Borderline personality disorder dsm 5 code

Diagnosing borderline personality disorder - PMC

1. Widiger TA, Weissman MM. Epidemiology of borderline personality disorder. Hosp Community Psychiatry 1991;42:1015–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Zimmerman M, Rothschild L, Chelminski I. The prevalence of DSM-IV personality disorders in psychiatric outpatients. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1911–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Gross R, Olfson M, Gameroff M, et al. Borderline personality disorder in primary care. Arch Intern Med 2002;162:53–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Lenzenweger MF, Lane MC, Loranger AW, Kessler RC. DSM-IV personality disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry 2007;62:553–64 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Gunderson JG, Links PS. Borderline personality disorder: a clinical guide. 2nd ed Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Publishing; 2008. p. 350 [Google Scholar]

6. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Khera GS, et al. Treatment histories of borderline inpatients. Compr Psychiatry 2001;42: 144–50 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. The Surgeon General’s call to action to prevent suicide. Washington (DC): United States Public Health Service; 1999 [Google Scholar]

8. Paris J, Zweig-Frank H. A 27-year follow-up of patients with borderline personality disorder. Compr Psychiatry 2001;42:482–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Paris J, Brown R, Nowlis D. Long-term follow-up of borderline patients in a general hospital. Compr Psychiatry 1987;28:530–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. Time to attainment of recovery from borderline personality disorder and stability of recovery: A 10-year prospective follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:663–7 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Fourth edition. Text revision. Washington (DC): The Association; 2000. p. 943 [Google Scholar]

12. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 3rd ed Washington (DC): The Association; 1980. p. 494 [Google Scholar]

3rd ed Washington (DC): The Association; 1980. p. 494 [Google Scholar]

13. American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed Washington (DC): The Association; 1994. p. 886 [Google Scholar]

14. Stern A. Psychoanalytic Investigation of and therapy in the border line group of neuroses. Psychoanal Q 1938;7:467–89 [Google Scholar]

15. Kernberg OF. A psychoanalytic classification of character pathology. J Am Psychoanal Assoc 1970;18:800–22 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Grinker RR, Werble B. The borderline patient. New York (NY): Jason Aronson Inc.; 1977. p. 226 [Google Scholar]

17. Gunderson JG, Singer MT. Defining borderline patients: an overview. Am J Psychiatry 1975;132:1–10 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Gunderson JG, Kolb JE, Austin V. The diagnostic interview for borderline patients. Am J Psychiatry 1981;138:896–903 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

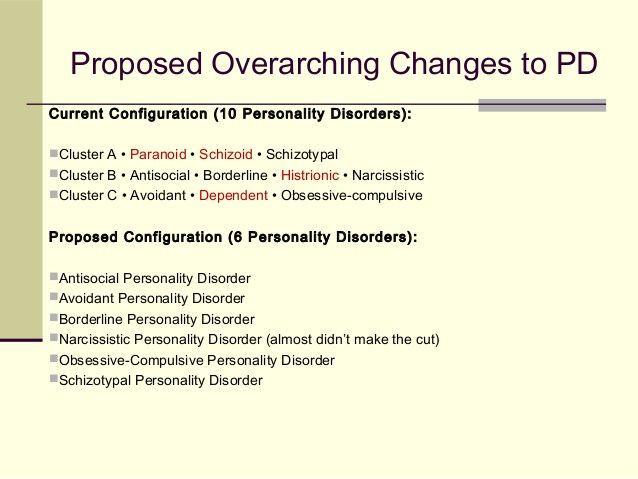

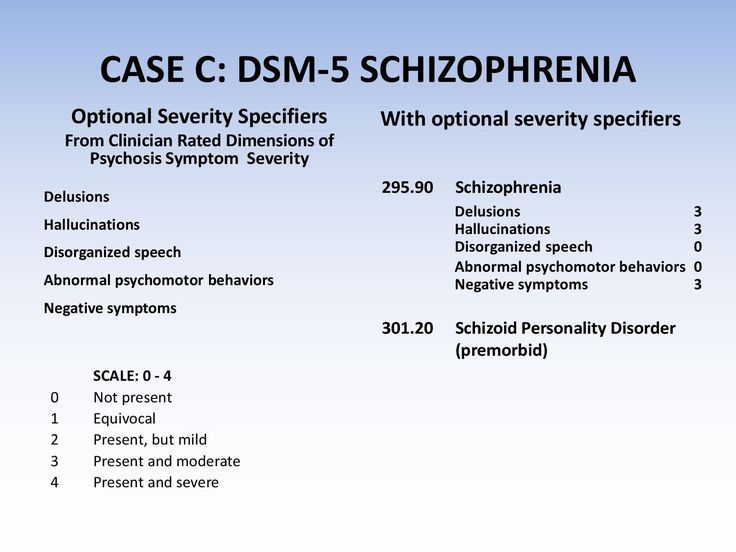

19. Skodol AE, Bender DS, Morey LC, et al. Personality disorder types proposed for DSM-5. J Pers Disord 2011;25:136–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Pers Disord 2011;25:136–69 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

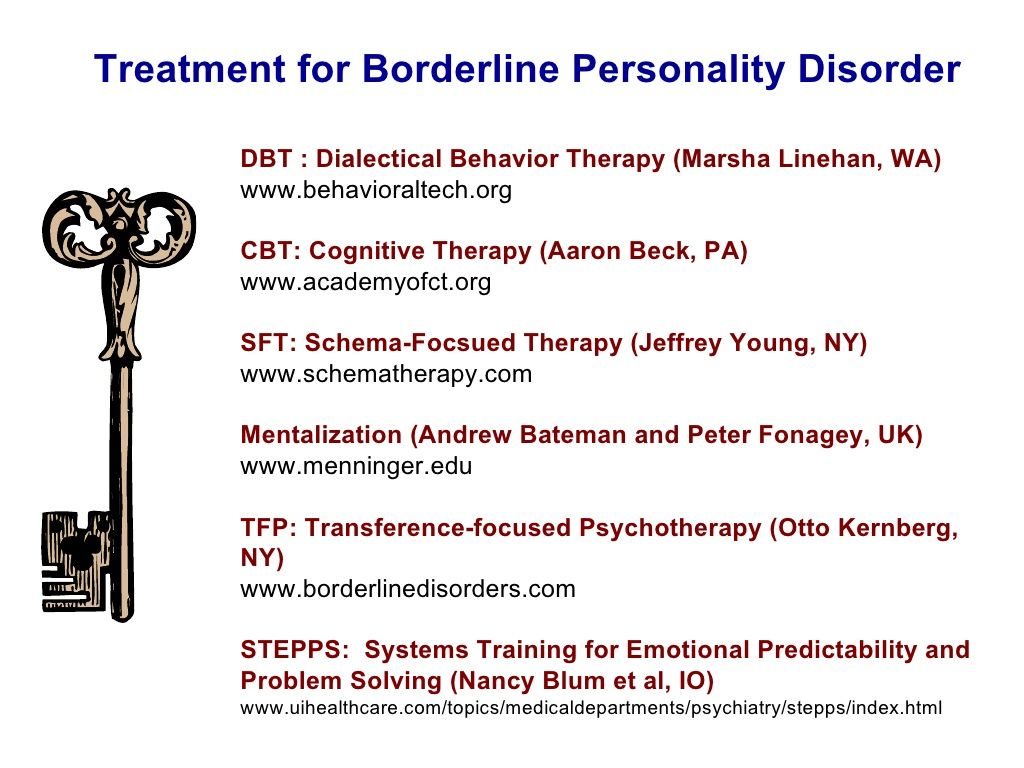

20. Paris J. Treatment of borderline personality disorder: a guide to evidence-based practice. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 2008. p. 260 [Google Scholar]

21. Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR, et al. Discriminating BPD from other axis II disorders. J Pers Disord 1989;3:10–8 [Google Scholar]

22. First MB. User’s guide for the structured clinical interview for DSM-IV axis II personality disorders: SCID-II. Washington (DC): American Psychiatric Press; 1997. p. 91 [Google Scholar]

23. Poreh AM, Rawlings D, Claridge G, et al. The BPQ: a scale for the assessment of borderline personality based on DSM-IV criteria. J Pers Disord 2006;20:247–60 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Arntz A, van den Hoorn M, Cornelis J, et al. Reliability and validity of the Borderline Personality Disorder Severity Index. J Pers Disord 2003;17:45–59 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. A screening measure for BPD: the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord 2003;17:568–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A screening measure for BPD: the McLean Screening Instrument for Borderline Personality Disorder (MSI-BPD). J Pers Disord 2003;17:568–73 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

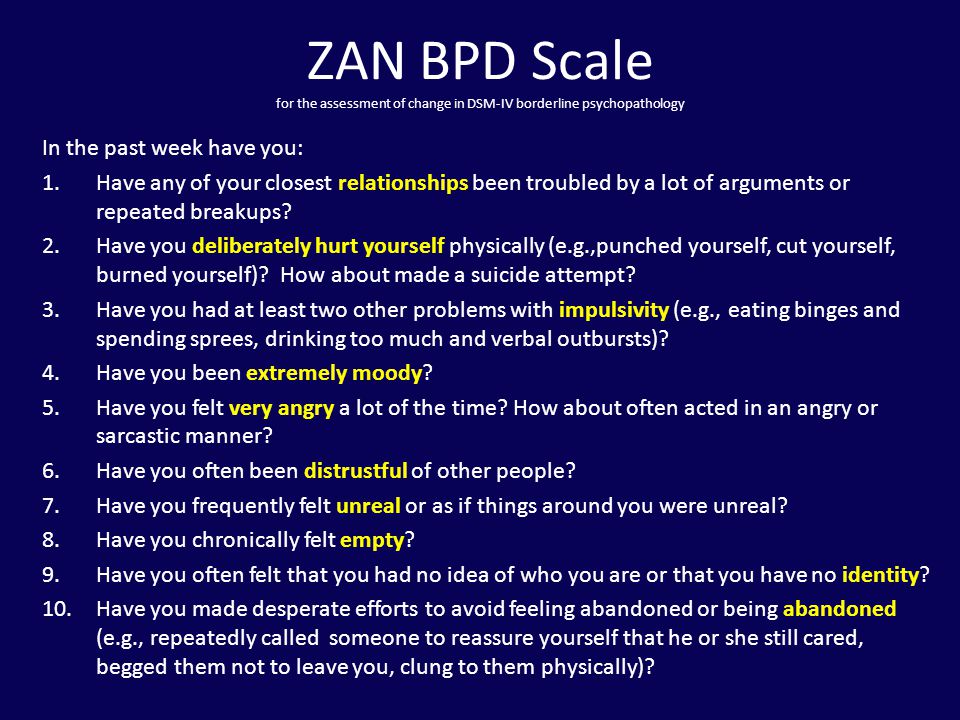

26. Zanarini MC, Vujanovic AA, Parachini EA, et al. Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (ZAN-BPD): a continuous measure of DSM-IV borderline psychopathology [published erratum in J Pers Disord 2003;17:370]. J Pers Disord 2003;17:233–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Zimmerman M, Galione JN, Ruggero CJ, et al. Screening for bipolar disorder and finding borderline personality disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2010;71:1212–7 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Grilo CM, McGlashan TH, Skodol AE. Stability and course of personality disorders: the need to consider comorbidities and continuities between axis I psychiatric disorders and axis II personality disorders. Psychiatr Q 2000;71:291–307 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Paris J. Personality disorders over time: precursors, course and outcome. J Pers Disord 2003;17:479–88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Pers Disord 2003;17:479–88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Tracie Shea M, Edelen MO, Pinto A, et al. Improvement in borderline personality disorder in relationship to age. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2009;119:143–8 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, et al. The subsyndromal phenomenology of borderline personality disorder: a 10-year follow-up study. Am J Psychiatry 2007;164:929–35 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Goodwin FK, Jamison KR, Ghaemi SN. Manic–depressive illness: bipolar disorders and recurrent depression. 2nd ed New York (NY): Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 1262 [Google Scholar]

33. Nica EI, Links PS. Affective instability in borderline personality disorder: experience sampling findings. Curr Psychiatry Rep 2009;11:74–81 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Stiglmayr CE, Shapiro DA, Stieglitz RD, et al. Experience of aversive tension and dissociation in female patients with borderline personality disorder: a controlled study. J Psychiatr Res 2001; 35:111–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Psychiatr Res 2001; 35:111–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Henry C, Mitropoulou V, New AS, et al. Affective instability and impulsivity in borderline personality and bipolar II disorders: similarities and differences. J Psychiatr Res 2001;35:307–12 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Solhan MB, Trull TJ, Jahng S, et al. Clinical assessment of affective instability: comparing EMA indices, questionnaire reports, and retrospective recall. Psychol Assess 2009;21:425–36 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Stiglmayr CE, Grathwol T, Linehan MM, et al. Aversive tension in patients with borderline personality disorder: a computer-based controlled field study. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2005;111:372–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Zeigler-Hill V, Abraham J. Borderline personality features: instability of self-esteem and affect. J Soc Clin Psychol 2006;25:668–87 [Google Scholar]

39. Russell JJ, Moskowitz DS, Zuroff DC, et al. Stability and variability of affective experience and interpersonal behavior in borderline personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol 2007;116:578–88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Abnorm Psychol 2007;116:578–88 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Trull TJ, Solhan MB, Tragesser SL, et al. Affective instability: measuring a core feature of borderline personality disorder with ecological momentary assessment. J Abnorm Psychol 2008;117:647–61 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Johansen M, Karterud S, Pedersen G, et al. An investigation of the prototype validity of the borderline DSM-IV construct. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2004;109:289–98 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Klonsky ED. What is emptiness? Clarifying the 7th criterion for borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 2008;22:418–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Rogers JH, Widiger TA, Krupp A. Aspects of depression associated with borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1995; 152:268–70 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Zaheer J, Links PS, Liu E. Assessment and emergency management of suicidality in personality disorders. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2008;31:527–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Ridolfi ME, et al. Reported childhood onset of self-mutilation among borderline patients. J Pers Disord 2006;20:9–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Ridolfi ME, et al. Reported childhood onset of self-mutilation among borderline patients. J Pers Disord 2006;20:9–15 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York (NY): Guilford Press; 1993. p. 558 [Google Scholar]

47. Bongar B, Peterson LG, Golann S, et al. Self-mutilation and the chronically suicidal patient: an examination of the frequent visitor to the psychiatric emergency room. Ann Clin Psychiatry 1990;2:217–22 [Google Scholar]

48. Forman EM, Berk MS, Henriques GR, et al. History of multiple suicide attempts as a behavioral marker of severe psychopathology. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:437–43 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. McGlashan TH, Grilo CM, Skodol AE, et al. The Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorders Study: baseline axis I/II and II/II diagnostic co-occurrence. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2000;102: 256–64 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. McGirr A, Paris J, Lesage A, et al. Risk factors for suicide completion in borderline personality disorder: a case–control study of cluster B comorbidity and impulsive aggression. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:721–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Risk factors for suicide completion in borderline personality disorder: a case–control study of cluster B comorbidity and impulsive aggression. J Clin Psychiatry 2007;68:721–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Fossati A, Maffei C, Bagnato M, et al. Latent structure analysis of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder criteria. Compr Psychiatry 1999;40:72–9 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Westen D, Betan E, Defife JA. Identity disturbance in adolescence: associations with borderline personality disorder. Dev Psychopathol 2011;23:305–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Zanarini MC, Gunderson JG, Frankenburg FR. Cognitive features of borderline personality disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1990; 147:57–63 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Zlotnick C, Johnson DM, Yen S, et al. Clinical features and impairment in women with borderline personality disorder (BPD) with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), BPD without PTSD, and other personality disorders with PTSD. J Nerv Ment Dis 2003;191:706–13 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Newton-Howes G, Tyrer P, Johnson T. Personality disorder and the outcome of depression: meta-analysis of published studies. Br J Psychiatry 2006;188:13–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Newton-Howes G, Tyrer P, Johnson T. Personality disorder and the outcome of depression: meta-analysis of published studies. Br J Psychiatry 2006;188:13–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. McDonald-Scott P, Machizawa S, Satoh H. Diagnostic disclosure: a tale in two cultures. Psychol Med 1992;22:147–57 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. A preliminary, randomized trial of psychoeducation for women with borderline personality disorder. J Pers Disord 2008;22:284–90 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Lequesne ER, Hersh RG. Disclosure of a diagnosis of borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Pract 2004;10:170–6 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Bateman A, Fonagy P. Psychotherapy for borderline personality disorder: mentalization-based treatment. Oxford (UK): Oxford University Press; 2004. p. 381 [Google Scholar]

60. Biskin RS, Paris J, Renaud J, et al. Outcomes in women diagnosed with borderline personality disorder in adolescence. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;20:168–74 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Stepp SD, Pilkonis PA, Hipwell AE, et al. Stability of borderline personality disorder features in girls. J Pers Disord 2010;24:460–72 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Stepp SD, Pilkonis PA, Hipwell AE, et al. Stability of borderline personality disorder features in girls. J Pers Disord 2010;24:460–72 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Chanen AM, McCutcheon LK, Germano D, et al. The HYPE Clinic: an early intervention service for borderline personality disorder. J Psychiatr Pract 2009;15:163–72 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Gunderson JG. Revising the borderline diagnosis for DSM-V: an alternative proposal. J Pers Disord 2010;24:694–708 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Hopwood CJ, Malone JC, Ansell EB, et al. Personality assessment in DSM-5: empirical support for rating severity, style, and traits. J Pers Disord. 2011;25:305–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Biskin RS, Paris J. Management of borderline personality disorder. CMAJ 2012; Oct. 1 [Epub ahead of print]. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Borderline | Personality disorder

What is borderline personality disorder (BPD)?

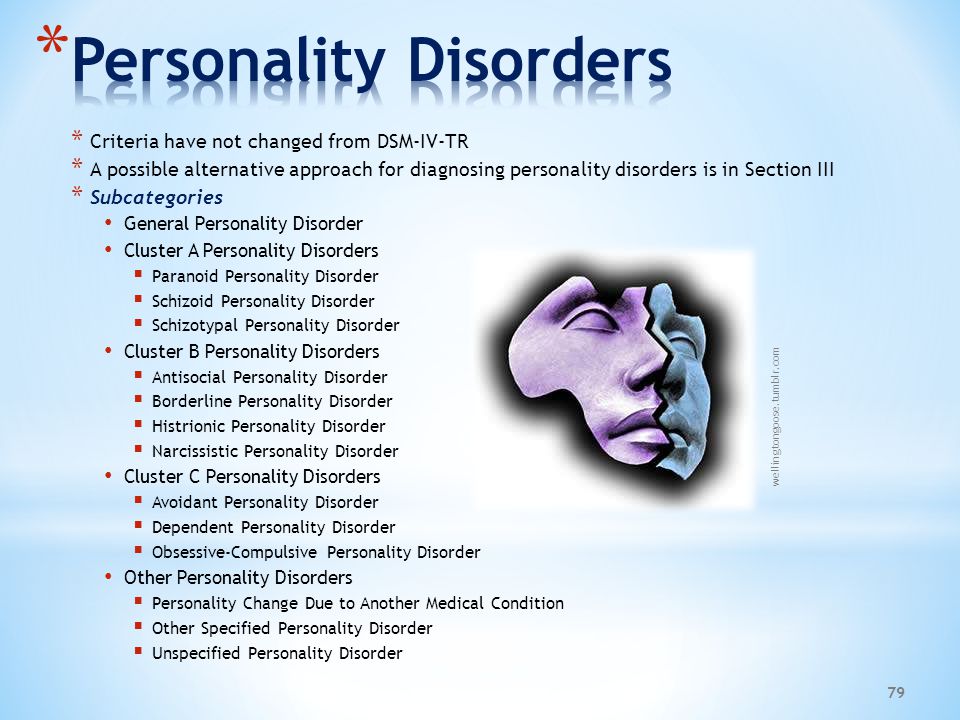

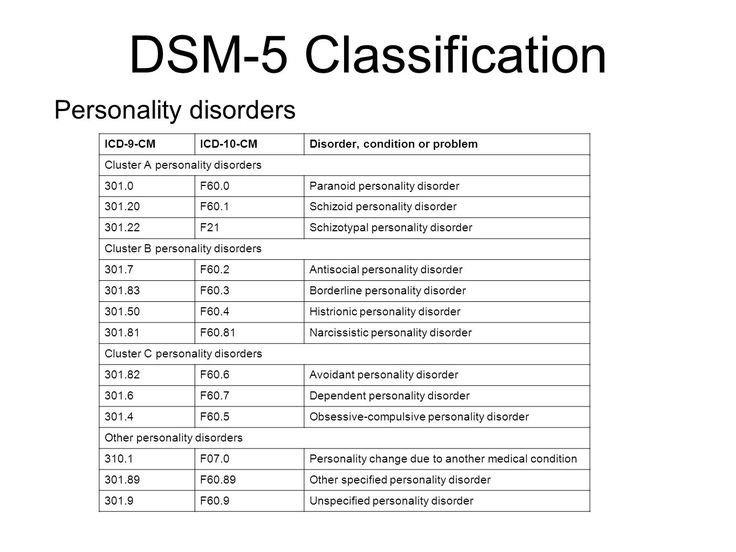

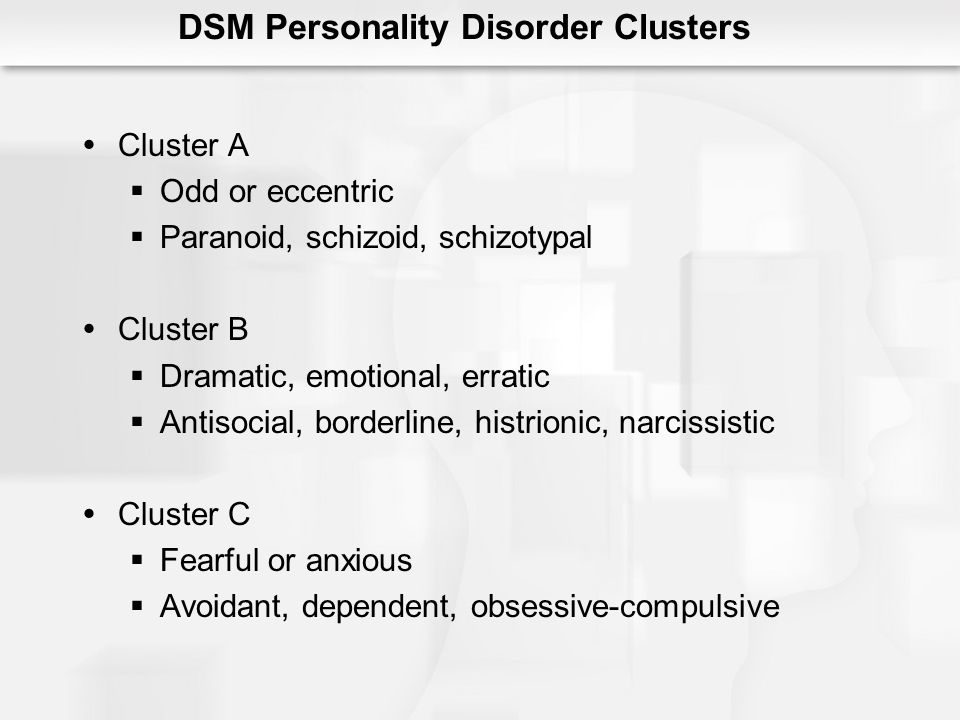

There is confusion around the diagnosis of BPD, known in the WHO classification (ICD-10) as Emotionally unstable personality disorder, borderline type. In order to understand the nature of the disorder, a word about personality disorders (PDs) in general is necessary, as BPD is in some ways unique among PDs.

In order to understand the nature of the disorder, a word about personality disorders (PDs) in general is necessary, as BPD is in some ways unique among PDs.

Personality disorders are a group of mental health difficulties that are present throughout a persons life, and are part of their normal way of relating with other people, and thinking of themselves – and the actions that stem from this. They are disorders in that they cause suffering, either to the person themselves or (less commonly) those around them. Not everyone with a PD seeks help, in fact most probably do not; like most disorders, a PD can be more or less severe, and cause more problems at particular times of life, such as during transitions (leaving home, changing job, loss events). About 5% of the population of the UK would be diagnosed with a PD of some sort (there are 9 or 10 types depending on the classification system used) if they presented to a psychiatrist, which gives an indication of how few actually do. As a comparison, this is five times as many as suffer with schizophrenia, very few of whom do not receive a diagnosis and treatment at some point in their lives if they live in the developed world. There is debate about whether PDs should be classified with other mental illnesses, as they differ in important ways: they tend to be lifelong and consistent, or stable, throughout most of that time; in other words they seem more like a part of the way the person is constituted than an illness visited upon them. In this they may appear to resemble autistic spectrum disorder or differences in a continuous variable such as IQ more than for example schizophrenia or depression.

As a comparison, this is five times as many as suffer with schizophrenia, very few of whom do not receive a diagnosis and treatment at some point in their lives if they live in the developed world. There is debate about whether PDs should be classified with other mental illnesses, as they differ in important ways: they tend to be lifelong and consistent, or stable, throughout most of that time; in other words they seem more like a part of the way the person is constituted than an illness visited upon them. In this they may appear to resemble autistic spectrum disorder or differences in a continuous variable such as IQ more than for example schizophrenia or depression.

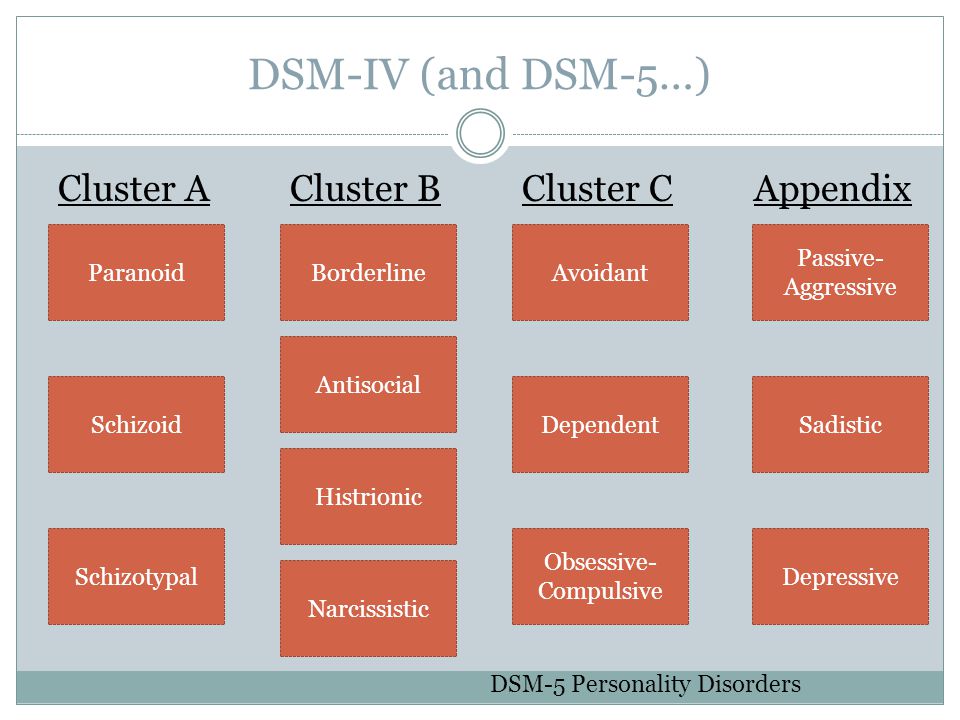

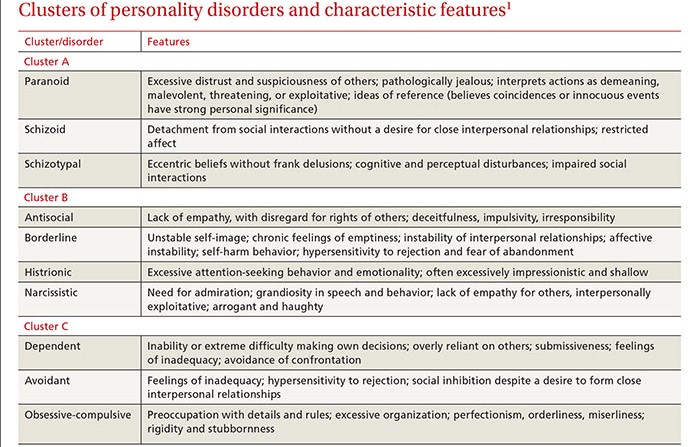

The ICD-10 lists the personality disorders as follows:

F60 Specific personality disorders

F60.0 Paranoid personality disorder

F60.1 Schizoid personality disorder

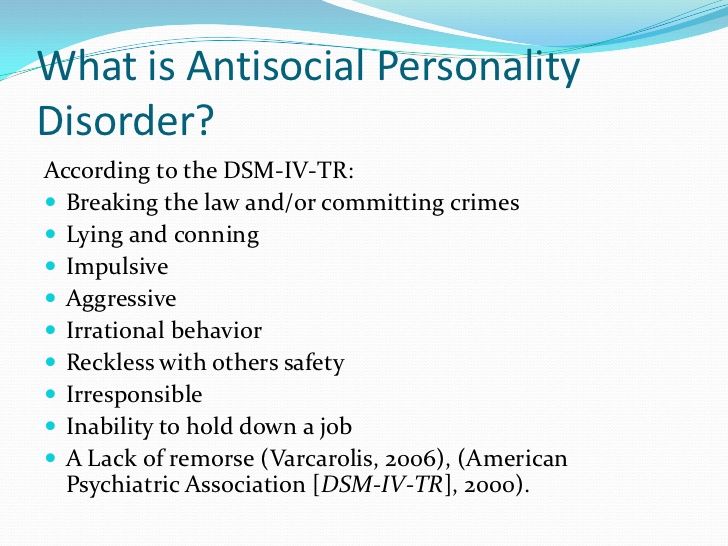

F60.2 Dissocial personality disorder

F60.3 Emotionally unstable personality disorder

.30 Impulsive type

.31 Borderline type

F60. 4 Histrionic personality disorder

4 Histrionic personality disorder

F60.5 Anankastic personality disorder

F60.6 Anxious [avoidant] personality disorder

F60.7 Dependent personality disorder

F60.8 Other specific personality disorders

F60.9 Personality disorder, unspecified

Borderline personality disorder differs from the other PDs in important ways. It is probably less stable and lifelong than other PDs, although this may be an artefact of the larger body of research devoted to BPD. It appears to be less pervasive, meaning people with BPD tend not to present in the same way in different situations. This is curious, as pervasiveness is a central element of the personality disorders. People with BPD are also more likely to seek treatment than people with other PD diagnoses; the majority of people receiving treatment in specialist centres suffer from BPD, often with one or more other PDs.

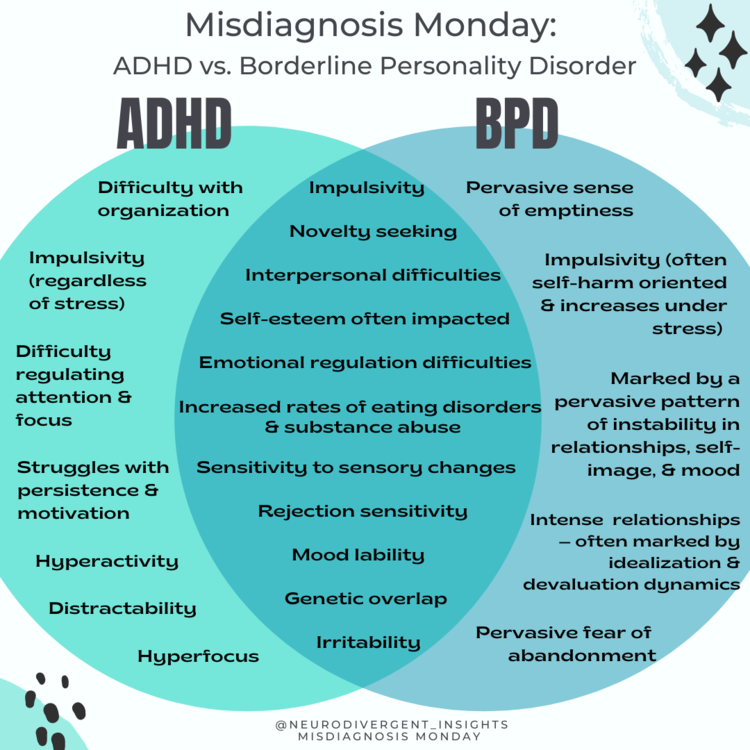

The most prominent features of BPD are self harm/suicidality, emotional instability (unpredictable variations in mood, both sad/happy and angry/irritable), impulsivity (doing things on impulse without due consideration of the consequences) and disordered attachment (stormy relationships, very strong feelings of abandonment when a close relationship ends). It is the first two of these that most commonly lead to people seeking help.

It is the first two of these that most commonly lead to people seeking help.

The International Classification of Diseases 10 of the World Health Organisation (ICD-10) includes the following description of emotional unstable personality disorder:

F60.3 Emotionally unstable personality disorder

A personality disorder in which there is a marked tendency to act impulsively without consideration of the consequences, together with affective instability. The ability to plan ahead may be minimal, and outbursts of intense anger may often lead to violence or “behavioural explosions”; these are easily precipitated when impulsive acts are criticised or thwarted by others. Two variants of this personality disorder are specified, and both share this general theme of impulsiveness and lack of self-control.

F60.30 Impulsive type

The predominant characteristics are emotional instability and lack of impulse control. Outbursts of violence or threatening behaviour are common, particularly in response to criticism by others.

F60.31 Borderline type

Several of the characteristics of emotional instability are present; in addition, the patient’s own self-image, aims, and internal preferences (including sexual) are often unclear or disturbed. There are usually chronic feelings of emptiness. A liability to become involved in intense and unstable relationships may cause repeated emotional crises and may be associated with excessive efforts to avoid abandonment and a series of suicidal threats or acts of self-harm (although these may occur without obvious precipitants).

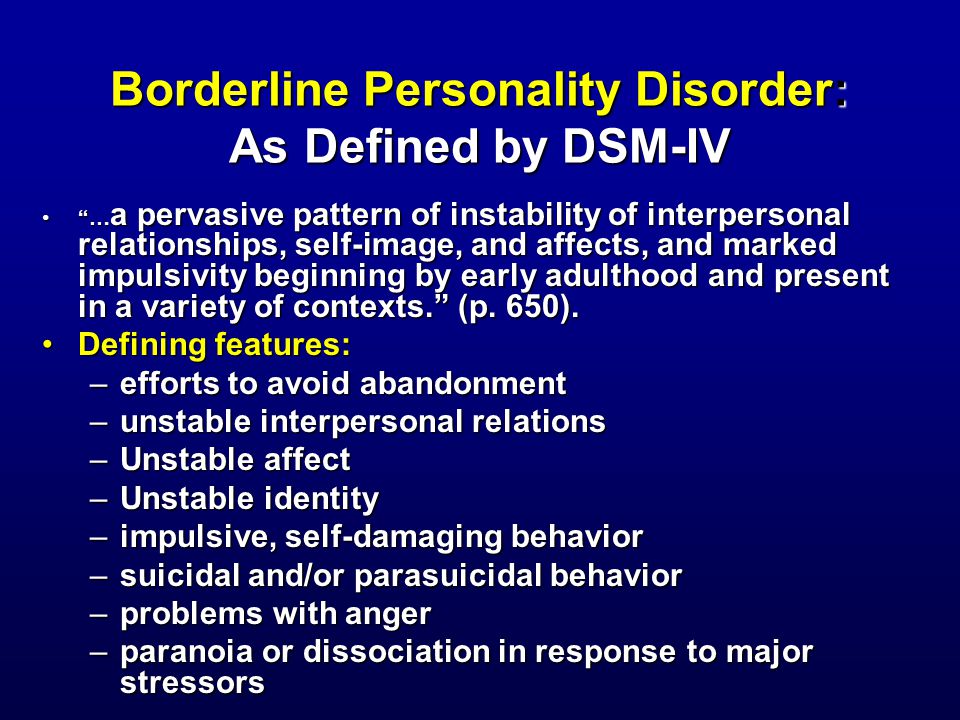

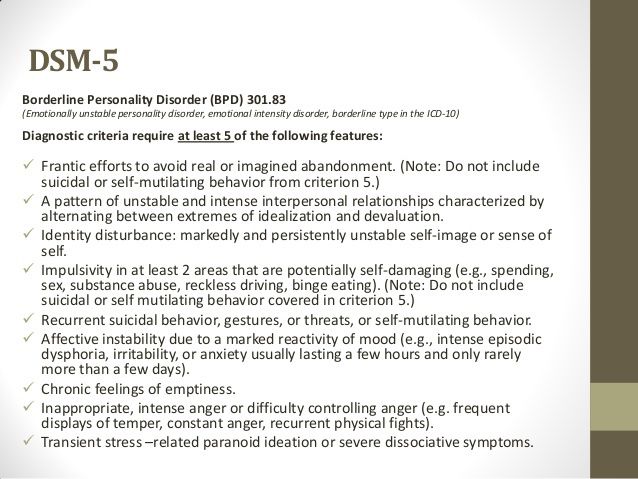

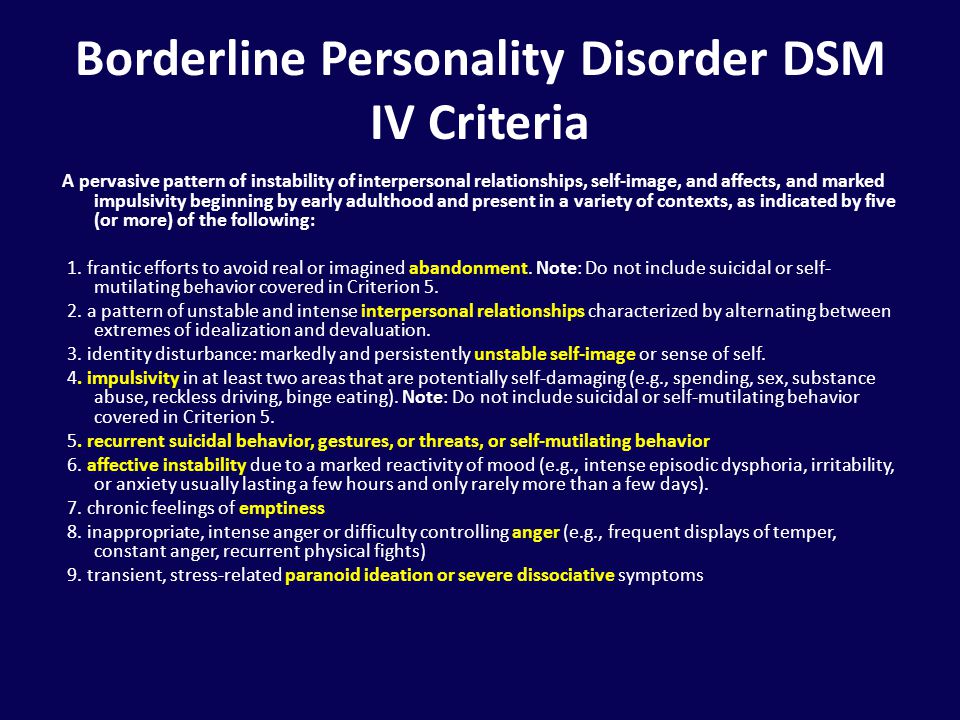

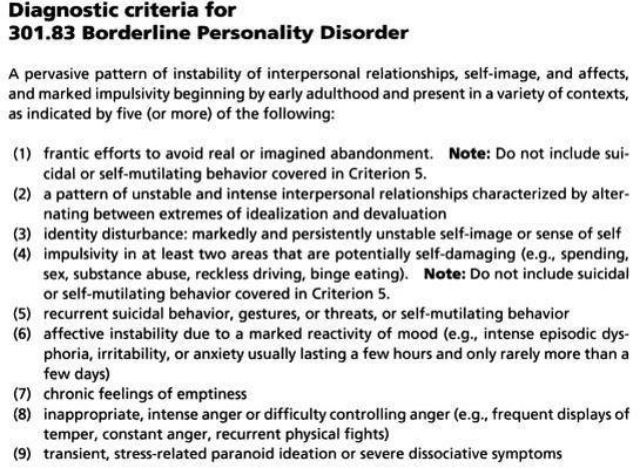

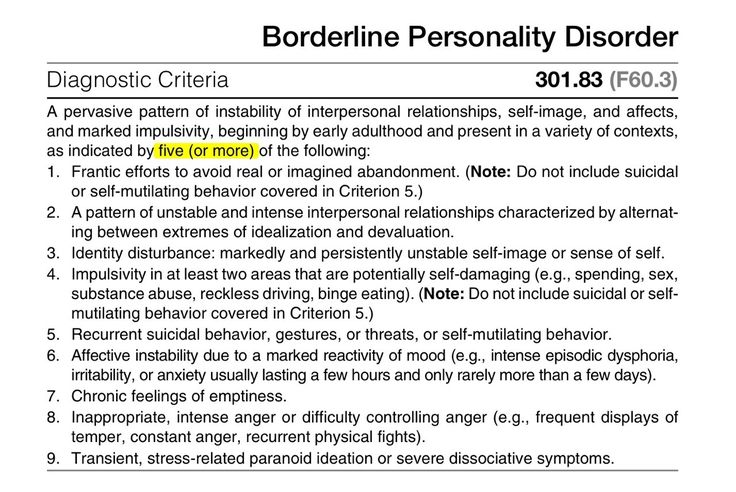

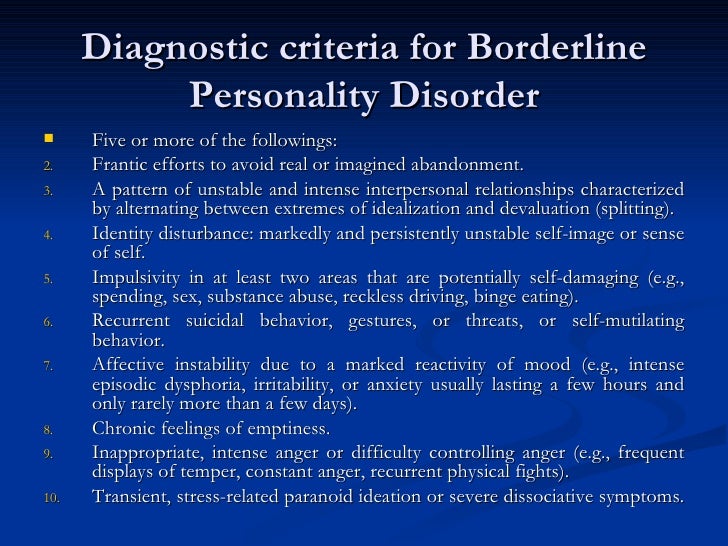

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of the American Psychiatric Association (DSM 5) specifies 5 out of the following 9 symptoms must be present for the diagnosis to be made:

- Frantic efforts to avoid real or imagined abandonment. Note: Do not include suicidal or self-mutilating behavior covered in Criterion 5.

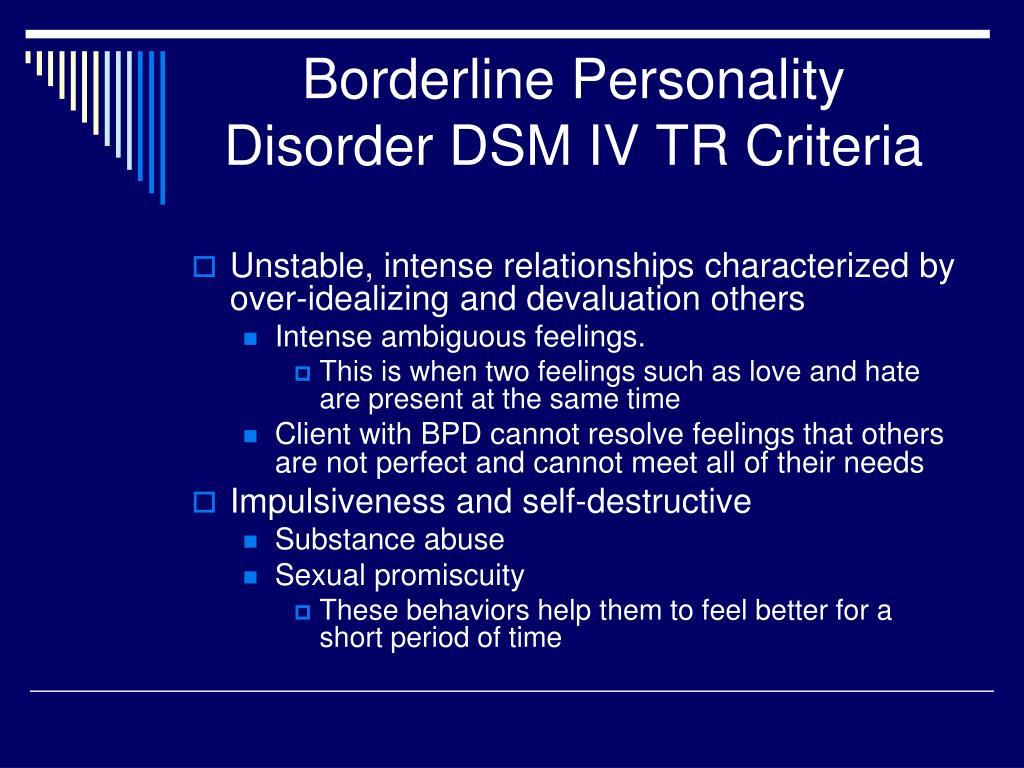

- A pattern of unstable and intense interpersonal relationships characterized by alternating between extremes of idealization and devaluation.

- Identity disturbance: markedly and persistently unstable self image or sense of self.

- Impulsivity in at least two areas that are potentially self- damaging (e.g., spending, sex, substance abuse, reckless driving, binge eating). Note: Do not include suicidal or self- mutilating behavior covered in Criterion 5.

- Recurrent suicidal behavior, gestures, or threats, or self- mutilating behavior.

- Affective instability due to a marked reactivity of mood (e.g., intense episodic dysphoria, irritability, or anxiety usually lasting a few hours and only rarely more than a few days).

- Chronic feelings of emptiness.

- Inappropriate, intense anger or difficulty controlling anger (e.g., frequent displays of temper, constant anger, recurrent physical fights).

- Transient, stress-related paranoid ideation or severe dissociative symptoms.

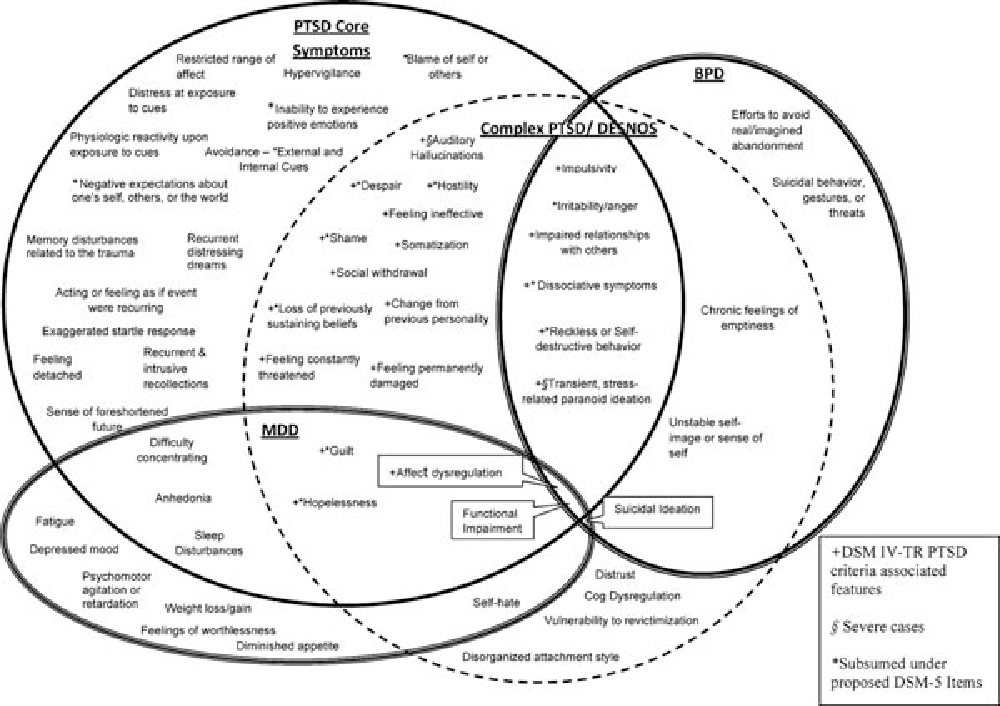

There is some debate about whether BPD should continue to be regarded as a single entity, as it can appear to be a collection of symptoms which happen to occur together in a group of people but perhaps as commonly occur separately, and that labelling them as a syndrome when occurring together does not add much to our understanding. A similar argument occurs about PDs as a whole, as comorbidity is so common (i.e. if you have one you are very likely to have more than one), and statistical experiments sometimes fail to identify the PDs (or indeed BPD) in the population (through for example cluster analyses). To widen matters further, following the publication of DSM 5, the usefulness of the term schizophrenia was called into question by the British Psychological Society. These debates are not uncommon in psychiatry.

A similar argument occurs about PDs as a whole, as comorbidity is so common (i.e. if you have one you are very likely to have more than one), and statistical experiments sometimes fail to identify the PDs (or indeed BPD) in the population (through for example cluster analyses). To widen matters further, following the publication of DSM 5, the usefulness of the term schizophrenia was called into question by the British Psychological Society. These debates are not uncommon in psychiatry.

Borderline Personality Disorder

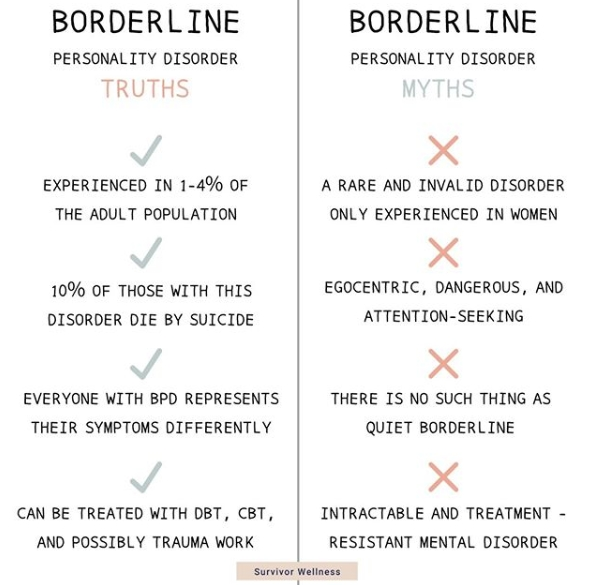

The clinical category "Borderline Personality Disorder" is attracting the growing attention of researchers and public health officials around the world.

ICD-10. ICD-10 classifies borderline personality disorder as a subset of emotionally unstable personality disorder.

The characteristics of BPD are more clearly defined in the American DSM-5 classification of mental disorders, and therefore the bulk of the world literature on this disorder is based on the DSM-V definition of BPD:

DSM - V . According to the DSM-V, features of borderline personality disorder include marked instability in interpersonal relationships, self-image, emotional instability, and marked impulsivity. All signs of the disorder occur at a young age and manifest themselves in various situations. Diagnosis requires the presence, in addition to the general criteria for a personality disorder, five (or more) of the following:

According to the DSM-V, features of borderline personality disorder include marked instability in interpersonal relationships, self-image, emotional instability, and marked impulsivity. All signs of the disorder occur at a young age and manifest themselves in various situations. Diagnosis requires the presence, in addition to the general criteria for a personality disorder, five (or more) of the following:

Note: Do not include suicidal behavior and acts of self-harm described in Criterion 5.

Note: Do not include suicidal behavior and acts of self-harm described in Criterion 5. The lives of people with borderline personality disorder are often filled with agonizing emotional swings, relationship problems, self-harmful behavior, and chronic suicidality. nine0042

Women suffer from BPD significantly more often than men.

Issue: BPD burden

- BPD is considered in the world literature as one of the most costly categories of mental disorders;

- According to current epidemiological studies, up to 6% of the adult population in developed countries suffers from BPD;

- 20% of psychiatric patients meet a diagnosis of BPD according to DSM-5 criteria; nine0022

- 10% of outpatient mental patients meet the diagnosis of BPD;

- BPD patients account for up to 50% of all patients, the most active use of mental health services resources;

- 10% of BPD patients complete suicide (50 times more than the general population)

- Highest risk of suicide among all mental disorders (for women), and second highest risk of suicide among all mental disorders in men; nine0021 According to post-mortem psychological examination, up to 1/3 of suicides are committed by people with BPD.

Borderline personality disorder signs and symptoms • Psychologist Yaroslav Isaikin

According to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders

According to DSM-V, signs of borderline personality disorder include severe instability in interpersonal relationships, self-image, emotional instability, and pronounced impulsiveness. nine0003

All signs of the disorder begin at a young age and appear in a variety of situations.

Diagnosis requires five (or more) of the following in addition to the general criteria for a personality disorder:

- A tendency to exert excessive effort to avoid a real or imagined fate being abandoned . Note: Do not include suicidal behavior and acts of self-harm described in Criterion 5.

- Tendency to engage in intense, tense and unstable relationships characterized by alternation of extremes - idealization and devaluation.

- Identity disorder: noticeable and persistent instability of the image or feeling of the self.

- Impulsivity in at least two areas that involve self-harm (eg, spending money, sexual behavior, substance abuse, traffic violations, habitual overeating). Note: Do not include suicidal behavior and acts of self-harm described in Criterion 5.

- Recurrent suicidal behavior, hints or threats of suicide, acts of self-harm .

- Affective instability, very changeable mood (for example, periods of intense dysphoria, irritability or anxiety, usually lasting for several hours and only occasionally for several days or more).

- Constantly experienced feeling of emptiness .

- Inappropriate manifestations of intense anger or difficulty controlling anger (eg, frequent irritability, persistent anger, repeated fights).

- Transient stress-induced paranoid ideas or severe dissociative symptoms

Behavioral patterns in Borderline Personality Disorder (Marsha M. Linehan)

Linehan)

- Emotional vulnerability - significant difficulty in regulating negative emotions, including high sensitivity to negative emotional stimuli and slow return to normal emotional state and a sense of their own emotional vulnerability. May include a tendency to blame the social environment for unrealistic expectations and demands. nine0022

- Self-invalidation - tendency to ignore or deny, not to recognize one's own emotional reactions, thoughts, ideas and behavior. Unrealistically high standards and expectations are being set. May include intense shame, self-hatred, and self-directed anger.

- Ongoing crisis – model of frequent stressful, negative environmental events, breakdowns and obstacles, some of which arise as a result of an individual's dysfunctional lifestyle, inadequate social environment or random circumstances. nine0022

- Repressed feelings - The tendency to suppress and over-control negative emotional reactions - especially those associated with grief and loss, including sadness, anger, guilt, shame, anxiety and panic.

- Active passivity - a tendency to a passive style of solving interpersonal problems, including the inability to actively overcome the difficulties of life, often in combination with vigorous attempts to involve members of one's environment in solving one's own problems; learned helplessness is the lack of motivation for an individual to respond by action in situations where there is a real opportunity to improve the situation. nine0022

- Perceived competence - the tendency of an individual to appear more competent than he actually is; usually explained by the inability to generalize the characteristics of mood, situation and time; also the inability to demonstrate adequate non-verbal signals of emotional distress.

Take the BPD probability test

Clinical Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder (Dmitry Romanov)

Allows the diagnosis of BPD based on consideration of signs that are easily identified through an appropriate question asked to the patient by a doctor (features 2-13), as well as based on the assessment of the patient's behavior during the interview (sign 15). Confident diagnosis of BPD is carried out when registering a total score of 12 points or more. nine0003

Confident diagnosis of BPD is carried out when registering a total score of 12 points or more. nine0003

1. Female

Most studies indicate that BPD is more common in females. Recent studies of BPD demonstrate the predominance of females compared to males by almost 2 times (Wang L., Ross C. A., Zhang T., Dai Y., Xiao, Z., 2012). In addition, women with BPD seek specialized help more often than men, which, in particular, is due to gender differences in social rules of behavior.

2. Presence of a situation of violence in childhood and adolescence 9(Goldberg D., 2010) one and parents, etc.)

A frequently observed anamnestic symptom of BPD is associated with the subsequent formation of gender identity disorders in patients (Kernberg O., 1975)

4. Hostility towards one of the parents

5. Early separation (for example, early marriage, leaving the parental home after reaching the age of majority)

due to the existing defect of formation, they are incapable of complete separation and often experience hostile feelings towards the parent, with whom separation problems are associated, as well as towards the marriage partner. Patients are characterized by an overvalued desire to free themselves from the control of significant persons (McWilliams N., 1994)

Patients are characterized by an overvalued desire to free themselves from the control of significant persons (McWilliams N., 1994)

7. History of self-harm/suicide

Almost all researchers call this diagnostic feature as an obligate criterion for BPD (Lainen M., 2008). Clinical diagnostic criterion DSM-V

8. History of at least one episode of brutal aggressive behavior (attack, destruction of things)

Behavioral equivalent of the DSM diagnostic criterion 5

consequences

An extremely high association of BPD and substance use disorders has been shown, reaching 73% (B. Grant et al., 2008)

Frequently noted by investigators BPD

11. More than one marriage (including common-law marriage)

Associated with the inability of patients with BPD to establish long-term relationships based on trust (see relevant DSM diagnostic criterion 5)

12.