Common personality traits

85 Examples of Personality Traits: The Positive and Negative

DESCRIPTION

purple circles with personality traits definition and example chart

SOURCE

Created by Karina Goto for YourDictionary

PERMISSION

Owned by YourDictionary, Copyright YourDictionary

Everyone has that one amazing friend who’s funny, smart, generous, and creative — in fact, just being around them makes you feel funny, smart, generous, and creative too. But what makes someone’s personality so attractive? Are they just a generally cool person, or is their particular set of personality traits just irresistible?

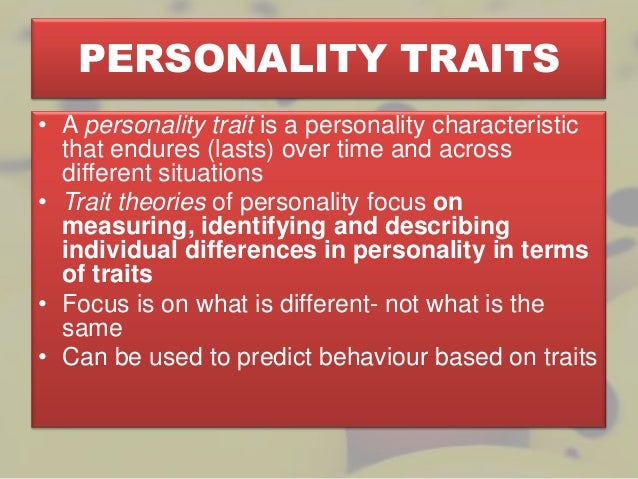

What Are Personality Traits?

A personality trait describes how a person tends to think, feel, and behave on an ongoing basis. Personality traits are characteristic of enduring behavioral and emotional patterns, rather than isolated occurrences.

For example, anyone can occasionally have a bad day and make a snappy remark. When this happens in isolation, it doesn't reflect a personality trait. However, when someone's typical behavior is to snap at people rather than communicating politely, then “irritable” is likely one of their personality traits.

Advertisement

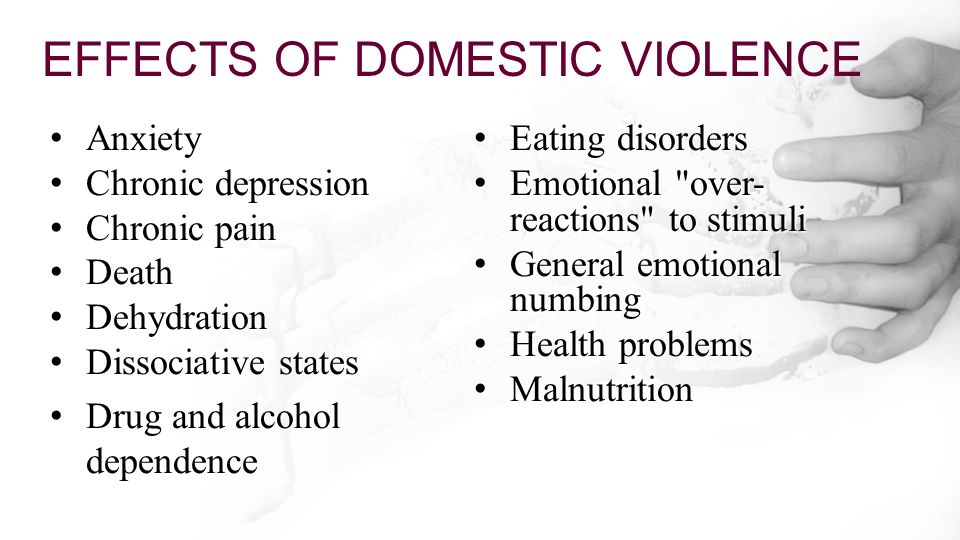

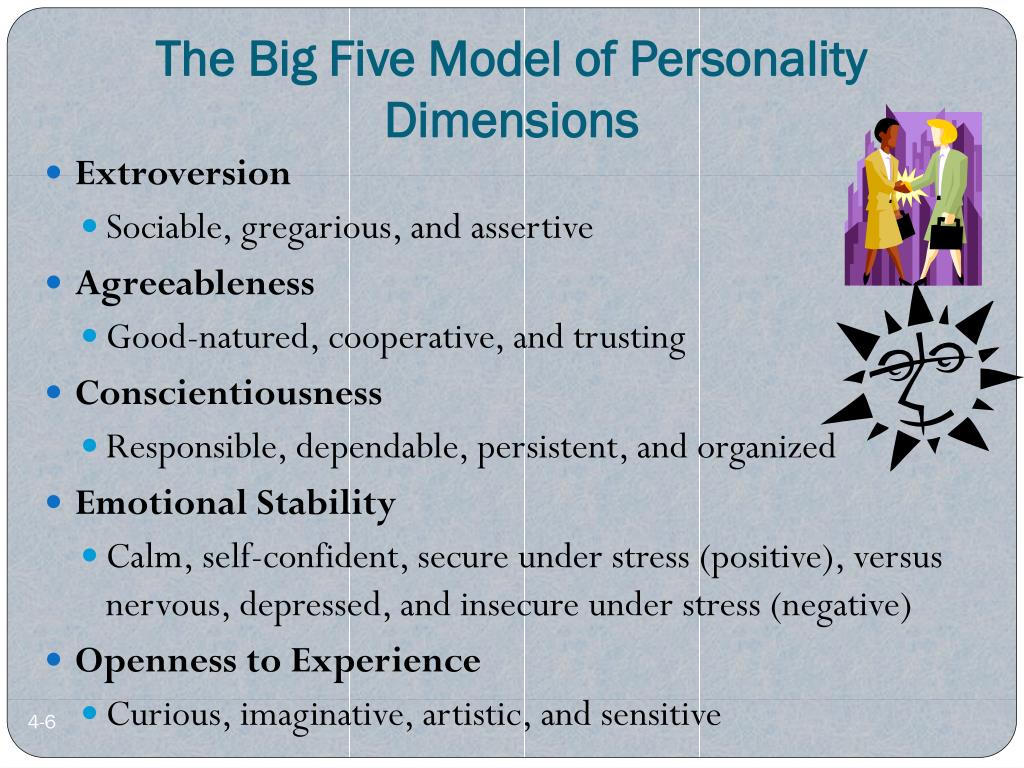

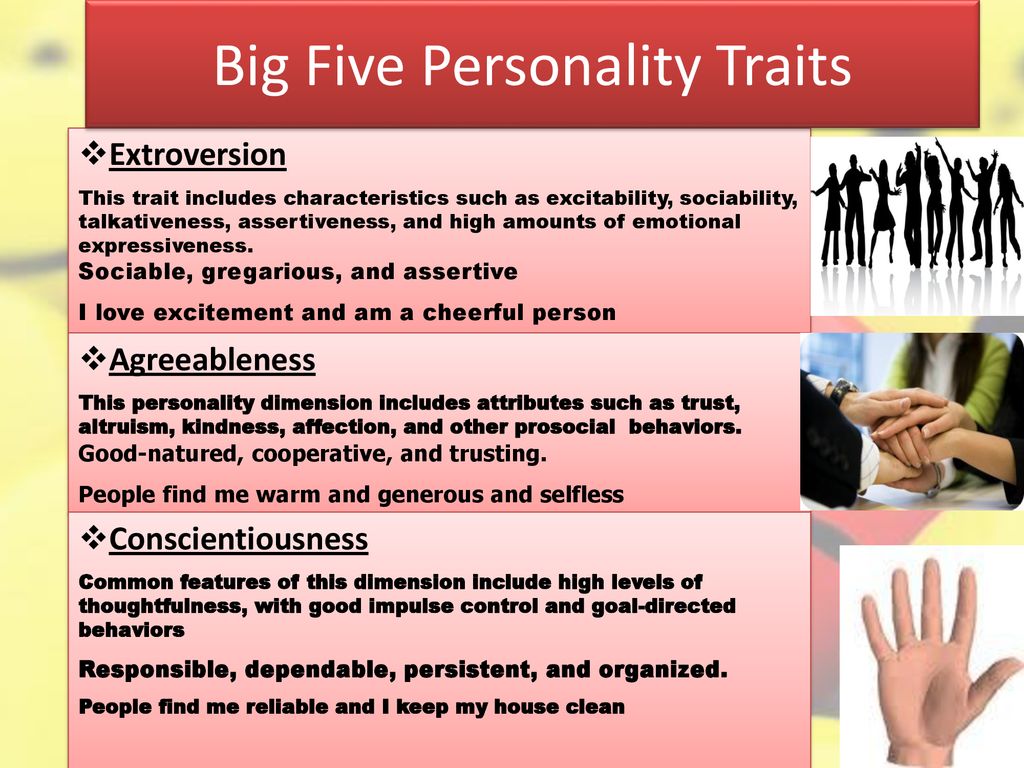

The Big Five Personality Traits

While there are hundreds of different personality trait examples that describe a person, psychologists often list five main personality traits, called the Big Five. They include:

- conscientiousness - the degree to which a person prefers to plan ahead rather than being spontaneous

- agreeableness - how strongly a person tends to be kind, sympathetic, and helpful to others

- neuroticism - the extent to which someone is inclined to worry or be temperamental

- openness - the extent to which a person has an appreciation for a variety of experiences

- extroversion - the extent to which a person tends to prefer being sociable, outgoing, and talkative

The combination of these traits can determine whether you are introverted or extroverted, open to new experiences or fearful or the unknown, agreeable or temperamental, and more.

Advertisement

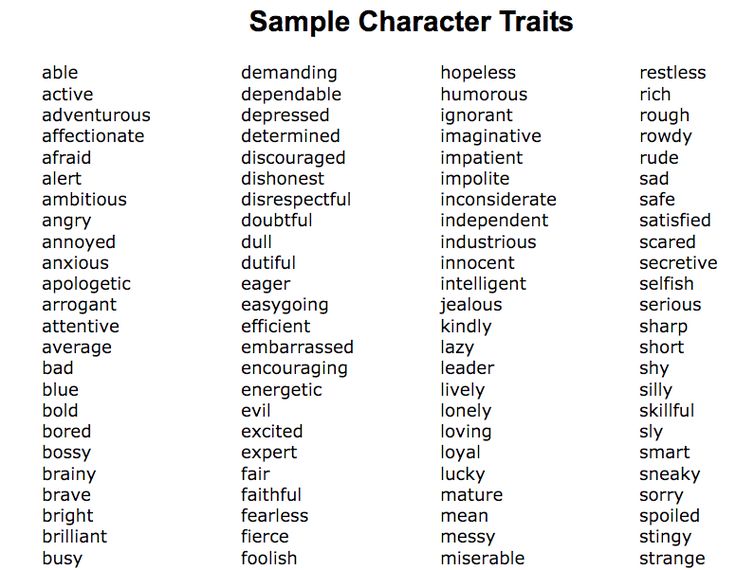

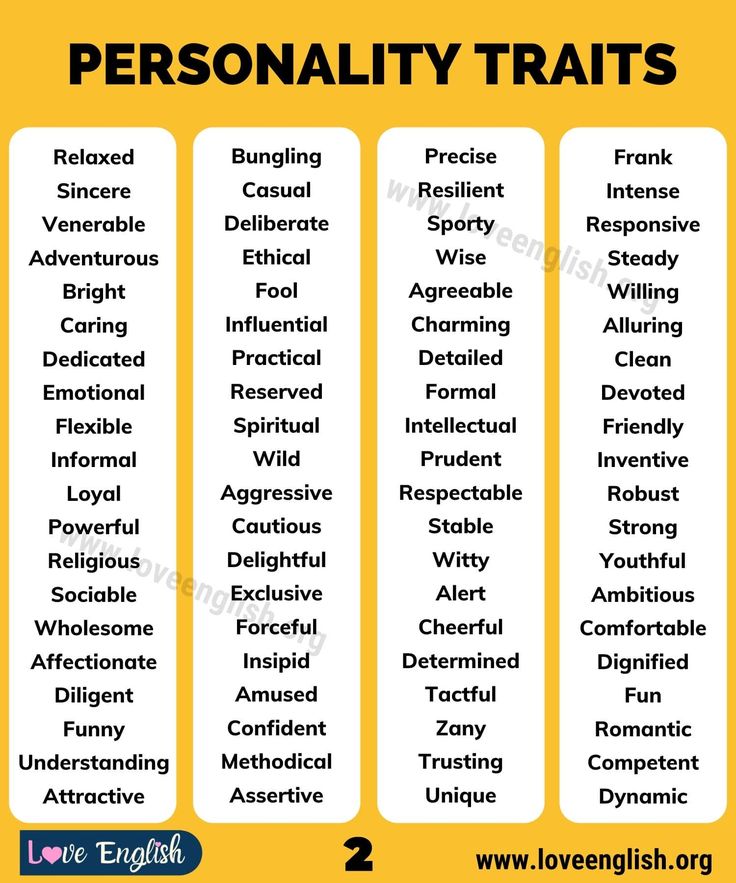

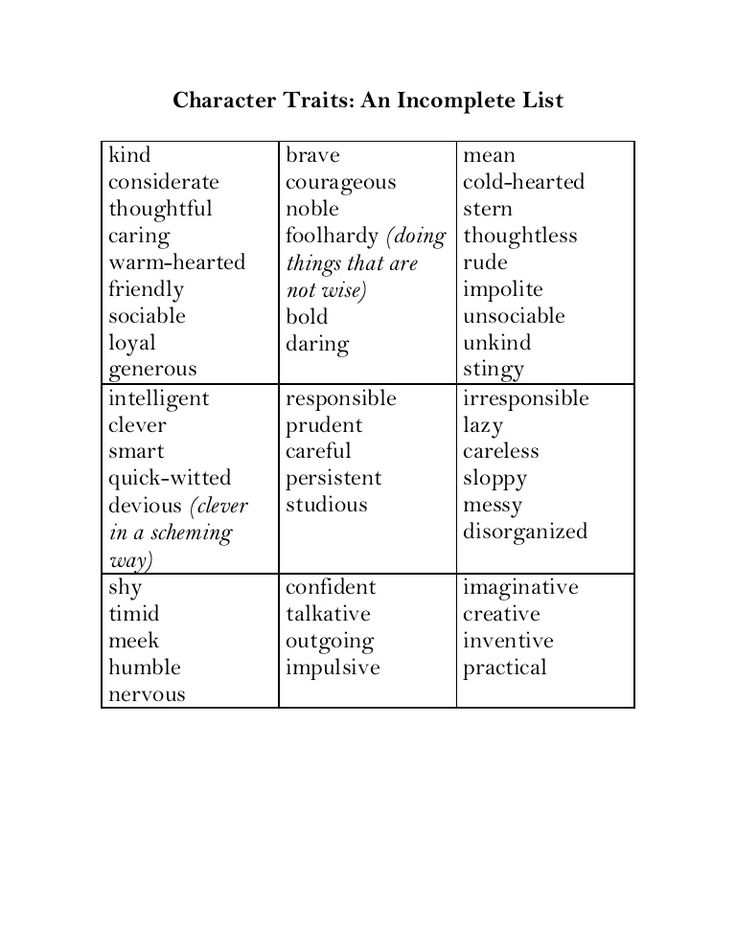

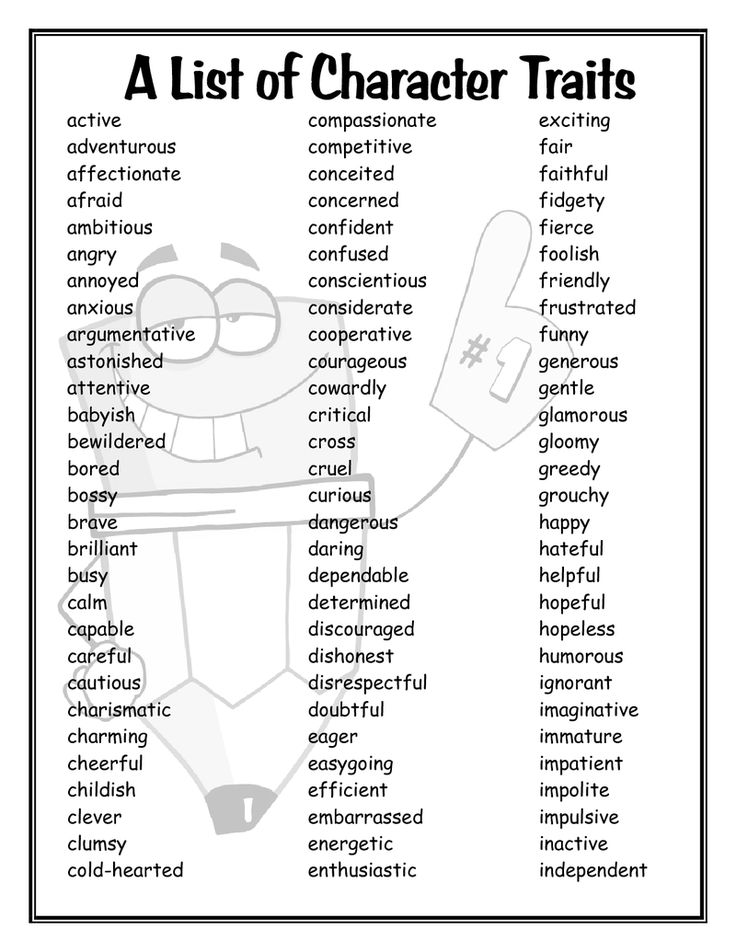

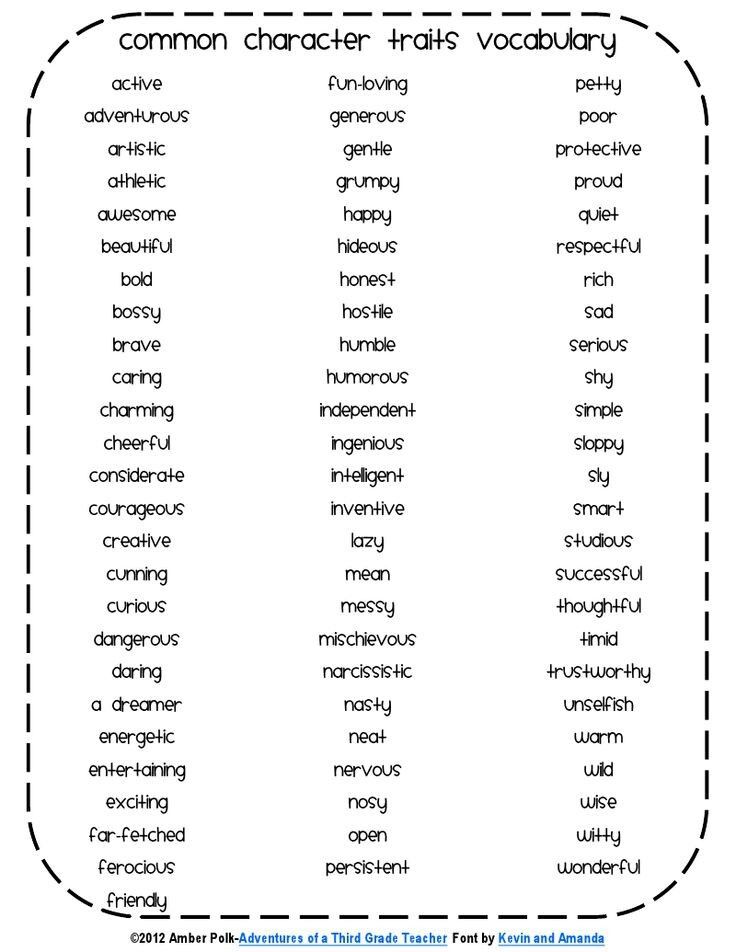

Personality Traits List

It would be nice if we could capture the entire human experience into five simple words. While the Big Five personality traits help us broadly define and explore one’s personality, there are many more examples of personality traits — both positive and negative.

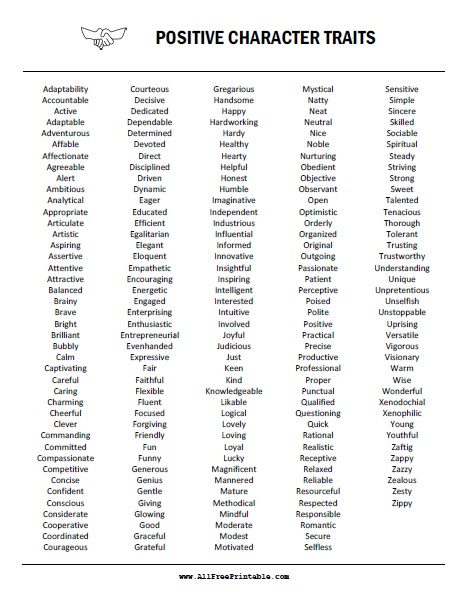

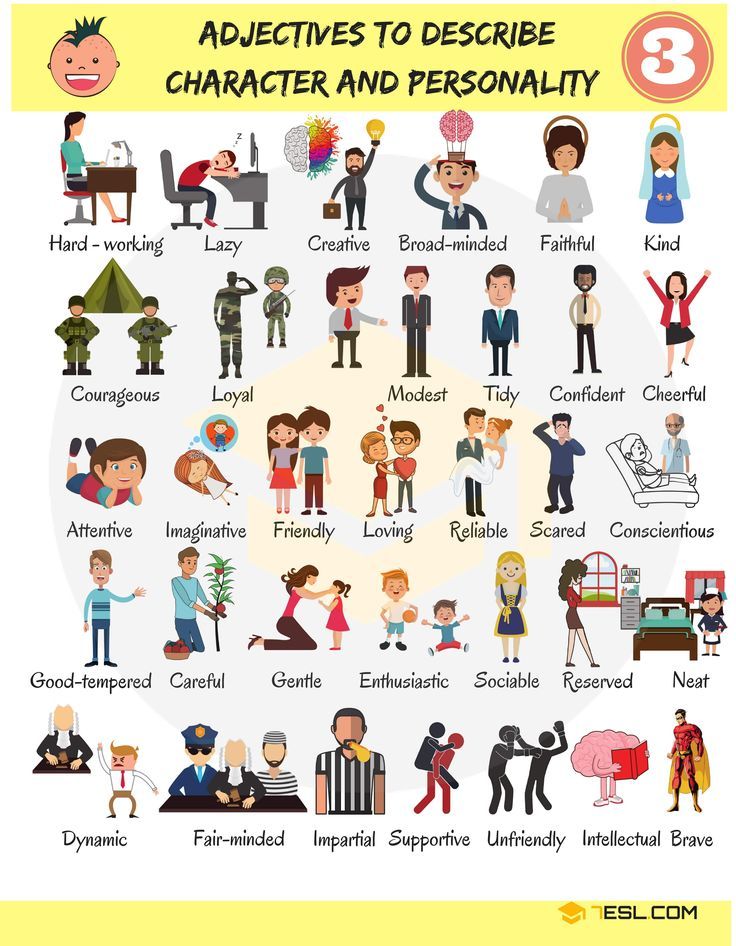

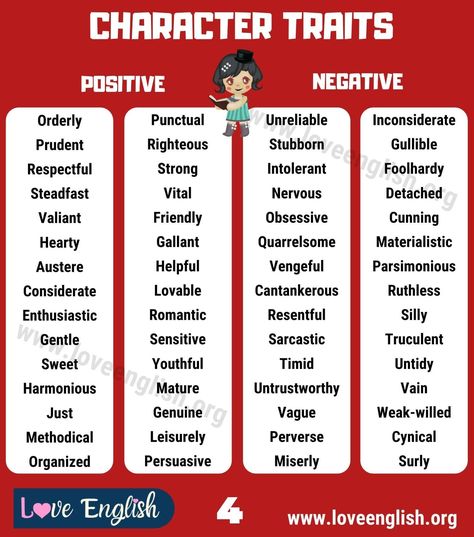

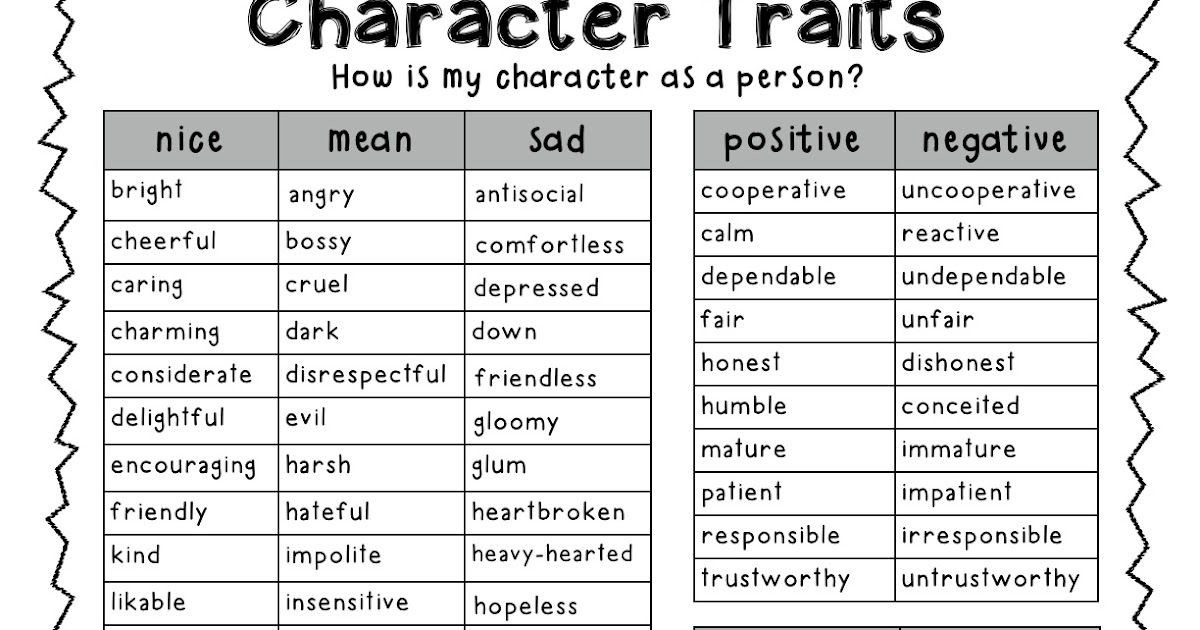

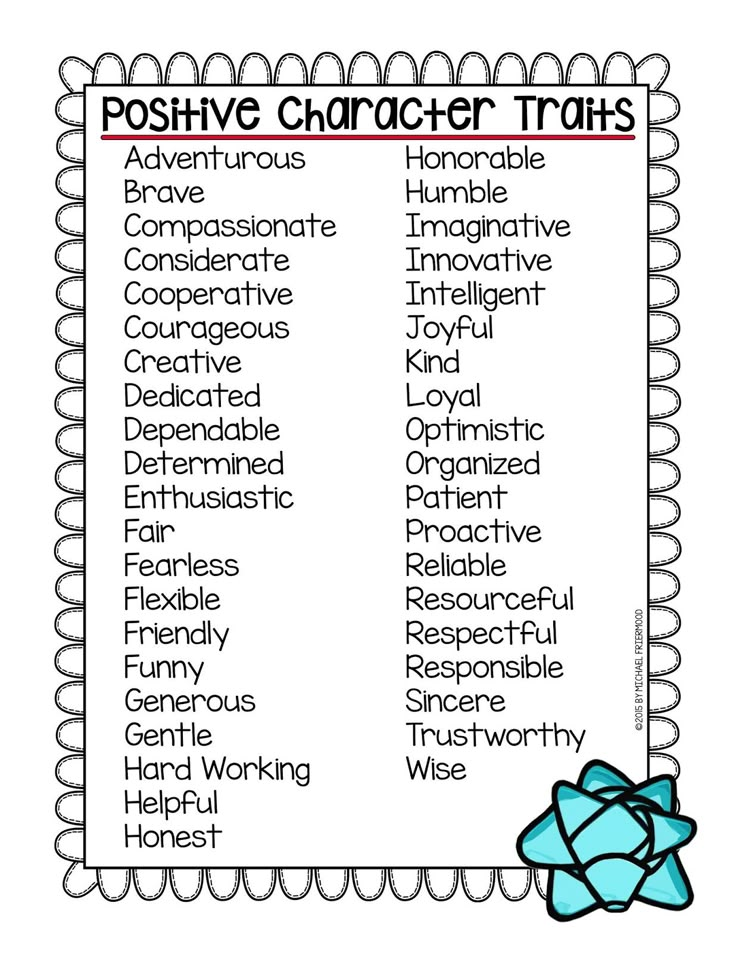

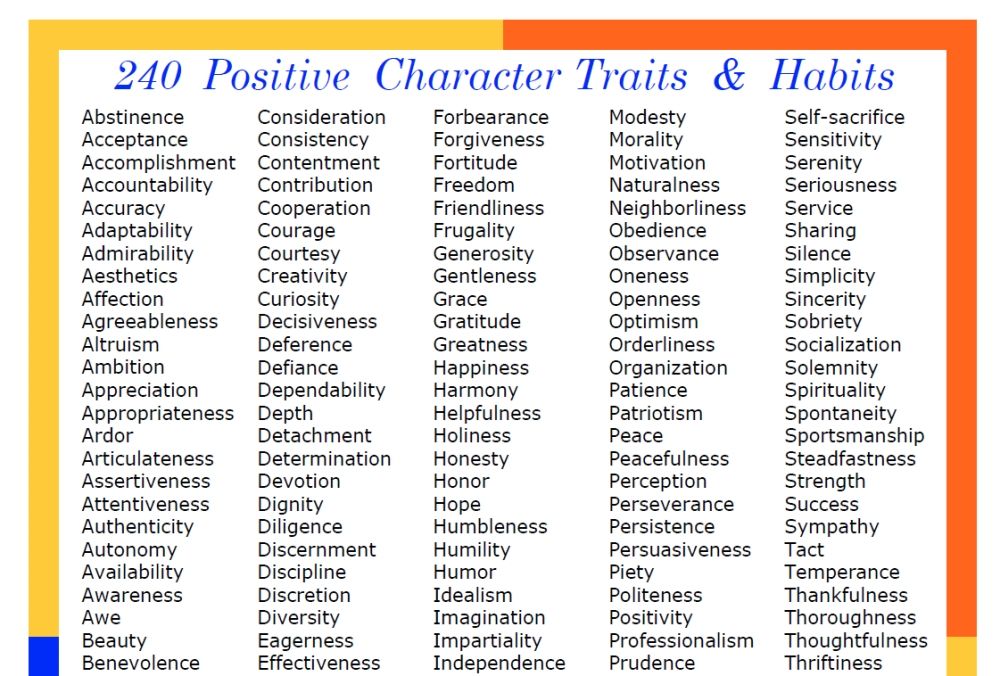

Examples of Positive Personality Traits

When someone always tells the truth, honesty is one of their personality traits. When they are the first to volunteer their time, you can remark on their generosity.

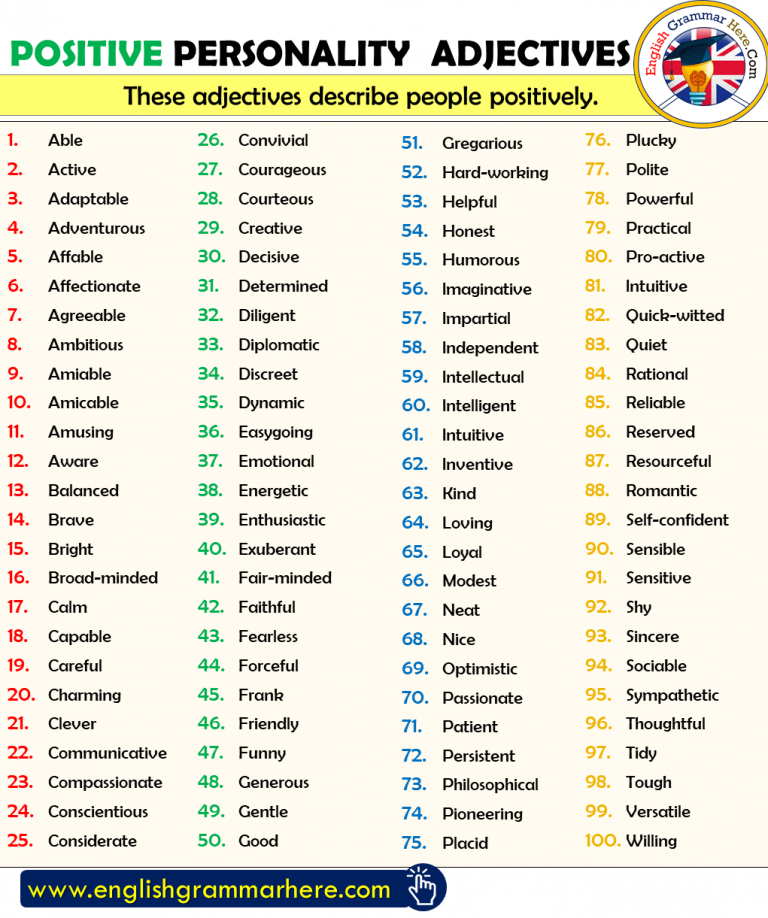

A pattern of positive behavior and attitude leads to a positive personality, marked by positive personality traits. These traits may include:

- accepting

- adaptable

- affable

- broad-minded

- charismatic

- compassionate

- competent

- confident

- congenial

- courageous

- creative

- determined

- discreet

- driven

- empathic

- enthusiastic

- exuberant

- fair

- friendly

- gregarious

- helpful

- honest

- humble

- independent

- insightful

- intelligent

- kind

- loyal

- mindful

- optimistic

- patient

- persistent

- precise

- reliable

- responsible

- sociable

- sympathetic

- tolerant

- trustworthy

- understanding

Advertisement

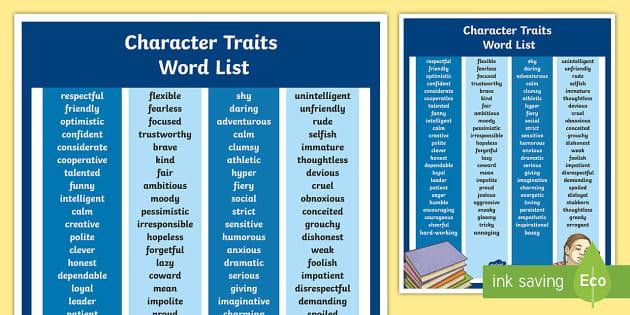

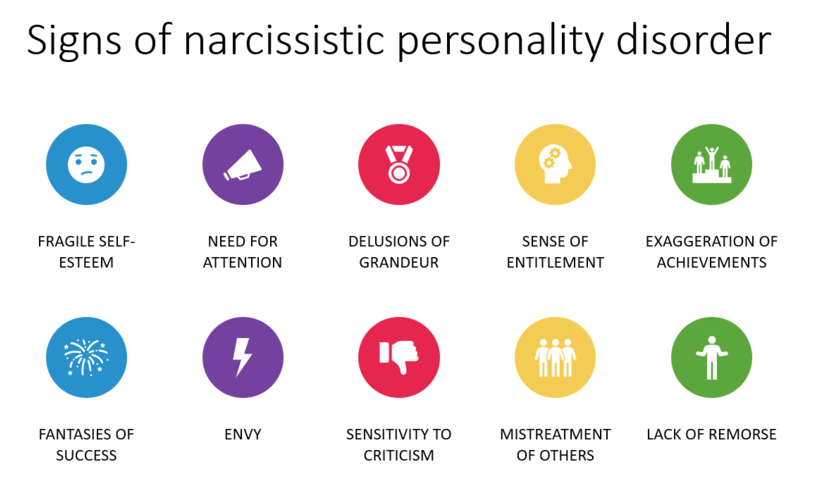

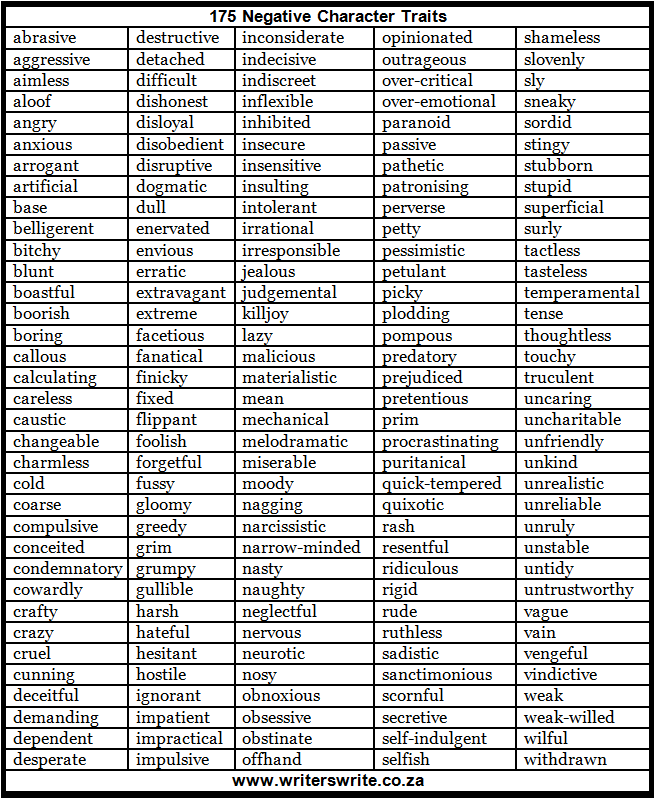

Examples of Negative Personality Traits

People are generally not all good or all bad, or all positive or all negative. Chances are that people have at least a few negative personality traits. (If any of these sound familiar, consider them an opportunity for personal growth.)

Chances are that people have at least a few negative personality traits. (If any of these sound familiar, consider them an opportunity for personal growth.)

- aggressive

- apathetic

- argumentative

- arrogant

- boorish

- bossy

- callous

- conceited

- cowardy

- dishonest

- disloyal

- disrespectful

- finicky

- forgetful

- greedy

- impatient

- impulsive

- indecisive

- jealous

- lazy

- malicious

- manipulative

- obnoxious

- pessimistic

- picky

- reckless

- rigid

- rude

- sarcastic

- self-centered

- selfish

- slovenly

- sneaky

- stingy

- surly

- thoughtless

- uncertain

- unfriendly

- unpredictable

- vulgar

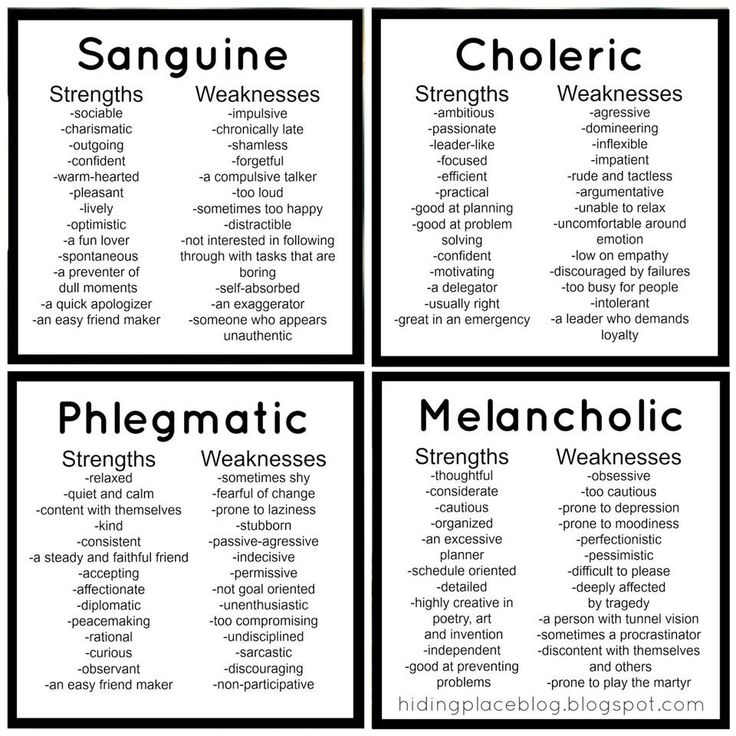

More Ways To Determine Personality Types

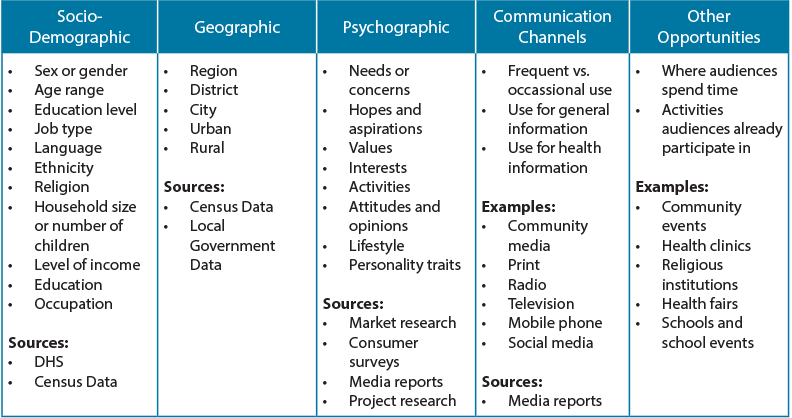

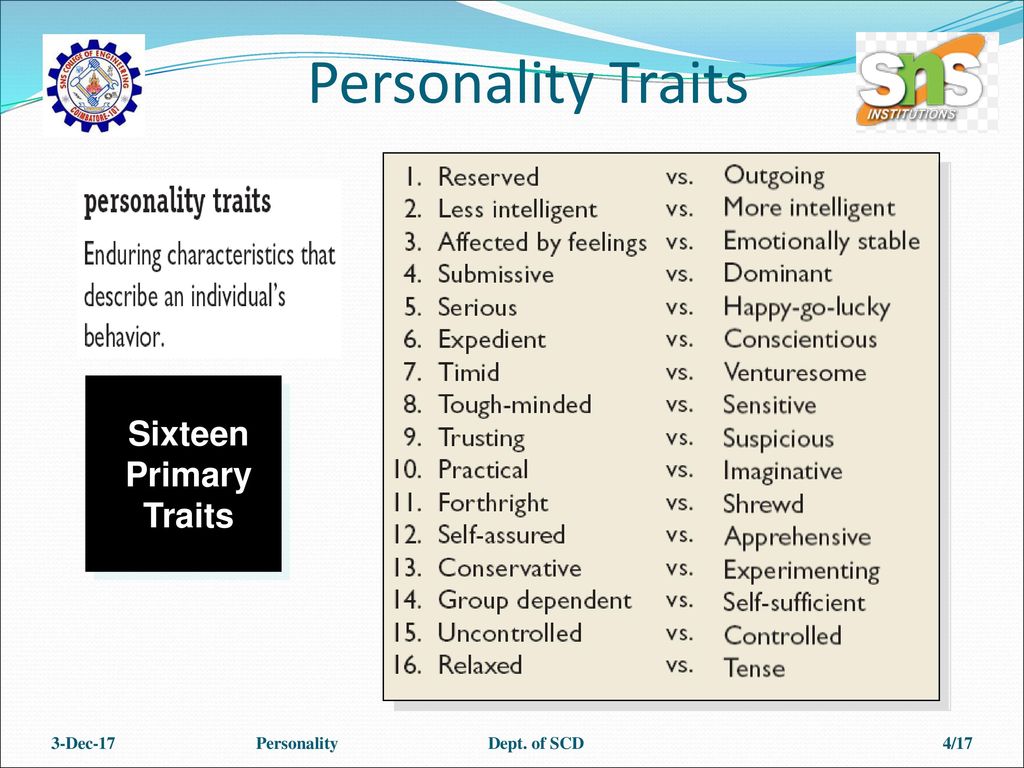

Identifying an individual's personality style is not an easy task. Personality is a complicated construct influenced by many factors. There are many ways to assess and label personality types, with each assessment measuring specific variables.

Personality is a complicated construct influenced by many factors. There are many ways to assess and label personality types, with each assessment measuring specific variables.

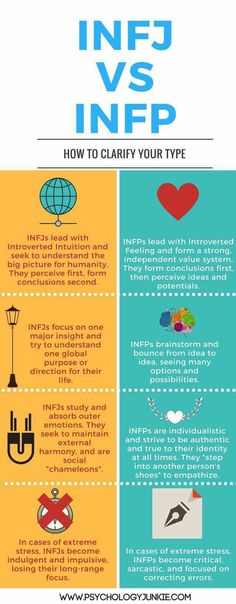

- Some personality assessments group personalities into four types based on letter labels (Type A, Type B, Type C, and Type D).

- The DISC theory of personality groups people into four types (Dominance, Influence, Steadfastness, and Conscientiousness).

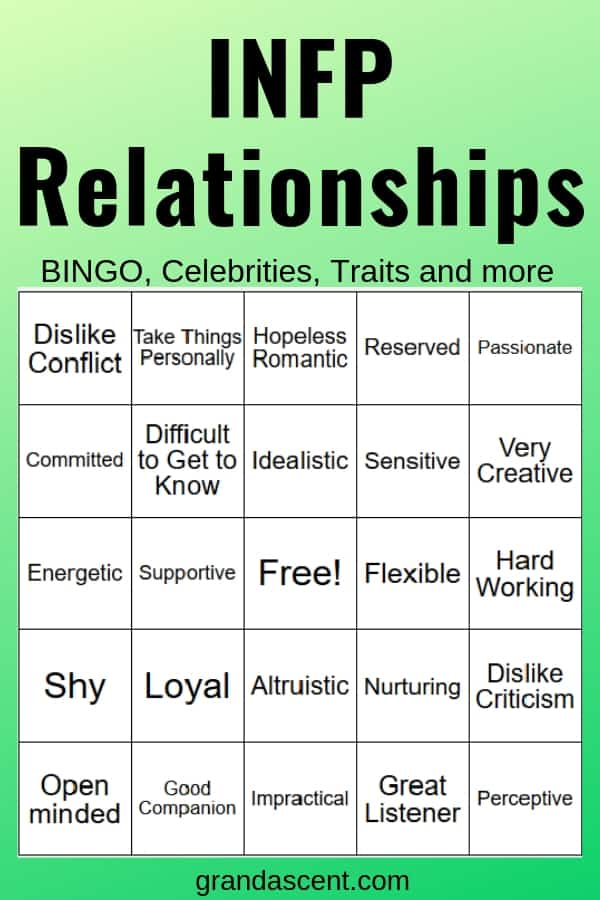

- According to the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator, there are sixteen different types, including ESTJ, INTP and 14 others.

Advertisement

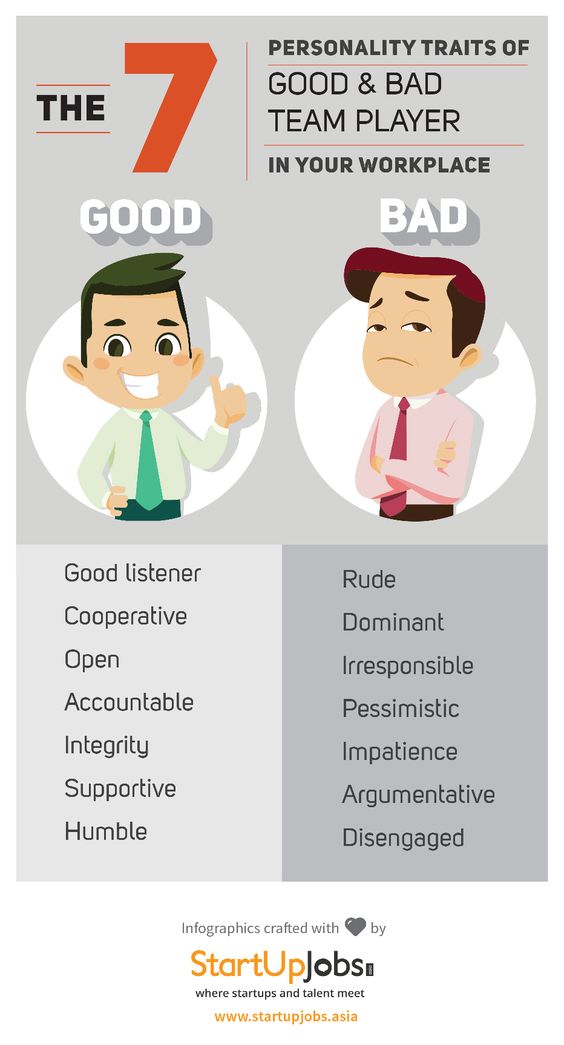

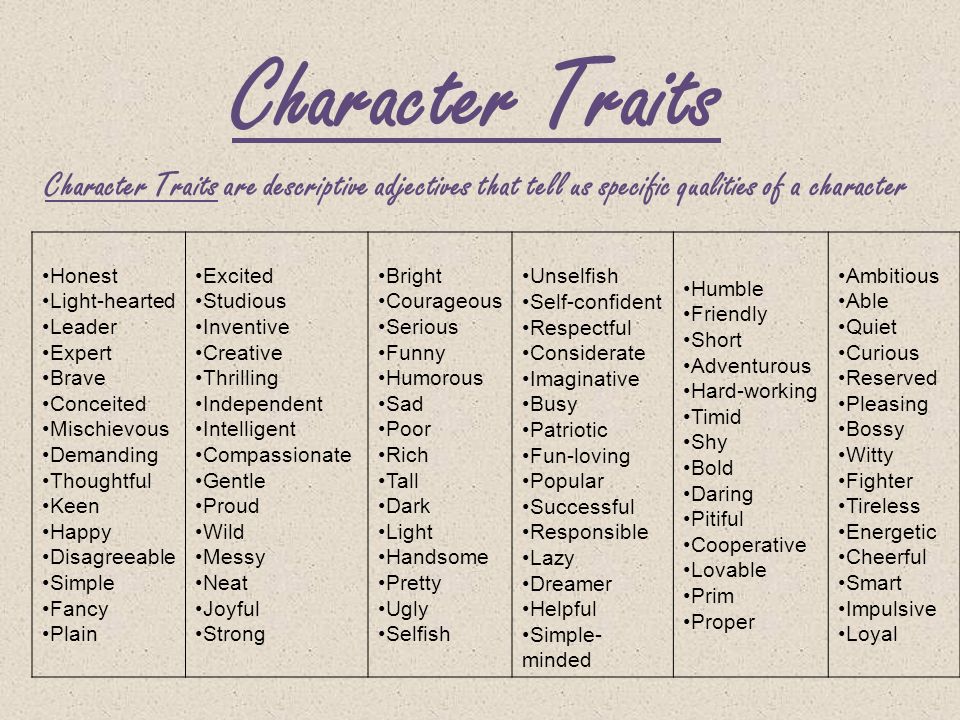

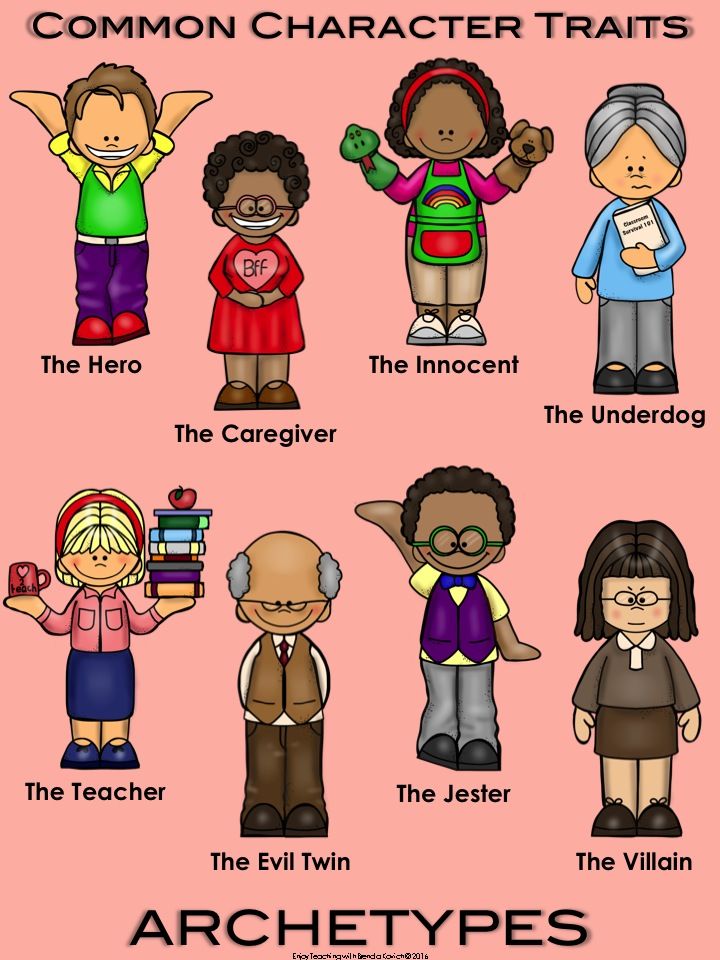

Personality Traits for Characters

While personality traits describe real people, character traits describe fictional characters. Authors use character traits, also known as characterization, to guide story development and to move their plot forward.

For example, a cowardly character may finally find the bravery they need by the end of a story. A self-centered character may learn the value of sharing with others in order to fulfill their goal.

A self-centered character may learn the value of sharing with others in order to fulfill their goal.

When these traits are negative and hold a character back from their goal, they’re called character flaws. A character must overcome these flaws in order to achieve their goals — unless the story is a tragedy, and their character flaw is the cause of their downfall.

It’s more difficult for real people to grow and change their personality traits (Wouldn’t it be nice if we could resolve our biggest personality flaws in a few pages?). However, we can take some cues from these fictional people and their character traits in order to achieve our own goals.

16.1 Personality Traits – Introduction to Psychology

Chapter 16. Personality

Edward Diener; Richard E. Lucas; and Jorden A. Cummings

Personality traits reflect people’s characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. Personality traits imply consistency and stability—someone who scores high on a specific trait like Extraversion is expected to be sociable in different situations and over time. Thus, trait psychology rests on the idea that people differ from one another in terms of where they stand on a set of basic trait dimensions that persist over time and across situations. The most widely used system of traits is called the Five-Factor Model. This system includes five broad traits that can be remembered with the acronym OCEAN: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Each of the major traits from the Big Five can be divided into facets to give a more fine-grained analysis of someone’s personality. In addition, some trait theorists argue that there are other traits that cannot be completely captured by the Five-Factor Model. Critics of the trait concept argue that people do not act consistently from one situation to the next and that people are very influenced by situational forces. Thus, one major debate in the field concerns the relative power of people’s traits versus the situations in which they find themselves as predictors of their behaviour.

Thus, trait psychology rests on the idea that people differ from one another in terms of where they stand on a set of basic trait dimensions that persist over time and across situations. The most widely used system of traits is called the Five-Factor Model. This system includes five broad traits that can be remembered with the acronym OCEAN: Openness, Conscientiousness, Extraversion, Agreeableness, and Neuroticism. Each of the major traits from the Big Five can be divided into facets to give a more fine-grained analysis of someone’s personality. In addition, some trait theorists argue that there are other traits that cannot be completely captured by the Five-Factor Model. Critics of the trait concept argue that people do not act consistently from one situation to the next and that people are very influenced by situational forces. Thus, one major debate in the field concerns the relative power of people’s traits versus the situations in which they find themselves as predictors of their behaviour.

Learning Objectives

- List and describe the “Big Five” (“OCEAN”) personality traits that comprise the Five-Factor Model of personality.

- Describe how the facet approach extends broad personality traits.

- Explain a critique of the personality-trait concept.

- Describe in what ways personality traits may be manifested in everyday behaviour.

- Describe each of the Big Five personality traits, and the low and high end of the dimension.

- Give examples of each of the Big Five personality traits, including both a low and high example.

- Describe the person-situation debate and how situational factors might complicate attempts to define and measure personality traits.

When we observe people around us, one of the first things that strikes us is how different people are from one another. Some people are very talkative while others are very quiet. Some are active whereas others are couch potatoes. Some worry a lot, others almost never seem anxious. Each time we use one of these words, words like “talkative,” “quiet,” “active,” or “anxious,” to describe those around us, we are talking about a person’s personality—the characteristic ways that people differ from one another. Personality psychologists try to describe and understand these differences.

Although there are many ways to think about the personalities that people have, Gordon Allport and other “personologists” claimed that we can best understand the differences between individuals by understanding their personality traits. Personality traits reflect basic dimensions on which people differ (Matthews, Deary, & Whiteman, 2003). According to trait psychologists, there are a limited number of these dimensions (dimensions like Extraversion, Conscientiousness, or Agreeableness), and each individual falls somewhere on each dimension, meaning that they could be low, medium, or high on any specific trait.

An important feature of personality traits is that they reflect continuous distributions rather than distinct personality types. This means that when personality psychologists talk about Introverts and Extraverts, they are not really talking about two distinct types of people who are completely and qualitatively different from one another. Instead, they are talking about people who score relatively low or relatively high along a continuous distribution. In fact, when personality psychologists measure traits like Extraversion, they typically find that most people score somewhere in the middle, with smaller numbers showing more extreme levels. Figure 16.2 shows the distribution of Extraversion scores from a survey of thousands of people. As you can see, most people report being moderately, but not extremely, extraverted, with fewer people reporting very high or very low scores.

Figure 16.2 Distribution of Extraversion Scores in a Sample Higher bars mean that more people have scores of that level. This figure shows that most people score towards the middle of the extraversion scale, with fewer people who are highly extraverted or highly introverted.

This figure shows that most people score towards the middle of the extraversion scale, with fewer people who are highly extraverted or highly introverted.There are three criteria that are characterize personality traits: (1) consistency, (2) stability, and (3) individual differences.

- To have a personality trait, individuals must be somewhat consistent across situations in their behaviours related to the trait. For example, if they are talkative at home, they tend also to be talkative at work.

- Individuals with a trait are also somewhat stable over time in behaviours related to the trait. If they are talkative, for example, at age 30, they will also tend to be talkative at age 40.

- People differ from one another on behaviours related to the trait. Using speech is not a personality trait and neither is walking on two feet—virtually all individuals do these activities, and there are almost no individual differences. But people differ on how frequently they talk and how active they are, and thus personality traits such as Talkativeness and Activity Level do exist.

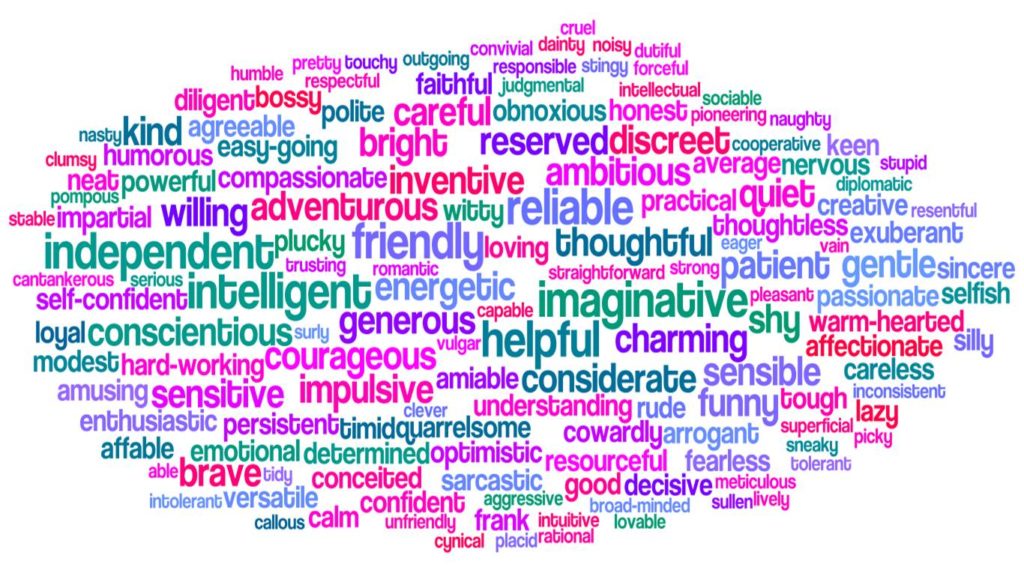

A challenge of the trait approach was to discover the major traits on which all people differ. Scientists for many decades generated hundreds of new traits, so that it was soon difficult to keep track and make sense of them. For instance, one psychologist might focus on individual differences in “friendliness,” whereas another might focus on the highly related concept of “sociability.” Scientists began seeking ways to reduce the number of traits in some systematic way and to discover the basic traits that describe most of the differences between people.

The way that Gordon Allport and his colleague Henry Odbert approached this was to search the dictionary for all descriptors of personality (Allport & Odbert, 1936). Their approach was guided by the lexical hypothesis, which states that all important personality characteristics should be reflected in the language that we use to describe other people. Therefore, if we want to understand the fundamental ways in which people differ from one another, we can turn to the words that people use to describe one another. So if we want to know what words people use to describe one another, where should we look? Allport and Odbert looked in the most obvious place—the dictionary. Specifically, they took all the personality descriptors that they could find in the dictionary (they started with almost 18,000 words but quickly reduced that list to a more manageable number) and then used statistical techniques to determine which words “went together.” In other words, if everyone who said that they were “friendly” also said that they were “sociable,” then this might mean that personality psychologists would only need a single trait to capture individual differences in these characteristics. Statistical techniques were used to determine whether a small number of dimensions might underlie all of the thousands of words we use to describe people.

So if we want to know what words people use to describe one another, where should we look? Allport and Odbert looked in the most obvious place—the dictionary. Specifically, they took all the personality descriptors that they could find in the dictionary (they started with almost 18,000 words but quickly reduced that list to a more manageable number) and then used statistical techniques to determine which words “went together.” In other words, if everyone who said that they were “friendly” also said that they were “sociable,” then this might mean that personality psychologists would only need a single trait to capture individual differences in these characteristics. Statistical techniques were used to determine whether a small number of dimensions might underlie all of the thousands of words we use to describe people.

The Five-Factor Model of Personality

Research that used the lexical approach showed that many of the personality descriptors found in the dictionary do indeed overlap. In other words, many of the words that we use to describe people are synonyms. Thus, if we want to know what a person is like, we do not necessarily need to ask how sociable they are, how friendly they are, and how gregarious they are. Instead, because sociable people tend to be friendly and gregarious, we can summarize this personality dimension with a single term. Someone who is sociable, friendly, and gregarious would typically be described as an “Extravert.” Once we know she is an extravert, we can assume that she is sociable, friendly, and gregarious.

In other words, many of the words that we use to describe people are synonyms. Thus, if we want to know what a person is like, we do not necessarily need to ask how sociable they are, how friendly they are, and how gregarious they are. Instead, because sociable people tend to be friendly and gregarious, we can summarize this personality dimension with a single term. Someone who is sociable, friendly, and gregarious would typically be described as an “Extravert.” Once we know she is an extravert, we can assume that she is sociable, friendly, and gregarious.

Statistical methods (specifically, a technique called factor analysis) helped to determine whether a small number of dimensions underlie the diversity of words that people like Allport and Odbert identified. The most widely accepted system to emerge from this approach was “The Big Five” or “Five-Factor Model” (Goldberg, 1990; McCrae & John, 1992; McCrae & Costa, 1987). The Big Five comprises five major traits shown in the Figure 16. 3 below. A way to remember these five is with the acronym OCEAN (O is for Openness; C is for Conscientiousness; E is for Extraversion; A is for Agreeableness; N is for Neuroticism). Figure 16.4 provides descriptions of people who would score high and low on each of these traits.

3 below. A way to remember these five is with the acronym OCEAN (O is for Openness; C is for Conscientiousness; E is for Extraversion; A is for Agreeableness; N is for Neuroticism). Figure 16.4 provides descriptions of people who would score high and low on each of these traits.

Scores on the Big Five traits are mostly independent. That means that a person’s standing on one trait tells very little about their standing on the other traits of the Big Five. For example, a person can be extremely high in Extraversion and be either high or low on Neuroticism. Similarly, a person can be low in Agreeableness and be either high or low in Conscientiousness. Thus, in the Five-Factor Model, you need five scores to describe most of an individual’s personality.

In the Appendix to this module, we present a short scale to assess the Five-Factor Model of personality (Donnellan, Oswald, Baird, & Lucas, 2006). You can take this test to see where you stand in terms of your Big Five scores. John Johnson has also created a helpful website that has personality scales that can be used and taken by the general public: http://www.personal.psu.edu/j5j/IPIP/ipipneo120.htm. After seeing your scores, you can judge for yourself whether you think such tests are valid.

You can take this test to see where you stand in terms of your Big Five scores. John Johnson has also created a helpful website that has personality scales that can be used and taken by the general public: http://www.personal.psu.edu/j5j/IPIP/ipipneo120.htm. After seeing your scores, you can judge for yourself whether you think such tests are valid.

Traits are important and interesting because they describe stable patterns of behaviour that persist for long periods of time (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005). Importantly, these stable patterns can have broad-ranging consequences for many areas of our life (Roberts, Kuncel, Shiner, Caspi, & Goldberg, 2007). For instance, think about the factors that determine success in college. If you were asked to guess what factors predict good grades in college, you might guess something like intelligence. This guess would be correct, but we know much more about who is likely to do well. Specifically, personality researchers have also found the personality traits like Conscientiousness play an important role in college and beyond, probably because highly conscientious individuals study hard, get their work done on time, and are less distracted by nonessential activities that take time away from school work. In addition, highly conscientious people are often healthier than people low in conscientiousness because they are more likely to maintain healthy diets, to exercise, and to follow basic safety procedures like wearing seat belts or bicycle helmets. Over the long term, this consistent pattern of behaviours can add up to meaningful differences in health and longevity. Thus, personality traits are not just a useful way to describe people you know; they actually help psychologists predict how good a worker someone will be, how long he or she will live, and the types of jobs and activities the person will enjoy. Thus, there is growing interest in personality psychology among psychologists who work in applied settings, such as health psychology or organizational psychology.

In addition, highly conscientious people are often healthier than people low in conscientiousness because they are more likely to maintain healthy diets, to exercise, and to follow basic safety procedures like wearing seat belts or bicycle helmets. Over the long term, this consistent pattern of behaviours can add up to meaningful differences in health and longevity. Thus, personality traits are not just a useful way to describe people you know; they actually help psychologists predict how good a worker someone will be, how long he or she will live, and the types of jobs and activities the person will enjoy. Thus, there is growing interest in personality psychology among psychologists who work in applied settings, such as health psychology or organizational psychology.

So how does it feel to be told that your entire personality can be summarized with scores on just five personality traits? Do you think these five scores capture the complexity of your own and others’ characteristic patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours? Most people would probably say no, pointing to some exception in their behaviour that goes against the general pattern that others might see. For instance, you may know people who are warm and friendly and find it easy to talk with strangers at a party yet are terrified if they have to perform in front of others or speak to large groups of people. The fact that there are different ways of being extraverted or conscientious shows that there is value in considering lower-level units of personality that are more specific than the Big Five traits. These more specific, lower-level units of personality are often called facets.

For instance, you may know people who are warm and friendly and find it easy to talk with strangers at a party yet are terrified if they have to perform in front of others or speak to large groups of people. The fact that there are different ways of being extraverted or conscientious shows that there is value in considering lower-level units of personality that are more specific than the Big Five traits. These more specific, lower-level units of personality are often called facets.

To give you a sense of what these narrow units are like, Figure 16.5 shows facets for each of the Big Five traits. It is important to note that although personality researchers generally agree about the value of the Big Five traits as a way to summarize one’s personality, there is no widely accepted list of facets that should be studied. The list seen here, based on work by researchers Paul Costa and Jeff McCrae, thus reflects just one possible list among many. It should, however, give you an idea of some of the facets making up each of the Five-Factor Model.

Facets can be useful because they provide more specific descriptions of what a person is like. For instance, if we take our friend who loves parties but hates public speaking, we might say that this person scores high on the “gregariousness” and “warmth” facets of extraversion, while scoring lower on facets such as “assertiveness” or “excitement-seeking.” This precise profile of facet scores not only provides a better description, it might also allow us to better predict how this friend will do in a variety of different jobs (for example, jobs that require public speaking versus jobs that involve one-on-one interactions with customers; Paunonen & Ashton, 2001). Because different facets within a broad, global trait like extraversion tend to go together (those who are gregarious are often but not always assertive), the broad trait often provides a useful summary of what a person is like. But when we really want to know a person, facet scores add to our knowledge in important ways.

Despite the popularity of the Five-Factor Model, it is certainly not the only model that exists. Some suggest that there are more than five major traits, or perhaps even fewer. For example, in one of the first comprehensive models to be proposed, Hans Eysenck suggested that Extraversion and Neuroticism are most important. Eysenck believed that by combining people’s standing on these two major traits, we could account for many of the differences in personality that we see in people (Eysenck, 1981). So for instance, a neurotic introvert would be shy and nervous, while a stable introvert might avoid social situations and prefer solitary activities, but he may do so with a calm, steady attitude and little anxiety or emotion. Interestingly, Eysenck attempted to link these two major dimensions to underlying differences in people’s biology. For instance, he suggested that introverts experienced too much sensory stimulation and arousal, which made them want to seek out quiet settings and less stimulating environments. More recently, Jeffrey Gray suggested that these two broad traits are related to fundamental reward and avoidance systems in the brain—extraverts might be motivated to seek reward and thus exhibit assertive, reward-seeking behaviour, whereas people high in neuroticism might be motivated to avoid punishment and thus may experience anxiety as a result of their heightened awareness of the threats in the world around them (Gray, 1981. This model has since been updated; see Gray & McNaughton, 2000). These early theories have led to a burgeoning interest in identifying the physiological underpinnings of the individual differences that we observe.

More recently, Jeffrey Gray suggested that these two broad traits are related to fundamental reward and avoidance systems in the brain—extraverts might be motivated to seek reward and thus exhibit assertive, reward-seeking behaviour, whereas people high in neuroticism might be motivated to avoid punishment and thus may experience anxiety as a result of their heightened awareness of the threats in the world around them (Gray, 1981. This model has since been updated; see Gray & McNaughton, 2000). These early theories have led to a burgeoning interest in identifying the physiological underpinnings of the individual differences that we observe.

Another revision of the Big Five is the HEXACO model of traits (Ashton & Lee, 2007). This model is similar to the Big Five, but it posits slightly different versions of some of the traits, and its proponents argue that one important class of individual differences was omitted from the Five-Factor Model. The HEXACO adds Honesty-Humility as a sixth dimension of personality. People high in this trait are sincere, fair, and modest, whereas those low in the trait are manipulative, narcissistic, and self-centered. Thus, trait theorists are agreed that personality traits are important in understanding behaviour, but there are still debates on the exact number and composition of the traits that are most important.

People high in this trait are sincere, fair, and modest, whereas those low in the trait are manipulative, narcissistic, and self-centered. Thus, trait theorists are agreed that personality traits are important in understanding behaviour, but there are still debates on the exact number and composition of the traits that are most important.

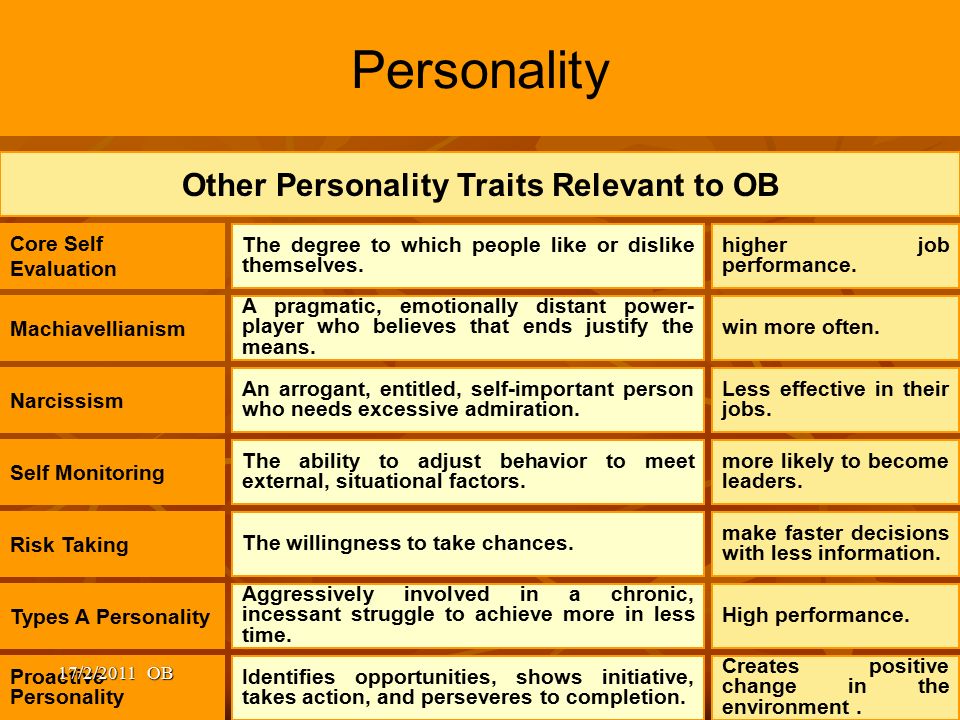

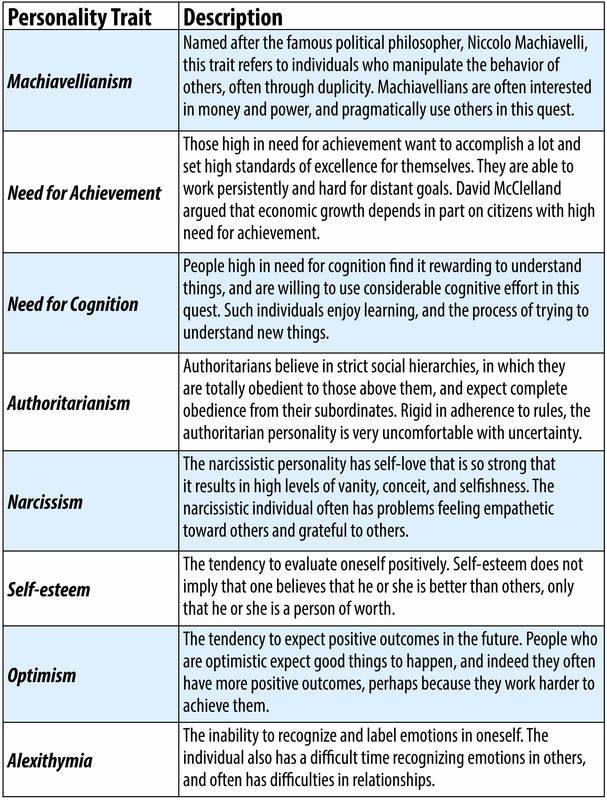

There are other important traits that are not included in comprehensive models like the Big Five. Although the five factors capture much that is important about personality, researchers have suggested other traits that capture interesting aspects of our behaviour. In Figure 16.6 below we present just a few, out of hundreds, of the other traits that have been studied by personologists.

Figure 16.6 Other Traits Beyond Those Included in the Big FiveNot all of the above traits are currently popular with scientists, yet each of them has experienced popularity in the past. Although the Five-Factor Model has been the target of more rigorous research than some of the traits above, these additional personality characteristics give a good idea of the wide range of behaviours and attitudes that traits can cover.

The ideas described in this module should probably seem familiar, if not obvious to you. When asked to think about what our friends, enemies, family members, and colleagues are like, some of the first things that come to mind are their personality characteristics. We might think about how warm and helpful our first teacher was, how irresponsible and careless our brother is, or how demanding and insulting our first boss was. Each of these descriptors reflects a personality trait, and most of us generally think that the descriptions that we use for individuals accurately reflect their “characteristic pattern of thoughts, feelings, and behaviours,” or in other words, their personality.

But what if this idea were wrong? What if our belief in personality traits were an illusion and people are not consistent from one situation to the next? This was a possibility that shook the foundation of personality psychology in the late 1960s when Walter Mischel published a book called Personality and Assessment (1968). In this book, Mischel suggested that if one looks closely at people’s behaviour across many different situations, the consistency is really not that impressive. In other words, children who cheat on tests at school may steadfastly follow all rules when playing games and may never tell a lie to their parents. In other words, he suggested, there may not be any general trait of honesty that links these seemingly related behaviours. Furthermore, Mischel suggested that observers may believe that broad personality traits like honesty exist, when in fact, this belief is an illusion. The debate that followed the publication of Mischel’s book was called the person-situation debate because it pitted the power of personality against the power of situational factors as determinants of the behaviour that people exhibit.

In this book, Mischel suggested that if one looks closely at people’s behaviour across many different situations, the consistency is really not that impressive. In other words, children who cheat on tests at school may steadfastly follow all rules when playing games and may never tell a lie to their parents. In other words, he suggested, there may not be any general trait of honesty that links these seemingly related behaviours. Furthermore, Mischel suggested that observers may believe that broad personality traits like honesty exist, when in fact, this belief is an illusion. The debate that followed the publication of Mischel’s book was called the person-situation debate because it pitted the power of personality against the power of situational factors as determinants of the behaviour that people exhibit.

Because of the findings that Mischel emphasized, many psychologists focused on an alternative to the trait perspective. Instead of studying broad, context-free descriptions, like the trait terms we’ve described so far, Mischel thought that psychologists should focus on people’s distinctive reactions to specific situations. For instance, although there may not be a broad and general trait of honesty, some children may be especially likely to cheat on a test when the risk of being caught is low and the rewards for cheating are high. Others might be motivated by the sense of risk involved in cheating and may do so even when the rewards are not very high. Thus, the behaviour itself results from the child’s unique evaluation of the risks and rewards present at that moment, along with her evaluation of her abilities and values. Because of this, the same child might act very differently in different situations. Thus, Mischel thought that specific behaviours were driven by the interaction between very specific, psychologically meaningful features of the situation in which people found themselves, the person’s unique way of perceiving that situation, and his or her abilities for dealing with it. Mischel and others argued that it was these social-cognitive processes that underlie people’s reactions to specific situations that provide some consistency when situational features are the same.

For instance, although there may not be a broad and general trait of honesty, some children may be especially likely to cheat on a test when the risk of being caught is low and the rewards for cheating are high. Others might be motivated by the sense of risk involved in cheating and may do so even when the rewards are not very high. Thus, the behaviour itself results from the child’s unique evaluation of the risks and rewards present at that moment, along with her evaluation of her abilities and values. Because of this, the same child might act very differently in different situations. Thus, Mischel thought that specific behaviours were driven by the interaction between very specific, psychologically meaningful features of the situation in which people found themselves, the person’s unique way of perceiving that situation, and his or her abilities for dealing with it. Mischel and others argued that it was these social-cognitive processes that underlie people’s reactions to specific situations that provide some consistency when situational features are the same. If so, then studying these broad traits might be more fruitful than cataloging and measuring narrow, context-free traits like Extraversion or Neuroticism.

If so, then studying these broad traits might be more fruitful than cataloging and measuring narrow, context-free traits like Extraversion or Neuroticism.

In the years after the publication of Mischel’s (1968) book, debates raged about whether personality truly exists, and if so, how it should be studied. And, as is often the case, it turns out that a more moderate middle ground than what the situationists proposed could be reached. It is certainly true, as Mischel pointed out, that a person’s behaviour in one specific situation is not a good guide to how that person will behave in a very different specific situation. Someone who is extremely talkative at one specific party may sometimes be reticent to speak up during class and may even act like a wallflower at a different party. But this does not mean that personality does not exist, nor does it mean that people’s behaviour is completely determined by situational factors. Indeed, research conducted after the person-situation debate shows that on average, the effect of the “situation” is about as large as that of personality traits. However, it is also true that if psychologists assess a broad range of behaviours across many different situations, there are general tendencies that emerge. Personality traits give an indication about how people will act on average, but frequently they are not so good at predicting how a person will act in a specific situation at a certain moment in time. Thus, to best capture broad traits, one must assess aggregate behaviours, averaged over time and across many different types of situations. Most modern personality researchers agree that there is a place for broad personality traits and for the narrower units such as those studied by Walter Mischel.

However, it is also true that if psychologists assess a broad range of behaviours across many different situations, there are general tendencies that emerge. Personality traits give an indication about how people will act on average, but frequently they are not so good at predicting how a person will act in a specific situation at a certain moment in time. Thus, to best capture broad traits, one must assess aggregate behaviours, averaged over time and across many different types of situations. Most modern personality researchers agree that there is a place for broad personality traits and for the narrower units such as those studied by Walter Mischel.

(Donnellan, Oswald, Baird, & Lucas, 2006)

Instructions: Below are phrases describing people’s behaviours. Please use the rating scale below to describe how accurately each statement describes you. Describe yourself as you generally are now, not as you wish to be in the future. Describe yourself as you honestly see yourself, in relation to other people you know of the same sex as you are, and roughly your same age. Please read each statement carefully, and put a number from 1 to 5 next to it to describe how accurately the statement describes you.

Please read each statement carefully, and put a number from 1 to 5 next to it to describe how accurately the statement describes you.

1 = Very inaccurate

2 = Moderately inaccurate

3 = Neither inaccurate nor accurate

4 = Moderately accurate

5 = Very accurate

- _______ Am the life of the party (E)

- _______ Sympathize with others’ feelings (A)

- _______ Get chores done right away (C)

- _______ Have frequent mood swings (N)

- _______ Have a vivid imagination (O)

- _______Don’t talk a lot (E)

- _______ Am not interested in other people’s problems (A)

- _______ Often forget to put things back in their proper place (C)

- _______ Am relaxed most of the time (N)

- ______ Am not interested in abstract ideas (O)

- ______ Talk to a lot of different people at parties (E)

- ______ Feel others’ emotions (A)

- ______ Like order (C)

- ______ Get upset easily (N)

- ______ Have difficulty understanding abstract ideas (O)

- ______ Keep in the background (E)

- ______ Am not really interested in others (A)

- ______ Make a mess of things (C)

- ______ Seldom feel blue (N)

- ______ Do not have a good imagination (O)

Scoring: The first thing you must do is to reverse the items that are worded in the opposite direction. In order to do this, subtract the number you put for that item from 6. So if you put a 4, for instance, it will become a 2. Cross out the score you put when you took the scale, and put the new number in representing your score subtracted from the number 6.

In order to do this, subtract the number you put for that item from 6. So if you put a 4, for instance, it will become a 2. Cross out the score you put when you took the scale, and put the new number in representing your score subtracted from the number 6.

Items to be reversed in this way: 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20

Next, you need to add up the scores for each of the five OCEAN scales (including the reversed numbers where relevant). Each OCEAN score will be the sum of four items. Place the sum next to each scale below.

__________ Openness: Add items 5, 10, 15, 20

__________ Conscientiousness: Add items 3, 8, 13, 18

__________ Extraversion: Add items 1, 6, 11, 16

__________ Agreeableness: Add items 2, 7, 12, 17

__________ Neuroticism: Add items 4, 9,14, 19

Compare your scores to the norms below to see where you stand on each scale. If you are low on a trait, it means you are the opposite of the trait label. For example, low on Extraversion is Introversion, low on Openness is Conventional, and low on Agreeableness is Assertive.

19–20 Extremely High, 17–18 Very High, 14–16 High,

11–13 Neither high nor low; in the middle, 8–10 Low, 6–7 Very low, 4–5 Extremely low

Image Attributions

Figure 16.1: Nguyen Hung Vu, https://goo.gl/qKJUAC, CC BY 2.0, https://goo.gl/BRvSA7

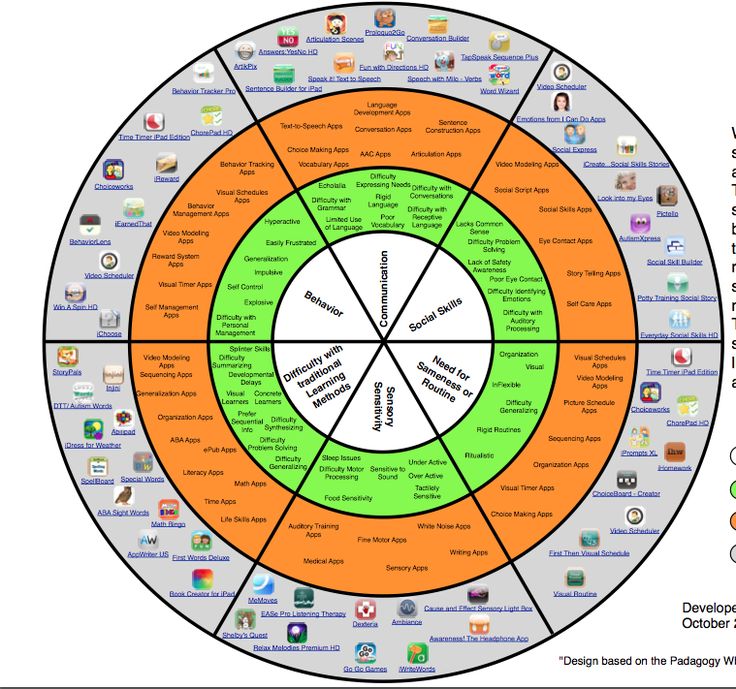

Figure 16.7: UO Education, https://goo.gl/ylgV9T, CC BY-NC 2.0, https://goo.gl/VnKlK8

References

Allport, G. W., & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait names: A psycholexical study. Psychological Monographs, 47, 211.

Ashton, M. C., & Lee, K. (2007). Empirical, theoretical, and practical advantages of the HEXACO model of personality structure. Personality and Social Psychological Review, 11, 150–166.

Caspi, A., Roberts, B. W., & Shiner, R. L. (2005). Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Reviews of Psychology, 56, 453–484.

Donnellan, M. B., Oswald, F. L., Baird, B. M., & Lucas, R. E. (2006). The mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment, 18, 192–203.

E. (2006). The mini-IPIP scales: Tiny-yet-effective measures of the Big Five factors of personality. Psychological Assessment, 18, 192–203.

Eysenck, H. J. (1981). A model for personality.New York: Springer Verlag.

Goldberg, L. R. (1990). An alternative description of personality: The Big Five personality traits. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 59, 1216–1229.

Gray, J. A. (1981). A critique of Eysenck’s theory of personality. In H. J. Eysenck (Ed.), A Model for Personality (pp. 246-276). New York: Springer Verlag.

Gray, J. A. & McNaughton, N. (2000). The neuropsychology of anxiety: An enquiry into the functions of the septo-hippocampal system (second edition).Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Matthews, G., Deary, I. J., & Whiteman, M. C. (2003). Personality traits. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the five-factor model of personality across instruments and observers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 81–90.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 81–90.

McCrae, R. R. & John, O. P. (1992). An introduction to the five-factor model and its applications. Journal of Personality, 60, 175–215.

Mischel, W. (1968). Personality and assessment. New York: John Wiley.

Paunonen, S. V., & Ashton, M. S. (2001). Big five factors and facets and the prediction of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81, 524–539.

Roberts, B. W., Kuncel, N. R., Shiner, R., Caspi, A., & Golberg, L. R. (2007). The power of personality: The comparative validity of personality traits, socioeconomic status, and cognitive ability for predicting important life outcomes. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 2, 313-345.

what are and how to evaluate them?

Features of behavior, communication, attitude to people, objects, work, things show the character traits that an individual possesses. According to their totality, an opinion about a person is determined. Such clichés as "the soul of the company", "bore", "pessimist", "cynic" are the result of an assessment of a person's character traits. Understanding how character is structured helps in building relationships. And this applies to both their own qualities and others.

Such clichés as "the soul of the company", "bore", "pessimist", "cynic" are the result of an assessment of a person's character traits. Understanding how character is structured helps in building relationships. And this applies to both their own qualities and others.

Classification of characters. nine0005

Character is defined by dominant traits, which in turn influence behavior and actions. They can be considered in the system of relations to work, other people, things, and oneself.

1. Labor

- Diligence-laziness . This “duet” can be both a character trait and express an attitude towards a particular work. A constant feeling of laziness can also indicate that a person is simply not interested in the business he is busy with, but in something else, he will prove himself better. Laziness can be a sign of insufficient motivation for life. But excessive diligence also takes on a degree of workaholism, which can also indicate problems in personal relationships, a lack of interests.

nine0014

nine0014 - Liability-irresponsibility . One of the most important qualities for an employee. A person who responsibly performs his duties, does not let his colleagues down, will be a valuable employee.

- Good faith-bad faith . Doing duty and doing it well are not the same thing. It is important for management that diligence is expressed not only in the mechanical performance of actions, but brings results.

- Initiative-passivity . This quality is especially valuable for people who want to move up the career ladder. If an employee does not show initiative, does not generate ideas, hides behind the backs of colleagues, he will not develop in his profession.

Take a personality test

2. Other people

- Closeness-sociability . It shows the openness of a person, his looseness, how easy it is for him to make acquaintances, how he feels in a new company, team.

nine0014

nine0014 - Truthfulness-Falsehood . Pathological liars lie even in trifles, hide the truth, easily betray. There are people who embellish reality, most often they do it because reality seems boring or not bright enough to them.

- Self-conformity . This quality shows how a person makes decisions. Whether he relies on his experience, knowledge, opinion, or follows someone's lead and it is easy to suppress him.

- Rudeness-politeness . Anger, inner feelings make a person cynical, rude. Such people are rude in queues, public transport, disrespectful to subordinates. Politeness, although it refers to positive character traits, can have a selfish background. It can also be an attempt to avoid confrontation.

3. Things

- Neatness-sloppiness . Creative mess or meticulous cleanliness in the house can show how neat a person is. You can also characterize it by its appearance.

Sloppy people often arouse antipathy, and there are not always those who want to see a broad soul behind external absurdity. nine0014

Sloppy people often arouse antipathy, and there are not always those who want to see a broad soul behind external absurdity. nine0014 - Thrift-negligence . You can evaluate a person by his attitude to the accumulated property, borrowed items. Although this trait of a person ended up in the material group, it can also manifest itself in relation to people.

- Greed-generosity . To be called generous, it is not necessary to be a philanthropist or give the last. At the same time, excessive generosity is sometimes a sign of irresponsibility or an attempt to "buy" someone else's favor. Greed is expressed not only in relation to other people, but also to oneself, when a person, out of fear of being left without money, saves even on trifles. nine0014

4. Self

- Demanding . When this personality trait is clearly expressed, two extremes appear. A person who is demanding of himself is often just as strict with others.

He lives by the principle "I could, so others can." He may be intolerant of other people's weaknesses, not realizing that each person is individual. The second extreme is built on uncertainty. A person tortures himself, considering himself insufficiently perfect. A striking example is anorexia, workaholism. nine0014

He lives by the principle "I could, so others can." He may be intolerant of other people's weaknesses, not realizing that each person is individual. The second extreme is built on uncertainty. A person tortures himself, considering himself insufficiently perfect. A striking example is anorexia, workaholism. nine0014 - Self-criticism . A person who knows how to criticize himself has a healthy self-esteem. Understanding, accepting and analyzing your achievements and defeats helps in the formation of a strong personality. When the balance is disturbed, either egocentrism or self-blame is observed.

- Modesty . It must be understood that modesty and shyness are different concepts. The first is based on the value system instilled during education. The second is a call to the development of complexes. In a normal state, modesty is manifested in moderation, calmness, knowledge of the measure in words, expression of emotions, financial spending, etc.

- Egoism and egocentrism . Similar concepts, but the feature here is egoism, but egocentrism is a way of thinking. Egoists think only of themselves, but use others for their own purposes. Egocentrics are often misanthropes and introverts who do not need others, who believe that no one is worthy of them.

- Self-esteem . Shows how a person feels internally. Outwardly, it is expressed in a high assessment of their rights and social value. nine0014

Take the test: introvert or extrovert?

Evaluation of personality and types of characters.

In addition to the main character traits that are formed in the system of relationships, psychologists also distinguish other areas:

- Intellectual. Resourcefulness, curiosity, frivolity, practicality.

- Emotional. Passion, sentimentality, impressionability, irascibility, cheerfulness.

- Strong-willed.

Courage, perseverance, purposefulness. nine0014

Courage, perseverance, purposefulness. nine0014 - Moral. Justice, responsiveness, kindness.

There are motivational traits-goals that drive a personality and determine its guidelines. As well as instrumental traits-methods, they show exactly what methods the desired will be achieved. So, for example, a girl can manifest masculine qualities of character when she persistently and proactively seeks her lover.

About what are the traits of character, put forward the theory of Gordon Allport. The psychologist divided them into the following types:

- Dominant . They determine the behavior of the individual as a whole, regardless of the sphere, and at the same time influence other qualities or even overlap them. For example, kindness or greed.

- Ordinary . They are also expressed in all spheres of life. These include, for example, humanity.

- Minor .

They do not particularly affect anything, often stemming from other traits. For example, diligence.

They do not particularly affect anything, often stemming from other traits. For example, diligence.

There are typical and individual personality traits. Typical ones are easy to group, noticing one of the dominant qualities or a few minor ones, you can “draw” a personal portrait as a whole, determine the type of character. This helps to predict actions, better understand a person. So, for example, if an individual has responsiveness, then most likely he will come to the rescue in a difficult situation, support, listen. nine0003

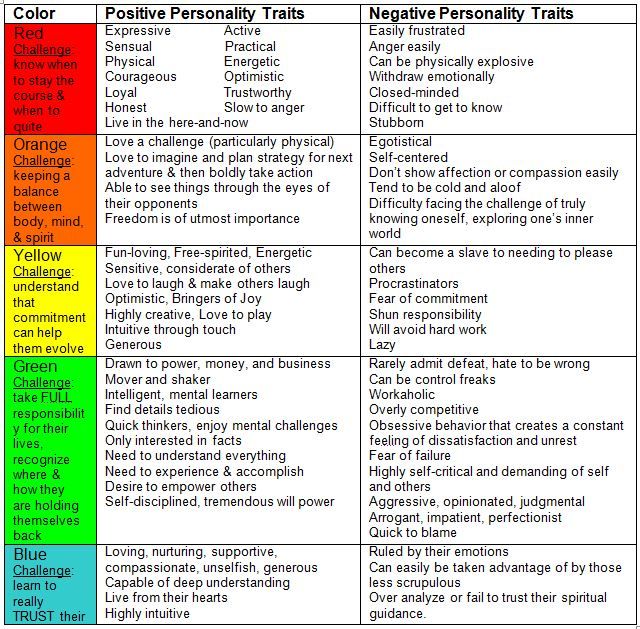

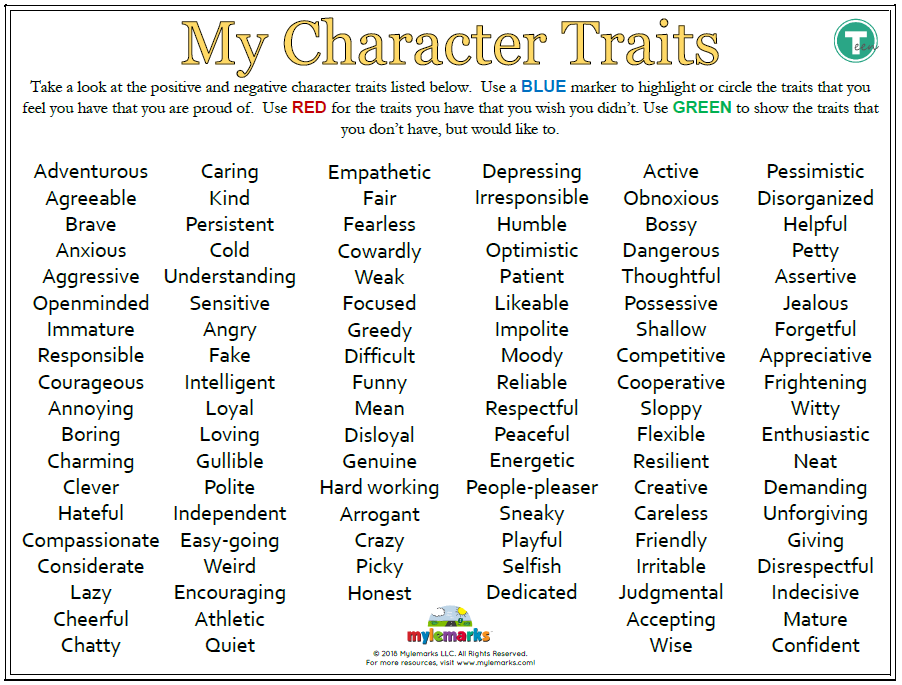

Positive and negative character traits.

Personality is a balance of positive and negative qualities. In this regard, everything is conditional. For example, envy is considered a bad quality, but some psychologists argue that it can become an incentive to work on yourself or improve your life. The distortion of positive traits, on the contrary, can lead to their transformation into negative qualities. Persistence develops into obsession, initiative into self-centeredness. nine0003

nine0003

Strong and weak character traits should be highlighted, they often have to be remembered when filling out a resume. They terrify many, because it can be difficult to evaluate oneself. Here, a small "cheat sheet":

- Weak. Formality, irritability, shyness, impulsiveness, inability to remain silent or say no.

- Strong. Perseverance, sociability, patience, punctuality, organization, determination.

- Negative. nine0013 Pride, jealousy, vindictiveness, cruelty, parasitism.

- Positive. Kindness, sincerity, optimism, openness, peacefulness.

Character traits are formed in childhood, but at the same time they can change, transform depending on life circumstances. It's never too late to change what you don't like about yourself.

Take a Personality Test

Scientists: These Six Personality Traits Make Success in Life

- David Robson

- BBC Future

Sign up for our 'Context' newsletter to help you understand what's going on.

Image copyright Getty Images

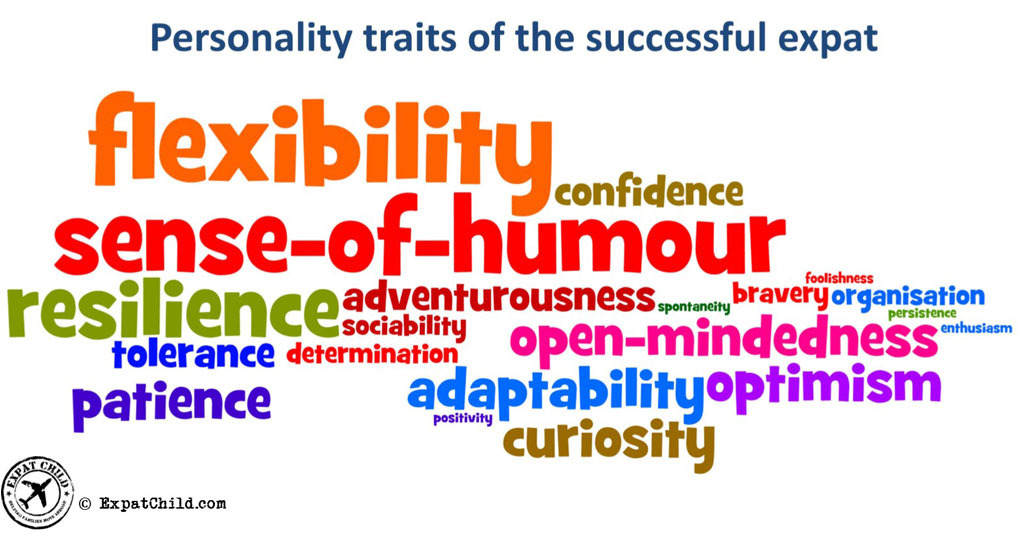

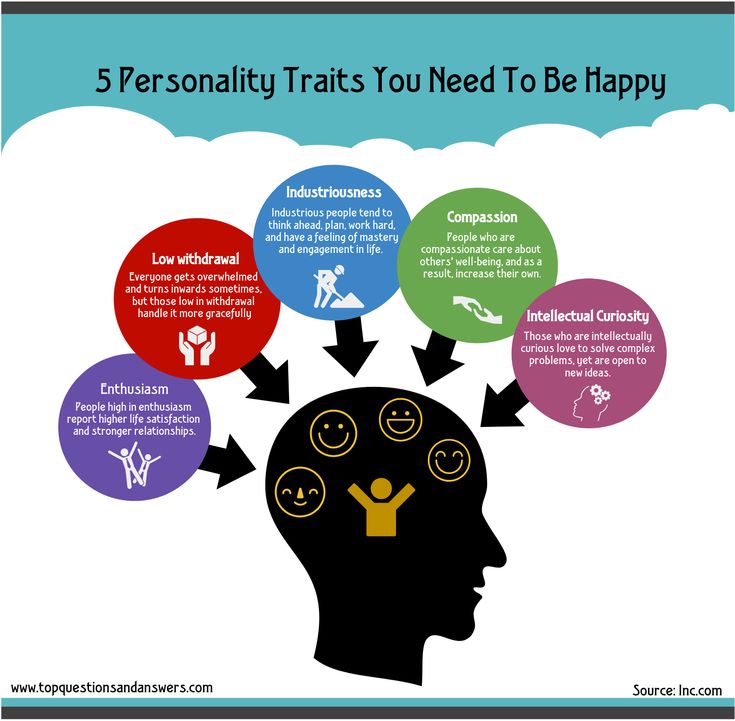

These qualities help you reach your potential and achieve success in life. But scientists warn that if you overdo it, any of these qualities begins to work against you.

Are you curious, conscientious and not averse to competing? Or maybe you have such more vague qualities as "high degree of adaptability", "ability to accept uncertainty" or "risk-based approach"? nine0003

If so, congratulations! According to a new study by psychologists, these six character traits make up a person with high potential. This potential will help you get very far in life.

In reality, of course, everything is somewhat more complicated, with certain nuances. It turns out that those same traits, if exaggerated, can get in your way, and the key to success is knowing how to make the most of your strengths and prevent them from turning into weaknesses. nine0003

Nevertheless, the results of the new study allow us to take an important step forward in understanding the complex process of personal influence on career.

- 14 new Russian billionaires - who are they?

- Your career - are you willing to risk for it?

- Career through the bed: how much is the norm in Hollywood?

- Habits and mistakes that can ruin your career

Attempts to calculate our personality in the workplace have been made many times and with varying success. One of the most popular tests today is based on the Myers-Briggs typology, which identifies a person according to the style of thinking - for example, introverts / extroverts. nine0003

Nine out of ten US companies currently use the Myers-Briggs test to classify their employees. Alas, many academic psychologists are very critical of this typology, pointing out its outdatedness and inconsistency with current approaches to job evaluation.

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.:strip_icc()/pic4720254.jpg) nine0003

nine0003

episodes

The End of the Story Podcast

One study found that these tests are not the best way to predict an employee's future success as a manager. And some critics of the system generally call it pseudoscientific.

"At the initial stage of learning about the capabilities of the personnel, this [Myers-Briggs test] can be a useful tool. But if you are using it to predict future performance on a large scale, or trying to calculate the most effective candidates with it, Myers-Briggs is nothing to you won't," says Ian McRae, a psychologist and co-author of High Potential. nine0003

Concluding that recent discoveries in psychological research would help them much more, McRae and Adrian Furnham of University College London identified six personality traits that are consistently associated with successful careers. They combined them with the High Potential Trait Inventory test.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Image caption,Curiosity can help you learn new things more easily, improve your overall job satisfaction, and prevent burnout

McRae notes that each such character trait has its drawbacks, which manifest themselves when it is used excessively, which means that there is a certain optimal level.

The scientist also emphasizes that the relative importance of one character trait or another will be determined by the work you do, so that success in, say, a technical position will require slightly different attitudes than in one that involves communicating with customers.

The version of the test that was shown to me was designed to calculate future leaders. For such people, in order to make a successful career, it is important to have the following six character traits:

1. Conscientiousness

Conscientious people are responsible for the plans and try to fulfill them thoroughly. They are good at suppressing random impulses and try to make wise decisions from a long-term perspective.

Following on from IQ, conscientiousness is often seen as one of the main indicators of future success in life - for example, academic success. High integrity in the workplace is an essential element for successful strategic planning, but if you go overboard with it, it makes you too stiff and inflexible. nine0003

nine0003

2. Adjustability

We all experience anxiety from time to time, but people with a high degree of adaptability deal with anxiety and work stress more easily, without letting feelings influence behavior and decisions.

Those who score low on the adaptability scale perform worse under pressure, but the effect can be mitigated with the right attitude.

Various studies show that looking at a stressful situation differently, not as a threat to well-being, but as a potential source of growth, helps. Then people get out of difficult, even the most negative situations faster and more productively. nine0003

3. Acceptance of uncertainty

Are you the type of person who prefers all tasks to be clearly defined and their outcome easily predictable? Or do you enjoy the unknown?

Those with a heightened tolerance for uncertainty may take into account and consider many different points of view before making a decision. This means that they are less dogmatic and more flexible in their opinions. nine0003

This means that they are less dogmatic and more flexible in their opinions. nine0003

"Uncertainty intolerance can be seen as a dictatorial trait," McRae says. “Such people try to reduce a difficult situation to one simple commercial argument, which can be considered a typical feature of destructive leadership.”

technologies or economic climate change - and deal with complex, multifaceted challenges.

"We try to identify the ability of leaders to listen to many different points of view, take complex arguments and learn from them constructively instead of simplifying everything," McRae adds. "And we found that the higher the position you hold, the more important this trait is to make decisions."

If a person feels uncomfortable in an environment of uncertainty, this is not always a bad thing. In some areas - for example, in the field of control and regulation - a more structured approach is more useful. nine0003

Understanding where you are on the accepting uncertainty spectrum will help you feel more confident in the workplace.

4. Curiosity

Compared to other traits and properties of character, curiosity often fell out of the field of view of psychologists. However, a recent study shows that an innate interest in new ideas has many benefits.

This trait seems to mean that you are more creative at work and more flexible in how you solve problems. Curiosity helps you learn new things more easily, increases job satisfaction, and protects against burnout. nine0003

However, if a person is too curious, this can lead to the fact that he will flutter like a butterfly from project to project, without fully understanding any of them.

5. Risk-Based Approach (or Courage)

Do you try to avoid a potentially unpleasant confrontation? Or do you boldly move forward, believing that by quickly passing through an unpleasant situation, you will find a long-term gain in business?

It is clear that the ability to cope with difficult situations is the most important thing for any leader. As a manager, you must make decisions that lead to a positive outcome, even if you have to overcome resistance to do so. nine0003

As a manager, you must make decisions that lead to a positive outcome, even if you have to overcome resistance to do so. nine0003

6. Competitiveness

There is a rather thin line between striving for personal success and unhealthy jealousy for other people's success.

At its best, competitiveness can be a powerful motivator for extra effort. At worst, it can lead to a split within the team.

How to predict the future salary?

Together, these six qualities bring together the modern understanding of how various character traits influence success at work, especially for those who aspire to a career in leadership. nine0003

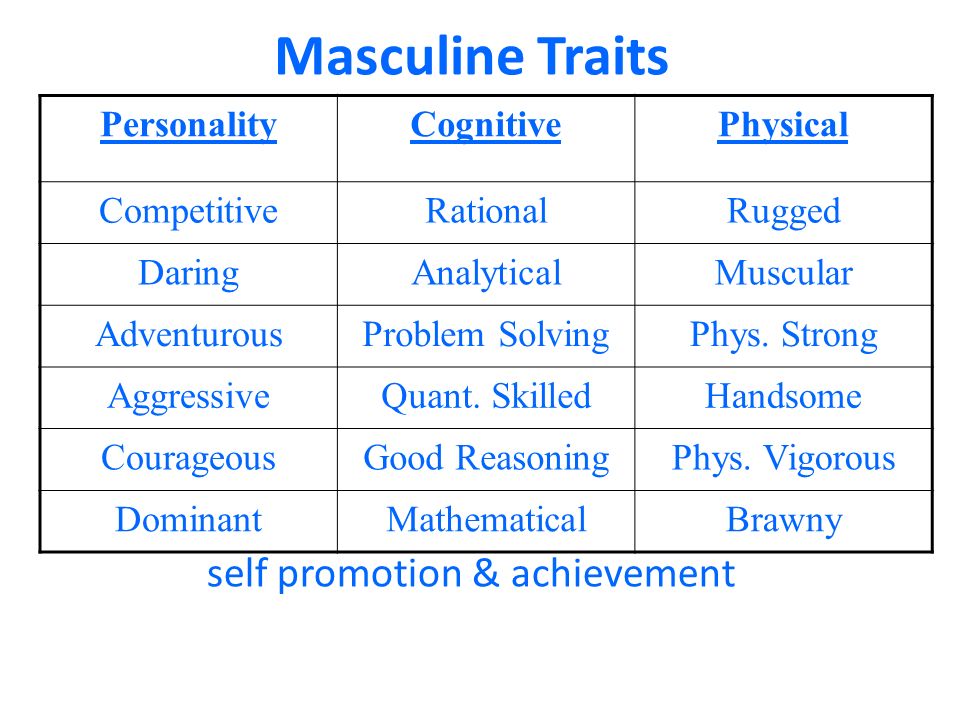

Also of interest are those character traits that McRae and Furnham did not include in their system.

The Extraversion-Introversion Scale, for example, can determine how we deal with certain social situations, but it seems to have little effect on the overall quality of our work. Also, until we understand how accommodating, our ability to get along with different people, will help us predict future professional success.

Also, until we understand how accommodating, our ability to get along with different people, will help us predict future professional success.

- A promotion that makes you want to quit

- Became a boss for the first time? Beware of these mistakes!

- The Queen Bee Syndrome: Why Bosses Stop Women from Making Careers

In order to determine the presence of one or another of the above six qualities using the High Potential Trait Inventory (HPTI) test, test-takers must assess the extent to which they agree or disagree with a series of statements , such as: "It annoys me when I do not know exactly what is expected of me at work" (this measures the degree of acceptance of uncertainty) or "My personal goals are higher than that of the organization in which I work" (this is how conscientiousness is measured ). nine0003

McRae has already begun testing the reliability of the HPTI (High Potential Personality Traits) - for example, by tracking the careers of multinational business leaders over the past few years.

McRae and Furnham's research is still ongoing, but interim results published last year show that the presence of these six qualities can predict both subjective and objective success.

In one case, the responses of test-takers explained about 25% of the cases of differences in income - which, in general, is a rather large percentage of correlation (say, comparable to the influence of intelligence). nine0003

Competitiveness and acceptance of uncertainty were the top predictors of future wages, while conscientiousness was the best predictor of subjective satisfaction.

Balanced team, balanced boss

The researchers also tested the relationship of these personality traits and IQ (another major predictor of career success) and found that their impact on the future overlaps to a small degree. nine0003

The HPTI is used as part of recruitment, but McRae says it can help with personal development as well, as you identify your own strengths and weaknesses (and what it can do for you).