Carbamazepine for bipolar

Carbamazepine (Tegretol) | NAMI: National Alliance on Mental Illness

Brand names:

- Tegretol®

- Tablet: 200 mg, 400 mg

- Chewable tablet: 100 mg

- Oral suspension: 100 mg/5 mL

- Tegretol XR®

- Extended release tablet: 100 mg, 200 mg, 400 mg

- Carbatrol®, Equetro®

- Extended release capsule: 100 mg, 200 mg, 300 mg

- Epitol®

- Tablet: 200 mg

Generic name: carbamazepine (kar ba MAZ e peen)

All FDA black box warnings are at the end of this fact sheet. Please review before taking this medication.

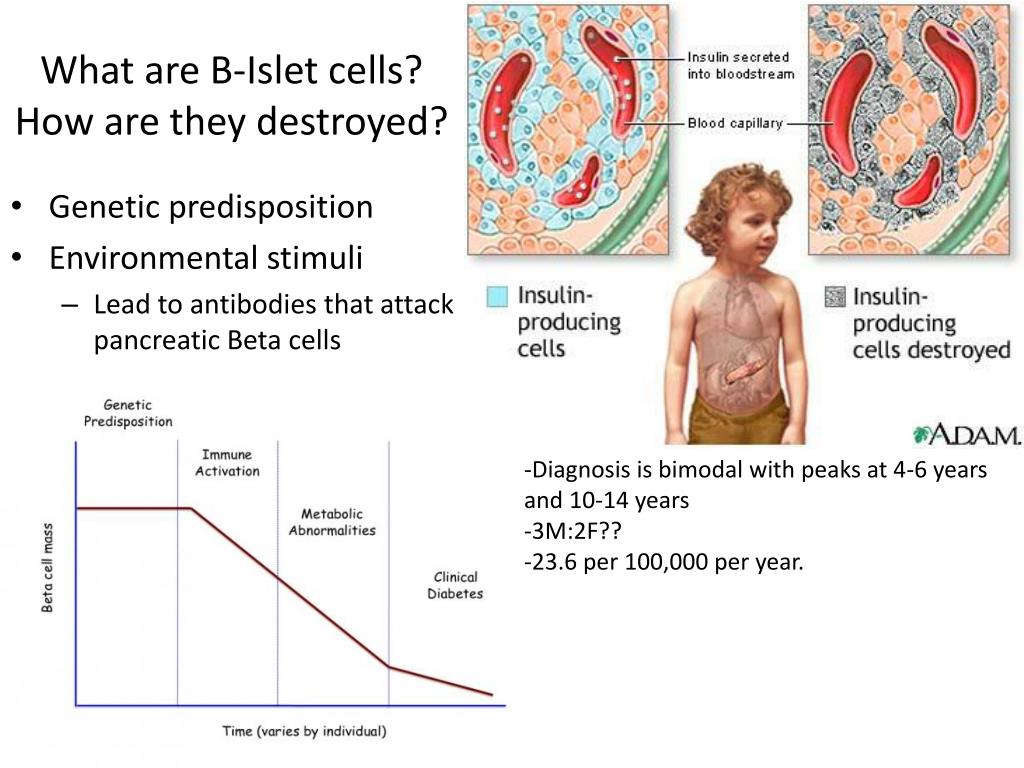

What Is Carbamazepine And What Does It Treat?

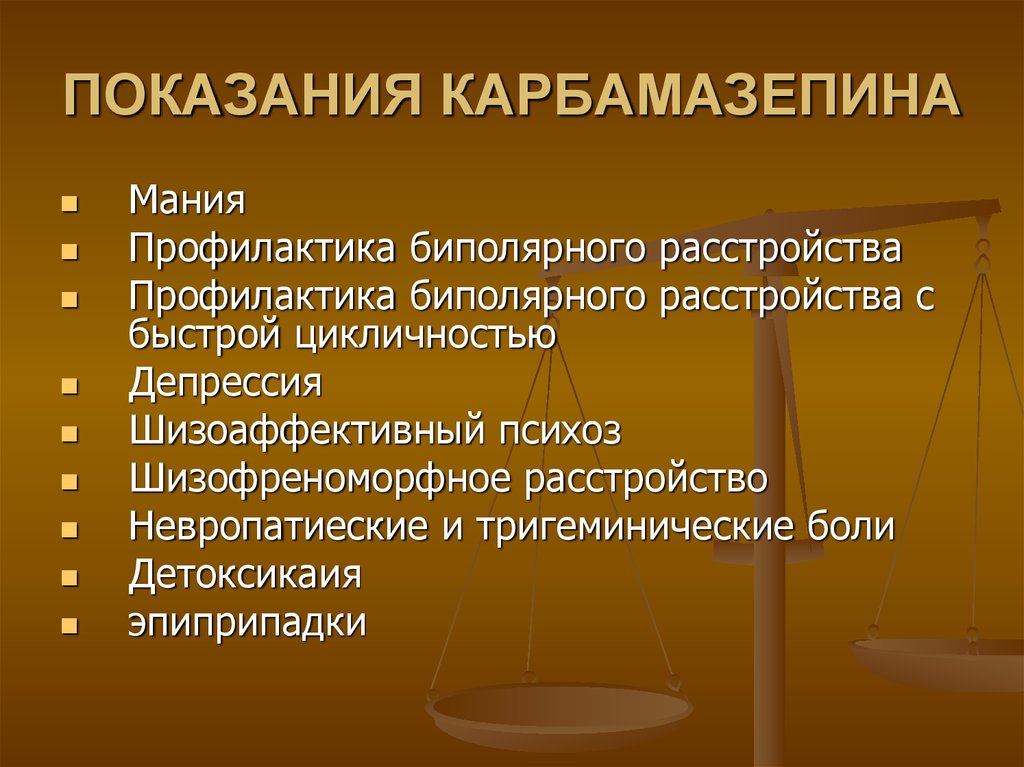

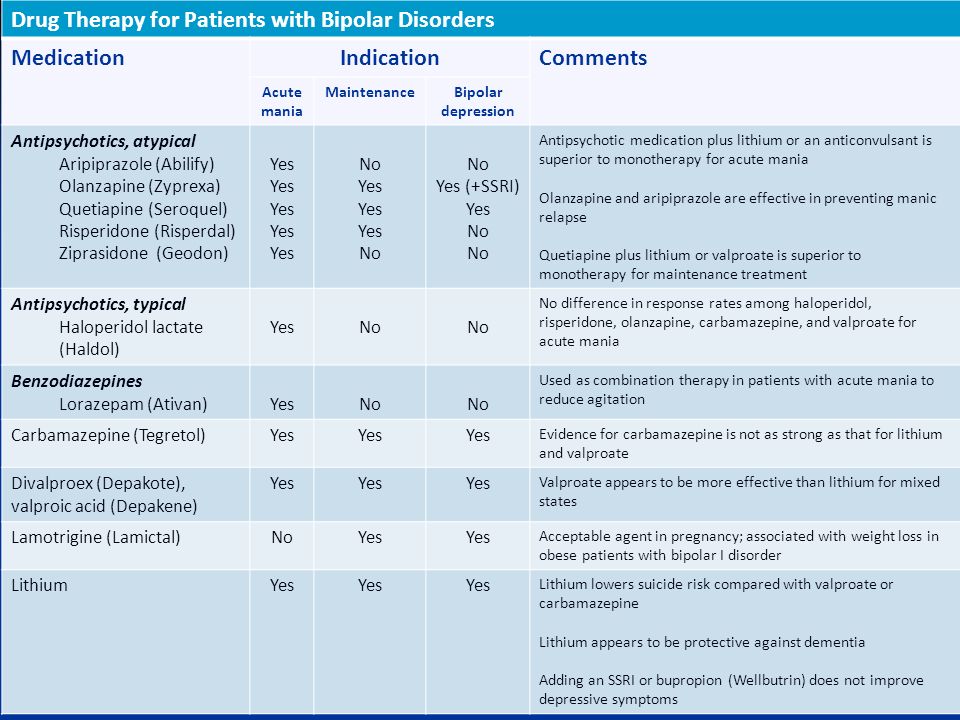

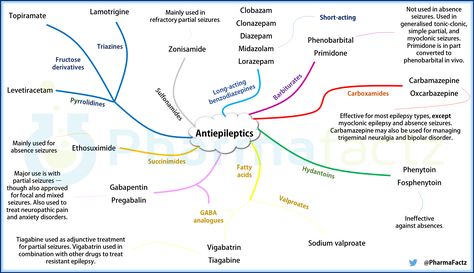

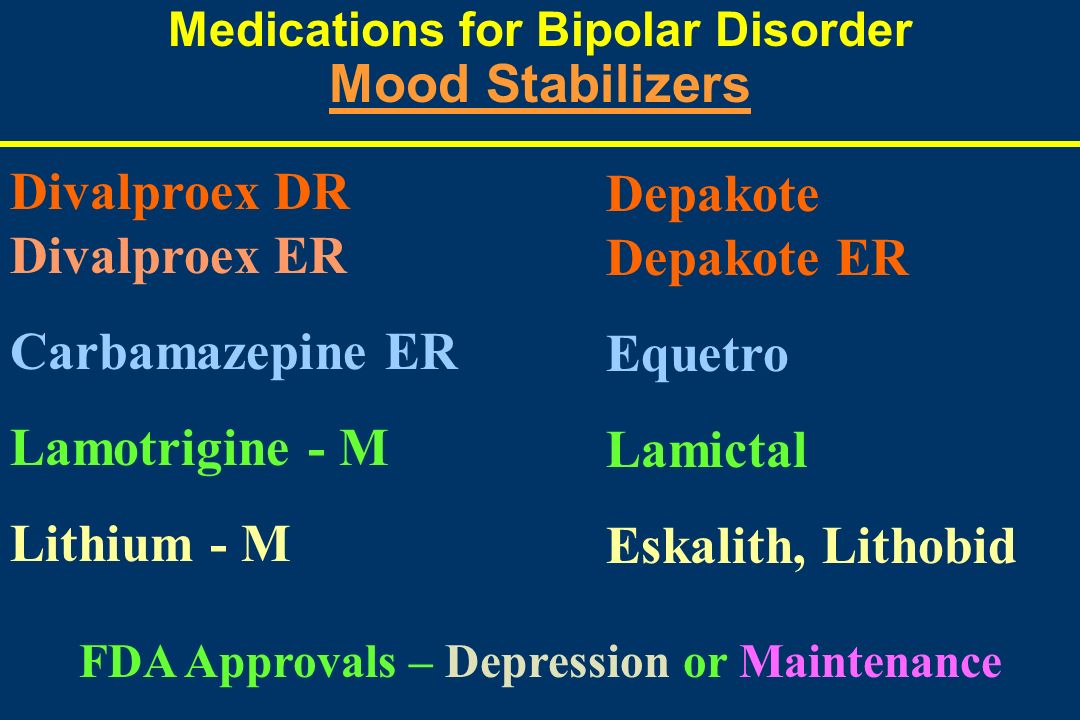

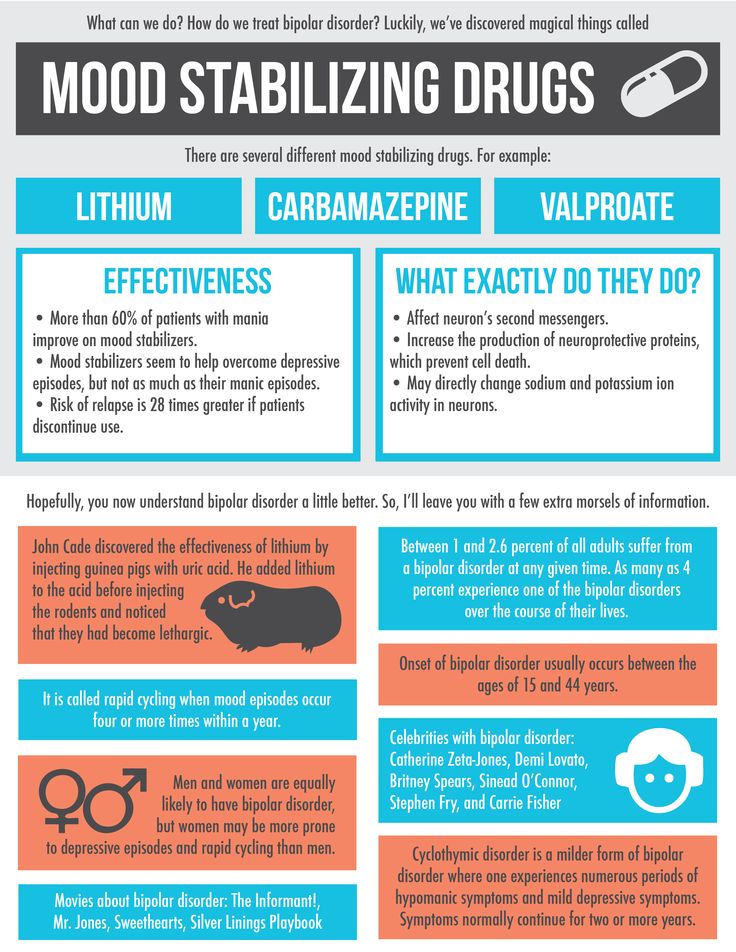

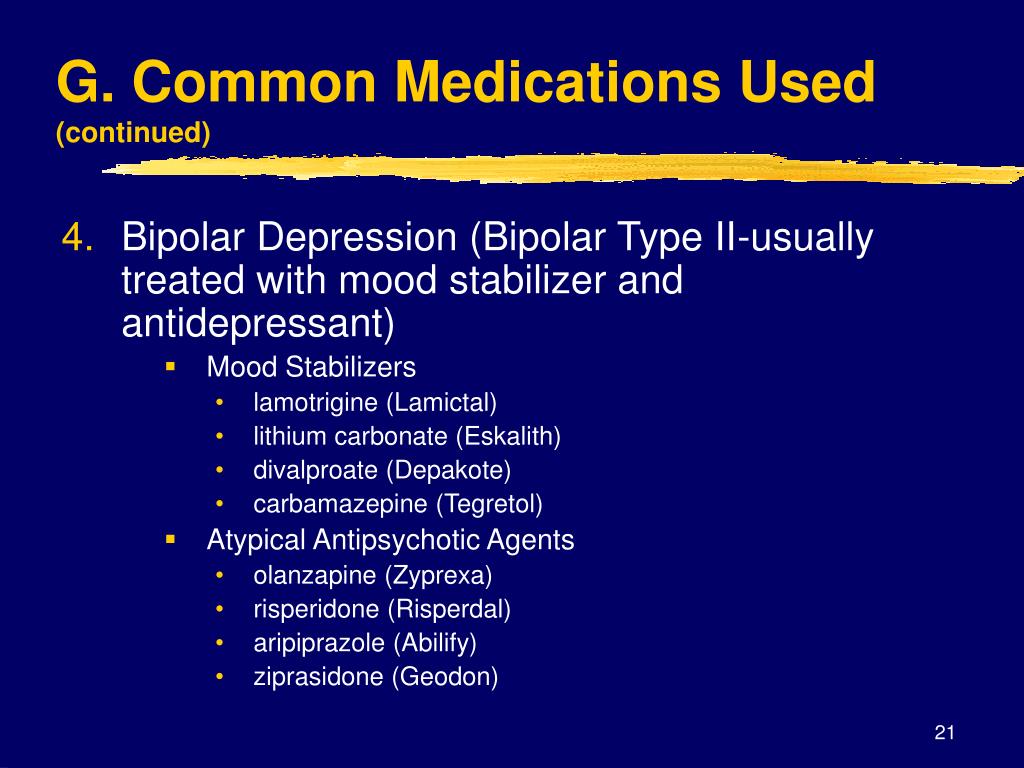

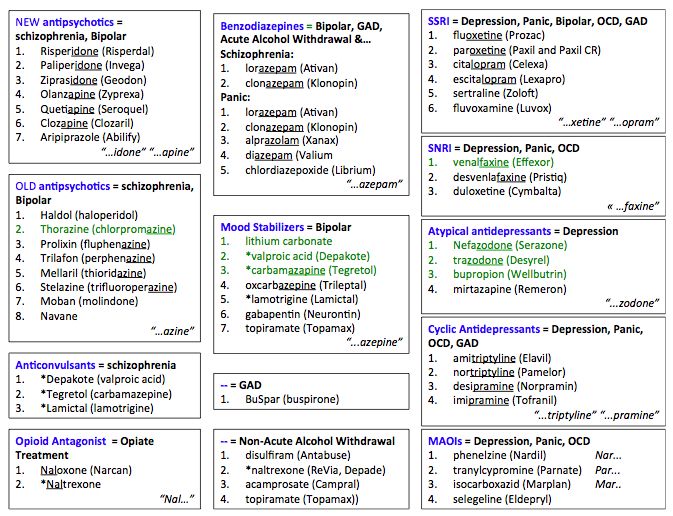

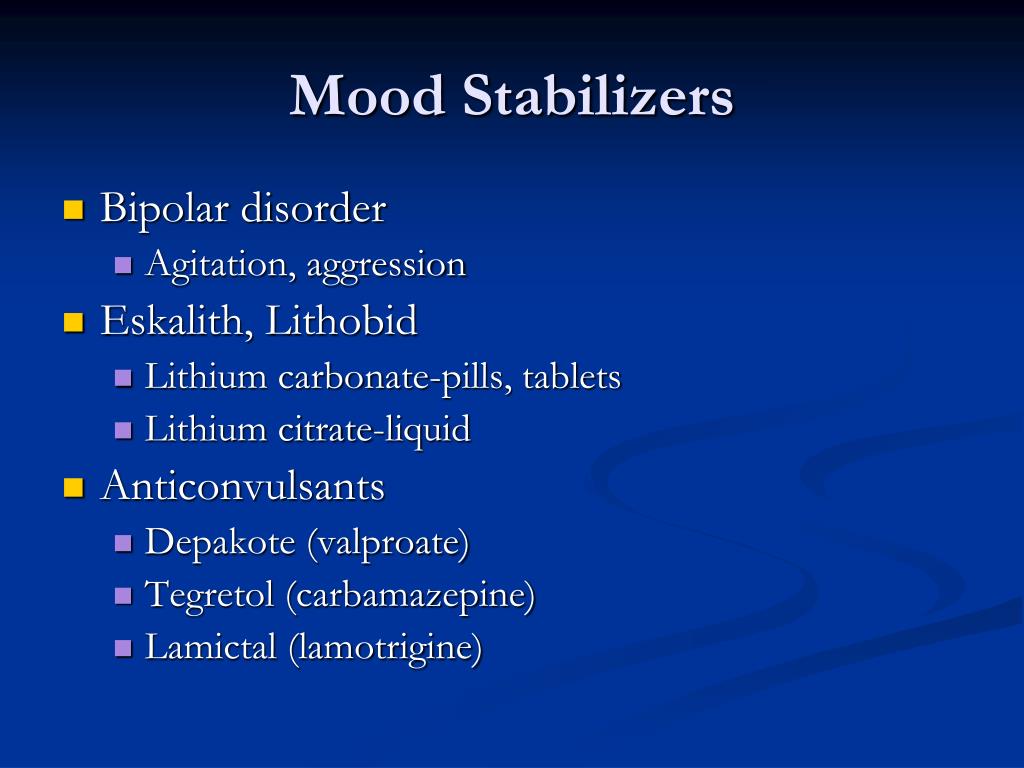

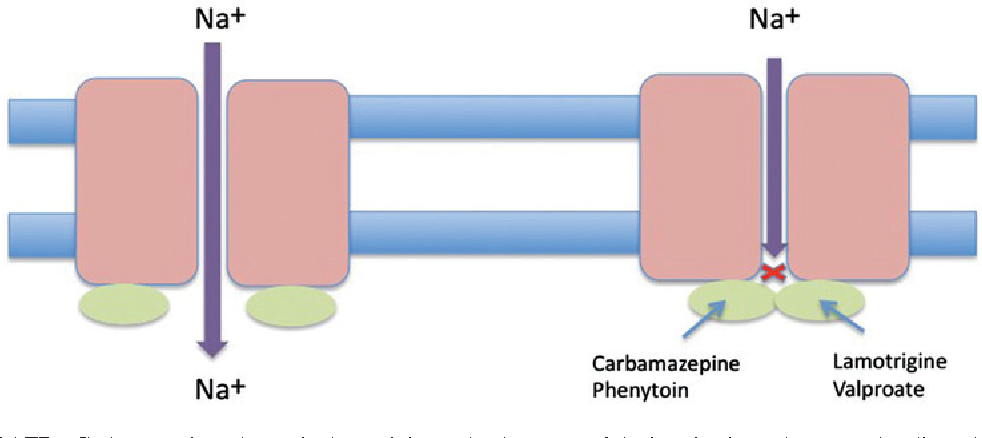

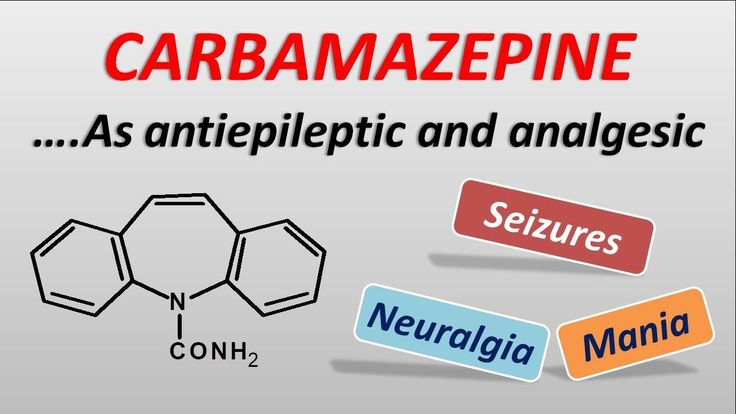

Carbamazepine is a mood stabilizer medication that works in the brain. It is approved for the treatment of bipolar 1 disorder (also known as manic depression) as well as for epilepsy and trigeminal neuralgia. Bipolar disorder involves episodes of depression and/or mania.

Symptoms of depression include:

- Depressed mood — feeling sad, empty, or tearful

- Feeling worthless, guilty, hopeless, or helpless

- Loss of interest or pleasure in normal activities

- Sleep and eat more or less than usual (for most people it is less)

- Low energy, trouble concentrating, or thoughts of death (suicidal thinking)

- Psychomotor agitation (‘nervous energy’)

- Psychomotor retardation (feeling like you are moving in slow motion)

Symptoms of mania include:

- Feeling irritable or “high”

- Having increased self esteem

- Feeling like you don’t need to sleep

- Feeling the need to continue to talk

- Feeling like your thoughts are too quick (racing thoughts)

- Feeling distracted

- Getting involved in activities that are risky or could have bad consequences (e.g., excessive spending)

Carbamazepine may also be helpful when prescribed “off-label” for behavioral or psychological symptoms of dementia. “Off-label” means that it hasn’t been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this condition. Your mental health provider should justify his or her thinking in recommending an “off-label” treatment. They should be clear about the limits of the research around that medication and if there are any other options.

“Off-label” means that it hasn’t been approved by the Food and Drug Administration for this condition. Your mental health provider should justify his or her thinking in recommending an “off-label” treatment. They should be clear about the limits of the research around that medication and if there are any other options.

What Is The Most Important Information I Should Know About Carbamazepine?

Bipolar disorder requires long-term treatment. Do not stop taking carbamazepine, even when you feel better. With input from you, your health care provider will assess how long you will need to take the medicine. Missing doses of carbamazepine may increase your risk for a relapse in your mood symptoms.

Do not stop taking carbamazepine or change your dose without talking to with your healthcare provider first.

In order for carbamazepine to work properly, it should be taken every day as ordered by your healthcare provider.

Periodically, your healthcare provider may ask you to provide a blood sample to make sure the appropriate level of medication is in your body and to assess for side effects, such as changes in blood cell counts.

Are There Specific Concerns About Carbamazepine And Pregnancy?

If you are planning on becoming pregnant, notify your healthcare provider so that he/she can best manage your medications. People living with bipolar disorder who wish to become pregnant face important decisions. It is important to discuss the risks and benefits of treatment with your doctor and caregivers.

Carbamazepine has been associated with and increased risk of defects of the head and face, fingernails, and developmental delay. There may be precautions to decrease the risk of this effect. Do not stop taking carbamazepine without first speaking to your healthcare provider. Discontinuing mood stabilizer medications during pregnancy has been associated with a significant increase in symptom relapse.

Regarding breast-feeding, caution is advised since carbamazepine does pass into breast milk. Talk with your doctor about whether or not it is safe to breastfeed while taking carbamazepine.

What Should I Discuss With My Healthcare Provider Before Taking Carbamazepine?

- Symptoms of your condition that bother you the most

- If you have thoughts of suicide or harming yourself

- Medications you have taken in the past for your condition, whether they were effective or caused any adverse effects

- If you experience side effects from your medications, discuss them with your provider.

Some side effects may pass with time, but others may require changes in the medication.

Some side effects may pass with time, but others may require changes in the medication. - Any other psychiatric or medical problems you have

- All other medications you are currently taking (including over the counter products, herbal and nutritional supplements) and any medication allergies you have

- Other non-medication treatment you are receiving, such as talk therapy or substance abuse treatment. Your provider can explain how these different treatments work with the medication.

- If you are pregnant, plan to become pregnant, or are breast-feeding

- If you drink alcohol or use illegal drugs

How Should I Take Carbamazepine?

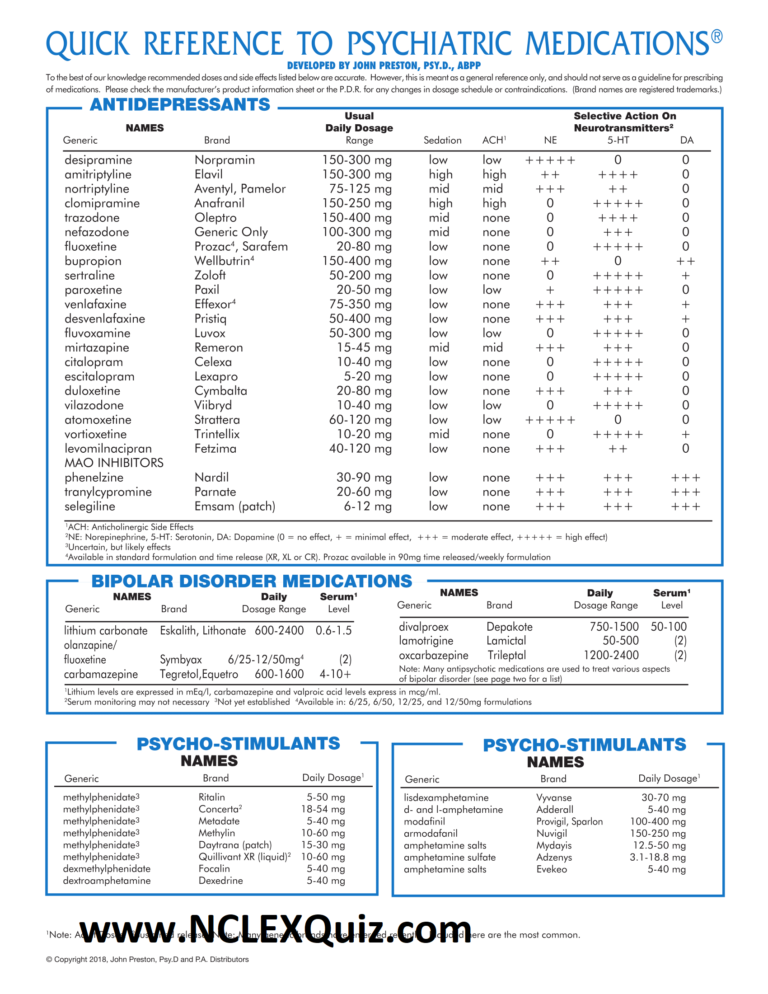

Carbamazepine is usually taken 2-4 times per day with or without food.

Typically patients begin at a low dose of medicine and the dose is increased slowly over several weeks.

The dose usually ranges from 200 mg to 1600 mg each day, but some patients may require more based on symptoms. Only your healthcare provider can determine the correct dose for you.

Carbamazepine suspension: Measure with a dosing spoon or oral syringe, which you can get from your pharmacy.

Extended-release capsules: Swallow whole or sprinkle onto food, such as applesauce or pudding and eat immediately. Do not chew the sprinkle capsule or contents.

Use a calendar, pillbox, alarm clock, or cell phone alert to help you remember to take your medication. You may also ask a family member or a friend to remind you or check in with you to be sure you are taking your medication.

What Happens If I Miss A Dose Of Carbamazepine?

If you miss a dose of carbamazepine, take it as soon as you remember, unless it is closer to the time of your next dose. Discuss this with your healthcare provider. Do not double your dose or take more than what is prescribed.

What Should I Avoid While Taking Carbamazepine?

Avoid drinking alcohol or using illegal drugs while you are taking carbamazepine. They may decrease the benefits (e.g., worsen your condition) and increase adverse effects (e. g., sedation) of the medication.

g., sedation) of the medication.

Avoid consuming large quantities (8 ounces or more) of fresh grapefruit juice, as this can increase levels of carbamazepine and increase your risk of side effects or rash.

What Happens If I Overdose With Carbamazepine?

If an overdose occurs call your doctor or 911. You may need urgent medical care. You may also contact the poison control center at 1-800-222-1222.

A specific treatment to reverse the effects of carbamazepine does not exist.

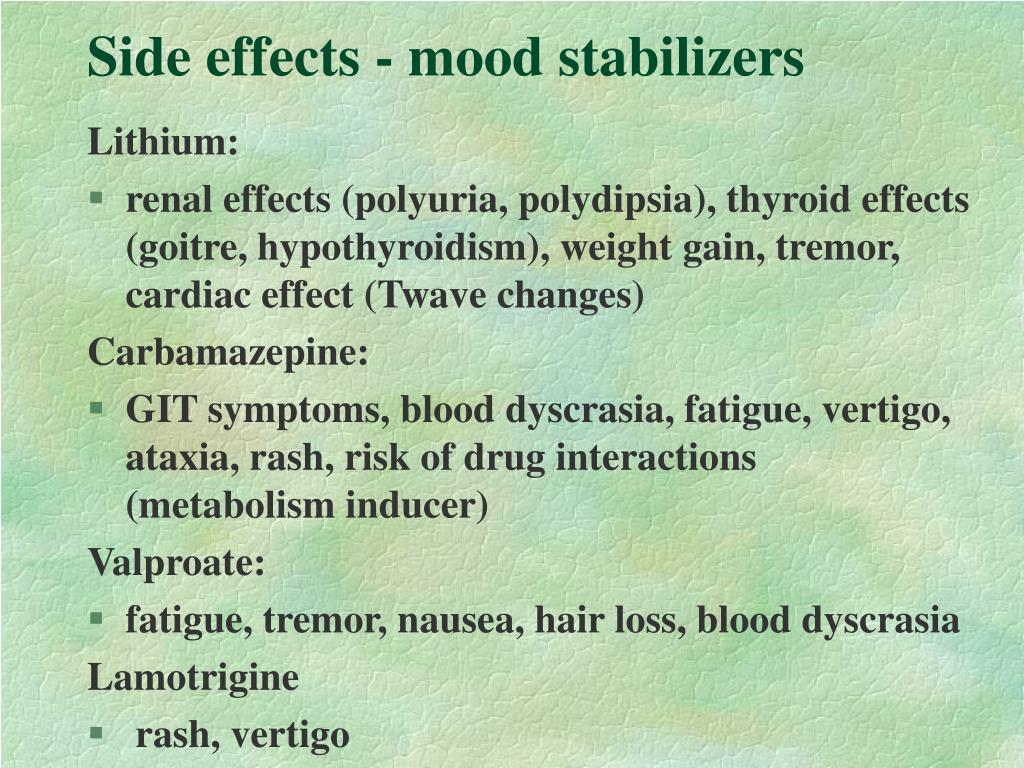

What Are Possible Side Effects Of Carbamazepine?

Common side effects

- Dizziness or drowsiness

- Unsteadiness when standing or walking

- Nausea or vomiting

- Dry mouth

- Constipation

- Blurry or double vision

Rare/serious side effects

Carbamazepine can cause a decrease in the body’s sodium level. Some signs of low sodium include nausea, tiredness, lack of energy, headache, confusion, or more frequent or more severe seizures.

Carbamazepine may cause rare but serious blood problems including low white blood cell counts. Symptoms may include: fever, sore throat, or other infections that come and go or do not go away, easy bruising, red or purple spots on your body, bleeding gums or nose bleeds, or severe fatigue or weakness. Your doctor will occasionally order blood work to monitor for this.

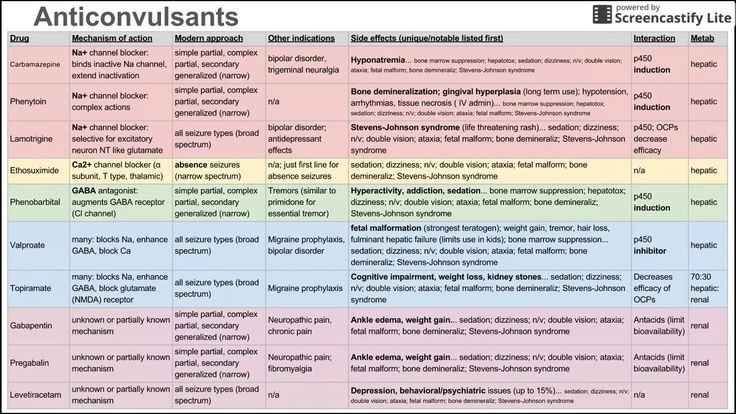

In rare cases (<1%) a severe, spreading rash with blistering of the skin in patches over the entire body along with fever, headache and cough can occur (Stevens-Johnson syndrome). Although this is rare with carbamazepine, discontinuation of this medication is necessary. Rare cases of severe allergic reactions have been reported. Symptoms include swelling of the face, eyes, lips, or tongue, difficulty swallowing or breathing. If you experience any of these side effects, it is important to seek medical care immediately.

Studies have found that individuals who take antiepileptic medications including carbamazepine have suicidal thoughts or behaviors up to twice as often than individuals who take placebo (inactive medication). These thoughts or behaviors occurred in approximately 1 in 500 patients taking the antiepileptic class of medications. If you experience any thoughts or impulses to hurt yourself, you should contact your doctor immediately.

These thoughts or behaviors occurred in approximately 1 in 500 patients taking the antiepileptic class of medications. If you experience any thoughts or impulses to hurt yourself, you should contact your doctor immediately.

Are There Any Risks For Taking Carbamazepine For Long Periods Of Time?

To date, there are no known problems associated with long term use of carbamazepine. It is a safe and effective medication when used as directed.

It is important to note that some of the side effects listed above (particularly changes in blood sodium, rash, and suicidal thoughts) may continue to occur or worsen if you continue taking the medication. It is important to follow up with your doctor for blood work and to contact your doctor immediately if you notice any skin rash or changes in mood or behavior.

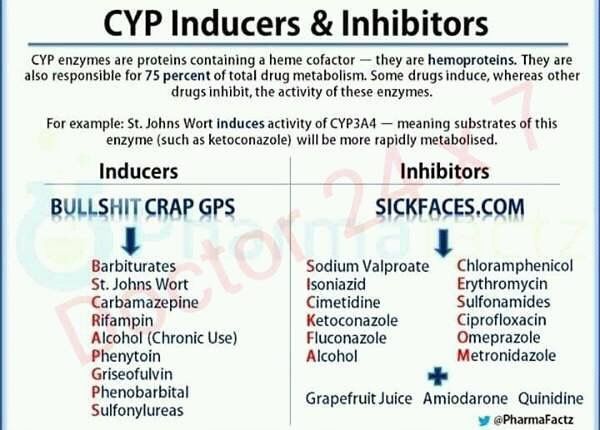

What Other Medications May Interact With Carbamazepine?

The following medications may increase the level and effects of carbamazepine:

- The mood stabilizer and antiseizure medication valproic acid/divalproex (Depakote®)

- Certain antibiotics, such as ciprofloxacin (Cipro®), erythromycin (Ery-tab®), clarithrymycin (Biaxin®)

- Medications for heartburn or reflux, such as cimetidine (Tagamet®) and omeprazole (Prilosec®)

- Antifungal medications, such as ketoconazole (Nizoral®), fluconazole (Diflucan®), itraconazole (Sporanox®), voriconazole (Vfend®)

- Certain heart medications, such as diltiazem (Cardizem®) or verapamil (Calan®, Isoptin®)

- Certain medications used for mood or sleep, such as trazodone (Desyrel®) or nefazodone (Serzone®)

The following medications may decrease the level and effect of carbamazepine:>/p>

- Phenytoin (Dilantin®), phenobarbital, primidone (Mysoline®)

- Rifampin (Rifadin®)

Carbamazepine may decrease the level and effects of:

- Oral contraceptives (birth control pills)

- Certain medications used for psychiatric disorders, such as lurasidone (Latuda®), aripiprazole (Abilify®), alprazolam (Xanax®), escitalopram (Lexapro®), trazodone (Desyrel®), and nefazodone (Serzone®)

- Certain heart medications, such as diltiazem (Cardizem®) or verapamil (Calan®, Isoptin®)

- Anti-rejection medications used in organ transplants, like tacrolimus (Prograf®) and cyclosporine (Neoral®, Sandimmune®)

- Certain cholesterol medications, like simvastatin (Zocor®), atorvastatin (Lipitor®)

- The blood thinner warfarin (Coumadin®)

- Antiseizure medications like phenytoin (Dilantin®), phenobarbital, and valproic acid/divalproex (Depakote®), lamotrigine (Lamictal®)

How Long Does It Take For Carbamazepine To Work?

It is very important to tell your doctor how you feel things are going during the first few weeks after you start taking carbamazepine. It will probably take several weeks to see big enough changes in your symptoms to decide if carbamazepine is the right medication for you.

It will probably take several weeks to see big enough changes in your symptoms to decide if carbamazepine is the right medication for you.

Mood stabilizer treatment is generally needed lifelong for persons with bipolar disorder. Your doctor can best discuss the duration of treatment you need based on your symptoms and illness.

Summary of FDA Black Box Warnings

Serious skin reactions and HLA-B*1502 allele

Serious and sometimes fatal skin reactions have been reported with carbamazepine use. These reactions may be accompanied by mucous membrane ulcers, fever, or painful rash. Seek medical care immediately at the first sign of rash, as treatment must be stopped to avoid progression of the rash. These reactions are estimated to occur in 1 to 6 per 10,000 new users in countries with mainly Caucasian populations, but the risk in some Asian countries is estimated to be about 10 times higher. HLA-B*1502 is found almost exclusively in patients with ancestry across broad areas of Asia. Patients with ancestry in genetically at-risk populations should be screened for the presence of HLA-B*1502 prior to initiating treatment with carbamazepine.

Patients with ancestry in genetically at-risk populations should be screened for the presence of HLA-B*1502 prior to initiating treatment with carbamazepine.

Aplastic anemia and agranulocytosis

Carbamazepine has been associated with a condition where the body does not make enough new blood cells and also with a decrease in white blood cells. People taking carbamazepine can be at an increased risk of infection if white blood cell counts drop too low.

Provided by

(June 2019)

©2019 The College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists (CPNP) and the National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI). CPNP and NAMI make this document available under the Creative Commons Attribution-No Derivatives 4.0 International License. Last Updated: January 2016.

This information is being provided as a community outreach effort of the College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists. This information is for educational and informational purposes only and is not medical advice. This information contains a summary of important points and is not an exhaustive review of information about the medication. Always seek the advice of a physician or other qualified medical professional with any questions you may have regarding medications or medical conditions. Never delay seeking professional medical advice or disregard medical professional advice as a result of any information provided herein. The College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists disclaims any and all liability alleged as a result of the information provided herein.

This information is for educational and informational purposes only and is not medical advice. This information contains a summary of important points and is not an exhaustive review of information about the medication. Always seek the advice of a physician or other qualified medical professional with any questions you may have regarding medications or medical conditions. Never delay seeking professional medical advice or disregard medical professional advice as a result of any information provided herein. The College of Psychiatric and Neurologic Pharmacists disclaims any and all liability alleged as a result of the information provided herein.

Carbamazepine treatment of bipolar disorder: a retrospective evaluation of naturalistic long-term outcomes

- Journal List

- BMC Psychiatry

- v.12; 2012

- PMC3410809

BMC Psychiatry. 2012; 12: 47.

2012; 12: 47.

Published online 2012 May 23. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-12-47

1 and 2,3

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

Background

Carbamazepine (CBZ) has been used in the treatment of bipolar disorder, both in acute mania and maintenance therapy, since the early 1970s. Here, we report a follow-up study of CBZ-treated bipolar patients in the Taipei City Psychiatric Centre.

Methods

Bipolar patients diagnosed according to the DSM-IV system and treated with CBZ at the Taipei City Psychiatric Centre had their charts reviewed to evaluate the efficacy and side effects of this medication during an average follow-up period of 10 years.

Results

A total of 129 bipolar patients (45 males, mean age: 45.7 ± 10.9 year) were included in the analysis of CBZ efficacy used alone (n = 63) or as an add-on after lithium (n = 50) or valproic acid (n = 11), or the both of them (n = 5). The mean age of disease onset was 24.6 ± 9.5 years. The mean duration of CBZ use was 10.4 ± 5.2 year. The mean dose used was 571.3 ± 212.6 mg/day with a mean plasma level of 7.8 ± 5.9 μg/mL. Mean body weight increased from 62.0 ± 13.4 kg to 66.7 ± 13.1 kg during treatment. The frequencies of admission per year before and after CBZ treatment were 0.33 ± 0.46 and 0.14 ± 0.30, respectively. The most common side effects targeted the central nervous system (24%), including dizziness, ataxia and cognitive impairment. Other common side effects were gastrointestinal disturbances (3.6%), tremor (3.6%), skin rash (2.9%), and blurred vision (2.9%). Eighty-eight patients (68.2%) were taking antipsychotics concomitantly. Ninety-six patients (74.4%) needed to use benzodiazepines concomitantly. Sixty-three (48.8%) patients had zero episodes in a 10-year follow-up period, compared to all patients having episodes prior to treatment. Using variable analysis, we found better response to CBZ in males than in females.

The mean age of disease onset was 24.6 ± 9.5 years. The mean duration of CBZ use was 10.4 ± 5.2 year. The mean dose used was 571.3 ± 212.6 mg/day with a mean plasma level of 7.8 ± 5.9 μg/mL. Mean body weight increased from 62.0 ± 13.4 kg to 66.7 ± 13.1 kg during treatment. The frequencies of admission per year before and after CBZ treatment were 0.33 ± 0.46 and 0.14 ± 0.30, respectively. The most common side effects targeted the central nervous system (24%), including dizziness, ataxia and cognitive impairment. Other common side effects were gastrointestinal disturbances (3.6%), tremor (3.6%), skin rash (2.9%), and blurred vision (2.9%). Eighty-eight patients (68.2%) were taking antipsychotics concomitantly. Ninety-six patients (74.4%) needed to use benzodiazepines concomitantly. Sixty-three (48.8%) patients had zero episodes in a 10-year follow-up period, compared to all patients having episodes prior to treatment. Using variable analysis, we found better response to CBZ in males than in females.

Conclusions

CBZ is efficacious in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder in naturalistic clinical practice, either as monotherapy or in combination with other medications. CBZ is well tolerated by most patients in this patient group.

Keywords: Bipolar disorder, Carbamazepine, Maintenance therapy

Relapse in patients with bipolar disorder is a common problem. More than 90% of patients will have a recurrent episode, and it is also the cause of long-term morbidity and mortality [1,2]. Due to the chronic nature of this illness, there is a need for long-term maintenance treatment to prevent or attenuate the risk of relapse [3]. Lithium is the classic mood stabilizer used in treating acute and chronic bipolar disorder. However, studies have suggested that an estimated 20–40% of patients may have an inadequate prophylactic response to this drug [4,5]. Undesirable side effects and a narrow therapeutic index also make it less than ideal for many patients. This has led to efforts to investigate the potential utility of other mood stabilizers in maintenance therapy.

This has led to efforts to investigate the potential utility of other mood stabilizers in maintenance therapy.

Carbamazepine (CBZ), the first anticonvulsant used in bipolar disorder, was recognized as a useful medication in the 1970s [6-8]. Moreover, it was found to be compatible with lithium in the treatment of acute mania in small-scale trials [9,10]. In Taiwan, CBZ has been increasingly used to treat bipolar disorder [11]. Its efficacy for treating acute mania was recently reconfirmed following the completion of large-scale, randomized, placebo-controlled trials in North America using extended-release CBZ [12,13].

Despite the widespread clinical use of mood-stabilizer combinations for the long-term treatment of patients with bipolar disorder, research on the risks and benefits of this practice is limited. In recent decades, only a few studies have focused on the use of CBZ for the maintenance of bipolar disorder [14-18]. The results of a 2-year follow-up study showed approximately equal effects when comparing CBZ and lithium in the prevention of mood episodes [18]. In a small-scale clinical trial comparing CBZ and placebo [19], the prophylactic effects of CBZ were superior in bipolar patients. However, several meta-analyses were unable to reach a conclusion about the efficacy of CBZ in prophylaxis [20-22]. In addition, there are a number of limitations when interpreting previous double-blind, controlled studies [23]. Firstly, most of these studies were based on a small sample size (up to 60 patients). Second, follow-up periods were relatively short (up to 2.5 years). Studies concerned with long-term efficacy tend to be more rigorous when their follow-up periods are longer. Unfortunately, studies that address the above-mentioned limitations are scarce. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the clinical usage and long-term efficacy of CBZ in patients with bipolar I disorder treated with CBZ over an extended period. We reviewed the charts of a sample of 129 patients maintained on long-term CBZ therapy for up to 10 years. This paper describes the demographics, clinical characteristics and outcome data, and analyses the correlates of the outcome.

In a small-scale clinical trial comparing CBZ and placebo [19], the prophylactic effects of CBZ were superior in bipolar patients. However, several meta-analyses were unable to reach a conclusion about the efficacy of CBZ in prophylaxis [20-22]. In addition, there are a number of limitations when interpreting previous double-blind, controlled studies [23]. Firstly, most of these studies were based on a small sample size (up to 60 patients). Second, follow-up periods were relatively short (up to 2.5 years). Studies concerned with long-term efficacy tend to be more rigorous when their follow-up periods are longer. Unfortunately, studies that address the above-mentioned limitations are scarce. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the clinical usage and long-term efficacy of CBZ in patients with bipolar I disorder treated with CBZ over an extended period. We reviewed the charts of a sample of 129 patients maintained on long-term CBZ therapy for up to 10 years. This paper describes the demographics, clinical characteristics and outcome data, and analyses the correlates of the outcome.

Setting and subjects

This was a retrospective chart-review study. Subjects comprised of patients attending the outpatient clinic of the Taipei City Psychiatric Center (TCPC) in Taipei, Taiwan. TCPC is a psychiatric hospital of 600 beds, and is one of the oldest and largest psychiatric hospitals in the Taipei metropolitan area. Most patients attending this hospital were referred from other general hospitals or clinics, and had been regularly followed up on. We included patients with a DSM-IV diagnosis of bipolar I disorder who had been treated at this hospital for at least 1 year with prophylactic CBZ (Tegretal®) either as monotherapy or combined with other mood stabilizers or antipsychotics. Diagnoses were made according to the medical records of the patient, and were usually made by at least two well-trained psychiatrists based on clinical evaluation and observation.

Assessment

The study was based on a mirror-image study design, in which the clinical course under CBZ treatment was compared with data prior to CBZ treatment. The frequency of manic or depressive episodes and the frequency of hospitalization were recorded and analyzed as the main outcomes. We also collected clinically relevant data from the medical records and phone interviews, including demographic data, duration of illness and CBZ use, dosage and plasma concentration, concomitant medications, and reported side effects. The data were obtained by experienced research assistants, and the accuracy of recording was verified by two senior psychiatrists. Patients usually visited the clinic once a month but the frequency was dependent upon their clinical condition. An episode was defined as the recurrence of a full-blown manic or depressive mood event recorded in the chart. Patients who were prescribed with CBZ after their first episode were coded as ‘one episode prior to CBZ treatment’. The serum level of CBZ and other parameters were regularly monitored about twice a year, approximately 12 hours after the last dose of CBZ. Concomitant usage of medications other than CBZ was determined by clinical condition of the patient and was not limited due to the naturalistic nature of this study.

The frequency of manic or depressive episodes and the frequency of hospitalization were recorded and analyzed as the main outcomes. We also collected clinically relevant data from the medical records and phone interviews, including demographic data, duration of illness and CBZ use, dosage and plasma concentration, concomitant medications, and reported side effects. The data were obtained by experienced research assistants, and the accuracy of recording was verified by two senior psychiatrists. Patients usually visited the clinic once a month but the frequency was dependent upon their clinical condition. An episode was defined as the recurrence of a full-blown manic or depressive mood event recorded in the chart. Patients who were prescribed with CBZ after their first episode were coded as ‘one episode prior to CBZ treatment’. The serum level of CBZ and other parameters were regularly monitored about twice a year, approximately 12 hours after the last dose of CBZ. Concomitant usage of medications other than CBZ was determined by clinical condition of the patient and was not limited due to the naturalistic nature of this study. We recorded the medications used at the last visit. We divided the patients into those with complete remission (CR) and those with non-CR, in which they had relapsed episode after CBZ treatment. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the hospital.

We recorded the medications used at the last visit. We divided the patients into those with complete remission (CR) and those with non-CR, in which they had relapsed episode after CBZ treatment. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the hospital.

Data analysis

The clinical variables were analyzed as mean ± SD. Paired t-test was utilized to analyze the changes in affective episodes before and after CBZ use. Independent t-test and Chi-square test were used to clarify correlations between variables and the treatment response.

Characteristics of patients

A total of 129 (45 males) patients were recruited in this study. Table shows the basic demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients. Their ages ranged from 22 to 80 years, but most (84.5%) were between 30 to 60 years old. Forty-four percent were married. Forty-one percent of the patients were in full-time or part-time employment, 23% were housewives, and 26% were unemployed. Most patients were judged to be regular attendees at follow-up and showed good drug compliance. The mean duration of disease course before CBZ treatment was 10.8 ± 7.6 years. Forty-two had started receiving CBZ after their first mood episode and 26 were switched to CBZ after receiving lithium or valproic acid. For the remainder, CBZ was used as an add-on to lithium (n = 45), valproic acid (n = 11), or the both of them (n = 5). Eighty-eight patients (68.2%) were taking low-dose antipsychotics concomitantly. Ninety-six patients (74.4%) needed to use benzodiazepines (mostly for the hypnotic action) concomitantly. CBZ monotherapy (without other mood stabilizer or antipsychotic) was used in 20 patients (15.5%). Among them, 12 patients were in the CR group. The patients’ mean body weight increased from 61.8 ± 13.2 to 66.6 ± 12.8 kg during treatment. The body weight increment was significantly less in patients treated with CBZ than those with combination of lithium, or valproic acid (3.41 ± 8.

Most patients were judged to be regular attendees at follow-up and showed good drug compliance. The mean duration of disease course before CBZ treatment was 10.8 ± 7.6 years. Forty-two had started receiving CBZ after their first mood episode and 26 were switched to CBZ after receiving lithium or valproic acid. For the remainder, CBZ was used as an add-on to lithium (n = 45), valproic acid (n = 11), or the both of them (n = 5). Eighty-eight patients (68.2%) were taking low-dose antipsychotics concomitantly. Ninety-six patients (74.4%) needed to use benzodiazepines (mostly for the hypnotic action) concomitantly. CBZ monotherapy (without other mood stabilizer or antipsychotic) was used in 20 patients (15.5%). Among them, 12 patients were in the CR group. The patients’ mean body weight increased from 61.8 ± 13.2 to 66.6 ± 12.8 kg during treatment. The body weight increment was significantly less in patients treated with CBZ than those with combination of lithium, or valproic acid (3.41 ± 8. 81 vs. 7.23 ± 10.60 kg, mean difference = −3.83, 95% CI = −7.64 to −0.01, p = 0.050), regardless of any combined use of antipsychotics. The mean number of admissions before and after CBZ was 2.26 ± 2.25 and 1.19 ± 1.80, respectively. After CBZ treatment, almost half of the patients (n = 63, 48.8%) had no further mood episodes during the follow-up period. Others (n = 66, 51.2%) suffered from varying frequencies of relapses ranging from 1 to 15 relapses.

81 vs. 7.23 ± 10.60 kg, mean difference = −3.83, 95% CI = −7.64 to −0.01, p = 0.050), regardless of any combined use of antipsychotics. The mean number of admissions before and after CBZ was 2.26 ± 2.25 and 1.19 ± 1.80, respectively. After CBZ treatment, almost half of the patients (n = 63, 48.8%) had no further mood episodes during the follow-up period. Others (n = 66, 51.2%) suffered from varying frequencies of relapses ranging from 1 to 15 relapses.

Table 1

Clinical characteristics of study subjects (n = 129)

| Clinical characteristicsM | Mean ± SD |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | 45.7 ± 10.9 |

| Age of onset (years) | 24. 6 ± 9.5 6 ± 9.5 |

| Education (years) | 11.8 ± 3.3 |

| Latency to CBZ treatment (Years) | 10.8 ± 7.6 |

| Follow-up period after CBZ treatment (Years) | 10.4 ± 5.2 |

| Current CBZ dose (mg) | 571.3 ± 212.6 |

| Current CBZ plasma level (μg/mL) | 7.8 ± 5.9 |

| Mood episodes before CBZ treatment | N (%) |

| 1 | 42 (32. 6) 6) |

| 2 | 22 (17.1) |

| 3 | 28 (21.7) |

| 4 | 16 (12.4) |

| ≧5 | 21 (16.3) |

| Mood episodes after CBZ treatment | N (%) |

| 0 | 63 (48.8) |

| 1 | 21 (16. 3) 3) |

| 2 | 22 (17.1) |

| 3 | 6 (4.7) |

| ≧4 | 17 (13.2) |

Open in a separate window

CBZ carbamazepine.

Effectiveness of CBZ

Table shows the mean frequency (times per year) of hospitalization and mood episode pre- and post-CBZ treatment. Compared to the pre-CBZ treatment period, the post-CBZ period showed significantly fewer hospital admissions per year (p < 0.001), and fewer mood episodes per year (p = 0.002).

Table 2

Frequency (Mean ± SD times/year) and mean difference of hospitalization and mood episode before and after carbamazepine (CBZ) treatment

| Before CBZ | After CBZ | Mean difference (95%CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hospitalization frequency | 0. 33 ± 0.46 33 ± 0.46 | 0.14 ± 0.30 | 0.18 (0.09, 0.27) | <0.001 |

| Episode frequency | 0.63 ± 1.70 | 0.16 ± 0.30 | 0.47 (0.17, 0.77) | 0.002 |

Open in a separate window

SD standard deviation, CI confidence interval.

Variables correlated with treatment response

We also delineated the correlates and characteristics of a good or poor response. Using our definition of CR and non-CR according to whether they had relapsed after CBZ treatment, 63 patients were placed in the CR group and 66 patients in the non-CR group. These two groups were then compared with respect to demographics and clinically-related variables. Data on the variables are presented in Table . The CR patients had a shorter follow-up duration after CBZ treatment (p = 0.046), a trend of fewer mood episodes before CBZ treatment (p = 0.054), and a higher likelihood of being male (p = 0.026).

Data on the variables are presented in Table . The CR patients had a shorter follow-up duration after CBZ treatment (p = 0.046), a trend of fewer mood episodes before CBZ treatment (p = 0.054), and a higher likelihood of being male (p = 0.026).

Table 3

Comparison of clinical variables between subjects with/without complete remission (CR) by mean difference and relative risk (RR)

| Variables | CR (n = 63) | without CR (n = 66) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value |

| Latency to CBZ treatment (yrs) | 11. 86 ± 8.07 86 ± 8.07 | 9.70 ± 6.96 | 2.16 (−0.47, 4.78) | 0.106 |

| Period after CBZ treatment (yrs) | 9.49 ± 5.04 | 11.31 ± 5.23 | −1.82 (−3.61, −0.03) | 0.046 |

| Episode before treatment | 2.57 ± 2.13 | 3.32 ± 2.23 | −0.75 (−1. 51, 0.01) 51, 0.01) | 0.054 |

| Episode after treatment | 0 | 2.65 ± 1.86 | −2.65 (−3.11, −2.19) | <0.001 |

| Drug dose (mg) | 539.68 ± 187.98 | 601.52 ± 231.05 | −61.83 (−135.42, 11.75) | 0.099 |

| Drug level (μg/mL) | 7. 22 ± 1.94 22 ± 1.94 | 8.38 ± 8.03 | −1.15 (−3.26, 0.95) | 0.280 |

| Age (yrs) | 46.99 ± 11.17 | 44.55 ± 10.58 | 2.44 (−1.35, 6.23) | 0.205 |

| | N (%) | N (%) | RR (95% CI) | P value |

| Gender (female) | 35 (55. 6) 6) | 49 (74.2) | 0.75 (0.58, 0.97) | 0.026 |

| Tobacco use | 9 (14.5) | 15 (22.7) | 1.11 (0.94, 1.31) | 0.234 |

| Alcohol use n | 5 (8.1) | 5 (7.6) | 1.00 (0.90, 1.10) | 0918 |

| Combined use of antipsychotics | 36 (57. 1) 1) | 52 (78.8) | 2.02 (1.17, 3.49) | 0.008 |

| Combined use of BZD n | 45 (71.4) | 51 (77.3) | 1.26 (0.70, 2.27) | 0.447 |

| Combined use of lithium | 24 (38.1) | 26 (39.4) | 1.02 (0.78, 1.34) | 0. 880 880 |

| Combined use of valproic acid | 10 (15.9) | 6 (9.1) | 0.93 (0.81, 1.06) | 0.243 |

| Combined use of antidepressant | 6 (9.5) | 8 (12.1) | 1.03 (0.91, 1.16) | 0.635 |

Open in a separate window

CBZ carbamazepine, SD standard deviation, CI confidence interval, BZD benzodiazepine.

The most common side effects recorded on the chart were related to the central nervous system (24%), such as dizziness, ataxia, and cognitive impairment. Other common side effects were gastrointestinal disturbance (3.6%), tremor (3.6%), skin rash (2.9%), and blurred vision (2.9%).

Other common side effects were gastrointestinal disturbance (3.6%), tremor (3.6%), skin rash (2.9%), and blurred vision (2.9%).

To our knowledge, this is the longest outcome study that addresses the long-term use of CBZ in bipolar patients. We collected data from 129 patients exhibiting good compliance and attendance, which implies a reasonable quality of data. We used chart review to minimize the effect of recall bias, and all patients were evaluated by experienced clinicians. It is also worth noting that the long follow-up period (mean duration of 10 years) in this study could provide information that other studies lack. Mean plasma level of patients was 7.8 ± 5.9 μg/mL, which was within suggested therapeutic range for maintenance therapy.

We found that the frequency of mood episodes and hospitalization decreased significantly after CBZ treatment. We were also surprised to find that almost half of the patients (48.8%) had no more mood episodes after CBZ treatment, showing the efficacy of CBZ, either as monotherapy or combined with other mood stabilizers or antipsychotics, in the prophylactic treatment of bipolar disorder. It is difficult to compare our findings with other studies since there has been no other 10-year naturalistic follow-up of bipolar disorder patients treated with CBZ. The response rates for CBZ in previous studies varied. Kleindienst and Greil [24] found that classical bipolar patients treated with CBZ had a hospitalization rate of about 62% versus 26% in those treated with lithium in a randomized clinical trial with an observation period of 2.5 years. The better remission rate in our study might be related to the naturalistic design of the study, which allowed for a combination of other medications during the study period.

It is difficult to compare our findings with other studies since there has been no other 10-year naturalistic follow-up of bipolar disorder patients treated with CBZ. The response rates for CBZ in previous studies varied. Kleindienst and Greil [24] found that classical bipolar patients treated with CBZ had a hospitalization rate of about 62% versus 26% in those treated with lithium in a randomized clinical trial with an observation period of 2.5 years. The better remission rate in our study might be related to the naturalistic design of the study, which allowed for a combination of other medications during the study period.

A second aim of our study was to determine the correlates of the CBZ prophylactic response. In previous studies, CBZ response was related to “non-classical disease”, and patients with suicidal behavior, lithium-refractory disease, and mixed episodes. However, in our study, no specific factors were correlated with the response to CBZ treatment with the exception that males had a better response rate. Since it was impossible to attain some of the clinical variables in this retrospective review, the response may be correlated with other factors that were not considered in this study.

Since it was impossible to attain some of the clinical variables in this retrospective review, the response may be correlated with other factors that were not considered in this study.

The adverse events reported by the patients were also reviewed. The most common side effects coded were dizziness, fatigue and somnolence (24%). Most patients in our study were able to tolerate the side effects of long-term use of CBZ. Patients who did not receive concomitant lithium or valproic acid had significantly less body weight increment. This result confirms previous reports [14,21] suggesting that one benefit of CBZ include the low propensity toward weight gain and evidence of good tolerability with long-term treatment.

It is worth noting that about 40% of patients were treated concomitantly with lithium or valproic acid. Most patients needed benzodiazepines (74.4%) and antipsychotics (68.2%) in maintenance therapy. Given the naturalistic study design, we were unable to control the adjuvant medication. However, adjuvant medication usage did not differ between our CR and non-CR groups. In a review article by Keck and McElroy [25], the authors suggested that combination therapy may provide better long-term prevention of illness relapse and recurrence in many patients with bipolar disorder.

However, adjuvant medication usage did not differ between our CR and non-CR groups. In a review article by Keck and McElroy [25], the authors suggested that combination therapy may provide better long-term prevention of illness relapse and recurrence in many patients with bipolar disorder.

The main limitation of this study was the potential for a confounding bias due to its observational design. Since this study was designed as a retrospective chart review, it did not include patients who were initially treated with CBZ but discontinued use later for any reason. It was difficult to estimate the percentage of patients who dropped out of initial CBZ treatment, so the results should be interpreted with caution, and may only reflect the prophylactic effect in those who initially responded to acute treatment with CBZ. It is likely that patients who did not respond well to CBZ or who did not tolerate CBZ were more likely to drop out. In a 6-month, multicenter, open-label evaluation of beaded, extended-release CBZ capsule monotherapy in bipolar disorder patients with manic or mixed episodes [26], 68. 8% of patients discontinued treatment early due to the lack of efficacy or side effects. This result reflects the fact that only a portion of patients adhere to CBZ according to perceived efficacy or tolerability of side effects. Our study merely showed that if a patient had a fair response to CBZ, they were likely to respond well in the continuing follow-up period. As mentioned earlier, due to the naturalistic setting, medications were not controlled during relapse. In addition, some variables were not reviewed (e.g., rapid cycling, or type of mood episode), which limited further analysis of clinical outcomes. Patients who were prescribed with CBZ during their first episode were coded as ‘zero episode prior to CBZ treatment’, which included 42 of the subjects. It is possible that patients with bipolar disorder who had just one episode over a long period of time may have a milder bipolar illness. However, after excluding these 42 subjects from analysis, the results remained the same (data not shown).

8% of patients discontinued treatment early due to the lack of efficacy or side effects. This result reflects the fact that only a portion of patients adhere to CBZ according to perceived efficacy or tolerability of side effects. Our study merely showed that if a patient had a fair response to CBZ, they were likely to respond well in the continuing follow-up period. As mentioned earlier, due to the naturalistic setting, medications were not controlled during relapse. In addition, some variables were not reviewed (e.g., rapid cycling, or type of mood episode), which limited further analysis of clinical outcomes. Patients who were prescribed with CBZ during their first episode were coded as ‘zero episode prior to CBZ treatment’, which included 42 of the subjects. It is possible that patients with bipolar disorder who had just one episode over a long period of time may have a milder bipolar illness. However, after excluding these 42 subjects from analysis, the results remained the same (data not shown).

As demonstrated, our longitudinal study proved that CBZ is efficacious and tolerable in the maintenance therapy of bipolar disorder in naturalistic clinical practice, either as monotherapy or in combination with other medications. Patients who have a good response to CBZ tend to continue to do well over the long term and their subsequent course of illness appears to be improved compared to their course of illness prior to CBZ treatment. This should be validated by more controlled long-term follow-up studies.

The authors declare that they have no financial or other conflicts of interests in relation to this manuscript.

CHC and SKL designed the study, collected the data, and co-wrote the paper. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/12/47/prepub

This study was supported by NSC 95-2314-B-532-009-MY3 and partly by TPRN; PH-098-SP-11. The authors thank Mr. Yan-Lung Chui for his assistance in the statistical analysis.

Yan-Lung Chui for his assistance in the statistical analysis.

- Muller-Oerlinghausen B, Berghofer A, Bauer M. Bipolar disorder. Lancet. 2002;359(9302):241–247. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07450-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin MJ, Swendsen J, Heller TL, Hammen C. Relapse and impairment in bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152(11):1635–1640. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thase ME. Maintenance therapy for bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(11):e32. doi: 10.4088/JCP.1108e32. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Emrich HM, Dose M, von Zerssen ZD. The use of sodium valproate, carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine in patients with affective disorders. J Affect Disord. 1985;8(3):243–250. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(85)90022-9. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Peselow ED, Fieve RR, Difiglia C, Sanfilipo MP. Lithium prophylaxis of bipolar illness. The value of combination treatment. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164(2):208–214. doi: 10.1192/bjp.

164.2.208. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

164.2.208. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Ballenger JC, Post RM. Therapeutic effects of carbamazepine in affective illness: a preliminary report. Commun Psychopharmacol. 1978;2(2):159–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okuma T, Kishimoto A, Inoue K, Matsumoto H, Ogura A. Anti-manic and prophylactic effects of carbamazepine (Tegretol) on manic depressive psychosis. A preliminary report. Folia Psychiatr Neurol Jpn. 1973;27(4):283–297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballenger JC, Post RM. Carbamazepine in manic-depressive illness: a new treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 1980;137(7):782–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenzi A, Lazzerini F, Grossi E, Massimetti G, Placidi GF. Use of carbamazepine in acute psychosis: a controlled study. J Int Med Res. 1986;14(2):78–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerer B, Moore N, Meyendorff E, Cho SR, Gershon S. Carbamazepine versus lithium in mania: a double-blind study. J Clin Psychiatry. 1987;48(3):89–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YY, Deng HC, Wang BH.

The increasing use of anticonvulsants in prophylactic treatment of bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;52(4):429–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.1998.00405.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

The increasing use of anticonvulsants in prophylactic treatment of bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;52(4):429–431. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1819.1998.00405.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Weisler RH, Keck PE, Swann AC, Cutler AJ, Ketter TA, Kalali AH. Extended-release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy for acute mania in bipolar disorder: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(3):323–330. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v66n0308. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Weisler RH, Kalali AH, Ketter TA. A multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of extended-release carbamazepine capsules as monotherapy for bipolar disorder patients with manic or mixed episodes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(4):478–484. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v65n0405. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Coxhead N, Silverstone T, Cookson J. Carbamazepine versus lithium in the prophylaxis of bipolar affective disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand.

1992;85(2):114–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb01453.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1992;85(2):114–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1992.tb01453.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Denicoff KD, Smith-Jackson EE, Disney ER, Ali SO, Leverich GS, Post RM. Comparative prophylactic efficacy of lithium, carbamazepine, and the combination in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 1997;58(11):470–478. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v58n1102. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Garnham J, Munro A, Slaney C, Macdougall M, Passmore M, Duffy A. et al. Prophylactic treatment response in bipolar disorder: results of a naturalistic observation study. J Affect Disord. 2007;104(1–3):185–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greil W, Kleindienst N. The comparative prophylactic efficacy of lithium and carbamazepine in patients with bipolar I disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14(5):277–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small JG, Klapper MH, Milstein V, Kellams JJ, Miller MJ, Marhenke JD. et al. Carbamazepine compared with lithium in the treatment of mania. Arch Gen Psychiatry.

1991;48(10):915–921. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810340047006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1991;48(10):915–921. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1991.01810340047006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar] - Okuma T, Inanaga K, Otsuki S, Sarai K, Takahashi R, Hazama H. et al. A preliminary double-blind study on the efficacy of carbamazepine in prophylaxis of manic-depressive illness. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1981;73(1):95–96. doi: 10.1007/BF00431111. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Dardennes R, Even C, Bange F, Heim A. Comparison of carbamazepine and lithium in the prophylaxis of bipolar disorders. A meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 1995;166(3):378–381. doi: 10.1192/bjp.166.3.378. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

- Akiskal HS, Fuller MA, Hirschfeld RM, Keck PE, Ketter TA, Weisler RH. Reassessing carbamazepine in the treatment of bipolar disorder: clinical implications of new data. CNS Spectr. 2005;10(6):suppl-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden CL. Anticonvulsants in bipolar disorders: current research and practice and future directions. Bipolar Disord.

2009;11(Suppl 2):20–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2009;11(Suppl 2):20–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar] - Calabrese JR, Rapport DJ, Shelton MD, Kimmel SE. Evolving methodologies in bipolar disorder maintenance research. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 2001;41:s157–s163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst N, Greil W. Differential efficacy of lithium and carbamazepine in the prophylaxis of bipolar disorder: results of the MAP study. Neuropsychobiology. 2000;42(Suppl 1):2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keck PE, McElroy SL. Carbamazepine and valproate in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(Suppl 10):13–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketter TA, Kalali AH, Weisler RH. A 6-month, multicenter, open-label evaluation of beaded, extended-release carbamazepine capsule monotherapy in bipolar disorder patients with manic or mixed episodes. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(5):668–673. doi: 10.4088/JCP.v65n0511. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Articles from BMC Psychiatry are provided here courtesy of BioMed Central

Co-administration of carbamazepine and lithium in the treatment of outpatients with fast cycling bipolar disorder without psychiatric comorbidity: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial | Aliev

1. Blanco C, Compton WM, Saha TD, Goldstein BI, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Grant BF. Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017;84:310–317. PMID: 27814503 PMCID: PMC7416534 DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.10.003

Blanco C, Compton WM, Saha TD, Goldstein BI, Ruan WJ, Huang B, Grant BF. Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2017;84:310–317. PMID: 27814503 PMCID: PMC7416534 DOI: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2016.10.003

2. Cloutier M, Greene M, Guerin A, Touya M, Wu E. The economic burden of bipolar I disorder in the United States in 2015. J. Affect. Disorder. 2018;226:45–51. PMID: 28961441 DOI: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.09.011

3. Maj M, Pirozzi R, Magliano L, Bartoli L. The long-term result of lithium proaxis in bipolar disorder: a 5-year prospective study of 402 patients in a lithium clinic. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1998;155:30–35. PMID: 9433335 DOI: 10.1176/ajp.155.1.30

4. Fountoulakis KN, Kontis D, Gonda X, Yatham LN. A systematic review of the evidence on the treatment of rapid cycling bipolar disorder. 2013;15:115–137. PMID: 23437958 DOI: 10.1111/bdi.12045

5. Carvalho AF, Dimellis D, Gonda X, Vieta E, Mclntyre RS, Fountoulakis KN. Rapid cycling in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J.Clin. Psychiatry. 2014;75:e578–586. PMID: 25004199 DOI: 10.4088/JCP.13r08905

J.Clin. Psychiatry. 2014;75:e578–586. PMID: 25004199 DOI: 10.4088/JCP.13r08905

6. Goldberg JF, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Ketter TA, Dann RS, Frye MA, Suppes T, Post RM. Six-month prospective life charting of mood symptoms with lamotrigine monotherapy versus placebo in rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;63:125–130. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.031

7. Aditya H, Aditi S, Malvika R, Janardhanan CN, Suresh BM. Pramipexole in the treatment of refractory depression in a patient with rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2015;37:473–474. PMCID: PMC4676223 PMID: 26702189 DOI: 10.4103/0253-7176.168614

8. Chen P, Huang Y. Remission of classic rapid cycling bipolar disorder with levothyroxine augmentation therapy in a male patient having clinical hypothyroidism. Neuropsychiatr Dis. treat. 2015;11:339–342. DOI: 102147/NDT.S76973

9. Viguera AC, Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L. Response to lithium maintenance treatment in bipolar disorders: comparison of women and men. Bipolar Discord. 2001;3:245–252. PMID: 11903207 DOI: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.30503.x

Bipolar Discord. 2001;3:245–252. PMID: 11903207 DOI: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2001.30503.x

10. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

11. Glantz SA. Primer of Biostatistics. Seventh Edition. 2012:321. ISBN-13: 978-0071781503; ISBN-10: 0071781501

12. Huber J, Burke D. ECT and lithium in old age depression—cause or treatment of rapid cycling? Australas Psychiatry. 2015;23:500–502. PubMed DOI: 10.1177/1039856215591328

13. Maj M, Pirozzi R, Formacola AMR, Tortrella A. Reliability and validity of four alternative definitions of bipolar disorder with fast cycling. Am. J. Psychiatry. 1999;158:303–305. PMID: 10484955. DOI: 10.1176/ajp.156.9.1421

14. Sampath H, Sharma I, Dutta S. Treatment of suicidal depression with ketamine in rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Asia Pack. Psychiatry. 2016;8:98–101. PMID: 26871425 DOI: 10.1111/appy.12220

15. Goldberg JF, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Ketter TA, Dann RS, Frye MA, Suppes T, Post RM. Six-month prospective life charting of mood symptoms with lamotrigine monotherapy versus placebo in rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;63:125–130. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.031

Goldberg JF, Bowden CL, Calabrese JR, Ketter TA, Dann RS, Frye MA, Suppes T, Post RM. Six-month prospective life charting of mood symptoms with lamotrigine monotherapy versus placebo in rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2008;63:125–130. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.12.031

16. Bobo WV, Vande Voort JL, Croarkin PE, Leung JG, Tye SJ, Frye MA. Ketamine for treatment-resistant unipolar and bipolar major depression: critical review and implications for clinical practice. Depress Anxiety. 2016;33(8):698–710. DOI: 10.1002/da.22505. Epub 2016 Apr 6. PMID: 27062450

17. Calabrese JR, Fatemi SH, Kujawa M, Woyshville MJ. Predictors of response to mood stabilizers. J.Clin. Psychopharmacol. 1996;16:24–31. PMID: 8707997 DOI: 10.1097/00004714-199604001-00004

18. Baldessarini RJ, Tondo L, Hennen J, Viguera AC. Is Lithium Still Worth Using? An Update of Selected Recent Research. Harvard Review of Psychiatry. 2002; 10(2):59–75. DOI: 10.1080/hrp.10.2.59.75

19. Calabrese JR, Shelton MD, Rapport DJ, Youngstrom EA, Jackson K, Bilali S, Ganocy SJ, Findling RL. A 20-month, double-blind, maintenance trial of lithium versus divalproex in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162:2152–2161. PMID: 16263857. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2152

Calabrese JR, Shelton MD, Rapport DJ, Youngstrom EA, Jackson K, Bilali S, Ganocy SJ, Findling RL. A 20-month, double-blind, maintenance trial of lithium versus divalproex in rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2005;162:2152–2161. PMID: 16263857. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.11.2152

20. Koukopoulos A, Reginalsi D, Laddomada P, Floris G, Serra G, Tondo L. Course of the manic-depressive cycle and changes caused by treatments. Pharmacopsychiatry. 1980;13:156–167. PMID: 6108577. DOI: 10.1055/s-2007-1019628

21. Health at a Glance: Europe 2018. State of Health in the EU Cycle. OECD Publishing. 2018:216.

22. Calabrese JR, Rapport DJ, Youngstrom EA, Jackson K, Bilali S, Findling RL. New data on the use of lithium, divalproate, and lamotrigine in rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Eur. Psychiatry. 2005;20(2):92–95. PMID: 15797691 DOI: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2004.12.003

23. Kostyukova EG, Shafarenko AA, Ladyzhensky MY. Problems and new possibilities of differentiated therapy in patients with bipolar disorder. Modern therapy of mental disorders. 2014;4:8–14.

Modern therapy of mental disorders. 2014;4:8–14.

Current evidence for the efficacy of carbamazepine in psychiatric disorders

Introduction

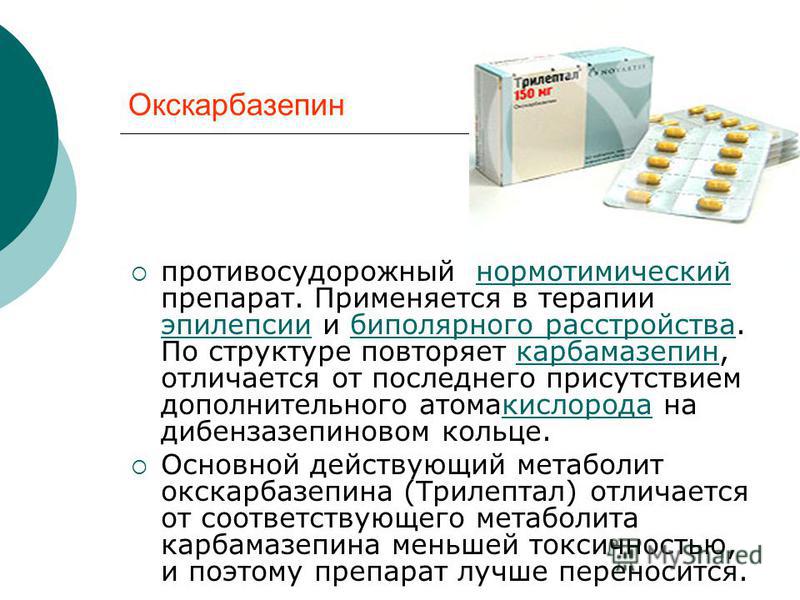

Carbamazepine has been used in psychiatric practice since the mid-1960s. The drug is indicated for the treatment of epilepsy and seizures: partial seizures with complex symptoms (psychomotor, temporal), generalized tonic-clonic seizures (grand mal) [1]; in the USA and Europe, carbamazepine is considered the first choice for the treatment of patients with partial seizures [2]. nine0003

The antimanic properties of carbamazepine were first reported by Japanese authors Takezaki and Hanaoka [3] in 1971. Reports on the results of randomized clinical trials of carbamazepine in bipolar disorder appeared only in the 1980s [4]. The results of clinical trials of the drug in the treatment of depression and as maintenance therapy for bipolar disorder have been heterogeneous [5-8].

Anticonvulsants, including carbamazepine, along with benzodiazepines, are indicated and widely used in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome [9].

The drug was also prescribed for a number of other mental disorders, including mental disorders that were not indicated in the drug instructions as indications for use, for example, for schizophrenia and anxiety disorders [1]. Carbamazepine was prescribed both alone and in combination with other psychotropic drugs.

With the advent of new anticonvulsants and atypical antipsychotics, clinicians expect these agents to be more effective and safe [4], but do clinical trials and meta-analyses confirm these expectations? nine0003

The purpose of this publication is to review the current evidence for the efficacy of carbamazepine in the treatment of psychiatric disorders.

Method

To search for current evidence of the efficacy of carbamazepine in psychiatric practice, we turned to the systematic reviews of the Cochran Collaboration, which analyzed and summarized the results of studies and clinical trials of carbamazepine. The keywords "carbamazepine" and "intervention" identified 132 systematic reviews published between 2001 and 2010. For this review, 17 of them were selected that looked at the results of studies of carbamazepine in the treatment of epilepsy and seizures, bipolar disorder, disorders caused by substance use, schizophrenia and personality disorders. nine0003

Results

Epilepsy and convulsions

Systematic reviews compared the use of carbamazepine and other drugs for the monotherapy of epilepsy, the use of anticonvulsants for the treatment of epilepsy in people with mental retardation, and for the prevention of seizures in patients in the acute period of a traumatic brain injury and after a stroke.

In a systematic review of four trials of carbamazepine and phenobarbitone monotherapy for epilepsy, Tudur C. Smith et al. [10] showed that the results of treatment of tonic-clonic seizures were best for carbamazepine, and for partial ones - for phenobarbitone. But the latter drug was worse tolerated by patients, and it has become less commonly used in clinical practice. nine0003

Comparison of carbamazepine and phenytoin in nine clinical trials by Tudur C. Smith et al. [11] showed that both drugs did not differ from each other in many methods of evaluating treatment outcomes, although the wide width of the confidence intervals did not allow us to exclude the existence of differences between the two drugs.

Comparison of epilepsy monotherapy with carbamazepine and valproic acid A.G. Marson et al. [12] did not reveal significant differences between drugs, the results of five trials (1265 participants) indicated the rationale for the practice of using carbamazepine as the first choice drug for partial seizures and insufficient evidence to support the use of valproic acid in generalized epilepsy, although the latter conclusion cannot be considered conclusive. due to the lack of data on the diagnosis of generalized epilepsy in patients in the reviewed trials. nine0003

Systematic review of five randomized trials (1384 participants) C.L. Gamble et al. [13] showed that patients with partial and generalized seizures were significantly better taking lamotrigine, but results such as time to first seizure after randomization and absence of seizures for six months, i. e. better seizure control were better with carbamazepine, although these differences did not reach statistical significance. The authors also noted that the trials analyzed were short, did not compare psychosocial treatment outcomes, and did not allow long-term comparison of the two drugs. nine0003

Systematic review by J. Beavis et al. [14] is devoted to the use of anticonvulsants in the treatment of epilepsy in people with mental retardation. The authors indicated that the results of evaluating the effectiveness of anticonvulsants in the treatment of epilepsy in this group of individuals coincide with those in the general population. The authors were unable to formulate recommendations for individual drugs.

Two systematic reviews analyzed the use of anticonvulsants for the prevention of seizures in patients in the acute period of traumatic brain injury (G. Schierhout, I. Roberts, 2001) [15] and after a stroke (J. Kwan, E. Wood, 2010) [16] . Both reviews were unable to find evidence that anticonvulsants are effective in preventing seizures in the long term. nine0003

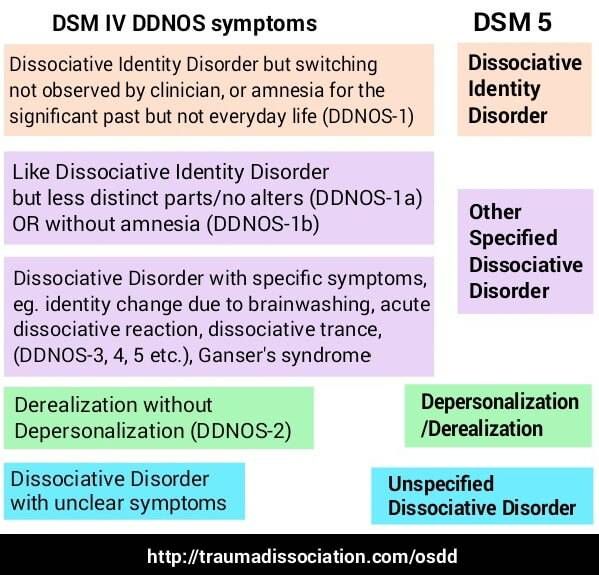

Bipolar disorder

Among the selected systematic reviews, two compared the use of haloperidol and valproic acid with other drugs in the treatment of acute mania, and one compared the use of anticonvulsants for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder.

A systematic review by A. Cipriani et al. [17] has mainly focused on the antimanic properties of haloperidol. It shows that haloperidol is comparable in these properties to lithium, risperidone, olanzapine, carbamazepine, and valproic acid. Similarly, the use of valproic acid in the treatment of acute mania was reviewed in a systematic review by K. Macritchie et al. [eighteen]. Two clinical trials (59participants) valproic acid and carbamazepine were equally effective.

A systematic review of studies on the use of anticonvulsants for the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder K. Macritchie et al. [19] found no evidence of the effectiveness of prescribing carbamazepine as a maintenance treatment.

Substance use disorders

Carbamazepine has been reviewed in three systematic reviews for the treatment of substance use disorders. Two of them analyzed attempts to use the drug in the treatment of cocaine addiction and one - alcohol withdrawal syndrome. nine0003

Interest in studying the use of psychotropic drugs in cocaine addiction is due to the fact that, unlike alcohol or opium addiction, there are currently no agreed pharmacological treatment regimens for this addiction. Anticonvulsants are considered as candidates for the treatment of cocaine addiction. Unfortunately, two Cochrane reviews failed to show positive results of the effective use of anticonvulsants in the treatment of cocaine addiction [20, 21]. nine0003

Systematic review of studies on the use of anticonvulsants for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome S. Minozzi et al. [9] showed that, despite the widespread use of anticonvulsants in this disorder, the effectiveness of most of them is not supported by evidence obtained in double-blind randomized trials, with the exception of carbamazepine. The effectiveness of the use of carbamazepine in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome was considered only in one systematic review of the Cochran Collaboration, which noted that more positive results were obtained with carbamazepine than with other anticonvulsants [9]. This conclusion is supported by other systematic reviews besides the Cochran Collaboration database. A systematic review by D. Williams and A. McBride [30] concluded that carbamazepine may be an alternative to first-line benzodiazepines, as it is effective for a wide range of withdrawal symptoms and is not contraindicated in liver failure. Another two meta-analyses [31, 32] concluded that the efficacy of carbamazepine in reducing mild to moderate withdrawal symptoms is comparable to that of low-dose oxazepam for 7 days. The data from these reviews are included in the British Association for Psychopharmacology Guidelines for the Treatment of Substance Use Disorders [33], which recommend the use of carbamazepine alone in some cases of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, as this practice is not common in the UK and benzodiazepines are used exclusively in the treatment.

nine0003

The results of a recent cohort study comparing the use of carbamazepine and valproic acid in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, conducted in Germany, indicate the need for further prospective studies and clinical trials of carbamazepine in the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, since the drug is widely used in clinical practice, despite insufficient evidence, allowing to formulate final recommendations [34]. nine0003

Schizophrenia

Carbamazepine has been proposed as an adjunct in the treatment of schizophrenia. S. Leucht et al. [22] analyzed the results of clinical trials that compared the effectiveness of carbamazepine and antipsychotics in the treatment of patients with schizophrenia, both as an independent and additional agent. Few such trials have been conducted, and they have all been small. When compared with placebo, carbamazepine did not show efficacy as an independent agent. Only two trials reported that when taking carbamazepine with an antipsychotic, half of the participants experienced an overall improvement (50% reduction in BPRS scores). Taking this into account, the authors did not recommend the routine use of antipsychotics with carbamazepine in the treatment of schizophrenia. nine0003

Personality disorders, aggression and impulsivity

In personality disorders, attempts have been made to use various psychopharmacological agents primarily to control behavioral and impulsive symptoms. Drug labels do not usually contain indications for use in personality disorders, but prescribing anticonvulsants for personality disorders is common in clinical practice, and clinical trials have investigated the efficacy of such prescribing. A systematic review of the use of pharmacological interventions in borderline personality disorder J. Stoffers et al. [23] summarized a large number of clinical trials, but as for individual drugs, these were single and small studies. Thus, in one trial, which included 20 participants, carbamazepine did not show significant differences from placebo [24, 25]. nine0003

Here, we will review the evidence for the effectiveness of anticonvulsant use in managing aggressive behavior and impulsivity, although these phenomena are not symptoms of specific mental disorders, but positive research results relate to the use of anticonvulsants specifically for personality disorders.

A systematic review of fourteen anticonvulsant trials by N. Huband et al. [26] showed that four anticonvulsants (valproic acid, carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, and phenytoin) were effective in reducing aggressive behavior and auto-aggression, in particular, carbamazepine (at a dose of 820 mg/day) was superior to placebo in reducing auto-aggression in women with borderline personality disorder. , but in children with behavioral disorders, the drug was not statistically different from placebo. nine0003

Analysis of six randomized controlled trials of pharmacological interventions for the management of aggression in patients after traumatic brain injury in a systematic review by S. Fleminger et al. [27] pointed to more evidence for beta-blockers and insufficient evidence for the use of anticonvulsants.

Discussion

In this paper, we accessed the database of systematic reviews by the Cochran Collaboration. The reviews of this group are a recognized source of unbiased evidence on various issues of medical practice [28]. nine0003

The evidence reviewed for the use of carbamazepine in epilepsy supports the use of carbamazepine as the first choice drug for partial seizures, its effectiveness is comparable to newer anticonvulsants.

Currently, the effectiveness of many drugs of various pharmacological groups has been proven in the treatment of acute mania. The anti-manic properties of carbamazepine, although it belongs to the second-line treatment of acute mania, are not questioned, while the presence of an anti-manic effect in some atypical antipsychotics continues to be discussed among researchers [29]. With regard to the treatment of alcohol withdrawal syndrome, more positive results have been obtained for carbamazepine than for other anticonvulsants. This allowed the authors of the study to recommend "the use of carbamazepine in first-line treatment regimens for some aspects of alcohol withdrawal syndrome" [9].

In our study of the latest evidence for the effectiveness of carbamazepine, we primarily focused on the evidence for the effectiveness of treatment with the drug; the analysis of side effects, tolerability and safety was not the focus of our attention, therefore, applying the recommendations of the considered systematic reviews in practice, one should take into account the safety problems of taking the drug. nine0003

Despite the fact that we reviewed recent systematic reviews, the authors of these reviews noted that many clinical trials of carbamazepine were conducted relatively long ago and in small groups of patients, therefore, not all conclusions in systematic reviews are considered as final. This applies equally to both positive and negative results of the effectiveness study.

Terminals

Evidence from systematic reviews by the Cochran Collaboration supports the use of carbamazepine as a first-choice monotherapy for epilepsy with partial seizures, a second-line treatment for acute mania, and for the treatment of alcohol withdrawal. nine0003

Bibliography

1. Lexi-Comp: Carbamazepine // The Merck Manual Professional. Last full review/revision January 2010. http://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/lexicomp/carbamazepine.html

2. Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. Diagnosis and management of epilepsy in adults. — 1997: http://pc47.cee.hw.ac.uk/sign/html/html21.

3. Takezaki H., Hanaoka M. The use of carbamazepine (Tegretol) in the control of manic-depressive psychosis and other manic-depressive states // Seishin Igaku. - nineteen71. - 13. - 173-83.

4. Hirschowitz J., Kolevzon A., Garakani A. The pharmacological treatment of bipolar disorder: the question of modern advances // Harv. Rev. Psychiatry. — 2010 Oct. - 18 (5). — 266-78.

5. Ballenger J.C., Post R.M. Carba-mazepine in manic depressive illness: a new treatment // Am. J. Psychiatry. - 1980. - 137. - 782-90.

6. Okuma T., Inanaga K., Otsuki S. et al. A preliminary double-blind study on the efficacy of carbamazepine in prophylaxis of manic-depressive illness // Psychopharmacology. - nineteen81.-73.-95-6.

7. Coxhead N., Silverstone T., Cookson J. Carbamazepine versus lithium in the prophylaxis of bipolar affective disorder // Acta Psychiatr. Scand. - 1992. - 85. - 114-8.

8. Simhandl C., Denk E. , Thau K. The comparative efficacy of carbamazepine low and high serum level and lithium carbonate in the prophylaxis of affective disorders // J. Affect Disord. - 1993. - 28. - 221-31.

9. Minozzi S., Amato L., Vecchi S., Davoli M. Anticonvulsants for alcohol withdrawal // Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. - 2010. - Issue 3. Art. No.: CD005064. nine0003

10. Tudur S.M., Marson A.G., Williamson P.R. Carbamazepine versus phenobarbitone monotherapy for epilepsy. — Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. - 2003. - CD001904.

11. Tudur S.M., Marson A.G., Clough H.E., Williamson P.R. Carba-mazepine versus phenytoin monotherapy for epilepsy // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. - 2002. - CD001911.

12. Marson A.G., Williamson P.R., Hutton J.L., Clough H.E., Chadwick D.W. Carbamazepine versus valproate monotherapy for epilepsy // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. - 2003. - CD001030. nine0003

13. Gamble C.L., Williamson P.R., Marson A.G. Lamotrigine versus carba-mazepine monotherapy for epilepsy // Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. — 2006 Jan. - 25 (1): CD001031.

14. Beavis J., Kerr M., Marson A.G., Dojcinov I. Pharmacological interventions for epilepsy in people with intellectual disabilities // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. - 2007. - Issue 3. Art. No.: CD005399.

15. Schierhout G., Roberts I. Antiepileptic drugs for preventing seizures following acute traumatic brain injury // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. - 2001. - Issue 4. Art. No.: CD000173. nine0003

16. Kwan J., Wood E. Antiepileptic drugs for the primary and secondary prevention of seizures after stroke // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. - 2010. - Issue 1. Art. No.: CD005398.

17. Cipriani A., Rendell J.M., Geddes J. Haloperidol alone or in combination for acute mania // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. - 2006. - Issue 3. Art. No.: CD004362.

18. Macritchie K., Geddes J., Scott J., Haslam D.R., Silva de Lima M., Goodwin G. Valproate for acute mood episodes in bipolar disorder // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. - 2003. - Issue 1. Art. No.: CD004052. nine0003

19. Macritchie K., Geddes J., Scott J., Haslam D.R., Goodwin G. Valproic acid, valproate and divalproex in the maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. - 2001. - Issue 3. Art. No.: CD003196.

20. Minozzi S., Amato L., Davoli M., Farrell M., Lima Reisser A.A.R.L., Pani P.P., Silva de Lima M., Soares B., Vecchi S. Anticonvulsants for cocaine dependence // Cochrane Database of Syst . Rev. - 2008. - Issue 2. Art. No.: CD006754.

21. Lima Reisser A.A.R.L., Silva de Lima M., Soares B.G.D.O., Farrell M. Carbamazepine for cocaine dependence // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. — 2009. — Issue 1. Art. No.: CD002023.

22. Leucht S., Kissling W., McGrath J., White P. Carbamazepine for schizophrenia // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. - 2007. - Issue 3. Art. No.: CD001258.

23. Stoffers J., Völlm B.A., Rücker G., Timmer A., Huband N., Lieb K. Pharmacological interventions for borderline personality disorder // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. - 2010. - Issue 6. Art. No.: CD005653.

24. De la Fuente J.M., Lotstra F. A trial of carbamazepine in borderline personality disorder // European Neuropsychopharmacology. - nineteen94. - 4. - 479-86.

25. De la Fuente J.M., Lotstra F. Carbamazepine in borderline personality disorder // European Neuropsychopharmacology. - 1993. - 3. - 350.

26. Huband N., Ferriter M., Nathan R., Jones H. Antiepileptics for aggression and associated impulsivity // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. - 2010. - Issue 2. Art. No.: CD003499.

27. Fleminger S., Greenwood R.R.J., Oliver D.L. Pharmacological management for agitation and aggression in people with acquired brain injury // Cochrane Database of Syst. Rev. - 2006. - Issue 4. Art. No.: CD003299.

28. Mayer D. Essential Evidence-Based Medicine. — 2nd edition. - Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

29. Bourin M., Lambert O., Guitton B. Treatment of acute mania: from clinical trials to recommendations for clinical practice // Human psychopharmacology.