Bpd lack of empathy

Do People With BPD Feel Empathy? - Empathy and Borderline Personality Disorder

I was diagnosed with Borderline Personality Disorder after years of struggling with various mental illnesses. It was initially a huge relief, a weight off my chest. The validation that I didn’t imagine all of this, that there really was something wrong with me. The comfort in knowing that I was far from alone, almost 1.6% of the population is believed to have BPD. These weird thoughts and feelings, the behaviour I exhibit and never understand, was a symptom of more, and a symptom that many others were feeling. My diagnosis coincided with Rebecca Bunch’s on Crazy Ex-Girlfriend, an incredible twist of fate that fooled me into thinking the disorder could be correctly recognised and discussed.

But just like Rebecca in the episode “Josh is irrelevant”, I decided to google my new diagnosis. And I quickly discovered that:

1. People don’t understand BPD.

2. People hate BPD.

I could dedicate an entire article to why people hate BPD, all the things they say about us, the way even trained psychologists refuse to treat Borderline patients. Maybe one day, I will, when I feel the strength to immerse myself in their cruel assumptions again. But for today, I’ll merely pick up one slice of those assumptions. Because time and time again, I see this question on the internet. I don’t think it is even intended as an insult, but an honest question.

Do people with BPD feel empathy?

Something has led people to doubt whether BPD individuals feel empathy. And it’s okay to ask if you’re genuinely unsure, as at least you’re looking for the answer, you’re not phrasing it as a statement to further tear us down. So let’s find out the answer to this question.

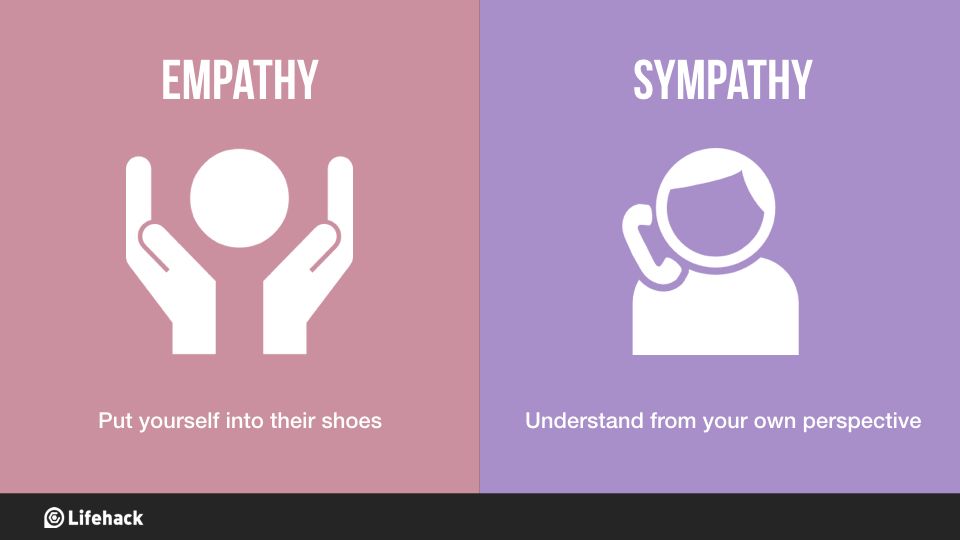

What is empathy?

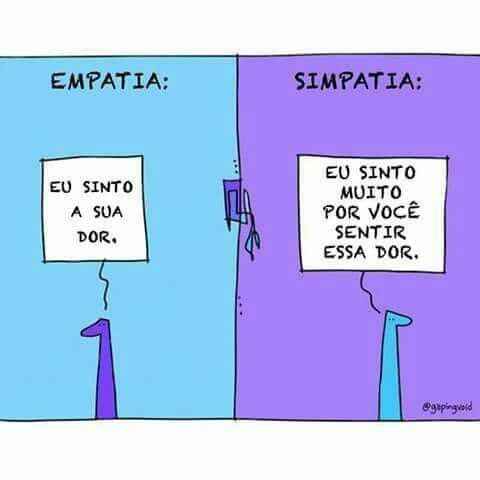

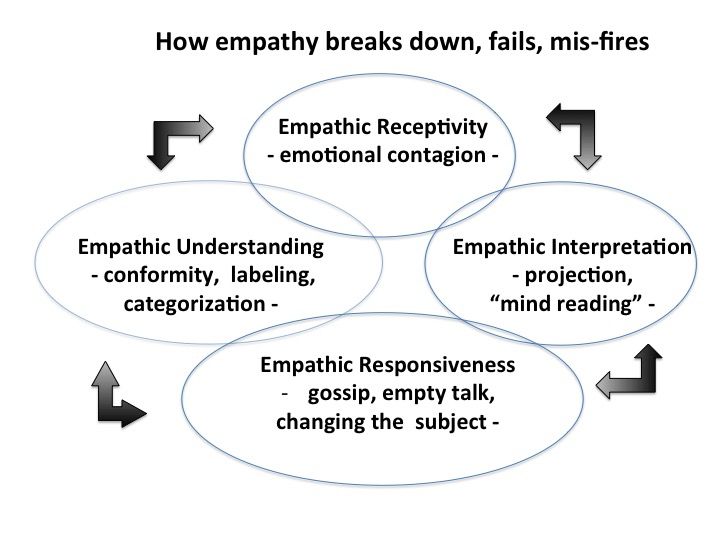

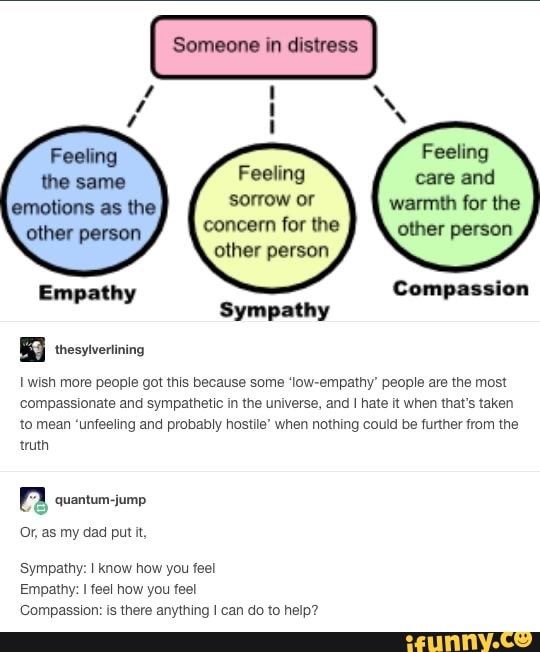

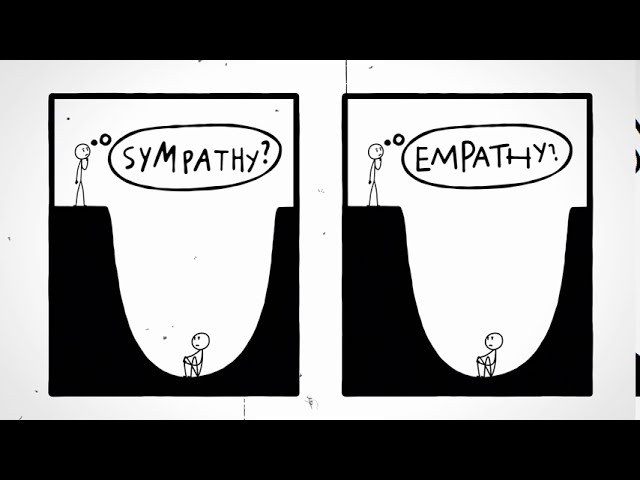

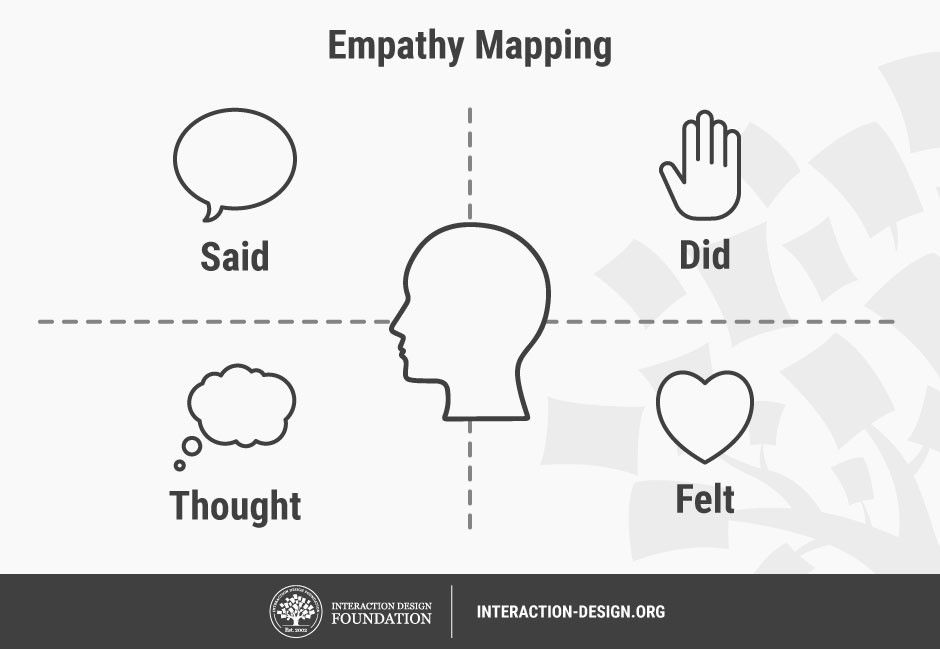

Let’s first get our basics out of the way; what is empathy? Broadly speaking, empathy is the way we react to one another and explains how we conduct ourselves with the world around us (Davis, 1983). Empathy is considered to be the capacity to feel or understand what someone else is experiencing. This is based on their frame of reference, also known as putting yourself in someone else’s shoes.

So if my friend is struggling, I can imagine their pain, feel distressed with them and wish to help them. All of this is part of empathy but is referring to the three different types of empathy, as defined by Daniel Goleman.

1. Cognitive Empathy. This is knowing how they feel and what they might be thinking. It focuses on the recognition of emotion and finding that within your own bank of experiences. It is also known as perspective-taking. So this would be that my friend was just dumped by their girlfriend, I can recognise they are hurting, and I understand that this is a difficult time for them. Maybe I’ve been dumped before and draw upon on that, or I can simply use other experiences of pain and rationality to determine.

2. Emotional Empathy. This is almost the next phase to empathy when you feel their pain. It’s a physical sensation as if their emotions are contagious. My friend is dumped and is sad, and subsequently, I feel sad. I watch a video of an abandoned puppy, I cry and my mood drops.

3. Compassionate Empathy. So I have recognised their pain, I have felt their pain, and now I wish to solve it. I not only feel the person’s predicament, but I am moved to assist them where I can. In our break up scenario, this would probably take the form of arriving at their door with a tub of Ben&Jerrys and telling them they’re better off without that loser!

It could be said that some individuals are more proficient in certain types of empathy, but generally speaking, we consider empathy to be the collection of the three aspects. Cognitive and emotional empathy together aim to create compassionate empathy within an individual. You could look at it as evolutionary, in that it brings us to help others, and survive as a group. John Donne said it best with “No man is an island”.

Why do people think BPD individuals don’t feel empathy?

Now that we know empathy let’s try to set the scene and use our own empathy to understand why individuals could believe this before we investigate whether it is true. I’ll be using general symptoms and traits of Borderline Personality Disorder for this, so there can be individual differences.

I’ll be using general symptoms and traits of Borderline Personality Disorder for this, so there can be individual differences.

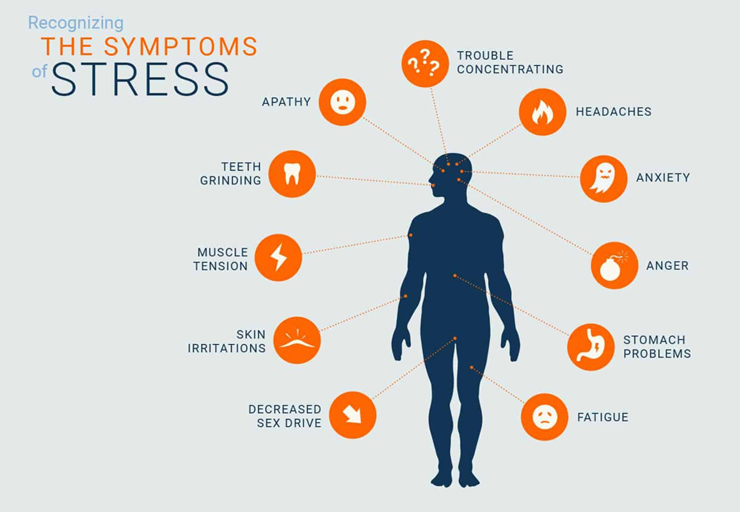

Individuals with BPD are subject to black and white thinking; they are all or nothing. This applies to interests as well as people. They love someone, and within minutes they hate them. This could seem like a lack of empathy, given that they are not trying to understand the other persons situation or reasons for doing so. They are not giving empathy to the moment and instead they make a rash judgement.

They are controlled by their emotions. They don’t take a step back to reflect on the moment. For example, their partner isn’t messaging them while at a party. A non-BPD individual could think that they’re just enjoying themselves and busy, or that their phone ran out of battery. But someone with BPD could jump to conclusions, e.g. They don’t love me anymore! They’re with someone else! They’re feeling guilty for just cheating and avoiding me! If they loved me, they would make more effort to make me feel safe! This was me, time and time again, jumping to conclusions and starting fires from the smallest of timbers.

They don’t consider alternative viewpoints. They feel this way, and so that is the truth. They message their partner when they’re out drinking because they love them and miss them. So if their partner doesn’t do the same, then it means they don’t feel the same way.

Individuals with BPD can do spontaneous things, especially actions that are self-sabotaging. They can use sex to imitate a connection or convince themselves of their worth. They could try to hurt their partner, and ultimately themselves, through being unfaithful or doing things they know that they shouldn’t. Addiction is entangled in BPD. They could say cruel things to push you, to see if you’ll stay, trapped in their fear of abandonment. If you’re the person being hurt by their actions, time and time again, it makes sense why you would even question if they feel empathy. Do they not realise how much they hurt you, or are they choosing to do this anyway?

So do people with BPD feel any empathy?

The million-dollar question - if only!

Yes

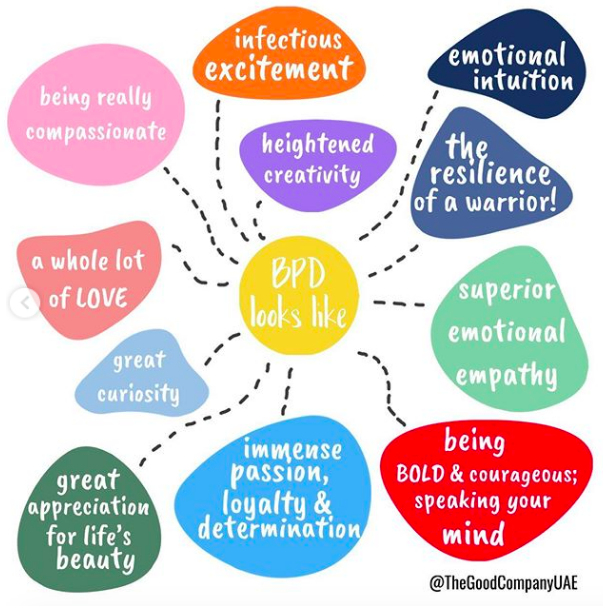

In 1992, the World Health Organisation labelled Borderline Personality Disorder as an individual being “hyper-empathic”. Park et al. found that BPD individuals have certain heightened abilities, and one of these is empathy. In the reasoning for their study, they said the following:

Park et al. found that BPD individuals have certain heightened abilities, and one of these is empathy. In the reasoning for their study, they said the following:

Almost all clinicians who have significant experience with borderline patients are impressed at times with their exceptional ability to sense the psychological characteristics of significant others in their lives, including therapists. (Park et al., 1992)

Individuals with BPD both fear abandonment and have a low sense of self-worth. They will do everything possible to keep you in their life and make up for their lack of worth. They are constantly reading into your smallest behaviours or words. They are over-using their empathy, to make sure that you like them, that you’re not angry at them, that you’re not leaving them.

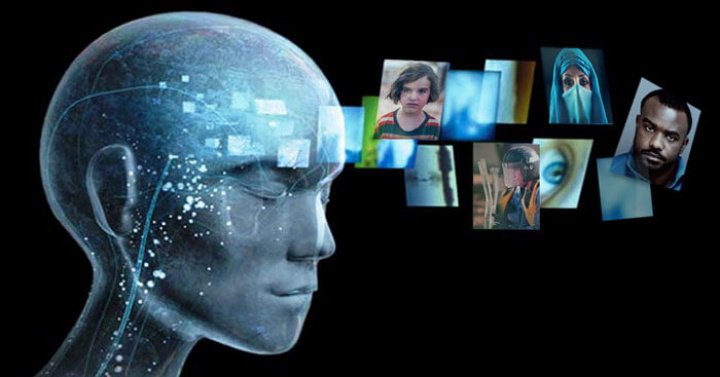

Individuals with BPD actually seem to have an uncanny sensitivity to other people’s subconscious mental content. This includes feelings, thoughts and even physical sensations. This allows them to involve and influence others successfully. Frank and Hoffman (1986) found that BPD individuals displayed a heightened sensitivity to nonverbal cues compared to the non-BPD sample. Fertuck et al. (2012) asked individuals with and without BPD to react to photographs of people’s eyes. They found that individuals with BPD were able to correctly guess the emotions expressed in the eyes more often than others, which displays their enhanced sensitivity to another’s mental state.

Frank and Hoffman (1986) found that BPD individuals displayed a heightened sensitivity to nonverbal cues compared to the non-BPD sample. Fertuck et al. (2012) asked individuals with and without BPD to react to photographs of people’s eyes. They found that individuals with BPD were able to correctly guess the emotions expressed in the eyes more often than others, which displays their enhanced sensitivity to another’s mental state.

This suggests that people with BPD don’t have issues with empathy, or at least with the first two aspects of empathy (cognitive and emotional). They can recognise other people’s feelings and feel the same way, but this might not translate into behaviour. Why? The extreme emotions felt by someone with BPD can be overwhelming, which is why they do self-sabotaging behaviours. You feel so much sadness and guilt for upsetting someone that you self-harm, which only goes to upset that person further when they find out. Or you drink excessively to try and numb the shame, which leads them to have to help and care for you, worsening the moment. The issue is in the actions carried out, not the emotions leading up to them, which is Schema Therapy is so successful with BPD individuals.

The issue is in the actions carried out, not the emotions leading up to them, which is Schema Therapy is so successful with BPD individuals.

No

Individuals with BPD often struggle to maintain interpersonal relationships. An fMRI study done by the University of Georgia found that people with BPD traits had reduced activity in the specific brain regions that support empathy. This would suggest that people with BPD have difficulty understanding and/or predicting how other people feel. An interesting aspect of this study is also that they didn’t investigate BPD as binary, that someone either has it or doesn’t. Instead, they conceptualised and measured it in a continuum of no traits to very many. So they found a link between high BPD traits and reduced neural activity in the temporoparietal junction and superior temporal sulcus. The lead researcher, Haas, said that the next step would be to test this in real-life settings, as opposed to a lab environment, such as a BPD individual reading their partner’s emotions.

Many studies suggested that people with BPD feel greater empathy. But such studies are now being questioned, as their main method was to have a BPD and a non-BPD person rate their own personality, speak to the other and then rate their personality. The individuals with BPD were better are determining how the other person saw themselves. So they had a higher level of empathy? Maybe not, given that researchers now believe this is due to individuals with BPD having a more complex identity and sense of self, and thus being harder to read than the non-BPD counterpart. An interesting way forward could be to have BPD individuals rate each other, and the same for non-BPD, and see what trends emerge.

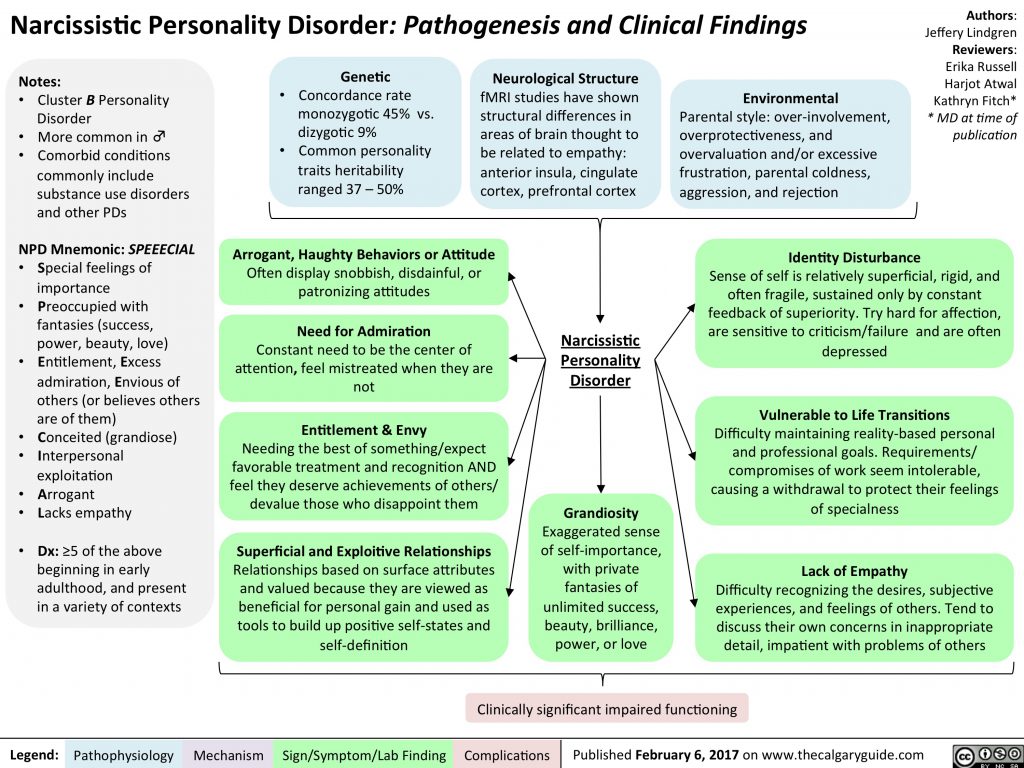

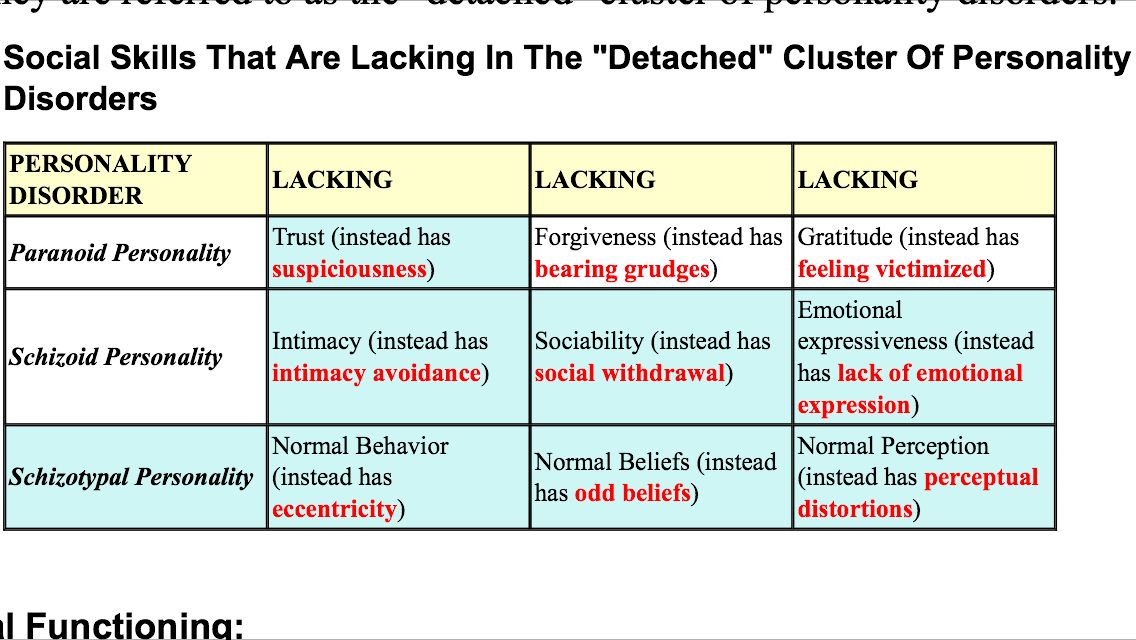

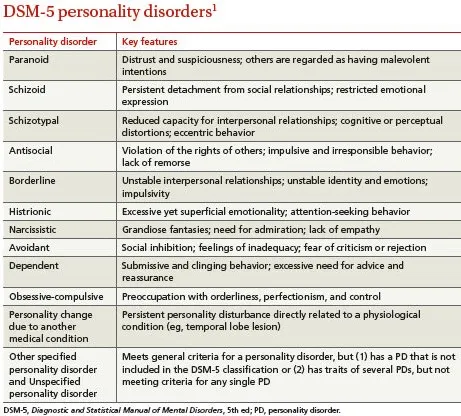

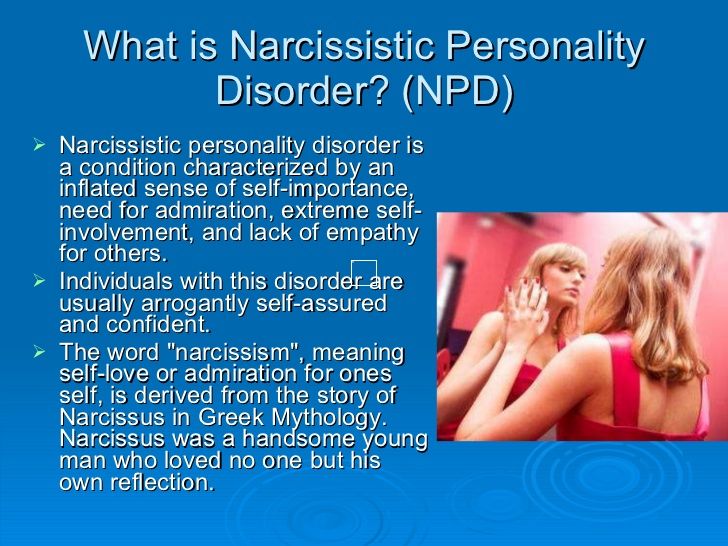

What disorders cause a lack of empathy?

We can’t know if individuals with BPD feel less empathy, but we do know that they do feel empathy somewhat. It is not a disorder characterised by a complete lack of empathy. So what are some disorders that lack empathy, for a frame of reference?

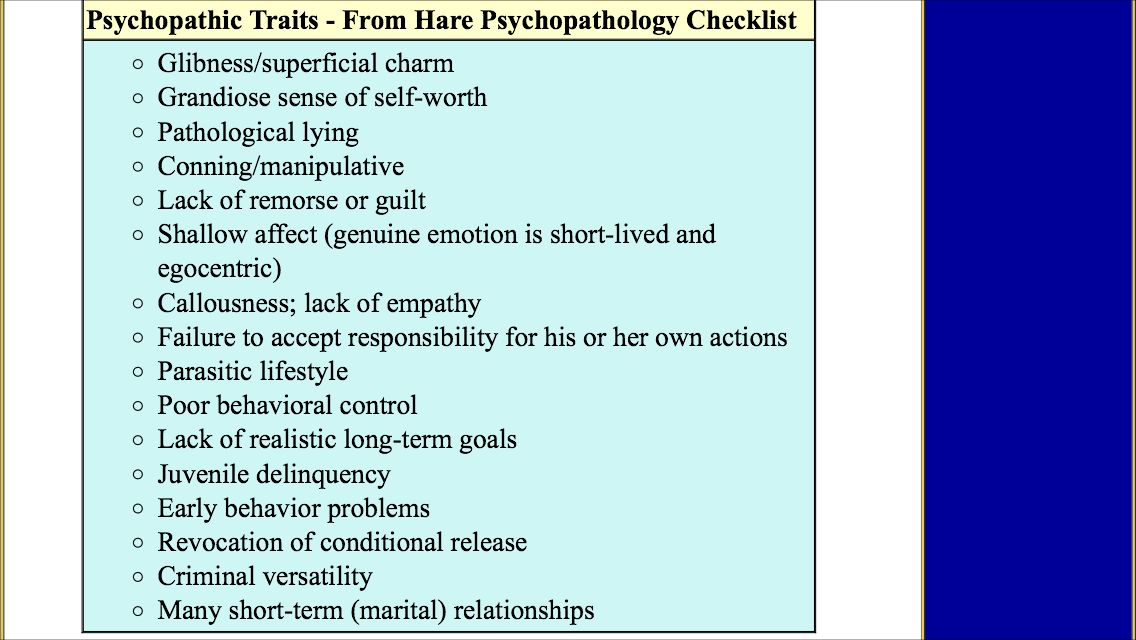

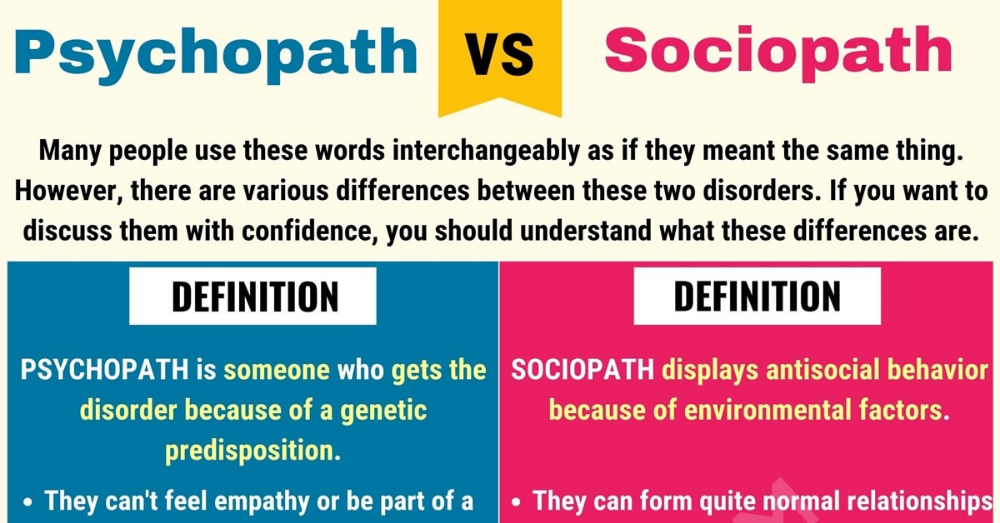

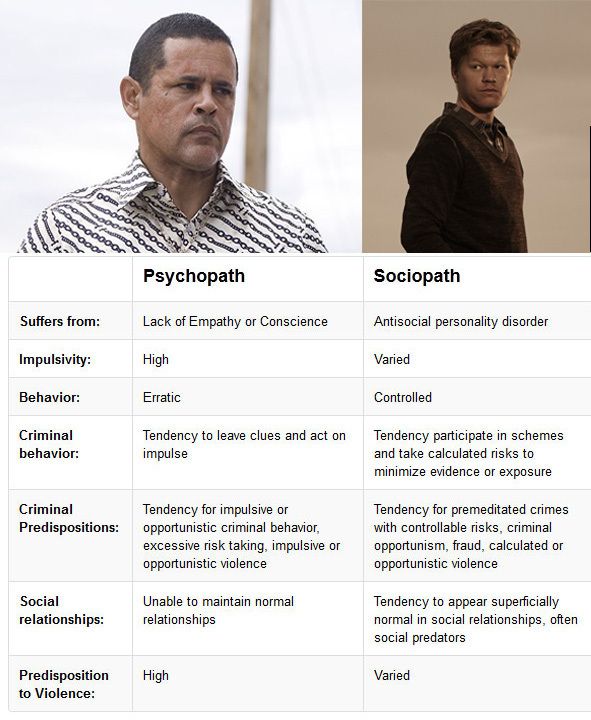

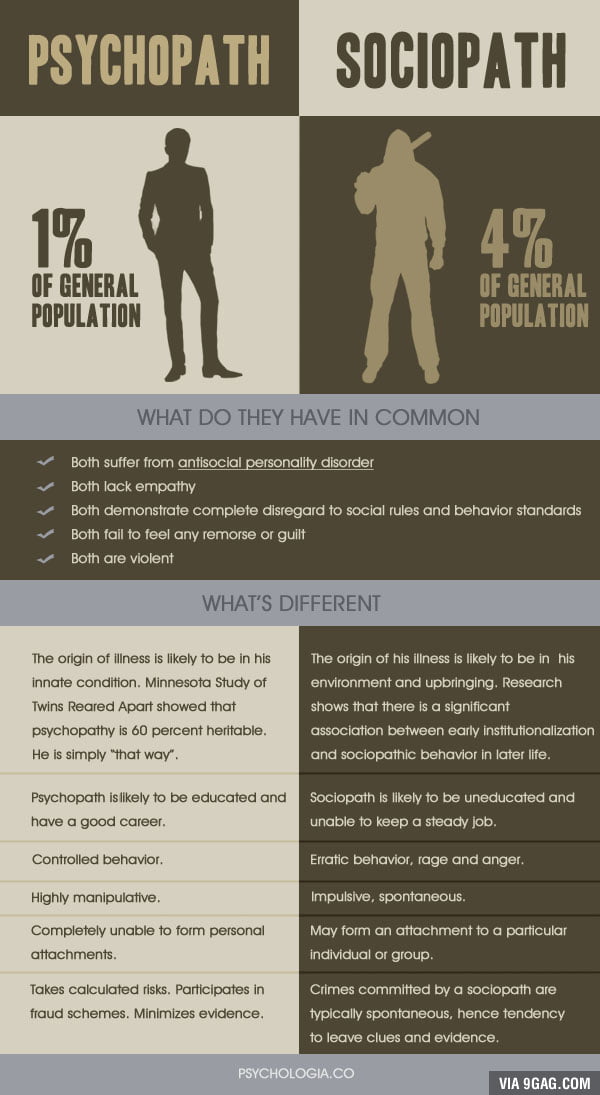

1. Psychopathy. An infamous disorder, to say the least. It is characterised by persistent antisocial behaviour, impaired empathy and remorse, as well as egotistical traits. Psychopaths are skilled at manipulation, so they know how someone expects them to act, but are able to feel no empathy. It is one of the most difficult disorders to spot and can be a dangerous one.

Psychopathy. An infamous disorder, to say the least. It is characterised by persistent antisocial behaviour, impaired empathy and remorse, as well as egotistical traits. Psychopaths are skilled at manipulation, so they know how someone expects them to act, but are able to feel no empathy. It is one of the most difficult disorders to spot and can be a dangerous one.

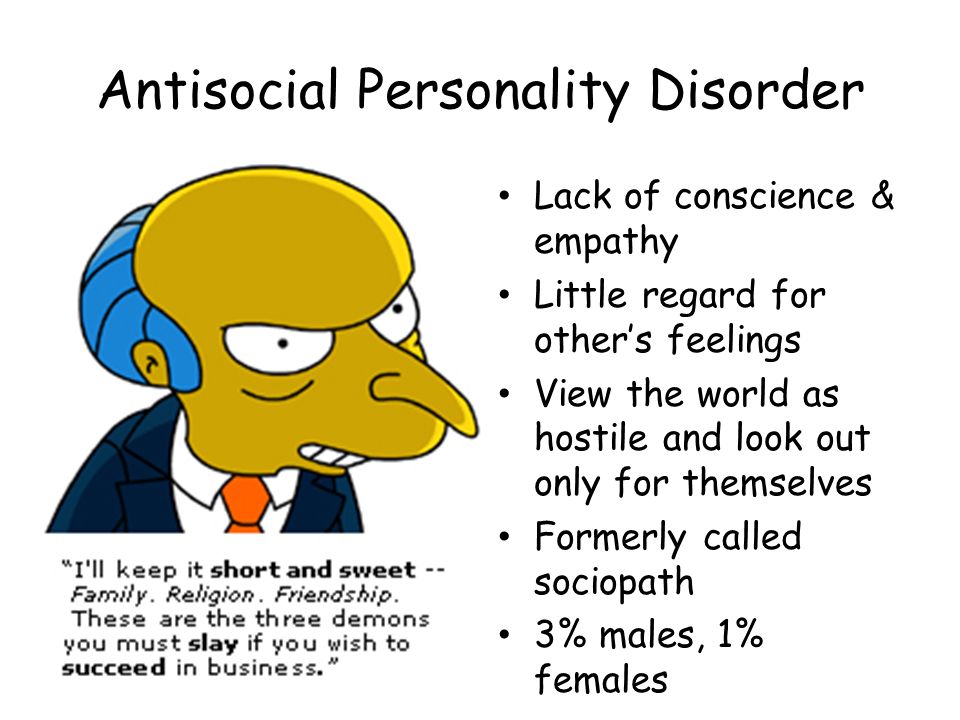

2. Antisocial Personality Disorder. People with APD are also known as sociopaths. This disorder fixates on a lack of regard for other people’s feelings or a violation of their rights. They struggle to consider consequences, feel no guilt or remorse and don’t respect social norms or laws.

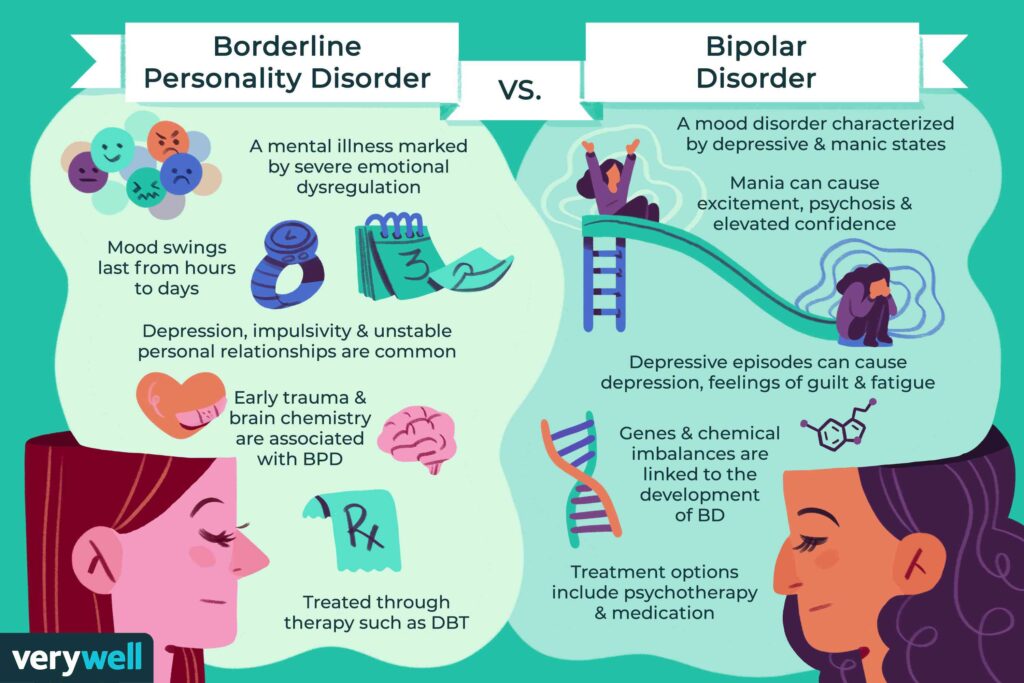

People have theorised about other disorders being linked to a lack of empathy, such as Bipolar or BPD, but this has not been proven and is not included in the latest DSM.

People with BPD often say that they feel so much. I feel great sadness from the smallest of things, a sadness that will weigh me down and make me question everything I have ever said or done. As children, individuals who will go on to develop BPD had to increase their own empathic functioning to protect themselves, from confusing or neglectful parenting. They trained themselves to be highly attuned to the subconscious cues of their parent, to be prepared for anything. It was a survival mechanism that had gone on to do more harm than good when they left that negative environment.

As children, individuals who will go on to develop BPD had to increase their own empathic functioning to protect themselves, from confusing or neglectful parenting. They trained themselves to be highly attuned to the subconscious cues of their parent, to be prepared for anything. It was a survival mechanism that had gone on to do more harm than good when they left that negative environment.

Many people who ask if someone with BPD feels empathy do so because they doubt it. How could someone feel empathy and hurt you so much? How could someone feel empathy and do these horrible things? The answer is, I don’t know, and I don’t know whether they feel more or less empathy. But I do know that their larger focus on themselves isn’t because of less empathy. And that many of their self-destructing behaviours are not the result of lowered empathy, but rather heightened emotions. Having reduced empathy wouldn’t mean that they feel less or even nothing. They feel more; they feel so much all the time.

Do you have any other questions regarding BPD? If so, please leave them in the comments, so that I can know what to address in future articles. The mystery around BPD is ripe for misunderstandings, and so I am happy to take the time to address them one by one and help to bring BPD into the conversation.

Dysfunction of Empathy and Related Processes in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review

1. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed Arlington, VA: APA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

2. Lieb K, Zanarini MC, Schmahl C, Linehan MM, Bohus M. Borderline personality disorder. Lancet 2004;364:453–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Bachmann S. Epidemiology of suicide and the psychiatric perspective. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2018;15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Gunderson JG. Disturbed relationships as a phenotype for borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:1637–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Blair RJ. Responding to the emotions of others: dissociating forms of empathy through the study of typical and psychiatric populations. Conscious Cogn 2005;14:698–718. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Decety J, Meyer M. From emotion resonance to empathic understanding: a social developmental neuroscience account. Dev Psychopathol 2008;20:1053–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Preston SD, de Waal FB. Empathy: its ultimate and proximate bases. Behav Brain Sci 2002;25:1–20; discussion 20–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. de Waal FBM, Preston SD. Mammalian empathy: behavioural manifestations and neural basis. Nat Rev Neurosci 2017;18:498–509. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Ekman P, Sorenson ER, Friesen WV. Pan-cultural elements in facial displays of emotion. Science 1969;164:86–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Davis MH. Measuring individual differences in empathy: evidence for a multidimensional approach. J Pers Soc Psychol 1983;44:113–26. [Google Scholar]

[Google Scholar]

11. Gallese V. The ‘shared manifold’ hypothesis. From mirror neurons to empathy. J Conscious Stud 2001;8:33–50. [Google Scholar]

12. Gallese V. Before and below ‘theory of mind’: embodied simulation and the neural correlates of social cognition. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2007;362:659–69. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Dapretto M, Davies MS, Pfeifer JH, et al. Understanding emotions in others: mirror neuron dysfunction in children with autism spectrum disorders. Nat Neurosci 2006;9:28–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Premack D, Woodruff G. Does the chimpanzee have a theory of mind. Behav Brain Sci 1978;1:515–26. [Google Scholar]

15. Gallagher HL, Frith CD. Functional imaging of ‘theory of mind.’ Trends Cogn Sci 2003;7:77–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Shamay-Tsoory SG, Shur S, Barcai-Goodman L, Medlovich S, Harari H, Levkovitz Y. Dissociation of cognitive from affective components of theory of mind in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2007;149:11–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry Res 2007;149:11–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Harari H, Shamay-Tsoory SG, Ravid M, Levkovitz Y. Double dissociation between cognitive and affective empathy in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2010;175:277–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Bateman AW, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment of BPD. J Pers Disord 2004;18:36–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Bateman A, Fonagy P. Comorbid antisocial and borderline personality disorders: mentalization-based treatment. J Clin Psychol 2008;64:181–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Choi-Kain LW, Gunderson JG. Mentalization: ontogeny, assessment, and application in the treatment of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2008;165:1127–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Sharp C, Pane H, Ha C, et al. Theory of mind and emotion regulation difficulties in adolescents with borderline traits. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;50:563–73.e1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Beer JS, Ochsner KN. Social cognition: a multi level analysis. Brain Res 2006;1079:98–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Social cognition: a multi level analysis. Brain Res 2006;1079:98–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Herpertz SC. The social-cognitive basis of personality disorders: commentary on the special issue. J Pers Disord 2013;27:113–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Mayer JD, Caruso DR, Salovey P. Emotional intelligence meets traditional standards for an intelligence. Intelligence 1999;27:267–98. [Google Scholar]

25. Mayer JD, Salovey P, Caruso DR, Sitarenios G. Measuring emotional intelligence with the MSCEIT V2.0. Emotion 2003;3:97–105. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Jeung H, Herpertz SC. Impairments of interpersonal functioning: empathy and intimacy in borderline personality disorder. Psychopathology 2014;47:220–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Fonagy P. Thinking about thinking: some clinical and theoretical considerations in the treatment of a borderline patient. Int J Psychoanal 1991;72(pt 4):639–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Fonagy P, Leigh T, Steele M, et al. The relation of attachment status, psychiatric classification, and response to psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996;64:22–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The relation of attachment status, psychiatric classification, and response to psychotherapy. J Consult Clin Psychol 1996;64:22–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Westen D. Social cognition and object relations. Psychol Bull 1991;109:429–55. [Google Scholar]

30. Bateman A, Fonagy P. Mentalization-based treatment. Psychoanal Inq 2013;33:595–613. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Dinsdale N, Crespi BJ. The borderline empathy paradox: evidence and conceptual models for empathic enhancements in borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 2013;27:172–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Krohn A. Borderline “empathy” and differentiation of object representations: a contribution to the psychology of object relations. Int J Psychoanal Psychother 1974;3:142–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed., rev Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Press, 1987. [Google Scholar]

34. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text rev Washington, D.C.: APA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed., text rev Washington, D.C.: APA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

35. World Health Organization The international statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 10th rev Geneva: WHO, 1992. [Google Scholar]

36. Preißler S, Dziobek I, Ritter K, Heekeren HR, Roepke S. Social cognition in borderline personality disorder: evidence for disturbed recognition of the emotions, thoughts, and Intentions of others. Front Behav Neurosci 2010;4:182. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Happe FG. An advanced test of theory of mind: understanding of story characters’ thoughts and feelings by able autistic, mentally handicapped, and normal children and adults. J Autism Dev Disord 1994;24:129–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Fletcher PC, Happe F, Frith U, et al. Other minds in the brain: a functional imaging study of “theory of mind” in story comprehension. Cognition 1995;57:109–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Happe FG, Winner E, Brownell H. The getting of wisdom: theory of mind in old age. Dev Psychol 1998;34:358–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Arntz A, Bernstein D, Oorschot M, Schobre P. Theory of mind in borderline and cluster-C personality disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2009;197:801–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Yeh Z-T, Lin Y-C, Liu S-I, Fang C-K. Social awareness and its relationship with emotion recognition and theory of mind in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Soc Clin Psychol 2017;36:22–40. [Google Scholar]

42. Stone VE, Baron-Cohen S, Knight RT. Frontal lobe contributions to theory of mind. J Cogn Neurosci 1998;10:640–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Baron-Cohen S, O’Riordan M, Stone V, Jones R, Plaisted K. Recognition of faux pas by normally developing children and children with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J Autism Dev Disord 1999;29:407–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S, Hill J, Raste Y, Plumb I. The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2001;42:241–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

The “Reading the Mind in the Eyes” Test revised version: a study with normal adults, and adults with Asperger syndrome or high-functioning autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2001;42:241–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Harkness K, Sabbagh M, Jacobson J, Chowdrey N, Chen T. Enhanced accuracy of mental state decoding in dysphoric college students. Cogn Emot 2005;19:999–1025. [Google Scholar]

46. Scott LN, Levy KN, Adams RB, Jr., Stevenson MT. Mental state decoding abilities in young adults with borderline personality disorder traits. Personal Disord 2011;2:98–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Schilling L, Wingenfeld K, Lowe B, et al. Normal mind-reading capacity but higher response confidence in borderline personality disorder patients. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci 2012;66:322–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Frick C, Lang S, Kotchoubey B, et al. Hypersensitivity in borderline personality disorder during mindreading. PLoS One 2012;7:e41650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S. The empathy quotient: an investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J Autism Dev Disord 2004;34:163–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Baron-Cohen S, Wheelwright S. The empathy quotient: an investigation of adults with Asperger syndrome or high functioning autism, and normal sex differences. J Autism Dev Disord 2004;34:163–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Lawrence EJ, Shaw P, Baker D, Baron-Cohen S, David AS. Measuring empathy: reliability and validity of the empathy quotient. Psychol Med 2004;34:911–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Dziobek I, Fleck S, Kalbe E, et al. Introducing MASC: a movie for the assessment of social cognition. J Autism Dev Disord 2006;36:623–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Andreou C, Kelm L, Bierbrodt J, et al. Factors contributing to social cognition impairment in borderline personality disorder and schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2015;229:872–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Dziobek I, Rogers K, Fleck S, et al. Dissociation of cognitive and emotional empathy in adults with Asperger syndrome using the Multifaceted Empathy Test (MET). J Autism Dev Disord 2008;38:464–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Dziobek I, Preissler S, Grozdanovic Z, Heuser I, Heekeren HR, Roepke S. Neuronal correlates of altered empathy and social cognition in borderline personality disorder. Neuroimage 2011;57:539–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Dziobek I, Preissler S, Grozdanovic Z, Heuser I, Heekeren HR, Roepke S. Neuronal correlates of altered empathy and social cognition in borderline personality disorder. Neuroimage 2011;57:539–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Ritter K, Dziobek I, Preissler S, et al. Lack of empathy in patients with narcissistic personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2011;187:241–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Wingenfeld K, Kuehl LK, Janke K, et al. Enhanced emotional empathy after mineralocorticoid receptor stimulation in women with borderline personality disorder and healthy women. Neuropsychopharmacology 2014;39:1799–804. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Wingenfeld K, Duesenberg M, Fleischer J, et al. Psychosocial stress differentially affects emotional empathy in women with borderline personality disorder and healthy controls. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2018;137:206–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Fonagy P, Luyten P, Moulton-Perkins A, et al. Development and validation of a self-report measure of mentalizing: the reflective functioning questionnaire. PLoS One 2016;11:e0158678. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

PLoS One 2016;11:e0158678. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Langdon R, Michie PT, Ward PB, McConaghy N, Catts SV, Coltheart M. Defective self and/or other mentalising in schizophrenia: a cognitive neuropsychological approach. Cogn Neuropsychiatry 1997;2:167–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Langdon R, Coltheart M. Mentalising, schizotypy, and schizophrenia. Cognition 1999;71:43–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Petersen R, Brakoulias V, Langdon R. An experimental investigation of mentalization ability in borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry 2016;64:12–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Brune M. Emotion recognition, ‘theory of mind,’ and social behavior in schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res 2005;133:135–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Ghiassi V, Dimaggio G, Brune M. Dysfunctions in understanding other minds in borderline personality disorder: a study using cartoon picture stories. Psychother Res 2010;20:657–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Bosco FM, Colle L, De Fazio S, Bono A, Ruberti S, Tirassa M. Th.o.m.a.s.: an exploratory assessment of theory of mind in schizophrenic subjects. Conscious Cogn 2009;18:306–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Bosco FM, Colle L, De Fazio S, Bono A, Ruberti S, Tirassa M. Th.o.m.a.s.: an exploratory assessment of theory of mind in schizophrenic subjects. Conscious Cogn 2009;18:306–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Bosco FM, Gabbatore I, Tirassa M, Testa S. Psychometric properties of the theory of mind assessment scale in a sample of adolescents and adults. Front Psychol 2016;7:566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Langdon R, Ward PB, Coltheart M. Reasoning anomalies associated with delusions in schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull 2010;36:321–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Reniers RL, Corcoran R, Drake R, Shryane NM, Vollm BA. The QCAE: a questionnaire of cognitive and affective empathy. J Pers Assess 2011;93:84–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Hausberg MC, Schulz H, Piegler T, et al. Is a self-rated instrument appropriate to assess mentalization in patients with mental disorders? Development and first validation of the mentalization questionnaire (MZQ). Psychother Res 2012;22:699–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychother Res 2012;22:699–709. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Dimitrijevic A, Hanak N, Altaras Dimitrijevic A, Jolic Marjanovic Z. The mentalization scale (MentS): a self-report measure for the assessment of mentalizing capacity. J Pers Assess 2018;100:268–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Niedtfeld I. Experimental investigation of cognitive and affective empathy in borderline personality disorder: effects of ambiguity in multimodal social information processing. Psychiatry Res 2017;253:58–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Regenbogen C, Schneider DA, Finkelmeyer A, et al. The differential contribution of facial expressions, prosody, and speech content to empathy. Cogn Emot 2012;26:995–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Guttman HA, Laporte L. Empathy in families of women with borderline personality disorder, anorexia nervosa, and a control group. Fam Process 2000;39:345–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Fertuck EA, Jekal A, Song I, et al. Enhanced ‘Reading the Mind in the Eyes’ in borderline personality disorder compared to healthy controls. Psychol Med 2009;39:1979–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychol Med 2009;39:1979–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Hertel J, Schutz A, Lammers CH. Emotional intelligence and mental disorder. J Clin Psychol 2009;65:942–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Beblo T, Pastuszak A, Griepenstroh J, et al. Self-reported emotional dysregulation but no impairment of emotional intelligence in borderline personality disorder: an explorative study. J Nerv Ment Dis 2010;198:385–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. New AS, aan het Rot M, Ripoll LH, et al. Empathy and alexithymia in borderline personality disorder: clinical and laboratory measures. J Pers Disord 2012;26:660–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Peter M, Schuurmans H, Vingerhoets AJ, Smeets G, Verkoeijen P, Arntz A. Borderline personality disorder and emotional intelligence. J Nerv Ment Dis 2013;201:99–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Baez S, Marengo J, Perez A, et al. Theory of mind and its relationship with executive functions and emotion recognition in borderline personality disorder. J Neuropsychol 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Neuropsychol 2014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

79. Matzke B, Herpertz SC, Berger C, Fleischer M, Domes G. Facial reactions during emotion recognition in borderline personality disorder: a facial electromyography study. Psychopathology 2014;47:101–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Unoka ZS, Fogd D, Seres I, Keri S, Csukly G. Early maladaptive schema-related impairment and co-occurring current major depressive episode-related enhancement of mental state decoding ability in borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 2015;29:145–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Vaskinn A, Antonsen BT, Fretland RA, Dziobek I, Sundet K, Wilberg T. Theory of mind in women with borderline personality disorder or schizophrenia: differences in overall ability and error patterns. Front Psychol 2015;6:1239. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Hurtado MM, Trivino M, Arnedo M, Roldan G, Tudela P. Are executive functions related to emotional intelligence? A correlational study in schizophrenia and borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2016;246:84–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry Res 2016;246:84–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Flasbeck V, Enzi B, Brune M. Childhood trauma affects processing of social interactions in borderline personality disorder: an event-related potential study investigating empathy for pain. World J Biol Psychiatry 2017:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Flasbeck V, Enzi B, Brune M. Altered empathy for psychological and physical pain in borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 2017;31:689–708. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Homan P, Reddan MC, Brosch T, Koenigsberg HW, Schiller D. Aberrant link between empathy and social attribution style in borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2017;94:163–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Martin F, Flasbeck V, Brown EC, Brune M. Altered mu-rhythm suppression in borderline personality disorder. Brain Res 2017;1659:64–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Perroud N, Badoud D, Weibel S, et al. Mentalization in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: comparison with controls and patients with borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2017;256:334–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Psychiatry Res 2017;256:334–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Zabihzadeh A, Maleki G, Richman MJ, Hatami A, Alimardani Z, Heidari M. Affective and cognitive theory of mind in borderline personality disorder: the role of comorbid depression. Psychiatry Res 2017;257:144–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Anupama V, Bhola P, Thirthalli J, Mehta UM. Pattern of social cognition deficits in individuals with borderline personality disorder. Asian J Psychiatr 2018;33:105–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Badoud D, Prada P, Nicastro R, et al. Attachment and reflective functioning in women with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 2018;32:17–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Berenson KR, Dochat C, Martin CG, Yang X, Rafaeli E, Downey G. Identification of mental states and interpersonal functioning in borderline personality disorder. Personal Disord 2018;9:172–81. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Grzegorzewski P, Kulesza M, Pluta A, Iqbal Z, Kucharska K. Assessing self-reported empathy and altruism in patients suffering from enduring borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2019:798–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Assessing self-reported empathy and altruism in patients suffering from enduring borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2019:798–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. Morandotti N, Brondino N, Merelli A, et al. The Italian version of the reflective functioning questionnaire: validity data for adults and its association with severity of borderline personality disorder. PLoS One 2018;13:e0206433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Pluta A, Kulesza M, Grzegorzewski P, Kucharska K. Assessing advanced theory of mind and alexithymia in patients suffering from enduring borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2018;261:436–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Colle L, Gabbatore I, Riberi E, Borroz E, Bosco FM, Keller R. Mindreading abilities and borderline personality disorder: a comprehensive assessment using the theory of mind assessment scale. Psychiatry Res 2019;272:609–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Lind M, Thomsen DK, Boye R, Heinskou T, Simonsen S, Jorgensen CR. Personal and parents’ life stories in patients with borderline personality disorder. Scand J Psychol 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Personal and parents’ life stories in patients with borderline personality disorder. Scand J Psychol 2019. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Normann-Eide E, Antonsen BT, Kvarstein EH, Pedersen G, Vaskinn A, Wilberg T. Are impairments in theory of mind specific to borderline personality disorder? J Pers Disord 2019:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Van Heel M, Luyten P, De Meulemeester C, Vanwalleghem D, Vermote R, Lowyck B. Mentalizing based on external features in borderline personality disorder compared with healthy controls: the role of attachment dimensions and childhood trauma. J Pers Disord 2019:1–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Duque-Alarcon X, Alcala-Lozano R, Gonzalez-Olvera JJ, Garza-Villarreal EA, Pellicer F. Effects of childhood maltreatment on social cognition and brain functional connectivity in borderline personality disorder patients. Front Psychiatry 2019;10:156. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. Peter M, Arntz AR, Klimstra T, Vingerhoets A. Different aspects of emotional intelligence of borderline personality disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother 2018;25:e51–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Different aspects of emotional intelligence of borderline personality disorder. Clin Psychol Psychother 2018;25:e51–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. Zegarra-Valdivia JA, Chino Vilca BN. Social cognition and executive function in borderline personality disorder: Evidence of altered cognitive processes. Salud Mental 2019;42:33–42. [Google Scholar]

102. Roepke S, Vater A, Preissler S, Heekeren HR, Dziobek I. Social cognition in borderline personality disorder. Front Neurosci 2013;6:195. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. King-Casas B, Sharp C, Lomax-Bream L, Lohrenz T, Fonagy P, Montague PR. The rupture and repair of cooperation in borderline personality disorder. Science 2008;321:806–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Lazarus SA, Cheavens JS, Festa F, Zachary Rosenthal M. Interpersonal functioning in borderline personality disorder: a systematic review of behavioral and laboratory-based assessments. Clin Psychol Rev 2014;34:193–205. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Brune M, Walden S, Edel MA, Dimaggio G. Mentalization of complex emotions in borderline personality disorder: the impact of parenting and exposure to trauma on the performance in a novel cartoon-based task. Compr Psychiatry 2016;64:29–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Janke K, Driessen M, Behnia B, Wingenfeld K, Roepke S. Emotional intelligence in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder, borderline personality disorder and healthy controls. Psychiatry Res 2018;264:290–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Mehta UM, Thirthalli J, Naveen Kumar C, et al. Validation of Social Cognition Rating Tools in Indian Setting (SOCRATIS): a new test-battery to assess social cognition. Asian J Psychiatr 2011;4:203–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Franzen N, Hagenhoff M, Baer N, et al. Superior ‘theory of mind’ in borderline personality disorder: an analysis of interaction behavior in a virtual trust game. Psychiatry Res 2011;187:224–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Lis S, Bohus M. Social interaction in borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2013;15:338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lis S, Bohus M. Social interaction in borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2013;15:338. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110. Ripoll LH, Snyder R, Steele H, Siever LJ. The neurobiology of empathy in borderline personality disorder. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2013;15:344. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111. Thoma P, Friedmann C, Suchan B. Empathy and social problem solving in alcohol dependence, mood disorders and selected personality disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013;37:448–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Herpertz SC, Bertsch K. The social-cognitive basis of personality disorders. Curr Opin Psychiatry 2014;27:73–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

113. Herpertz SC, Jeung H, Mancke F, Bertsch K. Social dysfunctioning and brain in borderline personality disorder. Psychopathology 2014;47:417–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

114. Richman MJ, Unoka Z. Mental state decoding impairment in major depression and borderline personality disorder: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry 2015;207:483–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115. Nemeth N, Matrai P, Hegyi P, et al. Theory of mind disturbances in borderline personality disorder: a meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2018;270:143–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

116. Rokita KI, Dauvermann MR, Donohoe G. Early life experiences and social cognition in major psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Eur Psychiatry 2018;53:123–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

117. Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, et al. Research domain criteria (RDoC): toward a new classification framework for research on mental disorders. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:748–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118. Mier D, Lis S, Esslinger C, et al. Neuronal correlates of social cognition in borderline personality disorder. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci 2013;8:531–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119. Beeney JE, Hallquist MN, Ellison WD, Levy KN. Self-other disturbance in borderline personality disorder: neural, self-report, and performance-based evidence. Personal Disord 2016;7:28–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Personal Disord 2016;7:28–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

120. Vollm B, Richardson P, Stirling J, et al. Neurobiological substrates of antisocial and borderline personality disorder: preliminary results of a functional fMRI study. Crim Behav Ment Health 2004;14:39–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

121. Das P, Calhoun V, Malhi GS. Bipolar and borderline patients display differential patterns of functional connectivity among resting state networks. Neuroimage 2014;98:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122. O’Neill A, D’Souza A, Samson AC, Carballedo A, Kerskens C, Frodl T. Dysregulation between emotion and theory of mind networks in borderline personality disorder. Psychiatry Res 2015;231:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

123. Vollm BA, Zhao L, Richardson P, et al. A voxel-based morphometric MRI study in men with borderline personality disorder: preliminary findings. Crim Behav Ment Health 2009;19:64–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

124. Rossi R, Lanfredi M, Pievani M, et al. Abnormalities in cortical gray matter density in borderline personality disorder. Eur Psychiatry 2015;30:221–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Abnormalities in cortical gray matter density in borderline personality disorder. Eur Psychiatry 2015;30:221–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

125. Depping MS, Wolf ND, Vasic N, Sambataro F, Thomann PA, Wolf RC. Common and distinct structural network abnormalities in major depressive disorder and borderline personality disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2016;65:127–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

126. Boen E, Westlye LT, Elvsashagen T, et al. Regional cortical thinning may be a biological marker for borderline personality disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014;130:193–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

127. Niedtfeld I, Schulze L, Krause-Utz A, Demirakca T, Bohus M, Schmahl C. Voxel-based morphometry in women with borderline personality disorder with and without comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder. PLoS One 2013;8:e65824. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

128. Depping MS, Wolf ND, Vasic N, Sambataro F, Thomann PA, Christian Wolf R. Specificity of abnormal brain volume in major depressive disorder: a comparison with borderline personality disorder. J Affect Disord 2015;174:650–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Specificity of abnormal brain volume in major depressive disorder: a comparison with borderline personality disorder. J Affect Disord 2015;174:650–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

129. New AS, Carpenter DM, Perez-Rodriguez MM, et al. Developmental differences in diffusion tensor imaging parameters in borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Res 2013;47:1101–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

130. Montague PR, Berns GS, Cohen JD, et al. Hyperscanning: simultaneous fMRI during linked social interactions. Neuroimage 2002;16:1159–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

131. Unoka Z, Seres I, Aspan N, Bodi N, Keri S. Trust game reveals restricted interpersonal transactions in patients with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 2009;23:399–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

132. Poggi A, Richetin J, Preti E. Trust and rejection sensitivity in personality disorders. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2019;21:69. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

133. Redcay E, Schilbach L. Using second-person neuroscience to elucidate the mechanisms of social interaction. Nat Rev Neurosci 2019;20:495–505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Nat Rev Neurosci 2019;20:495–505. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

134. Zaki J, Ochsner KN. The neuroscience of empathy: progress, pitfalls and promise. Nat Neurosci 2012;15:675–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

135. Trull TJ, Ebner-Priemer UW. Using experience sampling methods/ecological momentary assessment (ESM/EMA) in clinical assessment and clinical research: introduction to the special section. Psychol Assess 2009;21:457–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

136. Santangelo P, Bohus M, Ebner-Priemer UW. Ecological momentary assessment in borderline personality disorder: a review of recent findings and methodological challenges. J Pers Disord 2014;28:555–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Lack of empathy. Devoid of Conscience [Frightening World of Psychopaths]

Lack of empathy

Many features of psychopaths: self-centeredness, lack of regret, superficiality of emotions, cunning - are often complemented by a complete lack of empathy (inability to imagine the state and feelings of another person).![]() They cannot enter anyone's position. Psychopaths don't care about other people's feelings.

They cannot enter anyone's position. Psychopaths don't care about other people's feelings.

To some extent, they resemble soulless androids, characters of science fiction, who are not allowed to experience what a living person feels. One rapist (who scored high on the Psychopathy Checklist) noticed that he had difficulty empathizing with his victims. “Are they scared? Then, you know, I don't understand them. I was also scared, but for me it was not something unpleasant.

Psychopaths treat others as a means of satisfying their wants and needs. The weak and vulnerable, more often bullied than pitied by psychopaths, are their favorite victims. “In the universe of psychopaths, there is no such thing as just being weak,” writes psychologist Robert Rieber. - According to them, whoever is weak is stupid; i.e. he himself begs to be used.”9

"Oh yes, he was terribly unlucky," snapped a young prisoner, talking about the death of a guy he stabbed to death during a skirmish between two gangs. “Don't even try to tell me this nonsense. The little bastard got what he deserved, so I don't feel sorry for him. As you can see,” he waved towards the investigators, “now I have my own problems.”

“Don't even try to tell me this nonsense. The little bastard got what he deserved, so I don't feel sorry for him. As you can see,” he waved towards the investigators, “now I have my own problems.”

In order to survive (both physically and mentally), some normal individuals have to develop a certain insensitivity towards certain categories of people. (So, for example, if a doctor is too empathetic towards his patients, he will soon become overwhelmed with emotions and his efficiency will decrease.) Their insensitivity is manifested only in relation to a particular target group. By the same principle, soldiers, mafiosi and terrorists are trained - very effectively, as life has proven time and time again - to consider the enemy as a soulless object, and not a living person.

But psychopaths show a general lack of empathy. They are indifferent to the rights and sufferings of both relatives and strangers. If they maintain a relationship with a spouse or children, it is only because they consider them their property, like a tape recorder or a car. In general, the state of the interior of the car worries some psychopaths more than the state of mind of their "beloved". One woman allowed her lover to molest her five-year-old daughter because “he exhausted me. That evening, I was no longer able to have sex.” Later, she could not understand why the authorities deprived her of parental rights. “She belongs to me. Her life is my business." Still, she did not protest too much - deprived of a car for the duration of the hearing, she was much more insistent in demanding compensation for travel in public transport.

In general, the state of the interior of the car worries some psychopaths more than the state of mind of their "beloved". One woman allowed her lover to molest her five-year-old daughter because “he exhausted me. That evening, I was no longer able to have sex.” Later, she could not understand why the authorities deprived her of parental rights. “She belongs to me. Her life is my business." Still, she did not protest too much - deprived of a car for the duration of the hearing, she was much more insistent in demanding compensation for travel in public transport.

Because of their inability to empathize, some psychopaths do things that normal people find not only terrible, but incomprehensible. They may, for example, torture or mutilate the victim with the same feeling with which we butcher a Thanksgiving turkey.

However, very rare psychopaths commit such crimes. Their callousness usually comes out in a less dramatic (but no less destructive) way. This includes parasitism, feeding on other people's property, savings and self-esteem; aggressive actions aimed at achieving the desired; neglect of the physical and emotional well-being of relatives; engaging in endless casual, faceless and banal sexual relationships, etc.

Connie is now fifteen years old, and she floats between childhood and adulthood, plunging into one state after another. She is still a virgin, but her life is already adjusted to her burgeoning sexuality. One hot day, when the family leaves her at home alone, a stranger comes to the house, who says that he has been following her for a long time.

“I am your lover, dear,” [he tells her]. “You don’t know what it is yet, but you will soon find out… I know everything about you… I’ll tell you about it.” The first time I'm always kind. For the first time. I will hold you so tight that you won't even think about leaving or hoping for something, because you will know that you can't. I will enter you and find out all your secrets, and you will surrender and love me ... "-" I'm calling the police ... "[From] his tongue broke a short curse, supposedly not addressed to her. But even that sounded forced. Then he tried to smile again. She watched as his lips twisted into a grimace that resembled a smile. His whole face, she thought with horror, was like a mask that descended to the very neck. “Listen, dear. We are leaving now. It will be a great trip. If not, we are waiting for your parents to come home and then you will see what I will do with them…my little blue-eyed girl,” he sang out, though it had nothing to do with her brown eyes…

His whole face, she thought with horror, was like a mask that descended to the very neck. “Listen, dear. We are leaving now. It will be a great trip. If not, we are waiting for your parents to come home and then you will see what I will do with them…my little blue-eyed girl,” he sang out, though it had nothing to do with her brown eyes…

Joyce Carol Oates, Where Are You Going? Where Have You Been? ("Where are you going? Where have you been?")

This text is an introductory fragment.

Empathy Express Diagnostics

Express diagnostics of empathy It is used to examine teenagers and adults. Purpose: to determine the level of empathy. Description: The questionnaire contains b diagnostic scales of empathy, expressing the attitude towards parents, animals, the elderly, children, heroes of art

Low level of empathy

Low level of empathy Some people have no or very limited ability to understand how others will react to them

Establishing empathy

Establishing empathy The term “empathy” has recently worn out and practically lost its content. And yet there is no other word that would mean "feel with" and not "feel instead", which is the internal difference between

And yet there is no other word that would mean "feel with" and not "feel instead", which is the internal difference between

Chapter 7 ROOTS OF EMPATHY

Chapter 7 ROOTS OF EMPATHY Let's go back to Gary, the brilliant but alexithymic surgeon who inflicted great suffering on his fiancee Ellen by not only not paying attention to his own feelings, but to hers too. Like most alexithymics, he did not possess

Empathy neurology

The neuroscience of empathy As is often the case in neuroscience, the first clues to suggest that the source of empathy is to be found in the brain came from reports of bizarre and eccentric patients. The report for 1975, for example, analyzed individual

Whispers and Cries: The Power of Empathy

Whispers and Cries: The Power of Empathy Empathy is the most effective tool that helps us connect with other people. It is the bonding solution of human interconnectedness. Empathy allows us to feel at a deep level what the other is feeling

It is the bonding solution of human interconnectedness. Empathy allows us to feel at a deep level what the other is feeling

Chapter 7: Learn Empathy

Chapter 7 Careful empathy is essential not only for the therapist but also for patients, and it is our responsibility to help patients develop empathy for other people. Remember that our patients usually come to us because they are not successful in setting up and

Test: Empathy

Test: Empathy Rate each of the following statements as follows: “I don’t know” - 0, “No, never” - 1, “Sometimes” - 2, “Often” - 3, “Almost always” - 4, “Yes, always” - 5. Make sure you have answered all the points.1. I like travel books more than

Building empathy

Building Empathy About half of the young doctors who took part in one study admitted that their empathy for patients decreased in the course of their professional training (and only a third said that it strengthened) [144]. Many in the course of their careers never

Many in the course of their careers never

Empathy training

Empathy training When I was in graduate school, almost all courses included elements aimed at increasing empathy. This is how the majority of students specializing in psychology, social work, family counseling and family therapy are trained. Increasingly in

Barriers to Empathy

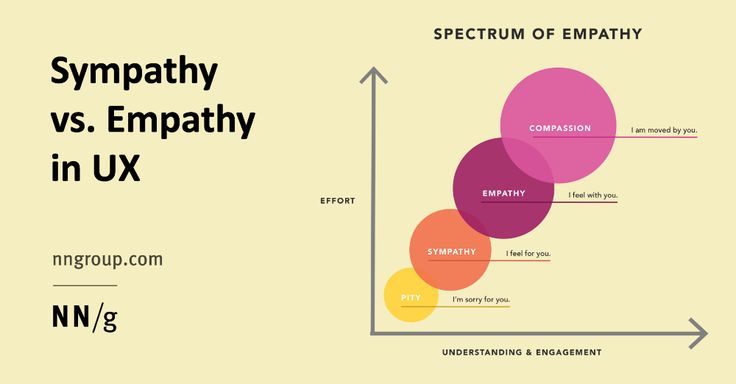

Empathy Barriers Pity versus empathy In conversation, we often confuse empathy with pity. However, in interviews, women explained the difference between them very clearly. When they talked about their ability to overcome shame, they clearly pointed to empathy: it takes

Pity versus empathy

Pity versus empathy In conversation, we often confuse empathy with pity. However, in interviews, women explained the difference between them very clearly. When they talked about their ability to overcome shame, they clearly pointed to empathy: sharing feelings with someone

When they talked about their ability to overcome shame, they clearly pointed to empathy: sharing feelings with someone

Catch the "sickness" of empathy

Catch the "disease" of empathy More and more research suggests that our brains have a hard time distinguishing between watching an action and participating in that action. Empathy - also a kind of "infection" - is based in part on our ability

Inability to empathize. People without empathy

Empathy is one of the important properties of communication with people, the ability to comprehend the state of mind, the experience of another person, to understand his emotional language, to respond to the psychological state.

This ability is very clearly seen in babies. If one cried, others will surely support him. This quality may be innate. If the level of empathy is low or absent, it can be developed through psychological exercises.

What is empathy?

Empathy is the ability of one person to comprehend and understand the emotions of another, to imagine oneself in his place, to feel his feelings and thoughts. This is an intuitive understanding of the psychological mood, the ability to take on the role of another person, to understand his hidden motives, emotional throwing, identification of one's feelings with the emotions of another and at the same time awareness of their exclusivity, individuality.

Lack of empathy or its low level indicate a person's indifference, his emotional coldness. This is the inability to understand emotional experiences, to sympathize with them.

It can be difficult for children and teenagers to explain their emotional problems and ask for help from adults. Empathy, as a trend in psychology, will help you understand your experiences. It will teach you to put yourself in the place of another person, to empathize with him.

Empathy level

Thanks to psychological tests, you can determine your level of empathy. This is the emotional range of feelings and emotions. Diagnostics of empathy conditionally divides people into 3 levels of perception.

This is the emotional range of feelings and emotions. Diagnostics of empathy conditionally divides people into 3 levels of perception.

Building relationships with people requires empathy. It is one of the main elements of communication. Through empathy, we understand the point of view of others. We can explain how they feel.

With the help of this ability it is possible not only to establish good relations with those who are pleasant, but also to understand the motivation, desires of those who are unpleasant. It also happens that not everyone is able to accept support from other people. At the everyday, non-professional level, it is more important to determine whether your empathy is needed at the moment.

Life experience contributes to filling the emotional sphere of a person. Crisis situations, the loss of loved ones, empathy for the sick, good relationships with parents and children - all this implies the development of empathy.

Many professions require the ability to understand and empathize. Basically it is a job related to communication. For example: leaders of all levels, managers, doctors, teachers, psychotherapists, salespeople, hairdressers.

Basically it is a job related to communication. For example: leaders of all levels, managers, doctors, teachers, psychotherapists, salespeople, hairdressers.

Types of empathy

Predicative empathy is the ability to anticipate the emotions of another person, the ability to predict psychological reactions.

Cognitive empathy - this is an intellectual analysis and synthesis of emotions, a willingness to accept, understand the point of view of your counterpart.

Emotional empathy is an imitation of the emotional reactions of other people, a willingness to respond to feelings and emotional unrest.

Professional psychologists share the concepts of sympathy and empathy. They are considered special forms of empathy.

Sympathy - emotional response to experiences. These are your own worries, anxieties in connection with the feelings of another person.

Empathy - identification with one's counterpart. Feeling the same emotions, feelings, psychological states.

Feeling the same emotions, feelings, psychological states.

Empathy in life

Manifestation of emotions is a natural state of a person. The existing mechanisms of empathy allow people to behave kindly and naturally in society, restrain negative experiences, not show them to strangers, listen carefully, and respond emotionally to feelings.

People with a high level of empathy are more tolerant of the emotional manifestations of others. They do not strive for constant clarification of relations, conflicts. They understand other people's feelings.

A low level of empathy makes a person aggressive, indifferent to pain. Such people try to blame others for their misfortunes, achieve less success in life, because they are not able to competently interact with people.

How to develop empathy?

Real empathy is the ability not only to feel the emotions of another person, but also to try them on yourself. Enter into his position, realize his thoughts and aspirations. The development of empathy occurs over time, with the accumulation of life experience, emotional baggage.

The development of empathy occurs over time, with the accumulation of life experience, emotional baggage.

To begin with, you should learn to listen to another person, delve into the timbre of his voice, follow the change in facial expressions, share with him the impression of what he heard.

The ability to praise is a special gift that empaths are capable of. It is not difficult for them to thank a person, express their respect, admiration. Elementary praise can melt the ice in human relationships.

Learn to analyze your actions, words, thoughts, correct them as needed. Seeking to understand yourself is an important aspect of developing empathy. Only after a person has realized his thoughts, feelings, aspirations - he will understand the motivation of other people.

Exercises to develop empathy

Special exercises will help you develop the ability to monitor the emotional state of people, learn to enter the comfort zone with another person, not repulse with your indifference, but attract with interest in communication.

Exercise "Telephone" . The participant is given the task of facial expressions and gestures to create the appearance of a conversation with the interlocutor. The rest need to guess what and with whom they are talking on the phone.

Exercise "Guess the mood" . Participants receive cards describing various emotions. They try to express this mood with their facial expressions. Other participants guess.

Monkey and mirror exercise . Participants are divided into pairs, in which one is a monkey, the other is a mirror. With the help of facial expressions, gestures, the monkey depicts different feelings, emotions. The mirror copies them. Then the participants change places.

Basic rules for dealing with people

- To be able to control one's actions, to follow words and feelings, not to allow harsh aggressive statements, attacks against other people - these are the first steps to understanding the importance of empathy.

The emergence of tolerance, compassion will help tune in to the necessary emotional wave with this or that person.

The emergence of tolerance, compassion will help tune in to the necessary emotional wave with this or that person. - Do not constantly try to interfere in the life, feelings of other people. Don't force empathy on those who don't need it. Be sure to love yourself with all the flaws and virtues. Make friends with those who sincerely want to communicate with you.

- Do not try to correct people by imposing your point of view. Each person has a personal worldview, perception of life. Don't take the blame for what others have done.

- Enrich your emotional sphere with works of art. Learn to make joint decisions with the partner, relatives. Control emotional outbursts. Learn to meditate and calm down in stressful situations.

Empathy is the ability of any person to be able to sympathize, and the ability to understand the inner world of another person.

If there is a feeling of empathy in a relationship is missing, then this is the beginning of terrible ordeals. can not only break off a relationship, but a person as well. Without wanting to go into too many details in the description, I suggest you read this article.

can not only break off a relationship, but a person as well. Without wanting to go into too many details in the description, I suggest you read this article.

Reasons for lack of empathy

The first question that comes to mind would be "what causes it?". The only thing that needs to be understood is that we cannot always telepathically convey our emotions and feelings to each other. It requires openness. Some people are unable to understand people's emotions. They claim that they are very practical and therefore fail to see the importance of emotions and understand them. These people feel that they are in pain at times with their loved ones; however, they believe it is required in a relationship. You see, they see life from a practical point of view, where "what is!" simply no.

They cannot understand the other's pain, as such, they question indecision in this matter. Others don't exactly lack empathy. The odd part is that they are fully aware of the person's feelings. However, they take pleasure in inflicting pain on humans. Moreover, they can even use this knowledge to manipulate a person. However, in certain respects, the lack of empathy can be for two reasons. First, the person could have psychopathic tendencies, and something he learned about the opposite person pissed him off. Or, the person could simply have something against the opposite person. In such cases, not empathizing with the person in the relationship is the result of cheating in the relationship.

However, they take pleasure in inflicting pain on humans. Moreover, they can even use this knowledge to manipulate a person. However, in certain respects, the lack of empathy can be for two reasons. First, the person could have psychopathic tendencies, and something he learned about the opposite person pissed him off. Or, the person could simply have something against the opposite person. In such cases, not empathizing with the person in the relationship is the result of cheating in the relationship.

What happens when there is no empathy in a marriage

This can be a terrible ordeal. Not only for the one who is exposed to it, but for the one who does not show empathy. For the one who submits to him, and disappointment rises from having a partner who simply does not understand what is happening. For someone who does not show empathy, there is a feeling of dissatisfaction, and the feeling of an unhealthy marriage creeps in later.

Lack of empathy in marriage due to lack of mutual understanding and trust. In most marriages, to experience this terrible feeling, there is a similar pattern. It is noted that at the beginning of the relationship, they talked to each other about everything, and everything was very beautiful. They spent a lot of time together and there was less pressure from the world. However, later on, the pressure has increased and the time they spend together is decreasing. They barely have time to talk to each other about their feelings. Moreover, whenever they tried to talk, they were mostly tired and irritable. As time has passed, the display of feelings for each other is also reduced and eventually causes the situation that arises when they liked each other, thus leading to trouble in the relationship.

In most marriages, to experience this terrible feeling, there is a similar pattern. It is noted that at the beginning of the relationship, they talked to each other about everything, and everything was very beautiful. They spent a lot of time together and there was less pressure from the world. However, later on, the pressure has increased and the time they spend together is decreasing. They barely have time to talk to each other about their feelings. Moreover, whenever they tried to talk, they were mostly tired and irritable. As time has passed, the display of feelings for each other is also reduced and eventually causes the situation that arises when they liked each other, thus leading to trouble in the relationship.

The best solution for such a case is a second honeymoon. The concept of a honeymoon vacation is basically to allow the couple to get closer to each other – physically, mentally and emotionally. Thus, if you see that this connection is breaking, then it's time to go on a honeymoon again. Make it long. Give each other time, and spend some quality time together. You can also try couples counseling to bring back the loving empathy that you once felt and then lost.

Make it long. Give each other time, and spend some quality time together. You can also try couples counseling to bring back the loving empathy that you once felt and then lost.

Spouses who are not sympathetic to each other, as an effect of psychopathic tendencies, therefore it is necessary to visit a psychologist and receive treatment. Things can be much worse if it is not controlled in time!

Lack of empathy in children

Lack of empathy in marriage often leads to the same in children. The fact remains that children learn from their parents. This is part of a child's development. Of course, there are exceptions and differences in perception. Barring the same for these exceptions, children pick up on the same things themselves and behave in an unsympathetic way after watching their parents' behavior.

If a child sees one parent who does not care about others and their feelings, the child will lose respect for him. In principle, the situation in the house will be very narcissistic. Where everyone just takes care of themselves, and does not see and does not take into account other people's feelings. Basically in such a case, siblings tend to take sympathy for each other, but losing it for their parents. Another side effect in children is that later in life they tend to lose faith in marriage and love. This is mainly found in the fact that such children have an acute fear of commitment and do not believe in love or marriage.

Where everyone just takes care of themselves, and does not see and does not take into account other people's feelings. Basically in such a case, siblings tend to take sympathy for each other, but losing it for their parents. Another side effect in children is that later in life they tend to lose faith in marriage and love. This is mainly found in the fact that such children have an acute fear of commitment and do not believe in love or marriage.

The best solution for this is to show affection in front of the child. Let him know that his parents love and respect each other. Teach him the important values in life and show him how important it is to follow them.

Lack of empathy in relationships is a natural outcome of dysfunctional relationships. It can also be said that dysfunctional relationships and lack of understanding form a vicious circle. To break this cycle, you need to find love and compassion in yourself and share it with your loved ones. It will be hard at first, but it will only strengthen the family.

Ecology of consciousness. Psychology: There are people with whom at first glance it is easy to communicate - they can always fill in the pauses in a conversation, constantly joke, talk about something. For superficial communication - this is ideal. People usually sympathize with such colleagues, boyfriends and girlfriends with whom you can have fun. But in family life, their partners often face misunderstanding, lack of depth and real support.

Blocked person

There are people with whom, at first glance, it is easy to communicate - they can always fill in the gaps in a conversation, constantly joke, talk about something . For superficial communication - this is ideal. People usually sympathize with such colleagues, boyfriends and girlfriends with whom you can have fun. But in family life, their partners often face misunderstanding, lack of depth and real support.

They may not notice or understand that the person next to them is depressed, for example. Most often these are down-to-earth people with a superficial, stereotyped perception of the world. They don't know how to actively listen. The main thing for them is to speak out themselves . Thus, they fill the space with various noises in order to avoid frank conversations, because they are afraid of them, or they do not understand anything about them. That is, a person has a block to the manifestation of empathy - the ability to understand what is happening with his loved one, and empathize.

Most often these are down-to-earth people with a superficial, stereotyped perception of the world. They don't know how to actively listen. The main thing for them is to speak out themselves . Thus, they fill the space with various noises in order to avoid frank conversations, because they are afraid of them, or they do not understand anything about them. That is, a person has a block to the manifestation of empathy - the ability to understand what is happening with his loved one, and empathize.

Most often, such a person was brought up in a family where his parents were also deaf to him.

For example, one of my acquaintances had a father who was a despotic man who only drilled his children, hoping to raise them into Stoics in his own image and likeness, while any spiritual conversations were not encouraged and were considered a manifestation of weakness. The mother of this acquaintance also did not know how to listen. When her son approached her to tell her something, she always interrupted him and began to chatter without listening to the end.

How does a blocked person manifest himself in communication with relatives?

1. Here he wants to tell you something that he has accumulated during a hard day's work. But it seems that his goal is not to be heard and understood , but simply to pour out a verbal stream.

For example, the wife is preparing dinner in the kitchen, and at this time the husband, from somewhere in the hallway, begins to tell her how his day went, then he goes to wash his hands, then walks around the rooms and does something, while his wife continues to hear snippets of his sentences. The husband, apparently, is not very concerned about whether his wife hears or not. And when he enters the kitchen and sits down at the table, he immediately turns on the TV, being in full confidence that he and his wife have sort of talked and now you can set aside time for dinner and watching TV.

2. When you are about to tell this person something, he will not consider it important enough to sit next to you and listen carefully. . He will say, "like Julius Caesar, I am highly efficient and can do several things at the same time." At the same time, with one ear, he will listen to you, without even looking in your direction, at the same time picking his nose and looking at the computer monitor, shouting something to your children and even answering the call.

. He will say, "like Julius Caesar, I am highly efficient and can do several things at the same time." At the same time, with one ear, he will listen to you, without even looking in your direction, at the same time picking his nose and looking at the computer monitor, shouting something to your children and even answering the call.

3. When you want to discuss with this person something that is important to you and he, it would seem, is already ready to listen to you carefully, suddenly, with the beginning of the conversation, he begins to have some business . He suddenly remembers that he needs to run somewhere, or that football is about to start, or suggests that you get distracted and watch a teaser for a new film, sneezes or runs to the toilet.

4. If you can't avoid a heartfelt conversation by distracting you with other "more important" things, he may cut you off in the middle and confidently say "you don't have to continue, I understand you" or instead of listening, he begins to give advice, wanting to show off his knowledge. He does not understand that the interlocutor does not need advice, he needs to be heard and get support.

He does not understand that the interlocutor does not need advice, he needs to be heard and get support.

5. It is extremely difficult for such a person to convey that it is wrong to beat children and yell at them. He is dominated by the stereotypes “my father beat me, and nothing, I grew up as a man!”, and it is difficult to convince him of the opposite. The rigidity of thinking and the low threshold of empathy do not allow you to quickly adapt to new trends.

6 . These people never notice betrayal in the family or a protracted conflict. They can only notice that the wife, for some reason, stopped cooking borsch - this will be the reason for the “fight”, because he simply does not see deeper reasons, and will maintain the illusion of a prosperous family to the end.

7. They often blame someone else for their problems, but not themselves. So, for example, a mother says to her daughter, who came to tell her about her dysfunctional life with her husband: “it’s your fault”, “the main thing is that he provides for you”, “solve your own problems, I used to solve it myself and no one thought to help”, “you don’t understand your happiness”, etc.

Even if a mother knows that her son-in-law beats her daughter or rapes her stepfather, she can deny it to the last.

8. These people don't like psychological talk. , they always say that "their own psychologists", and everyone can help with advice. They do give good advice on the practical side of life, but not on the spiritual side.

Once I had a married couple at the reception. The wife wanted to get a divorce, and the husband stubbornly insisted that everything was fine in their family, that they would cope with everything and that they did not need psychological help, refused to take projective tests, etc.

In this aspect psychological protection is triggered - denial . A person denies the existence of any problems in himself or his loved ones, if this can threaten his peace of mind and shake everyday stability.

Such people do not like to leave their comfort zone, they are adherents of traditions, it is very difficult for them to change something in their lives, to adjust to new conditions . They are afraid of pain and the unknown, and therefore every time they take the pose of an ostrich, hiding their heads in the sand of illusions. published

They are afraid of pain and the unknown, and therefore every time they take the pose of an ostrich, hiding their heads in the sand of illusions. published

Cognitive empathy is the ability to enter the inner world of another person, to understand his point of view, his motivation, his goals and aspirations. In general, this is the ability to understand how your interlocutor thinks. Without well-developed cognitive empathy, it is impossible to negotiate at any level, from petty domestic issues to international conflicts.