Antecedents definition psychology

What is Antecedent-Behavior Consequence (ABC)?

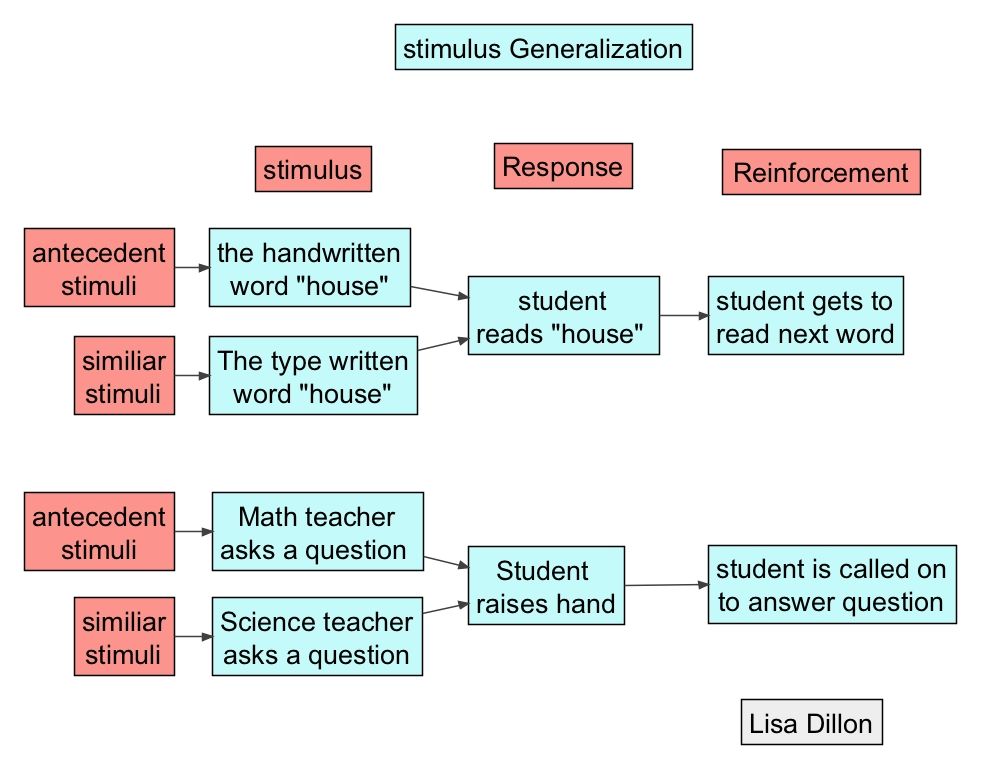

Antecedent-Behavior-Consequence (ABC) is a significant component of understanding the function of behavior. If a child is in ABA therapy or a therapeutic preschool program for additional behavioral support, their teachers and therapists will often examine these components of behavior.

What exactly does ABC mean?

Antecedent: This refers to the stimuli or activity that occurs just before a child exhibits the behavior. In some cases, the antecedent is also the root cause of the behavior for the child.

Behavior: This refers to the behavior that follows the antecedent.

Consequence: This refers to the event or consequence that follows the behavior.

By looking at a behavior in a logical chain of progression, it is easier to determine the function of a behavior and better understand why a child is acting in a certain way.

Here’s an example of using ABC to understand a child’s behavior:

Antecedent: The therapeutic preschool teacher prompts the student to come to the carpet for circle time.

Behavior: The child will not move and begins to cry that they do not want to join circle time.

Consequence: The therapeutic preschool aid stays with the child to try and help the child regulate their behavior.

ABC chart

ABA therapists will often use ABC charts to map out specific behaviors and examine the function of behavior in children. By looking at the entire cycle of a behavior, from the stimuli that incites the behavior to the consequence, the therapist or teacher has a greater understanding of a child’s behavioral patterns. The insight that an ABC chart provides also helps to create a comprehensive treatment plan.

Why is ABC important?

If a child is exhibiting problematic behaviors at home or in their therapeutic preschool program, it is critical to understand the function of the behavior, in order to resolve it. Every child has their own way of learning and processing information, so two children who are crying during their therapeutic preschool class may be doing so for two completely different reasons. In order to solve the behavior “puzzle,” an ABA therapist or therapeutic preschool teacher may use ABC charts.

In order to solve the behavior “puzzle,” an ABA therapist or therapeutic preschool teacher may use ABC charts.

ABC is particularly important in the context of applied behavior analysis or ABA therapy services provided in a therapeutic preschool program. Using this method of intervention, the teacher or therapist will work with the child to build positive behaviors and skills and resolve problematic behaviors. ABA also looks at the function of behavior.

Do you think your child could benefit from a therapeutic preschool program for behavior support? Contact CST Academy by clicking the purple button below or calling 773-620-7800 to learn more about our services for children in Chicago, including ABA therapy, feeding therapy, occupational therapy, and speech therapy.

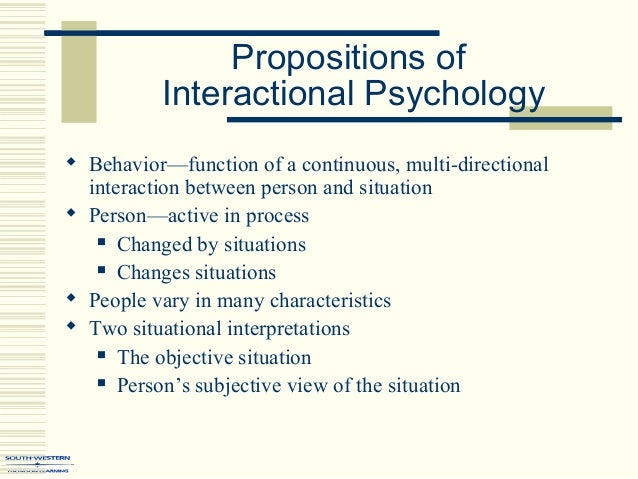

Behavior Intervention 101: Antecedent Interventions

What are Antecedents?In applied behavior analysis (ABA), we talk a lot about the events that precede and follow target behaviors. An antecedent is something that happens immediately before a behavior. Similarly, a setting event is something that happened some time (not immediately) before the behavior. Setting events might have carryover effects on someone’s behavior. For example, an antecedent could be telling a child to do his or her homework, which then results in the child engaging in aggression. A setting event could be not getting enough sleep the night before. Therefore, the child may be tired, making aggression more likely to occur.

An antecedent is something that happens immediately before a behavior. Similarly, a setting event is something that happened some time (not immediately) before the behavior. Setting events might have carryover effects on someone’s behavior. For example, an antecedent could be telling a child to do his or her homework, which then results in the child engaging in aggression. A setting event could be not getting enough sleep the night before. Therefore, the child may be tired, making aggression more likely to occur.

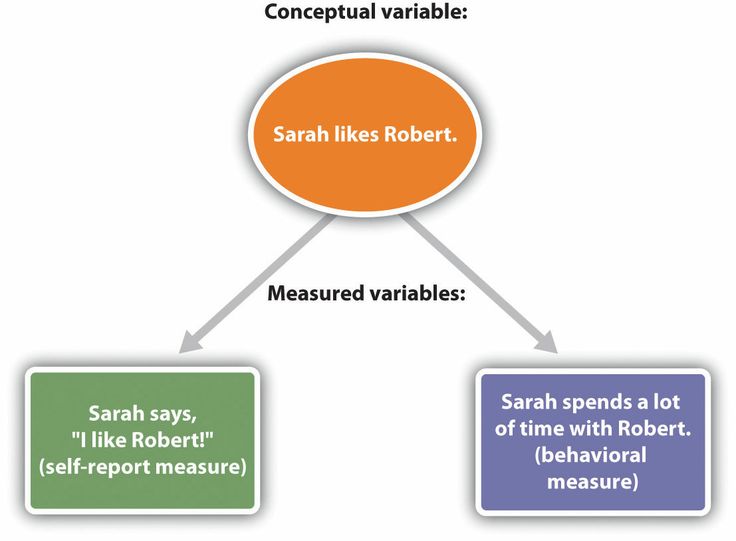

Taking antecedent-behavior-consequence (ABC) data provides information about what tends to evoke problem behaviors. When analyzing this data, you can identify the hypothesized function of a behavior. Read our previous post about the 4 functions of behavior for more information. Once you have identified a potential function, you can develop antecedent interventions to decrease the occurrence of the behavior.

What are Antecedent Interventions?Based on a hypothesized function of a behavior, you can develop antecedent interventions. The goal of these interventions is to alter the environment so the targeted problematic behaviors are less likely to occur. Many antecedent interventions don’t completely prevent the problem behaviors from happening. Instead, they decrease the likelihood of occurrence.

The goal of these interventions is to alter the environment so the targeted problematic behaviors are less likely to occur. Many antecedent interventions don’t completely prevent the problem behaviors from happening. Instead, they decrease the likelihood of occurrence.

Studies such as Haley et al. (2010) and Kruger et al. (2015) have shown that the use of antecedent interventions significantly reduce the likelihood of problematic behaviors. These interventions are even more effective when chosen based on the hypothesized function of the problem behavior. Antecedent interventions such as those discussed below have been used in a variety of situations. These include feeding problems, repetitive behaviors, and aggressive behaviors.

The best way to understand how you can use these interventions is to break down some common antecedent interventions based on the determined function of a behavior.

Antecedent Intervention Ideas by Function| Function | Possible Antecedent Interventions |

| Escape | Allow choices between work tasks Provide more frequent breaks Incorporate the person’s interests into the work tasks Use behavior momentum (i.  e., have the person complete several easy tasks before asking them to do a more difficult one) e., have the person complete several easy tasks before asking them to do a more difficult one)Provide different methods of completing assigned tasks |

| Attention | Non-contingent reinforcement (i.e., provide attention on a fixed time schedule) Allow for frequent opportunities to respond Provide high-quality verbal praise (e.g., enthusiastic, behavior-specific) |

| Tangible | Use a visual schedule to indicate when the preferred item will be available and for how long Non-contingent reinforcement (i.e., allow access to the item on a fixed time schedule) Provide adequate opportunities to have access to the preferred item |

| Sensory | First, address any potential medical concerns Enrich the learning environment Provide a set time for sensory behaviors Provide more socially acceptable way to access the same sensory input Include sensory activities in instructional tasks |

Use of antecedent interventions should not begin when challenging behaviors are already unmanageable. Antecedent interventions should be implemented as soon as behavior challenges are noted. In schools, teachers can plan ahead by beginning the school year with antecedent strategies in place. These may include visual schedules and enriching the learning environment. Also, remember that many behaviors have multiple functions. Therefore, preparing strategies to account for multiple functions will likely decrease challenging behaviors in the class as a whole.

Antecedent interventions should be implemented as soon as behavior challenges are noted. In schools, teachers can plan ahead by beginning the school year with antecedent strategies in place. These may include visual schedules and enriching the learning environment. Also, remember that many behaviors have multiple functions. Therefore, preparing strategies to account for multiple functions will likely decrease challenging behaviors in the class as a whole.

Haley, J. L., Heick, P. F., & Luiselli, J. K. (2010). Use of an Antecedent Intervention to Decrease Vocal Stereotypy of a Student With Autism in the General Education Classroom. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 32(4), 311–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317107.2010.515527

Kruger, A. M., Strong, W., Daly, E. J., O’Connor, M., Sommerhalder, M. S., Holtz, J., Weis, N., Kane, E. J., Hoff, N., & Heifner, A. (2015). SETTING THE STAGE FOR ACADEMIC SUCCESS THROUGH ANTECEDENTINTERVENTION. Psychology in the Schools, 53(1), 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21886

Psychology in the Schools, 53(1), 24–38. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21886

Antecedents of emotions | Relationship Psychology

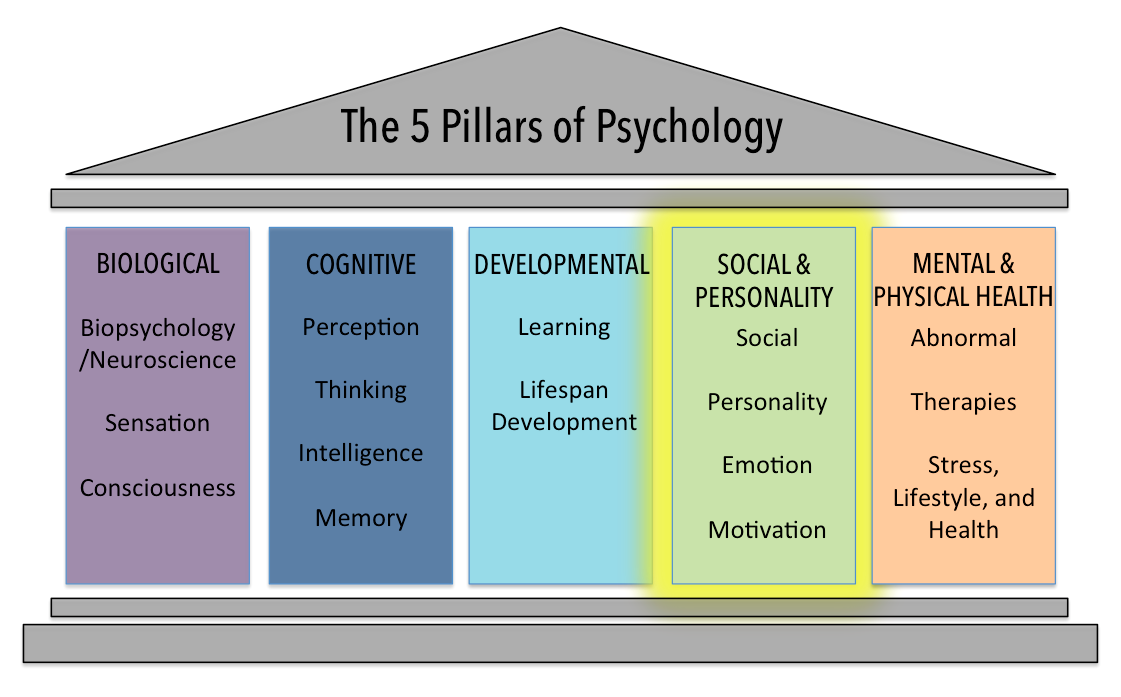

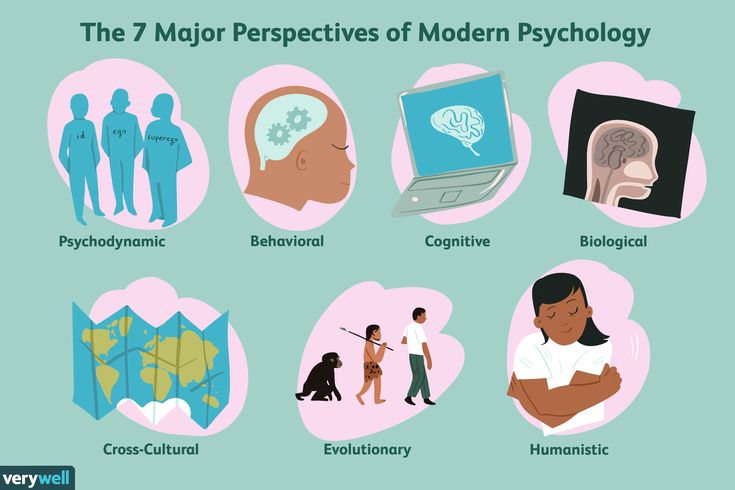

In this chapter, we reviewed the evidence for the significant persistence of emotions across cultures, supporting the notion that emotions are biologically based. We also discussed approaches that view emotions as phenomena that have a cultural identity rooted in cognitive and social processes. Finally, we have studied predominantly differentiated representations, according to which

61 See, for example, Fischer, 1991.

Both biological and cultural orientations could be reconciled. The topic of discussion coincides with the main theme of this book: the relative manifestation of universality and cultural specificity in human psychological activity.

The absolutist position axiomatically affirms the pan-cultural invariance of emotions. The role of cross-cultural emotion research is limited to helping identify the true set of core emotions. Interpretations of differences never go beyond rules of expression and situations with specific cultural meanings. Such an approach runs the risk of cultural sterility by claiming a priori that all differences are random. Equally fruitless is the axiomatic position that all emotions must be different. When Kitayama and Marcus (1994, p. 1) state: "In particular, we want to establish that emotion can be fruitfully conceptualized as a phenomenon that is social in nature" or, in the words of Lutz (1988), as "anything but natural"", one should ask whether this statement is a symbol of faith or the result of a study. Component approaches allow for a more differentiated point of view and can lead to greater balance.

Interpretations of differences never go beyond rules of expression and situations with specific cultural meanings. Such an approach runs the risk of cultural sterility by claiming a priori that all differences are random. Equally fruitless is the axiomatic position that all emotions must be different. When Kitayama and Marcus (1994, p. 1) state: "In particular, we want to establish that emotion can be fruitfully conceptualized as a phenomenon that is social in nature" or, in the words of Lutz (1988), as "anything but natural"", one should ask whether this statement is a symbol of faith or the result of a study. Component approaches allow for a more differentiated point of view and can lead to greater balance.

Perhaps there is no other empirical evidence that fits the universalist view more appropriately than the accumulated cross-cultural study of emotion. On the one hand, the differences between basic emotions, as expressed in systematic Western psychological research, were repeated in all those studies,

In the thirty-seven country study just mentioned, respondents were also asked questions about other components of emotional experience, including motor manifestations, physiological symptoms, and subjective sensations55. The research project made it possible to estimate the scale:

The research project made it possible to estimate the scale:

1 differences in emotions;

2 differences between countries:

3 relationship between countries and emotions.

Significant differences were found in the area of emotions. The differences between countries were clearly smaller, and the relationship between countries and emotions was even smaller. The latter result can be interpreted as a sign of consistency in patterns of country differences and emotions. Scherer & Wallbott (1994, p. 310) interpret their findings "as support for theories that posit a high degree of universality in the patterning of various emotions, as well as important cultural differences in the expression, regulation, symbolic representation, and social generalization of emotions."

The component approach to emotions can be seen as an attempt to free the study of emotions from the constraining focus on a small set of basic emotions, which, in turn, is accompanied by a limitation in the choice of methods. A broader view should be provided, focusing on the influence of a particular cultural environment on the emerging emotional life56. Conceptually, this enrichment is mainly reflected in the differentiation0003

A broader view should be provided, focusing on the influence of a particular cultural environment on the emerging emotional life56. Conceptually, this enrichment is mainly reflected in the differentiation0003

55 See Scherer & Walibott, 1994.

56 See Mesquila et al., 1997.

Citation of various components. Of course, modern listing of ingredients need not be strictly defined. We have already pointed out the close relationship of the various components, and perhaps there are some more components that should be added. An example of social sharing (generalization) of emotions is communication with others about emotionally charged events. There are clearly defined patterns of dominance and preference in dealing with “others” who belong to such social categories as parents, partners, friends, etc.57. The predominantly unitary conceptualizations of emotions have also been extended by classification according to parameters or according to prototypes58. According to the theory of prototypes, there is a level of classification with an optimal combination of inclusion and informativeness, which is called the main level59. In cross-cultural studies on the cognitive structure of emotions, two higher-order groups are usually distinguished, in which positive and negative emotions are distinguished. At a slightly lower level of involvement, four categories of basic emotions were identified, which correspond to anger, fear, sadness and positive emotion60.

In cross-cultural studies on the cognitive structure of emotions, two higher-order groups are usually distinguished, in which positive and negative emotions are distinguished. At a slightly lower level of involvement, four categories of basic emotions were identified, which correspond to anger, fear, sadness and positive emotion60.

With regard to methodology, researchers try not to provide respondents with single terms for defining emotions, but develop descriptions more carefully with more contextual information,

57 See Rime, Mesquita, Philippot & Boca, 1991; Rime,

Philippot, Boca & Mesquita, 1992.

58 See, for example, Russell, 1991; Fehr & Russell, 1984;

Shaver, Wu & Schwartz, 1992.

5S Cm. Rosch, 1978. 60 See Shaver, 1992.

Including sequential aspects of an emotional event. Such scenarios are referred to as “emotion scenarios”61. Needless to say, scripts allow for finer distinctions than generalized representations of emotion through a single word or paragraph from a single utterance. nine0003

nine0003

Of course, the extent of the new understanding of the relationship between culture and emotion that these broader approaches have led to remains an important issue. It is difficult to give a definite answer. In fact, we don't even have a fair idea of the extent to which cross-cultural differences exist; their generalization occurs outside the narrow categories of culture-specific situations. Mesquita (1997) argued that significant cross-cultural differences were found for the different components. However, their review also contains evidence of the existence of a large similarity. It is necessary to conduct a study to connect these two conclusions, which allow us to simultaneously evaluate both similarities and differences. Such an attempt is discussed in Appendix 7.1. nine0003

When a person encounters a situation, it is quickly and automatically evaluated. Evaluation. She offers "a key to understanding the conditions of expression of various emotions, and also to understanding what distinguishes one emotion from another"51. A limited set of parameters was usually found, including attention to change or novelty: pleasure versus unpleasantness, certainty versus insecurity, a sense of control, and mediation, i.e. whether the situation is happening by itself, because of someone else, or because of someone else. human mediator. Emotions such as happiness and fear differ in terms of characteristic patterns on these evaluation parameters. nine0003

A limited set of parameters was usually found, including attention to change or novelty: pleasure versus unpleasantness, certainty versus insecurity, a sense of control, and mediation, i.e. whether the situation is happening by itself, because of someone else, or because of someone else. human mediator. Emotions such as happiness and fear differ in terms of characteristic patterns on these evaluation parameters. nine0003

A series of studies initiated by Scherer52 used an open-ended questionnaire to inquire about an event in a respondent's life that was associated with one of the four emotions (joy, sadness, anger, fear). In addition to the emotional sensations themselves, the questions concerned assessments and reactions. Very few differences between European countries were found. The main differences between the US, Europe, and Japan were in the relative importance of the identified situations. It was also found that American respondents showed higher and Japanese respondents lower emotional reactivity than Europeans. nine0003

nine0003

Scherer and colleagues (1988) were quite willing to make quantitative comparisons of different crops. They write, for example:

51 See Frijda, 1993, p. 225.

52 See Scherer, Wallbott & Summerfield, 1986; Scherer

Wallbott, Matsumoto & Kudoh 1988 maybe more of a sense of being safe in a social support network. It is difficult to understand why American respondents generally show higher intensity of emotions, especially joy and anger. These results can be attributed to either higher emotionality or emotional responsiveness of American respondents53. nine0003

However, before accepting such interpretations at face value, we would like to make sure that the obvious challenges to cross-cultural equivalence (see Chapters 4 and 11), which arise from response styles, for example, have been eliminated.

In a later project with respondents from thirty-seven countries, situations were included for evaluation. This time, previously coded response scales for assessed situations were presented, which were drawn from the theory developed by Scherer (1986). Respondents were again asked to reflect on emotional experiences (joy, anger, fear, sadness, disgust, shame, and guilt) and then asked questions about whether they expected the event to happen, whether it was pleasant, whether it prevented them from achieving their goals, etc. Schererer (1997a, 1997b) found that different emotions exhibited strong differences in evaluation patterns, supporting this finding by the fact that each of the major emotions examined

Respondents were again asked to reflect on emotional experiences (joy, anger, fear, sadness, disgust, shame, and guilt) and then asked questions about whether they expected the event to happen, whether it was pleasant, whether it prevented them from achieving their goals, etc. Schererer (1997a, 1997b) found that different emotions exhibited strong differences in evaluation patterns, supporting this finding by the fact that each of the major emotions examined

53 See Schereretal., 1988, p. 21.

In the study, has the same evaluation profiles everywhere. Significant differences between countries were also found, indicating that certain metrics are more prominent in a number of countries.

The greatest differences were found with regard to the question of whether an event caused by a human would be considered indecent or immoral. The next largest difference was found in responses to questions about injustice or disadvantage. African respondents generally scored high on the measure of immorality and indecency, while Latin America scored low on the immorality scale. Interpretation of differences between countries was hindered by the fact that respondents selected emotional events from their own experience, which could lead to systematic differences in any aspect other than the target emotion. While we agree with Scherer that these data support both universality and cultural specificity in the emotional process, the first aspect is quite striking given the fact that the emotion label was the only constraint on respondents' selection of experiences. Mesquita (1997) rightly draws attention to the fact that the similarity of evaluative parameters, which are at a high level of generalization, may obscure more specific interests, such as concern for honor, which has been found to prevail in Mediterranean countries54.

Interpretation of differences between countries was hindered by the fact that respondents selected emotional events from their own experience, which could lead to systematic differences in any aspect other than the target emotion. While we agree with Scherer that these data support both universality and cultural specificity in the emotional process, the first aspect is quite striking given the fact that the emotion label was the only constraint on respondents' selection of experiences. Mesquita (1997) rightly draws attention to the fact that the similarity of evaluative parameters, which are at a high level of generalization, may obscure more specific interests, such as concern for honor, which has been found to prevail in Mediterranean countries54.

See Alu-Lughod, 1986.

Systematic study Antece Dentov Emotions Was carried out by Boucher. The most extensive of these studies49

46 See Frijda, 1986.

47 Wed. Levinson, 1992.

48 Cf. Frijda, Kuipers & Tag Schure, 1986.

Frijda, Kuipers & Tag Schure, 1986.

49 See Brandt & Boucher, 1985.

Based on samples of respondents from Korea, Samoa, and the USA. A large number of narratives were collected when respondents were asked to write stories about events that evoke one of six emotions: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, sadness, and surprise. The examples selected from these stories have been translated and stripped of cultural cues and all emotional terms. A set of 144 stories was presented to respondents from three countries. Respondents indicated in each case which of the six emotions the person experienced in the story. Significant overall consistency was found in the attribution of emotions to stories, both across and within cultures. Contrary to expectations, in general, respondents Not Performed better, a test based on stories from their own cultures. This result suggests that the antecedent emotions of an event are generally quite similar across cultures. In addition, results on crying patterns and antecedent causes of crying support cross-cultural similarities50.

Cross-cultural differences in antecedents mainly related to different interpretations of situations and culture-specific beliefs. According to Mesquite (1997), such specific interpretations are not trivial when they lead to differences in subsequent emotional responses. For example, they mention situations that have signs associated with supernatural forces, only in some cultures and only there.

50 Wed. Becht, Poortinga & Vingerhoets, 2001.

LIMA Approach, Humane Hierarchy - 5 Steps to Success

classical conditioning, such as differential reinforcement of alternative behaviors, desensitization, and resistance” are all the foundations of the LIMA approach. nine0003

"LIMA" is an acronym for "least intrusive, minimally aggressive." The LIMA approach is to train horses with minimal stress. Dr. Susan Friedman ( Behaviorist, Professor of Psychology at the University of Utah ) has put together an amazingly beautiful guide for us called The Humane Hierarchy.

Today we will analyze what it is and consider step by step how to act if you encounter unwanted behavior.

The Humane Hierarchy serves as a guide for professionals in the decision-making process during learning and behavior change. In addition, it helps owners and equine professionals understand the principles to be followed when choosing training practices and methodologies, and the order in which these training practices and methodologies are to be carried out. nine0003

Step 1

Before we start training, we need to evaluate our trainees, their health, nutrition, physical and emotional well-being. Is there a reason for the unwanted behavior, or why the desired behavior does not occur or might be difficult? We want to make sure that all of these needs are met before thinking about changing behavior.

Step 2

Next we want to define antecedents (premises) - so act out. If unwanted behavior happens, how can we organize the environment so that it doesn't happen? For example, if your horse is banging on the door, can you leave the door open using other restraints? If a horse rushes at food, can you hang a slow feeder so that the food does not run out? If we want to trigger a behavior, how can we best stage it to help change it in the future? nine0003

Shona Corrin Karrash ( Positive Reinforcement Coach and Behavior Specialist) shares a funny story about a horse that didn't like stepping over white poles, so they started by digging the poles in and opening them up. In doing so, they played up the script to make it easier for the horse to reach the desired end goal. Using poles, fences, targets, previously learned behaviors, and everything else in the environment, we can help our horses figure out what we want from them and make it achievable. nine0003

In doing so, they played up the script to make it easier for the horse to reach the desired end goal. Using poles, fences, targets, previously learned behaviors, and everything else in the environment, we can help our horses figure out what we want from them and make it achievable. nine0003

Step 3

At this point we can start using positive reinforcement to actively train our horses. If we notice a desired behavior or want to reinforce it, then we use positive reinforcement (R+). We can also train an alternative behavior (not quite desirable or replacement) at this point, which helps to eliminate the possibility of undesirable behavior.

Step 4

At this point, we should be able to do whatever we need or want with our horses in any scheduled training. We must be flexible and be able to stop in time. But emergencies happen, life sometimes goes faster than learning, and we are faced with unforeseen situations in which we need to go down the scale faster than we would like. nine0003

nine0003

Step 5

At this point, we really need to stop, take a step back and understand WHY we need this behavior to be performed or interrupted, and why it needs to be done so quickly. Is it necessary for the general, emotional or physical well-being of our horse? Or is it more for our benefit?

If we decide to overlook details, make sure you've exhausted your options - you've consulted with professionals (or other professionals if you're one), you've tried distractions, and you've actually gone through all the previous steps. At this point, we can start negative reinforcement or negative punishment to increase or decrease the behavior. nine0003

Ideally, we should never use positive punishment—we know the pitfalls, we know it's not effective, we know why we should never use it, and we know the damage it does to our relationship with the horse . But if you find yourself in an unsafe situation for which you have not prepared and you NEED to apply positive punishment to protect yourself or your horse, do it.