Concept of existentialism

What Is Existentialism? An Ethics Explainer By The Ethics Centre

If you’ve ever pondered the meaning of existence or questioned your purpose in life, you’ve partaken in existentialist philosophy.It would be hard to find someone who hasn’t asked themselves the big questions. What is the meaning of life? What is my purpose? Why do I exist? For thousands of years, these questions were happily answered by the belief your purpose in life was assigned prior to your creation. The existentialists, however, disagreed.

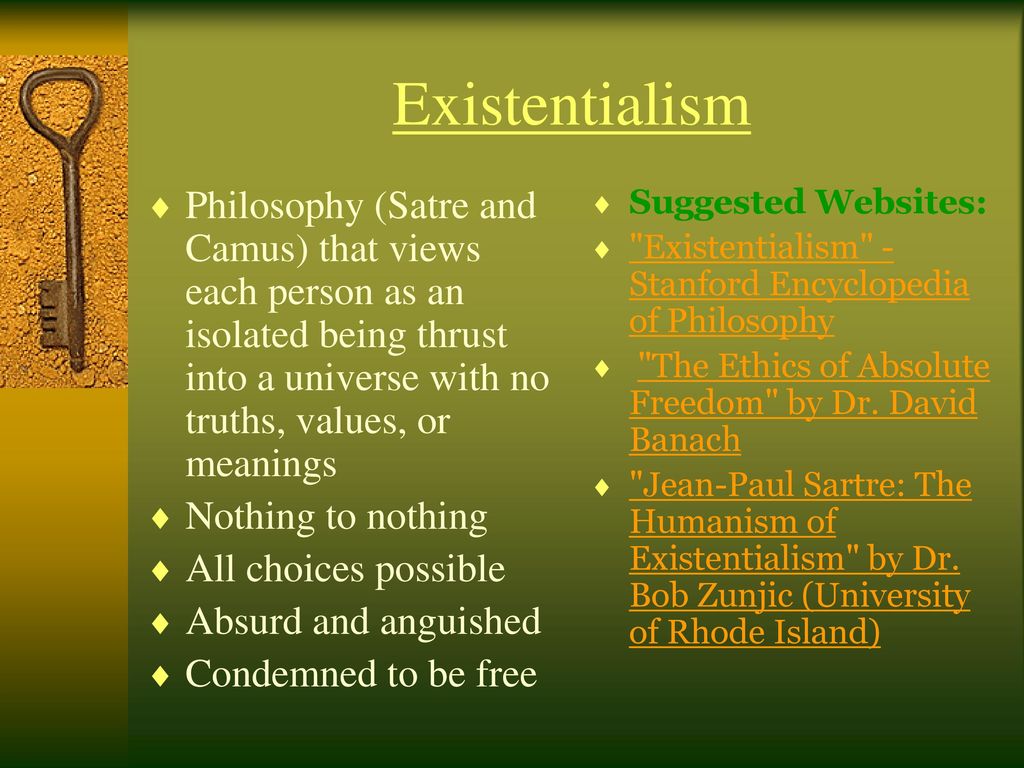

Existentialism is the philosophical belief we are each responsible for creating purpose or meaning in our own lives . Our individual purpose and meaning is not given to us by Gods, governments, teachers or other authorities.

In order to fully understand the thinking that underpins existentialism, we must first explore the idea it contradicts – essentialism.

Essentialism was founded by the Greek philosopher Aristotle who posited everything had an essence, including us. An essence is “a certain set of core properties that are necessary, or essential for a thing to be what it is”. A book’s essence, for example, is its pages. It could have pictures or words or be blank, be paperback or hardcover, tell a fictional story or provide factual information. Without pages though, it would cease to be a book. Aristotle claimed essence was created prior to existence. For people, this means we’re born with a predetermined purpose.

This idea seems to imply, whether you’re aware of it or not, that your purpose in life has been determined prior to your birth. And as you live your life, the decisions you make on a daily basis are contributing to your ultimate purpose, whatever that happens to be.

This was an immensely popular belief for thousands of years and gave considerable weight to religious thought that placed emphasis on an omnipotent God who created each being with a predetermined plan in mind.

If you agreed with this thinking, then you really didn’t have to challenge the meaning of life or search for your purpose. Your God already provided it for you.

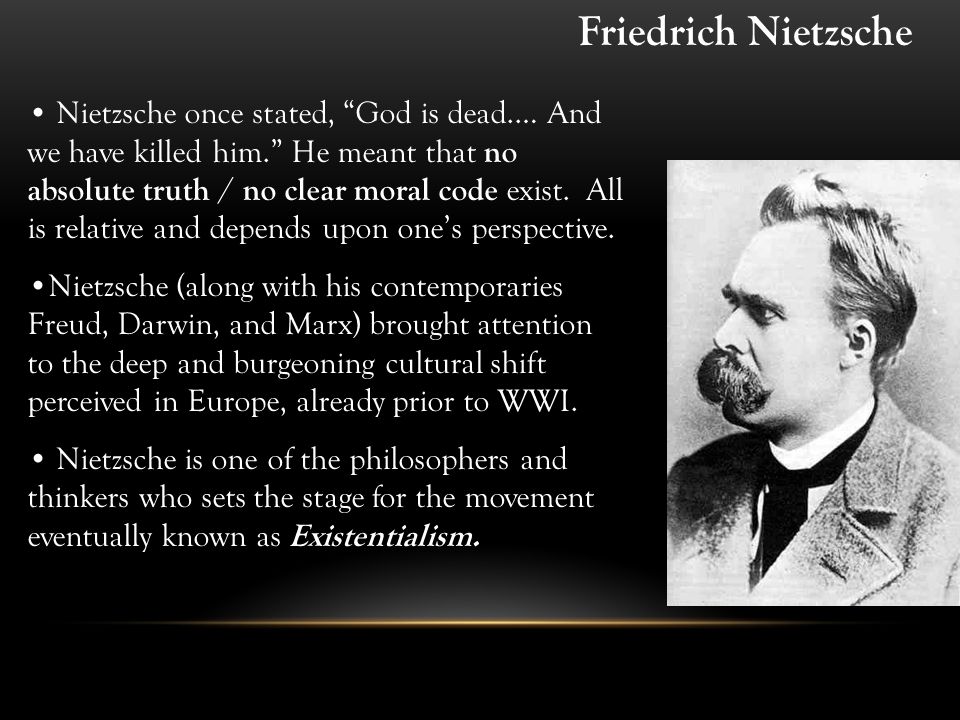

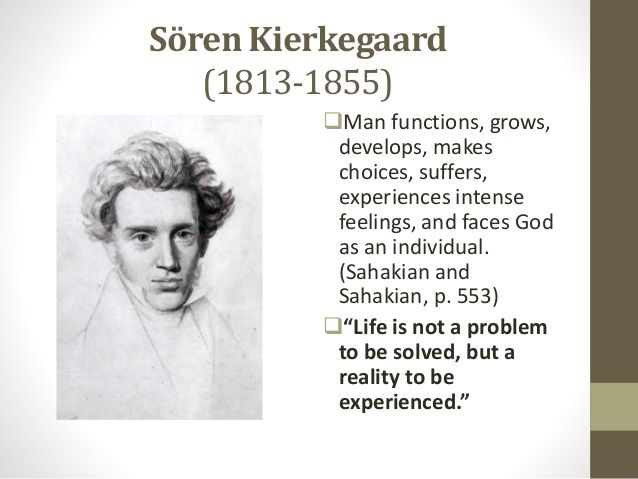

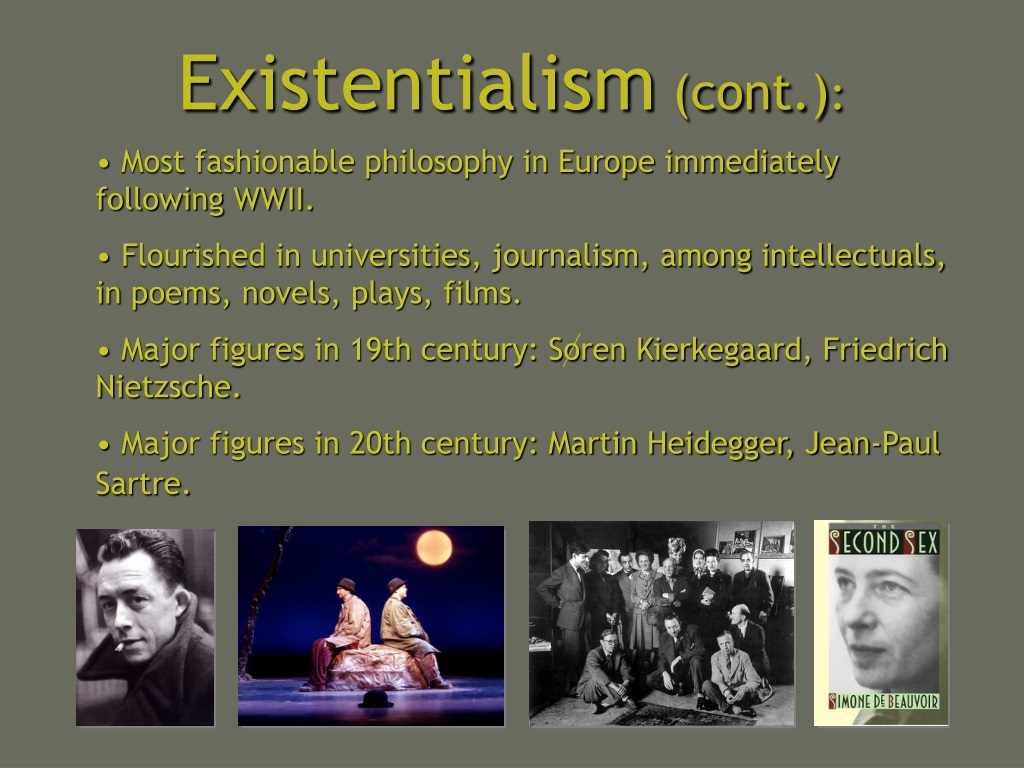

Existence precedes essenceWhile philosophers including Søren Kierkegaard, Fyodor Dostoyevsky and Friedrich Nietzsche questioned essentialism in the 19th century, existentialism was popularised by Jean-Paul Sartre in the mid-20th century following the horrific events of World War II.

As people questioned how something as catastrophically terrible as the Holocaust could have a predetermined purpose, existentialism provided a possible answer that perhaps it is the individual who determines their essence, not an omnipotent being.

The existentialist movement asked, “What if we exist first?”

At the time it was a revolutionary thought. You were created as a blank slate, tabula rasa, and it is up to you to discover your life’s purpose or meaning.

While not necessarily atheist, existentialists believe there is no divine intervention, fate or outside forces actively pushing you in particular directions. Every decision you make is yours. You create your own purpose through your actions.

The burden of too much freedomThis personal responsibility to shape your own life’s meaning carries significant anxiety-inducing weight. Many of us experience the so-called existential crisis where we find ourselves questioning our choices, career, relationships and the point of it all. We have so many options. How do we pick the right ones to create a meaningful and fulfilling life?

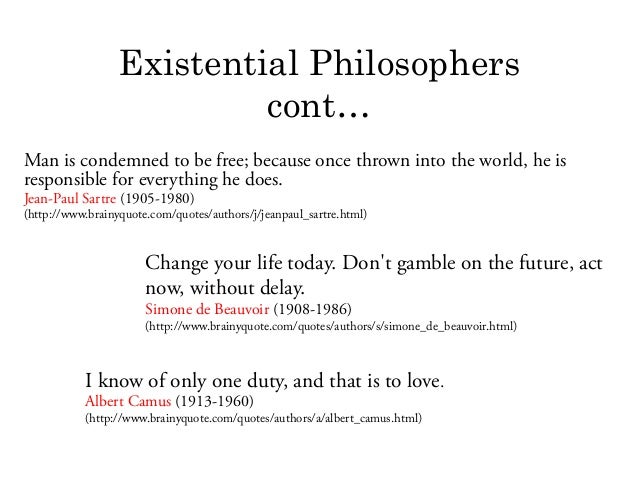

“Man is condemned to be free; because once thrown into the world, he is responsible for everything he does” – John-Paul Sartre

Freedom is usually presented positively but Sartre posed that your level of freedom is so great it’s “painful”. To fully comprehend your freedom, you have to accept that only you are responsible for creating or failing to create your personal purpose. Without rules or order to guide you, you have so much choice that freedom is overwhelming.

Without rules or order to guide you, you have so much choice that freedom is overwhelming.

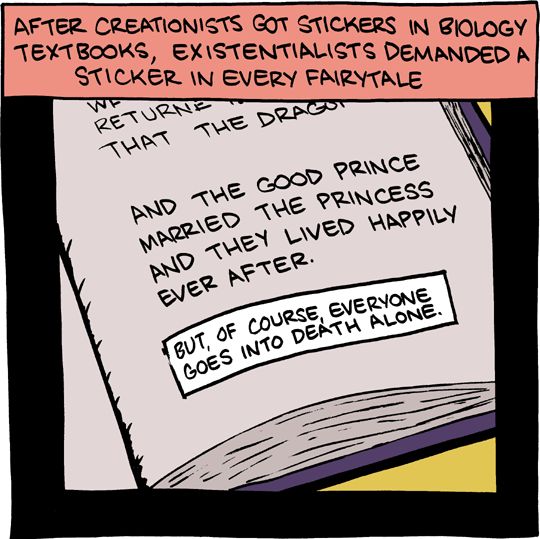

Life can be silly. But this isn’t quite what existentialists mean when they talk about the absurd. They define absurdity as the search for answers in an answerless world. It’s the idea of being born into a meaningless place that then requires you to make meaning.

The absurd posits there is no one truth, no inherent rules or guidelines. This means you have to develop your own moral code to live by. Sartre cautioned looking to authority for guidance and answers because no one has them and there is no one truth.

Living authentically and bad faithCoined by Sartre, the phrase “living authentically” means to live with the understanding of your responsibility to control your freedom despite the absurd. Any purpose or meaning in your life is created by you.

If you choose to live by someone else’s rules, be that anywhere between religion and the wishes of your parents, then you are refusing to accept the absurd. Sartre named this refusal “bad faith”, as you are choosing to live by someone else’s definition of meaning and purpose – not your own.

Sartre named this refusal “bad faith”, as you are choosing to live by someone else’s definition of meaning and purpose – not your own.

If you’re now thinking like an existentialist, then the answer to this question is both elementary and infinitely complex. You have the answer, you just have to own it.

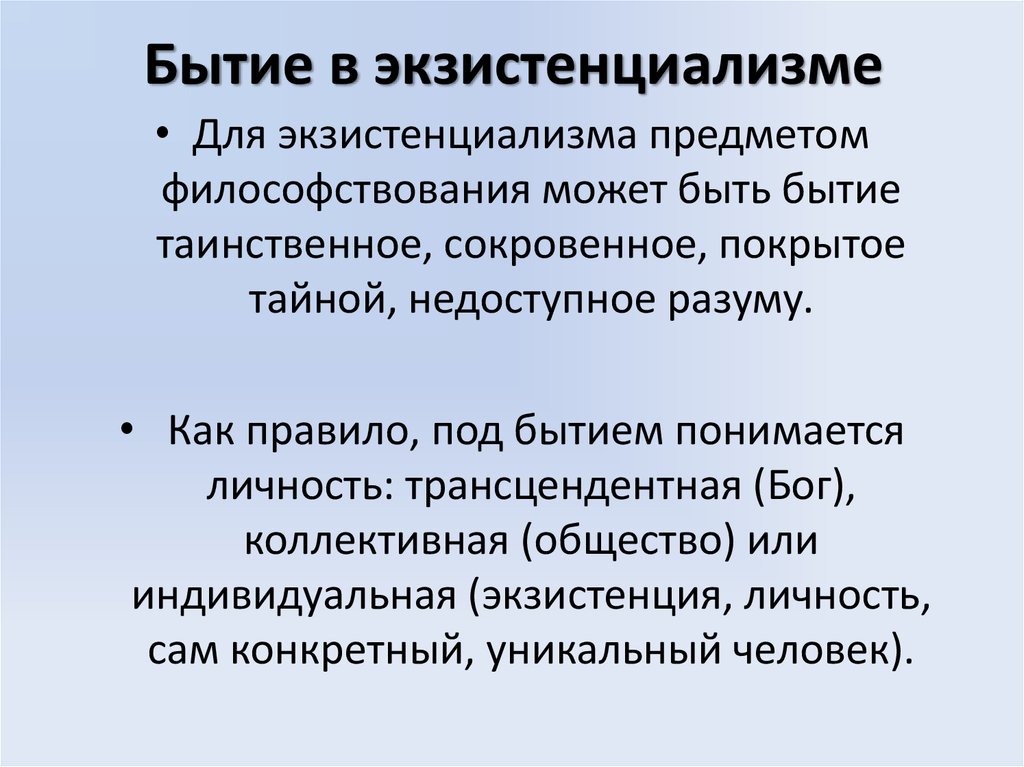

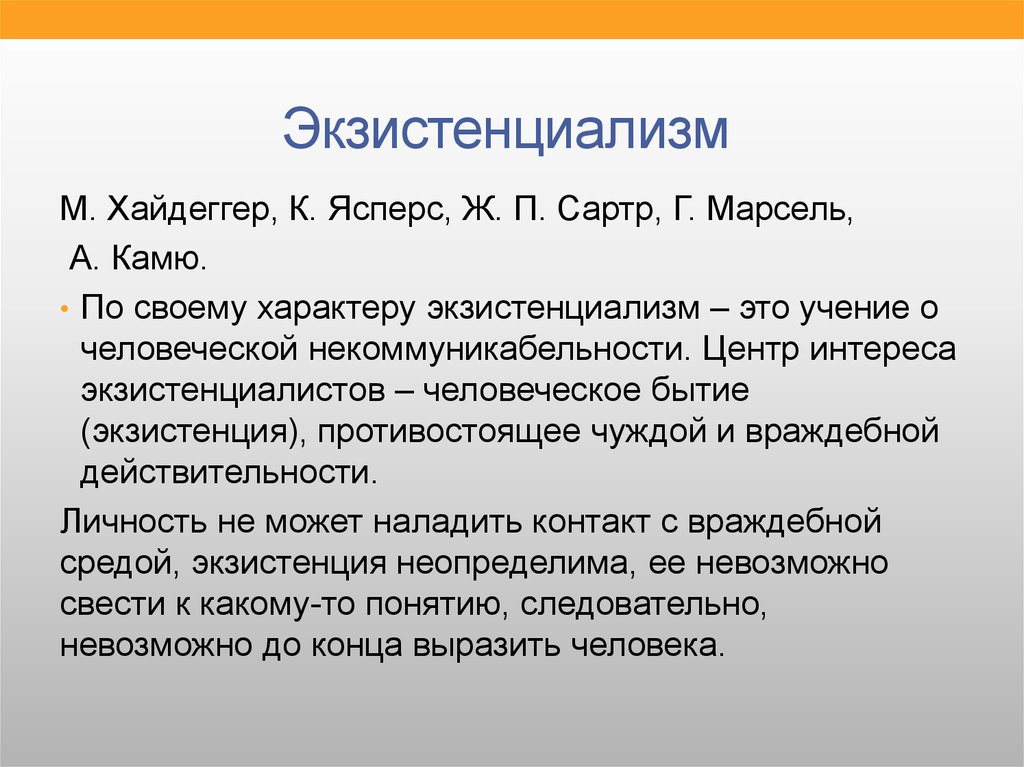

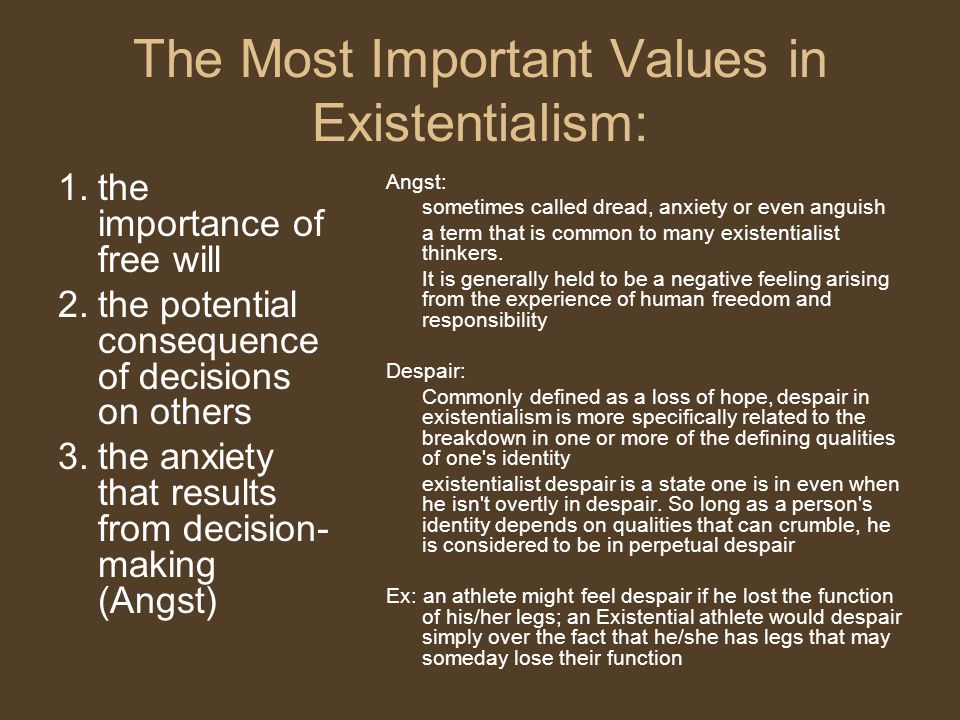

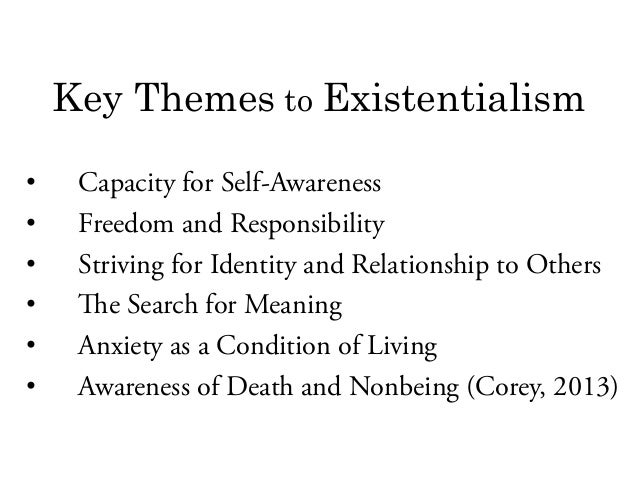

Existentialism is a philosophy that emphasizes individual existence, freedom and choice. It is the view that humans define their own meaning in life, and try to make rational decisions despite existing in an irrational universe. Thus, Existentialism believes that individuals are entirely free and must take personal responsibility for themselves (although with this responsibility comes angst, a profound anguish or dread). It therefore emphasizes action, freedom and decision as fundamental, and holds that the only way to rise above the essentially absurd condition of humanity (which is characterized by suffering and inevitable death) is by exercising our personal freedom and choice (a complete rejection of Determinism). Often, Existentialism as a movement is used to describe those who refuse to belong to any school of thought, repudiating of the adequacy of any body of beliefs or systems, claiming them to be superficial, academic and remote from life. Existentialism originated with the 19th Century philosophers Sren Kierkegaard and Friedrich Nietzsche, although neither used the term in their work. In the 1940s and 1950s, French existentialists such as Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus (1913 - 1960), and Simone de Beauvoir (1908 - 1986) wrote scholarly and fictional works that popularized existential themes, such as dread, boredom, alienation, the absurd, freedom, commitment and nothingness.

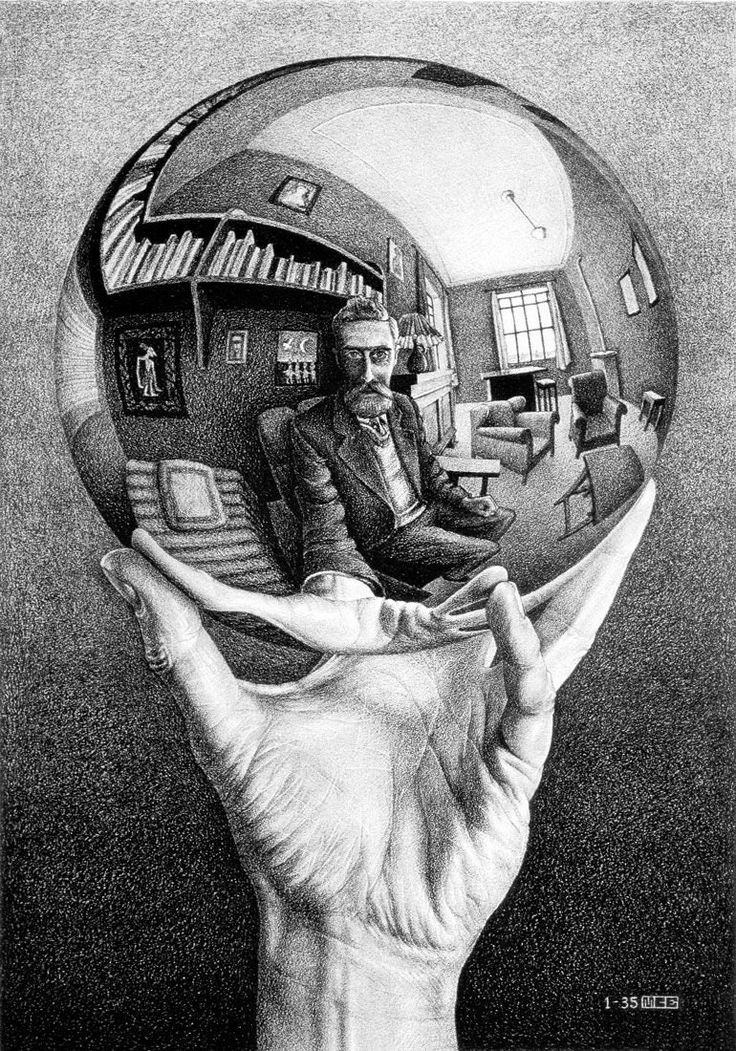

Unlike Ren Descartes, who believed in the primacy of consciousness, Existentialists assert that a human being is "thrown into" into a concrete, inveterate universe that cannot be "thought away", and therefore existence ("being in the world") precedes consciousness, and is the ultimate reality. Kierkegaard saw rationality as a mechanism humans use to counter their existential anxiety, their fear of being in the world. Sartre saw rationality as a form of "bad faith", an attempt by the self to impose structure on a fundamentally irrational and random world of phenomena ("the other"). This bad faith hinders us from finding meaning in freedom, and confines us within everyday experience. Kierkegaard also stressed that individuals must choose their own way without the aid of universal, objective standards. Friedrich Nietzsche further contended that the individual must decide which situations are to count as moral situations. According to Camus, when an individual's longing for order collides with the real world's lack of order, the result is absurdity. Human beings are therefore subjects in an indifferent, ambiguous and absurd universe, in which meaning is not provided by the natural order, but rather can be created (however provisionally and unstable) by human actions and interpretations. Existentialism can be atheistic, theological (or theistic) or agnostic. Some Existentialists, like Nietzsche, proclaimed that "God is dead" and that the concept of God is obsolete. Others, like Kierkegaard, were intensely religious, even if they did not feel able to justify it.

Existentialist-type themes appear in early Buddhist and Christian writings (including those of St. Augustine and St.Thomas Aquinas). In the 17th Century, Blaise Pascal suggested that, without a God, life would be meaningless, boring and miserable, much as later Existentialists believed, although, unlike them, Pascal saw this as a reason for the existence of a God. His near-contemporary, John Locke, advocated individual autonomy and self-determination, but in the positive pursuit of Liberalism and Individualism rather than in response to an Existentialist experience. Existentialism in its currently recognizable form was inspired by the 19th Century Danish philosopher Sren Kierkegaard, the German philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche, Martin Heidegger, Karl Jaspers (1883 - 1969) and Edmund Husserl, and writers like the Russian Fyodor Dostoevsky (1821 - 1881) and the Czech Franz Kafka (1883 - 1924). Kierkegaard and Nietzsche, like Pascal before them, were interested in people's concealment of the meaninglessness of life and their use of diversion to escape from boredom. However, unlike Pascal, they considered the role of making free choices on fundamental values and beliefs to be essential in the attempt to change the nature and identity of the chooser. In Kierkegaard's case, this results in the "knight of faith", who puts complete faith in himself and in God, as described in his 1843 work "Fear and Trembling". In Nietzsche's case, the much-maligned "bermensch" (or "Superman") attains superiority and transcendence without resorting to the "other-worldliness" of Christianity, in his books "Thus Spake Zarathustra" (1885) and "Beyond Good and Evil" (1887). Martin Heidegger was an important early philosopher in the movement, particularly his influential 1927 work "Being and Time", although he himself vehemently denied being an existentialist in the Sartrean sense. His discussion of ontology is rooted in an analysis of the mode of existence of individual human beings, and his analysis of authenticity and anxiety in modern culture make him very much an Existentialist in the usual modern usage. Existentialism came of age in the mid-20th Century, largely through the scholarly and fictional works of the French existentialists, Jean-Paul Sartre, Albert Camus (1913 - 1960) and Simone de Beauvoir (1908 - 1986). Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908 - 1961) is another influential and often overlooked French Existentialist of the period. Sartre is perhaps the most well-known, as well as one of the few to have actually accepted being called an "existentialist". In "The Myth of Sisyphus" (1942), Albert Camus uses the analogy of the Greek myth of Sisyphus (who is condemned for eternity to roll a rock up a hill, only to have it roll to the bottom again each time) to exemplify the pointlessness of existence, but shows that Sisyphus ultimately finds meaning and purpose in his task, simply by continually applying himself to it. Simone de Beauvoir, an important existentialist who spent much of her life alongside Sartre, wrote about feminist and existential ethics in her works, including "The Second Sex" (1949) and "The Ethics of Ambiguity" (1947). Although Sartre is considered by most to be the pre-eminent Existentialist, and by many to be an important and innovative philosopher in his own right, others are much less impressed by his contributions.

Herbert Marcuse (1898 - 1979) has criticized Existentialism, especially Sartre's "Being and Nothingness", for projecting some features of living in a modern oppressive society (features such as anxiety and meaninglessness) onto the nature of existence itself. Roger Scruton (1944 - ) has claimed that both Heidegger's concept of inauthenticity and Sartre's concept of bad faith are both self-inconsistent, in that they deny any universal moral creed, yet speak of these concepts as if everyone is bound to abide by them. Logical Positivists, such as A. J. Ayer and Rudolf Carnap (1891 - 1970), claim that existentialists frequently become confused over the verb "to be" (which is meaningless if used without a predicate) and by the word "nothing" (which is the negation of existence and therefore cannot be assumed to refer to something). Marxists, especially in post-War France, found Existentialism to run counter to their emphasis on the solidarity of human beings and their theory of economic determinism. They further argued that Existentialism's emphasis on individual choice leads to contemplation rather than to action, and that only the bourgeoisie has the luxury to make themselves what they are through their choices, so they considered Existentialism to be a bourgeois philosophy. Christian critics complain that Existentialism portrays humanity in the worst possible light, overlooking the dignity and grace that comes from being made in the image of God. Also, according to Christian critics, Existentialists are unable to account for the moral dimension of human life, and have no basis for an ethical theory if they deny that humans are bound by the commands of God. On the other hand, some commentators have objected to Kierkegaard's continued espousal of Christianity, despite his inability to effectively justify it. In more general terms, the common use of pseudonymous characters in existentialist writing can make it seem like the authors are unwilling to own their insights, and are confusing philosophy with literature. |

What is existentialism and how it can help you

March 10 Likbez A life

Philosophers will explain how to accept yourself and not only.

You can listen to the short version of the article. If it's more convenient for you, turn on the podcast. What is existentialism? And they do not know what is right and what is not. nine0003 One of the first existentialists was the Danish philosopher Søren Kierkegaard back in the 19th century. However, the direction was truly formed in the first half of the 20th century. Two world wars, the crisis of traditions, the inability of existing theories to explain what is happening and the loss of faith in progress made the critical ideas of Nikolai Berdyaev, Karl Jaspers, Simone de Beauvoir, Albert Camus and Jean-Paul Sartre popular. The last two existentialists even won the Nobel Prize in Literature. Both received recognition for their artistic works, which were inextricably linked to the philosophy of existentialism. nine0003 Existentialism has become a significant phenomenon in Western culture. This philosophy strongly influenced the work of artists Alberto Giacometti and Jackson Pollock, as well as filmmakers Jean-Luc Godard and Ingmar Bergman. Although the direction has existed for many years, some ideas are still relevant today. Existentialists came to the conclusion that the vast Universe has no purpose, logic or meaning. A person has to independently create himself in a world indifferent to him, where no one owes anything to anyone. Therefore, people are lonely, and even communication cannot get rid of this feeling. For existentialists, existence has become an absurdity. Thus, Albert Camus compared existence with the work of the mythical king Sisyphus. The gods punished the ruler and doomed him to forever drag a huge stone up the mountain, from which he falls all the time, almost reaching the top. nine0003 Sisyphus, painting by Titian, 1548-1549. Image: Museo Nacional del Prado / Wikimedia Commons People, like Sisyphus, are doomed to seek the meaning of life and not find it. However, the absurdity of the world does not mean that we should stop looking for the meaning of life. Because without this search, according to existentialists, it is impossible to fully live. If a person stops asking himself why he exists, existence will begin to burden him more and more, and he himself will plunge into an existential crisis. nine0003 Existentialists assume that existence is not predetermined in any way, and there is no universal way. Each individual chooses his own path, creates or invents himself every day. In this sense, we are unique and do not resemble either animals or inanimate objects. But freedom in existentialism is not a gift, but a heavy burden. She constantly demands to make a choice. According to Sartre, a person is “doomed to freedom”, since he must either be himself or constantly adapt to his environment. And one must bear responsibility for any choice. Sartre argued that only "one who makes values exist so that they determine his actions" can be considered a person. Therefore, for existentialists, following duty and acting according to their real ideas and ideals are not the same thing. For example, a truly free person will get up at the alarm clock not because of work, but because he himself decided to wake up at six in the morning, be responsible and go to the office every day. nine0003 Existentialists consider moral norms to be artificial, conditional, and sometimes completely false. Of course, this does not mean that you can do whatever you want, such as stealing or killing. The main thing is to soberly evaluate your own ideals and the rules imposed by society and the world. So you can understand what you are really striving for and what is really important to you. This will help you stop worrying and get rid of the missed profit syndrome. According to existentialists, we can and should pay more attention to the spiritual than to the material. After all, nationality, gender, skin color and class do not define a person. This is just an interpretation of his image. Therefore, existentialists recommend abstracting from one's "I" and from the surrounding world in order to look at oneself and others through the eyes of an impartial observer. This is the only way to see the real people. Existentialists doubted almost everything: morality, the cognizability of the world and man, the existence of higher powers. Of course, it is not necessary to repeat after philosophers, but the ability to think critically in an era when it is very difficult to distinguish truth from lies is extremely valuable. nine0003 Read also 🤔💡📚 Headings : Latest articles, Philosophy Did you find something useful here? Help us stay free, independent, and free by making any donation or purchasing some of our literary merchandise. Existentialism is one of the brightest trends in philosophy of the 20th century. The focus of attention of this philosophical trend is the questions of existence (Latin existentia), the existence of a person. Being is interpreted as a directly given experience by a specific subject of its own existence, which gives the right to consider the philosophical approach of the existentialists as irrational. Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) is one of the few existentialists who can be unequivocally attributed to representatives of this philosophical trend, as the philosopher himself manifested in his lecture “Existentialism is humanism” (1946). According to Sartre, being is threefold. It embodies itself in three interrelated forms: "being-in-itself", "being-for-itself" and "being-for-other". These are three sides of a single human reality, shared only in abstraction. Its first form is “being-in-itself”. Sartre reveals this form through three laconic givens: “Being is. Being is in itself. Being is what it is”[1]. “Being-for-itself” is the immediate life of self-consciousness, the experience of one's own individual consciousness, pure “nothing” in comparison with the world. It can only exist as a repulsion, a negation, a "hole" in being as such. nine0003 The last, third form of the existence of consciousness is “being-for-other”. It is this incarnation of which is of particular interest to us. The appearance of the Other disturbs the habitual environment of the subject, “bursts into his universe”, brings with it something new, unknown. After the reaction of rejection comes a period of struggle. First of all - the struggle of views. Sartre's "look" has a special meaning in interaction with the Other. It is the glance that is the very unique instrument through which the Other informs the consciousness that it has been known by this Other as an object. The doctor laughs, he gives me the inviting look of an accomplice (…). I do not laugh and do not respond to his advances - then, without ceasing to laugh, he tests on me the frightening fire of his eyes. We stare at each other for a few seconds (...). And yet, he is the first to avert his eyes - just think, he gave in to some loner, who has no social significance, is it worth worrying about it, it will be immediately forgotten [2]. The fight is over. The loser could not keep the Other as an object, but he himself became one and is now forced to seek excuses for himself and restore the harmony of his inner world. nine0003 "The presence of the Other for me and me for the Other is objectivity. This manifestation of the Other is connected with the threat of freedom for the "I" that arose with its appearance. The category of freedom is one of the fundamental ones for existentialism. Being-for-itself, which thought itself independently, having unlimited freedom of choice in positioning itself in the surrounding world and space, with the advent of the Other, is forced to realize the limitations of its own desires and the freedom to manifest itself outside. Having been "objectified" under the gaze of the Other in a concrete form, the Self no longer has the exclusive privilege of manifesting and imagining itself in any conceivable and desirable way. The other “fixed” me, determined my place in space, marking the boundaries of my physical presence, and “evaluating” in some (incomprehensible, only known way) my meaningful characteristics and “what I am”. Under such circumstances of interaction with Others, the moment of loss of freedom is dramatic and extremely stressful for consciousness. The presence of the Other is associated with unbearable experiences and extremely unpleasant sensations. For the hero of Sartre's novel of the same name, Nausea was such an irresistible sensation. Feelings caused by the look of another - shame, embarrassment, etc., are actually designed to make a person feel his existence. “To comprehend oneself as being considered means to comprehend oneself as spatial and realizing space,” to feel one’s own objectivity. At this moment, a certain relationship arises between the Self and the Other. The whole essence of human reality is revealed - at the same time "to be for oneself" and "to be for another". Understanding this contributes to the definition of one's own self, the ability to distinguish oneself from the Other, since "there is a border between two consciousnesses. Simplistically, Sartre formulates the concept of interaction with the Other through corporeality as follows: I exist with my body - this is his first dimension of being. My body is used and cognized by the Other — this is its second dimension. But since I am for the other, he reveals himself in me as a subject for which I am an object. What is at stake here, as we have seen, is my fundamental relationship with the other. Consequently, I exist for myself as known to others, in particular, in my very facticity. I exist for myself as known by the Other as a body. This is the third ontological dimension of my body [3]. nine0003 The unwillingness to be just an object, a thing for the Other, however, is not a reason for refusing to interact with the Other. On the contrary, only in communication, in interaction, being can "distract" from its own insignificance "for-itself" and determine itself and its place in the world. It would be appropriate to quote here in which Sartre exhaustively explains the necessity of the existence of the Other: In contrast to the philosophy of Descartes, in contrast to the philosophy of Kant, through "I think" we comprehend ourselves in the face of another, and the other is just as certain for us as we are ourselves. Thus, a person who comprehends himself through the cogito immediately discovers all others at the same time, and, moreover, as a condition of his own existence. He is aware of the fact that he cannot be anything (in the sense in which a person is said to be witty, angry or jealous), unless others recognize him as such. Thus, the Other determines the existence of the third, final category – “being-for-other”. The unity of all three categories constitute Sartre's theory of being. The presence of the Other reveals itself and becomes necessary for human existence. A negative reaction to the appearance of the Other is only a necessary reaction before the discovery of one's own being. No matter how unbearable the presence of the Other may be, it alone fills the existence of man with meaning. In the absence of the Other, a person is “nothing” and his being, through recognition, depends entirely and completely on the Other. In addition to Sartre's philosophy, the concept of the Other as a necessary element of existence was developed in the works of Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995). The figure of the Other is the protagonist of a whole galaxy of his philosophical works: "Time and the Other" (1948), "Totality and the Infinite" (1961), "The Humanism of the Other Man" (1973). For Levinas, the Other is a key element of being, but at the same time, unlike Sartre, it is not perceived as something hostile. In the introduction to the book "Totality and the Infinite" we immediately find the following reservation: "subjectivity in this book will appear as accepting the Other, as hospitality"[5]. As a contrast to the picture of the war, in the scenery of which the specified work of Levinas was written, the Other and his kind and merciful acceptance are the main characters in the philosophical plot of "Totality and the Infinite". The aspiration of the individual to the surrounding world is the basis for metaphysics, which “emerges as a movement seeking from the world familiar to us” to the “alien to us” not-self to “there”[6]. The search for something different and absolutely different is the primary desire of the individual. The most radical "other" for him is the Other. The Other, inasmuch as he is different, is not simply “alterego”, he is what I am not [7] ( and in this the understanding of the Other by Sartre and Levinas coincides. — OK ). Relationships with the Other problematize me, withdraw me and continue to change me myself, revealing new talents in me. I did not know that I was so rich, although I have no right now to keep something for myself [8]. Desire to communicate - the desire to express kindness and empathy to the Other. You can show your face by starting to communicate with an outsider through the language, that is, to speak, which means “to get out of your appearance, your appearance”[9]. The other person stirs up an ethical movement in the mind, and henceforth to be I means the impossibility of stepping aside from responsibility. The uniqueness of the Self lies in the fact that no one can answer for me. To reveal such an orientation in the Self means to identify the Self and morality. In the face of the Other I am infinitely responsible. nine0003 In Levinas, the emergence of the Other, just as in Sartre, threatens freedom: “to accept the Other means to question my freedom”[10]. The experience of communication with the Other, according to Levinas, arises not from the desire for knowledge or possession, but from a special state of closeness of one subjectivity to another. This experience arose before the subject-object relationship, when, in the natural breath of one person, another person for the first time and with surprise heard the call to listen to him, to understand and jointly protect being. Responsibility for the Other in Levinas, - This is a stricter name for what is usually called love for one's neighbor, mercy... I am responsible for the Other even when he commits a crime. This is the essence of human consciousness: all people are responsible one for the other, and I am more than all others. Man's consciousness does not lie at all in his possibilities, but in his responsibility, in a compassionate attitude towards the Other, in agreement with him, in obligation to him. Whether I like it or not, I care about the Other. Responsibility for the Other is the vocation of man in being; becoming responsible, I acquire the highest reality [12]. nine0003 Here appears justice, which “is born in a collision with the face of the Other, from a sense of responsibility for the Other. Justice is impartiality. Justice is born out of love.”[13] Thus, the phenomenon of the Other is an integral element of the existence of the individual. To summarize. First of all, it should be noted that in the works of both philosophers the phenomenon of the Other plays a key role. Only the presence of the Other is the final element for the formation of the real consciousness of the subject. The Self is incomplete until the Other appears. Only together with the Other is the existence of the Self justified, and the future has meaning. Communication and interaction between the Self and the Other is the most important condition for completing the integrity of being. Sartre uses the gaze as a means of communication, Levinas prefers verbal language. nine0003 The main subject of study of existentialism is existence. Interaction with the Other not only conditions its acceptance by one's own Self, but also imposes on the Self a certain responsibility for the Other. Levinas directly speaks of responsibility for the Other as a manifestation of mercy and compassion. Sartre expands on the topic of responsibility in his article "Existentialism is a humanism", responding to criticism of the egocentrism of this philosophical trend. Indeed, the topic of the lecture given by Sartre in Paris in October 1945 corresponded perfectly to the realities of the surrounding world and highlighted this topical for its time and capacious essence of existentialism. It was humanism that could become an alternative to the monstrous war that shook the world and turned the consciousness of all mankind and every single individual. The Second World War, which claimed millions of lives and revealed to the planet the face of fascism, monstrous in its cruelty, demanded new philosophical views from society. Philosophers of existentialism come out in defense of humanism, in defense of each individual person, and most importantly, the world as the only possible and justified form of human existence. [1] Sartre J. This concept plays a significant role in the intellectual world even today.

This concept plays a significant role in the intellectual world even today. What existentialism can teach modern man

1. Continue to search for the meaning of life, even though the world is absurd

Therefore, they may feel a sense of anxiety, abandonment and aimlessness of their stay - experiencing the so-called existential crisis.

2. Be responsible for your choice

nine0003

3. To be oneself

4. Remember that not only gender and appearance characterize a person

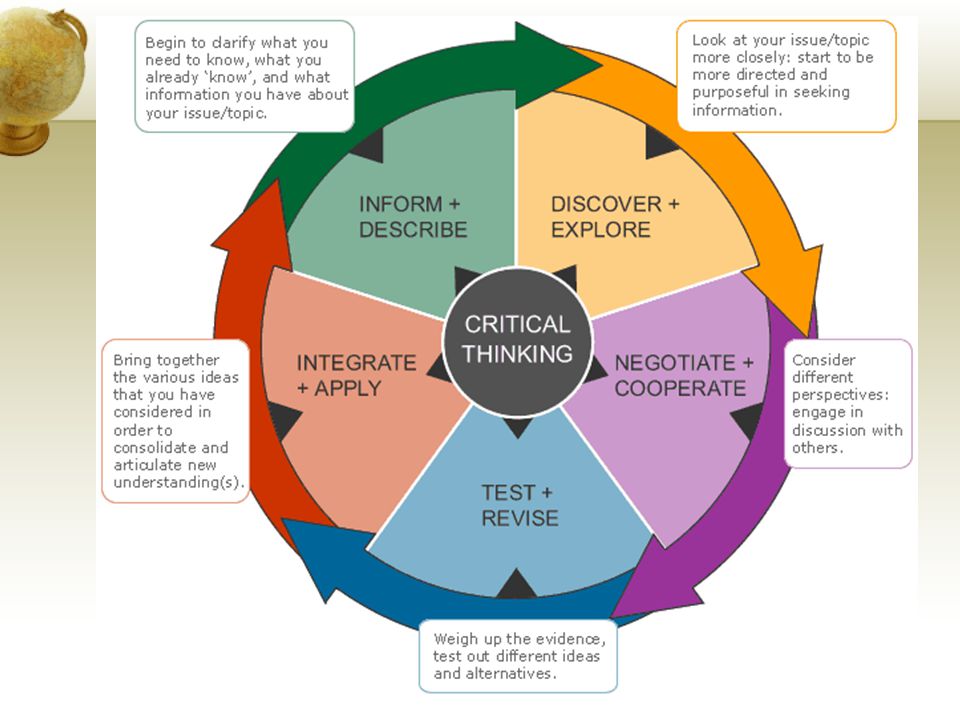

5. Think critically

" Can determinism make life easier

" Can determinism make life easier Sartre and Levinas - Monoclair

Who is the Other? To what extent does it restrict our freedom? And what threatens us with a collision with the Other? Once again, we understand these issues together with the existentialist philosophers Jean-Paul Sartre and Emmanuel Levinas. nine0012

In contrast to the classical ontological approach with mediated perception of objects, in existentialism both the object and the subject of cognition is a specific, separately taken individual who understands, realizes and lives his own existence. However, despite the increased attention of existentialism to the existence of a particular individual, a kind of individualism and "egocentricity" of this philosophical direction, one of the main places (and in some cases - central) in it is occupied by the figure of the Other. In order to understand this apparent contradiction, we decided to consider the phenomenon of the Other among existentialist philosophers using the philosophical views of Jean-Paul Sartre and Emmanuel Levinas as an example. Let's start with the first one. nine0003

In contrast to the classical ontological approach with mediated perception of objects, in existentialism both the object and the subject of cognition is a specific, separately taken individual who understands, realizes and lives his own existence. However, despite the increased attention of existentialism to the existence of a particular individual, a kind of individualism and "egocentricity" of this philosophical direction, one of the main places (and in some cases - central) in it is occupied by the figure of the Other. In order to understand this apparent contradiction, we decided to consider the phenomenon of the Other among existentialist philosophers using the philosophical views of Jean-Paul Sartre and Emmanuel Levinas as an example. Let's start with the first one. nine0003

Sartre's Problem of the Other: The Other as a Necessary Condition of Being  The main concepts of the philosophy of existentialism are popularized in his literary works, and substantiated in more detail in philosophical works. "Being and Nothing" (1943) is the main one. It is on this work of Sartre that we will rely in the future.

The main concepts of the philosophy of existentialism are popularized in his literary works, and substantiated in more detail in philosophical works. "Being and Nothing" (1943) is the main one. It is on this work of Sartre that we will rely in the future.  This form arises only with the emergence of the phenomenon of the "Other" and undergoes significant changes with the evolution of the relationship between the Self and the Other. The first human reaction to the appearance of the Other is denial, rejection. Sartre's concept of the Other is "not being me." Initially, the Other can be perceived by consciousness as an object, but it soon becomes clear that the Other is not just an object, a non-subject of the surrounding world, but something completely different. nine0003

This form arises only with the emergence of the phenomenon of the "Other" and undergoes significant changes with the evolution of the relationship between the Self and the Other. The first human reaction to the appearance of the Other is denial, rejection. Sartre's concept of the Other is "not being me." Initially, the Other can be perceived by consciousness as an object, but it soon becomes clear that the Other is not just an object, a non-subject of the surrounding world, but something completely different. nine0003  The struggle of views has a certain outcome - the loser will become an object and submit to the Other, the winner will retain his inner world, the universe. A colorful example of such a battle can be found on the pages of Sartre's works of art, for example:

The struggle of views has a certain outcome - the loser will become an object and submit to the Other, the winner will retain his inner world, the universe. A colorful example of such a battle can be found on the pages of Sartre's works of art, for example:

" Having turned the Self into an object, the Other finally kills “all possibilities” of consciousness for independent existence.

" Having turned the Self into an object, the Other finally kills “all possibilities” of consciousness for independent existence.  Thus, the Other deprived me of a part of my freedom. nine0003

Thus, the Other deprived me of a part of my freedom. nine0003  " nine0003

" nine0003

Read also Descartes was wrong: a person is aware of himself through the Other

Like the hero of the novel "Nausea" by Antoine Roquentin, one can suffer from bouts of nausea, each time leaving the boundaries of the usual freedom of being in one's own thoughts and loneliness, but clearly understand that only being with "nauseous" others will allow one to maintain a sense of reality and, ultimately, oneself. yourself as a complete person. Loneliness is destructive, meaningless and boring, it kills the very nature of man. nine0003

Like the hero of the novel "Nausea" by Antoine Roquentin, one can suffer from bouts of nausea, each time leaving the boundaries of the usual freedom of being in one's own thoughts and loneliness, but clearly understand that only being with "nauseous" others will allow one to maintain a sense of reality and, ultimately, oneself. yourself as a complete person. Loneliness is destructive, meaningless and boring, it kills the very nature of man. nine0003

To get any truth about myself, I have to go through another. The other is necessary for my existence - just as, however, as for my self-knowledge. Under these conditions, the discovery of my inner world reveals to me at the same time the other, as the freedom standing before me, which thinks and wishes “for” or “against” me. Thus, a whole world opens up, which we call intersubjectivity. In this world, a person decides what he is and what others are [4]. nine0003

To get any truth about myself, I have to go through another. The other is necessary for my existence - just as, however, as for my self-knowledge. Under these conditions, the discovery of my inner world reveals to me at the same time the other, as the freedom standing before me, which thinks and wishes “for” or “against” me. Thus, a whole world opens up, which we call intersubjectivity. In this world, a person decides what he is and what others are [4]. nine0003  nine0003

nine0003

The problem of the Other in Levinas: responsibility and mercy towards the Other as an essential attribute of existence  nine0003

nine0003

nine0002 Nothing connects me with another, I have no power over him. Interaction with the Other is a relationship that can take shape in the "general conditions of the economy of being, only if it is directed from the Self to the Other." If Sartre communicates through a glance, then Levinas's I and the Other appear before each other "face to face", and language is the instrument of their interaction. The desire for the Other, for communion with him, is a natural human desire. The desire of the Other being (that is, sociability) is born in a being who has everything in abundance. nine0003

The desire of the Other being (that is, sociability) is born in a being who has everything in abundance. nine0003

However, in the conclusion of his work "Totality and the Infinite", Levinas considers this issue in a different way, shifting the emphasis from the actual restriction to the necessity of such. How bad is restriction of freedom? After all, the irrational freedom of the subject is not limited, has no limits, and therefore is an endless arbitrariness. In this sense, the appearance of the Other legitimizes the freedom of the individual, not so much limiting it, but justifying its necessary limits, allowing it not to leave the boundaries of justice and “saving” it from dangerous arbitrariness. In this sense, the restriction of freedom to Others serves the cause of truth, which means that it cannot be a threat, but only a blessing [11]. nine0003

However, in the conclusion of his work "Totality and the Infinite", Levinas considers this issue in a different way, shifting the emphasis from the actual restriction to the necessity of such. How bad is restriction of freedom? After all, the irrational freedom of the subject is not limited, has no limits, and therefore is an endless arbitrariness. In this sense, the appearance of the Other legitimizes the freedom of the individual, not so much limiting it, but justifying its necessary limits, allowing it not to leave the boundaries of justice and “saving” it from dangerous arbitrariness. In this sense, the restriction of freedom to Others serves the cause of truth, which means that it cannot be a threat, but only a blessing [11]. nine0003  This surprise was the exit "beyond-themselves."

This surprise was the exit "beyond-themselves."

The appearance of the Other marks the boundaries of one's own Self, contributes to the establishment of the boundaries of freedom, the formation of the principles of justice and responsibility. The other is an integral part of myself, the Society as a whole is a brotherhood, each member of which is kind, merciful and responsible for the other. nine0003

The appearance of the Other marks the boundaries of one's own Self, contributes to the establishment of the boundaries of freedom, the formation of the principles of justice and responsibility. The other is an integral part of myself, the Society as a whole is a brotherhood, each member of which is kind, merciful and responsible for the other. nine0003  But invariably - coexistence with the Other. Once again confirming the judgment of Aristotle, Sartre and Levinas prove that "man is a social animal." The non-autonomous existence of the individual and his inner experiences are the main focus of existentialism. It is the phenomenon of interaction, coexistence, community, and in general - society - that is the main subject of study of the philosophical direction under consideration. Even at the beginning of his work “Being and Nothingness”, Sartre sets the framework for his research and emphasizes that the study of the diversity of the individual’s action serves the sole purpose of “penetrating into the deep meaning of the relationship“ man-world ”[14]. nine0003

But invariably - coexistence with the Other. Once again confirming the judgment of Aristotle, Sartre and Levinas prove that "man is a social animal." The non-autonomous existence of the individual and his inner experiences are the main focus of existentialism. It is the phenomenon of interaction, coexistence, community, and in general - society - that is the main subject of study of the philosophical direction under consideration. Even at the beginning of his work “Being and Nothingness”, Sartre sets the framework for his research and emphasizes that the study of the diversity of the individual’s action serves the sole purpose of “penetrating into the deep meaning of the relationship“ man-world ”[14]. nine0003  The philosopher crystallizes the thesis of responsibility in this way: “A person who decides on something and realizes that he chooses not only his own being, but that he is also a legislator, who simultaneously chooses all of humanity, cannot avoid a feeling of complete and deep responsibility. ”, “every person must say to himself: do I really have the right to act in such a way that humanity takes an example from my actions?”, “Our responsibility is much greater than we could imagine, since it applies to all of humanity”[4]. nine0003

The philosopher crystallizes the thesis of responsibility in this way: “A person who decides on something and realizes that he chooses not only his own being, but that he is also a legislator, who simultaneously chooses all of humanity, cannot avoid a feeling of complete and deep responsibility. ”, “every person must say to himself: do I really have the right to act in such a way that humanity takes an example from my actions?”, “Our responsibility is much greater than we could imagine, since it applies to all of humanity”[4]. nine0003  The screaming desire to oppose a new understanding of the world legal order and justification of the possibility of peaceful coexistence has become an incentive to develop new concepts of being. Both Sartre and Levinas, being contemporaries of these terrible events, presented their vision to the "world of the world." Existence itself is possible only if the key conditions are observed - respect for the freedom of the Other, recognition of existence, the subjectivity of each individual person, communication with the Other, responsibility for one's actions, the actions of the Other and all of humanity, sympathy, empathy. nine0003

The screaming desire to oppose a new understanding of the world legal order and justification of the possibility of peaceful coexistence has become an incentive to develop new concepts of being. Both Sartre and Levinas, being contemporaries of these terrible events, presented their vision to the "world of the world." Existence itself is possible only if the key conditions are observed - respect for the freedom of the Other, recognition of existence, the subjectivity of each individual person, communication with the Other, responsibility for one's actions, the actions of the Other and all of humanity, sympathy, empathy. nine0003

Also on the topic Self and Other in Structuralism and Existentialism

References

Learn more

It focuses on the question of human existence, and the feeling that there is no purpose or explanation at the core of existence. It holds that, as there is no God or any other transcendent force, the only way to counter this nothingness (and hence to find meaning in life) is by embracing existence.

It focuses on the question of human existence, and the feeling that there is no purpose or explanation at the core of existence. It holds that, as there is no God or any other transcendent force, the only way to counter this nothingness (and hence to find meaning in life) is by embracing existence. Although it has much in common with Nihilism, Existentialism is more a reaction against traditional philosophies, such as Rationalism, Empiricism and Positivism, that seek to discover an ultimate order and universal meaning in metaphysical principles or in the structure of the observed world. It asserts that people actually make decisions based on what has meaning to them, rather than what is rational.

Although it has much in common with Nihilism, Existentialism is more a reaction against traditional philosophies, such as Rationalism, Empiricism and Positivism, that seek to discover an ultimate order and universal meaning in metaphysical principles or in the structure of the observed world. It asserts that people actually make decisions based on what has meaning to them, rather than what is rational. Existence, then, is prior to essence (essence is the meaning that may be ascribed to life), contrary to traditional philosophical views dating back to the ancient Greeks. As Sartre put it: "At first [Man] is nothing. Only afterward will he be something, and he himself will have made what he will be."

Existence, then, is prior to essence (essence is the meaning that may be ascribed to life), contrary to traditional philosophical views dating back to the ancient Greeks. As Sartre put it: "At first [Man] is nothing. Only afterward will he be something, and he himself will have made what he will be." Thus, most Existentialists believe that personal experience and acting on one's own convictions are essential in arriving at the truth, and that the understanding of a situation by someone involved in that situation is superior to that of a detached, objective observer (similar to the concept of Subjectivism).

Thus, most Existentialists believe that personal experience and acting on one's own convictions are essential in arriving at the truth, and that the understanding of a situation by someone involved in that situation is superior to that of a detached, objective observer (similar to the concept of Subjectivism). The important factor for Existentialists is the freedom of choice to believe or not to believe.

The important factor for Existentialists is the freedom of choice to believe or not to believe. It can be argued that Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Arthur Schopenhauer were also important influences on the development of Existentialism, because the philosophies of Kierkegaard and Nietzsche were written in response or in opposition to them.

It can be argued that Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel and Arthur Schopenhauer were also important influences on the development of Existentialism, because the philosophies of Kierkegaard and Nietzsche were written in response or in opposition to them.

"Being and Nothingness" (1943) is his most important work, and his novels and plays, including "Nausea" (1938) and "No Exit (1944), helped to popularize the movement.

"Being and Nothingness" (1943) is his most important work, and his novels and plays, including "Nausea" (1938) and "No Exit (1944), helped to popularize the movement. Heidegger himself thought that Sartre had merely taken his own work and regressed it back to the subject-object orientated philosophy of Descartes and Husserl, which is exactly what Heidegger had been trying to free philosophy from. Some see Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908 - 1961) as a better Existentialist philosopher, particular for his incorporation of the body as our way of being in the world, and for his more complete analysis of perception (two areas in which Heidegger's work is often seen as deficient).

Heidegger himself thought that Sartre had merely taken his own work and regressed it back to the subject-object orientated philosophy of Descartes and Husserl, which is exactly what Heidegger had been trying to free philosophy from. Some see Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908 - 1961) as a better Existentialist philosopher, particular for his incorporation of the body as our way of being in the world, and for his more complete analysis of perception (two areas in which Heidegger's work is often seen as deficient).