Night terrors ptsd treatment

Management of nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder: current perspectives

1. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2003. [Google Scholar]

2. Germain A. Sleep disturbances as the hallmark of PTSD: where are we now? Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(4):372–382. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Leskin GA, Woodward SH, Young HE, Sheikh JI. Effects of comorbid diagnoses on sleep disturbance in PTSD. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36(6):449–452. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Heim C, Nemeroff CB. Neurobiology of posttraumatic stress disorder. CNS Spectr. 2009;14(1 Suppl 1):13–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Davis JL, Byrd P, Rhudy JL, Wright DC. Characteristics of chronic nightmares in a trauma-exposed treatment-seeking sample. Dreaming. 2007;17(4):187–198. [Google Scholar]

6. Detweiler MB, Arif S, Candelario J, et al. Salem VAMC-U. S. Army fort Bragg warrior transition clinic telepsychiatry collaboration: 12-month operation clinical perspective. Telemed J E Health. 2012;18(2):81–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Davies J. Treating Post-trauma Nightmares: A Cognitive Behavioral Approach. New York: Springer; 2009. [Google Scholar]

8. Clum GA, Nishith P, Resick PA. Trauma-related sleep disturbance and self-reported physical health symptoms in treatment-seeking female rape victims. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2001;189(9):618–622. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Bryant RA, Creamer M, O’Donnell M, Silove D, McFarlane AC. Sleep disturbance immediately prior to trauma predicts subsequent psychiatric disorder. Sleep. 2010;33(1):69–74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. van Liempt S, van Zuiden M, Westenberg H, Super A, Vermetten E. Impact of impaired sleep on the development of PTSD symptoms in combat veterans: a prospective longitudinal cohort study. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30(5):469–474. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Kobayashi I, Sledjeski EM, Spoonster E, Fallon WF, Delahanty DL. Effects of early nightmares on the development of sleep disturbances in motor vehicle accident victims. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(6):548–555. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Spoormaker VI, Montgomery P. Disturbed sleep in post-traumatic stress disorder: secondary symptom or core feature? Sleep Med Rev. 2008;12(3):169–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Nadorff MR, Nazem S, Fiske A. Insomnia symptoms, nightmares, and suicide risk: duration of sleep disturbance matters. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2013;43(2):139–149. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Sjöström N, Hetta J, Waern M. Persistent nightmares are associated with repeat suicide attempt: a prospective study. Psychiatry Res. 2009;170(2–3):208–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Sjöström N, Waern M, Hetta J. Nightmares and sleep disturbances in relation to suicidality in suicide attempters. Sleep. 2007;30(1):91–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Panagioti M, Gooding PA, Tarrier N. A meta-analysis of the association between posttraumatic stress disorder and suicidality: the role of comorbid depression. Compr Psychiatry. 2012;53(7):915–930. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Sareen J, Houlahan T, Cox BJ, Asmundson GJ. Anxiety disorders associated with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in the National Comorbidity Survey. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(7):450–454. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Littlewood DL, Gooding PA, Panagioti M, Kyle SD. Nightmares and suicide in posttraumatic stress disorder: the mediating role of defeat, entrapment, and hopelessness. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(3):393–399. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Nadorff MR, Nadorff DK, Germain A. Nightmares: under-reported, undetected, and therefore untreated. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(7):747–750. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Simor P, Horváth K, Gombos F, Takács KP, Bódizs R. Disturbed dreaming and sleep quality: altered sleep architecture in subjects with frequent nightmares. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(8):687–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;262(8):687–696. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Phelps AJ, Kanaan RAA, Worsnop C, Redston S, Ralph N, Forbes D. An ambulatory polysomnography study of the post-traumatic nightmares of post-traumatic stress disorder. Sleep. 2018;41(1) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Tamanna S, Parker JD, Lyons J, Ullah MI. The effect of continuous positive air pressure (CPAP) on nightmares in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014;10(6):631–636. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Committee on the Assessment of Ongoing Effects in the Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder; Institute of Medicine . Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in Military and Veteran Populations. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2012. [Google Scholar]

24. Foa EB, Steketee G, Rothbaum BO. Behavioral/cognitive conceptualizations of post-traumatic stress disorder. Behav Ther. 1989;20:155–176. [Google Scholar]

1989;20:155–176. [Google Scholar]

25. Marks I. Rehearsal relief of a nightmare. Br J Psychiatry. 1978;133(5):461–465. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Krakow B, Zadra A. Clinical management of chronic nightmares: imagery rehearsal therapy. Behav Sleep Med. 2006;4(1):45–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Augedal AW, Hansen KS, Kronhaug CR, Harvey AG, Pallesen S. Randomized controlled trials of psychological and pharmacological treatments for nightmares: a meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2013;17(2):143–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Hansen K, Höfling V, Kröner-Borowik T, Stangier U, Steil R. Efficacy of psychological interventions aiming to reduce chronic nightmares: a meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2013;33(1):146–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Krakow B, Hollifield M, Johnston L, et al. Imagery rehearsal therapy for chronic nightmares in sexual assault survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2001;286(5):537–545. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Krakow B, Kellner R, Neidhardt J, Pathak D, Lambert L. Imagery rehearsal treatment of chronic nightmares: with a thirty month followup. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1993;24(4):325–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Thünker J, Pietrowsky R. Effectiveness of a manualized imagery rehearsal therapy for patients suffering from nightmare disorders with and without a comorbidity of depression or PTSD. Behav Res Ther. 2012;50(9):558–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Forbes D, Phelps AJ, McHugh AF, Debenham P, Hopwood M, Creamer M. Imagery rehearsal in the treatment of posttraumatic nightmares in Australian veterans with chronic combat-related PTSD: 12-month follow-up data. J Trauma Stress. 2003;16(5):509–513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Nappi CM, Drummond SP, Thorp SR, McQuaid JR. Effectiveness of imagery rehearsal therapy for the treatment of combat-related nightmares in veterans. Behav Ther. 2010;41(2):237–244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Cook JM, Harb GC, Gehrman PR, et al. Imagery rehearsal for post-traumatic nightmares: a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(5):553–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Cook JM, Harb GC, Gehrman PR, et al. Imagery rehearsal for post-traumatic nightmares: a randomized controlled trial. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(5):553–563. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Lu M, Wagner A, Van Male L, Whitehead A, Boehnlein J. Imagery rehearsal therapy for posttraumatic nightmares in U.S. veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2009;22(3):236–239. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Casement MD, Swanson LM. A meta-analysis of imagery rehearsal for post-trauma nightmares: effects on nightmare frequency, sleep quality, and posttraumatic stress. Clin Psychol Rev. 2012;32(6):566–574. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Harb GC, Phelps AJ, Forbes D, Ross RJ, Gehrman PR, Cook JM. A critical review of the evidence base of imagery rehearsal for post-traumatic nightmares: pointing the way for future research. J Trauma Stress. 2013;26(5):570–579. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Manber R, Carney C, Edinger J, et al. Dissemination of CBTI to the non-sleep specialist: protocol development and training issues. J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(2):209–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Sleep Med. 2012;8(2):209–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Zayfert C, Deviva JC. Residual insomnia following cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2004;17(1):69–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Davis JL, Wright DC. Exposure, relaxation, and rescripting treatment for trauma-related nighmares. J Trauma Dissociation. 2006;7(1):5–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Davis JL, Wright DC. Randomized clinical trial for treatment of chronic nightmares in trauma-exposed adults. J Trauma Stress. 2007;20(2):123–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Davis JL, Rhudy JL, Pruiksma KE, et al. Physiological predictors of response to exposure, relaxation, and rescripting therapy for chronic nightmares in a randomized clinical trial. J Clin Sleep Med. 2011;7(6):622–631. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Balliett NE, Davis JL, Miller KE. Efficacy of a brief treatment for nightmares and sleep disturbances for veterans. Psychol Trauma. 2015;7(6):507–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2015;7(6):507–515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Ho FY, Chan CS, Tang KN. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for sleep disturbances in treating posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:90–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Rhudy JL, Davis JL, Williams AE, et al. Cognitive-behavioral treatment for chronic nightmares in trauma-exposed persons: assessing physiological reactions to nightmare-related fear. J Clin Psychol. 2010;66(4):365–382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Pruiksma KE, Cranston CC, Rhudy JL, Micol RL, Davis JL. Randomized controlled trial to dismantle exposure, relaxation, and rescripting therapy (ERRT) for trauma-related nightmares. Psychol Trauma. 2018;10(1):67–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Wolpe J. Behavioral Therapy Techniques. New York: Pergamon Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

48. Cellucci AJ, Lawrence PS. The efficacy of systematic desensi-tization in reducing nightmares. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1978;9(2):109–114. [Google Scholar]

J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1978;9(2):109–114. [Google Scholar]

49. Kellner R, Neidhardt J, Krakow B, Pathak D. Changes in chronic nightmares after one session of desensitization or rehearsal instructions. Am J Psychiatry. 1992;149(5):659–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Miller WR, Dipilato M. Treatment of nightmares via relaxation and desensitization: a controlled evaluation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1983;51(6):870–877. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Shapiro F. Eye movement desensitization: a new treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1989;20(3):211–217. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Wilson DL, Silver SM, Covi WG, Foster S. Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: effectiveness and autonomic correlates. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1996;27(3):219–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Cusack K, Jonas DE, Forneris CA, et al. Psychological treatments for adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:128–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clin Psychol Rev. 2016;43:128–141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Silver SM, Brooks A, Obenchain J. Treatment of Vietnam War veterans with PTSD: a comparison of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing, biofeedback, and relaxation training. J Trauma Stress. 1995;8(2):337–342. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Van Eeden F. A study of dreams. PSPR. 1913;26:431–461. [Google Scholar]

56. Harb GC, Greene JL, Dent KM, Ross RJ. 1077 Lucid dreaming in veterans with PTSD: non-nightmare dreams and nightmares. Sleep. 2017;40(suppl_1):A401. [Google Scholar]

57. Dudai Y. The neurobiology of consolidations, or, how stable is the engram? Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55(1):51–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Dębiec J, Bush DE, Ledoux JE. Noradrenergic enhancement of reconsolidation in the amygdala impairs extinction of conditioned fear in rats – a possible mechanism for the persistence of traumatic memories in PTSD. Depress Anxiety. 2011;28(3):186–193. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Gazarini L, Stern CA, Carobrez AP, Bertoglio LJ. Enhanced noradrenergic activity potentiates fear memory consolidation and reconsolidation by differentially recruiting α1- and β-adrenergic receptors. Learn Mem. 2013;20(4):210–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Gazarini L, Stern CA, Carobrez AP, Bertoglio LJ. Enhanced noradrenergic activity potentiates fear memory consolidation and reconsolidation by differentially recruiting α1- and β-adrenergic receptors. Learn Mem. 2013;20(4):210–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Raskind MA, Dobie DJ, Kanter ED, Petrie EC, Thompson CE, Peskind ER. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin ameliorates combat trauma nightmares in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder: a report of 4 cases. J Clin Psychiatry. 2000;61(2):129–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Raskind MA, Thompson C, Petrie EC, et al. Prazosin reduces nightmares in combat veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63(7):565–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Taylor F, Raskind MA. The alpha1-adrenergic antagonist prazosin improves sleep and nightmares in civilian trauma posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;22(1):82–85. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Raskind MA, Peterson K, Williams T, et al. A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A trial of prazosin for combat trauma PTSD with nightmares in active-duty soldiers returned from Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170(9):1003–1010. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

64. Germain A, Richardson R, Moul DE, et al. Placebo-controlled comparison of prazosin and cognitive-behavioral treatments for sleep disturbances in US Military Veterans. J Psychosom Res. 2012;72(2):89–96. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

65. Khachatryan D, Groll D, Booij L, Sepehry AA, Schütz CG. Prazosin for treating sleep disturbances in adults with posttraumatic stress disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2016;39:46–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

66. Raskind MA, Peskind ER, Chow B, et al. Trial of prazosin for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(6):507–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Koola MM, Varghese SP, Fawcett JA. High-dose prazosin for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):43–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2014;4(1):43–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Morgenthaler TI, Auerbach S, Casey KR, et al. Position paper for the treatment of nightmare disorder in adults: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine position paper. J Clin Sleep Med. 2018;14(6):1041–1055. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Nirmalani-Gandhy A, Sanchez D, Catalano G. Terazosin for the treatment of trauma-related nightmares: a report of 4 cases. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2015;38(3):109–111. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Salviati M, Pallagrosi M, Valeriani G, Carlone C, Todini L, Biondi M. On the role of noradrenergic system in PTSD and related sleep disturbances. The use of terazosin in PTSD related nightmares: a case report. Clin Ter. 2013;164(2):133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Detweiler M, Pagadala B, Candelario J, Boyle J, Detweiler J, Lutgens B. Treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder nightmares at a veterans affairs medical center. J Clin Med. 2016;5(12):117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2016;5(12):117. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Sethi R, Vasudeva S. Doxazosin for the treatment of nightmares: does it really work? A case report. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2012;14(5) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Roepke S, Danker-Hopfe H, Repantis D, et al. Doxazosin, an alpha-1-adrenergic-receptor antagonist, for nightmares in patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and/or borderline personality disorder: a chart review. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2017;50(1):26–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Alao A, Selvarajah J, Razi S. The use of clonidine in the treatment of nightmares among patients with co-morbid PTSD and traumatic brain injury. Int J Psychiatry Med. 2012;44(2):165–169. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Kinzie JD, Leung P. Clonidine in Cambodian patients with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 1989;177(9):546–550. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Boehnlein JK, Kinzie JD, Sekiya U, Riley C, Pou K, Rosborough B. A ten-year treatment outcome study of traumatized cambodian refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192(10):658–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A ten-year treatment outcome study of traumatized cambodian refugees. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192(10):658–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Wendell K, Maxwell M. Evaluation of clonidine and prazosin for the treatment of nightime post traumatic stres disorder symptoms. Fed Pract. 2015:8–14. [Google Scholar]

78. Graham RL, Leckband S, Endow-Eyer R. PTSD nightmares: prazosin and atypical antipsychotics. Curr Psychiatr. 2012;11:59–62. [Google Scholar]

79. Schotte A, Janssen PF, Gommeren W, et al. Risperidone compared with new and reference antipsychotic drugs: in vitro and in vivo receptor binding. Psychopharmacology. 1996;124(1–2):57–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Richelson E. Receptor pharmacology of neuroleptics: relation to clinical effects. J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;60(Suppl 10):5–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. David D, De Faria L, Mellman TA. Adjunctive risperidone treatment and sleep symptoms in combat veterans with chronic PTSD. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23(8):489–491. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Stanovic JK, James KA, Vandevere CA. The effectiveness of risperidone on acute stress symptoms in adult burn patients: a preliminary retrospective pilot study. J Burn Care Rehabil. 2001;22(3):210–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Khachiyants N, Ali R, Kovesdy CP, Detweiler JG, Kim KY, Detweiler MB. Effectiveness of risperidone for the treatment of nightmares in veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(6):735–737. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Jakovljević M, Sagud M, Mihaljević-Peles A. Olanzapine in the treatment-resistant, combat-related PTSD--a series of case reports. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107(5):394–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Stein MB, Kline NA, Matloff JL. Adjunctive olanzapine for SSRI-resistant combat-related PTSD: a double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(10):1777–1779. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Butterfield MI, Becker ME, Connor KM, Sutherland S, Churchill LE, Davidson JRT. Olanzapine in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(4):197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Olanzapine in the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder: a pilot study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(4):197–203. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Deng C, Weston-Green K, Huang XF. The role of histaminergic h2 and h4 receptors in food intake: a mechanism for atypical antipsychotic-induced weight gain? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34(1):1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Weston-Green K, Huang XF, Deng C. Alterations to melanocortinergic, GABAergic and cannabinoid neurotransmission associated with olanzapine-induced weight gain. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e33548. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

89. Robert S, Hamner MB, Kose S, Ulmer HG, Deitsch SE, Lorberbaum JP. Quetiapine improves sleep disturbances in combat veterans with PTSD: sleep data from a prospective, open-label study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;25(4):387–388. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

90. Britnell SR, Jackson AD, Brown JN, Capehart BP. Aripiprazole for post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2017;40(6):273–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Clin Neuropharmacol. 2017;40(6):273–278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

91. Lambert MT. Aripiprazole in the management of post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms in returning Global War on Terrorism veterans. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;21(3):185–187. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

92. Dillard ML, Bendfeldt F, Jernigan P. Use of thioridazine in post-traumatic stress disorder. South Med J. 1993;86(11):1276–1278. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

93. De Boer M, Op den Velde W, Falger PJ, Hovens JE, de Groen JH, van Duijn H. Fluvoxamine treatment for chronic PTSD: a pilot study. Psychother Psychosom. 1992;57(4):158–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

94. Neylan TC, Metzler TJ, Schoenfeld FB, et al. Fluvoxamine and sleep disturbances in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14(3):461–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

95. Lepkifker E, Dannon PN, Iancu I, Ziv R, Kotler M. Nightmares related to fluoxetine treatment. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1995;18(1):90–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

96. Arora G, Sandhu G, Fleser C. Citalopram and nightmares. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(2):E43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arora G, Sandhu G, Fleser C. Citalopram and nightmares. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2012;24(2):E43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

97. Lewis JD. Mirtazapine for PTSD nightmares. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(11):1948–1949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

98. Mathews M, Basil B, Evcimen H, Adetunji B, Joseph S. Mirtazapine-induced nightmares. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;8(5):311. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

99. Menon V, Madhavapuri P. Low-Dose mirtazapine-induced nightmares necessitating its discontinuation in a young adult female. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2017;8(4):182–184. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

100. Rottach KG, Schaner BM, Kirch MH, et al. Restless legs syndrome as side effect of second generation antidepressants. J Psychiatr Res. 2008;43(1):70–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

101. Neylan TC, Lenoci M, Maglione ML, et al. The effect of nefazodone on subjective and objective sleep quality in posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(4):445–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(4):445–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

102. Davidson JR, Weisler RH, Malik ML, Connor KM. Treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder with nefazodone. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1998;13(3):111–114. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

103. Boehnlein JK, Kinzie JD, Ben R, Fleck J. One-year follow-up study of posttraumatic stress disorder among survivors of Cambodian concentration camps. Am J Psychiatry. 1985;142(8):956–959. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

104. Warner MD, Dorn MR, Peabody CA. Survey on the usefulness of trazodone in patients with PTSD with insomnia or nightmares. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2001;34(4):128–131. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

105. Harsch HH. Cyproheptadine for recurrent nightmares. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(11):1491–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

106. Brophy MH. Cyproheptadine for combat nightmares in post-traumatic stress disorder and dream anxiety disorder. Mil Med. 1991;156(2):100–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

107. Gupta S, Popli A, Bathurst E, Hennig L, Droney T, Keller P. Efficacy of cyproheptadine for nightmares associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(3):160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Efficacy of cyproheptadine for nightmares associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. Compr Psychiatry. 1998;39(3):160–164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

108. Clark RD, Canive JM, Calais LA, Qualls C, Brugger RD, Vosburgh TB. Cyproheptadine treatment of nightmares associated with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;19(5):486–487. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

109. Abrams TE, Lund BC, Bernardy NC, Friedman MJ. Aligning clinical practice to PTSD treatment guidelines: medication prescribing by provider type. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(2):142–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

110. Greenbaum MA, Neylan TC, Rosen CS. Symptom presentation and prescription of sleep medications for veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205(2):1–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

111. Guina J, Rossetter SR, Derhodes BJ, Nahhas RW, Welton RS. Benzodiazepines for PTSD: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21(4):281–303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

112. Braun P, Greenberg D, Dasberg H, Lerer B. Core symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder unimproved by alprazolam treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51(6):236–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Braun P, Greenberg D, Dasberg H, Lerer B. Core symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder unimproved by alprazolam treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 1990;51(6):236–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

113. Cates ME, Bishop MH, Davis LL, Lowe JS, Woolley TW. Clonazepam for treatment of sleep disturbances associated with combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. Ann Pharmacother. 2004;38(9):1395–1399. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

114. Abramowitz EG, Barak Y, Ben-Avi I, Knobler HY. Hypnotherapy in the treatment of chronic combat-related PTSD patients suffering from insomnia: a randomized, zolpidem-controlled clinical trial. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2008;56(3):270–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

115. Passie T, Emrich HM, Karst M, Brandt SD, Halpern JH. Mitigation of post-traumatic stress symptoms by Cannabis resin: a review of the clinical and neurobiological evidence. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4(7–8):649–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

116. Greer GR, Grob CS, Halberstadt AL. PTSD symptom reports of patients evaluated for the New Mexico Medical Cannabis Program. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46(1):73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Psychoactive Drugs. 2014;46(1):73–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

117. Zuardi AW. Cannabidiol: from an inactive cannabinoid to a drug with wide spectrum of action. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2008;30(3):271–280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

118. Fraser GA. The use of a synthetic cannabinoid in the management of treatment-resistant nightmares in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) CNS Neurosci Ther. 2009;15(1):84–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

119. Jetly R, Heber A, Fraser G, Boisvert D. The efficacy of nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, in the treatment of PTSD-associated nightmares: a preliminary randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over design study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:585–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

120. Jinwala FN, Gupta M. Synthetic cannabis and respiratory depression. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(6):459–462. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

121. Sweeney B, Talebi S, Toro D, et al. Hyperthermia and severe rhabdomyolysis from synthetic cannabinoids. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(1):121.e1–121.e2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34(1):121.e1–121.e2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

122. Takematsu M, Hoffman RS, Nelson LS, Schechter JM, Moran JH, Wiener SW. A case of acute cerebral ischemia following inhalation of a synthetic cannabinoid. Clin Toxicol. 2014;52(9):973–975. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

123. Lapoint J, James LP, Moran CL, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS, Moran JH. Severe toxicity following synthetic cannabinoid ingestion. Clin Toxicol. 2011;49(8):760–764. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

124. MacFarlane V, Christie G. Synthetic cannabinoid withdrawal: a new demand on detoxification services. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2015;34(2):147–153. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

125. Rodgman CJ, Verrico CD, Worthy RB, Lewis EE. Inpatient detoxification from a synthetic cannabinoid and control of postdetoxification cravings with naltrexone. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2014;16(4) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

126. Degenhardt L, Hall W. Is cannabis use a contributory cause of psychosis? Can J Psychiatry. 2006;51(9):556–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2006;51(9):556–565. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Treating PTSD Night Terrors - Psy Visions

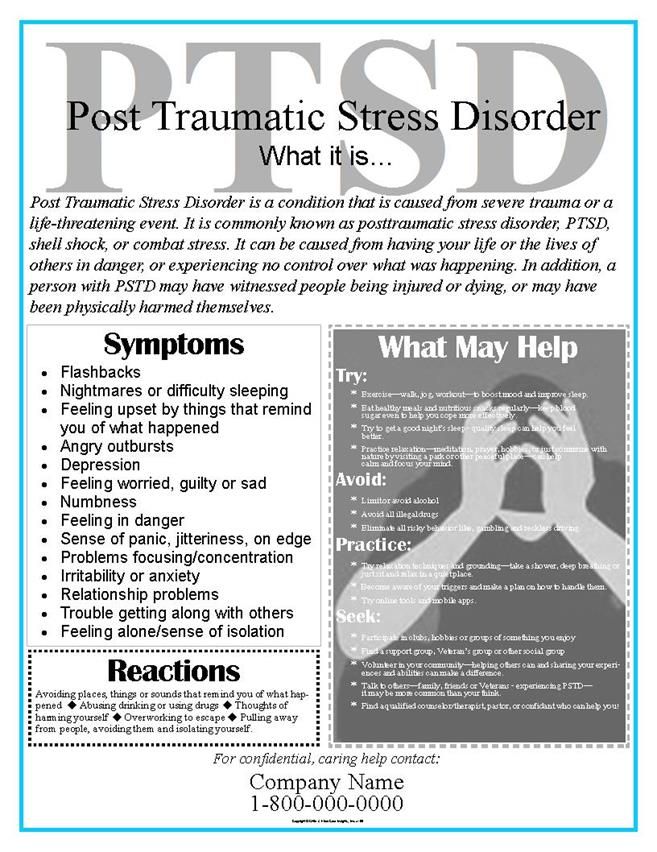

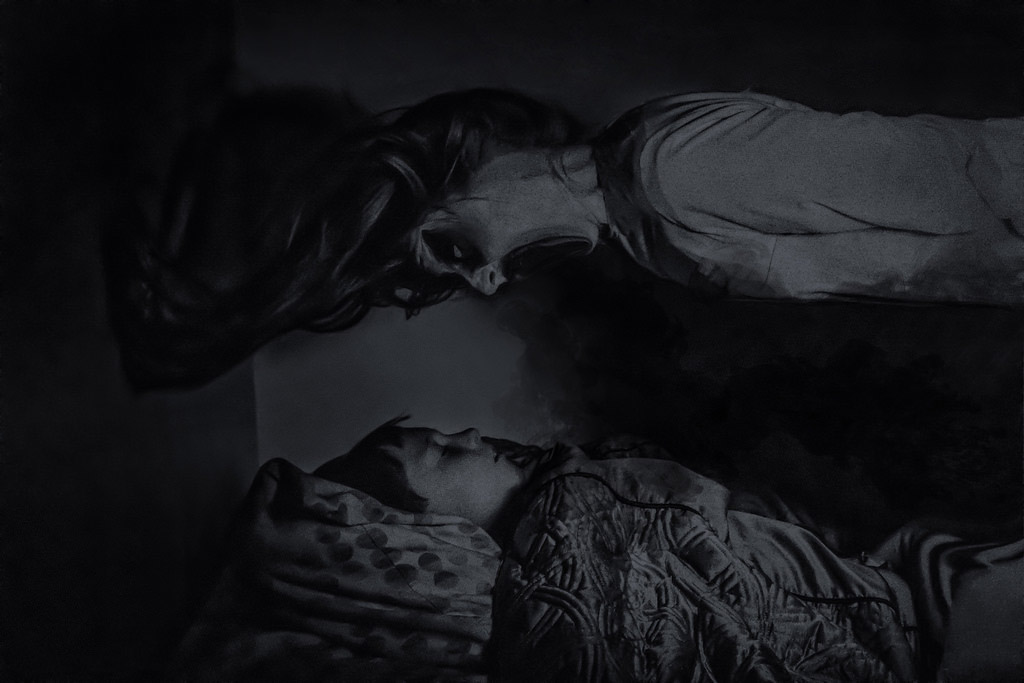

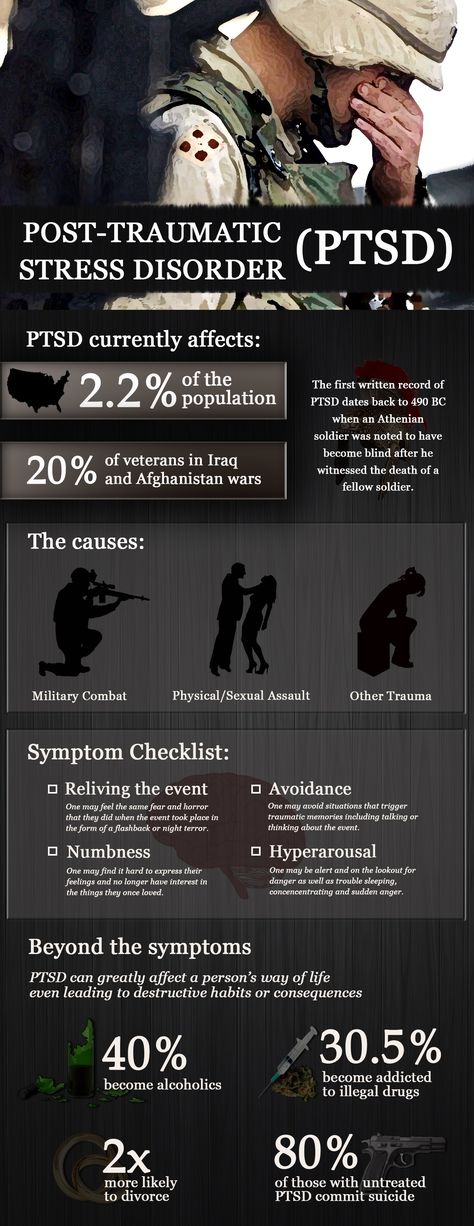

If you scream and flail in your sleep for a few seconds to a few minutes, it’s highly likely that you suffer from night terrors. One thing’s for sure, it’s an undesired occurrence that not only negatively affects you but also the people around you.

While anyone can suffer from night terrors, there are some people who are more prone to developing them. If you have been diagnosed with PTSD, or post-traumatic stress disorder, you are vulnerable to experiencing night terrors.

PTSD and Night Terrors

Approximately 96% of people with PTSD experience terrifying nightmares that are so vivid that they seem real. Unlike bad dreams, night terrors have physical manifestations such as thrashing, flailing, screaming, and even sleepwalking. Night terrors should be addressed early on because they can put you in serious danger. Sleeping beside someone who suffers from PTSD-induced night terrors can also cause emotional distress.

Night terrors come in episodes, and in a sleep terror episode, you may:

- Start with a scream

- Sweat profusely and breathe heavily

- Wake up frightened and wide-eyed

- Have a racing pulse

- Experiencing facial flushing and dilated pupils

- Kick, flail, and thrash

- Run around the house

- Have difficulty waking

- Cry or be inconsolable

- Turn aggressive when restrained

- Have no memory of the night terror episode

Any of the above behaviors are not normal and should not be shrugged off as if it were just a nightmare. Night terrors is considered a serious condition.

Treating PTSD-Induced Night Terrors

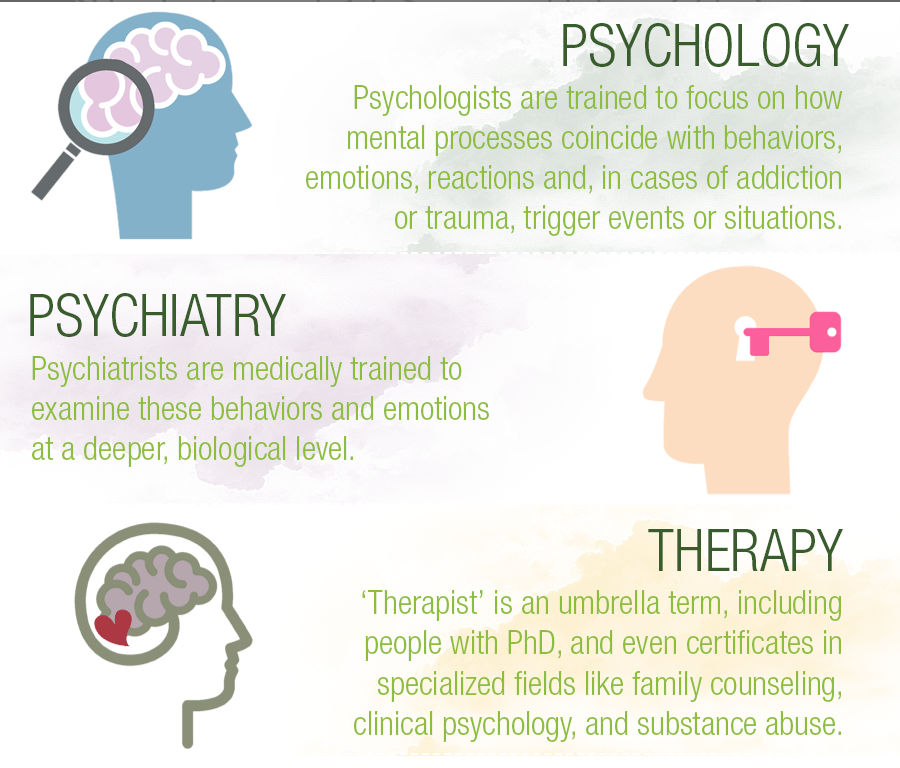

It’s important that you see a psychiatrist who specializes in treating PTSD-induced sleep disorders such as night terrors. At this point in your life, you need all the support you can get to work through your PTSD. Be open about it to your family, friends, and of course, your psychiatrist.

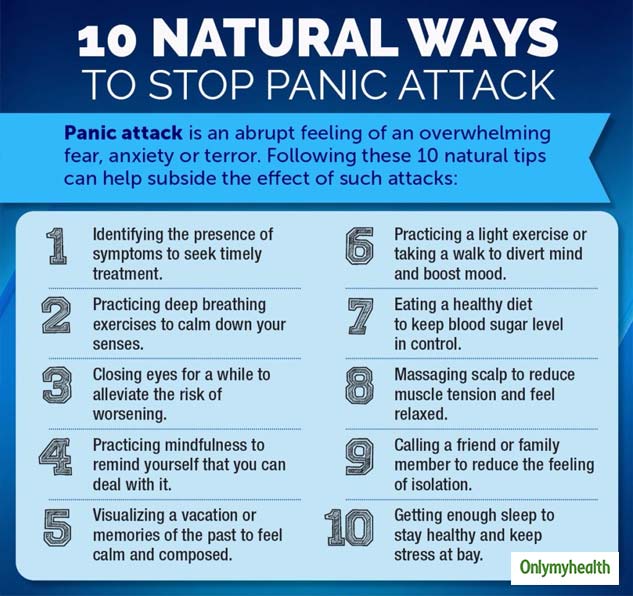

Treatment for PTSD-induced night terrors usually begins with making lifestyle changes such as:

- Getting adequate sleep

- Avoiding drugs and alcohol

- Healthy eating

- Keeping stress levels in check, such as with breathing exercises

- Exercising every day

- Doing yoga

- Making your sleep environment safe

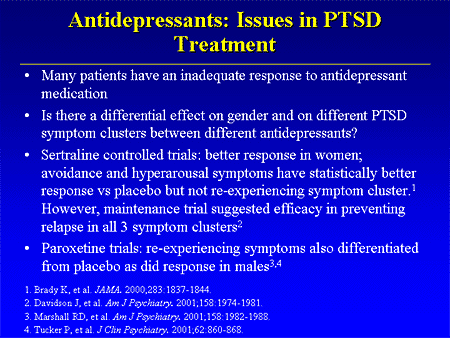

When lifestyle changes fail to resolve your night terrors, your psychiatrist may prescribe you with medication such as benzodiazepines and serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). But before a resorting to medication, a psychiatrist would first help you work through any anxiety – in this case, PTSD – before prescribing medication. Psychiatrists may also employ hypnosis, cognitive behavioral therapy, or relaxation therapy to help patients with PTSD-induced night terrors.

You may also be advised to undergo a sleep study to rule out other potential causes of your night terrors. You may have an underlying medical condition that requires treatment, too, such as obstructive sleep apnea.

Psychiatric Help in Connecticut

Dr. Mark Stracks of Psy-Visions delivers the highest quality care for his patients suffering from PTSD-induced night terrors. He diagnoses and treats a wide range of conditions and disorders, including sleep disorders. His style is to spend time listening to you and talking with you, which is very crucial to determining what you need to do together to help you start feeling better.

Dr. Stracks wants you to live a happy life, the kind you deserve. He will work with you to find an effective solution, even if you don’t like to take medication.

Feel free to reach out to Psy-Visions at (203) 405-1745 or you may request an appointment now.

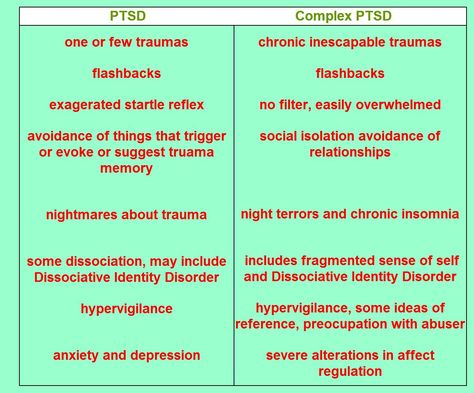

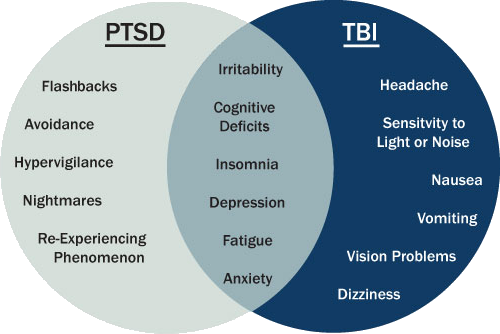

PTSD-related sleep disorders

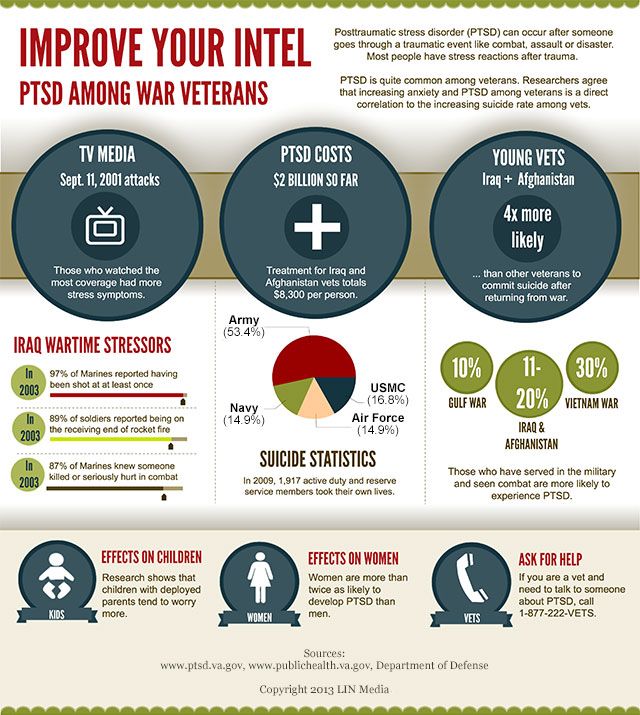

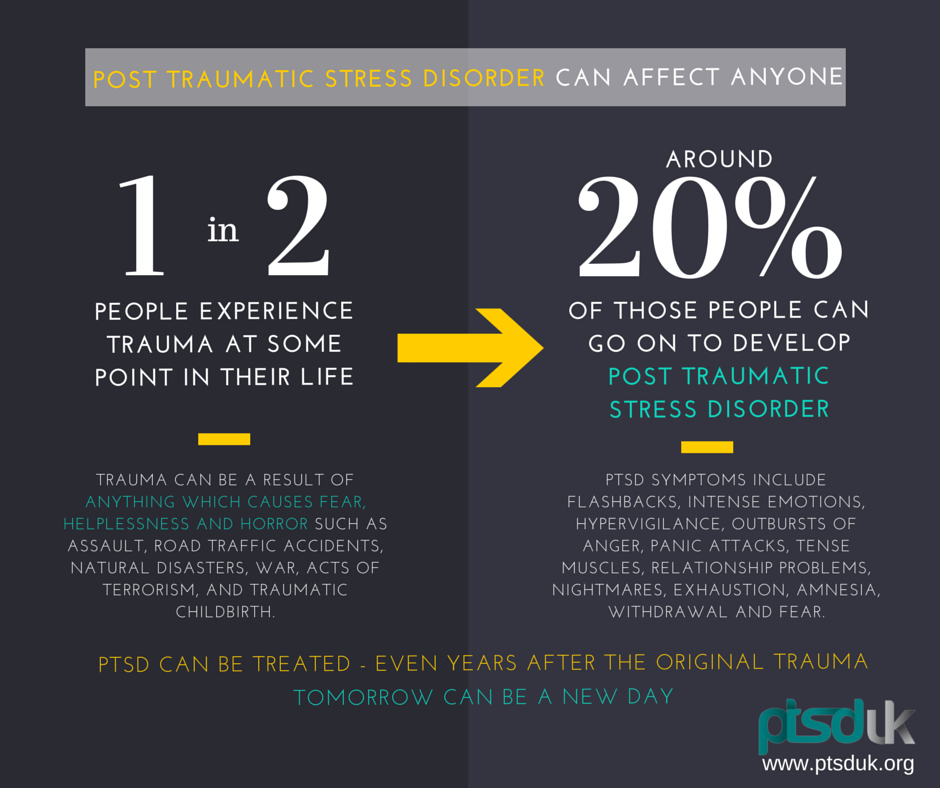

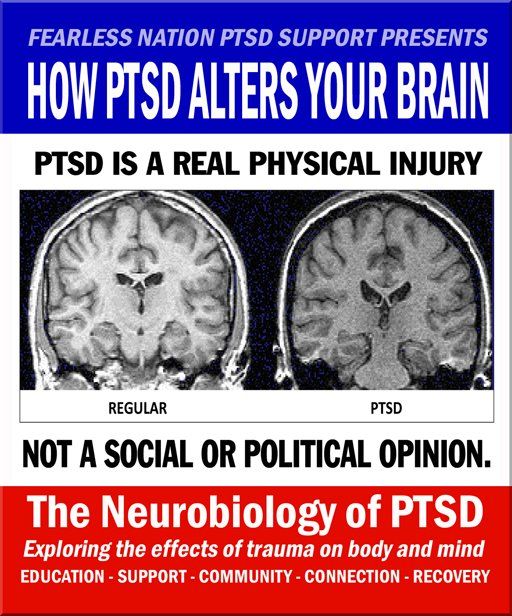

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a trauma- and stress-related disorder characterized by reliving, avoidance, excessive arousal, and negative changes in cognition or mood. Events that threaten the integrity of one's own body or others, such as rape, physical abuse, natural disasters, and combat are commonly associated with the development of post-traumatic stress disorder. The lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults in the United States ranges from 6% to 10%, with women more than twice as likely to have PTSD in some regions. nine0008

The lifetime prevalence of PTSD among adults in the United States ranges from 6% to 10%, with women more than twice as likely to have PTSD in some regions. nine0008

Significantly higher rates were registered among combat veterans (15–30%). The incidence of PTSD is higher in veterans if they have been in combat zones, have been on assignment for more than one year, have been in combat, or have been injured. In particular, among veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan, 31-86% report multiple injuries sustained during combat operations, and 11-20% confirm severe symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. nine0003

Sleep disorders associated with post-traumatic stress disorder

Sleep complaints are common after traumatic experiences. Subjective and objective sleep disturbances are associated with an increased risk of meeting the diagnostic criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder, and insomnia and nightmares are major diagnostic features of post-traumatic stress disorder and are also frequently reported by patients with PTSD. These sleep disturbances are known to exacerbate daytime symptoms and worsen clinical outcomes. This highlights the importance of monitoring the development of sleep disorders in patients with a history of trauma and their role as mediators of clinical outcomes in post-traumatic stress disorder. Sleep disorders in this population are often resistant to first-line treatment for PTSD. Sleep-specific interventions are commonly used to relieve insomnia and nightmares. Effective treatment has been associated with improvements in daytime symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, quality of life, and subjective physical health. nine0003

These sleep disturbances are known to exacerbate daytime symptoms and worsen clinical outcomes. This highlights the importance of monitoring the development of sleep disorders in patients with a history of trauma and their role as mediators of clinical outcomes in post-traumatic stress disorder. Sleep disorders in this population are often resistant to first-line treatment for PTSD. Sleep-specific interventions are commonly used to relieve insomnia and nightmares. Effective treatment has been associated with improvements in daytime symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, depression, quality of life, and subjective physical health. nine0003

Nightmares

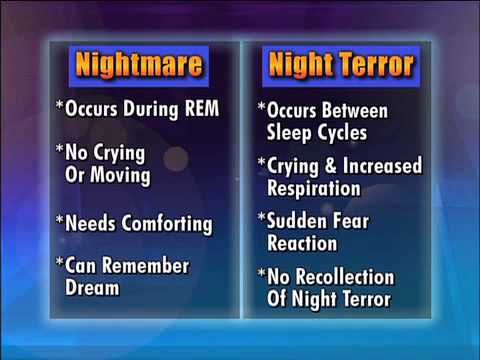

Nightmares are characterized by disturbing, memorable dreams that cause distress or disrupt daytime sleep (ICSD-3). Night terrors are not uncommon in the general population, with up to 85% of adults reporting at least one nightmare per year. Patients with post-traumatic stress disorder and psychiatric disorders experience nightmares much more frequently.

In addition, nightmares are associated with an increased risk of suicidal thoughts. Despite this, patients often underestimate nightmares and therefore fail to recognize them by clinicians. The high prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder and psychiatric disorders in military personnel leads to even higher levels of nightmares. Of military personnel sent for sleep assessments, 31% had nightmares at least once a week, significantly higher than the general population (0.9-6.8%).

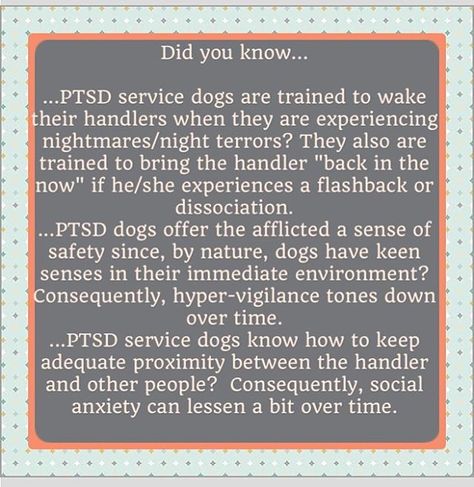

Treatment options for nightmares include a combination of behavioral therapies and medication. Imaginary rehearsal therapy (IRT) is a technique in which patients are taught to "rewrite" their nightmares and thus unlearn their behavior. This therapy has proven successful in combat veterans as well as civilians who have been traumatized. A variant of IRT called exposure. Rescripting and Relaxation Therapy (ERRT) incorporates aspects of traditional Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) with IRT. The combination of CBT for insomnia and IRT shows promising short-term effects in veterans with PTSD. Finally, pharmacological therapy with prazosin or positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may also be successful for nightmares. nine0003

The combination of CBT for insomnia and IRT shows promising short-term effects in veterans with PTSD. Finally, pharmacological therapy with prazosin or positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may also be successful for nightmares. nine0003

Trauma-related sleep disorder

In a subgroup of patients with post-traumatic stress disorder, trauma-related nightmares are accompanied by parasomnias. Trauma-related sleep disorder is a recently proposed unique parasomnia that describes the clinical features of trauma-related nightmares in association with disruptive nocturnal behaviors (DNBs).

Destructive nocturnal behaviors consist of abnormal vocalizations (screams, moans) and movements (beating, turning, sleepwalking) as well as aggressive behaviors (hitting or kicking a bed partner). DNP often mimics nightmarish content. Autonomic signs of hyperarousal (rapid heart rate, rapid breathing, night sweats) are often associated with this behavior. nine0003

nine0003

Polysomnogram (PSG) scores typically show sleep recall behavior and increased muscle activity during the rapid eye movement phase (REM without atony). These patients almost always have nightmares. Trauma-related sleep disturbance can also occur along with insomnia and sleep apnea. Therefore, in patients with symptoms of a trauma-related sleep disorder, polysomnography is recommended to look for sleep breathing disorders in addition to assessing whether the patient has abnormal behaviors and/or movements during REM sleep. nine0003

There are currently no evidence-based guidelines for the treatment of this newly proposed sleep disorder. Getting enough sleep, avoiding triggers, and creating a safe sleep environment are critical. In some cases, drug therapy may be required to suppress these phenomena. Some patients respond well to combined treatment with prazosin for nightmares and disruptive nighttime behavior, behavioral therapy for insomnia, and CPAP therapy for sleep apnea. nine0003

nine0003

Insomnia

Insomnia is the most common sleep complaint among both civilians and military personnel (MSMR 2013). It is also the most common symptom among returning service members and combat veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Up to 74% of combat veterans with PTSD meet the clinical criteria for insomnia.

In addition, sexually traumatized veterans are more likely to experience insomnia symptoms (61%) than non-injured veterans (53%). Insomnia is associated with higher severity of post-traumatic stress disorder and does not tend to resolve spontaneously over time. nine0003

Treatment options for insomnia in patients with PTSD are similar to those for the general population. However, insomnia in PTSD patients may be complicated by their PTSD symptoms as well as comorbid sleep disturbances and unhealthy sleep practices. Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) improves sleep quality as well as daytime symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder in this population. In addition, combination therapy of CBT and imaginative rehearsal therapy (IRT) may be beneficial in patients with coexisting nightmares. There are currently no evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of insomnia in the PTSD population due to a lack of high-quality research. nine0003

In addition, combination therapy of CBT and imaginative rehearsal therapy (IRT) may be beneficial in patients with coexisting nightmares. There are currently no evidence-based guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of insomnia in the PTSD population due to a lack of high-quality research. nine0003

Although the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) generally does not recommend a polysomnogram for patients with chronic insomnia, PTSD patients have a high incidence of comorbid sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS) and periodic limb movement disorders. Polysomnography should be considered for post-traumatic stress disorder in patients with insomnia, especially if standard insomnia treatment fails. nine0003

Sleep disturbance

While insomnia and nightmares have been the most commonly reported sleep symptoms in the PTSD literature, more attention has recently been paid to the prevalence and significance of sleep disturbance in patients with PTSD. disorder. Respiratory failure, most commonly in the form of sleep apnea, affects 9-38% of the adult population, with higher rates among men, the elderly, and obese people. In addition, among the military, the frequency of sleep apnea syndrome up to 60-85% was reported. nine0003

disorder. Respiratory failure, most commonly in the form of sleep apnea, affects 9-38% of the adult population, with higher rates among men, the elderly, and obese people. In addition, among the military, the frequency of sleep apnea syndrome up to 60-85% was reported. nine0003

In addition, recent literature indicates that people with PTSD have a disproportionately higher rate of sleep disturbances than the general population, with an incidence of comorbid PTSD and sleep apnea (15-90%) , depending on the diagnostic methodology used. Krakow et al., et al. proposed a new hypothesis that includes a bidirectional explanation for why patients with post-traumatic stress disorder have a high incidence of sleep apnea. This hypothesis is that the fragmentation of sleep (nightmares, insomnia) seen in post-traumatic stress disorder affects the airways, causing collapse of the upper airways and episodes of disturbed breathing during sleep. These events further fragment sleep, leading to worsening insomnia and nightmares that worsen common symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder. nine0003

nine0003

This may have clinical implications for the subset of PTSD patients who also suffer from sleep disorders, and more research is needed to clarify the best methods of diagnosis and treatment. Studies evaluating the treatment of patients with comorbid PTSD and sleep disorders show that positive airway pressure therapy can improve sleep by reducing sleep fragmentation and nightmares. nine0007

Unfortunately, PTSD patients tend to have suboptimal adherence to positive airway pressure. Because of the potential adverse outcomes of comorbid psychiatric illness and sleep disturbances, including suicide, treatment should begin as early as possible.

Conclusions

Sleep disturbances are common in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder and are often resistant to standard first-line therapies. This can lead to worsening of PTSD symptoms and worse clinical outcomes. Insomnia and nightmares are the most common sleep problems in patients with post-traumatic stress disorder, and treatment consists of a combination of behavioral methods and pharmacological therapy. Trauma-related sleep disorder is a recently described parasomnia that can occur in some patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. The prevalence of sleep apnea is higher in patients with PTSD than in the general population. Thus, polysomnography should be considered in PTSD patients with sleep disturbances, especially those who are resistant to initial treatment. CPAP therapy can improve daytime functioning as well as symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, but adherence to therapy is usually low. nine0006 Evaluation and treatment of sleep disorders should be an integral part of the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder to limit their adverse effects on daytime symptoms and overall functioning.

Trauma-related sleep disorder is a recently described parasomnia that can occur in some patients with post-traumatic stress disorder. The prevalence of sleep apnea is higher in patients with PTSD than in the general population. Thus, polysomnography should be considered in PTSD patients with sleep disturbances, especially those who are resistant to initial treatment. CPAP therapy can improve daytime functioning as well as symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder, but adherence to therapy is usually low. nine0006 Evaluation and treatment of sleep disorders should be an integral part of the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder to limit their adverse effects on daytime symptoms and overall functioning.

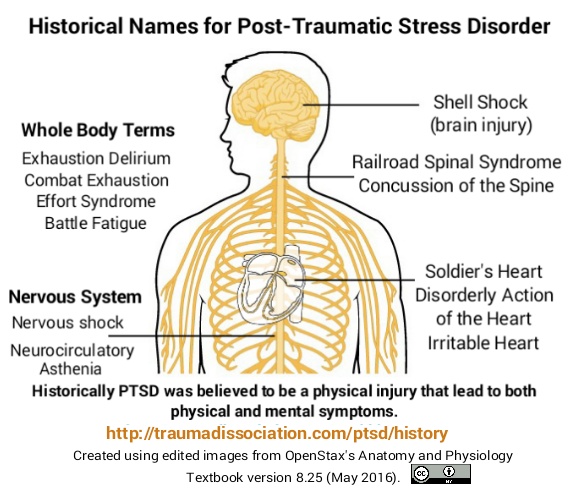

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD): symptoms, causes and treatment of PTSD

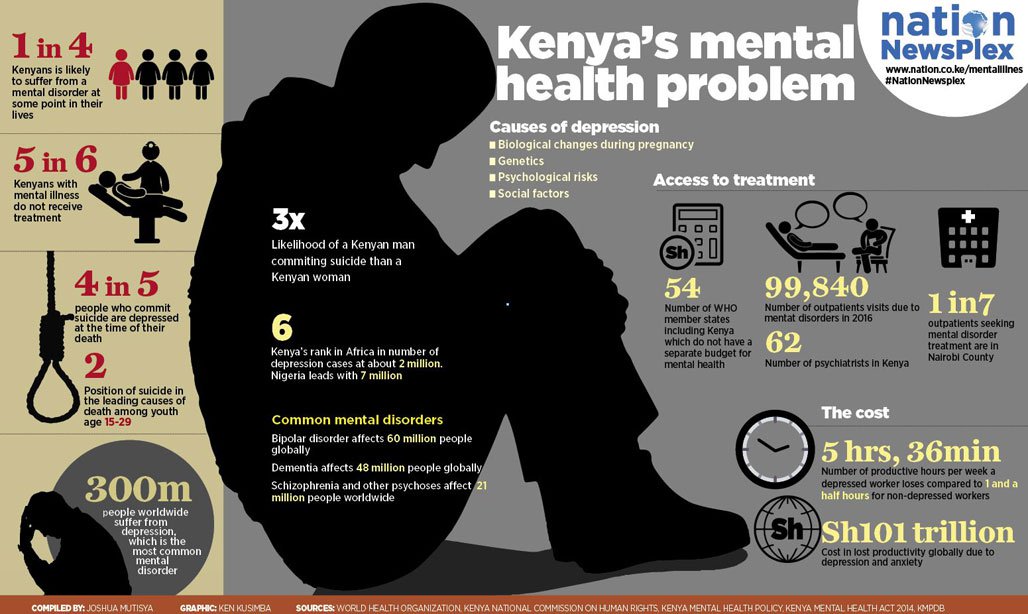

Severe stress, fears, constant nervous tension can be caused by various reasons. For many Ukrainians, these factors were the war and the complete destruction of plans for the future. Post-traumatic stress disorder can also be caused by other activators - terrible events in life experienced by a catastrophe, natural disaster, violence. Any situation that is traumatic for a person can lead to the development of PTSD. nine0003

Post-traumatic stress disorder can also be caused by other activators - terrible events in life experienced by a catastrophe, natural disaster, violence. Any situation that is traumatic for a person can lead to the development of PTSD. nine0003

In the majority of diagnosed cases, the disorder is caused by:

- wars, catastrophes, acts of terrorism;

- accidents with serious consequences;

- sexual emotional, physical abuse;

- natural disasters;

- serious illnesses;

- stressful situations at work or at the place of study;

- complex losses, for example, the death of a loved one.

PTSD can develop in all generations. Activating factors for the development of the disorder can be strong feelings, abuse, professional risks (work in the police, armed forces, fire departments, etc.). The presence of psychiatric and anxiety disorders, alcohol and drug abuse can also increase the risk of developing PTSD. Problems may be related to heredity (for example, PTSD is more likely to develop in people whose relatives suffer from similar diseases). The lack of support of loved ones in the most difficult moments of life can become the “last straw” for the onset of symptoms of post-traumatic disorder. nine0003

Problems may be related to heredity (for example, PTSD is more likely to develop in people whose relatives suffer from similar diseases). The lack of support of loved ones in the most difficult moments of life can become the “last straw” for the onset of symptoms of post-traumatic disorder. nine0003

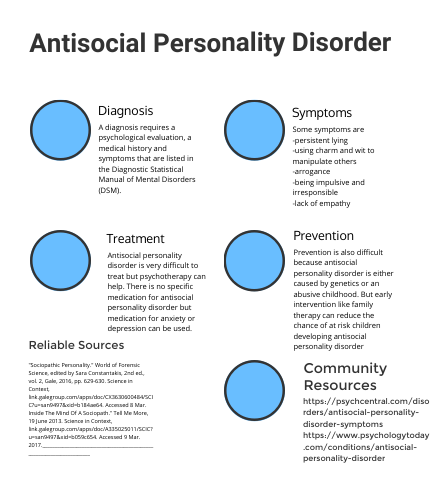

Diagnosis of PTSD

Diagnosis can only be made by a doctor after a series of examinations. The reason for contacting a specialist may be experienced psychological or physical trauma or any of the symptoms, which we will discuss below. To diagnose the disorder, a doctor performs a physical examination, a psychological assessment, and tests the patient for PTSD. Special questionnaires are used as test material.

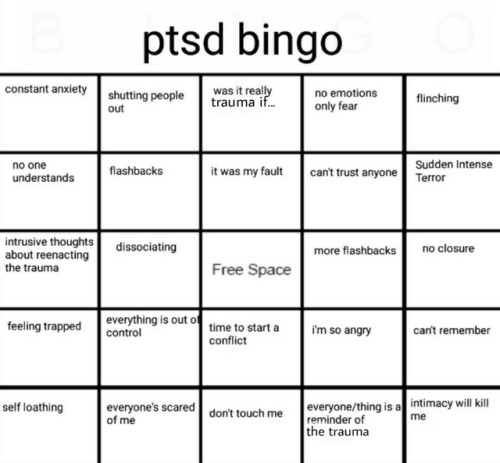

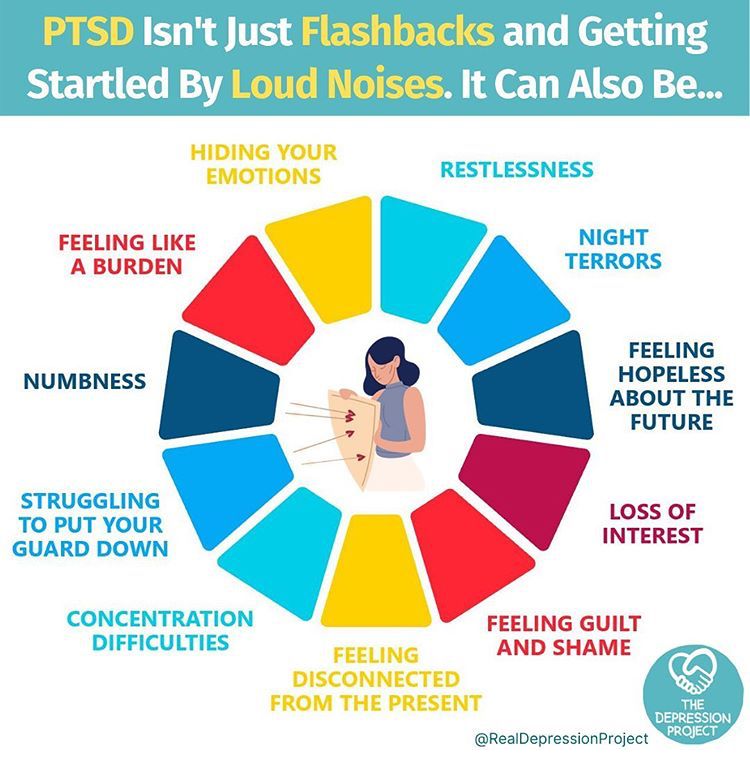

Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder

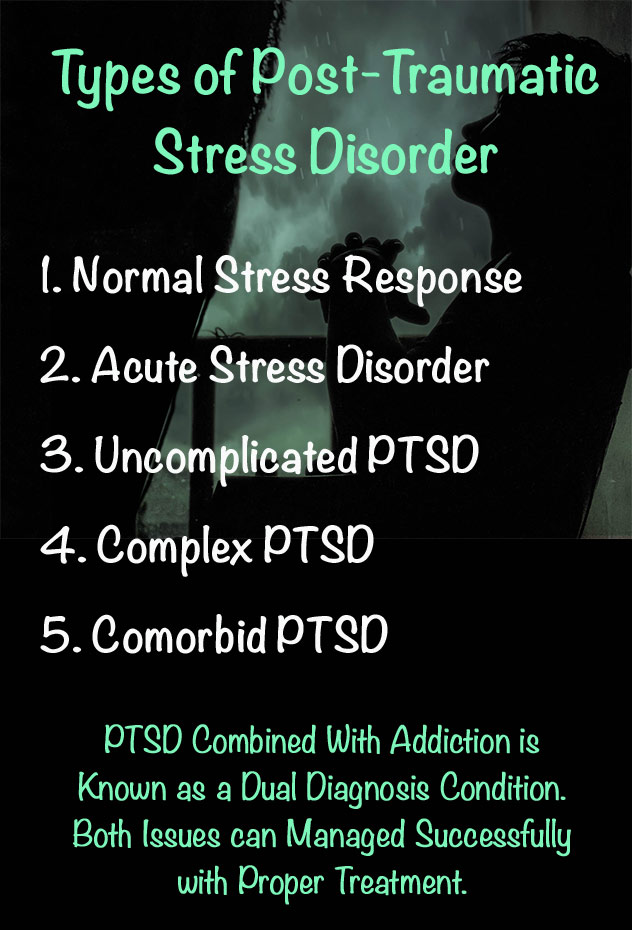

It is far from always that the disease manifests itself immediately after the onset of a stressful situation. In many cases, the problem becomes apparent years later. Symptoms of the disease can be divided into 4 categories:

- obsessive memories - often occurring memories of traumatic factors, experienced stress, as well as - terrible dreams, nightmares, a strong stress reaction to such memories;

- avoidance - refusal to remember the traumatic event and any mention of it, including - refusal to visit places associated with the trauma, communicate with people associated with the situation; nine0114

- negative changes in the mental sphere - a feeling of loneliness, isolation from the world, negative thoughts about oneself, a feeling of hopelessness, loss of interest in hobbies and favorite activities, emotional burnout;

- physical and emotional changes - the appearance of fright, tremors of the limbs, alcohol or drug abuse, sleep disturbances and problems concentrating on any object or activity, violent outbursts of anger, irritability, aggression, strong feelings of shame and guilt.

nine0114

nine0114

In childhood, post-traumatic stress disorder can manifest itself in recreating traumatic situations in a playful way. Among the symptoms of childhood PTSD, sleep disturbances and nightmares can also be distinguished.

Treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder

Treatment for PTSD is provided to improve the patient's physical and emotional well-being. The psychotherapist will prescribe therapy that helps to level the influence of traumatic factors on the life and condition of the patient. As a rule, treatment is carried out in a complex manner and includes the use of psychotherapy and drug therapy. Drug treatment involves taking medications that relieve symptoms:

- antidepressants;

- anti-anxiety drugs;

- prazosin, which reduces nightmares.

Psychotherapy may combine cognitive, exposure and desensitization techniques.

In order to prevent PTSD in adults and children after the onset of a traumatic situation, we recommend contacting a specialist.