loss itself is much less likely to result in significant and long-term damage to his mental health (Goodman, Scott, 2008; McNeal, Amato, 1998).

For example, it is highly revealing that long-term psychiatric problems in a child are more likely to follow the loss of a parent through divorce than through death. This can be explained by the cumulative effect of stress on a child during a long-term traumatic situation, usually preceding the parents' divorce and often not ending for a long time after it. And while the death of a parent can be very hard on a child, scientific evidence suggests that, compared with divorce, the loss itself is much less likely to result in significant and long-term damage to his mental health (Goodman, Scott, 2008; McNeal, Amato, 1998).

In addition, for an infant and a small child, a fairly wide range of events and transitional moments can be a significant source of stress, sharply disrupting the usual course of his everyday life. Events that are quite normal for older members of the family can also act in this capacity: the birth of the next child, a move, the mother's return to work after a long parental leave,

the beginning of a visit to a kindergarten, placement with relatives during the rest of the parents, etc. .P. These transitional events, as well as chronic family distress, may not lead to acute stress reactions or PTSD, but to adjustment disorders, characterized mainly by emotional and behavioral disturbances in the child - high anxiety, irritability, prolonged despondency, stubborn resistance to going to bed, defiant behavior, outbursts of anger. It is important that only some children perceive these circumstances as a strong stress load, while other children make these transitions smoothly and adapt to new conditions quite easily (DC: 0-5, 2016; Goodman, Scott, 2008).

.P. These transitional events, as well as chronic family distress, may not lead to acute stress reactions or PTSD, but to adjustment disorders, characterized mainly by emotional and behavioral disturbances in the child - high anxiety, irritability, prolonged despondency, stubborn resistance to going to bed, defiant behavior, outbursts of anger. It is important that only some children perceive these circumstances as a strong stress load, while other children make these transitions smoothly and adapt to new conditions quite easily (DC: 0-5, 2016; Goodman, Scott, 2008).

Factors influencing the onset and course of stress disorders in children

Studies have shown that the degree of influence of stressful events on a child largely depends on three factors: the characteristics of the stressor, namely its intensity, duration and predictability; individual characteristics of the child's temperament and level of development, which determine the type of his emotional response and ability to adapt; the ability of close adults to serve as a protective buffer for the child under stress, i. e. if possible, protect him from treating what is happening as a terrible catastrophe and further help in regulating emotional manifestations (Dobryakov, 2013; Dobryakov, Trushkina, 2015; Portnova, 2011; Portnova, Serebrovskaya, 2013; DC: 0-5, 2016; Thomas , Chess, 1977). Here it is appropriate to recall the long-known “phenomenon of social exile”: in an unfamiliar situation, a small child seeks to determine the reaction of a close adult to it and then reacts in the same way (Mukhamedrakhimov, 2003). That is, if an adult in a critical situation finds the strength and courage not to openly show his fear, panic and helplessness to a small child, then the latter has a significantly increased chance of getting out of it with less loss to mental health. The family environment as a whole can also protect the child from stressful events and circumstances, providing

e. if possible, protect him from treating what is happening as a terrible catastrophe and further help in regulating emotional manifestations (Dobryakov, 2013; Dobryakov, Trushkina, 2015; Portnova, 2011; Portnova, Serebrovskaya, 2013; DC: 0-5, 2016; Thomas , Chess, 1977). Here it is appropriate to recall the long-known “phenomenon of social exile”: in an unfamiliar situation, a small child seeks to determine the reaction of a close adult to it and then reacts in the same way (Mukhamedrakhimov, 2003). That is, if an adult in a critical situation finds the strength and courage not to openly show his fear, panic and helplessness to a small child, then the latter has a significantly increased chance of getting out of it with less loss to mental health. The family environment as a whole can also protect the child from stressful events and circumstances, providing

him a sense of security and safety, and thereby reducing their influence. Children subtly observe how adults who are central to their lives relate to what is happening, and often learn by imitation, adopting the behavior and attitudes they observe. The extent to which a small child is protected from excessive anxiety and tension, in turn, affects the formation of his emotional self-regulation, trust in relationships with people and freedom in exploring the world around him.

The extent to which a small child is protected from excessive anxiety and tension, in turn, affects the formation of his emotional self-regulation, trust in relationships with people and freedom in exploring the world around him.

However, we must not forget that in many situations the mental health of an adult is also affected by severe stressors, that he may also experience the symptoms of acute stress disorder mentioned above or PTSD of varying severity. Data from a survey of families who have survived a severe stressful event indicate that there is a clear relationship between the severity of the conditions of the mother and the small child. The infant and young child is still very closely connected to the mother (or other primary caregiver), and this connection is manifested by a general emotional or even physiological response. Children of this age are capable of inducing (i.e., reproducing, reflecting) the symptoms of PTSD in the mother, who forms a single mother-child dyad with them. Anxiety and depressive disorders in a mother who experienced a traumatic event with her child, her behavioral disorders - refusal to interact with people, aggressiveness, hysteria - are undoubtedly factors that aggravate the child's condition and negatively affect his recovery and further development. Therefore, it is important to make a diagnosis and start working not only with the child affected by the stressful event, but also with his mother, and, if necessary, with other family members. The provision of medical and psychological assistance to a child in the first years of life with stress disorders should include a mandatory examination and treatment of an adult who is a figure of affection for him. In some cases, the improvement in the mental state of the mother, which occurred as a result of the treatment, can in itself cause a decrease in painful manifestations in her small child (Skoblo, Trushkina, 2016; Dobryakov, 2013; Dobryakov, Trushkina, 2015; Portnova, 2011; Portnova, Serebrovskaya, 2013).

Anxiety and depressive disorders in a mother who experienced a traumatic event with her child, her behavioral disorders - refusal to interact with people, aggressiveness, hysteria - are undoubtedly factors that aggravate the child's condition and negatively affect his recovery and further development. Therefore, it is important to make a diagnosis and start working not only with the child affected by the stressful event, but also with his mother, and, if necessary, with other family members. The provision of medical and psychological assistance to a child in the first years of life with stress disorders should include a mandatory examination and treatment of an adult who is a figure of affection for him. In some cases, the improvement in the mental state of the mother, which occurred as a result of the treatment, can in itself cause a decrease in painful manifestations in her small child (Skoblo, Trushkina, 2016; Dobryakov, 2013; Dobryakov, Trushkina, 2015; Portnova, 2011; Portnova, Serebrovskaya, 2013).

Conclusion

Thus, infants and young children suffer from the effects of severe stress in the same way as adults or older children, and they may also be diagnosed with a stress disorder. At the same time, stressful events and specific manifestations of disorders may differ in them. Children can be exposed to both a sudden stressor of unusual magnitude and a chronic traumatic situation, and there is evidence that the latter is more damaging for young children. The presence of a stress disorder in a child can adversely affect the course and quality of his development, affecting both cognitive processes and social relations.

The behavior of a close adult, namely his immediate reaction to the stressor and the quality of further interaction, plays a major role in the formation of a stress disorder in a small child and can both reduce the psycho-traumatic effect of circumstances and intensify it. If a stress disorder is detected in a mother, both members of the mother-child dyad should be involved in the treatment process, otherwise treatment for a child in the first years of life may be ineffective. Therapeutic interventions on the dyad may include medication and psychotherapy. For an adult, methods of systematic desensitization and other techniques of behavioral therapy, various methods of responding to painful experiences are usually used (Nikolskaya, 2013), as well as training in recognizing trigger (triggering) stimuli in a child and methods of extinguishing his pathological reactions (Early diagnosis and correction , 2007). For young children with PTSD, special methods of play and art therapy have shown their effectiveness (Dobryakov, Nikolskaya, 2013), as well as the Floortime method, developed in recent years specifically for infants and young children with mental health disorders (Greenspan, Wieder, 2013).