Does low blood sugar cause depression

Is Your Mood Disorder a Symptom of Unstable Blood Sugar?

October 21, 2019

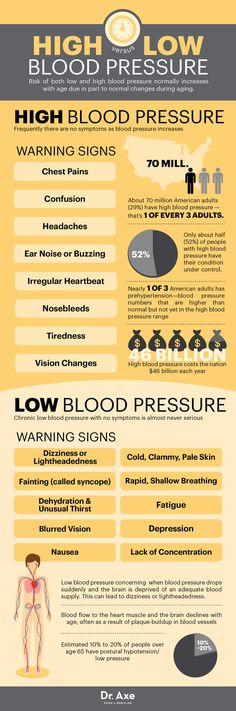

Many people may be suffering from symptoms of common mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety, without realizing that variable blood sugar could be the culprit.

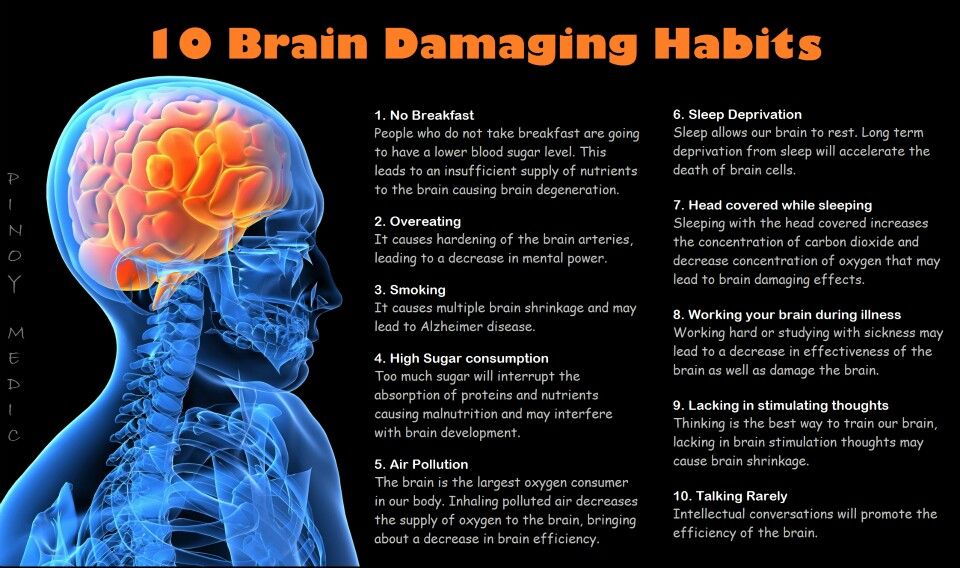

A growing body of evidence suggests a relationship between mood and blood-sugar, or glycemic, highs and lows. Symptoms of poor glycemic regulation have been shown to closely mirror mental health symptoms, such as irritability, anxiety, and worry. This should come as no surprise, as the brain runs primarily on glucose.

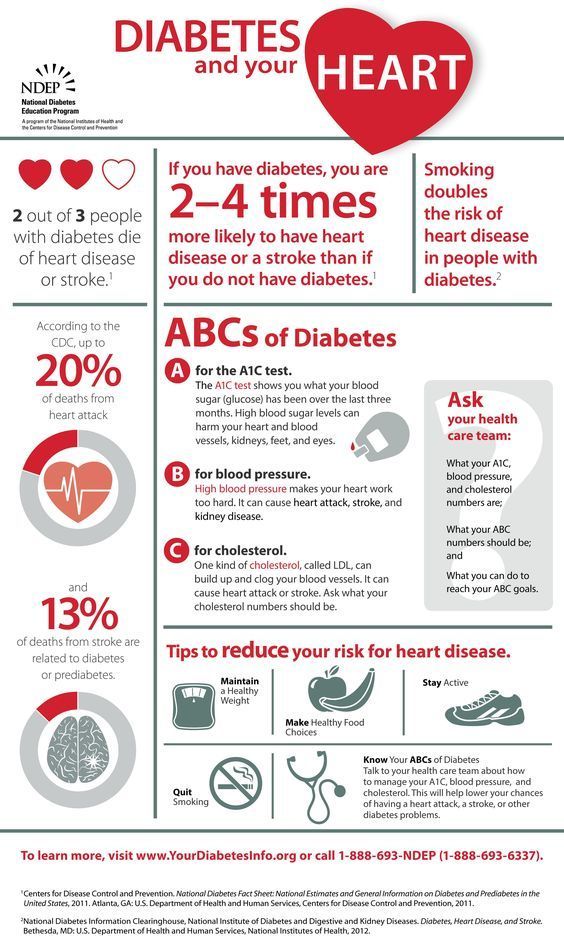

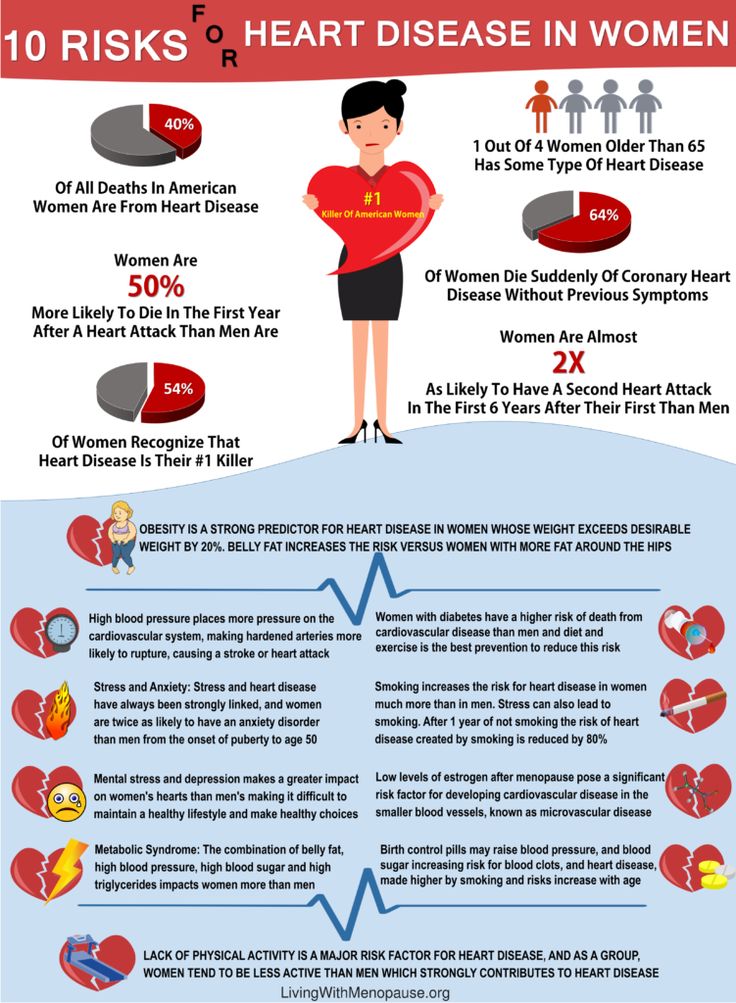

Depression currently affects about 25% of individuals with diabetes, a population more susceptible to pronounced blood sugar highs and lows.

1 The diabetic population provides valuable insight on the effects of blood sugar variability on both ends of the spectrum.

Although more studies are warranted to solidify the relationship between mood and blood sugar, considering dietary and lifestyle implications on common mood disorders can rule out lesser known causes.

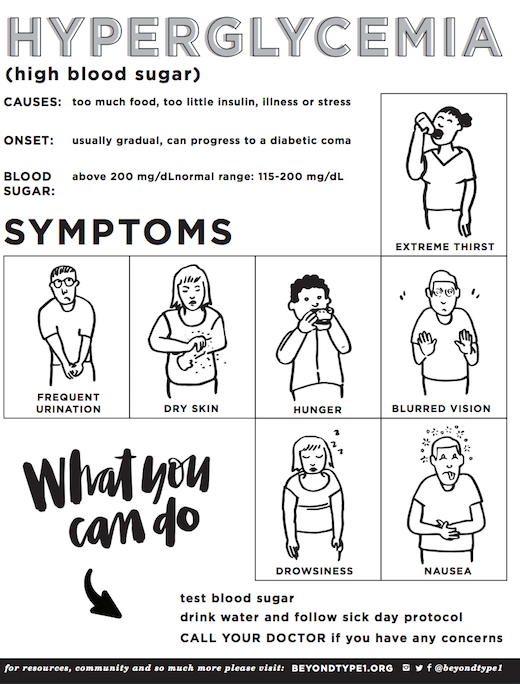

One study found that inconsistent blood sugar levels among women with diabetes were associated with lower quality of life and negative moods.2 Among diabetic, higher blood glucose, or hyperglycemia, has historically been associated with anger or sadness, while blood sugar dips, or hypoglycemia, has been associated with nervousness.3

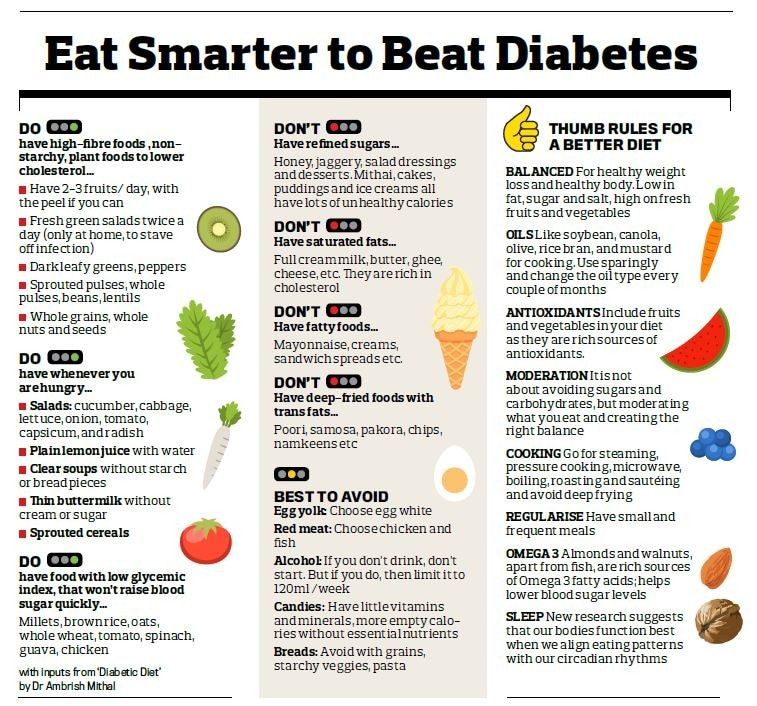

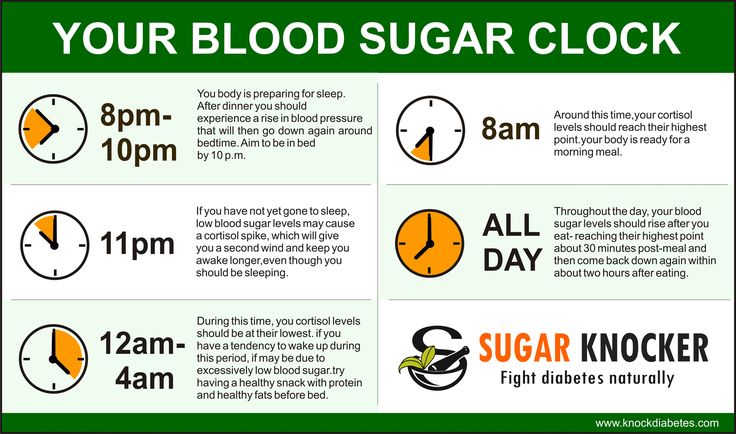

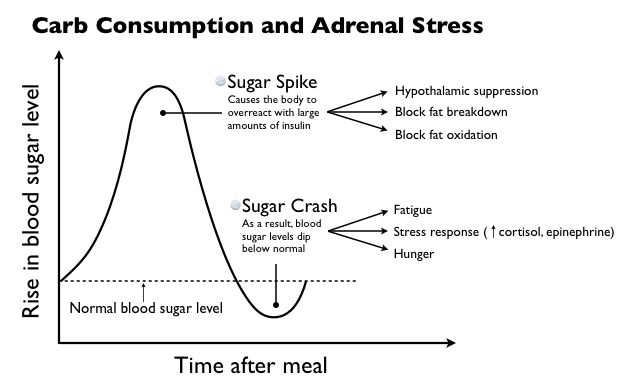

Persons with diabetes are not the only ones vulnerable to mood disturbances as a result of blood sugar fluctuations. Otherwise healthy individuals consuming a diet high in refined carbohydrates and added sugars may experience a sudden surge in their blood sugar, followed by an exaggerated insulin response, leading to acute hypoglycemia.4

Otherwise healthy individuals consuming a diet high in refined carbohydrates and added sugars may experience a sudden surge in their blood sugar, followed by an exaggerated insulin response, leading to acute hypoglycemia.4

A 2017 prospective study found positive associations between high sugar consumption and common mental disorders, concluding that sugar intake from sweet foods and beverages has an adverse effect on long-term psychological health.5

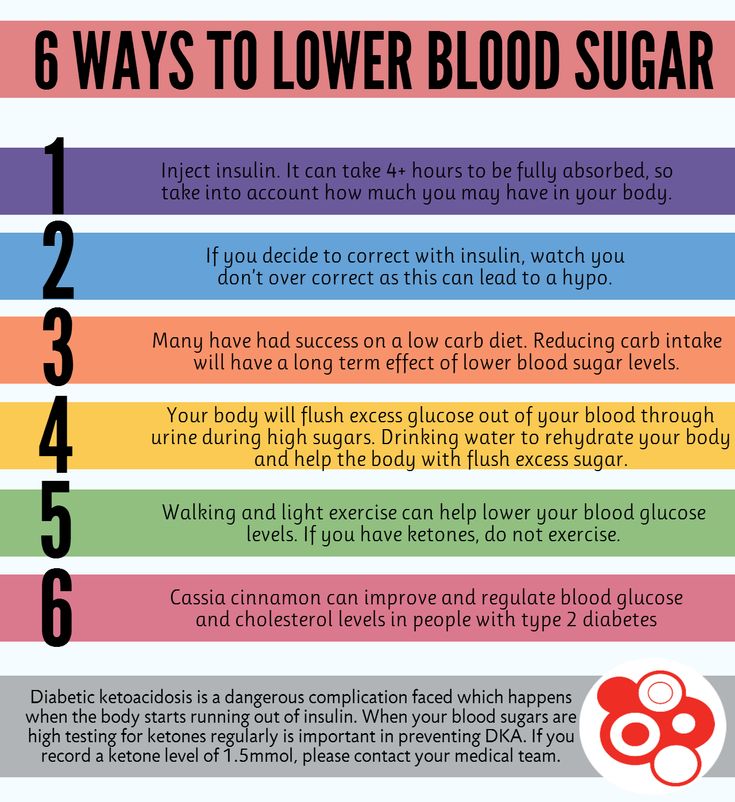

Individuals with recurrent mental health symptoms may choose to rule out alternative causes before jumping into mental health treatment or interventions. Several lifestyle principles can help stabilize blood sugar:

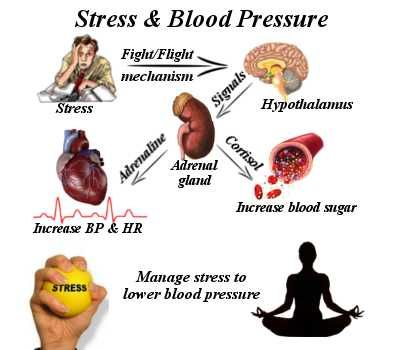

- Reduce and manage stress.

Stress has been shown to negatively affect the regulation of blood glucose. Specifically, hormonal changes during acute and chronic stress can affect glucose balance.6

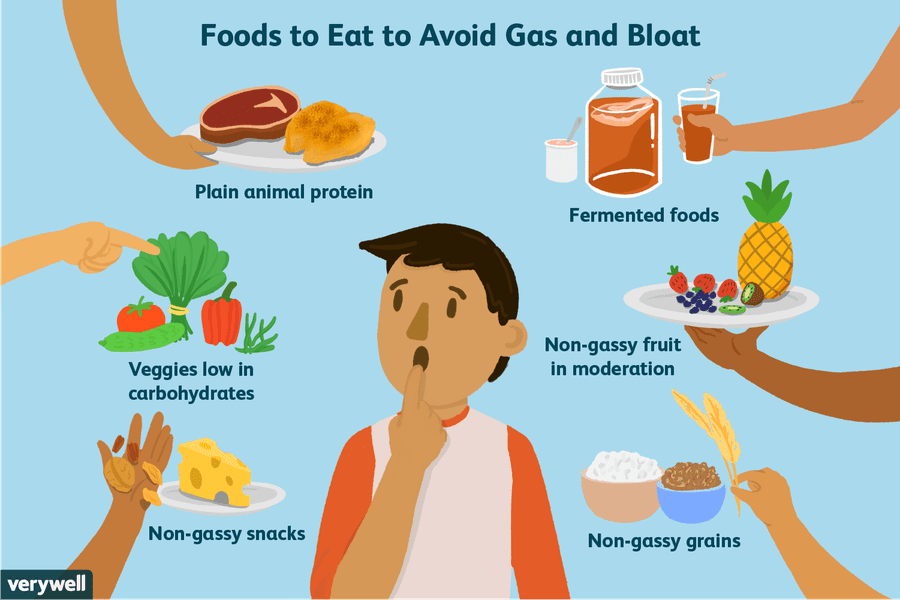

Stress has been shown to negatively affect the regulation of blood glucose. Specifically, hormonal changes during acute and chronic stress can affect glucose balance.6 - Increase intake of protein and fiber. Protein has a low glycemic index (GI), which means they have a low impact on blood sugar levels. Fibrous foods are also shown to have a lower GI value when compared to their refined counterparts.7

- Reduce intake of sweet beverages and refined carbohydrates. A diet high in refined carbohydrates, including sweet beverages, has a high GI value and is associated with unstable blood sugar regulation.4,7

Although more studies are warranted to solidify the relationship between mood and blood sugar, considering dietary and lifestyle implications on common mood disorders can rule out lesser known causes.

References

- Anderson RJ. Freedland KE. Clouse RE. Lustman PJ. The prevalence of comorbid depression in adults with diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2001;24:1069–1078. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1069

- Penckofer S, Quinn L, Byrn M, Ferrans C, Miller M, Strange P. Does glycemic variability impact mood and quality of life?. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2012;14(4):303–310. doi: 10.1089/dia.2011.0191

- Gonder-Frederick LA. Cox DJ. Bobbit SA. Pennebaker JW. Mood changes associated with blood glucose fluctuations in insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. Health Psychol.

1989;8:45–59.

1989;8:45–59. - Schwartz NS, Clutter WE, Shah SD, Cryer PE. Glycemic thresholds for activation of glucose counterregulatory systems are higher than the threshold for symptoms. J Clin Invest. 1987;79(3):777–781. doi:10.1172/JCI112884

- Knüppel A, Shipley MJ, Llewellyn CH, Brunner EJ. Sugar intake from sweet food and beverages, common mental disorder and depression: prospective findings from the Whitehall II study. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):6287. Published 2017 Jul 27. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-05649-7

- Marcovecchio, ML.

Chiarelli, F. The effects of acute and chronic stress on diabetes control. Sci Signal 5. 2012; 10. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003508

Chiarelli, F. The effects of acute and chronic stress on diabetes control. Sci Signal 5. 2012; 10. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.2003508 - Atkinson FS. Foster-Poell K. Brand-Miller JC. Glycemic index (GI) and glycemic load (GL) values determined in subjects with normal glucose tolerance: 2008. Diabetes Care. 2008;31(12):2281-3. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1239

- Interested in public health? Learn more.

- Read more about nutrition and dietetics in public health.

- Support students at Michigan Public Health.

About the Author

Isa Kay, MPH, RDN is a Registered Dietitian Nutritionist and completed her Master’s of Public Health in Nutritional Sciences from the University of Michigan School of Public Health. She is also a Navy veteran, yogi, and integrative health coach. Treating the body as an interconnected whole, Isa links nutrition with brain health, mood, and mental wellbeing. Her continued interests include the emerging field of nutritional psychiatry, functional medicine, and the gut-brain axis. You can follow Isa on social media at @meanutrition.

Tags

- Alumni

- Nutritional Sciences

- Mental Health

- Nutrition

The Link Between Hypoglycemia and Depression

Helen came to The Center • A Place of HOPE suffering from anxiety and depression. Her moods swung from hopelessness and lethargy to being stressed out and anxious. If it wasn’t one, it was the other. Both were taking their toll, and she wanted an end to them.

Her moods swung from hopelessness and lethargy to being stressed out and anxious. If it wasn’t one, it was the other. Both were taking their toll, and she wanted an end to them.

Helen was tired of never feeling settled. She had become terrified she was bipolar because of her roller-coaster moods. It was this fear that finally propelled her into counseling. In addition to her therapy, Helen set up an appointment to see our nutritionist. What was mysterious to her was obvious to him. Helen had hypoglycemia, which was a major source of her depression and anxiety.

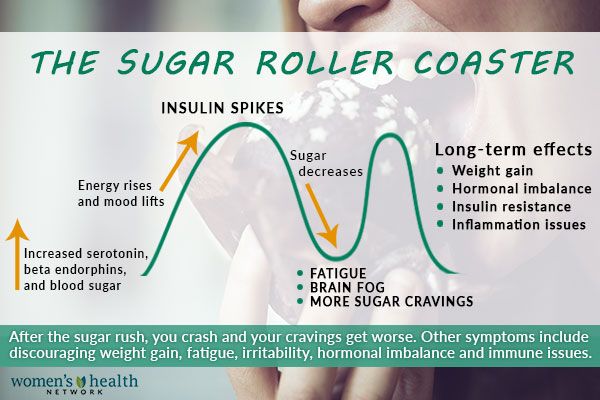

Over the course of her adult life, Helen developed a pattern based upon her eating habits and food choices. She preferred quick, calorie-rich foods, eaten sporadically, with large amounts of caffeine throughout the day. Because she worked for a newspaper, Helen’s duties were stressful and time-sensitive. Many times she put off eating, subsisting instead on high-caffeine beverages and sweets, consumed on the run. The caffeine and sweets propelled her headlong into nervousness and anxiety as her blood sugar levels spiked. The resulting crash of insulin to counter this massive sugar dump in her system brought feelings of depression and physical depletion. At these low times, Helen doubted her abilities, fretted over her age, and raged over any mistake. When Helen hit rock bottom, she questioned whether she was really capably of doing her high-stress, high-profile job. Her body was playing right into her fears of unworthiness and inadequacy to handle her job.

The caffeine and sweets propelled her headlong into nervousness and anxiety as her blood sugar levels spiked. The resulting crash of insulin to counter this massive sugar dump in her system brought feelings of depression and physical depletion. At these low times, Helen doubted her abilities, fretted over her age, and raged over any mistake. When Helen hit rock bottom, she questioned whether she was really capably of doing her high-stress, high-profile job. Her body was playing right into her fears of unworthiness and inadequacy to handle her job.

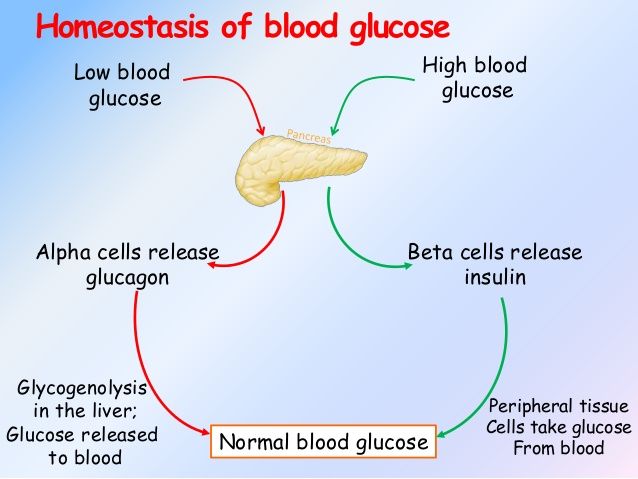

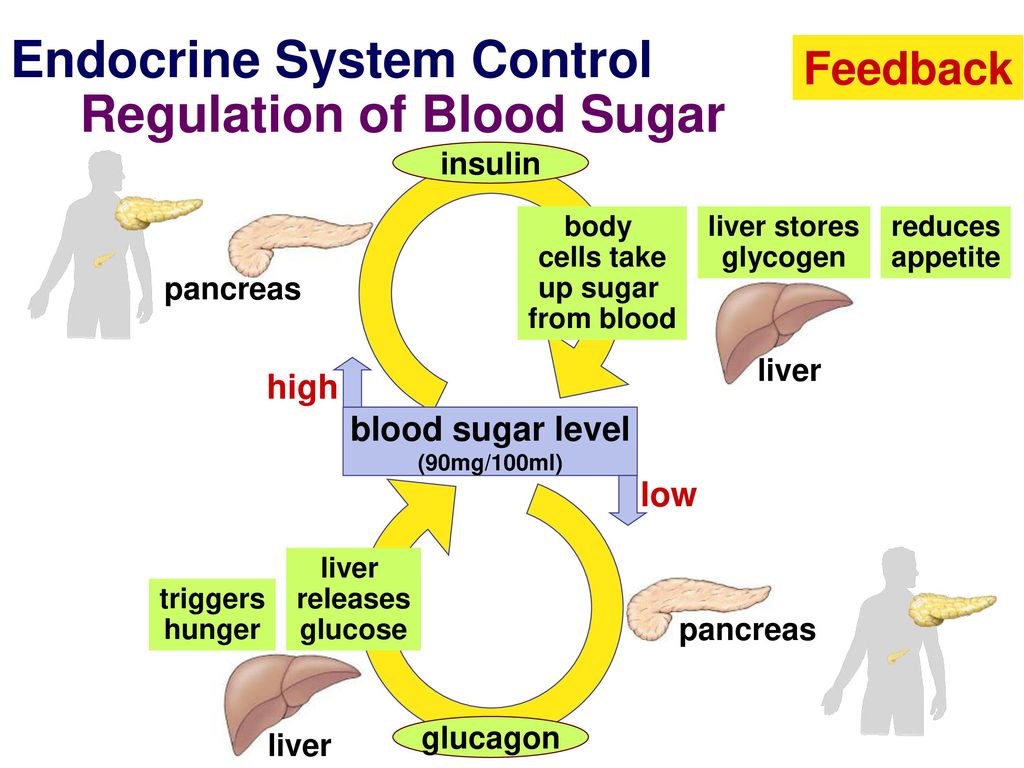

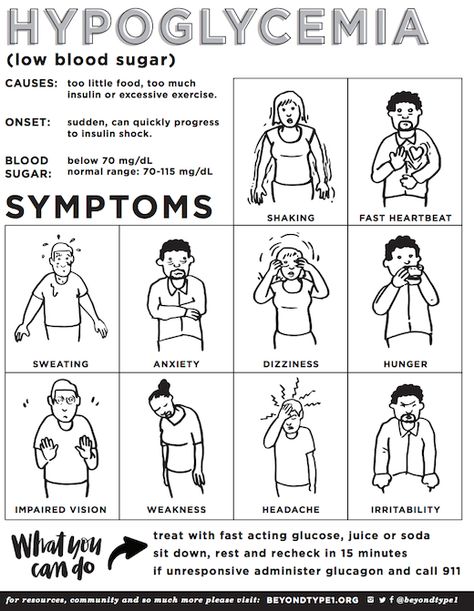

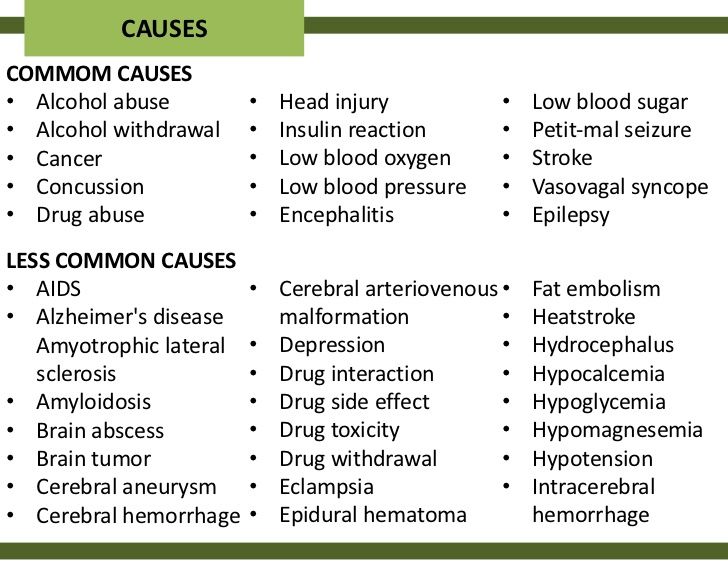

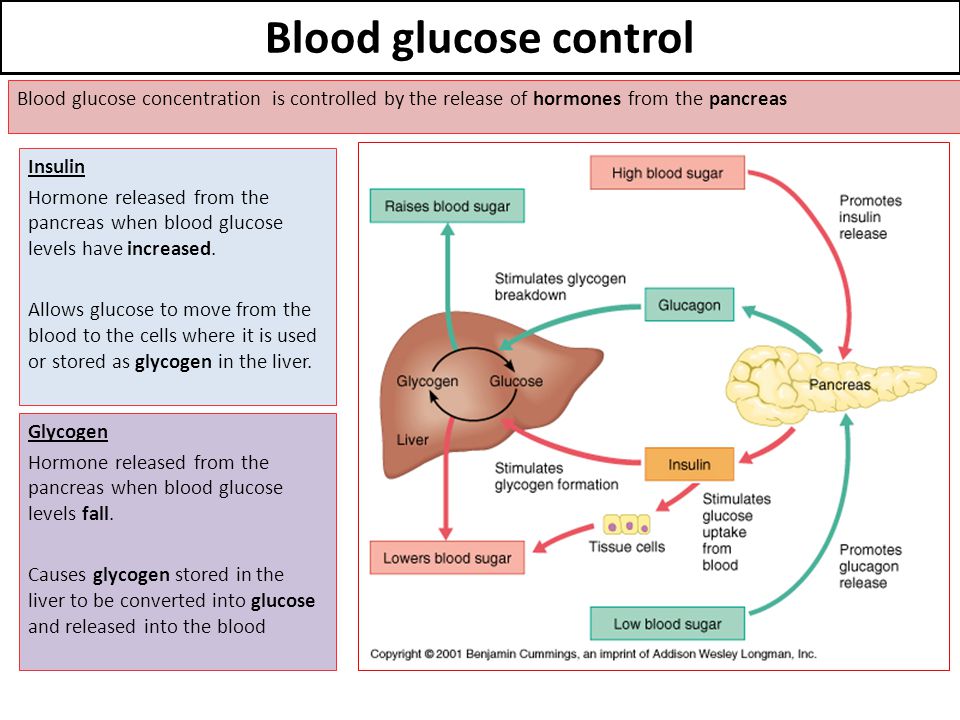

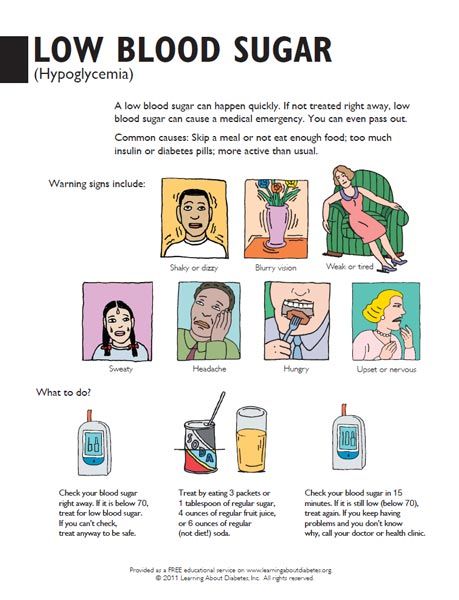

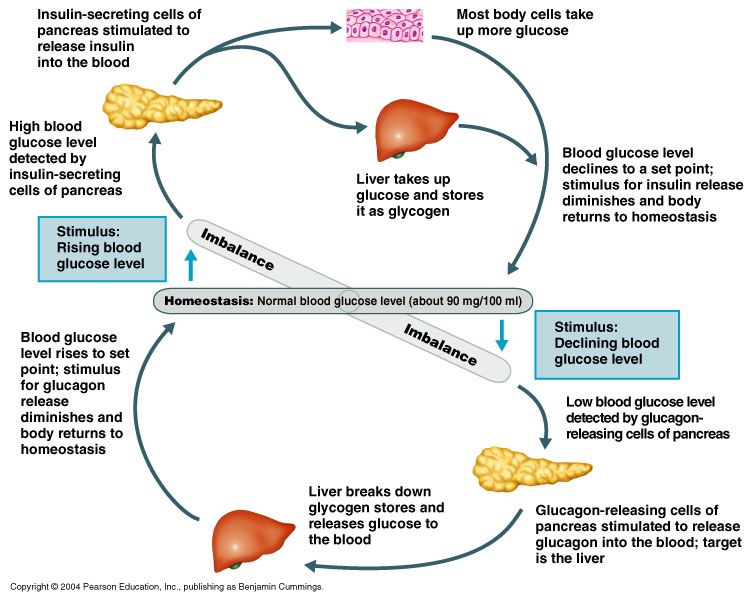

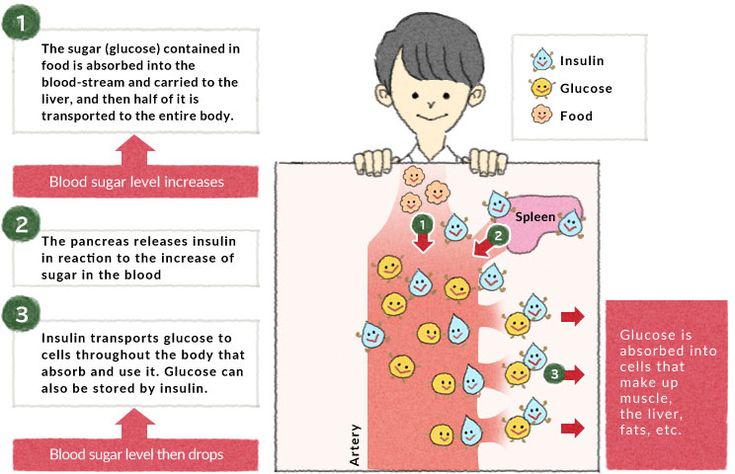

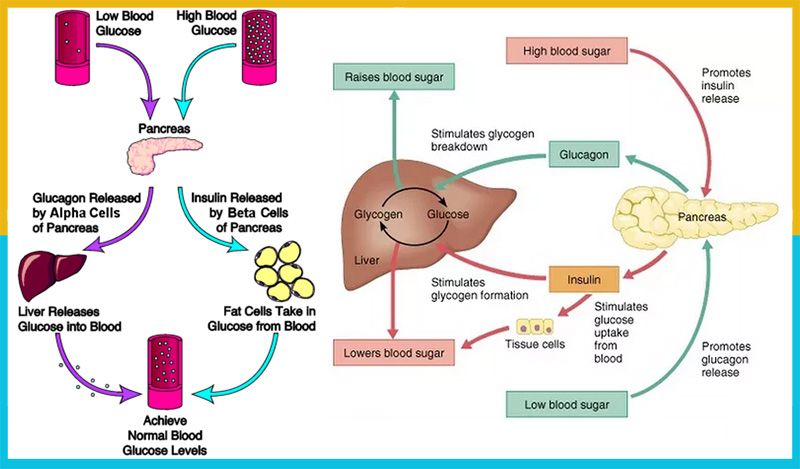

Hypoglycemia is more commonly known as low blood sugar or the “sugar blues.” The body’s main source of fuel is glucose, which is a form of sugar. Glucose is produced by the body through the consumption of carbohydrates, sugars, and starches. Glucose is absorbed into the bloodstream during digestion. Glucose that is not needed is stored in the liver as glycogen. When the amount of sugar in the blood is insufficient to fuel the body’s activities, hypoglycemia occurs. While this condition has been universally accepted as a cause of depression, even skeptics will agree that hypoglycemia can cause weakness, mental dullness, confusion, and fatigue. All of these symptoms, when taken together, can exacerbate depression.

While this condition has been universally accepted as a cause of depression, even skeptics will agree that hypoglycemia can cause weakness, mental dullness, confusion, and fatigue. All of these symptoms, when taken together, can exacerbate depression.

Some in the medical community, especially those schooled in holistic medicine, do make the connection between depression and hypoglycemia, including the U.S. National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health. [1]

Food and caffeine became Helen’s drugs of choice. Food, so abundant in this country, is often used as a form of self-medication and comfort, especially high-sugar, high-fat foods. These foods flood the bloodstream with an energy surge. While using food to treat feelings of depression may prove temporarily effective, the resulting crash of low blood sugar can make you feel even worse. As you look at your own cycles of depression, look for a connection between what you eat and how you feel.

Here are common signs of hypoglycemia:

- headache

- nervousness

- confusion or disorientation

- hunger

- weakness

- rapid heart beat

- slurred speech

- tingling lips

- sweating

If you find yourself having feelings of hopelessness, stress, anxiety, and depression, The Center • A Place of HOPE can help. Call us at 1-888-771-5166 to speak confidentially with a specialist. Or view our depression treatment page for further information.

Call us at 1-888-771-5166 to speak confidentially with a specialist. Or view our depression treatment page for further information.

[1] M. J. Park, S. W. Yoo, B. S. Choe, R. Dantzer, and G. G. Freund, “Acute Hypoglycemia Causes Depressive-Like Behavior in Mice,” Metabolism 61, no. 2 (February 2012): 229-36, summarized at U.S. National Library of Medicine National Institutes of Health, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21820138

Diabetes and depression | #01/14

| In recent decades, the attention of researchers around the world has attracted the frequent combination of diabetes and depression. The article presents the main historical information on this issue, outlines modern hypotheses about the reasons for the frequent association of violations |

#01/14 Keywords / keywords: Behavior, Complications, Depressions, Diabetes mellitu, History, Hyperglycemias, Lifestyle modifications, Mood, Pathogenesi, Perception of diagnosis, Psychic trauma, Stres, Perception of diagnosis, Hyperglycemia, Depression, History, Lifestyle modifications, Mood, Complications, Pathogenesis, Behavior, Mental Trauma, Diabetes Mellitus, Stress, Depressions, Diabetes mellitu, Hyperglycemias, lifestyle modifications, Pathogenesi, Stres, Hyperglycemia, Depression, Complication, Pathogenesis, Diabetes mellitus, Stress

N. V. Vorokhobina, S. N. Vogt, E. A. Volkova, F. V. Shadricheva

V. Vorokhobina, S. N. Vogt, E. A. Volkova, F. V. Shadricheva

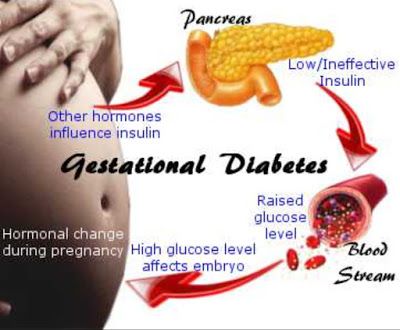

Diabetes mellitus (DM) and depression are widespread and socially significant diseases. It is interesting that, despite the huge number of works devoted to the study of the causes of these conditions, the modern view of the etiology of both DM and depression leaves many unanswered questions. In recent decades, the attention of researchers around the world has attracted the frequent association of these two diseases. It was found that a patient with depression has an increased risk of developing disorders of carbohydrate metabolism, and among patients with diabetes, a persistent decrease in mood is more common [1]. Considering that in children born today, the estimated lifetime risk of developing diabetes is more than 35%, finding a pathogenetic relationship between carbohydrate metabolism disorders and depression, as well as developing an approach to treating patients with both diseases, seems to be very promising areas of scientific work [ one].

It is curious that the first description of the combination of diabetes and depression in a patient, noted by Willis in 1684, was characterized by the author as having a clear relationship [2]. The researcher pointed out that the violation of carbohydrate metabolism is a consequence of "grief and long-term sadness." For the next several centuries, depression was seen only as a consequence of the patient's experiences and worries related to diabetes mellitus. Scientific interest has been limited to the publication of data from epidemiological studies indicating a slight increase in the prevalence of affective disorders in patients with impaired carbohydrate metabolism. At 19In 1988, it was probably the first suggestion that depression can reduce the sensitivity of peripheral tissues to insulin [3]. R. W. Turkington published the results of the use of antidepressants in patients with type 2 diabetes with neuropathy. The use of pharmacological agents had an effect on both the severity of depression and pain syndrome [4].

In 1996, the results of a prospective follow-up of 1715 patients with depression for 13 years were published [5]. The author of the study, W. W. Eaton, who conducted his work at a high methodological level, indicated that the risk of developing type 2 diabetes in depression is higher than in the general population. The data obtained by W. W. Eaton were rechecked by other researchers and organizations, after which the scientific interest in the problem under consideration increased many times [1]. Many original and meta-analytical studies have been carried out, during which it was found that depression and DM often accompany each other [1, 5].

Despite the large number of works on the issue under consideration, a significant part of the authors limited themselves to a retrospective analysis of the data, as a result of which the causal relationship between depression and DM remained not completely clear. The results of a large meta-analysis of prospective studies published in 2008 indicate that patients with depression are at high risk of developing disorders of carbohydrate metabolism. It has been found that patients with type 2 diabetes often develop depression, but there is only a moderate increase in the risk of this disease compared with the rates in the population [6].

It has been found that patients with type 2 diabetes often develop depression, but there is only a moderate increase in the risk of this disease compared with the rates in the population [6].

The development of carbohydrate metabolism disorders in patients with depression may be associated with several factors. First, behavioral features in depression often include increased cigarette consumption, reduced physical activity, and dietary changes. These factors can provoke the development of DM and exacerbate the course of already developed disorders of carbohydrate metabolism [7]. Secondly, features of the pathophysiology of depression include activation of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal cortex, sympathoadrenal system, and the formation of pro-inflammatory cytokines [8]. These phenomena can lead to a decrease in the sensitivity of peripheral tissues to insulin, as well as a decrease in hormone secretion in β-cells of the islets of Langerhans. In addition, hypercortisolism is associated with the development of abdominal obesity, which is a known adverse factor in relation to the risk of type 2 diabetes [9].

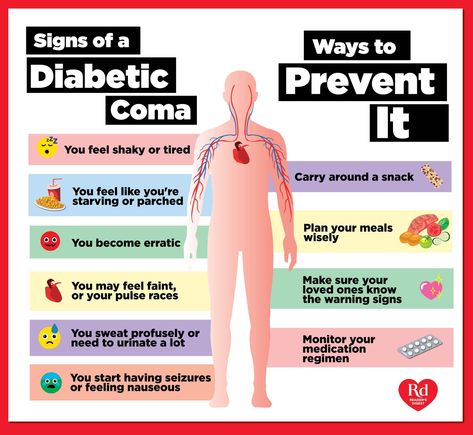

In a patient with diabetes, in turn, there are several factors that can lead to depression. DM is a chronic progressive disease. After diagnosis, patients should independently control glycemia, take pharmacological drugs, restrict diet, increase physical activity, make more frequent visits to the doctor to correct treatment and examination. Some patients have a fear of diabetic complications and a fear of hypoglycemia. Thus, awareness of DM and the need for lifestyle changes can lead to depression [6, 10]. A WHO study shows that when a patient has diabetes and depression, the feeling that their health has deteriorated is more pronounced than when depression is combined with other chronic diseases, such as coronary heart disease, arthritis, and bronchial asthma [11].

This theory is supported by the data of A. Nouwen et al. [ten]. The authors found that patients with undiagnosed type 2 diabetes were less likely to suffer from depression than patients with an established diagnosis. However, it should be taken into account that patients with undiagnosed disorders of carbohydrate metabolism had significantly fewer diabetic complications and, probably, the disease was more compensated.

However, it should be taken into account that patients with undiagnosed disorders of carbohydrate metabolism had significantly fewer diabetic complications and, probably, the disease was more compensated.

Gonzales J. S. et al. data were obtained indirectly indicating that the influence of experiences in connection with the developed diabetes is not a prerogative for depression. After conducting a large meta-analysis, the authors indicate that when comparing populations of patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes, as well as adolescents and adults, there are no differences in the course of depression [12]. It is logical to assume that the perception of the diagnosis and lifestyle modifications will differ with different pathogenesis of diseases and different ages at their debut.

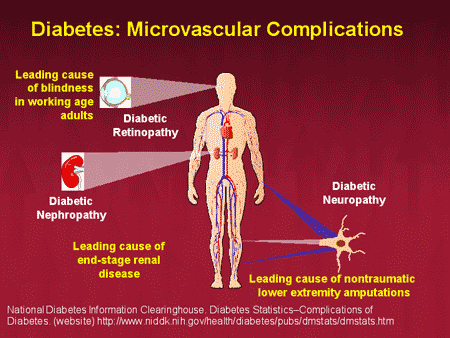

A special role is given to the combination of depression and complicated DM. A number of authors indicate that chronic diabetic complications are associated with a high risk of depression [13]. Retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and macrovascular complications have been shown to influence the likelihood of depressive symptoms. Probably, the symptoms of the disease and the awareness of the presence of a potentially formidable complication lead to depression in a nonspecific way [13].

Retinopathy, nephropathy, neuropathy, and macrovascular complications have been shown to influence the likelihood of depressive symptoms. Probably, the symptoms of the disease and the awareness of the presence of a potentially formidable complication lead to depression in a nonspecific way [13].

The literature considers whether the pathophysiological features of the course of DM can lead to depression, but there is not much data on this issue. It is assumed that chronic sluggish inflammation and impaired trophism of the nervous tissue in DM can lead to a decrease in the plasticity of the nervous system [14, 15] and, subsequently, to depression [16]. It is worth mentioning that the presence of chronic diabetic complications in a patient is associated with an increase in the level of cortisol in the blood [17]. Hypercortisolism may play an additional role in the pathogenesis of depression [9].

There is another hypothesis that combines type 2 diabetes and depression. Its essence is that stress can cause both of these diseases [18]. Various researchers have found an association of carbohydrate metabolism disorders with a history of psychic trauma [19], parental neglect in childhood [20], as well as with aggressive behavior [21] and sleep disturbance [22]. Possible mechanisms of the influence of stress on the risk of developing carbohydrate metabolism disorders include an unhealthy lifestyle in patients (smoking, alcoholism, an inappropriate diet, low physical activity, etc.) [18], as well as an increase in insulin resistance and the development of abdominal obesity due to hypercortisolism [9]. This theory, however, does not explain the absence of significant differences in the prevalence of depression among patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

Its essence is that stress can cause both of these diseases [18]. Various researchers have found an association of carbohydrate metabolism disorders with a history of psychic trauma [19], parental neglect in childhood [20], as well as with aggressive behavior [21] and sleep disturbance [22]. Possible mechanisms of the influence of stress on the risk of developing carbohydrate metabolism disorders include an unhealthy lifestyle in patients (smoking, alcoholism, an inappropriate diet, low physical activity, etc.) [18], as well as an increase in insulin resistance and the development of abdominal obesity due to hypercortisolism [9]. This theory, however, does not explain the absence of significant differences in the prevalence of depression among patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

The presence of depression in a patient with DM is characterized by worsened compensation of the disease [23], an increased risk of developing chronic diabetic complications [13], a decrease in patient compliance [12], as well as a decrease in the quality of life [24] and an increase in mortality [25]. Health care costs for patient treatment increase on average by 50–75% [26].

Health care costs for patient treatment increase on average by 50–75% [26].

Depression is a common psychiatric disorder in diabetic patients. In modern conditions, a decrease in mood in a patient with diabetes is considered as a normal psychological reaction of the patient, and the symptoms of depression go unnoticed. Considering the clinical and economic consequences of the combination of diabetes and depression, the introduction of simple, affordable methods for diagnosing mental illness should be considered appropriate. In addition, despite the large number of studies devoted to the study of the mechanisms of the combination of DM and depression, many questions require further research work.

Literature

- Lustman P. J., Penckofer S. M., Clouse R. E. Recent Advances in Understanding Depression in Adults with Diabetes // Curr. Diab. Rep. 2007 Vol. 7. No. 2. P. 114–122.

- Diabetes: A Medical Odyssey / ed.

T. Willis. New York: Tuckahoe, 1971.

T. Willis. New York: Tuckahoe, 1971. - Winokur A., Maislin G., Phillips J. L., Amsterdam J. D. Insulin resistance after oral glucose tolerance testing in patients with major depression // Am. J. Psychiatry. 1988 Vol. 145. P. 325–330.

- Turkington R. W. Depression masquerading as diabetic neuropathy // JAMA. 1980 Vol. 243. P. 1147-1150.

- Eaton W. W., Armenian H. A., Gallo J. Depression and risk for onset of type II diabetes: a prospective population-based study // Diabetes Care. 1996 Vol. 19. P. 1097–1102.

- Mezuk B., Eaton W. W., Albrecht S., Golden S. H. Depression and Type 2 Diabetes Over the Lifespan // Diabetes Care. 2008 Vol. 31. P. 2383–2390.

- Strine T., Mokdad A., Dube S., Balluz L., Gonzalez O., Berry J., Manderscheid R., Kroenke K . The association of depression and anxiety with obesity and unhealthy behaviors among community-dwelling US adults // Gen.

hosp. Psychiatry. 2008 Vol. 30. P. 127–137.

hosp. Psychiatry. 2008 Vol. 30. P. 127–137. - Golden S. H. A review of the evidence for a neuroendocrine link between stress, depression and diabetes mellitus // Curr. Diabetes Rev. Vol. 3. P. 252–259.

- Björntorp P. Do stress reactions cause abdominal obesity and comorbidities? // obes. Rev. 2001 Vol. 2. P. 73–86.

- Nouwen A., Nefs G., Caramlau I., Connock M., Winkley K., Lloyd C. E., Peyrot M., Pouwer F. Prevalence of Depression in Individuals With Impaired Glucose Metabolism or Undiagnosed Diabetes // Diabetes Care. 2011 Vol. 34. P. 752–762.

- Moussavi S., Chatterji S., Verdes E., Tandon A., Patel V., Ustun B. Depression, chronic diseases, and decrements in health: results from the World Health Surveys // Lancet. 2007 Vol. 379. P. 851–858.

- Gonzalez J. S., Peyrot M., McCarl L. A., Collins E. M., Serpa L., Mimiaga M. J., Safren S. A. Depression and Diabetes Treatment Nonadherence: A Meta-Analysis // Diabetes Care.

2008 Vol. 31. P. 2398–2403.

2008 Vol. 31. P. 2398–2403. - De Groot M., Anderson R., Freedland K. E., Clouse R. E., Lustman P. J. Association of Depression and Diabetes Complications: A Meta-Analysis // Psychosomatic Medicine. 2001 Vol. 63. P. 619–630.

- Fujinami A., Ohta K., Obayashi H. Serum brain-derived neurotrophic factor in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: relationship to glucose metabolism and biomarkers of insulin resistance // Clin. Biochem. 2008 Vol. 41. P. 812–817.

- Pickup J. C. Inflammation and activated innate immunity in the pathogenesis of type 2 diabetes // Diabetes Care. 2004 Vol. 27. P. 813–823

- Castrén E., Rantamäki T. Role of brainderived neurotrophic factor in the aetiology of depression: implications for pharmacological treatment // CNS Drugs. 2010 Vol. 24. P. 1–7.

- Chiodini I., Adda G., Scillitani A., Coletti F., Morelli V., Di Lembo S., Epaminonda P.

, Masserini B., Beck-Peccoz P., Orsi E., Ambrosi B., Arosio M Cortisol secretion in patients with type 2 diabetes: relationship with chronic complications // Diabetes Care. 2007 Vol. 30. No. 1. P. 83–88.

, Masserini B., Beck-Peccoz P., Orsi E., Ambrosi B., Arosio M Cortisol secretion in patients with type 2 diabetes: relationship with chronic complications // Diabetes Care. 2007 Vol. 30. No. 1. P. 83–88. - Pouwer F. Does Emotional Stress Cause Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus? A Review from the European Depression in Diabetes (EDID) Research Consortium // Discovery Medicine. 2010 Vol. 45. P. 112–118.

- Mooy J. M., De Vries H., Grootenhuis P. A., Bouter L. M., Heine R. J. Major stressful life events in relation to prevalence of undetected type 2 diabetes The Hoorn Study // Diabetes Care. 2000 Vol. 23. P. 197–201.

- Goodwin R. D., Stein M. B. Association between childhood trauma and physical disorders among adults in the United States // Psychol. Med. 2004 Vol. 34. P. 509–520.

- Golden S. H., Williams J. E., Ford D. E., Yeh H.-C., Paton-Sanford C., Javier-Nieto F., Brancati F. L. Anger temperament is modestly associated with the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: The atherosclerosis risk in communities study // Psychoneuroendocrinology.

2006 Vol. 31. P. 325–332.

2006 Vol. 31. P. 325–332. - Cappuccio F. P., D’Elia L. D., Strazzullo P., Miller M. A. Quantity and quality of sleep and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis // Diabetes Care. 2010 Vol. 33. P. 414–420.

- Lustman P. J., Anderson R. J., Freedland K. E., de Groot M., Carney R. M., Clouse R. E. Depression and poor glycemic control: a meta-analytic review of the literature // Diabetes Care. 2000 Vol. 23. P. 434–442.

- Wexler D. J., Grant R. W., Wittenberg E., Bosch J. L., Cagliero E., Delahanty L., Blais M. A., Meigs J. B. Correlates of health-related quality of life in type 2 diabetes // Diabetologia. 2006 Vol. 49. P. 1489–1497.

- Van Dooren F. E. P., Nefs G., Schram M. T., Verhey F. R. J., Denollet J., Pouwer F. Depression and Risk of Mortality in People with Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis // Plos One. 2013. Vol. 8.Issue 3.

- Simon G. E., Katon W. J., Lin E. H., Ludman E., VonKorff M., Ciechanowski P. Diabetes complications and depression as predictors of health service costs // Gen. hosp. Psychiatry. 2005 Vol. 27. No. 5. P. 344–351.

N. V. Vorokhobina, Doctor of Medical Sciences, Professor

S. N. Vogt, Candidate of Medical Sciences

E. A. Volkova, Candidate of Medical Sciences

F. V. Shadricheva

St. Petersburg

1 Contact information: [email protected]

abstract. In recent decades the attention of many authors around the world is drawn by frequent association of diabetes mellitus and depression. The article presents the basic historical information on the subject, describes the modern hypotheses about the causes of the frequent association of disorders of carbohydrate metabolism and mood disorders. Pathogenetic aspects of depression that can lead to diabetes are considered. Article presents the data on how hyperglycemia, perception of diagnosis, lifestyle modification and the presence of diabetic complications can affect mood in patients with diabetes mellitus. Also a hypothesis about the role of stress in the etiology of diabetes and depression is considered.

Pathogenetic aspects of depression that can lead to diabetes are considered. Article presents the data on how hyperglycemia, perception of diagnosis, lifestyle modification and the presence of diabetic complications can affect mood in patients with diabetes mellitus. Also a hypothesis about the role of stress in the etiology of diabetes and depression is considered.

Buy issue with this article in pdf

field required field

mandatory

field required

SpecializationObstetrician-gynecologistAllergologistGastroenterologistHematologistHepatologistDermato-venereologistCardiologistNeurologistNeurosurgeonInfectionistOncologistOtolaryngologistOphthalmologistPediatricianPsychiatristPulmonologistProctologistRheumatologistRadiologist and RadiologistTherapist and General PractitionerUrologistPhthisiatricianSurgeonEndocrinologistOther 9001 field 9001 mandatory

By clicking on the Subscribe button, you consent to the processing of personal data

Hypoglycemia - All About Diabetes

Hypoglycemia is a condition when blood glucose (sugar) is low. In a person with diabetes, hypoglycemia can be caused by not eating enough, exercising without proper nutrition, or taking inappropriate medication. Hypoglycemia is a health threat and has a significant impact on the lives of people with diabetes.

In a person with diabetes, hypoglycemia can be caused by not eating enough, exercising without proper nutrition, or taking inappropriate medication. Hypoglycemia is a health threat and has a significant impact on the lives of people with diabetes.

Normally, hypoglycemia means a blood sugar level below 3.9 mmol/l, and measures must be taken to normalize it. However, your personal low blood glucose threshold may differ from the standard values. Discuss this point with your doctor and find out what blood glucose level can indicate the development of hypoglycemia in you. 2

Hypoglycemia can pose a serious threat to human health and life, even one episode is already too many. Therefore, it is so important to learn more about this condition and how to identify it, how to deal with it, and how you can prevent a critical drop in blood sugar levels.

Causes of hypoglycemia

For people with diabetes, there are a number of situations where blood glucose drops too much. Among them:

Among them:

- Medication effects: Blood sugar can drop critically when high doses of antidiabetic drugs such as insulin or tablets are taken, or when they interact with certain other drugs. Certain antiviral drugs used to treat hepatitis C also cause glucose levels to drop.

- Eating disorders: Skipping or delaying breakfast, lunch, or dinner causes a drop in blood glucose in a person with diabetes.

- Insufficient carbohydrate intake . For example, foods such as: bread, cereals, pasta, potatoes and fruits.

- Physical exercise: more intense than usual physical activity, especially unscheduled, significantly affects blood sugar levels.

- Drinking alcohol: Alcohol can cause low blood sugar levels. 5

- Environmental changes eg warm and humid weather, exposure to high altitude.

- Special physical condition eg menstruation.

Also read: Hypoglycemia. Risks beyond and beyond our control

Increased risk of hypoglycaemia

Some people with diabetes may be at increased risk of hypoglycaemia, such as: 9-13

- blood glucose, especially when taking certain antidiabetic drugs.

- People with a significant duration of diabetes, especially if hypoglycemia is not recognized.

- People who are unaware of hypoglycemia and its symptoms.

- Elderly people.

- Children, especially young children, with type 1 diabetes.

- Adolescents during puberty.

- Pregnant women with diabetes, especially in the first trimester of pregnancy.

- People with kidney, liver and heart failure.

- Obese people .

- People on certain antihypertensive drugs.

- People with depression.

- People with cognitive dysfunction.

- People with peripheral neuropathy.

- People whose lifestyle increases the risk of developing hypoglycemia:

- adherence to strict religious fasts;

- intense physical activity during the day;

- inability to plan meals during the day;

- drinking alcohol.

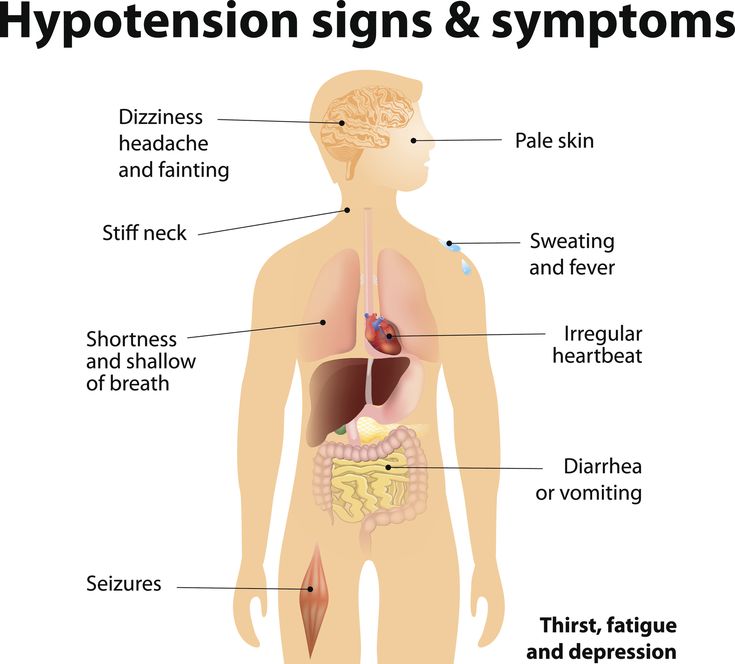

The symptoms of hypoglycemia develop quickly!!

If any measurement reveals a blood sugar level below 3.9 mmol/l , action must be taken immediately to prevent further development of hypoglycemia.

The first symptoms of hypoglycemia are most often blamed for blood glucose levels lower than 3.5 mmol/l So, for one person, hypoglycemia is a glucose level of 4.5 mmol / l, and for another - 2 mmol / l. It depends on the characteristics of a particular person and on what normal blood sugar level his body lives with and what he is used to adapting to. If a person has predominantly hyperglycemia (i.e. elevated blood sugar levels), then even a level of 5 mmol / l for him can be a state of hypoglycemia. Therefore, it is very important to discuss with your doctor the possible development of hypoglycemia in you.

The body responds to a decrease in blood sugar levels by synthesizing adrenaline, a hormone of critical conditions that requires the mobilization of all systems in order to avoid a threat. 3

3

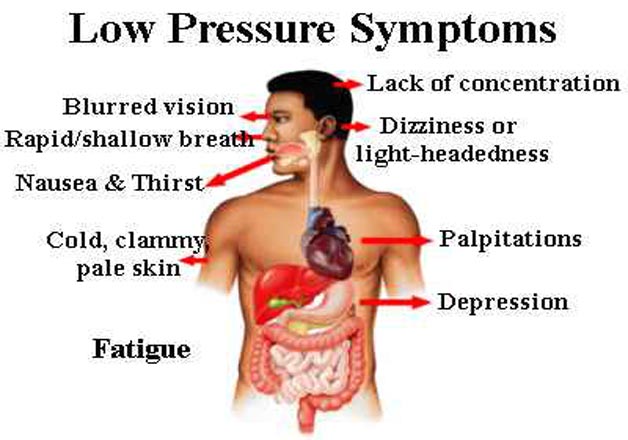

Adrenaline causes a number of symptoms of hypoglycemia, such as:

- palpitations;

- excessive sweating;

- tingling sensation in the body;

- Uncharacteristic anxiety for you.

If the blood glucose level continues to drop, other symptoms occur:

- blurred vision;

- decreased mental concentration and impaired attention;

- confusion;

- speech problems;

- pathological desire to sleep;

- numbness of body parts.

This means that glucose enters the brain in an extremely small amount, and its deficiency causes more and more dangerous disorders in the body. A “hungry” brain reacts to a pathological condition with convulsions and subsequent coma, which can even lead to death. 1

Hypoglycemia may occur during sleep. Low blood sugar can keep a person awake at night, cause headaches and fatigue in the morning, or cause sweaty laundry. 5

5

Read more in resource Symptoms of Hypoglycemia

What Others May Notice

- Slurred speech;

- inappropriate behavior;

- excitement;

- tearfulness;

- aggressiveness;

- inability to concentrate;

- pallor.

Inform relatives, friends, colleagues about the possibility of developing hypoglycemia and about the necessary assistance from them.

A person with hypoglycemia can feel like being drunk, and in some situations they may not get the help they need in a timely manner. Carry a person with diabetes badge or bracelet with you at all times. A medical card with your details, address, phone number of a doctor and a loved one, indicating that you have diabetes, what medications you are taking and what help you need can help.

Be attentive to yourself and others! A person who has passed out on the street may need help. And your indifference can save his life.

Latent hypoglycemia

Hypoglycemia in diabetes mellitus is a common problem that occurs more often than you think. It is also a misconception that hypoglycemia does not threaten people with type 2 diabetes who do not use insulin. But a decrease in blood sugar levels can be the result of any hypoglycemic therapy, including tablets.

It is also a misconception that hypoglycemia does not threaten people with type 2 diabetes who do not use insulin. But a decrease in blood sugar levels can be the result of any hypoglycemic therapy, including tablets.

People may either not experience symptoms of hypoglycemia (eg, at night) or they may be associated with other conditions. Thus, hypoglycemia often goes unrecognized. 14

Learn more about Latent Hypoglycemia

Also, studies show that most people don't tell their doctor about their symptoms. 14

Find out why silence in this case is not "gold" and how to break the wall of silence around hypoglycemia

Even one episode of hypoglycemia can affect the rest of a person's life. Therefore, it is important to know:

- You may feel afraid of another episode of hypoglycemia;

- tell your doctor about your symptoms;

- do not change your own treatment to avoid recurring episodes of hypoglycemia, as this can lead to unexpected and dangerous consequences.

Glycated hemoglobin does not always reflect episodes of hypoglycemia.

Imagine that Julia is a hypothetical 65-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes who has episodes of hypoglycemia. Although Julia feels the symptoms of hypoglycemia, she can never predict where and when it will happen. Julia's glycated hemoglobin is 7.8%. The woman was offered a round-the-clock measurement of the level of glucose in the blood, the results were plotted.

Let's compare the illustrative graphs of Julia and another person with type 2 diabetes, with the same glycated hemoglobin of 7.8%, but without episodes of hypoglycemia:

Julie's episodes of high blood sugar "compensate" the effect of episodes of hypoglycemia on the level of glycated hemoglobin. Therefore, it is important to understand that glycated hemoglobin cannot be indicative of the presence or absence of hypoglycemia.

See also: Glycated hemoglobin: when the analysis loses information

Varieties of hypoglycemia

Low blood sugar can be almost not felt, but with a subsequent decrease in its concentration, the situation worsens.

Hypoglycemia is classified according to the severity of the person's condition.

- Warning (mild hypoglycemia, glucose in the range of 3.0 - 3.8 mmol/l): manifests itself in the form of hunger, mild nervousness with possible minimal impairment of body coordination and drowsiness.

- Clinically significant (moderate hypoglycemia, glucose below 3.0 mmol / l): among the manifestations - dizziness and pronounced drowsiness, confusion and impaired speech, weakness, a feeling of severe anxiety.

- Severe hypoglycemia: characterized by significant mental and physical manifestations, requires emergency care.

Type 1 and 2 hypoglycemia can be handled by a person on their own, without outside help. However, severe hypoglycemia needs immediate help from outsiders and doctors. 4

Hypoglycemia Help

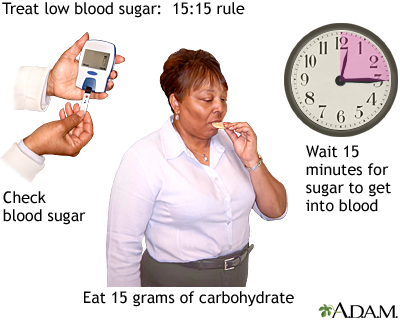

If you begin to feel the first signs of hypoglycemia, act immediately using the 15-15 Rule:

- Measure your blood sugar with a glucometer.

- If the sugar level is below 3.9 mmol/l, eat 4-5 sugar cubes or drink 200 ml of juice, eat 1 tablespoon of honey or a few sweet candies. Do not use chocolates, as chocolate raises blood sugar very slowly (after 25-30 minutes).

- Check your blood sugar after 15 minutes. If it is still below 3.9 mmol/l, repeat step 2.

- Repeat measurements and eat carbohydrate every 15 minutes until blood sugar is below 3.9 mmol/l.

Read also "Hypoglycemia SOS: how to act?"

For immediate relief of hypoglycemia, glucagon can be given intramuscularly or subcutaneously. On the recommendation of a doctor, a glucagon injection can be given not only by a healthcare professional, but also by a relative, colleague, or the person with diabetes.

Glucagon is a natural hormone produced by the pancreas that raises blood sugar levels through increased glucose production by the liver. In hypoglycemia, glucagon quickly raises blood glucose levels and the person regains consciousness 10-15 minutes after the injection. After that, you need to drink juice (sweet water) and eat a piece of bread to maintain blood sugar at the required level.

After that, you need to drink juice (sweet water) and eat a piece of bread to maintain blood sugar at the required level.

Important! Tell your doctor about your symptoms as soon as possible, even if the hypoglycemia was mild. The next episode can happen at any time and be more severe. Your doctor will be able to review and refine your treatment and glycemic targets to reduce your risk of future hypoglycemia.

See also: Duel with hypoglycemia: medical second

Consequences of hypoglycemia

In addition to the fear of recurrence and the impact on human behavior, each episode of hypoglycemia carries immediate risks to health and life.

Daily and long-term risks

Over time, the brain adapts to repeated hypoglycemia and symptoms begin to appear at lower blood glucose levels than at the beginning. This leads to an increased risk of unrecognized, latent hypoglycemia. In turn, latent hypoglycemia increases the risk of severe hypoglycemia, which will require the assistance of others for the active introduction of carbohydrates or glucagon or other resuscitation.

Risk of developing serious complications

Severe hypoglycemia is extremely dangerous and can lead to:

- loss of consciousness and injury to a person

- development of seizures, hypoglycemic coma

- impairment of memory and learning ability

- development of depression

- events: myocardial infarction, arrhythmias

Hypoglycemia while driving

If you begin to show signs of hypoglycemia while driving, you should immediately stop in a safe place for at least 60 minutes. During this time, check blood sugar levels and take action for hypoglycemia: take fast carbohydrates and ensure enough slower complex carbohydrates to avoid hypoglycemia for the rest of the trip.

Do not drive for at least 45 minutes after your blood sugar level has risen to 5 mmol/l and you feel better. After an episode of hypoglycemia, your reaction may be worse for up to 45 minutes, so you need to give your body enough time to recover. 15

15

When traveling long distances, stop at least every 1-2 hours and check your blood sugar. Cars should always have lollipops, sugar, sugary drinks or juice, a glucometer, and food in the car.

Hypoglycemia and driving – well-known dia-blogger, head of the Nikolaev-Odessa Diabetes Association Marina Yankov shares her experience

Prevention of hypoglycemia

blood. The diagnosis of "hypoglycemia" is a frequent consequence of relevant patterns that you can track yourself.

To do this, analyze a number of questions:

- Is there a tendency for blood sugar levels to drop at the same time of day?

- Do you have problems with glycemia (blood sugar) during certain activities?

- Do stress and illness trigger your hypoglycaemia?

- Does your blood glucose level depend on whether you are warm or cold?

And draw your own conclusions:

- If the daily routine is the cause of glycemic fluctuations, you can correct it yourself, for example, change the hours of eating.

Learn more