Ptsd and anorexia

PTSD and Eating Disorders: Is There A Link?

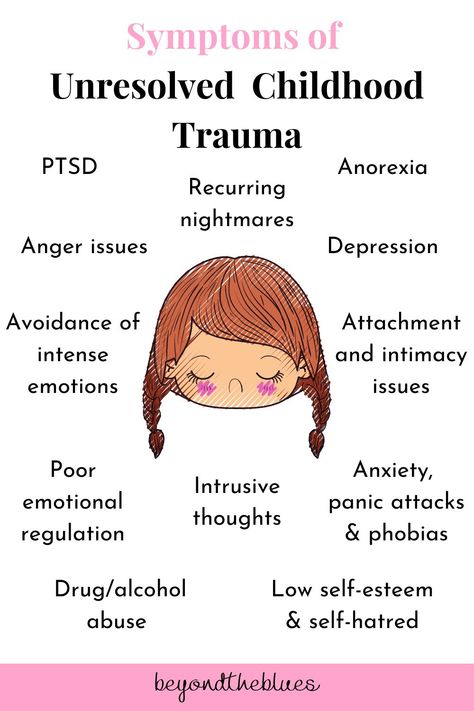

As a relatively new and still poorly recognized concept, few people come to therapy identifying as suffering from Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (C-PTSD). As a rule, a diagnosis of C-PTSD comes only after the process of self-discovery in therapy has begun. When people suffering from C-PTSD are referred to a therapist, or decide to seek help for themselves, it is usually because they are seeking help for one of its symptoms, including dissociative episodes, problems forming relationships, and alcohol or substance abuse. One of the more common issues that leads to the discovery of C-PTSD is the presence of an eating disorder, including anorexia, bulimia, and binge eating. In this article, I will explore some of the reasons why C-PTSD often manifests itself in the form of an eating disorder and what this means for successful therapy.

The impact of trauma on body-image and the victim’s relationship to food

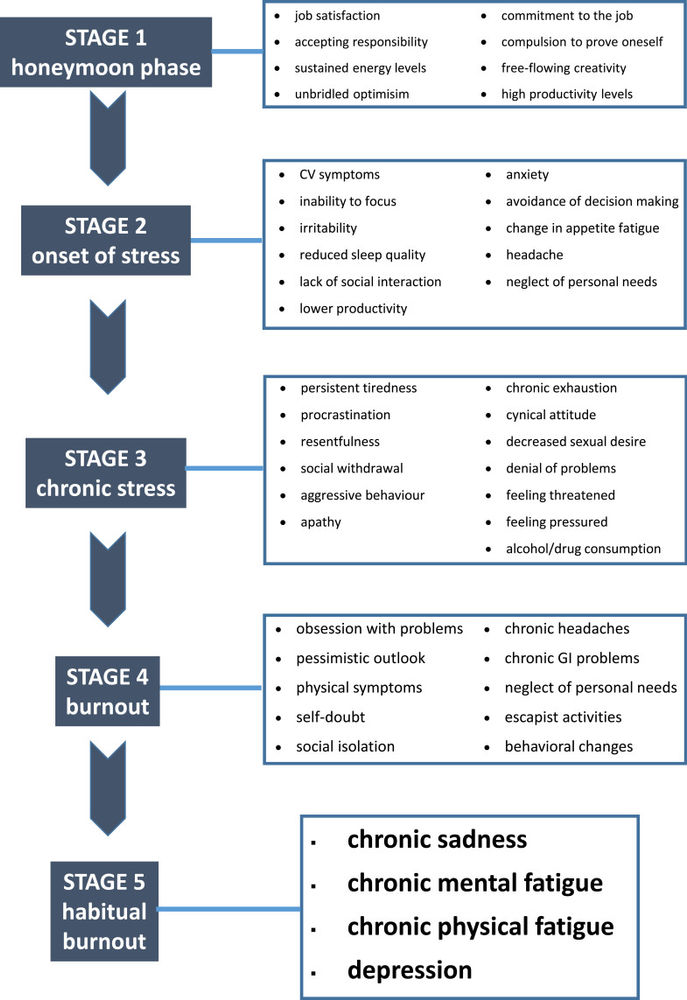

As I have discussed in previous articles, C-PTSD is similar to the better known and more thoroughly studied diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, but — as the the name suggests — is more ‘complex’. This complexity refers both to its origin and its effects. C-PTSD is the result, not of a small number of dramatic events, but rather a prolonged series of abusive events, which take place as part of a asymmetric relationship, often during childhood at the hands of a parent or stepparent. People suffering from C-PTSD show many of the the same symptoms as victims of PTSD, but on top of this, they suffer from deeper, more complex symptoms including prolonged anxiety and depression, often associated with personality disorders and especially bipolar disorder. Perhaps the most characteristic signs of complex PTSD are having a negative self-image and an inability to cope with strong feelings of anger or sadness (known as ‘affect regulation’).

The correlation (or ‘comorbidity’) between PTSD and eating disorders is well established. As with alcohol and substance abuse, the relationship between PTSD and eating disorders appears to be largely related to a form of ‘self-medicating’ behavior. People who have been through traumatic experiences often feel a sense of powerlessness, brought on to them by their inability to prevent the traumatic incident from happening or prevent themselves from being traumatized by it. The act of consciously starving oneself or engaging in purging in order to change one’s body shape is a method the victim uses to reassert control over his/her or own body. In addition, while engaging in these extreme forms of behavior, the victim feels a sense of relief from feelings of mental anguish not dissimilar to that which results from using drugs or alcohol. Perhaps not surprisingly, survivors of traumatic events often lurch from one form of self-medicating behavior to another, including lifestyle addictions like gambling or sex, substance use, various eating disorders, and even self-harm.

People who have been through traumatic experiences often feel a sense of powerlessness, brought on to them by their inability to prevent the traumatic incident from happening or prevent themselves from being traumatized by it. The act of consciously starving oneself or engaging in purging in order to change one’s body shape is a method the victim uses to reassert control over his/her or own body. In addition, while engaging in these extreme forms of behavior, the victim feels a sense of relief from feelings of mental anguish not dissimilar to that which results from using drugs or alcohol. Perhaps not surprisingly, survivors of traumatic events often lurch from one form of self-medicating behavior to another, including lifestyle addictions like gambling or sex, substance use, various eating disorders, and even self-harm.

With C-PTSD, the danger of falling into eating disorders is even greater. As mentioned above, people suffering from C-PTSD typically have difficulty with ‘affect regulation’, or managing strong emotions. Life for a sufferer from C-PTSD is an emotional rollercoaster with frequent and often unpredictable triggers sending him or her into extremes of anger or sadness. The urge to self-medicate is, therefore, very strong, and often uninhibited by the sort of ‘common sense’ instinct to hold back that most people develop over the course of a more healthy and secure upbringing. Another risk factor is that, as I discussed in a previous article, people with C-PTSD almost always have difficulties forming relationships as a result of having suffered prolonged abuse at the hands of a caregiver. As a rule, people who are not in fulfilling relationships are more likely to fall victim to self-destructive behaviors, both because they lack the support and mutual assistance of a committed partner and also because the pain of loneliness itself drives them to seek self-medication. Finally, the sexual abusive nature of many C-PTSD cases is also a further risk factor for eating disorders. It is well documented that victims of rape and other forms of sexual abuse are more likely to develop eating disorders, though the exact reasons for this are not clear.

Life for a sufferer from C-PTSD is an emotional rollercoaster with frequent and often unpredictable triggers sending him or her into extremes of anger or sadness. The urge to self-medicate is, therefore, very strong, and often uninhibited by the sort of ‘common sense’ instinct to hold back that most people develop over the course of a more healthy and secure upbringing. Another risk factor is that, as I discussed in a previous article, people with C-PTSD almost always have difficulties forming relationships as a result of having suffered prolonged abuse at the hands of a caregiver. As a rule, people who are not in fulfilling relationships are more likely to fall victim to self-destructive behaviors, both because they lack the support and mutual assistance of a committed partner and also because the pain of loneliness itself drives them to seek self-medication. Finally, the sexual abusive nature of many C-PTSD cases is also a further risk factor for eating disorders. It is well documented that victims of rape and other forms of sexual abuse are more likely to develop eating disorders, though the exact reasons for this are not clear.

In summary, people suffering from C-PTSD are at a high risk of developing eating disorders for the same reason that people with PTSD are with added intensifying factors caused by the additional features of Complex PTSD. In a crucial respect, however, C-PTSD is very different. When a person with PTSD seeks therapy for an eating disorder or other issue, it usually becomes clear very quickly that they have PTSD. Even if someone is not familiar with the concept of PTSD, they will usually be aware that their problems either started or worsened after an identified traumatic event. Often they will have vivid memories of this event which they struggle to escape from, and even when their memory of the event is partial or obscured, they are almost always aware of the event having happened. By contrast, C-PTSD is frequently characterized by absences of memory. Indeed, one way of understanding C-PTSD is an elaborate and self-destructive strategy by the brain to force out memories that are too painful to bear. People starting therapy will often have forgotten entire chunks of their childhood and be highly resistant to the idea that their problems are related to childhood trauma. Unfortunately, it is frequently the case that people suffering from C-PTSD move from therapy for one symptom or syndrome to another before any link is suggested to his or her childhood.

People starting therapy will often have forgotten entire chunks of their childhood and be highly resistant to the idea that their problems are related to childhood trauma. Unfortunately, it is frequently the case that people suffering from C-PTSD move from therapy for one symptom or syndrome to another before any link is suggested to his or her childhood.

Therapists who are meeting a new client with eating disorders should therefore be on the lookout for signs of C-PTSD. Since, those suffering from C-PTSD will not typically report, or even be aware of traumatic memories, more is needed than a superficial conversation about their childhood. As well being alert to traumatic memories, therapists should be alert to the absence of memories, or an unexplained reluctance on the part of the person in therapy to discuss his or her childhood. Of course, this goes against the grain of the general trend in psychotherapy in recent decades, which has been towards focusing on the ‘here and now’ and eschewing explorations of the past in favor of brief, solution-focused therapy. In many ways the discovery of C-PTSD necessitates a rethink and modification of the way we do therapy today; this is just one of them.

In many ways the discovery of C-PTSD necessitates a rethink and modification of the way we do therapy today; this is just one of them.

References

- Tagay, S., Schlottbohm, E., Reyes-Rodriguez, M. L., Repic, N., & Senf, W. (2014). Eating Disorders, Trauma, PTSD and Psychosocial Resources. Eating Disorders, 22(1), 33–49. http://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2014.857517

- Backholm, K., Isomaa, R., & Birgegård, A. (2013). The prevalence and impact of trauma history in eating disorder patients. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 4, 10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.22482. http://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v4i0.22482

- Mason, S. M., Flint, A. J., Roberts, A. L., Agnew-Blais, J., Koenen, K. C., & Rich-Edwards, J. W. (2014). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and food addiction in women, by timing and type of trauma exposure. JAMA Psychiatry, 71(11), 1271–1278. http://doi.org/10.

1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1208

1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1208

- McCauley, J. L., Killeen, T., Gros, D. F., Brady, K. T., & Back, S. E. (2012). Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Co-Occurring Substance Use Disorders: Advances in Assessment and Treatment. Clinical Psychology : A Publication of the Division of Clinical Psychology of the American Psychological Association, 19(3), 10.1111/cpsp.12006. http://doi.org/10.1111/cpsp.12006

- Ford, J. D., & Courtois, C. A. (2014). Complex PTSD, affect dysregulation, and borderline personality disorder. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 1, 9.

- Sar, V. (2011). Developmental trauma, complex PTSD, and the current proposal of DSM-5. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 2, 10.3402/ejpt.v2i0.5622. http://doi.org/10.3402/ejpt.v2i0.5622

Eating Disorders and Trauma / PTSD Co-Occurring Issues

Having a history of trauma is a risk-factor that makes one more vulnerable to eating disorder behaviors. Understanding this relationship is important for eating disorder identification, treatment, and recovery.

Understanding this relationship is important for eating disorder identification, treatment, and recovery.

What is Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)?

Post-Traumatic Stress disorder, also known as “PTSD,” is a commonly-used term, however, it is often used incorrectly. Many use PTSD to casually refer to having an emotional response to something that was difficult or emotionally scarring for them. The reality of what PTSD is for those that suffer from it is anything but casual and can debilitate an individual to the degree that it severely impacts their life.

PTSD Definition According to DSM-5

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Illness, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) specifies the symptoms that indicate an individual’s trauma experience has severely impacted their mental health to the degree that it warrants a diagnosis. This criteria is quite long and, therefore, will not be detailed here, however, it is important to clarify the essential features required for diagnosis.

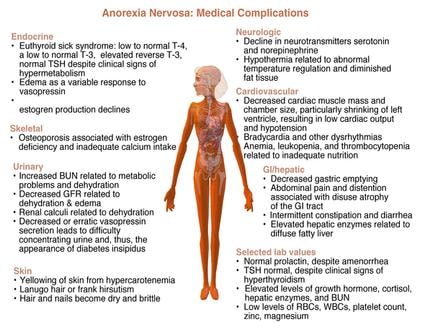

The DSM-5 denotes that PTSD is characterized by the development of characteristic symptoms following exposure to one or more traumatic events [1]. The individual often experiences intrusion symptoms such as distressing memories, dreams, and/or flashbacks associated with the traumatic event(s) that begin after the event(s) occurred [1]. These distressing symptoms can cause the individual to become emotionally dysregulated, however, they may also become dysphoric and dissociate. Individuals will often alter their entire daily lifestyle to avoid stimuli associated with the traumatic event(s).

As a result of the traumatic event(s), individuals with PTSD will often develop negative beliefs about themselves or the world (e.g. “no one can be trusted” or “I am bad”) [1]. They may struggle with memory impairment related to the event due to dissociative amnesia and will likely experience a persistent negative emotional state and inability to experience positive emotions. Individuals with PTSD are often hypervigilant and reactive to any stimuli related to their trauma.

These symptoms must be present for more than one month and must cause clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupational, or other important areas of functioning to meet criteria for full diagnosis of PTSD [1].

PTSD ICD-10 Code

To communicate a PTSD diagnosis worldwide regardless of cultural or geographic differences in terminology, the International Classification of Disease, or ICD-10, Code is F43.10.

The following indicate an individual may be struggling with PTSD:

- Dreams/memories of the trauma that cause distress.

- Dissociative reactions (Flashbacks) in which the individual feels or acts as if the traumatic event(s) were recurring.

- Intense/prolonged psychological and/or physical distress at exposure to internal or external cues that symbolize or resemble an aspect of the traumatic event(s).

- Inability to remember an important aspect of traumatic event(s).

- Persistent and exaggerated negative beliefs about oneself, others, and/or the world.

- Distorted cognitions about the cause or consequences of event(s) that lead the individual to blame themselves.

- Persistent negative emotional state.

- Inability to experience positive emotions.

- Diminished interest in significant activities.

- Detachment or estrangement from others.

- Irritable behavior and angry outbursts.

- Reckless or self-destructive behavior.

- Hypervigilance.

- Exaggerated startle response.

- Difficulty concentrating.

- Sleep disturbance.

- Increased self-harming behaviors and/or suicidal ideation.

What is an Eating Disorder?

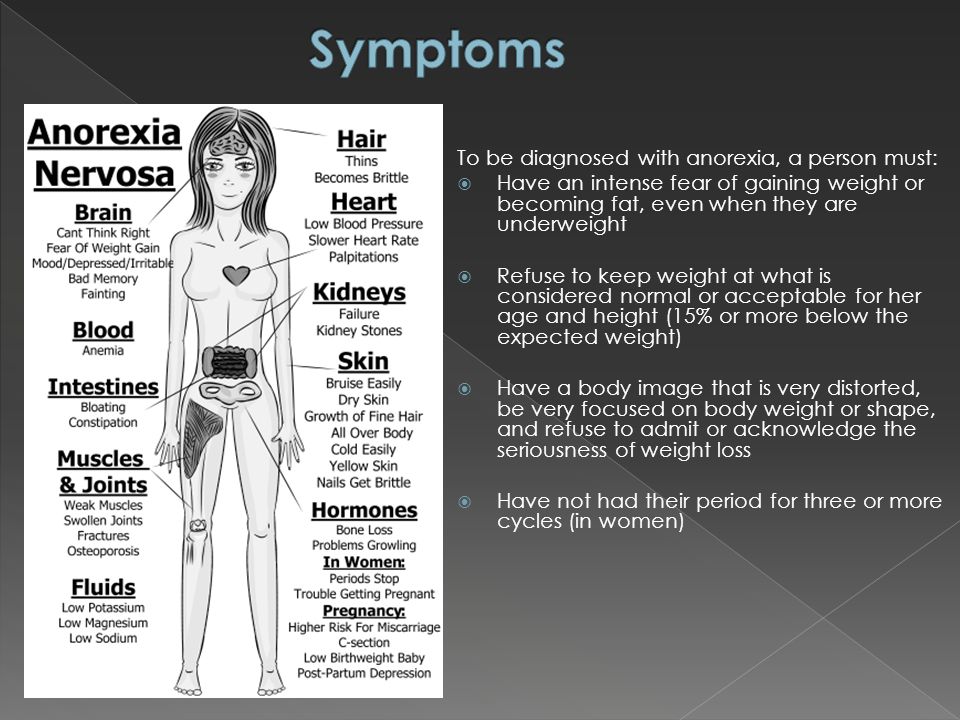

Eating disorders are characterized by a persistent disturbance of eating or feeding-related behavior that leads to altered consumption or absorption of food. These disorders cause serious impairment in every area of an individual’s life such as their physical health, mental wellness, relationships, job/school performance, etc.

Types of Eating Disorders

Approximately 30 million Americans struggle with at least one of the following feeding and eating disorders:

- Anorexia Nervosa

- Bulimia Nervosa

- Binge Eating Disorder (BED)

- Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder (ARFID)

- Pica

- Rumination Disorder

- Other Specified Feeding or Eating Disorder (OSFED).

PTSD and Eating Disorder Behaviors

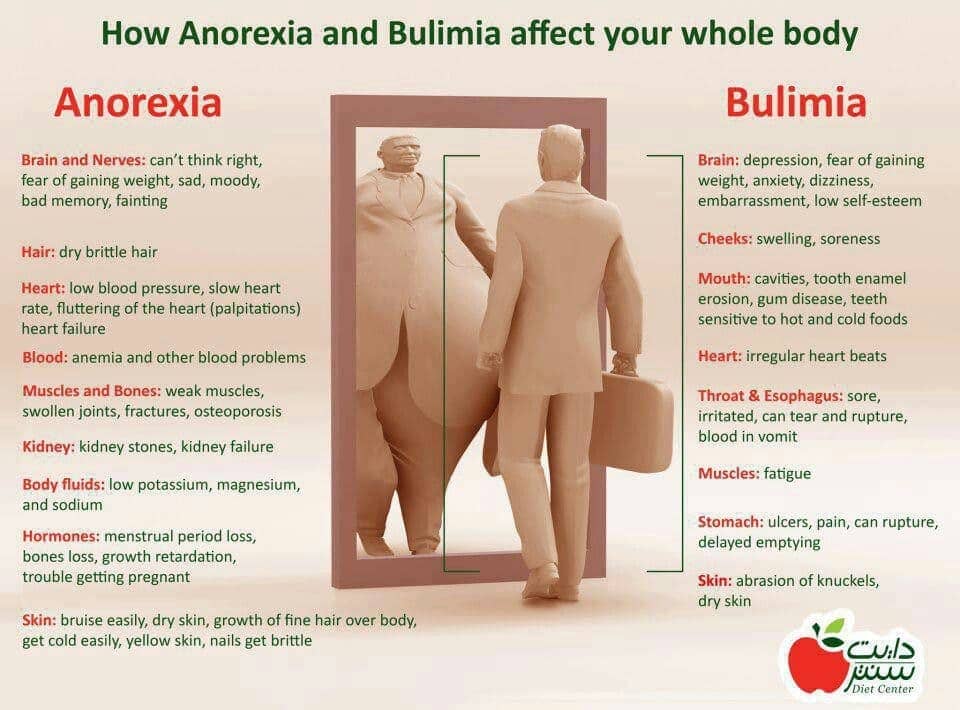

PTSD and eating disorders are absolutely related to one another and are often seen to be co-occurring. At least 52% of those with an eating disorder diagnosis have a history of trauma [2]. Eating disorders are often developed as maladaptive coping skills. Additionally, risk factors for eating disorder development are often PTSD symptoms such as having difficulty regulating emotions, negative self-view, feelings of shame, and negative emotion-states.

Can PTSD Cause Eating Disorders?

While PTSD and eating disorders often co-occur, the direction of this relationship can go either way. Some individuals may struggle with PTSD and utilize eating disorder behaviors as maladaptive coping skills, attempts to gain feelings of control, or attempts to disconnect from or punish the body. Conversely, it is also possible that an individual with an eating disorder can be more vulnerable to trauma events because of their disorder. For example, an individual engaging in “drunkorexia” behaviors becomes more likely to lose control and/or consciousness while drinking due to malnourishment and is more vulnerable to being the victim of a crime. Additionally, some individuals with an eating disorder are severe enough to warrant inpatient hospitalization and tube feeding for medical stabilization and may even experience severe health complications that bring them close to death, which can cause a trauma response afterward.

Additionally, some individuals with an eating disorder are severe enough to warrant inpatient hospitalization and tube feeding for medical stabilization and may even experience severe health complications that bring them close to death, which can cause a trauma response afterward.

PTSD and Anorexia Nervosa

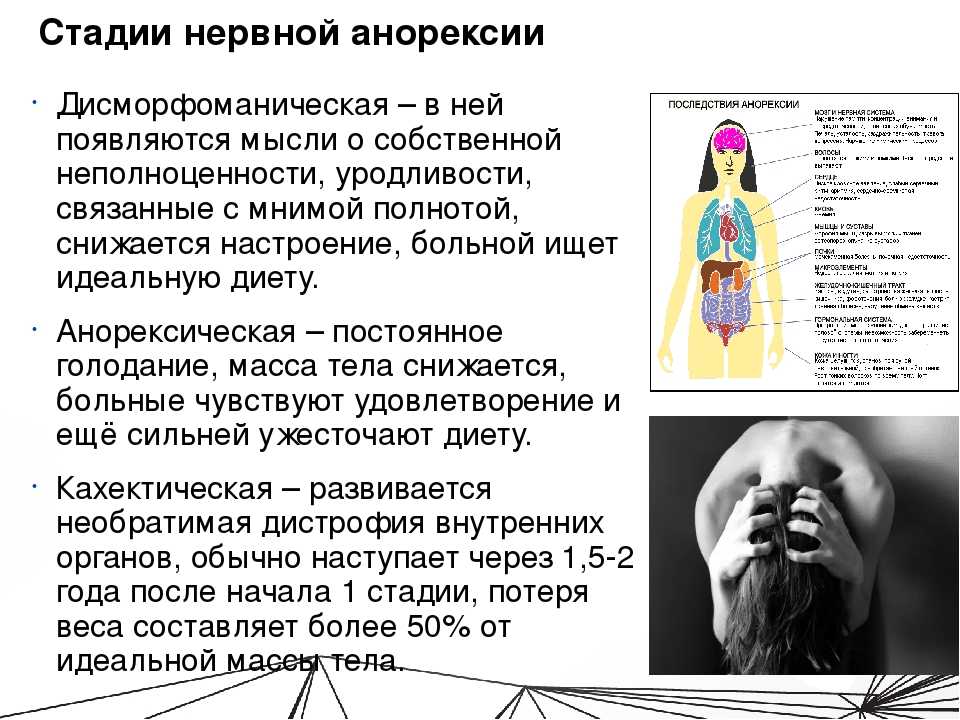

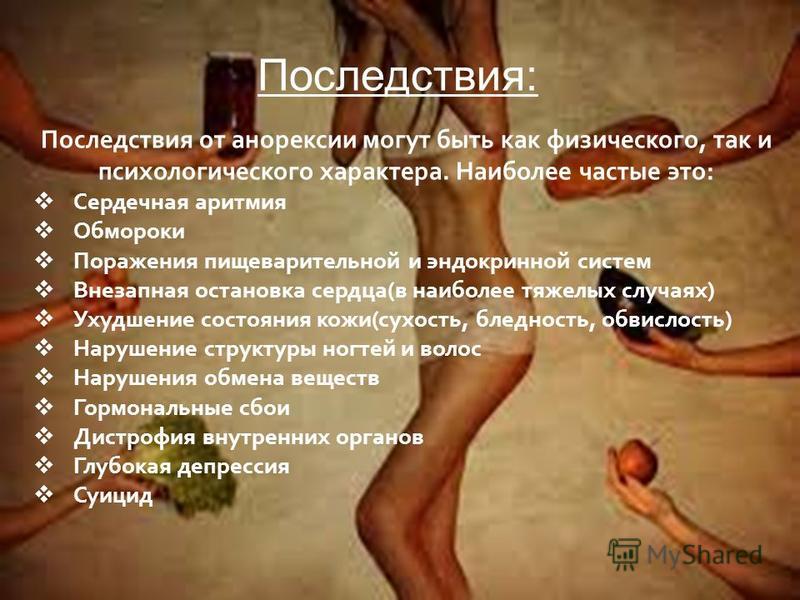

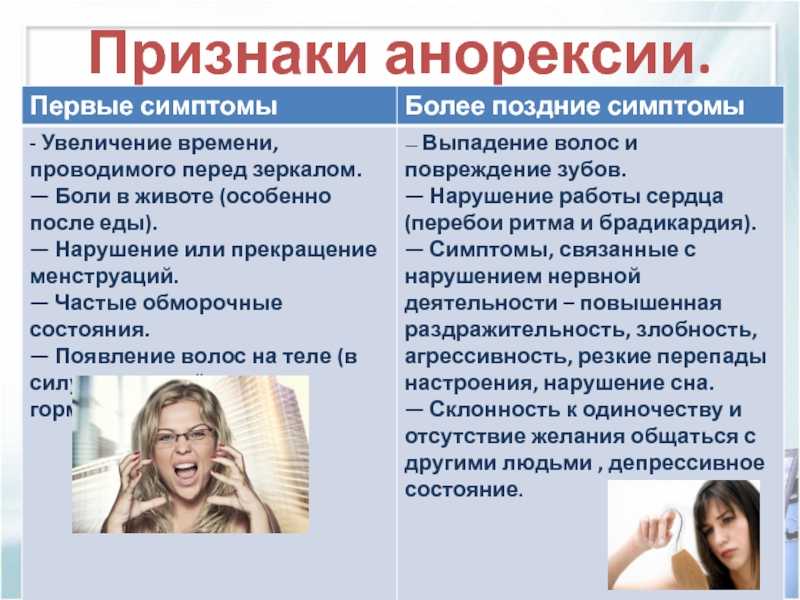

While anorexia nervosa is a serious disorder, it is actually the eating disorder that co-occurs with trauma the least [2]. Studies have found that PTSD symptoms tend to occur prior to the onset of anorexia symptoms [2]. This indicates that individuals develop anorexia behaviors after experiencing traumatic event(s), therefore, lends evidence to the fact that anorexia development occurs as an attempt to cope with or dissociate from trauma.

PTSD and Binge Eating Disorder

Approximately 26% of women with Binge Eating Disorder (BED) meet criteria for PTSD [3]. Both disorders are characterized by experiences of depressed or negative mood-states, low and/or negative self-worth, and difficulty regulating and coping with uncomfortable emotions. Individuals that have experienced trauma might use binge eating behaviors as a method of ineffective coping, as binge eating allows a means of disconnecting from the moment and releases neurons in the brain that create temporary euphoria. Individuals with BED and PTSD also tend to present with difficulties with impulse-control.

Individuals that have experienced trauma might use binge eating behaviors as a method of ineffective coping, as binge eating allows a means of disconnecting from the moment and releases neurons in the brain that create temporary euphoria. Individuals with BED and PTSD also tend to present with difficulties with impulse-control.

PTSD and Bulimia

Bulimia nervosa is the eating disorder that most commonly co-occurs with eating disorders, with research showing that bulimic symptoms of bingeing and purging are associated with significantly higher rates of Child Sexual Abuse (CSA) than restrictive behaviors [4]. Individuals with PTSD and Bulimia experience similar symptoms of impulse-control issues, negative self-worth, and difficulties with emotional regulation. Individuals with bulimia have reported significantly more “forgetting” of traumatic events than those with BED or without eating disorders, leading researchers to conclude that purging behaviors such as vomiting and laxative abuse, more than the bingeing behaviors, “promote avoidance, emotional blunting and numbing, and amnesia for painful traumatic memories [4]. ”

”

Interesting Facts about PTSD & Co-Occurring Eating Disorders

A great deal of research has been conducted on the relationship between PTSD and eating disorders and the following has been learned by researchers:

- Approximately 26% of those with BED have co-occurring BED [3].

- Approximately 13.7% of those with anorexia nervosa meet criteria for PTSD [2].

- Approximately 37 to 40% of those with bulimia nervosa experience co=occurring PTSD [4].

- Rates of PTSD are higher in individuals with purging behaviors than any other eating disorder behaviors [4]. Some researchers theorize that the neurological response to purging leads to feelings of euphoria which allows disconnection from trauma memories/responses, explaining this dynamic.

Co-Occurring PTSD & Eating Disorder Treatment

As with all disorders that co-occur with an eating disorder, it is best practices to treat PTSD and eating disorder psychopathology simultaneously.

Medication

There are no specific medications to treat eating disorders, however, many individuals with eating disorders find it helpful to take medication that can support their co-occurring disorders or symptoms. For example, medication that can relieve depression, anxiety, or, you guessed it, PTSD symptoms, can help the individual engage in more effective emotional regulation and coping. Medications that are FDA-approved to help treat PTSD symptoms include:

- Selective Serotonin Reuptake Inhibitors (SSRIs): The American Psychological Association reports that SSRIs have the current strongest evidence base for their use as treatment for PTSD symptoms [5]. The only FDA-approved SSRIs to treat PTSD are:

- Sertraline (Brand name – Zoloft) [5].

- Paroxetine (Brand name – Paxil) [5].

- NOTE: Fluoxetine (Brand Name – Prozac) is an SSRI that is occasionally used to treat PTSD, however, the FDA has not approved it for treating this disorder [5].

Many individuals report usage of other antidepressant medications, such as Venlafaxine (Brand Name – Effexor) can be helpful in reducing PTSD symptoms, however, these are not approved by the FDA to treat PTSD symptoms. However, it is worth noting that reduction of depressive symptoms can help to reduce both PTSD and eating disorder symptoms. As such, talking to your doctor about medications that can reduce eating disorder/PTSD-triggering symptoms could help to treat PTSD and eating disorders.

Therapy

The most effective method for treating co-occurring PTSD and eating disorder symptoms involve both medication AND therapy. Therapy is incredibly important in treating trauma, as an individual must process the cognitions as well as physiological responses they have to trauma and learn how to cope with these in an effective manner without eating disorder behaviors. The most effective treatment modalities for PTSD and eating disorders are:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy with prolonged exposure.

- Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR).

- Psychodynamic Psychotherapy.

- Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT) [4].

It is important to note that CBT is the most evidence-based treatment for eating disorders, however, it must be adapted to include stress inoculation training and prolonged exposure in order to be effective in treating both the eating disorder and PTSD simultaneously [4].

Relapse Prevention & Aftercare Support

Overcoming experiences of trauma as well as eating disorder behaviors is likely something that an individual will need to work on their entire lives. This does not mean severity level will not reduce over time. There may come a day when the individual is barely impacted by their previous PTSD and eating disorder struggles at all. Even so, it is important that individuals always maintain awareness of their relationship with their trauma and eating disorder and how this is impacting their daily life. It is also important to consistently seek mental health support through therapy when necessary to maintain mental wellness and recovery. For some, this means consistently engaging in weekly therapy, for others, this may mean reducing sessions to quarterly check-ins. Whatever works best for your wellness is most appropriate, however, do not be afraid to accelerate visits as necessary during challenging times.

For some, this means consistently engaging in weekly therapy, for others, this may mean reducing sessions to quarterly check-ins. Whatever works best for your wellness is most appropriate, however, do not be afraid to accelerate visits as necessary during challenging times.

Author: Margot Rittenhouse, MS, LPC, NCC

Last updated on November 4, 2021 and reviewed by: Jacquelyn Ekern, MS, LPC

Related Reading

- Abuse, Trauma, and Eating Disorders

- Art Therapy for ED Sufferers Recovering from Trauma

- CBT Offers Hope for Trauma Victims of All Ages

- Co-occurring Borderline Personality Disorder and Eating Disorders

- Eating Disorders, Trauma & Mindfulness

- Emotional Abuse and Body Image

- Expressive Therapies for Trauma and Eating Disorders: Research is On Your Side

- Healing from Trauma and Setting Boundaries in Relationships

- How Treatment Programs Address Co-occurring Issues like PTSD

- Injury, Trauma and Eating Disorders

- Movement Therapy for Trauma Recovery

- PTSD as a Co-Occurring Issue with Eating Disorders

- Recovering from Neglect, Repairing Body Image

- Recovering From Trauma and Rebuilding Body Image

- Self-Soothing Techniques when Feeling Traumatized

- Sexual Abuse and Body Image

- The Power of Treating Eating Disorders and Trauma Simultaneously

- Trauma – How to Walk the Road of Recovery Amidst the Difficulties of Life

- Trauma and Depression: What is the Connection with Eating Disorders?

- Trauma: How Does This Put an Individual at Risk for Co-occurring Disorders?

© Copyright 2022 Eating Disorder Hope. All Rights Reserved. Sitemap.Privacy Policy.Terms of Use.

All Rights Reserved. Sitemap.Privacy Policy.Terms of Use.

MEDICAL ADVICE DISCLAIMER: The service, and any information contained on the website or provided through the service, is provided for informational purposes only. The information contained on or provided through this service is intended for general consumer understanding and education and not as a substitute for medical or psychological advice, diagnosis, or treatment. All information provided on the website is presented as is without any warranty of any kind, and expressly excludes any warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose.

Call a specialist at Within Health for help (advertisement)

(855) 597-1992

PTSD and eating disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and eating disorders often co-occur. People may have other mental illnesses such as generalized anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, or obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

Contents

What is PTSD?

Up to latest edition Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th edition (DSM-5), PTSD was included in the DSM category of anxiety disorders. In 2013, the diagnosis of PTSD was moved to a new category called trauma and stress.

In 2013, the diagnosis of PTSD was moved to a new category called trauma and stress.

PTSD is diagnosed when a person experiences a traumatic event and then experiences great difficulty after the event. The traumatic incident continues to dominate their daily lives. A diagnosis of PTSD requires a person to have symptoms, which may include upsetting and intrusive flashbacks, nightmares, avoidance of reminders of the event, negative thoughts or feelings associated with the event, difficulty concentrating, persistent anxiety, and increased physiological arousal after developments. These symptoms must persist for a month or more. nine0003

What are eating disorders?

Most common:

- Eating disorder (BED): Eating large amounts of food feeling out of control

- Bulimia nervosa: Eating large amounts of food alternating with behaviors designed to counteract the effects of this food

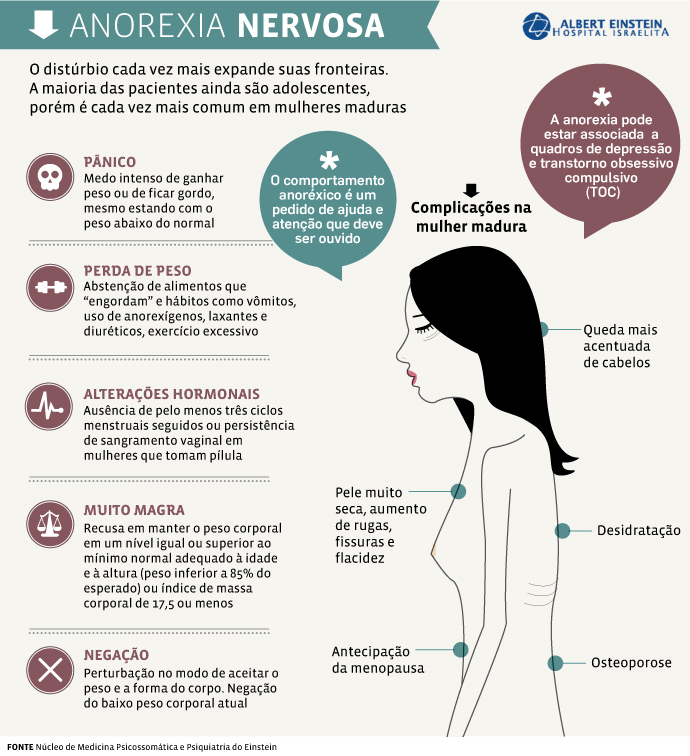

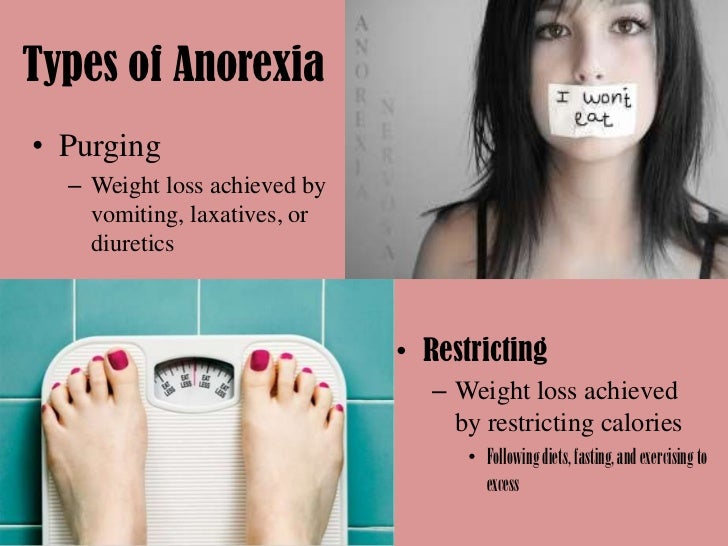

- Anorexia nervosa: insufficient nutrition for energy requirements due to fear of weight gain

These are also the three types of eating disorders that have been most frequently studied in connection with PTSD.

What is trauma?

Trauma refers to a wide range of experiences. While initially eating disorders were often studied and believed to be associated with childhood sexual abuse, the definition of trauma has been expanded to include many other forms of victimization, including other childhood sources such as emotional abuse, emotional and physical neglect, and ridicule. and bullying. and adult experiences such as rape, sexual harassment, and assault. This may also include natural disasters, car accidents, and hostilities. nine0003

Unfortunately, traumatic events are relatively common. Most people experience at least one traumatic event in their lives.

How PTSD relates to trauma

A person can develop PTSD at any age. But not every trauma survivor develops PTSD—in fact, most will be able to process the traumatic event and move on without developing the disorder.

Certain factors can increase a person's chance of developing PTSD after trauma, such as the type of trauma, the amount of trauma experienced, prior problems with anxiety and depression, poor social support, and genetic predisposition. nine0003

nine0003

Eating disorders and PTSD

Trauma, including childhood sexual abuse, is a “non-specific” risk factor for eating disorders because it can also precede a number of other psychiatric disorders. The lifetime prevalence of PTSD is estimated at 6.4 percent. The frequency of PTSD among people with eating disorders is less clear because research is scarce. What studies exist show the following rates of lifelong PTSD. nine0003

- Women

- with bulimia nervosa: 37-40 percent

- with BED: 21-26 percent

- with anorexia nervosa: 16 percent

- Men

- with bulimia nervosa: 66 percent

- with BED: 24 percent

The incidence of PTSD tends to be higher in cases of eating disorders with binge eating and purging symptoms, including the anorexia-seizure/purging subtype. nine0003

nine0003

There are various theories regarding the higher incidence of PTSD among people with eating disorders. One theory is that trauma directly affects body image or sense of self and encourages a person to try to change the shape of their body in order to avoid future harm.

Another reason is that exposure to trauma leads to emotional dysregulation (difficulty in managing emotional responses), which in turn can increase the risk for various types of psychopathology, including PTSD, borderline personality disorder, and others associated with psychoactive use. substances. In this model, binge eating and purging is considered an attempt by the sufferer to cope with their intense PTSD symptoms. nine0003

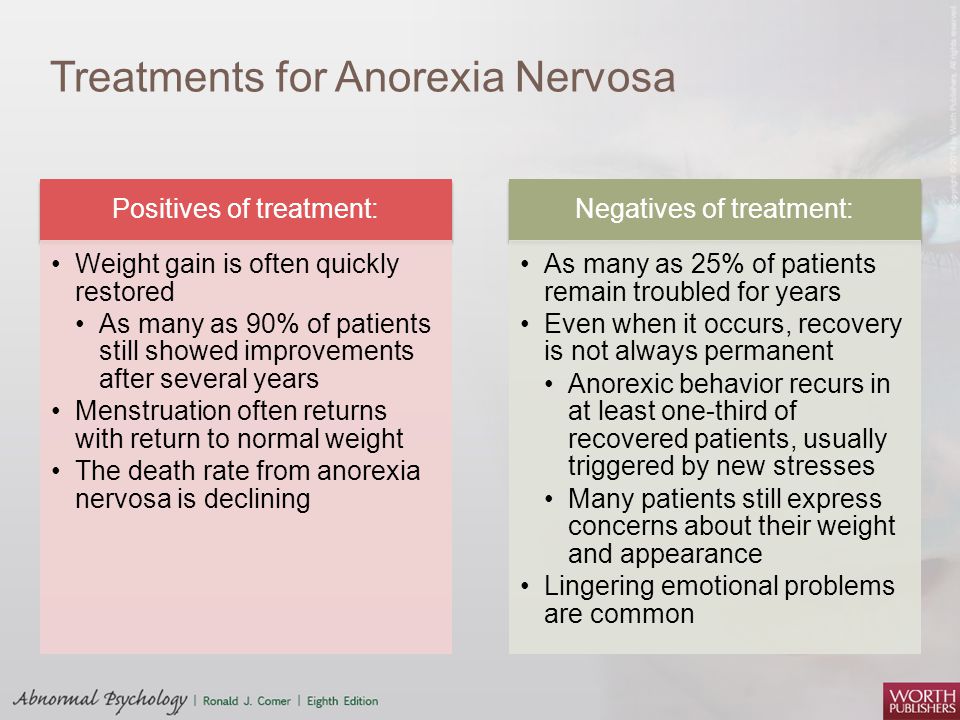

Psychological treatment

In any case, when multiple psychiatric conditions occur, treatment becomes more complex. This can certainly be true in PTSD and eating disorders. Treatment often involves taking direction around food intake, so the PTSD patient's reluctance to trust a caregiver can be problematic.

There are several specific clinical guidelines for the treatment of patients with PTSD and eating disorders. Fortunately, there are effective methods. Can be successfully treated with cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which focuses on understanding the relationship between thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. nine0003

Psychotherapy is the leading treatment for PTSD. Some of the leading evidence-based methods include:

- Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT) teaches you how to redefine your maladaptive beliefs about trauma.

- Extended Exposure (PE) Therapy teaches how to confront feelings and includes talking about trauma.

- Trauma Focused CBT (TF-CBT) is designed for children and adolescents and teaches how to understand, process and cope with trauma. nine0024

- Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) helps process and understand trauma while performing guided eye movements.

This treatment tends to be more controversial because it is not clear if eye movements make any contribution to improving patients beyond the exposure process.

This treatment tends to be more controversial because it is not clear if eye movements make any contribution to improving patients beyond the exposure process.

Psychotherapy is also an advanced treatment for eating disorders. Advanced Cognitive Therapy (CBT-E) is the most evidence-based protocol for the treatment of eating disorders in adults. It focuses on changing behavior, which in turn helps to challenge problematic thoughts. nine0003

If the patient is medically unstable due to an eating disorder, it should probably be treated first until these problems improve. Sometimes treating one condition can help make another treatment more effective.

However, one problem with sequential action is that treating one disorder can sometimes worsen another. This can cause a self-perpetuating cycle that prevents recovery from both disorders. If the patient is confronted with painful memories of the trauma, they may reinforce the behavior to avoid feeling negative emotions, and this avoidance helps to keep their PTSD alive. In contrast, concurrent treatment may be effective in addressing both problems at the same time, but there is no single treatment protocol. nine0003

In contrast, concurrent treatment may be effective in addressing both problems at the same time, but there is no single treatment protocol. nine0003

Another decision in treatment planning is which of the above evidence-based treatments for PTSD should be used. The results were fairly similar among the four treatments, and no study indicated which might be most effective for people with PTSD and eating disorders. Some experts point out that CPT may be most closely related to CBT-E, so a combination treatment may combine aspects of both. nine0003

For patients with a lot of emotional dysregulation and high-risk behavior problems, one form of Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), a treatment protocol for PTSD, is DBT-PE. It combines long-term effects with DBT.

Criteria for when to start PTSD therapy:

- The patient indicates willingness.

- Eats adequately and can process information.

- Eating disorder symptoms relatively under control. nine0024

- Demonstrates adequate ability to tolerate negative feelings.

Patients with PTSD and eating disorders should undergo a comprehensive assessment. Some may not be comfortable identifying traumatic events early in treatment, so assessment should be an ongoing process. Their therapist should develop a case statement that will help them understand the relationship between the eating disorder and PTSD.

PTSD and eating disorders

home PTSDPTSD and eating disorders

June 16, 2022

Eating behavior can change dramatically due to stress or specific traumatic events. Of course, war is one of those. Sometimes even those who are in relative safety "jam the war." nine0003

Why is that?

Acute stress suppresses appetite. After the signal is received, adrenaline is released into the body - blood circulation improves, blood pressure rises, and the heartbeat quickens. While the work of the digestive system slows down, because it interferes with fast reactions. There is no desire at all.

While the work of the digestive system slows down, because it interferes with fast reactions. There is no desire at all.

After the endured danger, when we feel relative safety, we need to recuperate. At this time, cortisol is released, which increases appetite. When the stress wears off, cortisol levels usually drop back to normal levels. nine0003

But if the stress lasts for a long time, as we have now, the body constantly maintains elevated levels of cortisol. Accordingly, the appetite may remain enhanced.

At the same time, people with eating disorders have a higher incidence of post-traumatic stress disorder. Detailed information about PTSD can be found in a separate article.

Relationship between PTSD and eating disorders

At least 52% of people diagnosed with an eating disorder were injured at the time.

There are usually four categories of eating disorders, but combinations of these can occur.

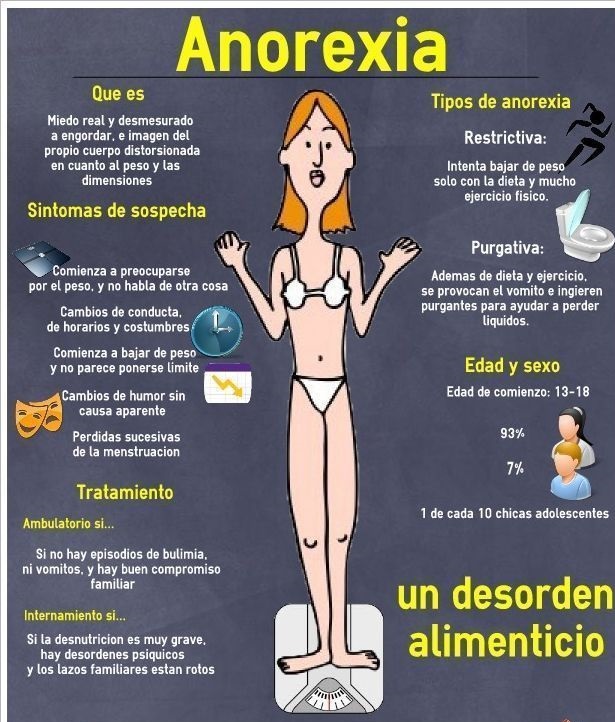

- Anorexia nervosa - when someone is afraid of gaining weight and eats too little.

- ARFID. People with this disorder have no interest in food, have sensory problems with taste, smell, or texture, or worry about not feeling well after eating. nine0024

- Bulimia nervosa - overeating due to psychological factors, after which the body is cleansed by vomiting. At the same time, there is an excessive dependence of self-importance on weight or body shape.

- Binge eating disorder (BED) - when someone eats a large amount of food in a short time, feeling that they cannot stop it due to increased anxiety.

- OSFED (other specified feeding or eating disorder - other specific eating or eating disorders)

PTSD and eating statistics

- Men with bulimia nervosa have a 66% greater risk of post-traumatic stress disorder than others.

- Approximately 37 to 40% of people with bulimia nervosa experience comorbid PTSD.

- Approximately 26% of women with binge eating disorder have other criteria for PTSD. nine0024

- Approximately 23% of people with anorexia nervosa have other criteria for PTSD.

- 11.8% of women with other types of eating disorders also have other PTSD symptoms.

- Among patients treated for inpatient eating disorders, up to 52% of had other PTSD symptoms.

Can PTSD cause eating disorders

Spoiler: "Yes!".

-

Trauma can create a negative image of one's own body or self-image. It also happens that people blame themselves and their appearance for what happened to them. If so, then a person with PTSD may use food as a way to change their body, a defense mechanism, or to reduce self-hatred.

-

Anorexia can be a way to express your anger and a way to distract yourself from painful emotions.

nine0023

nine0023 It is like a desire to hide, hide yourself from others and disappear.

-

In some cases, people experience eating disorders as a way of coping with painful experiences. Both PTSD and eating disorders have high rates of dissociation—feelings of being disconnected from oneself. It is possible that people with both disorders are trying to use their eating habits as a means to turn off or silence traumatic memories and emotions. nine0003

PTSD and eating disorders often occur at the same time, but it can be different. Some people may struggle with PTSD by using eating disorders as coping skills, trying to gain a sense of control, or trying to disconnect from or punish the body.

Conversely, a person with an eating disorder may be more vulnerable to injury. For example, some people with an eating disorder are so severe that they require inpatient hospitalization and tube feeding to stabilize the condition. Such serious health complications can cause a more acute reaction to injury.

nine0003

nine0003

Features of therapy

Finding the psychological causes of eating disorders is vital to effective treatment and support. Therefore, if PTSD plays a role in the eating disorder, it should be addressed as soon as possible to ensure recovery.

If you or someone you know feels that the injury has a lot to do with food, it's important to get help as soon as possible. nine0003

Among the methods of treatment for PTSD, the following psychological methods are recommended - trauma-oriented cognitive-behavioral therapy and the method of desensitization and processing through eye movements.

Popular treatments

There is no single standard treatment for eating disorders in PTSD.

You must understand that the road to recovery can be long and difficult.

The assistance program may include the following treatments:

- Comprehensive examination, provision of information and coordination of the care plan.