Diagnosis of young children with adhd is particularly difficult because

Diagnosing ADHD in Children: Guidelines & Information for Parents

Your pediatrician will determine whether your child has ADHD using standard guidelines developed by the American Academy of Pediatrics. These diagnosis guidelines are specifically for children 4 to 18 years of age.

It is difficult to diagnose ADHD in children younger than 4 years. This is because younger children change very rapidly. It is also more difficult to diagnose ADHD once a child becomes a teenager.

There is no single test for ADHD. The process requires several steps and involves gathering a lot of information from multiple sources. You, your child, your child's school, and other caregivers should be involved in assessing your child's behavior.

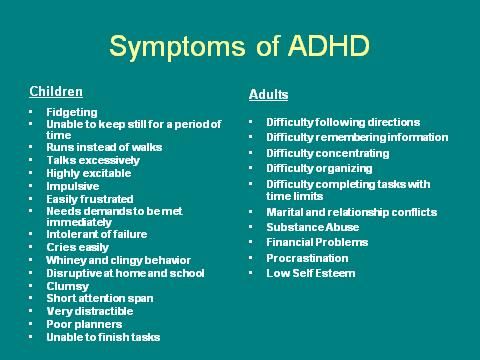

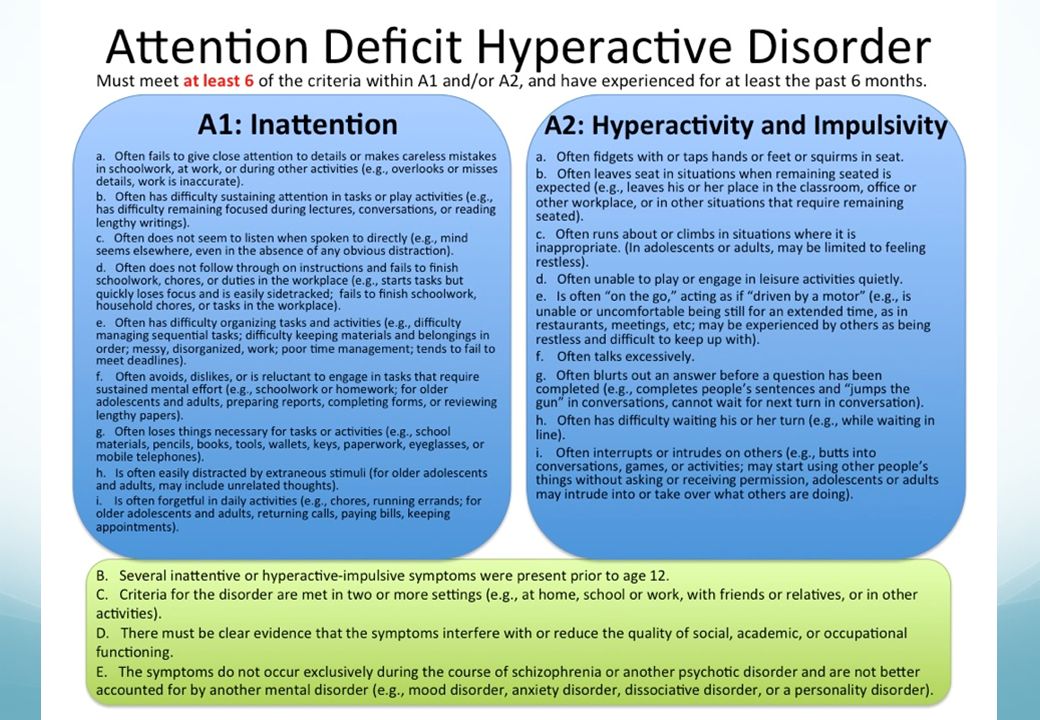

Children with ADHD show signs of inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity in specific ways. See the behaviors listed in the table below.

Your pediatrician will look at how your child's behavior compares to that of other children her own age, based on the information reported about your child by you, her teacher, and any other caregivers who spend time with your child, such as coaches or child care workers.

The following guidelines are used to confirm a diagnosis of ADHD:

- Symptoms occur in 2 or more settings, such as home, school, and social situations, and cause some impairment.

- In a child 4 to 17 years of age, 6 or more symptoms must be identified.

- In a child 17 years and older, 5 or more symptoms must be identified.

- Symptoms significantly impair your child's ability to function in some of the activities of daily life, such as schoolwork, relationships with you and siblings, relationships with friends, or the ability to function in groups such as sports teams.

- Symptoms start before the child reaches 12 years of age. However, these may not be recognized as ADHD symptoms until a child is older.

- Symptoms have continued for more than 6 months.

In addition to looking at your child's behavior, your pediatrician will do a physical and neurologic examination. A full medical history will be needed to put your child's behavior in context and screen for

other conditions that may affect her behavior. Your pediatrician also will talk with your child about how your child acts and feels.

Your pediatrician also will talk with your child about how your child acts and feels.

Your pediatrician may refer your child to a pediatric subspecialist or mental health clinician if there are concerns in one of the following areas:

- Intellectual disability (formerly called mental retardation)

- Developmental disorder such as speech problems, motor problems, or a learning disability

- Chronic illness being treated with a medication that may interfere with learning

- Trouble seeing and/or hearing

- History of abuse

- Major anxiety or major depression

- Severe aggression

- Possible seizure disorder

- Possible sleep disorder

How can parents help with the diagnosis?

As a parent, you will provide crucial information about your child's behavior and how it affects her life at home, in school, and in other social settings. Your pediatrician will want to know what symptoms your child is showing, how long the symptoms have occurred, and how the behavior affects your child and your family. You may need to fill in checklists or rating scales about your child's behavior.

You may need to fill in checklists or rating scales about your child's behavior.

In addition, sharing your family history can offer important clues about your child's condition.

Keep safety in mind:

If your child shows any symptoms of ADHD, it is very important that you pay close attention to safety. A child with ADHD may not always be aware of dangers and can get hurt easily. Be especially careful around:

- Traffic

- Firearms

- Swimming pools

- Tools such as lawn mowers

- Poisonous chemicals, cleaning supplies, or medicines

How will my child's school be involved?

For an accurate diagnosis, your pediatrician will need to get information about your child directly from your child's classroom teacher or another school professional. Children at least 4 years and older spend many of their waking hours at preschool or school. Teachers provide valuable insights. Your child's teacher may write a report or discuss the following topics with your pediatrician:

- Your child's behavior in the classroom

- Your child's learning patterns

- How long the symptoms have been a problem

- How the symptoms are affecting your child's progress at school

- Ways the classroom program is being adapted to help your child

- Whether other conditions may be affecting the symptoms

In addition, your pediatrician may want to see report cards, standardized tests, and samples of your child's schoolwork.

How will others who care for my child be involved?

Other caregivers may also provide important information about your child's behavior. Former teachers, religious and scout leaders, or coaches may have valuable input. If your child is homeschooled, it is especially important to assess his behavior in settings outside of the home.

Your child may not behave the same way at home as he does in other settings. Direct information about the way your child acts in more than one setting is required. It is important to consider other possible causes of your child's symptoms in these settings.

In some cases, other mental health care professionals may also need to be involved in gathering information for the diagnosis.

Are there other tests for ADHD?

You may have heard theories about other tests for ADHD. There are no other proven tests for ADHD at this time.

Many theories have been presented, but studies have shown that the following tests have little value in diagnosing an individual child:

- Screening for high lead levels in the blood

- Screening for thyroid problems

- Computerized continuous performance tests

- Brain imaging studies such as CAT scans and MRIs

- Electroencephalogram (EEG) or brain-wave test

While these tests are not helpful in diagnosing ADHD, your pediatrician may see other signs or symptoms in your child that warrant blood tests, brain imaging studies, or an EEG.

Additional Information on HealthyChildren.org:

- Understanding ADHD: Information for Parents

- Causes of ADHD: What We Know Today

- Treatment & Target Outcomes for Children with ADHD

- Common ADHD Medications & Treatments for Children

- How Schools Can Help Children with ADHD

Additional Resources:

The following is a list of support groups and additional resources for further information about ADHD. Check with your pediatrician for resources in your community.

- National Resource Center on AD/HD

- How Is ADHD Diagnosed? Video (Understood.org)

- Children and Adults with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (CHADD) or 800/233-4050

- Attention Deficit Disorder Association or 856/439-9099

- Center for Parent Information and Resources

- National Institute of Mental Health or 866/615-6464

- Tourette Association of America or 888/4-TOURET (486-8738)

The information contained on this Web site should not be used as a substitute for the medical care and advice of your pediatrician. There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

There may be variations in treatment that your pediatrician may recommend based on individual facts and circumstances.

ADHD in children and youth: Part 1—Etiology, diagnosis, and comorbidity

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5 th edn (DSM-5). Washington, DC: APA, 2013:59–66. [Google Scholar]

2. Polanczyk GV, Salum GA, Sugaya LS, Caye A, Rohde LA. Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2015;56(3):345–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Polanczyk GV, Willcutt EG, Salum GA, Kieling C, Rohde LA. ADHD prevalence estimates across three decades: An updated systematic review and meta-regression analysis. Int J Epidemiol 2014;43(2):434–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Visser SN, Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, et al.. Trends in the parent-report of health care provider-diagnosed and medicated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: United States, 2003–2011. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;53(1):34–46.e2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2014;53(1):34–46.e2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. The ICD-10 classification of mental and behavioural disorders. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO, 1993. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Loe IM, Feldman HM. Academic and educational outcomes of children with ADHD. Ambul Pediatr 2007;7(1 Suppl):82–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Hoza B. Peer functioning in children with ADHD. J Pediatr Psychol 2007;32(6):655–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Whiteford HA, Degenhardt L, Rehm J, et al.. Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the global burden of disease study 2010. Lancet 2013;382(9904):1575–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Erskine HE, Ferrari AJ, Polanczyk GV, et al.. The global burden of conduct disorder and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in 2010. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2014;55(4):328–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Dalsgaard S, Østergaard SD, Leckman JF, Mortensen PB, Pedersen MG. Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A nationwide cohort study. Lancet 2015;385(9983):2190–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Mortality in children, adolescents, and adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: A nationwide cohort study. Lancet 2015;385(9983):2190–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Lara C, Fayyad J, de Graaf R, et al.. Childhood predictors of adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Results from the World Health Organization World Mental Health Survey Initiative. Biol Psychiatry 2009;65(1):46–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Akutagava-Martins GC, Rohde LA, Hutz MH. Genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: An update. Expert Rev Neurother 2016;16(2):145–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Faraone SV, Mick E. Molecular genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2010;33(1):159–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Gizer IR, Ficks C, Waldman ID. Candidate gene studies of ADHD: A meta-analytic review. Hum Genet 2009;126(1):51–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Stergiakouli E, Hamshere M, Holmans P, et al. ; deCODE Genetics; Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Investigating the contribution of common genetic variants to the risk and pathogenesis of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169(2):186–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

; deCODE Genetics; Psychiatric GWAS Consortium Investigating the contribution of common genetic variants to the risk and pathogenesis of ADHD. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169(2):186–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Williams NM, Franke B, Mick E, et al.. Genome-wide analysis of copy number variants in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: The role of rare variants and duplications at 15q13.3. Am J Psychiatry 2012;169(2):195–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Li Z, Chang SH, Zhang LY, Gao L, Wang J. Molecular genetic studies of ADHD and its candidate genes: A review. Psychiatry Res 2014;219(1):10–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Linnet KM, Dalsgaard S, Obel C, et al.. Maternal lifestyle factors in pregnancy risk of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and associated behaviors: Review of the current evidence. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(6):1028–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Nigg JT. What Causes ADHD? Understanding What Goes Wrong and Why. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2006. [Google Scholar]

20. Ozlem E. What causes ADHD?AAP Grand Rounds 2012;27(6):72. [Google Scholar]

21. Cruikshank BM, Eliason M, Merrifield B. Long-term sequelae of cold water near-drowning. J Pediatr Psychol 1988;13(3):379–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Hesdorffer DC, Ludvigsson P, Olafsson E, Gudmundsson G, Kjartansson O, Hauser WA. ADHD as a risk factor for incident unprovoked seizures and epilepsy in children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61(7):731–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Max JE, Schachar RJ, Levin HS, et al.. Predictors of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder within 6 months after pediatric traumatic brain injury. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005;44(10):1032–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Max JE, Schachar RJ, Levin HS, et al.. Predictors of secondary attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents 6 to 24 months after traumatic brain injury. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2005;44(10):1041–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Levin H, Hanten G, Max J, et al.. Symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder following traumatic brain injury in children. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2007;28(2):108–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Peterson BS, Rauh VA, Bansal R, et al.. Effects of prenatal exposure to air pollutants (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) on the development of brain white matter, cognition, and behavior in later childhood. JAMA Psychiatry 2015;72(6):531–40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Hong SB, Im MH, Kim JW, et al.. Environmental lead exposure and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptom domains in a community sample of South Korean school-age children. Environ Health Perspect 2015;123(3):271–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Kreppner JM, O’Connor TG, Rutter M; English and Romanian Adoptees Study Team Can inattention/overactivity be an institutional deprivation syndrome?J Abnorm Child Psychol 2001;29(6):513–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Thapar A, Cooper M, Jefferies R, Stergiakouli E. What causes attention deficit hyperactivity disorder?Arch Dis Child 2012;97(3):260–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Hjern A, Weitoft GR, Lindblad F. Social adversity predicts ADHD-medication in school children—A national cohort study. Acta Paediatr 2010;99(6):920–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Klein B, Damiani-Taraba G, Koster A, Campbell J, Scholz C. Diagnosing attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children involved with child protection services: Are current diagnostic guidelines acceptable for vulnerable populations?Child Care Health Dev 2015;41(2):178–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Castellanos FX, Lee PP, Sharp W, et al.. Developmental trajectories of brain volume abnormalities in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA 2002;288(14):1740–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Bush G, Valera EM, Seidman LJ. Functional neuroimaging of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A review and suggested future directions. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(11):1273–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Functional neuroimaging of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A review and suggested future directions. Biol Psychiatry 2005;57(11):1273–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Poelmans G, Pauls DL, Buitelaar JK, Franke B. Integrated genome-wide association study findings: Identification of a neurodevelopmental network for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2011;168(4):365–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Arnsten AF, Paspalas CD, Gamo NJ, Yang Y, Wang M. Dynamic network connectivity: A new form of neuroplasticity. Trends Cogn Sci 2010;14(8):365–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Barkeley RA. Etiologies of ADHD. In: Barkeley RA, ed. Attention-deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Handbook for Diagnosis and Treatment, 4 th edn. New York, NY: Guilford Press, 2015. [Google Scholar]

37. Shaw P, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, et al.. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007;104(49):19649–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. AAP Subcommittee on ADHD; Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management , Wolraich M, et al.. ADHD: Clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics 2011;128(5):1007–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Pliszka S; AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2007;46(7):894–921. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. McGoey KE, DuPaul GJ, Haley E, Shelton TL. Parent and teacher ratings of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in preschool: The ADHD rating scale-IV preschool version. J Psychopathol Behav Assess 2007;29(4):269–76. [Google Scholar]

41. Bonati M, Reale L, Zanetti M, et al. A regional ADHD center-based network project for the diagnosis and treatment of children with ADHD. J Atten Disord 2015;pii:1087054715599573 (Epub ahead of print). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Atten Disord 2015;pii:1087054715599573 (Epub ahead of print). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Ouyang L, Fang X, Mercy J, Perou R, Grosse SD. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder symptoms and child maltreatment: A population-based study. J Pediatr 2008;153(6):851–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Williams AE, Giust JM, Kronenberger WG, Dunn DW. Epilepsy and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: Links, risks, and challenges. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:287–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Lo-Castro A, D’Agati E, Curatolo P. ADHD and genetic syndromes. Brain Dev 2011;33(6):456–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Siegel MS, Smith WE. Psychiatric features in children with genetic syndromes: Toward functional phenotypes. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am 2010;19(2):229–61, viii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Templer AK, Titus JB, Gutmann DH. A neuropsychological perspective on attention problems in neurofibromatosis type 1. J Atten Disord 2013;17(6):489–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Atten Disord 2013;17(6):489–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Sullivan K, Hatton D, Hammer J, et al.. ADHD symptoms in children with FXS. Am J Med Genet A 2006;140(21):2275–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. D’Agati E, Moavero R, Cerminara C, Curatolo P. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol 2009;24(10):1282–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Canadian Interorganizational Steering Group for Speech-Language Pathology and Audiology. Canadian Guidelines on Auditory Processing Disorder in Children and Adults: Assessment and Intervention, December 2012: www.cisg-gdci.ca (Accessed January 24, 2018).

50. Bailey T. Beyond DSM: The role of auditory processing in attention and its disorders. Appl Neuropsychol Child 2012;1(2):112–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Larson K, Russ SA, Kahn RS, Halfon N. Patterns of comorbidity, functioning, and service use for US children with ADHD, 2007. Pediatrics 2011;127(3):462–70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Brown TE, ed. ADHD Comorbidities: Handbook for ADHD Complications in Children and Adults. Arlington, VA: APA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

53. Rommelse NN, Altink ME, Fliers EA, et al.. Comorbid problems in ADHD: Degree of association, shared endophenotypes, and formation of distinct subtypes. Implications for a future DSM. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2009;37(6):793–804. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Dunn DW, Kronenberger WG. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Neurol Clin 2003;21(4):933–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Abramovitch A, Dar R, Mittelman A, Wilhelm S. Comorbidity between attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder across the lifespan: A systematic and critical review. Harv Rev Psychiatry 2015;23(4): 245–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Halldorsdottir T, Ollendick TH. Comorbid ADHD: Implications for the treatment of anxiety disorders in children and adolescents. Cogn Behav Practice 2014;21(3):310–22. [Google Scholar]

Cogn Behav Practice 2014;21(3):310–22. [Google Scholar]

57. Boylan K, Georgiades K, Szatmari P. The longitudinal association between oppositional and depressive symptoms across childhood. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49(2):152–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, et al.. Is ADHD a risk factor for psychoactive substance use disorders? Findings from a four-year prospective follow-up study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 1997;36(1):21–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Mariani JJ, Levin FR. Treatment strategies for co-occurring ADHD and substance use disorders. Am J Addict 2007;16(Suppl 1:45–54; quiz 55–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Humphreys KL, Eng T, Lee SS. Stimulant medication and substance use outcomes: A meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70(7):740–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Pidsosny IC, Virani A. Pediatric psychopharmacology update: Psychostimulants and tics—Past, present and future. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006;15(2):84–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2006;15(2):84–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Lin YJ, Lai MC, Gau SS. Youths with ADHD with and without tic disorders: Comorbid psychopathology, executive function and social adjustment. Res Dev Disabil 2012;33(3):951–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Harris SR, Mickelson EC, Zwicker JG. Diagnosis and management of developmental coordination disorder. CMAJ 2015;187(9):659–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Brossard-Racine M, Shevell M, Snider L, Bélanger SA, Majnemer A. Motor skills of children newly diagnosed with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder prior to and following treatment with stimulant medication. Res Dev Disabil 2012;33(6):2080–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. DuPaul GJ, Gormley MJ, Laracy SD. Comorbidity of LD and ADHD: Implications of DSM-5 for assessment and treatment. J Learn Disabil 2013;46(1):43–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Levin RL, Rawana JS. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and eating disorders across the lifespan: A systematic review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev 2016;50:22–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clin Psychol Rev 2016;50:22–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Nazar BP, Suwwan R, de Sousa Pinna CM, et al.. Influence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on binge eating behaviors and psychiatric comorbidity profile of obese women. Compr Psychiatry 2014;55(3):572–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. MacMillan JA, Land M Jr, Leslie LK. Pediatric residency education and the behavioral and mental health crisis: A call to action. Pediatrics 2017;139(1):pii:e20162141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Andrews A, Mahoney W, eds. Children with School Problems: A Physician’s Manual, 2 nd edn. Toronto, Ont: John Wiley and Sons, 2012. [Google Scholar]

70. Rappley MD. Clinical practice. Attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder. N Engl J Med 2005;352(2):165–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Jones KL, Jones MC, del Campo M, eds. Smith’s Recognizable Patterns of Human Malformation, 7 th edn. New York, NY: Elsevier, 2013. [Google Scholar]

72. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidelines: www. nice.org.uk; updated February 2016 (Accessed January 24, 2018).

nice.org.uk; updated February 2016 (Accessed January 24, 2018).

73. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of attention deficit and hyperkinetic disorders in children and young people: www.sign.ac.uk, 2009. (Accessed January 24, 2018).

74. Graham J, Banaschewski T, Buitelaar J, et al.; European Guidelines Group European guidelines on managing adverse effects of medication for ADHD. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;20(1):17–37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Taylor E, Dofner M, Sargant J, et al.. European clinical guidelines for hyperkinetic disorder—first upgrade. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2004;13 (Suppl 1):17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: epidemiology, comorbidity and diagnosis

Elis Charach, MSc, MD

Hospital for Sick Children, Canada

(English). Translation: November 2015

Translation: November 2015

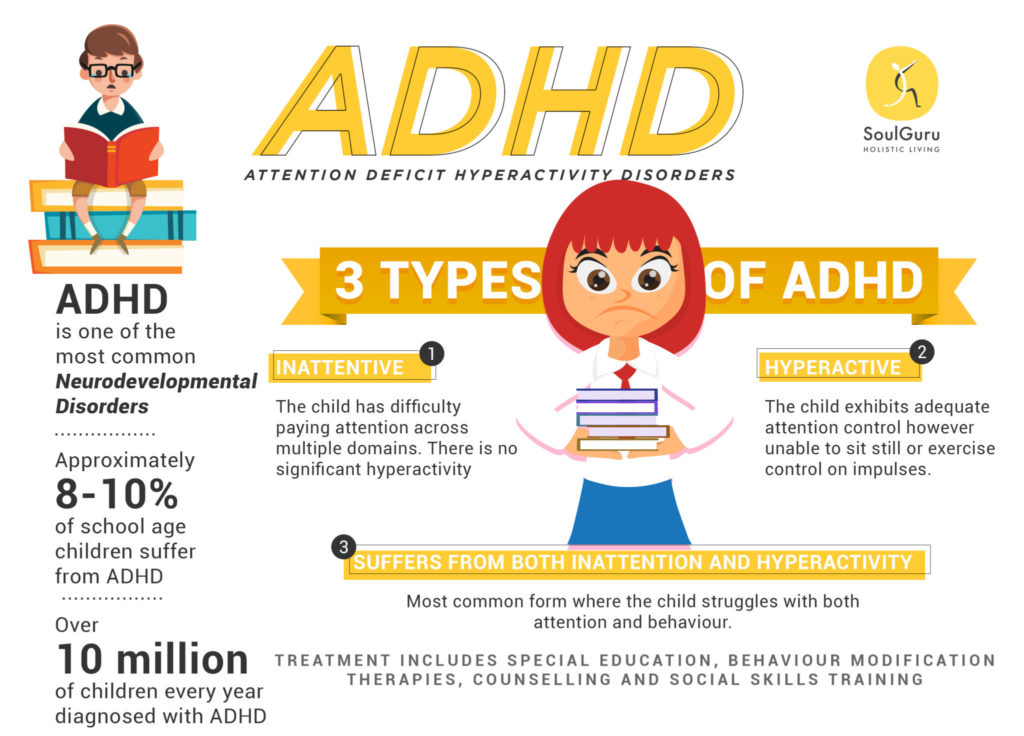

Epidemiology of ADHD

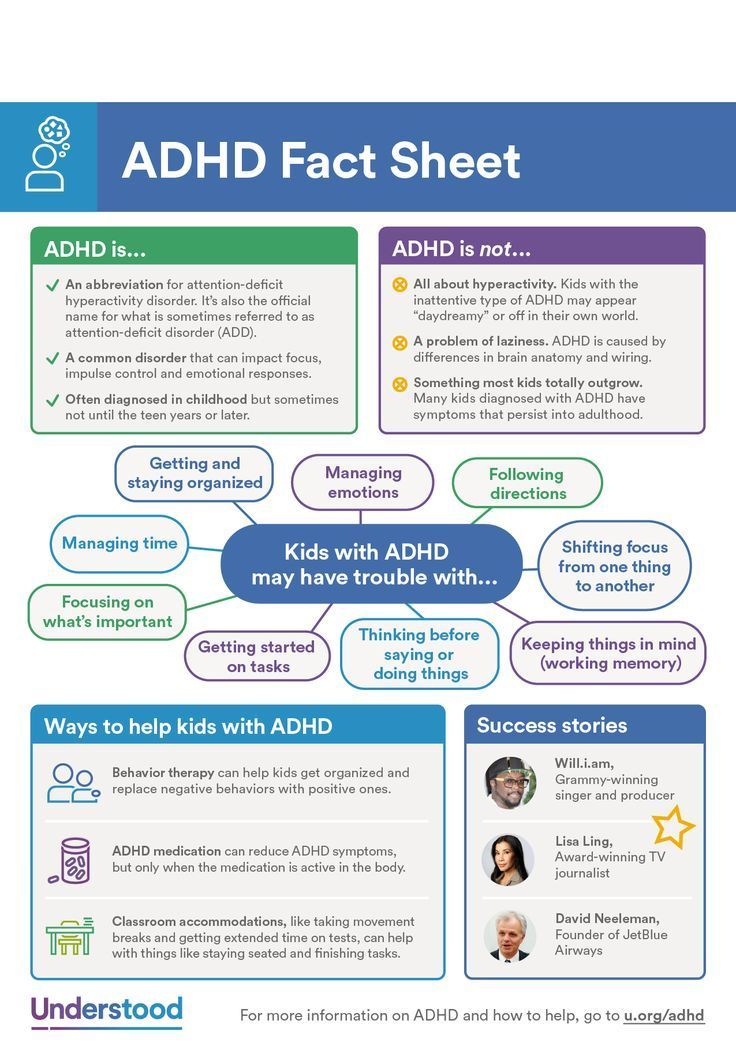

Children with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), which is characterized by levels of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity beyond the normal age range, are most often identified and treated in primary school. Studies around the world have identified an ADHD prevalence rate equivalent to 5.29% (95% CI: 5.01-5.56) among children and adolescents. 1 Rates are higher for boys than for girls and for children under 12 years of age compared to adolescents. 1.2 Estimates of prevalence depend on the method of determination, the diagnostic criteria used, and whether criteria for assessing functional disorders are included. 1 Overall, country rates are almost the same, except in Africa and the Middle East, where prevalence rates are lower than in North America and Europe. 1

1

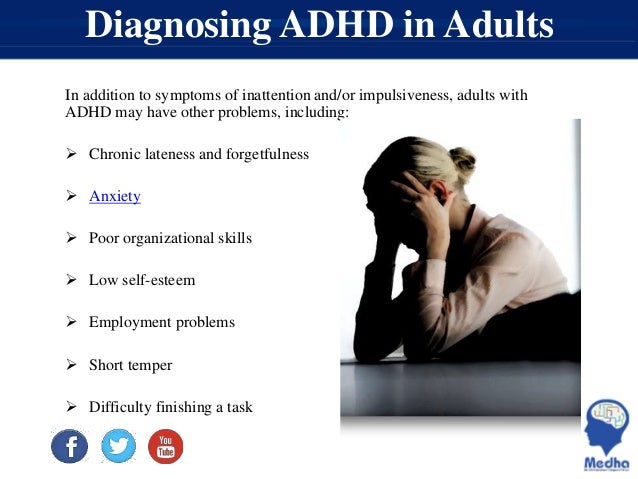

Symptoms typically cause functional difficulties with behavior and schoolwork, and often disrupt family and peer relationships. 3.4 Children with ADHD are more likely to seek health care services and have an increased percentage of injuries compared to children without the condition. 5.6 While symptoms of hyperactivity decrease during adolescence, most children with ADHD continue to show some cognitive impairment (eg, executive function deficits, working memory impairment) compared to their peers in adolescence and adulthood. 7.8 Research has found lower high school completion rates, earlier initiation of alcohol and illegal substance use, higher rates of cigarette smoking and car accidents among adolescents with ADHD. 9-14 Hyperactivity in childhood is also associated with the subsequent onset of other psychiatric disorders, including anxiety, behavioral disorders, affective disorders, suicidal behavior, and antisocial personality disorder. 13.15-18 Adults with a childhood history of ADHD have higher than expected rates of injuries and accidents, marital and work difficulties, teenage pregnancies, and children born out of wedlock. 15,17,19-21 ADHD is an important public health issue, not only because of the long-term hardship experienced by individuals and families, but also because of the heavy burden placed on the educational, health care, and criminal justice systems. 22-24

13.15-18 Adults with a childhood history of ADHD have higher than expected rates of injuries and accidents, marital and work difficulties, teenage pregnancies, and children born out of wedlock. 15,17,19-21 ADHD is an important public health issue, not only because of the long-term hardship experienced by individuals and families, but also because of the heavy burden placed on the educational, health care, and criminal justice systems. 22-24

Population studies have found that child inattention and hyperactivity are more common in single-parent families, as well as in families with low parental education, parental unemployment and low income. 17,25,26 Data from family studies suggest that ADHD symptoms are highly heritable, 27 however, early environmental factors also play a role. Smoking and maternal alcohol consumption in the prenatal (antenatal) period, low birth weight, and developmental problems are associated with high levels of inattention and hyperactivity. 26.28 More recently, a review of longitudinal data from The Canadian National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth found that approximately 7% of children show persistently high levels of parental hyperactivity from two years of age to the first grades of primary schools. 29 Maternal smoking during the prenatal period, maternal depression, poor parenting practices, and living in a disadvantaged neighborhood in the early years of life are all associated with later childhood behavior problems, including inattention and hyperactivity 4 years later. 29-31

26.28 More recently, a review of longitudinal data from The Canadian National Longitudinal Survey of Children and Youth found that approximately 7% of children show persistently high levels of parental hyperactivity from two years of age to the first grades of primary schools. 29 Maternal smoking during the prenatal period, maternal depression, poor parenting practices, and living in a disadvantaged neighborhood in the early years of life are all associated with later childhood behavior problems, including inattention and hyperactivity 4 years later. 29-31

Clinical detection and treatment of ADHD in North America may vary geographically, presumably reflecting differences in community practices or access to services. 32-34 Treatment of symptoms of inattention and hyperactivity with stimulant drugs has increased in frequency since the early to mid-1990s and likely reflects longer periods of use with continued treatment into adolescence, as well as an increase in the number of girls diagnosed and treated disease. 35-38

35-38

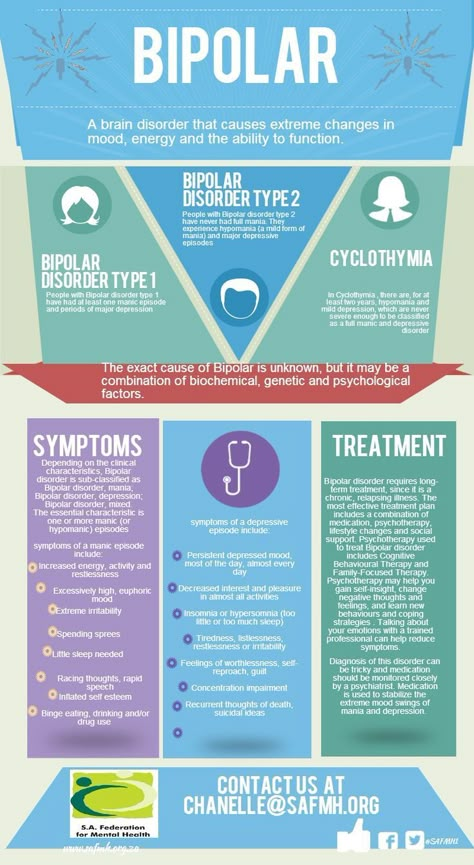

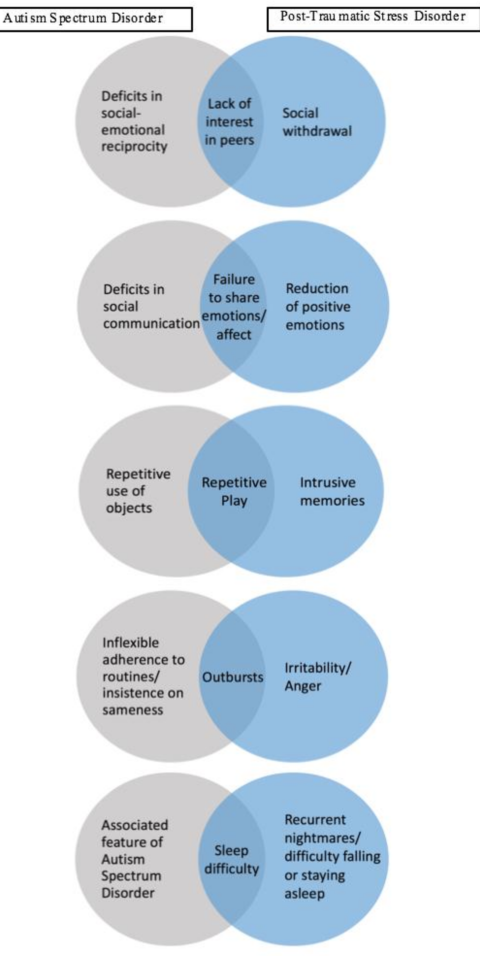

Comorbid (or comorbid) disorders

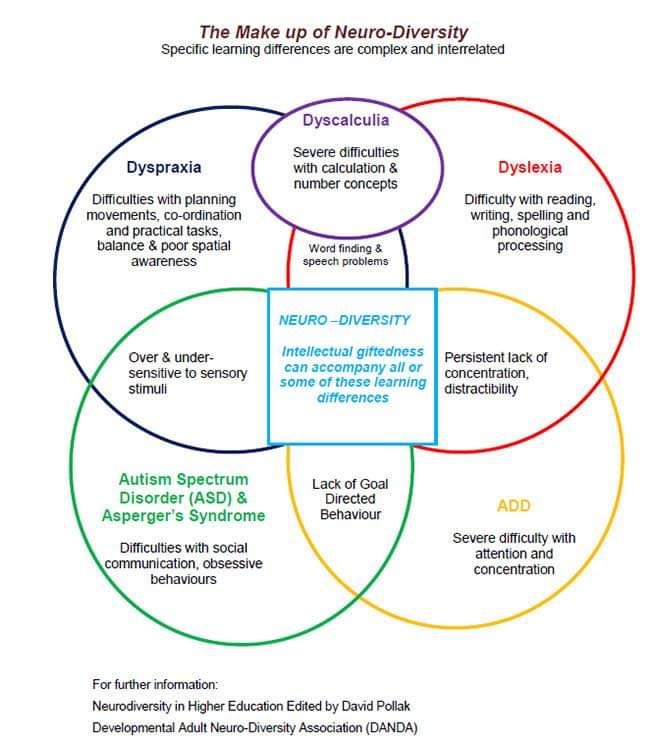

Half to two-thirds of children diagnosed with ADHD also have comorbid psychiatric and developmental disorders, including rebelliousness and aggressive behavior, anxiety, low self-esteem, tic disorders, disorders motility, learning disabilities and speech disorders. 39-46 Sleep problems, including enuresis (bedwetting), are common, along with disturbed sleep breathing, which is a potentially modifiable cause for increased inattention. 47.48 The global decline in well-being in children with ADHD increases with the number of comorbidities. 13.49 Concomitant diagnoses also increase the likelihood of additional difficulties for children as they progress into adolescence and adulthood. 10,15,16,50-55

Neurocognitive difficulties are an important source of deterioration in well-being in children with ADHD. Areas of executive functioning and working memory, as well as specific speech and learning disorders, are common in the clinical group. 56.57-64 Approximately one third of children referred for psychiatric, often behavioral, problems may have previously undiagnosed speech problems. 65 Potential cognitive problems should be diagnosed whenever possible to ensure appropriate correction in educational settings.

56.57-64 Approximately one third of children referred for psychiatric, often behavioral, problems may have previously undiagnosed speech problems. 65 Potential cognitive problems should be diagnosed whenever possible to ensure appropriate correction in educational settings.

ADHD in preschool children

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) usually begins before the child enters school. However, in preschool children, ADHD is characterized not only by attention deficits, excessive impulsivity, and hyperactivity, but is often accompanied by violent outbursts of anger, demanding, confrontational behavior, and aggressiveness, which can interfere with attendance at daycare centers or lead to avoidance of family gatherings, and also represent a heavy burden of care for the family and contribute to distress. 66,67,68 These disruptive behaviors are often a concern for parents, many of which are 66 diagnosed as oppositional defiant disorder. Early identification of the disorder can be helpful in addressing a number of developmental issues that children with ADHD may have.

Early identification of the disorder can be helpful in addressing a number of developmental issues that children with ADHD may have.

Assessment of ADHD in school-age children

In elementary school, teachers often bring to the attention of parents their concerns about the learning style and behavioral difficulties of their children. Educators generally expect kindergarten and first grade children to be able to follow classroom routines, follow simple directions, play cooperatively with peers, and stay focused for 15 to 20 minutes during classwork. The issues raised by educators, especially experienced educators, are a source of important information about the child's academic and social functioning.

The formal diagnosis of ADHD reflects pervasive and damaging levels of inattention, distractibility, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. The child's symptoms should be beyond the normal age range and cause impairment of functioning, most commonly in academic or social skills, relationships with peers, and family. Difficulties are usually present in the preschool years, although they are not always diagnosed. The harassing behavior recurs in more than one context - in the family, at school, or in public places, such as on a trip to the park or at the grocery store.

Difficulties are usually present in the preschool years, although they are not always diagnosed. The harassing behavior recurs in more than one context - in the family, at school, or in public places, such as on a trip to the park or at the grocery store.

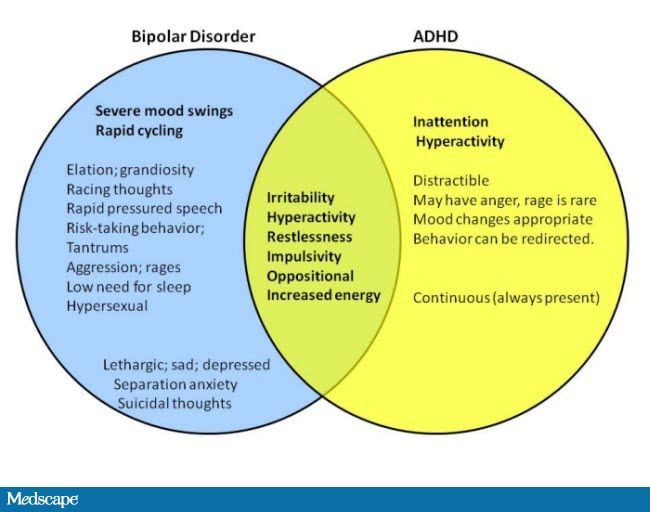

There are two sets of formal diagnostic rules used in Canada, DSM IV TR (Diagnostic and Stratistical Manual, Fourth Edition, Text Revised; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Revised) and ICD-10 (International Classification of Disorders , Tenth Edition; International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition). The DSM IV diagnosis of attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) largely reflects the consensus understanding of the diagnosis in the United States. There are three types of ADHD (see Table 1 for diagnostic symptoms).

Type I - predominantly inattentive type, the child exhibits 6 of the 9 symptoms of inattention described;

Type II - predominantly hyperactive-impulsive type, the child has 6 out of 9 hyperactive-impulsive symptoms;

type III - combined type, where the child shows high levels of development of symptoms of both types (see diagnostic symptoms in Table 1).

The ICD-10 diagnosis of hyperkinetic disorder is most commonly used by physicians who practice outside of North America. The theoretical underpinnings of ADHD and hyperkinetic disorder overlap to a large extent: the MCD-10 diagnosis of hyperkinetic disorder covers a narrower group of children who must meet both criteria - both hyperactivity and inattention and distractibility. However, when considering aspects of the overall clinical picture, children with ADHD, especially of the combined type, show similar impairments in functioning and need intervention in the same way as children with hyperkinetic disorder. 69

Clinical diagnosis of a child with ADHD is best done by professionals trained in child mental health and psychosocial development tests. Because young children often respond to stressful situations with increased levels of activity and distractibility, and have learning and social difficulties, identification of alternative explanations for these complicating symptoms requires diagnostic evaluation of the child's age, family, and social contexts. Physical symptoms such as poor sleep or chronic illness should also be considered as potential causes or contributing factors to a child's difficulty. Ideally, the doctor should obtain information about the child's social and school life from more than one informant who has the opportunity to observe him in various situations, for example, this may be the child's parent and his teacher. Self-report surveys of parents and educators are widely used to obtain information about the behavior of a particular child at home or in the school environment, respectively. 4 In addition, it is essential to conduct detailed clinical interviews with parents of young children and, for older children, with the child or adolescent himself. Reviewing school records over several years is also useful for getting a longitudinal view of a child from multiple educators. The identification of comorbid disorders is one of the important aspects of the diagnostic evaluation, including the learning and speech disorders discussed in the last section.

Physical symptoms such as poor sleep or chronic illness should also be considered as potential causes or contributing factors to a child's difficulty. Ideally, the doctor should obtain information about the child's social and school life from more than one informant who has the opportunity to observe him in various situations, for example, this may be the child's parent and his teacher. Self-report surveys of parents and educators are widely used to obtain information about the behavior of a particular child at home or in the school environment, respectively. 4 In addition, it is essential to conduct detailed clinical interviews with parents of young children and, for older children, with the child or adolescent himself. Reviewing school records over several years is also useful for getting a longitudinal view of a child from multiple educators. The identification of comorbid disorders is one of the important aspects of the diagnostic evaluation, including the learning and speech disorders discussed in the last section. In addition, psychosocial problems and age-related difficulties should be identified, as they can complicate the treatment of ADHD and affect the long-term prognosis.

In addition, psychosocial problems and age-related difficulties should be identified, as they can complicate the treatment of ADHD and affect the long-term prognosis.

Table 1: DSM IV TR Criteria for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

A. Choice of option (1) or (2):

(1) Six or more of the following symptoms persist during inattention6 months, are expressed to the degree of inadequacy and do not correspond to the age level:

Inattention

- often does not pay close attention to details or makes careless mistakes

- often has difficulty maintaining attention during tasks or play activities

- often the child does not seem to listen when spoken to directly

- often unable to follow directions and complete lessons, homework, or chores (not due to disobedience or failure to understand directions)

- often has difficulty organizing assignments and other activities

- often avoids, dislikes, or does not want to participate in tasks that require prolonged mental effort

- often loses things needed at school and at home (eg toys, school supplies, pencils, books, work tools)

- easily distracted by extraneous stimuli

- forgetful in everyday situations

(2) Six or more of the following symptoms of hyperactivity and impulsivity persist for 6 months, are expressed to the degree of inadequacy and do not correspond to the age norm:

Hyperactivity

- often there are restless movements in the hands and feet, fidgeting in a chair

- often gets up from his seat in the classroom during lessons or other situations in which you need to stay still.

- often runs or climbs things beyond measure in situations where this is unacceptable

- cannot play quietly and engage in leisure activities

- is often in constant motion or behaves as if "it has a motor attached to it"

- often talkative

Impulsivity

- often answers questions without thinking or listening to the end

- usually has difficulty waiting in line

- often interferes with or pesters others (for example, interferes in conversations or games)

B. Some symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity or inattention that worsen well-being were present in a child under 7 years of age.

C. Problems associated with these symptoms occur in two or more areas of life (e.g., school and home)

D. There must be clear evidence of clinically significant impairment in social life, academic activities, or studies associated with acquiring a profession.

E. Symptoms do not completely overlap with pervasive developmental disorder, schizophrenia, or other psychotic disorder, and cannot be explained by other mental disorders (eg, mood disorder, anxiety disorder, dissociative disorder, or personality disorder).

Literature

- Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, Biederman J, Rohde LA. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry 2007;164(6):942-948.

- Waddell C, Offord DR, Shepherd CA, Hua JM, McEwan K. Child psychiatric epidemiology and Canadian public policy-making: the state of the science and the art of the possible. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2002;47(9):825-832.

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/ Hyperactivity Disorder and Committee on Quality Improvement. Clinical practice guideline: treatment of the school-aged child with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Pediatrics 2001;108(4):1033-1044.

Pediatrics 2001;108(4):1033-1044. - Pliszka S, AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2007;46(7):894-921.

- Bruce B, Kirkland S, Waschbusch D. The relationship between childhood behavioral disorders and unintentional injury events. Pediatrics & Child Health 2007;12(9):749-754.

- Leibson CL, Katusic SK, Barbaresi WJ, Ransom J, O'Brien PC. Use and costs of medical care for children and adolescents with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. JAMA-Journal of the American Medical Association 2001;285(1):60-66.

- Brassett-Harknett A, Butler N. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an overview of the etiology and a review of the literature relating to the correlates and lifecourse outcomes for men and women.

Clinical Psychology Review 2007;27(2):188-210.

Clinical Psychology Review 2007;27(2):188-210. - Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Mick E. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiology. Journal of Pediatric Psychology 2007;32(6):631-642.

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock C, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria III. Mother-child interactions, family conflicts and maternal psychopathology. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1991;32(2):233-255.

- Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock CS, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: I. An 8-year prospective follow-up study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1990;29(4):546-557.

- Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, Guite J, Mick E, Chen L, Mennin D, Marrs A, Ouellette C, Moore P, Spencer T, Norman D, Wilens T, Kraus I, Perrin J. A prospective 4- year follow-up study of attention-deficit hyperactivity and related disorders.

Archives of General Psychiatry 1996;53(5):437-446.

Archives of General Psychiatry 1996;53(5):437-446. - Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Konig PH, Giampino TL. Hyperactive boys almost grown up. IV. Criminality and its relationship to psychiatric status. Archives of General Psychiatry 1989;46(12):1073-1079.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Early onset cannabis use and psychosocial adjustment in young adults. Addiction 1997;92(3):279-296.

- Barkley RA, Guevremont DC, Anastopoulos AD, DuPaul GJ, Shelton TL. Driving-related risks and outcomes of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in adolescents and young adults: a 3- to 5-year follow-up survey. Pediatrics 1993;92(2):212-218.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Ridder EM. Show me the child at seven: the consequences of conduct problems in childhood for psychosocial functioning in adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2005;46(8):837-849.

- Copeland WE, Miller-Johnson S, Keeler G, Angold A, Costello EJ.

Childhood psychiatric disorders and young adult crime: a prospective, population-based study. American Journal of Psychiatry 2007;164(11):1668-1675.

Childhood psychiatric disorders and young adult crime: a prospective, population-based study. American Journal of Psychiatry 2007;164(11):1668-1675. - Fergusson DM, Boden JM, Horwood LJ. Exposure to single parenthood in childhood and later mental health, educational, economic, and criminal behavior outcomes. Archives of General Psychiatry 2007;64(9):1089-1095.

- Woodward LJ, Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Driving outcomes of young people with attentional difficulties in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2000;39(5):627-634.

- Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys. Educational achievement, occupational rank, and psychiatric status. Archives of General Psychiatry 1993;50(7):565-576.

- Mannuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, LaPadula M. Adult psychiatric status of hyperactive boys grown up. American Journal of Psychiatry 1998;155(4):493-498.

- Biederman J, Petty CR, Fried R, Kaiser R, Dolan CR, Schoenfeld S, Doyle AE, Seidman LJ, Faraone SV. Educational and occupational underattainment in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a controlled study. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry 2008;69(8):1217-1222.

- Birnbaum HG, Kessler RC, Lowe SW, Secnik K, Greenberg PE, Leong SA, Swensen AR. Costs of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in the US: excess costs of persons with ADHD and their family members in 2000. Current Medical Research & Opinion 2005;21(2):195-206.

- Leibson CL, Long KH. Economic implications of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder for healthcare systems. Pharmacoeconomics 2003;21(17):1239-1262.

- Secnik K, Swensen A, Lage MJ. Comorbidities and costs of adult patients diagnosed with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Pharmacoeconomics 2005;23(1):93-102.

- St Sauver JL, Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, Weaver AL, Jacobsen SJ.

Early life risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based cohort study. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2004;79(9):1124-1131.

Early life risk factors for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based cohort study. Mayo Clinic Proceedings 2004;79(9):1124-1131. - Szatmari P, Offord DR, Boyle MH. Correlates, associated impairments and patterns of service utilization of children with attention deficit disorder: findings from the Ontario Child Health Study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1989;30(2):205-217.

- Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, Smoller JW, Goralnick JJ, Holmgren MA, Sklar P. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry 2005;57(11):1313-1323.

- Fergusson DM, Woodward LJ, Horwood LJ. Maternal smoking during pregnancy and psychiatric adjustment in late adolescence. Archives of General Psychiatry 1998;55(8):721-727.

- Romano E, Tremblay RE, Farhat A, Cote S. Development and prediction of hyperactive symptoms from 2 to 7 years in a population-based sample.

Pediatrics 2006;117(6):2101-2110.

Pediatrics 2006;117(6):2101-2110. - Elgar FJ, Curtis LJ, McGrath PJ, Waschbusch DA, Stewart SH. Antecedent-consequence conditions in maternal mood and child adjustment: a four-year cross-lagged study. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology 2003;32(3):362-374.

- Kohen DE, Brooks-Gunn J, Leventhal T, Hertzman C. Neighborhood income and physical and social disorder in Canada: associations with young children's competencies. Child Development 2002;73(6):1844-1860.

- Brownell MD, Yogendran MS. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in Manitoba children: medical diagnosis and psychostimulant treatment rates. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2001;46(3):264-272.

- Rappley MD, Gardiner JC, Jetton JR, Houang RT. The use of methylphenidate in Michigan. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 1995;149(6):675-679.

- Jensen PS, Kettle L, Roper MT, Sloan MT, Dulcan MK, Hoven C, Bird HR, Bauermeister JJ, Payne JD.

Are stimulants overprescribed? Treatment of ADHD in four U.S. communities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1999;38(7):797-804.

Are stimulants overprescribed? Treatment of ADHD in four U.S. communities. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1999;38(7):797-804. - Charach A, Cao H, Schachar R, To T. Correlates of methylphenidate use in Canadian children: a cross-sectional study. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2006;51(1):17-26.

- Miller AR, Lalonde CE, McGrail KM, Armstrong RW. Prescription of methylphenidate to children and youth, 1990-1996. CMAJ ̶ Canadian Medical Association Journal 2001;165(11):1489-1494.

- Robison LM, Sclar DA, Skaer TL, Galin RS. National trends in the prevalence of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the prescribing of methylphenidate among school-age children: 1990-1995. Clinical Pediatrics 1999;38(4):209-217.

- Safer DJ, Zito JM, Fine EM. Increased methylphenidate usage for attention deficit disorder in the 1990s. Pediatrics 1996;98(6 Pt 1):1084-1088.

- Fliers E, Vermeulen S, Rijsdijk F, Altink M, Buschgens C, Rommelse N, Faraone S, Sergeant J, Buitelaar J, Franke B. ADHD and Poor Motor Performance From a Family Genetic Perspective. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2009;48(1):25-34.

- Drabick D, Gadow K, Sprafkin J. Co-occurrence of conduct disorder and depression in a clinic-based sample of boys with ADHD. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2006;47(8):766-774.

- Baeyens D, Roeyers H, Van Erdeghem S, Hoebeke P, Vande Walle J. The prevalence of attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder in children with nonmonosymptomatic nocturnal enuresis: a 4-year followup study. Journal of Urology 2007;178(6):2616-2620.

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1999;40(1):57-87.

- Corkum P, Moldofsky H, Hogg-Johnson S, Humphries T, Tannock R. Sleep problems in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: impact of subtype, comorbidity, and stimulant medication.

Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1999;38(10):1285-1293.

Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1999;38(10):1285-1293. - Kadesjo B, Gillberg C. The comorbidity of ADHD in the general population of Swedish school-age children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2001;42(4):487-492.

- Shreeram S, He JP, Kalaydjian A, Brothers S, Merikangas KR. Prevalence of enuresis and its association with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder among U.S. children: results from a nationally representative study. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2009;48(1):35-41.

- Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry 1991;148(5):564-77.

- Corkum P, Tannock R, Moldofsky H. Sleep disturbances in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1998;37(6):637-646.

- Owens JA, Maxim R, Nobile C, McGuinn M, Msall M. Parental and self-report of sleep in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2000;154(6):549-555.

- Biederman J, Milberger S, Faraone SV, Kiely K, Guite J, Mick E, Ablon JS, Warburton R, Reed E, Davis SG. Impact of adversity on functioning and comorbidity in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1995;34(11):1495-1503.

- Fischer M, Barkley RA, Edelbrock CS, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria: II. Academic, attentional, and neuropsychological status. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology 1990;58(5):580-588.

- Fischer M, Barkley RA, Fletcher KE, Smallish L. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children: predictors of psychiatric, academic, social, and emotional adjustment.

Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1993;32(2):324-332.

Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1993;32(2):324-332. - Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ. Early conduct problems and later life opportunities. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1998;39(8):1097-1108.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. The effects of unemployment on psychiatric illness during young adulthood. Psychological Medicine 1997;27(2):371-381.

- Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Mick E, Spencer T, Wilens TE, Klein KL, Price JE, Faraone SV. Psychopathology in females with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a controlled, five-year prospective study. Biological Psychiatry 2006;60(10):1098-1105.

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Federman E, Angold A. Development of psychiatric comorbidity with substance abuse in adolescents: effects of timing and sex. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology 1999;28(3):298-311.

- Solanto MV, Gilbert SN, Raj A, Zhu J, Pope-Boyd S, Stepak B, Vail L, Newcorn JH.

Neurocognitive functioning in AD/HD, predominantly inattentive and combined subtypes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2007;35(5):729-744.

Neurocognitive functioning in AD/HD, predominantly inattentive and combined subtypes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2007;35(5):729-744. - Hinshaw SP, Carte ET, Fan C, Jassy JS, Owens EB. Neuropsychological functioning of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder followed prospectively into adolescence: evidence for continuing deficits? Neuropsychology 2007;21(2):263-273.

- Thorell LB, Wahlstedt C. Executive functioning deficits in relation to symptoms of ADHD and/or ODD in preschool children. Infant and Child Development 2006;15(5):503-518.

- Loo SK, Humphrey LA, Tapio T, Moilanen IK, McGough JJ, McCracken JT, Yang MH, Dang J, Taanila A, Ebeling H, Jarvelin MR, Smalley SL.. Executive functioning among Finnish adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder . Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2007;46(12):1594-1604.

- Barkley RA, Edwards G, Laneri M, Fletcher K, Metevia L.

Executive functioning, temporal discounting, and sense of time in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2001;29(6):541-556.

Executive functioning, temporal discounting, and sense of time in adolescents with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and oppositional defiant disorder (ODD). Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2001;29(6):541-556. - Beitchman JH, Brownlie EB, Inglis A, Wild J, Ferguson B, Schachter D, Lancee W, Wilson B, Mathews R. Seven-year follow-up of speech/language impaired and control children: psychiatric outcome. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 1996;37(8):961-970.

- Clark C, Prior M, Kinsella G. The relationship between executive function abilities, adaptive behavior, and academic achievement in children with externalising behavior problems. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2002;43(6):785-796.

- Calhoun SL, Dickerson Mayes S. Processing speed in children with clinical disorders. Psychology in the Schools 2005; 42(4):333-343 .

- Rabiner D, Coie JD, Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group.

Early attention problems and children's reading achievement: a longitudinal investigation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2000;39(7):859-867.

Early attention problems and children's reading achievement: a longitudinal investigation. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 2000;39(7):859-867. - Cohen NJ, Davine M, Horodezky N, Lipsett L, Isaacson L. Unsuspected language impairment in psychiatrically disturbed children: prevalence and language and behavioral characteristics. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 1993;32(3):595-603.

- Cunningham CE, Boyle MH. Preschoolers at risk for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and oppositional defiant disorder: family, parenting, and behavioral correlates. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2002;30(6):555-569.

- Keown LJ, Woodward LJ. Early parent-child relations and family functioning of preschool boys with pervasive hyperactivity. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 2002;30(6):541-553.

- Greenhill LL, Posner K, Vaughan BS, Kratochvil CJ. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in preschool children.

Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 2008;17(2):347-366.

Child & Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America 2008;17(2):347-366. - Lee SI, Schachar RJ, Chen SX, Ornstein TJ, Charach A, Barr C, Ickowicz A. Predictive validity of DSM-IV and ICD-10 criteria for ADHD and hyperkinetic disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 2008;49(1):70-78.

Note:

a American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders Text Revision (DSM-IV-TR) . 4th Ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc., 2000.

For citation:

Charach E. Children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: epidemiology, comorbidity and diagnosis. In: Tremblay RE, Buavan M, Peters RDeV, eds. Shakhar R, eds. Topics. Encyclopedia of Early Childhood Development [online]. https://www.encyclopedia-deti.com/giperaktivnost-i-nevnimatelnost-sdvg/ot-ekspertov/deti-s-sindromom-deficita-vnimaniya-i. Published: March 2010 (English). Viewed on October 21, 2022

Published: March 2010 (English). Viewed on October 21, 2022

Text copied to clipboard ✓

ADHD: a diagnosis in doubt

Photo from annakennedyonline.comIn fact, if other forms of developmental disorders, such as autism, have a fairly pronounced specificity, which becomes more pronounced as the baby grows up, then ADHD may not cause particular concern to parents until the child starts school. And even then, adults often refuse to see anything more than restlessness, and hope that in another year or two, he will “outgrow” children's problems.

On the other hand, awareness of the syndrome causes some parents to suspect a disorder in their son or daughter at the slightest sign of inattention or increased activity, to become anxious and, in turn, increase anxiety in the child.

ADHD is also the subject of fierce debate among medical experts and psychologists. Since the 70s of the last century, some experts have diagnosed children with this disease, others claim that it is not a disease, that ADHD was “invented, but not proven”, and its manifestations are not abnormal, they can be explained by the influence of the environment or a personality trait the person to whom the "disorder" is attributed.

The well-known American journalist and former psychotherapist Tom Hartman, whose son was diagnosed with ADHD, even came up with an interesting hypothesis called the “hunter and farmer theory”. According to Hartman, since man during the first millennia of his history was a nomadic hunter or gatherer, hyperactivity and impulsivity, as well as focused attention on one object and neglect of other details, were favorable adaptive qualities from an evolutionary point of view.

Then, with the development of agriculture, this standard gradually changed, humanity as a whole adapted to a settled way of life and the routine production of food and other material goods, requiring long-term and distributed attention. People with ADHD, on the other hand, retained some of the traits of hunters. Hartman proposed to consider "hyperfocus" (the ability to pay particularly intense attention to an object of interest while paying little attention to everything else) as a gift or advantage of people with the syndrome, and a number of other characteristics, such as disregard for social norms, poor organizational skills, reduced ability to plan, violations of the sense of time, impulsiveness and impatience - as features associated with the type of personality of the hunter.

Interestingly, the American anthropologist Ben Campbell studied the nomadic people of Ariaal in Kenya and found that their representatives are very characterized by hyperactivity and impulsivity, which do not interfere at all, but, on the contrary, help to better adapt to their lifestyle.

The diagnosis is also criticized based on the fact that there are no solid biological markers of the disorder, and there is no unambiguous treatment leading to recovery.

Supporters of the allocation of ADHD as an independent diagnosis are based on the presence of a certain set of symptoms, which, with a certain degree of severity, lead to partial maladaptation of the patient, while maladjustment indicates the presence of a disorder.

To date, the victory belongs to the latter: in the international classifier of diseases ICD-10, there is such a diagnosis. According to a systematic study of the literature conducted in 2007, the prevalence of ADHD in the world was 5.29%. Girls are diagnosed with ADHD on average 3-4 times less often than boys.

Girls are diagnosed with ADHD on average 3-4 times less often than boys.

Russian data are striking in their colossal scatter: according to various estimates, from 2% to 47% of the child population of our country suffer from this disorder, and this indicates that, unfortunately, competent epidemiological studies have not been conducted in our country. There is reason to believe that the most likely prevalence in the Russian Federation is approximately at the same level as in other developed countries.

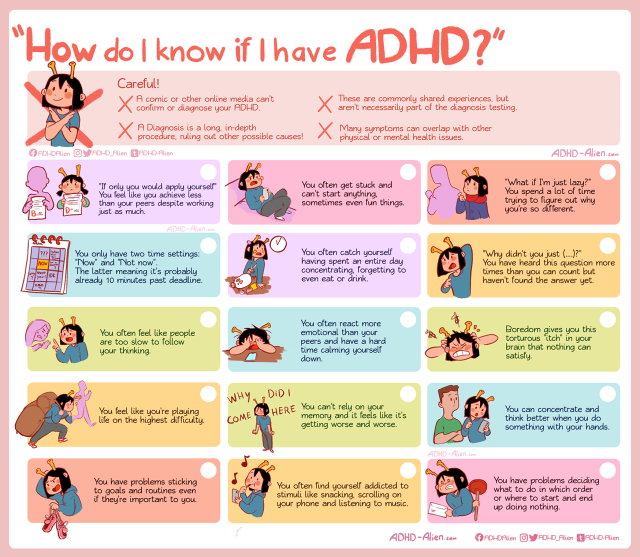

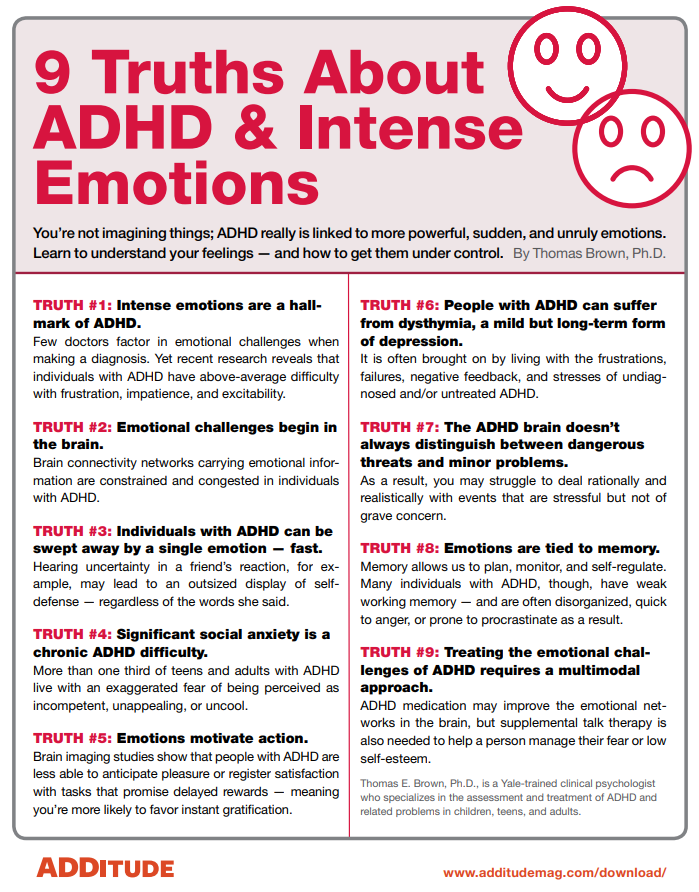

It is characterized by a triad of signs: impaired attention, hyperactivity and impulsivity.

Impaired attention manifests itself in the fact that the child is unable to concentrate on details, is constantly distracted, makes mistakes in school assignments that show carelessness rather than lack of logic and ability to think operations in accordance with age. The preschooler has difficulty maintaining attention during the game. Often one gets the impression that he does not listen to the speech addressed to him.

Sometimes it may seem that the child does not understand instructions, tasks, because he is not able to carry them out from beginning to end, but in fact the problem is not in the weakness of thinking, but in the impossibility for him to concentrate for any long time.

The child may be fiercely resistant to tasks that require prolonged mental exertion, whether it is a math problem or putting things in order in the room, but it is not a matter of negativity or protest behavior: it is actually very difficult for him and therefore requires more willpower than which is in line with his age.

By the way: ADHD is not only in children, but an adult is usually able to overcome difficulties with concentration, so others may not notice his problems.

Inattention leads to the fact that the child often loses things (toys, school supplies, mittens, removable shoes), forgets a diary, notebooks, textbooks at home.

Hyperactivity manifests itself in the inability of the child to quiet, calm activities. Sitting at a lesson or at home while doing homework, he constantly spins, gets up even in situations where he is supposed to stay still, and shows aimless motor activity. Often he tries to climb somewhere, puts himself at risk, not being able to correctly assess the consequences of his actions.

Sitting at a lesson or at home while doing homework, he constantly spins, gets up even in situations where he is supposed to stay still, and shows aimless motor activity. Often he tries to climb somewhere, puts himself at risk, not being able to correctly assess the consequences of his actions.

Some of the hyperactive children are distinguished by the fact that they never remain silent, their verbal flow is very difficult to stop, and this becomes especially noticeable at school, where the classroom system assumes that the student speaks out only at the request of the teacher.

The third criterion of the syndrome is impulsiveness . The child answers the question without thinking, often without even listening to it. It is difficult for him to stand in line. He often interferes in conversations or games, pesters others with conversations. He commits risky acts under the influence of a sudden impulse, not having time to think about the dangerous consequences, more often than others he gets injured and damages his or someone else's property.

It should be noted that the syndrome can occur with predominant attention disorders without hyperactivity and impulsivity, and vice versa, hyperactivity and impulsivity can be the leading symptoms with mild attention impairment. But in one form or another, it always creates difficulties with the child's adaptation to school life, both in terms of academic performance and in terms of relationships with classmates.

The diagnosis of ADHD can be made starting in late preschool or early school age, as this requires an assessment of the child's behavior in at least two settings (eg, home and school) as well as marked learning and social impairments.

Despite the fact that attention deficit hyperactivity disorder is a recognized diagnosis, specialists, parents, teachers in many countries note the problem of subjectivity in the diagnosis, and in connection with this - overdiagnosis, or, conversely, underdiagnosis of ADHD. Both are dangerous: drug treatment of a healthy, but somewhat restless child will only bring harm, but a child with a real disorder who does not receive adequate help (not necessarily medication) also suffers.

It is not uncommon to hear parents complaining about teachers: not being able to establish discipline in the classroom, keep the children's attention with a vivid presentation of educational material, motivate them to work independently, teachers demand that the parents of an underachieving student take measures, up to a medical examination and appropriate treatment.

Here are some interesting statistics for 2005: 82% of educators in the US believe that ADHD is overdiagnosed, while only 3% believe it is underdiagnosed; but in China only 19% of teachers considered diagnosing ADHD excessive, but 57% believe that many children have ADHD undiagnosed.

American teachers have turned out to be on the side of the children and are in no hurry to explain their school problems as medical, while Chinese teachers are the opposite. It is difficult to say whether the fact is that in the United States there really is overdiagnosis, while in China the problem is the opposite, or everything is explained by the specific attitude of teachers in the two countries towards their wards. One way or another, it would be very interesting to look at the results of such a survey in Russian kindergartens and schools.

One way or another, it would be very interesting to look at the results of such a survey in Russian kindergartens and schools.

Like any developmental disorder, ADHD has a biological basis, but what it consists of, what variants of physical ill health lead to the syndrome, is still not completely clear. The exception is the residual form of ADHD, when the disorder occurs as a result of a physical injury to the brain.

It is believed that ADHD in a child can be caused by complications during pregnancy in the mother or childbirth, as well as diseases such as asthma, recurring pneumonia, kidney disease, allergies, therefore, when making a diagnosis of ADHD, a comprehensive medical examination and treatment should be carried out identified disorders, which can lead to a reduction in symptoms of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

There is evidence of a genetic predisposition to ADHD, but so far there is no clear understanding of which gene mutations are responsible for the occurrence of the syndrome.

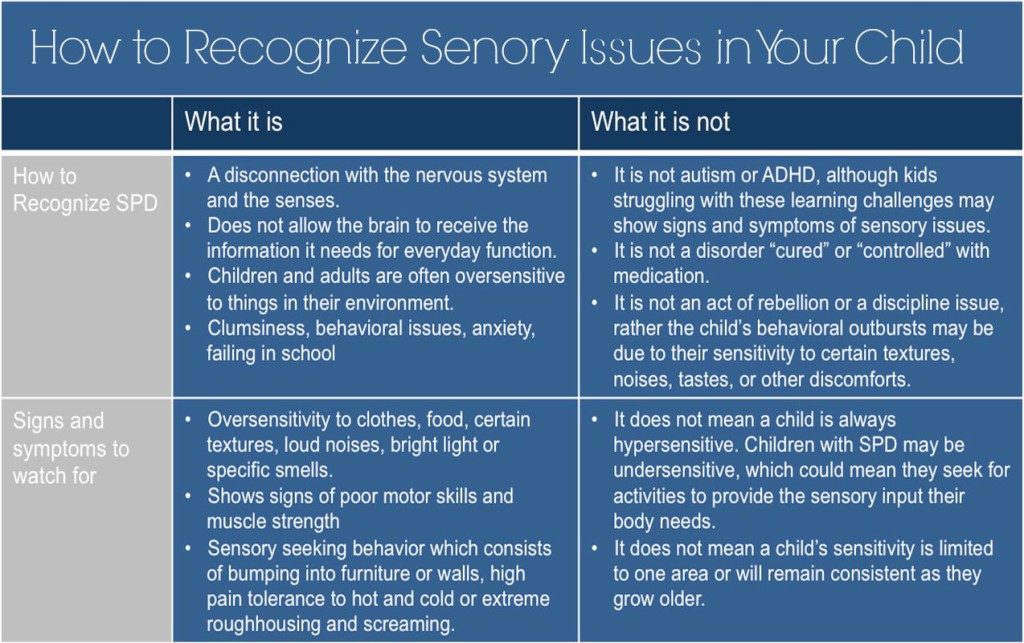

More recently, scientists have singled out impaired sensory impulse processing (SPP) as an independent disorder. A child (or adult) may have excellent vision, but the visual signal is not processed properly by the brain, and he will not always automatically take a step to the side if he sees that a large object is moving towards him.

The child may be clumsy and poorly coordinated because sensory inputs to the brain from the vestibular and tactile systems, muscles and joints (which are also deeply sensitive) are not correctly processed by the central nervous system, which in turn generates inadequate motor answer.

Normally, our brain forms a holistic view of what is in the field of our perception, integrating the signals coming from all sensory analyzers simultaneously. If this does not happen, then even an adult has to strain his attention more, and he gets tired faster. A child with sensory problems, on the other hand, requires an extraordinary effort to concentrate and complete a task, and this may be the reason for his inability to concentrate for a long time.