Borderline personality disorder attachment issues

Attachment Styles and Borderline Personality Disorder

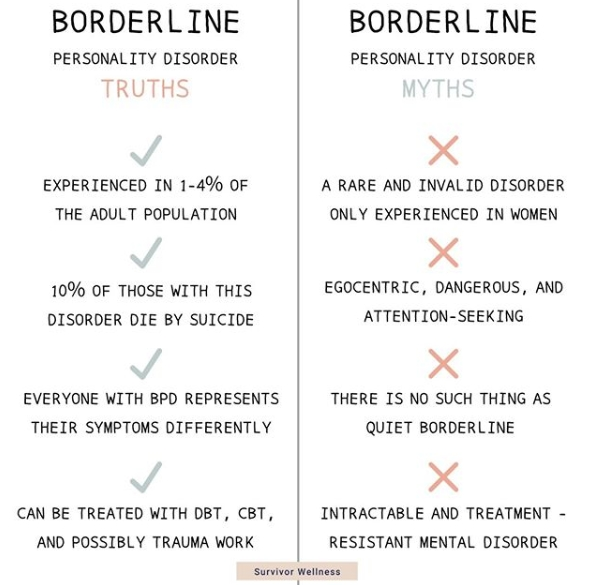

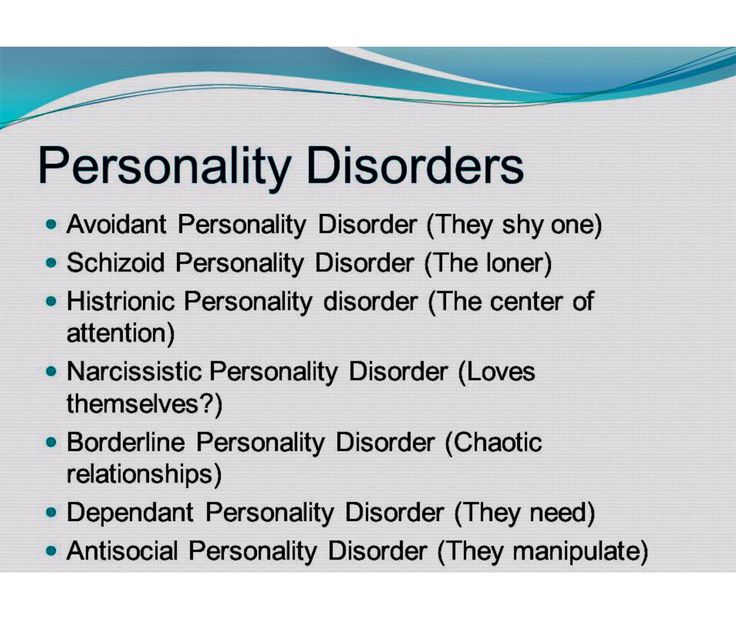

We cannot paint everyone with borderline personality disorder with a single brushstroke. Even though people may carry the same diagnostic label, their unique life experiences and innate temperaments will create different coping styles and thus symptom profiles.

In this article, we will review how different attachment styles may affect your push-pull behaviors and explain various BPD symptoms.

Attachment Styles and Adaptation Strategies

Our parents' responses to our attachment-seeking behaviors shape how we see the world later in life.

In the most ideal scenario, we would have had attachment interactions with someone loving, attuned, and nurturing, who can mirror our emotions back to us accurately and does not ask us to carry their distress. That will be how we develop a sense of safety and trust for those around us. We would internalize the message that the world is a friendly place; we trust that someone will be there for us when we are in need.

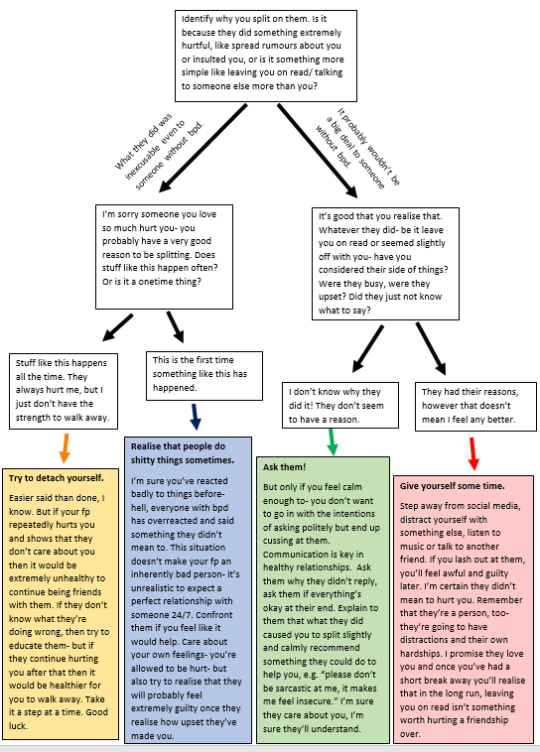

However, if the message that we were given by our caregivers was that the world was unsafe, it could affect our ability to withstand uncertainty in life. Since we may feel unable to sit with any ambiguity in communication, we may demand constant reassurance, quickly flip into black-or-white thinking, feel the impulse to end everything, or plunge into despair whenever conflict arises.

Attachment theory was originally developed by John Bowlby (1907-1990), who started by observing how infants react to being separated from their parents. Psychologists found that without conscious intervention, we tend to stick with our childhood attachment styles. To put it simply, if we have an anxious attachment pattern, we might become attached and clingy; if we have an avoidant attachment pattern, we tend to cut off to protect ourselves.

What Are the Main Attachment Styles?

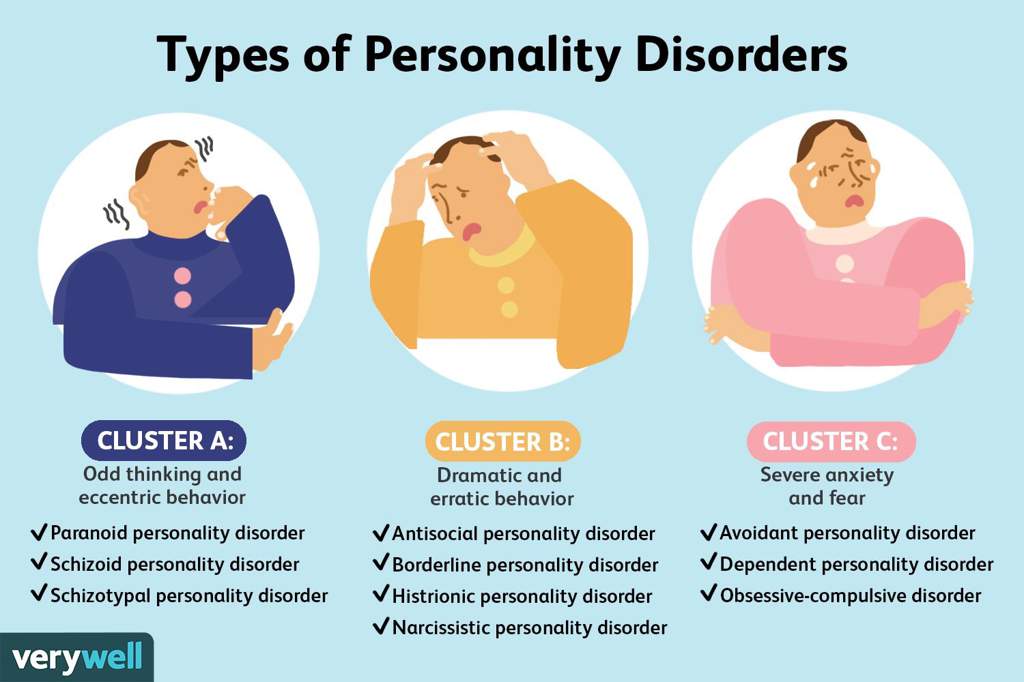

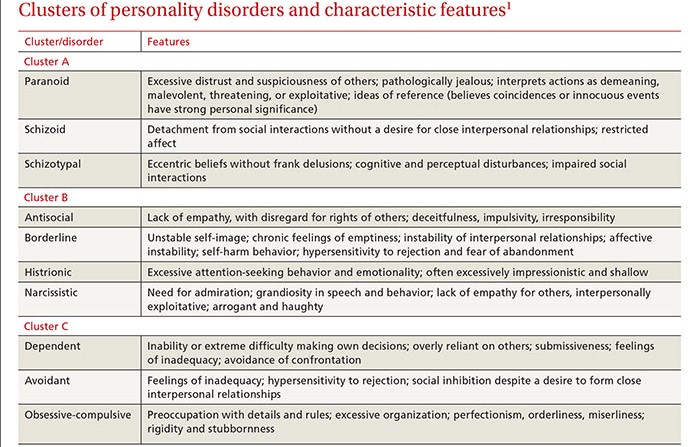

There are four main attachment styles. They can be understood via where they fall on two dimensions: anxiety and avoidance (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver,1998).

1. Secure attachment

Securely attached individuals who are low on both anxiety and avoidance. They tend to view themselves positively and believe that they are worthy of care. They usually grew up in a supportive environment where parents were responsive to their needs. Securely attached people are usually flexible, open, and warm. They can be vulnerable and express emotions in front of others.

2. Anxious-preoccupied (anxious) attachment

People who are high on the anxiety dimension are more likely to have a negative view of themselves. If you are anxiously attached, it means that your upbringing has caused you to believe you were unworthy of love and care. You crave intimacy and approval, yet fear rejection and abandonment.

You have developed this form of attachment likely because your parents were or continue to be inconsistent with their emotional availability and responses. Maybe at times, they were nurturing. Other times, or as their mood changed, they flipped to being cold, rejecting, detached, or even cruel. You never knew what to expect. This results in a hyper-vigilant psyche—at every moment, you feel like you have to watch out for any signs of change in the relationship dynamics.

You never knew what to expect. This results in a hyper-vigilant psyche—at every moment, you feel like you have to watch out for any signs of change in the relationship dynamics.

As an anxious child, you sought constant assurance, approval, and attention from others, and as an adult, you may demand these from your partners. You have an intense need for contact and connection, which can come across as being dependent or clingy. You struggle with the idea of object constancy and experience constant fear of abandonment. You are highly aware of the smallest hint that others may be angry, upset, or pulling back from you. When you feel insecure, you cannot help but react with fear, anger, and a desperate search for contact, validation, and connection.

You tend to struggle more with maladaptive dependency. You may sacrifice your own needs for that of others, and find it difficult to trust your ability to endure or enjoy solitude.

Anxiously attached individuals with borderline personality disorder may relate more to the descriptions of "classic" BPD, where the fear of abandonment and instability in interpersonal relationships are core features.

3. Dismissive-avoidant (avoidant) attachment

Individuals high on the avoidance dimension have developed negative views of others. If you are avoidantly attached, you learned through experience that people could not be counted on, and you have to rely only on yourself.

You tend to minimize or downplay painful feelings. You may not remember much of your childhood and feel uncomfortable speaking about it. Normalizing, intellectualizing, and rationalizing painful events are your core coping mechanisms.

Children develop this attachment style when their primary caregivers are not responsive to or reject their needs. You eventually become uncomfortable with emotional openness and you deny the need for intimacy even to yourself. You place a high value on independence and autonomy and would do all you can to avoid feeling overwhelmed, engulfed, and controlled. You may recognize the value of relationships and even have a strong desire for them, but have difficulty trusting others.

If you have this attachment style and BPD, you may relate more to descriptions of quiet BPD or high-functioning BPD. In quiet BPD, you turn your pain inward and hurt yourself rather than lash out at others. In high-functioning BPD, you shield your conscious and unconscious anxieties and relational wound with a facade of normalcy.

In both cases, your deepest pain remains buried. Both your yearnings and fears remain unseen—not just to others but even yourself. While you may seem to function "normally" in your day-to-day life, inside you feel numb, as though you are running on an auto-pilot. The emptiness and loneliness wear on your conscience day after day, and however much you try to suppress it, from time to time you feel like you are on the verge of breaking.

4. Disorganized attachment

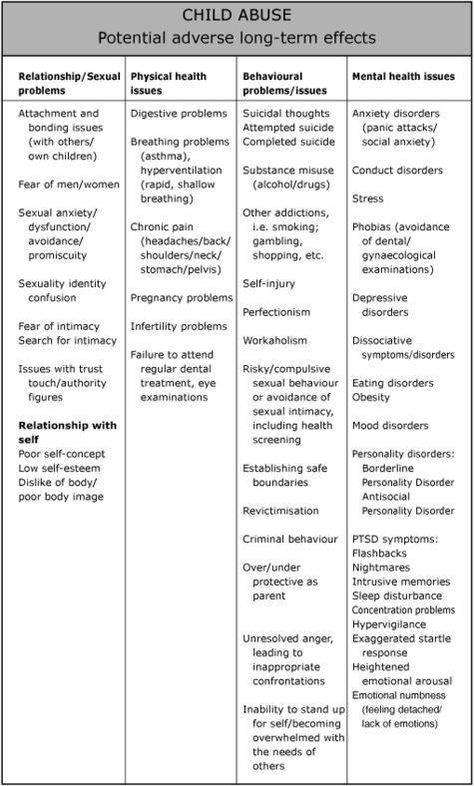

Children who have developed this style have been exposed to prolonged abuse and/or neglect. In a situation involving abuse, these primary caregivers are also a source of hurt; this creates enormous inner conflicts in the child, causing them to have to use mechanisms like splitting and dissociation to cope. If your attachment style is disorganized, you may relate to others in a chaotic, unpredictable way, or even perpetuate a vicious abusive cycle.

If your attachment style is disorganized, you may relate to others in a chaotic, unpredictable way, or even perpetuate a vicious abusive cycle.

You may also have symptoms along the "traumatic-dissociative" dimension (TDD) (Farina, Liotti, and Imperatori 2019). For example, you may experience a "loss of continuity" with your experience, unexplained memory loss, or randomly "losing time." You may experience depersonalization—feeling disconnected with your own body—or derealisation, a sudden sense of disconnection with the world, like you are "floating above it."

Healing is Possible

Your coping styles are not inherently "bad" or wrong. If your parents were not to be trusted, withdrawal and hyper-vigilance might have been absolutely necessary for you. But it could gradually become a liability if the same approach is brought over to your adult relationships, even when there is a genuine loving presence around. This is the mechanism by which a once-necessary, desperate method to survive can become classifiable as a "mental disorder. "

"

To complicate matters, many of us have mixed attachment patterns—so we may swing between various behavioral patterns, from distancing to clinging, controlling, or devaluing the relationship. Or we glorify our partner one day, then devalue them the next day. We swing from attaching intensely to distancing ourselves and armoring up heavily. This split partly explains the confusion we see amongst borderline personality disorder, including quiet borderline personality disorder and high-functioning borderline personality disorder.

We often find ourselves repeating the same behaviors and patterns throughout our lives. Having an awareness of what is underneath your presentation can then help you move towards developing more securely attached relationships, and heal from the painful symptoms of BPD. Combining deep insights with time, you can certainly turn the situation around.

Attachment and BPD, Quiet BPD, High-functioning BPD

Table of Contents

Does your attachment experience explain your BPD, Quiet BPD or High-Functioning BPD?

In recent years, a lot of publications and resources emerged on the topic of attachment theories, and the relationship between BPD and attachment. You may already be familiar with these concepts. On this page, we will review some of the basic premises of attachment theories, how they may relate to your push-pull behaviours and explain various BPD symptoms.

You may already be familiar with these concepts. On this page, we will review some of the basic premises of attachment theories, how they may relate to your push-pull behaviours and explain various BPD symptoms.

We cannot paint everyone with Borderline Personality Disorder (BPD) with a single brushstroke. Even people may carry the same diagnostic label, their unique life experiences and innate temperaments will create different coping styles and, therefore, symptom profiles. Combining an understanding of attachment theories with that of varying BPD types will allow us to gain better insights into your struggles and help you on the path towards healing.

“It is as if my life were magically run by two electric currents: joyous positive and despairing negative–which ever is running at the moment dominates my life, floods it.”

― Silvia Plath

Attachment Styles and Adaptation Strategies

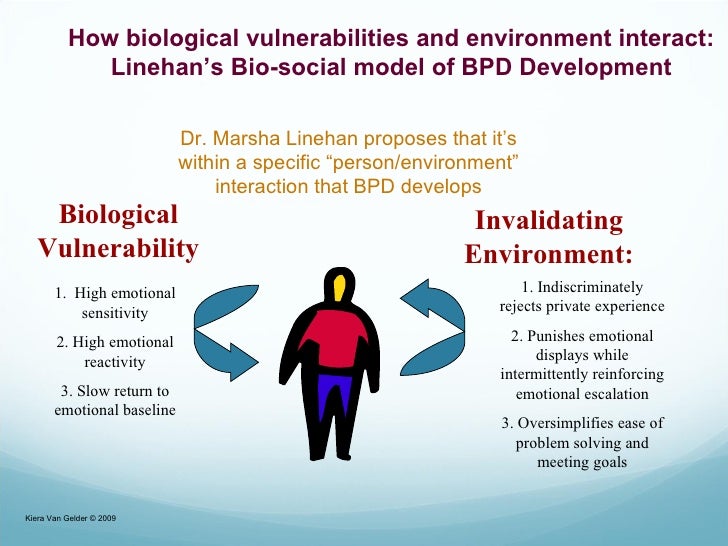

Our parents’ response to our attachment-seeking behaviours, especially during the first few years of our lives, ultimately shape how we see and experience the world. Suppose as infants, we have consistent attachment interactions with someone loving, attuned and nurturing, who can mirror our emotions back to us accurately, and do not ask us to carry their distress. In that case, we will be able to develop a sense of safety and trust. If our parent/ parents were able to respond to our calls for feeding and comfort most of the time, we would internalise the message that the world is a friendly place; we trust that someone will be there for us when we are in need. Eventually, we will also be able to internalise that calming presence as a part of ourselves, and therefore be able to regulate our own emotions even in times of stress. If, in contrast, the message that we were given was that the world was unsafe and that people could not be relied upon, it would affect our ability to withstand uncertainty in life. This means that even in relationships, we struggle with grey areas. Since we feel unable to sit with any ambiguity in communication, we may demand constant reassurance, quickly flip into black-or-white thinking, feel the impulse to end everything or plunge into despair whenever conflict arises.

Suppose as infants, we have consistent attachment interactions with someone loving, attuned and nurturing, who can mirror our emotions back to us accurately, and do not ask us to carry their distress. In that case, we will be able to develop a sense of safety and trust. If our parent/ parents were able to respond to our calls for feeding and comfort most of the time, we would internalise the message that the world is a friendly place; we trust that someone will be there for us when we are in need. Eventually, we will also be able to internalise that calming presence as a part of ourselves, and therefore be able to regulate our own emotions even in times of stress. If, in contrast, the message that we were given was that the world was unsafe and that people could not be relied upon, it would affect our ability to withstand uncertainty in life. This means that even in relationships, we struggle with grey areas. Since we feel unable to sit with any ambiguity in communication, we may demand constant reassurance, quickly flip into black-or-white thinking, feel the impulse to end everything or plunge into despair whenever conflict arises.

To see the link between BPD and attachment, we must first understand attachment theory. Attachment theory was originally developed by John Bowlby (1907 – 1990), who started by observing how infants react to being separated from their parents. Bowlby saw the behavioural attachment system as a biologically based system oriented towards seeking protection and maintaining closeness to the attachment figure, especially in times of threat and danger. The child has to develop patterns of defence and regulation that adapt to the context they were given.

Bowlby’s theory was later put into experiments by Mary Ainsworth (1913 – 1999), who came up with the famous “Strange Situation” experiment. In this investigation series, 12-month-old infants and their parents are brought to the laboratory and separated from and reunited with one another. The researchers identified four distinct patterns of reactions, as detailed below.

“Securely attached’ children become upset when the parent leaves the room, but, when he or she returns, they actively seek the parent and are easily comforted by him or her.

“Anxious- resistant” children (also called ‘anxious- ambivalent’. For simplicity, we may just call them ‘anxious’) are incredibly distressed when separated from their mothers. Importantly, even after they are reunited with their parents, these children have a difficult time being soothed and relating to their parents. They show conflicting behaviours that signal although they want to be comforted, they also want to “punish” the parent for leaving.

“Avoidant’ children do not appear distressed by the separation, and, upon reunion, they avoid contact with their parents. They refuse to look at their parents or hug them, and may just turn their attention to toys and objects on the floor.

‘Disorganised attachment’ was later added as the fourth category. These children seem confused and hesitate to seek that comfort from their parents. They display highly traumatised— freezing or contradictory behaviours both when their parent leaves the room and on their return.

Ainsworth’s work provided the first empirical foundation of individual differences in infant attachment patterns. More importantly, researchers later find that, since adult intimate relationships are attachment relationships, we can see the same kinds of individual differences and patterns as we would have observed in our infant-caregiver relationships.

Psychologists found that without conscious intervention, we tend to stick with our childhood attachment styles. If we have an anxious attachment pattern, we might become attached and clingy; if we have an avoidant attachment pattern, we tend to cut off to protect ourselves, trust ourselves instead of the world. This is the pathway via which BPD and attachment patterns are correlated.

“And what if—what are you if the people who are supposed to love you can leave you like you’re nothing?”

― Elizabeth Scott , The Unwritten Rule

Attachment Styles, Adult Relationships and Borderline Personality Disorder

Contemporary attachment researchers have roughly categorised adult attachment patterns through where they fall on two dimensions: Anxiety and Avoidance (Brennan, Clark, & Shaver,1998). Research on these patterns give validity to the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), and the results from these interviews are reviewed as follow:

Research on these patterns give validity to the Adult Attachment Interview (AAI), and the results from these interviews are reviewed as follow:

Individuals who are low on both anxiety and avoidance dimensions are said to be securely attached. They have positive views for themselves and others and believe that they are worthy of care and that others can be counted on to provide support when needed.

They usually grew up in a supportive environment where parents were responsive to their needs. People who are securely attached are generally comfortable with being vulnerable, they are open and warm in a social situation. When needed, they are okay with asking for help and letting others support them. They are usually confident and have a positive outlook on life, are comfortable with closeness, and seek physical and/or emotional intimacy with little fear of abandonment.

Securely attached individuals are consistent and reliable in their behaviours toward their partner.

People who are high on the anxiety dimension are more likely to have a negative view of themselves, resulting from internalising their attachment figure’s unavailability and interpreting it as rejection. If you have this attachment style, conscious or not, your upbringing has caused you to believe you were unworthy of love and care. You crave intimacy and approval, yet fear rejection and abandonment.

Sometimes referred to as “insecure-ambivalent,” you have developed this form of attachment likely because your parents have been inconsistent with their emotional availability and responses to you. Maybe at times, they are nurturing, caring, and attentive. Other times, or as their mood changes, they flip to being cold, rejecting, detached or even cruel. You never know what to expect. This results in a hyper-vigilant psyche— at every moment you feel like you have to watch out for any signs of change in the relationship dynamics. You have internalised the message, albeit unconsciously, that you can only be loved if you pay very, very close attention to the person who can potentially give you love and attention.

You have internalised the message, albeit unconsciously, that you can only be loved if you pay very, very close attention to the person who can potentially give you love and attention.

As an anxious child, you sought constant assurance, approval and attention from others, and as adults, you may demand these from your partners. You have a highly intense need for contact and connection and come across as dependent or clingy. You struggle with the idea of object constancy and experience constant fear of abandonment. You are highly aware of the smallest hint that others may be angry, upset or pulling back from you. When you feel insecure, you cannot help but react with fear, anger, and a desperate search for contact, validation and connection.

You tend to struggle more with maladaptive dependency (as opposed to counter-dependency). You may have more pleasing behaviours, sacrifice your own needs for that of others, and find it difficult to trust your ability to endure or enjoy solitude.

You may relate more to the descriptions of ‘classic’ BPD, where the fear of abandonment and instability in interpersonal relationships are core features. You quickly drop into despair or become enraged even with the slightest change in social nuances. This fear of being left alone, and therefore, annihilated, is at the heart of the BPD trauma.

If your efforts to seek contact have been repeatedly shamed and traumatising, you might also have decided to stop seeking out attachment, keep to yourself, but you continue to feel a deep longing, emotional loneliness and shame that come from your attachment trauma. In this case, you may identify more with the description of Quiet BPD.

“What loneliness is more lonely than distrust?”

– George Elliot

Individuals high on the avoidance dimension, on the other hand, have developed negative views of others. Through your experience, you learned that people could not be counted on, and you have to rely excessively, if not solely, on yourself.

You may think of and describe your childhood vaguely and inconsistently, and tend to minimise or downplay painful feelings. You may not remember much of your childhood and feel uncomfortable speaking about it. Normalising, intellectualising and rationalising painful events are your core coping mechanisms.

Also referred to as “insecure-avoidant,” children usually develop this attachment style when their primary caregivers are not responsive to or reject their needs. You learned to pull away emotionally as a way to avoid feelings of rejection. Unlike anxious-preoccupied children, avoidant children are almost excessively independent. If you have adopted this survival strategy, you may continue with this pattern even as adults, and see yourself as being completely self-reliant, hide your real self and avoid close bonds. You may use becoming distant as a coping strategy when conflicts arise.

You eventually become uncomfortable with emotional openness and may even deny your need for intimacy. You place a high value on independence and autonomy and worry about being overwhelmed, engulfed, and controlled. You avoid being emotionally open with others for fear of them coming too close. You may recognise the value of relationships and have a strong desire for you, but have difficulty trusting others.

You place a high value on independence and autonomy and worry about being overwhelmed, engulfed, and controlled. You avoid being emotionally open with others for fear of them coming too close. You may recognise the value of relationships and have a strong desire for you, but have difficulty trusting others.

If you have this attachment style, you may relate more to the Quiet BPD or High-functioning BPD descriptions. In Quiet BPD, you turn your pain inward and hurt yourself rather than lash out at others. In High-functioning BPD, you shield your conscious and unconscious anxieties and relational wound with a facade of normalcy. In both cases, your deepest pain remains buried. Both your yearnings and fears remain unseen — not just to others but even yourself. While you may seem to function ‘normally’ in your day to day life, inside you feel numb, as though you are running on an auto-pilot. The emptiness and loneliness wear on your conscience day after day, and however much you try to suppress it, from time to time you feel like you are on the verge of breaking.

Children who have developed this style have been exposed to prolonged abuse and/or neglect. Primary caregivers are the people children must turn to as a source of comfort and support. In a situation involving abuse, these primary caregivers are also a source of hurt; this creates enormous inner conflicts in the child, causing them to have to use mechanisms like splitting and dissociation to cope. If you have been abused in this way, you may grow up to become someone who fears intimacy within relationships but also fear the loneliness of not having close relationships. If your attachment style is disorganised, you may relate to others in a chaotic, unpredictable way, or even perpetuate a vicious abusive cycle. The symptoms you exhibit is primarily related to Complex PTSD. Complex PTSD is caused by ‘cumulative developmental trauma’ (CDT), also known as early relational trauma (Isobel et al., 2017). It happens when you were trapped in a situation where traumatic events repeatedly happened, cumulatively, over a period of time in which you had no route to escape (Sar, 2011).

Many of the symptoms of Complex PTSD overlap with BPD; With Complex PTSD, You may also have symptoms along the ‘”traumatic-dissociative” dimension (TDD)’ (Farina, Liotti and Imperatori 2019). For example, you may experience a ‘loss of continuity with your experience, unexplained memory loss, or randomly ‘losing time’. You may have depersonalisation— feeling disconnected with your own body, or derealisation— a sudden sense of disconnection with the world, like you are ‘floating above’ it. You may also experience identity confusion, and even occasionally lose control of your body.

*

I must be careful not to be trapped in the past. That is when I forget my songs.

- Mick Jagger

All children have no choice but to lean on their caregivers to survive. When there has been emotional trauma, instability in attachment relationships, neglect or abuse, you had to come up with ways to adapt to the situation. Therefore, your survival strategies are not inherently ‘bad’, or pathological. It is only when they are rigidly held and no longer fit the new contexts and relationships in adulthood, that they become ‘maladaptive’ and ‘disordered’. For instance, if your parents were inconsistent, violent and not to be trusted, withdrawal and hyper-vigilance might be absolutely necessary for you. But it could gradually become a liability if the same approach is used in your adult relationships, even when there is a genuine loving presence around. This is the mechanism by which a once-necessary, desperate method to survive becomes a ‘mental disorder’.

It is only when they are rigidly held and no longer fit the new contexts and relationships in adulthood, that they become ‘maladaptive’ and ‘disordered’. For instance, if your parents were inconsistent, violent and not to be trusted, withdrawal and hyper-vigilance might be absolutely necessary for you. But it could gradually become a liability if the same approach is used in your adult relationships, even when there is a genuine loving presence around. This is the mechanism by which a once-necessary, desperate method to survive becomes a ‘mental disorder’.

To complicate matters, many of us have mixed attachment patterns— so we may swing between various behavioural patterns, from distancing to clinging, controlling, or devaluing the relationship. Or, we glorify our partner one day to devalue them the next day. We swing from attaching intensely to distancing ourselves and armouring up heavily. This split partly explains the confusing relating pattern we see in those with BPD, Quiet BPD, High-functioning BPD, and Complex PTSD.

It is also not always easy to gauge someone else’s attachment style. For example, it is extremely common for people to be avoidant in their behaviour manifestations but struggles with anxious attachment on the inside. Because they cannot handle the fear of abandonment and rejection, they may withdraw or end the relationship prematurely to protect themselves. Someone may have behaviours such as stop texting, set up a wall, remain silent, or withdraw into their own world, and appear to be ‘avoidant’, but inside, they are hurting from a premature assumption that they have been left by the other person.

BPD and attachment are linked. Neural pathways developed from childhood traumatic experiences help shape how we respond to others, and we often find ourselves repeating the same behaviours and patterns throughout our lives. This is not meant to place all blame on parents for the types of relationships you have as adults or to suggest that all is therefore hopeless. Although parents play an essential role in setting that foundation, we as an adult have the ability to create changes for ourselves and our behaviours.

By developing a better understanding of how our early childhood experiences have shaped our attachment style and its connection to our present style of interactions, we can improve our relationships. This awareness can then help us move towards developing more securely attached relationships, and heal from the painful symptoms of Borderline personality disorder. Combining deep insights with time, you can certainly turn the situation around.

Attachment relationships in borderline personality disorder, Psychology - Gestalt Club

Attachment theory was developed by J. Bowlby, and for the first the plan in it puts forward the need of a person in the formation of loved ones emotional relationships that are manifested in intimacy and distances in contact with the caregiver. Relationship creation security is the goal of an attachment system that works as a regulator of emotional experience. From the mother's side affection is expressed in caring for the child, attention to signals, which he submits, communicating with him as a social being, not limited to the satisfaction of physiological needs. nine0003 A key aspect of borderline personality disorder is known to be (BPD) - difficulties in interpersonal relationships, accompanied by negative affectivity and impulsivity. In the experiments carried out by M. Ainsworth, three main types were distinguished attachments: secure and two insecure attachments - avoidant and ambivalent. Another type of attachment was later described - disorganized. With this type of attachment, the world is perceived child as hostile and threatening, and the child's behavior unpredictable and chaotic. Formation of a disorganized attachment occurs in cases where the object of attachment in the process of caring for a child allows for significant and gross disruption of this process, as well as being unable to recognize and feel the needs of the child. nine0004

nine0003 A key aspect of borderline personality disorder is known to be (BPD) - difficulties in interpersonal relationships, accompanied by negative affectivity and impulsivity. In the experiments carried out by M. Ainsworth, three main types were distinguished attachments: secure and two insecure attachments - avoidant and ambivalent. Another type of attachment was later described - disorganized. With this type of attachment, the world is perceived child as hostile and threatening, and the child's behavior unpredictable and chaotic. Formation of a disorganized attachment occurs in cases where the object of attachment in the process of caring for a child allows for significant and gross disruption of this process, as well as being unable to recognize and feel the needs of the child. nine0004

Due to the fact that disorganized attachment is formed in conditions of neglect of the needs of the child and gross violations of care him, then such a system of attachment is not able to fulfill its main function: regulation of the state, including excitation, which is caused by fear. At the same time, often the emergence of fear in child contributes to the reaction and behavior of the parents themselves. Child is caught in the trap of paradoxical demands: the behavior of the parent provokes fear in the child, while the logic of the system attachment pushes the child to seek solace and relaxation affective state in this particular figure. Parents of children with a disorganized type of attachment are characterized high levels of aggression, as well as suffer from personal and dissociative disorders. nine0003 However, a disorganized type of attachment can also form in the absence of care disorders: to the formation of this type attachment can also lead to overprotection, combining mutually exclusive strategies for caring for a child with a disability parents to regulate the excitement of the child, which is caused fear. In addition, the formation of a disorganized attachment can occur in conditions of mismatch affective alerts simultaneously presented by the mother in her communication to the child.

At the same time, often the emergence of fear in child contributes to the reaction and behavior of the parents themselves. Child is caught in the trap of paradoxical demands: the behavior of the parent provokes fear in the child, while the logic of the system attachment pushes the child to seek solace and relaxation affective state in this particular figure. Parents of children with a disorganized type of attachment are characterized high levels of aggression, as well as suffer from personal and dissociative disorders. nine0003 However, a disorganized type of attachment can also form in the absence of care disorders: to the formation of this type attachment can also lead to overprotection, combining mutually exclusive strategies for caring for a child with a disability parents to regulate the excitement of the child, which is caused fear. In addition, the formation of a disorganized attachment can occur in conditions of mismatch affective alerts simultaneously presented by the mother in her communication to the child. So when the child is in a state obvious distress, the mother can simultaneously cheer up the child and make fun of him. In response to this mixed stimulation becomes disorganized behavior of the child. It is noted that in some cases mothers of children, with a disorganized type attachments, playing with their children, showed an inability to passing meta-alerts that tell the child about the conditionality games. So, playing with a child, mothers realistically depicted a predatory beast, showed menacing teeth, growled angrily and howled ominously, chasing the child on all fours. Their behavior was so it is realistic that a child who does not receive meta-alerts from them, which would confirm the conditionality of the situation, experienced horror, as if being alone with the real terrible pursuing them beast. nine0003 According to attachment theory, the development of the self occurs in context of affect regulation in early relationships. Thus, disorganized attachment system leads to disorganized system of the self.

So when the child is in a state obvious distress, the mother can simultaneously cheer up the child and make fun of him. In response to this mixed stimulation becomes disorganized behavior of the child. It is noted that in some cases mothers of children, with a disorganized type attachments, playing with their children, showed an inability to passing meta-alerts that tell the child about the conditionality games. So, playing with a child, mothers realistically depicted a predatory beast, showed menacing teeth, growled angrily and howled ominously, chasing the child on all fours. Their behavior was so it is realistic that a child who does not receive meta-alerts from them, which would confirm the conditionality of the situation, experienced horror, as if being alone with the real terrible pursuing them beast. nine0003 According to attachment theory, the development of the self occurs in context of affect regulation in early relationships. Thus, disorganized attachment system leads to disorganized system of the self. Children are designed in such a way that expect their internal states to be one way or another mirrored by other people. If the baby does not receive access to an adult who is able to recognize his inner states and react to them, it will be very difficult for him to understand own experiences. In order for the child to normal experience of self-awareness its emotional cues must be carefully mirrored by the figure of affection. mirroring should be exaggerated (i.e. slightly distorted) in order to the infant understood the expression of feeling on the part of the attachment figure as part of one's own emotional experience, not as an expression emotional experience of the attachment figure. When a child cannot develop a representation of one's own experience through mirroring, it assigns the image of the attachment figure as part of self-representation. If the reactions of the attachment figure are inaccurate reflect the experiences of the child, he has no choice but to use these inadequate reflections to organize your internal states.

Children are designed in such a way that expect their internal states to be one way or another mirrored by other people. If the baby does not receive access to an adult who is able to recognize his inner states and react to them, it will be very difficult for him to understand own experiences. In order for the child to normal experience of self-awareness its emotional cues must be carefully mirrored by the figure of affection. mirroring should be exaggerated (i.e. slightly distorted) in order to the infant understood the expression of feeling on the part of the attachment figure as part of one's own emotional experience, not as an expression emotional experience of the attachment figure. When a child cannot develop a representation of one's own experience through mirroring, it assigns the image of the attachment figure as part of self-representation. If the reactions of the attachment figure are inaccurate reflect the experiences of the child, he has no choice but to use these inadequate reflections to organize your internal states. Since inaccurate reflections are bad superimposed on his experiences, the child's self acquires potential for disorganization, i.e. lack of unity and fragmentation. Such a break with the self is called "alien self” to which subjective experiences can correspond feelings and ideas that are considered their own, but are not felt in as such. nine0004

Since inaccurate reflections are bad superimposed on his experiences, the child's self acquires potential for disorganization, i.e. lack of unity and fragmentation. Such a break with the self is called "alien self” to which subjective experiences can correspond feelings and ideas that are considered their own, but are not felt in as such. nine0004

Behavior of mothers that causes horror in the child, and even shock is not necessarily dictated by their desire to truly scare child and terrify him, this behavior of mothers is due because they do not have the ability to understand how their actions are reflected in the child's psyche. It is assumed that such behavior and reactions of mothers are associated with their own unprocessed traumatization, such Thus, in communication with the child, some not integrated aspects of maternal traumatic experience. So way the parent's behavior is so hostile and unpredictable for the child, which does not allow him to develop any certain interaction strategy. In this case, do not look for closeness, nor does it help to avoid it, since the mother is from a person, which should provide protection and security, itself becomes a source of anxiety and danger. Images of both myself and mother in this the case is very hostile and cruel. nine0004

In this case, do not look for closeness, nor does it help to avoid it, since the mother is from a person, which should provide protection and security, itself becomes a source of anxiety and danger. Images of both myself and mother in this the case is very hostile and cruel. nine0004

One of the tasks of the self-protection system or the self-preservation system is in compensation for the inability of disorganized attachment form and maintain the stability of the psyche, which becomes possible thanks to a sense of security and care from attachment object. E. Bateman and P. Fonagi pointed to disorganized attachment as the most significant factor, affecting the violation of the formation of the ability to mentalization. The authors define mentalization as a key socio-cognitive ability that enables people to create effective social groups. Attachment and mentalization are systems connected to each other. Mentalization begins in the feeling that the attachment figure understands you. Ability to mentalization makes an important contribution to affective regulation, control impulses, self-monitoring and a sense of personal initiative The cessation of mentalization most often occurs in response to attachment trauma. nine0004

nine0004

Lack of mentalization is characterized by: * An excess details in the absence of motivation of feelings or thoughts *Emphasis on external social factors *emphasis on labels *preoccupation rules *denial of involvement in the problem *accusations and nagging *Confidence about other people's feelings/thoughts Good mentalization is inherent in: - in relation to thoughts and feelings other people * opacity - recognition that a person is not knows what is going on in the head of another, but at the same time has some idea of what others think *lack paranoia * taking a point of view - accepting that things can look very different, from different points of view *sincere interest in the thoughts and feelings of others * willingness to discover - lack of desire for unfounded assumptions about what one thinks and feel other people * ability to forgive * predictability - feeling that, in general, other people's reactions are predictable in the presence of knowledge of what they think or feel - perception own mental functioning *variability- understanding that the opinions and understanding of other people can change in accordance with how he himself changes *perspective development - the understanding that as one develops, one's views of others people deepen * realistic skepticism - an acknowledgment that that feelings can be confusing * confession pre-conscious function - the recognition that a person can not fully aware of your feelings * conflict - awareness the presence of ideas and feelings incompatible with each other * installation on introspection * interest in difference * awareness of the influence of affect - self-representation *developed pedagogical skills and abilities hearings *autobiographical unity *rich inner life - shared values and attitudes *caution *moderation

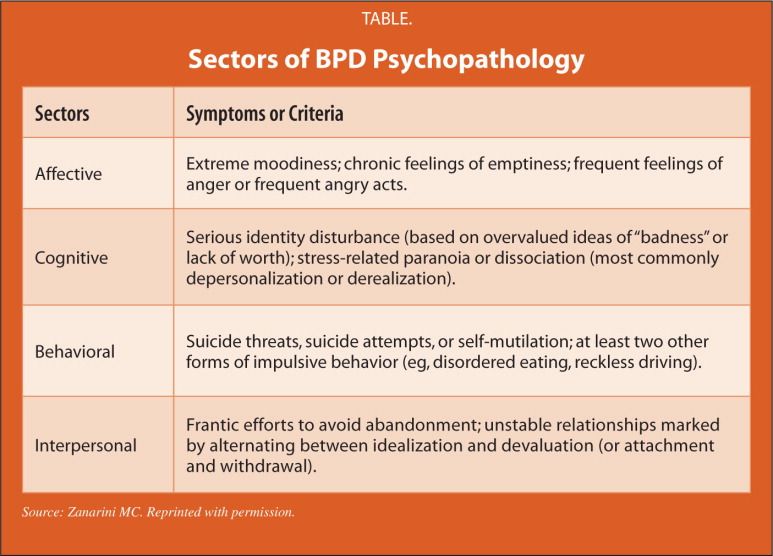

The concept of attachment and mentalization is built on model of development of BPD. The key components of this model are: 1) early disorganization of primary attachment relationships; 2) the ensuing weakening of the main socio-cognitive abilities, further weakening of the ability to establish a strong relationship with an attachment figure; 3) disorganization self structures due to disorganized relationships attachment and mistreatment; 4) exposure to temporary violations of mentalization during the intensification of attachment and excited. Violation of mentalization causes a return prementalist modes of representing subjective states, and they, in turn, in combination with mentalization disorders cause the common symptoms of BPD. nine0004

The key components of this model are: 1) early disorganization of primary attachment relationships; 2) the ensuing weakening of the main socio-cognitive abilities, further weakening of the ability to establish a strong relationship with an attachment figure; 3) disorganization self structures due to disorganized relationships attachment and mistreatment; 4) exposure to temporary violations of mentalization during the intensification of attachment and excited. Violation of mentalization causes a return prementalist modes of representing subjective states, and they, in turn, in combination with mentalization disorders cause the common symptoms of BPD. nine0004

E. Bateman and P. Fonagy described three modes of mental functionings that precede mentalization: teleological mode; mode of mental equivalence; mode pretense. Teleological mode - the most primitive a mode of subjectivity in which changes in mental state are considered real when they are confirmed physical actions. This mode has priority physical. For example, self-damaging acts with teleological point of view make sense because force other people to take actions that prove care. Suicide attempts are often made when a person is in modes of mental equivalence or pretense. With mental equivalence (in which internally equivalent to external) suicide is aimed at destroying alien part of yourself, which is perceived as a source of evil, in In this case, suicidality is on a par with other types self-harm, such as cuts. Suicide can be characterized by existence in the mode of pretense (absence connections between internal and external reality), when the sphere subjective experience and perception of external reality are completely separated, allowing a person with BPD believes that he himself will survive, while the alien part will destroyed forever. In non-mentalized modes of mental body part equivalences can be considered as equivalents specific mental states. Trigger for such acts is the potential loss or isolation, i.e. situations when a person loses the ability to control his internal states.

For example, self-damaging acts with teleological point of view make sense because force other people to take actions that prove care. Suicide attempts are often made when a person is in modes of mental equivalence or pretense. With mental equivalence (in which internally equivalent to external) suicide is aimed at destroying alien part of yourself, which is perceived as a source of evil, in In this case, suicidality is on a par with other types self-harm, such as cuts. Suicide can be characterized by existence in the mode of pretense (absence connections between internal and external reality), when the sphere subjective experience and perception of external reality are completely separated, allowing a person with BPD believes that he himself will survive, while the alien part will destroyed forever. In non-mentalized modes of mental body part equivalences can be considered as equivalents specific mental states. Trigger for such acts is the potential loss or isolation, i.e. situations when a person loses the ability to control his internal states. Pseudo-mentalization is associated with the pretense regime. This mode of perceiving one's own inner world in age 2-3 years is characterized by a limited ability to representations. The child is able to think about the representation until as long as no connection is made between it and the external reality. An adult engaged in pseudo-mentalization is capable of understand and even reason about mental states as long as they are not connected to reality. nine0004

Pseudo-mentalization is associated with the pretense regime. This mode of perceiving one's own inner world in age 2-3 years is characterized by a limited ability to representations. The child is able to think about the representation until as long as no connection is made between it and the external reality. An adult engaged in pseudo-mentalization is capable of understand and even reason about mental states as long as they are not connected to reality. nine0004

Pseudo-mentalization falls into three categories: obsessive, hyperactive inaccurate and destructively inaccurate. intrusive pseudo-metalization manifests itself in violation of the principle of opacity inner peace, expanding knowledge of feelings and thoughts beyond specific context, representation of thoughts and feelings in peremptory manner, etc. Hyperactive pseudo-mentalization characterized by too much energy that is invested in thinking about what the other person is feeling or thinking is idealization of insight for the sake of insight. Specific understanding - the most common category of bad mentalization, which associated with the mode of mental equivalence. This mode is also characteristic of children 2-3 years old, when internally equated to external, the fear of ghosts in a child gives rise to an equally real the experience you would expect from a real ghost. General indicators of concrete understanding are the lack of attention to thoughts other people's feelings and needs, overgeneralization and prejudices, circular explanations, specific interpretations extend beyond the boundaries within which they originally were used. nine0004

Specific understanding - the most common category of bad mentalization, which associated with the mode of mental equivalence. This mode is also characteristic of children 2-3 years old, when internally equated to external, the fear of ghosts in a child gives rise to an equally real the experience you would expect from a real ghost. General indicators of concrete understanding are the lack of attention to thoughts other people's feelings and needs, overgeneralization and prejudices, circular explanations, specific interpretations extend beyond the boundaries within which they originally were used. nine0004

Later trauma is known to be even greater impairs attention control mechanisms and is associated with chronic braking control disorders. Thus, it is formed vicious circle of interaction of disorganized attachment, disorders of mentalization and mental trauma, which contributes to exacerbation of BPD symptoms. Bateman, Fonagi identified two types relationship patterns that often come to light in BPD. One of them - centralized, the other - distributed. Persons who demonstrate a centralized relationship pattern, describe unstable and inflexible interactions. Representation of internal states of another person is closely related to the representation of oneself. Relationships are filled with intense, changing and exciting emotions. The other person is often perceived as unreliable and inconsistent, unable to "to love properly." Often there are fears about the infidelity of a partner and abandonment. Individuals with a centralized pattern are characterized by disorganized, restless attachment in which the object of affection is perceived simultaneously as safe place and source of threat. The distributed pattern is characterized by detachment and distance. With this pattern of relationships, in contrast to the instability of the centralized pattern, maintains a rigid distinction between one's own and another's. nine0003 References:

One of them - centralized, the other - distributed. Persons who demonstrate a centralized relationship pattern, describe unstable and inflexible interactions. Representation of internal states of another person is closely related to the representation of oneself. Relationships are filled with intense, changing and exciting emotions. The other person is often perceived as unreliable and inconsistent, unable to "to love properly." Often there are fears about the infidelity of a partner and abandonment. Individuals with a centralized pattern are characterized by disorganized, restless attachment in which the object of affection is perceived simultaneously as safe place and source of threat. The distributed pattern is characterized by detachment and distance. With this pattern of relationships, in contrast to the instability of the centralized pattern, maintains a rigid distinction between one's own and another's. nine0003 References:

Bateman, Antony W., Fonagy, Peter. Psychotherapy for Borderline Personality Disorder. MentalizationBased Treatment, 2003.

MentalizationBased Treatment, 2003.

Howell, Elizabeth F. Dissociative Mind, 2005 Main Mary, Solomon Judith. Discovery of a new, insecure Adisorganized/disoriented attachment pattern, 1996

Bateman W, Fonagy P. Treatment of borderline personality disorder with based on mentalization, 2014

Bowlby, J. Attachment, 2003

Bowlby, J. Making and breaking emotional bonds, 2004

Brish K.H. Attachment Disorder Therapy: From Theory to practice, 2014.

Fonagi P. Common ground and differences between psychoanalysis and attachment theory, 2002

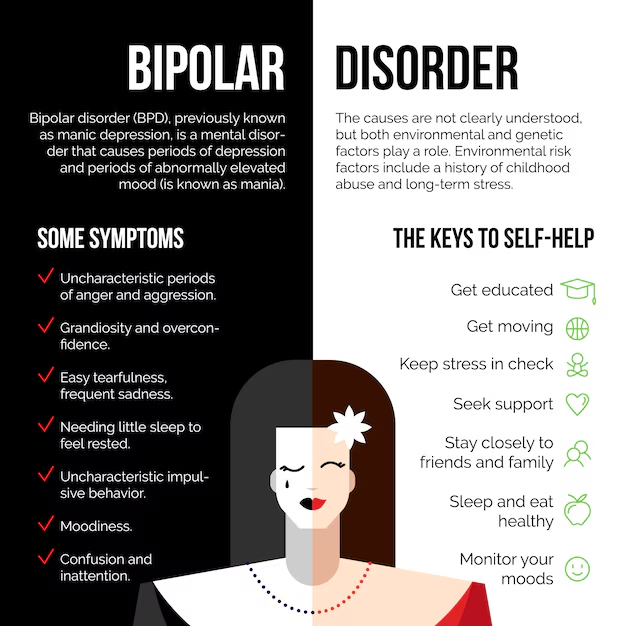

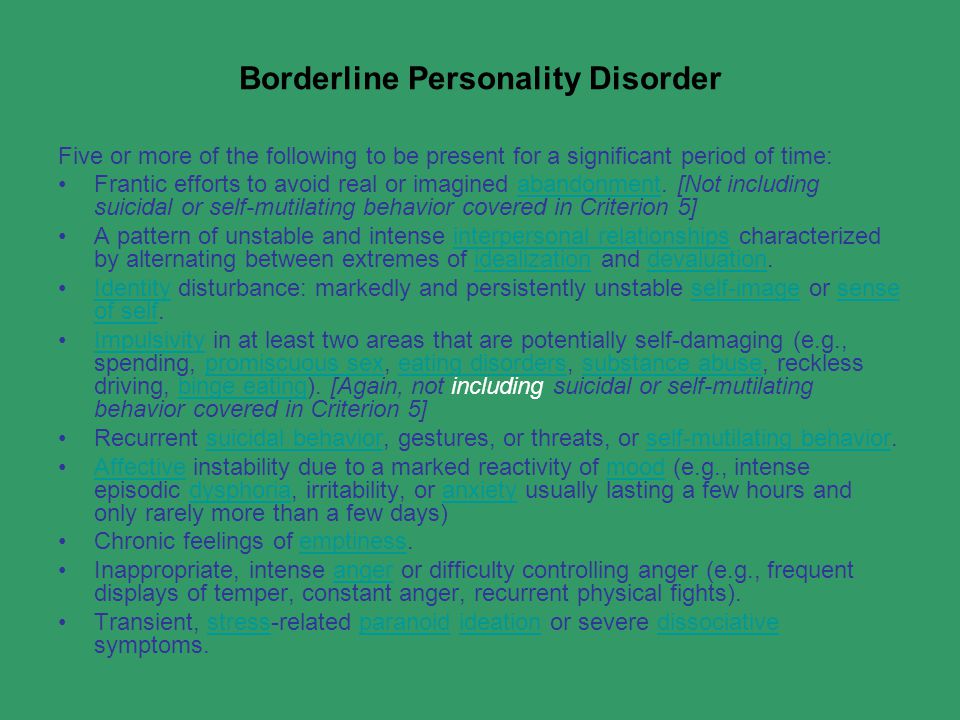

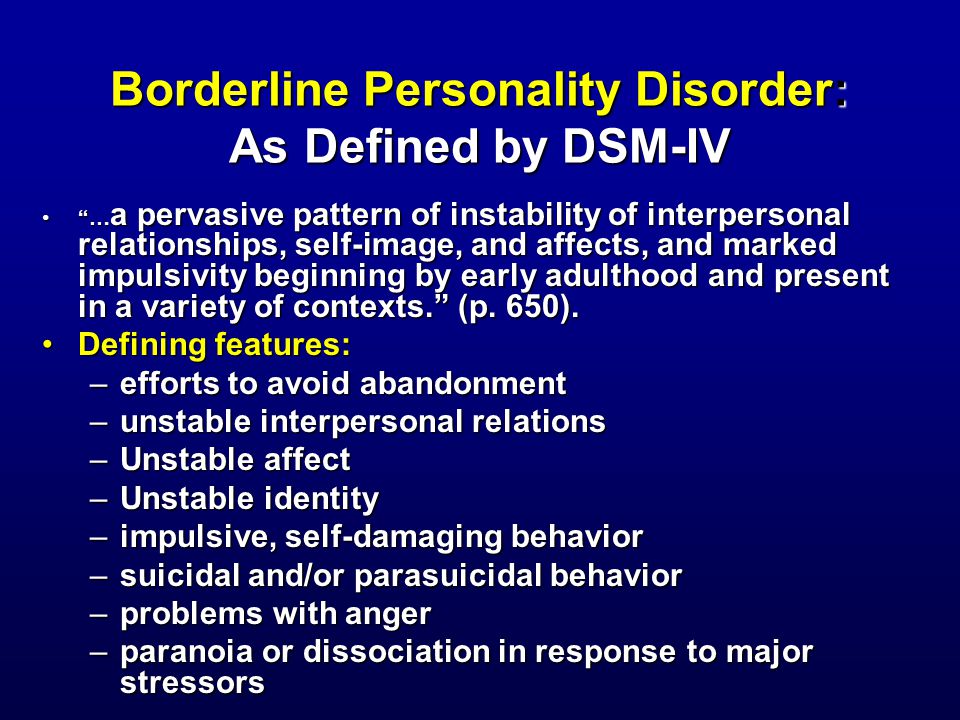

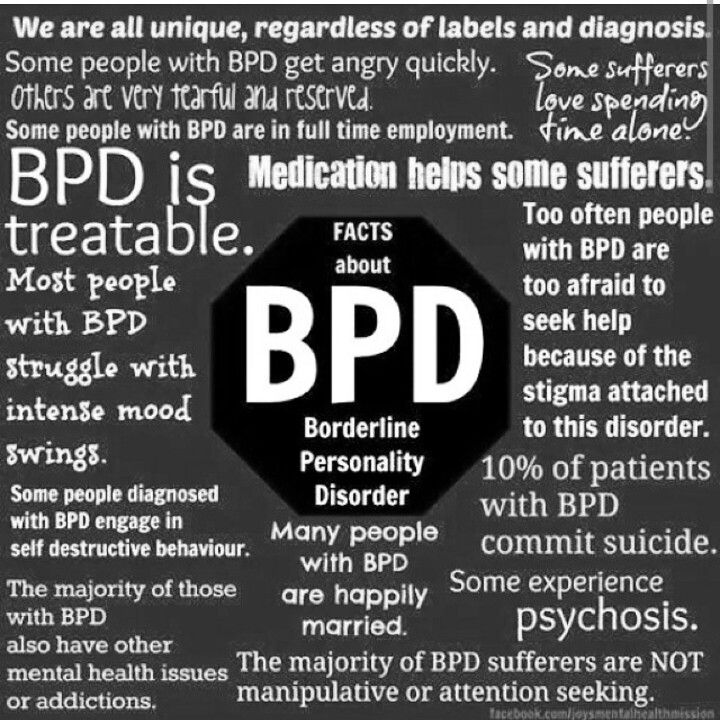

Borderline personality disorder

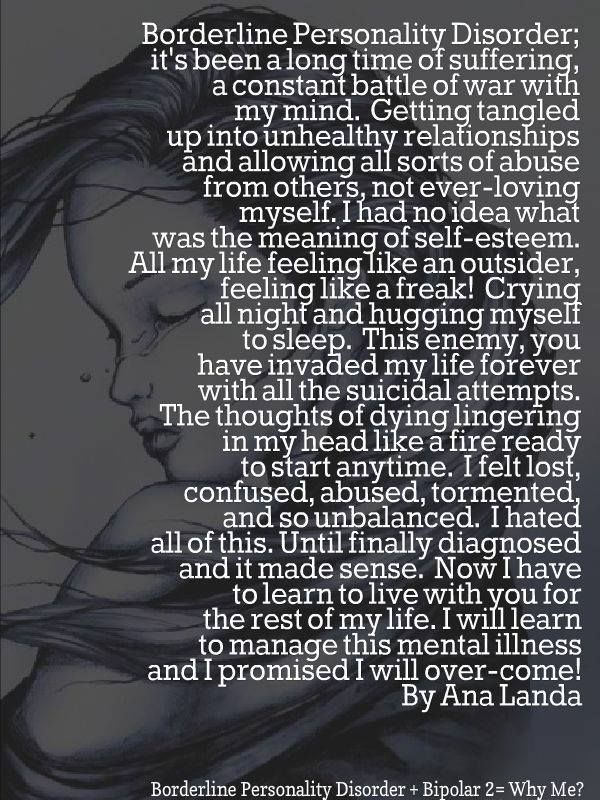

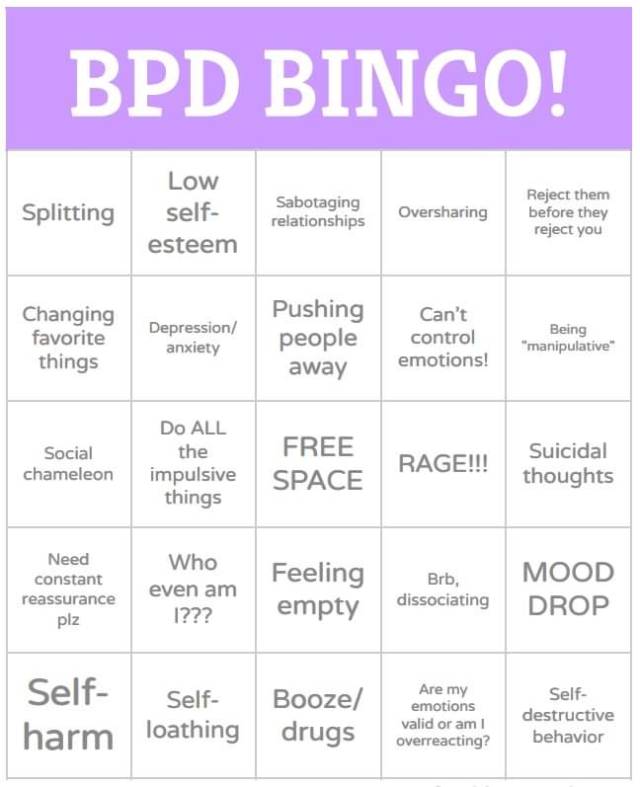

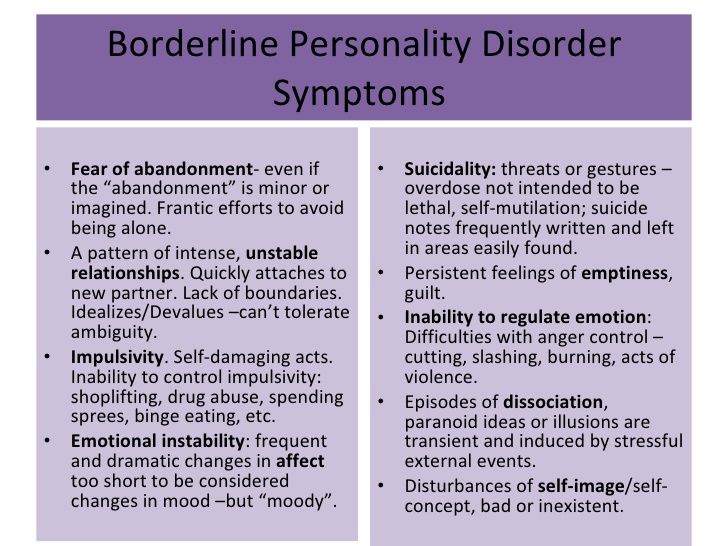

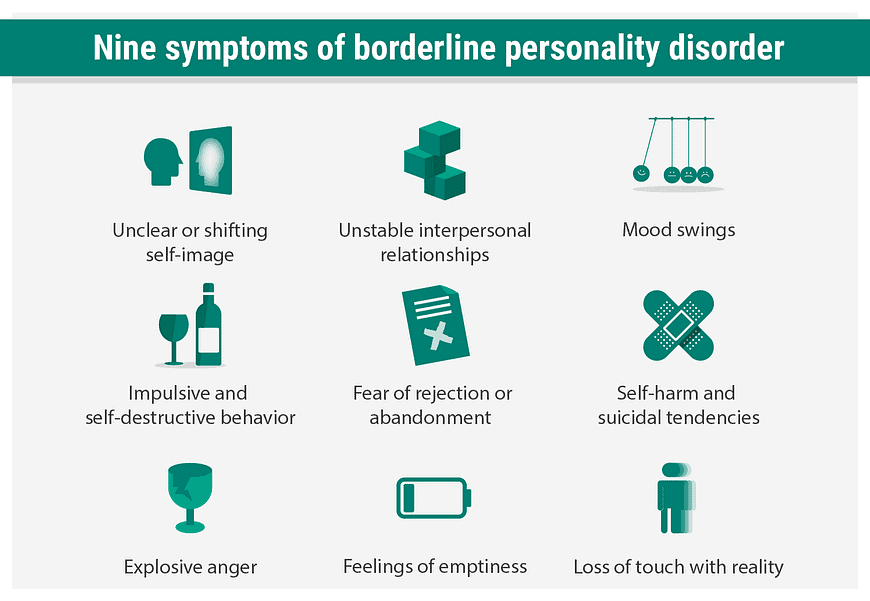

Borderline personality disorder is associated with unstable mood and behavior that has a significant impact on a person's daily life

Borderline personality disorder is a type of personality disorder in which a person experiences periods of tension, unstable moods and behaviors, and an altered "feeling of self."1 everyday life. nine0038 1.2

nine0038 1.2

Borderline personality disorder is a serious illness associated with self-harm and suicidal attempts. One in ten patients complete suicide. 2

Facts About Borderline Personality Disorder

Borderline personality disorder is a type of personality disorder in which a person experiences periods of tension, unstable mood and behavior, and an altered sense of self. nine0038 1

One in ten patients complete suicide. 2

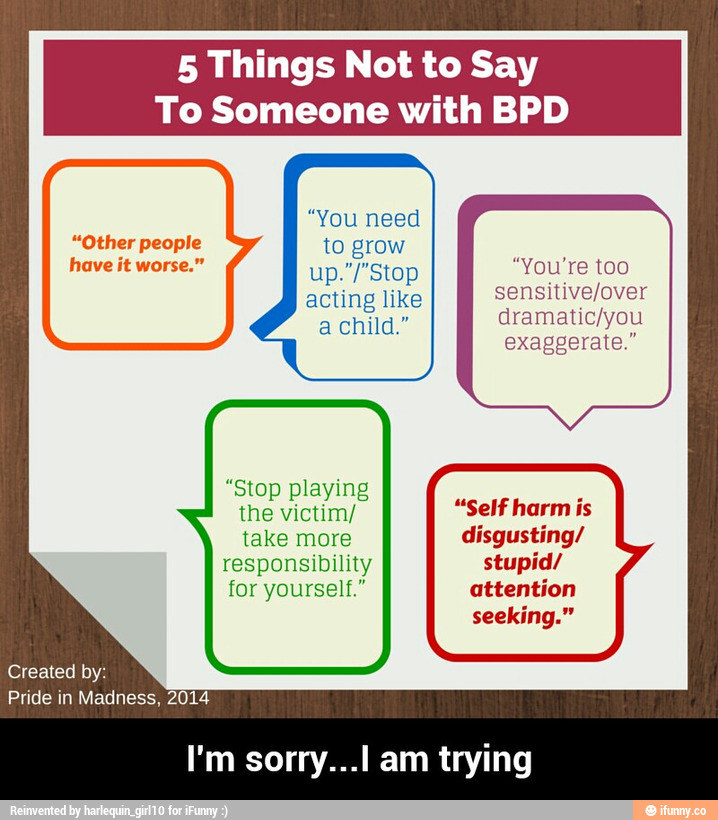

Patients with borderline personality disorder are very sensitive to changes in their environment, and may respond inappropriately and acutely to such changes. They may, for example, be afraid of being abandoned by a loved one.2 If the person whom patient

is expecting arrives late, the patient easily changes the feeling of attachment to dislike or anger. 1,2 This reflects the extreme perception of the world by the patient, who sees everything and everyone - including oneself – either good or bad.1,2

1,2 This reflects the extreme perception of the world by the patient, who sees everything and everyone - including oneself – either good or bad.1,2

People with borderline personality disorder are often insecure, may suddenly change their life goals and views on career, life values and friends. .2 They may develop intense unwarranted anger or feelings of emptiness, and are prone to self-harm.2 Patients with borderline personality disorder may also experience depression and anxiety.1,2

Facts about Borderline Personality Disorder

Estimates of the proportion of people who have borderline personality disorder vary from less than 1% to around 6%. 2-4

Borderline personality disorder affects a roughly equal number of men and women, but appears to be more disabling in women the same frequency in men and women, but in women it is more severe. 3

3

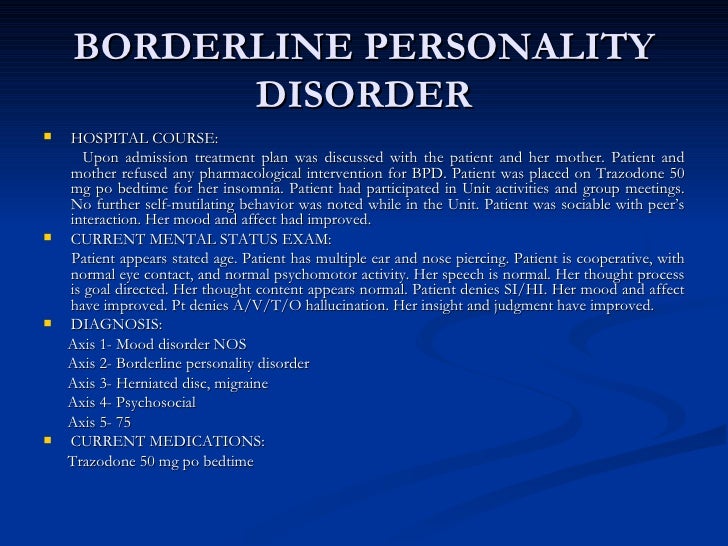

Symptoms of borderline personality disorder most often first appear during adolescence.4 The disease is most severe and problematic in young adults and tends to improve with age.2 Symptoms may persist throughout life, but most patients with borderline personality disorder by the age of 30-40 have a stable job and a home.2

People with borderline personality disorder are emotionally and functionally unstable, which places a significant burden on their families.5 Mood swings are a source of stress for both the patient and his/her others, which can lead to the development of mental disorders in the latter.1,5

People who are concerned that they – or their loved ones – are experiencing symptoms of borderline personality disorder should see their doctor for help and advice.

Borderline personality disorder is diagnosed by a mental health professional using interviews and discussions about symptoms and medical history. 1

1

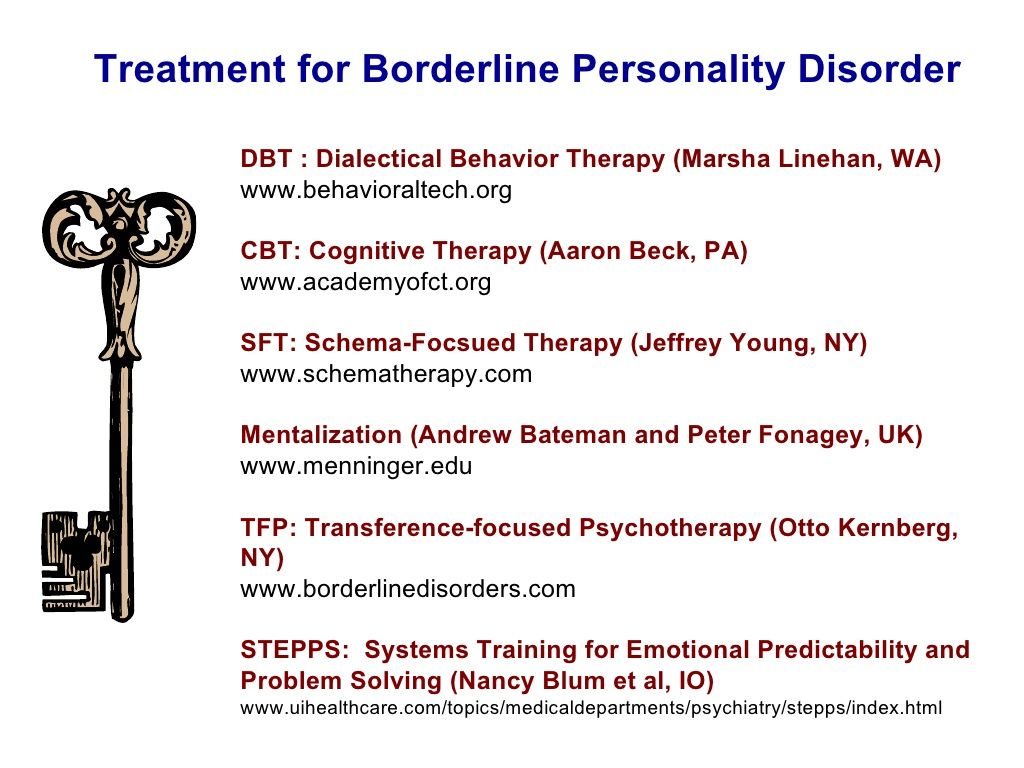

Psychotherapy can help people with borderline personality disorder by, for example, teaching them how to interact with others and to express their thoughts and feelings more clearly. nine0038 1 It may also be beneficial for caregivers and family members of those affected to receive therapy and guidance on how best to care for a person with borderline personality disorder. 1 There is currently no cure, but one study showed that, after 10 years, 50% of people with borderline personality disorder had recovered, being able to function at work and maintain personal relationships. 6

- National Institute of Mental Health. borderline personality disorder. NIH publication number QF 17-4928. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/borderline-personality-disorder/index.shtml [accessed 30 September 2019].

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. - Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533–545.

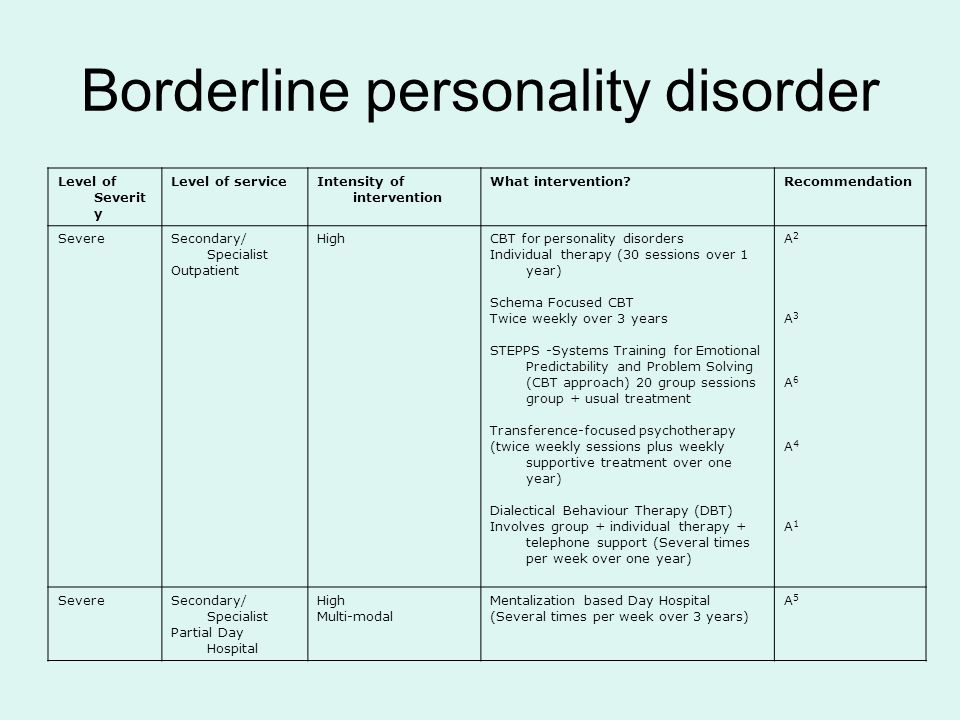

- National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management. 2009. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg78/resources/borderline-personality-disorder-recognition-and-management-pdf-975635141317 [accessed 30 September 2019].

- Bailey RC, Grenyer BFS. Burden and support needs of carers of persons with borderline personality disorder: a systematic review. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2013;21(5):248–258. nine0130

- Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR, Reich DB, Fitzmaurice G. Time to attainment of recovery from borderline personality disorder and stability of recovery: a 10-year prospective follow-up study.

Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):663–667.

Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(6):663–667.

1. National Institute of Mental Health. borderline personality disorder. NIH publication number QF 17-4928. Available from: https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/publications/borderline-personality-disorder/index.shtml [accessed 30 September 2019].

2. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

3. Grant BF, Chou SP, Goldstein RB, Huang B, Stinson FS, Saha TD, et al. Prevalence, correlates, disability, and comorbidity of DSM-IV borderline personality disorder: results from the Wave 2 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(4):533–545.

4. National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Borderline personality disorder: recognition and management. 2009. Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg78/resources/borderline-personality-disorder-recognition-and-management-pdf-975635141317 [accessed 30 September 2019].