Can lack of sleep cause hallucinations

Severe Sleep Deprivation Causes Hallucinations and a Gradual Progression Toward Psychosis With Increasing Time Awake

1. Bixler E. Sleep and society: an epidemiological perspective. Sleep Med. (2009) 10, S3–6. 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.07.005 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Pilcher JJ, Huffcutt AJ. Effects of sleep deprivation on performance: a meta-analysis. Sleep (1996) 19:318–26. 10.1093/sleep/19.4.318 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Kahn-Greene ET, Killgore DB, Kamimori GH, Balkin TJ, Killgore WD. The effects of sleep deprivation on symptoms of psychopathology in healthy adults. Sleep Med. (2007) 8:215–21. 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.08.007 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Rosen IM, Gimotty PA, Shea JA, Bellini LM. Evolution of sleep quantity, sleep deprivation, mood disturbances, empathy, and burnout among interns. Acad Med. (2006) 81:82–5. 10.1097/00001888-200601000-00020 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Ferguson SA, Kennaway DJ, Baker A, Lamond N, Dawson D. Sleep and circadian rhythms in mining operators: limited evidence of adaptation to night shifts. Appl Ergon. (2012) 43:695–701. 10.1016/j.apergo.2011.11.003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Mitler MM, Miller JC, Lipsitz JJ, Walsh JK, Wylie CD. The sleep of long-haul truck drivers. N E J Med. (1997) 337:755–62. 10.1056/NEJM199709113371106 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. West LJ, Janszen HH, Lester BK, Cornelisoon FS. The psychosis of sleep deprivation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (1962) 96:66–70. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb50101.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Bauer M, Grof P, Rasgon N, Bschor T, Glenn T, Whybrow Peter C. Temporal relation between sleep and mood in patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. (2006) 8:160–7. 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00294.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Benson KL. Sleep in schizophrenia. Sleep Med Clin. (2008) 3:251–60. 10.1016/j.jsmc.2008.01.001 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Heinrichs DW, Carpenter WT. Prospective study of prodromal symptoms in schizophrenic relapse. Am J Psychiatry (1985) 142:371–3. 10.1176/ajp.142.3.371 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Heinrichs DW, Carpenter WT. Prospective study of prodromal symptoms in schizophrenic relapse. Am J Psychiatry (1985) 142:371–3. 10.1176/ajp.142.3.371 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Herz MI, Melville C. Relapse in schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry (1980) 137:801–5. 10.1176/ajp.137.7.801 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Koranyi EK, Lehmann HE. Experimental sleep deprivation in schizophrenic patients. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry (1960) 2:534–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Jackson A, Cavanagh J, Scott J. A systematic review of manic and depressive prodromes. J Affect Dis. (2003) 74:209–17. 10.1016/S0165-0327(02)00266-5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Lunsford-Avery JR, LeBourgeois MK, Gupta T, Mittal VA. Actigraphic-measured sleep disturbance predicts increased positive symptoms in adolescents at ultra high-risk for psychosis: a longitudinal study. Schizophr Res. (2015) 164:15–20. 10.1016/j.schres.2015.03.013 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Barbini B, Bertelli S, Colombo C, Smeraldi E. Sleep loss, a possible factor in augmenting manic episode. Psychiatry Res. (1996) 65:121–5. 10.1016/S0165-1781(96)02909-5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Barbini B, Bertelli S, Colombo C, Smeraldi E. Sleep loss, a possible factor in augmenting manic episode. Psychiatry Res. (1996) 65:121–5. 10.1016/S0165-1781(96)02909-5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Leibenluft E, Albert PS, Rosenthal NE, Wehr TA. Relationship between sleep and mood in patients with rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. (1996) 63:161–8. 10.1016/0165-1781(96)02854-5 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Waters F, Sinclair C, Rock D, Jablensky A, Foster RG, Wulff K. Daily variations in sleep-wake patterns and severity of psychopathology: A pilot study in community-dwelling individuals with chronic schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. (2011) 187:304–6. 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.01.006 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Babkoff H, Sing HC, Thorne DR, Genser SG, Hegge FW. Perceptual distortions and hallucinations reported during the course of sleep deprivation. Percept Mot Skills (1989) 68:787–98. 10.2466/pms.1989.68.3.787 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Koyanagi A, Stickley A. The association between sleep problems and psychotic symptoms in the general population: a global perspective. Sleep (2015) 38:1875–85. 10.5665/sleep.5232 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Koyanagi A, Stickley A. The association between sleep problems and psychotic symptoms in the general population: a global perspective. Sleep (2015) 38:1875–85. 10.5665/sleep.5232 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Reeve S, Sheaves B, Freeman D. The role of sleep dysfunction in the occurrence of delusions and hallucinations: a systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. (2015) 42:96–115. 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.09.001 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Sheaves B, Bebbington PE, Goodwin GM, Harrison PJ, Espie CA, Foster RG, et al.. Insomnia and hallucinations in the general population: findings from the 2000 and 2007 British psychiatric morbidity surveys. Psychiatry Res. (2016) 241:141–6. 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.03.055 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Taylor MJ, Gregory AM, Freeman D, Ronald A. Do sleep disturbances and psychotic-like experiences in adolescence share genetic and environmental influences? J Abnorm Psychol. (2015) 124:674–84. 10.1037/abn0000057 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

(2015) 124:674–84. 10.1037/abn0000057 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Petrovsky N, Ettinger U, Hill A, Frenzel L, Meyhöfer I, Wagner M, et al.. Sleep deprivation disrupts prepulse inhibition and induces psychosis-like symptoms in healthy humans. J Neurosci (2014) 34:9134–40. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0904-14.2014 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Hurdiel R, van Dongen HP, Aron C, McCauley P, Jacolot L, Theunynck D. Sleep restriction and degraded reaction-time performance in Figaro solo sailing races. J Sports Sci (2014) 32:172–4. 10.1080/02640414.2013.815359 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Meyhöfer I, Kumari V, Hill A, Petrovsky N, Ettinger U. Sleep deprivation as an experimental model system for psychosis: effects on smooth pursuit, prosaccades, and antisaccades. J Psychopharmacol. (2016) 31:418–33. 10.1177/0269881116675511 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Song HT, Sun XY, Yang TS, Zhang LY, Yang JL, Bai J. Effects of sleep deprivation on serum cortisol level and mental health in servicemen. Int J Psychophysiol. (2015) 96:169–75. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.04.008 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Effects of sleep deprivation on serum cortisol level and mental health in servicemen. Int J Psychophysiol. (2015) 96:169–75. 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.04.008 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Blom JD. (2010). A Dictionary of Hallucinations. New York, NY: Springer. [Google Scholar]

28. Katz SE, Landis C. Psychologic and physiologic phenomena during a prolonged vigil. Arch Neurol Psychiatry (1935) 34:307–17. 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1935.02250200067006 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Kleitman N. The effects of prolonged sleeplessness on man. Am J Physiol. (1923) 66:67–92. [Google Scholar]

30. Morris GO, Williams HL, Lubin A. Misperception and disorientation during sleep deprivation. AMA Arch Gen Psychiatry (1960) 2:247–54. 10.1001/archpsyc.1960.03590090003002 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Friedman RC, Kornfeld DS, Bigger TJ. Psychological problems associated with sleep deprivation in interns. Acad Med. (1973) 48:436–41. 10.1097/00001888-197305000-00004 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Tyler DB. The effect of amphetamine sulfate and some barbiturates on the fatigue produced by prolonged wakefulness. Am J Physiol. (1947) 150:253–62. 10.1152/ajplegacy.1947.150.2.253 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Tyler DB. The effect of amphetamine sulfate and some barbiturates on the fatigue produced by prolonged wakefulness. Am J Physiol. (1947) 150:253–62. 10.1152/ajplegacy.1947.150.2.253 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Cappon D, Banks R. Preliminary study of endurance and perceptual change in sleep deprivation. Percept Mot Skills (1960) 10:99–104. 10.2466/pms.1960.10.2.99 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Edwards AS. Effects of the loss of one hundred hours of sleep. Am J Psychol. (1941) 54:80–91. 10.2307/1417794 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Berger RJ, Oswald I. Effects of sleep deprivation on behaviour, subsequent sleep, and dreaming. Br J Psychiatry (1962) 108:457–65. 10.1192/bjp.108.455.457 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Malmo RB, Surwillo WW. Sleep deprivation: changes in performance and physiological indicants of activation. Psychol Monogr. (1960) 74:1–24. 10.1037/h0093763 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Bliss EL, Clark LD, West CD. Studies of sleep deprivation-relationship to schizophrenia. AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry (1959) 81:348–59. 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1959.02340150080009 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

AMA Arch Neurol Psychiatry (1959) 81:348–59. 10.1001/archneurpsyc.1959.02340150080009 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Kollar EJ, Slater GR, Palmer JO, Doctor RF, Mandell AJ. Stress in subjects undergoing sleep deprivation. Psychosom Med. (1966) 28:101–13. 10.1097/00006842-196603000-00002 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Luby ED, Grisell JL, Frohman CE, Lees H, Cohen BD, Gottlieb JS. Biochemical, psychological, and behavioral responses to sleep deprivation. Ann N Y Acad Sci. (1962) 96:71–9. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1962.tb50102.x [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

40. Anderson LM, Gorfein DS. A case of prolonged sleep deprivation. J Gen Psychol. (1964) 71:291–292. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Brauchi JT, West LJ. Sleep deprivation. JAMA (1959) 171:11–14. 10.1001/jama.1959.03010190013003 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Pasnau RO, Naitoh P, Stier S, Kollar EJ. The psychological effects of 205 hours of sleep deprivation. Arch Gen Psychiatry (1968) 18:496–505. 10.1001/archpsyc.1968.01740040112014 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1001/archpsyc.1968.01740040112014 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

43. Tyler DB. Psychological changes during experimental sleep deprivation. Dis Nerv Syst. (1955) 16:293–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Wright JB. Mania following sleep deprivation. Br J Psychiatry (1993) 163:679–80. 10.1192/bjp.163.5.679 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Patrick GTW, Gilbert JA. On the effects of loss of sleep. Psychol Rev. (1896) 3:469–83. 10.1037/h0075739 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. Ross JJ. Neurological findings after prolonged sleep deprivation. Arch Neurol. (1965) 12:399–403. 10.1001/archneur.1965.00460280069006 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

47. Williams HL, Morris G, Lubin A. Illusions, hallucinations and sleep loss. Acta Psychol. (1961) 19:805–6. 10.1016/S0001-6918(61)80372-7 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Kollar EJ, Pasnau RO, Rubin RT, Naitoh P, Slater GG, Kales A. Psychological, psychophysiological, and biochemical correlates of prolonged sleep deprivation. Am J Psychiatry (1969) 126:488–97. 10.1176/ajp.126.4.488 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psychiatry (1969) 126:488–97. 10.1176/ajp.126.4.488 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Chee MW, Chuah LY. Functional neuroimaging insights into how sleep and sleep deprivation affect memory and cognition. Curr Opin Neurol. (2008) 21:417–23. 10.1097/WCO.0b013e3283052cf7 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Banks S, Dinges DF. Behavioral and physiological consequences of sleep restriction. J Clin Sleep Med. (2007) 3:519–528. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Walker MP, Stickgold R. Sleep-dependent learning and memory consolidation. Neuron (2004) 44:121–33. 10.1016/j.neuron.2004.08.031 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Waters F, Bucks RS. Neuropsychological effects of sleep loss: implication for neuropsychologists. J Int Neuropsychol Soc. (2011) 17:571–86. 10.1017/S1355617711000610 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Adrien J. Neurobiological bases for the relation between sleep and depression. Sleep Med Rev. (2002) 6:341–51. 10.1053/smrv.2001.0200 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10.1053/smrv.2001.0200 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. Tsuno N, Besset A, Ritchie K. Sleep and depression. J Clin Psychiatry (2005) 66:1254–69 10.4088/JCP.v66n1008 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

55. Van Os J, Kenis G, Rutten BPF. The environment and schizophrenia. Nature (2010) 468:203–12. 10.1038/nature09563 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

56. Benedetti F, Zanardi R, Colombo C, Smeraldi E. Worsening of delusional depression after sleep deprivation: case reports. J Psychiatric Res. (1999) 33:69–72. 10.1016/S0022-3956(98)00053-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Frodl T, O'Keane V. How does the brain deal with cumulative stress? A review with focus on developmental stress, HPA axis function and hippocampal structure in humans. Neurobiol Dis. (2013) 52:24–37. 10.1016/j.nbd.2012.03.012 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

58. Zunszain PA, Anacker C, Cattaneo A, Carvalho LA, Pariante CM. Glucocorticoids, cytokines and brain abnormalities in depression. Prog NeuroPsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (2011) 35:722–9. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.04.011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Prog NeuroPsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry (2011) 35:722–9. 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.04.011 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

59. Alkadhi K, Zagaar M, Alhaider I, Salim S, Aleisa A. Neurobiological consequences of sleep deprivation. Curr Neuropharmacol. (2013) 11:231–49. 10.2174/1570159X11311030001 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

60. Redwine L, Hauger RL, Gillin JC, Irwin M. Effects of sleep and sleep deprivation on interleukin-6, growth hormone, cortisol, and melatonin levels in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. (2000) 85:3597–603. 10.1210/jc.85.10.3597 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

61. Vollert C, Zagaar M, Hovatta I, Taneja M, Vu A, Dao A, et al.. Exercise prevents sleep deprivation-associated anxiety-like behavior in rats: potential role of oxidative stress mechanisms. Behav Brain Res. (2011) 224:233–40. 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.05.010 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

62. Snyder F, Karacan I, Tharp VK, Jr, Scott J. Phenomenology of REMS dreaming. Psychophysiology (1968) 4:375. [Google Scholar]

Phenomenology of REMS dreaming. Psychophysiology (1968) 4:375. [Google Scholar]

63. Zadra AL, Nielsen TA, Donderi DC. Prevalence of auditory, olfactory, and gustatory experiences in home dreams. Percept Mot Skills (1998) 87:819–26. 10.2466/pms.1998.87.3.819 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

64. Foulkes D, Vogel G. Mental activity at sleep onset. J Abnorm Psychol. (1965) 70:231–43. 10.1037/h0022217 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

65. Leaning FE. An introductory study of hypnagogic phenomena, In Proceedings of the Society for Psychical Research (1925). pp. 289–409. [Google Scholar]

66. Ohayon MM, Priest RG, Caulet M, Guilleminault C. Hypnagogic and hypnopompic hallucinations: pathological phenomena? Br J Psychiatry (1996) 169:459–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Chee MW, Chuah YM. Functional neuroimaging and behavioral correlates of capacity decline in visual short-term memory after sleep deprivation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2007) 104:9487–92. 10. 1073/pnas.0610712104 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

1073/pnas.0610712104 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

68. Corsi-Cabrera M, Arce C, del Rio-Portilla I, Perez-Garci E, Guevara M. Amplitude reduction in visual event-related potentials as a function of sleep deprivation. Sleep (1999) 22:181–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Blom JD. Alice in Wonderland syndrome: a systematic review. Neurol Clin Pract. (2016) 6:259–70. 10.1212/CPJ.0000000000000251 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

70. Hadjikhani N, Sanchez del Rio M, Wu O, Schwartz D, Bakker D, Fischl B, et al.. Mechanisms of migraine aura revealed by functional MRI in human visual cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. (2001) 98:4687–92. 10.1073/pnas.071582498 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

71. Massimini M, Huber R, Ferrarelli F, Hill S, Tononi G. The sleep slow oscillation as a traveling wave. J Neurosci. (2004) 24:6862–70. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1318-04.2004 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

72. De Gennaro L, Marzano C, Veniero D, Moroni F, Fratello F, Curcio G, et al.. Neurophysiological correlates of sleepiness: a combined TMS and EEG study. Neuroimage (2007) 36:1277–87. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.013 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

De Gennaro L, Marzano C, Veniero D, Moroni F, Fratello F, Curcio G, et al.. Neurophysiological correlates of sleepiness: a combined TMS and EEG study. Neuroimage (2007) 36:1277–87. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.04.013 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

73. Lauritzen M, Gold L. Brain function and neurophysiological correlates of signals used in functional neuroimaging. J Neurosci. (2003) 23:3972–80. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-10-03972.2003 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

74. Marshall L, Born J. The contribution of sleep to hippocampus-dependent memory consolidation. Trends Cogn Sci. (2007) 11:442–50. 10.1016/j.tics.2007.09.001 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

75. Tung A, Takase L, Fornal C, Jacobs B. Effects of sleep deprivation and recovery sleep upon cell proliferation in adult rat dentate gyrus. Neuroscience (2005) 134:721–3. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.06.008 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

76. Drummond SP, Brown GG. The effects of total sleep deprivation on cerebral responses to cognitive performance. Neuropsychopharmacol (2001) 25(5, Suppl):S68–73. 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00325-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Neuropsychopharmacol (2001) 25(5, Suppl):S68–73. 10.1016/S0893-133X(01)00325-6 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

77. Tsai LL, Young HY, Hsieh S, Lee CS. Impairment of error monitoring following sleep deprivation. Sleep (2005) 28:707–13. 10.1093/sleep/28.6.707 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

78. Looijestijn J, Blom JD, Aleman A, Hoek HW, Goekoop R. An integrated network model of psychotic symptoms. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. (2015) 59:238–50. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2015.09.016 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

79. Waters F, Allen P, Aleman A, Fernyhough C, Woodward TS, Badcock JC, et al.. Auditory hallucinations in schizophrenia and nonschizophrenia populations: a review and integrated model of cognitive mechanisms. Schizophr Bull. (2012) 38:683–93. 10.1093/schbul/sbs045 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

80. Van Dongen HP, Maislin G, Mullington JM, Dinges DF. The cumulative cost of additional wakefulness: dose-response effects on neurobehavioral functions and sleep physiology from chronic sleep restriction and total sleep deprivation. Sleep (2003) 26:117–26. 10.1093/sleep/26.2.117 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Sleep (2003) 26:117–26. 10.1093/sleep/26.2.117 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

81. Perry EK, Perry RH. Acetylcholine and hallucinations-disease-related compared to drug-induced alterations in human consciousness. Brain Cogn. (1995) 28:240–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Tononi G, Cirelli C. Sleep and the price of plasticity: From synaptic and cellular homeostasis to memory consolidation and integration. Neuron (2014) 81:12–34. 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.12.025 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

83. Tucker DM, Roeltgen DP, Wann PD, Wertheimer RI. Memory dysfunction in myasthenia gravis: evidence for central cholinergic effects. Neurology (1988) 38:1173–7. 10.1212/WNL.38.8.1173 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

84. Kirov R. Monoamines in RCVH: implications from sleep, neurophysiologic, and clinical research. Behav Brain Sci. (2005) 28:768–9. 10.1017/S0140525X05330135 [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

85. Tufik S, Lindsey CJ, Carlini EA. Does REM sleep deprivation induce a supersensitivity of dopaminergic receptors in the rat brain? Pharmacology (1978) 16:98–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Gessa GL, Pani L, Fadda P, Fratta W. Sleep deprivation in the rat: An animal model of mania. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. (1995) 5:89–93. 10.1016/0924-977X(95)00023-I [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

87. Heiss WD, Herholz K. Brain receptor imaging. J Nucl Med. (2006) 47:302–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

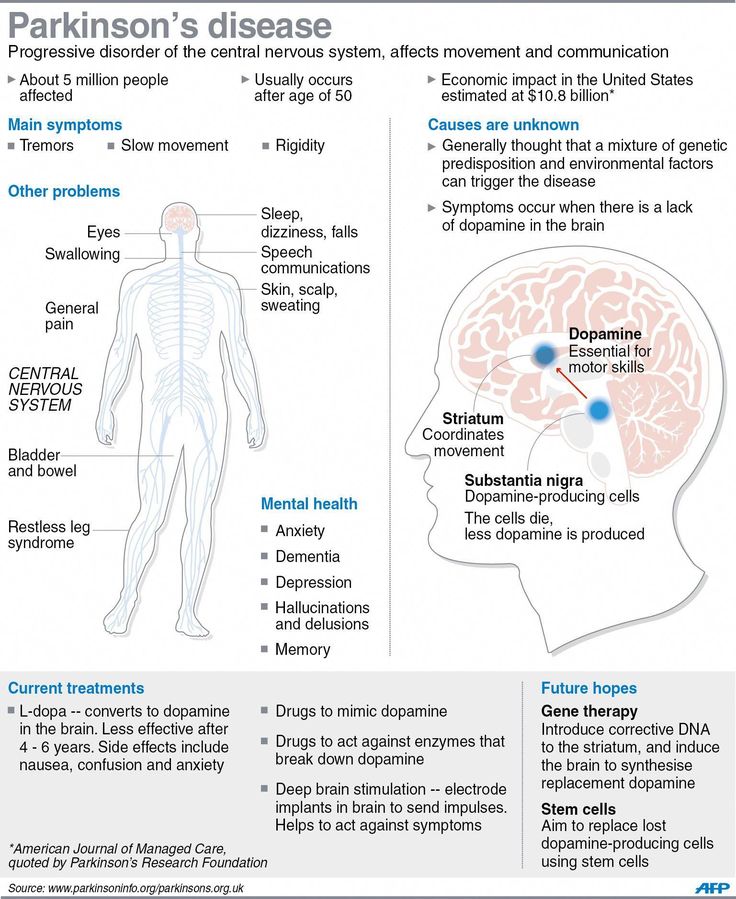

88. Bosboom JL, Stoffers D, Wolters E. The role of acetylcholine and dopamine in dementia and psychosis in Parkinson's disease. J Neural Transm Suppl. (2003) 65:185–95. 10.1007/978-3-7091-0643-3_11 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

89. Calabresi P, Picconi B, Tozzi A, Di Filippo M. Dopamine-mediated regulation of corticostriatal synaptic plasticity. Trends Neurosci. (2007) 30:211–9. 10.1016/j.tins.2007.03.001 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

90. Gottesmann C. Neurophysiological support of consciousness during waking and sleep. Prog Neurobiol. (1999) 59:469–508. 10.1016/S0301-0082(99)00014-3 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

91. Clarke PG, Clarke S. Nineteenth century research on cell death. Exp Oncol. (2012) 34:139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clarke PG, Clarke S. Nineteenth century research on cell death. Exp Oncol. (2012) 34:139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Pulsinelli WA, Brierley JB, Plum F. Temporal profile of neuronal damage in a model of transient forebrain ischemia. Ann Neurol. (1982) 11:491–8. 10.1002/ana.410110509 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

93. Li R, Yu K, Wang Q, Wang L, Mao J, Qian J. Pellagra secondary to medication and alcoholism: a case report and review of the literature. Nutr Clin Pract. (2016) 31:785–9. 10.1177/0884533616660991 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

94. Post FA. Pellagra: a rare complication of isoniazid therapy. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. (2016) 20:1136. 10.5588/ijtld.16.0352 [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

95. Ishii N, Nishihara Y. Pellagra encephalopathy among tuberculous patients: its relation to isoniazid therapy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry (1985) 48:628–34. 10.1136/jnnp.48.7.628 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

96. Reimund E. Sleep deprivation-induced dermatitis: further support of nicotinic acid depletion in sleep deprivation. Med Hypotheses (1991a) 36:371–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sleep deprivation-induced dermatitis: further support of nicotinic acid depletion in sleep deprivation. Med Hypotheses (1991a) 36:371–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Reimund E. Sleep deprivation-induced neuronal damage may be due to nicotinic acid depletion. Med Hypotheses (1991b) 34:275–277. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Waters F, Blom JD, Dang-Vu TT, Cheyne AJ, Alderson-Day B, Woodruff P, et al.. What is the link between hallucinations, dreams, and hypnagogic-hypnopompic experiences? Schizophr Bull. (2016) 42:1098–109. 10.1093/schbul/sbw076 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

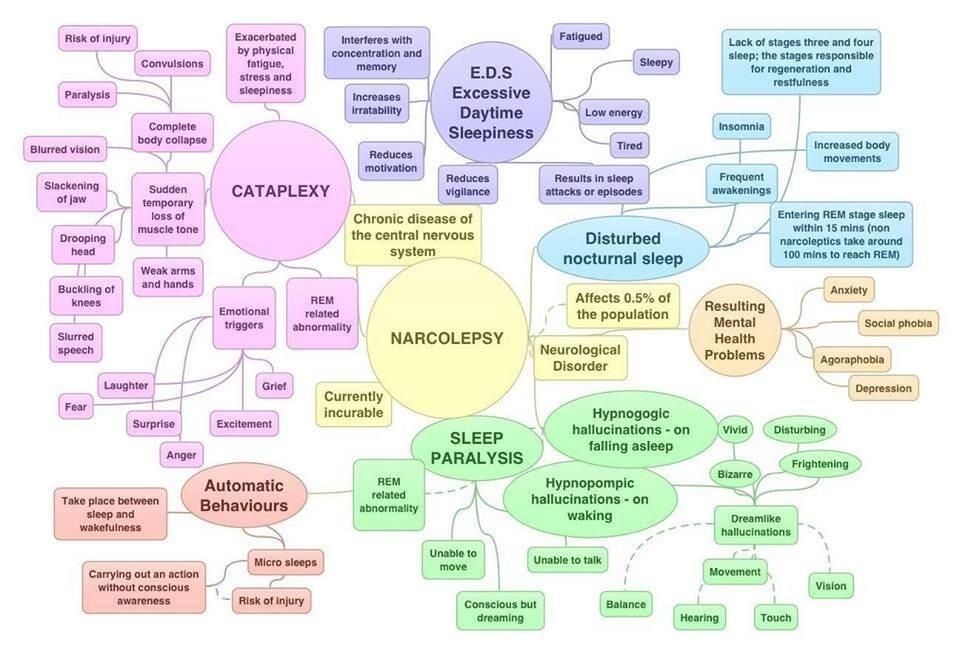

Sleep Deprivation Psychosis Is A Real Thing

WebMD Connect to Care helps you find services to manage your health. When you purchase any of these services, WebMD may receive a fee. WebMD does not endorse any product, service or treatment referred to on this page. X

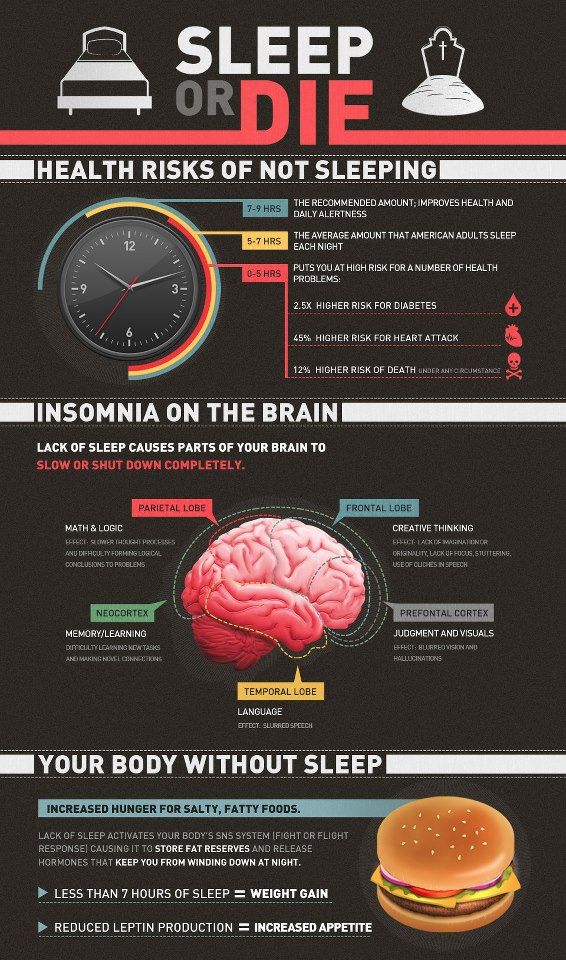

By Lan Pham, John McGuireStudies have shown that the longer you go without sleep, the higher your likelihood for developing serious psychiatric symptoms—including a disconnection from reality and hallucinations.

Sleep deprivation psychosis—when the absence of sleep causes a disconnection from reality that can present as hallucinations or delusional thinking—is a known effect of severe, prolonged sleep deprivation. Here, we explain what you need to know about sleep deprivation psychosis and what you can do about it.

What is Sleep Deprivation Psychosis?

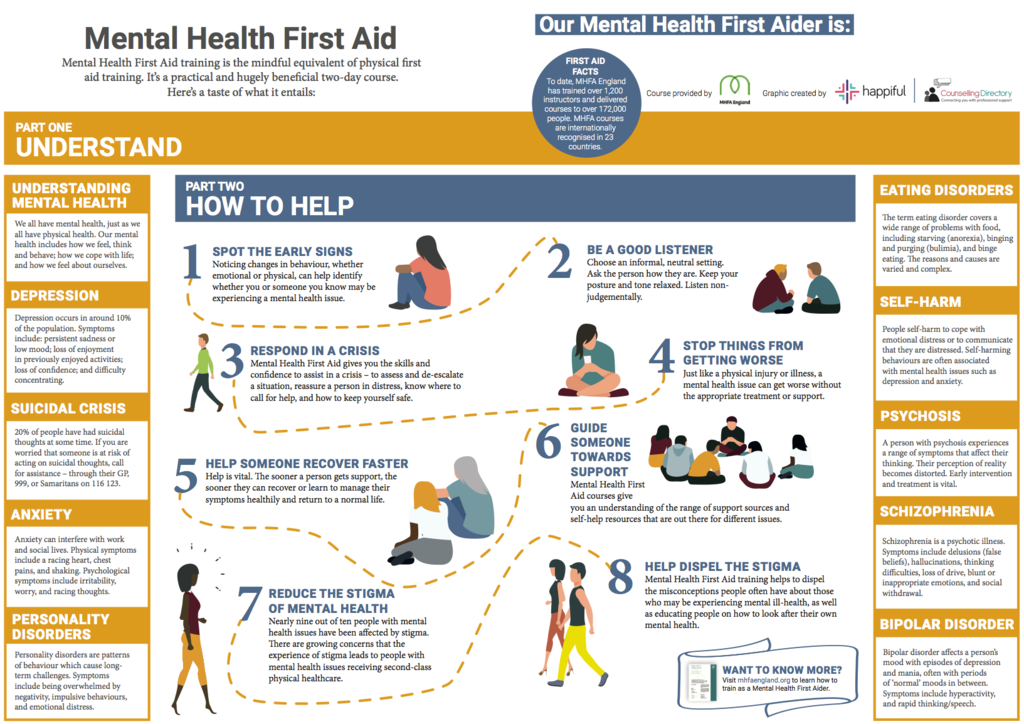

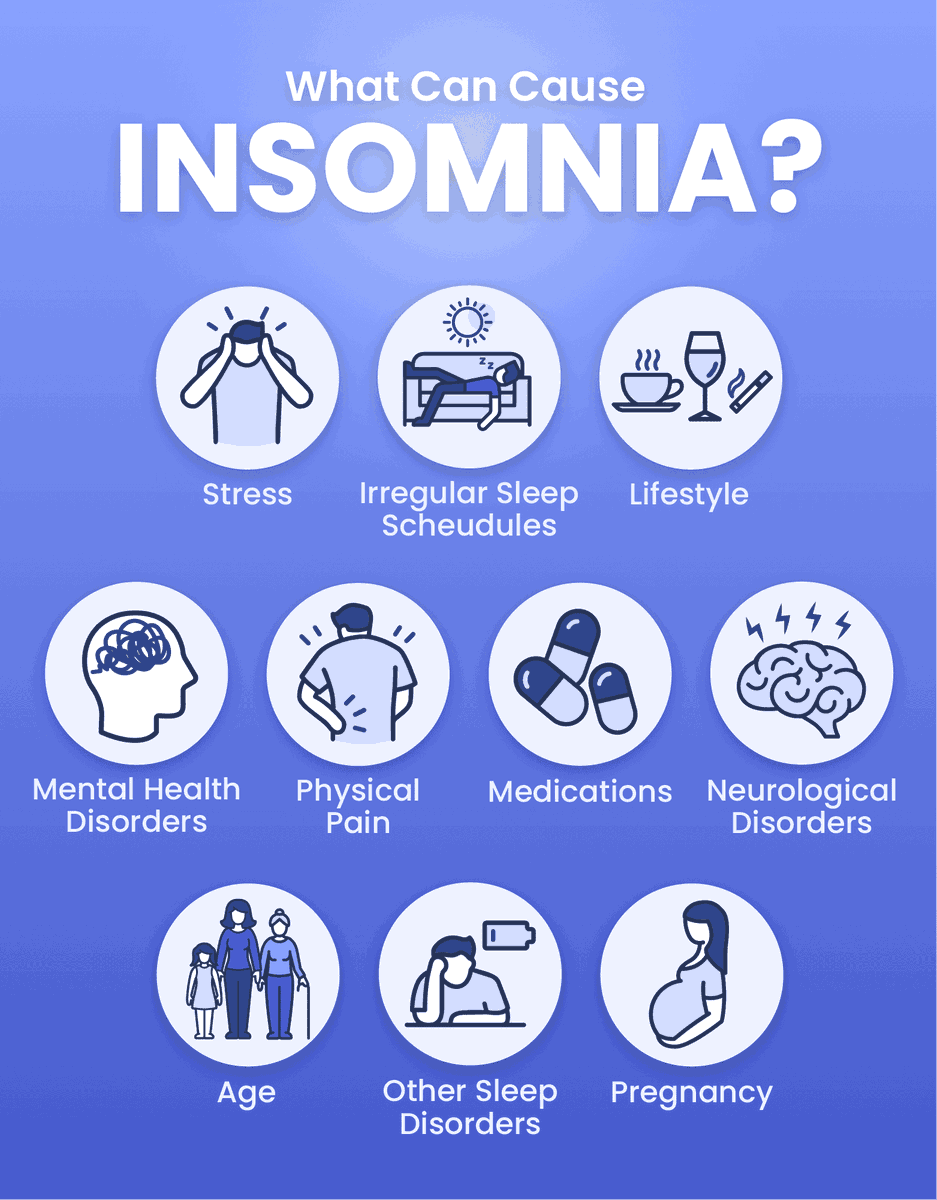

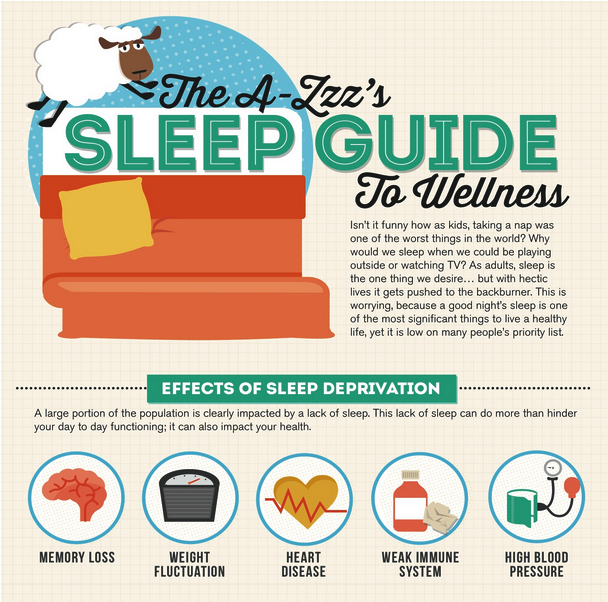

The quality of your mental health is closely connected to your sleep patterns, according to Harvard Medical School. In fact, sleep problems, including sleep deprivation, are especially common among those with anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Additionally, sleep deprivation can contribute to symptoms resembling psychosis, which is when a person becomes disconnected from reality. Yale School of Medicine characterizes the symptoms of psychosis as:

- Confused thinking: Muddled thinking, difficulty concentrating, speech that doesn’t make sense, or racing thoughts.

- False beliefs: When a person is convinced of an idea that is counter to reality, also called a delusion.

- Hallucinations: When a person senses something that is not there. Hallucinations can involve all five senses.

- Changed feelings: This can present as unusual or unexplained mood swings or dampened emotional responses.

- Changed behaviors: This is erratic or unusual behavior compared to a person’s baseline.

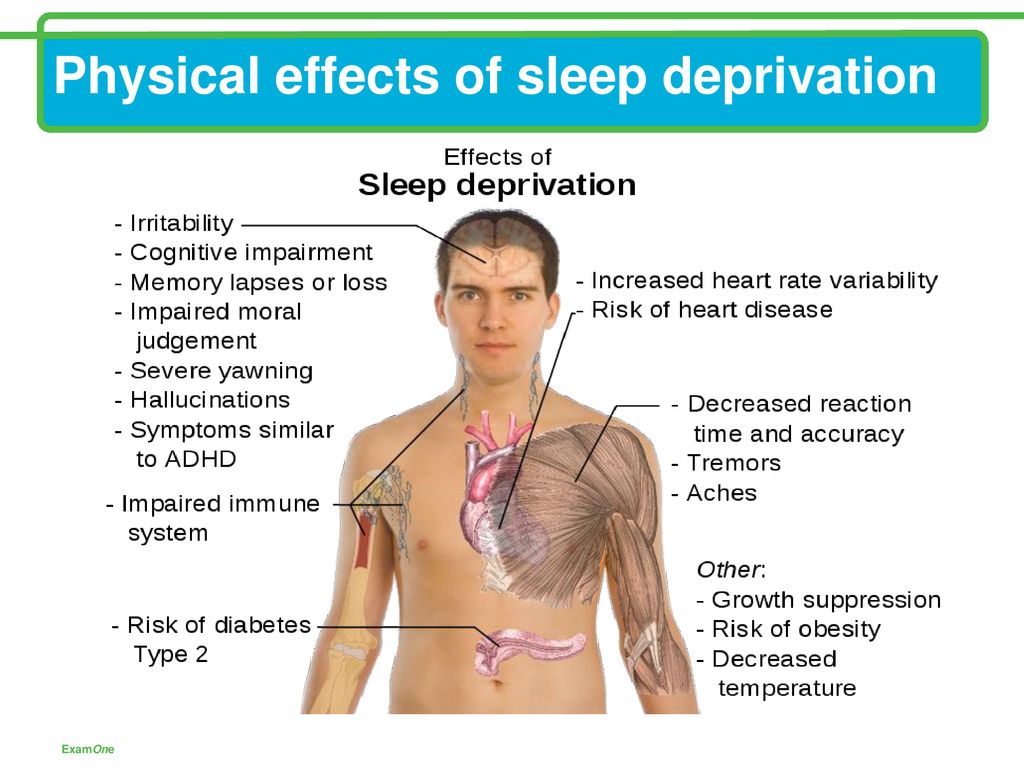

A 2018 systematic review published by Frontiers in Psychiatry found that long periods of sleep deprivation can result in a range of psychiatric symptoms, including perceptual distortions and hallucinations.

Furthermore, after examining pertinent literature, the review found that psychiatric symptoms escalate in tandem with an increasing amount of time awake. In the absence of sleep, these symptoms typically begin with simple visual or somatosensory misperceptions, before developing into hallucinations and delusions and potentially ending in a state resembling acute psychosis.

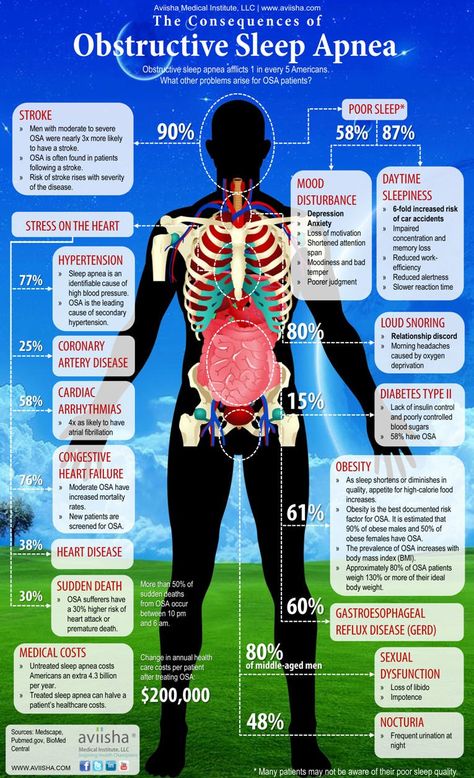

Furthermore, certain sleep disorders are known to co-occur with symptoms of psychosis. A 2016 research article published by Frontiers in Psychiatry studied a sample population of patients with psychosis and found that this population had high levels of sleep disturbance, including obstructive sleep apnea.

How to Treat Sleep Deprivation-Induced Psychosis

Simply put, the restoration of proper amounts of sleep can decrease the presence of psychotic experiences. A 2015 systematic review published by Clinical Psychology Review found that, while sleep dysfunction can indeed contribute to psychotic symptoms such as delusions and hallucinations, improvements in the sleep quality of patients experiencing psychosis may lessen psychotic symptoms.

Additionally, complete diagnostic screening for sleep disorders may be necessary. “The brain needs proper sleep to function normally. If a sleep disorder is suspected, it’s critical to get a proper diagnosis for optimal health”, Bradley Eli, D. M.D., M.S., a Sleep Medicine specialist in Encinitas, Calif., tells WebMD Connect to Care.

M.D., M.S., a Sleep Medicine specialist in Encinitas, Calif., tells WebMD Connect to Care.

The 2015 review published by Clinical Psychology Review affirms this, citing extensive scientific literature demonstrating that treatment of sleep apnea in patients with psychosis improves both psychotic symptoms and sleep quality.

In the case of sleep apnea, treatment may include the following interventions, according to Cleveland Clinic:

- Weight loss

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)

- Mandibular advancement devices

- Hypoglossal nerve stimulation

- Upper airway or jaw surgery

Think you may have a sleep disorder? Start your journey to more restful sleep TODAY.

Untreated sleep disorders can negatively affect your physical and emotional health. Sleep testing can help you get the answers you need to receive the treatment you deserve. WebMD Connect to Care Advisors are standing by to help.

WebMD Connect to Care Advisors are standing by to help.

What happens to our brain due to lack of sleep

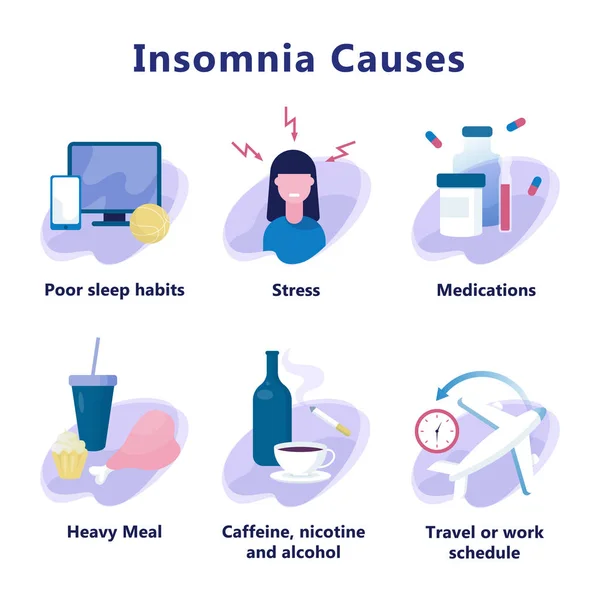

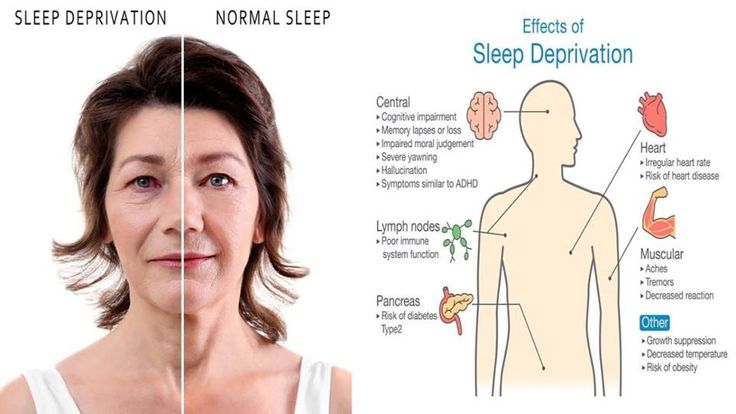

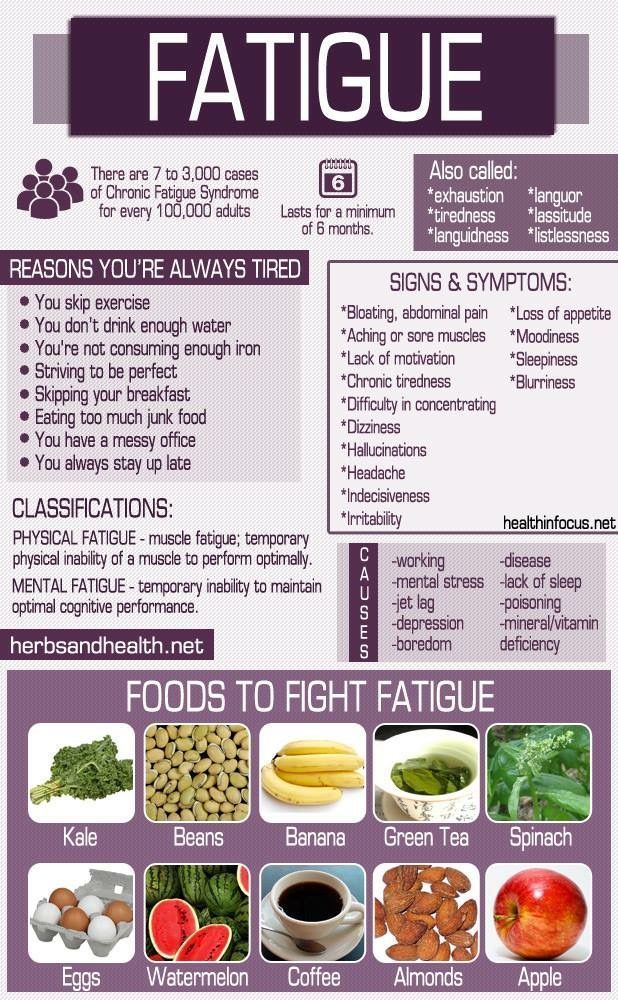

What is the danger of insomnia? Every neurologist knows that insomnia is an insidious time bomb in our body. It begins with difficulties in falling asleep, as well as short-term sleep disorders, and, as a result, leads a person to physical and nervous exhaustion.

Insomnia can cause quite serious disorders of the central nervous system, psychosis, depression, lack of sufficient normal sleep increases the risk of developing dangerous diseases such as stroke and heart attack. nine0003

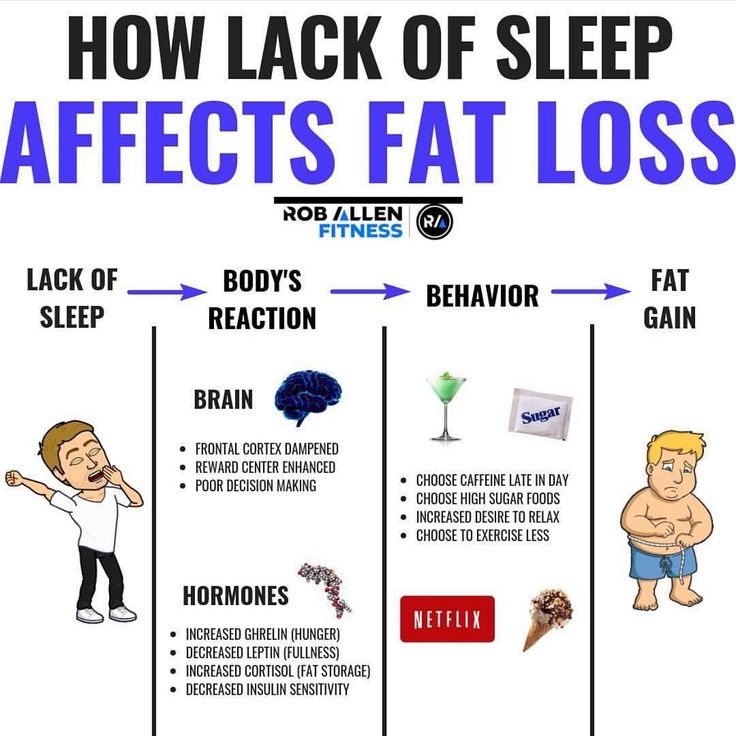

Insomnia and lack of sleep significantly reduce the quality of human life, cause apathy, irritability and increased fatigue. A “sleep-deprived” person may develop memory problems, reduce mental and physical activity, and this will have a negative impact on your professional activities.

The main danger of lack of sleep lies in the development (against the background of insomnia) of panic and anxiety disorders, which bring with them a significant deterioration in the quality of life and problems in the labor and social areas. nine0003

nine0003

The idea of a connection between sleep and somatic, mental illness is not new. Already at the end of the XlX century, Dr. Griesinger (1867) put forward the idea that certain types of mental illness are the result of long-term sleep disturbances.

G. Krokhalev, a psychiatrist from the city of Perm, developed the same idea in his monograph "Schizophrenia - informational psychosis". His inspiration and teacher was A. Altman, Doctor of Medical Sciences, who became an honorary member of the All-Russian Scientific Medical Society of Psychiatrists and Neurologists. nine0003

In his writings, Krokhalev writes that all patients confirmed that the initial symptoms of schizophrenia included sleep disorders, including complete insomnia. Sleep disturbances lead to the emergence of hypnotic states in the central nervous system, as well as to the development of a schizophrenic process, and its attenuation is associated with the normalization of the "sleepy" function.

This psychiatrist rejects schizophrenia as a separate independent disease. The doctor believes that the brain of patients is healthy, simply because of the lack of sleep at night, it seems to "switch" into sleep mode during the day, right during wakefulness. nine0003

The doctor believes that the brain of patients is healthy, simply because of the lack of sleep at night, it seems to "switch" into sleep mode during the day, right during wakefulness. nine0003

An interesting fact is that to prove his theory, the doctor cites the results of experiments conducted by A. Wayne (1970) on healthy people who were deprived of sleep voluntarily. After ninety hours without sleep, people began to hallucinate, while short dreams seemed to be intertwined with reality.

Already after one hundred and seventy hours of wakefulness, depersonalization was noticed, a violation of the selection of one's own "I" and consciousness. Two hundred hours of experience led the subjects to feel that they were the victims of a sadistic conspiracy, psychomotor agitation appeared, that is, signs of paranoid schizophrenia appeared. nine0003

Thus, we can conclude that a healthy person can be introduced into a schizophrenic state on purpose, simply by depriving him of sleep. At the end of the sleep deprivation experiment, the volunteers were allowed to sleep for 12 to 14 hours and all pathological changes disappeared.

At the end of the sleep deprivation experiment, the volunteers were allowed to sleep for 12 to 14 hours and all pathological changes disappeared.

Sleep is one of the most important processes in the human body. In a dream, we translate the information received during the day from short-term memory into long-term memory, using symbols and associations.

When the human brain does not have time to do all this at night due to insufficient time for sleep, it begins to carry out this process in the daytime. And all the classic symptoms of schizophrenia appear, as reported by Krokhalev. nine0003

A person simply sleeps in reality and sees dreams, which outwardly manifests itself as hallucinations and delusions. The doctor calls this condition informational psychosis and information poisoning of the brain.

The father of cybernetics N. Wiener compared the brain with a biocomputer or a cybernetic machine, and was of the opinion that it has its own certain limit of information received. Due to insomnia in the brain, an overload of the information system occurs with subsequent disorders in the programming of brain activity. nine0003

Due to insomnia in the brain, an overload of the information system occurs with subsequent disorders in the programming of brain activity. nine0003

In this regard, Korkhalev offers his method of getting out of this difficult unnatural state - a physiological long sleep. Eight hours of sleep can also be evaluated as a prophylactic against the onset of psychosis and, in general, against schizophrenia in various forms.

Treatment for dizziness

How does it feel to hallucinate as a result of sleep deprivation?

Image via Flickr user DonJinTX

Image via Flickr user DonJinTX

With the ban imposed by the US Senate on interrogation techniques used after the 9/11 attacks, I became preoccupied with the subject of sleep deprivation. Recently declassified documents state: "At least five detainees experienced disturbing hallucinations during prolonged sleep deprivation." It got me wondering what these sleepless nightmares are, and how and why, scientifically speaking, prolonged sleep deprivation causes them. To find out, I contacted Danny Eckert, an associate professor at the Australian University of New South Wales. Eckert is an expert in neuroscience and sleep, and as he explains it, we should sleep because cellular respiration releases waste products. While there is still some debate as to which of these by-products contribute to fatigue, there is some consensus on one of them called adenosine. “While people are awake, adenosine accumulates in the brain,” explains Professor Eckert. "And too much of it can cause hallucinations." nine0003

To find out, I contacted Danny Eckert, an associate professor at the Australian University of New South Wales. Eckert is an expert in neuroscience and sleep, and as he explains it, we should sleep because cellular respiration releases waste products. While there is still some debate as to which of these by-products contribute to fatigue, there is some consensus on one of them called adenosine. “While people are awake, adenosine accumulates in the brain,” explains Professor Eckert. "And too much of it can cause hallucinations." nine0003

Advertisement

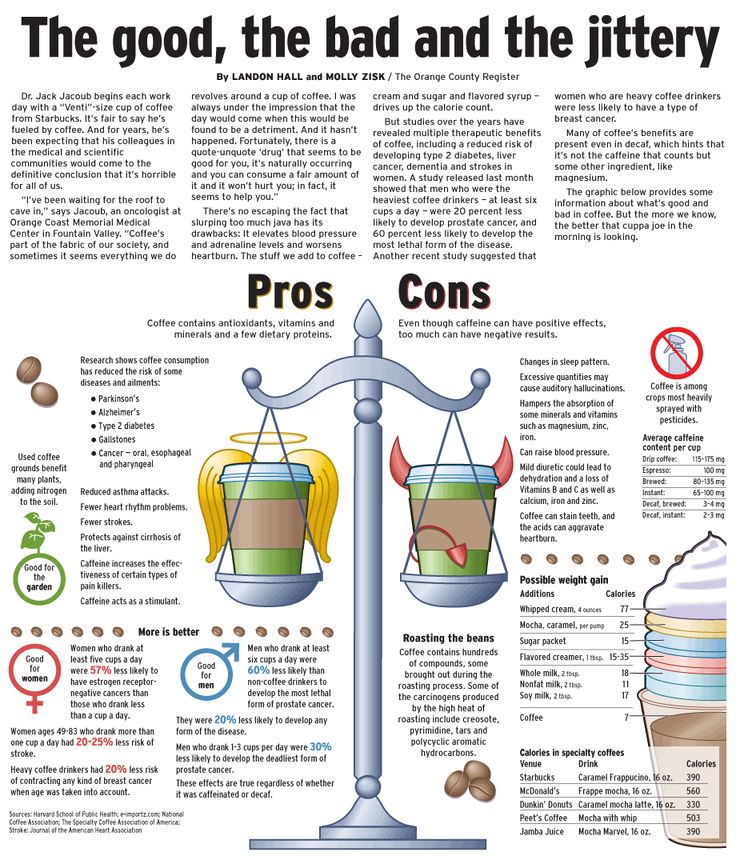

If you studied biology in high school, you may remember that cellular respiration is the process by which glucose is converted into adenosine triphosphate (ATP), which our body uses for fuel. But what's really interesting is that adenosine, which is the molecular basis of ATP, makes us sleepy. In fact, animal experiments with adenosine have shown that it causes an almost immediate loss of consciousness, while stimulants like coffee simply block the adenosine receptor pathways. nine0003

nine0003

Despite this, many scientists do not agree that adenosine is the cause of hallucinations. So, Dr. Sean P. Drummond, a neuroscientist at Monash University, insists that the occurrence of hallucinations depends on a genetic predisposition. “If someone is psychotic, then sleep deprivation can exacerbate psychotic symptoms,” he says. “And everyone else will simply not have such a reaction.”

Jess Flandria is a New Zealander who is experimenting with prolonged sleep deprivation. In 2012, Jess began to become interested in lucid dreaming and watch videos on the subject on the YouTube channel of Geese Edwards. Giese spent a lot of time discussing the intersections between dreams and hallucinations, which inspired Jess to experiment with not sleeping for nearly 110 hours, or four and a half days, and then posting a series of videos on YouTube about her experience. nine0003

Advertising

According to Jess, the experiment was intended to test willpower and see if it was possible to achieve hallucinations without drugs. She found that it was possible. “Some of the pictures reminded me of the effects of ayahuasca,” she said to Weiss. “I felt like I was seeing a colorful, complex universe in front of me even though I was awake. It was very surreal."

She found that it was possible. “Some of the pictures reminded me of the effects of ayahuasca,” she said to Weiss. “I felt like I was seeing a colorful, complex universe in front of me even though I was awake. It was very surreal."

It's like being in a cartoon. People and objects become very comical.

Jess also told me that she experienced something called coordinating seizure, which is commonly associated with epilepsy. The US National Library lists symptoms such as "continuous staring, sometimes with repetitive movements such as pinching clothes or smacking lips," as well as muscle contractions and memory loss. Indeed, Jess admits that she doesn't remember anything about how it all started, only that "my friend said I passed out. Apparently, I was shaking my head from side to side and talking to him at the same time. Then I couldn't stop giggling." nine0003

When I asked her to describe how everything happened, she replied that she wanted to fall asleep all the time, although the visions were pleasant. “The first 24 hours were the easiest. After that it got harder and harder,” she says. “You are like in a cartoon. People and objects seem very comical and I had many hallucinations. Cars floated, tree shadows jumped, zombies followed me down the street. It seemed to me that I could control the clouds, their appearance and change in shape. In the supermarket, the goods on the shelves seemed to follow me. The shelves seemed to be tilting and about to fall.” nine0003

“The first 24 hours were the easiest. After that it got harder and harder,” she says. “You are like in a cartoon. People and objects seem very comical and I had many hallucinations. Cars floated, tree shadows jumped, zombies followed me down the street. It seemed to me that I could control the clouds, their appearance and change in shape. In the supermarket, the goods on the shelves seemed to follow me. The shelves seemed to be tilting and about to fall.” nine0003

Advertisement

According to Jess, she was not afraid of any long-term impact, although she was aware of the risks. As the president of the Australian Sleep Association, Professor Nicholas Antik, told me, "Sleep deprivation can certainly be dangerous." According to him, "during sleep, products of its work are released from the brain through the lymphatic system, and the accumulation of such products is dangerous."

While the health consequences of sleep deprivation are well known to any conscious being on the planet, most of us do not think of it as a mortal danger.