Divorce rates in 1950s

The Divorce Rate Over the Last 150 Years

The Divorce Rate Over the Last 150 Years Search iconA magnifying glass. It indicates, "Click to perform a search". Chevron iconIt indicates an expandable section or menu, or sometimes previous / next navigation options.HOMEPAGELifestyle

Save Article IconA bookmarkShare iconAn curved arrow pointing right.Download the app

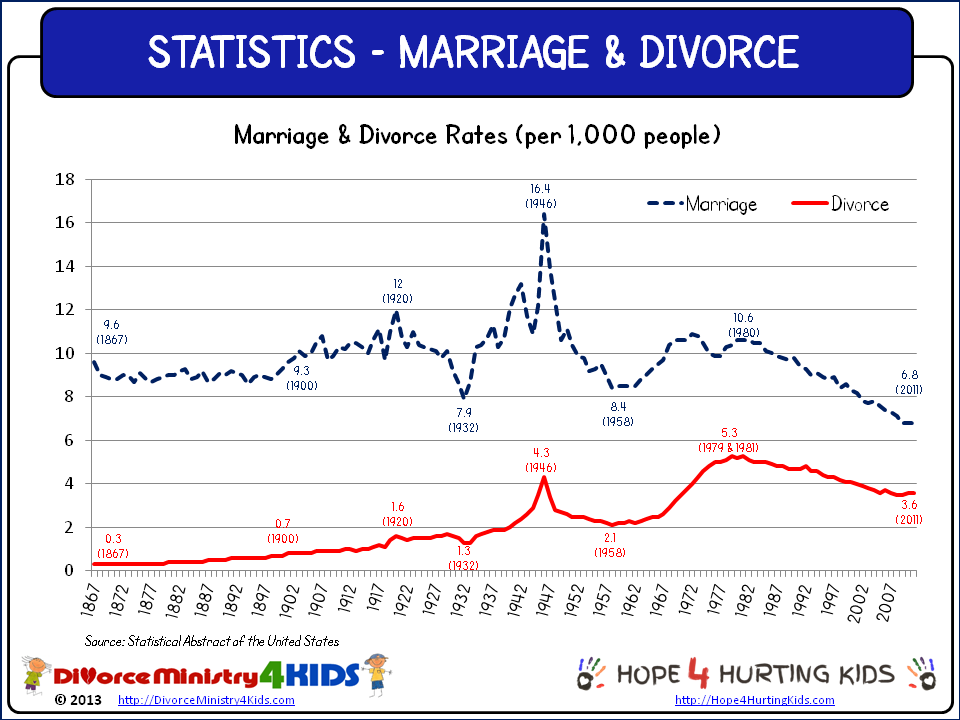

A couple in 1940. New York Public Library- The INSIDER data team examined divorce rates over the past 150 years and found some interesting trends.

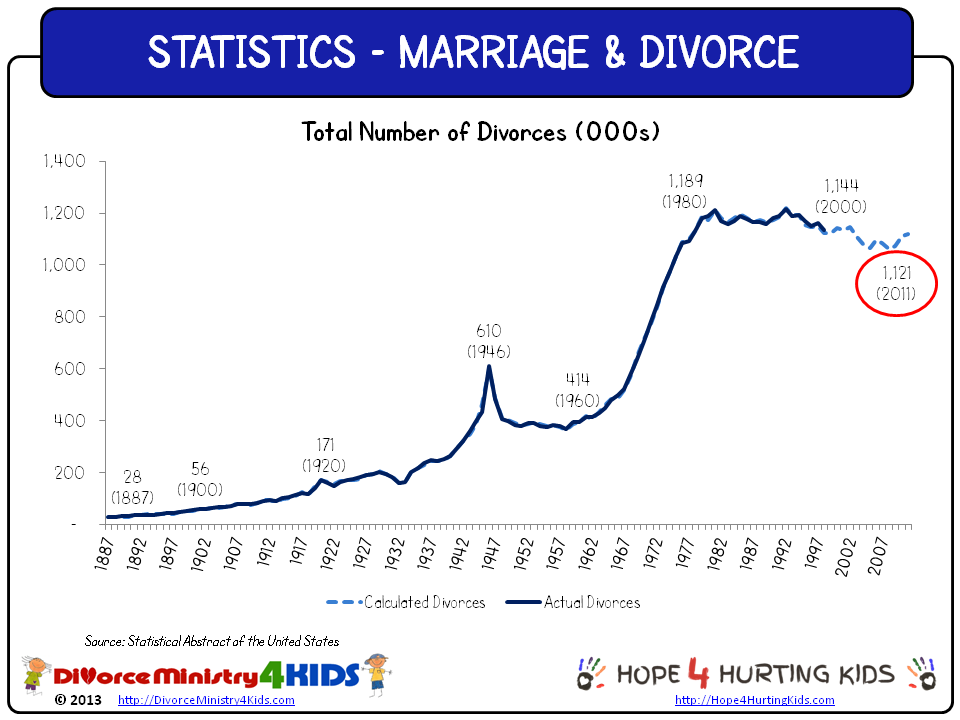

- Divorce rates steadily increased from the mid-1800s to the 1950s.

- The biggest increase in divorces was between the '60s and '70s.

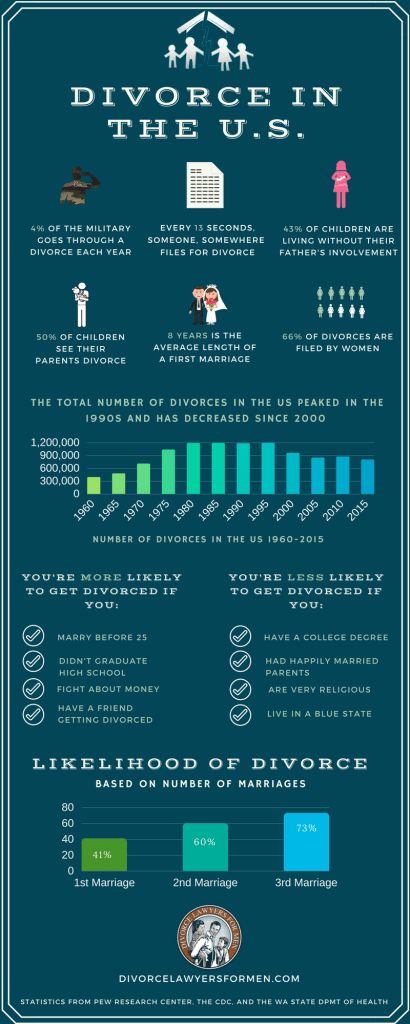

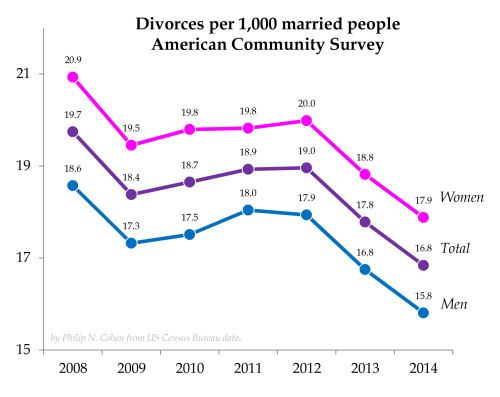

- Since the turn of the 21st century, divorce has been on the decline.

Thanks for signing up!

Access your favorite topics in a personalized feed while you're on the go.

LoadingSomething is loading.Thanks for signing up!

Access your favorite topics in a personalized feed while you're on the go.

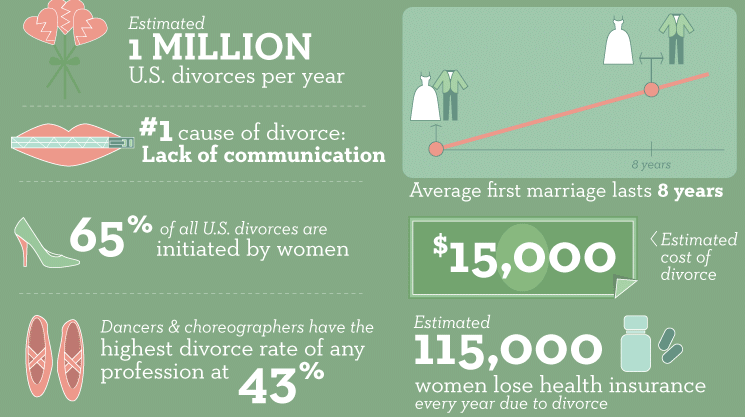

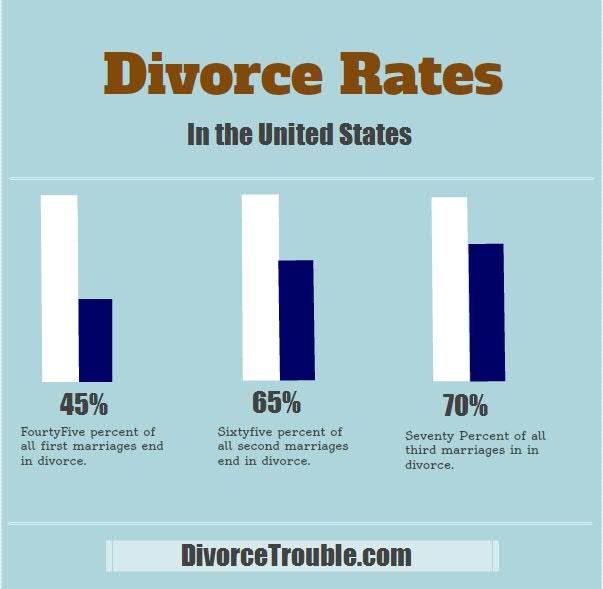

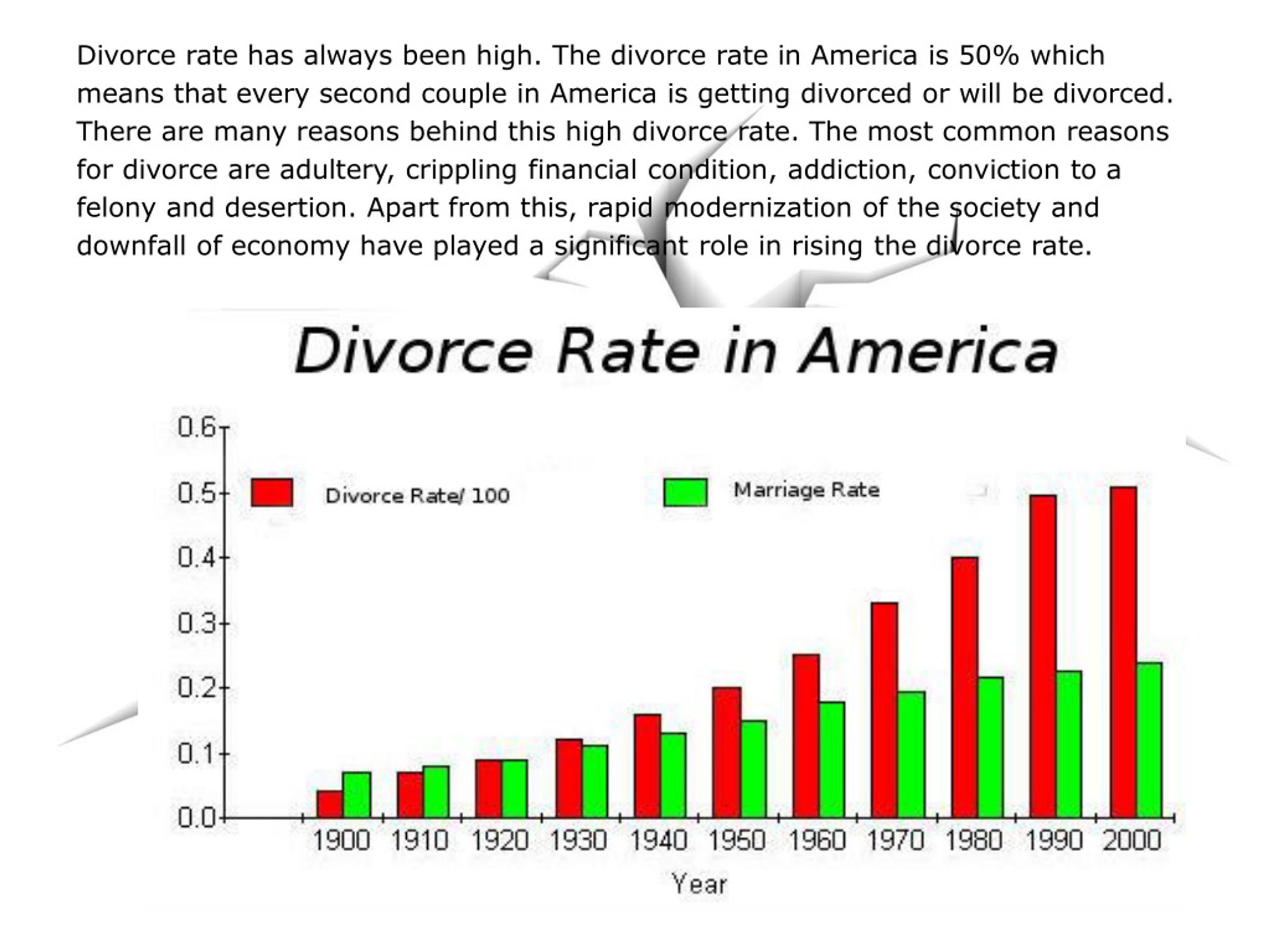

It's commonly believed that half of all marriages today end in divorce. It certainly feels that way, as headlines are filled with famous couples parting ways. But it hasn't always been this way. In fact, divorce was once taboo.

It certainly feels that way, as headlines are filled with famous couples parting ways. But it hasn't always been this way. In fact, divorce was once taboo.

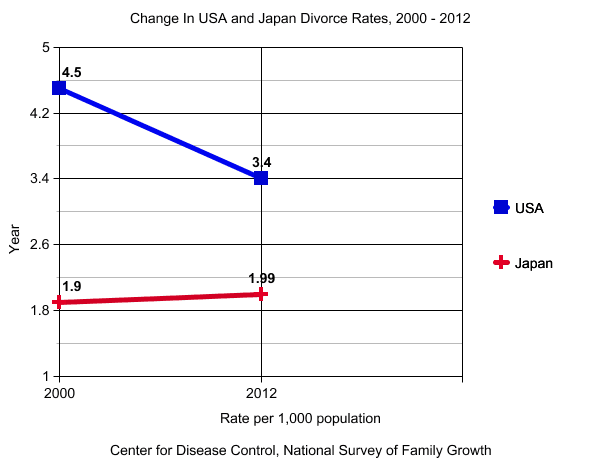

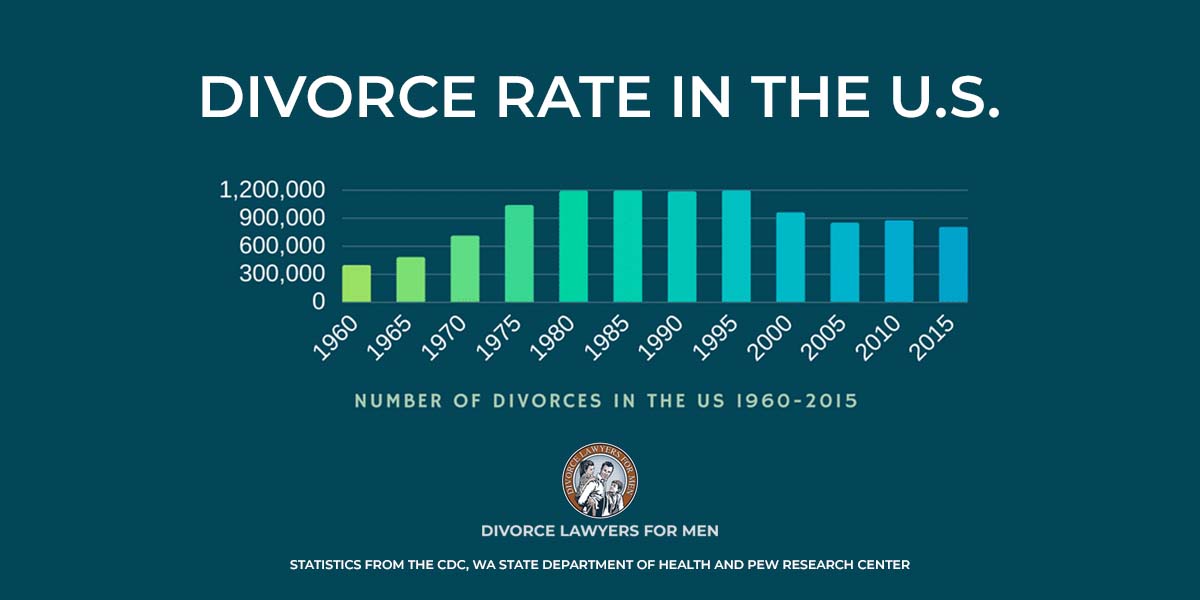

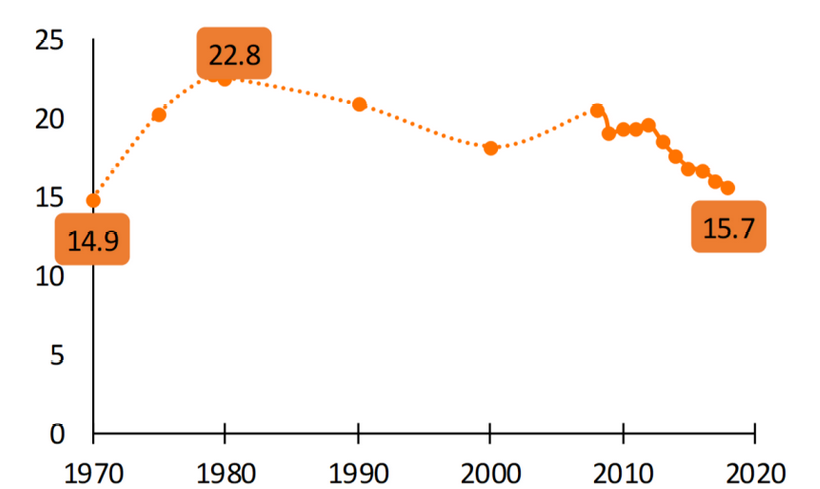

To see how divorce changed over time, the INSIDER data team compiled information within the US from the CDC and data scientist Randy Olson. Since we know the number of divorces every year, but the population changes, we calculated the rate of divorce for every 1,000 people. It became clear that half of all marriages don't end in divorce today. In fact, divorce is on the decline these days.

Keep reading to see more surprising trends the divorce rate has had throughout the years.

From 1867 to 1879, the annual divorce rate was 0.3 divorces per 1,000 Americans.

A couple in the 1800s. Library of Congress

Library of Congress In the 19th and early 20th centuries, people often married to gain property rights or to move social class. All of that changed by the mid- to late 1800s, with the ideas of love and romance becoming the main reason to wed.

But that doesn't mean everyone stayed married. In 1867, there were 10,000 divorces, and by 1879, there were 17,000 that year. However, the rate of divorce stayed at a very low 0.3 divorces per 1,000 Americans.

The rest of the century, the annual rate steadily increased to 0.7 divorces for every 1,000 people.

A couple in 1900. AP

AP In the 19th century, divorce was rare, and generally considered taboo. Unhappy couples would often separate but not legally get divorced.

But there were a few pioneers who did legally part ways. In fact, in 1880, the rate rose to 0.4 for every 1,000 Americans with 20,000 divorces, and it increased again in 1887 to 0.5. The rate didn't hit 0.7 until 1898 with 48,000 divorces that year.

At the turn of the century, the annual divorce rate rose to 0.9 divorces for every 1,000 people in a given year.

A bride in 1905. New York public Library

New York public Library At the start of the 20th century, divorce was still considered taboo and a foreign concept. In 1901, the rate rose from 0.7 for every 1,000 people to 0.8 with 61,000 divorces that year. It increased again in 1907 to 0.9, and stayed there for the rest of the decade.

As the country entered World War I in the 1910s, each year there was still only 1 divorce for every 1,000 Americans.

Woman working in 1919. New York Public Library

New York Public Library As men went off to fight in World War I, many women entered the workforce, earning more independence and freedom. As they started to create an identity for themselves, some realized they didn't need a man to depend on for security. Although that percentage is quite small, there are a few who got divorced.

In 1912, the rate of divorce reached 1 divorce for every 1,000 people, and hit 1.4 in 1919 with 142,000 divorces.

During the Roaring '20s, the divorce rate climbed up to 1.7 divorces for every 1,000 Americans.

Couple in 1920s. AP Images

Couple in 1920s. AP Images During the '20s, women continued to gain their independence, as they embraced the life of a flapper and started dating publicly. Challenging traditional gender roles, many women chose to stay single longer, instead of getting married young. The number of divorces increased to 1.7 per 1,000 people in 1928 and 1929 with 200,000 divorces.

At the start of the 1930s, the yearly divorce rate briefly dipped, but then climbed again to 1.9 divorces for every 1,000 people.

A wedding in 1932. New York Public LibraryWhen the Great Depression hit in the early '30s, a poor labor market meant that many women had to rely on men again for money. During this time, the divorce rate slipped from 1.6 per 1,000 people in 1930 to 1.3 in 1933. "Love in the Time of the Depression: The Effect of Economic Conditions on Marriage in the Great Depression" postulates that "Marriages formed during tough economic times were more likely to survive compared to matches made in more prosperous time periods."

During this time, the divorce rate slipped from 1.6 per 1,000 people in 1930 to 1.3 in 1933. "Love in the Time of the Depression: The Effect of Economic Conditions on Marriage in the Great Depression" postulates that "Marriages formed during tough economic times were more likely to survive compared to matches made in more prosperous time periods."

By the second half of the decade, the rate started to climb again, reaching 1.9 in 1939 with 251,000 divorces.

In the '40s, the annual divorce rate reached 3.4 divorces for every 1,000 Americans.

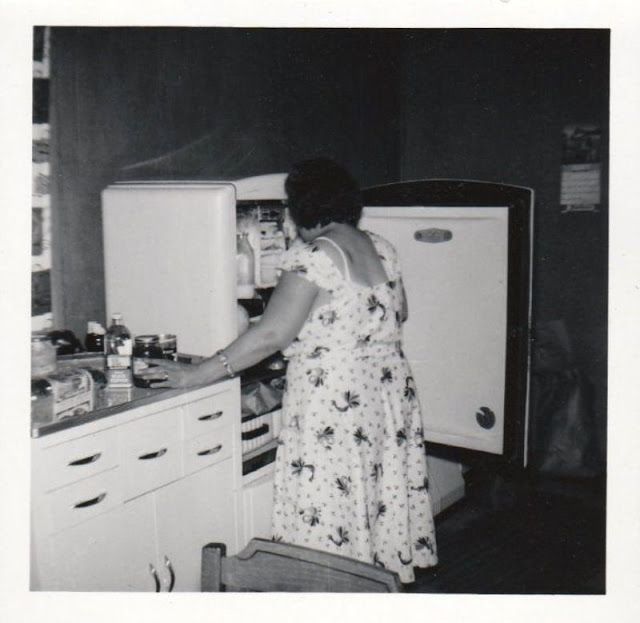

Couple in 1940. New York Public LibraryLike during World War I, women entered the workforce again when the US joined World War II. They once again earned more independence and freedom, leading to a higher divorce rate in the country.

They once again earned more independence and freedom, leading to a higher divorce rate in the country.

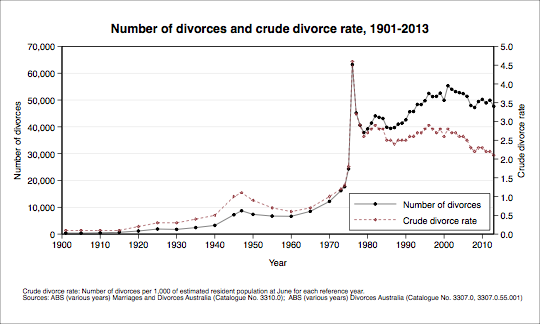

In 1940, the rate was two divorces per 1,000 people, but reached 3.4 in 1947. The rate dipped over the next few years, ending the decade with a 2.7 per 1,000 rate and 397,000 divorces.

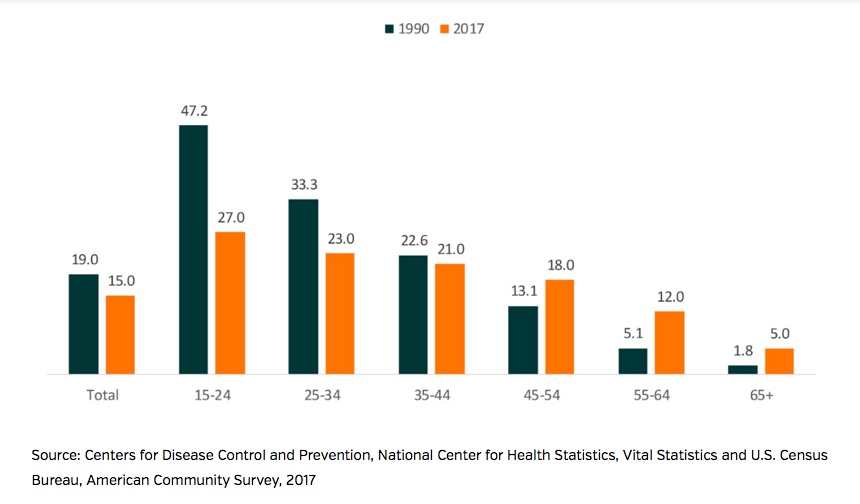

The divorce rate decreased in the '50s as American ideals changed.

A family roasting a turkey. Retrofile RF/GettyThe idea of the nuclear, All-American Family was created in the 1950s, and put an emphasis on the family unit and marriage. This time period saw younger marriages, more kids, and fewer divorces.

This time period saw younger marriages, more kids, and fewer divorces.

In fact, the divorce rate was 2.5 divorces for every 1,000 people in 1950, and dropped to 2.3 in 1955. In 1958, the rate even slumped to 2.1, with 368,000 divorces.

In the '60s, the rate slowly started to climb again, ending the decade with a new high: 3.2 annual divorces for every 1,000 Americans.

Couple in the 1960s. New York Public LibraryAlmost as a defiance to the ideals of the '50s, the next decade changed everything. During the 1960s, women started to close the education gap and the country started to embrace more progressive politics. As a result, women sought independence, causing the divorce rate to rise significantly.

During the 1960s, women started to close the education gap and the country started to embrace more progressive politics. As a result, women sought independence, causing the divorce rate to rise significantly.

In 1960, the rate was 2.2 per 1,000 Americans, and reached 2.5 in 1965. By 1969, the rate jumped to 3.2 with 639,000 divorces.

In 1970s, the annual rate was 3.5 per 1,000, but by the end of the decade, it reached 5.1 divorces per 1,000 Americans.

Hippies in the 1970s. APThe 1970s were categorized by hippies and free love. As an emphasis was put on group love and an absence of legal ties instead of coupling and marriage, divorce rates rose dramatically throughout the decade. This was the defining decade for divorce as the numbers reached an all-time high.

As an emphasis was put on group love and an absence of legal ties instead of coupling and marriage, divorce rates rose dramatically throughout the decade. This was the defining decade for divorce as the numbers reached an all-time high.

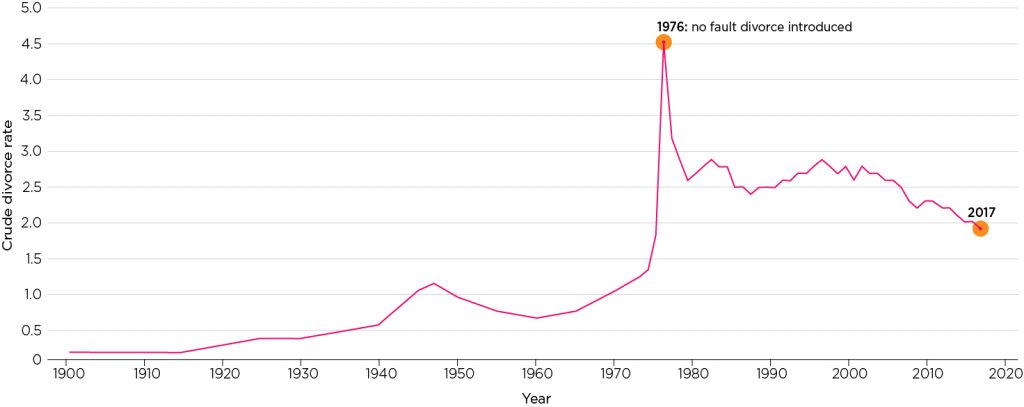

In 1970, the rate was 3.5, and by 1972 it had jumped to 4 divorces for every 1,000 Americans. In 1976, it jumped to 5, and by 1979, the rate was 5.3 per 1,000 American, with 1,193,062 divorces that year.

The divorce boom started to slow down and decline in the '80s.

Madonna and Sean Penn divorced in the '80s. John Barrett/APAfter an all-time high in the '70s, divorces in the 1980s seemed to slow down. In 1980, the rate was 5.2 divorces per 1,000 people, and by 1989, it had dropped to 4.7.

In 1980, the rate was 5.2 divorces per 1,000 people, and by 1989, it had dropped to 4.7.

The divorce rate remained steady at 4 divorces for every 1,000 Americans in the '90s, but slowly declined throughout the decade.

Prince Charles and Princess Diana divorced in the '90s. ASSOCIATED PRESSAlthough no data was recorded for 1995 and 1996, it's apparent that the divorce rate continued to decline throughout the decade — even if it hovered around 4 for every 1,000 people. In 1990, the rate was 4.7 and dropped to 4.3 in 1997. By 1999, the rate reached 4.1 divorces for every 1,000 Americans with 1,145,245 divorces that year.

In 1990, the rate was 4.7 and dropped to 4.3 in 1997. By 1999, the rate reached 4.1 divorces for every 1,000 Americans with 1,145,245 divorces that year.

Since the turn of the 21st-century, the divorce rate continues to decline rapidly.

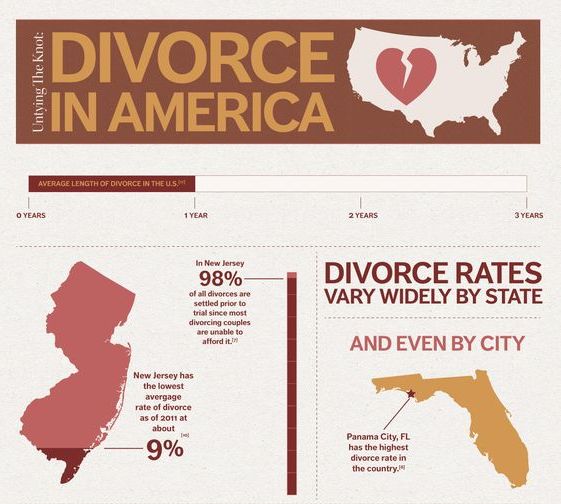

Heidi Klum and Seal split in 2014. Jason Merritt/Getty ImagesSince 2000, California, Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, and Minnesota have stopped reporting divorce rates, but it's still clear that the number of divorces is declining all over the US. By 2010, the rate of divorces dropped to 3.6 for every 1,000 people, and in 2017 the rate reached 2.9 with only 787,251 divorces — the lowest it's been since 1968.

By 2010, the rate of divorces dropped to 3.6 for every 1,000 people, and in 2017 the rate reached 2.9 with only 787,251 divorces — the lowest it's been since 1968.

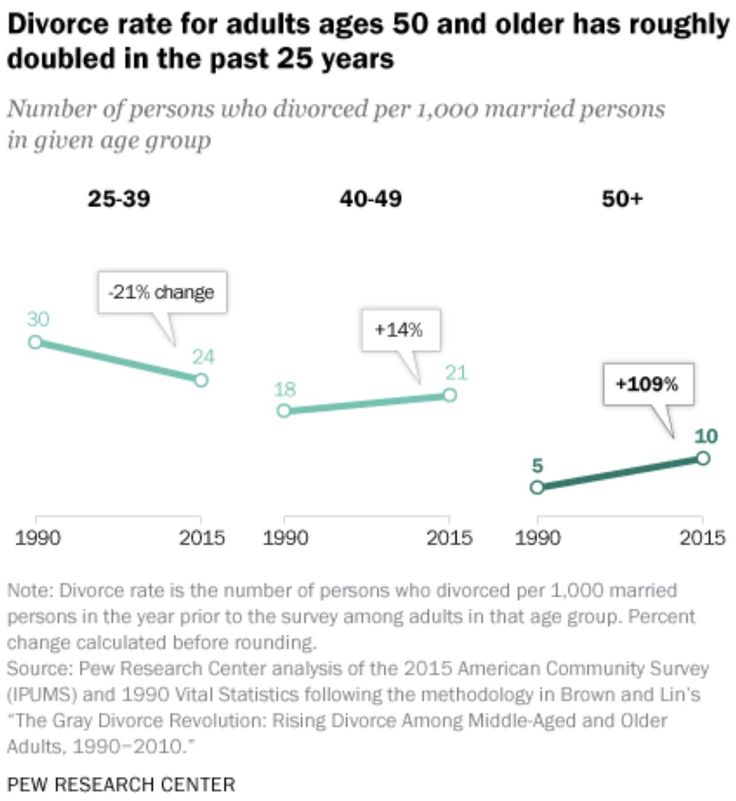

TIME reports that older generations continue to get divorced, but the decline is due to the smaller amount of millennials getting married. Since the younger generation is getting married later in life and approaching marriage differently, the divorce rates have similarly declined.

Visit INSIDER's homepage for more.

- Read more:

- 18 times celebrities got real about their divorces

- 4 reasons why you should never feel ashamed of your divorce

- The common statistic that 'half of marriages end in divorce' is bogus

- I got a divorce but am still with my ex husband — here's how we made it work

Read next

Lifestyle Divorce RelationshipMore. ..

..

The Evolution of Divorce | National Affairs

W. Bradford Wilcox Fall 2009

In 1969, Governor Ronald Reagan of California made what he later admitted was one of the biggest mistakes of his political life. Seeking to eliminate the strife and deception often associated with the legal regime of fault-based divorce, Reagan signed the nation's first no-fault divorce bill. The new law eliminated the need for couples to fabricate spousal wrongdoing in pursuit of a divorce; indeed, one likely reason for Reagan's decision to sign the bill was that his first wife, Jane Wyman, had unfairly accused him of "mental cruelty" to obtain a divorce in 1948. But no-fault divorce also gutted marriage of its legal power to bind husband and wife, allowing one spouse to dissolve a marriage for any reason — or for no reason at all.

But no-fault divorce also gutted marriage of its legal power to bind husband and wife, allowing one spouse to dissolve a marriage for any reason — or for no reason at all.

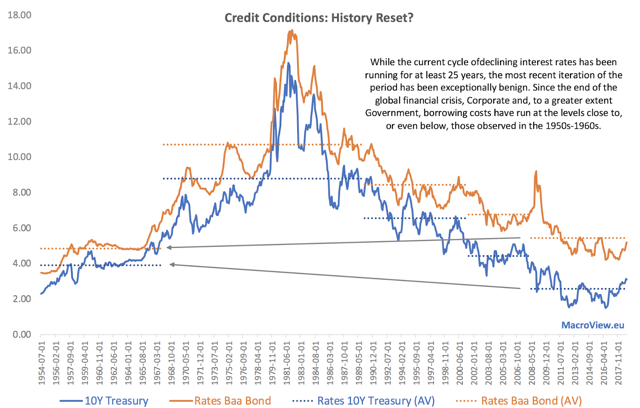

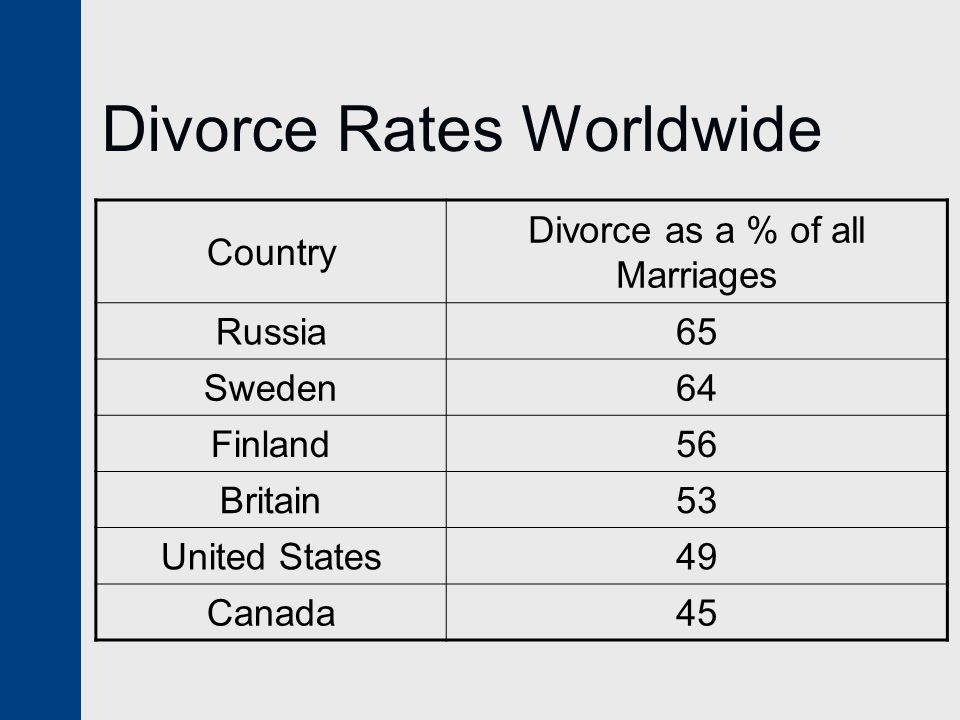

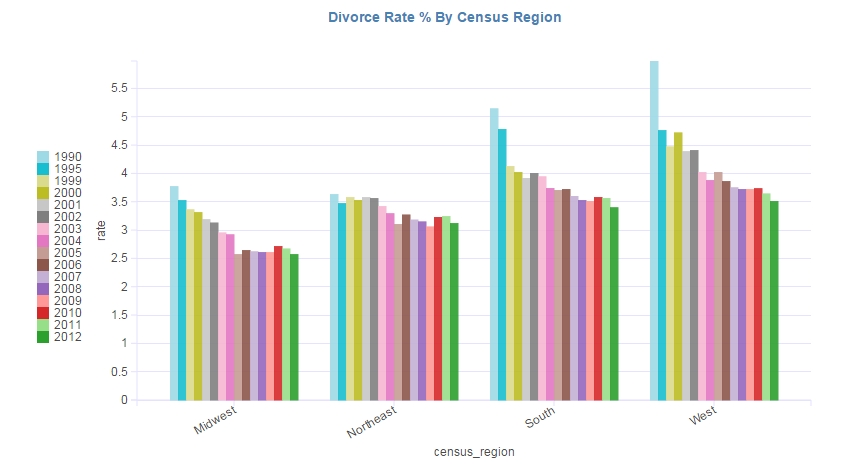

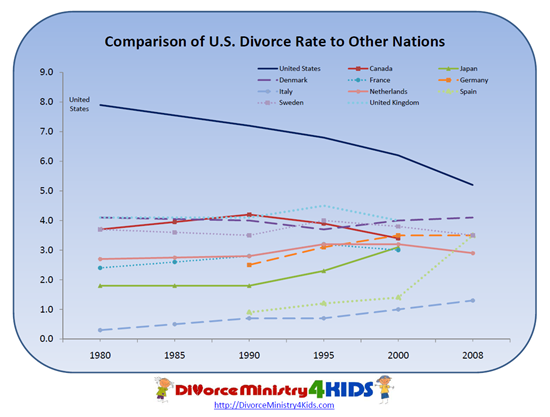

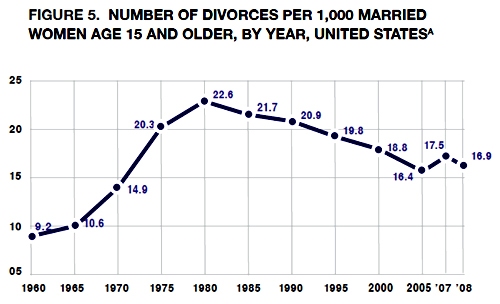

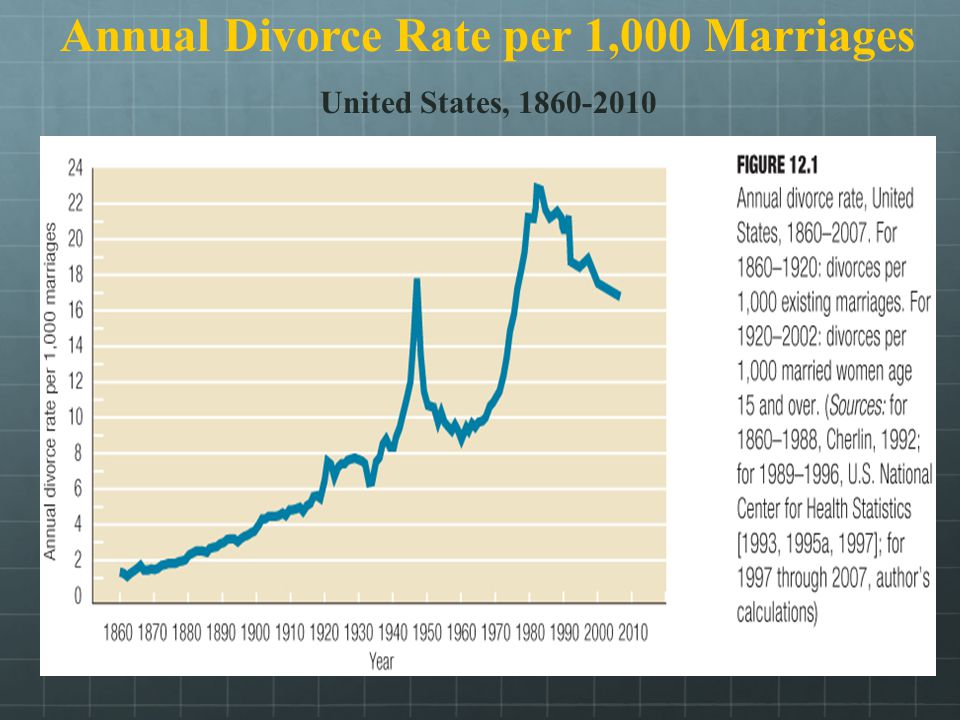

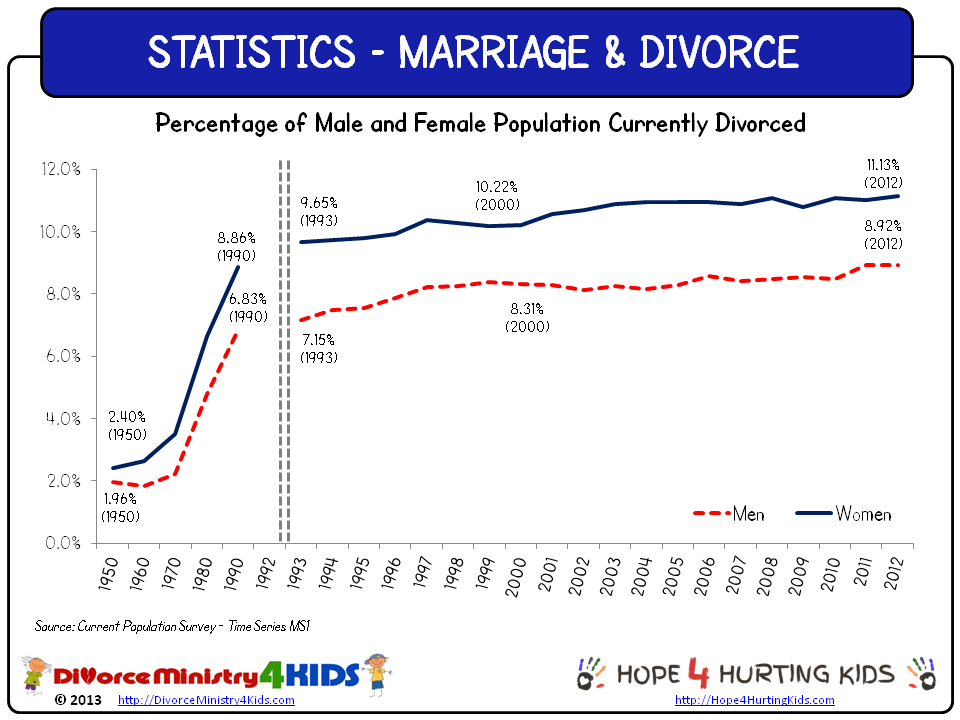

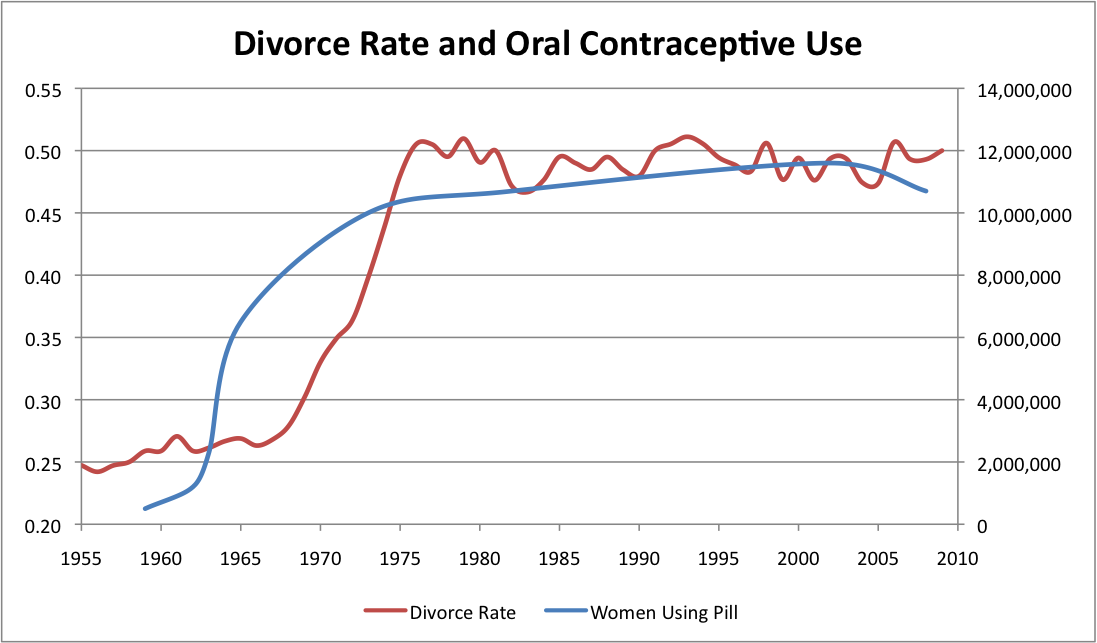

In the decade and a half that followed, virtually every state in the Union followed California's lead and enacted a no-fault divorce law of its own. This legal transformation was only one of the more visible signs of the divorce revolution then sweeping the United States: From 1960 to 1980, the divorce rate more than doubled — from 9.2 divorces per 1,000 married women to 22.6 divorces per 1,000 married women. This meant that while less than 20% of couples who married in 1950 ended up divorced, about 50% of couples who married in 1970 did. And approximately half of the children born to married parents in the 1970s saw their parents part, compared to only about 11% of those born in the 1950s.

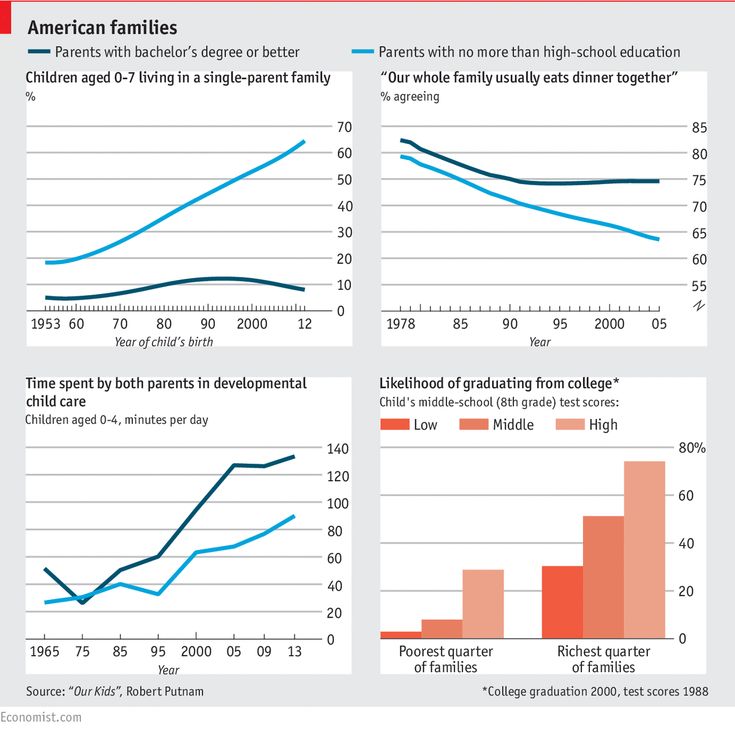

In the years since 1980, however, these trends have not continued on straight upward paths, and the story of divorce has grown increasingly complicated. In the case of divorce, as in so many others, the worst consequences of the social revolution of the 1960s and '70s are now felt disproportionately by the poor and less educated, while the wealthy elites who set off these transformations in the first place have managed to reclaim somewhat healthier and more stable habits of married life. This imbalance leaves our cultural and political elites less well attuned to the magnitude of social dysfunction in much of American society, and leaves the most vulnerable Americans — especially children living in poor and working-class communities — even worse off than they would otherwise be.

In the case of divorce, as in so many others, the worst consequences of the social revolution of the 1960s and '70s are now felt disproportionately by the poor and less educated, while the wealthy elites who set off these transformations in the first place have managed to reclaim somewhat healthier and more stable habits of married life. This imbalance leaves our cultural and political elites less well attuned to the magnitude of social dysfunction in much of American society, and leaves the most vulnerable Americans — especially children living in poor and working-class communities — even worse off than they would otherwise be.

THE RISE OF DIVORCE

The divorce revolution of the 1960s and '70s was over-determined. The nearly universal introduction of no-fault divorce helped to open the floodgates, especially because these laws facilitated unilateral divorce and lent moral legitimacy to the dissolution of marriages. The sexual revolution, too, fueled the marital tumult of the times: Spouses found it easier in the Swinging Seventies to find extramarital partners, and came to have higher, and often unrealistic, expectations of their marital relationships. Increases in women's employment as well as feminist consciousness-raising also did their part to drive up the divorce rate, as wives felt freer in the late '60s and '70s to leave marriages that were abusive or that they found unsatisfying.

Increases in women's employment as well as feminist consciousness-raising also did their part to drive up the divorce rate, as wives felt freer in the late '60s and '70s to leave marriages that were abusive or that they found unsatisfying.

The anti-institutional tenor of the age also meant that churches lost much of their moral authority to reinforce the marital vow. It didn't help that many mainline Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish leaders were caught up in the zeitgeist, and lent explicit or implicit support to the divorce revolution sweeping across American society. This accomodationist mentality was evident in a 1976 pronouncement issued by the United Methodist Church, the largest mainline Protestant denomination in America. The statement read in part:

In marriages where the partners are, even after thoughtful reconsideration and counsel, estranged beyond reconciliation, we recognize divorce and the right of divorced persons to remarry, and express our concern for the needs of the children of such unions.

To this end we encourage an active, accepting, and enabling commitment of the Church and our society to minister to the needs of divorced persons.

Most important, the psychological revolution of the late '60s and '70s, which was itself fueled by a post-war prosperity that allowed people to give greater attention to non-material concerns, played a key role in reconfiguring men and women's views of marriage and family life. Prior to the late 1960s, Americans were more likely to look at marriage and family through the prisms of duty, obligation, and sacrifice. A successful, happy home was one in which intimacy was an important good, but by no means the only one in view. A decent job, a well-maintained home, mutual spousal aid, child-rearing, and shared religious faith were seen almost universally as the goods that marriage and family life were intended to advance.

But the psychological revolution's focus on individual fulfillment and personal growth changed all that. Increasingly, marriage was seen as a vehicle for a self-oriented ethic of romance, intimacy, and fulfillment. In this new psychological approach to married life, one's primary obligation was not to one's family but to one's self; hence, marital success was defined not by successfully meeting obligations to one's spouse and children but by a strong sense of subjective happiness in marriage — usually to be found in and through an intense, emotional relationship with one's spouse. The 1970s marked the period when, for many Americans, a more institutional model of marriage gave way to the "soul-mate model" of marriage.

Increasingly, marriage was seen as a vehicle for a self-oriented ethic of romance, intimacy, and fulfillment. In this new psychological approach to married life, one's primary obligation was not to one's family but to one's self; hence, marital success was defined not by successfully meeting obligations to one's spouse and children but by a strong sense of subjective happiness in marriage — usually to be found in and through an intense, emotional relationship with one's spouse. The 1970s marked the period when, for many Americans, a more institutional model of marriage gave way to the "soul-mate model" of marriage.

Of course, the soul-mate model was much more likely to lead couples to divorce court than was the earlier institutional model of marriage. Now, those who felt they were in unfulfilling marriages also felt obligated to divorce in order to honor the newly widespread ethic of expressive individualism. As social historian Barbara Dafoe Whitehead has observed of this period, "divorce was not only an individual right but also a psychological resource. The dissolution of marriage offered the chance to make oneself over from the inside out, to refurbish and express the inner self, and to acquire certain valuable psychological assets and competencies, such as initiative, assertiveness, and a stronger and better self-image."

The dissolution of marriage offered the chance to make oneself over from the inside out, to refurbish and express the inner self, and to acquire certain valuable psychological assets and competencies, such as initiative, assertiveness, and a stronger and better self-image."

But what about the children? In the older, institutional model of marriage, parents were supposed to stick together for their sake. The view was that divorce could leave an indelible emotional scar on children, and would also harm their social and economic future. Yet under the new soul-mate model of marriage, divorce could be an opportunity for growth not only for adults but also for their offspring. The view was that divorce could protect the emotional welfare of children by allowing their parents to leave marriages in which they felt unhappy. In 1962, as Whitehead points out in her book The Divorce Culture, about half of American women agreed with the idea that "when there are children in the family parents should stay together even if they don't get along. " By 1977, only 20% of American women held this view.

" By 1977, only 20% of American women held this view.

At the height of the divorce revolution in the 1970s, many scholars, therapists, and journalists served as enablers of this kind of thinking. These elites argued that children were resilient in the face of divorce; that children could easily find male role models to replace absent fathers; and that children would be happier if their parents were able to leave unhappy marriages. In 1979, one prominent scholar wrote in the Journal of Divorce that divorce even held "growth potential" for mothers, as they could enjoy "increased personal autonomy, a new sense of competence and control, [and the] development of better relationships with [their] children." And in 1974's The Courage to Divorce, social workers Susan Gettleman and Janet Markowitz argued that boys need not be harmed by the absence of their fathers: "When fathers are not available, friends, relatives, teachers and counselors can provide ample opportunity for youngsters to model themselves after a like-sexed adult. "

"

Thus, by the time the 1970s came to a close, many Americans — rich and poor alike — had jettisoned the institutional model of married life that prioritized the welfare of children, and which sought to discourage divorce in all but the most dire of circumstances. Instead, they embraced the soul-mate model of married life, which prioritized the emotional welfare of adults and gave moral permission to divorce for virtually any reason.

THE MORNING AFTER

Thirty years later, the myth of the good divorce has not stood up well in the face of sustained social scientific inquiry — especially when one considers the welfare of children exposed to their parents' divorces.

Since 1974, about 1 million children per year have seen their parents divorce — and children who are exposed to divorce are two to three times more likely than their peers in intact marriages to suffer from serious social or psychological pathologies. In their book Growing Up with a Single Parent: What Hurts, What Helps, sociologists Sara McLanahan and Gary Sandefur found that 31% of adolescents with divorced parents dropped out of high school, compared to 13% of children from intact families. They also concluded that 33% of adolescent girls whose parents divorced became teen mothers, compared to 11% of girls from continuously married families. And McLanahan and her colleagues have found that 11% of boys who come from divorced families end up spending time in prison before the age of 32, compared to 5% of boys who come from intact homes.

They also concluded that 33% of adolescent girls whose parents divorced became teen mothers, compared to 11% of girls from continuously married families. And McLanahan and her colleagues have found that 11% of boys who come from divorced families end up spending time in prison before the age of 32, compared to 5% of boys who come from intact homes.

Research also indicates that remarriage is no salve for children wounded by divorce. Indeed, as sociologist Andrew Cherlin notes in his important new book, The Marriage-Go-Round, "children whose parents have remarried do not have higher levels of well-being than children in lone-parent families." The reason? Often, the establishment of a step-family results in yet another move for a child, requiring adjustment to a new caretaker and new step-siblings — all of which can be difficult for children, who tend to thrive on stability.

The divorce revolution's collective consequences for children are striking. Taking into account both divorce and non-marital childbearing, sociologist Paul Amato estimates that if the United States enjoyed the same level of family stability today as it did in 1960, the nation would have 750,000 fewer children repeating grades, 1. 2 million fewer school suspensions, approximately 500,000 fewer acts of teenage delinquency, about 600,000 fewer kids receiving therapy, and approximately 70,000 fewer suicide attempts every year (correction appended). As Amato concludes, turning back the family-stability clock just a few decades could significantly improve the lives of many children.

2 million fewer school suspensions, approximately 500,000 fewer acts of teenage delinquency, about 600,000 fewer kids receiving therapy, and approximately 70,000 fewer suicide attempts every year (correction appended). As Amato concludes, turning back the family-stability clock just a few decades could significantly improve the lives of many children.

Skeptics confronted with this kind of research often argue that it is unfair to compare children of divorce to children from intact, married households. They contend that it is the conflict that precedes the divorce, rather than the divorce itself, that is likely to be particularly traumatic for children. Amato's work suggests that the skeptics have a point: In cases where children are exposed to high levels of conflict — like domestic violence or screaming matches between parents — they do seem to do better if their parents part.

But more than two-thirds of all parental divorces do not involve such highly conflicted marriages. And "unfortunately, these are the very divorces that are most likely to be stressful for children," as Amato and Alan Booth, his colleague at Penn State University, point out. When children see their parents divorce because they have simply drifted apart — or because one or both parents have become unhappy or left to pursue another partner — the kids' faith in love, commitment, and marriage is often shattered. In the wake of their parents' divorce, children are also likely to experience a family move, marked declines in their family income, a stressed-out single mother, and substantial periods of paternal absence — all factors that put them at risk. In other words, the clear majority of divorces involving children in America are not in the best interests of the children.

And "unfortunately, these are the very divorces that are most likely to be stressful for children," as Amato and Alan Booth, his colleague at Penn State University, point out. When children see their parents divorce because they have simply drifted apart — or because one or both parents have become unhappy or left to pursue another partner — the kids' faith in love, commitment, and marriage is often shattered. In the wake of their parents' divorce, children are also likely to experience a family move, marked declines in their family income, a stressed-out single mother, and substantial periods of paternal absence — all factors that put them at risk. In other words, the clear majority of divorces involving children in America are not in the best interests of the children.

Not surprisingly, the effects of divorce on adults are more ambiguous. From an emotional and social perspective, about 20% of divorced adults find their lives enhanced and another 50% seem to suffer no long-term ill effects, according to research by psychologist Mavis Hetherington. Adults who initiated a divorce are especially likely to report that they are flourishing afterward, or are at least doing just fine.

Adults who initiated a divorce are especially likely to report that they are flourishing afterward, or are at least doing just fine.

Spouses who were unwilling parties to a unilateral divorce, however, tend to do less well. And the ill effects of divorce for adults tend to fall disproportionately on the shoulders of fathers. Since approximately two-thirds of divorces are legally initiated by women, men are more likely than women to be divorced against their will. In many cases, these men have not engaged in egregious marital misconduct such as abuse, adultery, or substance abuse. They feel mistreated by their ex-wives and by state courts that no longer take into account marital "fault" when making determinations about child custody, child support, and the division of marital property. Yet in the wake of a divorce, these men will nevertheless often lose their homes, a substantial share of their monthly incomes, and regular contact with their children. For these men, and for women caught in similar circumstances, the sting of an unjust divorce can lead to downward emotional spirals, difficulties at work, and serious deteriorations in the quality of their relationships with their children.

Looking beyond the direct effects of divorce on adults and children, it is also important to note the ways in which widespread divorce has eroded the institution of marriage — particularly, its assault on the quality, prevalence, and stability of marriage in American life.

In the 1970s, proponents of easy divorce argued that the ready availability of divorce would boost the quality of married life, as abused, unfulfilled, or otherwise unhappy spouses were allowed to leave their marriages. Had they been correct, we would expect to see that Americans' reports of marital quality had improved during and after the 1970s. Instead, marital quality fell during the '70s and early '80s. In the early 1970s, 70% of married men and 67% of married women reported being very happy in their marriages; by the early '80s, these figures had fallen to 63% for men and 62% for women. So marital quality dropped even as divorce rates were reaching record highs.

What happened? It appears that average marriages suffered during this time, as widespread divorce undermined ordinary couples' faith in marital permanency and their ability to invest financially and emotionally in their marriages — ultimately casting clouds of doubt over their relationships. For instance, one study by economist Betsey Stevenson found that investments in marital partnerships declined in the wake of no-fault divorce laws. Specifically, she found that newlywed couples in states that passed no-fault divorce were about 10% less likely to support a spouse through college or graduate school and were 6% less likely to have a child together. Ironically, then, the widespread availability of easy divorce not only enabled "bad" marriages to be weeded out, but also made it more difficult for "good" marriages to take root and flourish.

For instance, one study by economist Betsey Stevenson found that investments in marital partnerships declined in the wake of no-fault divorce laws. Specifically, she found that newlywed couples in states that passed no-fault divorce were about 10% less likely to support a spouse through college or graduate school and were 6% less likely to have a child together. Ironically, then, the widespread availability of easy divorce not only enabled "bad" marriages to be weeded out, but also made it more difficult for "good" marriages to take root and flourish.

Second, marriage rates have fallen and cohabitation rates have surged in the wake of the divorce revolution, as men and women's faith in marriage has been shaken. From 1960 to 2007, the percentage of American women who were married fell from 66% to 51%, and the percentage of men who were married fell from 69% to 55%. Yet at the same time, the number of cohabiting couples increased fourteen-fold — from 439,000 to more than 6.4 million. Because of these increases in cohabitation, about 40% of American children will spend some time in a cohabiting union; 20% of babies are now born to cohabiting couples. And because cohabiting unions are much less stable than marriages, the vast majority of the children born to cohabiting couples will see their parents break up by the time they turn 15.

Because of these increases in cohabitation, about 40% of American children will spend some time in a cohabiting union; 20% of babies are now born to cohabiting couples. And because cohabiting unions are much less stable than marriages, the vast majority of the children born to cohabiting couples will see their parents break up by the time they turn 15.

A recent Bowling Green State University study of the motives for cohabitation found that young men and women who choose to cohabit are seeking alternatives to marriage and ways of testing a relationship to see if it might be safely transformed into a marriage — with both rationales clearly shaped by a fear of divorce. One young man told the researchers that living together allows you to "get to know the person and their habits before you get married. So that way, you won't have to get divorced." Another said that an advantage of cohabitation is that you "don't have to go through the divorce process if you do want to break up, you don't have to pay lawyers and have to deal with splitting everything and all that jazz. "

"

My own research confirms the connection between divorce and cohabitation in America. Specifically, data from the General Social Survey indicate that adult children of divorce are 61% more likely than adult children from married families to endorse the notion that it is a "good idea for a couple who intend to get married to live together first." Likewise, adult children of divorce are 47% more likely to be currently cohabiting, compared to those who were raised in intact, married families. Thus divorce has played a key role in reducing marriage and increasing cohabitation, which now exists as a viable competitor to marriage in the organization of sex, intimacy, childbearing, and even child-rearing.

Third, the divorce revolution has contributed to an intergenerational cycle of divorce. Work by demographer Nicholas Wolfinger indicates that the adult children of divorce are now 89% more likely to divorce themselves, compared to adults who were raised in intact, married families. Children of divorce who marry other children of divorce are especially likely to end up divorced, according to Wolfinger's work. Of course, the reason children of divorce — especially children of low-conflict divorce — are more likely to end their marriages is precisely that they have often learned all the wrong lessons about trust, commitment, mutual sacrifice, and fidelity from their parents.

Children of divorce who marry other children of divorce are especially likely to end up divorced, according to Wolfinger's work. Of course, the reason children of divorce — especially children of low-conflict divorce — are more likely to end their marriages is precisely that they have often learned all the wrong lessons about trust, commitment, mutual sacrifice, and fidelity from their parents.

THE DIVORCE DIVIDE

Clearly, the divorce revolution of the 1960s and '70s left a poisonous legacy. But what has happened since? Where do we stand today on the question of marriage and divorce? A survey of the landscape presents a decidedly mixed portrait of contemporary married life in America.

The good news is that, on the whole, divorce has declined since 1980 and marital happiness has largely stabilized. The divorce rate fell from a historic high of 22.6 divorces per 1,000 married women in 1980 to 17.5 in 2007. In real terms, this means that slightly more than 40% of contemporary first marriages are likely to end in divorce, down from approximately 50% in 1980. Perhaps even more important, recent declines in divorce suggest that a clear majority of children who are now born to married couples will grow up with their married mothers and fathers.

Perhaps even more important, recent declines in divorce suggest that a clear majority of children who are now born to married couples will grow up with their married mothers and fathers.

Similarly, the decline in marital happiness associated with the tidal wave of divorce in the 1960s and '70s essentially stopped more than two decades ago. Men's marital happiness hovered around 63% from the early 1980s to the mid-2000s, while women's marital happiness fell just a bit, from 62% in the early 1980s to 60% in the mid-2000s.

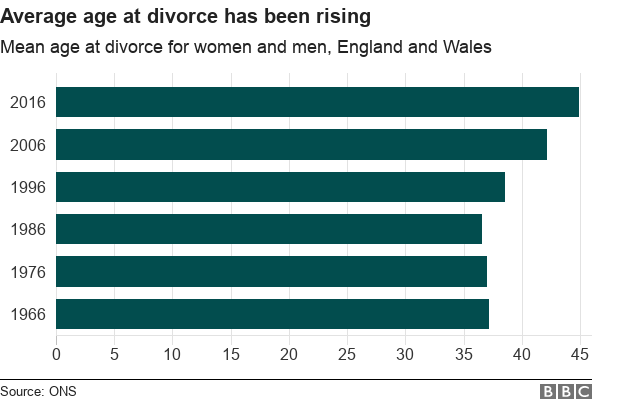

This good news can be explained largely by three key factors. First, the age at first marriage has risen. In 1970, the median age of marriage was 20.8 for women and 23.2 for men; in 2007, it was 25.6 for women and 27.5 for men. This means that fewer Americans are marrying when they are too immature to forge successful marriages. (It is true that some of the increase in age at first marriage is linked to cohabitation, but not the bulk of it.)

Second, the views of academic and professional experts about divorce and family breakdown have changed significantly in recent decades. Social-science data about the consequences of divorce have moved many scholars across the political spectrum to warn against continuing the divorce revolution, and to argue that intact families are essential, especially to the well-being of children. Here is a characteristic example, from a recent publication by a group of scholars at the Brookings Institution and Princeton University:

Social-science data about the consequences of divorce have moved many scholars across the political spectrum to warn against continuing the divorce revolution, and to argue that intact families are essential, especially to the well-being of children. Here is a characteristic example, from a recent publication by a group of scholars at the Brookings Institution and Princeton University:

Marriage provides benefits both to children and to society. Although it was once possible to believe that the nation's high rates of divorce, cohabitation, and nonmarital childbearing represented little more than lifestyle alternatives brought about by the freedom to pursue individual self-fulfillment, many analysts now believe that these individual choices can be damaging to the children who have no say in them and to the society that enables them.

Although certainly not all scholars, therapists, policymakers, and journalists would agree that contemporary levels of divorce and family breakdown are cause for worry, a much larger share of them expresses concern about the health of marriage in America — and about America's high level of divorce — than did so in the 1970s. These views seep into the popular consciousness and influence behavior — just as they did in the 1960s and '70s, when academic and professional experts carried the banner of the divorce revolution.

These views seep into the popular consciousness and influence behavior — just as they did in the 1960s and '70s, when academic and professional experts carried the banner of the divorce revolution.

A third reason for the stabilization in divorce rates and marital happiness is not so heartening. Put simply, marriage is increasingly the preserve of the highly educated and the middle and upper classes. Fewer working-class and poor Americans are marrying nowadays in part because marriage is seen increasingly as a sort of status symbol: a sign that a couple has arrived both emotionally and financially, or is at least within range of the American Dream. This means that those who do marry today are more likely to start out enjoying the money, education, job security, and social skills that increase the probability of long-term marital success.

And this is where the bad news comes in. When it comes to divorce and marriage, America is increasingly divided along class and educational lines. Even as divorce in general has declined since the 1970s, what sociologist Steven Martin calls a "divorce divide" has also been growing between those with college degrees and those without (a distinction that also often translates to differences in income). The figures are quite striking: College-educated Americans have seen their divorce rates drop by about 30% since the early 1980s, whereas Americans without college degrees have seen their divorce rates increase by about 6%. Just under a quarter of college-educated couples who married in the early 1970s divorced in their first ten years of marriage, compared to 34% of their less-educated peers. Twenty years later, only 17% of college-educated couples who married in the early 1990s divorced in their first ten years of marriage; 36% of less-educated couples who married in the early 1990s, however, divorced sometime in their first decade of marriage.

Even as divorce in general has declined since the 1970s, what sociologist Steven Martin calls a "divorce divide" has also been growing between those with college degrees and those without (a distinction that also often translates to differences in income). The figures are quite striking: College-educated Americans have seen their divorce rates drop by about 30% since the early 1980s, whereas Americans without college degrees have seen their divorce rates increase by about 6%. Just under a quarter of college-educated couples who married in the early 1970s divorced in their first ten years of marriage, compared to 34% of their less-educated peers. Twenty years later, only 17% of college-educated couples who married in the early 1990s divorced in their first ten years of marriage; 36% of less-educated couples who married in the early 1990s, however, divorced sometime in their first decade of marriage.

This growing divorce divide means that college-educated married couples are now about half as likely to divorce as their less-educated peers. Well-educated spouses who come from intact families, who enjoy annual incomes over $60,000, and who conceive their first child in wedlock — as many college-educated couples do — have exceedingly low rates of divorce.

Well-educated spouses who come from intact families, who enjoy annual incomes over $60,000, and who conceive their first child in wedlock — as many college-educated couples do — have exceedingly low rates of divorce.

Similar trends can be observed in measures of marital quality. For instance, if we look at married couples aged 18-60, 72% of spouses who were both college-educated and 65% of spouses who were both less-educated reported that they were "very happy" in their marriages in the 1970s, according to the General Social Survey. In the 2000s, marital happiness remained high among college-educated spouses, as 70% continued to report that they were "very happy" in their marriages. But marital happiness fell among less-educated spouses: Only 56% reported that they were "very happy" in their marriages in the 2000s.

These trends are mirrored in American illegitimacy statistics. Although one would never guess as much from the regular New York Times features on successful single women having children, non-marital childbearing is quite rare among college-educated women. According to a 2007 Child Trends study, only 7% of mothers with a college degree had a child outside of marriage, compared to more than 50% of mothers who had not gone to college.

According to a 2007 Child Trends study, only 7% of mothers with a college degree had a child outside of marriage, compared to more than 50% of mothers who had not gone to college.

So why are marriage and traditional child-rearing making a modest comeback in the upper reaches of society while they continue to unravel among those with less money and less education? Both cultural and economic forces are at work, each helping to widen the divorce and marriage divide in America.

First, while it was once the case that working-class and poor Americans held more conservative views of divorce than their middle- and upper-class peers, this is no longer so. For instance, a 2004 National Fatherhood Initiative poll of American adults aged 18-60 found that 52% of college-educated Americans endorsed the norm that in the "absence of violence and extreme conflict, parents who have an unsatisfactory marriage should stay together until their children are grown." But only 35% of less-educated Americans surveyed endorsed the same viewpoint.

Likewise, according to my analysis of the General Social Survey, in the 1970s only 36% of college-educated Americans thought divorce should be "more difficult to obtain than it is now," compared to 46% of less-educated Americans. By the 2000s, 49% of college-educated Americans thought divorce laws should be tightened, compared to 48% of less-educated Americans. Views of marriage have been growing more conservative among elites, but not among the poor and the less educated.

Second, the changing cultural meaning of marriage has also made it less necessary and less attractive to working-class and poor Americans. Prior to the 1960s, when the older, institutional model of marriage dominated popular consciousness, marriage was the only legitimate venue for having sex, bearing and raising children, and enjoying an intimate relationship. Moreover, Americans generally saw marriage as an institution that was about many more goods than a high-quality emotional relationship. Therefore, it made sense for all men and women — regardless of socioeconomic status — to get and stay married.

Yet now that the institutional model has lost its hold over the lives of American adults, sex, children, and intimacy can be had outside of marriage. All that remains unique to marriage today is the prospect of that high-quality emotional bond — the soul-mate model. As a result, marriage is now disproportionately appealing to wealthier, better-educated couples, because less-educated, less-wealthy couples often do not have the emotional, social, and financial resources to enjoy a high-quality soul-mate marriage.

The qualitative research of sociologists Kathryn Edin and Maria Kefalas, for instance, shows that lower-income couples are much more likely to struggle with conflict, infidelity, and substance abuse than their higher-income peers, especially as the economic position of working-class men has grown more precarious since the 1970s. Because of shifts away from industrial employment and toward service occupations, real wages and employment rates have dropped markedly for working-class men, but not for college-educated men. For instance, from 1973 to 2007, real wages of men with a college degree rose 18%; by contrast, the wages of high-school-educated men fell 11%. Likewise, in 1970, 96% of men aged 25-64 with high-school degrees or with college degrees were employed. By 2003, employment had fallen only to 93% for college-educated men of working age. But for working-aged men with only high-school degrees, labor-force participation had fallen to 84%, according to research by economist Francine Blau. These trends indicate that less-educated men have, in economic terms, become much less attractive as providers for their female peers than have college-educated men.

For instance, from 1973 to 2007, real wages of men with a college degree rose 18%; by contrast, the wages of high-school-educated men fell 11%. Likewise, in 1970, 96% of men aged 25-64 with high-school degrees or with college degrees were employed. By 2003, employment had fallen only to 93% for college-educated men of working age. But for working-aged men with only high-school degrees, labor-force participation had fallen to 84%, according to research by economist Francine Blau. These trends indicate that less-educated men have, in economic terms, become much less attractive as providers for their female peers than have college-educated men.

In other words, the soul-mate model of marriage does not extend equal marital opportunities. It therefore makes sense that fewer poor Americans would take on the responsibilities of modern married life, knowing that they are unlikely to reap its rewards.

The emergence of the divorce and marriage divide in America exacerbates a host of other social problems. The breakdown of marriage in working-class and poor communities has played a major role in fueling poverty and inequality, for instance. Isabel Sawhill at the Brookings Institution has concluded that virtually all of the increase in child poverty in the United States since the 1970s can be attributed to family breakdown. Meanwhile, the dissolution of marriage in working-class and poor communities has also fueled the growth of government, as federal, state, and local governments spend more money on police, prisons, welfare, and court costs, trying to pick up the pieces of broken families. Economist Ben Scafidi recently found that the public costs of family breakdown exceed $112 billion a year.

The breakdown of marriage in working-class and poor communities has played a major role in fueling poverty and inequality, for instance. Isabel Sawhill at the Brookings Institution has concluded that virtually all of the increase in child poverty in the United States since the 1970s can be attributed to family breakdown. Meanwhile, the dissolution of marriage in working-class and poor communities has also fueled the growth of government, as federal, state, and local governments spend more money on police, prisons, welfare, and court costs, trying to pick up the pieces of broken families. Economist Ben Scafidi recently found that the public costs of family breakdown exceed $112 billion a year.

Moreover, children in single-parent homes are more likely to be exposed to Hollywood's warped vision of sex, relationships, and family life. For instance, a study by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that children in single-parent homes devote almost 45 minutes more per day to watching television than children in two-parent homes. Given the distorted nature of the popular culture's family-related messages, and the unorthodox family relationships of celebrity role models, this means that children in single-parent families are even less likely to develop a healthy understanding of marriage and family life — and are therefore less likely to have a positive vision of their own marital future.

Given the distorted nature of the popular culture's family-related messages, and the unorthodox family relationships of celebrity role models, this means that children in single-parent families are even less likely to develop a healthy understanding of marriage and family life — and are therefore less likely to have a positive vision of their own marital future.

Thus, the fallout of America's retreat from marriage has hit poor and working-class communities especially hard, with children on the lower end of the economic spectrum doubly disadvantaged by the material and marital circumstances of their parents.

STRENGHTENING MARRIAGE

There are no magic cures for the growing divorce divide in America. But a few modest policy measures could offer some much-needed help.

First, the states should reform their divorce laws. A return to fault-based divorce is almost certainly out of the question as a political matter, but some plausible common-sense reforms could nonetheless inject a measure of sanity into our nation's divorce laws. States should combine a one-year waiting period for married parents seeking a divorce with programs that educate those parents about the likely social and emotional consequences of their actions for their children. State divorce laws should also allow courts to factor in spousal conduct when making decisions about alimony, child support, custody, and property division. In particular, spouses who are being divorced against their will, and who have not engaged in egregious misbehavior such as abuse, adultery, or abandonment, should be given preferential treatment by family courts. Such consideration would add a measure of justice to the current divorce process; it would also discourage some divorces, as spouses who would otherwise seek an easy exit might avoid a divorce that would harm them financially or limit their access to their children.

States should combine a one-year waiting period for married parents seeking a divorce with programs that educate those parents about the likely social and emotional consequences of their actions for their children. State divorce laws should also allow courts to factor in spousal conduct when making decisions about alimony, child support, custody, and property division. In particular, spouses who are being divorced against their will, and who have not engaged in egregious misbehavior such as abuse, adultery, or abandonment, should be given preferential treatment by family courts. Such consideration would add a measure of justice to the current divorce process; it would also discourage some divorces, as spouses who would otherwise seek an easy exit might avoid a divorce that would harm them financially or limit their access to their children.

Second, Congress should extend the federal Healthy Marriage Initiative. In 2006, as part of President George W. Bush's marriage initiative, Congress passed legislation allocating $100 million a year for five years to more than 100 programs designed to strengthen marriage and family relationships in America — especially among low-income couples. As Kathryn Edin of Harvard has noted, many of these programs are equipping poor and working-class couples with the relational skills that their better-educated peers rely upon to sustain their marriages. In the next year or two, many of these programs will be evaluated; the most successful programs serving poor and working-class communities should receive additional funding, and should be used as models for new programs to serve these communities. New ideas — like additional social-marketing campaigns on behalf of marriage, on the model of those undertaken to discourage smoking — should also be explored through the initiative.

As Kathryn Edin of Harvard has noted, many of these programs are equipping poor and working-class couples with the relational skills that their better-educated peers rely upon to sustain their marriages. In the next year or two, many of these programs will be evaluated; the most successful programs serving poor and working-class communities should receive additional funding, and should be used as models for new programs to serve these communities. New ideas — like additional social-marketing campaigns on behalf of marriage, on the model of those undertaken to discourage smoking — should also be explored through the initiative.

Third, the federal government should expand the child tax credit. Raising children is expensive, and has become increasingly so, given rising college and health-care costs. Yet the real value of federal tax deductions for children has fallen considerably since the 1960s. To remedy this state of affairs, Ramesh Ponnuru and Robert Stein have proposed expanding the current child tax credit from $1,000 to $5,000 and making it fully refundable against both income and payroll taxes. A reform along those lines would provide a significant measure of financial relief to working-class and middle-class families, and would likely strengthen their increasingly fragile marriages.

A reform along those lines would provide a significant measure of financial relief to working-class and middle-class families, and would likely strengthen their increasingly fragile marriages.

Of course, none of these reforms of law and policy alone is likely to exercise a transformative influence on the quality and stability of marriage in America. Such fixes must be accompanied by changes in the wider culture. Parents, churches, schools, public officials, and the entertainment industry will have to do a better job of stressing the merits of a more institutional model of marriage. This will be particularly important for poor and working-class young adults, who are drifting away from marriage the fastest.

This is a tall order, to say the least. But if our society is genuinely interested in protecting and improving the welfare of children — especially children in our nation's most vulnerable communities — we must strengthen marriage and reduce the incidence of divorce in America. The unthinkable alternative is a nation divided more and more by class and marital status, and children doubly disadvantaged by poverty and single parenthood. Surely no one believes that such a state of affairs is in the national interest.

The unthinkable alternative is a nation divided more and more by class and marital status, and children doubly disadvantaged by poverty and single parenthood. Surely no one believes that such a state of affairs is in the national interest.

Correction appended: Paul Amato estimates that, if the United States enjoyed the same level of family stability today as it did in 1960, the United States would have approximately 70,000 fewer suicide attempts every year, not 70,000 fewer suicides, as was originally stated in this article.

W. Bradford Wilcox is the director of the National Marriage Project at the University of Virginia and a senior fellow at the Institute for American Values.

Data of the Central Statistical Bureau of the USSR on marriages and divorces in the USSR in 1940, 1943-1954. and the first half of 1955

Data of the Central Statistical Bureau of the USSR on marriages and divorces in the USSR in 1940, 1943-1954. and I half of 1955 1

August 29, 1955 2

SOV. SECRET. About marriages and divorces in the USSR

SECRET. About marriages and divorces in the USSR

Total

City

Village

1940

1082

538

544

1943*

347

175

172

1944*

582

325

257

including:

I half year

265

139

126

II half year

317

186

131

1945

1106

637

469

1946

2100

1099

1001

1947

1859

865

994

1948

1917

908

1009

1949

2018

1002

1016

1950

2080

1059

1021

1951

2125

1085

1040

1952

1934

986

948

1953

2073

1087

986

1954

2163

1133

1030

including

I half year

1094

559

535

I half year 1955

1146

588

558

* Without the occupied territory

As can be seen from the above data, in the post-war years the number of registered marriages significantly exceeds the number of marriages in the pre-war 1940.

In addition to the growth in the material well-being of workers, the increase in the number of registered marriages is also associated with the demobilization of army contingents After the end of the Great Patriotic War and changes made to the laws on marriage, family and guardianship by Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR of July 8, 1944 years, which contributed to the strengthening of the Soviet family.

In the first half of 1955, the number of registered marriages increased by 5 percent compared with the first half of 1954.

Men

Women

1940

1950

1954

1940

1950

1954

Under 18

0. 1

1

0.1

0.0

2.7

0.7

1.1

18-19 years old

5.8

5.2

4.3

23.2

10.3

11.9

20-24 years old

27.6

37.3

33.3

37.5

43.9

41.8

25-29 years old

39.7

25.8

39.7

19.7

21.3

25.4

30-39 years old

18.8

17.2

11.9

12.0

15.2

13. 3

3

40-49 years

4.8

9.7

6.5

3.5

6.5

4.5

50-59 years

2.0

3.4

2.6

1.1

1.7

1.5

60 and over

1.2

1.3

1.7

0.3

0.4

0.5

Total

100

100

100

100

100

100

3. Most of the men and women who registered their marriage in 1954 entered into their first marriage. Below are the data on those who entered into a first marriage (as a percentage of those who married at a given age):

|

| 1940 | 1954 | ||

| men | women | men | women | |

| Under 20 | 98. | 96.0 | 99.9 | 99.9 |

| 20-24 years old | 95.2 | 89.7 | 99.4 | 98.8 |

| 25-29 years old | 87.4 | 75.3 | 97.3 | 94.7 |

| 30-39 years old | 59,6 | 49.3 | 87.8 | 83.1 |

| 40-49 years | 44.9 | 28.0 | 76.8 | 67.9 |

| 50-59 years | 15.3 | 17.3 | 59.3 | 59.7 |

| 60 and over | 10.3 | 26.4 | 43. | 54.9 |

| Total | 79.6 | 80.4 | 93.7 | 93.6 |

4. The number of divorces is characterized by the following data (thousands):

|

| Total | City | Village |

| 1940 | 205.0 | 108.0 | 97.0 |

| 1943* | 83.0 | 38.0 | 45.0 |

| 1944* | 69.0 | 33.0 | 36.0 |

| including: | |||

| I half year | 58. | 28.0 | 30.0 |

| 11 half year | 11.0 | 5.0 | 6.0 |

| 1945 | 6.5 | 5.9 | 0.6 |

| 1946 | 17.4 | 15.7 | 1.7 |

| 1947 | 28.7 | 25.4 | 3.3 |

| 1948 | 41.0 | 35.0 | 6.0 |

| 1949 | 55.9 | 46.7 | 9.2 |

| 1950 | 67.4 | 54.8 | 12.6 |

| 1951 | 76.7 | 62. | 14.7 |

| 1952 | 86.1 | 68.7 | 17.4 |

| 1953 | 98.4 | 79.5 | 18.9 |

| 1954 year | 114.4 | 97.0 | 17.4 |

| including | |||

| I half year | 55.9 | 47.0 | 8.9 |

| I half year 1955 | 63.6 | 57.2 | 6.4 |

* Without occupied territory

Men

Women

1940

1954

1940

1954

Under 20

1. 0

0

0.0

7.8

0.5

20-24 years old

12.7

5.9

28.2

16.3

25-29 years old

33.5

34.7

28.2

37.9

30-39 years old

34.8

38.0

25.1

32.1

40-49 years

11.9

17.1

7.8

11.0

50-59 years

4.0

3.5

2.3

1.9

60 and over

2.1

0.8

0. 6

6

0.3

Total

100

100

100

100

Length of marriage

Registered divorces

in thousands

percent

1940

1945

1950

1954

1940

1945

1950

1954

Less than one year

43.0

0.6

2. 1

1

3.4

21.0

8.7

3.1

3.0

1-4 years

89.7

2.0

25.6

36.7

43.8

31.0

37.9

32.1

5-9 years

37.7

2.1

14.1

47.3

18.4

32.6

20.9

41.3

10-19 years old

28.0

1.5

21.8

21.0

13.6

22.8

32.4

18.4

20 years or more

6. 6

6

0.3

3.8

6.0

3.2

4.9

5.7 .

5.2

Total

205.0

6.5

67.4

114.4

100

100

100

100

6. With the increase in the number of registered marriages in the post-war years, a significant number of children are born to mothers who are not in a registered marriage. Below are data on the number of births whose birth certificates do not contain a father’s record, that is, those born to mothers who are not in a registered marriage (before 1945, such registration was not conducted):

|

| Total births (thousands) | Including those born, in whose birth certificates there is no record of the father | |

| thousand | in % of the total number of births | ||

| 1945 | 2506 | 470 | 18. |

| 1946 | 4031 | 752 | 18.7 |

| 1947 | 4454 | 747 | 16.8 |

| 1948 | 4194 | 665 | 15.9 |

| 1949 | 5042 | 985 | 19.5 |

| 1950 | 4799 | 944 | 19.7 |

| 1951 | 4953 | 930 | 18.8 |

| 1952 | 4948 | 849 | 17.2 |

| 1953 | 4754 | 775 | 16.3 |

| 1954 | 5135 | 801 | 15. |

1 secret" statistical bulletin of the Central Statistical Bureau of the USSR No. 32 (338) dated 29August 1955 (RGAE. F. 1562. Op. 41. D. 89. JI. 68-131) in Section III "Reports on Certain Issues".

2 Date of publication of the statistical bulletin of the Central Statistical Bureau of the USSR (RGAE. F. 1562. Op. 41. D. 89. L. 68).

Mark Tolts on the Soviet experience of regulating the family life of citizens

On Tuesday, the President of the Russian Federation signed a law on liability for illegal abortions. There is no shortage of other proposals to tighten the legislative regulation of family policy. All of them are justified by the best intentions. And all in the case of their introduction would become only a repetition of the past. The Soviet experience of state intervention in the privacy of citizens was analyzed in his new work by Mark Tolts, a well-known specialist in the demographic history of the USSR.

Stalin's abortion thermidor

Abortions were allowed by the Leninist leadership of the country in 1920. Then Soviet Russia became the first state in the world to give a woman freedom of choice in such an important issue. The Bolsheviks were very proud of the liberal solution to the problem, and the world communist movement used it extensively in their propaganda, especially among women.

16 years later, on June 27, 1936, a resolution was adopted by the highest authorities - the Central Executive Committee and the Council of People's Commissars of the USSR - with the long title "On the prohibition of abortions, the increase in material assistance to women in childbirth, the establishment of state assistance to large families, the expansion of the network of maternity hospitals, nurseries and children's gardens, increased criminal penalties for non-payment of alimony and some changes in divorce laws.

As can be seen,

it was precisely the prohibition of abortion that stood in the first place in this resolution. This was his main goal.

This was his main goal.

There is no sex in Russia

The State Duma proposes to ban advertising of condoms outside the specialized media. At the same time they start...

02 April 23:16

Measures that spoke of “increasing material assistance to women in childbirth, establishing state assistance to large families, expanding the network of maternity hospitals, nurseries and kindergartens” were more like a cover because of their not very great effectiveness.

It should also be noted that this decree eliminated some excesses of the procedure for dissolution of marriage previously in force under the legislation of 1926. The divorce procedure was no longer one-sided: it now required the presence of both spouses. The very same freedom of divorce remained inviolable.

The timing of the abortion ban suggests a possible connection with the Great Terror of 1937-1938 that followed.

Didn't Stalin preoccupy himself with making up in advance at the expense of the birth rate the large population losses he had planned for these years? It is unlikely that he could only think about the number of future soldiers. After all, Stalin, of course, understood that he would receive an additional number of them only after almost 20 years. Another thing is that any increase in the number of births is immediately reflected in the dynamics of the total population, maintaining its size. This, probably, was what he needed, since he conceived the Great Terror. However, someone else's soul is in the dark, especially if we are talking about the real motives of the leader.

After all, Stalin, of course, understood that he would receive an additional number of them only after almost 20 years. Another thing is that any increase in the number of births is immediately reflected in the dynamics of the total population, maintaining its size. This, probably, was what he needed, since he conceived the Great Terror. However, someone else's soul is in the dark, especially if we are talking about the real motives of the leader.

close

100%

What was the extent of the damage caused to the population of the country by the Great Terror? Here you can not trust the statistics, which were obviously incomplete. According to the estimates of three leading Russian experts on population losses (E.M. Andreev, L.E. Darsky and T.L. Kharkova), performed by the demographic balance method, the total actual number of victims of this wave of terror was about 2 million people.

This figure includes not only those who were shot, but also all possible losses associated with the Great Terror, including those not taken into account by any statistics.

According to the same authors, the increase in the number of births after the ban on abortion amounted to almost 1 million in 1937 and 1938 compared to 1936. However, already in 1940, the birth rate again fell noticeably, which is natural. After a ban, abortion always quickly goes underground.

In 1940 alone, more than 2,000 women died of this cause in the cities of the Russian Federation.

Throughout the entire period of this ban in the USSR, from 1936 to 1955, probably tens of thousands of women became its victims, who paid for the measures of totalitarian pronatalism with their lives.

Totalitarian management of the family

Decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR, adopted on July 8, 1944, did not even mention in the title the profound changes that brought to the life of Soviet families. Let us quote this deceptive title in full: “On increasing state assistance to pregnant women, mothers of many children and single mothers, strengthening the protection of motherhood and childhood, establishing the highest degree of distinction of the title “Mother-Heroine” and establishing the Order of Maternal Glory and the medal “Medal of Motherhood”.

This decree was the first document in the subsequent chain of those totalitarian toughenings that under the late Stalin deprived Soviet society of the remnants of freedom. The main thing in it was that it introduced significant restrictions on the possibility of divorce. They established a very complex and expensive procedure for dissolution of marriage in court.

In this it was very similar to the laws of the Russian Empire, where extreme difficulties were imposed on divorce for the Orthodox majority.

This was a radical break with the liberal approach to family matters that the Bolsheviks adhered to when they came to power.

“Freedom of divorce,” Lenin clearly formulated his position, “does not mean the disintegration of family ties, but, on the contrary, their strengthening on the only possible and sustainable democratic foundations in a civilized society.”

Limiting divorce, of course, does not strengthen marriage. Rather, it leads to the disorganization of family relations, contributes to the massive emergence of new de facto unions that remain outside the scope of legal regulation.

Everything turns out contrary to the seemingly good intentions of yesterday's and today's supporters of "strengthening the bonds of marriage."

Moreover, it does nothing to increase the birth rate. After all, people are deprived of the legal opportunity to create a new family for a long time after the actual collapse of the old one. It turns out that it is the restriction of divorce that leads to the growth of unregistered unions, and often to the fear of marriage, since it is so difficult to dissolve.

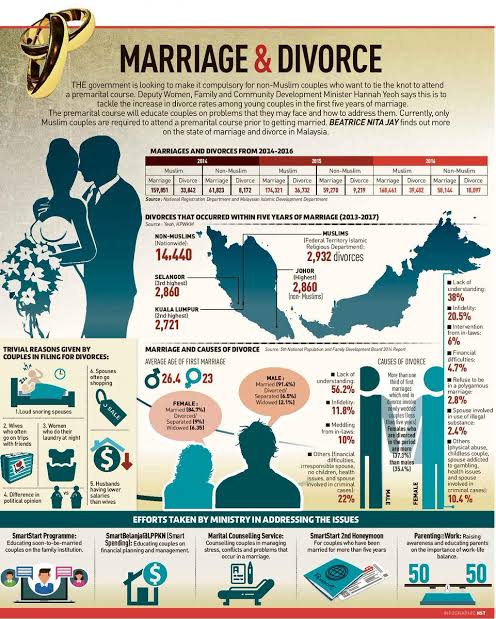

Of course, the imposed restrictions immediately drastically reduced the number of officially registered divorces. In 1940, 205 thousand of them were registered. After the introduction of restrictions, it fell 31 times, to 6.6 thousand in 1945 year.

Decree of 1944 also introduced a new concept - "single mother".

It applied to all women who gave birth to children out of wedlock. Henceforth, these women could not claim material assistance from the father of the child.

Moreover, the father, with all his desire, if he was not married to the mother of the child, could not be recorded in the documents certifying the birth of a son or daughter. In the metric of children born out of wedlock, it became mandatory to put a dash instead of information about the father. Thus arose the stigma of a dash in the metric. Likewise, over 15 million children were stigmatized during the entire period of this unkind legislative measure, which outlived Stalin for a long time.

“We ask those born to be given patronymics”

The collective leadership that came to power in the USSR after Stalin's death initiated various positive changes. At the same time, it canceled a part - by no means all! - tough legislative prohibitions established during the period of the leader's sole rule, which adversely affected the population of the country.

In particular, in 1955, the ban on artificial termination of pregnancy, introduced in 1936, was abolished.

After abortion came out of the underground, the number of hospital operations in 1960 was 3.5 times more than in 1954. But the number of births just in 1960 was the highest for all the first 15 post-war years, amounting to 5.3 million. The drop in the number of births came much later than the ban on abortion in the country was lifted. This well illustrates one of the basic postulates of demographics in the field of fertility, shared by all true specialists:

abortion is only a means of limiting the number of children when the family strives for this, but not the cause of the low birth rate.

Naturally, the dash in the metrics established in 1944 in the information about the father, who was “awarded” at birth to children born out of wedlock, could not but excite those who were really a humanist. After the 20th Congress, the writers Marshak and Ehrenburg, the composer Shostakovich, and the leading pediatrician Academician Speransky spoke out against this savagery in the Literary Gazette.

Marshak, the first of the authors of this open letter, also prepared a verse presentation of this appeal (at that time it remained unpublished), which well reveals its essence:

On behalf of many mothers,

Those who have experienced the pain of loneliness,

We ask the Supreme Council to return their patronymic names as soon as possible

.

On behalf of the citizens of future years,

Still not having a handwriting,

We, adults, ask the Supreme Council

Give them a patronymic instead of a dash.

We ask those born to give a middle name

Instead of these dashes-blots,

Let their father and mother not go

Love to register in the registry office.

………………………………………

…………………………………………

So let them be equal to 9 in metrics2185 Children born for happiness.

Unfortunately, soon after the publication of the open letter, the subsequent Hungarian events - the uprising in Budapest and its suppression by Soviet troops - diverted attention. The initiative of the four authors of the appeal had no consequences. No changes followed.

The initiative of the four authors of the appeal had no consequences. No changes followed.

Five years later, a new collective appeal was prepared to Literaturnaya Gazeta on the same subject, which Marshak, Ehrenburg and Shostakovich were again ready to sign. Together with them, Kaverin and Chukovsky now wanted to appear in the press. But this appeal remained unpublished.

Even such an informed participant in the events as the well-known lawyer and journalist Vaksberg, who worked on the text of this letter, did not suspect who was standing in the way of all good initiatives to correct family law. He considered from the post-Stalin leadership only Molotov and Malenkov "directly involved" in the appearance of ugly institutions. Therefore, in his memoirs, he was very surprised that their removal from power in 1957 did not change anything.

C 1958 to 1964, Khrushchev concentrated all power in the country in his hands. As soon as the Japanese researcher M. Nakachi managed to establish recently, it was Khrushchev who formulated the main provisions of the 1944 decree. Stalin, of course, always had the last word in decision-making, but the role of his “faithful associates”, in this case Khrushchev, which is well shown, for example, by archival materials related to the adoption of the notorious decree, was sometimes very active.

Stalin, of course, always had the last word in decision-making, but the role of his “faithful associates”, in this case Khrushchev, which is well shown, for example, by archival materials related to the adoption of the notorious decree, was sometimes very active.

close

100%

Additional light on the prehistory of his appearance is shed by the following entry made on August 28, 1943 in the diary of the famous film director A. Dovzhenko, published only recently:

[Khrushchev] reminded me of my proposal for a new form of marriage told the People's Commissar of Internal Affairs, who also treated her with love. Therefore, one of these days I will begin to develop a project on marriage.

Every leader, including the leader of Soviet Ukraine Khrushchev, had an inner circle, and Dovzhenko was a member of it. Apparently, in this circle, future important changes in family policy were initially formed.

Now, knowing all this, one can understand why the ugly provisions of the 1944 decree, which was Khrushchev's favorite brainchild, remained unchanged until the end of his reign.

"Dear Nikita Sergeevich", as you know, was not distinguished by liberalism. But the fact that in adherence to his totalitarian marriage and family legislation he showed the undoubted constancy of a reactionary deserves close attention. Here he did not have any throwing from side to side, so characteristic of this leader of the country in many other issues.

But the problems of marriage and family are one of the main problems in the life of any society. This, I think, requires a new rethinking of the nature of the Khrushchev era, taking into account this circumstance. Moreover, it is worth remembering that Lysenkoism - the suppression of Soviet genetics - only became a thing of the past with his rule.

Brezhnev's legislative liberalism

Change became possible only after Khrushchev's removal from power in October 1964. Collective leadership again operated in the country. Already on December 10, 1965, a decree of the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR was adopted, which significantly simplified the procedure for dissolution of marriage in the courts. This decree abolished the complex two-stage divorce procedure and the need to publish announcements in newspapers about the upcoming trial in court.

This decree abolished the complex two-stage divorce procedure and the need to publish announcements in newspapers about the upcoming trial in court.

In the absence of common children and disputes between spouses, a divorce could now be immediately processed by them directly at the registry office.

close

100%

Simultaneously under the new family law at 19In 68, the notorious dash in the metrics was canceled. This was done before the events in Czechoslovakia, and this time foreign policy circumstances did not disrupt the legislative reform. Now the birth of a child out of wedlock could be registered either at the joint application of his parents, or only at the request of the mother. In the latter case, the information about the father was filled in from the words of the mother, while her surname was indicated for the father.

After these changes in legislation, 43% of children born out of wedlock at 19In the 1970s, they were registered on the joint application of their parents. It is clear that these children now had a legal father. And these figures remained until the end of the Soviet period.

It is clear that these children now had a legal father. And these figures remained until the end of the Soviet period.