Almost alcoholic pdf

Almost Alcoholic by Joseph Nowinski, Robert Doyle - Ebook

Ebook226 pages3 hours

Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars

3.5/5

()

About this ebook

Determine if your drinking is a problem, develop strategies for curbing your intake, and measure your progress with this practical, engaging guide to taking care of yourself.

Every day, millions of people drink a beer or two while watching a game, shake a cocktail at a party with friends, or enjoy a glass of wine with a good meal. For more than 30 percent of these drinkers, alcohol has begun to have a negative impact on their everyday lives. Yet, only a small number are true alcoholics--people who have completely lost control over their drinking and who need alcohol to function. The great majority are what Dr. Doyle and Dr. Nowinski call "Almost Alcoholics," a growing number of people whose excessive drinking contributes to a variety of problems in their lives.

In Almost Alcoholic, Dr. Doyle and Dr. Nowinski give the facts and guidance needed to address this often unrecognized and devastating condition. They provide the tools to: identify and assess your patterns of alcohol use; evaluate its impact on your relationships, work, and personal well-being; develop strategies and goals for changing the amount and frequency of alcohol use; measure the results of applying these strategies; and make informed decisions about your next steps.

Skip carousel

LanguageEnglish

PublisherHazelden Publishing

Release dateMar 13, 2012

ISBN9781616494254

Author

Joseph Nowinski

Joseph Nowinski, Ph.D., is a psychologist and family therapist. Currently the Supervising Psychologist at the University of Connecticut Health Center, he lectures frequently at the Hazeldon Foundation, and the University of Mexico Medical School. He is the author of The Identity Trap: Saving Our Teens from Themselves and 6 Questions That Can Change Your Life. Winner of the Nautilus award. He lives in Connecticut.

Winner of the Nautilus award. He lives in Connecticut.

Related categories

Skip carousel

Reviews for Almost Alcoholic

Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars

3.5/5

2 ratings2 reviews

Book preview

Almost Alcoholic - Joseph Nowinski

introduction Normal and Abnormal DrinkingWe are two doctors—a psychiatrist and a psychologist—who have worked as mental health professionals for many years. In addition, each of us has pursued further training in the area of substance abuse. We were privileged to have learned from experts in some of the best treatment centers in the world, including the Betty Ford Center and the Hazelden Foundation.

By way of introduction, Dr. Rob Doyle is a psychiatrist who works for Harvard University Health Services. Besides providing mental health medical care to Harvard students, he is involved in research and is a frequent speaker at workshops and conferences. Dr. Joe Nowinski, a clinical psychologist, works for the University of Connecticut Health Center. He also is involved in research in substance abuse treatment and has trained many clinicians in the interventions he has developed.

Dr. Joe Nowinski, a clinical psychologist, works for the University of Connecticut Health Center. He also is involved in research in substance abuse treatment and has trained many clinicians in the interventions he has developed.

In this book, we will share an important revelation that we have learned from our collective experience. This revelation has not been described in other books or even in the medical literature. Nevertheless, it has enormous impact on the lives of millions of people. Here’s what we’ve discovered: the men and women who have been diagnosed as alcohol dependent—or, more simply, alcoholic—represent but the tip of the iceberg of a much larger segment of the population whose lives are negatively impacted by alcohol use. One way to think of those who carry an official alcohol-related diagnosis is that they fit fairly neatly into a diagnostic box

defined by various objective symptoms. But what about this other group—the much larger part of the iceberg that lies below the waterline? Though not technically alcoholics, these men and women—young, middle-aged, and older adults—nevertheless are experiencing problems related to their drinking. There is pain and suffering going on that is undiagnosed—and untreated—simply because, until now, it hasn’t really been described or defined.

There is pain and suffering going on that is undiagnosed—and untreated—simply because, until now, it hasn’t really been described or defined.

We call these people almost alcoholics

and this is the first book that identifies and explains this condition. The almost

concept is a paradigm shift in the way we look at alcohol use. Put simply, the almost alcoholic

does not drink normally but also wouldn’t be labeled an alcoholic.

Because this is a new concept to many people, they often don’t see the connection between their drinking and the various problems it is causing. Similarly, the doctors or other professionals they consult with may not connect the dots either. The result is that quite a few of these men and women will continue to suffer the consequences of their drinking—consequences that not only affect them directly, but have a powerful ripple effect and cause considerable suffering to those around them as well. Such consequences may include failed romantic relationships, alienation of children and parents, careers marked by underachievement, declining health, and emotional problems. Eventually, for some of these people, their drinking will progress to the point where they will be diagnosed as alcoholics and will hopefully get help. But even if they don’t reach this point, the significant, unaddressed suffering of the person who is almost alcoholic can be relieved by recognizing the problem and then addressing it.

Eventually, for some of these people, their drinking will progress to the point where they will be diagnosed as alcoholics and will hopefully get help. But even if they don’t reach this point, the significant, unaddressed suffering of the person who is almost alcoholic can be relieved by recognizing the problem and then addressing it.

In this book, we help you understand what it means to be an almost alcoholic—whether that term applies to you or to someone you care about—and we give you some practical, proven suggestions on what you (or your loved one) can do about it. If you are concerned about another person, we encourage you to share this book with him or her. You might suggest keeping a journal to answer the questions that appear in the book; they are designed to help people assess and make good decisions about their drinking.

Either way, let’s start by taking a look at cultural values around alcohol use, and with that as background, we can begin to explore the difference between almost alcoholics and true alcoholics.

Social Drinking, Almost Alcoholics, and Alcoholics

Drinking alcoholic beverages—at least in a social context—has been part of many cultures for centuries. The United States is no exception. You need only turn on a Sunday afternoon football or baseball game on television to witness a seemingly endless array of commercials showing men and women having a great time together, snacking and downing cold beers. Those images convey that drinking is a normal, fun social activity. Indeed, for many people pizza and beer, cocktails, or wine and cheese—enjoyed in the company of friends, at the ballpark, at a happy hour, or in a sports bar—are a routine part of a normal social life.

Okay, if you’re not an alcoholic and social drinking is a normal part of life—what’s the problem? Why write this book? Very simply, because we’ve learned that a certain percentage of those men and women who are enjoying themselves watching games and drinking cold beers (or enjoying wine and cheese with friends) will at some point cross a line—a line they will most likely not recognize—and become what we’re calling almost alcoholics. The reason they will not realize what they have done is that the line separating normal social drinking from being almost alcoholic is not bright and sharp, but is more of a gray area that people can venture into before they know what’s happened.

The reason they will not realize what they have done is that the line separating normal social drinking from being almost alcoholic is not bright and sharp, but is more of a gray area that people can venture into before they know what’s happened.

We know that some people who start drinking will never be normal

or social drinkers and will go on to become true alcoholics. What does that mean? Essentially, it means two things. First, the true alcoholic will inevitably reach a point where one drink is never enough. Once true alcoholics reach this stage, when they start drinking, they rarely stop until they’re drunk. Second, alcoholics do not feel normal without some amount of alcohol circulating in their bloodstream. As soon as their blood alcohol level gets low, they start craving a drink. And since one drink is never enough, stopping once they’ve started drinking is not an option. These constitute two of the core symptoms

that have classically defined alcoholism. They are key elements in the diagnostic box

that most professionals (and insurance companies) use to decide who needs treatment for a drinking problem.

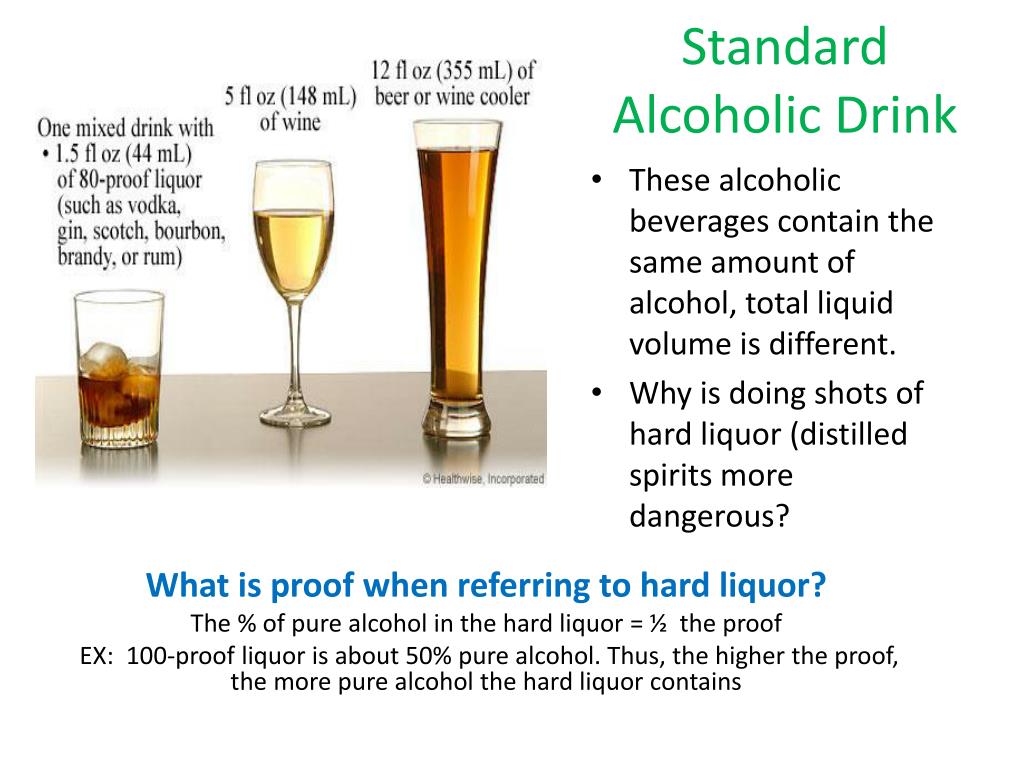

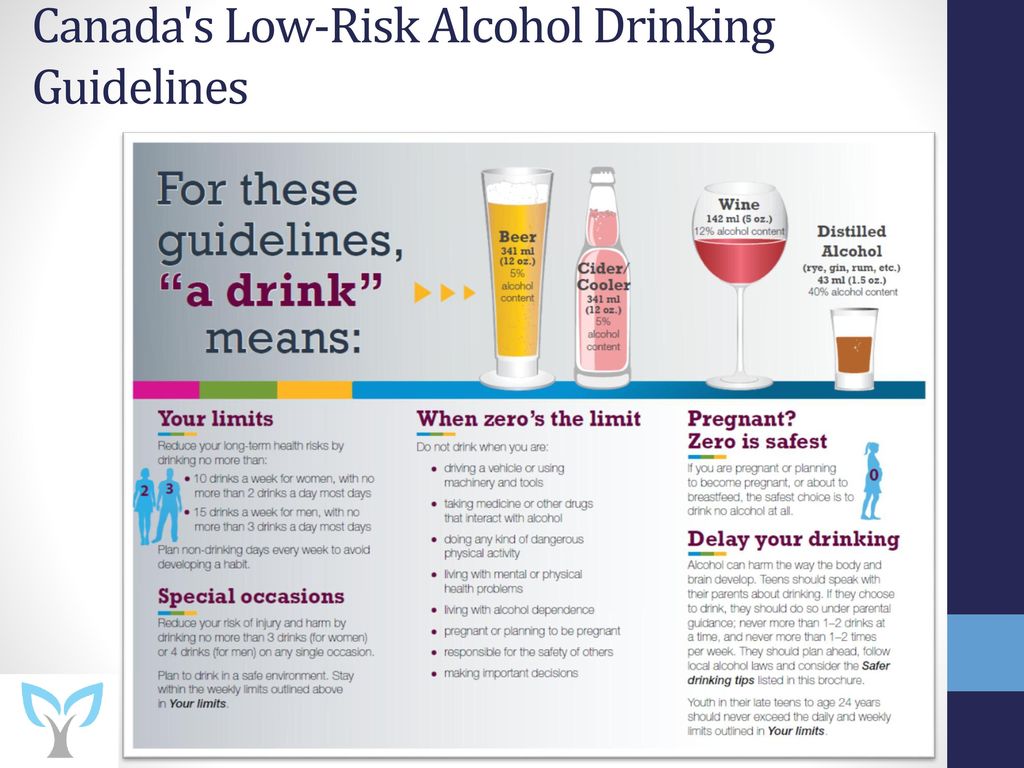

Of course, alcoholism is not diagnosed simply by these two concepts. There is a longer list of criteria, put forth by the American Psychiatric Association and the American Medical Association. In the next chapter, we list these criteria and compare them to our criteria for almost alcoholism. Alcohol dependence represents one extreme on a spectrum that ranges from low-risk or social

drinking to true alcoholism. Alcoholism is a much more severe problem and is associated with much more severe consequences than almost alcoholism, which occupies a large zone

that lies between normal low-risk drinking and alcoholism.

As two mental health professionals specializing in treating people with alcohol and drug problems, we have diagnosed and worked with many true alcoholics. We know they have a disease and need help. Many of them recover and go on to lead very productive lives. But this book is about almost alcoholics and, although this condition has not been well studied, we estimate that for every alcoholic who fits the official diagnostic criteria for alcoholism, there are many others who almost

fit the criteria and are, therefore, almost alcoholics. Their problems are usually not as severe as the problems faced by alcoholics, but they are nonetheless real and can have devastating effects on the lives of almost alcoholics and the people around them.

Their problems are usually not as severe as the problems faced by alcoholics, but they are nonetheless real and can have devastating effects on the lives of almost alcoholics and the people around them.

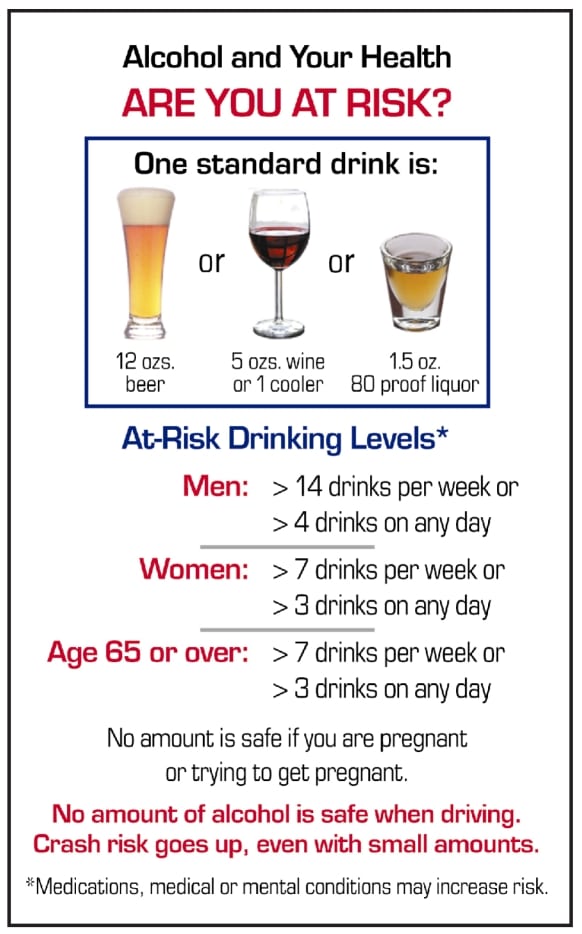

Our clinical experience is supported by research conducted by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. According to the NIAAA, the percentage of Americans who may not be alcoholics but whose self-reported drinking is enough to qualify them as having problems that can be linked to drinking has been on the increase for at least a decade.¹ It is among this group of people that we find the almost alcoholics.

Drinking Is Seldom the Reason People Seek Help

When almost alcoholics come to one of our offices, it is usually not for help with what they see as a drinking problem. Rather, they may be having trouble managing a teenage child. Or they may complain that their marriage seems in danger from too much fighting and too little sex. Sometimes they come to us because they’ve been feeling depressed or anxious for a long time or have been suffering from chronic insomnia. Many of them have said that a few drinks at the end of the day helped them to relax or fall asleep, only to find in time that the drinks no longer produced this effect.

Sometimes they come to us because they’ve been feeling depressed or anxious for a long time or have been suffering from chronic insomnia. Many of them have said that a few drinks at the end of the day helped them to relax or fall asleep, only to find in time that the drinks no longer produced this effect.

You will meet some of these people in this book. The case examples are drawn from our own professional experience, but we have changed names and other identifying features to protect the privacy of those involved. Some characters are composites.

Some almost alcoholics seek help for a medical issue, again without seeing the connection between drinking and their symptoms. Matt was one of these people. A forty-five-year-old sales executive, Matt considered himself successful—at least in his work. Divorced and with an eight-year-old daughter, Matt spent a lot of time on the road, so much so that he said, I think of airports as my office.

He was as connected as anyone we’d heard of and was capable of hosting online meetings while waiting for his flight to board.

Matt made an appointment with his doctor when he noticed, to his considerable distress, that his hands and feet tingled

and sometimes became numb. His doctor sent him to see several specialists, including a hematologist, a rheumatologist, and a neurologist. Initially, the tests all came out clear, but then he had nerve and muscle studies (sometimes referred to as EMGs or electromyograms) to test for nerve damage. These tests revealed injury to the nerves in his hands and feet, called a peripheral neuropathy. There are many things that can cause a peripheral neuropathy, including alcohol. In most cases, so-called alcoholic neuropathy takes a long time to become evident, which is why a doctor might not suspect it in a man of forty-five. However, some cases of alcohol-related neuropathy have been associated with acute and rapidly progressive onset.

After getting these test results, Matt’s doctor met with him for nearly an hour and did an in-depth assessment. It was during that assessment that Matt disclosed that he’d been in the habit of drinking three or four beers a day—plus an occasional cocktail or two—every day except those days when his daughter visited with him, which given his extensive business travels amounted to no more than five or six days a month. Moreover, he’d been drinking that much for many years. But he never missed a day of work, never had a blackout, and was able to

Moreover, he’d been drinking that much for many years. But he never missed a day of work, never had a blackout, and was able to hold his liquor

well so that people around him never realized he was in fact intoxicated.

Being just forty-five, it had never occurred to Matt that he could be suffering from serious medical problems due to his drinking, and the possibility only emerged when his doctor conducted a thorough inquiry. When his doctor referred Matt back to the neurologist with this added information, further tests revealed that Matt was indeed suffering from a peripheral neuropathy that was most likely caused by his drinking. Matt’s doctor also told him there was a chance that his neuropathy could be arrested, and perhaps even reversed, but only if Matt abstained from drinking. Given the dire situation he found himself in, Matt decided to do just that. A year later, he was able to report to his doctor that, while he still had occasional bouts of numbness or tingling in his hands and feet, they had indeed become less frequent and severe since he’d stopped drinking.

Social Drinking and Almost Alcoholic Drinking

Matt’s story and many others like his have brought this large group of previously undiagnosed individuals to our attention. As diverse as their stated reasons for seeking help may be, the common denominator for many of these people could be described as social drinking gone over the line.

In other words, they’ve crossed over into that gray area we are calling the almost alcoholic zone.

Although there’s a strong correlation between their alcohol use and the problems we have described, our experience is that most almost alcoholics see no connection between the problems and their drinking. They are unable to connect the dots.

We’re not really surprised, for two reasons. First, because little has been written about crossing the line separating low-risk drinking from almost alcoholic drinking, it represents a new and novel concept to most people.

The second reason is that this change—moving from normal drinking to almost alcoholism—doesn’t happen suddenly. Rather, it typically is a slow and insidious process, one that is so subtle and gradual as to be virtually undetectable to those who are experiencing it (as well as to those who are close to them). From what we have seen, this process can take years and can be so gradual that those affected never see a reason to consult with a doctor or counselor, much less change their drinking behavior. Yet others around them—spouses, other family members, friends, colleagues, employers—often do see the problems caused by the drinking, even if they don’t recognize the drinking as a contributing factor. Sometimes it is pressure from these people that drives the almost alcoholic (reluctantly) to give us a call.

Rather, it typically is a slow and insidious process, one that is so subtle and gradual as to be virtually undetectable to those who are experiencing it (as well as to those who are close to them). From what we have seen, this process can take years and can be so gradual that those affected never see a reason to consult with a doctor or counselor, much less change their drinking behavior. Yet others around them—spouses, other family members, friends, colleagues, employers—often do see the problems caused by the drinking, even if they don’t recognize the drinking as a contributing factor. Sometimes it is pressure from these people that drives the almost alcoholic (reluctantly) to give us a call.

What are we asking of you, the reader? Basically, we are asking you to keep an open mind as you read this book. We are not saying that social drinking will always lead to problem drinking, and we are not trying to put labels on people where there isn’t a problem. Instead, our goal is to recognize, acknowledge, and support people who are experiencing—and causing—real suffering with their almost alcoholic drinking. What we are saying is that we know there is a gray zone beyond social drinking, and this gray zone is the place where some social drinkers become almost alcoholics. We want to help you decide whether that has happened to you or to someone you love. If it has, we have some strategies that may help.

What we are saying is that we know there is a gray zone beyond social drinking, and this gray zone is the place where some social drinkers become almost alcoholics. We want to help you decide whether that has happened to you or to someone you love. If it has, we have some strategies that may help.

Part 1

Understanding the Almost Alcoholic

1 What Is Almost Alcoholic?Geraldo, thirty-eight, had worked in the commercial real estate development field since graduating college with a degree in business management. His employer had offices and developed properties in the New England area. For many years the firm did nothing but grow, and Geraldo advanced along with it. He was now in charge of overseeing the budgets for new projects in three states. There was only one problem: for the last three years the number of new projects that the company was able to win contracts for had steadily dwindled as the US economy sank into a protracted slump.

Part of Geraldo’s job involved traveling to the various project sites. There, he’d get a sense for whether the project was on schedule, which in most cases also meant that it would be on budget. His employer had found that being on site was the best way to monitor this activity. It was a strategy that had proven successful over time.

When Geraldo traveled, he lived on an expense account. The company put him up in moderately priced hotels and paid a reasonable daily stipend for food. Geraldo also could do some entertaining of customers, mostly taking them to dinner or out for drinks. It was in this context that Geraldo found himself becoming an almost alcoholic.

Geraldo’s drinking was not excessive—at least not in his own mind. And if you were to ask the customers he entertained, it’s doubtful that any of them would say he ever got drunk. Nevertheless, Geraldo, who ten years earlier was someone who would only drink a cocktail or two on weekends, was now a man who had one or two cocktails almost every night—whether he was traveling or not. Was this a problem? Not from Geraldo’s point of view. He’d never, for example, even considered that he might be a

Was this a problem? Not from Geraldo’s point of view. He’d never, for example, even considered that he might be a problem drinker.

On the other hand, Geraldo’s habit of

Enjoying the preview?

Page 1 of 1

Almost Alcoholic - HelpGuide.org

A Harvard Health article

Is My (or My Loved One's) Drinking a Problem?

It is very possible to have a drinking problem that is not defined or described as “Alcoholic.” Many people use alcohol to deal with stress but do not realize that it exacerbates the problems in their lives. There are techniques and therapies available to help you to lessen your dependence on alcohol and rediscover balance in your life.

Are you Almost Alcoholic?

Some people believe there are only two kinds of people in the world: alcoholics and non-alcoholics. Many also believe that we are either born alcoholics or we are not. This has been a prevailing view for a long time, and though this statement may seem dramatic to some, it does have some basis in reality. Those who hold these beliefs tend to be people who have experienced or witnessed the most severe symptoms and/or the most severe consequences of drinking, such as:

Those who hold these beliefs tend to be people who have experienced or witnessed the most severe symptoms and/or the most severe consequences of drinking, such as:

- Being unable to stop drinking, beginning from the first time he or she had a drink

- Repeatedly having blackouts (i.e. can’t remember the next day what happened) after having only a few drinks

- Being arrested multiple times for driving while intoxicated

- Becoming violent on more than one occasion when drinking

We know from our own clinical experience that there are people who develop severe alcohol drinking patterns and behaviors such as the ones just described. These are true alcoholics. However, there are also a large number of people who don’t meet the accepted criteria for diagnosing alcoholism, but fall into a grey area of problem drinking. These are the almost alcoholic.

With over 25,000 licensed counselors, BetterHelp has a therapist that fits your needs. It's easy, affordable, and convenient.

GET 20% OFF

Online-Therapy.com is a complete toolbox of support, when you need it, on your schedule. It only takes a few minutes to sign up.

GET 20% OFF

Teen Counseling is an online therapy service for teens and young adults. Connect with your counselor by video, phone, or chat.

GET 20% OFF

True alcoholics vs. almost alcoholics

Anyone who drinks heavily is at risk for adverse health consequences, but some people appear to face a heightened risk for developing alcohol-related health problems. The reason appears to be largely biological, though environmental factors also likely play a role in this difference. Researchers have found, for example, that people differ in how their bodies metabolize alcohol. Since our biological make up is determined at birth, there is some truth in the idea that we have certain traits that make us more (or less) vulnerable to the effects of alcohol.

Our discovery of the almost alcoholic came through our many years of working not only with people who had the kinds of drinking problems just described, but also with a much larger group of people with a variety of drinking patterns that didn’t meet the criteria for alcoholism. As noted earlier, the majority of this larger group came to us not because they were concerned (or because others had expressed concern) about their drinking but for help with some other problem. The connection between the problems they sought help for and their drinking emerged later. Let’s look at a couple of examples:

As noted earlier, the majority of this larger group came to us not because they were concerned (or because others had expressed concern) about their drinking but for help with some other problem. The connection between the problems they sought help for and their drinking emerged later. Let’s look at a couple of examples:

Jennifer’s story

Jennifer, 41, was married with two children, an eleven-year-old son and a nine-year old daughter. Jennifer’s was a typical, two-income contemporary family. She had a middle management job in a large real estate development and management company, while her husband, Dan, worked in the information technology department of a large university. As was true for most of the couples they knew, they struggled with balancing the demands of work with those of parenting, not to mention housekeeping. They enjoyed their life in a comfortable suburban community with good schools and access to recreation; at the same time, both Jennifer and Dan sometimes expressed that they found life on a “treadmill” difficult.

Dan and Jen had met in college during their junior years and married a year after graduating. As college students, they’d enjoyed partying as much as most of their friends, but had never gone “over the top” with it. They’d each known the occasional hangover, especially as freshman, and both enjoyed meeting friends for tailgating parties at football games after graduation.

Jen did not drink at all during her pregnancies. However, after her second child was born, and after she returned to work following a six-week maternity leave, she joined Dan in his routine of sipping a glass of wine while they “decompressed” after work. That meant unloading the kids, making dinner, supervising homework, getting ready for the next day, and so on. Then, after the kids were in bed, Jen would have a second glass of wine, and sometimes a third. She told us that for a number of years this was an effective way for her to release the stress that built up over the course of the day. She also felt that the third glass of wine helped her sleep better.

When Jen sought therapy, it was not because of her drinking—which she still regarded as normal, and indeed helpful, given her high-pressure lifestyle. Jen was referred by her primary care physician, with whom she had shared her concerns about not sleeping well. Not sleeping well left her feeling “wired” the next day. That pattern then led her to feel increasingly depressed, which was reflected in a shortened temper (especially with the children), chronic feelings of fatigue, and a complaint from Dan that their sex life was “evaporating.” She’d asked her doctor about sleeping medications, or perhaps an antidepressant. The doctor said she would consider that, but first she wanted Jen to talk with a counselor.

Jen is a good example of this large group of people whom we have come to know well in our offices, people whose drinking emerges as a factor in their presenting problems. She did not make an appointment with a counselor because she was worried about her drinking.

Marcus’s story

Marcus, nineteen, had done well in high school despite struggling with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). He’d avoided alcohol during those years—he’d been warned that his ADHD medication didn’t mix well with liquor—but once he got to college, he began drinking, usually in binges and in the company of friends.

At first, the downside of Marcus’s drinking was fairly subtle: his grades slipped a bit, and sometimes missed classes the morning after drinking. On the upside, he became more outgoing when he drank and was less shy than he’d been through his high school years. A complicating factor for Marcus’s situation was his age: drinking in the college-age population typically involves a great deal of binge drinking, which is often organized around drinking games (Binge drinkingis defined by the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism as a drinking pattern corresponding to five or more drinks for a male and four or more for a female within about two hours, resulting in a blood alcohol level of . 08 percent or more.) One such game is “beer pong” in which opponents try to bounce a Ping-Pong ball into one another’s full glass of beer. When your opponent lands his (or her) ball in your beer you have to drink it all. Then another round begins.

08 percent or more.) One such game is “beer pong” in which opponents try to bounce a Ping-Pong ball into one another’s full glass of beer. When your opponent lands his (or her) ball in your beer you have to drink it all. Then another round begins.

Marcus found games like beer pong fun. It was socially acceptable and an easy way for him to overcome his shyness. Being drunk also made it easier for him to talk to girls, which further reinforced his behavior.

By the middle of his second semester at school, though, Marcus was in danger of flunking one course and was barely passing three others. To make matters worse, after drinking way too much one Friday night at a fraternity party, he got into a fight with a guy who thought Marcus was flirting with his girlfriend. Words were exchanged, but instead of it ending there, Marcus shoved the guy and then punches were thrown. Fearing it could lead to a brawl, someone dialed 911 for the campus police.

In accordance with the college’s zero tolerance policy toward violence on campus, Marcus was barred from living on campus the following semester. While he did manage to avoid flunking out, he finished that first year with a grade point average that jeopardized his chances of getting into the pharmacy school he’d always dreamed of attending.

While he did manage to avoid flunking out, he finished that first year with a grade point average that jeopardized his chances of getting into the pharmacy school he’d always dreamed of attending.

Research consistently shows that people tend to drink the heaviest in their late teens and early-to-mid twenties. Young adults, both male and female, are especially likely to binge drink. For some of these youths, such drinking may lead to other serious problems. For example, some studies have shown that a region in the brain associated with learning and memory—the hippocampus—is smaller in people who began drinking as adolescents. And studies of teens who were treated for alcohol withdrawal showed that they were more likely to have memory problems than adolescents who did not drink.

Unfortunately, what some college students consider social drinking may include various binge-drinking “games.” Not every college student binge drinks, but this behavior tends to be fairly widespread and relatively tolerated by peers on college campuses. It is not uncommon for students to get drunk to the point of passing out. Because of that social context, and also because his drinking was mostly limited to weekends, Marcus viewed his own drinking as normal. He thought he was just doing what a lot of other students did, so how could he have a drinking problem? The reality is that most college students who binge on alcohol will pass through this phase and emerge in adulthood as normal social drinkers. Some of the heaviest drinkers may suffer some memory or learning problems connected to their earlier alcohol use, though they may never make this connection themselves. A few will go on to become full-blown alcoholics. And some, like Marcus, will become almost alcoholics.

It is not uncommon for students to get drunk to the point of passing out. Because of that social context, and also because his drinking was mostly limited to weekends, Marcus viewed his own drinking as normal. He thought he was just doing what a lot of other students did, so how could he have a drinking problem? The reality is that most college students who binge on alcohol will pass through this phase and emerge in adulthood as normal social drinkers. Some of the heaviest drinkers may suffer some memory or learning problems connected to their earlier alcohol use, though they may never make this connection themselves. A few will go on to become full-blown alcoholics. And some, like Marcus, will become almost alcoholics.

Marcus’s experiences—getting into a fight and struggling with academics—were clearly consequences of his drinking. All by themselves, they would not have qualified him for diagnosis of alcoholism. In other words, he didn’t fit into the accepted diagnostic “box.” If Dr. Doyle had concluded that Marcus didn't have a drinking problem, that young man could have concluded that the negative things that were happening to him were just a matter of bad luck—being in the wrong place at the wrong time—and decided that there was no need to change his drinking behavior. Things could well have continued to go downhill from there. But by introducing Marcus to the concept of the almost alcoholic, Dr. Doyle was able help Marcus see the connection between his drinking and its consequences. From there they could discuss whether Marcus ought to consider doing something about his drinking, even if he was not an alcoholic.

Doyle had concluded that Marcus didn't have a drinking problem, that young man could have concluded that the negative things that were happening to him were just a matter of bad luck—being in the wrong place at the wrong time—and decided that there was no need to change his drinking behavior. Things could well have continued to go downhill from there. But by introducing Marcus to the concept of the almost alcoholic, Dr. Doyle was able help Marcus see the connection between his drinking and its consequences. From there they could discuss whether Marcus ought to consider doing something about his drinking, even if he was not an alcoholic.

Adapted with permission from Almost Alcoholic: Is My (or My Loved One's) Drinking a Problem?

Last updated: December 6, 2022

Alcoholism and drug addiction. Statistics of the problem in Russia and regions

Alcoholism and drug addiction

Alcoholism and drug addiction

in

Russia

Russia

Alcoholism and drug addiction are dangerous and widespread diseases associated with dependence on the use of psychoactive substances (including alcohol). Narcological disorders, in addition to alcoholism and drug addiction, include alcoholic psychoses, harmful use of alcohol and drugs, substance abuse. The damage from these diseases is aggravated by the variety of their medical and social consequences: regular use of alcohol and / or drugs causes a number of chronic diseases, and also poses a direct threat to life: due to accidental poisoning, suicide,

Narcological disorders, in addition to alcoholism and drug addiction, include alcoholic psychoses, harmful use of alcohol and drugs, substance abuse. The damage from these diseases is aggravated by the variety of their medical and social consequences: regular use of alcohol and / or drugs causes a number of chronic diseases, and also poses a direct threat to life: due to accidental poisoning, suicide,

, etc. Unlike most other non-communicable diseases, in addition to the patients themselves, the people around them are often exposed to danger (primarily family and domestic violence).

When analyzing the resources to combat alcoholism and drug addiction, three areas can be distinguished. The first level is associated with the prevention of alcohol and drug use, the second with the treatment of consumers at different stages of addiction, the third with the rehabilitation and resocialization of patients. The second and third levels are inextricably linked: in narcology, the rehabilitation process begins simultaneously with treatment. nine0005

nine0005

1 898 395 people

?

General incidence of narcological disorders (alcoholism, drug addiction, alcoholic psychosis, harmful drug use) in the population of the Russian Federation. General incidence - the total number of cases of diseases detected (registered) during the year. Source - NSC of Narcology - branch of the Federal State Budgetary Institution "National Medical Research Center for Psychiatry and Narcology named after N.N. V.P. Serbsky" of the Ministry of Health of Russia

2019

Visited with alcohol and drug disorders

51,996 people

?

Rosstat data, the sum of deaths from causes caused by alcohol (17 causes) and drugs (3 causes). This number does not include most of the deaths associated with alcohol and drugs: part of the fatal traffic accidents, murders, suicides; diseases indirectly associated with alcohol and drugs, etc.

2019

Died from alcohol and drug use

5,076 people

?

Calculation "To be exact"; the ratio of the number of psychiatrists-narcologists (individuals) to the population over 15 years old. The source of data on the number of doctors is the NSC of Narcology, a branch of the Federal State Budgetary Institution “National Medical Research Center for Psychiatry and Narcology named after N.N. V.P. Serbian" of the Ministry of Health of Russia; source of population data - EMISS.

The source of data on the number of doctors is the NSC of Narcology, a branch of the Federal State Budgetary Institution “National Medical Research Center for Psychiatry and Narcology named after N.N. V.P. Serbian" of the Ministry of Health of Russia; source of population data - EMISS.

2019

Number of addiction psychiatrists

Methodology

?

A - low severity of the problem

B - the problem is expressed below the average

C - the average severity of the problem

D - the problem is expressed above the average

E - high severity of the problem

Comparison of regions

Analytic report

All data

The project was created and supported by a team of analysts and programmers from the Need Help Charitable Foundation. The foundation exists on donations. Please support our work. nine0005

Support the project

We use cookies to improve the functioning of the site and its interaction with users. Continuing work with site, you allow the use of cookies. Please read the policy for To learn more.

Continuing work with site, you allow the use of cookies. Please read the policy for To learn more.

Home - Republican Narcological Dispensary

Republican Narcological Dispensary

364046, Chechnya, Grozny, st. K. Aidamirova (Verkhoyanskaya), 10

Phone: 8 (8712) 29-55-18 (reception from 9:00 to 16:50)

Phone/Fax: 8 (8712) 29-51-01 (for inquiries from 9:00 to 16:00: 50)

Call Center: 8 (928) 803-53-03

8 (928) 784-57-20 (medical examination room for intoxication)

Time of reception of citizens

Full details and directions

Feedback:

E-mail: [email protected] (general, personal)

[email protected] (for inquiries)

Events

The Accessible Environment total test will test the knowledge of Russians in the field of inclusion

"Accessible Environment", designed to draw the attention of Russian citizens to the rights and needs of people with disabilities. During the Decade of the Disabled, all regions of Russia will test knowledge on inclusive communication and organizing an accessible environment, as well as organize educational events and campaigns aimed at improving the quality of life of people with disabilities. nine0005

During the Decade of the Disabled, all regions of Russia will test knowledge on inclusive communication and organizing an accessible environment, as well as organize educational events and campaigns aimed at improving the quality of life of people with disabilities. nine0005

Read more

Poll

How do you rate the quality of services in the dispensary?

Total votes: 417

Good

Satisfactory

unsatisfactory

Dalsaev Muslim Mussaevich

chief doctor of the Republican Narcological Dispensary

B 1989year graduated from secondary school No. 1 in Grozny with a silver medal.

1987 - 1989 - orderly in the admission department of the republican hospital

Grozny.

1989 - entered the Stavropol State Medical Institute.