Childhood trauma amnesia

Memories of childhood abuse: dissociation, amnesia, and corroboration

. 1999 May;156(5):749-55.

doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.749.

J A Chu 1 , L M Frey, B L Ganzel, J A Matthews

Affiliations

Affiliation

- 1 Dissociative Disorders and Trauma Program, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA 02478, USA.

- PMID: 10327909

- DOI: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.749

J A Chu et al. Am J Psychiatry. 1999 May.

. 1999 May;156(5):749-55.

doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.749.

Authors

J A Chu 1 , L M Frey, B L Ganzel, J A Matthews

Affiliation

- 1 Dissociative Disorders and Trauma Program, McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA 02478, USA.

- PMID: 10327909

- DOI: 10.1176/ajp.156.5.749

Abstract

Objective: This study investigated the relationship between self-reported childhood abuse and dissociative symptoms and amnesia. The presence or absence of corroboration of recovered memories of childhood abuse was also studied.

The presence or absence of corroboration of recovered memories of childhood abuse was also studied.

Method: Participants were 90 female patients admitted to a unit specializing in the treatment of trauma-related disorders. Participants completed instruments that measured dissociative symptoms and elicited details concerning childhood physical abuse, sexual abuse, and witnessing abuse. Participants also underwent a structured interview that asked about amnesia for traumatic experiences, the circumstances of recovered memory, the role of suggestion in recovered memories, and independent corroboration of the memories.

Results: Participants reporting any type of childhood abuse demonstrated elevated levels of dissociative symptoms that were significantly higher than those in subjects not reporting abuse. Higher dissociative symptoms were correlated with early age at onset of physical and sexual abuse and more frequent sexual abuse. A substantial proportion of participants with all types of abuse reported partial or complete amnesia for abuse memories. For physical and sexual abuse, early age at onset was correlated with greater levels of amnesia. Participants who reported recovering memories of abuse generally recalled these experiences while at home, alone, or with family or friends. Although some participants were in treatment at the time, very few were in therapy sessions during their first memory recovery. Suggestion was generally denied as a factor in memory recovery. A majority of participants were able to find strong corroboration of their recovered memories.

A substantial proportion of participants with all types of abuse reported partial or complete amnesia for abuse memories. For physical and sexual abuse, early age at onset was correlated with greater levels of amnesia. Participants who reported recovering memories of abuse generally recalled these experiences while at home, alone, or with family or friends. Although some participants were in treatment at the time, very few were in therapy sessions during their first memory recovery. Suggestion was generally denied as a factor in memory recovery. A majority of participants were able to find strong corroboration of their recovered memories.

Conclusions: Childhood abuse, particularly chronic abuse beginning at early ages, is related to the development of high levels of dissociative symptoms including amnesia for abuse memories. This study strongly suggests that psychotherapy usually is not associated with memory recovery and that independent corroboration of recovered memories of abuse is often present.

Similar articles

-

More questions about recovered memories.

Piper A Jr. Piper A Jr. Am J Psychiatry. 2000 Aug;157(8):1346. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.8.1346. Am J Psychiatry. 2000. PMID: 10910814 No abstract available.

-

Dissociation, childhood interpersonal trauma, and family functioning in patients with somatization disorder.

Brown RJ, Schrag A, Trimble MR. Brown RJ, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2005 May;162(5):899-905. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.5.899. Am J Psychiatry. 2005. PMID: 15863791

-

Traumatic memories: do we need to invoke special mechanisms?

Hembrooke H, Ceci SJ.

Hembrooke H, et al. Conscious Cogn. 1995 Mar;4(1):75-82. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1995.1006. Conscious Cogn. 1995. PMID: 7497105 No abstract available.

Hembrooke H, et al. Conscious Cogn. 1995 Mar;4(1):75-82. doi: 10.1006/ccog.1995.1006. Conscious Cogn. 1995. PMID: 7497105 No abstract available. -

Neural mechanisms in dissociative amnesia for childhood abuse: relevance to the current controversy surrounding the "false memory syndrome".

Bremner JD, Krystal JH, Charney DS, Southwick SM. Bremner JD, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 1996 Jul;153(7 Suppl):71-82. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.7.71. Am J Psychiatry. 1996. PMID: 8659644 Review.

-

Evaluation of the evidence for the trauma and fantasy models of dissociation.

Dalenberg CJ, Brand BL, Gleaves DH, Dorahy MJ, Loewenstein RJ, Cardeña E, Frewen PA, Carlson EB, Spiegel D. Dalenberg CJ, et al. Psychol Bull.

2012 May;138(3):550-88. doi: 10.1037/a0027447. Epub 2012 Mar 12. Psychol Bull. 2012. PMID: 22409505 Review.

2012 May;138(3):550-88. doi: 10.1037/a0027447. Epub 2012 Mar 12. Psychol Bull. 2012. PMID: 22409505 Review.

See all similar articles

Cited by

-

Predictors of Suicide Ideation and Attempt Planning in a Large Sample of New Zealand Help-Seekers.

Shepherd D, Taylor S, Csako R, Liao AT, Duncan R. Shepherd D, et al. Front Psychiatry. 2022 Feb 25;13:794775. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.794775. eCollection 2022. Front Psychiatry. 2022. PMID: 35280160 Free PMC article.

-

Can the Cumulative Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Score Actually Identify the Victims of Intrafamilial Childhood Maltreatment? Findings from a Study in the Child Welfare System.

Kovács-Tóth B, Oláh B, Kuritárné Szabó I.

Kovács-Tóth B, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jun 27;18(13):6886. doi: 10.3390/ijerph28136886. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. PMID: 34198958 Free PMC article.

Kovács-Tóth B, et al. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jun 27;18(13):6886. doi: 10.3390/ijerph28136886. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021. PMID: 34198958 Free PMC article. -

The Boy Who Was Hit in the Face: Somatic Regulation and Processing of Preverbal Complex Trauma.

Finn H, Warner E, Price M, Spinazzola J. Finn H, et al. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2017 Jun 29;11(3):277-288. doi: 10.1007/s40653-017-0165-9. eCollection 2018 Sep. J Child Adolesc Trauma. 2017. PMID: 32318157 Free PMC article.

-

The Return of the Repressed: The Persistent and Problematic Claims of Long-Forgotten Trauma.

Otgaar H, Howe ML, Patihis L, Merckelbach H, Lynn SJ, Lilienfeld SO, Loftus EF. Otgaar H, et al. Perspect Psychol Sci.

2019 Nov;14(6):1072-1095. doi: 10.1177/1745691619862306. Epub 2019 Oct 4. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2019. PMID: 31584864 Free PMC article. Review.

2019 Nov;14(6):1072-1095. doi: 10.1177/1745691619862306. Epub 2019 Oct 4. Perspect Psychol Sci. 2019. PMID: 31584864 Free PMC article. Review. -

Association of Prepubertal and Postpubertal Exposure to Childhood Maltreatment With Adult Amygdala Function.

Zhu J, Lowen SB, Anderson CM, Ohashi K, Khan A, Teicher MH. Zhu J, et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019 Aug 1;76(8):843-853. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.0931. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019. PMID: 31241756 Free PMC article.

See all "Cited by" articles

MeSH terms

Forgotten Memories of Traumatic Events Get Some Backing from Brain-Imaging Studies

When adults claim to have suddenly recalled painful events from their childhood, are those memories likely to be accurate? This question is the basis of the “memory wars” that have roiled psychology for decades. And the validity of buried trauma turns up as a point of contention in court cases and in television and movie story lines.

And the validity of buried trauma turns up as a point of contention in court cases and in television and movie story lines.

Warnings about the reliability of a forgotten traumatic event that is later recalled—known formally as a delayed memory—have been endorsed by leading mental health organizations such as the American Psychiatric Association (APA). The skepticism is based on a body of research showing that memory is unreliable and that simple manipulations in the lab can make people believe they had an experience that never happened. Some prominent cases of recovered memory of child abuse have turned out to be false, elicited by overzealous therapists.

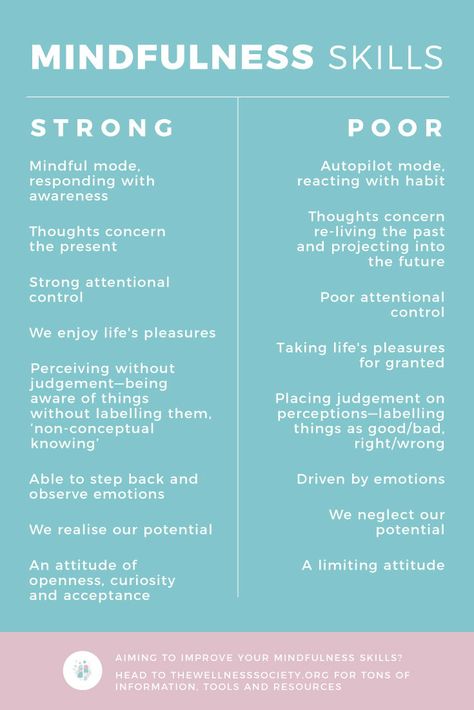

But psychotherapists who specialize in treating adult survivors of childhood trauma argue that laboratory experiments do not rule out the possibility that some delayed memories recalled by adults are factual. Trauma therapists assert that abuse experienced early in life can overwhelm the central nervous system, causing children to split off a painful memory from conscious awareness. They maintain that this psychological defense mechanism—known as dissociative amnesia—turns up routinely in the patients they encounter.

They maintain that this psychological defense mechanism—known as dissociative amnesia—turns up routinely in the patients they encounter.

Tensions between the two positions have often been framed as a debate between hard-core scientists on the false-memory side and therapists in clinical practice in the delayed-memory camp. But clinicians who also do research have been publishing peer-reviewed studies of dissociative amnesia in leading journals for decades. A study published in February in the American Journal of Psychiatry, the flagship journal of the APA, highlights the considerable scientific evidence that bolsters the arguments of trauma therapists.

The new paper uses magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to study amnesia, along with various other dissociative experiences that are often said to occur in the wake of severe child abuse, such as feelings of unreality and depersonalization. In an editorial published in the same issue of the journal, Vinod Menon, a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences at the Stanford University School of Medicine, praised the researchers for “[uncovering] a potential brain circuit mechanism underlying individual differences in dissociative symptoms in adults with early-life trauma and PTSD [post-traumatic stress disorder]. ”

”

Milissa Kaufman is senior author of the new MRI study and head of the dissociative disorders and trauma research program at McLean Hospital, a teaching hospital affiliated with Harvard Medical School. She notes that, as with earlier MRI studies of trauma survivors, this one shows that there is a neurological basis for dissociative symptoms such as amnesia. “We think that these brain studies can help reduce the stigma associated with our work,” Kaufman says. “Like many therapists who treat adult survivors of severe child abuse, I have seen some patients who recover memories of abuse.”

Since 1980, dissociative amnesia has been listed as a common symptom of PSTD in every edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)—psychiatry’s diagnostic bible. The condition has been backed up not just by psychiatric case studies but by dozens of studies involving victims of child abuse, natural disaster, torture, rape, kidnapping, wartime violence and other trauma..jpg)

For example, two decades ago psychiatrist James Chu, then director of the trauma and dissociative disorders program at McLean Hospital, published a study involving dozens of women receiving in-patient treatment who had experienced childhood abuse. A majority of the women reported previously having partial or complete amnesia of these events, which they typically remembered not in a therapy session but while at home alone or with family or friends. In many instances, Chu wrote, these women “were able to find strong corroboration of their recovered memories.”

False-memory proponents have warned that the use of leading questions by investigators might seed an untrue recollection. As psychiatrist Michael I. Goode wrote of Chu’s study in a letter to the editor, “Participants were asked ‘if there was a period during which they “did not remember that this [traumatic] experience happened.”’ With this question alone, the actuality of the traumatic experience was inherently validated by the investigators. ”

”

MRI studies conducted over the past two decades have found that PTSD patients with dissociative amnesia exhibit reduced activity in the amygdala—a brain region that controls the processing of emotion—and increased activity in the prefrontal cortex, which controls planning, focus and other executive functioning skills. In contrast, PTSD patients who report no lapse in their memories of trauma exhibit increased activity in the amygdala and reduced activity in the prefrontal cortex.

“The reason for these differences in neuronal circuitry is that PTSD patients with dissociative symptoms such as amnesia and depersonalization—a group comprising somewhere between 15 and 30 percent of all PTSD patients—shut down emotionally in response to trauma,” says Ruth Lanius, a professor of psychiatry and director of the PTSD research unit at the University of Western Ontario, who has conducted several of these MRI studies. Children may try to detach from abuse to avoid intolerable emotional pain, which can result in forgetting an experience for many years, she maintains. “Dissociation involves a psychological escape when a physical escape is not possible,” Lanius adds.

“Dissociation involves a psychological escape when a physical escape is not possible,” Lanius adds.

False-memory researchers remain skeptical of the brain-imaging studies. Henry Otgaar, a professor of legal psychology at Maastricht University in the Netherlands, who has co-authored more than 100 academic publications on false-memory research and who often serves as an expert witness for defendants in abuse cases, maintains that intact autobiographical memories are rarely—if ever—repressed. “These brain studies provide biological evidence just for the claims of patients who report memory loss due to dissociation,” he says. “There are many alternative explanations for these correlations—say, retrograde amnesia, in which the forgetting is due to a brain injury.”

In an effort to provide a firmer grounding for their arguments, Kaufman and her McLean colleagues used artificial intelligence to develop a model of the connections between diverse brain networks that could account for dissociative symptoms. They fed the computer MRI data on 65 women with histories of childhood abuse who had been diagnosed with PTSD, along with their scores on a commonly used inventory of dissociative symptoms. “The computer did the rest,” Kaufman says.

They fed the computer MRI data on 65 women with histories of childhood abuse who had been diagnosed with PTSD, along with their scores on a commonly used inventory of dissociative symptoms. “The computer did the rest,” Kaufman says.

Her key finding is that severe dissociative symptoms likely involve the connections between two specific brain networks that are active at the same time: the so-called default mode network—which kicks in when the mind is at rest and involves remembering the past and envisioning the future—and the frontoparietal control network—which is involved in problem-solving.

The McLean study is not the first attempt to apply machine learning to dissociative symptoms. In a paper published in the September 2019 issue of the British Journal of Psychiatry, researchers showed how MRI scans of the brain structures of 75 women—32 with dissociative identity disorder, for which dissociative amnesia is a key symptom, and 43 matched controls—could discriminate between people with or without the disorder nearly 75 percent of the time.

Kaufman says additional research needs to be carried out before clinicians can begin using brain connectivity as a diagnostic tool to assess the severity of dissociative symptoms in their patients. “This study is just a first step on the pathway to precision medicine in our field,” she says.

Richard Friedman, a professor of clinical psychiatry at Weill Cornell Medical College, considers the goal of the McLean researchers laudable. But he notes that the road ahead remains challenging and warns that the history of psychology is filled with “objective assessments” for a particular diagnosis or state of mind that never lived up to their hype. Friedman cites the case of lie-detector tests, in which false positives and false negatives abound.

While a brain-based test that could diagnose dissociative symptoms is not likely anytime soon, research on neurobiological explanations show the controversy over forgetting and remembering traumatic memories is far from settled.

Amnesia: types, symptoms, causes

Neurologist

SEMENOVA

Olga Vladimirovna

Experience 6 years

neurologist, head of the room for diagnostics and treatment of cognitive disorders

Make an appointment

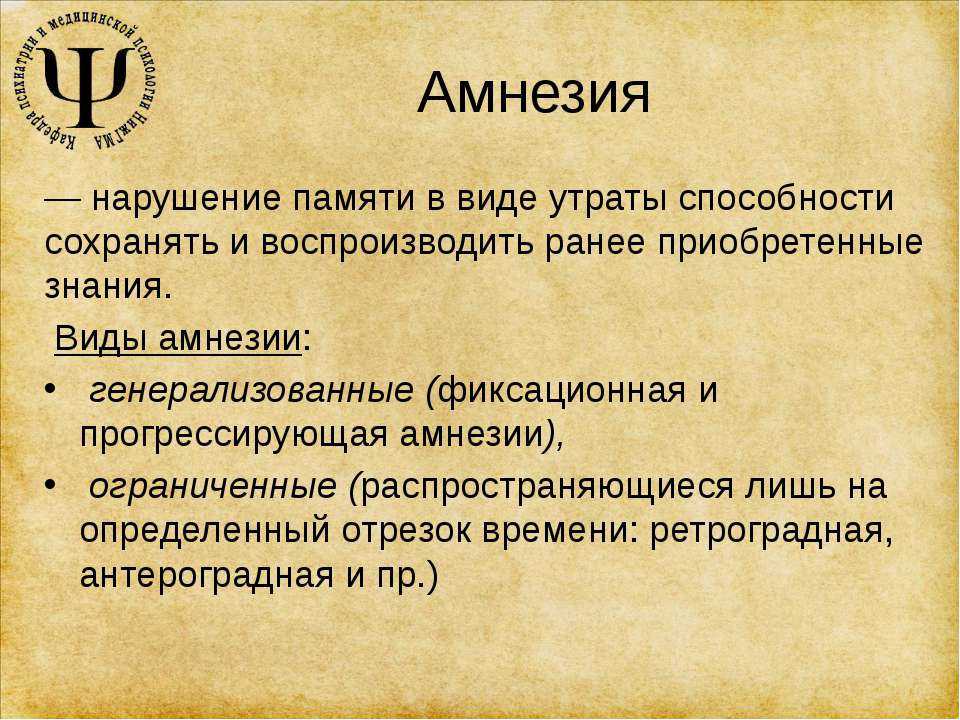

Amnesia is a human memory disorder that manifests itself in the form of a pathological loss of memories of life circumstances. Amnestic syndrome remains a common complication of neurological diseases, mental disorders, chronic intoxication or acute poisoning.

General

The absence of memories of past events is not always considered by doctors as a pathology. Childhood amnesia is common. Most people cannot recount the events of the first three years of their lives.

The main clinical manifestation of amnesia is the loss by a person of previously available memories of significant events of the past or the circumstances of recent actions. Amnestic syndrome remains a common manifestation of neurological and psychiatric pathologies.

Causes of memory disorder

The most common causes of amnesia are changes in the structures of the patient's brain. Metabolic, morphological or bioelectrical disorders occur against the background of:

- traumatic brain injury,

- brain tumors,

- cerebral hypoxia,

- neuroinfections,

- intoxications,

- degenerative diseases of the CNS,

- epilepsy.

Psychological traumas (abductions, rapes, traffic accidents, terrorist attacks) have a significant impact on the state of memory. The loss of memories becomes a defensive reaction against the background of the events that have occurred. Partial amnesia may result from delirium tremens, dissociative disorder, or schizophrenia.

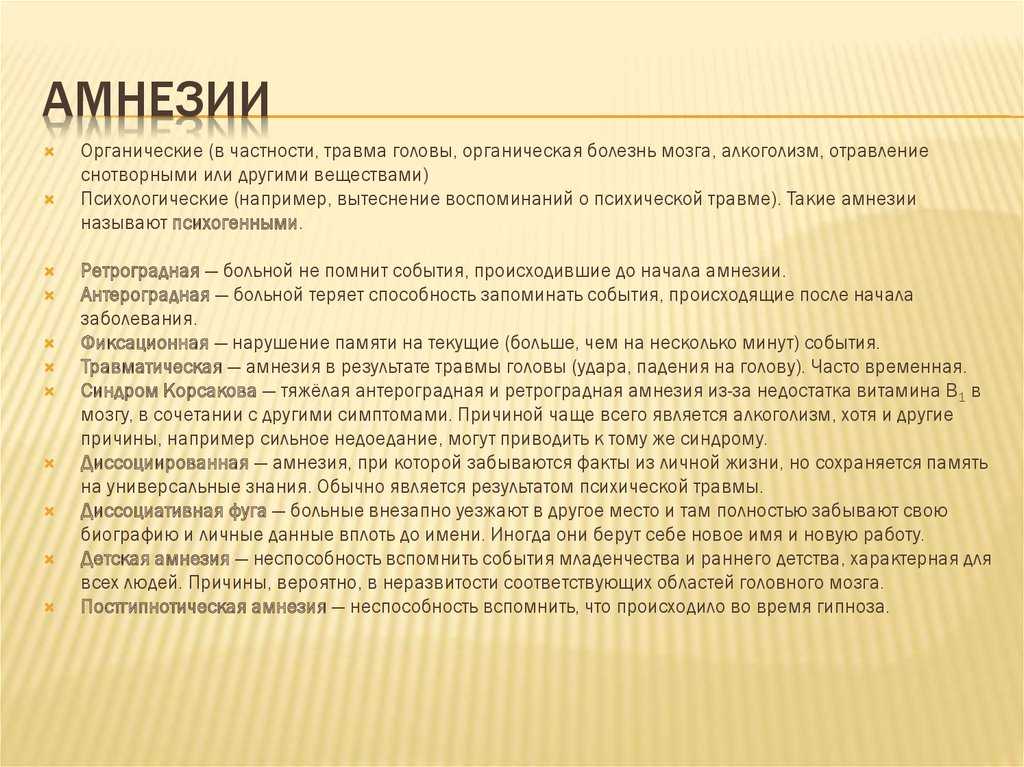

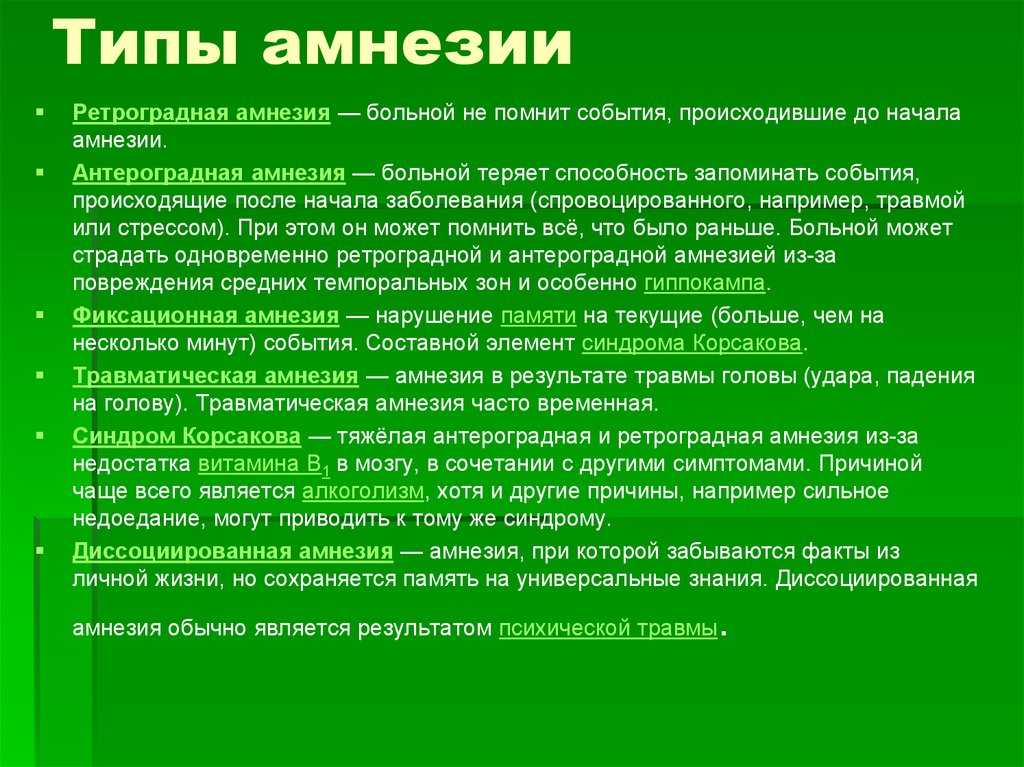

Types of amnestic syndromes

The basis for the classification of pathology are the characteristics of its completeness, chronological orientation and features of the course. During the diagnosis, doctors take into account all the parameters, since the patient's treatment strategy depends on them.

Neurologists distinguish three types of amnesia in accordance with the completeness of memory loss:

- absolute,

- partial,

- local.

In the first case, the patient cannot remember any events in a certain period of the past; in the second, the dissociative one has vague and fragmentary memories. Local amnestic disorders are diagnosed when a patient loses a certain skill or ability.

An extended classification takes into account the temporal location of events forgotten by a person in relation to the moment of occurrence of amnesia. Basic information about these types of pathology is presented in the table.

| The form | Characteristics |

| retrograde | The patient cannot remember events that occurred before the onset of the first symptoms of amnesia |

| Anterograde | The child or adult forgets events that occurred after the onset of the amnestic disorder |

| Anteroretrograde | Combines signs of retrograde and atherograde amnesia |

| Fixation | A person loses memories of current events, the time period stretches for several minutes |

The course of amnesia may be stationary (without dynamics), progressive or regressive. The latter option becomes the basis for the formation of a favorable prognosis regarding the complete recovery of the patient.

The latter option becomes the basis for the formation of a favorable prognosis regarding the complete recovery of the patient.

Symptoms of pathology

Symptoms of amnesia depend on the clinical form of the disease identified in the patient. The basic symptom is the inability of a person to remember events from a certain time period. The sequence of loss of memories is described in Ribot's law. First amnesic patients forget recent events, then facts of the recent past. At the last stage, there is a loss of memories of actions in the distant past. Memory recovery is carried out in reverse order.

Often, adults and children diagnosed with amnesia are faced with confabulations - fictional memories. They reflect the patient's desire to fill in the gaps in his own memory.

Symptoms of the amnestic syndrome can be combined with manifestations of the underlying pathology that led to disorders in the cerebral structures. So, with alcoholic delirium, sharp mood swings are observed, accompanied by bouts of euphoria and tantrums. The patient experiences thirst, bouts of nausea, suffers from loss of muscle tone. Amnesia on the background of alcoholic neurosis remains temporary.

The patient experiences thirst, bouts of nausea, suffers from loss of muscle tone. Amnesia on the background of alcoholic neurosis remains temporary.

Diagnostics

The diagnostic algorithm is individual for each patient. The set and sequence of actions of the neurologist is determined by the clinical picture of the pathology. A psychiatrist, narcologist, neurosurgeon and infectious disease specialist may be involved as consultants. Advanced diagnostic plan includes:

- history taking;

- assessment of neurological status;

- assessment of psychiatric status;

- CSF examination;

- general and biochemical blood tests.

An important diagnostic procedure is MRI of the cerebral vessels. The study of cerebral hemodynamics is performed with suspicion of a vascular genesis of amnesia.

Computed tomography of the brain is indicated for patients with traumatic brain injuries. The same method is used when doctors detect symptoms of malignant neoplasms in brain structures.

Treatment of amnestic syndrome

Drug treatment is prescribed to the patient based on the symptoms identified during the physical examination and additional studies. Pharmacotherapy is based on the following drugs:

- vasodilators and antiplatelet agents;

- neuroprotectors and antioxidants;

- anticholinesterase agents;

- nootropics;

- memantines.

These substances are designed to improve cerebral blood flow, optimize metabolic processes in neurons, slow down the progression of dementia, restore memory and stimulate the cognitive abilities of patients. Treatment for amnesia may include psychotherapy and exercise. In the presence of brain tumors, the patient is prescribed surgical intervention.

Prognosis and preventive measures

The success of treatment depends on the age of the patient, the underlying pathology and the causes of amnesia. Traumatic memory disorders are reversible - therapy is successful in 85% of cases. Degenerative changes in the central nervous system are characterized by a progressive course, which excludes the possibility of a complete recovery of the patient.

Degenerative changes in the central nervous system are characterized by a progressive course, which excludes the possibility of a complete recovery of the patient.

Preventive measures involve the observance of safety precautions during work and rest. These actions will allow the patient to avoid head injuries. At the first signs of intoxication, infections or vascular disorders, adults and children should seek medical help.

Questions and answers

At what age is amnesia most likely to develop?

Amnestic syndrome often develops in people over 65 years of age against the background of degenerative changes in cerebral structures. Patients representing other age groups experience amnesia after trauma, intoxication, or psychological shock.

Is it possible to restore memory without active drug treatment of amnesia?

Such a development of events is unlikely even with a regressing amnesic syndrome. The patient needs pharmacotherapy to eliminate metabolic or bioelectrical disorders in cerebral structures.

Causes of form amnesia - attack of amnesia treatment

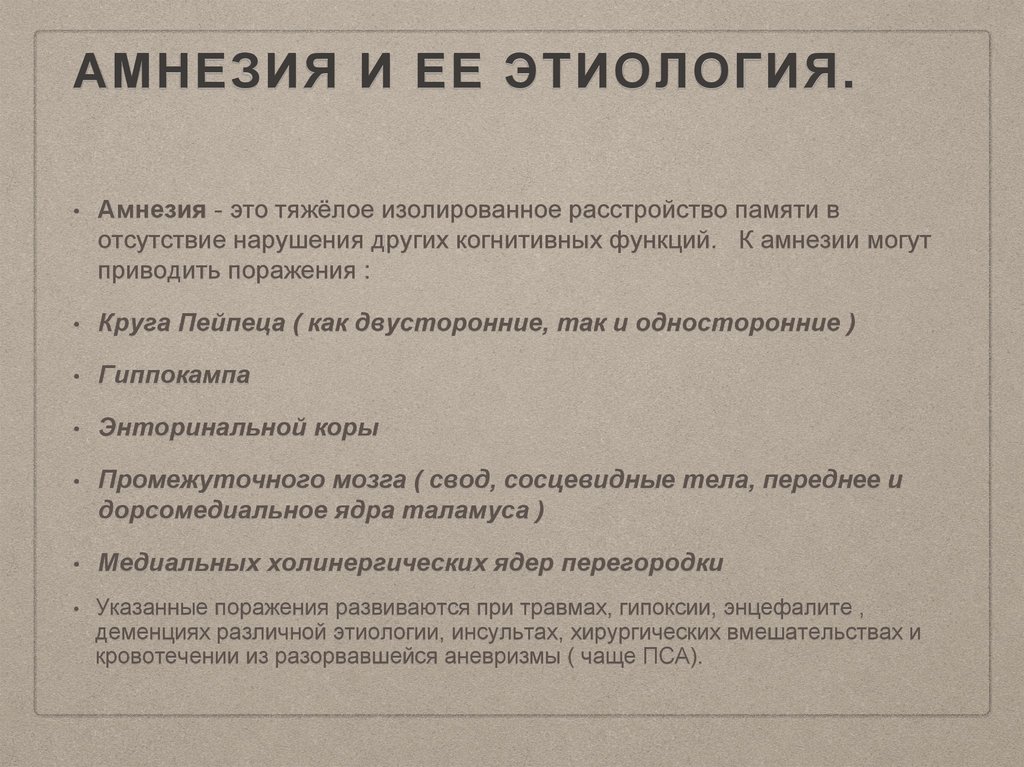

The term "amnesia" refers to such a violation in which the patient cannot recall any events from the past or information known to him. In addition, patients with amnesia may have serious problems with the formation of new memories. The origin of this pathology can be both psychogenic - for example, provoked by severe stress - and neurological in nature.

If we talk about the forms of amnesia and the causes of this disease, then doctors specializing in the study, detection and treatment of this disease distinguish 6 of its varieties:

- anterograde - a consequence of a traumatic brain injury, in which the events that have just occurred are erased from the patient's memory. A person may not remember what and in what company he ate for lunch, while his mind remains healthy. However, this form of amnesia can destroy the professional sphere of a person's life, as well as his family;

- retrograde amnesia can also be a complication of injury or disease of certain parts of the brain.

It is characterized by the disappearance from the memory of the patient of events that took place even before he had the first signs of this disease;

It is characterized by the disappearance from the memory of the patient of events that took place even before he had the first signs of this disease; - The transient global variety of this disease is manifested by the fact that a generally healthy person may experience memory lapses from time to time. Usually, the time period, the memory of which is “erased” in the patient, lasts no more than a day. However, this kind of amnesia is very disturbing for both the patients themselves and their families. In 80% of cases, the victims of this form of amnesia are the stronger sex over the age of 50;

- dissociative, which in most cases is provoked by severe stress - for example, it can occur in a person who was present at a brutal murder or an accident with serious consequences. It can both affect various stages of the patient's life, and “erase” from his memory some specific traumatic situation;

- childhood form of amnesia in which the patient is unable to recall events that occurred in the early years of his childhood.

Usually, experts attribute it to the fact that some areas of the patient's brain, for some reason, have not developed to the end;

Usually, experts attribute it to the fact that some areas of the patient's brain, for some reason, have not developed to the end; - A variety of amnesia provoked by the excessive use of strong drinks is called "Wernicke-Korsakov's psychosis".

Causes of amnesia

In the overwhelming majority of cases, the factors affecting the development of this pathology in a patient are damage to brain structures such as the hippocampus and/or thalamus. If we talk about the specific causes of amnesia, then they include:

- paralysis;

- encephalitis;

- insufficient supply of oxygenated arterial blood to the brain for a long time;

- alcohol dependence;

- depression;

- diseases associated with a violation of various functions of the brain - for example, dementia or Alzheimer's disease;

- taking certain pharmaceuticals;

- mechanical damage to the brain - for example, traumatic brain injuries resulting from a fight or accident;

- strong emotional upheavals.