Chronic panic attacks

Panic attacks and panic disorder - Symptoms and causes

Overview

A panic attack is a sudden episode of intense fear that triggers severe physical reactions when there is no real danger or apparent cause. Panic attacks can be very frightening. When panic attacks occur, you might think you're losing control, having a heart attack or even dying.

Many people have just one or two panic attacks in their lifetimes, and the problem goes away, perhaps when a stressful situation ends. But if you've had recurrent, unexpected panic attacks and spent long periods in constant fear of another attack, you may have a condition called panic disorder.

Although panic attacks themselves aren't life-threatening, they can be frightening and significantly affect your quality of life. But treatment can be very effective.

Products & Services

- Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Symptoms

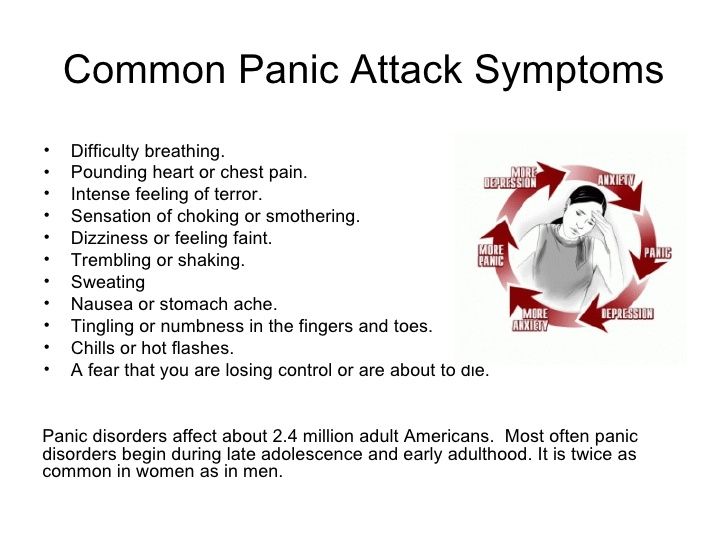

Panic attacks typically begin suddenly, without warning. They can strike at any time — when you're driving a car, at the mall, sound asleep or in the middle of a business meeting. You may have occasional panic attacks, or they may occur frequently.

Panic attacks have many variations, but symptoms usually peak within minutes. You may feel fatigued and worn out after a panic attack subsides.

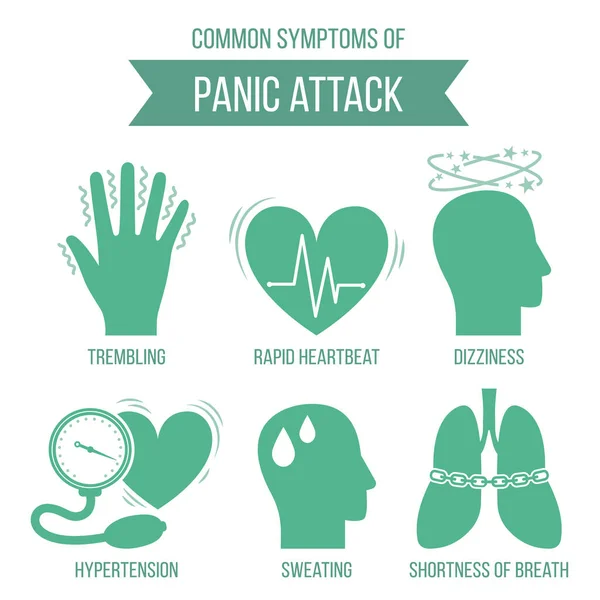

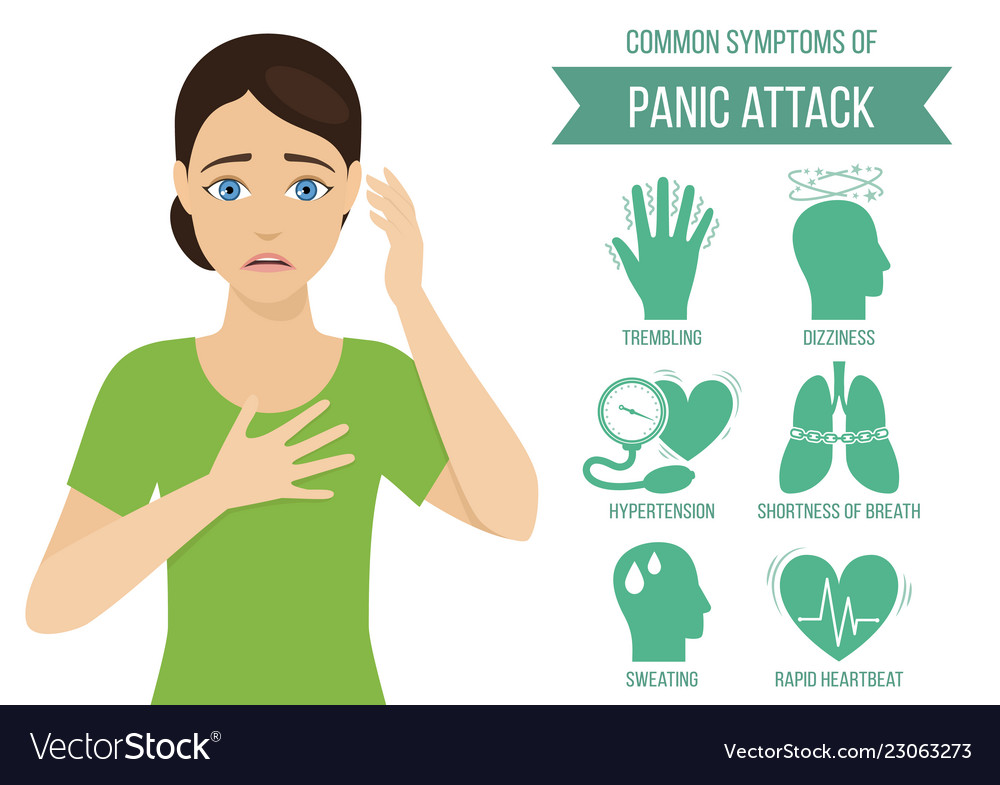

Panic attacks typically include some of these signs or symptoms:

- Sense of impending doom or danger

- Fear of loss of control or death

- Rapid, pounding heart rate

- Sweating

- Trembling or shaking

- Shortness of breath or tightness in your throat

- Chills

- Hot flashes

- Nausea

- Abdominal cramping

- Chest pain

- Headache

- Dizziness, lightheadedness or faintness

- Numbness or tingling sensation

- Feeling of unreality or detachment

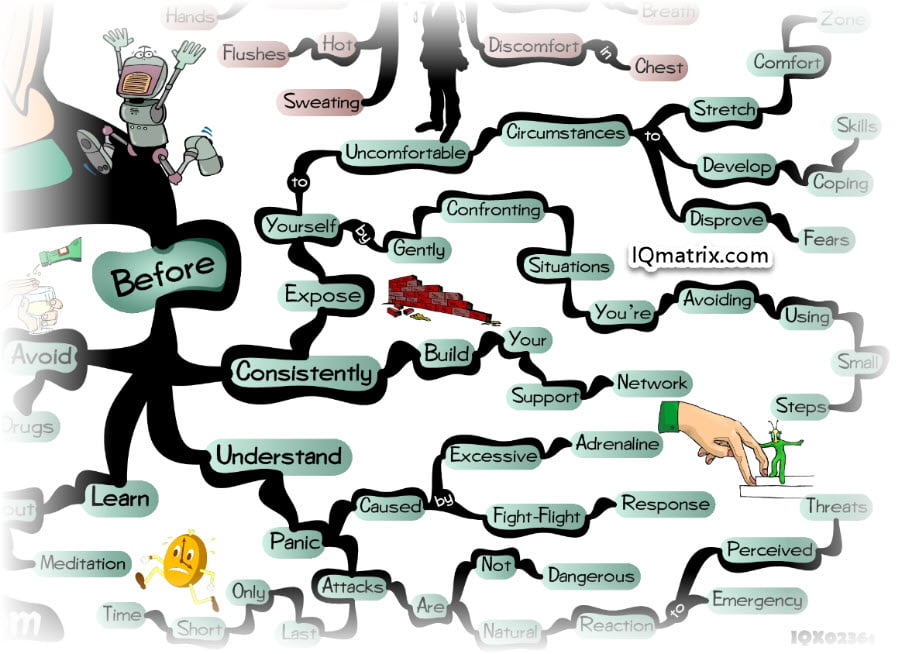

One of the worst things about panic attacks is the intense fear that you'll have another one. You may fear having panic attacks so much that you avoid certain situations where they may occur.

You may fear having panic attacks so much that you avoid certain situations where they may occur.

When to see a doctor

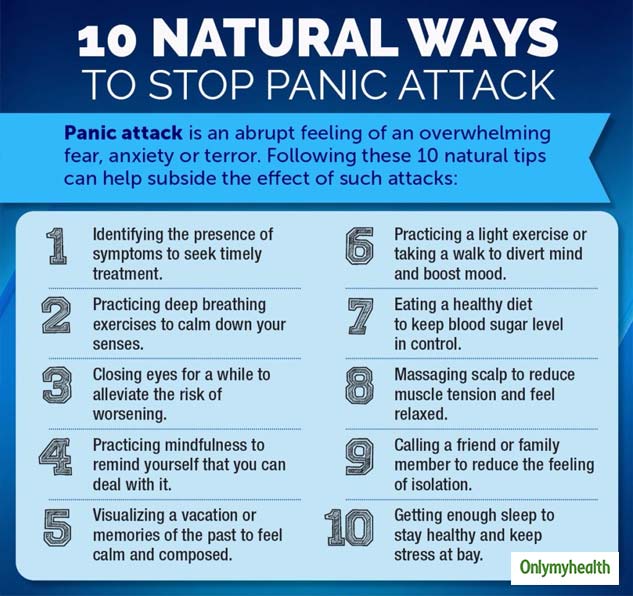

If you have panic attack symptoms, seek medical help as soon as possible. Panic attacks, while intensely uncomfortable, are not dangerous. But panic attacks are hard to manage on your own, and they may get worse without treatment.

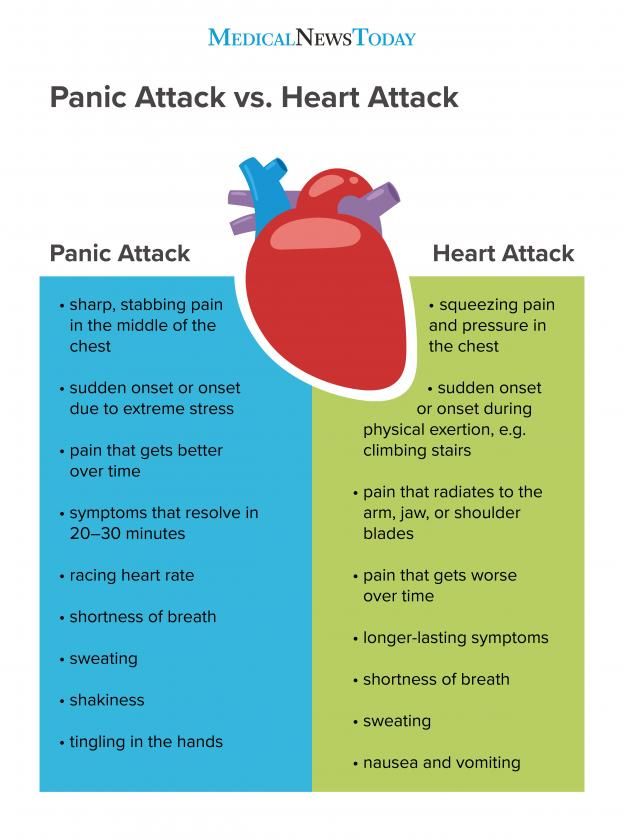

Panic attack symptoms can also resemble symptoms of other serious health problems, such as a heart attack, so it's important to get evaluated by your primary care provider if you aren't sure what's causing your symptoms.

Request an appointment

From Mayo Clinic to your inbox

Sign up for free, and stay up to date on research advancements, health tips and current health topics, like COVID-19, plus expertise on managing health. Click here for an email preview.

To provide you with the most relevant and helpful information, and understand which information is beneficial, we may combine your email and website usage information with other information we have about you. If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

If you are a Mayo Clinic patient, this could include protected health information. If we combine this information with your protected health information, we will treat all of that information as protected health information and will only use or disclose that information as set forth in our notice of privacy practices. You may opt-out of email communications at any time by clicking on the unsubscribe link in the e-mail.

Causes

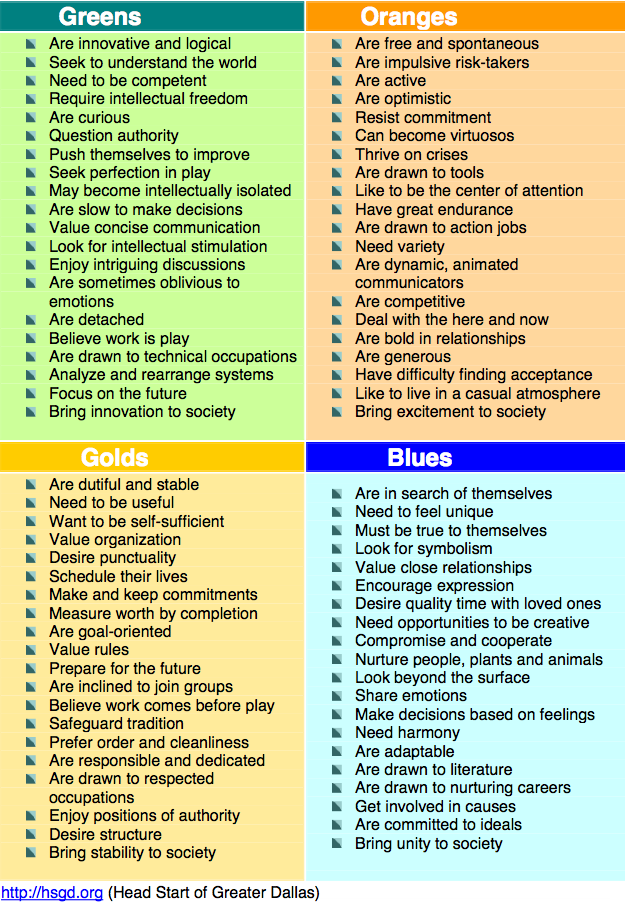

It's not known what causes panic attacks or panic disorder, but these factors may play a role:

- Genetics

- Major stress

- Temperament that is more sensitive to stress or prone to negative emotions

- Certain changes in the way parts of your brain function

Panic attacks may come on suddenly and without warning at first, but over time, they're usually triggered by certain situations.

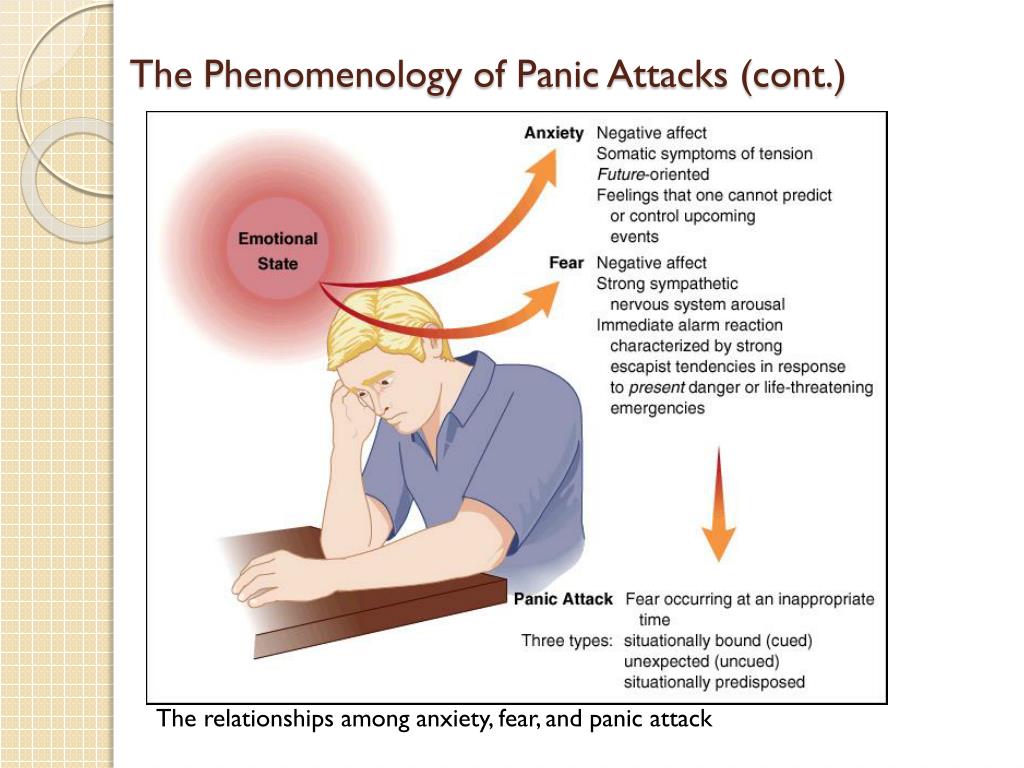

Some research suggests that your body's natural fight-or-flight response to danger is involved in panic attacks. For example, if a grizzly bear came after you, your body would react instinctively. Your heart rate and breathing would speed up as your body prepared for a life-threatening situation. Many of the same reactions occur in a panic attack. But it's unknown why a panic attack occurs when there's no obvious danger present.

More Information

- Nocturnal panic attacks: What causes them?

Risk factors

Symptoms of panic disorder often start in the late teens or early adulthood and affect more women than men.

Factors that may increase the risk of developing panic attacks or panic disorder include:

- Family history of panic attacks or panic disorder

- Major life stress, such as the death or serious illness of a loved one

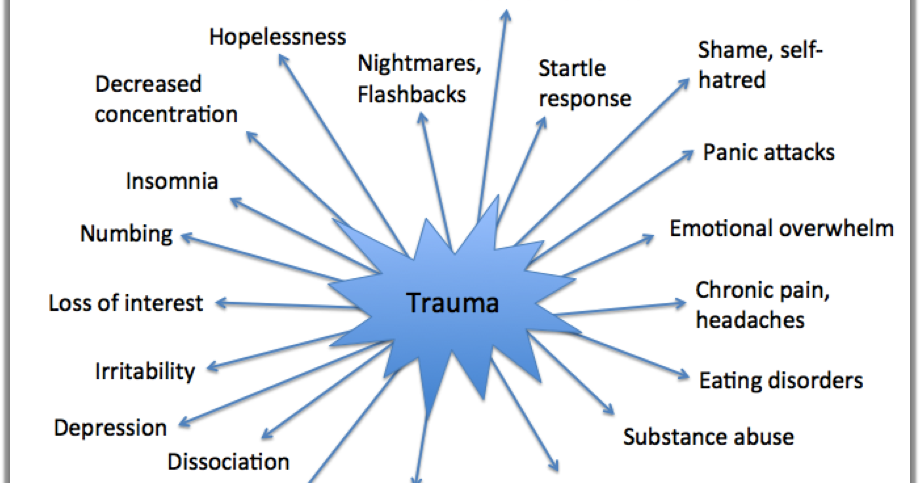

- A traumatic event, such as sexual assault or a serious accident

- Major changes in your life, such as a divorce or the addition of a baby

- Smoking or excessive caffeine intake

- History of childhood physical or sexual abuse

Complications

Left untreated, panic attacks and panic disorder can affect almost every area of your life. You may be so afraid of having more panic attacks that you live in a constant state of fear, ruining your quality of life.

You may be so afraid of having more panic attacks that you live in a constant state of fear, ruining your quality of life.

Complications that panic attacks may cause or be linked to include:

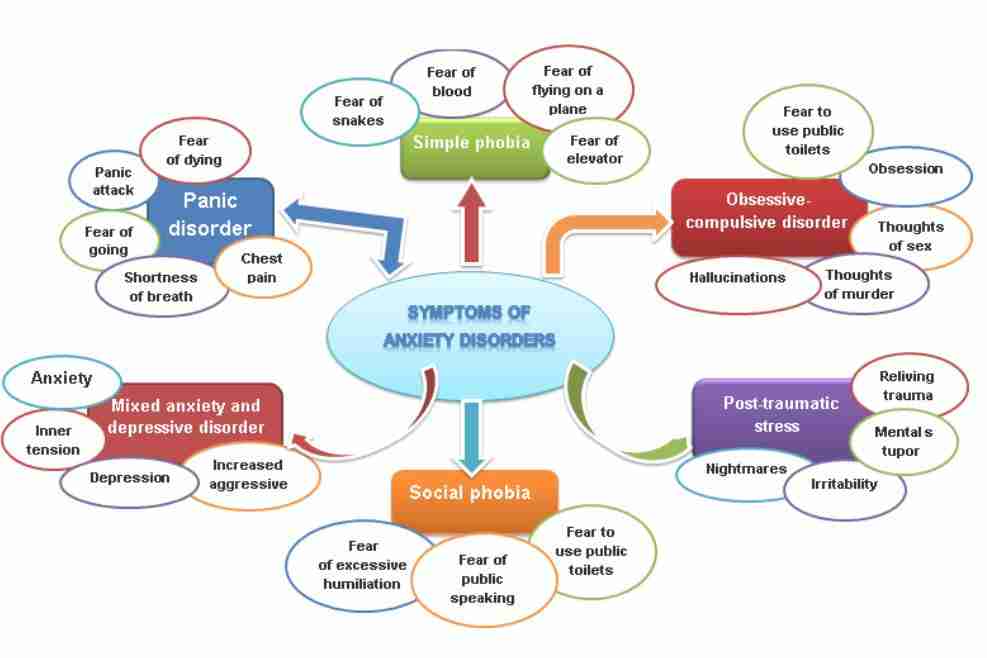

- Development of specific phobias, such as fear of driving or leaving your home

- Frequent medical care for health concerns and other medical conditions

- Avoidance of social situations

- Problems at work or school

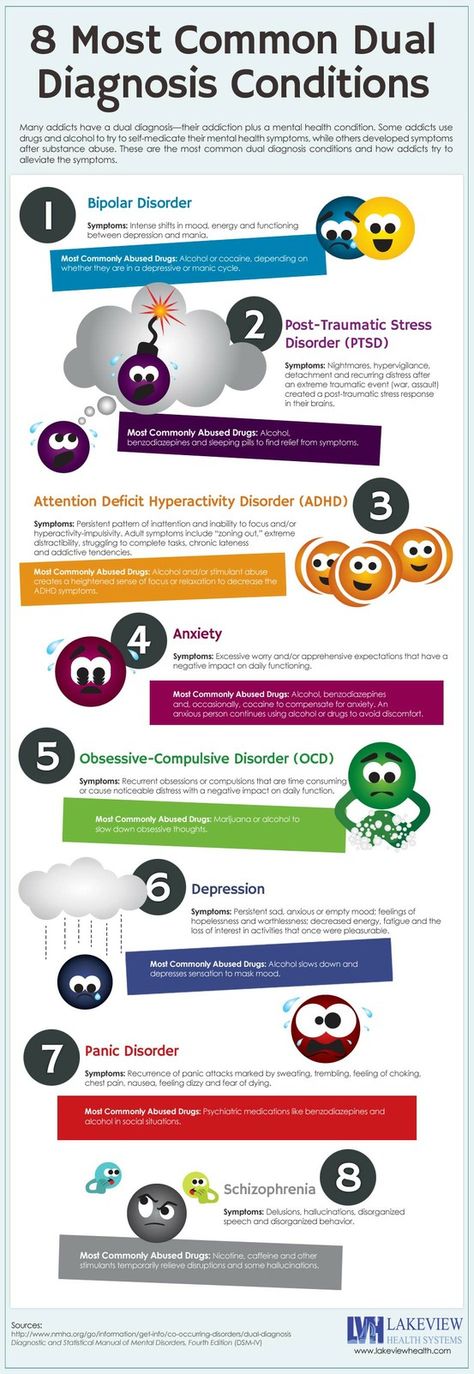

- Depression, anxiety disorders and other psychiatric disorders

- Increased risk of suicide or suicidal thoughts

- Alcohol or other substance misuse

- Financial problems

For some people, panic disorder may include agoraphobia — avoiding places or situations that cause you anxiety because you fear being unable to escape or get help if you have a panic attack. Or you may become reliant on others to be with you in order to leave your home.

Prevention

There's no sure way to prevent panic attacks or panic disorder. However, these recommendations may help.

However, these recommendations may help.

- Get treatment for panic attacks as soon as possible to help stop them from getting worse or becoming more frequent.

- Stick with your treatment plan to help prevent relapses or worsening of panic attack symptoms.

- Get regular physical activity, which may play a role in protecting against anxiety.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Related

Associated Procedures

Products & Services

NIMH » Panic Disorder: When Fear Overwhelms

Do you sometimes have sudden attacks of anxiety and overwhelming fear that last for several minutes? Maybe your heart pounds, you sweat, and you feel like you can’t breathe or think clearly. Do these attacks occur at unpredictable times with no apparent trigger, causing you to worry about the possibility of having another one at any time?

An untreated panic disorder can affect your quality of life and lead to difficulties at work or school. The good news is panic disorder is treatable. Learn more about the symptoms of panic disorder and how to find help.

The good news is panic disorder is treatable. Learn more about the symptoms of panic disorder and how to find help.

What is panic disorder?

People with panic disorder have frequent and unexpected panic attacks. These attacks are characterized by a sudden wave of fear or discomfort or a sense of losing control even when there is no clear danger or trigger. Not everyone who experiences a panic attack will develop panic disorder.

Panic attacks often include physical symptoms that might feel like a heart attack, such as trembling, tingling, or rapid heart rate. Panic attacks can occur at any time. Many people with panic disorder worry about the possibility of having another attack and may significantly change their life to avoid having another attack. Panic attacks can occur as frequently as several times a day or as rarely as a few times a year.

Panic disorder often begins in the late teens or early adulthood. Women are more likely than men to develop panic disorder.

What are the signs and symptoms of panic disorder?

People with panic disorder may have:

- Sudden and repeated panic attacks of overwhelming anxiety and fear

- A feeling of being out of control, or a fear of death or impending doom during a panic attack

- An intense worry about when the next panic attack will happen

- A fear or avoidance of places where panic attacks have occurred in the past

- Physical symptoms during a panic attack, such as:

- Pounding or racing heart

- Sweating

- Chills

- Trembling

- Difficulty breathing

- Weakness or dizziness

- Tingly or numb hands

- Chest pain

- Stomach pain or nausea

What causes panic disorder?

Panic disorder sometimes runs in families, but no one knows for sure why some family members have it while others don’t. Researchers have found that several parts of the brain and certain biological processes may play a crucial role in fear and anxiety. Some researchers think panic attacks are like “false alarms” where our body’s typical survival instincts are active either too often, too strongly, or some combination of the two. For example, someone with panic disorder might feel their heart pounding and assume they’re having a heart attack. This may lead to a vicious cycle, causing a person to experience panic attacks seemingly out of the blue, the central feature of panic disorder. Researchers are studying how the brain and body interact in people with panic disorder to create more specialized treatments. In addition, researchers are looking at the ways stress and environmental factors play a role in the disorder.

Some researchers think panic attacks are like “false alarms” where our body’s typical survival instincts are active either too often, too strongly, or some combination of the two. For example, someone with panic disorder might feel their heart pounding and assume they’re having a heart attack. This may lead to a vicious cycle, causing a person to experience panic attacks seemingly out of the blue, the central feature of panic disorder. Researchers are studying how the brain and body interact in people with panic disorder to create more specialized treatments. In addition, researchers are looking at the ways stress and environmental factors play a role in the disorder.

How is panic disorder treated?

If you’re experiencing symptoms of panic disorder, talk to a health care provider. After discussing your history, a health care provider may conduct a physical exam to ensure that an unrelated physical problem is not causing your symptoms. A health care provider may refer you to a mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist, psychologist, or clinical social worker. The first step to effective treatment is to get a diagnosis, usually from a mental health professional.

The first step to effective treatment is to get a diagnosis, usually from a mental health professional.

Panic disorder is generally treated with psychotherapy (sometimes called “talk therapy”), medication, or both. Speak with a health care provider about the best treatment for you.

Psychotherapy

Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), a research-supported type of psychotherapy, is commonly used to treat panic disorder. CBT teaches you different ways of thinking, behaving, and reacting to the feelings that happen during or before a panic attack. The attacks can become less frequent once you learn to react differently to the physical sensations of anxiety and fear during a panic attack.

Exposure therapy is a common CBT method that focuses on confronting the fears and beliefs associated with panic disorder to help you engage in activities you have been avoiding. Exposure therapy is sometimes used along with relaxation exercises.

For more information on psychotherapy, visit the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) psychotherapies webpage.

Medication

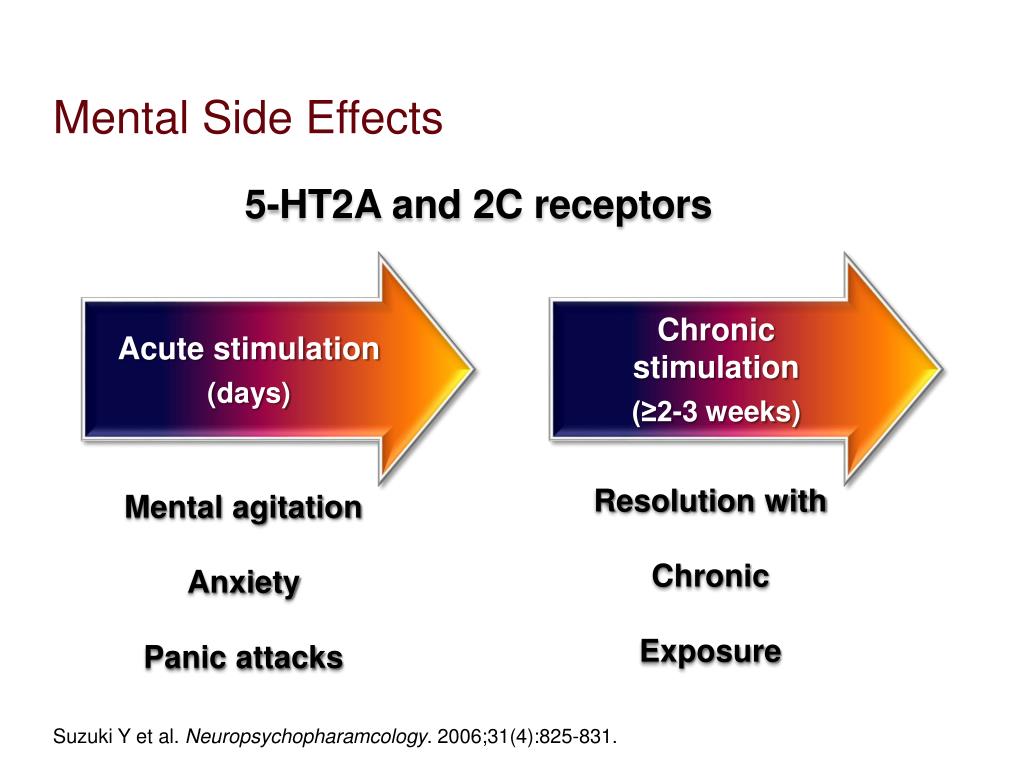

Health care providers may prescribe medication to treat panic disorder. Different types of medication can be effective, including:

- Antidepressants, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs)

- Beta-blockers

- Anti-anxiety medications, such as benzodiazepines

SSRI and SNRI antidepressants are commonly used to treat depression, but they also can help treat the symptoms of panic disorder. They may take several weeks to start working. These medications also may cause side effects, such as headaches, nausea, or difficulty sleeping. These side effects are usually not severe, especially if the dose starts off low and is increased slowly over time. Talk to your health care provider about any side effects that you may experience.

Beta-blockers can help control some of the physical symptoms of panic disorder, such as rapid heart rate, sweating, and tremors. Although health care providers do not commonly prescribe beta-blockers for panic disorder, the medication may be helpful in certain situations that precede a panic attack.

Although health care providers do not commonly prescribe beta-blockers for panic disorder, the medication may be helpful in certain situations that precede a panic attack.

Benzodiazepines, which are anti-anxiety sedative medications, can be very effective in rapidly decreasing panic attack symptoms. However, some people build up a tolerance to these medications and need higher and higher doses to get the same effect. Some people even become dependent on them. Therefore, a health care provider may prescribe them only for brief periods of time if you need them.

Both psychotherapy and medication can take some time to work. Many people try more than one medication before finding the best one for them. A health care provider can work with you to find the best medication, dose, and duration of treatment for you. A healthy lifestyle also can help combat panic disorder. Make sure to get enough sleep and exercise, eat a healthy diet, and turn to family and friends who you trust for support. To learn more ways to take care of your mental health, visit NIMH’s Caring for Your Mental Health webpage.

To learn more ways to take care of your mental health, visit NIMH’s Caring for Your Mental Health webpage.

For more information about medications used to treat panic disorder, visit NIMH’s Mental Health Medications webpage. Visit the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) website for the latest warnings, patient medication guides, and information on newly approved medications.

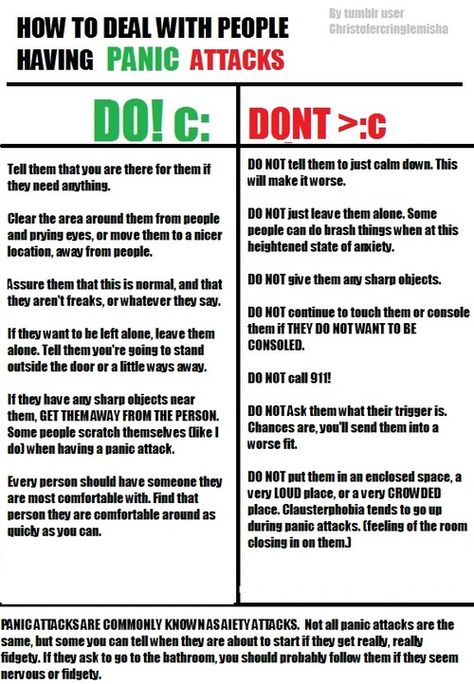

How can I support myself and others with panic disorder?

Educate Yourself

A good way to help yourself or a loved one who may be struggling with panic attacks or panic disorder is to seek information. Research the warning signs, learn about treatment options, and keep up to date with current research.

Communicate

If you are experiencing panic disorder symptoms, have an honest conversation about how you’re feeling with someone you trust. If you think that a friend or family member may be struggling with panic disorder, set aside a time to talk with them to express your concern and reassure them of your support.

Know When to Seek Help

If your anxiety, or the anxiety of a loved one, starts to cause problems in everyday life—such as at school, at work, or with friends and family—it’s time to seek professional help. Talk to a health care provider about your mental health.

Are there clinical trials studying panic disorder?

NIMH supports a wide range of research, including clinical trials that look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions—including panic disorder. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge so that others may be better helped in the future.

Researchers at NIMH and around the country conduct clinical trials with patients and healthy volunteers. Talk to a health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you. For more information, visit NIMH's clinical trials webpage.

For more information, visit NIMH's clinical trials webpage.

Finding Help

Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator

This online resource, provided by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), helps you locate mental health treatment facilities and programs. Find a facility in your state by searching SAMHSA’s online Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator. For additional resources, visit NIMH's Help for Mental Illnesses webpage.

Talking to a Health Care Provider About Your Mental Health

Communicating well with a health care provider can improve your care and help you both make good choices about your health. Find tips to help prepare for and get the most out of your visit at Taking Control of Your Mental Health: Tips for Talking With Your Health Care Provider. For additional resources, including questions to ask a provider, visit the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality website.

If you or someone you know is in immediate distress or is thinking about hurting themselves, call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline toll-free at 1-800-273-TALK (8255). You also can text the Crisis Text Line (HELLO to 741741) or use the Lifeline Chat on the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline website.

Reprints

This publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission from NIMH. We encourage you to reproduce and use NIMH publications in your efforts to improve public health. If you do use our materials, we request that you cite the National Institute of Mental Health. To learn more about using NIMH publications, please contact the NIMH Information Resource Center at 1-866‑615‑6464, email [email protected], or refer to NIMH’s reprint guidelines.

For More Information

MedlinePlus (National Library of Medicine) (en español)

ClinicalTrials. gov (en español)

gov (en español)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

National Institutes of Health

NIH Publication No. 22-MH-8077

Revised 2022

A Brief History of Panic Attacks - T&P

Alpina Non-Fiction has published The Age of Anxiety: Fears, Hopes, Neuroses, and the Quest for Peace of Mind about stress as a hallmark of the era. The book is based on the mistakes and achievements of biochemistry and neuroscience, genetics and psychopharmacology, psychotherapy and psychiatry, as well as the personal experience of its author Scott Stossel, an American journalist and editor-in-chief of The Atlantic magazine. T&P publish excerpts from the chapter "A Brief History of Panic, or How Drugs Created a New Disorder" - a fascinating story about how the expression "panic attack" appeared, and the main problem of tranquilizers.

An anxiety attack may consist of a single feeling of anxiety, without images associated with it, or it may be accompanied by the first conjecture that comes up - about the end of the world, about a heart attack, about insanity. The feeling of anxiety can be combined with a disturbance in one or more somatic functions - respiration, heartbeat, vasomotor innervation, or glandular activity. From this combination, the patient snatches out one factor, then another. He complains of "cramps in the heart," "stops in breathing," "flushes of sweat," and so on."

The feeling of anxiety can be combined with a disturbance in one or more somatic functions - respiration, heartbeat, vasomotor innervation, or glandular activity. From this combination, the patient snatches out one factor, then another. He complains of "cramps in the heart," "stops in breathing," "flushes of sweat," and so on."

On the legitimacy of isolating a symptom complex from neurasthenia called "anxiety neurosis" (1895) Sigmund Freud.

"The Age of Anxiety: Fears, Hopes, Neuroses, and the Search for Peace of Mind"

One day I'm sitting in my office, reading the mail - and I note out of the corner of my consciousness that I'm a bit hot. "Is it hot in the room?" The bodily sensation suddenly shifts from the periphery to the center of attention. "I have a temperature? I am getting ill? Lose consciousness? Will I throw up? Will I lose my strength, not having time to escape or call for help? I am writing a book about anxiety. I have studied panic as a phenomenon far and wide. For a non-specialist, I have a decent grasp of the neuromechanics of a panic attack. I had thousands of them. It would seem that knowledge and experience should help in such cases. Sometimes they really help. If the symptoms are recognized at the very beginning, from time to time it is possible to stop the attack or at least reduce it to the so-called mild panic attack. However, more often than not, my internal dialogue looks something like this:0007

For a non-specialist, I have a decent grasp of the neuromechanics of a panic attack. I had thousands of them. It would seem that knowledge and experience should help in such cases. Sometimes they really help. If the symptoms are recognized at the very beginning, from time to time it is possible to stop the attack or at least reduce it to the so-called mild panic attack. However, more often than not, my internal dialogue looks something like this:0007

- It's just a panic attack. Everything is fine. Relax.

— And if not? Is it really something serious this time? Maybe a heart attack? Or a stroke?

- It's always a panic attack. Breathe as taught. Keep calm. Everything is fine.

— And if not?

- Everything is fine. Like the last 782 times you thought it wasn't a panic attack, but it turned out to be one.

- Okay. I am relaxing. Inhale - exhale. I say soothing phrases from meditation recordings. But if the last 782 attacks turned out to be panic attacks, does this mean that the 783rd one will turn out too? My stomach is spinning.

- Yes, you're right. Let's go from here.

While this dialogue is scrolling in my head, I get really hot. Perspiration appears. The left side of the face begins to tingle, then it becomes numb. (“Here, it looks like, indeed, a stroke!”) The chest is squeezing. The fluorescent lights in the office begin to flicker, causing dizziness. Everything is spinning before my eyes, the furniture is floating, it seems that I am about to fall. I grab onto the armrests of the chair. The dizziness intensifies, the office rotates, everything becomes somehow ephemeral, as if I was separated from the world around me by a translucent veil. My thoughts are a mess, but there are three main ones: “I’m going to vomit now. I'm dying. We need to get out of here." I rise from the table on shaky legs, sweating desperately. The important thing now is to get out. From the office, from the building, from this desperate situation. If I have a stroke, vomiting or death, let it not be in the editorial office. So let's swing.

So let's swing.

Desperately hoping no one will catch me on my way to the stairs, I rush towards the elevators. I tumble out through the fire door onto the stairs and, a little hopeful that so far everything is going well, I start down seven flights. By the third floor, my legs are already trembling. If I could think rationally, quiet the amygdala, and make proper use of the neocortex, I would reasonably conclude that this trembling is a natural consequence of the anatomical “fight or flight” response (causing skeletal muscle trembling) combined with physical overwork. But I am so dominated by panic logic that there is no question of rational thinking. And I take trembling in my legs for a symptom of complete physical exhaustion, in other words, I really seem to die now. As I make my last two flights, I wonder if I can call my wife on my cell phone, tell her I love her, and ask for help before I pass out and probably expire.

Once a new disease is born, it takes on a life of its own

David Sheehan, a psychiatrist who has studied and treated anxiety for 40 years, gives an example that clearly illustrates the unbearability of panic. In the 1980s World War II veteran, one of the first foot soldiers to set foot on Normandy on the day of the Allied landings, turned to Sheehan, seeking salvation from panic attacks. Was the assault on the Normandy coast, bullets, blood, dead bodies, and the palpable, imminent possibility of injury or death, less frightening than a panic attack at a peaceful dinner table, no matter how feverish the veteran now was due to a short circuit in his own neural circuits? That's right, said the veteran. “The fear he felt upon landing is nothing compared to the all-consuming horror that arose during his most nightmarish panic attack,” says Sheehan. “If he had the opportunity to choose, he would prefer to volunteer again for Normandy.”

In the 1980s World War II veteran, one of the first foot soldiers to set foot on Normandy on the day of the Allied landings, turned to Sheehan, seeking salvation from panic attacks. Was the assault on the Normandy coast, bullets, blood, dead bodies, and the palpable, imminent possibility of injury or death, less frightening than a panic attack at a peaceful dinner table, no matter how feverish the veteran now was due to a short circuit in his own neural circuits? That's right, said the veteran. “The fear he felt upon landing is nothing compared to the all-consuming horror that arose during his most nightmarish panic attack,” says Sheehan. “If he had the opportunity to choose, he would prefer to volunteer again for Normandy.”

Now panic attacks have become commonplace in both psychiatry and popular culture. Eleven million Americans today have been diagnosed with panic disorder at some point in their lives, like me. And yet, back in 1979, neither panic attacks nor panic disorder officially existed. To what do they owe their appearance? Imipramine.

To what do they owe their appearance? Imipramine.

In 1958, Donald Klein began his career as a psychiatrist at the Hillside Hospital in New York. And when imipramine appeared, Klein and a colleague randomly prescribed it to almost all 200 patients in their psychiatric department. However, Klein was most interested in 14 patients who had previously suffered from acute anxiety attacks, accompanied by "increased breathing and heart rate, weakness, a feeling of imminent death" (symptoms of anxiety neurosis, as it was then called according to the Freudian tradition), who had a noticeable or complete remission. , and in particular one of these patients who attracted the most attention of a psychiatrist. Previously, the patient kept rushing in a panic to the nurse on duty, claiming that he was dying. His sister took him by the hand, calmed him down with conversations, and after a few minutes the panic attack passed. This happened every few hours. Thorazine did not help the patient. But after several weeks of taking imipramine, the sisters noticed that regular visits to the duty officer had stopped. The general level of chronic anxiety in the patient remained quite high, however, acute paroxysms completely disappeared.

The general level of chronic anxiety in the patient remained quite high, however, acute paroxysms completely disappeared.

This got Klein thinking. If imipramine is able to block paroxysmal anxiety without affecting general or chronic anxiety, then something is not taken into account in the current theory of anxiety. According to the spectral theory of anxiety, the severity of a mental illness was determined by the intensity of anxiety underlying it: moderate anxiety led to psychoneurosis and various neurotic disorders, severe anxiety led to schizophrenia and manic depression. The provoking factors of acute panic attacks - bridges, elevators, airplanes - traditional Freudians endowed with a symbolic, often sexual meaning, which allegedly caused fear. "Nonsense! Klein objected to this. “Childhood trauma and suppression of sexual desires do not cause panic, but biological problems do.”

Klein came to the conclusion that the paroxysms of anxiety, which he called "panic attacks", are due to a biological failure that triggers the anxiety reaction of suffocation (by this term he meant an avalanche of physiological activity that causes, among other things, a feeling of sudden all-consuming horror). As soon as a person begins to suffocate, internal physiological sensors send a signal to the brain, causing strong nervous excitement, convulsive swallowing of air and a desire to run - adaptive survival mechanisms are activated. However, for some, according to Klein's theory of false alarm suffocation, these sensors do not work correctly, even when no lack of oxygen is observed. And then the person experiences a symptom complex of a panic attack. The source of panic is not a mental conflict, but a confusion of neural circuits, which is somehow unraveled by imipramine. According to Klein's observations, imipramine eliminated spontaneous panic attacks in most patients who suffered from them.

As soon as a person begins to suffocate, internal physiological sensors send a signal to the brain, causing strong nervous excitement, convulsive swallowing of air and a desire to run - adaptive survival mechanisms are activated. However, for some, according to Klein's theory of false alarm suffocation, these sensors do not work correctly, even when no lack of oxygen is observed. And then the person experiences a symptom complex of a panic attack. The source of panic is not a mental conflict, but a confusion of neural circuits, which is somehow unraveled by imipramine. According to Klein's observations, imipramine eliminated spontaneous panic attacks in most patients who suffered from them.

From 1962, when Klein published the results of his first experiment with imipramine, to 1980, when the DSM-III came out, gigantic changes took place in psychiatry's (and popular culture's) understanding of anxiety. “It’s hard to remember that for some 15 to 20 years even the concept of such [panic anxiety] did not exist,” Peter Kramer, a psychiatrist at Brown University, was surprised in his book Listening to Prozac (Listening to Prozac, 1993). — Neither during my medical studies, nor during my internship in a psychiatric clinic (both at 1970s) I have never come across a patient with a diagnosis of "panic anxiety". Today, panic disorder is diagnosed quite often (it affects about 18% of Americans), and the term "panic attack" from the lexicon of psychiatrists has penetrated into everyday speech.

— Neither during my medical studies, nor during my internship in a psychiatric clinic (both at 1970s) I have never come across a patient with a diagnosis of "panic anxiety". Today, panic disorder is diagnosed quite often (it affects about 18% of Americans), and the term "panic attack" from the lexicon of psychiatrists has penetrated into everyday speech.

Panic disorder was the first of the mental illnesses to be discovered through an observed reaction to drugs: imipramine cures panic, so there is a panic disorder. However, "first" does not mean "only": soon this phenomenon (when the drug allows you to highlight the syndrome with which it fights) was destined to repeat itself. In an announcement inviting on October 1956 in a lecture by Miltown developer Frank Berger, it was said that tranquilizers successfully treat high blood pressure, anxiety, nervous excitement, "nervous stomach", "rule nerves" and "housewife nerves." None of these ailments, then or now, were listed in the American Psychiatric Association's Manual of Diagnosis and Statistical Recording of Mental Disorders, which raises the logical question of what, in fact, Miltown was called to fight - with real psychiatric disorders or with the era itself. , softening the impact of "the hardships of today's life," as Berger called them in his lecture.

, softening the impact of "the hardships of today's life," as Berger called them in his lecture.

The emergence of a new drug therapy invariably raises the question of where the line lies between anxiety as a psychiatric disorder and anxiety as a common everyday problem. In the history of pharmacology, this repeats itself time and again: an increase in the number of tranquilizers is followed by an increase in diagnosed anxiety disorders; the replenishment of the arsenal of antidepressants is followed by an increase in depression. Leaving at 1980 AD DSM-III marked at least a partial debunking of Freudian ideas and the victory of biological psychiatry. (One medical historian called the DSM-III the "mortal blow" to psychoanalysis.) Down with neurosis! They were replaced by anxiety disorders: social anxiety disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and panic disorder with and without agoraphobia. Pharmacological evidence by Donald Klein has prevailed.

Pharmacological evidence by Donald Klein has prevailed.

However, in shifting mental illness from the Freudian paradigm into the realm of medical diagnosis, the new edition of the Handbook declared "disordered" or "sick" to be those who had previously been considered simply "neurotic". This has played into the hands of pharmaceutical companies, which have grown the target audience and the market for medicines. But did the sick win?

If you dig a little deeper into the process of writing the DSM-III, the claims to scientific rigor seem rather ephemeral. In some places, the criteria in the new categories look taken from the ceiling. (Why do you need four out of 13 symptoms for panic disorder, and not three or five? Why must symptoms persist for six months, rather than five or seven, for a formal diagnosis of social anxiety disorder?) DSM-III editorial board director Robert Spitzer admits years later, that many decisions were made in a hurry. If a disease was lobbied too aggressively, it was included in the corpus (now it is clear why the third edition of the Handbook was so swollen compared to the second: 494 pages against the previous 100 and 265 diagnoses against the previous 182).

Time magazine reported that the San Diego Zoo managed to tame a wild lynx with librium

David Sheehan was also on the DSM-III editorial board. One evening in the mid-1970s, he recalls, a section of the editorial board went out to dinner at a Manhattan restaurant. Over wine, a conversation began about a study by Donald Klein, during which it turned out that imipramine blocks panic attacks. Seemingly compelling pharmacological evidence that panic disorder is different from other anxiety disorders. As Sheehan says, “This is how panic disorder was born. Later, when more wine was poured, the psychiatrists gathered around the table recalled a colleague who, while not suffering from panic attacks, was still experiencing constant anxiety. How to call such a state? After all, he is worried in principle, in general. Great, let it be "generalized (generalized) anxiety disorder." And now the glasses are being raised to the birth of a new disease. For the next 30 years, the world will collect information about her. ” Sheehan, a burly Irishman who today runs a psychiatric center in Florida, is considered almost a renegade in professional circles. He himself does not hide his intentions to “destroy the prevailing belief” about the existence of a difference between panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, so his sarcastic story about the birth of generalized anxiety disorder is probably better not to be taken at face value. However, Sheehan, who has studied and treated anxiety for decades, notices one important fact: it is worth giving birth to a new disease, and then it lives its own life. Research accumulates around it, it is diagnosed in patients, it takes root in the scientific and mass consciousness.

” Sheehan, a burly Irishman who today runs a psychiatric center in Florida, is considered almost a renegade in professional circles. He himself does not hide his intentions to “destroy the prevailing belief” about the existence of a difference between panic disorder and generalized anxiety disorder, so his sarcastic story about the birth of generalized anxiety disorder is probably better not to be taken at face value. However, Sheehan, who has studied and treated anxiety for decades, notices one important fact: it is worth giving birth to a new disease, and then it lives its own life. Research accumulates around it, it is diagnosed in patients, it takes root in the scientific and mass consciousness.

Although the empty psychiatric clinics and the sharp increase in the number of prescriptions for antidepressants in the late 1950s were the merit of Thorazine, and he, and other medicines, were far from the commercial success of Miltown. This explains Leo Sternbach, a chemist at the Hoffmann-La Roche branch in New Jersey, received a directive from management: "Invent a new tranquilizer. " On an April afternoon in 1957, Sternbach's laboratory assistant, while cleaning in the laboratory, came across a powder (official name R 0-5-090), synthesized a year ago, but never tested. Without much hope, as Sternbach later said, he handed over the substance for testing on animals. He did it on May 7, his 44th birthday. Happy birthday! And so, almost by accident and almost unconsciously, Sternbach developed the first benzodiazepine, chlordiazepoxide, which would be given the trade name Librium (from equilibrium, equilibrium), and would become the forerunner of Valium, Ativan, Klonopin, and Xanax, the main sedatives of our era. Due to an error in the chemical process R 0-5-090 differed in molecular structure from all the other 40 compounds synthesized by Sternbach. (Its six-carbon benzene ring pairs with a five-carbon-two-nitrogen diazepine ring, hence the name benzodiazepine.) Clinical and pharmacological research director Hoffmann tested the new substance on cats and mice and, to his own surprise, , found that, despite being 10 times more powerful than Miltown, it clearly did not affect the motor functions of the experimental animals.

" On an April afternoon in 1957, Sternbach's laboratory assistant, while cleaning in the laboratory, came across a powder (official name R 0-5-090), synthesized a year ago, but never tested. Without much hope, as Sternbach later said, he handed over the substance for testing on animals. He did it on May 7, his 44th birthday. Happy birthday! And so, almost by accident and almost unconsciously, Sternbach developed the first benzodiazepine, chlordiazepoxide, which would be given the trade name Librium (from equilibrium, equilibrium), and would become the forerunner of Valium, Ativan, Klonopin, and Xanax, the main sedatives of our era. Due to an error in the chemical process R 0-5-090 differed in molecular structure from all the other 40 compounds synthesized by Sternbach. (Its six-carbon benzene ring pairs with a five-carbon-two-nitrogen diazepine ring, hence the name benzodiazepine.) Clinical and pharmacological research director Hoffmann tested the new substance on cats and mice and, to his own surprise, , found that, despite being 10 times more powerful than Miltown, it clearly did not affect the motor functions of the experimental animals. Time magazine reported that the San Diego Zoo managed to tame a wild lynx with the help of lybrium. “A medicine that pacifies tigers! Will it not affect women's nerves?" asked the headline.

Time magazine reported that the San Diego Zoo managed to tame a wild lynx with the help of lybrium. “A medicine that pacifies tigers! Will it not affect women's nerves?" asked the headline.

Benzodiazepines have been the leading pharmaceutical treatment for anxiety for more than half a century. However, it was not until the late 1970s that Italian neuroscientist Erminio Costa, another eminent member of Steve Brody's lab at the National Institutes of Health, has finally identified their distinctive chemical mechanism: they act on a neurotransmitter called gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which inhibits the frequency of neural firing. What I really care about is a more pragmatic question: How does long-term benzodiazepine use affect my brain? At the moment I have been taking benzodiazepines (Valium, Klonopin, Ativan, Xanax) in different doses and with different frequency for more than 30 years. For several years of this period, I sat on tranquilizers around the clock for months.

“Valium, Librium and other drugs in this category are harmful to the brain. I have seen the damage to the cerebral cortex clearly caused by these drugs, and I begin to doubt that they are reversible,” warned University of Tennessee physician David Knott back in 1976. Over the past three decades, dozens of articles have appeared in scientific journals noting cognitive impairment in long-term benzodiazepine users. A 1984 study by Malcolm Leider found a physical decrease in brain volume in people who were on tranquilizers for long periods of time. (Further research has shown that different benzodiazepines cause different parts of the brain to shrivel up.) Is that why, at 44, having taken tranquilizers almost nonstop for decades, I feel dumber than ever?

I have seen the damage to the cerebral cortex clearly caused by these drugs, and I begin to doubt that they are reversible,” warned University of Tennessee physician David Knott back in 1976. Over the past three decades, dozens of articles have appeared in scientific journals noting cognitive impairment in long-term benzodiazepine users. A 1984 study by Malcolm Leider found a physical decrease in brain volume in people who were on tranquilizers for long periods of time. (Further research has shown that different benzodiazepines cause different parts of the brain to shrivel up.) Is that why, at 44, having taken tranquilizers almost nonstop for decades, I feel dumber than ever?

In the "Open Reading" section, we publish excerpts from books in the form in which they are provided by the publishers. Minor abbreviations are indicated by ellipsis in square brackets. The opinion of the author may not coincide with the opinion of the editors.

causes, symptoms and treatment of all types of diseases in the FSCC FMBA

Panic attacks are quite common. Statistically, about 30% of the population experience one or more brief episodes of unmotivated anxiety attacks. Panic attacks on a regular basis are suffered by 5% of people, and in a latent (hidden) form - about 10%. As a rule, middle-aged people are susceptible to episodes of panic attacks. It is worth noting that more and more elderly people are now seeking help with complaints of anxiety episodes.

Statistically, about 30% of the population experience one or more brief episodes of unmotivated anxiety attacks. Panic attacks on a regular basis are suffered by 5% of people, and in a latent (hidden) form - about 10%. As a rule, middle-aged people are susceptible to episodes of panic attacks. It is worth noting that more and more elderly people are now seeking help with complaints of anxiety episodes.

Causes of panic attacks

An emotional experience such as anxiety is of paramount importance in the development of panic attacks. Anxiety is a condition that is manifested both emotionally by a feeling of anxiety, excitement, and physically by increased heart rate, excessive sweating, chest tightness, and weakness. Panic attacks are different for everyone. In some people, the component of motor excitation predominates, others note such respiratory disorders as shortness of breath, lack of air. Some people have gastrointestinal disorders (nausea, flatulence, diarrhea).

All the processes described above are vegetative manifestations of the anxiety state.

The feeling of anxiety is characteristic of every person and is normally an adaptive mechanism. For example, a student experiences anxiety on the eve of a major exam. But anxiety can also be pathological. It often happens that an anxious state takes possession of a person in situations that do not pose a real threat at all. Maladaptive (pathological) anxiety is characterized by inadequate perception of the situation as threatening. These anxiety states interfere with many daily tasks. The person believes that he is not able to cope with a possible threat.

Risk factors

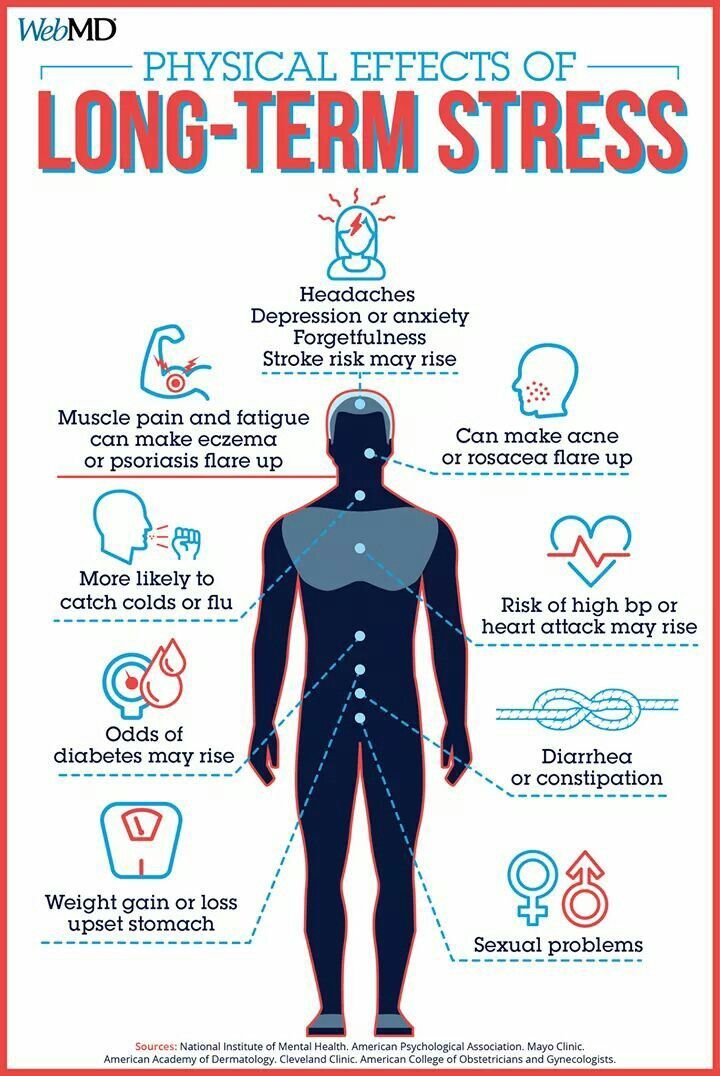

Stress, physical and emotional overload, alcohol consumption, lack of sleep, chronic diseases can trigger the development of panic attacks.

These factors, affecting the autonomic nervous system, change the normal course of physiological processes. For example, drinking alcohol leads to increased heart rate, increased sweating, and nausea. Lack of sleep causes a person to lose energy. A person thinks about these symptoms, he becomes confident that violations occur in the body. Such thoughts are responsible for the appearance of anxiety. Against this background, there is an active release of the stress hormone - adrenaline, the symptoms of the autonomic nervous system intensify.

Such thoughts are responsible for the appearance of anxiety. Against this background, there is an active release of the stress hormone - adrenaline, the symptoms of the autonomic nervous system intensify.

A person begins to think about the likelihood of developing such serious diseases as a stroke, heart attack, insanity. The feeling of anxiety transforms into a panic attack. After an episode of a panic attack, a feeling of weakness is characteristic. A vicious circle is formed, which is called the "vicious circle of anxiety." The described mechanism leads to social maladaptation.

What is a panic attack? Symptoms of panic attacks

A panic attack is a sudden attack of intense fear that causes severe physical reactions in the absence of a real danger or apparent cause.

Panic attacks usually begin suddenly, without warning. They can strike at any time during daily tasks. Panic episodes can be intermittent or occur quite frequently.

The complex of the following symptoms develops within minutes and may last up to 2 hours:

- palpitations

- violation of inhalation and exhalation

- tightness, chest pains

- headaches

- increased perspiration

- nausea, diarrhea

- dizziness, presyncope

- abdominal cramps

- chills and hot flashes

- feeling of numbness and tingling in certain areas of the body

The following mental changes are characteristic of panic attacks:0096

Every time after an attack, a person's greatest fear is a recurrence of an episode of a panic attack. Unfortunately, panic attacks actually tend to recur if you don't seek professional help in time.

Unfortunately, panic attacks actually tend to recur if you don't seek professional help in time.

It should be noted that clinical studies on panic attacks indicate that the experience of panic disorder does not lead to threatening severe outcomes, which patients fear so much (death from strokes, heart attacks).

However, panic attacks seriously change the mental background of a person, which leads to the following complications:

- development of social maladaptation. A person tries to avoid social contacts as much as possible in order to reduce the risk of developing an anxiety condition

- excessive painful control over one's physical condition, unreasonable suspiciousness

- the formation of secondary depression due to severe symptoms that a person experiences, the loss of all hope for recovery

- the use of alcohol, psychotropic substances in order to relieve tension, as a result, the development of dependence.

It is now very important to raise public awareness about the disorder of panic attacks. Anxiety can and should be corrected and treated. In most cases, patients turn to the stage when the disease is already protracted. As a result, reduced working capacity, financial problems, loss of social contacts.

Anxiety can and should be corrected and treated. In most cases, patients turn to the stage when the disease is already protracted. As a result, reduced working capacity, financial problems, loss of social contacts.

For the treatment of panic episodes, we use the author's method of therapy, which allows you to heal from panic attacks in 10-12 sessions.

Therapy is aimed at relieving symptoms that block a person's full life. Therapy allows you to look at yourself from the outside, change your attitude towards yourself, realize that it is possible to control reality for your own benefit and maximum comfort. Consolidation of the result occurs with the help of hypnosuggestive techniques.

Our method is effective and affordable. Its application gives positive results in a short time.

Treatment of panic attacks in the hospital FSCC FMBA

Doctors of our center carry out complex treatment of patients subject to panic attacks in a neurological hospital.

Panic attacks are known to be accompanied by manifestations from various body systems. At the same time, the patient develops an idea of serious violations in the work of internal organs, while the basis of panic attacks is a change in the mental background. It is the correction of the mental state that underlies the treatment of panic attacks.

Round-the-clock stay of the patient under the supervision of a multidisciplinary team of hospital doctors makes it possible to conduct an examination, identify real disorders and abnormalities in the functioning of internal organs. The results of examinations, conversations with doctors, including psychotherapists, help the patient understand that the cause of the development of panic attacks lies in the mental imbalance that has arisen.

Doctors of our center have been successfully using the author's technique for a long time, which allows for 10-12 sessions to achieve recovery and release the patient from panic attacks, as well as to consolidate the positive result obtained.