Counselling for social anxiety

Social anxiety disorder (social phobia) - Diagnosis and treatment

Diagnosis

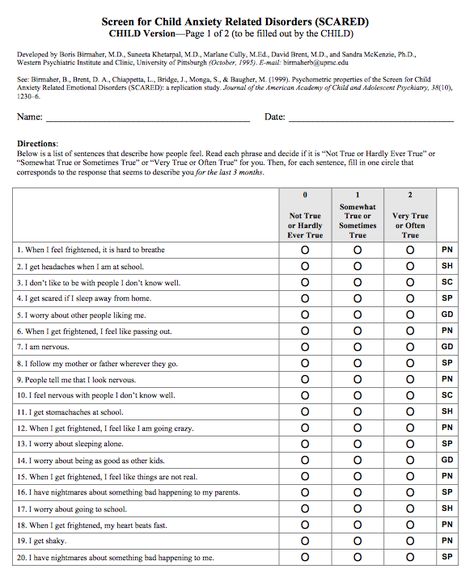

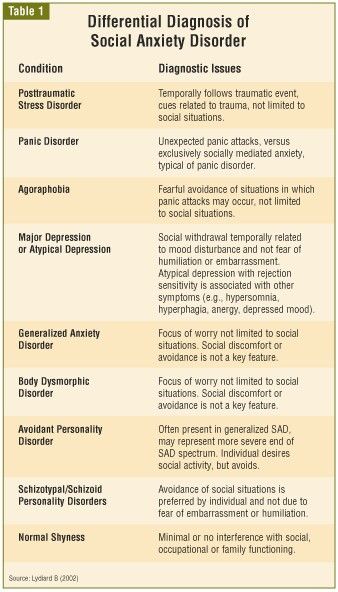

Your health care provider will want to determine whether other conditions may be causing your anxiety or if you have social anxiety disorder along with another physical or mental health disorder.

Your health care provider may determine a diagnosis based on:

- Physical exam to help assess whether any medical condition or medication may trigger symptoms of anxiety

- Discussion of your symptoms, how often they occur and in what situations

- Review of a list of situations to see if they make you anxious

- Self-report questionnaires about symptoms of social anxiety

- Criteria listed in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), published by the American Psychiatric Association

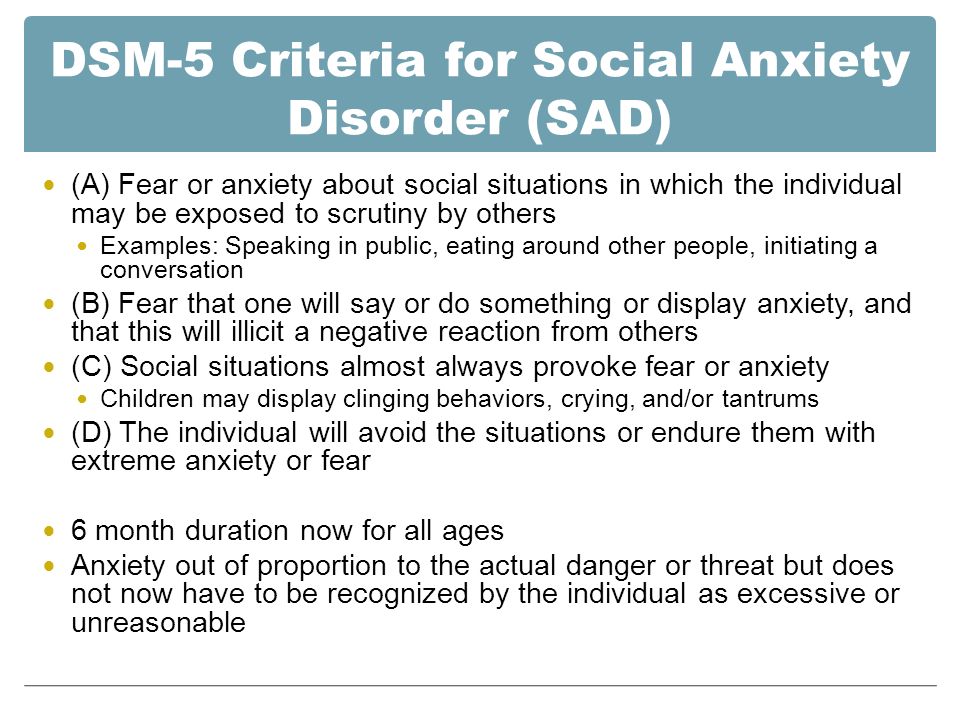

DSM-5 criteria for social anxiety disorder include:

- Persistent, intense fear or anxiety about specific social situations because you believe you may be judged negatively, embarrassed or humiliated

- Avoidance of anxiety-producing social situations or enduring them with intense fear or anxiety

- Excessive anxiety that's out of proportion to the situation

- Anxiety or distress that interferes with your daily living

- Fear or anxiety that is not better explained by a medical condition, medication or substance abuse

Care at Mayo Clinic

Our caring team of Mayo Clinic experts can help you with your social anxiety disorder (social phobia)-related health concerns Start Here

Treatment

Treatment depends on how much social anxiety disorder affects your ability to function in daily life. The most common treatment for social anxiety disorder includes psychotherapy (also called psychological counseling or talk therapy) or medications or both.

Psychotherapy

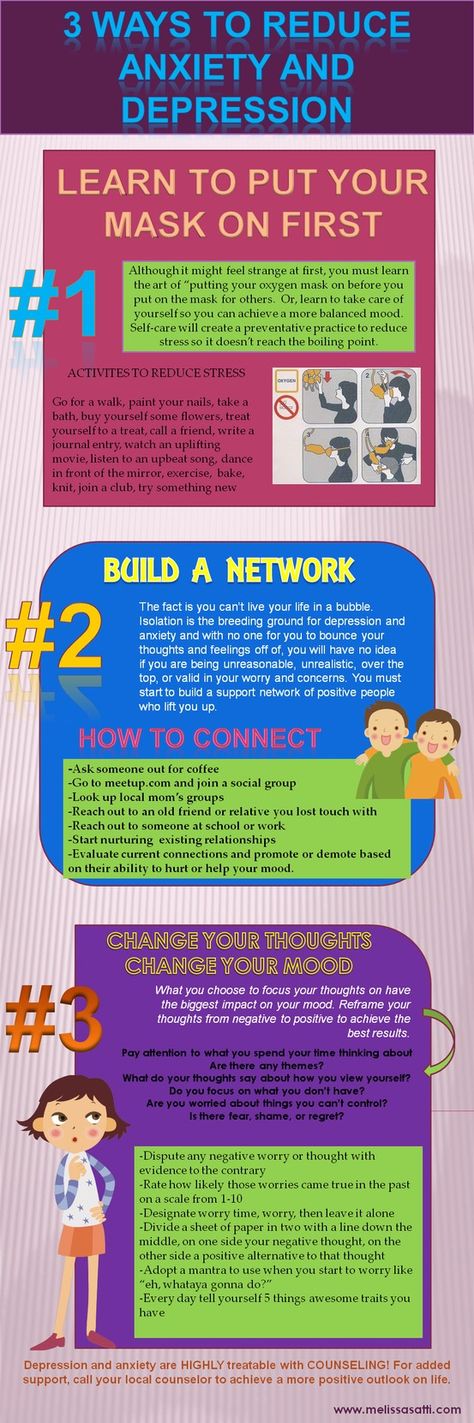

Psychotherapy improves symptoms in most people with social anxiety disorder. In therapy, you learn how to recognize and change negative thoughts about yourself and develop skills to help you gain confidence in social situations.

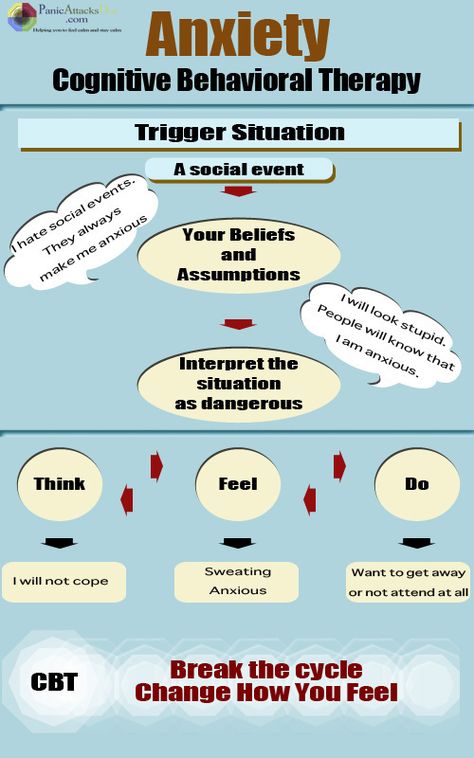

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) is the most effective type of psychotherapy for anxiety, and it can be equally effective when conducted individually or in groups.

In exposure-based CBT, you gradually work up to facing the situations you fear most. This can improve your coping skills and help you develop the confidence to deal with anxiety-inducing situations. You may also participate in skills training or role-playing to practice your social skills and gain comfort and confidence relating to others. Practicing exposures to social situations is particularly helpful to challenge your worries.

First choices in medications

Though several types of medications are available, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) are often the first type of drug tried for persistent symptoms of social anxiety. Your health care provider may prescribe paroxetine (Paxil) or sertraline (Zoloft).

The serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI) venlafaxine (Effexor XR) also may be an option for social anxiety disorder.

To reduce the risk of side effects, your health care provider may start you at a low dose of medication and gradually increase your prescription to a full dose. It may take several weeks to several months of treatment for your symptoms to noticeably improve.

Other medications

Your health care provider may also prescribe other medications for symptoms of social anxiety, such as:

- Other antidepressants. You may have to try several different antidepressants to find the one that's most effective for you with the fewest side effects.

- Anti-anxiety medications. Benzodiazepines (ben-zoe-die-AZ-uh-peens) may reduce your level of anxiety. Although they often work quickly, they can be habit-forming and sedating, so they're typically prescribed for only short-term use.

- Beta blockers. These medications work by blocking the stimulating effect of epinephrine (adrenaline). They may reduce heart rate, blood pressure, pounding of the heart, and shaking voice and limbs. Because of that, they may work best when used infrequently to control symptoms for a particular situation, such as giving a speech. They're not recommended for general treatment of social anxiety disorder.

Stick with it

Don't give up if treatment doesn't work quickly. You can continue to make strides in psychotherapy over several weeks or months. Learning new skills to help manage your anxiety takes time. And finding the right medication for your situation can take some trial and error.

For some people, the symptoms of social anxiety disorder may fade over time, and medication can be discontinued. Others may need to take medication for years to prevent a relapse.

To make the most of treatment, keep your medical or therapy appointments, challenge yourself by setting goals to approach social situations that cause you anxiety, take medications as directed, and talk to your health care provider about any changes in your condition.

Alternative medicine

Several herbal remedies have been studied as treatments for anxiety, but results are mixed. Before taking any herbal remedies or supplements, talk with your health care team to make sure they're safe and won't interact with any medications you take.

More Information

- Social anxiety disorder (social phobia) care at Mayo Clinic

- Cognitive behavioral therapy

- Psychotherapy

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free, and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips and current health topics, like COVID-19, plus expertise on managing health.

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Lifestyle and home remedies

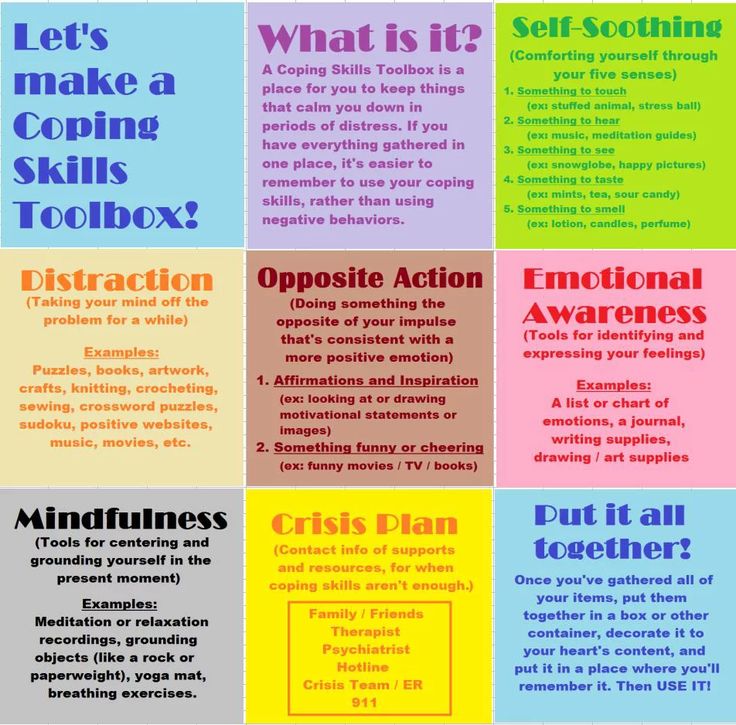

Although social anxiety disorder generally requires help from a medical expert or qualified psychotherapist, you can try some of these techniques to handle situations that are likely to trigger symptoms:

- Learn stress-reduction skills.

- Get physical exercise or be physically active on a regular basis.

- Get enough sleep.

- Eat a healthy, well-balanced diet.

- Avoid alcohol.

- Limit or avoid caffeine.

- Participate in social situations by reaching out to people with whom you feel comfortable.

Practice in small steps

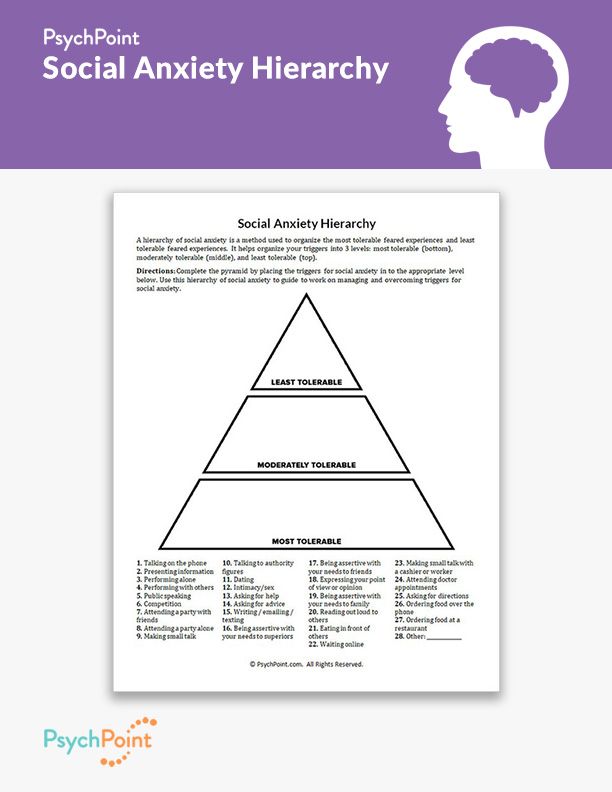

First, consider your fears to identify what situations cause the most anxiety. Then gradually practice these activities until they cause you less anxiety. Begin with small steps by setting daily or weekly goals in situations that aren't overwhelming. The more you practice, the less anxious you'll feel.

Consider practicing these situations:

- Eat with a close relative, friend or acquaintance in a public setting.

- Purposefully make eye contact and return greetings from others, or be the first to say hello.

- Give someone a compliment.

- Ask a retail clerk to help you find an item.

- Get directions from a stranger.

- Show an interest in others — ask about their homes, children, grandchildren, hobbies or travels, for instance.

- Call a friend to make plans.

Prepare for social situations

At first, being social when you're feeling anxious is challenging. As difficult or painful as it may seem initially, don't avoid situations that trigger your symptoms. By regularly facing these kinds of situations, you'll continue to build and reinforce your coping skills.

These strategies can help you begin to face situations that make you nervous:

- Prepare for conversation, for example, by reading about current events to identify interesting stories you can talk about.

- Focus on personal qualities you like about yourself.

- Practice relaxation exercises.

- Learn stress management techniques.

- Set realistic social goals.

- Pay attention to how often the embarrassing situations you're afraid of actually take place.

You may notice that the scenarios you fear usually don't come to pass.

You may notice that the scenarios you fear usually don't come to pass. - When embarrassing situations do happen, remind yourself that your feelings will pass and you can handle them until they do. Most people around you either don't notice or don't care as much as you think, or they're more forgiving than you assume.

Avoid using alcohol to calm your nerves. It may seem like it helps temporarily, but in the long term it can make you feel even more anxious.

Coping and support

These coping methods may help ease your anxiety:

- Routinely reach out to friends and family members.

- Join a local or reputable internet-based support group.

- Join a group that offers opportunities to improve communication and public speaking skills, such as Toastmasters International.

- Do pleasurable or relaxing activities, such as hobbies, when you feel anxious.

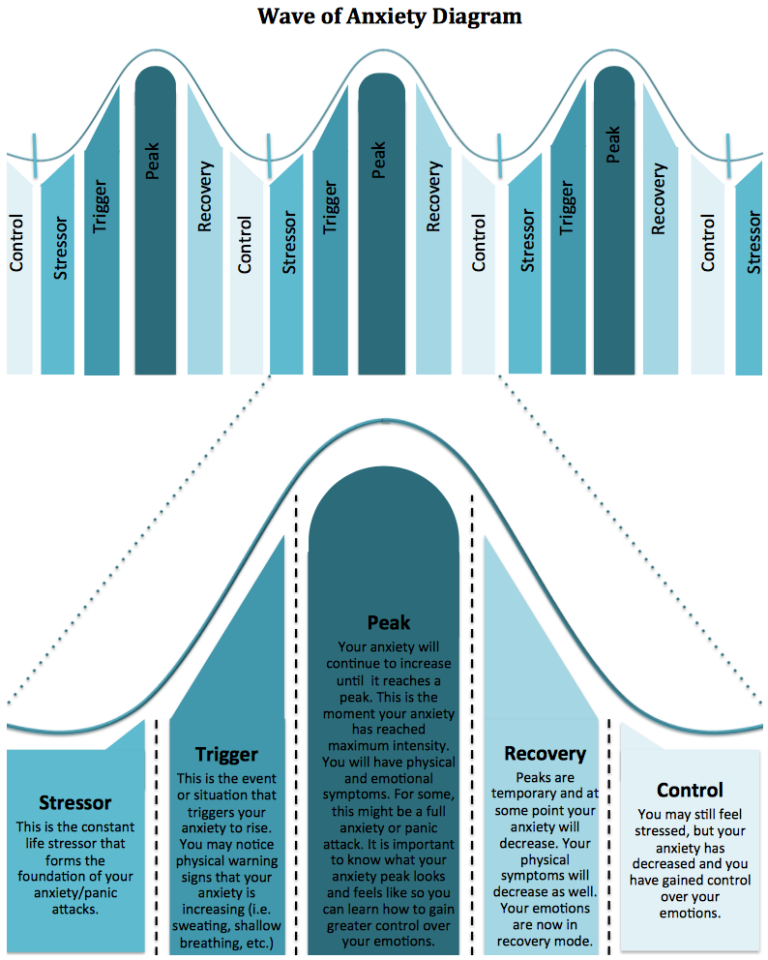

Over time, these coping methods can help control your symptoms and prevent a relapse. Remind yourself that you can get through anxious moments, that your anxiety is short-lived and that the negative consequences you worry about so much rarely come to pass.

Remind yourself that you can get through anxious moments, that your anxiety is short-lived and that the negative consequences you worry about so much rarely come to pass.

Preparing for your appointment

You may see your primary care provider, or your provider may refer you to a mental health professional. Here's some information to help you get ready for your appointment.

What you can do

Before your appointment, make a list of:

- Situations you've been avoiding, especially those that are important to your functioning

- Any symptoms you've been experiencing, and for how long, including any symptoms that may seem unrelated to the reason for your appointment

- Key personal information, especially any significant events or changes in your life shortly before your symptoms appeared

- Medical information, including other physical or mental health conditions with which you've been diagnosed

- Any medications, vitamins, herbs or other supplements you're taking, including dosages

- Questions to ask your health care provider or a mental health professional

You may want to ask a trusted family member or friend to go with you to your appointment, if possible, to help you remember key information.

Some questions to ask your health care provider may include:

- What do you believe is causing my symptoms?

- Are there any other possible causes?

- How will you determine my diagnosis?

- Should I see a mental health specialist?

- Is my condition likely temporary or chronic?

- Are effective treatments available for this condition?

- With treatment, could I eventually be comfortable in the situations that make me so anxious now?

- Am I at increased risk of other mental health problems?

- Are there any brochures or other printed material that I can have? What websites do you recommend?

Don't hesitate to ask other questions during your appointment.

What to expect from your health care provider

Your health care provider or a mental health professional will likely ask you a number of questions. Be ready to answer them to reserve time to go over any points you want to focus on. Your health care provider may ask:

Your health care provider may ask:

- Does fear of embarrassment cause you to avoid doing certain activities or speaking to people?

- Do you avoid activities in which you're the center of attention?

- Would you say that being embarrassed or looking stupid is among your worst fears?

- When did you first notice these symptoms?

- When are your symptoms most likely to occur?

- Does anything seem to make your symptoms better or worse?

- How are your symptoms affecting your life, including work and personal relationships?

- Do you ever have symptoms when you're not being observed by others?

- Have any of your close relatives had similar symptoms?

- Have you been diagnosed with any medical conditions?

- Have you been treated for mental health symptoms or mental illness in the past? If yes, what type of therapy was most beneficial?

- Have you ever thought about harming yourself or others?

- Do you drink alcohol or use recreational drugs? If so, how often?

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

Products & Services

Treatments for Social Anxiety Disorder

Written by WebMD Editorial Contributors

In this Article

- Social Anxiety Therapy

- Medications

It may not be easy at first to seek help for a condition like social anxiety disorder, which can make you reluctant to speak to strangers. But if you're at the point where you avoid social contact and it's started to control your life, you should talk to a mental health professional. There are a lot of treatments that can help.

But if you're at the point where you avoid social contact and it's started to control your life, you should talk to a mental health professional. There are a lot of treatments that can help.

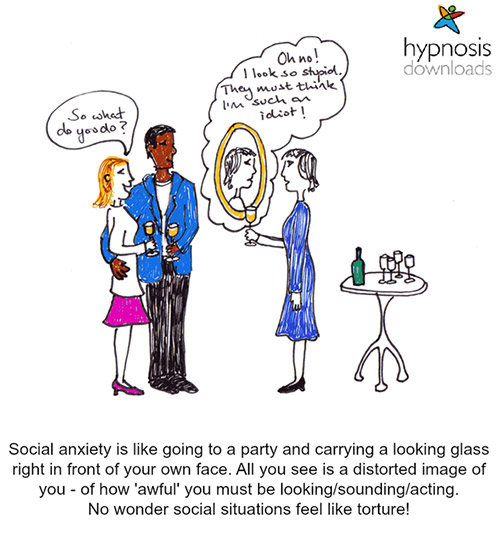

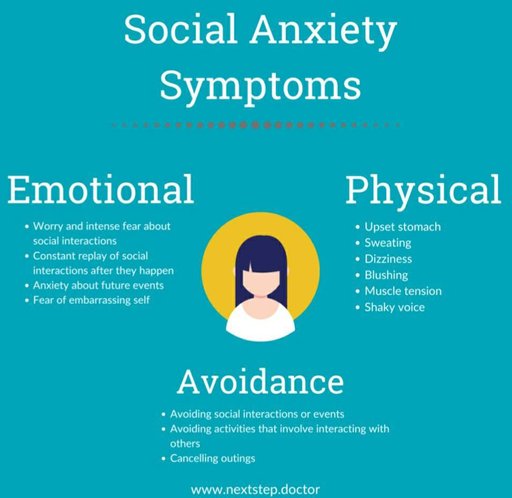

Social anxiety disorder, also called social phobia, causes overwhelming fear of social situations, from parties and dating, to public speaking and eating in restaurants. When you cut yourself off because of social anxiety, you might feel depressed and have low self-esteem. You might have negative or even suicidal thoughts.

If you've been avoiding certain social situations for at least a few months and have been under severe stress because of it, it's time to get treatment.

Social Anxiety Therapy

The best way to treat social anxiety is through cognitive behavioral therapy or medication -- and often both.

You generally need about 12 to 16 therapy sessions. The goal is to build confidence, learn skills that help you manage the situations that scare you most, and then get out into the world.

Teamwork is key in social anxiety therapy. You and your therapist will work together to identify your negative thoughts and start to change them. You'll need to focus on the present instead of what happened in the past.

You might do role-playing and social skills training as part of your therapy. Maybe you'll get lessons in public speaking or learn how to navigate a party of strangers. Between sessions, you'll practice on your own.

A big part of getting better is taking care of yourself. If you exercise, get enough sleep, and limit alcohol and caffeine, you'll be more focused for the mental challenges of therapy.

Medications

Your doctor may suggest antidepressants to treat your social anxiety disorder. For instance, they may prescribe drugs known as SSRIs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors), such as:

- Fluoxetine (Prozac)

- Paroxetine (Paxil)

- Sertraline (Zoloft)

Your doctor may also suggest antidepressants called SNRIs (selective serotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors). Some examples are:

Some examples are:

- Duloxetine (Cymbalta)

- Venlafaxine (Effexor)

Keep in mind that medicine alone won't be a quick fix for your anxiety. You'll have to wait for it to take effect -- 2 to 6 weeks is a good guideline. And it might take a while to figure out side effects and find the right fit. Some people are able to wean off medication after a few months, and others need to stay on it if their symptoms start to come back.

You might find that the first course of treatment eases all of your anxiety. Or it might be a longer journey. But taking those first steps will lead you to a less stressful life.

© 2021 WebMD, LLC. All rights reserved. View privacy policy and trust infoHellam R. Anxiety counseling

purchase

Hellam R. Anxiety counseling

download (1610 kb.)

Available files (1):

| n1.doc | 1610kb. | 12.09.2012 09:16 | download |

- 0022

- Minyakova T.

E. Administrative consulting (Document)

E. Administrative consulting (Document) - Ivanova N.F. Overcoming anxiety and fears in children aged 5-7 (Document)

- Chibisova M.Yu. Psychological counseling: from diagnosis to problem solving (Document)

- Socio-pedagogical counseling of adolescents on the problem of smoking (Document)

- Rumyantseva T.V. Psychological counseling. Diagnostics of relationships in a couple (Document)

- Essay on academic discipline: Psychological counseling on the topic: “Psychological counseling, psychotherapy, psychological correction: general and different (Document)

- Report - Counseling patients before surgery (Abstract)

n1. doc

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ... 27

1 6

Theoretical approaches to the problem of anxiety 6

What is anxiety? 6Anxiety as everyday concept 8

Naming anxiety and the formation of “anxious memories” 10

Biological aspects of anxiety problems 18

Recommended literature 27

28

Genesis Genesis 28

processes that generate or support problems anxiety 30

3 40

General provisions of the eclectic approach 40

Features of working with a client 41

Features of anxiety customers and contract 43

Consulting anxiety problems - main goals 48

4 51

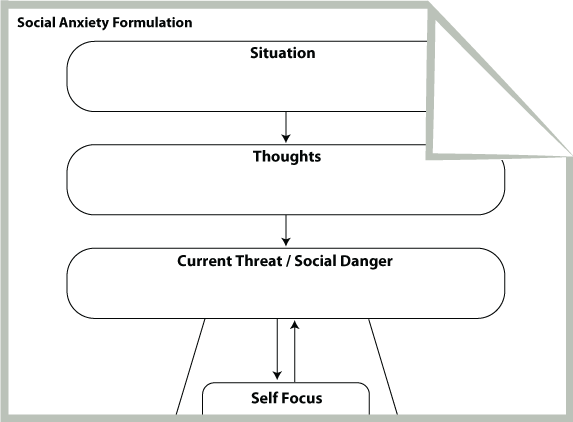

Formulation of anxiety problems 51

Biheviral description and behavioral description and behavioral description and behavior functional analysis 52

Cognitive analysis 57

Case study illustrating behavioral and cognitive analysis 60

Recommended literature 72

5 73

Evaluation in advice on anxiety problems 73

Assessment Methods 73

First evaluating interviews 74

Evaluation of the main areas of the problem based on self -observation 75

Inhaled assessment of the main problems 77

Self -observation 84

Schematic representation of client problems 86

Setting goals and defining an intervention plan 96

Recommended reading 96

6 97 9,0006

Principles of confrontation 97 9,0006

Evaluation of stimulus 99,

Choosing a starting point 101

Selection of confrontation methods 104

Orientation of the client for effective confrontation 104

Planning of therapeutic meeting 107

Complex frequency completion of meetings 109 9000 9004 programs 110

Additional notes on working with anxiety 111

Traditional methods 113

Recommended reading 119

7 120

Attacks of panic and related phobias 120

Cases of panic and their description 120

consequences of panic 123

Assessment of panic and related phobias 129

Additional recommendations on the use of confrontation methods 133,

Self -regulation during conference with alarming situations with alarming situations 144

Intervention: cognitive restructuring 152

Fear of illness 169

Recommended reading 174

8 175

Concern, social anxiety and other types of spread of anxiety problem 175

Concerned potential dangers in the future 175

Unpressiveness, inconstancy and ineffective solution to problems 178

Dysfunctional attitudes 181

Inability to relax 186 9000 9000

diffuse distress 197

Recommended reading 208

9 209

Difficult questions and ending counseling relationships 209

Difficulties of orientation of the client 209 9000

Obstacles for adequate assessment 211

What can interfere with the success of intervention 218

Consulting 222

Recommended literature 223

Appendix A 225

Appendix B 227 9000 1 Theoretical Approaches to Anxiety

Effective anxiety counseling requires a good orientation in theoretical approaches. The first chapter analyzes the content of the term "anxiety" as a linguistic concept and substantiates the difference between the phenomena, called anxiety, and causing anxiety. Consideration of the biological aspects of anxiety concludes the chapter.

The first chapter analyzes the content of the term "anxiety" as a linguistic concept and substantiates the difference between the phenomena, called anxiety, and causing anxiety. Consideration of the biological aspects of anxiety concludes the chapter.

What is anxiety?

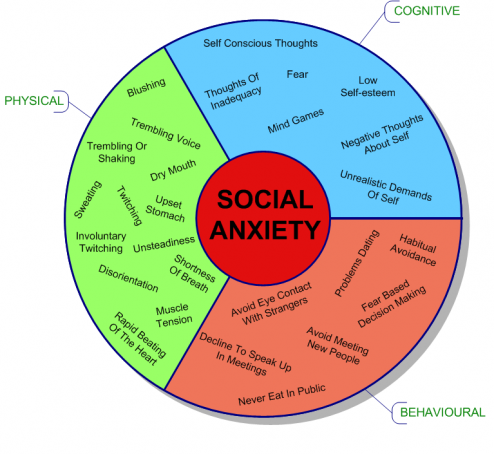

Usually we use the word "anxiety" without caring about its exact meaning. We can say this about someone who does not himself consider that his behavior betrays anxiety. Sometimes we use this term to explain why we behaved in a certain way (“probably because of anxiety”). In my opinion, one should not imagine that there is a special essence - anxiety - and its observed manifestations. In everyday usage, the content of this word refers to the complex dynamic interaction between a person and a situation. The forms of such interaction can be (1) behavioral and physiological reactions caused directly by the situation; (2) assessment of reactions and their consequences; (3) the person's intentions in a particular situation; and (4) assessing the resources available in a given situation. The situation itself can be unpleasant (or signal the possibility of unpleasant consequences), but at the same time, the anxiety provoked by it does not arise automatically, but depending on how prone a person is to anticipating troubles. What matters here is that man feels , however, as noted above, the term can also be used in cases where the person himself does not report his experiences.

The situation itself can be unpleasant (or signal the possibility of unpleasant consequences), but at the same time, the anxiety provoked by it does not arise automatically, but depending on how prone a person is to anticipating troubles. What matters here is that man feels , however, as noted above, the term can also be used in cases where the person himself does not report his experiences.

Recognizing that the everyday concept of "anxiety" describes not only a person's own experiences, it should be assumed that such a set of psychological or biological factors that uniquely determine it can hardly be found. Anxiety cannot be considered as an exclusively objective state of the body. Different people can use it differently, and the same person can use it differently on different occasions. In short, the inaccuracy and approximateness of the content of the word "anxiety" and derivative terms make it possible to apply them to a wide range of phenomena. If necessary, a person can give a more thorough assessment of the situation, take into account their own intentions, the attitude of others, all kinds of experiences and feelings.

Table 1.1 Generalities between words denoting anxiety

Components of negative experience described by a terminological sequence with poles "tension" - "horror"

Awareness of imminent danger or harm, regardless of whether its sources can actually be identified

Experience of physical sensations, predominantly associated with activation of the autonomic nervous system

Strong need for a safe haven

Decreased fine motor control

Disturbing or unpleasant thoughts that are difficult to control

Inability to think logically or act in a coordinated manner especially in non-routine, conflict or threatening situations

NB: "Anxiety" other determined based on (1) observable behavior corresponding to the above characteristics; (2) the emergence of feelings of tension or insecurity in a communication situation; and (3) other features such as facial expression or tone of voice.

The commonality between anxiety words is shown in Table 1. 1. The breadth of the range of values indicates a variety of psychological and biological factors that determine anxiety. Therefore, virtually all areas of theoretical psychology - teachings about innate biological defenses, stress models, self-awareness, social assessment, behavior, cognitive abilities, problem solving, learning, etc. - can be adequate in describing anxiety.

1. The breadth of the range of values indicates a variety of psychological and biological factors that determine anxiety. Therefore, virtually all areas of theoretical psychology - teachings about innate biological defenses, stress models, self-awareness, social assessment, behavior, cognitive abilities, problem solving, learning, etc. - can be adequate in describing anxiety.

Anxiety as an everyday concept

A person, calling himself anxious, not only tries to define his state of mind, but also strives for certain goals in social interaction. The unpleasantness associated with anxiety draws attention to itself and thus leads to the recognition of a problem. The inability to recognize one's own "anxiety" makes a person unprepared for the development of the situation. Knowing that he is “anxious” forces others to consider the possibility of an unproductive interaction. On the other hand, the anxious enlists support. It is no coincidence that we have the most confidence in the calmest people - such as the pilots of passenger planes. For them, saying "I'm worried" means "here's something I haven't experienced before and haven't thought about what to do about it yet." Judging by the voice we hear, no help is required.

For them, saying "I'm worried" means "here's something I haven't experienced before and haven't thought about what to do about it yet." Judging by the voice we hear, no help is required.

Further, we believe that person is learning to name and talk about anxiety. This means that the verbal/cognitive process observed here is to some extent independent of the processes that generate experiences that we define as anxiety. Without a doubt, when we master speech and related concepts, verbal information can act as a powerful anxiety stimulus. Information about what can only happen can terrify us. As we proceed, we will see that the control of biologically based responses by processes of a symbolic nature (such as inference, speculation, or interpretation) can be seen as the cause of anxiety becoming a problem.

Verbal and cognitive abilities that allow us to name our emotions and relate to them from the point of view of other people develop under the influence of family subculture and the social environment in general. Parents differ, for example, in the degree of insistence with which they draw their children's attention to potential threats (" Never never talk to strangers") or to physical sensations and feelings ("You are upset about something - so excited, excited" ). Parental instructions and real life experiences determine the child's sensitivity to those threats that our culture considers significant. Along with biologically inherited fears (fear of the dark, heights, eye contact, small animals, etc.), there are constant sources of anxiety. They concern our physical survival (death, illness, material security) as well as fear of losing others, fear of negative evaluation and rejection by others. Apparently, significant individual differences in how much a person is willing or able to admit to such fears are associated with the "emotional education" received in childhood. For example, it is known that the emotional upbringing of boys and girls differs.

Parents differ, for example, in the degree of insistence with which they draw their children's attention to potential threats (" Never never talk to strangers") or to physical sensations and feelings ("You are upset about something - so excited, excited" ). Parental instructions and real life experiences determine the child's sensitivity to those threats that our culture considers significant. Along with biologically inherited fears (fear of the dark, heights, eye contact, small animals, etc.), there are constant sources of anxiety. They concern our physical survival (death, illness, material security) as well as fear of losing others, fear of negative evaluation and rejection by others. Apparently, significant individual differences in how much a person is willing or able to admit to such fears are associated with the "emotional education" received in childhood. For example, it is known that the emotional upbringing of boys and girls differs.

The distinction I propose between the worldly concept of emotion and the phenomena that correspond to it has some interesting consequences. Sometimes what a person says about the presence / absence of a threat does not correspond to his behavior. One person may appear shy and aloof but deny having anxiety. Another may constantly worry about what might happen, but do nothing about it, and consider his excitement meaningless. A third may feel nausea or palpitations in really stressful situations, but deny that the situation is threatening or deny that they are anxious. These examples highlight the complexity of anxiety problems. The discrepancy between verbal/cognitive expressions of "anxiety" and other behavioral and physiological manifestations of emotions, recognized by most researchers, is rather difficult to give a theoretical explanation. Many factors can be considered, but at this stage we will turn to a description of the consequences that follow from the distinction between "naming an emotion" and "what is called."

Sometimes what a person says about the presence / absence of a threat does not correspond to his behavior. One person may appear shy and aloof but deny having anxiety. Another may constantly worry about what might happen, but do nothing about it, and consider his excitement meaningless. A third may feel nausea or palpitations in really stressful situations, but deny that the situation is threatening or deny that they are anxious. These examples highlight the complexity of anxiety problems. The discrepancy between verbal/cognitive expressions of "anxiety" and other behavioral and physiological manifestations of emotions, recognized by most researchers, is rather difficult to give a theoretical explanation. Many factors can be considered, but at this stage we will turn to a description of the consequences that follow from the distinction between "naming an emotion" and "what is called."

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 ... 27

the content of the concept and the main directions of study.

Read the text of the research paper for free in the CyberLeninka electronic library

Read the text of the research paper for free in the CyberLeninka electronic library SOCIAL ANXIETY: THE CONTENT OF THE CONCEPT AND MAIN DIRECTIONS OF STUDY. PART 1

I. V. Nikitina, A. B. Kholmogorova

Moscow Research Institute of Psychiatry of Roszdrav

The concept of social anxiety

Currently, the phenomenon of social anxiety has become the subject of intensive empirical research in foreign clinical psychology. Despite the fact that anxiety is a traditional subject of research in Russian psychology, studies of such a common form as social anxiety are extremely few [2, 3].

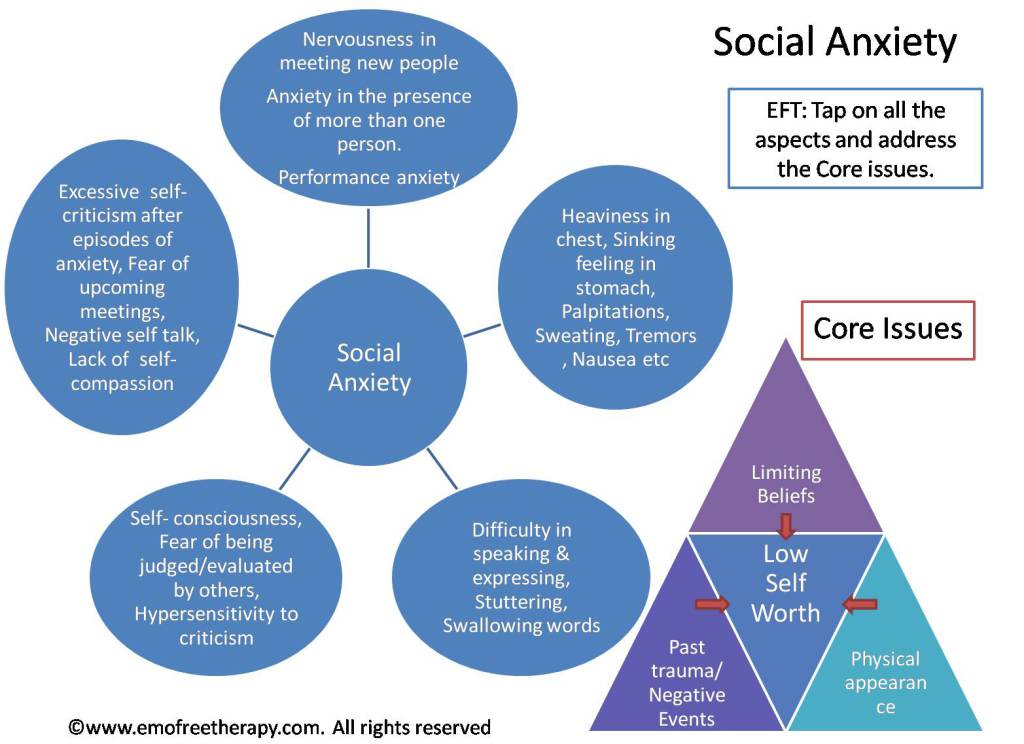

The term social anxiety is commonly understood as anxiety triggered by various situations of social interaction. This concept is quite broad and includes a number of phenomena - from the mildest form - shyness to such a serious disorder as social phobia. The symptoms of shyness, social anxiety, and social avoidance were known as early as ancient Greece and were described in the time of Hippocrates. Shyness does not have a clear definition and is described by different researchers in different ways: as anxiety and discomfort in social situations, especially in cases involving assessment by authority figures [9], discomfort and inhibition in interpersonal situations [14] and as a fear of negative evaluation [5]. Shyness, in the form of a certain constraint, constraint in certain social situations, is characteristic (familiar) for most people. Thus, according to D.C.Beidel and S.M.Tumer [4], 90% of college students reported that at one time or another in their lives they experienced shyness.

Shyness does not have a clear definition and is described by different researchers in different ways: as anxiety and discomfort in social situations, especially in cases involving assessment by authority figures [9], discomfort and inhibition in interpersonal situations [14] and as a fear of negative evaluation [5]. Shyness, in the form of a certain constraint, constraint in certain social situations, is characteristic (familiar) for most people. Thus, according to D.C.Beidel and S.M.Tumer [4], 90% of college students reported that at one time or another in their lives they experienced shyness.

The term "social phobia" (phobie des situations sociales) was first proposed by PJanet in 1903 [17]. As a separate form of phobias, it was first identified at the end of 1960s, but as a separate disorder appeared in the third edition of the DSM. In the DSM-I and DSM-II, all phobias were included in one group, the basis of this classification was the psychoanalytic idea that all phobic symptoms are the result of repressed instinctual drives. Social phobia was singled out as a separate diagnostic category in the ICD

Social phobia was singled out as a separate diagnostic category in the ICD

revision 10. Prior to this distinction, this disorder was erroneously considered extremely rare, which led some authors [20] to call it "an anxiety disorder that has hitherto been unfairly neglected." Social phobia has a very clear definition: for example, in DSM-IV, this term is understood as “a pronounced and persistent fear of one or more social situations in which a person is exposed to, encounters strangers or a possible assessment (examination, probing look) by other people around ". ICD-10 understands this disorder as the fear of being noticed by others in relatively small groups of people, which is accompanied by a pronounced avoidance of these situations. Patients with social phobia may experience fear of one or two social situations (specific or limited subtype) or fear of most social contact with others (generalized subtype). It can be found that the descriptions of shyness and social phobia are largely similar, and many studies are devoted to the question of the relationship between these two concepts, which will be discussed below. It should also be noted that by the term "social anxiety" many authors mean specifically social phobia: for example, the DSM-IV Working Group on Anxiety Disorders proposed replacing the name of social phobia with social anxiety disorder in order to emphasize the seriousness of this problem, which the old name " social phobia”, according to the working group, does not correspond. At the same time, a number of researchers express doubts about the need to single out such a diagnostic category (classification unit) as social phobia, considering it as a concomitant symptom of other disorders. So, V.N. Krasnov [1], discussing the question of the expediency of separating social phobia into an independent category, expresses the opinion that “social phobia” is

It should also be noted that by the term "social anxiety" many authors mean specifically social phobia: for example, the DSM-IV Working Group on Anxiety Disorders proposed replacing the name of social phobia with social anxiety disorder in order to emphasize the seriousness of this problem, which the old name " social phobia”, according to the working group, does not correspond. At the same time, a number of researchers express doubts about the need to single out such a diagnostic category (classification unit) as social phobia, considering it as a concomitant symptom of other disorders. So, V.N. Krasnov [1], discussing the question of the expediency of separating social phobia into an independent category, expresses the opinion that “social phobia” is

"nothing more than the actualization of psychasthenic features within the framework of neurotic disorders or, more often, at the initial stages of endogenomorphic depression, where anxious affective components remain dominant" [1]. Thus, it is possible to single out two positions of researchers and, accordingly, two directions in the study of social anxiety:

Thus, it is possible to single out two positions of researchers and, accordingly, two directions in the study of social anxiety:

1) social anxiety as a symptom of various disorders;

2) social anxiety (social phobia) as a separate nosological unit.

Epidemiological data

Studies on the epidemiology of social anxiety are conducted primarily in the USA and show an increase in social anxiety in both the general population and clinical samples. Thus, in a study conducted by P.A. Pilkonis and P. GZimbardo in 1979 [24], on a sample of 817 students of higher educational institutions (colleges), more than 40% of respondents described themselves as shy, of which 63% noted that this feature makes it difficult for them to socialize. functioning. More recent studies in this area have shown that there is an upward trend in this phenomenon, so, according to the same researcher, in 19In 1997, already 50% of the respondents admitted that they were shy.

The Stanford epidemiological study obtained the following data: when asked whether the respondents were shy (now or in the past), the majority (about 84%) answered in the affirmative. Some researchers explain such high rates by the popularization of this concept, a large number of references to it in the media.

Some researchers explain such high rates by the popularization of this concept, a large number of references to it in the media.

Such a high prevalence makes it possible to consider social anxiety not only as a psychological construct, but also as a social phenomenon. Thus, many researchers associate the growth of this phenomenon with such values of modern culture as the cult of success and personal achievements, increased personal responsibility for failure [33].

Social phobia is the third most common mental disorder in the United States, after depression and alcoholism (its prevalence, according to various sources, ranges from 2.4% [25] to 13.3% [14]).

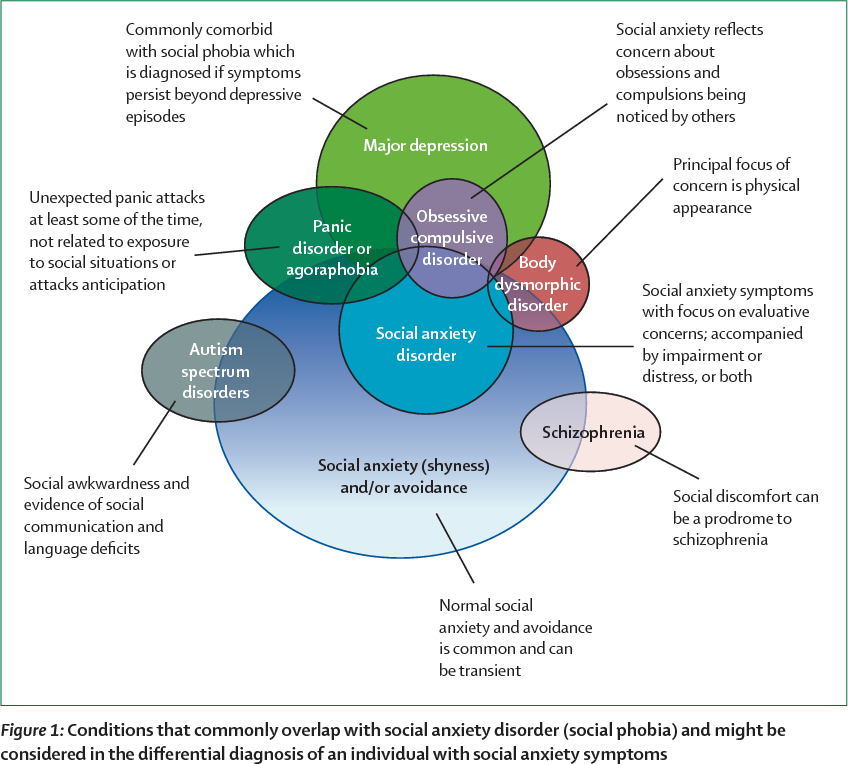

Comorbidity with DSM-IV Axis I disorders

According to various data, from 50 to 80% of patients suffering from social phobia have another mental disorder [19, 22, 27]. Thus, according to the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) [27], 69% of patients with social phobia suffered from another mental disorder throughout their lives (59% - a simple phobia, 45% - agoraphobia, 19% - alcohol addiction, 17% - depression and 13% - drug addiction), despite the fact that in 77% of cases (and according to M. V. Van Amerigen et al. [31] - in 81.7% of cases) social phobia preceded comorbid disorder. Most often, social phobia is comorbid with depressive disorders, other anxiety disorders and substance dependence, as well as eating disorders. In the case of comorbidity with depression, social phobia proceeds in an extremely severe form and significantly increases the risk of suicidal attempts (with isolated social phobia it is 6%, while in the case of comorbidity with depression 45%) [19, 32].

V. Van Amerigen et al. [31] - in 81.7% of cases) social phobia preceded comorbid disorder. Most often, social phobia is comorbid with depressive disorders, other anxiety disorders and substance dependence, as well as eating disorders. In the case of comorbidity with depression, social phobia proceeds in an extremely severe form and significantly increases the risk of suicidal attempts (with isolated social phobia it is 6%, while in the case of comorbidity with depression 45%) [19, 32].

Three studies examining eating disorders found the following data: the prevalence of social phobia among patients with eating disorders (anorexia and bulimia nervosa) ranged from 23.8 to 55% [10, 18, 21].

The comorbidity of social phobia with alcoholism deserves special mention. Due to the well-known anxiolytic effect of alcohol, patients with social phobia often resort to it to reduce anxiety. Studies conducted on the general population indicate that for patients with social phobia, the risk of developing alcohol dependence increases by 2-3 times compared with the normal group. The National Comorbidity Survey found that 24% of patients with social phobia also suffer from alcohol dependence during their lifetime. In turn, the prevalence of social phobia in persons suffering from alcohol dependence was 19% among men and 30% among women [17]. All studies confirm that the onset of social phobia occurred in childhood and adolescence and preceded alcoholization in at least two-thirds of cases.

The National Comorbidity Survey found that 24% of patients with social phobia also suffer from alcohol dependence during their lifetime. In turn, the prevalence of social phobia in persons suffering from alcohol dependence was 19% among men and 30% among women [17]. All studies confirm that the onset of social phobia occurred in childhood and adolescence and preceded alcoholization in at least two-thirds of cases.

Comorbidity with DSM-IV Axis II Disorders

Social phobia is most commonly comorbid with avoidant personality disorder (avoidant personality disorder is considered by some to be only the most severe form of social phobia) and obsessive-compulsive personality disorder. According to S.M. Turner et al. [29] 22% of patients with social phobia meet the criteria for a diagnosis of avoidant personality disorder. In these cases, social phobia is much more severe and has a significant negative impact on functioning (and requires more time to heal). Approximately 13% of patients with social phobia meet the criteria for a diagnosis of obsessive-compulsive personality disorder [29]. At the same time, 48.5% of patients with social phobia have obsessive-compulsive character traits - overzealousness, perfectionism, increased0006

At the same time, 48.5% of patients with social phobia have obsessive-compulsive character traits - overzealousness, perfectionism, increased0006

responsibility, meticulousness, rigidity in relation to rules and regulations.

Consequences of the disease

According to researchers, patients with social phobia have more suicidal thoughts and attempt suicide more often than healthy subjects. They are more likely to take alcohol and anxiolytics to reduce anxiety [4]. This disorder significantly limits opportunities for professional and educational activities, and often leads to complete disability and social isolation. For example, according to S.M. Turner et al. [29] 91% of patients with social phobia reported their academic failure, which they blamed on their social fears. According to the same researchers, 80% of patients with social phobia admitted that this disorder significantly worsens their interpersonal relationships. According to S.A.Safren et al. [26] patients with social phobia rate their quality of life as extremely low. Even the mildest form of social anxiety, shyness, has negative consequences for professional life and interpersonal relationships. So, D.C. Beidel and S.M. Turner [4] in a long-term project studied how the life of shy students developed and found that shy men become fathers on average 3 years later than non-shy ones, and also that shyness has a negative impact on professional career both men and women.

Even the mildest form of social anxiety, shyness, has negative consequences for professional life and interpersonal relationships. So, D.C. Beidel and S.M. Turner [4] in a long-term project studied how the life of shy students developed and found that shy men become fathers on average 3 years later than non-shy ones, and also that shyness has a negative impact on professional career both men and women.

Relationship between the concepts of "anxiety - social phobia"

A number of studies in the field of social anxiety are devoted to how the concepts of shyness and social phobia correlate with each other. Many researchers note that the differences between them are more quantitative than qualitative. So, S.M. Turner et al. [28], comparing these concepts, identify the following common characteristics for them: negative beliefs about social interaction, increased physiological excitability, the desire to avoid social situations, and a lack of social skills. The differences, in their opinion, lie in the lower prevalence of social phobia, more severe consequences and later onset. Let us now consider the parameters in which shyness differs from social phobia. First of all, it concerns the prevalence of these phenomena (shyness is much more common than social phobia).

Let us now consider the parameters in which shyness differs from social phobia. First of all, it concerns the prevalence of these phenomena (shyness is much more common than social phobia).

Differences also lie in the fact that shyness is often a transient condition, while social phobia is characterized by a chronic

course. Although both of these conditions are associated with emotional and social difficulties, it is clear that people suffering from social phobia are more maladjusted and experience significantly more distress.

Despite the fact that the connection between these concepts is obvious, the nature of this connection is still not entirely clear. There are several points of view on the relationship between the concepts of "shyness", "social anxiety" and "social phobia", often polar - from the assumption of B.J. Carducci [6] that these are two completely different concepts (shyness is not a disorder, but a non-pathological character trait , in contrast to social phobia and avoidant personality disorder), to the hypothesis of R. M. Rapee [25] about the identity of these concepts. According to the third hypothesis, which is shared by many researchers, social phobia is an extreme degree of shyness. For example, L. Henderson and P. Zimbardo [14] describe shyness as ranging from mild social alertness to completely paralyzing social phobia. There is also a point of view that shyness is a more heterogeneous category, which may overlap with mild cases of social phobia, or may go beyond it. The D.W.McNeil model [23], which is shared by many researchers, suggests that shyness and social phobia are (located) at different points on the social anxiety intensity continuum, where shyness is located on the segment from normal to pathological anxiety, then in turn follow: non-generalized social anxiety , generalized social anxiety, and finally avoidant personality disorder at its extreme.

M. Rapee [25] about the identity of these concepts. According to the third hypothesis, which is shared by many researchers, social phobia is an extreme degree of shyness. For example, L. Henderson and P. Zimbardo [14] describe shyness as ranging from mild social alertness to completely paralyzing social phobia. There is also a point of view that shyness is a more heterogeneous category, which may overlap with mild cases of social phobia, or may go beyond it. The D.W.McNeil model [23], which is shared by many researchers, suggests that shyness and social phobia are (located) at different points on the social anxiety intensity continuum, where shyness is located on the segment from normal to pathological anxiety, then in turn follow: non-generalized social anxiety , generalized social anxiety, and finally avoidant personality disorder at its extreme.

In the last decade, several studies have been conducted to empirically determine how shyness and social phobia are related. Let us dwell in more detail on three studies devoted to this problem. All of them were conducted on a non-clinical sample (college students) and, to one degree or another, were undertaken in order to confirm or refute the D.W. McNeil continuum model. The studies that will be discussed below are quite similar in design - the subjects were divided into groups in accordance with the scores they received when completing the Revised Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale (RCBS) [8]. This technique is a "first choice technique" for measuring shyness and measures its affective and behavioral aspects. The high-shy group and the normal group were compared with each other on different indicators. D.A.Chavira et al. [7] obtained the following data: in the group that received high scores on indicators of shyness, social phobia was significantly more common (49and 18%), especially its generalized subtype (fear of three or more social situations - a more severe type of social phobia), these students were more likely to have symptoms of depression (24% and 13%).

All of them were conducted on a non-clinical sample (college students) and, to one degree or another, were undertaken in order to confirm or refute the D.W. McNeil continuum model. The studies that will be discussed below are quite similar in design - the subjects were divided into groups in accordance with the scores they received when completing the Revised Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale (RCBS) [8]. This technique is a "first choice technique" for measuring shyness and measures its affective and behavioral aspects. The high-shy group and the normal group were compared with each other on different indicators. D.A.Chavira et al. [7] obtained the following data: in the group that received high scores on indicators of shyness, social phobia was significantly more common (49and 18%), especially its generalized subtype (fear of three or more social situations - a more severe type of social phobia), these students were more likely to have symptoms of depression (24% and 13%).

Avoidant personality disorder was significantly more common in the highly shy group (14% and 4%). Subjects with a high level of shyness without social phobia differed from subjects with social phobia in terms of the degree of maladjustment in professional (institute, work) and social areas. The data obtained are generally consistent with the proposed model, in which a high level of shyness is an indicator of greater mental distress, however, the authors draw attention to the fact that half of the subjects with high scores in shyness do not suffer from social phobia. Such data, from the point of view of the authors, can be interpreted as follows: there are a number of factors (possibly cognitive and behavioral) that protect shy people from getting social phobia. It seems promising in the future to study these factors acting as buffers or protectors.

Subjects with a high level of shyness without social phobia differed from subjects with social phobia in terms of the degree of maladjustment in professional (institute, work) and social areas. The data obtained are generally consistent with the proposed model, in which a high level of shyness is an indicator of greater mental distress, however, the authors draw attention to the fact that half of the subjects with high scores in shyness do not suffer from social phobia. Such data, from the point of view of the authors, can be interpreted as follows: there are a number of factors (possibly cognitive and behavioral) that protect shy people from getting social phobia. It seems promising in the future to study these factors acting as buffers or protectors.

In 2003, N.A. Heiser et al. [12] examined 200 students at the University of Maryland and obtained the following data: the prevalence of social phobia among shy people is 18%, which differs significantly from the data of the study described above. This large variation in numbers across studies is due to differences in the criteria for identifying a group with high rates of shyness, that is, in the last study, fewer scores were required for inclusion in the group. However, here again the fact was confirmed that the number of people suffering from social phobia is significantly higher among the shy than among the non-shy (18% and 3%, respectively). This study also found a direct correlation between the severity of shyness and social phobia (the higher the level of shyness, the higher the likelihood of a diagnosis of social phobia). However, some rather unexpected data were also obtained: 15% of those surveyed with diagnosed social phobia did not receive high scores in terms of shyness. Based on the data obtained, the authors suggest that the relationship between these concepts is not so direct as to argue that social phobia is only an extreme degree of shyness. This study also found that two-thirds of the shy group met criteria for DSM-IV Axis I and II disorders (such as anxiety, depressive disorders, personality disorders - especially avoidant), while the non-shy group had significantly lower scores ( 18.

This large variation in numbers across studies is due to differences in the criteria for identifying a group with high rates of shyness, that is, in the last study, fewer scores were required for inclusion in the group. However, here again the fact was confirmed that the number of people suffering from social phobia is significantly higher among the shy than among the non-shy (18% and 3%, respectively). This study also found a direct correlation between the severity of shyness and social phobia (the higher the level of shyness, the higher the likelihood of a diagnosis of social phobia). However, some rather unexpected data were also obtained: 15% of those surveyed with diagnosed social phobia did not receive high scores in terms of shyness. Based on the data obtained, the authors suggest that the relationship between these concepts is not so direct as to argue that social phobia is only an extreme degree of shyness. This study also found that two-thirds of the shy group met criteria for DSM-IV Axis I and II disorders (such as anxiety, depressive disorders, personality disorders - especially avoidant), while the non-shy group had significantly lower scores ( 18. 3%). Based on the data obtained, the authors conclude that shyness is associated with a wide range of different forms of psychopathology, and not only with social phobia, as claimed.0006

3%). Based on the data obtained, the authors conclude that shyness is associated with a wide range of different forms of psychopathology, and not only with social phobia, as claimed.0006

was expected earlier. The fact that Axis I and II disorders are more common among shy people is explained by the authors as follows: perhaps shyness is one of the manifestations of some property of temperament (for example, neuroticism) that is associated with differences in vulnerability to psychopathology. As a possible explanation for why shy people are more vulnerable to various kinds of mental disorders, the authors suggested that shyness may be a consequence, rather than a cause, of psychopathology, a consequence of disorders such as depression, anxiety disorders, avoidant personality disorder, etc.

Another study [13] in this area aimed to identify those parameters (symptoms, daily functioning, quality of life, as well as social skills, anxiety and physiological symptoms during the experiment, during which participants were asked to enter into conversation) in which generalized social phobia differs from shyness. The group with social phobia noted a significantly wider range of social fears, avoidance of social situations, negative thoughts, as well as more physiological symptoms than the group with high rates of shyness, which, in turn, significantly differed from the norm group in the same indicators. At the same time, all groups of symptoms were more pronounced in the sample of patients with social phobia. The high shyness group differed from the social phobia group in the degree of maladjustment in daily life and a higher quality of life, which is consistent with many other studies in this area. The group with high levels of shyness was also found to be much more heterogeneous than the group with social phobia. So, despite the fact that the subjects noted a high level of shyness, during a diagnostic interview, one third of the group with a high level of shyness did not recognize the presence of social fears. The authors explain such results by the fact that the shy group includes those individuals who are not afraid of social situations, but do not strive for them and prefer loneliness, which corresponds to the division of shy people into introverts who prefer loneliness and extroverts proposed by P.

The group with social phobia noted a significantly wider range of social fears, avoidance of social situations, negative thoughts, as well as more physiological symptoms than the group with high rates of shyness, which, in turn, significantly differed from the norm group in the same indicators. At the same time, all groups of symptoms were more pronounced in the sample of patients with social phobia. The high shyness group differed from the social phobia group in the degree of maladjustment in daily life and a higher quality of life, which is consistent with many other studies in this area. The group with high levels of shyness was also found to be much more heterogeneous than the group with social phobia. So, despite the fact that the subjects noted a high level of shyness, during a diagnostic interview, one third of the group with a high level of shyness did not recognize the presence of social fears. The authors explain such results by the fact that the shy group includes those individuals who are not afraid of social situations, but do not strive for them and prefer loneliness, which corresponds to the division of shy people into introverts who prefer loneliness and extroverts proposed by P. Zimbardo [34]. who strive to communicate with others, but do not have a sufficient level of social skills for this, and also suffer from cognitive distortions regarding social situations. From our point of view, such data can rather be explained by the heterogeneity of the concept of shyness, which is also reflected in the measuring instruments: in some of them, the emphasis is on avoidance behavior, which makes it difficult to differentiate the two groups described above, in others, on emotional experience in the form of

Zimbardo [34]. who strive to communicate with others, but do not have a sufficient level of social skills for this, and also suffer from cognitive distortions regarding social situations. From our point of view, such data can rather be explained by the heterogeneity of the concept of shyness, which is also reflected in the measuring instruments: in some of them, the emphasis is on avoidance behavior, which makes it difficult to differentiate the two groups described above, in others, on emotional experience in the form of

fear of negative evaluation and rejection, which makes it possible to differentiate between introverts and shy extroverts. Another important difference was obtained during the conduct of the behavioral task. Although both groups reported high anticipatory anxiety before the task and high task anxiety, subjects from the high shyness group were more effective at completing tasks and had better skills. The researchers suggested that perhaps this quality of the subjects (to act despite anxiety) with a high level of shyness, but without social phobia, explains their lower maladjustment and higher quality of life. As for the physiological symptoms, according to these indicators (heart rate, sweating), the group of patients with social phobia did not differ in any way from the other two groups, however, subjectively they noted more arousal than they actually experienced. This confirms our conclusion about the importance of separating the behavioral symptoms of anxiety in the form of avoidance and the emotional symptoms in the form of various social fears. Apparently, the most destructive for the quality of life and social adaptation is precisely the severity of avoidant behavior in various social situations.

As for the physiological symptoms, according to these indicators (heart rate, sweating), the group of patients with social phobia did not differ in any way from the other two groups, however, subjectively they noted more arousal than they actually experienced. This confirms our conclusion about the importance of separating the behavioral symptoms of anxiety in the form of avoidance and the emotional symptoms in the form of various social fears. Apparently, the most destructive for the quality of life and social adaptation is precisely the severity of avoidant behavior in various social situations.

Summing up the analysis of different models of the relationship between shyness and social phobia, we can state that the data obtained (with a few exceptions) generally support the continuum model, but the fact that one third in the group with a high level of shyness does not experience social fears requires further interpretation and does not fit well into this model. Apparently, introverts who do not experience fear in social situations, but tend to avoid them, can fall into the group of shy people. This suggests that the concept of shyness is broader and more heterogeneous than the concept of social phobia. In the future, it would be possible to focus on factors that do not allow the development of

This suggests that the concept of shyness is broader and more heterogeneous than the concept of social phobia. In the future, it would be possible to focus on factors that do not allow the development of

social phobia with a high level of shyness. It can be assumed that one of the most important protective factors is the rejection of avoidance as a way of coping with social anxiety. When developing diagnostic tools, it is important to consider both the behavioral and emotional aspects of social anxiety.

While studies generally support the continuum model, there are also facts that contradict it. This applies, first of all, to studies devoted to the study of the fear of public speaking, which is traditionally referred to as a non-generalized type of social phobia. Back at 19[11], the following groups are distinguished in the category of social phobia: 1) generalized subtype - anxiety is evident in all social situations;

2) non-generalized subtype - the individual experiences anxiety in social situations, but there is at least one area in which he does not experience clinically significant anxiety; 3) limited subtype - anxiety is obvious only in limited social situations (for example, fear of speaking, writing, eating in the presence of other people). Such a division is in conflict with the continuum model, as it implies the presence of qualitative differences between subgroups. For this purpose, factor and cluster analysis of data is carried out. In favor of the model of R.G.Heimberg et al. say studies that used behavioral tasks (public speaking) and found that subjects with fear of public speaking (limited subtype, according to R.G. Heimberg) showed higher levels of anticipatory anxiety and more heartbeats than the group with generalized social phobia [11]. Thus, it can be noted that the question of the relationship between the concepts of shyness and social phobia is still far from being finally resolved.

Such a division is in conflict with the continuum model, as it implies the presence of qualitative differences between subgroups. For this purpose, factor and cluster analysis of data is carried out. In favor of the model of R.G.Heimberg et al. say studies that used behavioral tasks (public speaking) and found that subjects with fear of public speaking (limited subtype, according to R.G. Heimberg) showed higher levels of anticipatory anxiety and more heartbeats than the group with generalized social phobia [11]. Thus, it can be noted that the question of the relationship between the concepts of shyness and social phobia is still far from being finally resolved.

REFERENCES

1. Krasnov V.N. Anxiety disorders: their place in modern systematics and approaches to therapy // Social and Clinical Psychiatry. 2008. V. 18, No. 4. S. 33-38.

2. Sagalakova O.A. Social fears and social phobias: Textbook. Barnaul: Alt. un-ta, 2009. 102 p.

3. Yastrebov D.B. Social phobia and sensitive ideas of attitude (clinic and therapy): Abstract of the thesis. diss. ... cand. honey. Sciences. M., 2005.

diss. ... cand. honey. Sciences. M., 2005.

4. Beidel D.C., Turner S.M. Shy children, phobic adult: Nature and treatment of social phobia. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, 1998.324 p.

5. Buss A.H. Self-consciousness and social anxiety. San Francisco: Freeman, 1980.

6. Carducci B.J. Shyness: a bold new approach. NY: HarperCollins Publisher Inc., 1999.

7. Chavira D.A., Stein M.B., Malcarne V.L. Scrutinizing the relationship between shyness and social phobia // J. Anxiety Dis. 2002 Vol. 16. P. 585-598.

8. Cheek J.K. The revised Cheek and Buss Shyness Scale (RCBS). Unpublished, Wellesley College, Wellesley, MA, 1983.

9. Crozier R. Shyness as anxious self-preoccupation // Psychol. reports. 1979 Vol. 44. P. 959-962.

10. Godart N.T., Flament M.F., Lecrubier Y., Jeammet P. Anxiety disorder in anorexia nervosa. Comorbidity and chronology of appearance // Eur. Psychiatry. 2000 Vol. 15. P. 38-45.

11. Heimberg R. G., Holt C.S., Schneier F.R. et al. The issue of subtypes in the diagnosis of social phobia // J. Anxiety Dis. 1993 Vol. 7. P. 249-269.

G., Holt C.S., Schneier F.R. et al. The issue of subtypes in the diagnosis of social phobia // J. Anxiety Dis. 1993 Vol. 7. P. 249-269.

12. Heiser N.A., Turner S.M., Beidel D.C. Shyness: relationship to social phobia and other psychiatric disorders // Behav. Res. Therapy. 2003 Vol. 41. P. 209-221.

13. Heiser N.A., Turner S.M., Beidel D.C., Roberson-Nay R. Differentiating social phobia from shyness // J. Anxiety Dis. 2009 Vol. 23. P. 469-476.

14. Henderson L., Zimbardo P. Shyness. Encyclopedia of Mental Health. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1998.

15. Janet P. Les obsessions et la psychasthenie. Paris: Alcan, 1903. Vol. I. 782 p. Vol. II. 543 p.

16. Kessler R.C., McGonagle K.A., Zhao S. et al. Lifetime and 12-

month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States // Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1994 Vol. 51. P. 8-19.

17. Kessler R.C., Crum R.M., Warner L.A. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey // Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1997 Vol. 54. P. 313-321.

Gen. Psychiatry. 1997 Vol. 54. P. 313-321.

18.Laessle R.G., Wittchen H.U., Fitcher M.M., Pirke K.M. The significance of subgroups of bulimia and anorexia nervosa: life time frequency of psychiatric disorders // Int. J. Eating Dis. 1989 Vol. 8. P. 569-574.

19. Lecrubier Y., Weiller E. Comorbidities in social phobia // Int. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1997 Vol. 12. P. 17-21.

20. Liebowitz M.R., Gorman J.M., Fyer A.J., Klein D.F. Social phobia: Review of a neglected anxiety disorder // Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1985 Vol. 42. P. 729-736.

21.Lilenfeld L.R., Kaye W.H., Greeno C.G. et al. A controlled family study of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: psychiatric disorders in first-degree relatives and effects of proband comorbidity // Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1998 Vol. 55. P. 603-610.

22. Merikangas K.R., Angst J. Comorbidity and social phobia // Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. neurosci. 1995 Vol. 244. P. 297-303.

23. McNeil D.W. Terminology and evolution of constructs related to social phobia // From social anxiety to social phobia / S. G. Hofmann, P.M. DiBartolo (Eds.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, 2001, pp. 8-19.

G. Hofmann, P.M. DiBartolo (Eds.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon, 2001, pp. 8-19.

24. Pilkonis P.A., Zimbardo P.G. The personal and social dynamic of shyness // Emotions in personality and psychopathology / C.Izard (Ed.).

New York: Plenum Press, 1979. P. 133-160.

25. Rapee R.M. Overcoming shyness and social phobia: A step by step guide. Northvale, NJ: Jason Aronson, 1998.

26. Safren S.A., Heimberg R.G., Brown E.J., Holle C. Quality of life in social phobia // Depression and Anxiety. 1997 Vol. 4. P. 126-133.

27. Schneier F.R., Johnson J., Hornig C.D. et al. Social phobia: comorbidity and morbidity in an epidemiologic sample // Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 1992 Vol. 49. P. 282-288.

28. Turner S.M., Beidel D.C., Townsley R.M. Social phobia: Relationship to shyness // Behav. Res. Therapy. 1990 Vol. 28. P. 497-505.

29. Turner S.M., Beidel D.C., Borden J.W. et al. Social phobia: Axis 1 and Axis 2 correlates // J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1991 Vol. 100. P. 102-106.

P. 102-106.

30. Turner S.M., Beidel D.C., Townsley R.M. Social phobia: A comparison of specific and generalized subtypes and avoidant personality disorder // J. Abnorm. Psychol. 1992 Vol. 101. P. 326-331.

31. Van Amerigen M.V., Mancini C., Streiner D.L. Social disability in anxiety disorders // Neuropsychopharmacol. 1994 Vol. 10.615p.

32. Wunderlich U., Bronish T., Wittchen H.U. Comorbidity pattern in adolescents and young adults with suicide attempts // Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. neurosci. 1998 Vol. 248. P. 87-95.

33. Zimbardo P.G., Pilkonis P.A., Norwood R. Shackles of shyness // Psychology Today. 1975 Vol. 1, No. 6. P. 24-27.

34. Zimbardo P.G. Shyness: What is it and what to do about it. New York: Symphony Press, 1977.

SOCIAL ANXIETY: THE CONTENT OF THE CONCEPT AND MAIN DIRECTIONS

STUDIES. PART 1

IV Nikitina, AB Kholmogorova

The concepts of social anxiety, shyness and social phobia, different approaches to the relationship of these concepts are considered. The results of studies aimed at studying the relationship between shyness and social phobia are presented. The following models of social anxiety and social phobia are presented: interpersonal, cognitive, behavioral, model

The results of studies aimed at studying the relationship between shyness and social phobia are presented. The following models of social anxiety and social phobia are presented: interpersonal, cognitive, behavioral, model

self-presentation and an evolutionary approach to social anxiety. Prospects for further research are outlined.

Key words: social anxiety, shyness, social phobia, interpersonal aspects of social phobia, cognitive models of social phobia.

SOCIAL ANXIOUSNESS: CONTENT OF CONCEPT AND MAIN DIRECTIONS OF INVESTIGATION. PART 1

I. V. Nikitina, A. B. Kholmogorova

The authors consider the concepts of anxiousness, shyness and social phobia, and different approaches to interrelationships between these concepts. They review results of research concerning connections between shyness and social phobia. They describe the following models of social anxiousness and social phobia: interpersonal one, cognitive, behavioral,

self-presentation and evolution approach towards social anxiousness.