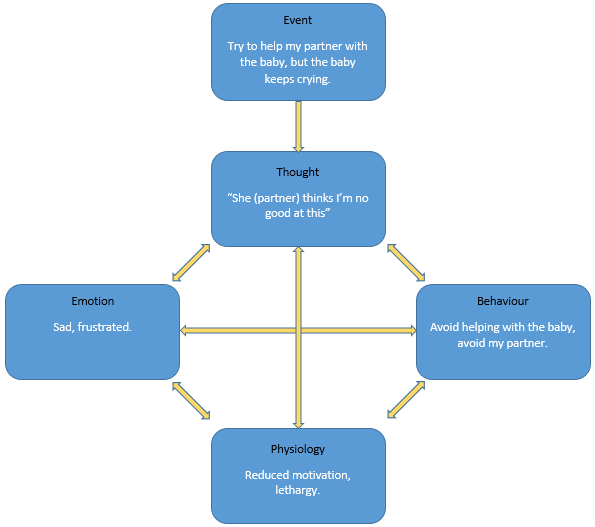

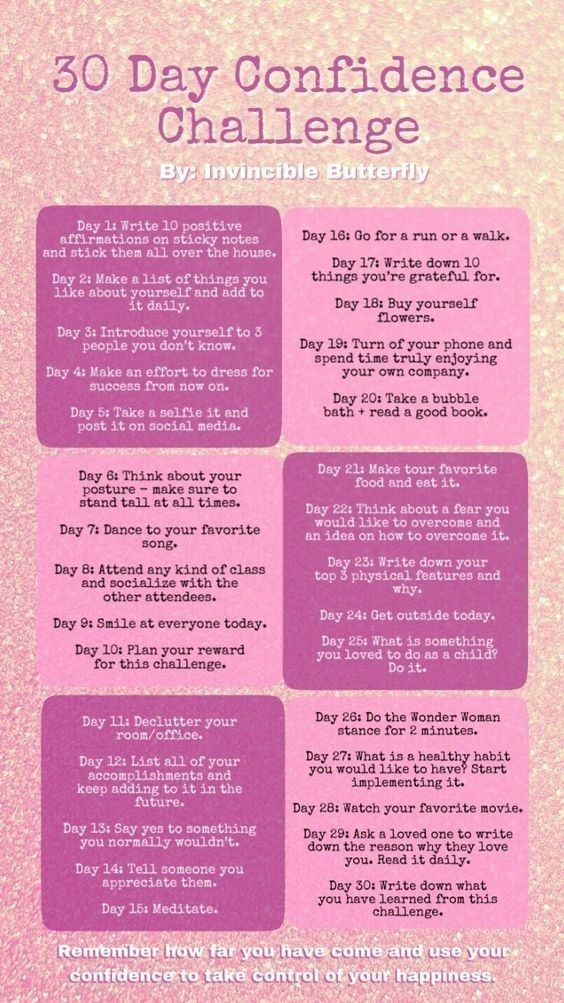

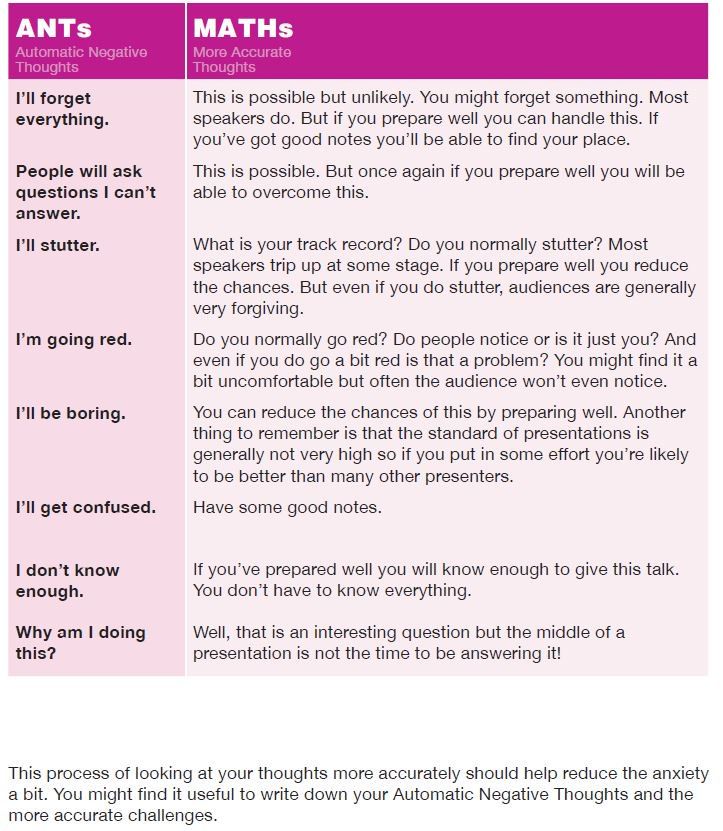

Automatic negative thoughts chart

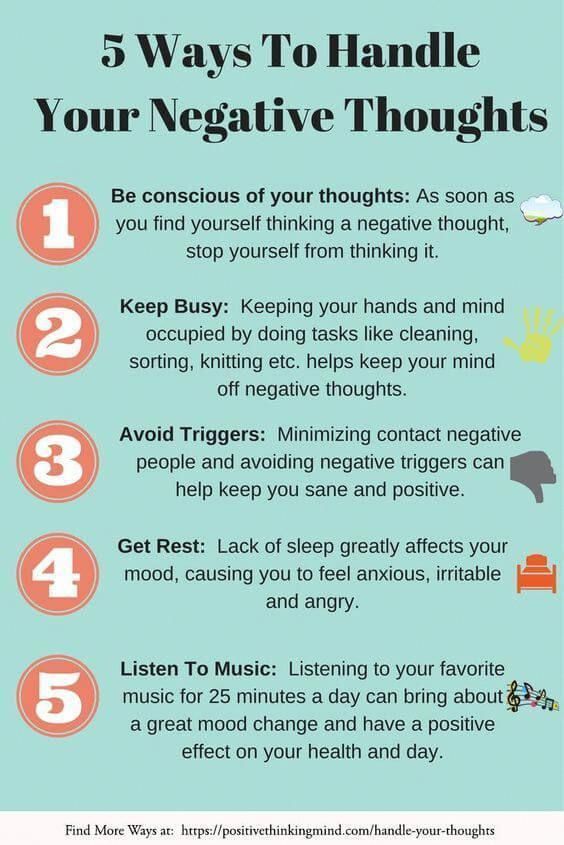

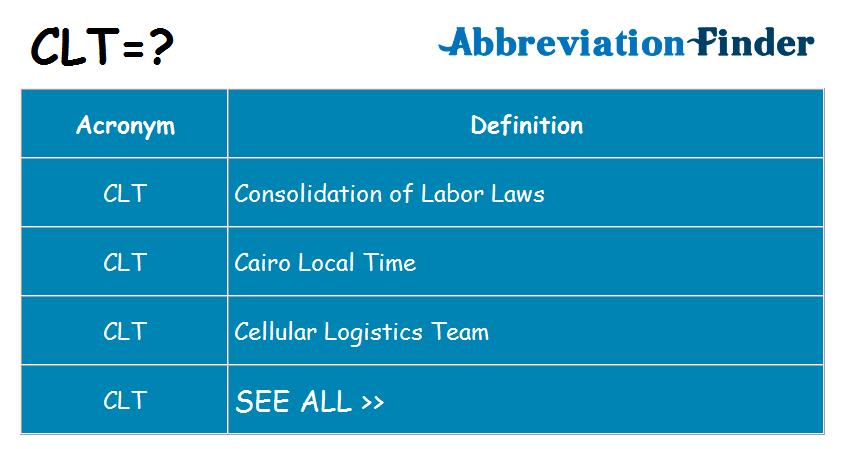

Challenging Negative Automatic Thoughts: 5 Worksheets (+PDF)

Automatic thoughts are images, words, or other kinds of mental activity that pop into your head in response to a trigger.

These thoughts can seem mundane or unimportant, but they can, in fact, be extremely impactful. The types of automatic thoughts a person has can affect their health outcomes as well as their overall quality of life.

This article will cover what automatic thinking is and how it affects people’s lives, what automatic thoughts look like, and how to break the cycle of negativity with positive thoughts.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free. These science-based exercises will not only enhance your ability to understand and work with your emotions but will also give you the tools to foster the emotional intelligence of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

- What Is Automatic Thinking?

- Our Cognitive Bias: Construction of the Self-Concept

- Aaron Beck’s Cognitive Triad

- 50+ Examples of Positive and Negative Automatic Thoughts

- Cognitive Restructuring of Core Beliefs and Automatic Thoughts

- 5 CBT Worksheets For Challenging Negative Self-Talk and Automatic Thoughts

- A Take-Home Message

- References

What Is Automatic Thinking?

Automatic thinking refers to automatic thoughts that stem from beliefs people hold about themselves and the world (Soflau & David, 2017). Automatic thoughts can be considered “surface-level, non-volitional, stream-of-consciousness cognitions” that “can appear in the form of descriptions, inferences, or situation-specific evaluations” (Soflau & David, 2017).

As the name indicates, these automatic thoughts cannot be controlled by people directly, since they are reflexive reactions based on the beliefs people hold about themselves and the world. However, people can indirectly control these thoughts by challenging the beliefs that lead to them.

Relevant research into automatic thinking began with Aaron Beck’s research into how negative automatic thoughts affect the development of depression (Beck et al., 1979). Before long, researchers decided that positive automatic thoughts were also important to study, and particularly the relationship between both positive and negative automatic thoughts (Ingram & Wisnicki, 1988).

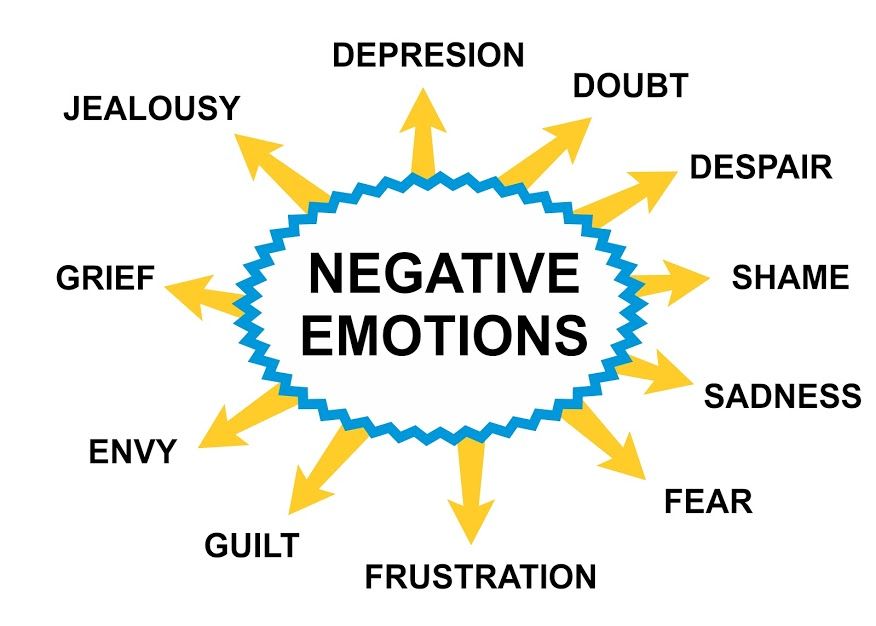

Studies have indicated that there are a variety of consequences of being disposed toward negative automatic thoughts rather than positive automatic thoughts.

In a study by Riley et al., their focus was on the relationship between automatic thoughts and depression in a research group of people living with HIV/AIDS. They found that in people with both depression and HIV/AIDS, negative automatic thoughts are associated with depressive symptoms, and vice versa (Riley et al., 2017).

In athletes, negative automatic thoughts can lead to burnout (Chang et al., 2017). Finally, in a sample of university students, negative automatic thoughts led to more mental health symptoms and decreased levels of self-esteem (Hicdurmaz et al., 2017).

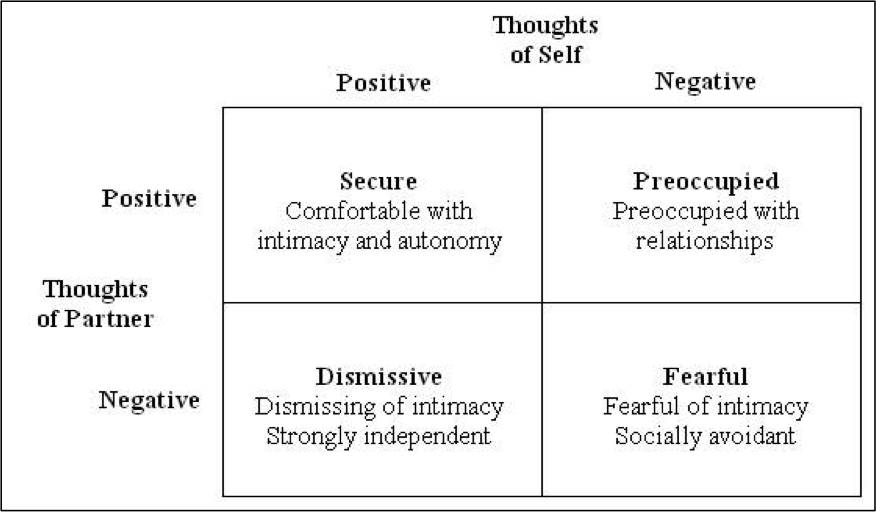

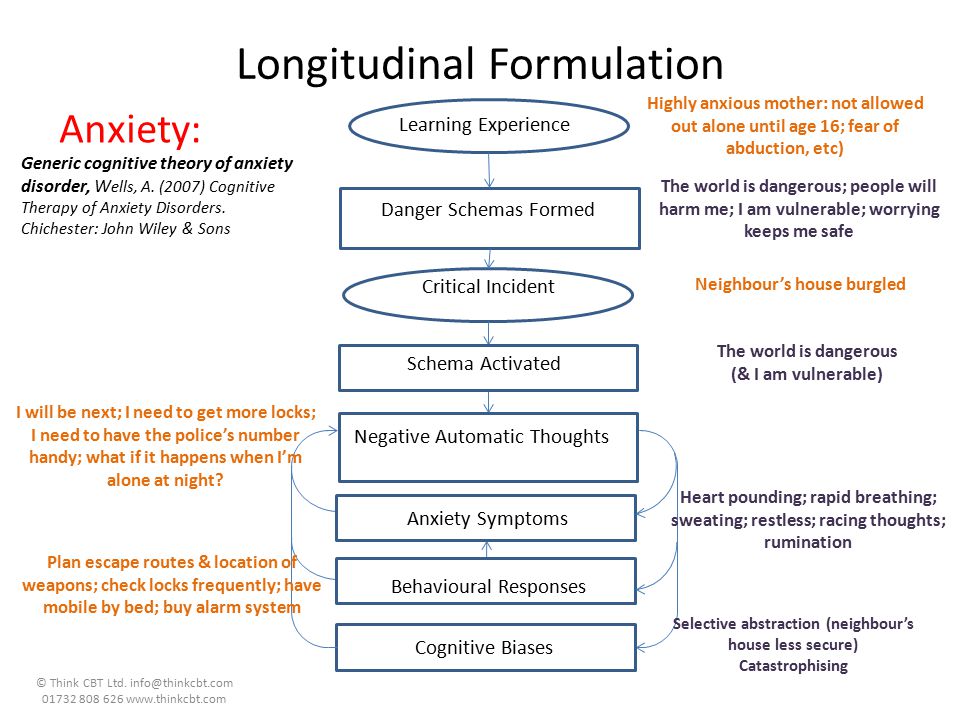

Our Cognitive Bias: Construction of the Self-Concept

Self-concept refers to how people perceive themselves and their past experiences, their abilities, their prospects for the future, and any other aspects of the self.

Aaron Beck’s cognitive triad (discussed below) deals with self-concept and the construction of the self. The basic idea of how our self-concepts and cognitive biases affect our lives has to do with automatic thoughts.

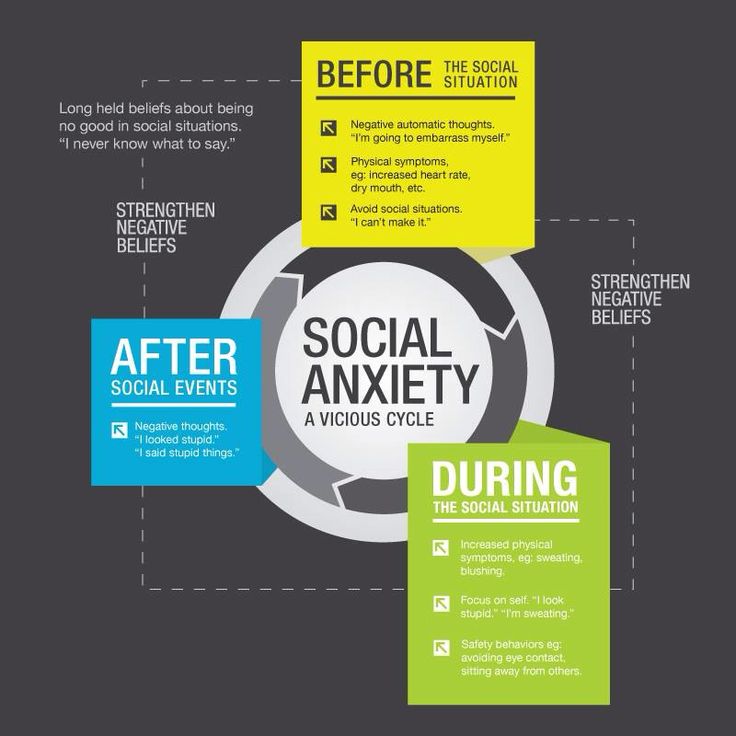

For example, someone with a negative self-referential schema is more likely to take things personally, leading to automatic thoughts like “People are not talking to me because I am an unlikable person,” rather than exploring other possibilities (Disner et al., 2017). A negative self-referential schema can also lead to more severe symptoms of depression.

Most importantly, a negative self-concept can lead to an unending cycle of negative thoughts.

This is because people with negative self-referential schemas exhibit attentional biases. For example, when asked to decide whether an adjective describes themselves or not, people with depression are more likely than a control group to select negative adjectives (Disner et al., 2017).

Depressive people also show an attentional bias by being quicker than healthy the control group to endorse negative adjectives and quicker to reject positive adjectives (Disner et al., 2017).

In turn, being likelier to endorse negative adjectives is correlated with longer depressive episodes (as reported afterward), demonstrating the cycle of negativity.

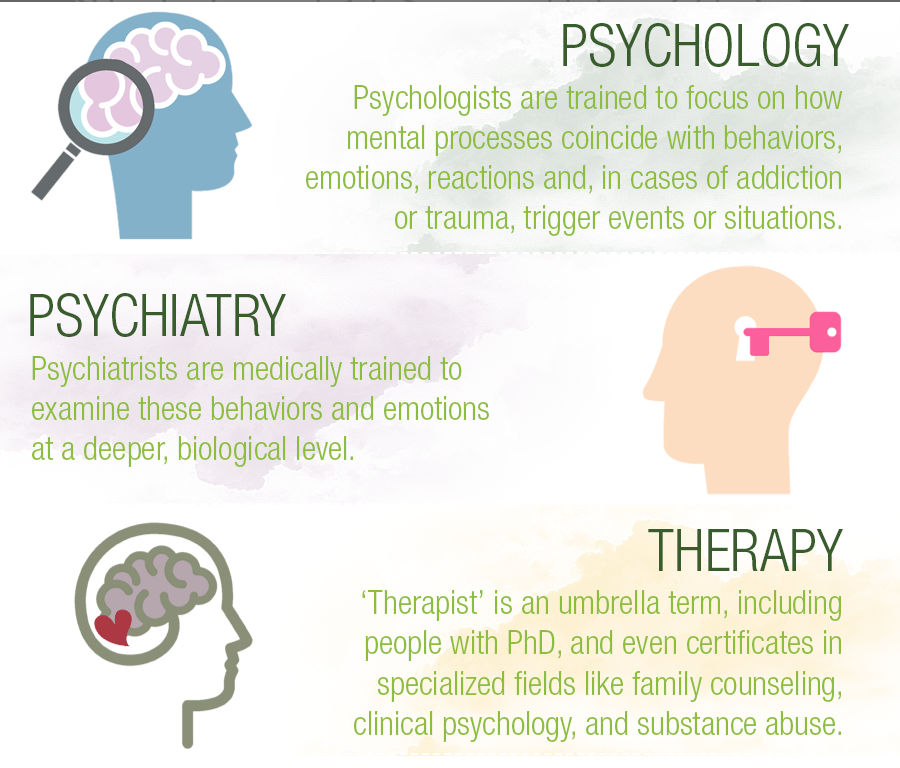

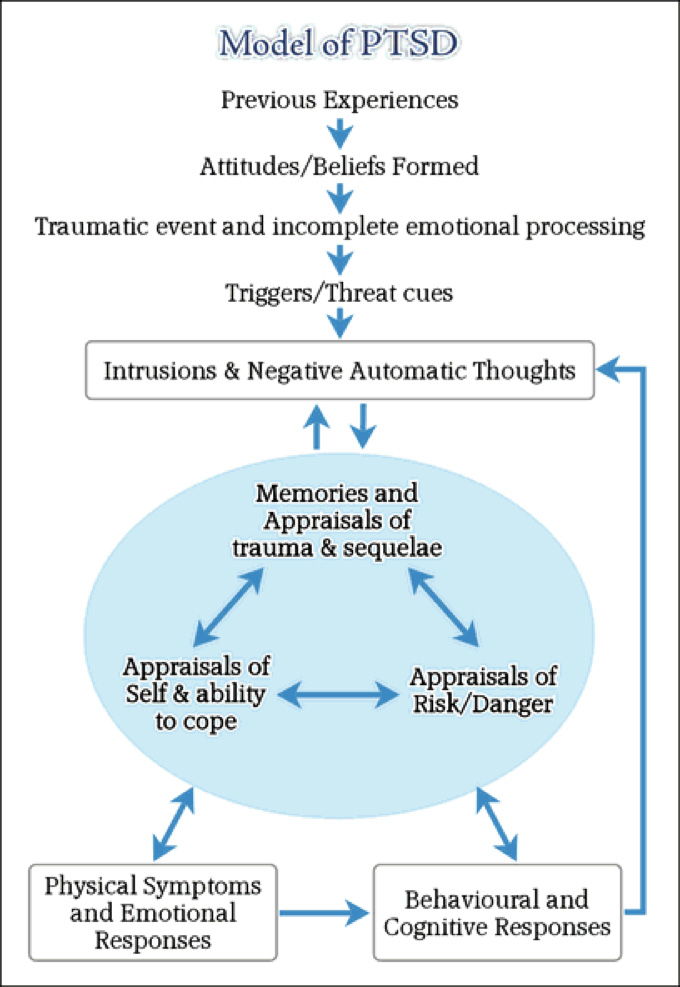

Aaron Beck’s Cognitive Triad

According to psychiatrist Aaron Beck and colleagues,

“[the] cognitive triad consists of three major cognitive patterns that induce the patient to regard himself, his future, and his experiences in an idiosyncratic manner.”

(1979)

According to Beck’s cognitive triad, someone who is depressed will automatically have a negative view of themselves, their experiences (that is, the things that the world around them causes to happen to them), and their future. According to this model, “the other signs and symptoms of the depressive syndrome” are “consequences of the activation of the negative cognitive patterns” (Beck et al., 1979).

According to Beck, this is because a depressed person “tends to perceive his present, his future, and the outside world (the cognitive triad) in a negative way and consequently shows a biased interpretation of his experiences, negative expectancies as to the probable success of anything he undertakes, and a massive amount of self-criticism” (Beck et al. , 1979).

, 1979).

In other words, people who are depressed have a negative view of themselves and their lives, and these negative views lead to further symptoms of depression.

These symptoms of depression often then lead people to have a negative view of themselves and their lives, creating a cycle of negativity.

50+ Examples of Positive and Negative Automatic Thoughts

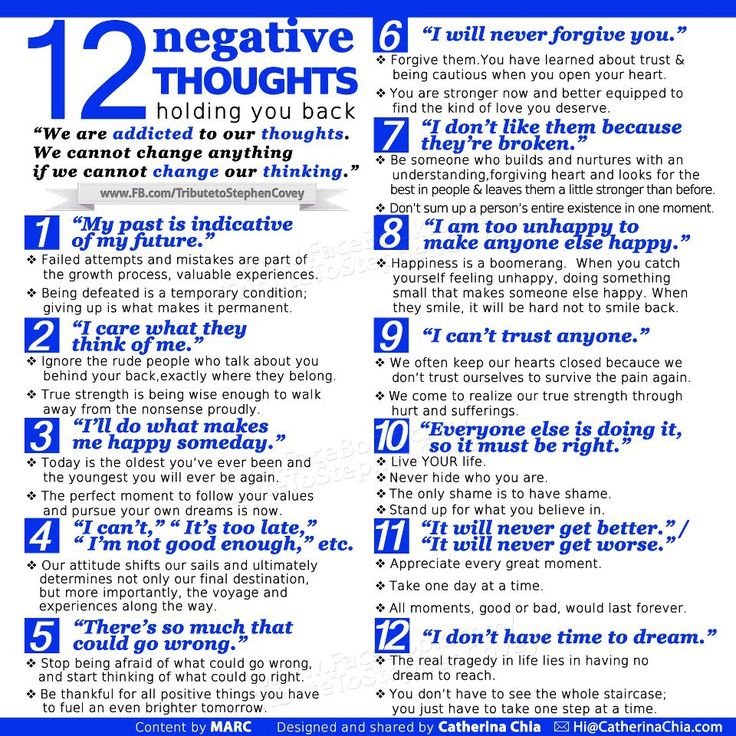

So, how do automatic thoughts actually present themselves? Since automatic thinking research began with negative thoughts, we’ll start with negative automatic thoughts.

According to the Automatic Thoughts Questionnaire (ATQ-30) developed by Steven Hollon and Philip Kendall in 1980, some examples of negative automatic thoughts include:

| “I feel like I’m up against the world.” “I’m no good.” “Why can’t I ever succeed?” “No one understands me.” “I’ve let people down.” “I don’t think I can go on.” “I wish I were a better person.  ” ”“I’m so weak.” “My life’s not going the way I want it to.” “I’m so disappointed in myself.” “Nothing feels good anymore.” “I can’t stand this anymore.” “I can’t get started.” “What’s wrong with me?” “I wish I were somewhere else.” | “I can’t get things together.” “I hate myself.” “I’m worthless.” “Wish I could just disappear.” “What’s the matter with me?” “I’m a loser.” “My life is a mess.” “I’m a failure.” “I’ll never make it.” “I feel so helpless.” “Something has to change.” “There must be something wrong with me.” “My future is bleak.” “It’s just not worth it.” “I can’t finish anything.” |

The revised version of the automatic thoughts questionnaire (ATQ-R) (Kendall et al., 1989), which is a measure still used as a basis for automatic thinking research (Koseki et al., 2013), lists the following positive items as additional examples of automatic thoughts (along with the 30 negative thoughts listed above):

“I’m proud of myself. ” ”“I feel fine.” “No matter what happens, I know I’ll make it.” “I can accomplish anything.” “I feel good.” | “I’m warm and comfortable.” “I feel confident I can do anything I set my mind to.” “I feel very happy.” “This is super!” “I’m luckier than most people.” |

According to Rick Ingram and Kathy Wisnicki (1988), some more examples of positive automatic thoughts include:

| “I am respected by my peers.” “I have a good sense of humor.” “My future looks bright.” “I will be successful.” “I’m fun to be with.” “I am in a great mood.” “There are many people who care about me.” “I’m proud of my accomplishments.” “I will finish what I start.” “I have many good qualities.” “I am comfortable with life.” “I have a good way with others.” “I am a lucky person.” “I have friends who support me.” “Life is exciting.” | “I enjoy a challenge.” “My social life is terrific.  ” ”“There’s nothing to worry about.” “I’m so relaxed.” “My life is running smoothly.” “I’m happy with the way I look.” “I take good care of myself.” “I deserve the best in life.” “Bad days are rare.” “I have many useful qualities.” “There is no problem that is hopeless.” “I won’t give up.” “I state my opinions with confidence.” “My life keeps getting better.” “Today I’ve accomplished a lot.” |

Cognitive Restructuring of Core Beliefs and Automatic Thoughts

Positive automatic thoughts can offset the negative effects of both negative automatic thoughts and stress in general.

For example, people with frequent positive automatic thoughts are likely to respond to stress by feeling that their lives are more meaningful, while people with infrequent positive automatic thoughts are likely to respond to stress by feeling that their lives are less meaningful (Boyraz & Lightsey, 2012).

Furthermore, higher levels of positive automatic thoughts are correlated with higher levels of happiness (Lightsey, 1994).

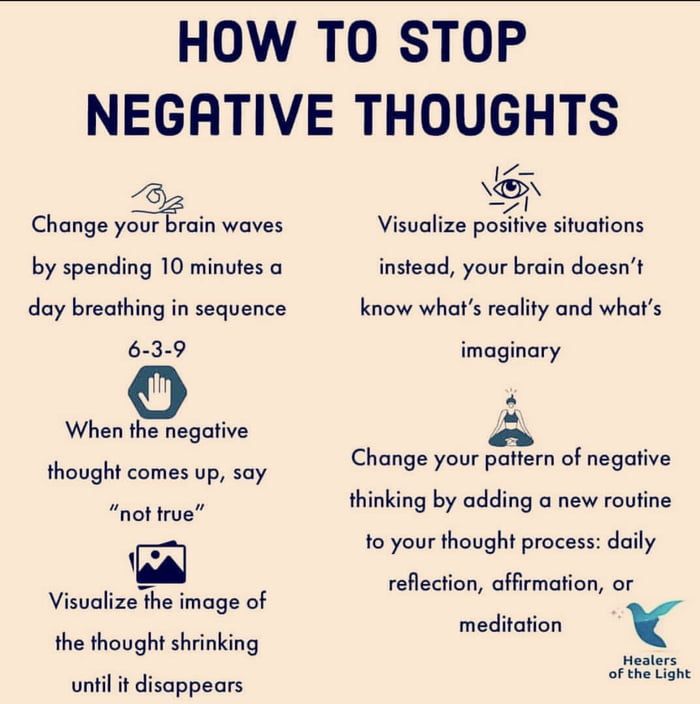

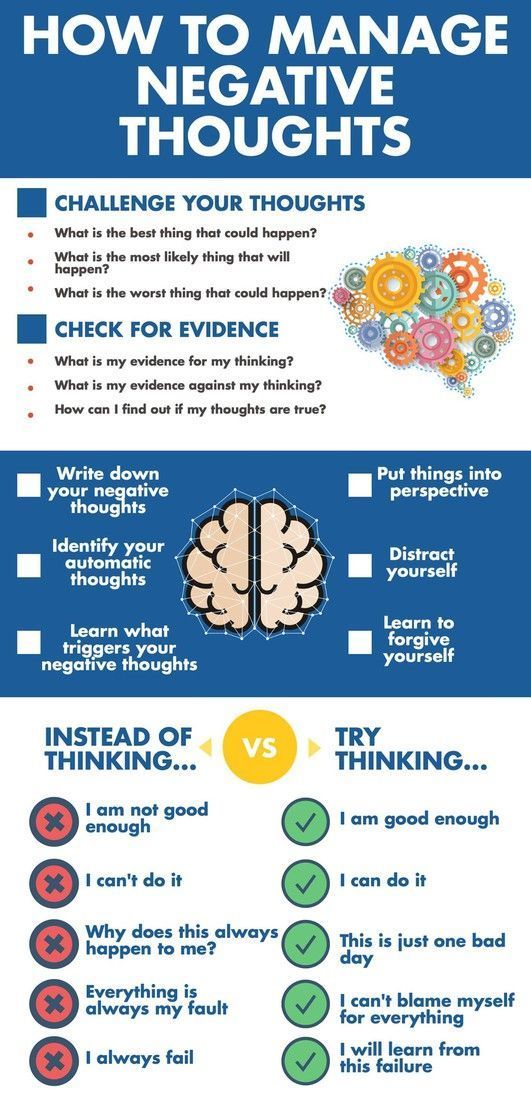

This indicates that in order to have better mental health outcomes, one should reduce their negative automatic negative thoughts and increase their positive automatic thoughts. This is because negative thinking is natural and it’s impossible to completely eliminate it, but outweighing negative thoughts with positive thoughts is possible.

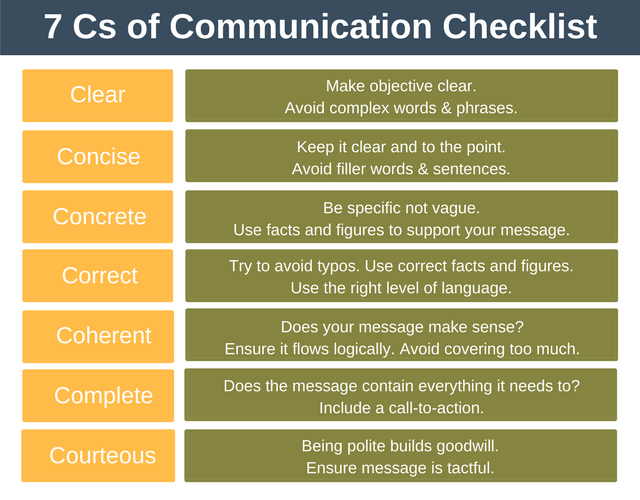

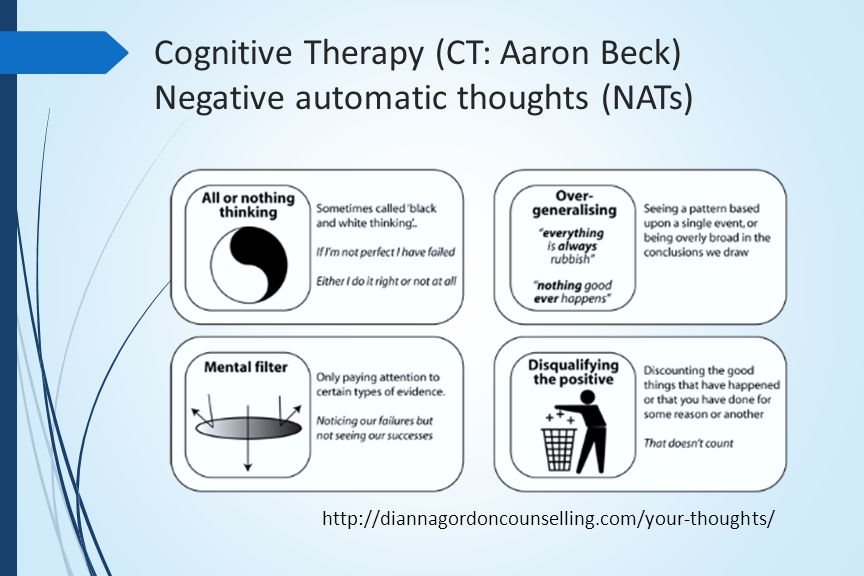

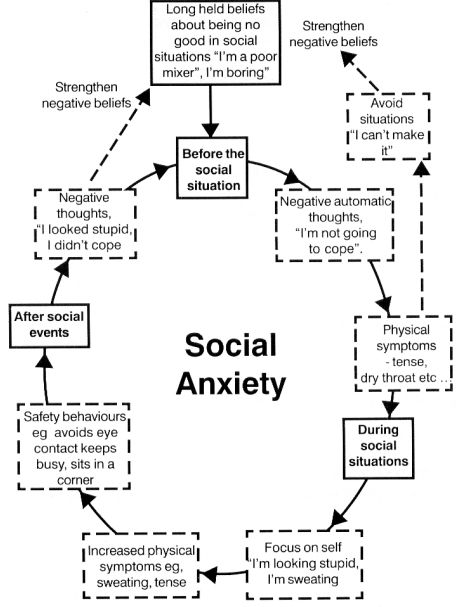

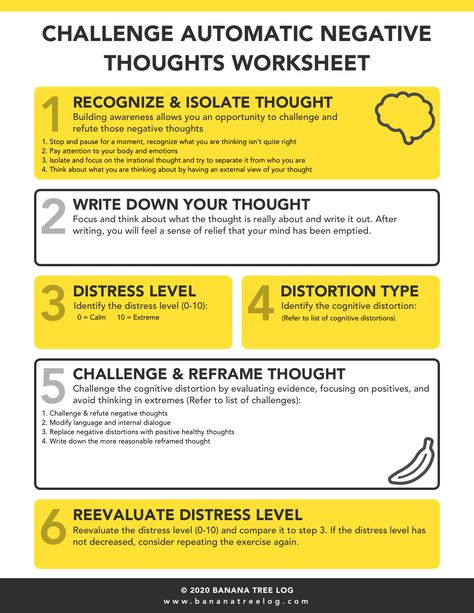

One way to do this is with cognitive restructuring (CR), which involves (Hope et al., 2010):

- Identification of problematic cognitions known as automatic thoughts;

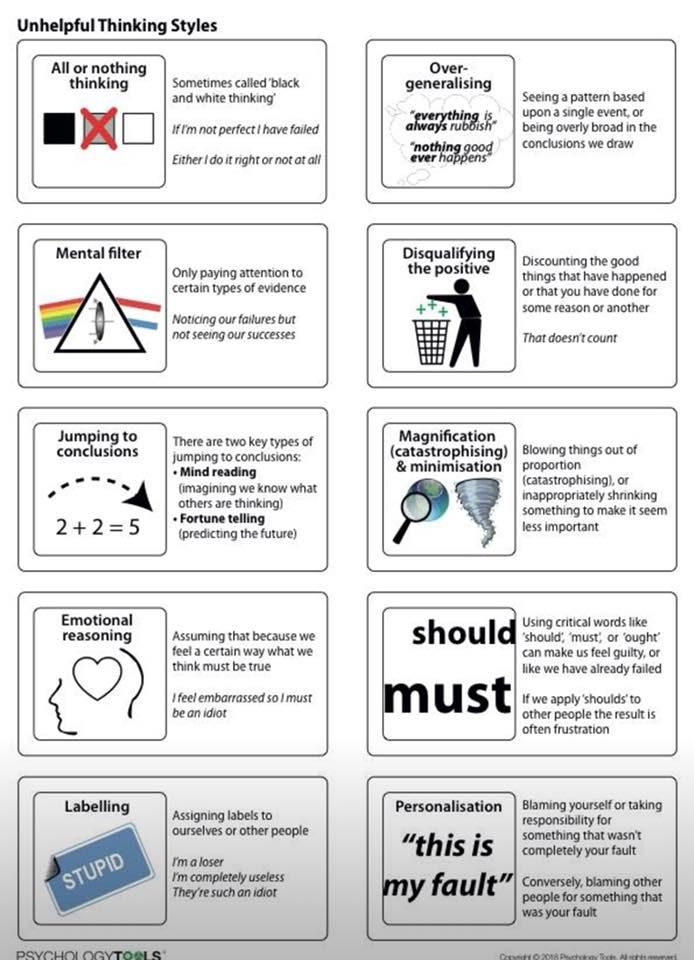

- Identification of the cognitive distortions in the automatic thoughts;

- A rational disputation of automatic thoughts with Socratic dialogue;

- Development of a rational rebuttal to the automatic thoughts.

Research in CR with automatic thoughts indicates that effective CR might focus on negative self-evaluative automatic thoughts, especially ones triggered by certain situations.

One example could be someone whose automatic thought when faced with an uncomfortable situation is, “I don’t know what to say” (Hope et al., 2010). Focusing on this type of thought is helpful because it can easily be disproved with exposure and role-playing.

Another effective CR method when dealing with other-referent automatic thoughts (as opposed to self-referent automatic thoughts) is to minimize the consequences of the negative automatic thoughts. For example, a person could ask herself, “So what if she thinks you are boring?”

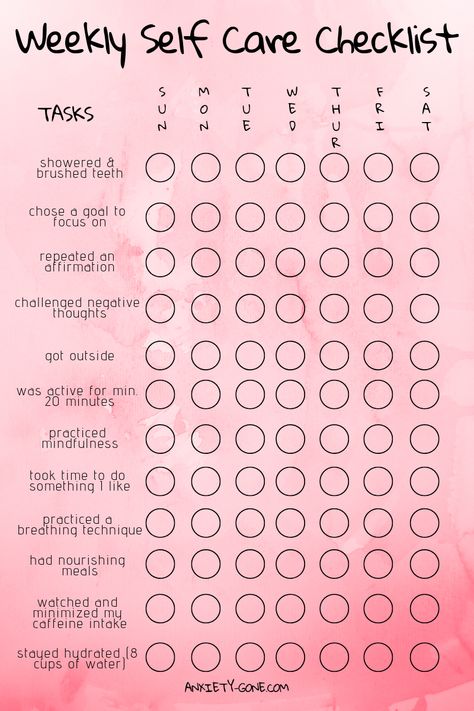

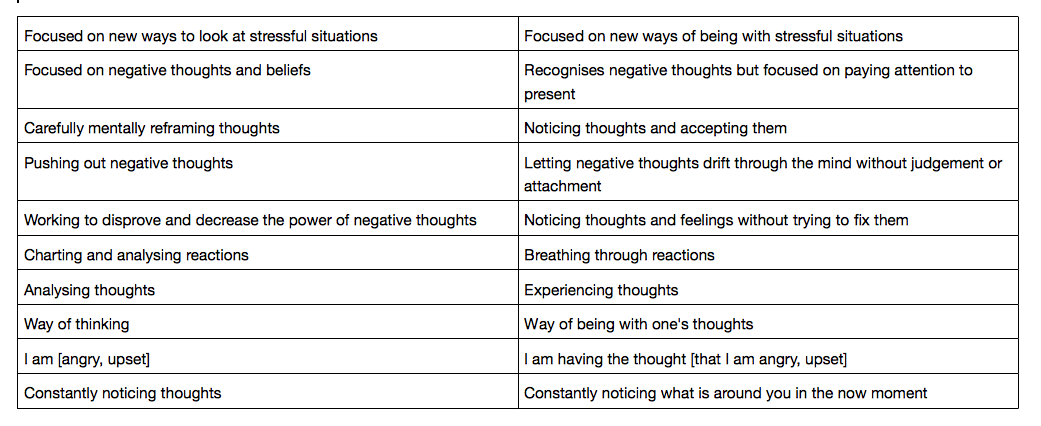

Aside from CR, research indicates that people with higher levels of dispositional mindfulness are less likely to experience automatic negative thoughts, potentially because they can more easily let go of negative thoughts or direct their attention elsewhere (Frewen et al., 2008).

That study also indicated that a mindfulness intervention derived from both mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy was effective at reducing negative thoughts.

This indicates that along with positive thinking, mindfulness is another way to counteract negative automatic thinking.

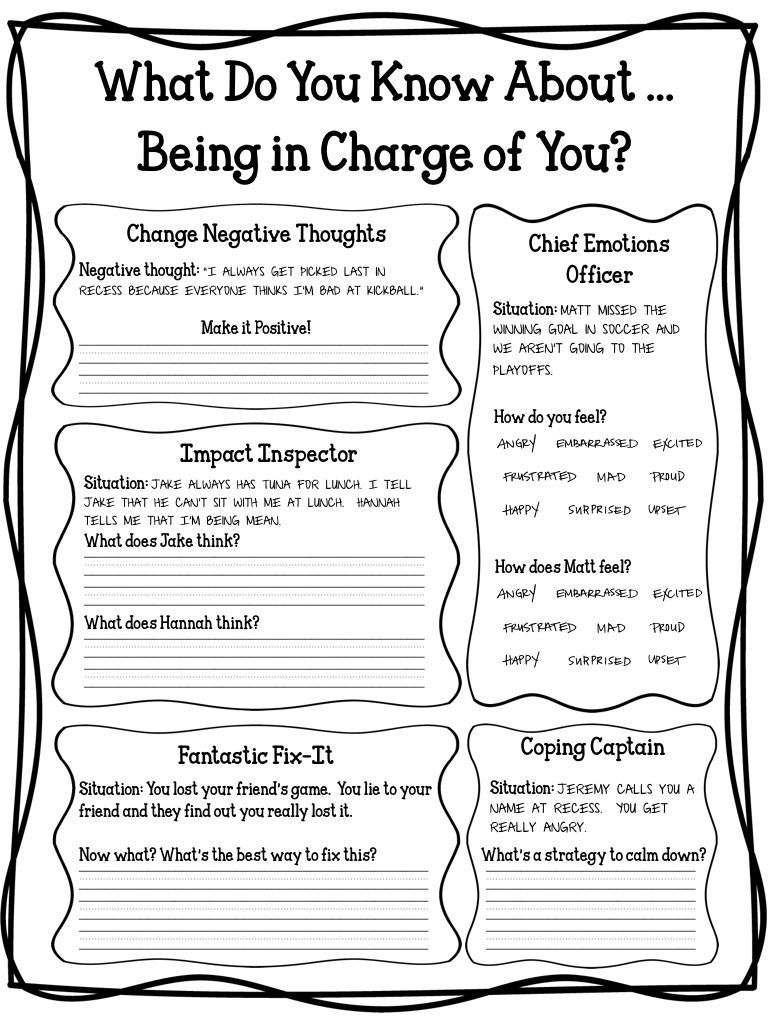

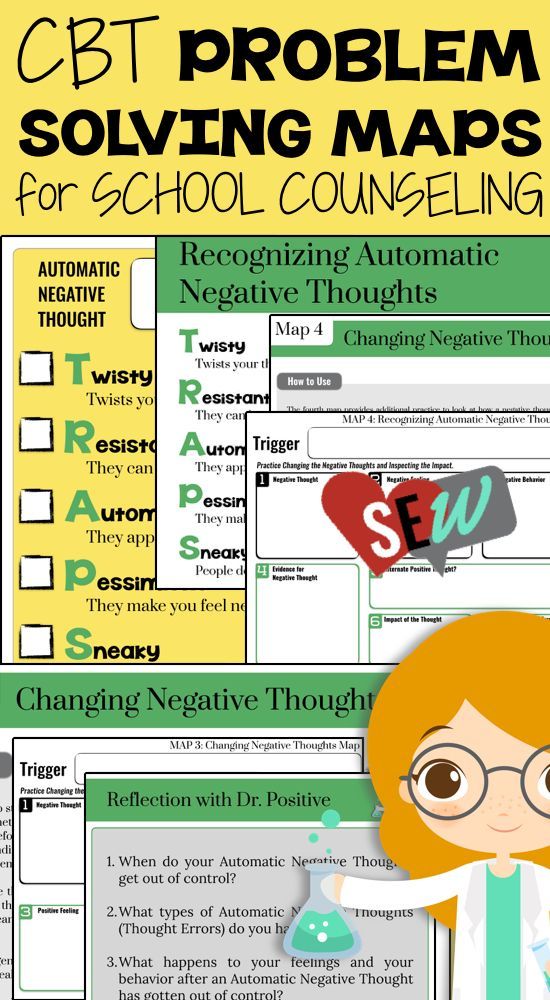

5 CBT Worksheets for Challenging Negative Self-Talk and Automatic Thoughts

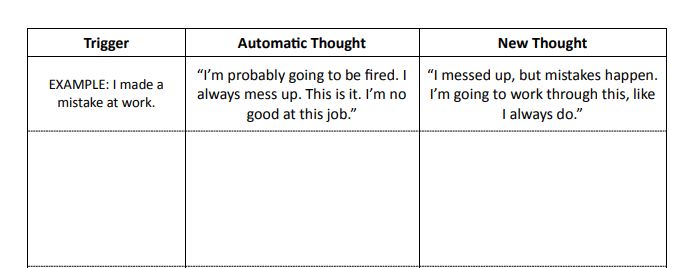

For practical ways to challenge and dispute negative automatic thinking, one can try using one of these worksheets.

They’re based on the principles of cognitive-behavioral therapy, commonly referred to as CBT.

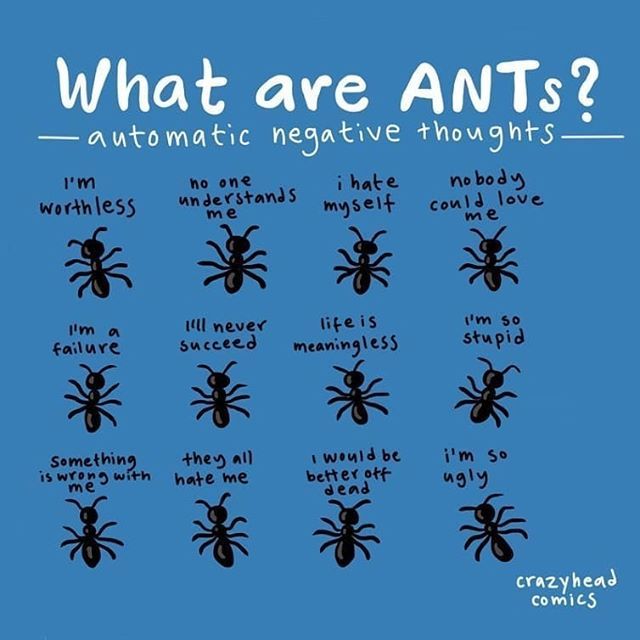

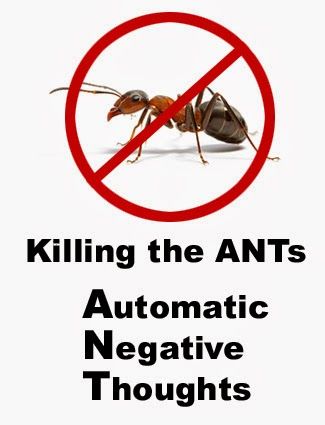

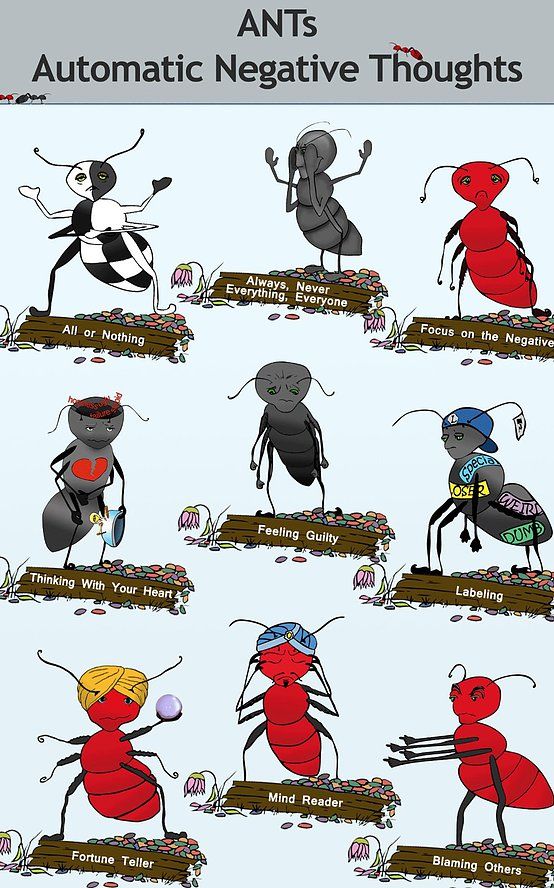

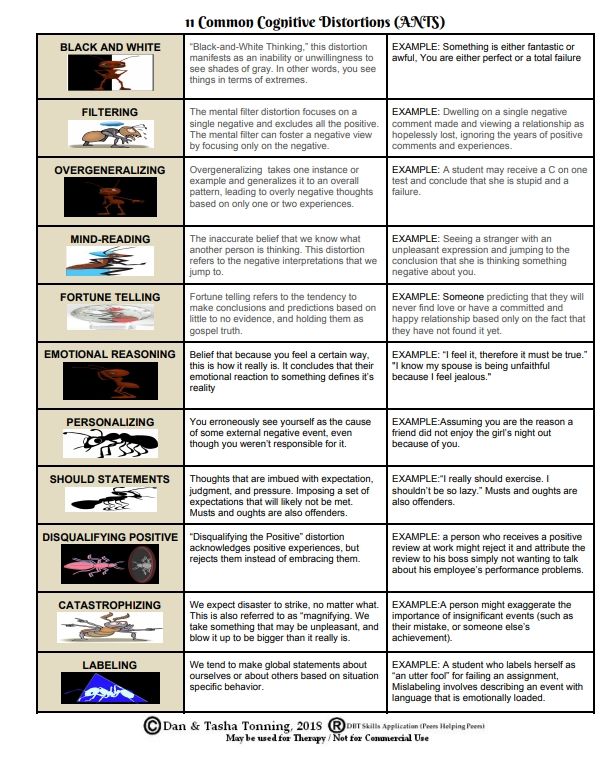

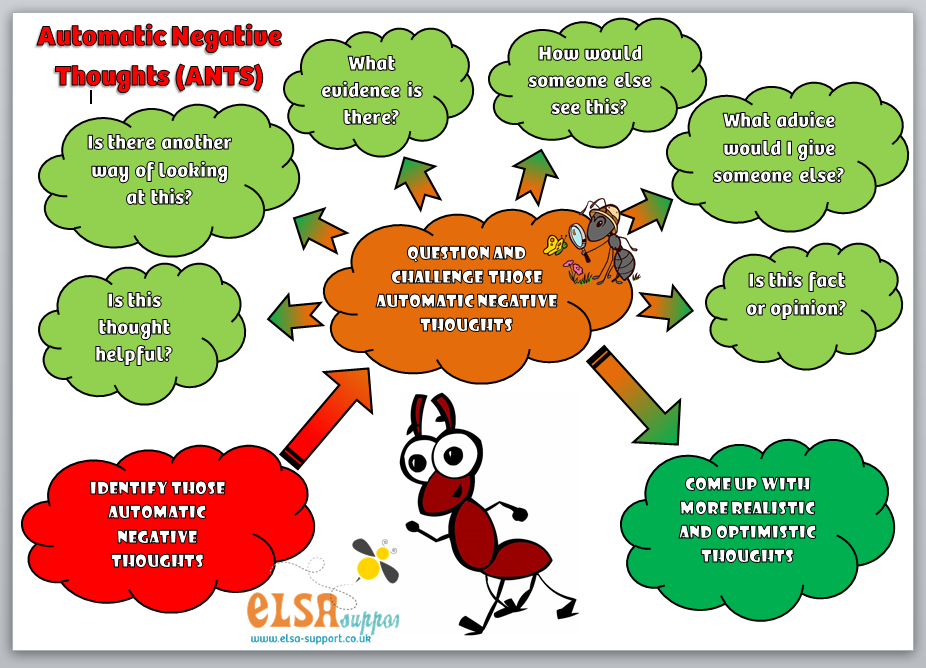

Getting Rid of ANTS: Automatic Negative Thoughts

This simple worksheet starts out by offering some information about automatic thoughts and their consequences.

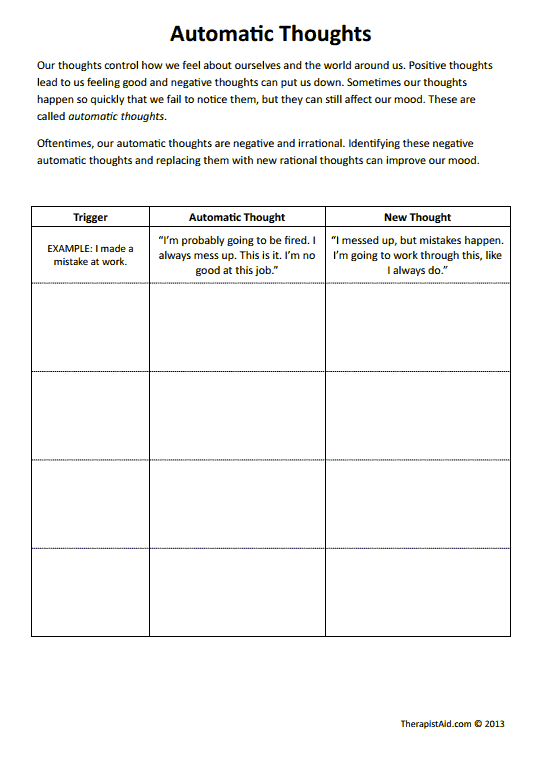

The rest of the worksheet is split into three columns: Trigger, Automatic Negative Thought (ANT), and Adaptive Thought, and aims to help people understand and dispute (if necessary) their automatic thoughts. This worksheet is a great introduction to automatic thoughts.

Identifying ANTs: Challenging Different Types of Automatic Thought

Identifying ANTS gives an overview of ten different types of ANTS and what they look like in daily life.

In the space provided, you can practice identifying each type of ANT, to help you better understand your subconscious thoughts and take the first step toward replacing them.

Along with the exercise, you’ll find five Challenge Questions you can use to tackle each ANT when you notice it popping up.

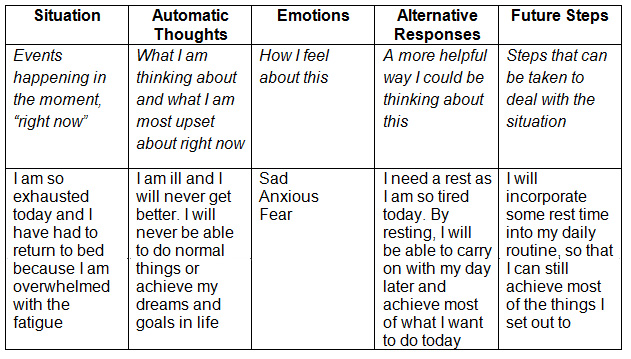

Thought/Feeling Record Worksheet

This worksheet focuses on specific negative automatic thoughts, one at a time, and examine what triggers them, as well as their consequences.

This exercise can help people understand their negative automatic thoughts and replace them with positive thoughts. It’s excellent for someone looking to extensively examine their individual thoughts.

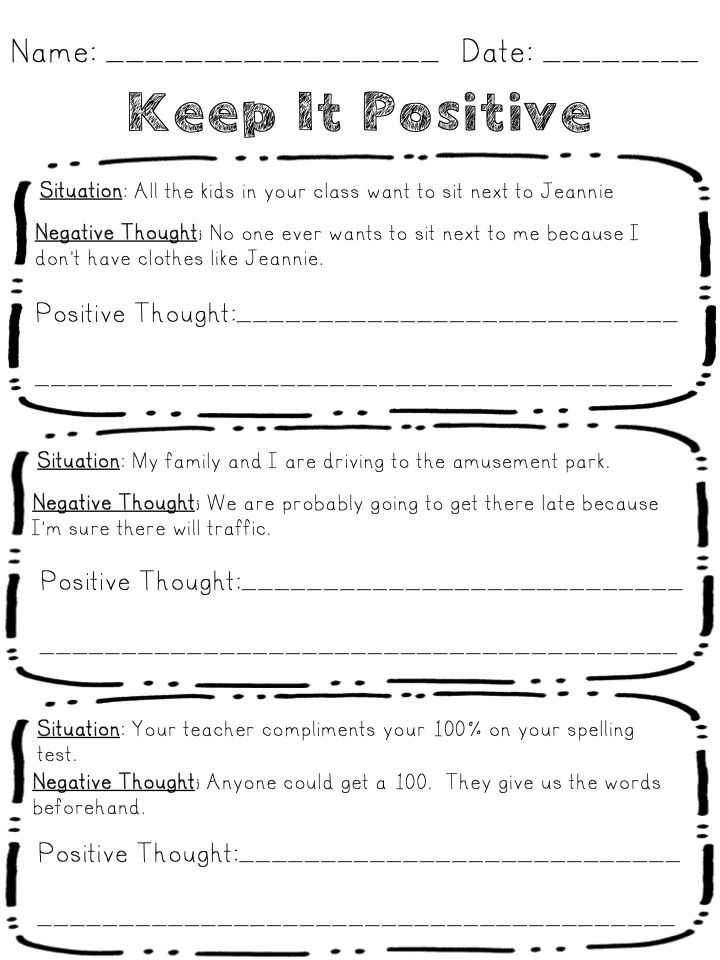

Positive Replacement Thoughts Worksheet

This Positive Replacement Thoughts Worksheet also asks users to list all the automatic negative thoughts that come to their minds, then asks them to thoughtfully come up with alternative positive thoughts with which they can replace the negative thoughts.

It is more concise than the two Thought Records above, and since it does not offer information about automatic thoughts, it is a good option for someone who understands the concept and is ready to start replacing their negative thoughts with positive ones.

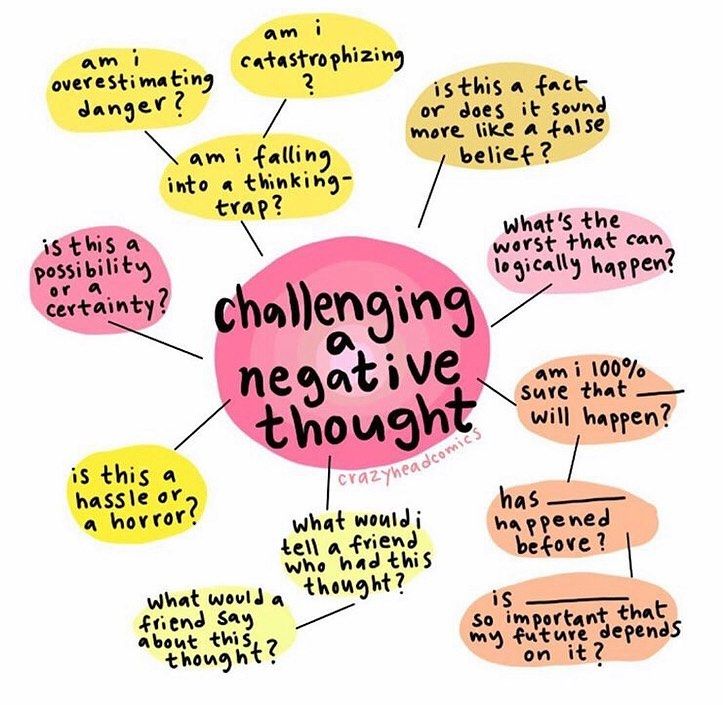

Questions for Challenging Thoughts

Another simple resource, this one-page worksheet serves as an appendix of questions focused on challenging automatic thoughts.

It includes a list of questions that users can use to dispute negative thoughts, and works well with any of the other Automatic Thoughts exercises on this page.

This straightforward tool is a great grab-and-go option for people who want to use Socratic Questioning and fact-checking techniques in dealing with automatic negative thoughts.

A Take-Home Message

Negative automatic thinking not only leads to poor mental health outcomes, but it can also lead to a cycle of negativity—certain mental health issues can lead to increased negative thoughts, and vice versa.

While these thoughts can seem impossible to avoid, it’s possible to use positive thinking to counteract them. And through CBT methods, people can train themselves to think more positive thoughts in general.

At times, “the power of positive thinking” sounds like it’s just a pseudo-inspirational cliché. In this case, though, having healthy beliefs about oneself can lead to more positive automatic thoughts, which can indeed be beneficial.

Most importantly, thinking positive thoughts and having positive beliefs is absolutely free of cost, so it doesn’t hurt to try it out.

What do you think of negative automatic thoughts? Have you ever confronted your negative automatic thoughts, and if so, how did you do it? We’d love to know your thoughts in the comments below.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Emotional Intelligence Exercises for free.

- Beck, A. T., Rush, A. J., Shaw, B. F., & Emery, G. (1979). Cognitive Therapy of Depression.

New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

New York, NY: The Guilford Press. - Boyraz, G., & Lightsey, O. R. (2012). Can Positive Thinking Help? Positive Automatic Thoughts as Moderators of the Stress-Meaning Relationship. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 82(2), 267-277.

- Chang, K. H., Lu, F. J. H., Chyi, T., Hsu, Y. W., Chan, S. W., & Wang, E. T. W. (2017). Examining the stress-burnout relationship: the mediating role of negative thoughts. PeerJ, 5(1), e4181.

- Disner, S. G., Shumake, J. D., & Beevers, C. G. (2017). Self-referential schemas and attentional bias predict severity and naturalistic course of depression symptoms. Cognition & Emotion, 31(4), 632-644.

- Frewen, P. A., Evans, E. M., Maraj, N., Dozois, D. J. A., & Partridge, K. (2008). Letting Go: Mindfulness and Negative Automatic Thinking. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 32(6), 758-774.

- Hicdurmaz, D., Inci, F., & Karahan, S. (2017). Predictors of Mental Health Symptoms, Automatic Thoughts, and Self-Esteem Among University Students.

Psychological Reports, 120(4), 650-669.

Psychological Reports, 120(4), 650-669. - Hollon, S. D., & Kendall, P. C. (1980). Cognitive self-statements in depression: Development of an automatic thoughts questionnaire. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 4(4), 383-395.

- Hope, D. A., Burns, J. A., Hayes, S. A., Herbert, J. D., & Warner, M. D. (2010). Automatic Thoughts and Cognitive Restructuring in Cognitive-Behavioral Group Therapy for Social Anxiety Disorder. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 34(1), 1-12.

- Ingram, R. E., & Wisnicki, K. S. (1988). Assessment of Positive Automatic Cognition. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56(6), 898-902.

- Kendall, P. C., Howard, B. L., & Hays, R. C. (1989). Self-referent speech and psychopathology: The balance of positive and negative thinking. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 13(6), 583-598.

- Koseki, S., Noda, T., Yokoyama, S., Kunisato, Y., Ito, D., Suyama, H., Matsuda, T., Sugimura, Y.

, Ishihara, N., Shimizu, Y., Nakazawa, K., Yoshida, S., Arima, K., & Suzuki, S. (2013). The relationship between positive and negative automatic thought and activity in the prefrontal and temporal cortices: A multi-channel near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(1), 352-359.

, Ishihara, N., Shimizu, Y., Nakazawa, K., Yoshida, S., Arima, K., & Suzuki, S. (2013). The relationship between positive and negative automatic thought and activity in the prefrontal and temporal cortices: A multi-channel near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 151(1), 352-359. - Lightsey, O. R. (1994). Thinking Positive as a Stress Buffer – The Role of Positive Automatic Cognitions in Depression and Happiness. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 41(3), 325-334.

- Rana, M., Sthapit, S., & Sharma, V. D. (2017). Assessment of Automatic Thoughts in Patients with Depressive Illness at a Tertiary Hospital in Nepal. Journal of the Nepal Medical Association, 56(206), 248-255

- Riley, K. E., Lee, J. S., & Safren, S. A. (2017). The Relationship Between Automatic Thoughts and Depression in a Cognitive-Behavioral Treatment for People Living with HIV/AIDS: Exploring Temporality and Causality. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41(5), 712-719.

- Soflau, R., & David, D. O. (2017). A Meta-Analytical Approach of the Relationships Between the Irrationality of Beliefs and the Functionality of Automatic Thoughts. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 41(2), 178-192.

Identifying Automatic Thoughts in CBT

What Are Automatic Thoughts?

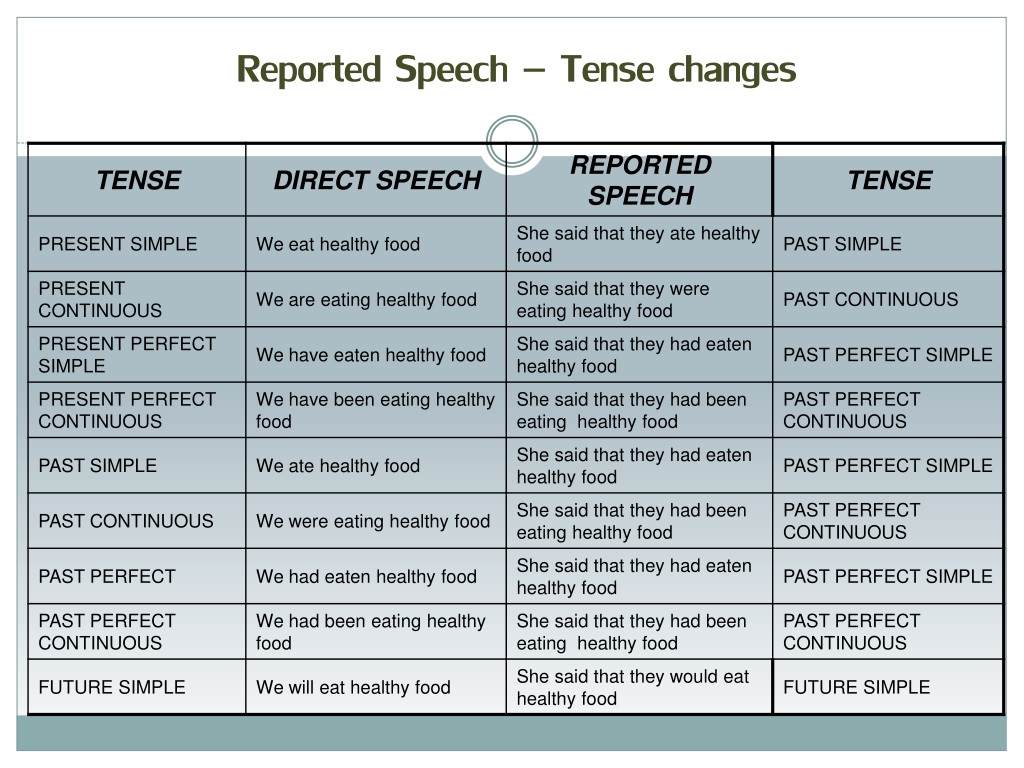

If you’re working through this book in order, you’ve been spending some time identifying and thinking about feelings. Some feelings may seem predictable in certain situations, but others may be puzzling. Sometimes we feel an emotion seemingly out of the blue, too strongly for what’s going on, or in a way that doesn’t seem to fit the situation at all. The key to understanding feelings is identifying the thoughts associated with them.

Thoughts influence much of our experience of the world, including our emotional experience. In this book, we’ll be referring to a specific kind of thoughts that we call “automatic thoughts.” Automatic thoughts are the thoughts that automatically arise in our minds all throughout the day. Often, we are completely unaware we are even having thoughts, but with a little instruction and practice, you can learn to easily identify them, and as a result, get a better handle on your mood and behavior.

Often, we are completely unaware we are even having thoughts, but with a little instruction and practice, you can learn to easily identify them, and as a result, get a better handle on your mood and behavior.

Why Focus So Much on Thoughts?

Our minds are thought processing machines, creating and sifting through as many as 60,000 ideas in a given day. If we were to attend to each one of these, we would be overwhelmed by the flood of information. Thankfully, that’s not how our brain works. Most thoughts enter and leave our minds out of our awareness. The brain is pretty good at filtering what it deems to be unimportant information and focusing on what seems to be most salient. It does this by focusing on certain aspects of a situation, then assigning some kind of meaning to those aspects, resulting in our thoughts and opinions about things.

This process works well most of the time, but sometimes we focus on less important bits of information, filtering out the more relevant parts. Other times, we assign meaning to something that isn’t totally grounded in the actual facts of the situation. Take for example a pretty common experience, the job performance review. It’s not uncommon for people who have a mostly good performance review to filter out most of the praise and instead fixate on the one or two areas where there’s room for improvement. We call this phenomenon negative filtering, which means filtering out all but the negative information. Despite the majority of the feedback being positive, negative filtering might cause us to perceive the review as wholly negative, triggering emotions of disappointment, sadness, or anxiety.

Other times, we assign meaning to something that isn’t totally grounded in the actual facts of the situation. Take for example a pretty common experience, the job performance review. It’s not uncommon for people who have a mostly good performance review to filter out most of the praise and instead fixate on the one or two areas where there’s room for improvement. We call this phenomenon negative filtering, which means filtering out all but the negative information. Despite the majority of the feedback being positive, negative filtering might cause us to perceive the review as wholly negative, triggering emotions of disappointment, sadness, or anxiety.

The above example highlights a very common dynamic: Automatic thoughts have the potential to trigger intense negative emotions. Usually, we are more aware of the emotions themselves than the thoughts that trigger them. However, in most instances it is the automatic thoughts that play the largest role in determining how we feel, not the situation itself. Learning to examine these thoughts allows us to better understand and deal with our emotions, modulating them before they get too intense or overwhelming.

Learning to examine these thoughts allows us to better understand and deal with our emotions, modulating them before they get too intense or overwhelming.

Take the following examples using the same situation of the performance review:

Joan received a performance review in which 90% of the feedback was positive, and 10% was somewhat negative. Afterward, she found herself seething with rage, unable to concentrate, and eventually leaving early to have a drink at home.

Dante on the other hand, received the same exact feedback, and afterward found himself to be in a good mood the rest of the day. When it was time to go home, he decided to spend a little more time working on a presentation he would be giving next month.

Now, there was no difference in the information given to these individuals, but there was a significant difference in how they felt afterward. The key to understanding their differing responses is to examine their automatic thoughts about the situation. Joan had the thoughts “I’m not appreciated here,” “My boss doesn’t know what she’s talking about,” and “It’s useless even trying to do a good job here with these knuckleheads in charge.” Joan probably had many other thoughts during the course of her hour-long interview, but these are the ones her mind singled out as most important, and as a result, she felt angry and resentful and decided that she couldn’t finish or it wasn’t worth finishing the day of work.

Joan had the thoughts “I’m not appreciated here,” “My boss doesn’t know what she’s talking about,” and “It’s useless even trying to do a good job here with these knuckleheads in charge.” Joan probably had many other thoughts during the course of her hour-long interview, but these are the ones her mind singled out as most important, and as a result, she felt angry and resentful and decided that she couldn’t finish or it wasn’t worth finishing the day of work.

Conversely, Dante had thoughts of “It’s nice to hear I’ve improved at this,” “ She thinks I’m doing pretty well in most areas,” and “I don’t have perfect scores across every domain, but I did pretty well in most, and can definitely spend more time to improve my performance in the areas that are lacking.” These thoughts allowed him to feel more positive emotions throughout the day, and importantly, to feel motivated to be more effective. The above examples highlight the way thoughts affect our mood and our behavior:

Automatic thoughts can actually take many forms. They can be verbal as demonstrated in the example above. They can also be single words instead of sentences: “Crap!” Finally, many people from time to time have automatic thoughts in the form of images: Using the above scenario, Joan may have had an image of herself working hard at her desk while her boss and coworkers were all goofing off. Regardless of the form automatic thoughts take, we can learn to examine them to identify their underlying meaning and their connection to our emotions and behavior.

They can be verbal as demonstrated in the example above. They can also be single words instead of sentences: “Crap!” Finally, many people from time to time have automatic thoughts in the form of images: Using the above scenario, Joan may have had an image of herself working hard at her desk while her boss and coworkers were all goofing off. Regardless of the form automatic thoughts take, we can learn to examine them to identify their underlying meaning and their connection to our emotions and behavior.

How to Identify Automatic Thoughts

Some people find this skill difficult at first, but quickly catch on. The key to identifying automatic thoughts is to look for what comes to mind when an emotion arises. Example: Aaliyah discovers on social media that one of her friends, Ricardo, had a get-together with some friends and didn’t invite her. She immediately had the feeling of a pit in her stomach and identified the emotion as sadness. In that moment she asked herself, “What is running through my mind?” She was able to identify the following thoughts:

1. Ricardo doesn’t really like me.

Ricardo doesn’t really like me.

2. I’m never invited to anything.

3. No one really likes me.

Given the extreme nature of these thoughts, a profound feeling of sadness is pretty understandable. By writing out her actual thoughts, however, Aaliyah was able to process them differently and see how extreme they were. Although she believed them to be true on one level, identifying and writing out her thoughts helped her to understand where her emotions were coming from. The exercise also helped her see she was making some pretty broad assumptions that she didn’t wholeheartedly believe. Afterward, she felt a little better, and some of her sadness lifted.

This process of recognizing thoughts as thoughts is a demonstration of what is termed metacognition. Metacognition is the process by which we develop an awareness and understanding of our thinking. As is the case in the example, merely becoming aware of the thought process helps us distance ourselves from our reflexive cognitive responses and reevaluate them. It is hard to overstate how powerful a tool this can be in changing our feelings and behavior. All of the skills in this book rely on metacognition as the foundation.

It is hard to overstate how powerful a tool this can be in changing our feelings and behavior. All of the skills in this book rely on metacognition as the foundation.

Sometimes it’s hard to identify a thought running through your mind, so another way of identifying the automatic thought is to look for the meaning of the situation. In Aaliyah’s example, if she were unable to identify any obvious thoughts she might ask herself, “What does it mean to me that Ricardo didn’t invite me? Maybe it’s that I’m afraid no one likes me.” The thought “No one likes me,” is the hidden meaning her mind has assigned to this event.

Another way of uncovering more hidden thoughts is to ask yourself, “What’s the worst part of this, and why?” Here the answer might be that Aaliyah believes she never gets invited to anything, and that’s painful because she concludes that it means no one likes her.

Finally, if these methods don’t deliver results, you can identify the emotion then work backward. The previous chapter identified some of the reasons different emotions arise. For instance, anger is usually a response to mistreatment of ourselves or someone we care about. Had Aaliyah felt anger after seeing that Ricardo had not invited her to the get-together, she could have 1) identified her anger, 2) determined that it was probably a reaction to some perceived mistreatment, then 3) formulated a thought involving being mistreated in the situation. She might have uncovered the thought “Ricardo isn’t treating me as he should because I’ve always been a good friend to him.” By using the emotion as a clue, we can play detective in discovering the mystery of the missing automatic thought.

The previous chapter identified some of the reasons different emotions arise. For instance, anger is usually a response to mistreatment of ourselves or someone we care about. Had Aaliyah felt anger after seeing that Ricardo had not invited her to the get-together, she could have 1) identified her anger, 2) determined that it was probably a reaction to some perceived mistreatment, then 3) formulated a thought involving being mistreated in the situation. She might have uncovered the thought “Ricardo isn’t treating me as he should because I’ve always been a good friend to him.” By using the emotion as a clue, we can play detective in discovering the mystery of the missing automatic thought.

An Invaluable Tool: The Thought Record

A thought record is a tool you can use to clarify the thoughts responsible for unwanted feelings and behaviors. In this chapter we introduce you to a basic thought record to help you develop your metacognitive ability. In later chapters, we add to it to help you practice more sophisticated cognitive therapy techniques, such as cognitive restructuring.

Using a thought record is a skill that can help you identify and clarify the thoughts that are leading to more problematic emotions. By practicing identifying thoughts in challenging situations, you develop and strengthen the skill of metacognition. With some practice, you can gain the ability to quickly identify dysfunctional automatic thoughts in the moment, and get some distance from them to lessen the intensity of your emotion. The button below links to an example of a completed thought record.

Instructions for Completing the Thought Record:

It’s best to complete a thought record about a difficult situation, or one in which you feel a lot of negative emotion. Thought records work best when they’re completed close to the event. It’s also helpful to have a little distance from the intensity of the situation so your thoughts aren’t completely clouded by overwhelming emotion. Complete the following steps to get the most out of the thought record:

1. Identify the situation in one sentence or less. Make sure you do so as objectively as possible without editorializing. For example: I said, “Hello” to Nicole, but she didn’t respond. Not: I said, “Hello” to Nicole but she ignored me because she hates me.

Identify the situation in one sentence or less. Make sure you do so as objectively as possible without editorializing. For example: I said, “Hello” to Nicole, but she didn’t respond. Not: I said, “Hello” to Nicole but she ignored me because she hates me.

2. Skip to the Emotions column. It’s easier to identify emotions then work back to the thoughts. Identify any emotions you felt at the time. Don’t get emotions confused with thoughts. Emotions are one word, and are usually some synonym for joy, fear, sadness, disgust, or anger. Feel free to identify as many or as few emotions as are present at the time.

3. Rate the intensity of each emotion on a scale from 0-100. It’s not an exact science, so just go with your gut on this one.

4. Identify the thoughts running through your mind at the time. Thoughts can be words, full sentences, or images. If you have trouble remembering, consider each emotion you identified in the previous step, then work backwards to figure out what thoughts led to that emotion. Rate how much you believe each thought on a scale from 0-100.

Rate how much you believe each thought on a scale from 0-100.

5. Complete one of these each day. At the end of the week, you might find that you have the ability to gain a little distance from your thoughts in the heat of the moment. That is metacognition in action!

Complete at least three or four of these thought records before moving on to the next module. As indicated above, it’s best if you can fill one out each day, as the next few chapters build on your ability to complete a thought record well.

CBT For Anxiety Disorders: A Practitioner Book. Wiley-Blackwell: Hoboken, New Jersey. – Simoris, G., Hofmann, S.G. (2013).

Cognitive Behavior Therapy, Second Edition: Basics and Beyond. The Guilford Press: New York. – Beck, J.S. (2011).

Cognitive therapy techniques: A practitioner's guide (2nd ed.). Guilford Press. Leahy, R. L. (2018).

Techniques and methods of cognitive psychotherapy: evalinger — LiveJournal

?- Medicine

- Lytdybr

- Cancel

Cognitive therapy in the vision of the Beaks, and this designed to help the patient master the following operations:

- Detect your negative automatic thoughts.

- Find the connection between knowledge, affects and behavior.

- Find facts for and against automatic thoughts.

- Look for more realistic interpretations for them.

- Learn to identify and change disruptive beliefs that distort skills and experience.

Methods for identifying and correcting automatic thoughts:

- Thought writing . The therapist can ask the patient to write down on paper what thoughts come into his head when he tries to do the right action (or not to do the unnecessary action).

It is advisable to write down thoughts that come to mind at the time of making a decision strictly in the order of their priority (this order is important because it will indicate the weight and importance of these motives in making a decision).

It is advisable to write down thoughts that come to mind at the time of making a decision strictly in the order of their priority (this order is important because it will indicate the weight and importance of these motives in making a decision).

- Thought diary . Many cognitive psychotherapists suggest that their patients briefly record their thoughts in a diary for several days in order to understand what the person thinks about most often, how much time they spend on it, and how strong emotions they experience from their thoughts [14]. For example, the American psychologist Matthew McKay recommended that his patients break a page in a diary into three columns, where you need to briefly indicate the thought itself, the hours of time spent on it and the assessment of your emotions on a 100-point scale in the range between: “very pleasant / interesting” - “ indifferent” — “very unpleasant/depressing”[14]. The value of such a diary is also in the fact that sometimes even the patient himself cannot always accurately indicate the reason for his experiences, in which case the diary helps both him and his therapist to find out what thoughts affect his well-being during the day.

nine0014

nine0014 - Distance . The essence of this stage is that the patient must take an objective position in relation to his own thoughts, that is, move away from them. Suspension has 3 components:

- awareness of the automaticity of a “bad” thought, its spontaneous nature, the understanding that this scheme arose earlier under other circumstances or was imposed by other people from the outside;

- the realization that a "bad" thought is maladaptive, that is, it causes suffering, fear, or frustration; nine0014

- the emergence of doubts about the truth of this maladaptive thought, the understanding that this scheme does not correspond to new requirements or a new situation (for example, the thought “To be happy means to be the first in everything”, formed by an excellent student at school, can lead to disappointment if he failed to become the first in the university).

- Empirical verification (“experiments”).

Ways:

Ways: - Find arguments for and against automatic thoughts. It is also advisable to put these arguments on paper so that the patient can re-read it whenever these thoughts come to him again. If a person does this often, then gradually the brain will remember the “correct” arguments and remove “wrong” motives and decisions from quick memory. At the same time, it is very important that the patient really agrees with the proposed arguments and does not experience internal objections or a feeling of contradiction with his past experience. To do this, the therapist must motivate the patient to communicate his objections and feelings to him, to give them significant importance, to discuss and solve problems together. nine0014

- Weigh the advantages and disadvantages of each option. It is also necessary to take into account the long-term perspective, and not just the immediate benefit (for example, in the long term, problems from drugs will many times exceed temporary pleasure).

- Construction of an experiment to test judgment.

- Conversation with witnesses of past events. This is especially true in those mental disorders where memory is sometimes distorted and replaced by fantasies (for example, in schizophrenia), or if the delusion is caused by a misinterpretation of the motives of another person. nine0014

- The therapist refers to his experience, to fiction and academic literature, statistics.

- Therapist incriminates: indicates logical errors and inconsistencies in the patient's judgments.

- Revaluation methodology . Checking the likelihood of alternative causes of an event.

- Decentration . With social phobia, patients feel in the center of everyone's attention and suffer from this. Here, too, an empirical test of these automatic thoughts is needed. nine0014

- Decay . For anxiety disorders. Therapist: “Let's see what would happen if…”, “How long will you experience such negative feelings?”, “What will happen next? You will die? Will the world collapse? Will it ruin your career? Will your loved ones abandon you?" etc.

The patient understands that everything has a time frame, and the automatic thought “this horror will never end” disappears.

The patient understands that everything has a time frame, and the automatic thought “this horror will never end” disappears. - Purposeful repetition . Re-enactment of the desired behavior, repeated testing of various positive instructions in practice, which leads to increased self-efficacy. Sometimes the patient quite agrees with the correct arguments during psychotherapy, but quickly forgets them after the session and returns to the previous "wrong" arguments, because they are repeatedly recorded in his memory, although he understands their illogicality. In this case, it is better to write down the correct arguments on paper and reread them regularly. At the same time, it is necessary to ensure that repetitions each time evoke positive thoughts and feelings in the patient, so that there are no contradictions on a conscious or subconscious (non-verbal) level, so that such contradictions do not cause unwanted feelings. Otherwise, the repetition of unconvincing arguments will lead to the repetition of conflicting thoughts and emotions in the mind of the patient, which may increase the connection with counterarguments and unwanted feelings, and repetitions in this case will only lead to the opposite result.

nine0014

nine0014 - Using the imagination . Anxious patients are dominated not so much by "automatic thoughts" as by "obsessive images", that is, it is rather not thinking that maladjusts, but imagination (fantasy). Kinds:

- Termination technique: loud command to yourself “stop!” The negative way of thinking or imagining stops. It has also been effective in stopping intrusive thoughts in some mental illnesses.

- Repetition technique: repeat the correct way of thinking several times in order to break the formed stereotype. nine0014

- Metaphors, parables, verses: The therapist uses such examples to make the explanation clearer.

- Modifying imagination: the patient actively and gradually changes the image from negative to more neutral and even positive, thereby understanding the possibilities of his self-awareness and conscious control. Usually, even after a bad setback, you can find at least something positive in what happened (for example, “I learned a good lesson”) and concentrate on it.

nine0023 Positive imagination: a positive image replaces a negative one and has a relaxing effect.

nine0023 Positive imagination: a positive image replaces a negative one and has a relaxing effect.

- Constructive imagination (desensitization): the patient ranks the probability of the expected event, which leads to the fact that the forecast loses its globality and inevitability.

- Emotion replacement . Sometimes the patient should come to terms with his past negative experience and change his emotions to more adequate ones. For example, it may sometimes be better for a victim of a crime not to replay the details of what happened in her memory, but to say to herself: “It’s very unfortunate that this happened to me, but I will not let my abusers ruin the rest of my life for me, I will live in the present and the future, rather than constantly looking back at the past. You should replace the emotions of resentment, anger and hatred with softer and more adequate ones that will allow you to build your future life more comfortably.

nine0014

nine0014 - Change of roles . Ask the patient to imagine that he is trying to console a friend who finds himself in a similar situation. What could be said to him? What to advise? What advice would your loved one give you in this situation?

- Revaluation of values . Often the cause of depression is unfulfilled desires or excessively high demands. In this case, the therapist can help the patient weigh the cost of achieving the goal and the cost of the problem and decide whether it is worth fighting further or whether it would be wiser to refuse to achieve this goal altogether, discard an unfulfilled desire, postpone, reduce requests, set more realistic goals for oneself to begin with, try more comfortable with what you have or find something to replace it. This is relevant in cases where the cost of solving the problem is higher than the suffering from the problem itself. However, in other cases, it may be better to work hard and solve the problem, especially if delaying the decision only aggravates the situation and causes more suffering for the person.

nine0014

nine0014 - Postponement . If the patient is not able to give up his unrealistic goals and desires, but thoughts about them uselessly waste his time and cause him problems, then you can suggest the patient to postpone these goals and thoughts about them for a long time until the occurrence of any event that will make him today's impossible dream more achievable. For example, if a patient has some kind of pseudo-inventive idea, but cannot implement it today and does not want to give it up for anything, but only wastes time and effort, then you can try to suggest that he at least postpone the implementation and consideration of this idea until retirement age, when he will have more free time and money. This "postponement" can then greatly soften the blow of realizing the unreality of his pseudo-invention. nine0014

- Action plan for the future . The patient and therapist jointly develop for the patient a realistic "action plan" for the future with specific conditions, actions and deadlines, write down this plan on paper.

For example, if a catastrophic event occurs, the patient will perform a certain sequence of actions at the time designated for this, and before this event occurs, the patient will not torment himself with needless experiences.

For example, if a catastrophic event occurs, the patient will perform a certain sequence of actions at the time designated for this, and before this event occurs, the patient will not torment himself with needless experiences. - Identification of alternative causes of behavior . If all the “correct” arguments are stated and the patient agrees with them, but continues to think or act in a clearly illogical way, then alternative reasons for such behavior should be sought, which the patient himself is unaware of or prefers to remain silent. For example, with obsessive thoughts, the process of deliberation itself often brings a person great satisfaction and relief, since it allows him to at least mentally imagine himself a “hero” or “savior”, solve all problems in fantasies, punish enemies in dreams, correct his mistakes in a fictional world, etc. Therefore, a person replays such thoughts again and again not for the sake of a real solution, but for the very process of thinking and satisfaction, gradually this process drags a person deeper and deeper, like a kind of drug, even though a person understands the unreality and illogicality of such thinking.

nine0014

nine0014 - Mental illness . In particularly severe cases, irrational and illogical behavior may be a sign of a serious undiagnosed mental illness (for example, obsessive-compulsive disorder or schizophrenia), then psychotherapy alone may not be enough, and the intervention of a psychiatrist is required.

Source: Internet

Example: livejournal No such user User title (optional)

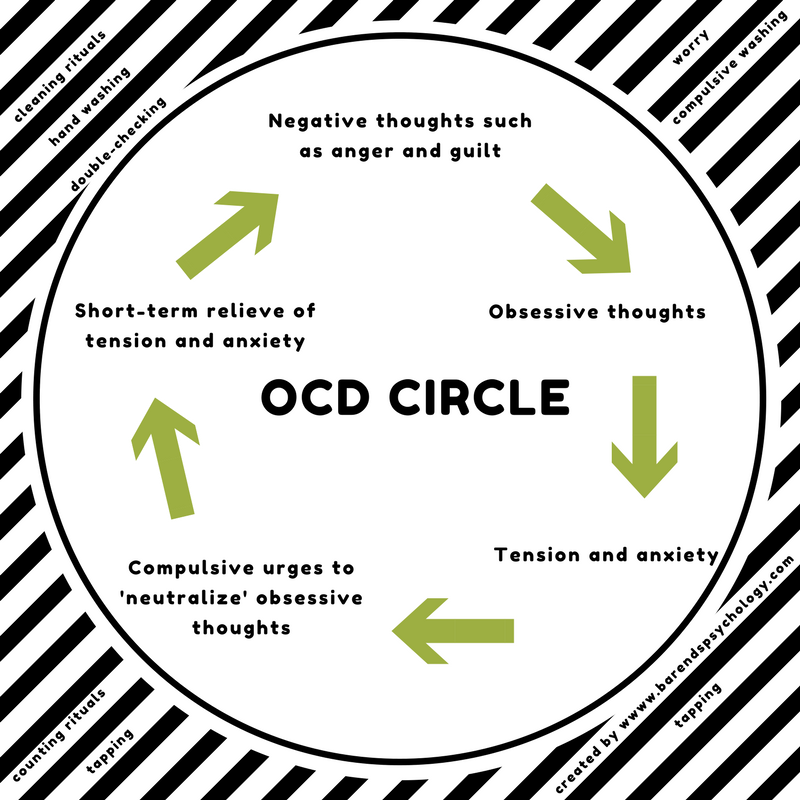

Obsessions - how it works and principles of self-help

Obsessive thoughts - how it works and principles of self-help

What supports obsessive thoughts/images?

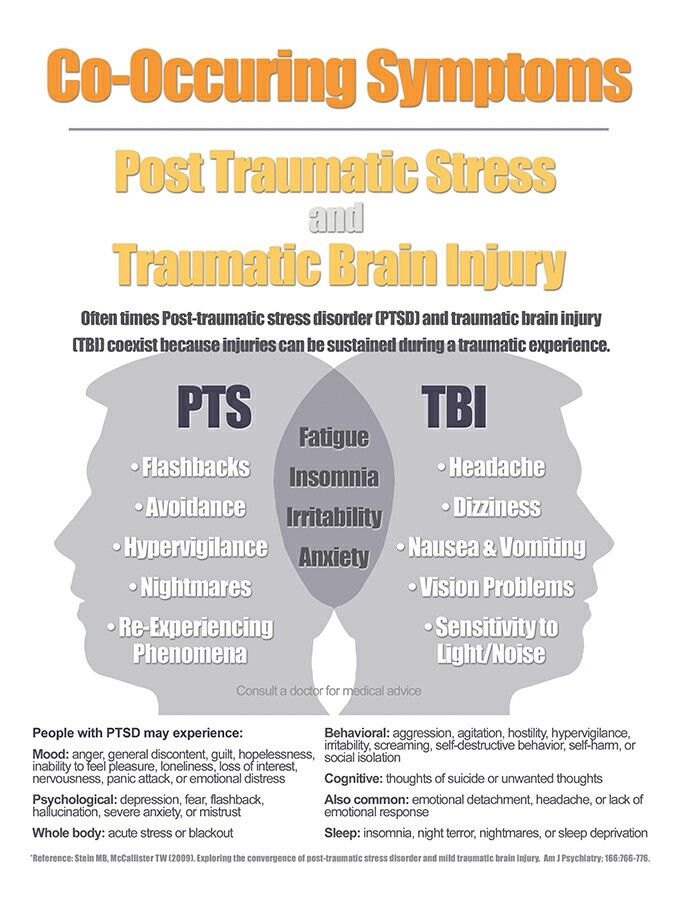

- Traumatic experience (accident, death/injury of a person, participation in hostilities, other events that caused strong emotional experiences, usually negative). Otherwise, such a phenomenon is called psychopathological re-experiencing, or flashback. A bit of a separate topic, because.

can occur in any person not because of his personal qualities, inclinations, response characteristics that predispose him to the emergence of stable obsessive thoughts, but because of the severity of the experience. Such phenomena can often pass quickly enough with the use of certain psychotherapeutic techniques, for example, EMDH. nine0014

can occur in any person not because of his personal qualities, inclinations, response characteristics that predispose him to the emergence of stable obsessive thoughts, but because of the severity of the experience. Such phenomena can often pass quickly enough with the use of certain psychotherapeutic techniques, for example, EMDH. nine0014 - Excessive control, the desire to control what is impossible to control. During a boring conversation, the mind of any person begins to wander. Just because you can think purposefully doesn't mean you can control your thinking. There are thoughts of insight, and there are uncontrollable thoughts of the opposite plan that are unpleasant to us, frighten us, cause horror, disgust, shame, etc. It's like trying to control dreams - just let them dream. And if such thoughts are comparable for you to nightmares from which you wake up in a sweat, then, of course, it is simply impossible not to do anything, however, fighting them with direct confrontation is the same as cutting off the heads of the Lernean Hydra (the mythical many-headed hydra, - if you cut her head, then two new heads immediately grew in its place).

Because the more attention you give to such thoughts, the more meaningful they become. The more you try to control them and fight them, the more attention and importance you yourself give them. nine0014

Because the more attention you give to such thoughts, the more meaningful they become. The more you try to control them and fight them, the more attention and importance you yourself give them. nine0014 - Giving excessive attention and importance to these thoughts , which we have already touched on in the previous paragraph. They seem to become overvalued if you constantly fight them. But what if they are like horror and a nightmare? We will talk about this further.

- Fear that thoughts can become actions. The logic is this: if my thoughts do not obey me, then where is the guarantee that my actions will not become uncontrolled? In fact, it rather depends on the innate temperament - the type of reaction of the nervous system. There are people with predominant impulsiveness - they first react, act, and then cognitive processing takes place, then thoughts. And there are people who will think everything over, sometimes it’s too late to do it, but they thought everything through.

And it's like two separate railway tracks, which are laid in such a way that one does not pass into the other. If you think obsessive thoughts while others act impulsively, then you can not disturb yourself in vain: it is as if you are walking on a different railway track, you have a different type of response of the nervous system. (In obsessive-compulsive disorder, both obsessive thoughts and compulsive actions occur, but actions are performed to prove that obsessive thoughts are erroneous, far-fetched, they are not actions confirming these thoughts and arise as an apotheosis of direct opposition to obsessive thoughts. For example, a person who has obsessive thoughts about a fire in the house because the iron is not turned off, can check several times before leaving and after leaving the house whether the iron is plugged in. He will not impulsively start a fire in the house, which obsessive thoughts scare him, but will do the opposite). You decide what actions to take, guided by your own will, mood, personal preferences, and also depending on your personality type.

And it's like two separate railway tracks, which are laid in such a way that one does not pass into the other. If you think obsessive thoughts while others act impulsively, then you can not disturb yourself in vain: it is as if you are walking on a different railway track, you have a different type of response of the nervous system. (In obsessive-compulsive disorder, both obsessive thoughts and compulsive actions occur, but actions are performed to prove that obsessive thoughts are erroneous, far-fetched, they are not actions confirming these thoughts and arise as an apotheosis of direct opposition to obsessive thoughts. For example, a person who has obsessive thoughts about a fire in the house because the iron is not turned off, can check several times before leaving and after leaving the house whether the iron is plugged in. He will not impulsively start a fire in the house, which obsessive thoughts scare him, but will do the opposite). You decide what actions to take, guided by your own will, mood, personal preferences, and also depending on your personality type. And if you have all this, then where will it disappear, and what kind of cow can lick all these characteristics of yours with its tongue so that they don’t remain, and you begin to be guided by behavior incomprehensibly by what? You just struggle with obsessive thoughts, and they fight back - they scare you, including impossible things. Well, how impossible - very unlikely. This can happen in acute psychosis, when consciousness, perception, often memory become clouded, then the behavior behind them all becomes inadequate, but these are rare phenomena and are in no way associated with obsessive thoughts, they can rather be associated with a long history of alcohol, with schizophrenia , dementia, etc. nine0014

And if you have all this, then where will it disappear, and what kind of cow can lick all these characteristics of yours with its tongue so that they don’t remain, and you begin to be guided by behavior incomprehensibly by what? You just struggle with obsessive thoughts, and they fight back - they scare you, including impossible things. Well, how impossible - very unlikely. This can happen in acute psychosis, when consciousness, perception, often memory become clouded, then the behavior behind them all becomes inadequate, but these are rare phenomena and are in no way associated with obsessive thoughts, they can rather be associated with a long history of alcohol, with schizophrenia , dementia, etc. nine0014 - Self-flagellation about the fact that "others would not have thought of it", a judgment that thoughts allegedly speak about a person's character or about his intentions. Character is shown in the way you lead your life. It is about what you decide to do or not do.

Thoughts are just flashes in your mind. It is not you who decides whether thoughts arise or not. Your character is not shown in any way if there is no place for making a decision. A thought is not a fact or a statement about you as a person. Character is the decisions you make in life, not something that randomly pops into your mind. nine0014

Thoughts are just flashes in your mind. It is not you who decides whether thoughts arise or not. Your character is not shown in any way if there is no place for making a decision. A thought is not a fact or a statement about you as a person. Character is the decisions you make in life, not something that randomly pops into your mind. nine0014 - The belief that the more you think about something, the more likely it is to happen. The belief that thoughts are material. Here, certain features of perception play against a person. It is more true, I think, to say that the more you think about something, the more likely you are to notice and remember that it happened. And if the way we think does not happen, then our psyche tends to forget it as a failure, as a mismatch, as a failed connection (the synthesis of the two parts failed), as something unimportant. The brain analyzes and synthesizes, this is its job. What has not succumbed to synthesis does not deserve special attention.

Therefore, we tend to remember those moments when our thoughts became reality, and many thoughts that cannot be connected with reality simply go unnoticed and unappreciated, and can emerge even after a long time if the brain finds for one of such old, abandoned thoughts communication in the real world. Therefore, people tend to remember those few forebodings that were justified (because they had personal significance), forgetting about the numerous cases when all doubts and fears were not justified in any way by subsequent events. Thoughts themselves are often based on guesses about the world around us and how it works, on our previous personal experience, etc. Thoughts rather influence whether we will try to do something, whether we will be afraid of what something to do, etc. They affect our attitude towards reality and our response rather than changes in reality per se. nine0014

Therefore, we tend to remember those moments when our thoughts became reality, and many thoughts that cannot be connected with reality simply go unnoticed and unappreciated, and can emerge even after a long time if the brain finds for one of such old, abandoned thoughts communication in the real world. Therefore, people tend to remember those few forebodings that were justified (because they had personal significance), forgetting about the numerous cases when all doubts and fears were not justified in any way by subsequent events. Thoughts themselves are often based on guesses about the world around us and how it works, on our previous personal experience, etc. Thoughts rather influence whether we will try to do something, whether we will be afraid of what something to do, etc. They affect our attitude towards reality and our response rather than changes in reality per se. nine0014 - The conviction that every thought is worthy of attention, and that repeated thoughts are of particular importance.

Our consciousness and brain function in general can be compared to cable television. And sometimes our attention to our inner world can for a moment switch to one of the unnecessary, uninteresting, not characteristic of us or even alien to us channels - this moment can become an obsessive thought if we give it significance and start fighting it. Especially if you also believe that all thoughts are worth paying attention to, and that there are no and should not be useless channels in the mind. Then your attention may be absorbed by meaningless nonsense. If you begin to act impartially towards such useless thoughts, and not fight them just because they are, and if in the end you admit that they have no meaning, then in time they will simply disappear. nine0014

Our consciousness and brain function in general can be compared to cable television. And sometimes our attention to our inner world can for a moment switch to one of the unnecessary, uninteresting, not characteristic of us or even alien to us channels - this moment can become an obsessive thought if we give it significance and start fighting it. Especially if you also believe that all thoughts are worth paying attention to, and that there are no and should not be useless channels in the mind. Then your attention may be absorbed by meaningless nonsense. If you begin to act impartially towards such useless thoughts, and not fight them just because they are, and if in the end you admit that they have no meaning, then in time they will simply disappear. nine0014

Regarding the greater importance of repetitive thoughts - we have already discussed this feature of perception, that thoughts are the more often repeated, the more importance we attach to them - both in a positive context (we think about something with interest), and in a negative one (obsessive thoughts ). However, in a positive context, we do not make a problem out of it, and in a negative one, we can make a big problem over time if we try. It is as if a whole searchlight is directed at this thought - as soon as its significance increases - if this thought is tacitly declared a problem. However, if the issue is already declared, i.e. in fact, you feel that this is a problem for you, then just saying that this is not a problem can be tantamount to a waste of time. We need consistent actions, an analysis of our feelings and experiences. nine0009

However, in a positive context, we do not make a problem out of it, and in a negative one, we can make a big problem over time if we try. It is as if a whole searchlight is directed at this thought - as soon as its significance increases - if this thought is tacitly declared a problem. However, if the issue is already declared, i.e. in fact, you feel that this is a problem for you, then just saying that this is not a problem can be tantamount to a waste of time. We need consistent actions, an analysis of our feelings and experiences. nine0009

- Strengthening the “importance of thought” on a sensory level. Here's how it works: When you're frightened or surprised or in danger, the area of the brain responsible for signaling alarms (amygdala/amygdala) sends signals of danger. In a stressful situation, the biological systems of the body are activated, supporting a clear strategy of behavior: “fight/flight/freeze”. Such a reaction occurs automatically, regardless of whether a false threat exists or a real one.

The amygdala is not "specially smart". And it can't tell a real threat from a false signal. She just reacts to the trigger - real/imaginary - in the only way she can. She sends out an alarm. If you are frightened by a thought, and the amygdala automatically gives out a signal of danger, then the emotional reaction will be the same as in real danger. Feelings in the body appear such that the thought may seem dangerous or very important. But neurons in the cerebral cortex analyze and are able to distinguish a real threat from an apparent one. The cortex is responsible for rational thinking and judgment. The problem is that the impulses from the higher brain arrive about half a second later than the first automatic alarm. Therefore, the feeling of danger arises before the cerebral cortex has the opportunity to intervene. And we tend to consider the first impulse to be true and true, so we can no longer listen to the second, devalue it, wind ourselves up and worsen our life out of the blue.

The amygdala is not "specially smart". And it can't tell a real threat from a false signal. She just reacts to the trigger - real/imaginary - in the only way she can. She sends out an alarm. If you are frightened by a thought, and the amygdala automatically gives out a signal of danger, then the emotional reaction will be the same as in real danger. Feelings in the body appear such that the thought may seem dangerous or very important. But neurons in the cerebral cortex analyze and are able to distinguish a real threat from an apparent one. The cortex is responsible for rational thinking and judgment. The problem is that the impulses from the higher brain arrive about half a second later than the first automatic alarm. Therefore, the feeling of danger arises before the cerebral cortex has the opportunity to intervene. And we tend to consider the first impulse to be true and true, so we can no longer listen to the second, devalue it, wind ourselves up and worsen our life out of the blue. nine0014

nine0014

For lovers of a deeper understanding of the work of the brain - a paragraph about the peculiarities of the response of the amygdala, which in general we have already discussed in the previous paragraph. The amygdala (tonsil) can only be in two states - active or passive. Since the purpose is to warn you, the amygdala is activated at the slightest hint of a possible threat. Her job is to protect you, not to take care of your comfort, so she would rather give a thousand false signals and cause as many panic attacks when there is no problem than miss even one real danger. Initially, it was supposed to provide primitive survival. She reacts very quickly, trying to protect you from any possible threat. The amygdala learns to be afraid: loud noises and loss of support are two innate fear triggers. Children begin to use protective behavior near a hot stove, a socket, a sharp knife much later. The amygdala in people with obsessive thoughts has learned to "ring the alarm bell" because of certain thoughts. Now imagine if someone came up behind you and scared you with a loud sound, the startle reaction starts instantly. But then, turning around and realizing that this is such a stupid joke and nothing terrible happened, your fear passes. In this example, I will talk about two neural pathways to the amygdala. Loud sound comes from the ear through different structures, transforming into nerve impulses. Reaching the thalamus (the "control panel" in the brain), they are sent to the amygdala (one way) and to the cortex, where the signal that something may be wrong is analyzed, compared with additional factors, and the result is also sent to the amygdala (one more way). This path is about half a second longer. This means that you get scared before you know the reason, and this is due to the neurophysiology of the brain. Your reaction in such a case is swift, automatic and unavoidable. The first fright passes quickly if the amygdala receives a message from the cerebral cortex that the trigger was not a threat.

Now imagine if someone came up behind you and scared you with a loud sound, the startle reaction starts instantly. But then, turning around and realizing that this is such a stupid joke and nothing terrible happened, your fear passes. In this example, I will talk about two neural pathways to the amygdala. Loud sound comes from the ear through different structures, transforming into nerve impulses. Reaching the thalamus (the "control panel" in the brain), they are sent to the amygdala (one way) and to the cortex, where the signal that something may be wrong is analyzed, compared with additional factors, and the result is also sent to the amygdala (one more way). This path is about half a second longer. This means that you get scared before you know the reason, and this is due to the neurophysiology of the brain. Your reaction in such a case is swift, automatic and unavoidable. The first fright passes quickly if the amygdala receives a message from the cerebral cortex that the trigger was not a threat. Assuming that the first fright attack is a reaction to the obsessive thought that you could jump off the balcony, then you might think: “Does this mean that I have suicidal tendencies that I did not know about?” or “How can you be sure it won’t happen?” etc. Thus, you would give a signal to the amygdala to continue to sound the alarm (to catch up with yourself a secondary fear, which can also increase the feeling of danger several times from the original). nine0009

Assuming that the first fright attack is a reaction to the obsessive thought that you could jump off the balcony, then you might think: “Does this mean that I have suicidal tendencies that I did not know about?” or “How can you be sure it won’t happen?” etc. Thus, you would give a signal to the amygdala to continue to sound the alarm (to catch up with yourself a secondary fear, which can also increase the feeling of danger several times from the original). nine0009

- Fixing unnecessary associative connections in the brain. Our thinking creates many associations: "up-down", "north-south", "more-less", etc. So in general, nerves that react simultaneously - as if soldered together, are associated with each other (the concept of conditioning). Overcoming intrusive thoughts involves creating new associations that eliminate fear.

Anxious thinking - a change in the state of consciousness when the amygdala is activated. Its characteristics:

- Merging thoughts and actions, imagination and experience of the situation.

Questions like “What if…?” no longer look like conjectures, but are perceived as a reliable vision of the future. Thoughts seem to be predictions. "Fear has big eyes".

Questions like “What if…?” no longer look like conjectures, but are perceived as a reliable vision of the future. Thoughts seem to be predictions. "Fear has big eyes". - All risks seem unreasonable. Anxious thinking requires absolute guarantees that the nightmares you may have thought will not happen. Everything else is cause for continued concern. Uncertainty is unbearable. nine0149 Any uncertainty is perceived as a threat. And to complete this picture of the post-apocalypse, it should be noted that the brain during anxious thinking is in a functional mode of increased sensitivity to the threat.

- Thoughts tend to become intrusive. They seem to get stuck in the mind.

Some Exercises

Now imagine opening the following email: “Congratulations! Your lucky day has come. Your distant relative, who headed the diamond corporation in Chicago, died, leaving you a legacy of 14 billion dollars. To receive the inheritance, please follow the link below and provide us with your bank details for money transfer. Once again, let me congratulate you from the bottom of my heart." nine0009

To receive the inheritance, please follow the link below and provide us with your bank details for money transfer. Once again, let me congratulate you from the bottom of my heart." nine0009

Will you send this letter to spam or will you study and think in detail about its content, why it was sent to you, why now, etc.? If you just spam it, then why don't you do the same with intrusive thoughts?

An exercise explaining the mechanism of engagement.

- Please answer how strong emotional connotation do the words “cut” and “transfer” have for you (from 1 to 10)?

- Delete the letters from each word so that "beat" and "betray" remain. How powerful are these words? nine0014

- Now go back to the words "cut" and "transfer". Has their emotional perception changed?

If it has changed in the direction of strengthening, then you have become emotionally involved, because the words have emotional associations with other words that you cannot yet ignore. These words may already seem negative, speaking of danger, unpleasant. But words are just words. They don't have any color until you start to interpret them, and then it becomes very easy to get involved in the process. nine0009

These words may already seem negative, speaking of danger, unpleasant. But words are just words. They don't have any color until you start to interpret them, and then it becomes very easy to get involved in the process. nine0009

Solving the problem

Alternative methods to what will be offered here can help someone, and someone can even get worse from them. For example, prayer can reduce anxiety, but it can also increase involvement in those intrusive thoughts that a person wants to forget. Yoga and meditation can be used by a person who is intrinsically motivated to reduce the tendency to get "stuck in the mind" and get involved in thoughts, or maybe motivated to learn to control thoughts. In the latter case, the condition is likely to worsen. nine0009

This article suggests the following: acceptance of these thoughts. One should actively allow thoughts to emerge, not wanting them to disappear, because. it helps to realize that they are not important. Concentrate not on the result of a false alarm given by an overly cautious amygdala, but on how your thoughts are not an alarm signal to the amygdala.

You should also practice allowing reasonable uncertainty in your life. Certainty is a feeling, not a fact. If you continue to reassure yourself, then you can never get used to the fact that there is uncertainty in life, and constantly worry about this. Try to focus on the present as well. if you think about the future, you think about more uncertainty than if you think about the present. Yet too much uncertainty is hardly a good atmosphere for the absence of anxiety. Therefore, accept the uncertainty that cannot be reduced in a natural way, and if the uncertainty can be reduced without sacrificing anything, then do it. For example, focus on the present rather than the future. What do you hear, what do you feel, is it cold now or hot? These are simple questions for yourself in a more definite present that is and exists. nine0009

Feeling the need to do something urgently (panic) when obsessive thoughts arise - also arises from an attempt to deal with uncertainty. Panic sensations indicate discomfort, not danger, and discomfort should be tolerated if it proves to the brain that this discomfort is not dangerous. Actively and in a panic try to do something - like putting out a fire, fanning the flame. It happens that passivity is much more effective than effort. It's like peeling off a crust from a wound - supposedly it will pass faster, heal faster. Sometimes you just need to understand how to wait for the right time so as not to interfere with natural processes to fade away on their own. nine0009

Actively and in a panic try to do something - like putting out a fire, fanning the flame. It happens that passivity is much more effective than effort. It's like peeling off a crust from a wound - supposedly it will pass faster, heal faster. Sometimes you just need to understand how to wait for the right time so as not to interfere with natural processes to fade away on their own. nine0009

False response of the brain makes one consider the thought dangerous and stay away from it, and in order to retrain the amygdala, one must evoke a reaction in it and then show that in this case there is no danger. So she will be retrained. And if you stay away from these thoughts, then they will be associated with danger, and with a decrease in cortical control (during stress, discomfort, in some situation reminiscent of these thoughts, etc.), they will be able to arise again and remind themselves through panic and a sense of danger that the amygdala will turn on. The amygdala learns not to be afraid only when the fear response is activated. To compromise and evoke in your mind not the most terrible thoughts of those that periodically torment you means forgetting that any thoughts are just thoughts. The best results come from regular practice in a variety of situations and conditions. nine0009

To compromise and evoke in your mind not the most terrible thoughts of those that periodically torment you means forgetting that any thoughts are just thoughts. The best results come from regular practice in a variety of situations and conditions. nine0009

Intrusive thoughts seem so frightening because the anxious type of thinking wins and the thought begins to look extremely plausible. You can compare the tormenting obsessive thoughts with a fairy-tale city, where the road of fear is the central one. If you use the method suggested here to dispel these intrusive thoughts, you can imagine that you are building a freeway next to the road of fear in this city. As a result, the built motorway will be used more and more often, because. this is energy-efficient (the brain exists according to the laws of conservation of energy, and if we offer a less energy-consuming option for solving a problem, in particular, dealing with obsessive thoughts, then this option is most likely to take root). But the path of fear has not disappeared either. Fear may arise even after many years, during times of stress or extreme fatigue, etc., but this does not mean that your achievements will be lost in an instant. The achievement is that the freeway is used much more often. This achievement is still with you, even if one or more cars drove along the old road. It is important to understand this in order not to destroy your own achievements, accepting for the truth that supposedly everything has returned to what it started. If you allow this fear into yourself, then this can indeed happen, but this can all become so only because you agreed with the amygdala's false signal of danger and also confirmed the almost emergency situation in the city with this thought that “everything comes back”, or “everything came back”, or “it didn’t work out for me again”, well, or “this method didn’t work either”. If you switch to the fact that nothing terrible has happened, these are just thoughts and you are able to endure these thoughts, then further on, based on its properties, the brain will continue to use and strengthen new mechanisms that are not associated with fear.

But the path of fear has not disappeared either. Fear may arise even after many years, during times of stress or extreme fatigue, etc., but this does not mean that your achievements will be lost in an instant. The achievement is that the freeway is used much more often. This achievement is still with you, even if one or more cars drove along the old road. It is important to understand this in order not to destroy your own achievements, accepting for the truth that supposedly everything has returned to what it started. If you allow this fear into yourself, then this can indeed happen, but this can all become so only because you agreed with the amygdala's false signal of danger and also confirmed the almost emergency situation in the city with this thought that “everything comes back”, or “everything came back”, or “it didn’t work out for me again”, well, or “this method didn’t work either”. If you switch to the fact that nothing terrible has happened, these are just thoughts and you are able to endure these thoughts, then further on, based on its properties, the brain will continue to use and strengthen new mechanisms that are not associated with fear. This will become possible because you will remove the imaginary danger mode, and the brain will no longer need to solve the primary task - to survive. nine0009

This will become possible because you will remove the imaginary danger mode, and the brain will no longer need to solve the primary task - to survive. nine0009

Here is an example of a possible internal dialogue: (after the dialogue, the division of the replicas into certain colors is deciphered, but I recommend that you just read first, then familiarize yourself with what the colors mean and read it again) *

- What if this does not work? What if I lose control of myself so much that I actually do what I fear?

- Don't be stupid, drop all these thoughts. This has happened so many times already, and not once did thoughts turn into actions. nine0009

- Please don't react to these thoughts. These are just thoughts.

- No, it will drive me crazy someday!

- You shouldn't even answer these thoughts.

- It really can happen, what will you do then?

- It's just an obsessive thought. Thought is just a thought.

- Oh, I might have a nervous breakdown right now from all this!

- However, I accept these thoughts and allow them to manifest. I have already tried other methods of struggle, you should not return to them. nine0009

I have already tried other methods of struggle, you should not return to them. nine0009

- WHAT IF I CAN'T CONTROL MYSELF?

- I know that some other obsessive thought may follow.

- I don't think I can take it anymore!

- Let the time pass.

- I'm so worried about all this. What if I never settle down?

- I relax and observe.

- What if I actually do it?

- It's not even worth answering this question.

- Not sure if I can control myself. nine0009

- I allow thoughts to manifest.

- (softly) This has been going on for so long. What if it never stops?

- I accept thoughts

- (even more subtly) I'm not sure I can control myself.

- You see, it works - so with these thoughts you need to keep it up.

(to “devalue” these obsessive thoughts to yourself, you can somehow ridicule them during such an internal dialogue, for example, sing obsessive thoughts to a certain motive of a song). nine0009