Depression and the brain

What Does Depression Physically Do to My Brain?

Written by Keri Wiginton

In this Article

- Brain Size

- Brain Inflammation

- Are the Changes Permanent?

- How to Get Help

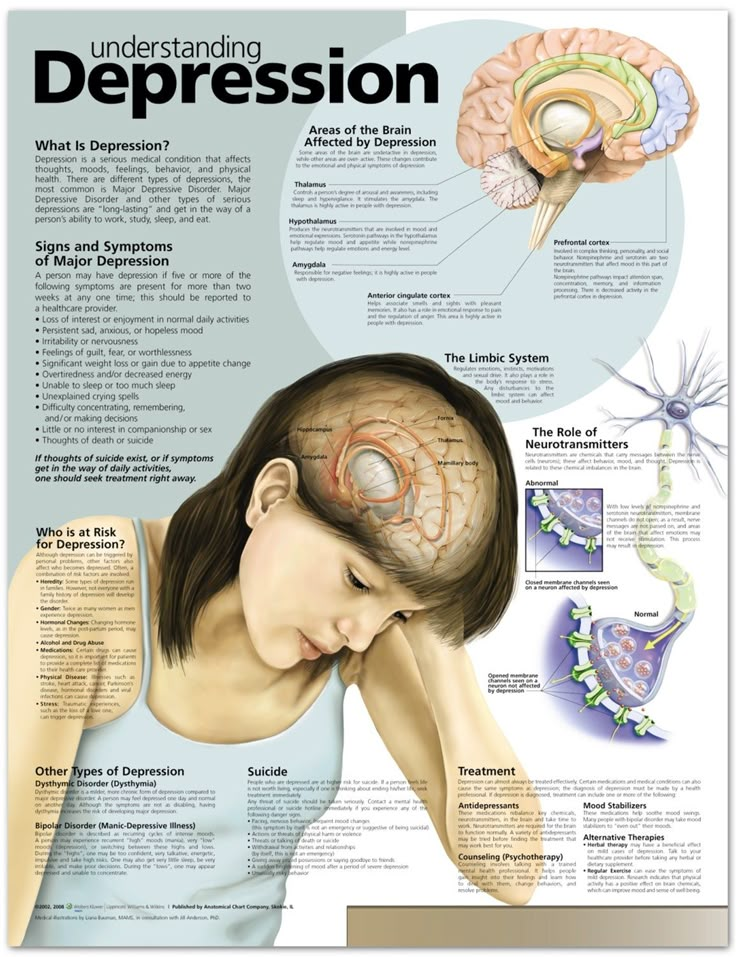

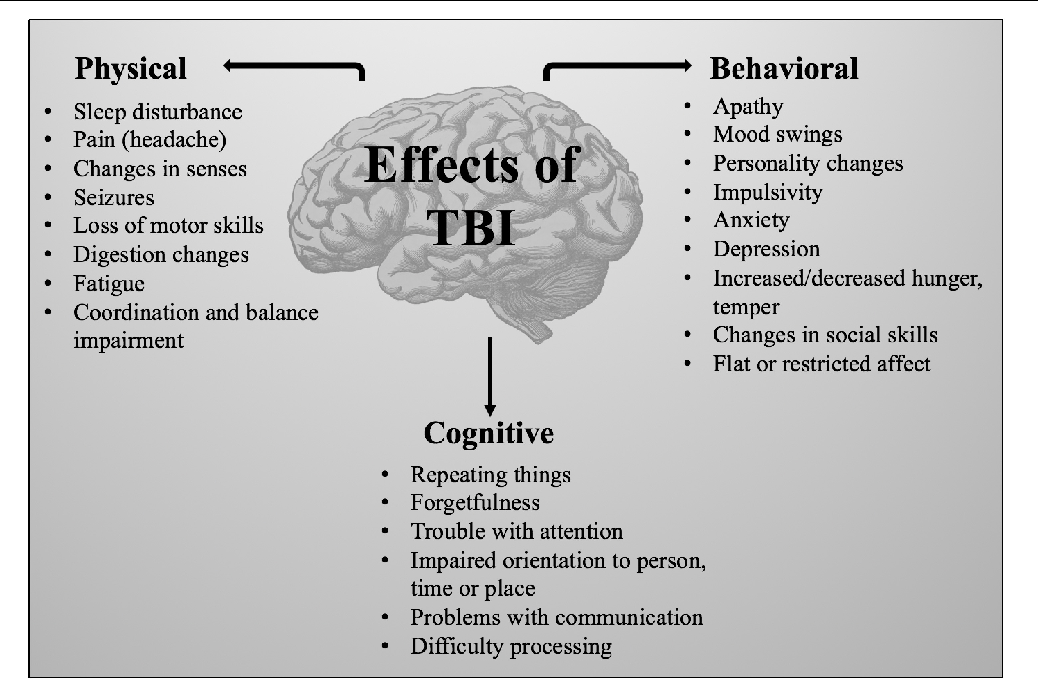

Depression is more than feeling down. It may physically change your brain.

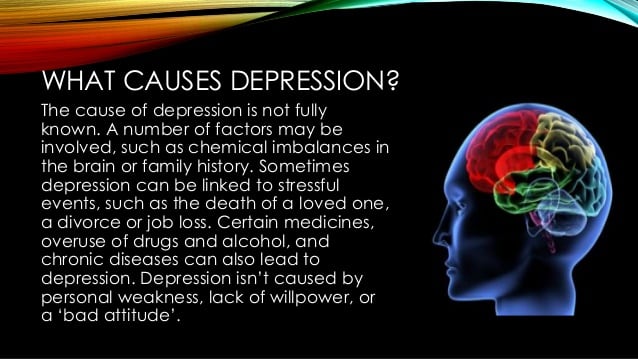

This can affect how you think, feel, and act. Experts aren’t sure what causes these changes. They think genetics, stress, and inflammation might play a role.

It’s important to get help for your depression. That’s because repeat episodes seem to damage your brain more and more over time. Early treatment might help you avoid or ease some of the following changes.

Brain Size

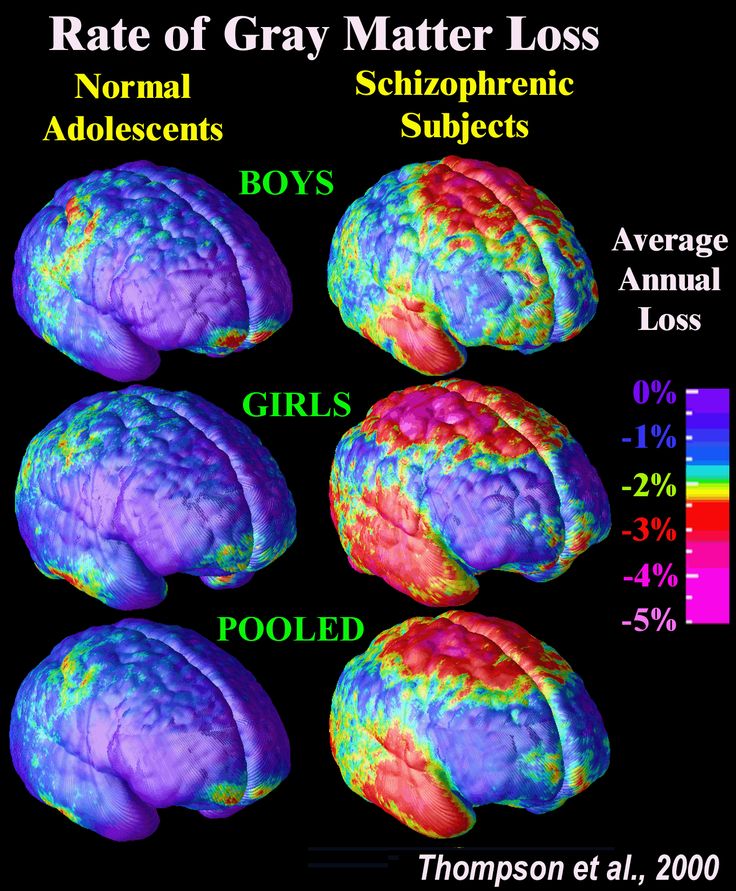

There’s some debate about which areas are affected and how much. There’s growing evidence that several parts of the brain shrink in people with depression. Specifically, these areas lose gray matter volume (GMV). That’s tissue with a lot of brain cells. GMV loss seems to be higher in people who have regular or ongoing depression with serious symptoms.

Studies show depression can lower GMV in these areas:

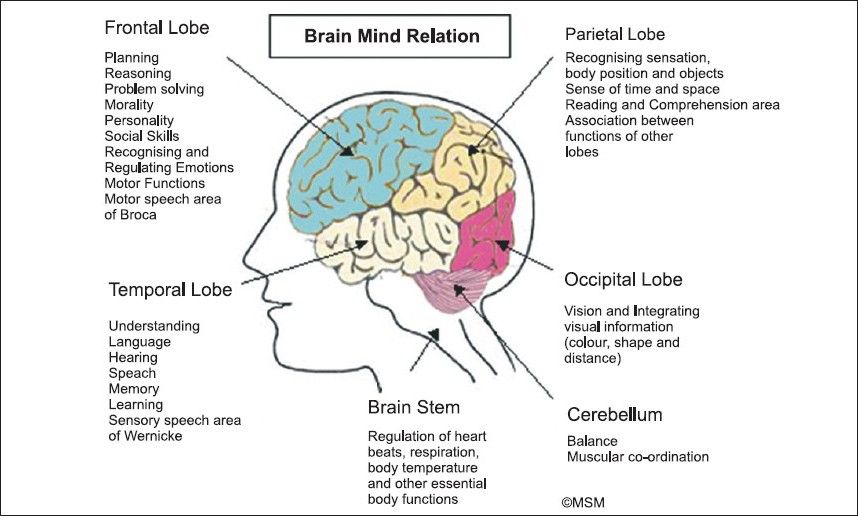

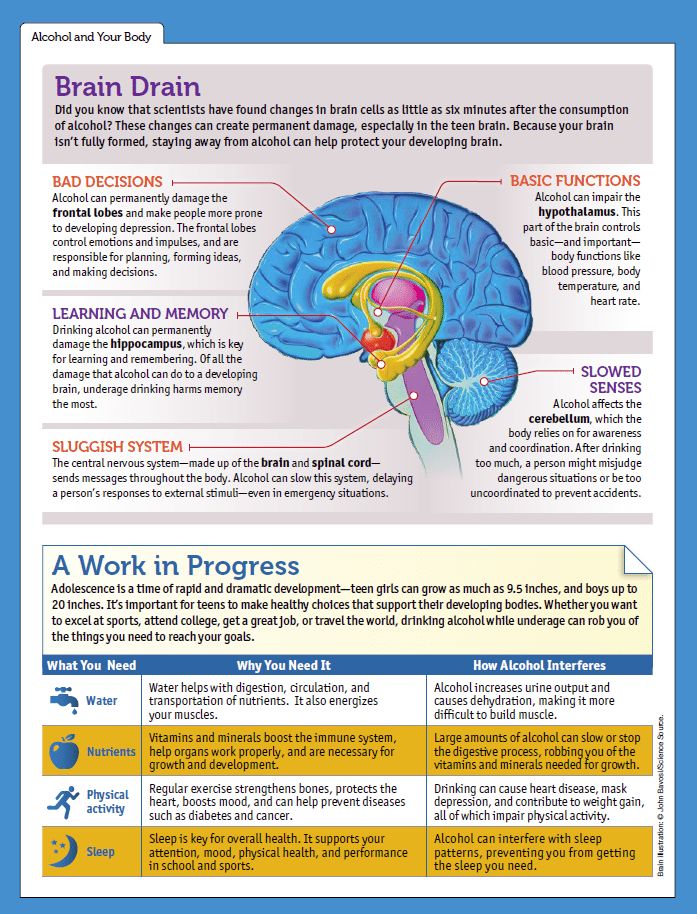

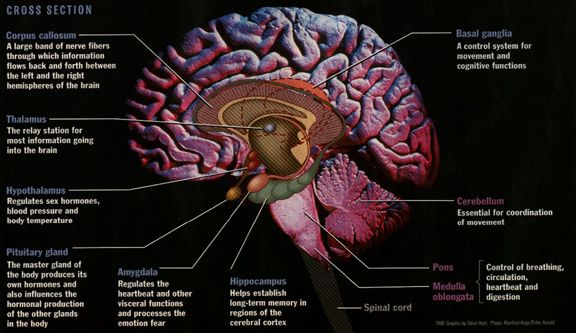

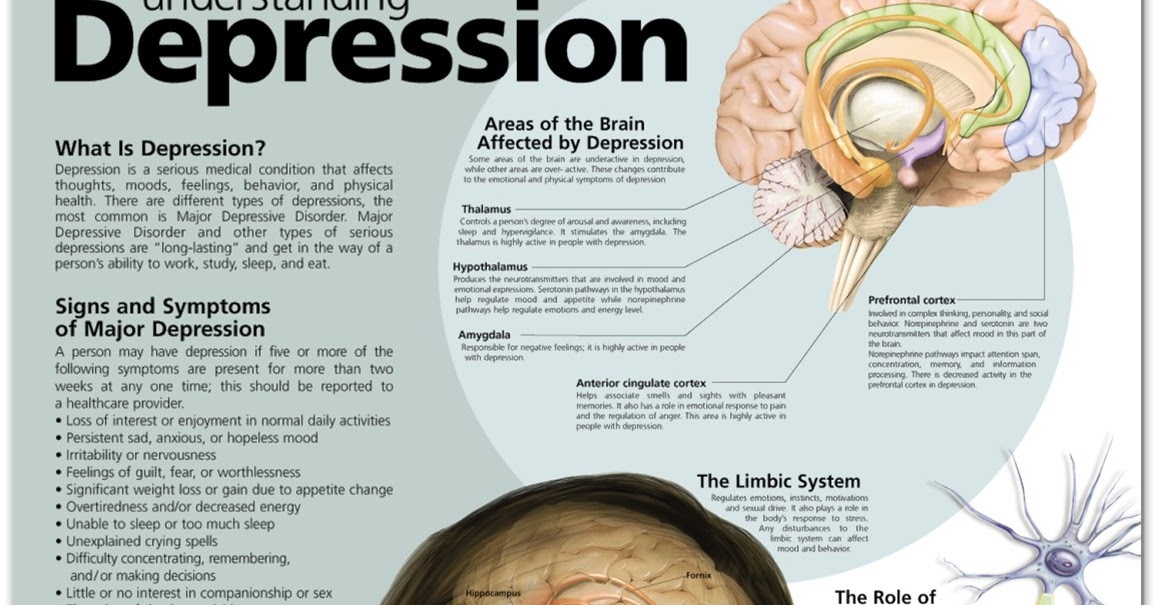

Hippocampus. That part of your brain is important for learning and memory. It connects to other parts of your brain that control emotion and is responsive to stress hormones. That makes it vulnerable to depression.

Prefrontal cortex. This area plays a role in your higher-level thinking and planning.

There’s also evidence these parts of your brain get smaller:

- Thalamus

- Caudate nucleus

- Insula

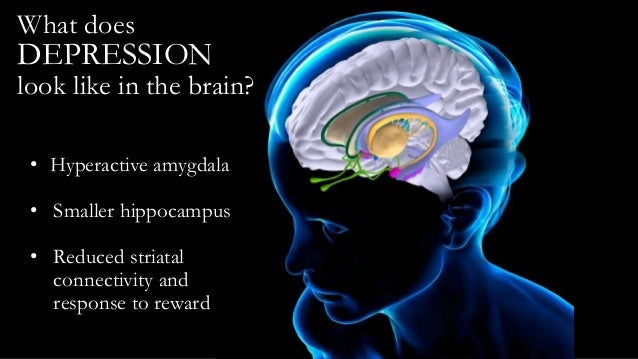

Results are mixed on how depression affects the amygdala. That’s your fear center. Some studies show it gets smaller. Others found that stress and depression might boost its GMV. The more severe the depression, the higher the GMV.

When these areas don’t work the right way, you might have:

- Memory problems

- Trouble thinking clearly

- Guilt or hopelessness

- No motivation

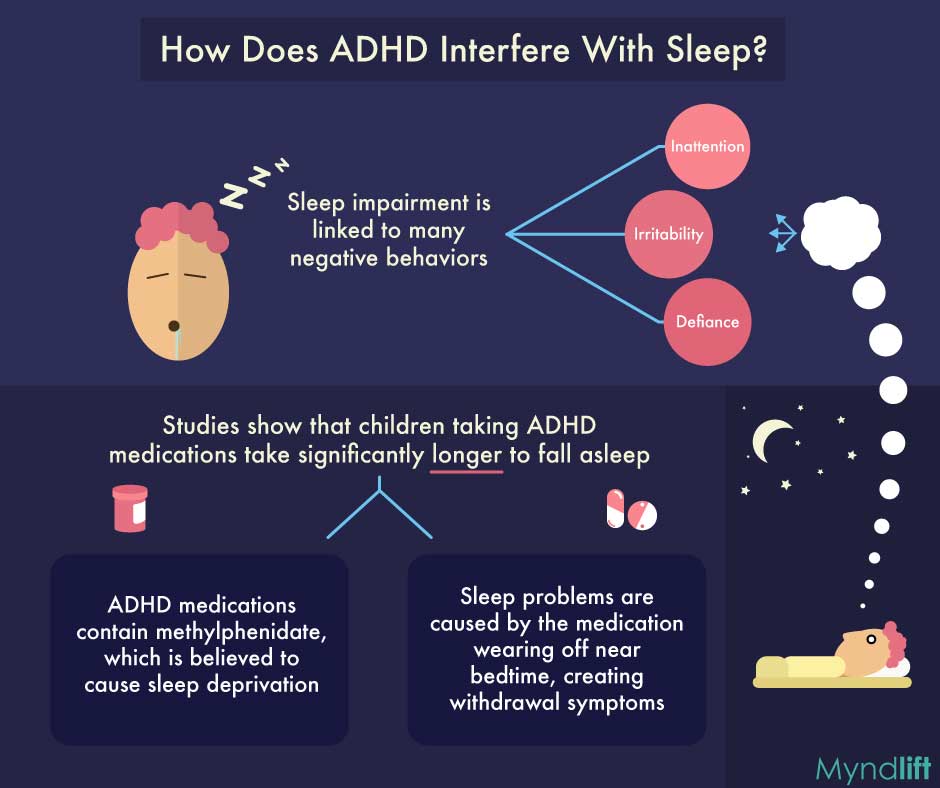

- Sleep or appetite problems

- Anxiety

You might also move or talk slowly, or overreact to negative emotions.

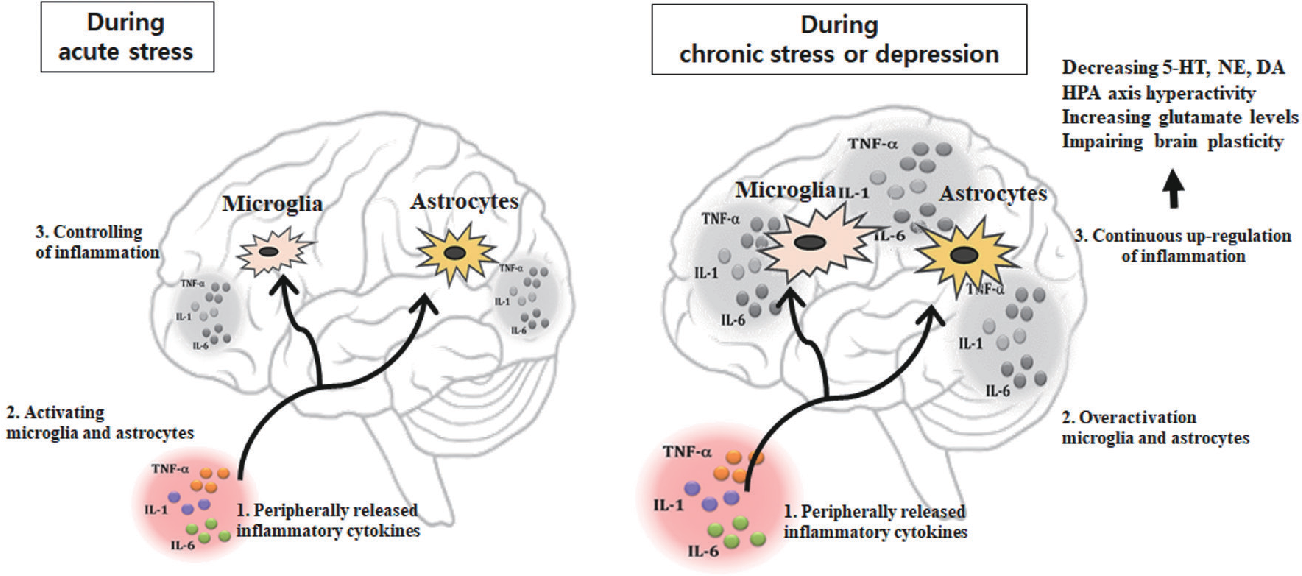

Brain Inflammation

Experts aren’t sure if depression or inflammation comes first. But people who have a major depressive episode have higher levels of translocator proteins. Those are chemicals linked to brain inflammation. Studies show these proteins are even higher in people who’ve had untreated major depressive disorder for 10 years or longer.

Uncontrolled brain inflammation can:

- Hurt or kill brain cells

- Prevent new brain cells from growing

- Cause thinking problems

- Speed up brain aging

Are the Changes Permanent?

Scientists are still trying to answer that question. Ongoing depression likely causes long-term changes to the brain, especially in the hippocampus. That might be why depression is so hard to treat in some people. But researchers also found less gray matter volume in people who were diagnosed with lifelong major depressive disorder but hadn’t had depression in years.

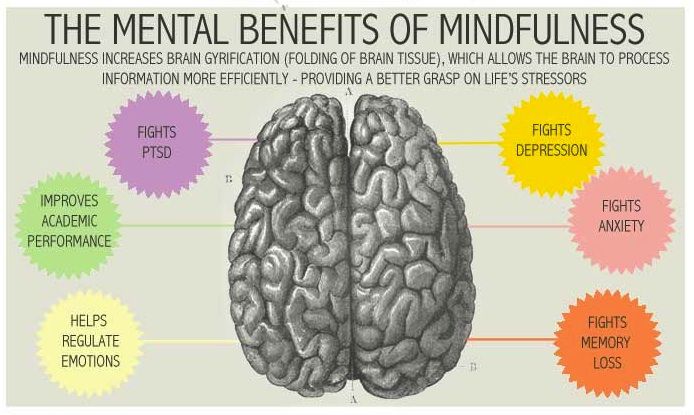

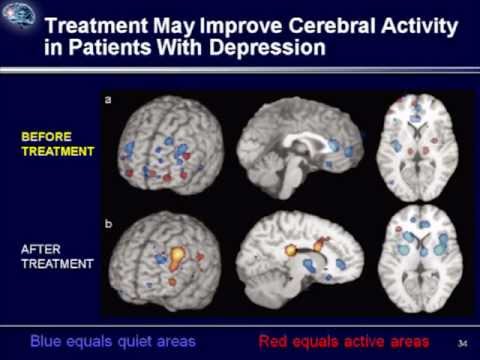

While more research is needed, there’s hope that current or new treatments might help reverse or ward off some brain changes.

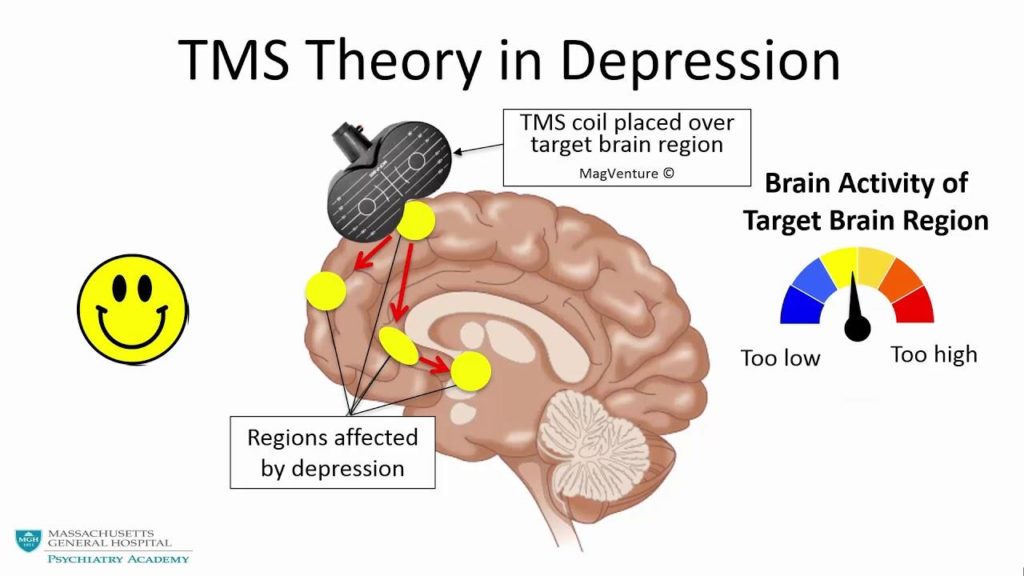

Here’s what research says about two common depression treatments:

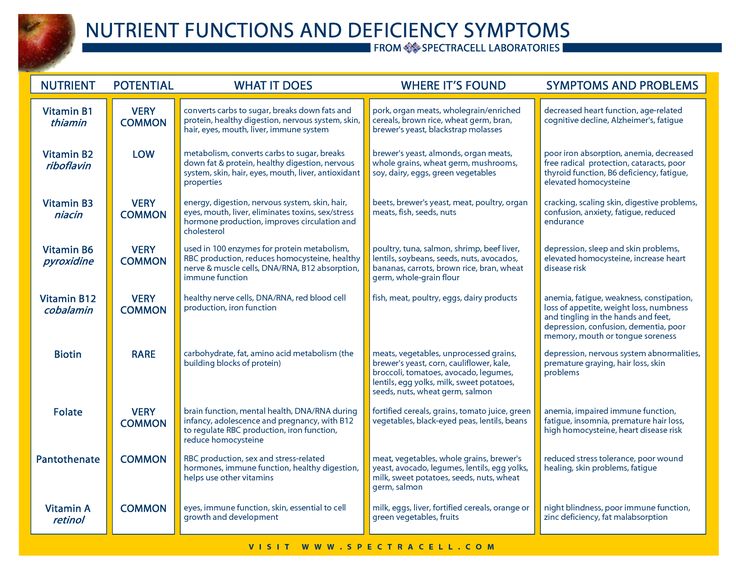

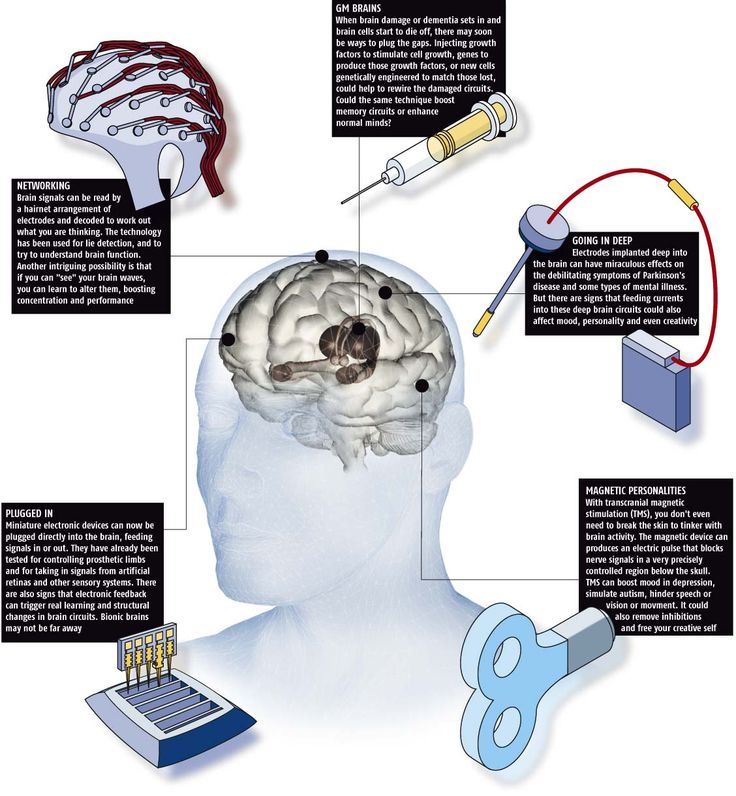

Antidepressants. These work on the chemicals in your brain that control stress and emotions. There’s evidence these drugs can help your brain form new connections and lower inflammation.

Cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). Experts think CBT promotes neuroplasticity. That means you can change your brain in a way that helps your depression.

How to Get Help

Tell your doctor if you have symptoms of depression. They’ll want to rule out other health conditions so they can find you the right treatment. You might need to make some lifestyle changes, take medicine, or talk to a mental health specialist. Some people benefit from a mix of all three.

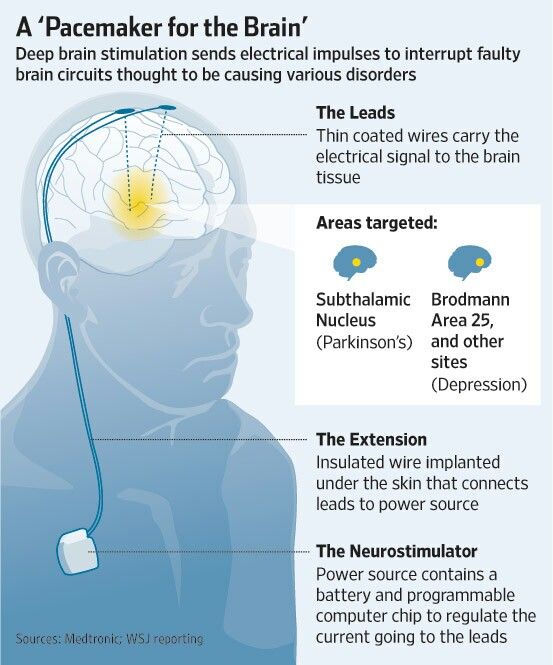

Some treatments for mild or serious depression include:

- Talk therapy

- Antidepressants

- Short-term use of ketamine

- Brain stimulation

- Exercise

- Meditation

- Healthy diet change

Suicide is a serious symptom of depression. Get help right away if you’re thinking about hurting yourself. You can reach someone at the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. They’re available anytime, day or night.

Get help right away if you’re thinking about hurting yourself. You can reach someone at the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255. They’re available anytime, day or night.

How Depression Affects the Brain > News > Yale Medicine

When we think about depression, what comes to mind are feelings and emotions – or, for some, the absence of feelings and emotions. In order to really understand depression, however, it’s important to be aware that the condition has physical aspects as well. Most people understand what depression looks like on the outside, in terms of a person’s behavior, but our medical understanding of the actual progression of the disease and its treatments continues to evolve.

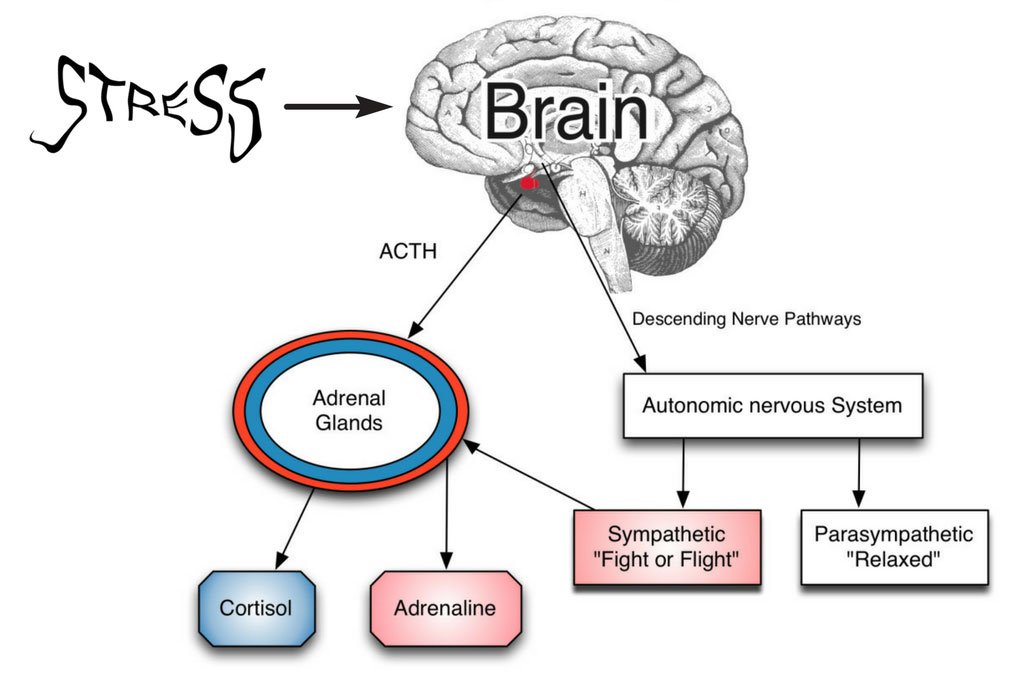

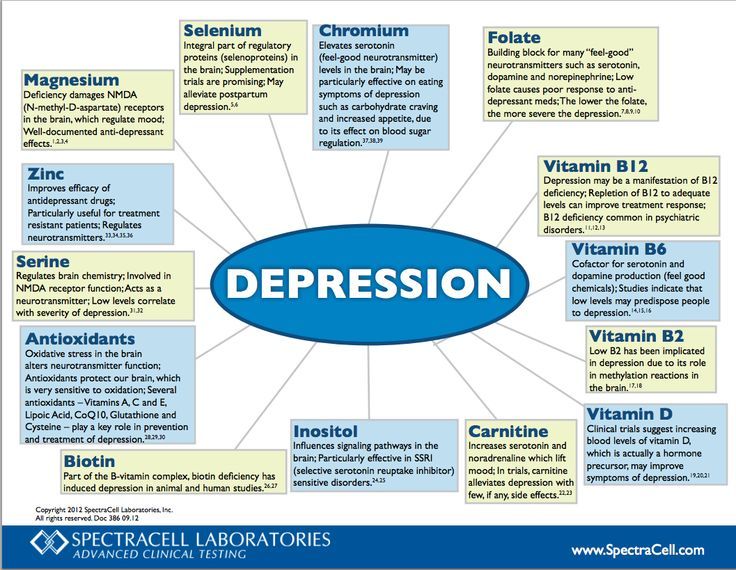

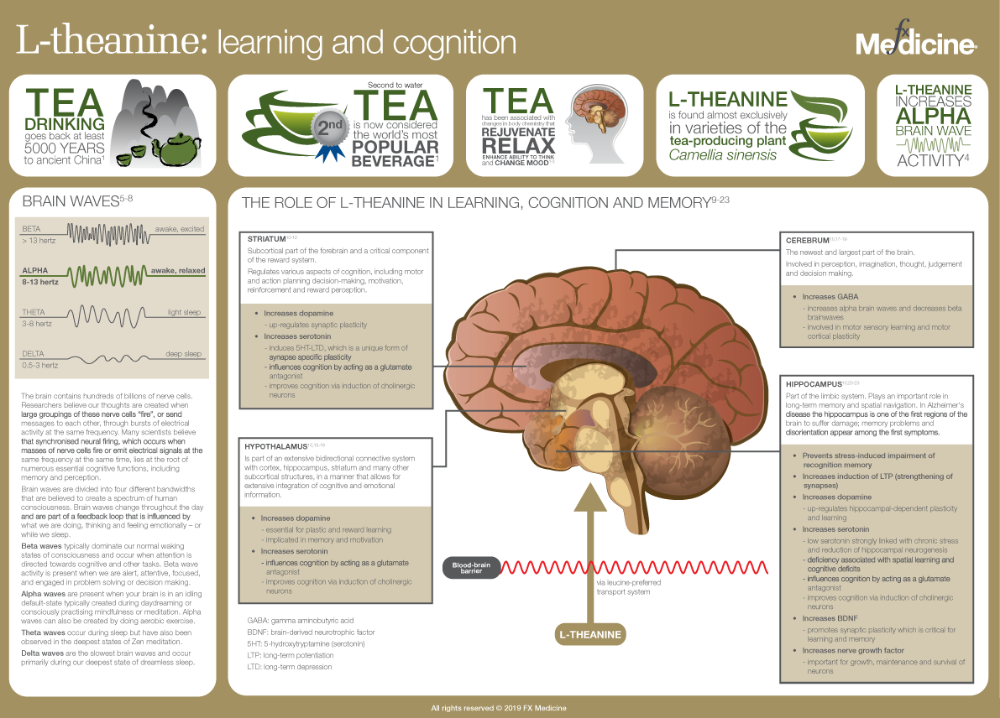

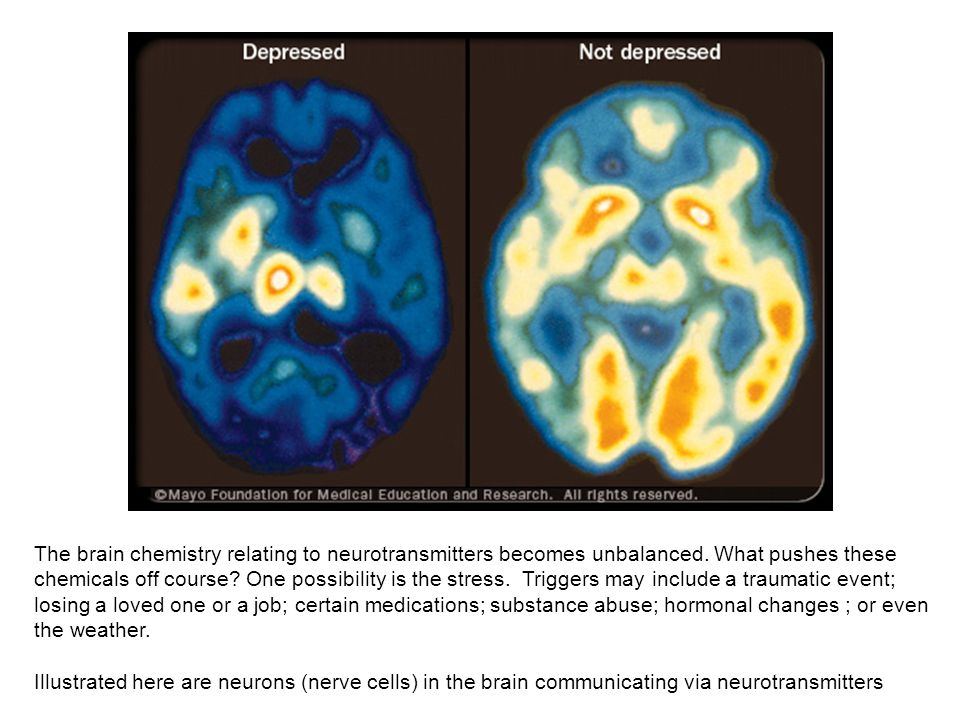

What we know right now is that, on a chemical level, depression involves neurotransmitters, which can be thought of as the messengers that carry signals between brain cells, or neurons.

“The current standard of care for the treatment of depression is based on what we call the ‘monoamine deficiency hypothesis,’ essentially presuming that one of three neurotransmitters in the brain is deficient or underactive,” says Rachel Katz, MD, a Yale Assistant Professor of Clinical Psychiatry.

But according to Dr. Katz, this is only part of the story. There are about 100 types of neurotransmitters overall, and billions of connections between neurons in each person’s brain.

There remains much to learn.

For years and years, doctors and researchers assumed that depression stemmed from an abnormality within these neurotransmitters, particularly serotonin or norepinephrine. But over time, these two neurotransmitters did not seem to account for the symptoms associated with major depression. As a result, doctors began to look elsewhere.

The search proved fruitful. “There are chemical messengers, which include glutamate and GABA, between the nerve cells in the higher centers of the brain involved in regulating mood and emotion,” says John Krystal, MD, chair of Yale’s Department of Psychiatry, noting that these may be alternative causes for the symptoms of depression.

These two are the brain’s most common neurotransmitters. They regulate how the brain changes and develops over a lifetime. When a person experiences chronic stress and anxiety, some of these connections between nerve cells break apart. As a result, communication between the affected cells becomes “noisy,” according to Dr. Krystal. And it’s this noise, along with the overall loss of connections, that many believe contribute to the biology of depression.

This “neurobiology of depression” is important to understand. First, it helps doctors understand how the disease develops and evolves. Also important, though, is that those same doctors can then use their new understanding of depression’s mechanisms to build targeted treatment plans. And, since depression is often a long-term disease, people needs long-term treatments for it.

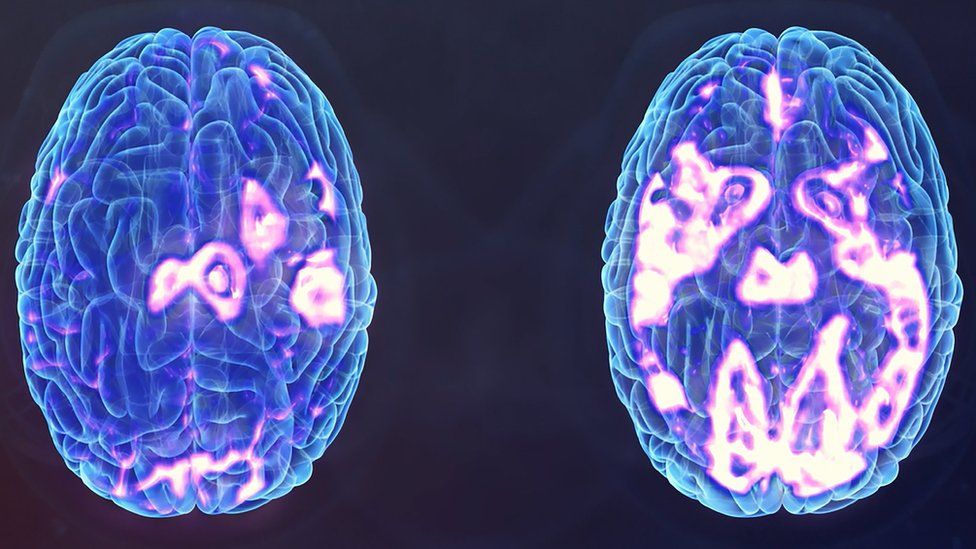

“There are clear differences between a healthy brain and a depressed brain,” Dr. Katz says. “And the exciting thing is, when you treat that depression effectively, the brain goes back to looking like a healthy brain. ”

”

We have entered a new era of psychiatry, Dr. Katz adds. As we shift away from a single hypothesis about what causes depression, we are also learning more about the brain as a whole, in all of its complexities.

In this video, Drs. Katz and Krystal explain how depression affects the brain.

Read more Yale Medicine newsRelated Specialists

Treating Depression: An Expert Discusses Risks, Benefits of Ketamine

NEUROPHYSIOLOGY OF DEPRESSION【 Psychological consultation】

- +38 (067) 448-01-00

- +38 (066) 448-01-00

- [email protected]

- kpt.center.ua nine0005

- Mon.-Fri. 11.00-20.00

- Sat-Sun 10:00-19:00

Sign up for a consultation

Depression is not just sadness or melancholy lasting several days, and not just fatigue. Temporarily giving up after failure is normal. Grieving after the loss of a loved one or the loss of a meaningful relationship is normal. This is not depression, but a normal reaction to difficult circumstances. Clinical depression is a painful condition. Clinical depression is manifested by persistently depressed mood, fatigue, apathy, as well as frequent disturbances in sleep and appetite. The mood can be depressed for several weeks and even months, sometimes for no apparent reason. Fatigue in depression does not go away with rest. The lack of energy can be so strong that it is difficult to perform simple everyday tasks. Cleaning the house or cooking becomes a feat. A therapist can help you understand your condition and understand the difference between fatigue and the depressive or anxious emotions you are experiencing. A therapist can help if you find it difficult to do your daily activities or if you feel overwhelmed. nine0029 In depression, a downward spiral occurs, which is expressed in the fact that the manifestations of depression themselves reinforce the continued existence of depression.

Temporarily giving up after failure is normal. Grieving after the loss of a loved one or the loss of a meaningful relationship is normal. This is not depression, but a normal reaction to difficult circumstances. Clinical depression is a painful condition. Clinical depression is manifested by persistently depressed mood, fatigue, apathy, as well as frequent disturbances in sleep and appetite. The mood can be depressed for several weeks and even months, sometimes for no apparent reason. Fatigue in depression does not go away with rest. The lack of energy can be so strong that it is difficult to perform simple everyday tasks. Cleaning the house or cooking becomes a feat. A therapist can help you understand your condition and understand the difference between fatigue and the depressive or anxious emotions you are experiencing. A therapist can help if you find it difficult to do your daily activities or if you feel overwhelmed. nine0029 In depression, a downward spiral occurs, which is expressed in the fact that the manifestations of depression themselves reinforce the continued existence of depression. For example, on Saturday you are invited to a party, and you think: “something I don’t want to go, and, most likely, it won’t be fun there,” and you decide not to go. Instead, you, say, lie on the couch for a long time, leafing through the Internet. The next day you sleep for a long time, and when you wake up, you feel overwhelmed. No one calls and you feel lonely, or think that no one is interested in you, or stress other people. These thoughts spoil the mood, and even more so, I don’t want to communicate with anyone. It's not about communicating or not communicating. As a result, such thoughts and feelings lead to the fact that a person stops thinking and doing, even what brings him pleasure. And good mood becomes less. Thus, this downward spiral causes the brain to switch to a negative perception of various situations, and this helps to stabilize the state of depression. nine0029 The therapist can help the person reverse this downward spiral and bring it into an upward spiral. For example, if you don’t even go to a party, but call a friend and talk or meet him in a cafe.

For example, on Saturday you are invited to a party, and you think: “something I don’t want to go, and, most likely, it won’t be fun there,” and you decide not to go. Instead, you, say, lie on the couch for a long time, leafing through the Internet. The next day you sleep for a long time, and when you wake up, you feel overwhelmed. No one calls and you feel lonely, or think that no one is interested in you, or stress other people. These thoughts spoil the mood, and even more so, I don’t want to communicate with anyone. It's not about communicating or not communicating. As a result, such thoughts and feelings lead to the fact that a person stops thinking and doing, even what brings him pleasure. And good mood becomes less. Thus, this downward spiral causes the brain to switch to a negative perception of various situations, and this helps to stabilize the state of depression. nine0029 The therapist can help the person reverse this downward spiral and bring it into an upward spiral. For example, if you don’t even go to a party, but call a friend and talk or meet him in a cafe. This little effort can help you enjoy socializing in a more comfortable environment. And it is logical that then it is harder to convince yourself of your own loneliness and uselessness. The less sad thoughts appear, the less the mood deteriorates. And most importantly, with the help of simple actions, a small contribution was made to feeling more comfortable. nine0027

This little effort can help you enjoy socializing in a more comfortable environment. And it is logical that then it is harder to convince yourself of your own loneliness and uselessness. The less sad thoughts appear, the less the mood deteriorates. And most importantly, with the help of simple actions, a small contribution was made to feeling more comfortable. nine0027

In depression, not only do negative emotions predominate, but it is also difficult to feel positive emotions. Joy and satisfaction can be difficult to feel, even when a person understands that he should be happy, but he does not feel joy. A psychotherapist can help a person formulate the goals of psychotherapy, one of which is

"I want to feel joy." People, convinced that nothing brings them pleasure, stop looking for pleasant activities. And it is difficult for them to get positive emotions. For example, a person loves to draw and has been drawing as a hobby for some time. Then he stopped drawing, because as a result of a negative assessment of situations, he set high standards for drawings and underestimated the drawing process itself. Thus, the negative sensations take away the beneficial action, and the absence of pleasant activities exacerbates the negative sensation. Considering the situation in a downward spiral is useful, as there are real physiological causes and consequences of the described psychological complexities. nine0029 In clinical depression, the brain works differently than in a healthy state. With depression, the biochemical and physiological processes in the human brain change. In recent decades, changes in the physiology of the brain and the relationship of these changes with the psychological state of a person have been actively studied. Modern research sheds light not only on the formation of individual manifestations of depression, but also on the impact of various treatments on manifestations of depression. The main treatments for depression are antidepressant medication and psychotherapy. nine0029 Several groups of antidepressants are used to treat depression. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are usually prescribed for the first episode of depression.

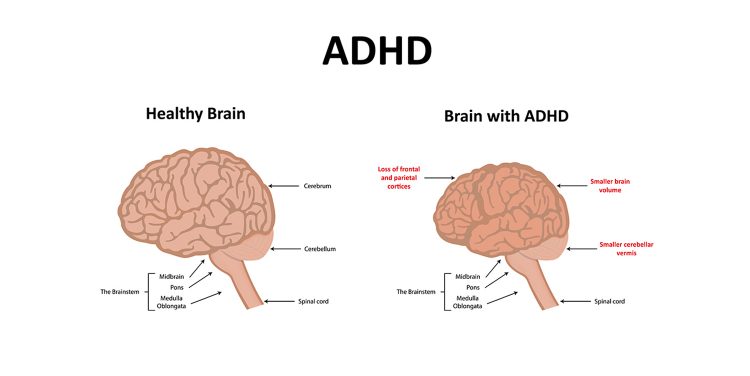

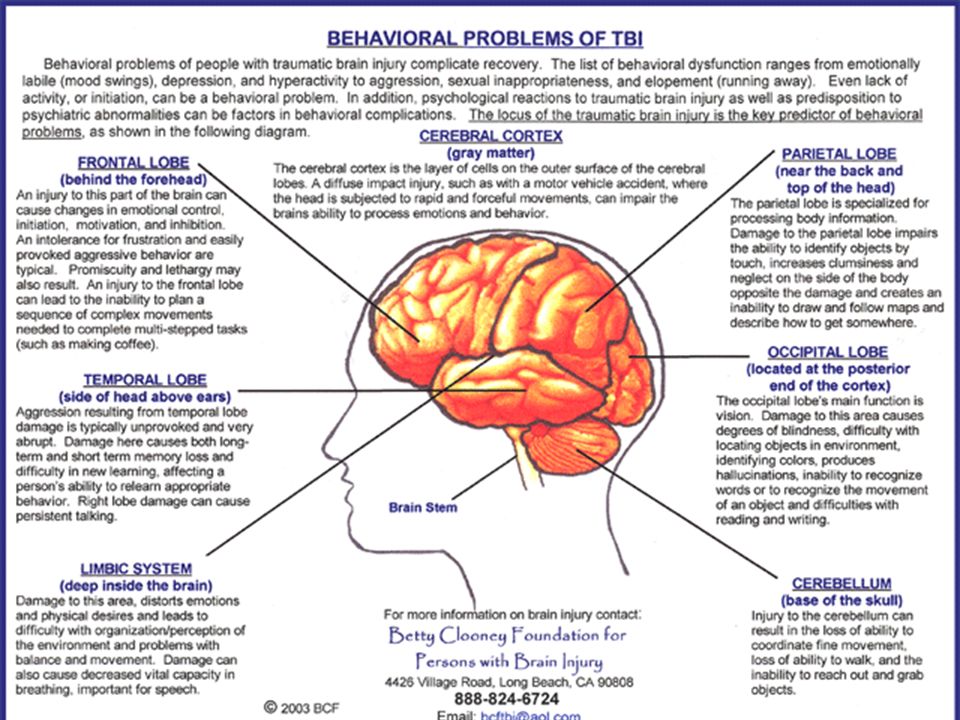

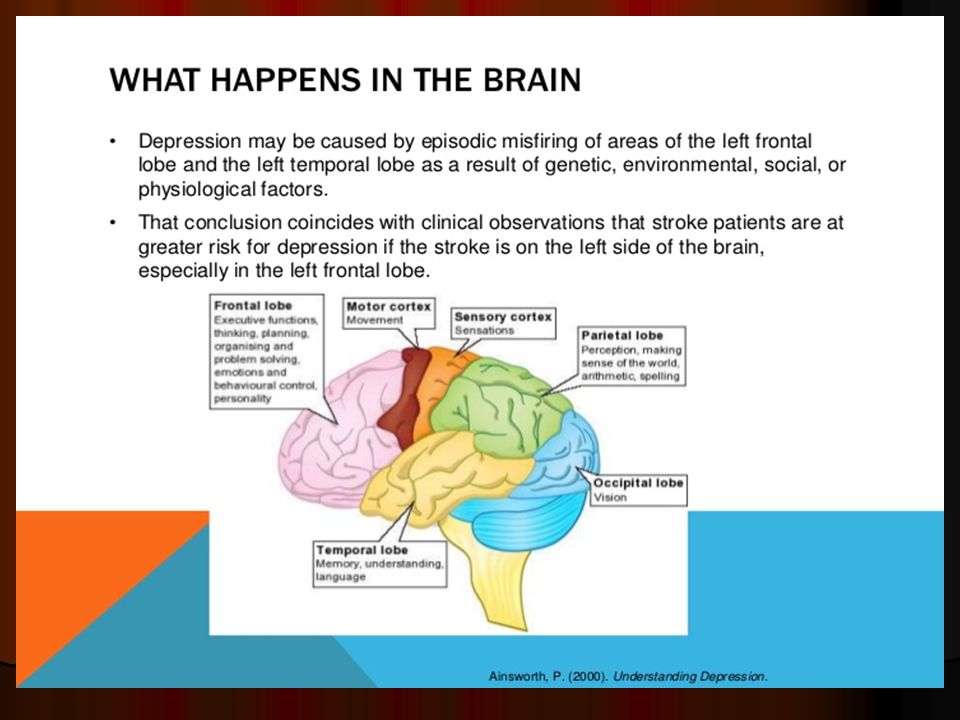

Thus, the negative sensations take away the beneficial action, and the absence of pleasant activities exacerbates the negative sensation. Considering the situation in a downward spiral is useful, as there are real physiological causes and consequences of the described psychological complexities. nine0029 In clinical depression, the brain works differently than in a healthy state. With depression, the biochemical and physiological processes in the human brain change. In recent decades, changes in the physiology of the brain and the relationship of these changes with the psychological state of a person have been actively studied. Modern research sheds light not only on the formation of individual manifestations of depression, but also on the impact of various treatments on manifestations of depression. The main treatments for depression are antidepressant medication and psychotherapy. nine0029 Several groups of antidepressants are used to treat depression. Serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are usually prescribed for the first episode of depression. Second-line drugs include tricyclic antidepressants. Effective types of antidepressants are those developed after 2000, such as serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Dopamine derivatives and melatonin agonists are often used. Antidepressants help increase energy levels, activity, and improve sleep. Dependence does not develop from antidepressants. With the correct use of antidepressants and the correct termination of their use, the withdrawal syndrome does not develop. Antidepressants are prescribed and stopped under the supervision of a physician. nine0029 Neurophysiological studies show that the main areas involved in the development of depression are the cerebral cortex, the hippocampus and the amygdala. The cerebral cortex is the most "smart" part of the brain, which is responsible for the analysis of information, complex mental operations such as writing and reading. In depression, a reduced amount of gray matter was found in the cerebral cortex, especially in the frontal (frontal) zone.

Second-line drugs include tricyclic antidepressants. Effective types of antidepressants are those developed after 2000, such as serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Dopamine derivatives and melatonin agonists are often used. Antidepressants help increase energy levels, activity, and improve sleep. Dependence does not develop from antidepressants. With the correct use of antidepressants and the correct termination of their use, the withdrawal syndrome does not develop. Antidepressants are prescribed and stopped under the supervision of a physician. nine0029 Neurophysiological studies show that the main areas involved in the development of depression are the cerebral cortex, the hippocampus and the amygdala. The cerebral cortex is the most "smart" part of the brain, which is responsible for the analysis of information, complex mental operations such as writing and reading. In depression, a reduced amount of gray matter was found in the cerebral cortex, especially in the frontal (frontal) zone. This part of the brain is responsible for “must”, for volitional purposeful activity. Also, the frontal cortex is responsible for the interaction between the cortex and subcortical structures. A decrease in the amount of gray matter in the frontal cortex can be manifested by the fact that it becomes difficult for a person to concentrate and consciously remember information. When depressed, it can be difficult to do mental work or study. For example, preparing a report at work can seem like such a big task that it is completely unclear how to approach it. When a person does start writing this report, the work goes worse and slower than expected. In this case, it is easy to give up, stop writing it, which can lead to trouble. In this case, the negative spiral of depression is triggered by the accumulation of problems. With the help of a psychotherapist, a person can reverse this spiral. Discuss that it is useful not to scold yourself for the speed of the work, to appreciate what was nevertheless done.

This part of the brain is responsible for “must”, for volitional purposeful activity. Also, the frontal cortex is responsible for the interaction between the cortex and subcortical structures. A decrease in the amount of gray matter in the frontal cortex can be manifested by the fact that it becomes difficult for a person to concentrate and consciously remember information. When depressed, it can be difficult to do mental work or study. For example, preparing a report at work can seem like such a big task that it is completely unclear how to approach it. When a person does start writing this report, the work goes worse and slower than expected. In this case, it is easy to give up, stop writing it, which can lead to trouble. In this case, the negative spiral of depression is triggered by the accumulation of problems. With the help of a psychotherapist, a person can reverse this spiral. Discuss that it is useful not to scold yourself for the speed of the work, to appreciate what was nevertheless done. This allows you not to give up. That is, to do the work in small steps, regularly investing effort. nine0029 Such changes are accompanied by a steady concentration on any negative information, and may be a manifestation of depression. A reduced amount of gray matter in the cerebral cortex also affects thinking, for example, it can manifest itself as a tendency to negatively evaluate any neutral information (Rude et al., 2002), as well as to more easily recall negative information. Cognitive techniques are used as part of cognitive-behavioral therapy to deal with these changes, which occur due to a decrease in the amount of gray matter in the cerebral cortex. They are aimed at identifying specific assessments of situations or thoughts, and testing them for bias, with the subsequent restructuring of these assessments. nine0029 When considering subcortical structures, the area that most often undergoes changes is the hippocampus, or seahorse (Arnone et al., 2013). It is believed that long-term and biographical memory is concentrated in the hippocampus.

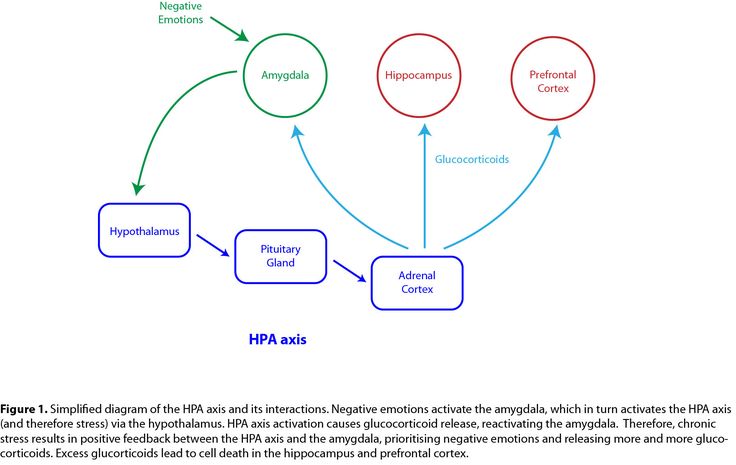

This allows you not to give up. That is, to do the work in small steps, regularly investing effort. nine0029 Such changes are accompanied by a steady concentration on any negative information, and may be a manifestation of depression. A reduced amount of gray matter in the cerebral cortex also affects thinking, for example, it can manifest itself as a tendency to negatively evaluate any neutral information (Rude et al., 2002), as well as to more easily recall negative information. Cognitive techniques are used as part of cognitive-behavioral therapy to deal with these changes, which occur due to a decrease in the amount of gray matter in the cerebral cortex. They are aimed at identifying specific assessments of situations or thoughts, and testing them for bias, with the subsequent restructuring of these assessments. nine0029 When considering subcortical structures, the area that most often undergoes changes is the hippocampus, or seahorse (Arnone et al., 2013). It is believed that long-term and biographical memory is concentrated in the hippocampus. The hippocampus can be compared to a flash drive that contains the story that we tell ourselves about ourselves. It is from this story that we derive deep-seated beliefs about ourselves and about the world. Memories recorded in the hippocampus determine emotional responses to situations that resemble those memories. The hippocampus also plays a role in emotional regulation, specifically in processing emotions, and in responding to positive stimuli. Aboulia, or lack of pleasure in activities that previously brought joy, and lack of motivation for these activities may be associated with a violation of the neurophysiology of the hippocampus. nine0029 Techniques for obtaining new emotional experience are used to work with a person's deep beliefs about himself and the world. These techniques are based on the fact that for our brain, in terms of emotional experience, reality and imagination are not so different. To help a person get a new emotional experience, the technique of transcription, or rewriting, is used.

The hippocampus can be compared to a flash drive that contains the story that we tell ourselves about ourselves. It is from this story that we derive deep-seated beliefs about ourselves and about the world. Memories recorded in the hippocampus determine emotional responses to situations that resemble those memories. The hippocampus also plays a role in emotional regulation, specifically in processing emotions, and in responding to positive stimuli. Aboulia, or lack of pleasure in activities that previously brought joy, and lack of motivation for these activities may be associated with a violation of the neurophysiology of the hippocampus. nine0029 Techniques for obtaining new emotional experience are used to work with a person's deep beliefs about himself and the world. These techniques are based on the fact that for our brain, in terms of emotional experience, reality and imagination are not so different. To help a person get a new emotional experience, the technique of transcription, or rewriting, is used. This technique involves searching for a memory, more often a childhood one, in which a negative emotional experience was received. After that, the situation in this memory is imagined not as it developed in reality, but as the person would like at the time of rewriting. Gradually, individual memories are "rewritten", and the person receives a new emotional experience. nine0029 Recent studies have shown that the network of nerve cells that is responsible for reward in people with clinical depression is characterized by reduced activation in the limbic part of the brain and increased activation of cells in the cerebral cortex. As a result, a person suffering from depression, analytically, intellectually understands that he can rejoice, but it can be difficult for him to feel joy. Also, intellectually, he can find arguments why it is not worth rejoicing, and emotional sensation cannot balance this argument (Zhang, Chang, Guo, Zhang, & Wang, 2013). nine0029 These features can be balanced with behavioral techniques as part of CBT.

Behavioral techniques help increase the number of enjoyable activities. They allow you to first consciously and systematically monitor the improvement in mood during these activities. This process then becomes automatic and helps reduce depressed mood. These techniques help to use the situation that develops during depression, i.e. when the cerebral cortex is activated strongly, and the limbic (emotional) zone of the brain is activated weakly, to improve the human condition. The cortex, with systematic planning and monitoring of positive activities, fixes how much the mood has improved, and whether there is a feeling of satisfaction, and not how much there is nothing to be happy about. To restore balance between the cortex and the limbic system of the brain, and to improve emotional regulation, the mindfulness technique (or as it is also called mindfulness) is used. Elements of mindfulness practices are used in the course of cognitive behavioral therapy. nine0029 Neuroimaging of the physiology of the brain using functional magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed increased activation of the amygdala in people who suffer from depression compared to people who do not suffer from depression.

Amygdala can be compared to an antivirus on a computer. It gives a signal when the brain evaluates any stimulus as a threat. Increased amygdala activity is manifested by a tendency to increased anxiety and avoidance behaviors that are perceived as dangerous, which can limit a person's freedom of action. If depression is accompanied by anxiety, there are behavioral techniques specific to dealing with anxiety disorder. nine0029 Not only structural changes in the brain are responsible for the development and maintenance of depression, but also changes in the biochemistry of the brain, for example, anhedonia (the inability to feel pleasure) is associated with disturbances in the dopamine signaling system. Dopamine can be considered the central biochemical mechanism of habit formation. It is dopamine that gives signals that I did it “well”, you can rejoice and feel satisfaction. These cues influence decision-making related to evaluating the balance of effort and the result of actions, as well as the ability to form responses to rewards (Cohen, Najolia, Kim, & Dinzeo, 2012).

Amygdala can be compared to an antivirus on a computer. It gives a signal when the brain evaluates any stimulus as a threat. Increased amygdala activity is manifested by a tendency to increased anxiety and avoidance behaviors that are perceived as dangerous, which can limit a person's freedom of action. If depression is accompanied by anxiety, there are behavioral techniques specific to dealing with anxiety disorder. nine0029 Not only structural changes in the brain are responsible for the development and maintenance of depression, but also changes in the biochemistry of the brain, for example, anhedonia (the inability to feel pleasure) is associated with disturbances in the dopamine signaling system. Dopamine can be considered the central biochemical mechanism of habit formation. It is dopamine that gives signals that I did it “well”, you can rejoice and feel satisfaction. These cues influence decision-making related to evaluating the balance of effort and the result of actions, as well as the ability to form responses to rewards (Cohen, Najolia, Kim, & Dinzeo, 2012). The disruption of dopamine signaling makes it hard for the brain to pass off chemical goodies for previously pleasurable or adaptive behaviors. nine0029 Scientific evidence shows that clinical depression is accompanied by structural, physiological and chemical changes in the brain. These changes are the basis of manifestations of depression. Any high-quality psychotherapy for depression, and in particular, cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy, does not consist only in “talking”, but has certain approaches and techniques with which it can change the functioning of the brain. Psychotherapy, as well as drug treatment, helps improve the state of the brain in clinical depression. nine0027

The disruption of dopamine signaling makes it hard for the brain to pass off chemical goodies for previously pleasurable or adaptive behaviors. nine0029 Scientific evidence shows that clinical depression is accompanied by structural, physiological and chemical changes in the brain. These changes are the basis of manifestations of depression. Any high-quality psychotherapy for depression, and in particular, cognitive-behavioral psychotherapy, does not consist only in “talking”, but has certain approaches and techniques with which it can change the functioning of the brain. Psychotherapy, as well as drug treatment, helps improve the state of the brain in clinical depression. nine0027

References

- Clasen PC, Beevers CG, Mumford JA, Schnyer DM. Cognitive control network connectivity in adolescent women with and without a parental history of depression. developmental cognitive neuroscience. 2014;7:13–22. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen AS, Najolia GM, Kim Y, Dinzeo TJ.

On the boundaries of blunt affect/alogia across severe mental illness: implications for Research Domain Criteria. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;140:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

On the boundaries of blunt affect/alogia across severe mental illness: implications for Research Domain Criteria. Schizophrenia Research. 2012;140:41–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Cole J, Costafreda SG, McGuffin P, Fu CHY. Hippocampal atrophy in first episode depression: a meta-analysis of magnetic resonance imaging studies. Journal of affective disorders. 2011;134:483–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook IA, Schrader LM, Degiorgio CM, Miller PR, Maremont ER, Leuchter AF. Trigeminal nerve stimulation in major depressive disorder: acute outcomes in an open pilot study. Epilepsy & behavior: E&B. 2013;28:221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerestes R, Ladouceur CD, Meda S, Nathan PJ, Blumberg HP, Maloney K, Phillips ML. Abnormal prefrontal activity subserving attentional control of emotion in remitted

- depressed patients during a working memory task with emotional distracters. psychological medicine. 2012;42:29–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson LA, Berntsen D, Kuyken W, Watkins ER.

Involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memory specificity as a function of depression. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2013;44:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Involuntary and voluntary autobiographical memory specificity as a function of depression. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry. 2013;44:7–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Zeng LL, Shen H, Liu L, Hu D. Unsupervised classification of major depression using functional connectivity MRI. human brain mapping. 2013;35:1630–1641. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang WN, Chang SH, Guo LY, Zhang KL, Wang J. The neural correlates of reward-related processing in major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2013;151:531–539. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

01/28/2022

0026 Homework in psychotherapy Psychotherapy in the method of cognitive-behavioral therapy is not considered in the context of individual consultations…

12/13/2021

Development of tolerance for uncertainty in the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder It is probably difficult to imagine a person who would…

15. 11. 2021

11. 2021

How to overcome the fear of death? I immediately want to start this article with the words that being afraid to die is ...

Facebook page

Sign up for a consultation right now

send a request and our administrator will contact you shortly

Sign up for a consultation

Latest Articles

06/27/2022

06/27/2022

28.01.2022

Activities

13.11.2018

9002ET Online payment consultation nine0027

- +38 (067) 448-01-00

- +38 (066) 448-01-00

- kpt.center.ua

- [email protected]

Copyright © 2021. All rights reserved.

Instagram Youtube Facebook Telegram

Depression as a special mode of brain functioning: data from neuroimaging studies

Depression is a persistent negative emotional state characterized by depressed mood, decreased interest in the environment and inability to enjoy. Its characteristic manifestations are feelings of melancholy, self-abasement, indifference, tearfulness, decreased activity and fatigue, psychomotor retardation or, conversely, arousal. Sleep disturbances in the form of insomnia or, conversely, hypersomnia are typical for depression; changes in appetite with concomitant changes in body weight. nine0027

Its characteristic manifestations are feelings of melancholy, self-abasement, indifference, tearfulness, decreased activity and fatigue, psychomotor retardation or, conversely, arousal. Sleep disturbances in the form of insomnia or, conversely, hypersomnia are typical for depression; changes in appetite with concomitant changes in body weight. nine0027

Depression is an important medical problem, since numerous studies [10, 57] have demonstrated a significant relationship between its severity, morbidity and mortality due to cardiovascular and other somatic diseases. Depression is an independent unfavorable prognostic factor during the postoperative period in surgical patients, associated with a high risk of infectious and neurological complications [28, 42]. The emotional state is one of the most important criteria for the quality of life, and therefore the concept of "health", as defined by the World Health Organization (WHO), includes the psychological well-being of a person, including the absence of depression [1]. Given the potentially curable nature of depression, understanding the mechanisms of its development, as well as the development of objective approaches to the diagnosis of this disorder, are of great scientific and practical importance. nine0027

Given the potentially curable nature of depression, understanding the mechanisms of its development, as well as the development of objective approaches to the diagnosis of this disorder, are of great scientific and practical importance. nine0027

The functioning of the central nervous system in depression has significant differences from the norm. A number of experimental studies [41, 57] have shown the tendency of depressed patients to negatively perceive neutral or even positive stimuli and/or situations. In particular, patients with depression are significantly more likely to perceive a neutral facial expression in portraits as a sign of sadness or anger [14, 31, 41]. In addition, numerous neurophysiological studies have revealed a typical asymmetry in the power of the α-rhythm in the frontal leads for patients with depression [17, 27]. Finally, studies of heart rate indicate a significant relationship between depression and a lack of power in the high- and low-frequency components of the spectrum of its variability [2, 7]. nine0027

nine0027

This review discusses the results of modern neuroimaging studies in depression. It is important to note that in the overwhelming majority of the cited works, the severity of depressive disorders met the DSM-IV criteria for "major" depression. In addition to the data obtained using magnetic resonance imaging, we also cite electroencephalographic studies of depression, the results of which became the basis for the formation of modern concepts of its pathogenesis. nine0027

At the end of the review, we present a description of modern concepts of emotion regulation (the concept of the "negative brain", cognitive regulation of emotions and deficit of activation of the left frontal cortex, which consider depression as a special mode of brain functioning.

Neuroimaging and pathology studies of depression

Structural-anatomical correlates of depression

Most neuroimaging and pathological studies in patients with major depression have shown gray matter deficits in the prefrontal cortex and structures of the limbic system. nine0027

nine0027

The most typical finding in such cases is a gray matter deficit in the anterior cingulate cortex located ventral to the genu corpus callosum (popliteal cingulate cortex) [49]. So, in the study by M. Ballmaier et al. [4] the volume of gray matter in the left and right cingulate gyrus in elderly patients with depression was reduced by 18 and 20%, respectively. In addition, the researchers found a decrease in the volume of white matter in the same brain structure by 14% on the left and 21% on the right. A similar white matter deficit in the left anterior cingulate cortex in elderly depressed patients was noted in a study by S. Bell-McGinty et al. [five]. K. Cullen et al. [16] found a deficit of myelinated tracts connecting the popliteal cingulate cortex to the amygdala in the right hemisphere of the brain in adolescents with depression. At the same time, M. Ries et al. [52], who found gray matter deficits in the posterior cingulate cortex and adjacent cortex in older people with moderately severe depression, did not find significant differences in the volume of the anterior cingulate cortex compared with the control group. According to some researchers [9, 35, 49], pathomorphological changes in the popliteal cingulate cortex are more likely a predisposing factor than a consequence of depression, since this anomaly was detected at the earliest stages of the disease, as well as in healthy individuals with a high family history of affective disorders. So, P. Keedwell et al. [35] revealed differences in the microstructure (decrease in fractional anisotropy) of the cingular fascicle in healthy students with a burdened family history of major depression compared with students who did not have relatives with depression. Intergroup differences were most pronounced in the popliteal area of the left cingular fasciculus. Interestingly, the ability to experience pleasure (hedonia) was positively correlated with the fractional anisotropy of the left and, to a lesser extent, right cingular fasciculus. It is important that in a number of longitudinal studies [49] demonstrated a progressive decrease in the volume of the popliteal cingulate cortex in patients with psychotic depression, as well as significant correlations between the severity of depressive disorders and a deficit in the volume of the popliteal cingulate cortex.

According to some researchers [9, 35, 49], pathomorphological changes in the popliteal cingulate cortex are more likely a predisposing factor than a consequence of depression, since this anomaly was detected at the earliest stages of the disease, as well as in healthy individuals with a high family history of affective disorders. So, P. Keedwell et al. [35] revealed differences in the microstructure (decrease in fractional anisotropy) of the cingular fascicle in healthy students with a burdened family history of major depression compared with students who did not have relatives with depression. Intergroup differences were most pronounced in the popliteal area of the left cingular fasciculus. Interestingly, the ability to experience pleasure (hedonia) was positively correlated with the fractional anisotropy of the left and, to a lesser extent, right cingular fasciculus. It is important that in a number of longitudinal studies [49] demonstrated a progressive decrease in the volume of the popliteal cingulate cortex in patients with psychotic depression, as well as significant correlations between the severity of depressive disorders and a deficit in the volume of the popliteal cingulate cortex.

The volume of the orbitofrontal cortex is also reduced in patients with severe depression compared with the control group [4, 49]. So, in the study by M. Ballmaier et al. [4] patients with depression showed a smaller volume of the medial parts of the orbitofrontal cortex by 19% on the left and 24% on the right and lateral sections - by 12% compared with the control group. At the same time, in some studies, an excess of normative indicators of gray matter volume in a number of areas of the orbitofrontal cortex in patients with depression was noted. So, according to J. Phillips et al. [48], in patients in remission during treatment with antidepressants, there was a general increase in brain volume, which was most pronounced in the orbitofrontal cortex and inferotemporal gyrus of the right hemisphere, although in patients who did not achieve remission in the same period, a decrease in tissue volume in the left hemisphere was recorded. . nine0027

In a number of studies [5, 49], the volume of gray and/or white matter in patients with depression was reduced in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex, the cortex of the frontal poles, and the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. H. Soennesyn et al. [60] found in elderly patients a significant positive correlation between the volume of hyperintense foci in the white matter of the deep parts of the frontal lobes of the brain and the severity of depression, as well as a tendency to persistence of depressive disorders. Similar data were obtained in a longitudinal 3-year study by M. Firbank et al. [22], who noted the relationship between the progression of hyperintense changes in the white matter of the brain and the onset of depression in the elderly. nine0027

H. Soennesyn et al. [60] found in elderly patients a significant positive correlation between the volume of hyperintense foci in the white matter of the deep parts of the frontal lobes of the brain and the severity of depression, as well as a tendency to persistence of depressive disorders. Similar data were obtained in a longitudinal 3-year study by M. Firbank et al. [22], who noted the relationship between the progression of hyperintense changes in the white matter of the brain and the onset of depression in the elderly. nine0027

Deficiency in the volume of prefrontal cortex structures has also been regularly identified in populations at high risk of developing depression. So, A. Carballedo et al. [9] found a deficit in the volume of prefrontal cortex structures in a group of healthy people with a family history of depression aggravated. J. Lagopoulos et al. [40] revealed a significant relationship between a decrease in the size of the frontal cortex and the severity of depressive disorders in young patients already at the initial stage of the disease.

In the same study, a significant relationship was found between the duration of depression and a decrease in the volume of the hippocampal-entorhinal cortex. Similar data were published by K. Sawyer et al. [58], who found a decrease in the volume of the right hippocampus during 4 years of observation of elderly patients with depression. At the same time, in the study by I. Rosso et al. [55], the volume of gray matter in the hippocampus of adolescents with depression did not differ from the control group. nine0027

According to a number of researchers, the size of the amygdala (a subcortical nucleus located in the deep parts of the temporal lobes) in patients with depression is also changed. Thus, smaller amygdala sizes compared to the control group were found in children with depression [41, 55]. For example, I. Rosso et al. [55] noted corresponding changes in adolescent girls with major depression: the tonsils in both hemispheres were 12% smaller in volume compared to the control group. At the same time, in adult patients, the size of the tonsils is sometimes slightly larger compared to the age norm [41]. A possible explanation for these discrepancies is the trend towards a decrease in gray matter volumes as the brain matures, and it is most pronounced in the subcortical nuclei. Accordingly, large volumes of gray matter in populations with mental disorders may be a correlate of delayed brain development. nine0027

Thus, smaller amygdala sizes compared to the control group were found in children with depression [41, 55]. For example, I. Rosso et al. [55] noted corresponding changes in adolescent girls with major depression: the tonsils in both hemispheres were 12% smaller in volume compared to the control group. At the same time, in adult patients, the size of the tonsils is sometimes slightly larger compared to the age norm [41]. A possible explanation for these discrepancies is the trend towards a decrease in gray matter volumes as the brain matures, and it is most pronounced in the subcortical nuclei. Accordingly, large volumes of gray matter in populations with mental disorders may be a correlate of delayed brain development. nine0027

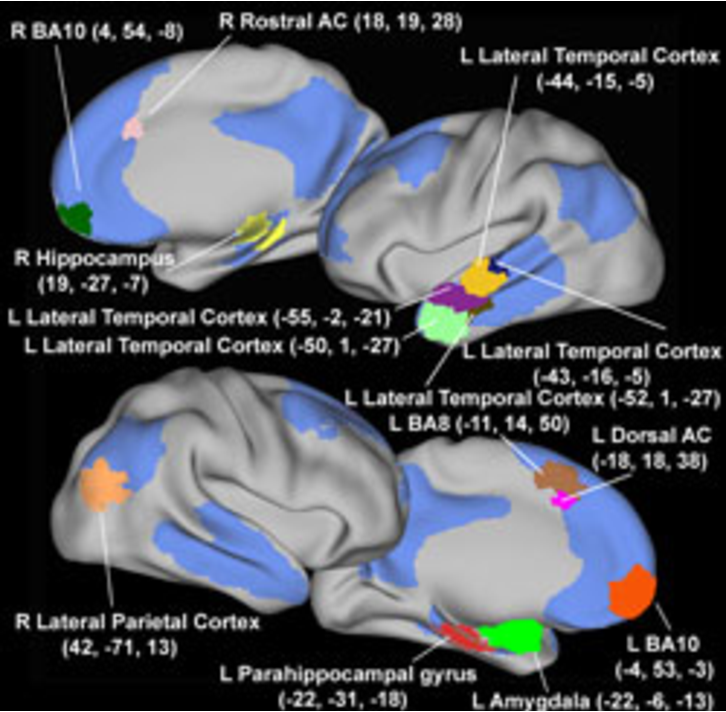

It should be noted that in many neuroimaging and pathological studies in cases of severe depression, gray matter deficit was more pronounced in the left hemisphere compared to the right [49, 63]. So, in the study of P. Tu et al. [63] patients with depression had a significantly smaller volume of the left temporal, entorial and lingual cortex compared to the control group. We also note a higher incidence of depression in patients with damage to the left frontotemporal region compared with damage to the right hemisphere in patients after traumatic brain injuries [8], strokes [65], and other brain diseases. It is important to emphasize that the relationship between left hemispheric brain damage and depression is recorded mainly in cases of small lesions [18]. nine0027

We also note a higher incidence of depression in patients with damage to the left frontotemporal region compared with damage to the right hemisphere in patients after traumatic brain injuries [8], strokes [65], and other brain diseases. It is important to emphasize that the relationship between left hemispheric brain damage and depression is recorded mainly in cases of small lesions [18]. nine0027

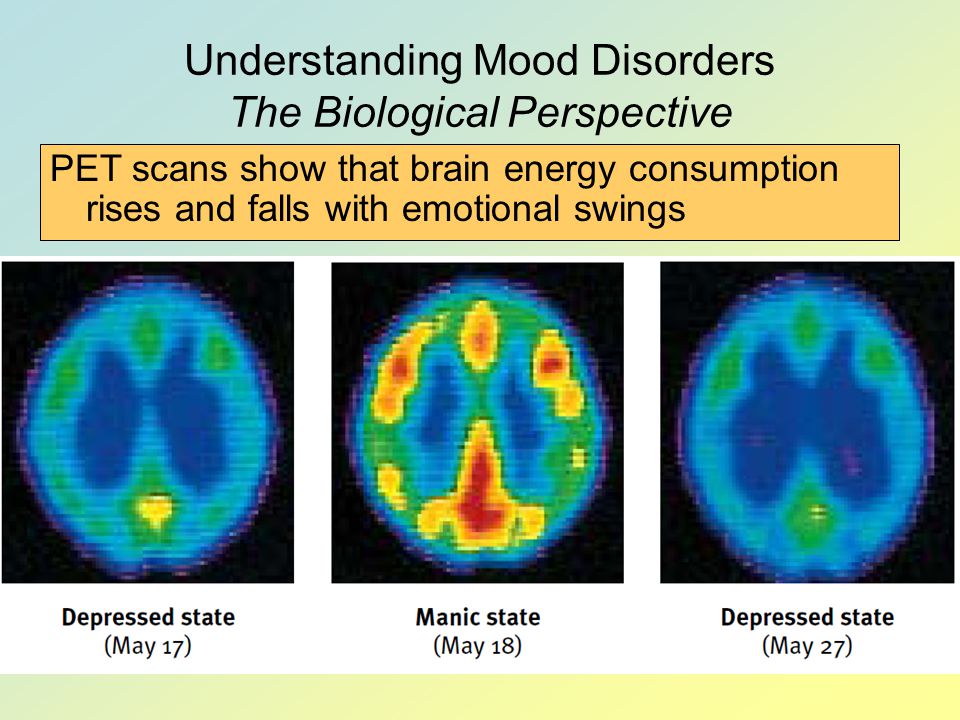

Functional-anatomical correlates of depression

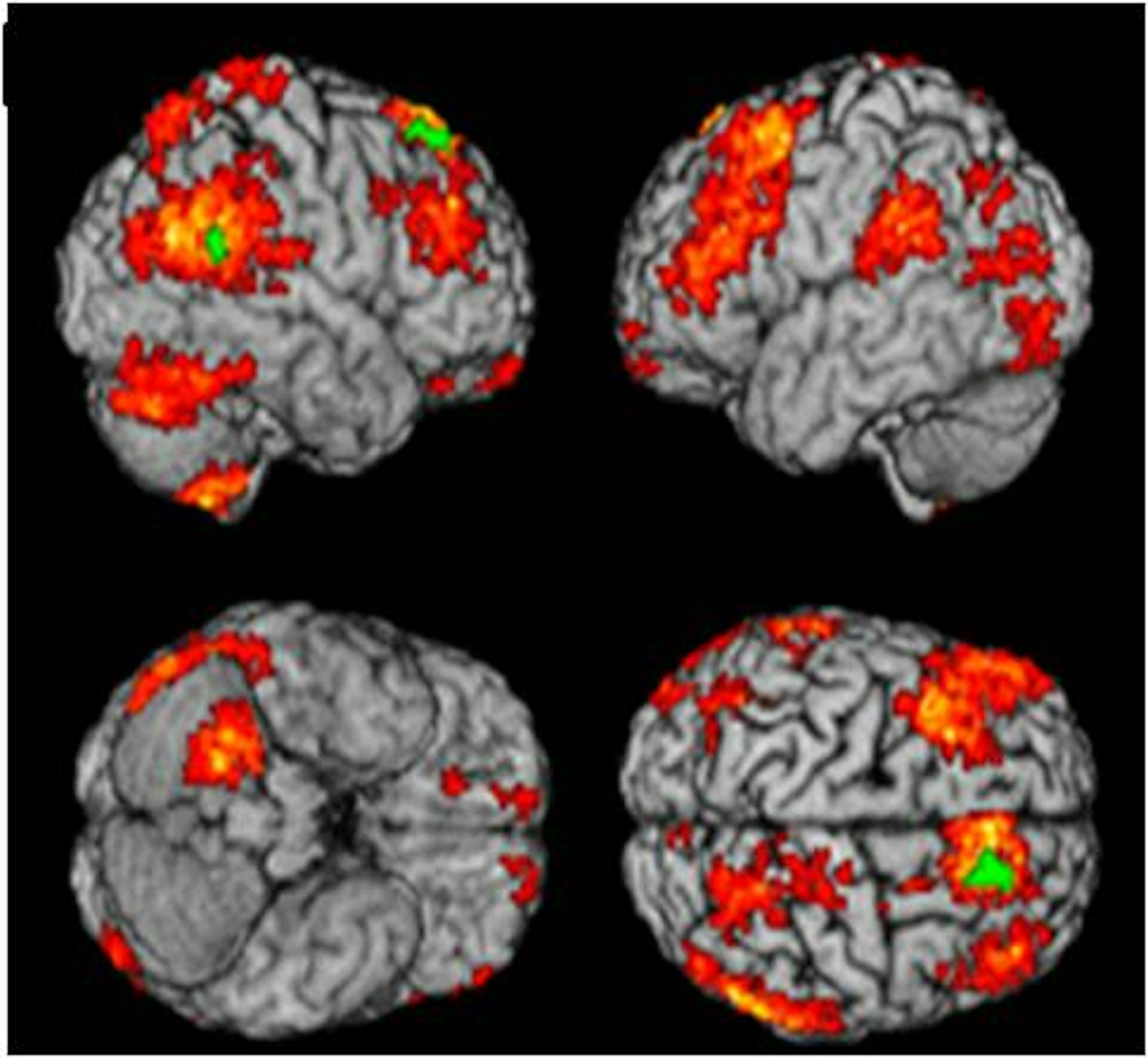

Dozens of studies have now been published investigating the patterns of brain activity in depressed patients using functional magnetic resonance, single photon or positron emission tomography. In most of these studies, brain activity is assessed in terms of performing functional tests with an impact on the emotional sphere. The most common test is to present the patient with portraits of faces with an expression of sadness, fear, anger or joy, as well as photographs of people in a neutral emotional state. nine0027

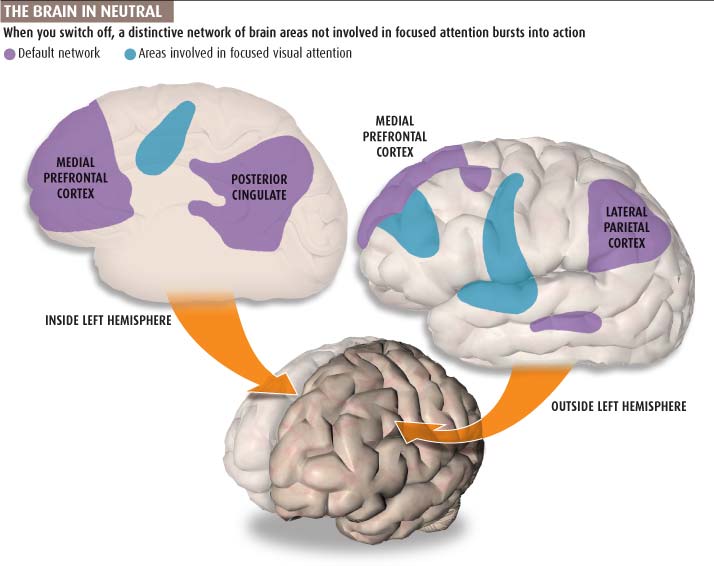

Most of these studies have shown that depressed patients, when presented with sad or frightened faces, tend to respond with hyperactivation of limbic structures such as the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex, and ventromedial prefrontal cortex [41, 49]. At the same time, presentation of joyful faces to patients with depression does not cause activation of the listed brain structures in them, which is characteristic of healthy people. In addition, patients with depression are characterized by a lack of synchronization of activity between the amygdala and the medial prefrontal cortex. The listed functional disorders correlate with the intensity of depressive experiences, and the improvement of the psychological state in such patients is associated with the normalization of the functions of these brain structures. Relapses of depression are accompanied by an increase in metabolism in the popliteal region of the anterior cingulate gyrus, the ventromedial cortex of the frontal poles, and the amygdala [49].

At the same time, presentation of joyful faces to patients with depression does not cause activation of the listed brain structures in them, which is characteristic of healthy people. In addition, patients with depression are characterized by a lack of synchronization of activity between the amygdala and the medial prefrontal cortex. The listed functional disorders correlate with the intensity of depressive experiences, and the improvement of the psychological state in such patients is associated with the normalization of the functions of these brain structures. Relapses of depression are accompanied by an increase in metabolism in the popliteal region of the anterior cingulate gyrus, the ventromedial cortex of the frontal poles, and the amygdala [49].

It has been noted in many studies that anomalies in the activation of structures of the limbic system in patients with depression tend to lateralize. So, J. Almeida et al. [3] observed in patients with depression a lack of interaction between the left hemispheric ventromedial, popliteal cingulate cortex and amygdala in the process of assessing joyful faces. At the same time, the presentation of photographs with frightened faces was accompanied by an excessive expression of conjugation of the activity of the left hemispheric popliteal cortex and amygdala. Z. Mingtian et al. [43] also studied the features of activation of brain structures upon presentation of photographs with frightened faces in young patients with an early onset of depressive disorders. Researchers have observed similar overactivation of the left hemispheric structures - the amygdala, thalamus, prefrontal and temporal cortex, in combination with its insufficiency of the right prefrontal cortex in patients with depression. At the same time, in the study by G. Perlman et al. [47] found that presentation of negative emotional images to depressed adolescents was accompanied by hyperactivation of the right hemispheric amygdala with less interaction of this subcortical structure with the insular cortex and medial prefrontal cortex compared with the control group. J. Fournier et al.

At the same time, the presentation of photographs with frightened faces was accompanied by an excessive expression of conjugation of the activity of the left hemispheric popliteal cortex and amygdala. Z. Mingtian et al. [43] also studied the features of activation of brain structures upon presentation of photographs with frightened faces in young patients with an early onset of depressive disorders. Researchers have observed similar overactivation of the left hemispheric structures - the amygdala, thalamus, prefrontal and temporal cortex, in combination with its insufficiency of the right prefrontal cortex in patients with depression. At the same time, in the study by G. Perlman et al. [47] found that presentation of negative emotional images to depressed adolescents was accompanied by hyperactivation of the right hemispheric amygdala with less interaction of this subcortical structure with the insular cortex and medial prefrontal cortex compared with the control group. J. Fournier et al. [24] reported hyperactivation of the right hemisphere of the amygdala in adult patients with depression upon presentation of photographs with angry faces. In a study by R. Tao et al. [61], bilateral amygdala hyperactivation in combination with hyperactivation of the popliteal cingulate and orbitofrontal cortex was reported in patients with depression upon presentation of photographs with frightened faces. nine0027

[24] reported hyperactivation of the right hemisphere of the amygdala in adult patients with depression upon presentation of photographs with angry faces. In a study by R. Tao et al. [61], bilateral amygdala hyperactivation in combination with hyperactivation of the popliteal cingulate and orbitofrontal cortex was reported in patients with depression upon presentation of photographs with frightened faces. nine0027

E. Rose et al. [54] observed significantly less deactivation of the popliteal cingulate cortex and adjacent medial orbitofrontal cortex in depressed patients who performed a visuospatial memory test. The authors suggested that excessive activation of the popliteal cingulate cortex in depression is directly related to negative experiences in such patients.

Lack of activation of the ventral striatum during reward is also characteristic of patients with depression [49]. So, in the study by O. Robinson et al. [53] in patients with depression, a reduced ability to learn with reward was noted against the background of normal learning indicators with punishment. In the same study, behavioral deficits in depressed patients were accompanied by deficits in activation of the ventral striatum in response to rewards.

In the same study, behavioral deficits in depressed patients were accompanied by deficits in activation of the ventral striatum in response to rewards.

Brain activity in depressed patients at rest is also altered. So, M. Gaffrey et al. [25] observed a lack of coordinated activity between the posterior cingulate cortex and areas of the middle temporal gyrus, inferior parietal lobule, and cerebellum in children with depression compared to the age norm. nine0027

At the same time, coordination of activity in the posterior cingulate and anterior popliteal cortex was increased in children with depression. A similar lack of conjugation of activity in the posterior cingulate cortex and adjacent cortical centers in young patients with depression was observed by X. Zhu et al. [68]. In addition, in this same patient population, excessive coordination of activity in the anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex was found. M. Wu et al. [66] observed excessive synchronization of the activity of the dorsomedial prefrontal and orbitofrontal cortex in elderly depressed patients with a synchronization deficit in the popliteal cingulate cortex. The listed anomalies of brain activity at rest correlated with a number of psychopathological phenomena characteristic of depression. In particular, excessive synchronization of the activity of the anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex correlated with the tendency to obsessions in a study by X. Zhu et al. [68]. In a study by S. Green et al. [29] lack of coordinated activity between the popliteal cingulate and temporal cortex correlated with ideas of self-blame and guilt.

The listed anomalies of brain activity at rest correlated with a number of psychopathological phenomena characteristic of depression. In particular, excessive synchronization of the activity of the anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex correlated with the tendency to obsessions in a study by X. Zhu et al. [68]. In a study by S. Green et al. [29] lack of coordinated activity between the popliteal cingulate and temporal cortex correlated with ideas of self-blame and guilt.

A number of studies have revealed changes in the activity of the amygdala and prefrontal cingulate cortex in patients in remission. P. Kanske et al. [34] observed excessive activity of the amygdala in patients in remission when viewing plots with negative content. In addition, R. Elliott et al. [20] revealed in such patients insufficient activation of the frontal poles and lateral orbitofrontal cortex when presented with images with social plots, both negative and positive. Hypoactivation of the left hemispheric orbitofrontal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex when looking at photographs with frightened faces in patients in remission was also demonstrated in a study by R. Kerestes et al. [36]. nine0027

Kerestes et al. [36]. nine0027

In the same study, activation of the right hemispheric dorsolateral prefrontal cortex was positively correlated with duration of euthymia.

H. Cremers et al. [13] studied the correlation between neuroticism (in this case, it was considered as a risk factor for depression) in middle-aged healthy people and the activity of brain structures when assessing the expression of anger, fear, and sadness in portrait photographs. The authors found a significant direct correlation between neuroticism and the activity of the right hemispheric dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, while in individuals with elevated levels of neuroticism, activity in this region of the prefrontal cortex correlated with activity in the right amygdala; in the group with a high level of neuroticism, the activity of the left amygdala correlated less with the right hemispheric cingulate gyrus compared to the subjects with a low level of neuroticism. Another research group [21] found a positive relationship between neuroticism and excessive activation of the insular cortex in the decision-making process under conditions of information deficit. nine0027

nine0027

Neurophysiological correlates of depression

R. Davidson [17] was the first to point out the relationship between the severity of interhemispheric asymmetry of frontal cortex activation and predisposition to severe depression. He proposed a method for measuring interhemispheric asymmetry as the difference between the power of α-activity (8-13 Hz) in the right (F4) and left (F3) frontal leads. Based on the results of his own research, the author revealed the relative nature of the hypoactivation of the left frontal cortex in patients with severe depression, demonstrating the relationship between the activation of the left frontal cortex and positive affective reactions, on the one hand, and the activation of the right frontal cortex and negative affective reactions, on the other. nine0027

Subsequently, a number of research groups confirmed the relationship between hypoactivation of the left frontal cortex and the severity of depression. So, I. Gotlib et al. [27] noted hypoactivation of the left frontal cortex not only in persons with severe depression, but also in those cases where there were episodes of depression in history (during the examination, the patients were in remission). The authors did not reveal significant correlations between the asymmetry of frontal cortex activation and the severity of unrealistic ideas about oneself or the opinions of other people, i.e. correlations with cognitive factors that reduce stress resistance. No relationship was found between hemispheric asymmetry and performance of the well-known Stroop test. The researchers concluded that hypoactivation of the left frontal area is an important predisposing factor in the pathogenesis of depression. However, hypoactivation of the left frontal area is not associated with the current state of depression or cognitive factors that reduce stress tolerance. nine0027

Gotlib et al. [27] noted hypoactivation of the left frontal cortex not only in persons with severe depression, but also in those cases where there were episodes of depression in history (during the examination, the patients were in remission). The authors did not reveal significant correlations between the asymmetry of frontal cortex activation and the severity of unrealistic ideas about oneself or the opinions of other people, i.e. correlations with cognitive factors that reduce stress resistance. No relationship was found between hemispheric asymmetry and performance of the well-known Stroop test. The researchers concluded that hypoactivation of the left frontal area is an important predisposing factor in the pathogenesis of depression. However, hypoactivation of the left frontal area is not associated with the current state of depression or cognitive factors that reduce stress tolerance. nine0027

Although the relationship between depression and interhemispheric asymmetry of α-activity in the frontal leads has been established in many studies, it has not been found in some studies. So, S. Reid et al. [51] found no intergroup differences in the distribution of α-activity power in the frontal leads. Nevertheless, in this study, the “classic” intergroup differences in the indices of interhemispheric asymmetry of α-activity in the frontal leads were revealed by a separate analysis of data related to the first minutes of EEG recording. It is also important that, unlike other researchers, the authors used too “soft” criteria for inclusion in the study of both patients and participants in the control group, which could lead to “blurring” of intergroup differences. nine0027

So, S. Reid et al. [51] found no intergroup differences in the distribution of α-activity power in the frontal leads. Nevertheless, in this study, the “classic” intergroup differences in the indices of interhemispheric asymmetry of α-activity in the frontal leads were revealed by a separate analysis of data related to the first minutes of EEG recording. It is also important that, unlike other researchers, the authors used too “soft” criteria for inclusion in the study of both patients and participants in the control group, which could lead to “blurring” of intergroup differences. nine0027

Interestingly, in a study by D. Smit et al. [59], the relationship between hemispheric asymmetry and the risk of developing depressive and anxiety disorders was significant only in a subgroup of young women. In the same study, the influence of heredity on the severity of interhemispheric asymmetry in the group of both young women and young men was revealed.

At the same time, in middle-aged subjects, the severity of interhemispheric asymmetry was significantly higher compared to young people, however, the influence of heredity on interhemispheric asymmetry in this group was not revealed. nine0027

nine0027

Thus, the results of neuroimaging studies point to three main features of the functioning of the brain in patients with depression: firstly, depression is characterized by excessive activity of such structures of the limbic system as the tonsils, popliteal cingulate and ventromedial prefrontal cortex, while the maximum severity of such changes is observed in exposure to negative incentives. Secondly, patients with depression are characterized by a deficiency of gray matter and abnormal functioning of the frontotemporal structures of the cerebral cortex. Thirdly, in depression there is a tendency to more pronounced anomalies in the functioning of the structures of the left hemisphere of the brain, including a typical finding of electroencephalographic studies is a deficit in activation of the left prefrontal cortex in patients with depression. These features correspond to modern concepts of emotion regulation, which we consider below. nine0027

Modern concepts of emotion regulation

The "negative brain" concept

The term "negative brain" was proposed by L. Carretié et al. [11] based on data from experimental and neuroimaging studies indicating the activation of a number of brain structures in response to negative stimuli. The fundamental function of the structures that make up the "negative brain" is to provide rapid and intense responses to dangerous, harmful and potentially destructive events. Obviously, an effective response to such stimuli has a more important adaptive value than a response to neutral or positive (attractive) stimuli. nine0027

Carretié et al. [11] based on data from experimental and neuroimaging studies indicating the activation of a number of brain structures in response to negative stimuli. The fundamental function of the structures that make up the "negative brain" is to provide rapid and intense responses to dangerous, harmful and potentially destructive events. Obviously, an effective response to such stimuli has a more important adaptive value than a response to neutral or positive (attractive) stimuli. nine0027

In dangerous situations, the organism is required to urgently mobilize the appropriate resources, and the evolutionary process supported the formation of neurological mechanisms that can increase adaptive capabilities in difficult conditions. The speed of information processing in brain structures can only be ensured by reducing the number of connections between neuronal centers, i.e. relative specialization of such centers in the processing of the same type of information patterns. Thus, in the structure of the brain, a number of neuronal centers specialize primarily in processing information about threatening and destructive events. The data of modern studies indicate the relative autonomy of the "negative brain", provided with its own sensory subcortical centers, cortical analyzer and executive structures [11]. nine0027

The data of modern studies indicate the relative autonomy of the "negative brain", provided with its own sensory subcortical centers, cortical analyzer and executive structures [11]. nine0027

The amygdala is the most studied structure of the "negative brain". It receives direct projections from the thalamus and sensory cortex, which makes it possible to form fast responses to negative stimuli that are independent of higher cortical centers [11, 38]. The quick response of the amygdala to negative stimuli is also ensured by direct connections of these structures with a number of executive vegetative and motor centers of the brain.

Numerous experimental studies have demonstrated the leading role of the amygdala in the formation of conditioned reflex manifestations of fear and anxiety [19]. In healthy people, activation of the tonsils is recorded mainly when looking at faces with an expression of fear or sadness, while this trend is most pronounced after the induction of a sad mood in patients [26, 64]. The studies presented in the first part of the review indicate the maximum severity of these tendencies in depression.

The studies presented in the first part of the review indicate the maximum severity of these tendencies in depression.

In addition to the amygdala, to the brain structures mainly involved in the processing of negative information, L. Carretié et al. [11] include the ventromedial prefrontal cortex and the adjacent anterior cingulate cortex, the anterior insula, and some other brain structures whose functions are less studied. Some researchers [62] suggest that the medial prefrontal cortex, including the anterior cingulate cortex, forms the subject's cognitive representation of current affective experiences. Other authors [33] point to the direct involvement of the ventromedial cortex in the formation of associations between threatening events and the context in which they occur. Finally, there is an opinion that the activation of the popliteal cingulate cortex in the process of processing negative information is aimed at finding a decision on further actions [54]. Probably, the deficit of gray matter in the popliteal cingulate cortex and the ventromedial prefrontal cortex adjacent to it reduces the computing capabilities of these brain structures in depressed patients and leads to the stereotyping of the “decisions” being formed. nine0027

nine0027

The hyperactivation of the “negative brain” structures detected in patients with depression explains such clinical characteristics of depression as the persistent tendency of depressed patients to perceive neutral stimuli as negative [13, 31, 41] and a deficit in heart rate variability [2, 7]. The latter is explained by the direct involvement of the amygdala and anterior cingulate cortex in the regulation of heart rate [15, 67].

Concept of cognitive regulation of emotions

Cognitive deficit is a fairly common finding in the neuropsychological examination of patients with depression. A number of studies have found that patients with depression are characterized by a lower level of education compared with the corresponding control groups [5, 52]. The most pronounced cognitive deficit is recorded in patients with psychotic depression (with delusional ideas) [23]. In the work of K. Blankstein et al. [6], who examined students with moderate depression, it was found that they have great difficulties in resolving interpersonal conflicts, as well as in organizing their time, everyday life and the educational process. Thus, cognitive deficits can be considered a common component of depressive disorders and possibly an unfavorable prognostic factor. nine0027

Thus, cognitive deficits can be considered a common component of depressive disorders and possibly an unfavorable prognostic factor. nine0027

J. Gross and R. Thompson [30] formulated the main postulates of the concept of cognitive regulation of emotions. In their opinion, the emotional system of the brain is capable of self-regulation, however, the “meaningfulness” of emotional processes has a significant impact on the emotional state of the subject. The ability to make the right choice, taking into account the long-term outcomes of a particular form of behavior, requires significant cognitive effort and relies on previous experience. Active transformation of the current situation, the ability to switch attention from unpleasant but inevitable moments, to see the positive in an ambiguous context are important cognitive mechanisms that allow an individual to adapt to emotionally difficult conditions. Accordingly, cognitive deficit deprives the individual of the opportunity to adapt to difficult conditions, which in many cases leads to depression. nine0027

nine0027

A number of experimental studies [37, 39] have established a direct link between being in an information-enriched environment and neuroplastic changes in the “cognitive” cortex. Neuroplastic changes in the structures of the brain include thickening of the gray matter, elongation and an increase in the "branching" of dendrites, an increase in the density of dendritic spines and the density of synapses on them. At the same time, stressful situations inhibit neuroplastic processes and cause reverse changes in brain structures [50]. This can be demonstrated using the results of an experimental study by J. Radley et al. [50]: 3-week stress led to a decrease in the length and "branching" of dendrites of neurons in the medial prefrontal cortex by 20% and a decrease in the number of synapses on pyramidal neurons by 33%. The authors suggest that hypotrophic changes on the background of stress are a consequence of hypercortisolemia, which is a typical characteristic of depressive disorders. Such results of experimental studies of stress are consistent with the results of neuroimaging studies of depression, which showed a decrease in gray matter volume in a number of brain structures with an increase in the duration of the disease [5, 58]. nine0027

Such results of experimental studies of stress are consistent with the results of neuroimaging studies of depression, which showed a decrease in gray matter volume in a number of brain structures with an increase in the duration of the disease [5, 58]. nine0027

Thus, a vicious circle is formed in depressive disorders. Cognitive deficit reduces adaptive capabilities and contributes to the subject getting into stressful situations. At the same time, chronic stress and hypercortisolemia exacerbate hypotrophic changes in brain structures, which leads to aggravation of cognitive deficits and depression.

Left frontal cortex activation deficit concept

The concept of left frontal cortex activation deficit in depression is a special case of the concept of cognitive emotion regulation. However, modern studies point to the importance of this factor in the pathogenesis of affective disorders. So, K. Ochsner et al. [46] recorded a pronounced activation of the left convexital prefrontal cortex in the process of “rethinking” the meaning of an emotionally negative plot picture in healthy people. The main finding of this study was an inverse correlation between the degree of activation of the left hemispheric dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the degree of activation of the right hemispheric amygdala and left orbitofrontal cortex. In other words, the researchers observed an "inhibitory" effect of activation of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on the structures of the "negative" brain. At present, the inhibitory (braking) effect of the prefrontal cortex on the activity of the amygdala is a generally recognized fact, since it has been demonstrated in numerous studies, including neuroimaging studies [18, 32]. nine0027

The main finding of this study was an inverse correlation between the degree of activation of the left hemispheric dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the degree of activation of the right hemispheric amygdala and left orbitofrontal cortex. In other words, the researchers observed an "inhibitory" effect of activation of the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex on the structures of the "negative" brain. At present, the inhibitory (braking) effect of the prefrontal cortex on the activity of the amygdala is a generally recognized fact, since it has been demonstrated in numerous studies, including neuroimaging studies [18, 32]. nine0027

In a number of neuroimaging and neurophysiological studies, a tendency was established for greater activation of the left frontal cortex against the background of experiencing positive emotions in healthy people and the right frontal cortex - negative ones [18, 44]. In a study by J. Coan and J. Allen [12], the predominance of activation of the left frontal cortex compared to the right hemisphere significantly correlated with the tendency to active behavior in healthy people. Thus, the deficit in activation of the left prefrontal cortex, recorded in numerous studies of patients with depression, explains the deficit of positive emotions and lethargy in a significant proportion of these patients. nine0027

Thus, the deficit in activation of the left prefrontal cortex, recorded in numerous studies of patients with depression, explains the deficit of positive emotions and lethargy in a significant proportion of these patients. nine0027

Conclusion

Short-term states of depression are experienced throughout life by almost every person, since negative emotional experiences are a normal reaction of people to stressful and tragic events. Not all adverse events in the environment and especially within the body require active action from the individual. On the contrary, in many situations, adaptation is provided by the complete cessation of activity with monitoring of information about the danger. According to R. Nesse [45], depression is a natural way of adapting the body to such unfavorable conditions, when vigorous activity can worsen the situation of the individual. In such cases, pessimism, self-abasement, and loss of interest in the outside world force the individual to refrain from unnecessary and dangerous activities. In other words, depression is a special mode of brain functioning, characterized by a significant decrease in the individual's motivated activity in the environment. At the same time, the depressive type of internal experiences and behavioral manifestations is a consequence of the dominance of activity in such structures of the "negative brain" as the amygdala and the structures of the medial prefrontal cortex closely related to it. nine0027

In other words, depression is a special mode of brain functioning, characterized by a significant decrease in the individual's motivated activity in the environment. At the same time, the depressive type of internal experiences and behavioral manifestations is a consequence of the dominance of activity in such structures of the "negative brain" as the amygdala and the structures of the medial prefrontal cortex closely related to it. nine0027

Depression acquires a pathological character in cases where there are no real prerequisites for negative experiences in the environment surrounding the individual or the potentially solvable nature of the problems that have arisen. In such cases, prolonged depressive disorders are the result of a weakness in the mechanisms of cortical control over the excessive activity of the tonsils and other components of the “negative brain”. Long-term depressive disorders are characterized by a vicious circle. On the one hand, insufficiency of the orbitofrontal, dorsolateral prefrontal, and temporal structures of the cerebral cortex predisposes to the development of long-term depressive disorders.