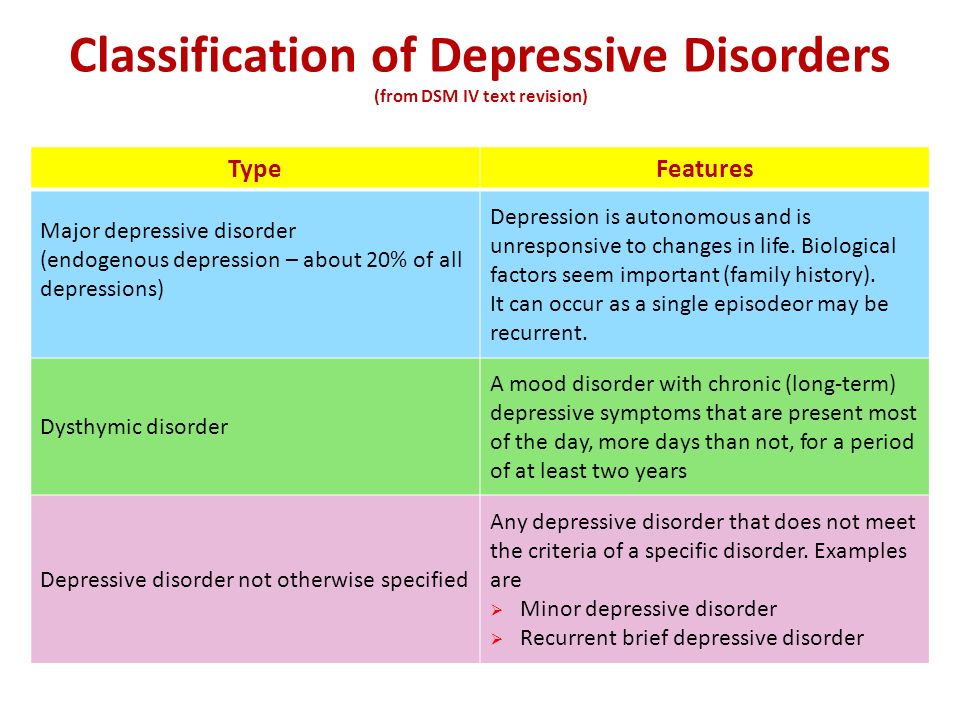

Mdd with psychosis

Major Depressive Disorder with Psychotic Features May Lead to MisDiagnosis of Dementia: A Case Report and Review of the Literature

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

- PMC3572511

J Psychiatr Pract. Author manuscript; available in PMC 2013 Feb 14.

Published in final edited form as:

J Psychiatr Pract. 2011 Nov; 17(6): 432–438.

doi: 10.1097/01.pra.0000407968.57475.ab

PMCID: PMC3572511

NIHMSID: NIHMS350803

PMID: 22108402

, MD, PhD,a, PhD,b,c, MD,a and , MD, MSa

Author information Copyright and License information Disclaimer

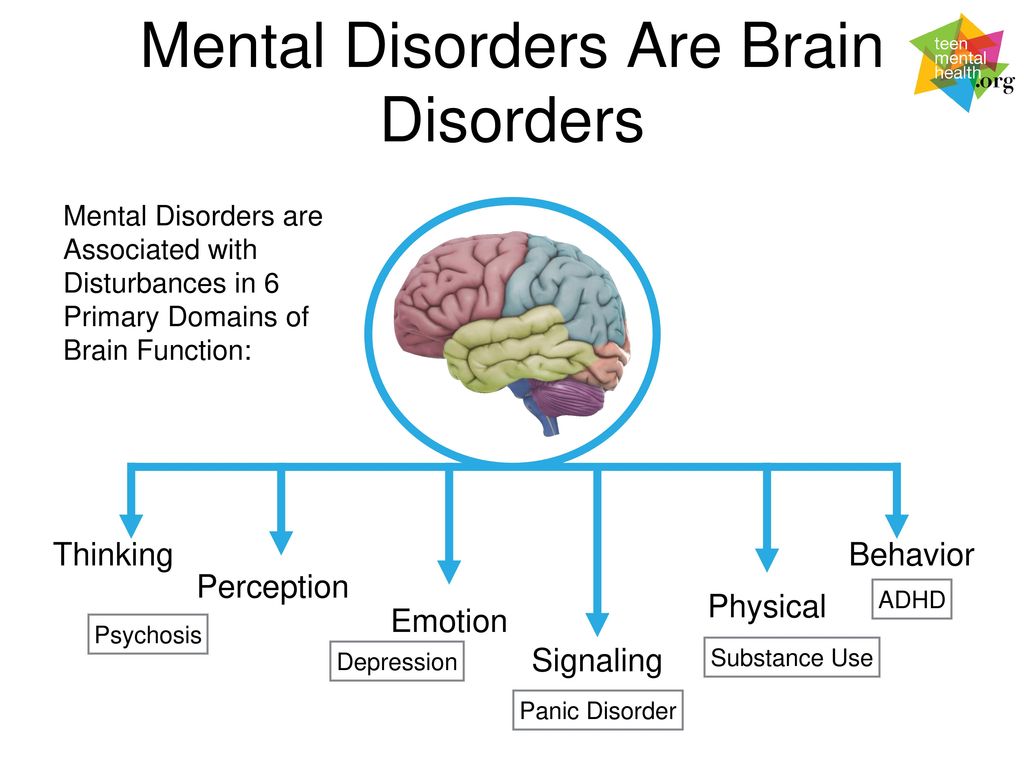

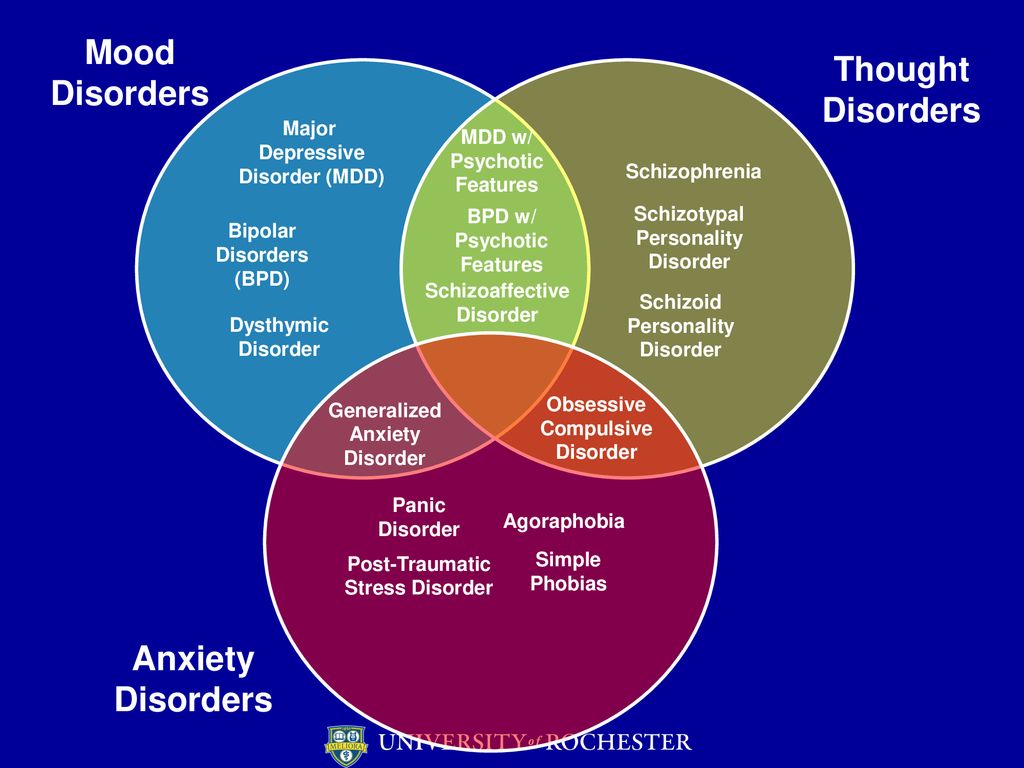

Major depressive disorder (MDD) with psychotic features is relatively frequent among patients with greater depressive symptom severity and is associated with a poorer course of illness and more functional impairment than MDD without psychotic features.

Multiple studies have found that patients with psychotic mood disorders demonstrate significantly poorer cognitive performance in a variety of areas than those with nonpsychotic mood disorders. The Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) and the Dementia Rating Scale (DRS-2) are widely used to measure cognitive functions in research on MDD with psychotic features. Established total raw score cut-offs of 24 on the MMSE and of 137 on the DRS-2 in published manuals suggest possible global cognitive impairment and dementia, respectively. Limited research is available on these suggested cut-offs for patients with MDD with psychotic features. We document the therapeutic benefit of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which is usually associated with short-term cognitive impairment, in a 68-year-old woman with psychotic depression whose MMSE and DRS-2 scores initially suggested possible global cognitive impairment and dementia. Over the course of four ECT treatments, this patient’s MMSE scores progressively increased.

After the second ECT treatment, the patient no longer met criteria for global cognitive impairment. With each treatment, depression severity, measured by the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, improved sequentially. Thus, the suggested cut-off scores for the MMSE or DRS-2 in patients with MDD with psychotic features may in some cases produce false-positive indications of dementia.

After the second ECT treatment, the patient no longer met criteria for global cognitive impairment. With each treatment, depression severity, measured by the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression, improved sequentially. Thus, the suggested cut-off scores for the MMSE or DRS-2 in patients with MDD with psychotic features may in some cases produce false-positive indications of dementia.

Keywords: major depressive disorder, psychotic features, dementia, pseudodementia, Mini-Mental State Examination, Dementia Rating Scale

Background

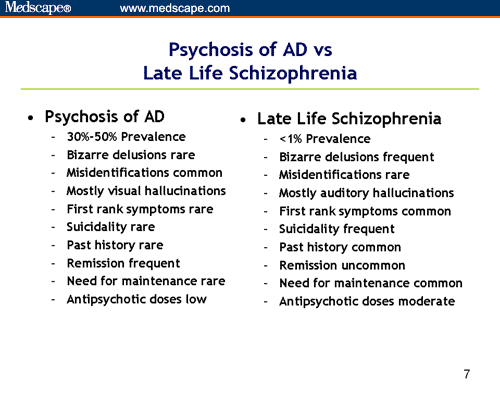

Major depressive disorder (MDD) with psychotic features is a distinct type of depressive illness in which mood disturbance is accompanied by either delusions, hallucinations, or both. Psychotic features occur in nearly 18.5% of patients who are diagnosed with MDD.1 The prevalence of MDD with psychotic features increases with age. Over 20 years of research suggests that patients with psychotic features are more likely to have treatment-resistant depression compared with counterparts who did not have psychotic symptoms associated with their depression. 2,3 Patients with psychotic depression have a greater number of suicide attempts, longer duration of illness, more Axis II diagnoses, and more motor disturbances than those with psychotic features. It is also important to note that patients with MDD with psychotic features have greater overall functional impairment and higher relapse rates than those without psychotic features.4,5 In addition, geriatric patients with psychotic depression have been found to have more pronounced brain atrophy, higher relapse rates, and greater mortality compared with geriatric patients without delusions or hallucinations.6 Earlier research found that cognitive function was significantly impaired in patients with psychotic major depression compared with patients with nonpsychotic MDD and healthy comparison subjects.7

2,3 Patients with psychotic depression have a greater number of suicide attempts, longer duration of illness, more Axis II diagnoses, and more motor disturbances than those with psychotic features. It is also important to note that patients with MDD with psychotic features have greater overall functional impairment and higher relapse rates than those without psychotic features.4,5 In addition, geriatric patients with psychotic depression have been found to have more pronounced brain atrophy, higher relapse rates, and greater mortality compared with geriatric patients without delusions or hallucinations.6 Earlier research found that cognitive function was significantly impaired in patients with psychotic major depression compared with patients with nonpsychotic MDD and healthy comparison subjects.7

The term “depressive pseudodementia” continues to be a popular clinical concept, although it has not been incorporated as an individual nosologic category in any classification system. Depressive pseudodementia has been defined as cognitive impairment caused by depression, usually in the elderly, that to some degree resembles other forms of dementia and is at least partially reversible with treatment.8 Published reports indicate that clinically depressed patients who present with pseudodementia are at increased risk for “true” dementia as early as 2 years after their initial presentation.9,10 A recent study investigating the long-term outcome of depressive pseudodementia in elderly patients revealed that reversible cognitive impairment in late-life depression is a strong predictor of ensuing dementia.11

Depressive pseudodementia has been defined as cognitive impairment caused by depression, usually in the elderly, that to some degree resembles other forms of dementia and is at least partially reversible with treatment.8 Published reports indicate that clinically depressed patients who present with pseudodementia are at increased risk for “true” dementia as early as 2 years after their initial presentation.9,10 A recent study investigating the long-term outcome of depressive pseudodementia in elderly patients revealed that reversible cognitive impairment in late-life depression is a strong predictor of ensuing dementia.11

The standard of care for treating psychotic depression consists of either combination pharmacologic therapy involving an antidepressant and an antipsychotic, or ECT.12 Depressed patients with psychosis have a poorer response to monotherapy with selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) than patients with nonpsychotic depression. 13 In the mid-1980s, studies showed that only one third of patients with psychotic depression recovered when treated with an antidepressant agent only, compared with one half of such patients who were treated with an antipsychotic agent only. In contrast, two thirds of patients with psychotic depression recovered when they were treated with either ECT or a combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic agent.

14 Moreover, numerous studies have shown that ECT treatments with bilateral or right unilateral electrode configuration can be superior to combination drug therapy in the treatment of psychotic depression.15 A large multicenter, randomized trial investigated the efficacy of bilateral ECT in nonpsychotic depression versus psychotic depression and found a remission rate of 95% in patients with psychotic depression compared with an 83% remission rate in patients with nonpsychotic depression.16

13 In the mid-1980s, studies showed that only one third of patients with psychotic depression recovered when treated with an antidepressant agent only, compared with one half of such patients who were treated with an antipsychotic agent only. In contrast, two thirds of patients with psychotic depression recovered when they were treated with either ECT or a combination of an antidepressant and an antipsychotic agent.

14 Moreover, numerous studies have shown that ECT treatments with bilateral or right unilateral electrode configuration can be superior to combination drug therapy in the treatment of psychotic depression.15 A large multicenter, randomized trial investigated the efficacy of bilateral ECT in nonpsychotic depression versus psychotic depression and found a remission rate of 95% in patients with psychotic depression compared with an 83% remission rate in patients with nonpsychotic depression.16

It is very important to note that patients with psychotic depression may be excluded from controlled clinical trials because they may lack the capacity to provide informed consent. Alternatively, patients with severe psychotic, or even non-psychotic MDD, may be excluded from clinical trials because of cognitive impairment as measured by cognitive tests (depending on the study methodology). A survey of recent clinical trials in ECT uniformly showed that a diagnosis of dementia was a criterion for exclusion from study participation.17-19 This raises the question of how to operationalize the identification of dementia. In addition to a pre-existing clinical diagnosis of dementia, a possible diagnosis of dementia may be based upon a pre-defined cut-off score on a neuropsychologic instrument such as the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)20 or the second edition of the Dementia Rating Scale (DRS-2).21 Published cut-off scores on the MMSE of 24 and on the DRS-2 of 137 are used to suggest possible global cognitive impairment and dementia, respectively, and are used in clinical ECT investigations to exclude patients.

Alternatively, patients with severe psychotic, or even non-psychotic MDD, may be excluded from clinical trials because of cognitive impairment as measured by cognitive tests (depending on the study methodology). A survey of recent clinical trials in ECT uniformly showed that a diagnosis of dementia was a criterion for exclusion from study participation.17-19 This raises the question of how to operationalize the identification of dementia. In addition to a pre-existing clinical diagnosis of dementia, a possible diagnosis of dementia may be based upon a pre-defined cut-off score on a neuropsychologic instrument such as the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)20 or the second edition of the Dementia Rating Scale (DRS-2).21 Published cut-off scores on the MMSE of 24 and on the DRS-2 of 137 are used to suggest possible global cognitive impairment and dementia, respectively, and are used in clinical ECT investigations to exclude patients.

In this case report, we illustrate how the application of either the MMSE or the DRS-2 in patients with psychotic depression may identify cognitive impairment and suggest that this impairment may be related to the psychotic depression rather than a dementing illness.

Case Description

The patient was a 68-year-old Caucasian woman with a history of MDD, recurrent, severe with psychotic features, as well as anxiety disorder NOS. She presented to the emergency room (ER) with concerns that she could neither speak nor move. She was also obsessed with being unable to swallow or eat. Her husband provided most of the history, but during her initial interview in the ER, the patient was speaking without difficulty. She reported delusions that her “tongue and legs were gone.” The patient’s husband reported that she had lost 8 pounds in the prior month due to appetite loss and that he “had to force her to eat.” The patient’s medications at the time of admission included fluoxetine (30 mg/day), aripiprazole (2.5 mg every evening), haloperidol (1 mg/day), lorazepam (1 mg three times a day), and temazepam (30 mg at bedtime). The patient was 5 feet, 4 inches tall and weighed 175 pounds (body mass index of 30.0).

The patient’s first major depressive episode (MDE) occurred at the age of 59, and her husband reported that, in the ensuing years, his wife had very few depression-free intervals. Previously unsuccessful psychopharmacologic interventions included sertraline, olanzapine, clorazepate, oxazepam, and trazodone; she had not had ECT. The patient had no current substance abuse or history of substance abuse. She had made numerous suicide attempts, mostly by overdose, for which she was hospitalized on an inpatient psychiatry unit both in 2001 and 2002. Family history was notable for a brother with longstanding depression who had received ECT. Her medical evaluation revealed no abnormalities. No brain imaging was done.

Previously unsuccessful psychopharmacologic interventions included sertraline, olanzapine, clorazepate, oxazepam, and trazodone; she had not had ECT. The patient had no current substance abuse or history of substance abuse. She had made numerous suicide attempts, mostly by overdose, for which she was hospitalized on an inpatient psychiatry unit both in 2001 and 2002. Family history was notable for a brother with longstanding depression who had received ECT. Her medical evaluation revealed no abnormalities. No brain imaging was done.

The most recent evaluation of the patient’s age-appropriate level of cognitive and psychosocial function occurred approximately 9 months prior to the current episode. At that time, she was still socializing with friends and able to independently cook and balance her checkbook. This euthymic interval lasted for several months before her sudden decline in cognitive function and worsening depression.

At the time of this admission, the patient was considered an appropriate candidate for ECT and was also assessed for participation in an ECT clinical trial. She was started on low-dose venlafaxine (37.5 mg/day) prior to her first ECT treatment, which was to be titrated up to a therapeutic dosage by the end of her ECT treatments. The patient received her ECT sessions three times a week (i.e., Monday, Wednesday, Friday). Her venlafaxine dosage was titrated to 75 mg in the morning and 150 mg in the evening by her fifth ECT treatment. Her MMSE scores and the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D24) scores were determined prior to each of her first five ECT treatments.22 The DRS-2 was also administered to the patient prior to her first ECT treatment.

She was started on low-dose venlafaxine (37.5 mg/day) prior to her first ECT treatment, which was to be titrated up to a therapeutic dosage by the end of her ECT treatments. The patient received her ECT sessions three times a week (i.e., Monday, Wednesday, Friday). Her venlafaxine dosage was titrated to 75 mg in the morning and 150 mg in the evening by her fifth ECT treatment. Her MMSE scores and the 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (Ham-D24) scores were determined prior to each of her first five ECT treatments.22 The DRS-2 was also administered to the patient prior to her first ECT treatment.

The DRS-2 is a commonly used test that measures cognitive functions that are affected by frontal-subcortical deficits.21 The DRS-2 is divided into five subscales that measuring attention, initiation/perseveration, construction, conceptualization, and memory; total and subscale scores are obtained. The estimated administration time of the DRS-2 is between 20 and 45 minutes. Normative data for the DRS-2 in healthy subjects showed that normal total scores on the DRS-2 range from 137 to a maximum obtainable 144, although different normative data have been obtained depending on age and education level.23 Scores below 137 indicate the presence of a dementia-like illness.

Normative data for the DRS-2 in healthy subjects showed that normal total scores on the DRS-2 range from 137 to a maximum obtainable 144, although different normative data have been obtained depending on age and education level.23 Scores below 137 indicate the presence of a dementia-like illness.

shows the patient’s baseline values for the DRS-2, MMSE, and Ham-D

24, as well as changes on the MMSE and Ham-D24 over the course of treatment. The patient’s DRS-2 raw score of 120 and subscale scores of 4 on the Age-Corrected Mayo Clinic’s Older Americans Normative Studies (MOANS) Scaled Score (AMSS)24 and 3 on the Age- and Education-Corrected MOANS Scaled Score (AEMSS), taken prior to her first ECT treatment, qualified her for a diagnosis of moderate to severe dementia ().21 The patient’s initial MMSE total score of 21, assessed prior to her first ECT treatment, also suggested that global cognitive impairment was present. However, after the patient’s first two ECT treatments, her MMSE score increased to 25. After two additional treatments, her MMSE score increased to 28, indicating a likely false positive initial determination of global cognitive impairment as the etiology of her decreased functional and delusional state. The patient’s energy, appetite, and functional state markedly improved after her first two treatments. Her expressions of nihilistic delusions were also markedly decreased in frequency. Her mood and outlook continued to improve over the course of her first four ECT treatments, as reflected by continued decreased depression severity as determined by the Ham-D24.

After two additional treatments, her MMSE score increased to 28, indicating a likely false positive initial determination of global cognitive impairment as the etiology of her decreased functional and delusional state. The patient’s energy, appetite, and functional state markedly improved after her first two treatments. Her expressions of nihilistic delusions were also markedly decreased in frequency. Her mood and outlook continued to improve over the course of her first four ECT treatments, as reflected by continued decreased depression severity as determined by the Ham-D24.

Table 1

Scores on MMSE, DRS-2, and Ham-D24 over the course of ECT

| Pre ECT Session | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| MMSE | 21 | 22 | 25 | 28 | 28 |

| DRS-2 | 120 (raw score) 4 (DRS-2 AMSS) 3 (DRS-2 AEMSS) | ||||

| Ham-D24 | 45 | 43 | 41 | 34 | 18 |

Open in a separate window

ECT = electroconvulsive therapy, MMSE = Mini Mental State Examination, DRS-2 = Dementia Rating Scale, Second Edition, HRSD24 = 24-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression; AMSS = Age-Corrected Mayo Clinic’s Older Americans Normative Studies (MOANS) scaled score, AEMSS = Age- and Education-Corrected MOANS scaled score

Discussion

The MMSE and DRS-2 are routinely used by clinicians and researchers to determine global cognitive function and establish operational criteria for excluding or including patients with dementia in controlled clinical trials. 20 Previous studies have found that global cognition and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) can both be impaired in severely depressed patients.25 In contrast to younger patients with severe depression, older adults with severe depression are more likely to display significant cognitive impairments associated with depressive symptomatology.2 These cognitive changes can contribute to the severity of psychiatric symptoms and disability that older depressed patients face and likely reflect compromise of certain neural circuits, directly linking cognitive impairments to late-life depression.26

20 Previous studies have found that global cognition and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) can both be impaired in severely depressed patients.25 In contrast to younger patients with severe depression, older adults with severe depression are more likely to display significant cognitive impairments associated with depressive symptomatology.2 These cognitive changes can contribute to the severity of psychiatric symptoms and disability that older depressed patients face and likely reflect compromise of certain neural circuits, directly linking cognitive impairments to late-life depression.26

Based on the case report described here, we propose that performance on the MMSE and DRS-2 should not be the only measures used to determine if a patient with MDD with psychotic features also has possible dementia, which will result in exclusion from a clinical trial. We have described the therapeutic value of ECT treatment in a patient with psychotic depression whose initial scores based on standardized cut-off values on both the MMSE and DRS-2 categorized her performance in the moderate to severe dementia range. The severe depression and psychotic state of the patient described in this case report would have incorrectly been attributed to cognitive deficits associated with dementia if the MMSE and DRS-2 instruments were interpreted solely based on accepted manualized cut-off scores specific for each instrument. Thus, further research is warranted regarding performance on the MMSE and DRS-2 measures in patient cohorts with MDD with psychotic features to determine their psychometric properties and appropriate scores to define normal and abnormal performance.

The severe depression and psychotic state of the patient described in this case report would have incorrectly been attributed to cognitive deficits associated with dementia if the MMSE and DRS-2 instruments were interpreted solely based on accepted manualized cut-off scores specific for each instrument. Thus, further research is warranted regarding performance on the MMSE and DRS-2 measures in patient cohorts with MDD with psychotic features to determine their psychometric properties and appropriate scores to define normal and abnormal performance.

David A, Kahn, MD

Wagner and colleagues describe an elderly patient with psychotic depression who met screening criteria for possible dementia based on low scores on the MMSE and DRS-2, but who improved after a course of ECT to the point where her MMSE was almost normal (28 out of a possible 30). The DRS-2 was not repeated, which would have been of interest. Their article makes the focused point that, if we use standard screens for dementia in patients who have psychotic depression, we should take the cutoff scores with a grain of salt. This is the case whether we are screening for suitability for inclusion in research or to make a clinical diagnosis of dementia. The authors discuss the phenomenon of state-specific, reversible cognitive impairment in severe depression, known as pseudodementia, a common finding in elderly patients with psychotic depression. While a possible harbinger of future real dementia, “pseudodementia” is not the same thing—a key point in our education of patients and families who fear worsened cognition from ECT.

This is the case whether we are screening for suitability for inclusion in research or to make a clinical diagnosis of dementia. The authors discuss the phenomenon of state-specific, reversible cognitive impairment in severe depression, known as pseudodementia, a common finding in elderly patients with psychotic depression. While a possible harbinger of future real dementia, “pseudodementia” is not the same thing—a key point in our education of patients and families who fear worsened cognition from ECT.

Cognitive effects of ECT on retrograde, autobiographical memory are widely known, so it may come as a surprise to patients, and even to ourselves, that certain aspects of cognitive functioning may improve with ECT treatment. Perhaps the best known public examplar of this phenomenon was the great pianist Vladimir Horowitz, who suffered from crippling depressions that left him unable to perform: “My octaves are no good now; they used to be, but not now.”27 (p. 387). As described in numerous biographies, he returned to the stage triumphantly following courses of ECT in the 1960s and 1970s. 27 His mind recovered a repertoire of over 400 pieces; a testament to the net benefit of ECT to restore, not destroy, brain function while alleviating depression. It was amazing to see Horowitz internationally televised from Moscow a decade later, twirling through Mozart and Rachmaninoff.

27 His mind recovered a repertoire of over 400 pieces; a testament to the net benefit of ECT to restore, not destroy, brain function while alleviating depression. It was amazing to see Horowitz internationally televised from Moscow a decade later, twirling through Mozart and Rachmaninoff.

A number of studies have evaluated cognitive effects of ECT in detail. At least two meta-analyses have aggregated these results, useful summations since the individual studies are small and vary widely in their testing approaches to fine-grained distinctions between different aspects of cognition such as encoding, learning, retention, and retrieval, as well as treatment variables such as modality, energy dose, and waveform.

First, in 2010, Semkovska and McLoughlin28 pooled data from 82 studies of patients 18 years of age and older. They included studies that provided at least one reported mean and standard deviation from standardized cognitive testing or a test of significance of difference within subjects, as well as measurements both pre- and post-treatment. They grouped data into relatively homogeneous pools, and created definitions for time course of post-ECT recovery, dividing it into subacute (0–3 days after complete of ECT course), short-term (4-15 days), and long-term (> 15 days).

They grouped data into relatively homogeneous pools, and created definitions for time course of post-ECT recovery, dividing it into subacute (0–3 days after complete of ECT course), short-term (4-15 days), and long-term (> 15 days).

The results of this study were as follows. Global cognitive status as measured by the MMSE was slightly impaired subacutely, but improved thereafter over baseline. Processing speed was mildly impaired subacutely, recovered to baseline short-term, and then improved over baseline long-term. Attention and working memory (digit span forward and backward, mental control, spatial span) were unchanged or slightly improved. Verbal memory (word lists, story memory, paired associates) showed subacute impairment but at long-term was showed slight improvement. Visual memory for figure reproduction recall showed small subacute impairment, but improvement over baseline at long-term follow-up. Executive functioning tests included the Trail Making Test Part B for set-shifting, the Stroop Color-Word condition for mental flexibility in speed and quality of performance, and the Semantic and Letter Fluency test for organizing thinking. These tests showed medium to large subacute impairment, recovery of baseline in the short-term and either maintenance of baseline performance or small to medium improvement in the long-term. Vocabulary and IQ, measured in a few studies as indicators of overall intellectual ability, were unchanged. The authors also analyzed variations in how ECT was administered. Not surprisingly, electrode placement was a factor, with bilateral (bitemporal placement) ECT producing greater subacute and short-term impairment compared with unilateral ECT in verbal and non-verbal recall. At the same time, bilateral ECT was associated with greater improvement over baseline than unilateral ECT in MMSE short-term and one test of verbal learning long-term. Differences in waveform and frequency of administration did not appear to influence cognition. The authors concluded that ECT caused significant impairment in the first few days after treatment, but that, compared with baseline, these deficits resolved during the next 2 weeks, and some functions actually improved over baseline after that.

These tests showed medium to large subacute impairment, recovery of baseline in the short-term and either maintenance of baseline performance or small to medium improvement in the long-term. Vocabulary and IQ, measured in a few studies as indicators of overall intellectual ability, were unchanged. The authors also analyzed variations in how ECT was administered. Not surprisingly, electrode placement was a factor, with bilateral (bitemporal placement) ECT producing greater subacute and short-term impairment compared with unilateral ECT in verbal and non-verbal recall. At the same time, bilateral ECT was associated with greater improvement over baseline than unilateral ECT in MMSE short-term and one test of verbal learning long-term. Differences in waveform and frequency of administration did not appear to influence cognition. The authors concluded that ECT caused significant impairment in the first few days after treatment, but that, compared with baseline, these deficits resolved during the next 2 weeks, and some functions actually improved over baseline after that. There were no persistent cognitive deficits resulting from ECT beyond 15 days. The authors noted that it is well established that major depression itself is associated with cognitive deficits. After ECT, some baseline deficits persisted, while some improved; none worsened.

There were no persistent cognitive deficits resulting from ECT beyond 15 days. The authors noted that it is well established that major depression itself is associated with cognitive deficits. After ECT, some baseline deficits persisted, while some improved; none worsened.

Tielkes et at.29conducted a meta-analysis of ECT’s cognitive effects in the elderly, evaluating 15 studies performed between 1980 and 2006 in patients 55 years of age and older that included at least one instrument for cognitive measurement before and after treatment. A few of these studies were also included in the Semkovska and McLoughlin analysis, but many were not due to less rigorous data collection. Methods of measurement—timing and instruments—varied widely, as did exclusion criteria of patients with known cognitive disorders. Most of the studies sused only the MMSE. At baseline, most studies reported mild to moderate cognitive dysfunction due to depression; all showed improvement in mood after ECT.

Results within 2 weeks post-ECT showed that global cognitive functioning improved in patients who had demonstrated cognitive impairment or dementia pre-ECT, defined as MMSE under 24. However, in patients with a pre-ECT MMSE of 24 or higher, cognitive function was stable pre- and post-treatment. The memory subscale of MMSE declined but other subscales improved or stayed the same. Older patients who had had more previous ECT treatments were more vulnerable, and bilateral treatment was more likely to impair memory than unilateral treatment. At longer term follow-up of up to 1 month, the unilateral group showed a trend toward global improvement. One study showed significant improvement in naming, learning, and delayed recall.30 Another showed that ECT improved speed of processing, memory, and perception; improvement in depression was associated with improvement in verbal learning memory, processing speed, and executive functioning.31 The meta-analysis showed that global cognitive functioning was largely stable during maintenance ECT, but that there were some focal decreases, particularly in verbal fluency, during the week after each treatment. 29

29

An interesting study by Bayless and colleagues in 200932 evaluated cognitive function before ECT compared with 2 to 3 weeks post-ECT in 20 patients with psychotic depression. Mean ratings of depression, positive symptoms, and negative symptoms all improved markedly. Average ratings of cognitive function also improved. While 30% of the sample qualified as impaired on the testing battery used in this study pre-ECT, only 10% were impaired afterwards. Cognitive function improved significantly on many subscales, most notably those related to attention and language. Interestingly however, linear regression analysis showed that cognitive improvement correlated most with improvement in negative symptoms and not with change in depression or psychosis, suggesting that ECT’s effects on cognition may involve areas of the brain apart from those directly related to the symptoms we think of as core features of psychotic depression.

Discussions by some authors mentioned uncertainty as to whether ECT leads to cognitive improvement by inducing remission from depression, or by specific cognitive-enhancing effects on brain function apart from antidepressant activity. As far as I am aware, there is no meta-analysis comparing cognitive function during and after depressive episodes that remit with medication, ECT, and placebo, which would be a good test of modality-specific effects on cognition, compared with disease-state effects.

As far as I am aware, there is no meta-analysis comparing cognitive function during and after depressive episodes that remit with medication, ECT, and placebo, which would be a good test of modality-specific effects on cognition, compared with disease-state effects.

Both of the meta-analyses as well as the individual studies cited above did not address the most persistent complaint about ECT, long-term retrograde amnesia for personal memories prior to the course of treatment. Research in this area has been flawed by lack of controls for autobiographical memory—what is the “normal” rate of forgetting personal information? Recent studies have used tests of impersonal verbal and visuo-spatial information taught shortly before ECT and retested later, and have compared results with those of matched controls without depression. Using this technique, O’Connor et al. were able to show that retrograde memory, but not anterograde memory, was somewhat impaired.33 The study was not designed to evaluate long-term personal memory or unilateral/bilateral differences. It would have been interesting if the researchers had included a second control sample of depressed patients who were receiving medication instead of ECT.

It would have been interesting if the researchers had included a second control sample of depressed patients who were receiving medication instead of ECT.

In a large study comparing waveforms and modalities, Sackeim and colleagues evaluated both recently taught information and longer term personal memory for public events.34 They showed that an ultra-brief pulse stimulus (0.3 millisecond), given unilaterally, resulted in far less retrograde memory loss and subjective distress than bilateral standard brief pulse (0.15 millisecond) or bilateral ultra-brief pulse ECT—not a surprising result. However, the unilateral ultra-brief pulse stimulus was also markedly less injurious to long-term and recent retrograde memory than unilateral ECT given with standard brief pulse stimulus, an important new finding about minimizing side effects within the unilateral modality. Differences persisted for the 6 months of follow-up. Older patients, and those receiving more treatments, consistently performed more poorly in all conditions.

The bottom line is that global and granular measures of present-state cognitive functions, including the ability to learn and utilize new material, improve in patients who receive ECT, including the elderly and those with psychosis. Retrograde memory, less often assessed in formal studies, has been shown to be impaired to varying degrees depending on the laterality and waveform as well as the age of patients and extent of treatment. In counseling patients and families about what to expect from ECT, and in obtaining their informed consent, we can convey not only optimism about the effects of ECT on depression, but also on many aspects of day-to-day cognitive functioning that have been weakened by depression. This optimism is tempered by the possibility of some loss of prior memory, which can be reduced by using the most modern technique of ultra-brief pulse, unilateral stimulus. The case report by Wagner and colleagues illustrates an outcome in which the patient passed from “pseudodementia” to normal anterograde global cognitive functioning over the course of ECT. A review of available evidence happily suggests that this outcome is the rule, not the exception.

A review of available evidence happily suggests that this outcome is the rule, not the exception.

1. Ohayon MM, Schatzberg AF. Prevalence of depressive episodes with psychotic features in the general population. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;11:1855–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Kessing LV. Differences in diagnostic subtypes among patients with late and early onset of a single depressive episode. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2006;21:1127–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Kupfer DJ, Spiker DG. Refractory depression: Prediction of non-response by clinical indicators. J Clin Psychiatry. 1981;42:307–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Serretti A, Lattuada E, Cusin C, et al. Clinical and demographic features of psychotic and nonpsychotic depression. Compr Psychiatry. 1999;40:358–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Thakur M, Hays J, Kishnan KRR. Clinical, demographic and social characteristics of psychotic depression. Psychiatry Res. 1999;86:99–106. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Baldwin R. Delusional (psychotic) depression in the elderly. In: Marneros A, editor. Late-onset mental disorders. London: Gaskel; 1999. pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

Baldwin R. Delusional (psychotic) depression in the elderly. In: Marneros A, editor. Late-onset mental disorders. London: Gaskel; 1999. pp. 59–82. [Google Scholar]

7. Nelson EB, Sax KW, Strakowski SM. Attentional performance in patients with psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression and schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155:137–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Bulbena A, Berrios GE. Pseudodementia: Facts and figures. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;148:87–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC. The course of geriatric depression with reversible dementia: A controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1693–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Reynolds CF, III, Kupfer DJ, Hoch CC, et al. Two-year follow-up of elderly patients with mixed depression and dementia. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1986;34:793–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Saez-Fonseca JA, Lee L, Walker Z. Long-term outcome of depressive pseudodementia in the elderly. J Affect Disord. 2007;101:123–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Schatzberg AF. New approaches to managing psychotic depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl.1):19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Tyrka AR, Price LH, Mello MF, et al. Psychotic major depression: A benefit-risk assessment of treatment options. Drug Saf. 2006;29:491–508. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Vega JAW, Mortimer AM, Tyson PJ. Somatic treatment of psychotic depression: Review and recommendations for practice. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2000;20:504–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

15. Parker G, Roy K, Hadzi-Pavlovic D, et al. Psychotic (delusional) depression: A meta-analysis of physical treatments. J Affect Disord. 1992;24:17–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Petrides G, Fink M, Husain M, et al. ECT remission rates in psychotic versus nonpsychotic depressed patients: A report from CORE. J ECT. 2001;17:244–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Kellner CH, Knapp R, Husain MM, et al. Bifrontal, bitemporal and right unilateral electrode placement in ECT: Randomized trial. Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:226–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Br J Psychiatry. 2010;196:226–34. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Hiremani RM, Thirthalli J, Tharayil BS, et al. Double-blind randomized controlled study comparing short-term efficacy of bifrontal and bitemporal electroconvulsive therapy. Bipolar Disord. 2008;10:701–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Husain MM, McClintock SM, Rush AJ, et al. The efficacy of acute electroconvulsive therapy in atypical depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:406–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-mental state: Practical method for grading cognitive state of patients for clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:189–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Jurica PJ, Leitten CL, Mattis S. DRS-2: Dementia Rating Scale-2 Professional Manual. Lutz, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 2001. [Google Scholar]

22. Hedlung JL, Vieweg BL. The Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression. J Oper Psychiatry. 1979;10:149–65. [Google Scholar]

23. Vitaliano PP, Breen AR, Russo J, et al. The clinical utility of the Dementia Rating Scale for assessing Alzheimer patients. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37:743–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Vitaliano PP, Breen AR, Russo J, et al. The clinical utility of the Dementia Rating Scale for assessing Alzheimer patients. J Chronic Dis. 1984;37:743–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Steinberg BA, Bieliauskas LA, Smith GE, et al. Mayo’s Older Americans Normative Studies: Age- and IQ-Adjusted Norms for the Wechsler Memory Scale–Revised. Clin Neuropsychol. 2005;19:378–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. McCall WV, Dunn AG. Cognitive deficits are associated with functional impairment in severely depressed patients. Psychiatry Res. 2003;121:179–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Crocco EA, Castro K, Loewenstein DA. How late-life depression affects cognition: Neural mechanisms. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2010;12:34–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Plaskin G. Horowitz: A biography of Vladimir Horowitz. New York: William Morrow; 1983. [Google Scholar]

28. Semkovska M, McLoughlin DM. Objective cognitive performance associated with electroconvulsive therapy for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:568–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biol Psychiatry. 2010;68:568–77. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Tielkes CE, Comijs HC, Verwijk E, et al. The effects of ECT on cognitive functioning in the elderly: A review. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2008;23:789–95. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Stoppe A, Louza M, Rosa M, et al. Fixed high-dose electroconvulsive therapy in the elderly with depression: A double-blind, randomized comparison of efficacy and tolerability between unilateral and bilateral electrode placement. J ECT. 2006;22:92–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Bosboom PR, Deijen JB. Age-related cognitive effects of ECT and ECT-induced mood improvement in depressive patients. Depress Anxiety. 2006;23:93–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Bayless JD, McCormick LM, Brumm MC, et al. Pre- and post-electroconvulsive therapy multidomain cognitive assessment in psychotic depression: Relationship to premorbid abilities and symptom improvement. J ECT. 2010;26:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. O’Connor M, Lebowitz BK, Ly J, et al. A dissociation between anterograde and retrograde amnesia after treatment with electroconvulsive therapy: A naturalistic investigation. J ECT. 2008;24:146–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

A dissociation between anterograde and retrograde amnesia after treatment with electroconvulsive therapy: A naturalistic investigation. J ECT. 2008;24:146–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Sackeim HA, Prudic J, Nobler MS, et al. Effects of pulse width and electrode placement on the efficacy and cognitive effects of electroconvulsive therapy. Brain Stimul. 2008;1:71–83. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

What Is It, Symptoms, Causes, and More

Psychotic depression refers to major depressive disorder (MDD) with features of psychosis, a specific presentation of depression. It involves symptoms of psychosis during an episode of depression.

Psychosis can include:

- hallucinations

- delusions

- psychomotor impairment

- a state of stupor

Estimates based on community samples suggest MDD with psychosis affects anywhere from 10 to 19 percent of people having an episode of major depression. Among people receiving inpatient care for depression, this rate increases to:

- between 25 and 45 percent of adults

- up to 53 percent of older adults

Some experts believe MDD with psychosis may actually occur at higher rates, since clinicians don’t always recognize psychosis when diagnosing depression.

In fact, a 2008 study considering data from four different medical centers found that clinicians misdiagnosed this condition 27 percent of the time.

Psychotic depression vs. major depression

MDD, or clinical depression, can affect your mood, behavior, everyday life, and physical health.

An episode of major depression typically involves:

- a persistent low mood or a loss of interest in everyday life for at least 2 weeks

- four or more other symptoms of depression (more on these symptoms in the next section)

Psychosis isn’t included in the nine main symptoms of depression, and many people living with MDD never experience psychosis.

The most recent edition of the “Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5)” classifies the two separately, listing depression with features of psychosis as “Other Specified Depressive Disorder.”

Depression is always serious. Still, experts tend to consider MDD with psychosis more serious than depression without psychosis because it’s more likely to involve:

- melancholic features

- more severe symptoms

- a greater risk of self-harm or thoughts of suicide

Need help now?

Depression with delusions and hallucinations can feel very frightening, especially when these beliefs and perceptions suggest you should hurt yourself or someone else.

If you’re having thoughts of suicide, know that help is available.

You can reach a trained counselor at any time of day by:

- calling 800-273-8255 to reach the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline

- texting HOME to 741-741 to reach the Crisis Text Line

If you need help to stay safe, contact a trusted loved one or a local mental health clinic or psychiatric hospital.

Get more suicide prevention resources.

Looking for tips to help someone in a crisis?

- Here’s how to support someone having thoughts of suicide.

- Here’s how to offer support for severe symptoms of psychosis.

If you have MDD with psychosis, you’ll have symptoms of both major depression and psychosis.

The symptoms of major depression include:

- a persistent low, empty, sad, or hopeless mood (some people may believe life is no longer worth living, but others might feel more irritable than sad)

- loss of interest and pleasure in activities you used to enjoy

- sudden or unexplained changes in appetite and weight

- sleeping difficulties, including sleeping much more or much less than usual

- less energy than usual or lingering fatigue

- changes in movement, such as increased restlessness or a sense of being slowed down

- difficulty concentrating or making decisions

- frequent feelings of worthlessness, helplessness, self-hatred, or guilt

- frequent thoughts of death, dying, or suicide

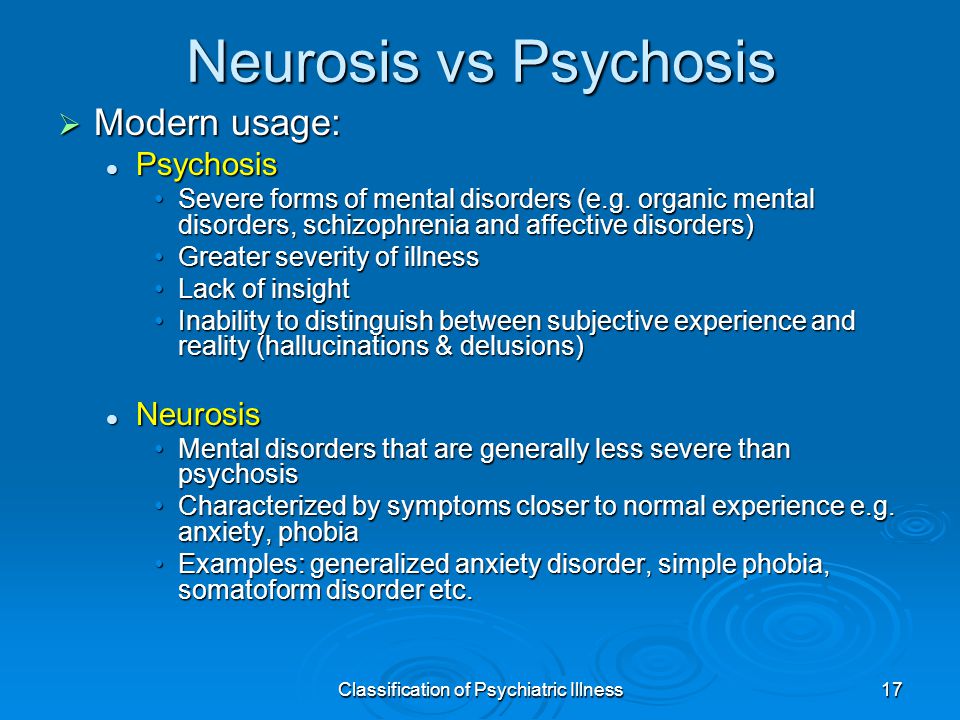

Psychosis involves a break or disconnect from reality, so people experiencing it aren’t necessarily aware of their symptoms, which can include:

- hallucinations, or seeing, hearing, and feeling things that aren’t real

- delusions, or believing things that aren’t true

- psychomotor impairment, or slowed thoughts, movements, and feelings

- a state of stupor, where you’re unable to move, speak, or respond to your environment

Psychotic hallucinations and delusions might involve:

- believing you have a serious health concern, despite multiple tests showing otherwise

- believing you have unique or special powers

- believing you’re a famous person or historical figure

- hearing voices criticizing or mocking you

- seeing a frightening or threatening animal following you

- paranoia, or an irrational or extreme suspicion of other people

Delusions, with or without hallucinations, happen more often than hallucinations alone in people experiencing psychotic depression.

Experts separate MDD with features of psychosis into two categories:

- MDD with mood-congruent psychotic features. Hallucinations and delusions reflect feelings and emotions that often show up with depression, including feelings of personal inadequacy, worthlessness, guilt, and fears about illness or death.

- MDD with mood-incongruent psychotic features. Hallucinations and delusions conflict with depression-related emotions. You might hallucinate a loved one, hear voices praising you, or smell something pleasant. You might also believe someone is trying to chase you, kidnap you, or control your thoughts.

You can have both mood-congruent and mood-incongruent symptoms. In the past, experts associated mood-incongruent features of psychosis with worse outcomes. Recent research suggests this isn’t necessarily the case.

Delusions and hallucinations often feel completely real. They can lead to terror, panic, and extreme distress.

Some people experiencing psychosis end up hurting themselves or others in an effort to make the symptoms stop. That’s what makes it so important to seek help for psychosis right away.

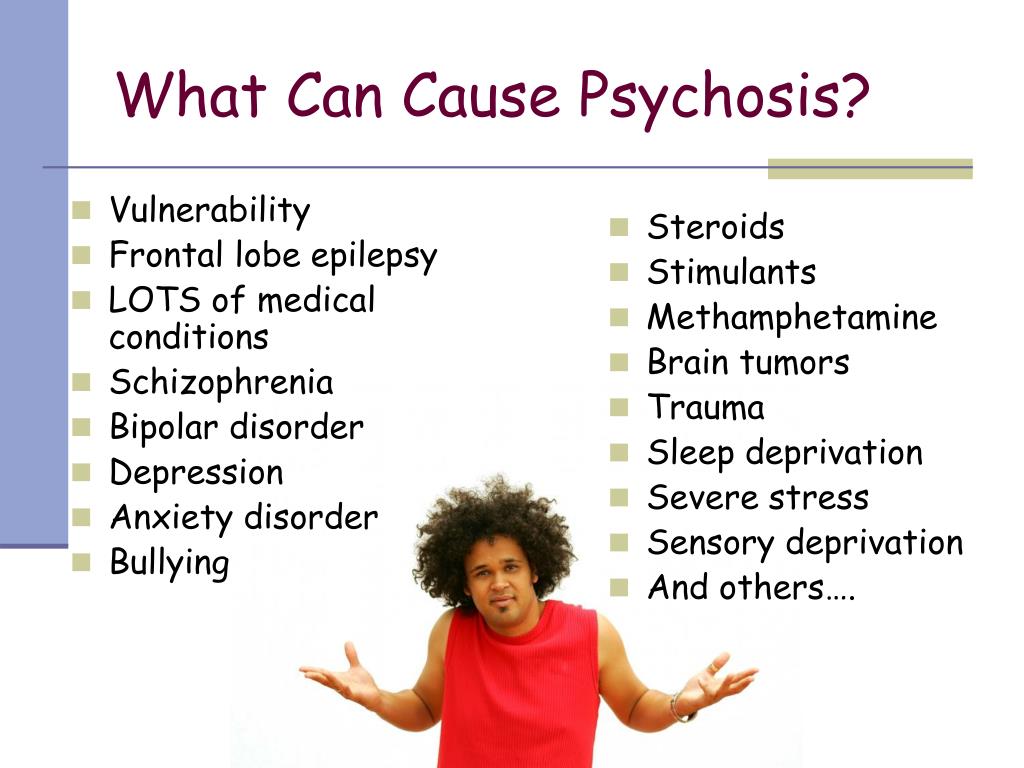

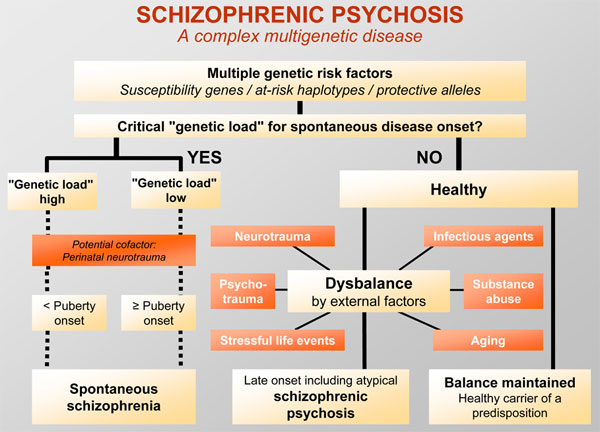

Researchers have yet to identify a single specific cause of MDD with psychosis, or any type of depression, for that matter.

Possible causes include:

- Genetics. You’re more likely to develop depression if a first-degree relative, like a parent or sibling, also has depression.

- Biology and brain chemistry. Imbalances in brain chemicals like dopamine and serotonin play a role in many mental health conditions, including depression and psychosis. Some evidence also suggests higher levels of the stress hormone, cortisol, may play a part.

- Environmental factors. Traumatic or stressful experiences, particularly in childhood, can also raise your chances of experiencing depression.

Risk factors

To date, not a lot of research has explored unique risk factors for MDD with psychosis.

According to a study published in 2016 comparing risk factors for schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and MDD with psychosis, factors that might increase the risk of MDD with psychosis include:

- not having close friends or loved ones to confide in

- infrequent contact with friends and family

- a family history of any mental health condition

- a major negative life event in the past year

Other factors that could raise your chances of developing the condition include:

- major hormonal changes, such as during the postpartum period or menopause

- surviving extreme stress or trauma

- living with chronic pain or other chronic health conditions

- ongoing financial difficulties

- gender (cisgender women and transgender people of any gender have a higher risk of depression)

- age (older adults have a higher risk of MDD with psychosis)

- a family history of bipolar disorder with psychosis, schizophrenia, or MDD with psychosis

People experiencing depression with psychosis don’t always seek help on their own. In some cases, it might be a family member or close friend who helps them find a medical or mental health professional who can make a diagnosis.

In some cases, it might be a family member or close friend who helps them find a medical or mental health professional who can make a diagnosis.

To make a diagnosis, they’ll generally start by asking questions about your mental health, mood, and emotional well-being. They might ask about:

- fixed beliefs or persistent worries that affect your daily life

- things you see, hear, or feel that no one else seems to notice

- problems with sleeping, eating, or going about your daily life

- your support network and social relationships

- health concerns

- other mental health symptoms, like anxiety or mania

- your personal and family health and mental health history

Psychosis isn’t always obvious, even to trained clinicians. Some mental health professionals may not immediately recognize the difference between fixed delusions and rumination, a pattern of looping sad, dark, or unwanted thoughts.

Both delusions and rumination, which is common with depression, can involve:

- fears of rejection

- concern for your health

- guilt over mistakes you believe you’ve made

- perceptions of yourself as a failed partner or parent

Describing all of your feelings, perceptions, and beliefs to your clinician can help them make the right diagnosis.

A diagnosis of major depression also requires that symptoms:

- last for 2 weeks or longer

- affect some areas of daily life

- aren’t related to substance use or another condition

A note on severity

MDD can be mild, moderate, or severe, based on the number of symptoms you have and how they affect daily life.

In the past, experts associated psychosis with severe major depression. Severe MDD involves most of the main symptoms of depression, which typically:

- have a major impact on daily life

- cause significant distress

- resist management and treatment

The DSM-5 considers severity and specifiers, like psychosis, separately.

In other words, you can have a “mild” episode of depression, with fewer symptoms that don’t majorly affect day-to-day life, and still experience psychosis. Dysthymia, or persistent depression, can also involve psychosis.

If you experience both depression and psychosis, you’ll want to get support from a mental health professional right away. This condition typically doesn’t improve without professional treatment.

This condition typically doesn’t improve without professional treatment.

Your care team may recommend a short stay in a psychiatric hospital to treat severe psychosis and persistent thoughts of self-harm or suicide.

Treatment for psychotic depression generally involves psychotropic medications, though you have other options, too.

Medication

Typically, medication treatment involves a combination of antidepressants and antipsychotics. These medications help balance neurotransmitters in the brain.

Your psychiatrist or doctor might, for example, prescribe a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) along with one of the following antipsychotics:

- olanzapine (Zyprexa)

- quetiapine (Seroquel)

- risperidone (Risperdal)

They can also provide more information about medication options, help you find the right medication and dose, and offer guidance on possible side effects.

These medications can begin working right away, but you might not notice their full effects for several weeks.

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Your care team may also recommend ECT for severe depression that doesn’t respond to medication or therapy.

You’ll typically receive ECT in a hospital while under anesthesia. This treatment involves a series of treatments that stimulate your brain with a controlled voltage of electrical current. The current creates a mild seizure, which affects the levels of neurotransmitters in your brain.

While it’s considered safe and generally effective for people experiencing thoughts of suicide, psychosis, and catatonia, ECT does involve a few possible risks, including:

- short-term memory loss

- nausea

- headache

- fatigue

Your care team will explain more about these risks before you begin treatment.

ECT may not keep your symptoms from coming back entirely, so your psychiatrist will likely recommend ongoing treatment in the form of therapy, medication, or both. They may also recommend future ECT treatments.

Therapy

While therapy alone may not do much to improve symptoms of psychosis on its own, it can still have benefit as a supportive approach.

Therapy offers a safe space to share distressing emotions and experiences, for one. A therapist can also teach strategies for coping with hallucinations and delusions.

Possible approaches include:

- cognitive behavioral therapy

- acceptance and commitment therapy

- behavioral activation

- acceptance-based depression and psychosis therapy

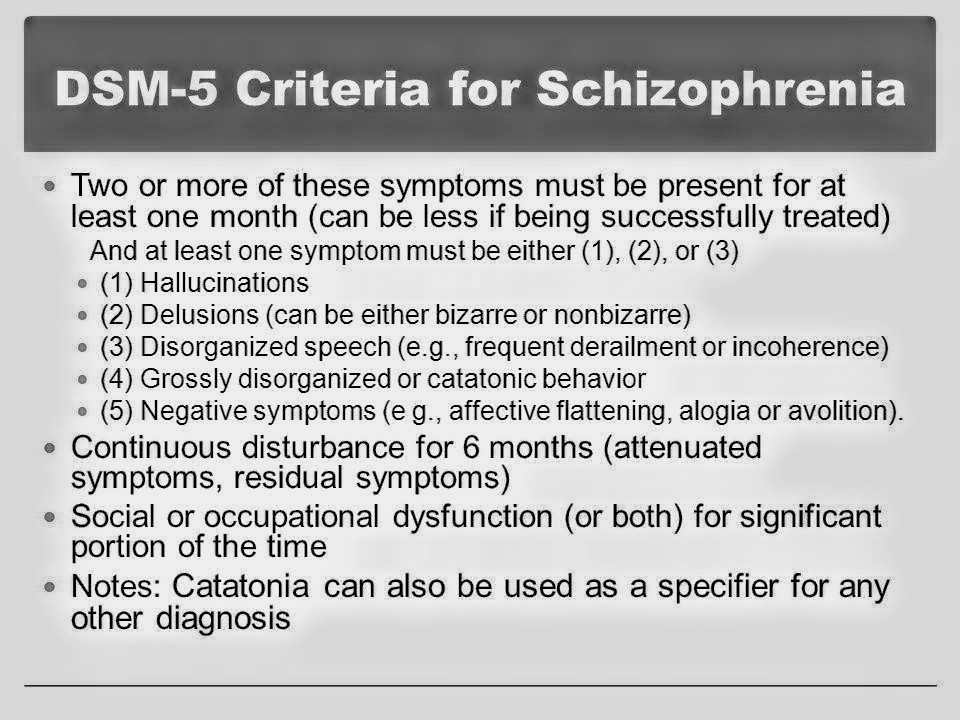

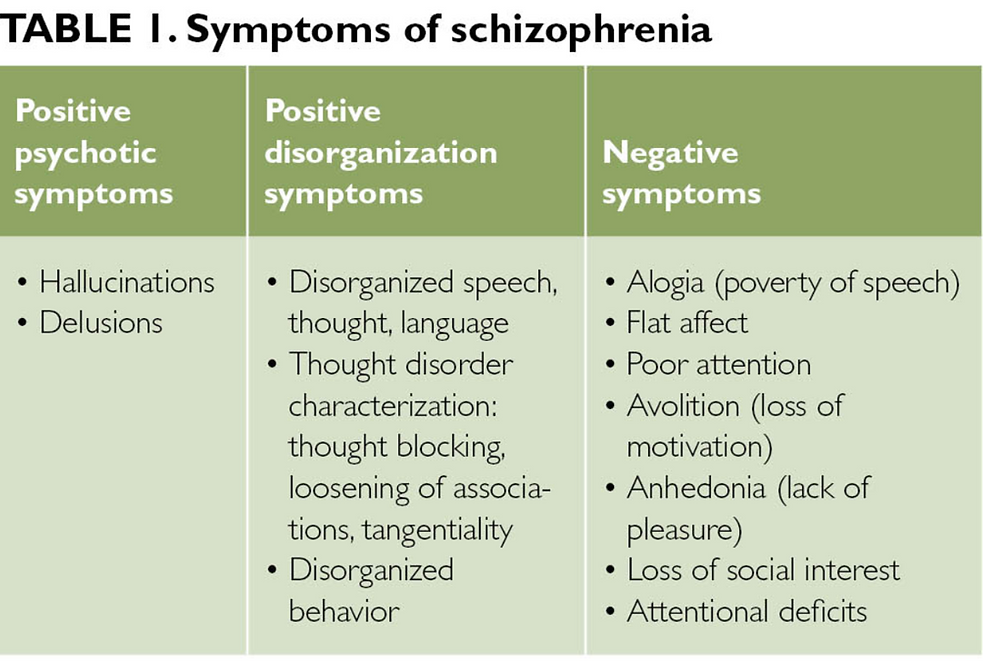

MDD with psychosis can sometimes resemble schizophrenia, another mental health condition that involves psychosis. The main difference lies in when psychosis shows up:

- If you have MDD with psychosis, you’ll only have symptoms of psychosis during an episode of depression.

- If you have schizophrenia, you’ll have symptoms of psychosis whether you have depression symptoms or not.

While schizophrenia doesn’t always involve depression, many people living with schizophrenia do have symptoms of depression, which can complicate diagnosis of either condition.

But schizophrenia involves other symptoms not necessarily associated with depression, including:

- disorganized or incoherent speech

- lack of emotional expression

- catatonia

Learn more about the symptoms of schizophrenia.

Some people diagnosed with MDD with psychosis later receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia or bipolar disorder with psychosis. This appears more likely for people:

- diagnosed with depression at a younger age

- who experience mood-incongruent symptoms

MDD with psychosis is a serious mental health condition that requires prompt treatment from a trained mental health professional. You do have options for treatment, and the right approach can improve symptoms of both depression and psychosis.

Finding the most effective treatment may take some time, and it’s important to share any persistent symptoms or side effects with your care team. They can help you manage side effects and explore alternate treatments, if needed.

Keep in mind, too, that friends and loved ones can also offer support.

News search - Prosecutor's Office of the Republic of Kalmykia

News

- November 15, 2010, 22:49

- Prosecutor's Office of the Republic of Kalmykia

Applications for termination of the right to drive vehicles were sent to the court.

Text

Share

Based on the results of the inspection of compliance with the law in the field of medical provision of road safety in terms of compliance with restrictions on driving, the prosecutor's office sent 62 applications to the court for the termination of the right to drive vehicles.

Such applications were filed by the prosecutors of the Tselinny district (50), Lagansky (4), Chernozemelsky (3), Yashalta (2), Iki-Burulsky, Gorodokovsky and Oktyabrsky districts (1 each).

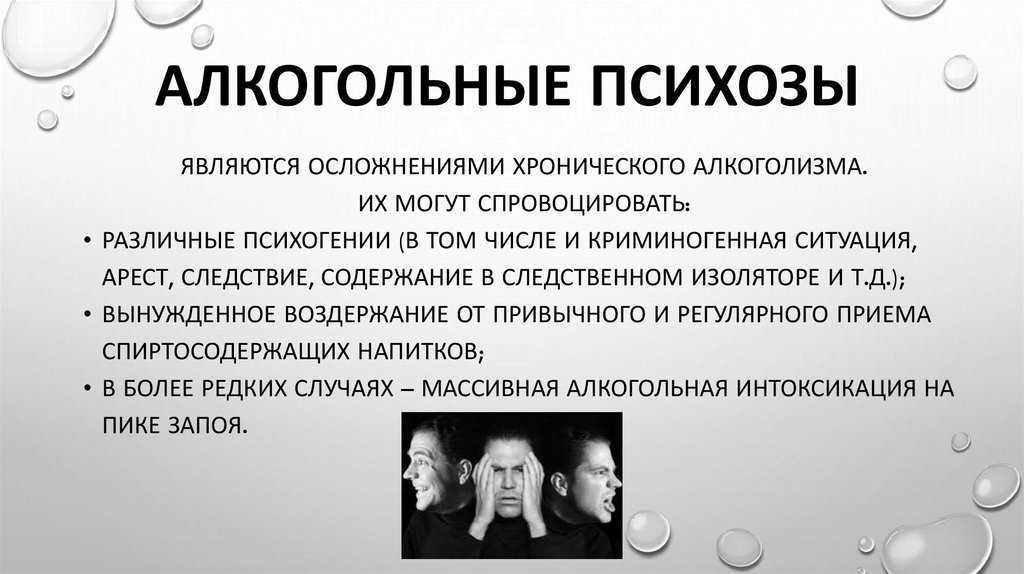

In these areas, the facts of issuing driver's licenses for the right to drive cars of various categories were revealed to citizens registered in dispensaries due to the presence of mental illness, drug addiction, and also registered in connection with alcoholism, including alcoholic psychosis. nine0021

In these areas, the facts of issuing driver's licenses for the right to drive cars of various categories were revealed to citizens registered in dispensaries due to the presence of mental illness, drug addiction, and also registered in connection with alcoholism, including alcoholic psychosis. nine0021 In accordance with the Federal Law "On Road Safety" the reason for the termination of the right to drive vehicles is the deterioration of health, confirmed by a medical report. Driving vehicles by persons suffering from drug addiction, substance abuse, alcoholism or mental disorders, in which driving is contraindicated, creates a real threat of accidents on the roads and can lead to harm to health and death of an indefinite number of people from among road users . nine0021

Currently, the courts of the republic have considered and satisfied 12 claims, 50 claims are being processed. At the same time, the consideration of civil cases of this category takes a long time, since the courts appoint forensic medical examinations in order to obtain an appropriate medical opinion on the presence or absence of obstacles to the exercise of the right to drive vehicles.

Print News archive nine0011

Applications for termination of the right to drive vehicles were sent to the court.

Based on the results of the inspection of compliance with the legislation in the field of medical provision of road safety in terms of compliance with restrictions on driving, the prosecutor's office sent 62 applications to the court for the termination of the right to drive vehicles.

Such applications were filed by the prosecutors of the Tselinny district (50), Lagansky (4), Chernozemelsky (3), Yashalta (2), Iki-Burulsky, Gorodokovsky and Oktyabrsky districts (1 each). In these areas, the facts of issuing driver's licenses for the right to drive cars of various categories were revealed to citizens registered in dispensaries due to the presence of mental illness, drug addiction, and also registered in connection with alcoholism, including alcoholic psychosis.

nine0021

nine0021 In accordance with the Federal Law "On Road Safety" the reason for the termination of the right to drive vehicles is the deterioration of health, confirmed by a medical report. Driving vehicles by persons suffering from drug addiction, substance abuse, alcoholism or mental disorders, in which driving is contraindicated, creates a real threat of accidents on the roads and can lead to harm to health and death of an indefinite number of people from among road users . nine0021

Currently, the courts of the republic have considered and satisfied 12 claims, 50 claims are being processed. At the same time, the consideration of civil cases of this category takes a long time, since the courts appoint forensic medical examinations in order to obtain an appropriate medical opinion on the presence or absence of obstacles to the exercise of the right to drive vehicles.

nine0010 Type of mailing

Daily weekly Instant

Specify one or more email addresses separated by ";"

nine0000 Facts of issuing driver's licenses to drug addicts and alcoholics revealed in Kalmykia - South and North Caucasus |

News August 19, 2010 6:41 pm

Elista. August 19. Interfax-South - In the Tselinny district of Kalmykia, 67 drivers registered in psycho-neurological and narcological dispensaries have been identified.

August 19. Interfax-South - In the Tselinny district of Kalmykia, 67 drivers registered in psycho-neurological and narcological dispensaries have been identified.

These facts were discovered during the inspection of compliance with the law in the field of medical provision of road safety, assistant district prosecutor Karmen Pavlova told Interfax-South on Thursday. nine0011

"The audit covered information about 396 accountable persons of the republican narcological and psycho-neurological dispensaries. A reconciliation of the data of medical institutions and the traffic police showed that today 67 residents of the Tselinny district who are registered with these dispensaries have driver's licenses," she said. .

It has been established that driving licenses were issued by the MREO OGIBDD of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Kalmykia on the basis of medical certificates to 15 citizens registered with mental illness, 10 drug addicts and 38 alcoholics, including those suffering from alcoholic psychosis. nine0011

nine0011

"Based on the results of an audit by the district prosecutor's office, 53 claims were filed with the district court for the termination of a driver's license. At the same time, submissions were made to eliminate violations of the law in the field of medical provision of road safety to the chief doctors of the district hospital, drug dispensary, psycho-neurological dispensary, the Minister of Health and Social development of the republic, to the traffic police of the Ministry of Internal Affairs of Kalmykia," K. Pavlova noted.

In addition, materials on all facts of illegal issuance of medical certificates were sent for procedural checks in accordance with Articles 144, 145 of the Code of Criminal Procedure of the Russian Federation. nine0011

-

Main events

More than 17 million tourists spent their holidays in the resorts of the Krasnodar Territory this year

More than 17 million tourists had a rest in the resorts of the Krasnodar Territory this year -

Viewpoint

bomber crash nine0011

Interfax-Russia.

bomber crash ru - A Su-34 bomber fell on a residential building in Yeysk. 15 people died, including three children.

ru - A Su-34 bomber fell on a residential building in Yeysk. 15 people died, including three children. -

Restoration work

Interfax-Russia.ru — Work on the restoration of the Crimean bridge after the explosion can take about a month and a half. Truck traffic could start by the end of the week.

-

Terrorist attack on the bridge

Interfax-Russia.ru — Undermining of the Crimean bridge is being investigated under the article "terrorism". Russian President Vladimir Putin blamed Ukraine's special services for the attack. nine0011

-

Emergency at warehouse

Interfax-Russia.ru — Detonation of ammunition occurred in a military unit in the Crimea, two people were injured. The military warehouse was damaged as a result of sabotage.

-

Dangerous maneuvers

Interfax-Russia.