Depression from social anxiety

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

SAMHSA Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

HomeWelcome to the Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator, a confidential and anonymous source of information for persons seeking treatment facilities in the United States or U.S. Territories for substance use/addiction and/or mental health problems.

PLEASE NOTE: Your personal information and the search criteria you enter into the Locator is secure and anonymous. SAMHSA does not collect or maintain any information you provide.

Please enter a valid location.

please type your address

-

FindTreatment.

gov

gov Millions of Americans have a substance use disorder. Find a treatment facility near you.

-

988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

Call or text 988

Free and confidential support for people in distress, 24/7.

-

National Helpline

1-800-662-HELP (4357)

Treatment referral and information, 24/7.

-

Disaster Distress Helpline

1-800-985-5990

Immediate crisis counseling related to disasters, 24/7.

- Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Locator OverviewLocator Overview

- Finding Treatment

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Find Facilities for VeteransFind Facilities for Veterans

- Facility Directors

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Register a New FacilityRegister a New Facility

- Other Locator Functionalities

- Download Search ResultsDownload Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Print Search ResultsPrint Search Results

- Use Google MapsUse Google Maps

- Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). - Icon from Find practitioners and treatment programs providing buprenorphine for opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers). Find programs providing methadone for the treatment of opioid addiction (heroin or pain relievers).

The Locator is authorized by the 21st Century Cures Act (Public Law 114-255, Section 9006; 42 U.S.C. 290bb-36d). SAMHSA endeavors to keep the Locator current. All information in the Locator is updated annually from facility responses to SAMHSA’s National Substance Use and Mental Health Services Survey (N-SUMHSS). New facilities that have completed an abbreviated survey and met all the qualifications are added monthly. Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

Updates to facility names, addresses, telephone numbers, and services are made weekly for facilities informing SAMHSA of changes. Facilities may request additions or changes to their information by sending an e-mail to [email protected], by calling the BHSIS Project Office at 1-833-888-1553 (Mon-Fri 8-6 ET), or by electronic form submission using the Locator online application form (intended for additions of new facilities).

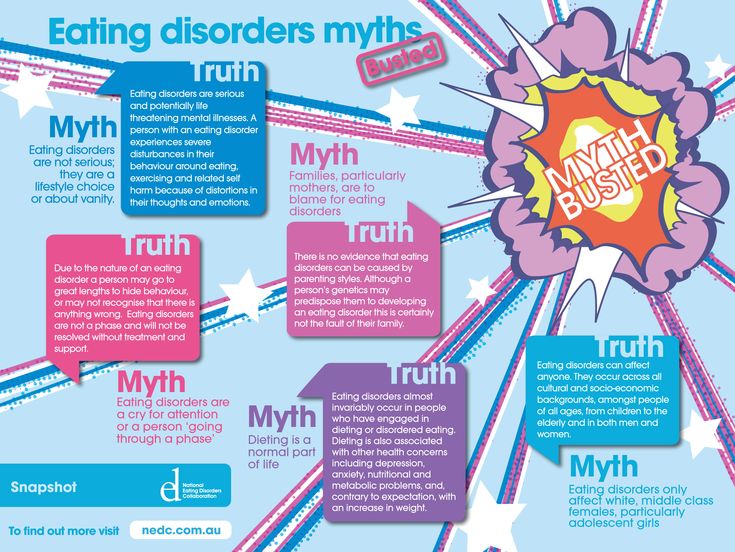

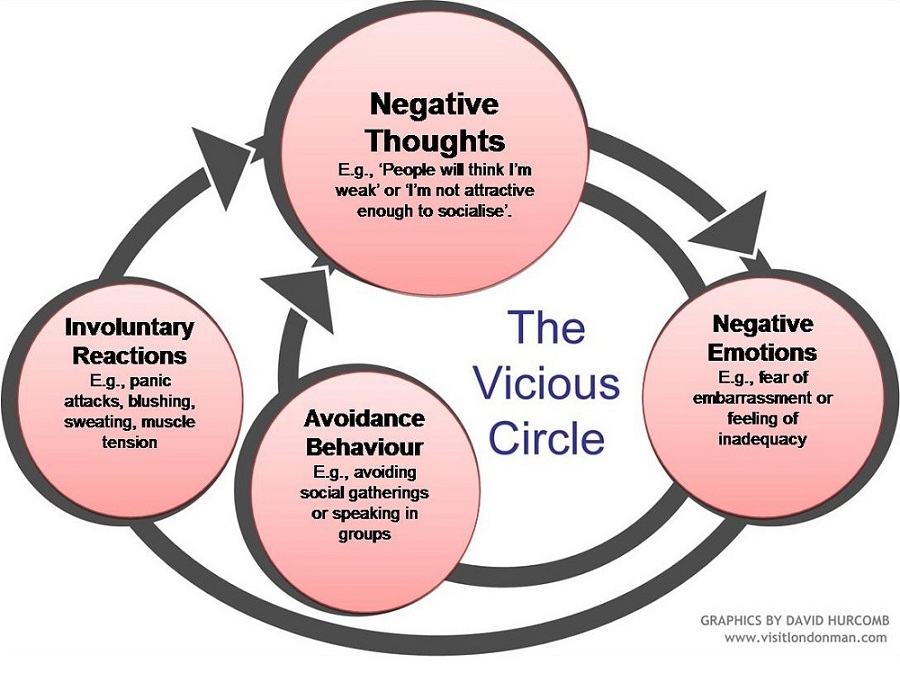

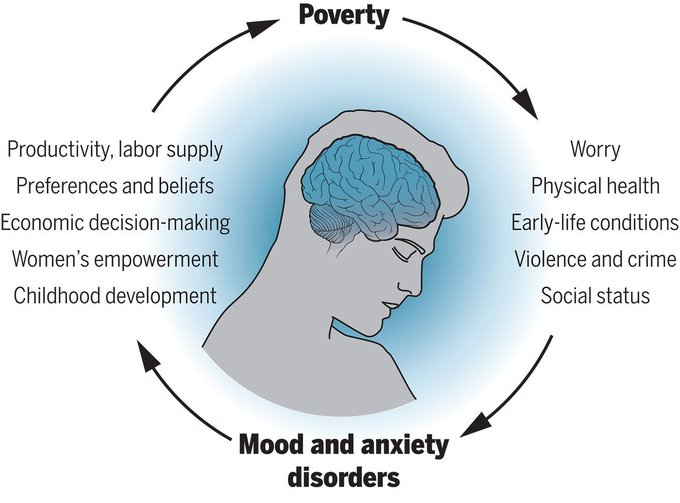

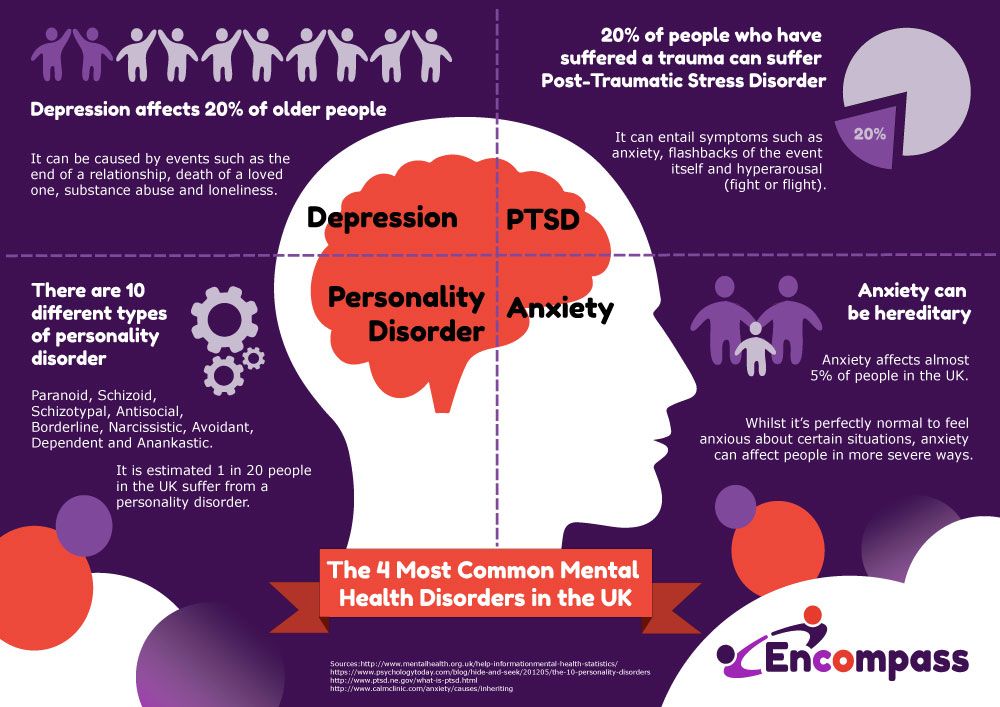

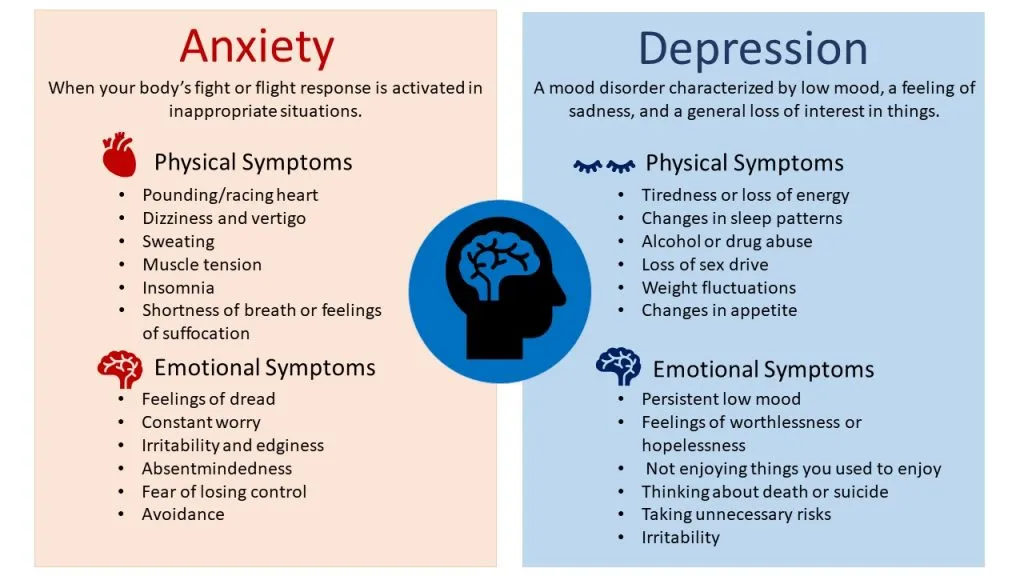

depression and anxiety are unrelated

The vast majority of people with depression are diagnosed with an anxiety disorder. A group of researchers from Novosibirsk found out that the centers of brain activity that "supervise" depression and anxiety are opposite in their actions. The results of the work will help improve the methods of differential diagnosis and treatment, according to a press release from the Russian Science Foundation. The study was published in the August issue of the journal Brain Research.

“Anxiety and depression go hand in hand in the sense that anxiety often precedes depression, sometimes they alternate, but they are qualitatively different conditions, even if they are combined in one person. There is also a kind of depression that is not associated with anxiety, but arising from anhedonia, that is, the inability to experience positive emotions, ”explains Gennady Knyazev, head of the study, head of the laboratory of differential psychophysiology at the Research Institute of Physiology and Fundamental Medicine.

There is also a kind of depression that is not associated with anxiety, but arising from anhedonia, that is, the inability to experience positive emotions, ”explains Gennady Knyazev, head of the study, head of the laboratory of differential psychophysiology at the Research Institute of Physiology and Fundamental Medicine.

Tendencies to depression and anxiety were determined in healthy people who had not previously sought help from psychotherapists and psychiatrists. The severity of depressive symptoms in 44 participants in the experiment was determined using the Beck questionnaire, in which 21 questions on the main symptoms of depression, and respondents are asked to indicate how often they experienced the corresponding state over the past two weeks. To determine anxiety, the researchers used an appropriate personality questionnaire. After identifying symptoms, participants were shown pictures of people expressing emotions—negative, neutral, or positive. Respondents recorded the preferred way of interacting with a person in the photo (befriend, ignore, attack), at the same time they took an electroencephalogram of the brain.

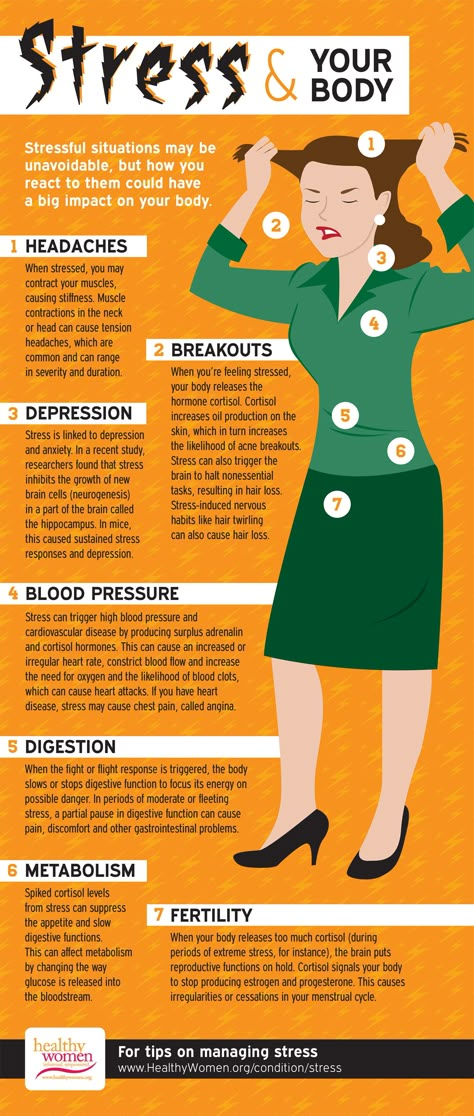

Scientists have found that the mechanisms of brain activity associated with depression and anxiety are largely opposite. Anxiety is associated with increased reactivity of the attention system, and depression is associated with reduced cognitive reactivity.

In addition, in individuals predisposed to depression, unequal compensatory activation of emotion regulation centers was found, which is necessary to ensure the required level of social interactions. It is noted that some participants in the experiment tried to ignore other people's emotions, other participants with depressive symptoms showed a negative reaction even to neutral stimuli.

It is generally accepted that the pathologies of depression and anxiety are often combined with each other, genetic studies show that the same regions of the genome are responsible for both disorders. Both pathologies were even proposed to be combined in the classifier of diseases, with which Novosibirsk scientists do not agree. Genes determine only 50% of the predisposition, the rest depends on environmental influences, explains Gennady Knyazev.

Genes determine only 50% of the predisposition, the rest depends on environmental influences, explains Gennady Knyazev.

“The emergence of psychopathology is always the interaction of genes and environment. The same stress in someone passes without a trace, and in someone it causes depression, or post-traumatic stress disorder. In the same way, the same degree of predisposition in some conditions will lead to illness, and in others to a completely happy life, ”Gennady Knyazev clarifies.

According to scientists, the data obtained may be of importance both for the development of methods for the differential diagnosis of mental pathologies, and, potentially, for the treatment of depression.

Tags

Media about the Foundation, Medicine, Special project

Temperament in early childhood and the development of anxiety and depression

Nathan A. Fox, PhD, Tahl I. Frenkel, MA

Fox, PhD, Tahl I. Frenkel, MA

University of Maryland, USA

(English). Translation: June 2015

Introduction

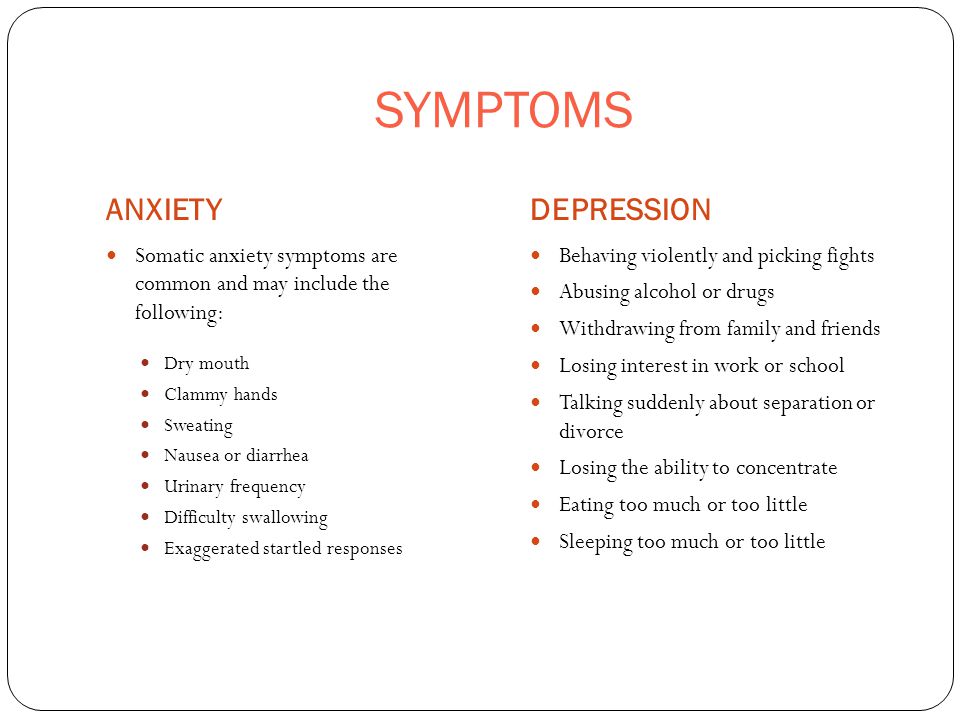

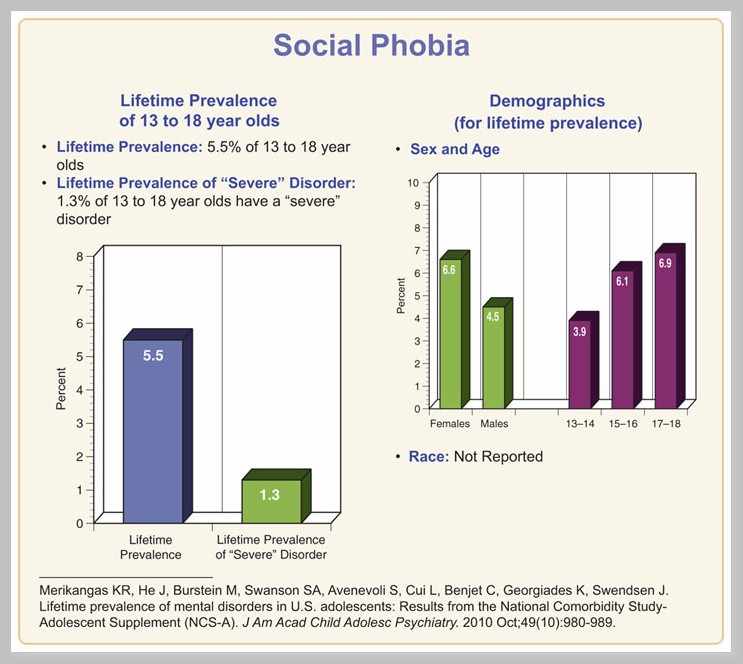

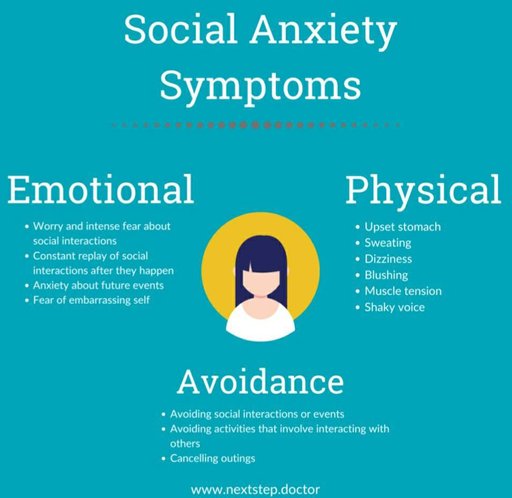

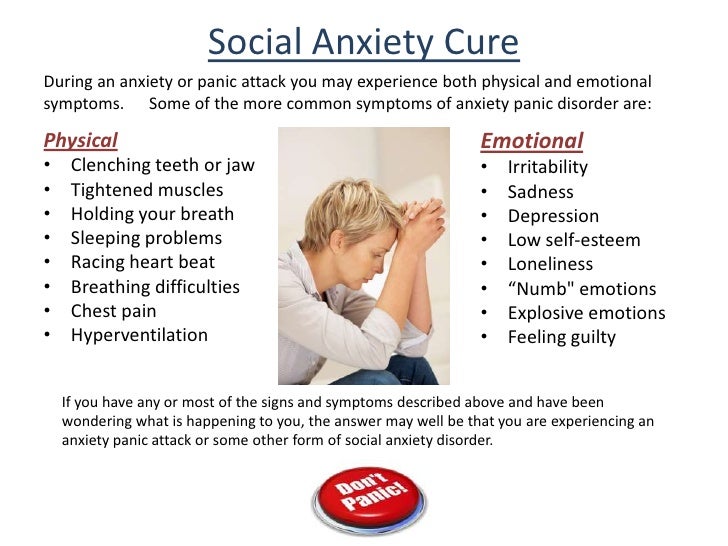

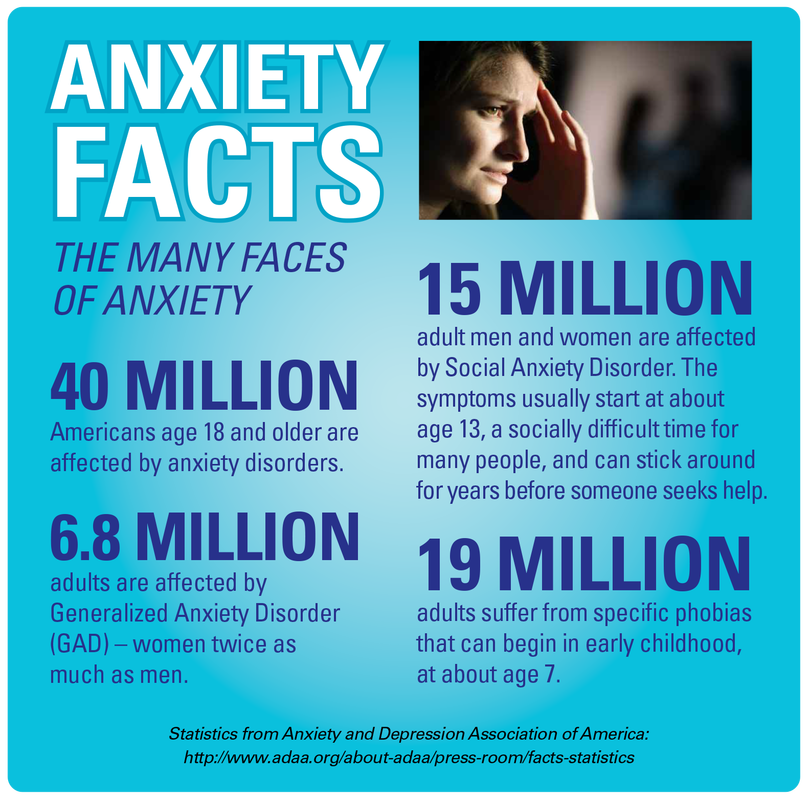

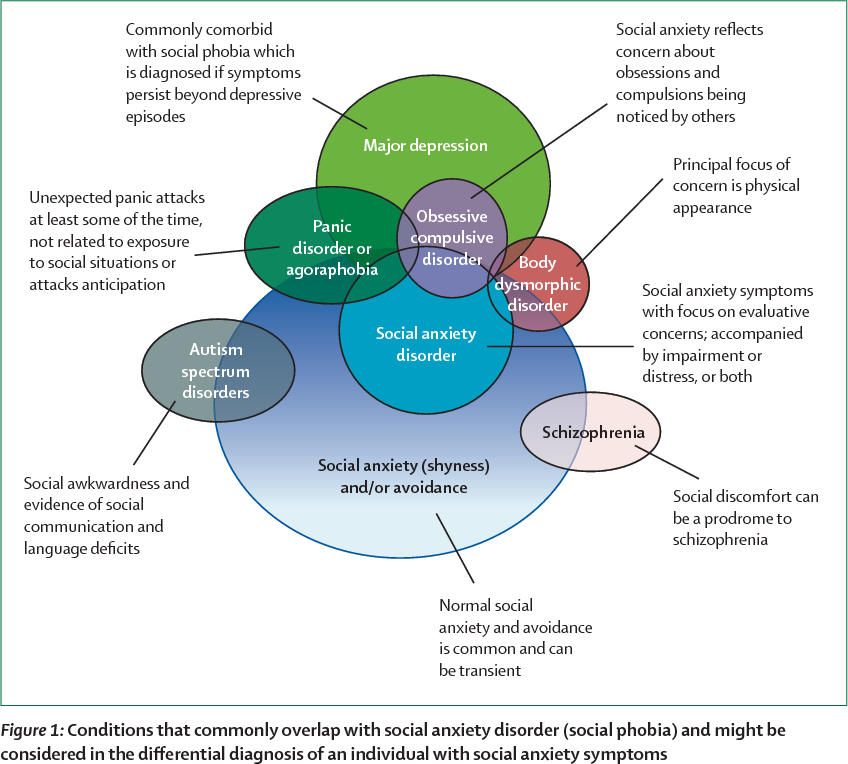

Anxiety disorders in general, and social anxiety disorder (social anxiety disorder, SAD) in particular, cause severe distress and increase the risk of long-term adverse effects. Most anxiety disorders in adults begin in childhood or adolescence at an extremely steady rate of 5 to 10 percent; and the level of social phobia varies from 1.6% to 8.5%. 2-4 Longitudinal studies show that the temperamental trait of behavioral inhibition appears to be the most likely predictor of the risk of developing anxiety later in life. 5-6

The purpose of this chapter is to explore in general terms the relationship between this temperament and the occurrence of anxiety disorders. We will review research on two cognitive processes, attention and executive processes, that contribute to anxiety disorders among children with behavioral inhibition. Finally, in line with recent evidence that behavioral inhibition may represent not only a specific temperamental predisposition to anxiety, but also a more general risk factor for internalizing disorders, 7 we will review the existing (still limited) literature linking early temperament with the subsequent development of depression.

We will review research on two cognitive processes, attention and executive processes, that contribute to anxiety disorders among children with behavioral inhibition. Finally, in line with recent evidence that behavioral inhibition may represent not only a specific temperamental predisposition to anxiety, but also a more general risk factor for internalizing disorders, 7 we will review the existing (still limited) literature linking early temperament with the subsequent development of depression.

Item

Behavioral inhibition is a type of temperament that can be identified in infancy and early childhood. Infants with this temperament show increased irritability and motor reactivity to unusual stimuli. During their early preschool years, they avoid social contact and tend to withdraw in unfamiliar social situations, which makes them less self-confident5,6 and more susceptible to peer rejection, 8,9 what is the reason for negative self-perception. 10 In general, inhibited children have fewer friends, 11 they are more likely to show increased anxiety and feel lonely. 12

10 In general, inhibited children have fewer friends, 11 they are more likely to show increased anxiety and feel lonely. 12

Anxiety risk studies focus on early temperamental traits, especially behavioral inhibition. 10,13,14 For example, Schwartz et al6 found that 61% of thirteen-year-olds who were noted to show signs of behavioral inhibition at age two showed clear signs of anxiety during social interactions, compared with only 27% of those who showed no inhibition. Similarly, Chronis-Tuscano et al. 15 found a fourfold increased likelihood of a lifetime diagnosis of social anxiety disorder among adolescents with persistently high levels of behavioral inhibition between the ages of 1 and 7 years. Data from both studies suggest that early temperament limits but does not predetermine outcomes. Only about half of inhibited children are at significant risk, and anxiety tends to wax and wane over time. 16

We argue that temperament in childhood shapes how a person perceives their environment, which reciprocally affects social interaction and possible social outcomes and mental health outcomes. 17 This dynamic is particularly evident in early adolescence, during which the emergence of a peer group with more significant developmental influence coincides with a dramatic increase in psychopathology,16 in particular social phobia. 6,15,18 Temperament also shapes vital cognitive processes such as attention and certain executive processes that underpin how children perceive and respond to social stimuli in the environment.

17 This dynamic is particularly evident in early adolescence, during which the emergence of a peer group with more significant developmental influence coincides with a dramatic increase in psychopathology,16 in particular social phobia. 6,15,18 Temperament also shapes vital cognitive processes such as attention and certain executive processes that underpin how children perceive and respond to social stimuli in the environment.

Issues

Questions concerning the functional and structural relationship between temperament and anxiety remain open. 19 Several reviews 10,17,20,21 noted a variety of behavioral and physiological similarities and differences between both temperamentally retarded and anxious individuals. If anxiety and inhibited temperament are seen as two distinct constructs, then temperament either exposes the child to the risk of developing anxiety or influences the persistence or severity of anxiety disorders once they occur. 10 On the other hand, these terms may simply refer to different aspects of the same construct, and the differences between them are then forced by opinions in the field. 21

10 On the other hand, these terms may simply refer to different aspects of the same construct, and the differences between them are then forced by opinions in the field. 21

Scientific context

It has been suggested in the scientific literature that deviations in both "upward" a attentional mechanisms and "downward" a executive control processes may play a key role in the etiology and maintenance of anxiety. 22 These disturbances extend to both emotionally charged and emotionally neutral stimuli, reflecting a prioritization of certain categories of stimuli (i.e. erroneous attitudes towards stimuli) along with increased alertness to one's own activity and behavior (i.e. cognitive monitoring) .

Anxious children 23-25 and adults 26-27 show attention bias towards threatening stimuli. Previous work has shown 28.29 that adolescents with clinically severe anxiety showed disturbances in the reaction of the amygdala b and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex c (vlPFC) to threat when performing tasks for attention distortions. Attention distortions, as such, are automatic "bottom-up" mechanisms that shape cognition and behavior. The study also implies a neural network in the prefrontal cortex that engages attention to closely follow the activity, taking into account the feedback as the person then applies more specialized executive control mechanisms to correct subsequent behavior. 30-32 Anxiety-related disorders of this pattern are evident in both children, 33 and adults. 34 Imaging studies have implicated the anterior cingulate cortex d (ACC) in this process, as it is hyperactive in anxious people during tasks that require cognitive control or "top-down" control. 35

Attention distortions, as such, are automatic "bottom-up" mechanisms that shape cognition and behavior. The study also implies a neural network in the prefrontal cortex that engages attention to closely follow the activity, taking into account the feedback as the person then applies more specialized executive control mechanisms to correct subsequent behavior. 30-32 Anxiety-related disorders of this pattern are evident in both children, 33 and adults. 34 Imaging studies have implicated the anterior cingulate cortex d (ACC) in this process, as it is hyperactive in anxious people during tasks that require cognitive control or "top-down" control. 35

Key Questions

Among typically developing children, approximately 15-20% of Caucasian children in the United States exhibit a behaviorally inhibited temperament in early childhood. Longitudinal studies have shown that about half of these behaviorally retarded children go on to develop anxiety disorders into adolescence and adulthood. A key research question in terms of early intervention is to identify the factors that lead to these different trajectories over time. That is, what factors (either in surrounding adults or in the child himself) protect against anxiety or increase the risk of developing it.

A key research question in terms of early intervention is to identify the factors that lead to these different trajectories over time. That is, what factors (either in surrounding adults or in the child himself) protect against anxiety or increase the risk of developing it.

Recent research findings

Attention distortions in relation to threat

Recent research suggests that behavioral inhibition is characterized by impaired control of attention. 36.37 Two recent longitudinal studies 18.38 examined the relationship between behavioral inhibition in childhood, attentional distortions to threatening stimuli, and propensity to withdraw from social contact. Pérez-Edgar et al 18 found that adolescents who were behaviorally retarded as children exhibited a distortion of attention towards a potential threat. In addition, threat attention bias mediated a statistical association between behavioral inhibition in childhood and propensity to withdraw from social contact during adolescence. In a separate study, Pérez-Edgar et al. 38 found that behavioral inhibition at the age of walking was predictive of high social avoidance in early childhood. Again, this relationship was statistically mediated by threat attention bias such that the relationship between behavioral inhibition and social avoidance was only noticeable in children who showed threat attention bias. These data provide support for a view that threat attention distortions are an important mediator of behavioral inhibition and the subsequent occurrence of clinical anxiety.

In a separate study, Pérez-Edgar et al. 38 found that behavioral inhibition at the age of walking was predictive of high social avoidance in early childhood. Again, this relationship was statistically mediated by threat attention bias such that the relationship between behavioral inhibition and social avoidance was only noticeable in children who showed threat attention bias. These data provide support for a view that threat attention distortions are an important mediator of behavioral inhibition and the subsequent occurrence of clinical anxiety.

Executive processes: inhibitory control and cognitive monitoring

Inhibitory control characterizes the ability to restrain and suppress dominant responses and behaviors in favor of more appropriate or subdominant responses and behaviors39. Cognitive monitoring represents the ability to pay attention to one's own activities, notice errors, and correct behavior based on feedback. It is believed that these control processes play a role in the regulation of negative emotions and in such a property of temperament as reactivity. 40-42

40-42

Several studies have shown that inhibitory control mediates the ability to predict the occurrence of anxiety behaviors based on measurements of temperamental manifestations of behavioral inhibition. Children with a high level of inhibitory control were found to be more socially anxious, 43 less socially competent and more socially withdrawn, 44 than behaviorally inhibited children with a low level of inhibitory control. Similarly, White et al. 45 found that a high level of inhibitory control increased the risk of anxiety disorders among highly behaviorally inhibited children.

In independent studies, increased cognitive monitoring has been found to be associated with increased anxiety in both adults and children. 48 McDermott et al49 found that the level of cognitive monitoring was higher in adolescents with severe childhood behavioral retardation compared with adolescents with low levels of behavioral retardation. Moreover, increased monitoring mediated early behavioral inhibition and later anxiety disorders. 49 Thus, like the distortions of attention to threatening stimuli, the executive processes of inhibitory control and cognitive monitoring act as a mediator for the child's temperament prone to an increased risk of anxiety.

Moreover, increased monitoring mediated early behavioral inhibition and later anxiety disorders. 49 Thus, like the distortions of attention to threatening stimuli, the executive processes of inhibitory control and cognitive monitoring act as a mediator for the child's temperament prone to an increased risk of anxiety.

Unexplored areas

Age changes result from the interaction between the child's innate characteristics and environmental context, making the child both creator and product of the environment. 50 Behavioral inhibition may prompt the child to go in one of a number of directions, and the expected outcome may be the result of multiple provocative paths. 10 Research thus needs to explain the operation of a number of mediating factors that may come into play at various points during development. So far, there are very few studies analyzing the discontinuous nature of behavioral retardation and possible confounding protective factors that may contribute to the discontinuity of the behavioral retardation trajectory and further prevention of psychopathology. The discontinuity of these behaviors provides a good opportunity to identify factors that could potentially be used in prevention efforts.

The discontinuity of these behaviors provides a good opportunity to identify factors that could potentially be used in prevention efforts.

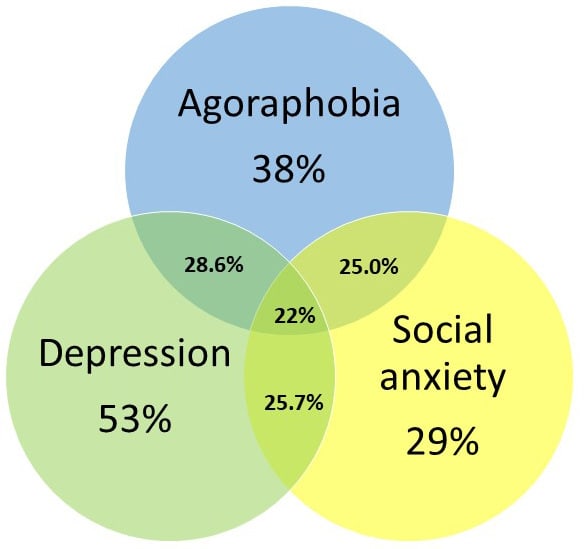

In addition, the relationship between behavioral retardation and depression is much less understood. Given the relationship between behavioral retardation and depression, it is important to note that people with anxiety disorders have an increased risk of developing depression compared to non-anxious people, 51 and data show that in many cases, the presence of one or another anxiety disorder precedes the development of depression. deep depression. 52 Given this temporal relationship between anxiety and depression, it is important to understand that the relationship between behavioral inhibition and depression can be highly dependent on the presence of anxiety. One study is known to have found that social anxiety was a necessary intermediate between behavioral retardation and depression. 53 Similarly, other studies 54 that have found relationships between behavioral retardation, anxiety, and depression have used structural equation modeling, which showed that the pathway by which behavioral retardation leads to anxiety, which in turn leads to depression, provided the most accurate match to the data.

The specificity of the social and non-social components of behavioral inhibition in childhood and their relationship to symptoms of anhedonic depression, social anxiety, and agitation in young adults have now been studied by self-reporting in additional studies. The results were compared with studies showing that non-social behavioral retardation (“fearfulness”), but not social behavioral retardation, increased the risk of future depression; 55 and with other studies showing that depressive symptoms were more strongly associated with social than with non-social behavioral disorder in childhood. 56

Interestingly, Sportel 57 et al. investigated the direct (additive) and indirect (interactive) effects of behavioral retardation and attention control on different dimensions of internalization in a sample of normal adolescents. The results showed a stronger association of behavioral retardation, compared with attention control, with symptoms of anxiety, and a stronger association of attention control, compared with behavioral retardation, with symptoms of depression. Moreover, while behavioral retardation was associated with both anxiety and depression, attentional control mediated this relationship, thus reducing the impact of severe behavioral retardation on both dimensions of internalization.

Moreover, while behavioral retardation was associated with both anxiety and depression, attentional control mediated this relationship, thus reducing the impact of severe behavioral retardation on both dimensions of internalization.

Finally, in considering temperament as a vulnerability factor for depression, it is important to note that, in addition to behavioral inhibition, some theorists have developed temperament models that associate additional temperament styles, namely Positive Emotion (PE) and Negative Emotion (NE), with depression. 58 Many cross-sectional studies have provided evidence that young people and adults diagnosed with depressive symptoms have reduced levels of PE and increased levels of NE, 59,60,61 and their combination was associated with coinciding depressive symptoms in samples of clinical groups 62,63 and groups of people examined en masse at the place of residence. 61,64,65 Moreover, longitudinal studies have shown that lower levels of PE 60,66,67 and higher levels of NE in childhood 68-70 predict the development of depressive symptoms and disorders. For example, low levels of PE in preschoolers predicted high levels of depressogenic-type cognitive style at age 7 and depressive symptoms at age 10. 71.72

For example, low levels of PE in preschoolers predicted high levels of depressogenic-type cognitive style at age 7 and depressive symptoms at age 10. 71.72

Conclusions

Behavioral inhibition is a risk factor for the development of internalizing disorders, although research suggests that not all children with this temperament develop the disorder. Current research is focused on describing the complex interplay of temperament with potential mediating factors that can alter temperament trajectories. Studies focusing on endogenous factors suggest that both attention and executive processes are important regulators of the development of behavioral inhibition towards anxiety or psychological resistance to such disorders. Although it is not mentioned in this review, there is a large body of work on the role of exogenous factors in regulating the temperament of behavioral inhibition. 16.73

Recommendations for parents, services and policy

Identifying young children who are at risk of developing anxiety disorders and implementing preventive (prophylactic) interventions to reduce risk are important outcomes of behavioral inhibition research. Due to the obedient and "comfortable" nature of behaviorally retarded children, teachers and parents may not always recognize such children in early childhood and primary school. Since only a few children with inhibited behavior develop anxiety disorders later on, it is important to identify both endogenous and exogenous factors that mediate the relationship of temperament and psychopathology. Preliminary research contributes to an optimistic view of prevention strategies and easily accessible educational programs for parents and caregivers of adult behaviorally inhibited preschoolers. 74 These programs are aimed at teaching adults about the nature of temperament and withdrawal and how to apply techniques by which they can help behaviorally retarded children develop the ability to manage reactions to new situations, thus promoting the development of social skills and reducing inhibited and anxious behavior over time. Finally, innovative approaches that include training in attention and executive processes can significantly reduce anxiety-induced withdrawal in temperamentally at-risk individuals.

Due to the obedient and "comfortable" nature of behaviorally retarded children, teachers and parents may not always recognize such children in early childhood and primary school. Since only a few children with inhibited behavior develop anxiety disorders later on, it is important to identify both endogenous and exogenous factors that mediate the relationship of temperament and psychopathology. Preliminary research contributes to an optimistic view of prevention strategies and easily accessible educational programs for parents and caregivers of adult behaviorally inhibited preschoolers. 74 These programs are aimed at teaching adults about the nature of temperament and withdrawal and how to apply techniques by which they can help behaviorally retarded children develop the ability to manage reactions to new situations, thus promoting the development of social skills and reducing inhibited and anxious behavior over time. Finally, innovative approaches that include training in attention and executive processes can significantly reduce anxiety-induced withdrawal in temperamentally at-risk individuals.

Literature

- Pine DS, Cohen P, Gurley D, Brook J, Ma Y. The risk for early-adulthood anxiety and depressive disorders in adolescents with anxiety and depressive disorders. Archives of General Psychiatry . Jan 1998;55(1):56-64.

- Essau CA, Conradt J, Petermann F. Frequency and comorbidity of social phobia and social fears in adolescents. Behavior Research and Therapy . Sep 1999;37(9):831-843.

- Fergusson DM, Horwood LJ, Lynskey MT. Prevalence and comorbidity of DSM-III-R diagnoses in a birth cohort of 15 year olds. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Nov 1993;32(6):1127-1134.

- McGee R, Feehan M, Williams S, Partridge F, Silva PA, Kelly J. DSM-III disorders in a large sample of adolescents. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Jul 1990;29(4):611-619.

- Hayward C, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB. Linking self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition to adolescent social phobia.

Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Dec 1998;37(12):1308-1316.

Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Dec 1998;37(12):1308-1316. - Schwartz CE, Snidman N, Kagan J. Adolescent social anxiety as an outcome of inhibited temperament in childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Aug 1999;38(8):1008-1015.

- Schofield CA, Coles ME, Gibb BE. Retrospective reports of behavioral inhibition and young adults' current symptoms of social anxiety, depression, and anxious arousal. Journal of Anxiety Disorders . Oct 2009;23(7):884-890.

- Kagan J. Temperamental contributions to affective and behavioral profiles in childhood. In: Hoffman S.G., Dibartolo, P.M., ed. From social anxiety to social phobia: Multiple perspectives. Needham Heights, MA: Allyn & Bacon; 2001:216-234.

- Prior M, Smart D, Sanson A, Oberklaid F. Does shy-inhibited temperament in childhood lead to anxiety problems in adolescence? Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry .

Apr 2000;39(4):461-468.

Apr 2000;39(4):461-468. - Perez-Edgar K, Fox NA. Temperament and anxiety disorders. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America . Oct 2005;14(4):681-706, viii.

- Garcia C, Kagan J, Resnick JS. Behavioral inhibition in young children. Child Development. 1984;55(3):1005-1019.

- Wichmann C, Coplan R, Daniels T. The social cognitions of socially withdrawn children. Social Development . 2004(13):377-392.

- Biederman J, Hirshfeld-Becker DR, Rosenbaum JF, et al. Further evidence of association between behavioral inhibition and social anxiety in children. American Journal of Psychiatry . Oct 2001;158(10):1673-1679.

- Hirshfeld DR, Rosenbaum JF, Biederman J, et al. Stable behavioral inhibition and its association with anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Jan 1992;31(1):103-111.

- Chronis-Tuscano A, Degnan KA, Pine DS, et al.

Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Sep 2009;48(9):928-935.

Stable early maternal report of behavioral inhibition predicts lifetime social anxiety disorder in adolescence. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Sep 2009;48(9):928-935. - Fox NA, Henderson HA, Marshall PJ, Nichols KE, Ghera MM. Behavioral inhibition: linking biology and behavior within a developmental framework. Annual Review of Psychology . 2005;56:235-262.

- Lonigan CJ, Vasey MW, Phillips BM, Hazen RA. Temperament, anxiety, and the processing of threat-relevant stimuli. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology . Mar 2004;33(1):8-20.

- Perez-Edgar K, Bar-Haim Y, McDermott JM, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA. Attention biases to threat and behavioral inhibition in early childhood shape adolescent social withdrawal. Emotion . Jun 2010;10(3):349-357.

- Rapee RM, Coplan RJ. Conceptual Relations Between Anxiety Disorder and Fearful Temperament. Social Anxiety in Childhood: Bridging Developmental and Clinical Perspectives .

2010;127:17-31.

2010;127:17-31. - Degnan KA, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders: multiple levels of a resilience process. Developmental Psychopathology . Summer 2007;19(3):729-746.

- Lahey BB. Commentary: role of temperament in developmental models of psychopathology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology . Mar 2004;33(1):88-93.

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van-IJzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin . Jan 2007;133(1):1-24.

- Roy AK, Vasa RA, Bruck M, et al. Attention bias towards threat in pediatric anxiety disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Oct 2008;47(10):1189-1196.

- Waters AM, Henry J, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS. Attentional bias towards angry faces in childhood anxiety disorders. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry .

Jun 2010;41(2):158-164.

Jun 2010;41(2):158-164. - Waters AM, Mogg K, Bradley BP, Pine DS. Attentional bias for emotional faces in children with generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . Apr 2008;47(4):435-442.

- Mathews A, MacLeod C. Selective processing of threat cues in anxiety states. Behavior Research and Therapy . 1985;23(5):563-569.

- Wilson E, MacLeod C. Contrasting two accounts of anxiety-linked attentional bias: selective attention to varying levels of stimulus threat intensity. Journal of Abnormal Psychology . May 2003;112(2):212-218.

- Monk CS, Nelson EE, McClure EB, et al. Ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation and attentional bias in response to angry faces in adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry . Jun 2006;163(6):1091-1097.

- Monk CS, Telzer EH, Mogg K, et al. Amygdala and ventrolateral prefrontal cortex activation to masked angry faces in children and adolescents with generalized anxiety disorder.

Archives of General Psychiatry . May 2008;65(5):568-576.

Archives of General Psychiatry . May 2008;65(5):568-576. - Ridderinkhof KR, van den Wildenberg WP, Segalowitz SJ, Carter CS. Neurocognitive mechanisms of cognitive control: the role of prefrontal cortex in action selection, response inhibition, performance monitoring, and reward-based learning. Brain and Cognition . Nov 2004;56(2):129-140.

- Botvinick MM, Braver TS, Barch DM, Carter CS, Cohen JD. Conflict monitoring and cognitive control. Psychological Review . Jul 2001;108(3):624-652.

- Eysenck MW, Derakshan N, Santos R, Calvo MG. Anxiety and cognitive performance: attentional control theory. Emotion . May 2007;7(2):336-353.

- Ladouceur CD, Dahl RE, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Ryan ND. Increased error-related negativity (ERN) in childhood disorders: ERP and source localization. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry . Oct 2006;47(10):1073-1082.

- Hajcak G, McDonald N, Simons RF. Anxiety and error-related brain activity.

Biological Psychology . Oct 2003;64(1-2):77-90.

Biological Psychology . Oct 2003;64(1-2):77-90. - Ursu S, Stenger VA, Shear MK, Jones MR, Carter CS. Overactive action monitoring in obsessive-compulsive disorder: evidence from functional magnetic resonance imaging. Psychological Science . Jul 2003;14(4):347-353.

- Fox NA, Hane AA, Pine DS. Plasticity for affective neurocircuitry - How the environment affects gene expression. Current Directions in Psychological Science. Feb 2007;16(1):1-5.

- Fox NA, Henderson HA, Perez-Edgar K, White L. The Biology of temperament: An integrative approach. In: Nelson C, Luciana M, eds. The handbool of developmental cognitive neuroscience. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 2008:839-854.

- Perez-Edgar K, Reeb-Sutherland BC, McDermott JM, et al. Attention biases to threat link behavioral inhibition to social withdrawal over time in very young children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology . Aug 2011;39(6):885-895.

- Rothbart MK, Ellis LK, Rueda MR, Posner MI.

Developing mechanisms of temperamental effortful control. J Pers . Dec 2003;71(6):1113-1143.

Developing mechanisms of temperamental effortful control. J Pers . Dec 2003;71(6):1113-1143. - Derryberry D, Rothbart MK. Reactive and effortful processes in the organization of temperament. Development and Psychopathology . Fall 1997;9(4):633-652.

- Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM. Temperamental basis of anxiety dosorders in children. In: Vasey MW, Dadds M, eds. The Developmental Psychopathology of anxiety . New York: Oxford University Press; ; 2001:60-91.

- Waters AM, Valvoi JS. Attentional bias for emotional faces in pediatric anxiety disorders: an investigation using the emotional Go/No Go task. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry . Jun 2009;40(2):306-316.

- Thorell L, Bohlin G, Rydell A. Two types of inhibitory control: predictive relations to social functioning. International Journal of Behavioral Development . 2004; 28:193-203.

- Fox NA, Henderson HA. Temperament, emotion, and executive function: Influences on the development of self-regulation.

Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society. San Francisco, 2000, April.

Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Neuroscience Society. San Francisco, 2000, April. - White LK, McDermott JM, Degnan KA, Henderson HA, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition and anxiety: the moderating roles of inhibitory control and attention shifting. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology . Jul 2011;39(5):735-747.

- Righi S, Mecacci L, Viggiano MP. Anxiety, cognitive self-evaluation and performance: ERP correlates. Journal of Anxiety Disorders . Dec 2009;23(8):1132-1138.

- Sehlmeyer C, Konrad C, Zwitserlood P, Arolt V, Falkenstein M, Beste C. ERP indices for response inhibition are related to anxiety-related personality traits. Neuropsychologia . Jul 2010;48(9):2488-2495.

- Hum KM, Manassis K, Lewis MD. Neural mechanisms of emotion regulation in childhood anxiety. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry . In Press. 2012.

- McDermott JM, Perez-Edgar K, Henderson HA, Chronis-Tuscano A, Pine DS, Fox NA.

A history of childhood behavioral inhibition and enhanced response monitoring in adolescence are linked to clinical anxiety. Biological Psychiatry . Mar 1 2009;65(5):445-448.

A history of childhood behavioral inhibition and enhanced response monitoring in adolescence are linked to clinical anxiety. Biological Psychiatry . Mar 1 2009;65(5):445-448. - Lerner RM, Hess LE, Nitz KA. Developmental perspective on psychopathology. In: Herson M, Last CG, eds. Handbook of child and adult psychopathology: a longitudinal perspective . Elmsford, NY: Pergamon Press; 1991:9-32.

- Stein MB, Fuetsch M, Muller N, Hofler M, Lieb R, Wittchen HU. Social anxiety disorder and the risk of depression: a prospective community study of adolescents and young adults. Archives of General Psychiatry . Mar 2001;58(3):251-256.

- Brown TA, Campbell LA, Lehman CL, Grisham JR, Mancill RB. Current and lifetime comorbidity of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders in a large clinical sample. Journal of Abnormal Psychology . Nov 2001;110(4):585-599.

- Gladstone GL, Parker GB. Is behavioral inhibition a risk factor for depression? Journal of Affective Disorders .

Oct 2006;95(1-3):85-94.

Oct 2006;95(1-3):85-94. - Muris P, Merckelbach H, Schmidt H, Gadet B, Bogie N. Anxiety and depression as correlates of self-reported behavioral inhibition in normal adolescents. Behavior Research and Therapy . 2001;39(9):1051-1061.

- Hayward C, Killen JD, Kraemer HC, Taylor CB. Linking self-reported childhood behavioral inhibition to adolescent social phobia. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. Dec 1998;37(12):1308-1316.

- Neal JA, Edelmann RJ, Glachan M. Behavioral inhibition and symptoms of anxiety and depression: is there a specific relationship with social phobia? British Journal of Clinical Psychology . Nov 2002;41(Pt 4):361-374.

- Sportel BE, Nauta MH, de Hullu E, de Jong PJ, Hartman CA. Behavioral Inhibition and Attentional Control in Adolescents: Robust Relationships with Anxiety and Depression. Journal of Child and Family Studies . Apr 2011;20(2):149-156.

- Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S.

Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Feb 1994;103(1):103-116.

Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. Feb 1994;103(1):103-116. - Brown TA, Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. Structural relationships among dimensions of the DSM-IV anxiety and mood disorders and dimensions of negative affect, positive affect, and autonomic arousal. Journal of Abnormal Psychology . May 1998;107(2):179-192.

- Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Newman DL, Silva PA. Behavioral observations at age 3 years predict adult psychiatric disorders. Longitudinal evidence from a birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry . Nov 1996;53(11):1033-1039.

- Lonigan CJ, Hooe ES, David CF, Kistner JA. Positive and negative affectivity in children: confirmatory factor analysis of a two-factor model and its relation to symptoms of anxiety and depression. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology . Jun 1999;67(3):374-386.

- Joiner TE, Jr., Catanzaro SJ, Laurent J. Tripartite structure of positive and negative affect, depression, and anxiety in child and adolescent psychiatric inpatients.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology . Aug 1996;105(3):401-409.

Journal of Abnormal Psychology . Aug 1996;105(3):401-409. - Lonigan CJ, Carey MP, Finch AJ, Jr. Anxiety and depression in children and adolescents: negative affectivity and the utility of self-reports. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology . Oct 1994;62(5):1000-1008.

- Anthony JL, Lonigan CJ, Hooe ES, Phillips BM. An affect-based, hierarchical model of temperament and its relations with internalizing symptomatology. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology . Dec 2002;31(4):480-490.

- Chorpita BF. The tripartite model and dimensions of anxiety and depression: an examination of structure in a large school sample. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology . Apr 2002;30(2):177-190.

- Block JH, Gjerde PF. Personality antecedents of depressive tendencies in 18-year-olds: a prospective study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology . May 1991;60(5):726-738.

- van Os J, Jones P, Lewis G, Wadsworth M, Murray R.

Developmental precursors of affective illness in a general population birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry . Jul 1997;54(7):625-631.

Developmental precursors of affective illness in a general population birth cohort. Archives of General Psychiatry . Jul 1997;54(7):625-631. - Clark LA, Watson D, Mineka S. Temperament, personality, and the mood and anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Psychol . Feb 1994;103(1):103-116.

- Lonigan CJ, Phillips BM, Hooe ES. Relations of positive and negative affectivity to anxiety and depression in children: evidence from a latent variable longitudinal study. Journal of Consultunf and Clinical Psychology . Jun 2003;71(3):465-481.

- Rende RD. Longitudinal relations between temperament traits and behavioral syndromes in middle childhood. Journal of the American Academy of Child Adolescent Psychiatry . Mar 1993;32(2):287-290.

- Dougherty LR, Klein DN, Durbin CE, Hayden EP, Olino TM. Temperamental Positive and Negative Emotionality and Children's Depressive Symptoms: A longitudinal prospective study from age three to age ten.

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29(4):462-488.

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2010;29(4):462-488. - Hayden EP, Klein DN, Durbin CE, Olino TM. Positive emotionality at age 3 predicts cognitive styles in 7-year-old children. Development and Psychopathology . Spring 2006;18(2):409-423.

- Lahat A, Hong M, Fox NA. Behavioral inhibition: is it a risk factor for anxiety? International Review of Psychiatry . Jun 2011;23(3):248-257.

- Rapee RM. The development and modification of temperamental risk for anxiety disorders: prevention of a lifetime of anxiety? Biological Psychiatry . Nov 15 2002;52(10):947-957.

Notes

- Upward and downward information processing strategies are two complementary cognitive processes. The "bottom-up" strategy refers to processes that involve sensory stimulation leading to perceptual processing and subsequent cortical interpretation. In general, the structures involved are, firstly, the subcortical, limbic, then the cortical areas of the brain.

"Downstream" processing refers to the control or modulation of subcortical or limbic processing by cortical regions. – (approx. per.)

"Downstream" processing refers to the control or modulation of subcortical or limbic processing by cortical regions. – (approx. per.) - A brain structure believed to be involved in the detection of a threat or novelty and the production of a conditioned response in connection with the experience of fear.

- The most initial part of the anterior cerebral cortex, located behind the frontal bone. This region of the brain is involved in higher-level executive functions such as attention control, emotion regulation, conflict resolution, complex goal-directed behavior planning, and decision-making processes.

- Subdivision of the anterior cingulate cortex responsible for error detection, response and conflict monitoring, anticipation, attention, motivation, and regulation/impairment of emotional response.

For citation:

Fox NA, Frenkel TI. Temperament in early childhood and the development of anxiety and depression.