Can i commit my child to a mental institution

Psychiatric Hospitalization: When It's the Right Option and What to Expect

Psychiatric Hospitalization: When It’s the Right Option and What to Expect

The thought of a psychiatric hospitalization can be very scary for a family. Read on to learn more about what you can expect from taking this step and how to navigate this difficult decision. This is one of the topics covered in When Your Adult Child Breaks Your Heart.

Psychiatric Hospitalization: When It's the Right Option and What to Expect

When most people picture a psychiatric hospital, they envision a dark and dreary place filled with severely incapacitated people. But contemporary psychiatric hospitals fall far short of this stereotype, offering a range of services to people with virtually every variety of mental health disorder. The average psychiatric hospital stay is about seven days, with the primary goal of stabilization vs. "cure.

" Psychiatric hospitalization is not a panacea for mental health disorders, but it can be the first step toward getting your child back on track.

When is Psychiatric Hospitalization Appropriate?

Psychiatric hospitalization is short-term emergency care, making it an untenable option for people struggling with minor depression or mental health conditions that do not affect daily functioning. However, anyone can voluntarily check themselves into a psychiatric hospital, and some people find that the short-term intense care is the best way to get a proper diagnosis and a rigorous treatment plan.

Generally speaking, psychiatric hospitalization works best for people who pose a threat to themselves or others. Suicide threats, drug overdoses, threats of violence to family members, psychosis, and the inability to provide basic care for oneself can all be reasons to have a child hospitalized.

Can I Have My Child Committed?

You can't force an adult child to enter a psychiatric hospital; you can only offer incentives for her to go. You can, however, enlist the assistance of a court, therapist, or police officer to have your child committed against her will. You'll have to demonstrate that your child poses a threat to themselves or someone else, and your own testimony will generally not be sufficient. There must be evidence, or someone else must witness the behavior. If a doctor or therapist deems your child a threat, this is generally sufficient to have them committed. There are three typical paths to commitment:

You can, however, enlist the assistance of a court, therapist, or police officer to have your child committed against her will. You'll have to demonstrate that your child poses a threat to themselves or someone else, and your own testimony will generally not be sufficient. There must be evidence, or someone else must witness the behavior. If a doctor or therapist deems your child a threat, this is generally sufficient to have them committed. There are three typical paths to commitment:

· A medical professional, such as a therapist or psychiatrist, can recommend your child be committed and file paperwork with a court to do so.

· You can petition a court to have your child committed.

· You can call the police when your child is acting out and if the police view your child as a danger, they might have your child committed. This is a risky strategy, though, because the police might also choose to simply arrest your child.

What Happens in the Hospital?

Psychiatric hospitals vary greatly in terms of quality, with some acting as little more than holding facilities and others providing extensive, comprehensive treatment. Consequently, it is a wise strategy to research options and select a hospital before your child is committed.

Consequently, it is a wise strategy to research options and select a hospital before your child is committed.

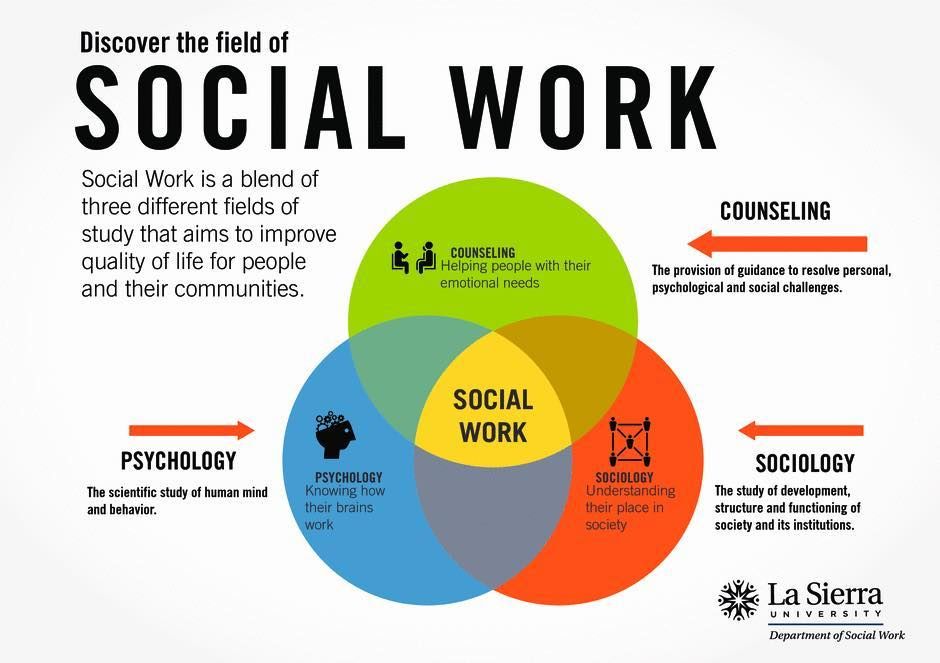

After your child is admitted, a physician and possibly a social worker or other advocate will consult with your child. Your child will have a comprehensive review of symptoms, and the treatment team will develop a plan that may include medication, therapy, life skills training, group sessions, and activities such as art and yoga. The treatment team may also recommend family sessions to enable your entire family to discuss problems and work together to help your child get better. Your child will typically be allowed to make phone calls and receive letters unless the treatment team deems outside communication a risk for your child's well-being.

When Will My Child Be Discharged?

If your child is involuntarily committed, they will be placed on a 72-hour hold and stay in the hospital for at least this time period. Thereafter, your child has a right to a hearing to determine whether hospitalization will continue. At any point during the stay, if your child feels their rights are being violated, they can request an attorney. However, they are not entitled to free legal counsel as public defenders are reserved for criminal cases.

At any point during the stay, if your child feels their rights are being violated, they can request an attorney. However, they are not entitled to free legal counsel as public defenders are reserved for criminal cases.

Generally, your child will only be discharged when stable and the treatment team determines that your child is no longer an immediate threat to themselves or others. However, this does not mean that your child is completely well. Your child will need to continue with treatment and may require extensive therapy, daily outpatient treatment, ongoing medical evaluations, and medication.

Psychiatric hospitalization is the beginning, and not the end, of treatment. Your child might have to be hospitalized several times before you see progress. If your child wants to get better, it is a wise strategy to provide emotional support and a friendly ear during hospitalization. However, you are under no obligation to pay for treatment, allow your child to live with you, or offer any specific help.

References:

Geller, J. L. (2006). A History of Private Psychiatric Hospitals in the USA: From Start to Almost Finished. Psychiatric Quarterly, 77(1), 1-41. doi: 10.1007/s11126-006-7959-5

Having a Child in Emergency Inpatient Treatment

Dear Parent,

I am so sorry you need to read this letter. If your child is heading for hospitalization, you are in a tough place, and a scary one. Hopefully, as you read this you will have a better idea of what lies ahead.

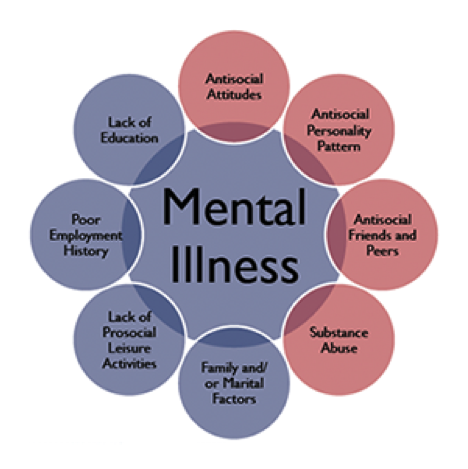

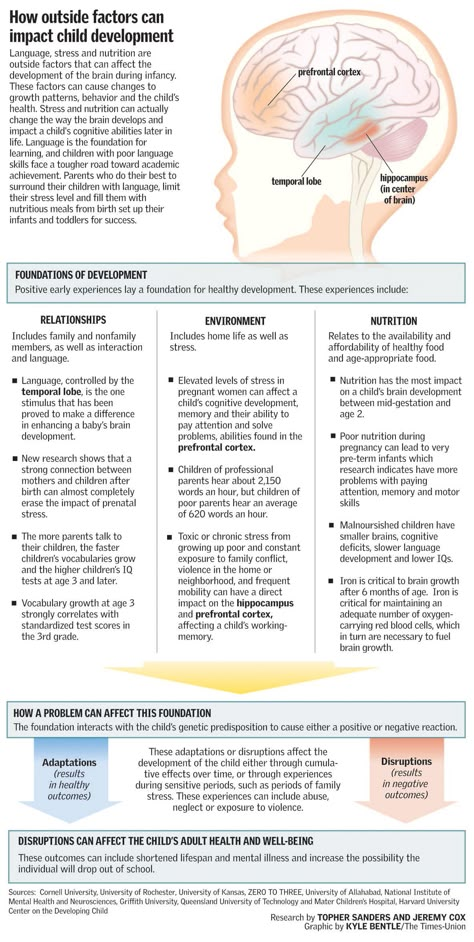

What to expect when you arriveAssuming your child has been referred to inpatient from an emergency room, once an inpatient bed is found, your child will be transported by ambulance to the facility. You will be allowed to ride along. There will be another intake assessment upon arrival, at which you will have to re-tell the saga of what led up to the hospitalization. You will be asked about your family’s history of mental illness. Be 100% honest. Genetics play a huge role in mental health, and if you have an aunt with schizophrenia, a cousin who committed suicide and your spouse’s Grandpa Joe self-treated his depression with alcohol, this is relevant to the kinds of medications that may be appropriate for your child.

Genetics play a huge role in mental health, and if you have an aunt with schizophrenia, a cousin who committed suicide and your spouse’s Grandpa Joe self-treated his depression with alcohol, this is relevant to the kinds of medications that may be appropriate for your child.

Ask under what circumstances the hospital will reach out to you. There are likely to be only three situations that trigger a phone call:

- They want to add to or change your child’s medication and need your permission to do so. They will only contact you for new meds, not for subsequent increases or decreases in dosage. If you get a call like this, write down the date, time, name of the doctor, and what the conversation consisted of.

- Your child has been involved in an “incident.” This may be a physical accident (rare), injury caused by another patient (rare), or notification that your child was taken to a seclusion room because she became violent (hopefully not your nightmare).

If you get a call like this, ask for details. If your child was taken to seclusion, you want to know if they went willingly, if they were taken by force, and if restraints were used. Write this down in a notebook, ask questions about what led up to the incident, record the date of the call and the name of the person calling, and later speak to your child to get his version of the story. If need be, you should also get an account of what happened from someone else who witnessed it. Every account will be different. That doesn’t mean someone lied, just that you’re not going to get the full story from one perspective.

If you get a call like this, ask for details. If your child was taken to seclusion, you want to know if they went willingly, if they were taken by force, and if restraints were used. Write this down in a notebook, ask questions about what led up to the incident, record the date of the call and the name of the person calling, and later speak to your child to get his version of the story. If need be, you should also get an account of what happened from someone else who witnessed it. Every account will be different. That doesn’t mean someone lied, just that you’re not going to get the full story from one perspective. - They want to set up a “family meeting” to discuss plans for discharge. This will happen several days or even a week before the actual discharge because it takes a while to put plans in place. “Family,” in this case, means the parent, the child in the hospital, a social worker, and usually the psychiatrist. Take copious notes at the meeting, or bring someone (spouse or relative) to take notes for you.

If you did not already have a treatment team prior to hospitalization, the social worker will help you find one; in most states, you will need an appointment on the books before discharge. Private-pay hospitals may not need to follow the same procedures.

If you did not already have a treatment team prior to hospitalization, the social worker will help you find one; in most states, you will need an appointment on the books before discharge. Private-pay hospitals may not need to follow the same procedures.

You will be able to call the nurse’s station whenever you want to find out how your child is doing, to ask questions, or to ask to have the doctor or social worker call you. Put the number of the nursing station into your phone immediately so you don’t lose it.

If you have missed a meal in transit, ask for food. Most intake departments will have sandwiches or something on hand, but the actual unit will not.

Leaving your child

Someone will sort through your child’s belongings and decide what can and can’t stay on the unit. Anything sharp, made of glass or long enough to tie around the neck (including belts, drawstrings and shoelaces) will not be permitted. Some hospitals do a body check, so that the hospital has an inventory of the patient’s wounds and scars prior to entry. Then your child will be brought over to their room. You will probably be allowed to go along to say goodbye.

Then your child will be brought over to their room. You will probably be allowed to go along to say goodbye.

Prepare yourself. The psychiatric unit will almost certainly be locked with a two-stage door system. You will later have to show ID to enter, and phones with cameras are usually not allowed (so no one can post pictures of patients online). A nurse on the unit will ask you whose names should be placed on the visitor list. In some cases, only family is permitted. You are not obligated to include relatives who will be critical of you or your child when they visit. Only list people who will be helpful.

You will almost surely cry after you leave your child and the door is locked behind you. You are allowed. But if you are so overwhelmed that you feel numb, that’s normal, also.

What will happen once your child is inThe key bit of information you need to swallow up front is that the sole purpose of an inpatient stay is to stabilize your child enough so that they can be discharged to outpatient care. In other words, they aren’t going to cure anything here. At best, your child’s symptoms or behavior will improve by 10%, maybe 20%. That’s a long way from the complete hell you’ve been living in, but it’s almost certainly not what you were hoping for.

In other words, they aren’t going to cure anything here. At best, your child’s symptoms or behavior will improve by 10%, maybe 20%. That’s a long way from the complete hell you’ve been living in, but it’s almost certainly not what you were hoping for.

As with other hospitals, nothing of substance happens on weekends. If your child enters on a Friday, Saturday, or Sunday, he won’t be evaluated by the regular team on the unit until Monday.

Once the doctors have visited with your child (you won’t be there when this happens), they will come up with a working diagnosis.

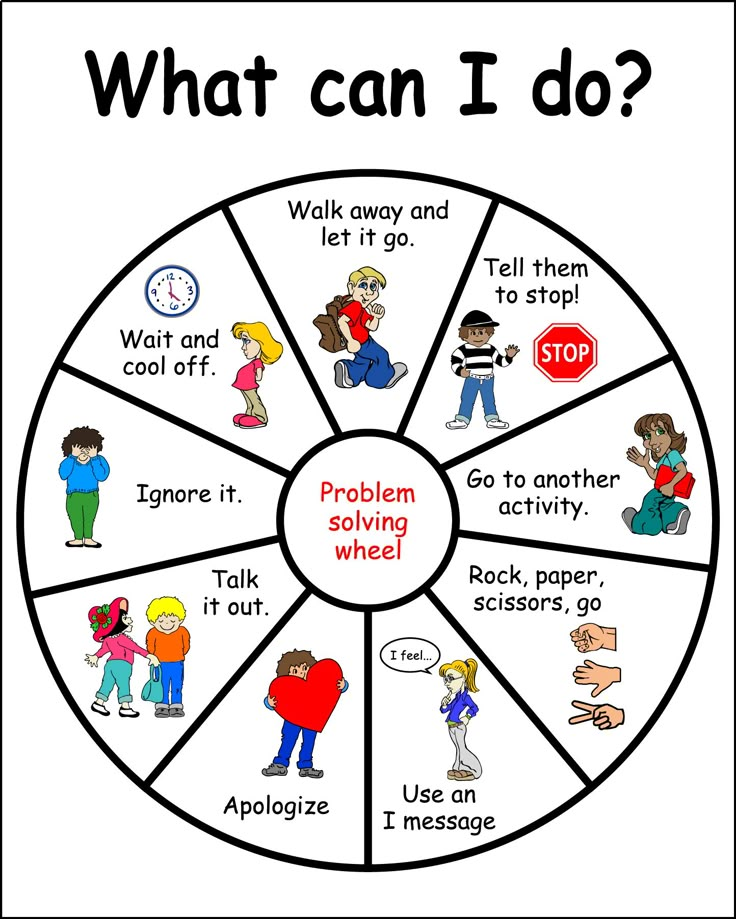

Your child’s day will be structured on a schedule that includes a daily (brief) check-in by medical staff, school (usually only an hour or two, of limited educational value, but your child will get attendance credit), and various group therapies. These may include classes or groups on coping skills, information on mental health, and family therapy. Some hospitals also use experiential therapies that incorporate animals, music, art, or horticulture. There is unlikely to be any individual counseling. Remember, the goal isn’t to get to the bottom of anything. The goal is to get your child stable enough to move to outpatient treatment, where long-term work takes place.

There is unlikely to be any individual counseling. Remember, the goal isn’t to get to the bottom of anything. The goal is to get your child stable enough to move to outpatient treatment, where long-term work takes place.

The TV in the day room will blare during free time, and much of the day will be very low-key. This can make it seem that the hospital isn’t doing much of anything. What they do is provide structure, medication, and monitoring. (If you stop to think about it, this is pretty much what a medical hospital does, too, minus the structure). The group therapies do tend to force depressed kids to get up and do something and tend to tone down the pace of the over-activated kids.

Rules and privilegesMost psychiatric hospitals use some kind of level system in which the kids earn privileges if they comply with behavioral expectations. You don’t need to know the details; your child will gripe about them. Your job is to nod and empathize.

You may be shocked by the limited visiting hours. Then again, you’re likely to have some ambivalence about visiting or are unable to get to the hospital easily. You don’t need to come every day; the most important time to visit is on the weekends when there’s less structure and less for the kids to do. If you bring food (which your child will probably beg you to do), ask in advance about what’s allowed. Bring it in a paper bag; plastic won’t be allowed.

There will be a ton of rules. The ridiculous nature of many of them will be the topic of your conversation with your child over the next several days. That’s okay. Expect complaints.

MedicationThe doctor is usually required to discuss medication changes with you prior to implementing anything. If your child already has a psychiatrist, make sure the inpatient doctor is in contact throughout the stay. Besides knowing your child better than the inpatient doctor, your child’s psychiatrist will also be responsible for monitoring the effects of any medication changes over the long haul, so communication is important.

Things you will want to ask about medications (and take notes about):

- What is the doctor’s thought process behind choosing this medication? What alternative medications are there? If you have family members on similar medications or with similar problems, tell the doctor what meds have been effective and which have been a disaster. There’s no guarantee your child will respond to meds in the same way, but when you have a range of options, it’s worth choosing the one that worked for others in your child’s genetic pool.

- How long it will take before the medication kicks in? A few psychiatric meds are effective on the same day. Many take a good amount of time to take effect. Antidepressants, for example, may not reach full potency for 4-6 weeks. What you want to know is what to expect and when. You may also want to ask what happens if the doctors don’t see that effect. Because changes might not be visible until after your child leaves the hospital, make sure your child’s outpatient psychiatrist is included in medication decisions that are made while your child is in the hospital.

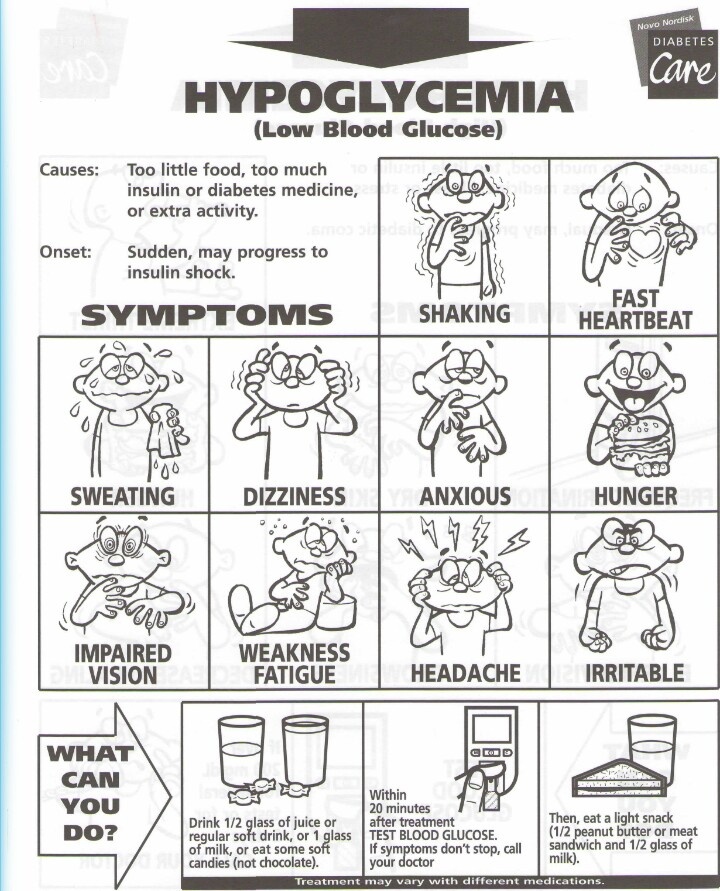

- What are the common side effects? How long do they tend to last? Many side effects pass after a while, but some don’t. Sleepiness, for example, is usually more of a problem in the first week or two. Other medications are notorious for weight gain, so speak up if diabetes runs in your family. You should also be told about any dangerous but rare side effects, when these are likely to show up, and what they look like. Lamictal, for example, causes a rash in a small percentage of cases that can be very serious.

Keep good records of what medications your child is on, when dosages change, and any notable changes in behavior.

Coping while your child is an inpatientYou are likely to have many intense feelings about having a child in a psychiatric hospital. Please, allow yourself to feel them all. All of them are real — including shame, guilt, fear, anger, sadness, and relief — and you will be better able to help your child if you process your own emotions. Your partner’s mix of feelings will undoubtedly be different than yours. You’re both allowed to feel what you feel. With whatever shred of emotional margin you have, be kind to each other, for you are each hurting in your own way.

Your partner’s mix of feelings will undoubtedly be different than yours. You’re both allowed to feel what you feel. With whatever shred of emotional margin you have, be kind to each other, for you are each hurting in your own way.

No matter what thoughts and feelings are bumbling their way through your mind, there is one thing you will need to tell yourself over and over again: your child is SAFE. This, at least, is good.

Putting on your own oxygen maskNow that your child is safe, it’s time to take care of yourself. By all means, take a day or two to fall apart and give vent to your feelings, but after you’ve gotten your sea legs back on, you must, must, must make use of this time to replenish yourself.

It is not disrespectful of your child’s pain to do something that nourishes your heart and soul. You matter, too. You have been through a horrific ordeal. And here’s a fact: your kid is coming back. You need to use this time to breathe and grow stronger because it ain’t over yet. Call your own therapist, consult with your pastor, and get a pedicure. Do whatever makes you more resilient and adds energy or perspective to your life. Give yourself permission to go out with a friend, laugh, get your hair cut, or shoot pool with a buddy. Go for that long run, have a glass of wine with your bestie, or take a long walk in the woods. Whatever gives you oxygen.

Call your own therapist, consult with your pastor, and get a pedicure. Do whatever makes you more resilient and adds energy or perspective to your life. Give yourself permission to go out with a friend, laugh, get your hair cut, or shoot pool with a buddy. Go for that long run, have a glass of wine with your bestie, or take a long walk in the woods. Whatever gives you oxygen.

Note that what rejuvenates you may be different than what you normally do to relax. Often what we do to wind down is numb ourselves with entertainment. That is anesthesia, not oxygen. Oxygen is the stuff that makes us stronger and gets our blood pumping again. Whatever makes that happen for you, do it.

Phone calls, anger, and distressAny guilt or worries you have about having your child in the hospital may be compounded by how they react to being there. Kids often feel ashamed, confused, and scared about being in a mental health facility. Because they are kids, they are likely to take their feelings out on the person they love the most, the person who is safest: you.

You will not be the first parent to be called the worst mother in the world, nor the last to be on the receiving end of a blistering “How could you do this to me?” Don’t take it personally, even if it’s addressed to you. Regardless of your fear (and your child’s assertion) that they’ll hate you for the rest of her life, they probably won’t. In fact, they probably won’t even remember the details of this stay any more than you have a clear memory of being in labor. They will remember that they suffered, and that’s about it. So when you receive that tenth venomous phone call or hear yet another heart-wrenching plea to get them out of there, breathe.

You can try to reason with your child, but don’t expect to get far. Remember, they’re not entirely themselves right now. And logic is rarely effective at de-fanging emotion, anyway. You’ll probably make the most progress by acknowledging and empathizing with their underlying feelings:

“It sounds like you’re really scared. ”

”

“You must be really angry that you have to be there.”

“You sound miserable. I’m so sorry it’s so rough.”

You’ll know you’re on the right track when you get a skin-removing response like, “OF COURSE I’m miserable! Do you actually expect me to be happy here?”

Breathe. Respond to your child’s feelings instead of reacting to the words. Keep going with the validation: “Aww, I’m sorry it sucks so much. I sure wish there were a better way, but there isn’t.”

If you’re too fragile to manage this approach (or the calls simply get to be too much for you), talk to nursing staff about limiting phone access. Alternatively, don’t pick up every call. You don’t have to “be there” for your kid every single hour of the day. It’s okay to set limits. Healthy, even.

Running interference on the unitIf you’ve had experience with other types of hospitals, you know that even in good facilities, it’s possible to encounter an overbearing nurse, a doctor who doesn’t listen well, or some sort of aggravating glitch in care. To get the best care possible, you will have to advocate for your child.

To get the best care possible, you will have to advocate for your child.

There are three obstacles to advocating well.

- Your own emotions are running high. You will need to use caution to avoid overreacting or jumping to conclusions. If your child relates an event that has distressed him or seems to have been handled badly, take notes on his version of what happened. Remind yourself that your child is not well, and his perception of what occurred may not be accurate. This will help you approach staff with an open mind. Questions like, “My son seems upset about what he says took place with _______________. Can you tell me about that?” are going to get a more honest reply than if you bluster in with something accusatory.

- You don’t know how this particular system works. Frankly, your best bet is to fake it. Be pleasant, form alliances with as many staff as possible, get to know people by name, and dress in respectable clothes when you visit.

If you are a single mom, bring a man to the family meeting: stupid as it sounds in this day and age, it makes a difference. Be a reasonable human being. Take lots of notes. You won’t figure it all out, but you’ll eventually grasp some of it. If you have a concern and you’ve spoken up about it several times and still aren’t getting a response, put it in writing. You may need to quietly ask one of the staff members you’ve befriended how to get X to happen or who is in charge of Y. If you are getting stonewalled, push it up the administrative chain.

If you are a single mom, bring a man to the family meeting: stupid as it sounds in this day and age, it makes a difference. Be a reasonable human being. Take lots of notes. You won’t figure it all out, but you’ll eventually grasp some of it. If you have a concern and you’ve spoken up about it several times and still aren’t getting a response, put it in writing. You may need to quietly ask one of the staff members you’ve befriended how to get X to happen or who is in charge of Y. If you are getting stonewalled, push it up the administrative chain. - Staff members vary in how responsive they are. Some will be caring and proactive, some will be okay, and you may encounter a few who seem to be phoning it in. (Your child will undoubtedly have opinions on who falls in which category.) The most important consideration here is that any human connection you create with staff is a good thing. The more you can get the empathy going, the more likely it is that people will be kinder.

If you have a partner, divvy up who will play the bad cop and who will be the good cop. (These roles can change, by the way, depending on which shift you’re dealing with and which of you has developed a rapport with a given staff member.)

If you have a partner, divvy up who will play the bad cop and who will be the good cop. (These roles can change, by the way, depending on which shift you’re dealing with and which of you has developed a rapport with a given staff member.)

As with any other type of hospital visit, you will find it easier to figure out what is going on if you take good notes during each meeting or after every conversation.

Getting ready to go homeIt will happen at just about the time you’re starting to get the hang of this inpatient thing: They’ll start talking discharge. Be forewarned that the key determinant of when your child is released is what your insurance company will pay for. You may or may not agree that your child is ready to come home. Usually, the discharge discussion takes place several days or even a week before the actual discharge.

If your initial reaction to the news is a screaming, “Nooooo!” you will want to pause and examine what’s going on in your head. You may suddenly remember how bad things were before the hospitalization and feel insecure because you don’t know what life will be like in the next phase. Take a bit of time to process that.

You may suddenly remember how bad things were before the hospitalization and feel insecure because you don’t know what life will be like in the next phase. Take a bit of time to process that.

Then again, some of your reactions to discharge planning may be spot-on intuition that your child truly isn’t ready. This, too, merits examination. Make sure you articulate any specific concerns to the doctor, especially if, in your private conversations with your child, they have indicated that they still want to kill themselves or you suspect your child is lying in order to get out.

Some parents become upset because the hospital wants a longer stay than feels strictly necessary. Ask why they want this. Common reasons are that a follow-up plan of care isn’t in place yet or that the doctors feel it isn’t safe to discharge your child until she has met certain conditions.

Before you bring your child homeIf your child was suicidal or made an attempt, you will want to ask how much of his new medication constitutes an overdose. Yes… ouch. But this is better to know than not know. Ask this several days before discharge because you may need to buy a lockbox or safe in which to store medication. You’ll also need a medication dispensing tray (available in any pharmacy) to set up a week’s worth of medication at a time. You don’t want to retrieve bottles multiple times a day because the more you open and close a lockbox, the greater the odds are that you’ll leave the key somewhere, or your child will see the combination.

Yes… ouch. But this is better to know than not know. Ask this several days before discharge because you may need to buy a lockbox or safe in which to store medication. You’ll also need a medication dispensing tray (available in any pharmacy) to set up a week’s worth of medication at a time. You don’t want to retrieve bottles multiple times a day because the more you open and close a lockbox, the greater the odds are that you’ll leave the key somewhere, or your child will see the combination.

Ask if it’s safe to leave a tray with a week’s worth of medications out and accessible. Believe it or not, the doctor probably won’t know the answer off the top of their head unless the medication is particularly potent. If it’s dangerous to leave a week’s worth of medication out, buy a tray with detachable compartments that allow you to take a day’s worth out at a time. That way, you can organize the whole week, keep the bulk of it in the lockbox, and take out only a single day’s medication.

If your child has been suicidal or made an attempt, while your child is still hospitalized, do a clean sweep of your home, and especially his room. Hopefully, the doctors have told you what method of a suicide your child was contemplating. This will help you prioritize what to remove or look for. Lock up high-risk items like firearms, all prescriptions (including your own), and over-the-counter medications like Tylenol and aspirin. Remove poisons (including toxic cleaning products), sharp objects like razors and knives, and large plastic bags. You will also need to wrestle with how to make sure that for the next few weeks, your child is not left alone for more than very short periods of time at home.

If you suspect your child has hidden something dangerous (sharps, medications, illicit drugs) but you still can’t find it, Google “best places to hide ____ in your bedroom.” Chances are your kid has visited that page ahead of you.

For a more comprehensive list of steps to take to “sanitize” your home, check the Grief Speaks website.

Get the discharge instructions that tell you what to do, and be sure to sign a release saying you’d like the discharge summary when it is ready and to whom you want the discharge summary sent. If your child was given any kind of psychological or ed-psych testing while on the unit, make sure to get a copy of those results before leaving, too.

Hospitalization of children and adolescents

Instruction

According to the rules for hospitalization of children and adolescents

in GBUZ KKPN

Regulatory documents when sent to hospitalization and registration for inpatient treatment: 900

1. Federal Law of November 21, 2011 No. 323-FZ “On the Fundamentals of Protecting the Health of Citizens in the Russian Federation”

92g. No. 3185-1

3. Comments on the legislation of the Russian Federation in the field of psychiatry.

Documents for submission :

. If necessary, hospitalization on an urgent basis, the direction is drawn up by a psychiatrist of the consultative and reception room. Parents have the right to self-refer.

If necessary, hospitalization on an urgent basis, the direction is drawn up by a psychiatrist of the consultative and reception room. Parents have the right to self-refer.

2. Complete vaccination history of the patient , certified by the personal seal of the doctor who issued the document. In the absence of certain vaccinations, the reason is indicated. The record “no vaccination record” is made only in cases where it is not possible to restore medical records.

3. Certificate from medical organizations districts, city or medical office of the educational institution about the absence of patient contacts with infectious patients.

- Valid for 3 days from the date of issue to hospitalization.

- The date of issue is written legibly, corrections are not allowed.

- On the certificate are required: surname, initials and signature of the person who issued the certificate (for a doctor - a personal medical seal) and the seal of the institution.

4. Certificate of past infectious diseases (it is desirable to indicate the year), for diseases preceding hospitalization during the last 6 months - month and year. A note about pediculosis, hepatitis, scabies is required.

- The certificate indicates the date of issue, the surname and initials of the doctor or paramedic who issued the document, the personal seal of the doctor, the seal of the institution.

5. Desirable characteristic from an educational institution.

- The full name of the institution, its profile, the child's education program, the name of the person who issued the characteristic, the date of issue, the stamp of the institution are indicated. For patients referred to a hospital to resolve the issue of disability registration, a photocopy of the characteristics for MSEC is required.

6. Outpatient medical record containing information about the presence of chronic comorbidity or a detailed extract from it from a pediatrician or a "narrow" specialist - about the development, pathology, examinations, dynamics of the condition, ongoing treatment and the status of the patient at the time of issue extracts with recommendations for further tactics.

For routine hospitalization of sexually abused or sexually abused children and adolescents , the following documents are also required: an examination by a gynecologist / proctologist, venereologist, with a conclusion: “may be in a children's team”, a personal seal of the doctor and the date of the examination are required. Tests for HIV and RW. Upon contact of a hospitalized person with a patient with tuberculosis, a certificate from a phthisiatrician is required on the possibility of staying in a children's team.

Planned hospitalization of children under 15 years of age is carried out with the consent of the father / mother or guardian. Children - dependents of the state - at the request of the administration of the educational institution where the child is being brought up or is kept. The mother / father of the child during hospitalization present their passports, and the guardian their passport and documents confirming the guardianship of this linden over the hospitalized child.

In the absence of a father/mother, a guardian during the hospitalization of a son/daughter/guardian, planned hospitalization of a child is possible only if they have a notarized power of attorney for the person accompanying the child. The power of attorney must transfer to the specified person the rights (provided for in Article 46 of the Code of Civil Procedure of the Russian Federation) to be the legal representative of the child during his hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital and for the duration of his stay in the hospital. At the same time, the legal representative accompanying the child must have an identity document with him. In the case of a parent or guardian staying in a medical organization for inpatient treatment, the power of attorney in the prescribed form and the signature of the parent is certified by the head physician of the hospital.

For a representative of a state institution accompanying a child for hospitalization, a power of attorney is given by the head of this institution. The date of issue of the power of attorney, the surname and signature of officials and the seals of institutions are required.

The date of issue of the power of attorney, the surname and signature of officials and the seals of institutions are required.

Emergency hospitalization of children under 15 years of age is issued by a commission of psychiatrists (3 people) without the above documents. Measures are immediately taken to search for the legal representatives of the child and collect the necessary medical documentation.

Adolescents from 15 to 18 years of age consent to planned hospitalization themselves.

Emergency involuntary hospitalization of patients of this age group is carried out according to the established rules in accordance with legislative documents.

Basic rules for filling out a referral for hospitalization to the GBUZ KKPND:

Referrals are transferred to the registry of the dispensary of the GBUZ KKPND by a doctor or nurse of the district or a psychiatrist of the boarding school.

In the hands of parents or guardians of district patients, the referral is issued only in a sealed form, in this case the diagnosis of mental illness is replaced by a code according to the International Classification of Diseases - 10.

The following points must be reflected in the referral for hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital:

If the parents or guardian live separately from the child, if the address of the child's permanent place of residence at registration does not match the address of his actual residence, there are several places of residence, etc., all addresses and telephone numbers that are known to the psychiatrist are indicated.

Surnames, first names, patronymics of parents (the parent with whom the child lives) or guardians are also written.

In the column "place of work of the patient" are indicated:

- for those attending preschool institutions - his number and his specialized profile - for those not attending preschool institutions - the word "unorganized" is written. - for those attending an educational institution - its number, specialized profile, class number and the program for which the patient is studying are indicated.

- for homeschooled or individualized students - a detailed entry is made such as "homeschooling for the 4th grade support program."

In the column "sent to the hospital initially, again" the required information is underlined. The date of the previous hospitalization is indicated if the patient is re-admitted. In the "brief history of the disease" section, all information about the patient, his illness is written briefly, but succinctly. It reflects the essence, the information that the doctor of the admissions office needs to resolve the issue of hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital, and the psychiatrists of the department - to understand the dynamics of the disease process and develop treatment tactics.

It reflects the essence, the information that the doctor of the admissions office needs to resolve the issue of hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital, and the psychiatrists of the department - to understand the dynamics of the disease process and develop treatment tactics.

It is necessary to reflect the dynamics of the mental state during treatment. Indicate drugs, daily dose, duration and number of courses, tolerability of drugs. If the treatment was not carried out with a long-term observation by a psychiatrist and there are indications for therapy, then the reason is indicated (refusal of the patient, relatives, somatic pathology, etc.). If at the time of issuing the voucher the patient receives medical treatment, then the voucher must indicate; from what time one or another drug has been received, single dose, method and brevity of administration / administration, tolerability. The effect of outpatient therapy.

It is obligatory to indicate the time from which the child is ill with mental illness or from what time the parents / guardian / employees of the state educational institution consider him ill or notice deviations in his behavior, study, mood, etc. It is written whether he is on a dispensary registered with a psychiatrist or under consultative and therapeutic supervision and from what time. If the day of the first appeal to a psychiatrist coincides with the day of writing the referral, then it is indicated “they turned to a psychiatrist for the first time ....... (day, month, year)”.

It is written whether he is on a dispensary registered with a psychiatrist or under consultative and therapeutic supervision and from what time. If the day of the first appeal to a psychiatrist coincides with the day of writing the referral, then it is indicated “they turned to a psychiatrist for the first time ....... (day, month, year)”.

Reflects the use of psychoactive substances (alcohol, drugs, inhalation of toxic substances, etc., smoking), sexual violence, sexual life, sexual deviations.

Health complaints are indicated:

- subjective: presented by the patient himself.

- Objective: presented by the legal representatives of the child on his health.

The description of the somatic status should contain the patient's complaints, deviations in the somatic sphere at the time of issuing the referral. The skin and mucous membranes are described. If there is information about homosexual relationships, the anus is examined, the results are recorded in the direction. Control of blood pressure and temperature. Results of examination for pediculosis. Contact with a tuberculosis patient, permission for hospitalization in the children's department is confirmed by a certificate.

Control of blood pressure and temperature. Results of examination for pediculosis. Contact with a tuberculosis patient, permission for hospitalization in the children's department is confirmed by a certificate.

In the presence of concomitant chronic somatic diseases, the patient is warned about the need to present an outpatient card of a somatic patient during hospitalization, or an extract from it with an examination, these examinations, treatment results and recommendations from medical specialists. At the same time, the doctor writes a diagnosis of a chronic concomitant somatic disease in the voucher.

If the severity of the somatic condition prevails over mental manifestations, then the child is treated for somatic pathology in a hospital corresponding to the profile of the disease or receives treatment on an outpatient basis (at the discretion of the attending specialist or pediatrician), and after achieving stable remission/compensation, it is planned to undergo inpatient examination and treatment of mental illness in the GBUZ KKPND.

Cases of emergency hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital of a seriously somatic patient are coordinated by a psychiatrist with the head of the children's department and the deputy chief physician for the medical unit of the GBUZ KKPND.

Neurological status - deviations in the neurological sphere, concomitant chronic neurological pathology are reflected. In the presence of a neurological pathology concomitant with a mental illness, an extract from a neurologist is required for referral to a psychiatric hospital with an indication of the diagnosis, the results of the examination, the dynamics of the condition, the treatment being carried out, recommendations on the tactics of management and drug therapy at the time of inpatient treatment at the KKPND GBUZ.

Prevalence of neurological pathological symptoms over mental disorders - indications for treatment in a neurological hospital, outpatient therapy (by the decision of specialists - neurologists), with further planned examination and treatment in the GBUZ KKPND.

Cases of emergency hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital of patients with severe deviations in the neurological sphere are agreed with the head of the children's department and the deputy chief physician for the medical unit of the GBUZ KKPND.

The mental status should briefly but succinctly reflect the mental state of the patient at the time of issuing a voucher for inpatient treatment, highlighting the main symptoms and syndromes.

The column “summary of the social survey” describes the housing and social conditions of the child’s residence (what type of housing; separate or communal; comfortable or uncomfortable; whether a separate room is allocated to the child. Complete family or not; prosperous or not, whether parents abuse alcohol, the child is neglected or not, keeping a brothel, etc. Deprivation of parental rights. Guardianship.)

A child must be accompanied to hospitalization by a father/mother/guardian or a legal representative - an employee of a state institution - by whom specifically, last name, first name, patronymic, who the child is related to.

Psychiatric diagnosis and code or code only, if the referral is issued to the hands of the father/mother/guardian in a sealed form.

A psychiatrist does not have the right to give a referral for hospitalization without examining the patient.

A child under 15 years of age is examined by a psychiatrist only with the consent of his legal representatives, they also agree to the hospitalization of the child in a psychiatric hospital of the GBUZ KKPND - when writing a referral orally to a psychiatrist (the district psychiatrist indicates consent at the end of the tour) and in writing when the patient is hospitalized .

Urgent involuntary hospitalization in a psychiatric hospital is carried out without the consent of the legal representatives of the child and adolescent from 15 to 18 years of age, if indicated, in accordance with the established procedure.

After writing a psychiatric diagnosis and a concomitant somatic diagnosis, the psychiatrist indicates for what purpose and for which issues the patient is referred for planned inpatient treatment. Emergency hospitalization is justified with reference to the "Law on psychiatric care and guarantees of the rights of citizens in its provision" dated 1992 years old The psychiatrist puts his medical seal and signature.

Emergency hospitalization is justified with reference to the "Law on psychiatric care and guarantees of the rights of citizens in its provision" dated 1992 years old The psychiatrist puts his medical seal and signature.

The date of issue of the referral is required. No abbreviations other than generally recognized ones (CNS, EEG, ECHO EG) and corrections are allowed.

"We can send your daughter to a mental hospital." How teenagers end up in psychiatric hospitals and what happens to them - MBKh media

Teenagers end up in psychiatric hospitals when their parents (or themselves, if they are over 15 years old) sign a consent to the examination. Further, the hospital can go to court - and the troubled teenager is provided with a couple of months of heavy antipsychotics in an overcrowded ward without door handles. The story of a girl who was sent to a mental hospital for reading about Columbine attracted public attention and caused a lot of talk. MBKh Media shares bad news: this is a common practice in Russia, children are sent to such institutions by parents tired of whims, strict orphanage teachers and police officers.

On August 24, the FSB searched the house of the family of 14-year-old schoolgirl Alena Prokudina in Krasnoyarsk. The security forces seized a toy bow, an air gun and Alena's diaries. After that, with the consent of her parents, the girl was taken for examination to the Krasnoyarsk Regional Psychiatric Dispensary No. 1 with a hospital. Alena was subscribed to the VKontakte public dedicated to Columbine. (In 1999, a massacre occurred at the Columbine School in the United States. 13 people died - "MBH media" ).

In total, nine schoolchildren were sent to the hospital in the Krasnoyarsk region because of their subscription to this group. According to the security forces, the teenagers who were in it were preparing for "active actions."

Alena Prokudina. Photo: Alena Prokudina / Vkontakte “Alena 100% did not plan anything. Many teenagers are interested in (the topic of Columbine, - MBH Media) , this is a hot topic among schoolchildren. They are wondering why it happened, what was the reason, ”Lena’s mother Olga Pronina told MBKh Media. According to her, the girl talked about her interests: “It was in the spring, we talked about how to avoid such cases, how important it is to treat all peers in a good way, how to peacefully (without aggression) get out of a situation where a child is being bullied in school. Alena is generally concerned about acute social topics, she is a sympathetic and kind child.

According to her, the girl talked about her interests: “It was in the spring, we talked about how to avoid such cases, how important it is to treat all peers in a good way, how to peacefully (without aggression) get out of a situation where a child is being bullied in school. Alena is generally concerned about acute social topics, she is a sympathetic and kind child.

How children end up in psychiatric hospitals

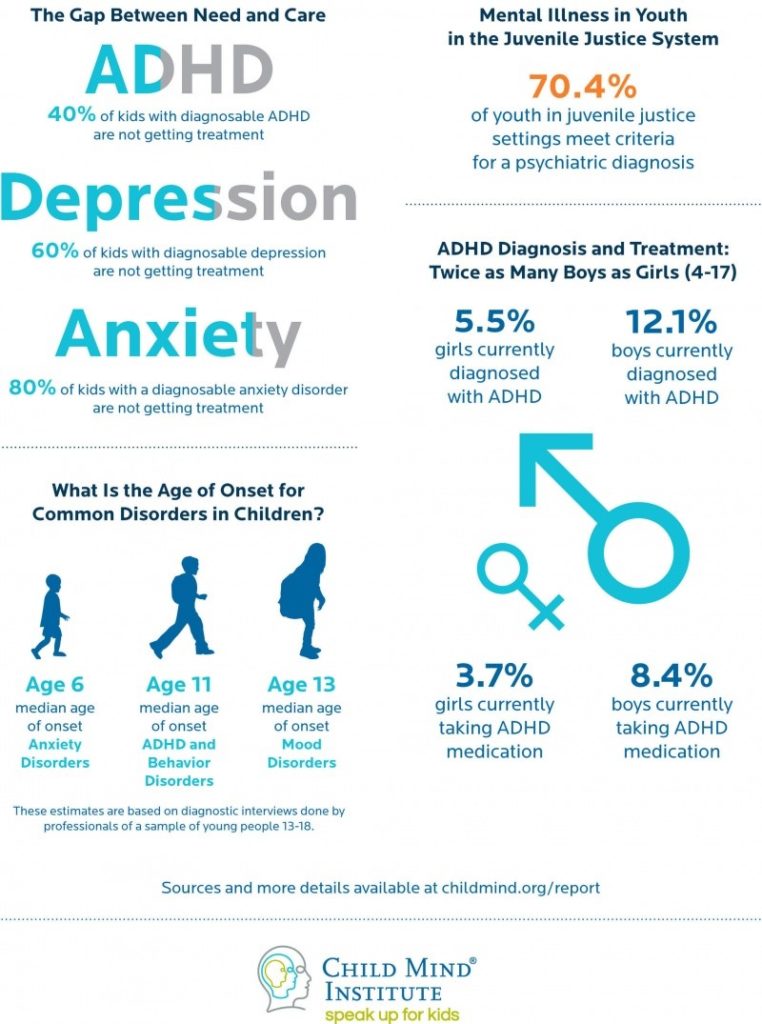

A child is referred to a psychiatric hospital with parental consent if he or she has symptoms of a mental illness or borderline mental illness, or if the illness has already been diagnosed. In some cases, adolescents are sent for examination from the military registration and enlistment office - for examination and diagnosis.

Also, by court order, children are sent for psychiatric examination in case of committing certain crimes. If the examination came to the conclusion that during the commission of this act the teenager could not understand the meaning of his actions, then he will be sent for compulsory treatment, regardless of age and the decision of the parents.

Children under 15 years of age are hospitalized with the consent of their parents or other legal representatives, adolescents over 15 years of age themselves consent to hospitalization.

“In order for a person to be admitted to treatment, he must have a diagnosis of some kind of mental disorder, and it must worsen so much that it requires inpatient treatment. And in a hospital they can not treat voluntarily. Another thing is that this should be formalized through a special judicial procedure, ”Lubov Vinogradova, executive director of the Independent Psychiatric Association of Russia, told MBKh Media.

Lyubov Vinogradova, Executive Director of the Independent Psychiatric Association of Russia. Photo: from the personal archiveIn this case, the examination can only be voluntary. “A person enters the examination due to, perhaps, a suspicion of a mental disorder or some kind of complaint,” Vinogradova clarifies.

Involuntary treatment is given when a person poses a danger to themselves and others, or if leaving without mental health care would cause significant harm to the person. The anamnesis should already describe a mental disorder. In this case, the hospital can apply to the court and obtain permission for treatment.

The anamnesis should already describe a mental disorder. In this case, the hospital can apply to the court and obtain permission for treatment.

Elizaveta Kalinkina first came to the Child Psychiatry Rehabilitation Center in St. Petersburg in 2018, when she was 13 years old. “I ran away from home after several episodes of violence. In the end, they found me and from the police department I was brought first to a regular hospital, and from there to a psychiatric hospital. Until the age of 15, if there is parental consent, it can be considered that hospitalization is voluntary, but no one asks the child.”

Lisa spent two months there complaining to her mother that the staff beat her and abused her. “She didn’t care, she said that I was to blame,” says the girl.

Ekaterina Stepanenko (name changed) ended up in a mental hospital in a similar way. At the age of 17, after a quarrel and fight with her mother, she ran away from home and stayed with a friend. When she returned home the next day, she had a tantrum. She sent a friend an ambiguous message, after which the phone sat down. The guy decided that Katya could do something with himself and called an ambulance.

She sent a friend an ambiguous message, after which the phone sat down. The guy decided that Katya could do something with himself and called an ambulance.

The girl recalls that the paramedics were rude to her, when they saw traces of self-harm, they threatened that she would not find a job. Katya was taken to the hospital. In the emergency room, the doctors were “good and adequate,” the girl believes. They offered to go to the hospital, Katya herself agreed to be hospitalized - she was already 17 - and only then realized what a mistake it was. “All this happened to a terribly tired teenager, I just sat down, looking down, and then agreed to lie down,” she recalls.

She spent only a week in the hospital. Later, the girl found out that this happened after a conversation between her parents and the head of the department - the girl was transferred to outpatient treatment. “As far as I understood, they were not going to let me go so quickly. With a suspicion of a suicide attempt, they put them for three months - in any case, others were in my hospital for so long, ”says the girl.

The primary environment is reflected in the psyche of a teenager, and often children in deviant families get mental disorders, for example, they are depressed. Sometimes families themselves try to get rid of the child by sending him to the hospital. “It happens that parents simply do not want to take care of their children, especially those who already have some kind of disorder. For example, there was a specific case when an alcohol-addicted mother brought her daughter to hysterical states, called an ambulance and sent her to a psychiatric hospital,” a social worker from one of the large psychiatric hospitals, who wished to remain anonymous, told MBKh Media.

Alena's mother, Olga Pronina, succumbing to the persuasion of the security forces, first agreed to hospitalization, but later withdrew it. However, this did not help bring her daughter home. “To the refusal in an electronic form, which we sent to all available e-mails of the hospital, we were answered with an invitation to talk with doctors the next day. At this conversation, they refused to return the child, arguing that “the documents need to be completed”, “according to the law, the child can be kept for another three days after refusing voluntary hospitalization.” After that, we again wrote a refusal and personally brought him to the hospital. He was accepted - they put a seal - but the child was not given away, ”says Olga.

At this conversation, they refused to return the child, arguing that “the documents need to be completed”, “according to the law, the child can be kept for another three days after refusing voluntary hospitalization.” After that, we again wrote a refusal and personally brought him to the hospital. He was accepted - they put a seal - but the child was not given away, ”says Olga.

After the parents tried to take their daughter home, the dispensary went to court, which allowed Prokudina's involuntary hospitalization for an indefinite period.

Lyubov Vinogradova noted that although legally everything was done correctly, most likely Alena's hospitalization was not justified. As a result, the girl was discharged two weeks after hospitalization - on September 8. The executive director of the NPA notes that, judging by the fact that Alena was discharged fairly quickly, the girl's condition did not require involuntary measures. She also indicated that Prokudina's family is well-off and she has a good relationship with her parents and sister. “If a condition requires involuntary inpatient treatment, then it takes a month, and sometimes more (…). That is, the situation of this girl is ... unusual, so to speak, ”the psychiatrist believes.

She also indicated that Prokudina's family is well-off and she has a good relationship with her parents and sister. “If a condition requires involuntary inpatient treatment, then it takes a month, and sometimes more (…). That is, the situation of this girl is ... unusual, so to speak, ”the psychiatrist believes.

How children are forcibly left in the hospital

Grigory Gershenovich, head physician of the Krasnoyarsk dispensary, personally filed an application for involuntary hospitalization of Alena. It says that the decision was made "after a personal examination of the girl and in connection with her" "destructive behavior"," said Alena's lawyer Vladimir Vasin. Also, a certificate from the E Center was submitted to the court, stating that Prokudina "is an adherent of the subcultural (destructive) ideology of Columbine."

“I think both the judge and the doctors were definitely 'pressed'. By the way, perhaps to a lesser extent on the judge than on the doctors. For a judge, this is a typical situation - he first of all listens to the conclusion of a medical institution that applies for hospitalization, ”explained Lyubov Vinogradova.

For a judge, this is a typical situation - he first of all listens to the conclusion of a medical institution that applies for hospitalization, ”explained Lyubov Vinogradova.

Prokudina's defense prepared for the trial the opinion of her specialist, Professor of Medical and General Psychology Vladimir Mendelevich. The psychiatrist analyzed the conclusion of the medical commission and found that the schoolgirl did not behave "inadequately and maladaptive." The professor noted that “no psychotic symptoms, disorders of thinking, perception, emotions, will, consciousness and self-awareness have been identified and described. That is, none of the diagnostic criteria for a mental or behavioral disorder is given in the mental status.

According to Mendelevich, the commission of psychiatrists who examined Alena did not describe any mental disorders, and all conclusions are theoretical and based on data received from others. He clarified that the IPA did not describe the danger of the teenager to himself and others, although the commission decided that if the girl was not hospitalized, her personality characteristics would worsen and there would be an immediate danger of auto- and hetero-aggression. He called the situation "a gross violation of the principles of psychiatric diagnosis."

He called the situation "a gross violation of the principles of psychiatric diagnosis."

The court attached Mendelevich's opinion, but probably did not even consider it: according to the lawyer, the decision was made in five minutes. Olga Pronina was not allowed to speak in court. Later, she told MBKh Media that the description from the PND does not at all coincide with the real behavior of her daughter: “Alyona was always treated well at school. Alenka was not a tomboy and a ringleader, she was not some kind of outcast. I communicated well with two friends: we walked together, went to the cinema. I also got along with the teachers, there were never any conflicts. ”

Professor of medical and general psychology Vladimir Mendelevich. Photo: WikiCommons Vinogradova notes that now it is not so easy to send a healthy person for treatment to a psychiatric hospital. “This is not such a frequent case, but, unfortunately, recently we are facing this more and more often. Moreover, the initiators are our valiant bodies, who believe that this is a good way to solve certain issues and put pressure on psychiatrists. Which, unfortunately, do not always show sufficient resistance and resistance.

Which, unfortunately, do not always show sufficient resistance and resistance.

According to Liza Kalinkina, there were 40-50 teenagers in her department, and most of them were there for no apparent reason: “For quarrels with parents, for absenteeism from school, for running away from home, or simply because the child was tired and decided to "pass". By the way, children from orphanages are also sent to psychiatric hospitals as a punishment.” When the girl was discharged from the hospital, she saw that her diagnosis was “elements of antisocial behavior - leaving home”, although this is not in the international classification in ICD-10.

“My attending [doctor] told me that I would be discharged when I corrected my behavior. They just wanted me to start obeying my parents, and my words about domestic violence were simply ignored, ”says Lisa.

Also, according to the girl, the parents could pick up the child from this center at any time by writing a refusal to be hospitalized. “But basically, parents just don’t care, they know about all the conditions, but they think it’s normal.”

“But basically, parents just don’t care, they know about all the conditions, but they think it’s normal.”

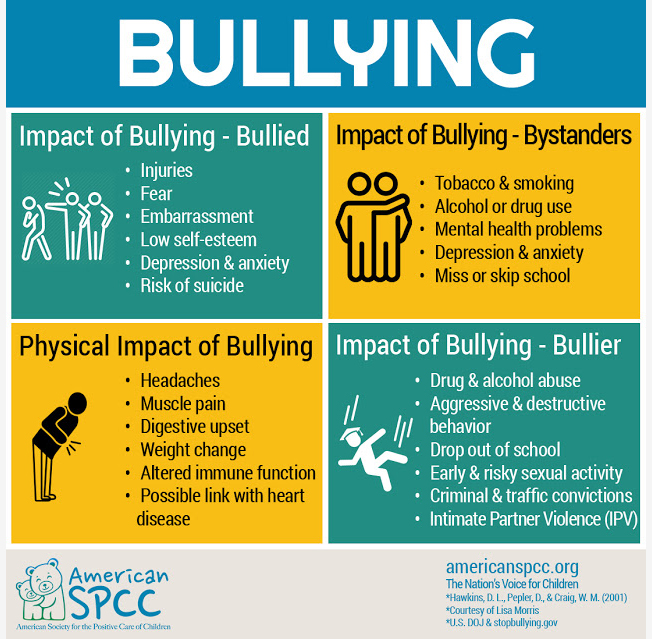

Lyubov Vinogradova suggests that both teenagers and adults are often sent to psychiatric hospitals for intimidation. For any person, and especially for a child, being treated in a psychiatric hospital, and generally losing freedom for a while, is a huge stress.

According to Olga Pronina, some of the children who were taken to the PND for examinations, like her daughter, were released earlier because their parents did not attract media attention. She suggests that in this way they decided to “punish her, show who has power.”

Elizaveta Kalinkina. Photo from the personal archive Also in St. Petersburg, the police threatened to send 15-year-old Liza Kalinkina to a psychiatric hospital because of a picket in support of the residents of Khabarovsk, to which she came with a blank sheet of paper. “Initially, I was detained when I was walking and talking with friends, allegedly for swearing in a public place. They said that you need to go to the department, give a written explanation, after which they will let you go, ”said Kalinkina.

They said that you need to go to the department, give a written explanation, after which they will let you go, ”said Kalinkina.

The girl was taken to the juvenile inspector. “She didn’t say anything about the mat, she only tried to find out about the picket. I was initially told that if something happened, they could send me to a psychiatric hospital involuntarily. I said that they had no grounds for this, that I was not a danger to myself and others. They said the police can do anything. And when the mother arrived, she was told the same thing, that “we can send your daughter to a mental hospital, if you want, you can contact us, we will do everything,” she explained.

How children live in psychiatric hospitals

Alena complained about the conditions of detention through her lawyer during her stay in the PND. She said that in total there are 13 people in the ward: nine boys and four girls, but they are only allowed to sleep in underwear, and she was shy. In addition, according to the rules of the dispensary, they need to sleep for 13 hours. Glasses and bottles of water are also prohibited in the institution - you can only drink water from the tap.

In addition, according to the rules of the dispensary, they need to sleep for 13 hours. Glasses and bottles of water are also prohibited in the institution - you can only drink water from the tap.

According to Alena's mother and sister, after the publicity, the conditions of detention in the PND improved: she was allowed to walk with other children, the girls were provided with a separate room.

Lyubov Vinogradova says that according to modern standards, children and teenagers should lie separately from adults. But there are situations when the hospital does not have a children's or adolescent department, and then they are placed in an adult, but they try to allocate a separate ward. This situation is typical for small towns.

Conditions in children's departments of psychiatric hospitals practically do not differ from those in adult departments. Here, again, much depends on the particular institution. The only difference is that teenagers should be provided with education so as not to interrupt schooling, and classrooms adapted for this, as well as playrooms for leisure. The number of staff also differs - more psychologists and teachers should work in children's departments.

The number of staff also differs - more psychologists and teachers should work in children's departments.

The social worker confirms that Moscow psychiatric hospitals have male and female departments, children’s and adults: “Even if possible, teenagers and younger children are also separated, placed on different floors, in different buildings. In general, the usual conditions, as in all hospitals - [door] handles, perhaps, no.”

In the Center for Rehabilitation Treatment, where Elizaveta Kalinkina spent two months, there was a division by sex and in general only girls from 7 to 14 years old were in her department. “The shower was once a week, sometimes they could allow me to wash my hair again. I asked to wash my hair, but they told me that I did not deserve it. That is, elementary hygiene was presented there as something that needs to be earned, ”she says about the conditions.

Because she refused hospital food, she was threatened with being diagnosed with anorexia and being force-fed through a tube. For the same reason, she was not given food from her parents.

“Everyone was given the same pills — a very heavy antipsychotic Truxal. As a punishment, if they did not like how a person behaves, tries to express his opinion, they injected "Aminazin". (…) They didn't tie me up. Once only dragged by the hair to inject "Aminazin". They tied only those who did not control themselves at all, for example, there was a girl who gouged out her eyes with her knees and they tied her up. There was nothing like this anymore, ”recalls Lisa about the methods of treatment.

Katya's hospital from Siberia did not have a children's department. Only a separate female. On the floor were both seriously ill patients and violent patients, who, according to her, were tied with belts. Katya herself was in the ward "with some kind of quiet grandmothers."

“Conditions are terrible, there is nothing to talk about. The nurses are indifferent, but at least they didn’t beat anyone, at least I didn’t see anything like that. They didn’t say what pills they give to drink, they didn’t let anyone call, ”the girl says. - There are no doors to the toilet, this is a psychiatric hospital. But the toilet itself, as well as the shower, is terrible. The mattresses are all pissed. There were no non-walking patients, but I was in the ward with a patient who just walked like herself. The vents do not open, there are bars on the windows. They took me out for a walk once in all the time. ”

The nurses are indifferent, but at least they didn’t beat anyone, at least I didn’t see anything like that. They didn’t say what pills they give to drink, they didn’t let anyone call, ”the girl says. - There are no doors to the toilet, this is a psychiatric hospital. But the toilet itself, as well as the shower, is terrible. The mattresses are all pissed. There were no non-walking patients, but I was in the ward with a patient who just walked like herself. The vents do not open, there are bars on the windows. They took me out for a walk once in all the time. ”

It was only after Katya was discharged that she entered group therapy when she switched to outpatient treatment. In the hospital, she was given one shot of a tranquilizer and was constantly given pills.

Yekaterina believes that, in general, the psychiatric hospital did not make her feel any better, if not worse: “It only made me feel better because I got out of there. It feels like a prison: scheduled walks, asking the nurses for cigarettes, bars on the windows, iron beds.