Do eating disorders work

Eating disorders - Symptoms and causes

Overview

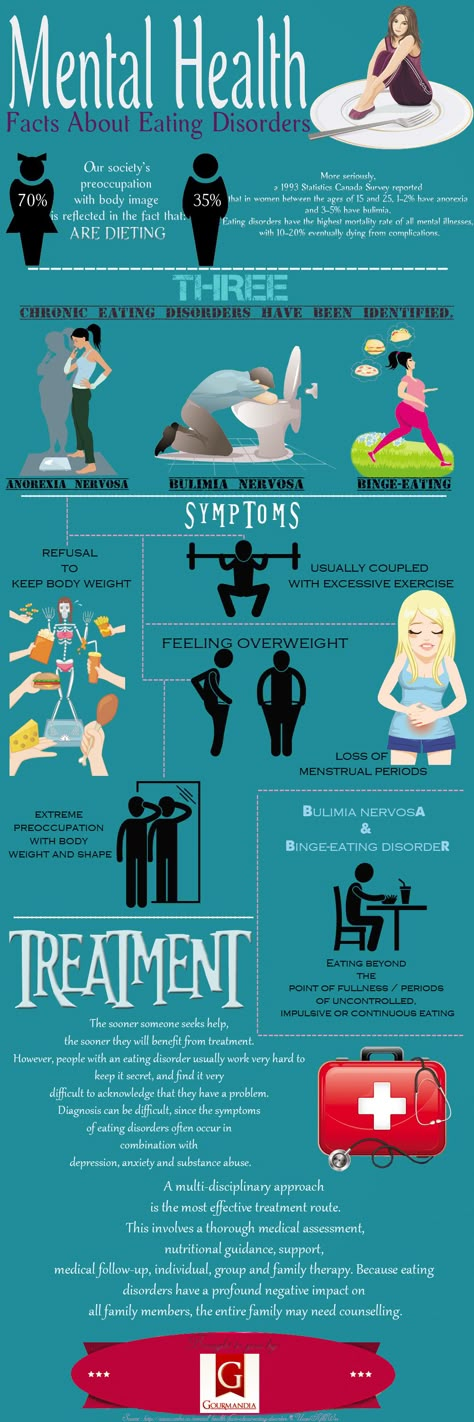

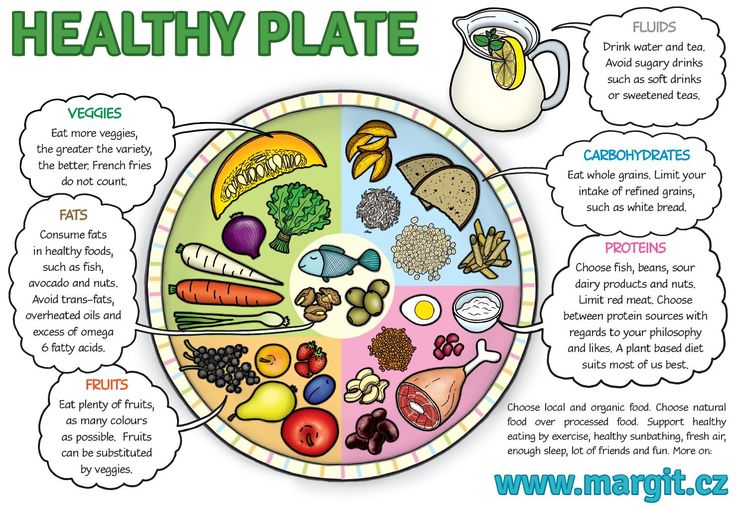

Eating disorders are serious conditions related to persistent eating behaviors that negatively impact your health, your emotions and your ability to function in important areas of life. The most common eating disorders are anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder.

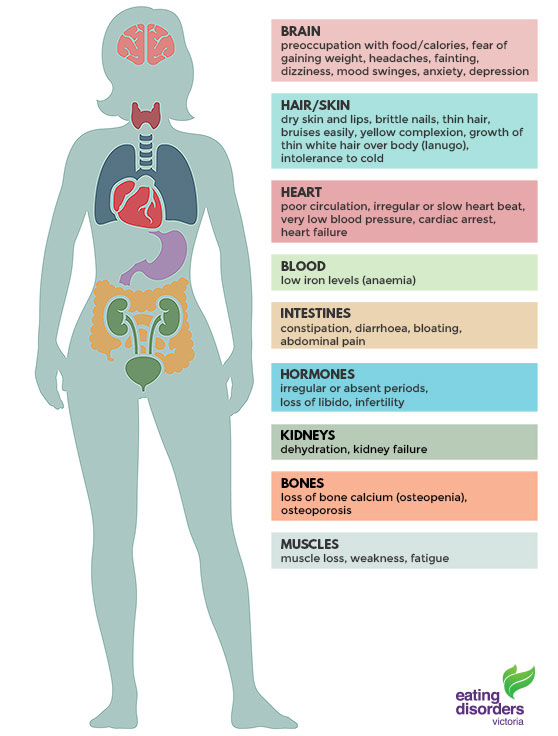

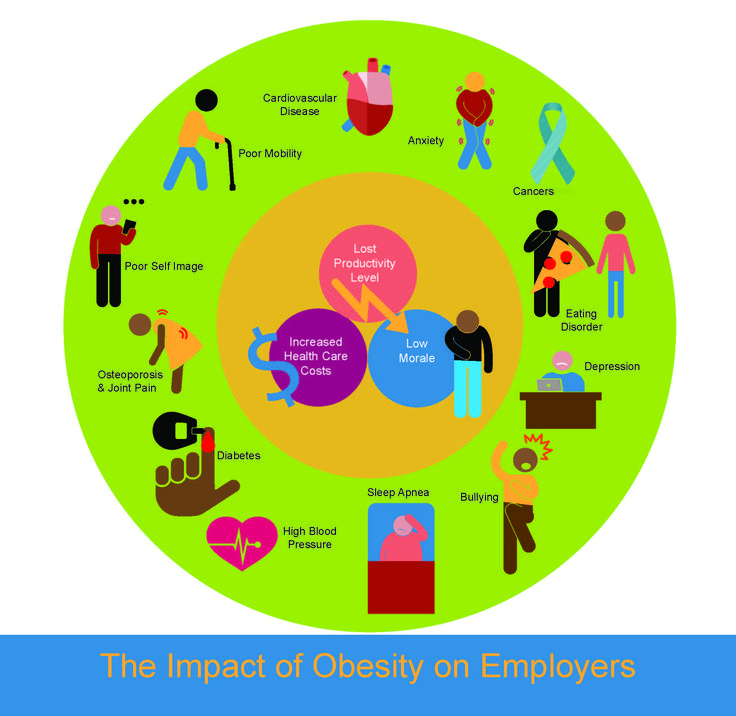

Most eating disorders involve focusing too much on your weight, body shape and food, leading to dangerous eating behaviors. These behaviors can significantly impact your body's ability to get appropriate nutrition. Eating disorders can harm the heart, digestive system, bones, and teeth and mouth, and lead to other diseases.

Eating disorders often develop in the teen and young adult years, although they can develop at other ages. With treatment, you can return to healthier eating habits and sometimes reverse serious complications caused by the eating disorder.

Products & Services

- Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Symptoms

Symptoms vary, depending on the type of eating disorder. Anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge-eating disorder are the most common eating disorders. Other eating disorders include rumination disorder and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder.

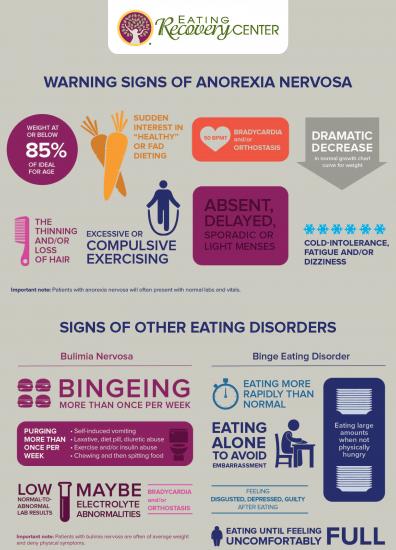

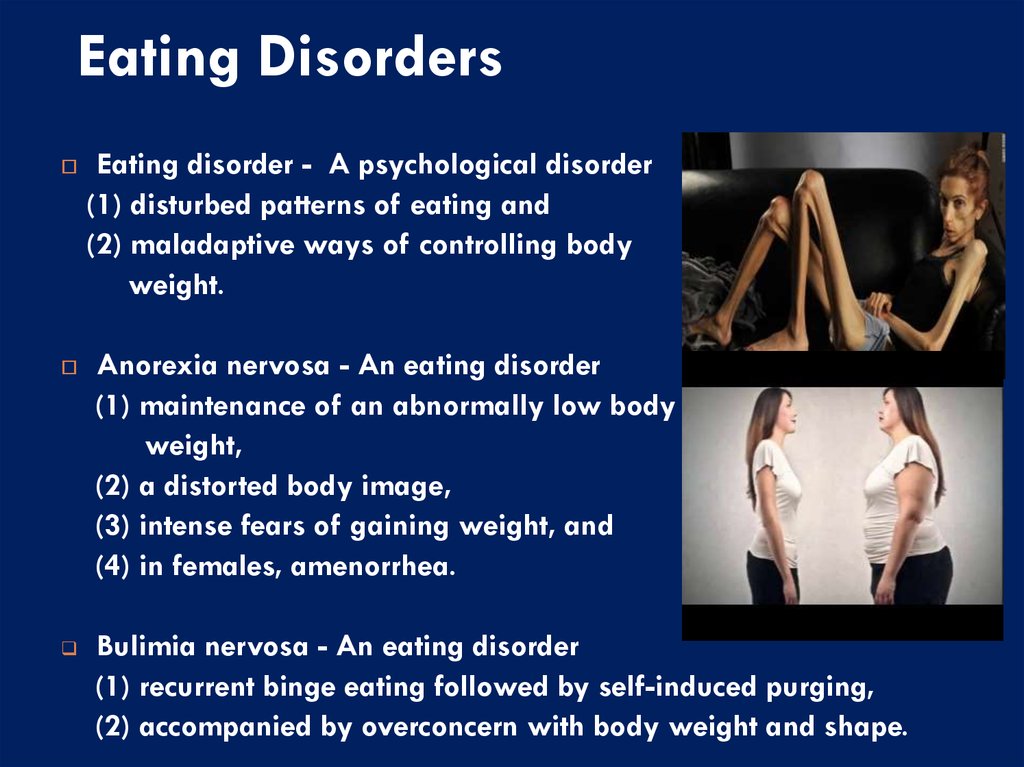

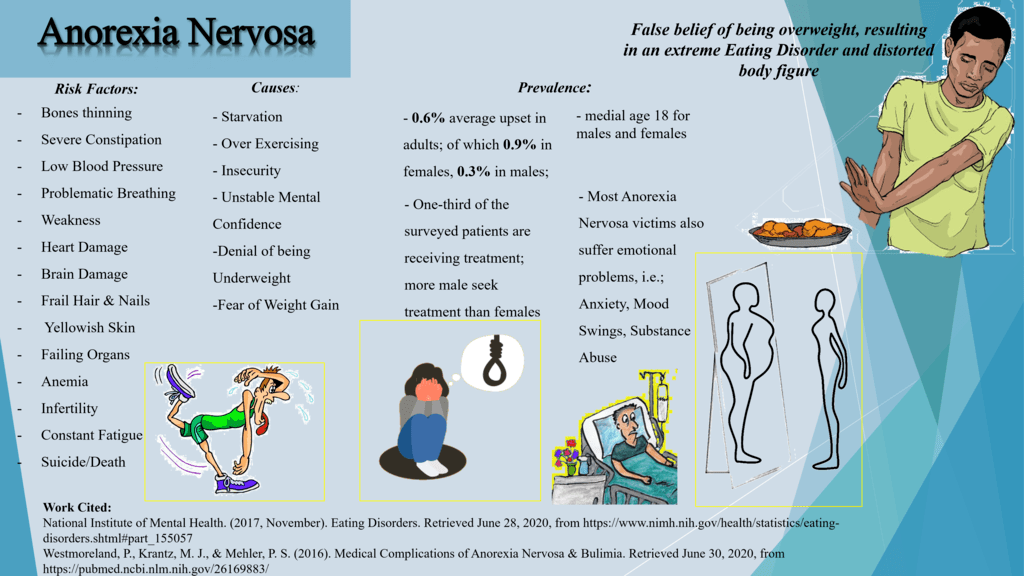

Anorexia nervosa

Anorexia (an-o-REK-see-uh) nervosa — often simply called anorexia — is a potentially life-threatening eating disorder characterized by an abnormally low body weight, intense fear of gaining weight, and a distorted perception of weight or shape. People with anorexia use extreme efforts to control their weight and shape, which often significantly interferes with their health and life activities.

When you have anorexia, you excessively limit calories or use other methods to lose weight, such as excessive exercise, using laxatives or diet aids, or vomiting after eating. Efforts to reduce your weight, even when underweight, can cause severe health problems, sometimes to the point of deadly self-starvation.

Bulimia nervosa

Bulimia (boo-LEE-me-uh) nervosa — commonly called bulimia — is a serious, potentially life-threatening eating disorder. When you have bulimia, you have episodes of bingeing and purging that involve feeling a lack of control over your eating. Many people with bulimia also restrict their eating during the day, which often leads to more binge eating and purging.

When you have bulimia, you have episodes of bingeing and purging that involve feeling a lack of control over your eating. Many people with bulimia also restrict their eating during the day, which often leads to more binge eating and purging.

During these episodes, you typically eat a large amount of food in a short time, and then try to rid yourself of the extra calories in an unhealthy way. Because of guilt, shame and an intense fear of weight gain from overeating, you may force vomiting or you may exercise too much or use other methods, such as laxatives, to get rid of the calories.

If you have bulimia, you're probably preoccupied with your weight and body shape, and may judge yourself severely and harshly for your self-perceived flaws. You may be at a normal weight or even a bit overweight.

Binge-eating disorder

When you have binge-eating disorder, you regularly eat too much food (binge) and feel a lack of control over your eating. You may eat quickly or eat more food than intended, even when you're not hungry, and you may continue eating even long after you're uncomfortably full.

After a binge, you may feel guilty, disgusted or ashamed by your behavior and the amount of food eaten. But you don't try to compensate for this behavior with excessive exercise or purging, as someone with bulimia or anorexia might. Embarrassment can lead to eating alone to hide your bingeing.

A new round of bingeing usually occurs at least once a week. You may be normal weight, overweight or obese.

Rumination disorder

Rumination disorder is repeatedly and persistently regurgitating food after eating, but it's not due to a medical condition or another eating disorder such as anorexia, bulimia or binge-eating disorder. Food is brought back up into the mouth without nausea or gagging, and regurgitation may not be intentional. Sometimes regurgitated food is rechewed and reswallowed or spit out.

The disorder may result in malnutrition if the food is spit out or if the person eats significantly less to prevent the behavior. The occurrence of rumination disorder may be more common in infancy or in people who have an intellectual disability.

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder

This disorder is characterized by failing to meet your minimum daily nutrition requirements because you don't have an interest in eating; you avoid food with certain sensory characteristics, such as color, texture, smell or taste; or you're concerned about the consequences of eating, such as fear of choking. Food is not avoided because of fear of gaining weight.

The disorder can result in significant weight loss or failure to gain weight in childhood, as well as nutritional deficiencies that can cause health problems.

When to see a doctor

An eating disorder can be difficult to manage or overcome by yourself. Eating disorders can virtually take over your life. If you're experiencing any of these problems, or if you think you may have an eating disorder, seek medical help.

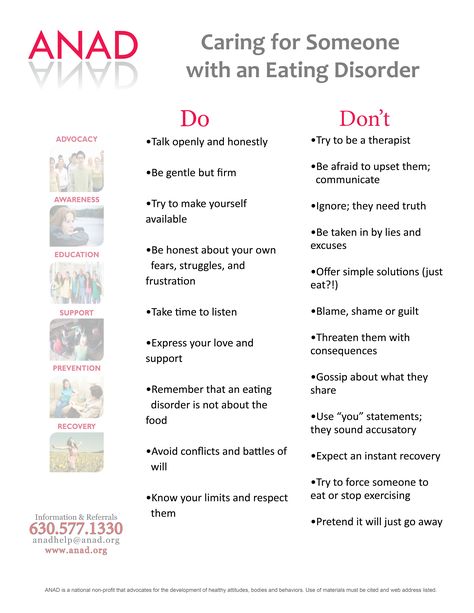

Urging a loved one to seek treatment

Unfortunately, many people with eating disorders may not think they need treatment. If you're worried about a loved one, urge him or her to talk to a doctor. Even if your loved one isn't ready to acknowledge having an issue with food, you can open the door by expressing concern and a desire to listen.

Even if your loved one isn't ready to acknowledge having an issue with food, you can open the door by expressing concern and a desire to listen.

Be alert for eating patterns and beliefs that may signal unhealthy behavior, as well as peer pressure that may trigger eating disorders. Red flags that may indicate an eating disorder include:

- Skipping meals or making excuses for not eating

- Adopting an overly restrictive vegetarian diet

- Excessive focus on healthy eating

- Making own meals rather than eating what the family eats

- Withdrawing from normal social activities

- Persistent worry or complaining about being fat and talk of losing weight

- Frequent checking in the mirror for perceived flaws

- Repeatedly eating large amounts of sweets or high-fat foods

- Use of dietary supplements, laxatives or herbal products for weight loss

- Excessive exercise

- Calluses on the knuckles from inducing vomiting

- Problems with loss of tooth enamel that may be a sign of repeated vomiting

- Leaving during meals to use the toilet

- Eating much more food in a meal or snack than is considered normal

- Expressing depression, disgust, shame or guilt about eating habits

- Eating in secret

If you're worried that your child may have an eating disorder, contact his or her doctor to discuss your concerns. If needed, you can get a referral to a qualified mental health professional with expertise in eating disorders, or if your insurance permits it, contact an expert directly.

If needed, you can get a referral to a qualified mental health professional with expertise in eating disorders, or if your insurance permits it, contact an expert directly.

Request an Appointment at Mayo Clinic

Causes

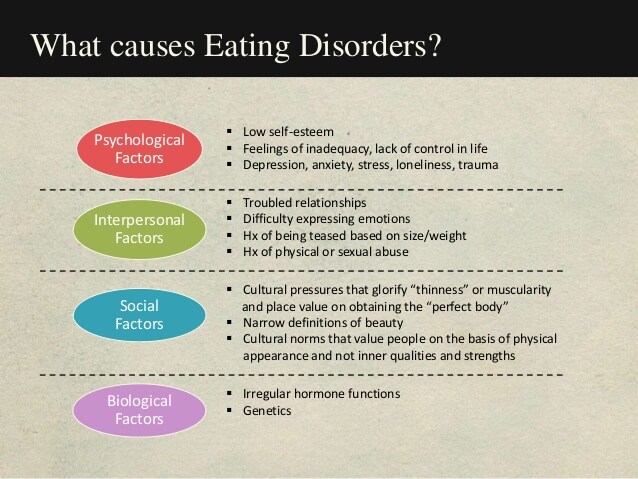

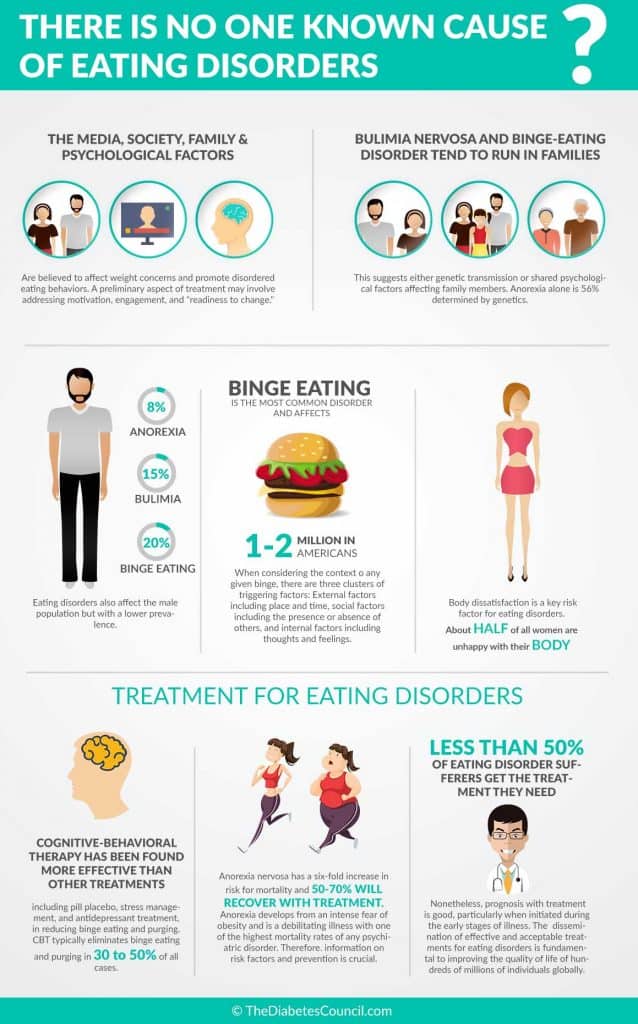

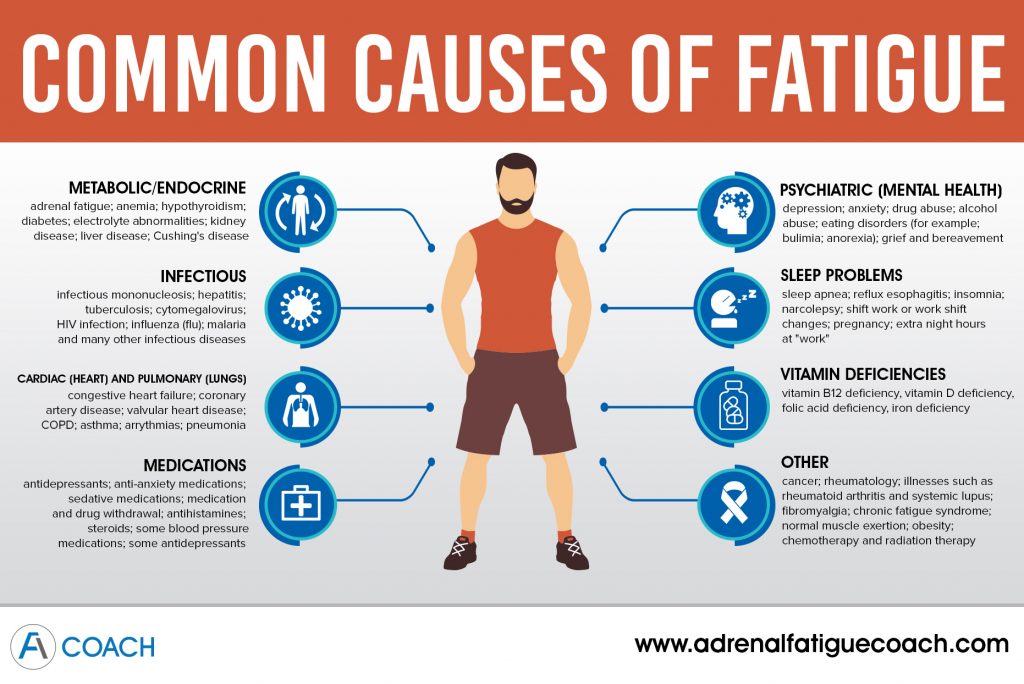

The exact cause of eating disorders is unknown. As with other mental illnesses, there may be many causes, such as:

- Genetics and biology. Certain people may have genes that increase their risk of developing eating disorders. Biological factors, such as changes in brain chemicals, may play a role in eating disorders.

- Psychological and emotional health. People with eating disorders may have psychological and emotional problems that contribute to the disorder. They may have low self-esteem, perfectionism, impulsive behavior and troubled relationships.

Risk factors

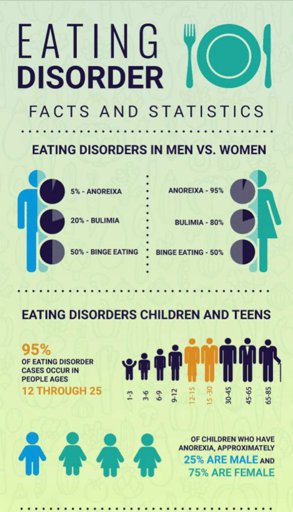

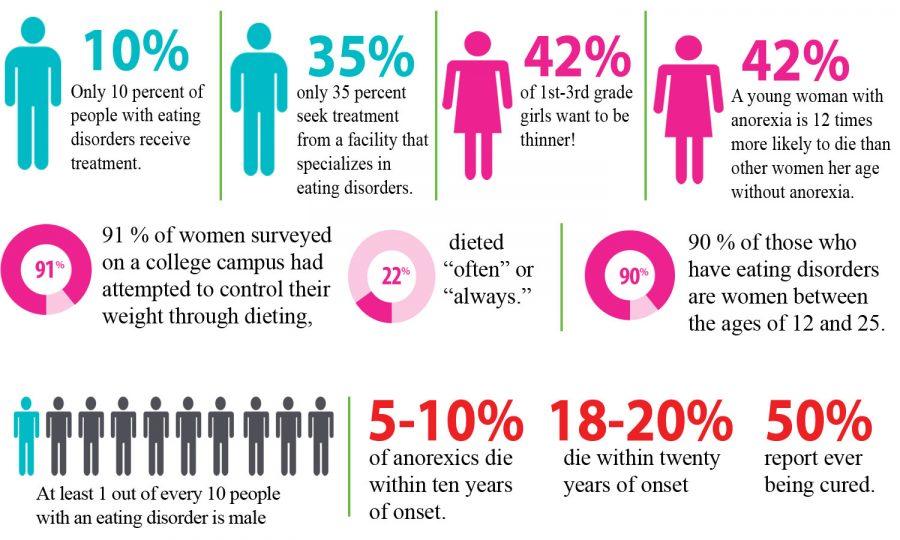

Teenage girls and young women are more likely than teenage boys and young men to have anorexia or bulimia, but males can have eating disorders, too. Although eating disorders can occur across a broad age range, they often develop in the teens and early 20s.

Although eating disorders can occur across a broad age range, they often develop in the teens and early 20s.

Certain factors may increase the risk of developing an eating disorder, including:

- Family history. Eating disorders are significantly more likely to occur in people who have parents or siblings who've had an eating disorder.

- Other mental health disorders. People with an eating disorder often have a history of an anxiety disorder, depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

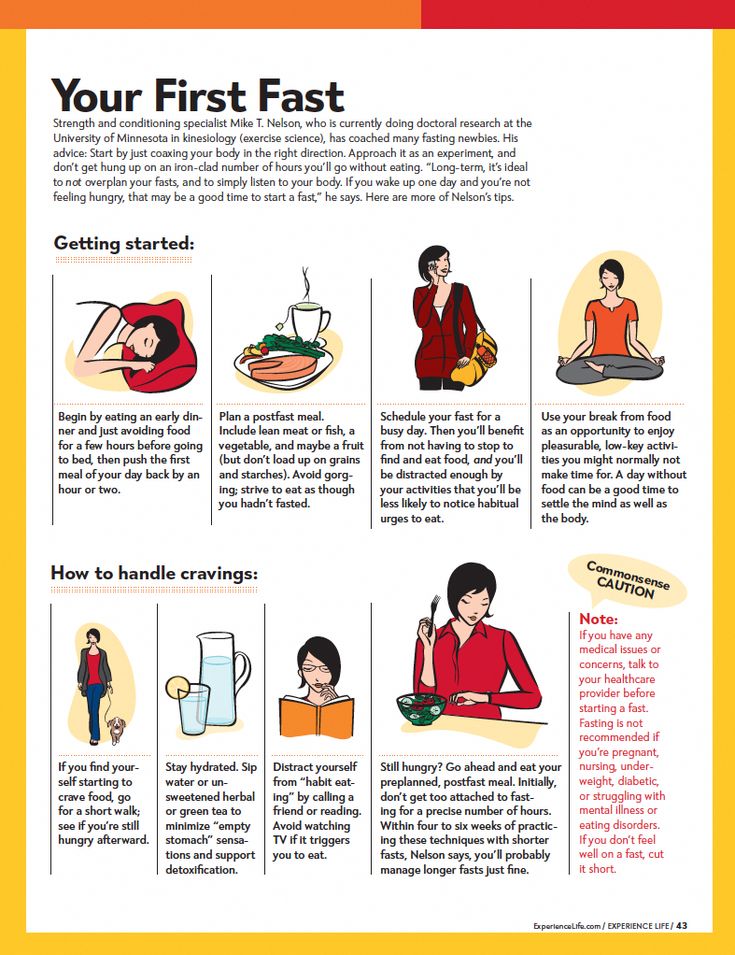

- Dieting and starvation. Dieting is a risk factor for developing an eating disorder. Starvation affects the brain and influences mood changes, rigidity in thinking, anxiety and reduction in appetite. There is strong evidence that many of the symptoms of an eating disorder are actually symptoms of starvation. Starvation and weight loss may change the way the brain works in vulnerable individuals, which may perpetuate restrictive eating behaviors and make it difficult to return to normal eating habits.

- Stress. Whether it's heading off to college, moving, landing a new job, or a family or relationship issue, change can bring stress, which may increase your risk of an eating disorder.

Complications

Eating disorders cause a wide variety of complications, some of them life-threatening. The more severe or long lasting the eating disorder, the more likely you are to experience serious complications, such as:

- Serious health problems

- Depression and anxiety

- Suicidal thoughts or behavior

- Problems with growth and development

- Social and relationship problems

- Substance use disorders

- Work and school issues

- Death

Prevention

Although there's no sure way to prevent eating disorders, here are some strategies to help your child develop healthy-eating behaviors:

- Avoid dieting around your child. Family dining habits may influence the relationships children develop with food.

Eating meals together gives you an opportunity to teach your child about the pitfalls of dieting and encourages eating a balanced diet in reasonable portions.

Eating meals together gives you an opportunity to teach your child about the pitfalls of dieting and encourages eating a balanced diet in reasonable portions. - Talk to your child. For example, there are numerous websites that promote dangerous ideas, such as viewing anorexia as a lifestyle choice rather than an eating disorder. It's crucial to correct any misperceptions like this and to talk to your child about the risks of unhealthy eating choices.

- Cultivate and reinforce a healthy body image in your child, whatever his or her shape or size. Talk to your child about self-image and offer reassurance that body shapes can vary. Avoid criticizing your own body in front of your child. Messages of acceptance and respect can help build healthy self-esteem and resilience that will carry children through the rocky periods of the teen years.

- Enlist the help of your child's doctor. At well-child visits, doctors may be able to identify early indicators of an eating disorder.

They can ask children questions about their eating habits and satisfaction with their appearance during routine medical appointments, for instance. These visits should include checks of height and weight percentiles and body mass index, which can alert you and your child's doctor to any significant changes.

They can ask children questions about their eating habits and satisfaction with their appearance during routine medical appointments, for instance. These visits should include checks of height and weight percentiles and body mass index, which can alert you and your child's doctor to any significant changes.

If you notice a family member or friend who seems to show signs of an eating disorder, consider talking to that person about your concern for his or her well-being. Although you may not be able to prevent an eating disorder from developing, reaching out with compassion may encourage the person to seek treatment.

By Mayo Clinic Staff

Types, Causes, Treatment, and Recovery

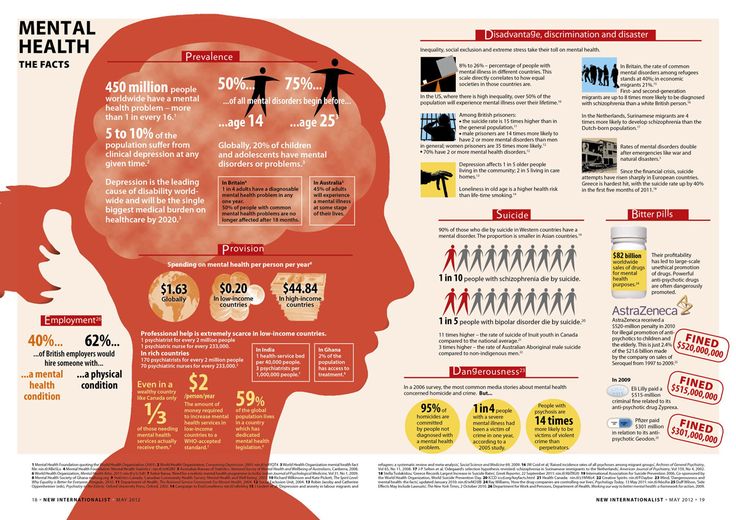

Although the term “eating” is in the name, eating disorders are about more than food. They’re complex mental health conditions that often require the intervention of medical and psychological experts to alter their course.

These disorders are described in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fifth edition (DSM-5) (1).

In the United States alone, an estimated 28 million Americans have or have had an eating disorder at some point in their life (2).

This article describes six of the most common types of eating disorders and their symptoms.

Eating disorders are a range of psychological conditions that cause unhealthy eating habits to develop. They might start with an obsession with food, body weight, or body shape (3).

In severe cases, eating disorders can cause serious health consequences and may even result in death if left untreated. In fact, eating disorders are among the deadliest mental illnesses, second to opioid overdose (4).

People with eating disorders can have a variety of symptoms. Common symptoms include severe restriction of food, food binges, and purging behaviors like vomiting or overexercising.

Although eating disorders can affect people of any gender at any life stage, they’re increasingly common in men and gender nonconforming people. These populations often seek treatment at lower rates or may not report their eating disorder symptoms at all (5, 6).

Different types of eating disorders have different symptoms, but each condition involves an extreme focus on issues related to food and eating, and some involve an extreme focus on weight.

This preoccupation with food and weight may make it hard to focus on other aspects of life (3).

Mental and behavioral signs may include (7):

- dramatic weight loss

- concern about eating in public

- preoccupation with weight, food, calories, fat grams, or dieting

- complaints of constipation, cold intolerance, abdominal pain, lethargy, or excess energy

- excuses to avoid mealtime

- intense fear of weight gain or being “fat”

- dressing in layers to hide weight loss or stay warm

- severely limiting and restricting the amount and types of food consumed

- refusing to eat certain foods

- denying feeling hungry

- expressing a need to “burn off” calories

- repeatedly weighing oneself

- patterns of binge eating and purging

- developing rituals around food

- excessively exercising

- cooking meals for others without eating

- missing menstrual periods (in people who would typically menstruate)

Physical signs may include (7):

- stomach cramps and other gastrointestinal symptoms

- difficulty concentrating

- atypical lab test results (anemia, low thyroid levels, low hormone levels, low potassium, low blood cell counts, slow heart rate)

- dizziness

- fainting

- feeling cold all the time

- sleep irregularities

- menstrual irregularities

- calluses across the tops of the finger joints (a sign of inducing vomiting)

- dry skin

- dry, thin nails

- thinning hair

- muscle weakness

- poor wound healing

- poor immune system function

Experts believe that a variety of factors may contribute to eating disorders.

One of these is genetics. People who have a sibling or parent with an eating disorder seem to be at an increased risk of developing one (3).

Personality traits are another factor. In particular, neuroticism, perfectionism, and impulsivity are three personality traits often linked to a higher risk of developing an eating disorder, according to a 2015 research review (8).

Other potential causes include perceived pressures to be thin, cultural preferences for thinness, and exposure to media promoting these ideals (8).

More recently, experts have proposed that differences in brain structure and biology may also play a role in the development of eating disorders. In particular, levels of the brain messaging chemicals serotonin and dopamine may be factors (9).

However, more studies are needed before strong conclusions can be made.

Eating disorders are a group of related conditions involving extreme food and weight issues, but each disorder has unique symptoms and diagnosis criteria. Here are six of the most common eating disorders and their symptoms.

Here are six of the most common eating disorders and their symptoms.

Anorexia nervosa is likely the most well-known eating disorder.

It generally develops during adolescence or young adulthood and tends to affect more women than men (10).

People with anorexia generally view themselves as overweight, even if they’re dangerously underweight. They tend to constantly monitor their weight, avoid eating certain types of foods, and severely restrict their calorie intake.

Common symptoms of anorexia nervosa include (1):

- very restricted eating patterns

- intense fear of gaining weight or persistent behaviors to avoid gaining weight, despite being underweight

- a relentless pursuit of thinness and unwillingness to maintain a healthy weight

- a heavy influence of body weight or perceived body shape on self-esteem

- a distorted body image, including denial of being seriously underweight

However, it’s important to note that weight should not be the major focus of diagnosing someone with anorexia.

Using body mass index as a factor in diagnosis is outdated because people who are categorized as “normal” or “overweight” can have the same risks.

In atypical anorexia, for example, a person may meet the criteria for anorexia but not be underweight despite significant weight loss (7).

Obsessive-compulsive symptoms are also often present. For instance, many people with anorexia are preoccupied with constant thoughts about food, and some may obsessively collect recipes or hoard food.

They may also have difficulty eating in public and exhibit a strong desire to control their environment, limiting their ability to be spontaneous (3).

Anorexia is officially categorized into two subtypes — the restricting type and the binge eating and purging type (1).

Individuals with the restricting type lose weight solely through dieting, fasting, or excessive exercise.

Individuals with the binge eating and purging type may binge on large amounts of food or eat very little. In both cases, after they eat, they purge using activities such as vomiting, taking laxatives or diuretics, or exercising excessively.

In both cases, after they eat, they purge using activities such as vomiting, taking laxatives or diuretics, or exercising excessively.

Anorexia can be very damaging to the body. Over time, individuals living with it may experience thinning of their bones, infertility, and brittle hair and nails.

In severe cases, anorexia can result in heart, brain, or multi-organ failure and death.

Bulimia nervosa is another well-known eating disorder.

Like anorexia, bulimia tends to develop during adolescence and early adulthood and appears to be less common among men than women (10).

People with bulimia frequently eat unusually large amounts of food in a specific period of time.

Each binge eating episode usually continues until the person becomes painfully full. During a binge, the person usually feels that they cannot stop eating or control how much they are eating.

Binges can happen with any type of food but most commonly occur with foods the individual would usually avoid.

Individuals with bulimia then attempt to purge to compensate for the calories consumed and to relieve gut discomfort.

Common purging behaviors include forced vomiting, fasting, laxatives, diuretics, enemas, and excessive exercise.

Symptoms may appear very similar to those of the binge eating or purging subtypes of anorexia nervosa. However, individuals with bulimia usually maintain a relatively typical weight rather than losing a large amount of weight.

Common symptoms of bulimia nervosa include (1):

- recurrent episodes of binge eating with a feeling of lack of control

- recurrent episodes of inappropriate purging behaviors to prevent weight gain

- self-esteem overly influenced by body shape and weight

- a fear of gaining weight, despite having a typical weight

Side effects of bulimia may include an inflamed and sore throat, swollen salivary glands, worn tooth enamel, tooth decay, acid reflux, irritation of the gut, severe dehydration, and hormonal disturbances (11).

In severe cases, bulimia can also create an imbalance in levels of electrolytes, such as sodium, potassium, and calcium. This can cause a stroke or heart attack.

Binge eating disorder is the most prevalent form of eating disorder and one of the most common chronic illnesses among adolescents (12).

It typically begins during adolescence and early adulthood, although it can develop later on.

Individuals with this disorder have symptoms similar to those of bulimia or the binge eating subtype of anorexia.

For instance, they typically eat unusually large amounts of food in relatively short periods of time and feel a lack of control during binges.

People with binge eating disorder do not restrict calories or use purging behaviors, such as vomiting or excessive exercise, to compensate for their binges (12).

Common symptoms of binge eating disorder include (11):

- eating large amounts of food rapidly, in secret, and until uncomfortably full, despite not feeling hungry

- feeling a lack of control during episodes of binge eating

- feelings of distress, such as shame, disgust, or guilt, when thinking about the binge eating behavior

- no use of purging behaviors, such as calorie restriction, vomiting, excessive exercise, or laxative or diuretic use, to compensate for the binge eating

People with binge eating disorder often consume an excessive amount of food and may not make nutritious food choices. This may increase their risk of medical complications such as heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes (13).

This may increase their risk of medical complications such as heart disease, stroke, and type 2 diabetes (13).

Pica is an eating disorder that involves eating things that are not considered food and that do not provide nutritional value (14).

Individuals with pica crave non-food substances such as ice, dirt, soil, chalk, soap, paper, hair, cloth, wool, pebbles, laundry detergent, or cornstarch (11).

Pica can occur in adults, children, and adolescents.

It is most frequently seen in individuals with conditions that affect daily functioning, including intellectual disabilities, developmental conditions such as autism spectrum disorder, and mental health conditions such as schizophrenia (14).

Individuals with pica may be at an increased risk of poisoning, infections, gut injuries, and nutritional deficiencies. Depending on the substances ingested, pica may be fatal.

However, for the condition to be considered pica, the eating of non-food substances must not be a typical part of someone’s culture or religion. In addition, it must not be considered a socially acceptable practice by a person’s peers.

In addition, it must not be considered a socially acceptable practice by a person’s peers.

Rumination disorder is another newly recognized eating disorder.

It describes a condition in which a person regurgitates food they have previously chewed and swallowed, re-chews it, and then either re-swallows it or spits it out (15).

This rumination typically occurs within the first 30 minutes after a meal (16).

This disorder can develop during infancy, childhood, or adulthood. In infants, it tends to develop between 3 and 12 months of age and often disappears on its own. Children and adults with the condition usually require therapy to resolve it.

If not resolved in infants, rumination disorder can result in weight loss and severe malnutrition that can be fatal.

Adults with this disorder may restrict the amount of food they eat, especially in public. This may lead them to lose weight and become underweight (16).

Avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID) is a new name for an old disorder.

The term has replaced the term “feeding disorder of infancy and early childhood,” a diagnosis previously reserved for children under age 7 (17).

Individuals with this disorder experience disturbed eating due to either a lack of interest in eating or a distaste for certain smells, tastes, colors, textures, or temperatures.

Common symptoms of ARFID include (11):

- avoidance or restriction of food intake that prevents the person from eating enough calories or nutrients

- eating habits that interfere with typical social functions, such as eating with others

- weight loss or poor development for age and height

- nutrient deficiencies or dependence on supplements or tube feeding

It’s important to note that ARFID goes beyond common behaviors such as picky eating in toddlers or lower food intake in older adults.

Moreover, it does not include the avoidance or restriction of foods due to lack of availability or religious or cultural practices.

In addition to the six eating disorders above, other less known or less common eating disorders also exist.

These include (18):

- Purging disorder. Individuals with purging disorder often use purging behaviors, such as vomiting, laxatives, diuretics, or excessive exercising, to control their weight or shape. However, they do not binge.

- Night eating syndrome. Individuals with this syndrome frequently eat excessively at night, often after awakening from sleep.

- Other specified feeding or eating disorder (OSFED). While it is not found in the DSM-5, this category includes any other conditions that have symptoms similar to those of an eating disorder but don’t fit any of the disorders above.

One disorder that may currently fall under OSFED is orthorexia. Although orthorexia is increasingly mentioned in the media and in scientific studies, the DSM does not yet recognize it as a separate eating disorder (19).

Individuals with orthorexia tend to have an obsessive focus on healthy eating to an extent that disrupts their daily lives. They may compulsively check ingredient lists and nutritional labels and obsessively follow “healthy lifestyle” accounts on social media.

Someone with this condition may eliminate entire food groups, fearing that they’re unhealthy. This can lead to malnutrition, severe weight loss, difficulty eating outside the home, and emotional distress.

Individuals with orthorexia are rarely focused on losing weight. Instead, their self-worth, identity, or satisfaction is dependent on how well they comply with their self-imposed diet rules (19).

If you have an eating disorder, identifying the condition and seeking treatment sooner will improve your chances of recovering. Being aware of the warning signs and symptoms can help you decide whether you need to seek help.

Not everyone will have every sign or symptom at once, but certain behaviors may signal a problem, such as (20):

- behaviors and attitudes that indicate that weight loss, dieting, and control over food are becoming primary concerns

- preoccupation with weight, food, calories, fats, grams, and dieting

- refusal to eat certain foods

- discomfort with eating around others

- food rituals (not allowing foods to touch, eating only particular food groups)

- skipping meals or eating only small portions

- frequent dieting or fad diets

- extreme concern with body size, shape, and appearance

- frequently checking in the mirror for perceived flaws in appearance

- extreme mood swings

If these symptoms resonate with you and you think you may have an eating disorder, it’s important to reach out to a medical professional for help.

Making the decision to start eating disorder recovery might feel scary or overwhelming, but seeking help from medical professionals, eating disorder recovery support groups, and your community can make recovery easier.

If you’re not sure where to start, you can contact the National Eating Disorders Association helpline for support, resources, and treatment options for yourself or someone you know.

To contact, call: (800) 931-2237

Monday–Thursday 11 a.m.–9 p.m. ET

Friday 11 a.m.–5 p.m. ET

Text: (800) 931-2237

Monday–Thursday 3 p.m.–6 p.m. ET

Friday 1 p.m.–5 p.m. ET

Eating disorder treatment plans are specifically tailored to each person and may include a combination of multiple therapies.

Treatment will usually involve talk therapy, as well as regular health checks with a physician (21).

It’s important to seek treatment early for eating disorders, as the risk of medical complications and suicide is high (11).

Treatment options include:

- Individual, group, or family psychotherapy. A type of psychotherapy called cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) may be recommended to help reduce or eliminate disordered behavior such as binge eating, purging, and restricting. CBT involves learning how to recognize and change distorted or unhelpful thought patterns (11).

- Medications. A doctor may recommend treatment with medications such as antidepressants, antipsychotics, or mood stabilizers to help treat an eating disorder or other conditions that may occur at the same time, such as depression or anxiety (11).

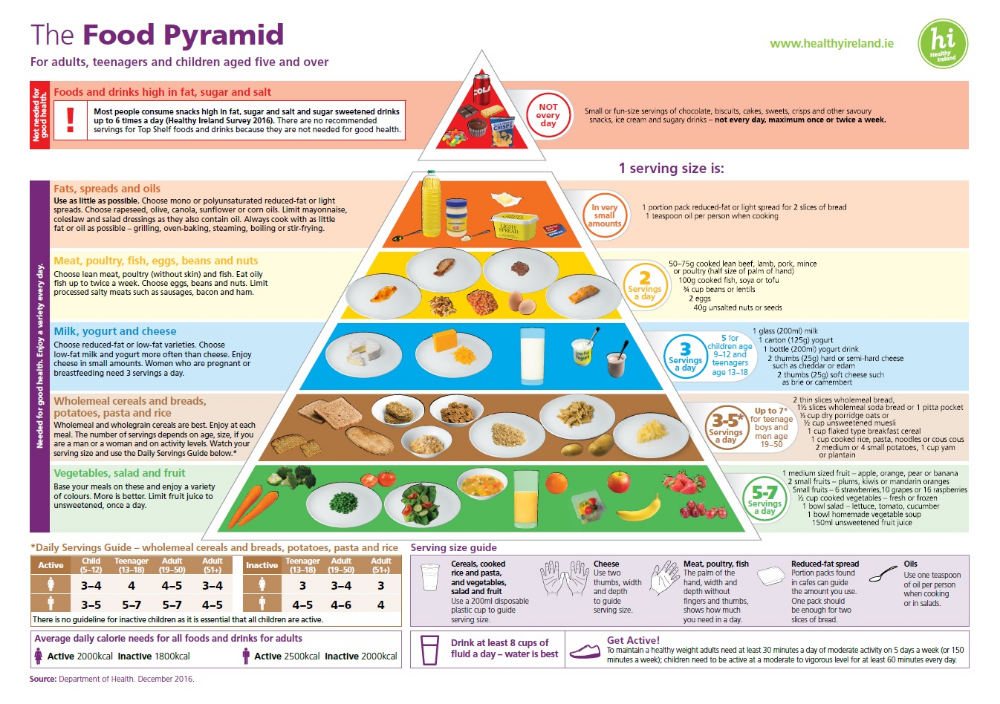

- Nutritional counseling. This involves working with a dietitian to learn proper nutrition and eating habits and may also involve restoring or managing a person’s weight if they have experienced significant weight changes. Studies suggest that combining nutritional therapy with cognitive therapy may significantly improve treatment outcomes (22).

If you think someone in your life has an eating disorder, your best bet is to support and encourage them to seek help from a healthcare professional.

This can be extremely difficult for someone living with an eating disorder, but supporting them in other ways will help them feel cared for and encouraged in their recovery.

Recovering from an eating disorder can take a long time, and this person may have periods of relapsing into old behaviors, especially during times of stress. If you’re close to this person, it’s important to be there for them, and be patient, throughout their recovery (21).

Ways to support someone with an eating disorder include (21):

- Listening to them. Taking time to listen to their thoughts can help them feel heard, respected, and supported. Even if you don’t agree with what they say, it’s important that they know you’re there for them and that they have someone to confide in.

- Including them in activities.

You can reach out and invite them to activities and social events or ask if they want to hang out one-on-one. Even if they do not want to be social, it’s important to check in and invite them to help them feel valued and less alone.

You can reach out and invite them to activities and social events or ask if they want to hang out one-on-one. Even if they do not want to be social, it’s important to check in and invite them to help them feel valued and less alone. - Trying to build their self-esteem. Make sure they know that they are valued and appreciated, especially for nonphysical reasons. Remind them why you are their friend and why they are valued.

The categories above are meant to provide a better understanding of the most common eating disorders and dispel myths about them.

Eating disorders are mental health conditions that usually require treatment. They can also be damaging to the body if left untreated.

If you have an eating disorder or know someone who might have one, you can seek help from a healthcare professional who specializes in eating disorders.

You can book an appointment with an eating disorder specialist in your area using our Healthline FindCare tool.

Read this article in Spanish.

Eating disorders | Tervisliku toitumise informatsioon

Eating disorders are psychiatric illnesses that damage a person's physical and mental health and impair their overall quality of life - relationships, work and personal development suffer.

Eating disorders disrupt the connection with one's own body, resulting in highly problematic eating behavior. Weight and body shape are overemphasized, underweight is idealized, and various methods are used to lose weight or prevent weight gain. nine0003

Approximately 8% of women and 2% of men will develop an eating disorder during their lifetime. Eating disorders occur in any population, regardless of gender, age, ethnicity, or socioeconomic status. However, they are most common in girls and young women.

Eating disorders are a group of diseases that are distributed differently in different classifications. The most common eating disorders are anorexia ( anorexia nervosa ), bulimia ( bulimia nervosa ) and compulsive overeating ( binge-eating disorder ).

The term "eating disorder" is often erroneously used as a synonym for selective eating disorder, as both are associated with eating disorders. However, the reasons for them are different: an eating disorder is caused by a desire to control weight, while in a selective eating disorder, eating certain foods causes anxiety or fear. nine0003

Other eating disorders

Anorexia, bulimia and binge eating disorders are the three most common and well-known eating disorders. However, often not all of the symptoms of a person with an eating disorder correspond to one specific disorder. In such cases, these disorders are referred to as "atypical" or "other eating disorders". A common myth is that in such cases the course of the disease is milder and treatment is treated more lightly. However, this is erroneous, since the name of the disease indicates only its diagnostic criteria, and not the severity or course. nine0003

All eating disorders, no matter how they are called or classified, are dangerous conditions that impair quality of life and require treatment.

Causes of Eating Disorders

There is never one single cause of an eating disorder. These are complex diseases, in the development of which a combination of many factors plays an important role. Genetic, biological and environmental factors always play a role. Modern social representations, including the culture of diets and the cult of slimness, contribute to the development of psychological vulnerability, which can become a fertile environment for the formation of eating disorders. Probably for the same reasons, a higher incidence of eating disorders is observed in sports in which weight is of great importance, and among representatives of professions focused on appearance. However, it should be emphasized that browsing social networks or playing a certain sport does not contribute to the development of the disease. There are many factors involved in the development of the disease that are usually beyond the control of the individual. However, it is often more practical and even more important to identify the factors that support the disease, since changing them is associated with better treatment outcomes. nine0003

nine0003

Treatment Options for Eating Disorders

Eating disorders can be life-threatening illnesses with a long and chronic course; they have one of the highest mortality rates of any psychiatric illness. Treating eating disorders is often a lengthy and complex process. However, early intervention is paramount to achieve a good treatment outcome.

Diagnosis and treatment of an eating disorder usually begins with the family physician. Family sisters can provide advice on healthy eating. Psychiatrists are specialists in the diagnosis and treatment of eating disorders as a psychiatric illness. The participation of a clinical psychologist or psychotherapist is also important. nine0003

There are two centers in Estonia that specialize in the treatment of eating disorders: the Department of Eating Disorders of the Mental Health Center of the Tallinn Children's Hospital treats children and adolescents, and the Department of Eating Disorders of the Psychiatric Clinic of the Tartu University Hospital treats adolescents and adults.

For more information about eating disorders and advice on what to do if you suspect a loved one has an eating disorder, visit peaasi.ee. nine0003

Bulimia | Tervisliku toitumise informatsioon

Bulimia ( bulimia nervosa ) is an eating disorder characterized by recurrent bouts of overeating, excessive anxiety about one's weight and extreme weight control measures.

During bouts of overeating, a large amount of food is eaten, which is subsequently compensated by various types of unhealthy behavior: deliberate vomiting, abuse of laxatives or appetite suppressants, excessive physical exertion, periodic periods of fasting. A person's thoughts revolve around food and eating, a lot of attention is paid to weight and how to control it, the desire to lose weight, the fear of gaining it. The disease is characterized by a vicious cycle in which binge eating is followed by feelings of guilt and regret, leading to compensatory behavior and temporary fasting, which in turn increases the likelihood of recurring binge eating episodes. The most common age of onset is adolescence and early adulthood. The prevalence of bulimia is 1-4% of the population. nine0003

The most common age of onset is adolescence and early adulthood. The prevalence of bulimia is 1-4% of the population. nine0003

Symptoms of bulimia:

- overweight, fear of gaining weight, desire to lose weight sweets, fast food), often hides food intake from others, feels a loss of control

- overeating causes shame and guilt

- compensation for the weight gain effect of food eaten: deliberate induction of vomiting, abuse of laxatives, excessive exercise

- patients are normal or overweight, weight fluctuates greatly

Complications of bulimia:

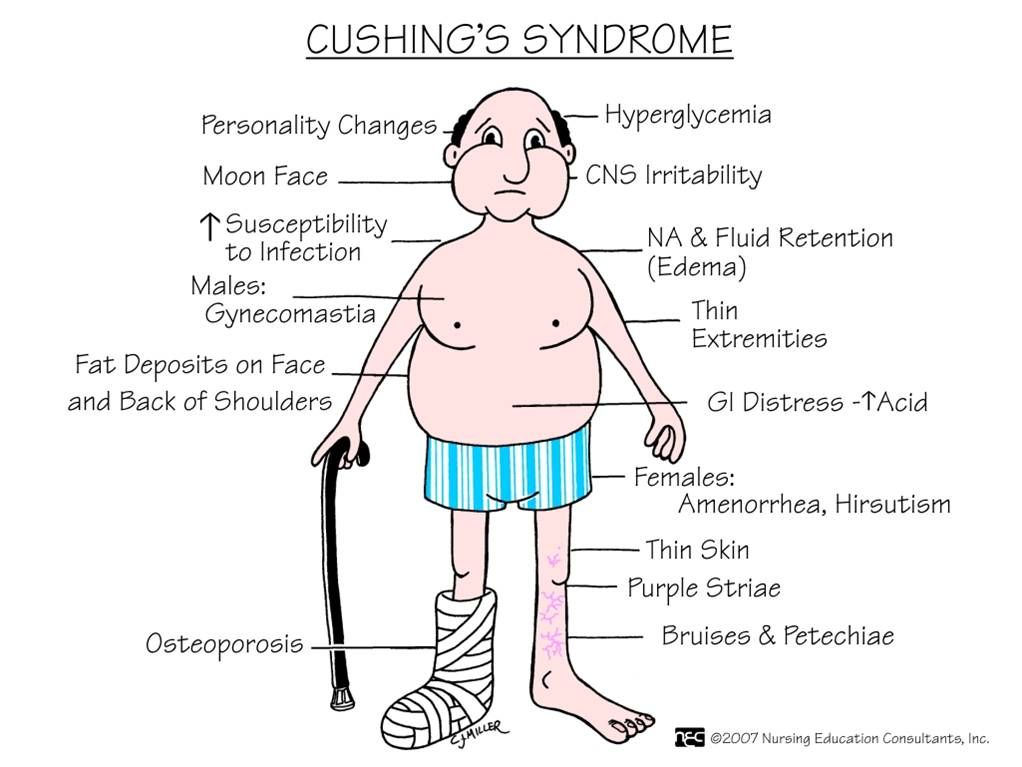

- intentional vomiting causes burns of gastric juice that damages teeth, throat, esophagus

- frequent vomiting causes enlargement of salivary glands, cracks in the corners of the mouth, thickening skin on the knuckles.

- weakening of the esophageal sphincter

- vomiting and laxative abuse lead to loss of electrolytes, electrolyte disturbances can lead to muscle weakness, convulsions, arrhythmias

Bulimia Treatment Options

Bulimia treatment is usually started on an outpatient basis, but more severe cases may require inpatient treatment.