Dsm 5 new

Revisions to DSM 5 Coming in March 2022

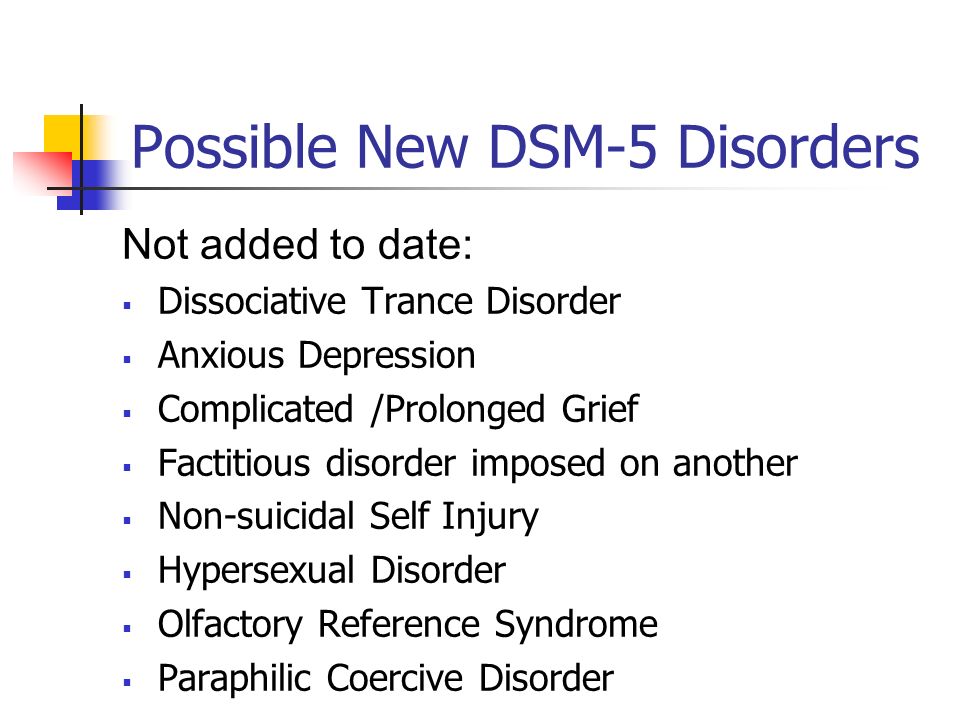

The American Psychiatric Association has announced revisions to the DSM 5 which will be released in March 2022. The revised manual, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, Text Revision (DSM-5-TR) is used by clinical social workers and other health care professionals in the United States as the authoritative guide to the diagnosis of mental disorders. Last updated in 2013, significant changes include the addition of prolonged grief disorder, the inclusion of symptom codes for suicidal behavior and non-suicidal self-injury, refinement of criteria, updates to diagnostic criteria, and specifier definitions. A brief overview of the changes is provided below.

Clinical social workers may purchase a copy of the DSM-5-TR from Amazon, any large bookstore, or the American Psychiatric Association at www.psychiatry.org

Prolonged Grief Disorder

- It occurs in individuals, who have experienced a death of a person close to them over a 12-month period for adults and 6 months for children and adolescents.

- The grief response persists following the death and is characterized by intense yearning/longing for the deceased or preoccupation with thoughts of the deceased.

- Children and adolescents, however, may be preoccupied by the circumstances surrounding death.

- Severity and duration of the grief response exceeds cultural, social, and religious norms.

- Presentation of symptoms are not attributed to another mental disorder and result in significant distress or impairment in daily functioning.

- It must also exhibit three or more of the following symptoms that are clinically significant most days. Symptoms must be present almost every day for at least 30 days:

- Intense emotional pain related to the death.

- Avoidance of reminders that the person is dead (in children and adolescents, may be characterized by efforts to avoid reminders).

- Marked sense of disbelief about the death.

- Difficulty reintegrating into one’s relationships and activities after the death.

- Identity disruption since the death.

- Intense loneliness as a result of the death.

- Emotional numbness (absence or marked reduction of emotional experience) as a result of the death.

- Feeling that life is meaningless as a result of the death.

Symptomatic Codes for Suicidal and Non-Suicidal Self-Injurious Behavior

New symptomatic codes identify the presence or history of suicidal and non-suicidal self-injurious behaviors. Researchers will now have a systematic way to track prevalence of these behaviors and other correlating factors that need ongoing attention.

Diagnostic Criteria

The new manual provides updates and modifications to the set of criteria for over 70 disorders with revised descriptive text for a number of disorders. It also contains an analysis of the effects racism and discrimination on the manifestation and diagnosis of mental disorders.

Diagnostic criteria for several disorders were clarified, to include the following diagnoses:

- Major depressive disorder

- Cyclothymic disorder

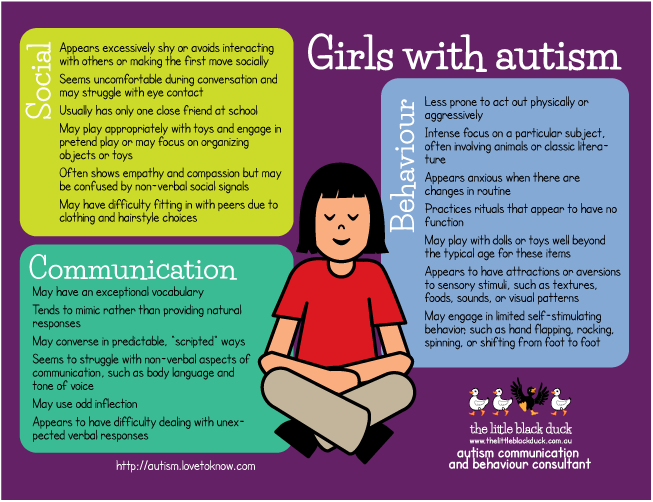

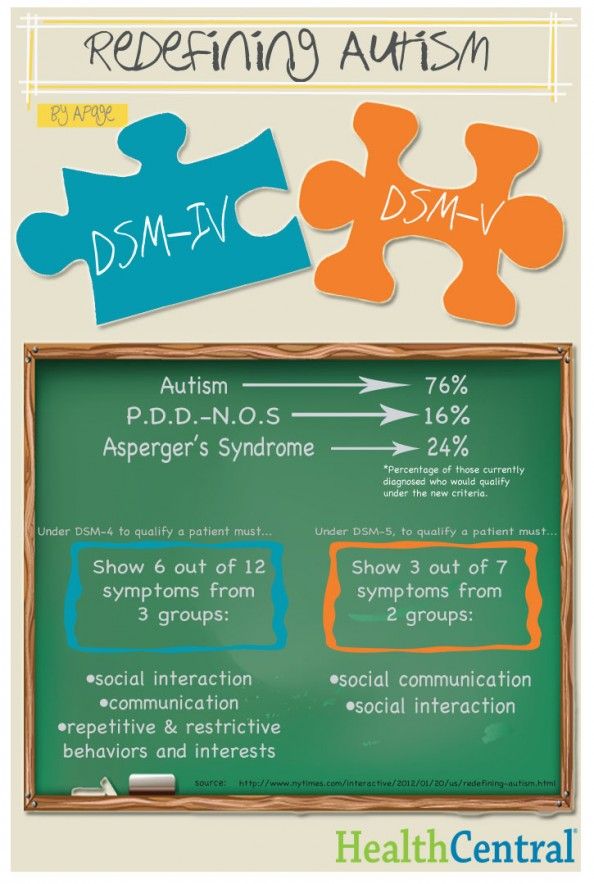

- Autism spectrum disorder

- Avoidant-restrictive food intake disorder

- Bipolar I and bipolar II disorder

- Manic episode

- Persistent depressive disorder

- Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in children

- Attenuated psychosis syndrome (in the chapter “Conditions for Further Study”)

- Substance/medication-induced mental disorders

- Delirium

Additionally, changes to criteria were amended to include:

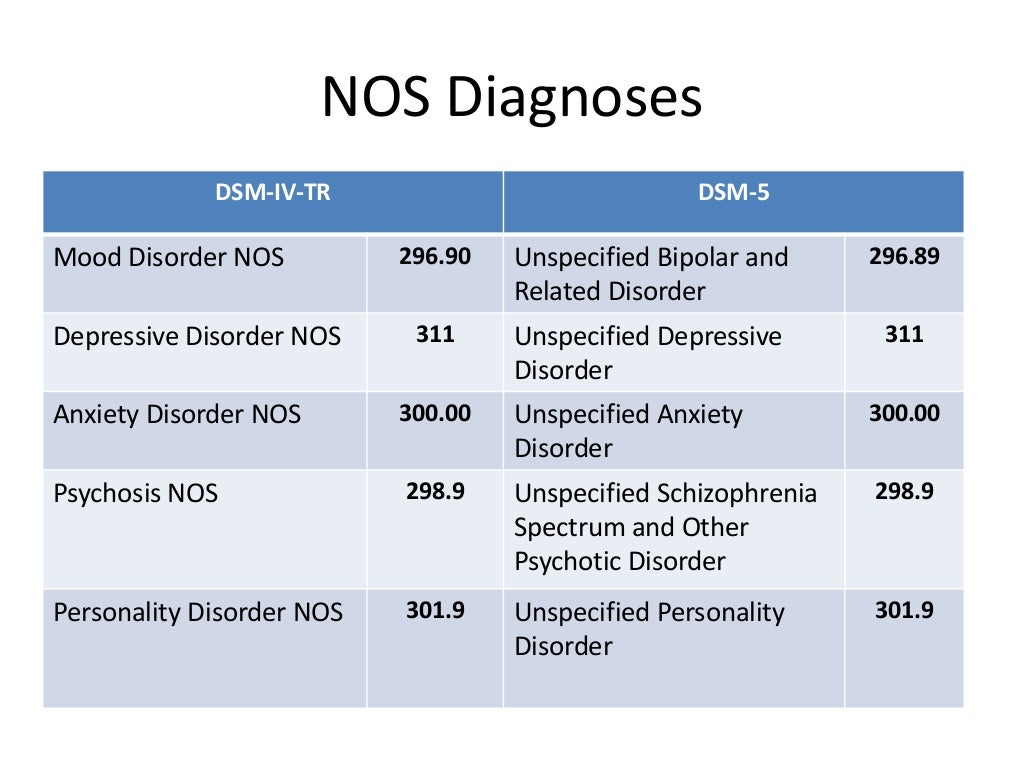

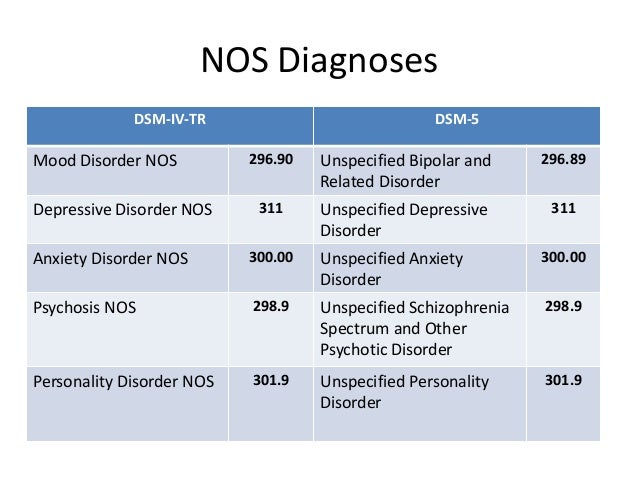

- The return of “Unspecified Mood Disorder” for mixed-mood presentations that do not fit the criteria for bipolar or depressive disorders

- Coding updates for substance use and neurocognitive disorders

- The inclusion of symptom codes that specify the presence or history of non-suicidal self-injury and suicidal behavior

Specifier Definitions

Changes to specifier definitions were also identified and are as follows:

- the post-transition specifier for gender dysphoria

- the acute/persistent specifier for adjustment disorder

- Narcolepsy specifiers

- the mood congruent/mood incongruent specifier for bipolar disorder

- the mixed features specifier for major depressive disorder and

- Manic Episode

Other Changes

- The term “neuroleptic,” which refers to a class of medication, will only be used when referring to “neuroleptic malignant syndrome” and will now be replaced with “antipsychotic medication” or other terms depending on the context.

- “Desired gender” will be referred to as “experienced gender.”

- “Cross-sex medical procedure” will now be regarded as “gender-affirming medical procedure,”

- “natal male”/“natal female” will be called “individual assigned male/female at birth.”

- Conversion disorder is now functional neurological symptom disorder

- intellectual disability is now intellectual developmental disorder.

Reference

Moran M. Updated DSM-5 text revisions to be released in March. Psychiatric News. Accessed February 09, 2022.

Prepared by

Denise Johnson, LCSW-C

Senior Practice Associate, Clinical Social Work

DSM5mental health 2022-03-03

Diagnostic Criteria, Inclusivity, and Racial Equity

- The DSM-5 released updates to its diagnostic and taxonomic criteria in March 2022 as the DSM-5-TR, including the addition of prolonged grief disorder.

- Codes for clinicians have been altered, which may improve the insurance claims process for certain mental health conditions.

- Cultural, racial, and ethnic factors, as well as gender inclusivity, have been intentionally reviewed and updated in the new DSM-5-TR.

As the stigma around mental health continues to fade, the field itself is changing — some might say for the better.

In March 2022, American Psychiatric Association (APA) Publishing released a Text Revision (TR) to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition (DSM-5) to add clarity around certain mental health conditions and diagnostic criteria and codes.

Highlights in the newly updated DSM-5-TR include the addition of prolonged grief disorder as a condition, as well as symptom codes for suicidal behavior and nonsuicidal self-injury.

The APA also consulted culture and equity professionals to acknowledge the historical role of racial discrimination in clinical diagnoses. Language throughout the DSM-5-TR was updated to promote inclusivity for People of Color and marginalized groups.

Language throughout the DSM-5-TR was updated to promote inclusivity for People of Color and marginalized groups.

The DSM-5-TR has refined some of its diagnostic criteria and codes, which may better inform how mental health professionals work with their clients and how they file claims with insurance companies.

Although the DSM-5-TR cannot fully address the unique experiences and situations of every individual, improved diagnostic criteria may help clinicians identify their clients’ disorders or conditions with more accuracy.

“For the [clients] whose symptoms are not fully represented in the present DSM-5, this is a start to treatment planning and more thoughtfully diagnosing,” said Kendra Kubala, PsyD, a trauma psychologist in Pennsylvania and New York and Psych Central Advisory Board member, in an email.

Prolonged grief disorder

The DSM-5-TR added symptoms associated with prolonged grief disorder to its list of diagnostic criteria. Now, clinicians can make a formal diagnosis for those who have faced difficulty coping with loss for an extended period of time.

Still, everyone’s grieving process is different, and there’s some controversy among clinicians when it comes to linking a person’s experiences of loss to a mental health disorder.

“I think these [clients] would generally get lumped into adjustment disorders or depression diagnoses,” said Karin Gepp, PsyD, a clinical psychologist in New York and Psych Central Advisory Board member, said in an email.

“But studies have shown that 1 in 10 adults may experience prolonged grief — especially now, with this pandemic having killed so many people suddenly, this is a really important addition,” she said.

Diagnostic criteria

According to the DSM-5-TR, the diagnostic criteria for prolonged grief includes:

- a persistent grief response for a duration of longer than 12 months (6 months for a child)

- symptoms that significantly interrupt a person’s day-to-day functioning

- experiences that can’t be attributed to another condition, such as major depressive disorder (MDD) or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

Unspecified mood disorder

The DSM-5 removed “unspecified mood disorder” as a diagnosis in its 2013 update, which meant that clinicians had to diagnose their clients with a specific mood disorder instead.

The DSM-5-TR has reverted to the “unspecified” diagnosis to include a range of possible mood disorders, which may help clinicians avoid potential misdiagnoses.

“Unspecified mood disorder has been reinstated to provide diagnosis to someone whose presenting symptoms do not fit neatly under bipolar or depressive disorders,” Kubala said.

According to Gepp, distinguishing between bipolar disorder and depressive disorders takes time. Often, symptoms concurrent with bipolar disorder are not always noticeable at the onset.

“When a patient is misdiagnosed with depression and prescribed an SSRI, this could push that person into a manic episode,” Gepp explained.

According to Gepp, the DSM-5-TR reinstating unspecified mood disorder allows practitioners more time to observe a client’s symptoms to provide a more accurate diagnosis and subsequent prescription.

Nonsuicidal self-harm

The DSM-5-TR has added self-harm without the presence of suicidality to its list of diagnoses.

Because not everyone who has engaged in self-harm may do so with the intent of ending their life, lumping it into suicidality could blur assessments made by clinicians.

“It’s good to differentiate those, as there [are] many people who self-harm without an intention of suicide,” Gepp said. “The intent of the injury is the focus, which makes it easier to track the behaviors for us and assess risk.”

In addition, diagnostic codes for suicidal behavior without the presence of other mental health disorders have been included in the new updates.

The DSM-5-TR includes changes to its language around gender and gender identity to help reduce stigma by clarifying that these aspects of a person are not selected by choice.

This includes the more accurate and inclusive changes of:

- “desired gender” to “experienced gender”

- “cross-sex medical procedure” to “gender-affirming medical procedure”

- “natal male/native female” to “individual assigned male/female at birth”

Roberto Lewis-Fernandez, MD, a professor of clinical psychiatry at Columbia University and chair of the DSM-5-TR Cross-Cutting Culture Review Group, told Psych Central that reviewing the DSM through a lens of equity and inclusion and making appropriate changes were high on the committees’ priority list.

Debra Rose Wilson, PhD, MSN, RN, a professor, holistic healthcare practitioner, and Psych Central Advisory Board member, said the addition of racial and cultural perspectives in the DSM-5-TR is beneficial.

“If we’re going to be talking about this, then we should talk about social norms and cultural norms and how they’re going to be different depending on race and where you live, and I think that’s worth identifying,” Wilson said by phone.

According to Lewis-Fernandez, future iterations of the DSM-5 will likely incorporate further changes, specifically around how social, sociocultural, and genetic disorder causations intersect, all with the goal of enabling clients to be seen within a more holistic framing.

“The role of social determinants of mental health has been increasingly recognized in recent years,” he said. “DSM-5-TR started to incorporate this information but there is still more that needs to be done in this area.”

The DSM-5-TR’s acknowledgment of how race and discrimination have historically impacted mental health care is a step forward in creating more safe and inclusive environments for People of Color and marginalized groups.

But barriers to quality mental health care still exist, such as cost factors, health insurance, and enough access to culturally competent counselors and therapists.

According to Kubala, the varied opinions and shifting cultural dynamics within the mental health field speak to the necessity of ongoing updates to the DSM. As research in the field continues to evolve, so will the manual.

“It’s always beneficial to have an open dialogue between [clients], providers, and the public regarding mental illness, and ways in which the field is continually evolving in an effort to provide the most comprehensive, sensitive, research-based, compassionate, appropriate treatment,” Kubala said.

New American classification of mental disorders DSM-5 released to the world

Home > News > The new American classification of mental disorders DSM-5 is released to the world

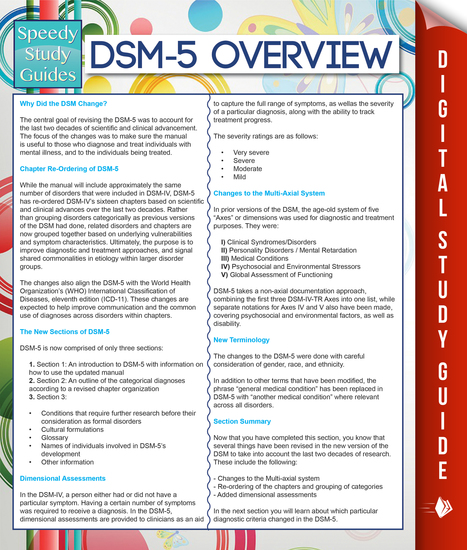

| DSM-5 consists of three sections: it is (1) an introductory part with instructions for use and a warning about the forensic psychiatric use of the DSM-5; (2) diagnostic criteria and codes for routine clinical use; and (3) tools and techniques to inform clinical decision making. Major changes:

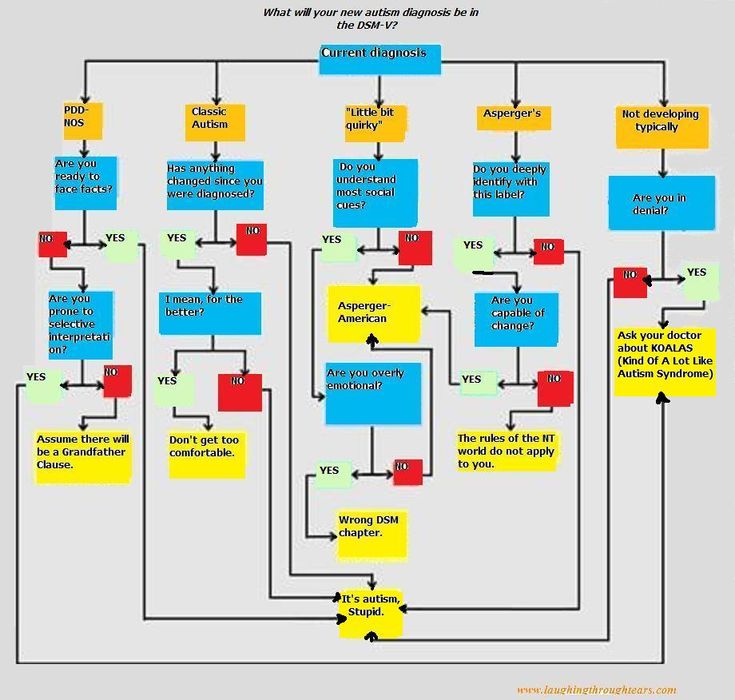

The severity of the disorder is not determined by IQ, but by the level of adaptive functioning. Speech disorders have entered the new category "social communication disorder", in which some of the syndromes coincide with "autism spectrum disorder". The category "Autism Spectrum Disorders" replaces the DSM-4 diagnoses of autism, Asperger's syndrome, childhood disintegrative disorder, and an unspecified general developmental disorder, all of which cease to exist as separate diagnoses. ADHD can start later (before 12) and is treated differently in different areas. Learning disorders and movement disorders are organized differently in this chapter and somewhat combined.

For the diagnosis of schizophrenia, symptoms of the first Schneider rank lose their special weight. One positive symptom is required for a diagnosis to be made.

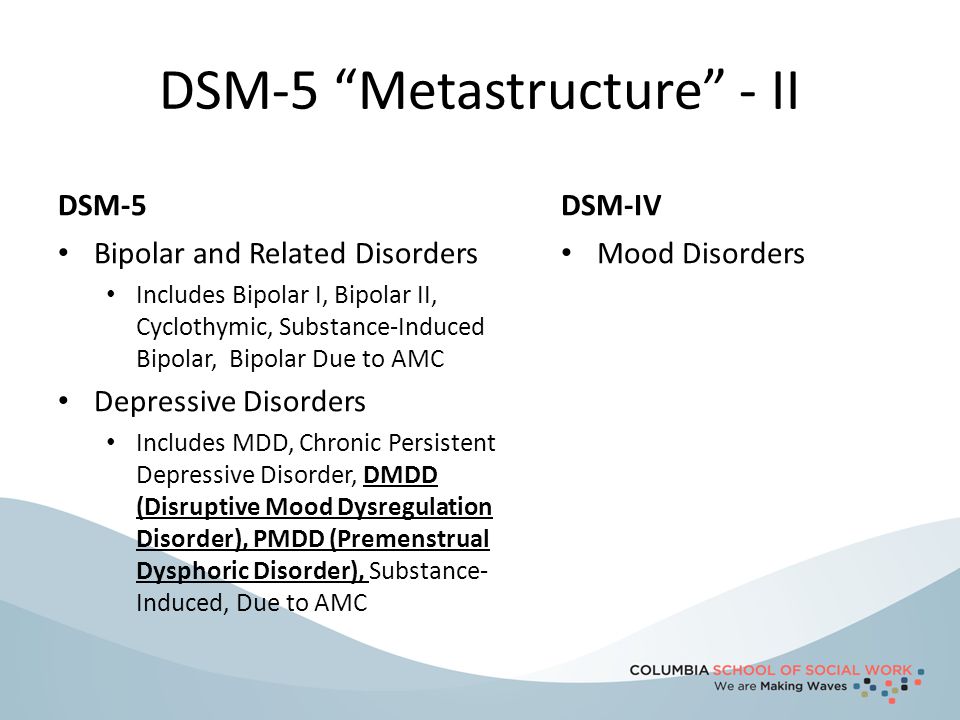

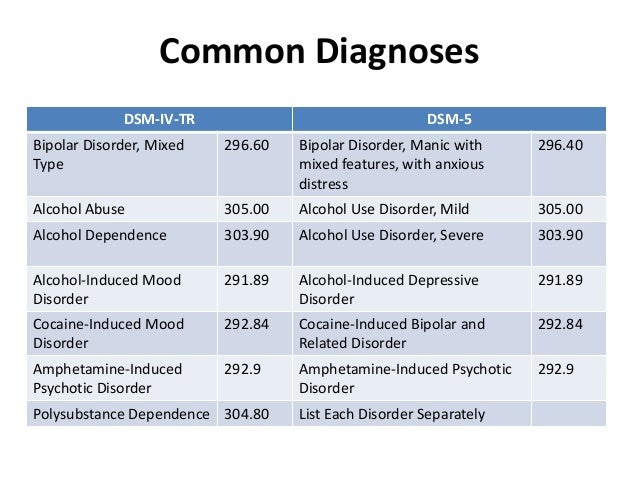

Bipolar and related disorders are now separated from depressive disorders and placed in a separate category. A clearer definition of mania is given and refinements for mixed episodes are introduced, which lowers the threshold for disorder. Added a residual subcategory ""other"" and a qualifying score for anxiety symptoms.

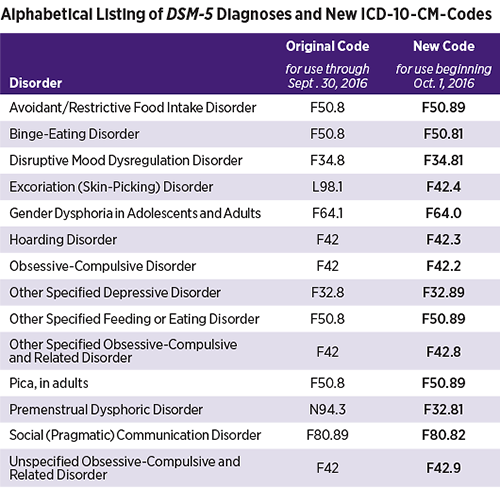

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder and premenstrual dysphoric disorder added. Chronic depression and dysthymia are combined into one diagnosis, now it is ""persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia)"" with a number of clarifying indicators.

|

ISSN 2588-0519 (Print)

ISSN 2618-8473 (Online)

DSM-5 - frwiki.wiki version

DSM-5 located at Latest and fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders ).

Published in the USA on , it replaces the previous edition dated 2000 after consultation, editing and preparation.

The French version was released by .

This new version of the manual has been criticized for its scientific nature and related pharmaceutical interests.

Summary

- 1 Development

- 2 Major changes

- 2.1 Addictology

- 2.2 Schizophrenia

- 2.3 Autism Spectrum Disorders

- 2.4 Bipolar disorder

- 2.5 Personality disorders

- 2.6 Attention deficit disorder

- 2.7 Hypersexual disorder

- 3 reviews

- 4 Bibliography

- 5 Notes and references

- 6 See also

- 6.1 Related articles

- 6.2 External links

Development

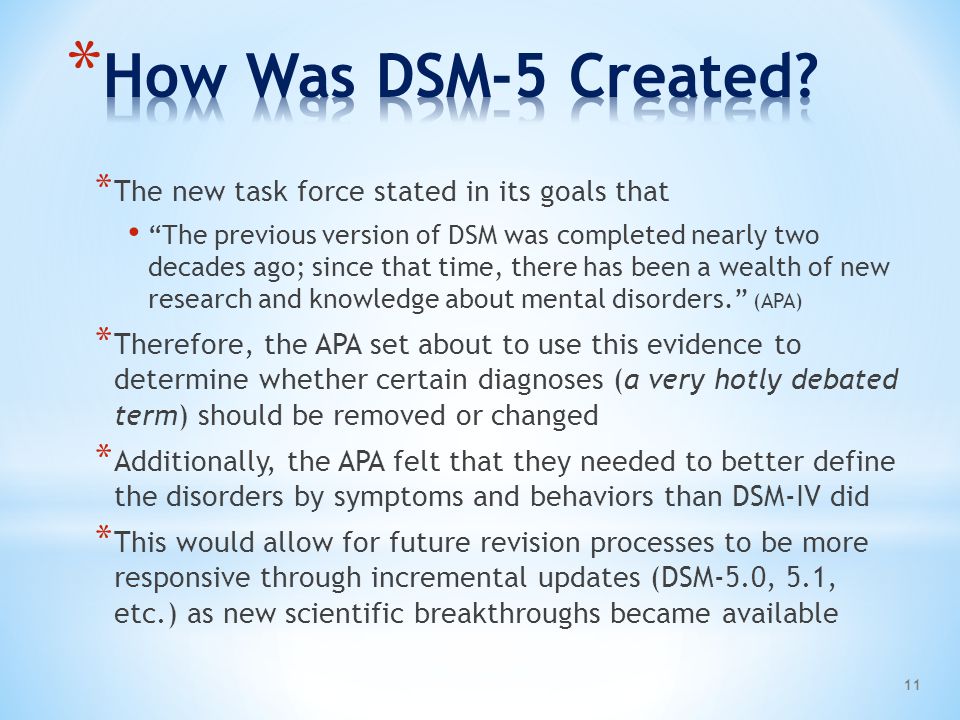

In 1999 a research conference on DSM-5 sponsored by the APA and National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) was held to determine priorities. Six different groups of researchers focus on each topic: nomenclature, neuroscience and genetic diagnoses and developmental issues, relationships and personality, disability and mental disorders, and intercultural issues. For the first time in the history of this revision, the APA requires psychiatrists working on the revision to sign a strict confidentiality agreement. In an open letter, Robert Spitzer, editor of DSM- III , calls for the removal of the secrecy requirement so that outsiders can analyze the scientific debate behind new and revised diagnoses. Darrell Regier, co-editor of the new version, argues that development should be kept confidential.

In an open letter, Robert Spitzer, editor of DSM- III , calls for the removal of the secrecy requirement so that outsiders can analyze the scientific debate behind new and revised diagnoses. Darrell Regier, co-editor of the new version, argues that development should be kept confidential.

At , the APA announced to its members that it would oversee the development of the DSM-5. The book was written by 32 participants and led by David Kupfer, professor of neuroscience at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. The scientists working on the drafting of the DSM text come from research, clinical care, biology, genetics, statistics, epidemiology, public health, and consumer advocacy backgrounds.

The new organization of the chapters also aims to bring out more areas of diagnosis that appear to be interrelated, exemplified by the creation of a distinct category for bipolar disorder and related disorders (previously classified as mood disorders with depression) which is placed immediately after spectrum of schizophrenia. disorders and other psychotic disorders.

disorders and other psychotic disorders.

In each diagnostic category, disorders commonly diagnosed in childhood are listed first.

Major changes

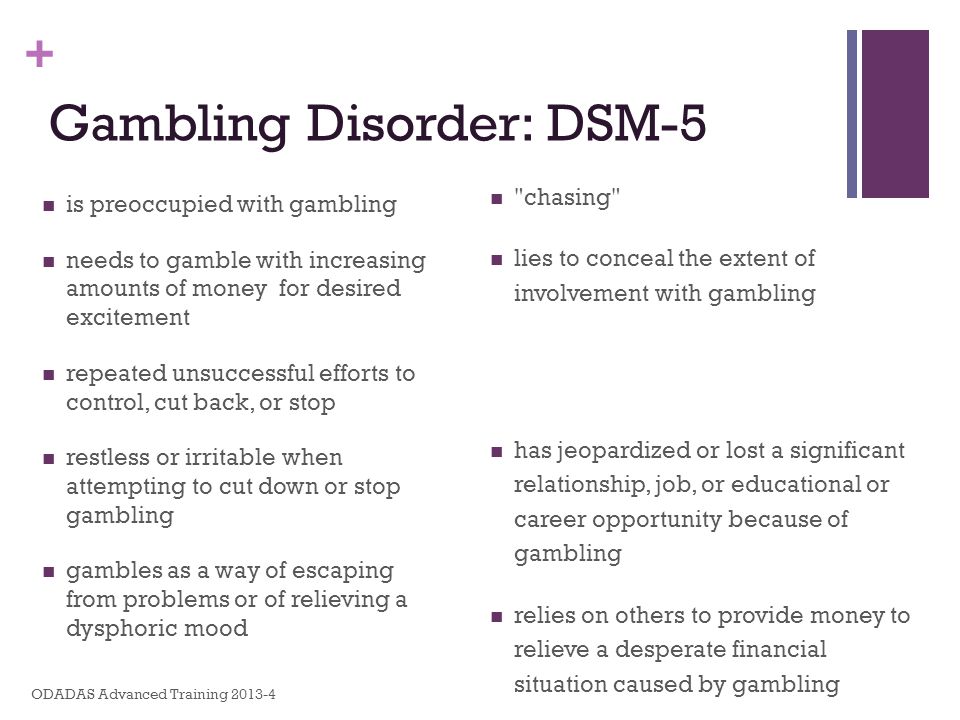

Addictology

In addictology, the concepts of abuse and dependence are outdated.

Substance use disorder is defined as having at least two of the following criteria within one year:

- high consumption or longer than expected;

- unsuccessful attempts to stop;

- painstaking;

- rod ;

- change of obligations;

- persistence of use despite the problems it causes;

- refusal from other activities;

- dangerous situations;

- tolerance;

- weaning.

Severity is rated by section:

- mild with 2-3 symptoms;

- moderate with 4-5 symptoms;

- harsh outside.

Schizophrenia

The following has been removed from 5- DSM Edition:

- 295.

30 Schizophrenia - paranoid type

30 Schizophrenia - paranoid type - 295.10 Schizophrenia - disorganized type

- 295.20 Schizophrenia - catatonic type

- 295.90 Schizophrenia - undifferentiated type

- 295.60 Schizophrenia - residual type

- 297.3 General psychotic disorder

Autism Spectrum Disorders

Asperger's Syndrome is more classified as a disorder in its own right, and instead is not included in the Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) section. Under this new classification proposal, clinicians rate the severity of clinical symptoms present in ASD (severe, moderate, or moderate). However, this proposal has been the subject of several criticisms from Asperger's specialists such as Tony Attwood and Simon Baron-Cohen.

Bipolar disorder

Proposals have been made for further research into bipolar disorder (Akiskal and Ghaemi, 2006) . These proposals include, in particular, more detailed criteria for diagnosing bipolar disorder in children.

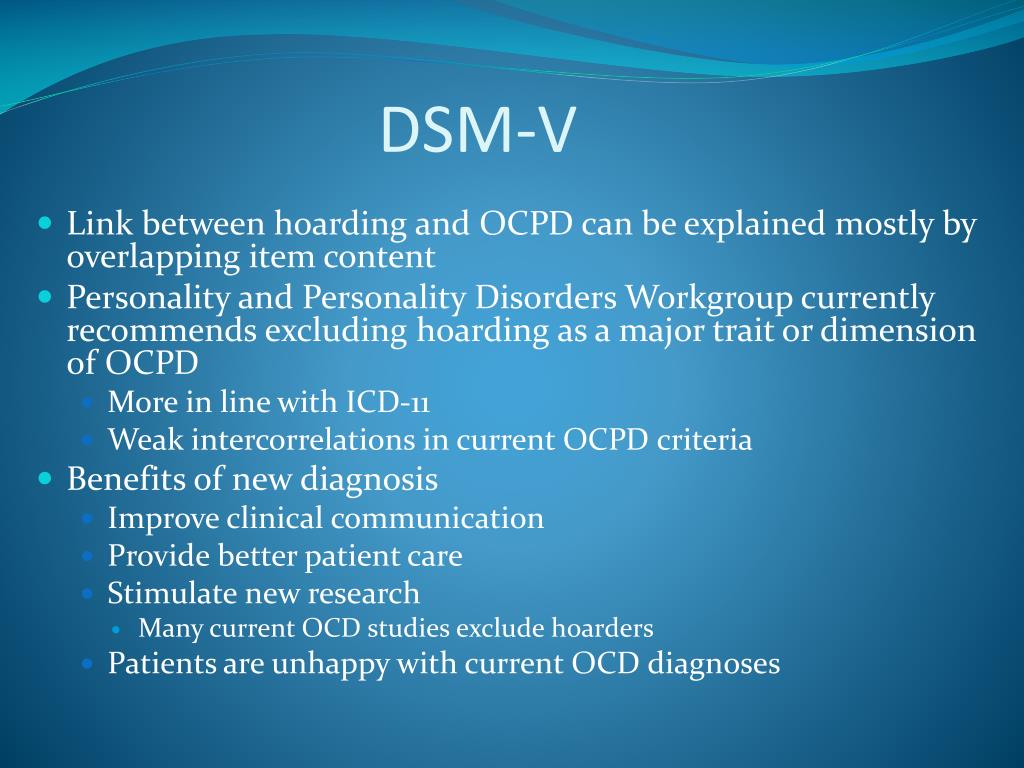

Personality disorders

A "major rethink" is proposed for personality disorders. APA Releases , on its website, draft criteria for various personality disorder diagnoses. They are based on a multidimensional approach rather than the traditional so-called "categorical" approach that has been in place since the introduction of personality disorders in the DSM-9.0196 III (1980). Although promising, the dimensional approach has been placed in section 3 of the DSM-5 as an alternative to the categorical approach, which has always been supported.

Dimensional categorization clearly differs from categorical: three clusters have disappeared, as well as four standard disorders, namely schizoid personality disorder, paranoid personality disorder, hysterical personality disorder and hysterical personality disorder. Dependent personality. Thus, the alternative categorization suggests six prototype diagnoses:

- Schizotypal personality disorder

- Borderline personality disorder (borderline)

- Antisocial personality disorder

- Narcissistic personality disorder

- Obsessive Compulsive Personality Disorder

- Other personality disorder - defined by traits

In contrast to categorical categorization, for which the clinician only has to postulate the presence or absence of traits for each personality disorder under investigation, dimensional categorization is divided into three parts. The first part consists of assessing the patient's achievement of personal and interpersonal functioning using a continuum. The second part is aimed at identifying his pathological personality traits, as well as the degree of their severity. There are five such traits: negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychotism, each of which consists of three to nine personality facets. This part uses different approaches to classification: categorical and dimensional. First, we seek to determine if the patient has pathological features (categorical approach), then secondly, we attempt to assess their severity by assigning them scores ranging from low to low. Very heavy (dimensional approach). Finally, the third part consists of creating a general portrait of the patient's personality based on the data collected in the first two parts, and then comparing it with prototype portraits of various disorders in order to assess their fit. This comparison allows one to assess the degree of similarity (spatial approach) between the patient's personality and one or another of the prototypical portraits of various personality disorders.

The first part consists of assessing the patient's achievement of personal and interpersonal functioning using a continuum. The second part is aimed at identifying his pathological personality traits, as well as the degree of their severity. There are five such traits: negative affectivity, detachment, antagonism, disinhibition, and psychotism, each of which consists of three to nine personality facets. This part uses different approaches to classification: categorical and dimensional. First, we seek to determine if the patient has pathological features (categorical approach), then secondly, we attempt to assess their severity by assigning them scores ranging from low to low. Very heavy (dimensional approach). Finally, the third part consists of creating a general portrait of the patient's personality based on the data collected in the first two parts, and then comparing it with prototype portraits of various disorders in order to assess their fit. This comparison allows one to assess the degree of similarity (spatial approach) between the patient's personality and one or another of the prototypical portraits of various personality disorders.

attention deficit disorder

Some suggestions have been made to improve diagnostic criteria related to age of symptom onset. This proposal aims to change the diagnostic criteria for symptoms present before the age of seven to symptoms present before the age of twelve.

A minimum of four symptoms are expected to be identified for concentration problems and hyperactivity/impulsivity in individuals 17 years of age and older. Existing DSM Criteria - IV TR to highlight six symptoms will be applied to adolescents aged 16 or less.

Hypersexuality disorder

Hypersexuality disorder is proposed as a new category. The diagnosis will apply to people who experience these symptoms (most of the time used for sexual achievement, using sex to compensate for depression or stress, repeated but unsuccessful attempts to control or greatly reduce these fantasies, and t . D. ). In addition, it will only apply if the problem persists for six months or more, when the person is under personal stress or embarrassed by these symptoms, and when the problem is not caused directly by the drug or other criteria. This sentence is an official diagnosis, which will also be refined to refer to problem behavior(s) associated with the following: masturbation, pornography, cybersex, and etc. .

D. ). In addition, it will only apply if the problem persists for six months or more, when the person is under personal stress or embarrassed by these symptoms, and when the problem is not caused directly by the drug or other criteria. This sentence is an official diagnosis, which will also be refined to refer to problem behavior(s) associated with the following: masturbation, pornography, cybersex, and etc. .

The term "hypersexual disorder" was chosen because it does not refer to any (known) cause of hypersexuality. A proposal to add sex addiction to the DSM classification was rejected by the APA.

In DSM - IV TR shows "unspecified sexual disorder" applies, among other conditions, "Disorder resulting from a repetitive fashion of sexual relations associated with a succession of sexual partners that the individual perceives as objects that we use. "

"

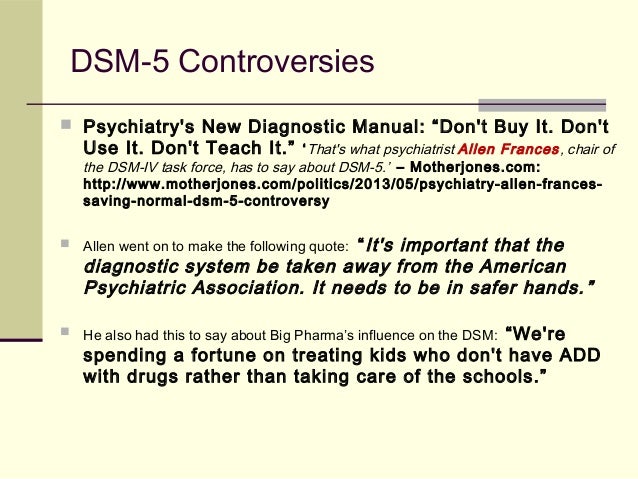

Reviews

The DSM-5 was criticized before its publication and was the subject of controversy and controversy: petitions, calls for a boycott, books condemning dangerous work that causes mental illness and has no scientific basis, which serves the pharmaceutical industry with the risk of overdiagnosis and hence over-medicalization.

In the US, former editor of DSM- IV -TR Allen Francis and the National Institute of Mental Health, particularly through its director Thomas R. Insel, have voiced strong criticism in this regard.

Bibliography

- (en) American Psychiatric Association, DSM-5, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders , 5- e Edition, Washington, DC, American Psychiatric Association, 2013 ( ISBN 0 525084)

- Steves Demaze: What is DSM? Genesis and Transformations of the American Psychiatric Bible , Sat: Philosophy, Anthropology, Psychology, 2013 (ISBN 978-2-916120-36-2)

- Patrick Sandman, Allen Francis, Tristes business.

DSM-5 scandal, 2014

DSM-5 scandal, 2014 - Jean-Claude Aguerre, Guy Dana, Mariel David et al., "Communique of the Collective of Initiatives for the STOP DSM Subject Clinic", Clinical Psychology , 2015/2 (No. 40), pp. 259-259, [read online] .

Notes and links

- ↑ (in) " DSM-5, publication rescheduled for May 2013. " (as of March 23, 2011)

- ↑ a and b " DSM-5: The book that drives crazy", on Le Monde (blog), (accessed October 16, 2011)

- ↑ (ru) DSM-5 official development site

- ↑ Sandrine Kabut, " Mental illness: DSM-5 classification in VF ", on Le Monde.

fr (consultation 28 September 2015)

fr (consultation 28 September 2015) - ↑ " DSM-5: French translation of available" on Psychomedia (accessed September 28, 2015)

- ↑ a and b Hestion, " Revision of DSM- V (Bible of Psychiatric Diagnosis): Transparency Required", at Psychomedia.qc.ca, (accessed October 20, 2011 .)

- ↑ a and b Management, " DSM-5: Proposed new organization of diagnoses ", on Psychomedia.qc.ca, (accessed October 20, 2011)

- ↑ (c) " Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders " on the American Psychiatric Association (accessed May 5, 2010)

- ↑ (in) « Away with Asperger's: what is it? ", On Psychology Today (accessed 16 October 2011).

- ↑ (in) " Powerful Personality, Disappearing Diagnosis ", in New York Times (accessed October 16, 2011)

- ↑ (in) " Proposed Revision - APA DSM-5 - Asperger's Disorder " on the American Psychiatric Association, .

- ↑ (in) Benedict Carey, " Revision of the book on mental disorders ", in The New York Times,

- ↑ (in) " Proposed Revision - APA DSM-5 - Temperamental Regulation Disorder with Dysphoria " on the American Psychiatric Association,

- ↑ (in) Benedict Carey, " Revision of the Mental Disorders Book", in The New York Times, (accessed 1 - and May 20103)90

- ↑ a and b " DSM- V : Proposed new definition of personality disorders ", (accessed October 20, 2011)

- ↑ (c) " Personality and Personality Disorders " by American Psychiatric Association

- ↑ (ru) Skodol et al.

, " Rationale for Proposed Reclassification of Personality Disorders in DSM-5 9Louis Tivierge. Paradigm shift and personality disorder terminology . Graduate work. Laval University. 2013, pp. 65-68 (pending).

, " Rationale for Proposed Reclassification of Personality Disorders in DSM-5 9Louis Tivierge. Paradigm shift and personality disorder terminology . Graduate work. Laval University. 2013, pp. 65-68 (pending). - ↑ a and b (en) " Proposed Revision - APA DSM-5 - 314.0x Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder ", on the American Psychiatric Association,

- ↑ a b c and d Manual: " What is hypersexuality (new diagnosis proposed for DSM-5)?" ", Available at Psychomedia.qc.ca, (accessed 20 October 2011)

- ↑ a and b (in) " American Psychiatric Association DSM-5 Development Page for Hypersexual Disorder " on American Psychiatric Association (accessed October 20, 2011)

- ↑ (ru) Kafka MP.

(2010) "Hypersexual Disorder: A Proposed Diagnosis for DSM- V » Archives of Sexual Behavior , 39, 377–400.

(2010) "Hypersexual Disorder: A Proposed Diagnosis for DSM- V » Archives of Sexual Behavior , 39, 377–400. - ↑ (in) Rita Rubin, " The Psychiatry Bible: Autism, Overeating" Proposed for "DSM" "on www.usatoday.com,

- ↑ (in) " Sex Addiction, Obesity, and Internet Addiction Not Included in Proposed Exchange with APA Diagnostic Manual " on nydailynews.com, New York

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM- IV -TR) , Washington, DC.

- ↑ Sandrine Kabut, " Psychiatry: DSM-5, a manual that drives you crazy ", Le Monde.fr , (ISSN 1950-6244, read online)

- ↑ (in) Francis Allen: Keeping normal: an insider's rebellion against the out-of-control DSM-5 psychiatric diagnosis, Big Pharma, and the medicalization of everyday life. William Morrow. section 336 . (ISBN 978-0062229250)

- ↑ (ru) NIPZ position

- ↑ (in) David Kupfer, MD, responds to NIMH Director's criticism of DSM-5

- ↑ Geyer, M.

Subtypes are removed - in favor of the dimensional indicator of severity. For schizoaffective disorder, the mood aspect is emphasized, and for delusional disorder, frivolous content is no longer excluded – although it is evaluated separately. The "catatonia" section has been expanded: this code can now be entered as an adjacent diagnosis (specifying indicator) for depressive, bipolar and psychotic disorders.

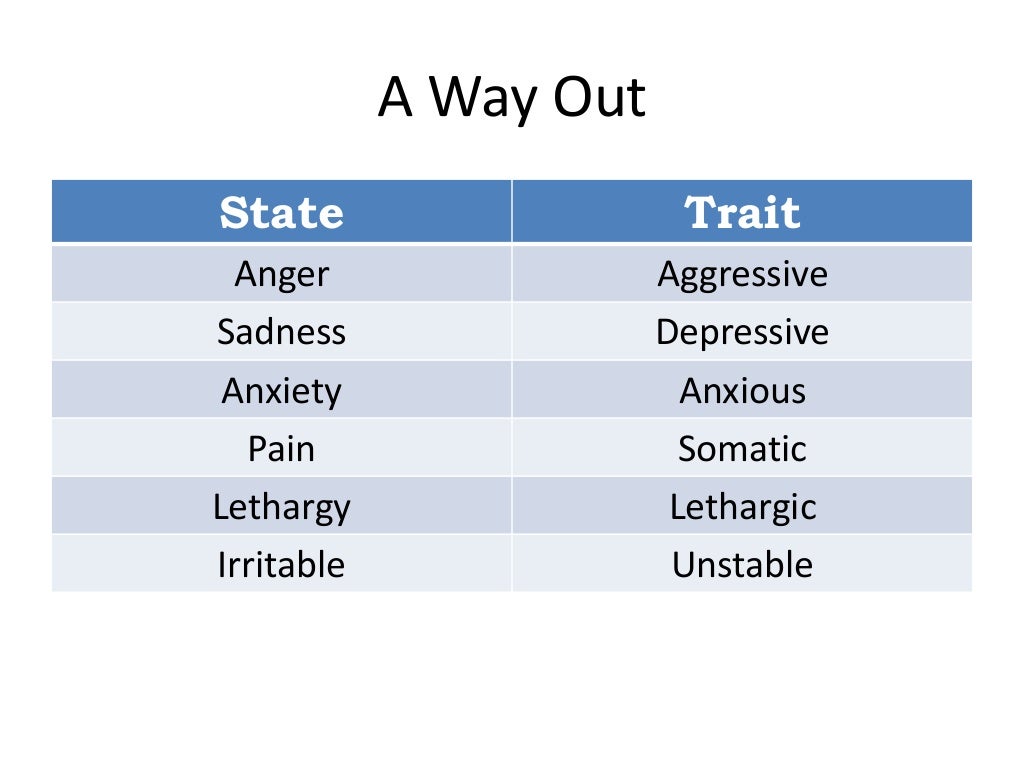

Subtypes are removed - in favor of the dimensional indicator of severity. For schizoaffective disorder, the mood aspect is emphasized, and for delusional disorder, frivolous content is no longer excluded – although it is evaluated separately. The "catatonia" section has been expanded: this code can now be entered as an adjacent diagnosis (specifying indicator) for depressive, bipolar and psychotic disorders.  Major depressive disorder remained virtually unchanged, however, for "subthreshold" symptoms, a clarifying indicator ""mixed manifestations"" was introduced. A clarifying indicator for anxious distress has also been introduced. Removed grounds for exclusion for grief. 9(see below) Various phobia criteria are slightly adapted, and agoraphobia and panic are decoupled. Panic attacks can act as a clarifying indicator for other diagnoses. The diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism are no longer specific "childhood" diagnoses.

Major depressive disorder remained virtually unchanged, however, for "subthreshold" symptoms, a clarifying indicator ""mixed manifestations"" was introduced. A clarifying indicator for anxious distress has also been introduced. Removed grounds for exclusion for grief. 9(see below) Various phobia criteria are slightly adapted, and agoraphobia and panic are decoupled. Panic attacks can act as a clarifying indicator for other diagnoses. The diagnoses of separation anxiety disorder and selective mutism are no longer specific "childhood" diagnoses.  Also ruled out is the requirement to directly experience fear, horror, or feelings of helplessness. Avoidance and emotional flattening are separated, and at the same time, emotional flattening is added, incl. persistent depressed mood. Recklessness, (auto) destructive behavior, irritability and aggression are added to the already known symptoms of arousal. For children and adolescents in puberty, lower diagnostic thresholds are used. The adjustment disorder remained unchanged. Reactive attachment disorder has been moved to this chapter.

Also ruled out is the requirement to directly experience fear, horror, or feelings of helplessness. Avoidance and emotional flattening are separated, and at the same time, emotional flattening is added, incl. persistent depressed mood. Recklessness, (auto) destructive behavior, irritability and aggression are added to the already known symptoms of arousal. For children and adolescents in puberty, lower diagnostic thresholds are used. The adjustment disorder remained unchanged. Reactive attachment disorder has been moved to this chapter.  Removed somatization disorder, hypochondriasis, pain disorder, and unspecified somatoform disorder from DSM. A diagnosis of a "disorder with somatic symptoms" can be made on par with a diagnosis from another medical specialty only if the somatic symptoms are associated with abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Unexplained medical symptoms play a decisive role only in false pregnancy and conversion (i.e. functional disorder with neurological symptoms). In other cases, positive symptoms should be sought in this group.

Removed somatization disorder, hypochondriasis, pain disorder, and unspecified somatoform disorder from DSM. A diagnosis of a "disorder with somatic symptoms" can be made on par with a diagnosis from another medical specialty only if the somatic symptoms are associated with abnormal thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Unexplained medical symptoms play a decisive role only in false pregnancy and conversion (i.e. functional disorder with neurological symptoms). In other cases, positive symptoms should be sought in this group.  The chapter presents a large number of sleep disorders described in terms of physical characteristics in relation to circadian rhythms and respiratory disorders. This group includes Restless legs syndrome and REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. A large diagnostic choice predisposes to move away from the use of "unspecified" diagnoses.

The chapter presents a large number of sleep disorders described in terms of physical characteristics in relation to circadian rhythms and respiratory disorders. This group includes Restless legs syndrome and REM Sleep Behavior Disorder. A large diagnostic choice predisposes to move away from the use of "unspecified" diagnoses.  In addition to a variety of impulse control disorders, antisocial personality disorder, dubbed from the chapter on personality disorders, also got here. The criteria for oppositional defiant disorder have been revised and weighted. In conduct disorder (Conduct Disorder), the grounds for excluding the diagnosis have been removed, but the clarifying indicator “callous-unemotional” has been added. Intermittent Explosive Disorder can now be verbal, and the rest of the criteria for this disorder are much more refined.

In addition to a variety of impulse control disorders, antisocial personality disorder, dubbed from the chapter on personality disorders, also got here. The criteria for oppositional defiant disorder have been revised and weighted. In conduct disorder (Conduct Disorder), the grounds for excluding the diagnosis have been removed, but the clarifying indicator “callous-unemotional” has been added. Intermittent Explosive Disorder can now be verbal, and the rest of the criteria for this disorder are much more refined.