Alcohol induced sleep disorder

Alcohol and Sleep | Sleep Foundation

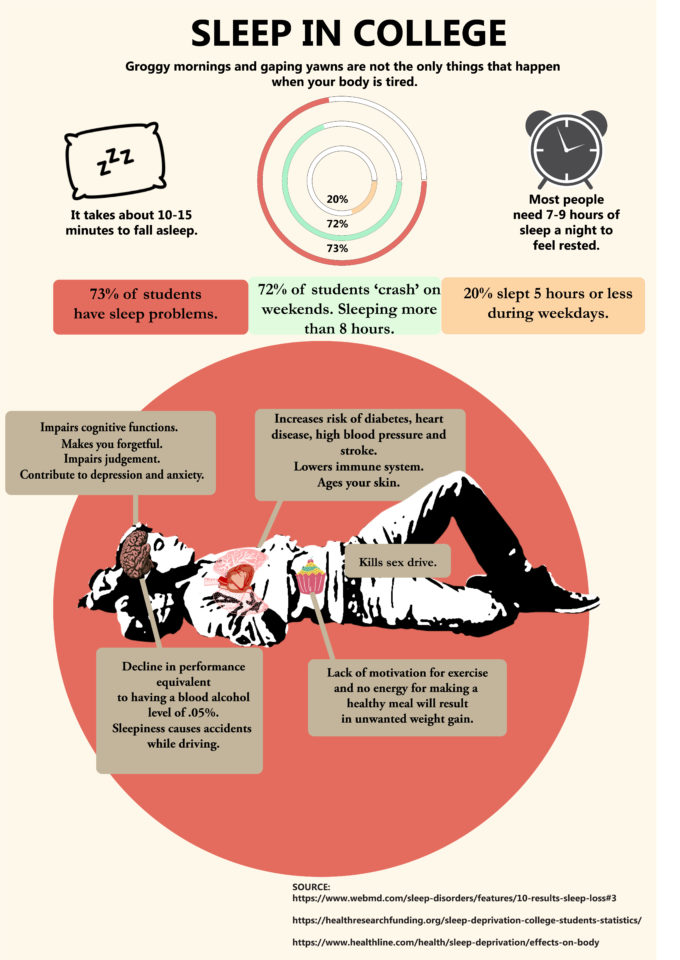

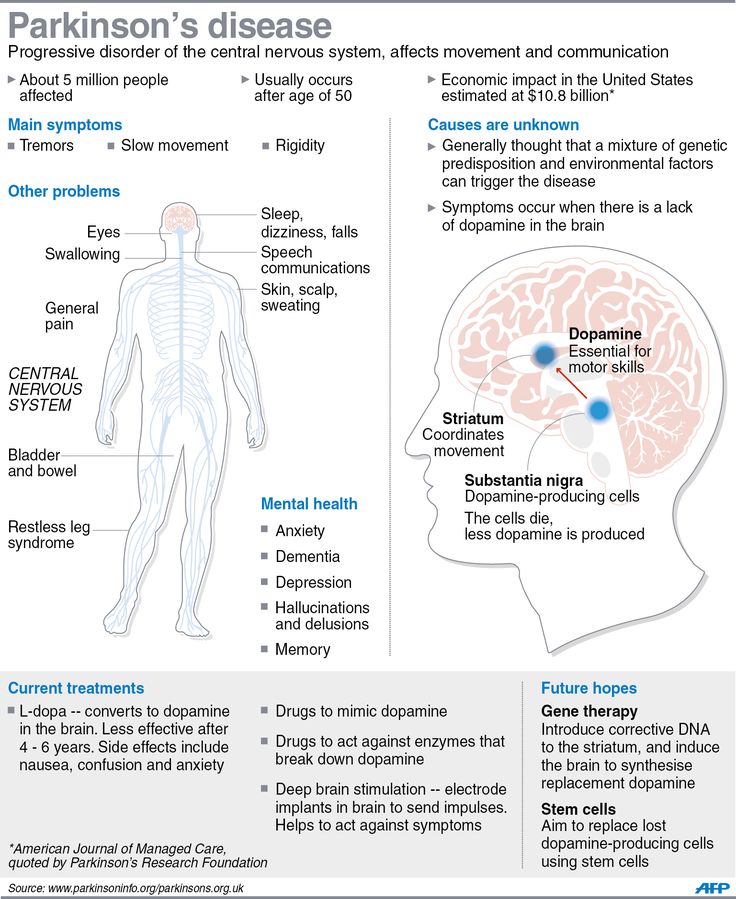

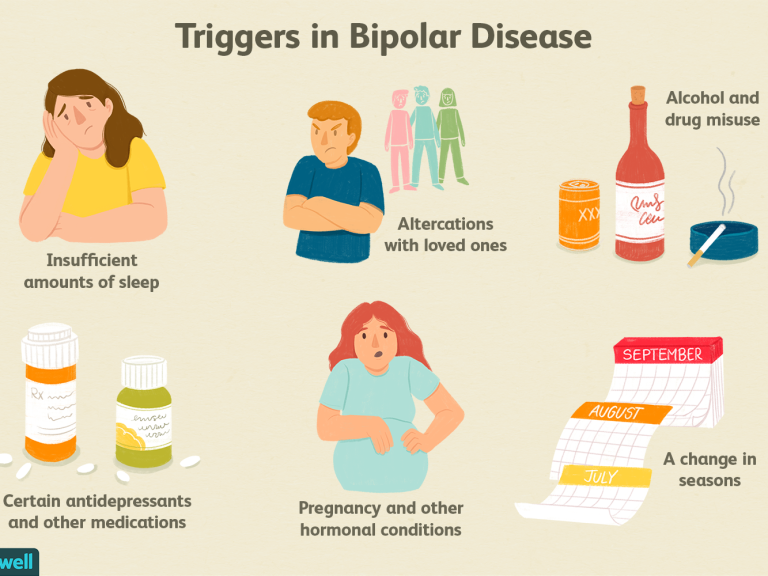

Alcohol is a central nervous system depressant that causes brain activity to slow down. Alcohol has sedative effects that can induce feelings of relaxation and sleepiness, but the consumption of alcohol – especially in excess – has been linked to poor sleep quality and duration. People with alcohol use disorders commonly experience insomnia symptoms. Studies have shown that alcohol use can exacerbate the symptoms of sleep apnea.

Drinking in moderation is generally considered safe but every individual reacts differently to alcohol. As a result, alcohol’s impact on sleep largely depends on the individual.

How Does Alcohol Affect Sleep?

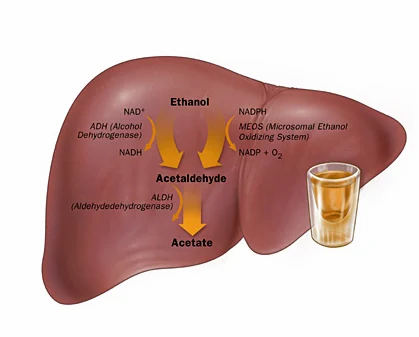

After a person consumes alcohol, the substance is absorbed into their bloodstream from the stomach and small intestine. Enzymes in the liver eventually metabolize the alcohol, but because this is a fairly slow process, excess alcohol will continue to circulate throughout the body.

The effects of alcohol largely depend on the consumer. Important factors include the amount of alcohol and how quickly it is consumed, as well as the person’s age, sex, body type, and physical shape.

The relationship between alcohol and sleep has been studied since the 1930s, yet many aspects of this relationship are still unknown. Research has shown sleepers who drink large amounts of alcohol before going to bed are often prone to delayed sleep onset, meaning they need more time to fall asleep. As liver enzymes metabolize the alcohol during their night and the blood alcohol level decreases, these individuals are also more likely to experience sleep disruptions and decreases in sleep quality.

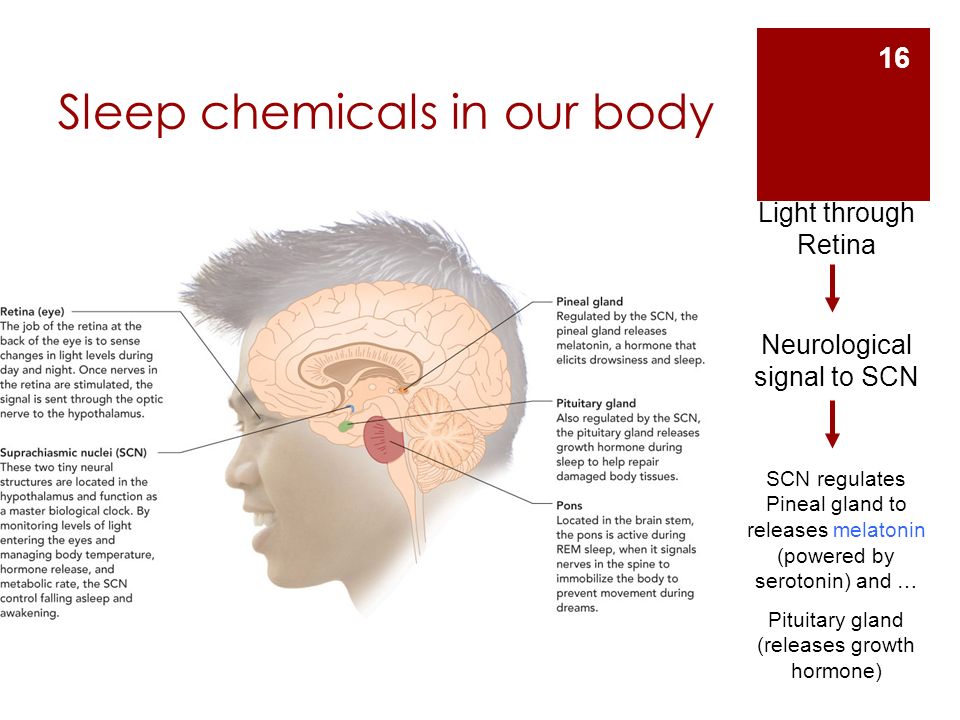

To understand how alcohol impacts sleep, it’s important to discuss different stages of the human sleep cycle. A normal sleep cycle consists of four different stages: three non-rapid eye movement (NREM) stages and one rapid eye movement (REM) stage.

- Stage 1 (NREM): This initial stage is essentially the transition period between wakefulness and sleep, during which the body will begin to shut down.

The sleeper’s heart beat, breathing, and eye movements start to slow down and their muscles will relax. Brain activity also begins to decrease, as well. This phase is also known as light sleep.

The sleeper’s heart beat, breathing, and eye movements start to slow down and their muscles will relax. Brain activity also begins to decrease, as well. This phase is also known as light sleep. - Stage 2 (NREM): The sleeper’s heartbeat and breathing rates continue to slow down as they progress toward deeper sleep. Their body temperature will also decrease and the eyes become still. Stage 2 is usually the longest of the four sleep cycle stages.

- Stages 3 (NREM): Heartbeat, breathing rates, and brain activity all reach their lowest levels of the sleep cycle. Eye movements cease and the muscles are totally relaxed. This stage is known as slow-wave sleep.

- REM: REM sleep kicks in about 90 minutes after the individual initially falls asleep. Eye movements will restart and the sleeper’s breathing rate and heartbeat will quicken. Dreaming mostly takes place during REM sleep. This stage is also thought to play a role in memory consolidation.

These four NREM and REM stages repeat in cyclical fashion throughout the night. Each cycle should last roughly 90-120 minutes, resulting in four to five cycles for every eight hours of sleep. For the first one or two cycles, NREM slow-wave sleep is dominant, whereas REM sleep typically lasts no longer than 10 minutes. For later cycles, these roles will flip and REM will become more dominant, sometimes lasting 40 minutes or longer without interruption; NREM sleep will essentially cease during these cycles.

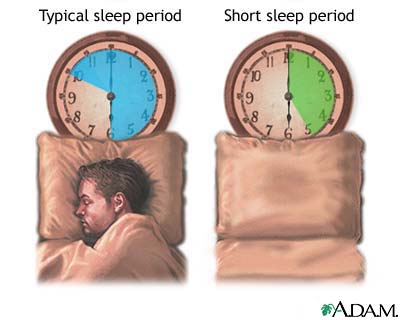

Drinking alcohol before bed can add to the suppression of REM sleep during the first two cycles. Since alcohol is a sedative, sleep onset is often shorter for drinkers and some fall into deep sleep rather quickly. As the night progresses, this can create an imbalance between slow-wave sleep and REM sleep, resulting in less of the latter and more of the former. This decreases overall sleep quality, which can result in shorter sleep duration and more sleep disruptions.

The Matt Walker Podcast

SleepFoundation.org's Scientific Advisor

Sleep & Alcohol

Listen on BuzzsproutAlcohol and Insomnia

Insomnia, the most common sleep disorder, is defined as “a persistent difficulty with sleep initiation, duration, consolidation, or quality.” Insomnia occurs despite the opportunity and desire to sleep, and leads to excessive daytime sleepiness and other negative effects.

Since alcohol can reduce REM sleep and cause sleep disruptions, people who drink before bed often experience insomnia symptoms and feel excessively sleepy the following day. This can lead them into a vicious cycle that consists of self-medicating with alcohol in order to fall asleep, consuming caffeine and other stimulants during the day to stay awake, and then using alcohol as a sedative to offset the effects of these stimulants.

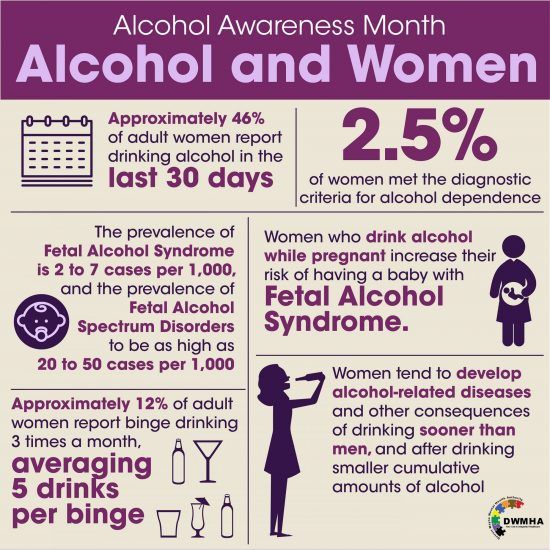

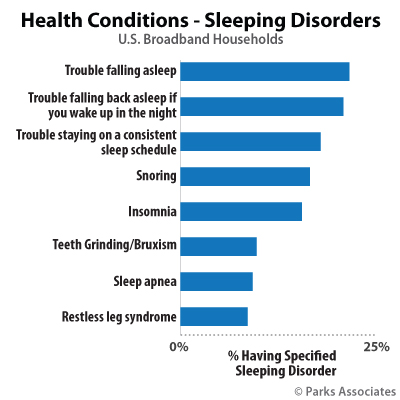

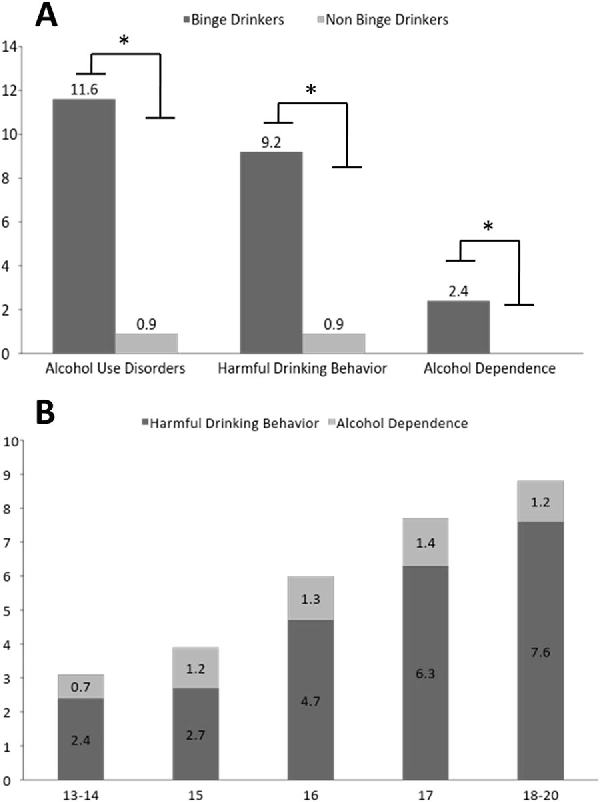

Binge-drinking – consuming an excessive amount of alcohol in a short period of time that results in a blood alcohol level of 0. 08% or higher – can be particularly detrimental to sleep quality. In recent studies, people who took part in binge-drinking on a weekly basis were significantly more likely to have trouble falling and staying asleep. These findings were true for both men and women. Similar trends were observed in adolescents and young adults, as well as middle-aged and older adults.

08% or higher – can be particularly detrimental to sleep quality. In recent studies, people who took part in binge-drinking on a weekly basis were significantly more likely to have trouble falling and staying asleep. These findings were true for both men and women. Similar trends were observed in adolescents and young adults, as well as middle-aged and older adults.

Researchers have noted a link between long-term alcohol abuse and chronic sleep problems. People can develop a tolerance for alcohol rather quickly, leading them to drink more before bed in order to initiate sleep. Those who have been diagnosed with alcohol use disorders frequently report insomnia symptoms.

Alcohol and Sleep Apnea

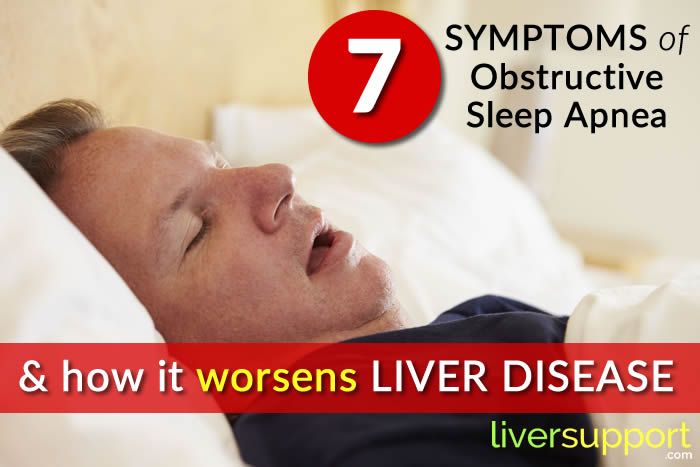

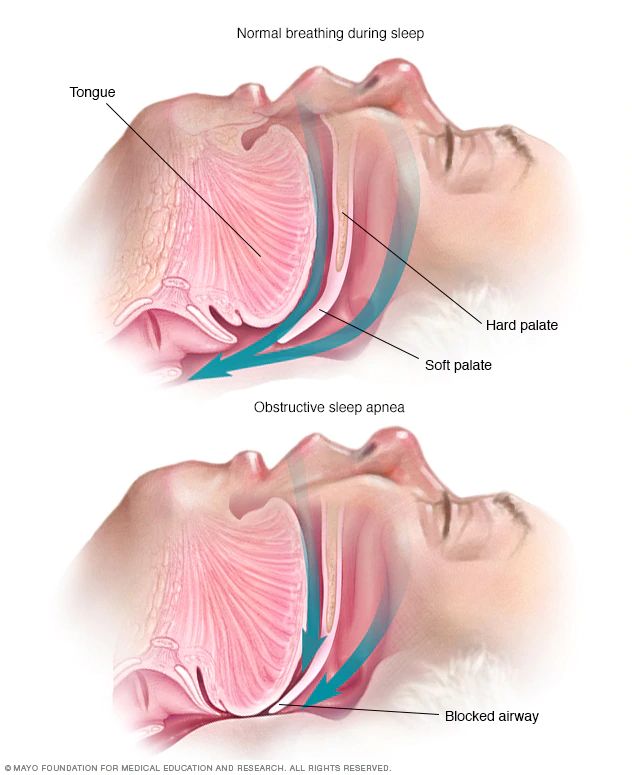

Sleep apnea is a disorder characterized by abnormal breathing and temporary loss of breath during sleep. These lapses in breathing can in turn cause sleep disruptions and decrease sleep quality. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) occurs due to physical blockages in the back of the throat, while central sleep apnea (CSA) occurs because the brain cannot properly signal the muscles that control breathing.

During apnea-related breathing episodes – which can occur throughout the night – the sleeper may make choking noises. People with sleep apnea are also prone to loud, disruptive snoring. Some studies have suggested that alcohol contributes to sleep apnea because it causes the throat muscles to relax, which in turn creates more resistance during breathing. This can exacerbate OSA symptoms and lead to disruptive breathing episodes, as well as heavier snoring. Additionally, consuming just one serving of alcohol before bed can lead to OSA and heavy snoring even for people who have not been diagnosed with sleep apnea.

The relationship between sleep apnea and alcohol has been researched somewhat extensively. The general consensus based on various studies is that consuming alcohol increases the risk of sleep apnea by 25%.

Alcohol and Sleep FAQ

Does Alcohol Help You Sleep?

Alcohol may aid with sleep onset due to its sedative properties, allowing you to fall asleep more quickly. However, people who drink before bed often experience disruptions later in their sleep cycle as liver enzymes metabolize alcohol. This can also lead to excessive daytime sleepiness and other issues the following day. Furthermore, drinking to fall asleep can build a tolerance, forcing you to consume more alcohol each successive night in order to experience the sedative effects.

However, people who drink before bed often experience disruptions later in their sleep cycle as liver enzymes metabolize alcohol. This can also lead to excessive daytime sleepiness and other issues the following day. Furthermore, drinking to fall asleep can build a tolerance, forcing you to consume more alcohol each successive night in order to experience the sedative effects.

Does Alcohol Affect Men and Women Differently?

On average, women exhibit signs of intoxication earlier and with lower doses of alcohol than men. This can mostly be attributed to two factors. First, women tend to weigh less than men and those with lower body weights often become intoxicated more quickly. Most women also have a lower amount of water in their bodies than men. Alcohol circulates through water in the body, so women are more likely to have higher blood alcohol concentrations than men after consuming the same amount of alcohol.

What Is the Difference Between Moderate Drinking and Heavy Drinking?

Definitions vary by source, but the following measurements are generally considered to constitute a single serving of alcohol:

- 12 ounces of beer with 5% alcohol content

- 5 ounces of wine with 12% alcohol content

- 1 ounce of liquor or distilled spirits with 40% alcohol content

Moderate drinking is loosely defined as up to two drinks per day for men and one drink per day for women. Heavy drinking means more than 15 drinks per week for men and more than eight drinks per week for women.

Heavy drinking means more than 15 drinks per week for men and more than eight drinks per week for women.

Will a Small Amount of Alcohol Affect My Sleep?

Drinking to excess will probably have a more negative impact on sleep than light or moderate alcohol consumption. However, since the effects of alcohol are different from person to person, even small amounts of alcohol can reduce sleep quality for some people.

One 2018 study compared sleep quality among subjects who consumed different amounts of alcohol. The findings are as follows:

- Low amounts of alcohol (fewer than two servings per day for men or one serving per day for women) decreased sleep quality by 9.3%.

- Moderate amounts of alcohol (two servings per day for men or one serving per day for women) decreased sleep quality by 24%.

- High amounts of alcohol (more than two servings per day for men or one serving per day for women) decreased sleep quality by 39.

2%.

2%.

When Should I Stop Drinking Prior To Bed To Minimize Sleep Disruption?

To reduce the risk of sleep disruptions, you should stop drinking alcohol at least four hours before bedtime.

- Was this article helpful?

- YesNo

References

+15 Sources

-

1.

A.D.A.M. Medical Encyclopedia. (2014, June 12). Alcohol. Retrieved August 25, 2020, from https://medlineplus.gov/alcohol.html

-

2.

Park, S., Oh, M., Lee, B., Kim, H., Lee, W., Lee, J., Lim, J., & Kim, J. (2015). The Effects of Alcohol on Quality of Sleep. Korean Journal of Family Medicine, 36(6), 294–299. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4666864/

-

3.

Centers for Disease Control. (2020, January 15). Alcohol and Public Health: Frequently Asked Questions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/faqs.

htm

htm -

4.

Roehrs, T., & Roth, T. Sleep, Sleepiness, and Alcohol Use. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Retrieved from https://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/arh35-2/101-109.htm

-

5.

Rasch, B., & Born, J. (2013). About Sleep’s Role in Memory. Physiological Reviews, 93(2), 681–766. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3768102/

-

6.

Schwab, R. (2020, June). Insomnia and Excessive Daytime Sleepiness (EDS). Merck Manual Consumer Version. Retrieved August 24, 2020 from https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/brain,-spinal-cord,-and-nerve-disorders/sleep-disorders/overview-of-sleep

-

7.

American Academy of Sleep Medicine. (2014). The International Classification of Sleep Disorders – Third Edition (ICSD-3). Darien, IL.

-

8.

Coltrain, I., Nicholas, C., & Baker, F. (2018). Alcohol and the Sleeping Brain. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 125, 415–431.

Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5821259/

Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5821259/ -

9.

Popovici, I., & French, M. (2013). Binge Drinking and Sleep Problems among Young Adults. Drug and Alcohol Independence, 132, 207–215. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3748176/

-

10.

Canham, S., Kaufmann, C., Mauro, P., Mojtabai, R., & Spira, A. (2015). Binge Drinking and Insomnia in Middle-aged and Older Adults: The Health and Retirement Study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 30(3), 284–291. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4221579/

-

11.

Simou, E., Britton, J., & Leonardi-Bee, J. (2018). Alcohol and the risk of sleep apnoea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Medicine, 42, 38–46. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5840512/

-

12.

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. (2019, December). Women and Alcohol.

Retrieved from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/women-and-alcohol

Retrieved from https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/brochures-and-fact-sheets/women-and-alcohol -

13.

Pietilä, J., Helander, E., Korhonen, I., Myllymäki, T., Kujala, U., & Lindholm, H. (2018). Acute Effect of Alcohol Intake on Cardiovascular Autonomic Regulation During the First Hours of Sleep in a Large Real-World Sample of Finnish Employees: Observational Study. JMIR Mental Health, 5(1), e23. Retrieved from https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29549064/

-

14.

Sleep Health Foundation. (2013). Caffeine, Food, Alcohol, Smoking and Sleep. Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2775419/

-

15.

Stein, M. D., & Friedmann, P. D. (2005). Disturbed sleep and its relationship to alcohol use. Substance abuse, 26(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1300/j465v26n01_01

See More

Disturbed Sleep and Its Relationship to Alcohol Use

1. Katz DA, McHorney CA. Clinical correlates of insomnia in patients with chronic illness. Arch Int Med. 1998;58:1099–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch Int Med. 1998;58:1099–1107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Kuppermann M, Lubeck D, Mazonson P, et al. Sleep problems and their correlates in a working population. J Gen Int Med. 1995;10:25–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Wiley J, Camacho T. Life-style and future health: Evidence from the Alameda County Study. Prev Med. 1980;9:1–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

4. Kupfer D. Management of insomnia. NEJM. 1997;336:341–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Klink M, Quan S, Kaltenborn W, Lebowitz M. Risk factors associated with complaints of insomnia in a general adult population. Arch Int Med. 1992;152:1634–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. Ford DE, Kamerow DB. Epidemiologic study of sleep disturbances and psychiatric disorders. JAMA. 1989;262(11):1479–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Dufour MC, Archer L, Gordis E. Alcohol and the elderly. Clin Ger Med. 1992;8:127–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Schuckit MA, Irwin M. Diagnosis of alcoholism. Med Clin N Am. 1988;72:1133–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1988;72:1133–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. Castenada R, Sussman N, Westrich L. A review of the effects of moderate alcohol intake on the treatment of anxiety and mood disorders. Clin Psych. 1996;57:207–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Reite M, Buysse D, Reynolds C, Mendelson W. The use of polysomnography in the evaluation of insomnia. Sleep. 1995;18:58–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Roehrs T, Papineau K, Rosenthal L, Roth T. Ethanol as a hypnotic in insomniacs: Self administration and effects on sleep and mood. Neuropsychopharm. 1999;20:279–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Gresham SC, Webb WB, Williams RC. Alcohol and caffeine: Effect on inferred visual dreaming. Science. 1963;140:1226–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Prinz P, Roehrs T, Vitaliano P, Linnoila M, Weitzman E. Effect of alcohol on sleep and nighttime plasma growth hormone and cortisol concentrations. J Clin Endoc Metab. 1980;1:759–64. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

14. Petrucelli N, Roehrs TA, Wittig RM, Roth T. The biphasic effects of ethanol on sleep latency. Sleep Research. 1994;23:75. [Google Scholar]

The biphasic effects of ethanol on sleep latency. Sleep Research. 1994;23:75. [Google Scholar]

15. Roehrs T, Zwyghuizen-Doorenbos A, Timms V, Zorick F, Roth T. Sleep extension, enhanced alertness and the sedating effects of ethanol. Pharm Biochem Behav. 1989;34:321–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

16. Zwyghuizen-Doorenbos A, Roehrs T, Lamphere J, Zorick F, Roth T. Increased daytime sleepiness enhances ethanol’s sedative effects. Neuropsychopharm. 1988;1:279–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Maclean AW, Cairns J. Dose-response effects of ethanol on the sleep of young men. J Stud Alc. 1982;43:434–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Landolt HP, Roth C, Dijk DJ, Borberly AA. Late-afternoon ethanol intake affects nocturnal sleep and the sleep EEG in middle-aged men. J Clin Psychopharm. 1996;16:428–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. Roehrs T, Claiborue D, Knox M, Roth T. Residual sedating effects of ethanol. Alc Clin Exp Res. 1994;18:831–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Rundell OH, Lester BK, Griffiths WJ, Williams HL. Alcohol and sleep in young adults. Psychopharm. 1972;26:201–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Rundell OH, Lester BK, Griffiths WJ, Williams HL. Alcohol and sleep in young adults. Psychopharm. 1972;26:201–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Ancoli-Israel S, Roth T. Characteristics of insomnia in the United States: Results of the 1991 National Sleep Foundation Survey. Sleep. 1999;22(Suppl 2):S347–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Johnson EO, Roehrs T, Roth T, Breslau N. Epidemiology of alcohol and medication as aids to sleep in early adulthood. Sleep. 1998;21(2):178–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Costa E, Silva JA, Chase M, Sartorius N, Roth T. Special report from a symposium held by the World Health Organization and the World Federation of Sleep Research Societies: An overview of insomnias and related disorders–recognition, epidemiology, and rational management. Sleep. 1996;19:412–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Walsh JK, Humm T, Muehlback MJ, Sugerman JL, Schweitzer PK. Sedative effects of ethanol at night. J Stud Alc. 1991;52:597–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Philip P, Guilleminault C, Priest RG. How sleep and mental disorders are related to complaints of daytime sleepiness. Arch Int Med. 1997;157:2645–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ohayon MM, Caulet M, Philip P, Guilleminault C, Priest RG. How sleep and mental disorders are related to complaints of daytime sleepiness. Arch Int Med. 1997;157:2645–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Aldrich MS. Automobile accidents in patients with sleep disorders. Sleep. 1989;12:487–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Johnson JE. Insomnia, alcohol, and over-the-counter drug use in old-old urban women. J Comm Health Nursing. 1997;14:181–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Baum-Baicker C. The psychological benefits of moderate alcohol consumption: A review of the literature. Drug Alc Depend. 1985;15:305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Bixler EO, Kales A, Soldatos CR, Kales JD, Healey S. Prevalence of sleep disorders in the Los Angeles Metropolitan Area. Am J Psych. 1979;136(1):1257–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Carskadon M, Demendt W, Mitler M, Guilleminault C, Zarcone V, Spiegel R. Self-report versus sleep laboratory findings in 122 drug-free subjects with complaints of chronic insomnia. Am J Psych. 1976;133:1382–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psych. 1976;133:1382–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Baekeland F, Hoy P. Reported vs. recorded sleep characteristics. Arch Gen Psych. 1971;24:548–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Janson C, Lindberg E, Gislason T, Elmasry A, Boman G. Insomnia in men–A 10 year prospective population based study. Sleep. 2001;24(4):425–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Tachibana H, Izumi T, Honda S, Horiguchi I, Manabe E, Takemoto T. A study of the impact of occupational and domestic factors on insomnia among industrial workers of a manufacturing company in Japan. Occup Med. 1996;46(3):221–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Harma M, Tenkanen L, Sjoblom T, Alikoski T, Heinsalmi P. Combined effects of shift work and lifestyle on the prevalence of insomnia, sleep deprivation and daytime sleepiness. Scand J Work Environ Health. 1998;24(4):300–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Fabsitz RR, Sholinsky P, Goldberg J. Correlates of sleep problems among men: The Vietnam Era Twins Registry. J Sleep Res. 1997;6:50–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Sleep Res. 1997;6:50–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Baekeland F, Lundwall L, Shanahan TJ, Kissin B. Clinical correlates of reported sleep disturbance in alcoholics. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1974;35:1230–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Feuerlein W. The acute alcohol withdrawal syndrome: findings and problems. Br J Addict. 1974;69:141–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Caetano R, Clark RL, Greenfield TK. Prevalence, trends, and incidence of alcohol withdrawal symptoms: Analysis of general population and clinical samples. Alc Health Res World. 1998;22:73–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Foster JH, Marshall EJ, Peters TJ. Predictors of relapse to heavy drinking in alcohol dependent subjects following alcohol detoxification–The role of quality of life measures, ethnicity, social class, cigarettes and drug use. Addict Biol. 1998;3:333–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Mello NK, Mendelson JH. Behavioral studies of sleep patterns in alcoholics during intoxication and withdrawal. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1970;175(1):94–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1970;175(1):94–112. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Brower KJ, Aldrich MS, Robinson EAR, Zucker RA, Greden JF. Insomnia, self-medication, and relapse to alcoholism. Am J Psych. 2001;1568:399–404. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Allen RP, Wagman AM, Funderburk FR, Wells DT. Slow wave sleep: A predictor of individual differences in response to drinking? . Biol Psych. 1980;15:345–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Gillin JC, Smith TL, Irwin M, Kripke DF, Schuckit M. EEG sleep studies in “pure” primary alcoholism during subacute withdrawal: Relationships to normal controls, age and other clinical variables. Biol Psych. 1990;27:477–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Thompson PM, Gillin JC, Golshan S, Irwin M. Polygraphic sleep measures differentiate alcoholics and stimulant abusers during short-term abstinence. Biol Psych. 1995;38:831–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Johnson LC, Burdick JA, Smith J. Sleep during alcohol intake and withdrawal in the chronic alcoholic. Arch Gen Psych. 1970;22:406–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch Gen Psych. 1970;22:406–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Segal BM, Kushnarev VM, Urakov IG, Misionzhnik EU. Alcoholism and disruption of the activity of deep cerebral structures: Clinical-laboratory research. Q J Stud Alcohol. 1970;31:587–601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Begleiter H, Porjesz B. Persistence of a “subacute withdrawal syndrome” following chronic ethanol intake. Drug Alc Depend. 1979;4:353–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

48. Wellman M. The late withdrawal symptoms of alcoholic addiction. Can Med Assoc J. 1954;70:526–59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Kissin B. Biological investigation in alcoholics. J Stud Alcohol. 1979;8:S146–81. [Google Scholar]

50. Drummond SPA, Gillin JC, Smith TL, DeModena A. The sleep of abstinent pure primary alcoholic patients: Natural course and relationship to relapse. Alc Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1796–1802. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Williams HL, Rundell OH. Altered sleep physiology in chronic alcoholics; reversal with abstinence. Alc Clin Exp Res. 1981;2:318–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Alc Clin Exp Res. 1981;2:318–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Mackenzie A, Funderburk FR, Allen RP. Controlled drinking and abstinence in alcoholic men: Beliefs influence actions. Int J Addict. 1994;29:1377–92. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Gillin JC, Smith TL, Irwin M, Butters N, DeModena A, Schukit M. Increased pressure of rapid eye movement sleep at time of hospital admission predicts relapse in non-depressed patients with primary alcoholism at 3-month follow-up. Arch Gen Psych. 1994;51:189–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Clark C, Gillin J, Golshan S, et al. Increased REM sleep density at admission predicts relapse by three months in primary alcoholics with a lifetime diagnosis of secondary depression. Biol Psych. 1998;43:601–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

55. Brower K, Aldrich M, Hall J. Polysomnographic and subjective sleep predictors of alcoholic relapse. Alc Clin Exp Res. 1998;22:1864–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Allen RP, Wagman AMI, Fund ER, Burke FR. Slow wave sleep changes: Alcohol tolerance and treatment implications. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1977;85:629–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Slow wave sleep changes: Alcohol tolerance and treatment implications. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1977;85:629–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

57. Block AJ, Hellard DW, Slayton PC. Effect of alcohol ingestion on breathing of asymptomatic subjects. Arch Intern Med. 1987;147:1145–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

58. Robinson RW, White DP, Zwillich CW. Moderate alcohol ingestion increases upper airway resistance in normal subjects. Am Rev Resp Dis. 1985;132:1238–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

59. Dawson A, Lehr P, Bigby BG, Mitler MM. Effect of bedtime ethanol on total inspiratory resistance and respiratory drive in normal nonsnoring men. Alc Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:256–62. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

60. Krol RC, Knuth SL, Bartlett D. Selective reduction of genioglossal muscle activity by alcohol in normal human subjects. Am Rev Resp Dis. 1984;129:247–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

61. Scrima L, Broudy M, Nay KM. Increased severity of obstructive sleep apnea after bedtime alcohol ingestion: diagnostic potential and proposed mechanism of action. Sleep. 1982;5:318–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sleep. 1982;5:318–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

62. Aldrich MS, Shipley JE, Tandon R, Kroll PD, Brower KJ. Sleep-disordered breathing in alcoholics: Association with age. Alc Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:1179–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

63. Mamdani M, Hollyfield R, Ravi SD, Dorus W, Borge GF. Prevalence of sleep apnea among abstinent chronic alcoholic men. Sleep Res. 1989;18:349. [Google Scholar]

64. Bassetti C, Aldrich MS. Alcohol consumption and sleep apnea in patients with TIA and ischemic stroke. Sleep Res. 1996;25:400. [Google Scholar]

65. Aldrich MS, Chervin RD. Alcohol use, obstructive sleep apnea, and sleep-related motor vehicle accidents. Sleep Res. 1997;26:308. [Google Scholar]

66. Aldrich MS, Shipley JE. Alcohol use and periodic limb movement of sleep. Alc Clin Exp Res. 1993;17:192–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

67. Berlin RM, Qayyum U. Sleepwalking: Diagnosis and treatment through the life cycle. Psychosomatics. 1986;27:755–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

68. Roberts RE, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Prospective data on sleep complaints and associated risk factors in an older cohort. Psychosomatic Med. 1999;61:188–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Roberts RE, Shema SJ, Kaplan GA. Prospective data on sleep complaints and associated risk factors in an older cohort. Psychosomatic Med. 1999;61:188–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

69. Kales JD, Kales A, Bixler EO, et al. Biopsychobehavioral correlates of insomnia, V: Clinical characteristics and behavioral correlates. Am J Psych. 1984;141:1371–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

70. Jacobs EA, Reynolds CF, Kupfer DJ, Lovine PA, Ehrenpreis AB. The role of polysomnography in the differential diagnosis of chronic insomnia. Am J Psych. 1988;145:346–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

71. Benca RM, Obermeyer WH, Thisted RA, Gillin C. Sleep and psychiatric disorders. A meta-analysis. Arch Gen Psych. 1992;49:651–68. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

72. Merikangas KR, Angst J, Eaton W, et al. Comorbidity and boundaries of affective disorders with anxiety disorders and substance misuse: Results of an international task force. Br J Psych. 1996;30:58–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

73. Davidson KM. Diagnosis of depression in alcohol dependence; changes in prevalence with drinking status. Br J Psych. 1995;166:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Diagnosis of depression in alcohol dependence; changes in prevalence with drinking status. Br J Psych. 1995;166:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

74. Bliwise NG. Factors related to sleep quality in healthy elderly women. Psychol Aging. 1992;71:83–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

75. Chait LD, Perry JL. Acute and residual effects of alcohol and marijuana, marijuana alone and in combination, on mood and performance. Psychopharm. 1994;115:340–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

76. Haack MR, Harford TC, Parker DA. Alcohol use and depression symptoms among female nursing students. Alc Clin Exp Res. 1988;12:365–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

77. Chang PP, Ford DE, Mead LA, Cooper PL, Klag MJ. Insomnia in young men and subsequent depression. The John Hopkins Precursor Study. Am J Epi. 1997;146:105–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

78. Longo LP, Johnson B. Treatment of insomnia in substance abusing patients. Psych Annals. 1998;28:154–9. [Google Scholar]

79. Greeff AP, Conradie WS. Use of progressive relaxation training for chronic alcoholics with insomnia. Psych Rep. 1998;82:407–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Use of progressive relaxation training for chronic alcoholics with insomnia. Psych Rep. 1998;82:407–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

80. Ciraulo DA, Barnhill JG, Ciraulo AM, et al. Alterations in pharacodynamics of anxiolytsic in abstinent alcoholics: subjective responses, abuse liability, and electroencephalographic effects of alprazolam, diazepam and buspirone. J Clin Pharm. 1997;37:64–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

81. Ciraulo DA, Nace EP. Benzodiazepine treatment of anxiety or insomnia in substance abuse patients. Am J Addict. 2000;9:276–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

82. Sellers EM, Ciraulo DA, Dupont RL, et al. Alprazolam and benzodiazepine dependence. J Clin Psych. 1994;S54:64–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

83. Mueller TI, Godenberg IM, Gordon AL, Keller MB, Warshaw MG. Benzodiazepine use in anxiety disordered patients with and without a history of alcoholism. J Clin Psych. 1996;57:83–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

84. Miller NS, Gold MS. Introduction-benzodiazepines: A major problem. J Sub Abuse Treatment. 1991;8:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

J Sub Abuse Treatment. 1991;8:3–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

85. Friedmann PD, Herman DS, Freedman S, Lemon SC, Ramsey S, Stein MD. Treatment of sleep disturbance in alcohol recovery: A national survey of addiction medicine physicians. J Addict Dis. 2003;22(2):91–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

86. Wiesbeck GA, Weihers HG, Chick J, Boening J. The effects of ritanserin on mood, sleep, vigilance, clinical impression, and social functioning in alcohol-dependent individuals. Alc Alcoholism. 2000;35:384–89. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

87. Malcolm R, Myrick H, Roberts J, Wang W, Anton RF. The differential effects of dedication on mood, sleep disturbance, and work ability in outpatient alcohol detoxification. Am J Addictions. 2002;11:141–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

88. Karam-Hage M, Brwoer K. Gabapentin treatment for insomnia associated with alcohol dependence. Am J Psych. 2000;157:151. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Sleep disorders in alcoholism

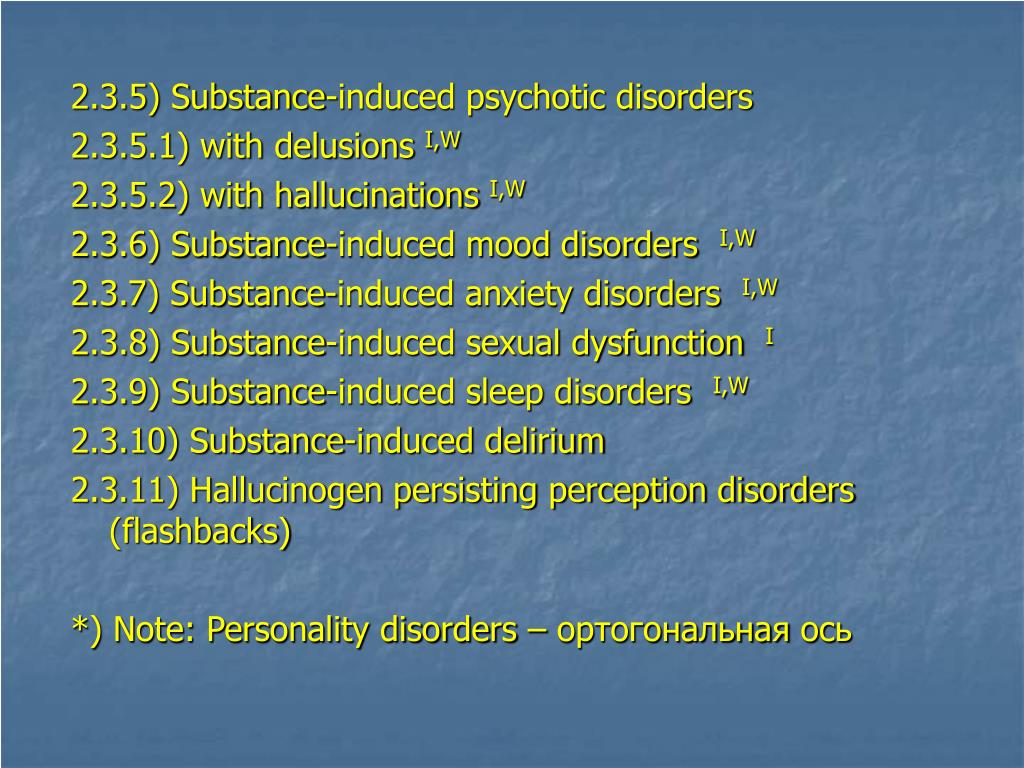

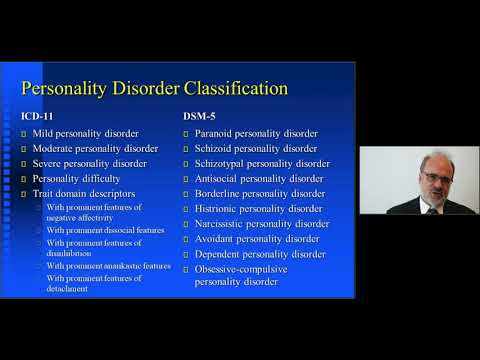

The close relationship between sleep disorders and mental illness has long been known, which led to the identification of a separate group of secondary insomnias, including those associated with alcoholism and drug addiction [1]. In the latest, 3rd version of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders [2], all types of secondary chronic insomnia are combined into one group. Nevertheless, numerous studies of the subjective and objective characteristics of sleep in mentally ill patients have made it possible to identify the features of sleep disturbances characteristic of each of these diseases. Moreover, data were obtained that a change in some sleep indicators (representation of delta sleep, latency of REM sleep) makes it possible to predict the severity of the course and the approach of the next relapse of the disease. When examining patients with sleep disorders, 50% have associated symptoms of mental distress [3]. It has been shown that the risk of developing a depressive disorder in patients with insomnia during their lifetime is 4 times higher than in those without it [4]. Insomnia may precede the onset of a mental disorder, manifest itself simultaneously with its development, or occur in a detailed picture of the disease.

In the latest, 3rd version of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders [2], all types of secondary chronic insomnia are combined into one group. Nevertheless, numerous studies of the subjective and objective characteristics of sleep in mentally ill patients have made it possible to identify the features of sleep disturbances characteristic of each of these diseases. Moreover, data were obtained that a change in some sleep indicators (representation of delta sleep, latency of REM sleep) makes it possible to predict the severity of the course and the approach of the next relapse of the disease. When examining patients with sleep disorders, 50% have associated symptoms of mental distress [3]. It has been shown that the risk of developing a depressive disorder in patients with insomnia during their lifetime is 4 times higher than in those without it [4]. Insomnia may precede the onset of a mental disorder, manifest itself simultaneously with its development, or occur in a detailed picture of the disease. The high efficiency of such insomnia treatment methods as cognitive-behavioral therapy aimed at normalizing the emotional state and behavior also testifies in favor of the presence of a close pathogenetic relationship between sleep disorders and mental disorders.

The high efficiency of such insomnia treatment methods as cognitive-behavioral therapy aimed at normalizing the emotional state and behavior also testifies in favor of the presence of a close pathogenetic relationship between sleep disorders and mental disorders.

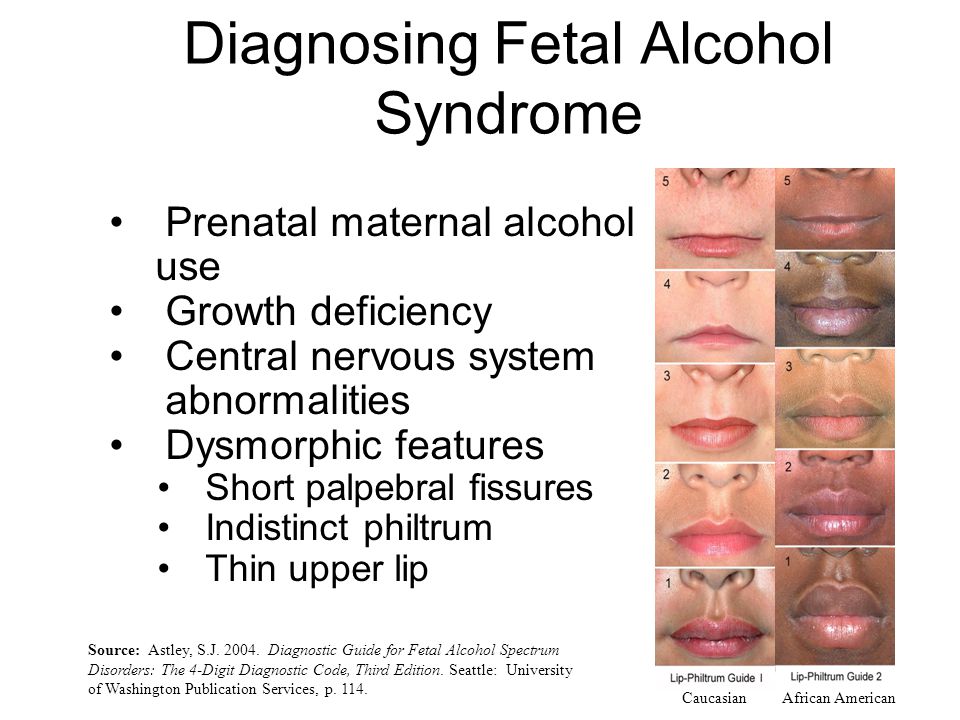

Alcoholism is one of the mental disorders associated with sleep disorders. But in this area, the effect of different doses of alcohol is reasonably differentiated. Despite the obvious toxic effect of ethanol on all organs and systems, there is also evidence of its beneficial effect when used in small doses. This has led to the fact that a number of scientists and medical organizations do not exclude moderate alcohol consumption for preventive purposes [5]. At the household level, it is widely believed that alcohol is used as an affordable sleeping pill; taking a "glass or two" accelerates the onset of sleep. At 1939 N. Kleitman first described such an effect of ethanol taken 60 minutes before sleep (quoted from [6]).

Assessment of the alcohol content in the body is carried out by measuring its concentration in the exhaled air, which depends not only on the amount of ethanol taken, but also on the type of alcoholic beverage, its absorption rate in the gastrointestinal tract, water content in the body, which varies depending on gender and age. It should be borne in mind that the highest level of ethanol in the blood is observed in the first 1-1.5 hours after ingestion. When examining the concentration of alcohol in the exhaled air, two peaks are revealed (after 15-20 minutes and 75 minutes after ingestion), the first of which is associated with the absorption of ethanol in the oral cavity, the second with absorption from the gastrointestinal tract [7]. 4-5 hours after taking alcohol at night, i.e. in the second half of the night, the effect of removing it from the body is observed.

Women reach peak blood alcohol concentration faster than men due to their lower water content in their bodies. The removal of ethanol from the blood also occurs faster in women [8].

The removal of ethanol from the blood also occurs faster in women [8].

It is worth noting the difficulties in conducting placebo-controlled studies of the effectiveness of alcohol, since it is obvious to the subjects that the presence of ethanol in the drink they offer, starting with the amount of alcohol sufficient to achieve 0.07% ethanol content in exhaled air [9]. This creates particular problems in assessing subjective effects (feeling of cheerfulness, concentration of attention), depending on the individual expectations of the subjects from the reception.

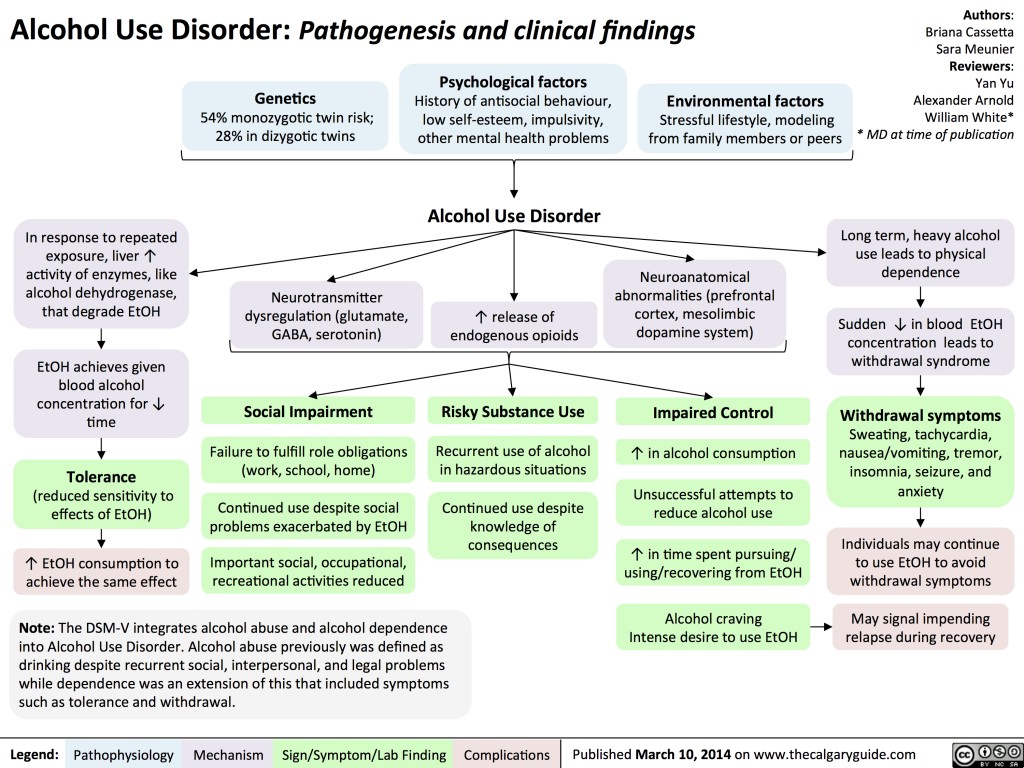

The effect of ethanol on the central nervous system (CNS) is mediated by the improvement of GABAergic and inhibition of glutamate mediation, two systems that reciprocally affect the mechanisms of sleep and wakefulness. The effect of ethanol on precisely these neurotransmitter systems was proven in laboratory studies in which alcohol intake increased or, conversely, slowed down the work of GABA or glutamate-dependent ion channels [10, 11]. The GABAergic system of the reticular formation, thalamus, hypothalamus, and basal forebrain is inhibitory, responsible for the generation of slow-wave sleep, and is the target for the action of the most common hypnotics (barbiturates, benzodiazepine and nonbenzodiazepine GABA-receptor agonists) [12]. Glutamate, in contrast, is an activating neurotransmitter present both in the reticular formation and in the brainstem and forebrain. NMDA receptors are the most numerous group of glutamate receptors, which become the target of the inhibitory action of ethanol, as well as some sedatives and anesthetics [6, 12]. In addition to GABA and glutamate systems, the mediator mediating the hypnotic effect of ethanol is adenosine, which presumably provides the homeostatic mechanism of the sleep-wake cycle (during wakefulness, adenosine accumulates in the CNS, and during sleep, its concentration gradually decreases). Ethanol accelerates synthesis, impairs adenosine reuptake, and can also directly activate adenosine receptors [13].

The GABAergic system of the reticular formation, thalamus, hypothalamus, and basal forebrain is inhibitory, responsible for the generation of slow-wave sleep, and is the target for the action of the most common hypnotics (barbiturates, benzodiazepine and nonbenzodiazepine GABA-receptor agonists) [12]. Glutamate, in contrast, is an activating neurotransmitter present both in the reticular formation and in the brainstem and forebrain. NMDA receptors are the most numerous group of glutamate receptors, which become the target of the inhibitory action of ethanol, as well as some sedatives and anesthetics [6, 12]. In addition to GABA and glutamate systems, the mediator mediating the hypnotic effect of ethanol is adenosine, which presumably provides the homeostatic mechanism of the sleep-wake cycle (during wakefulness, adenosine accumulates in the CNS, and during sleep, its concentration gradually decreases). Ethanol accelerates synthesis, impairs adenosine reuptake, and can also directly activate adenosine receptors [13].

While the effect of ethanol on slow-wave sleep is relatively well understood, the mechanisms of influence on REM sleep (REM), which is regulated by other mediator systems, remain unclear. Some researchers [6] believe that in this case the effect of alcohol is mediated by acetylcholine and glutamate, but clarity on this issue has not been achieved.

Episodic low to moderate alcohol consumption (up to 0.75 g/kg) can cause a short activating effect (due to the rapid release of dopamine and endorphins) followed by a sedative effect corresponding to the descending portion of the ethanol metabolism curve. The use of any doses of ethanol is manifested by a decrease in the time to fall asleep, as well as an increase in the representation of deep stages of sleep and a dose-dependent decrease in the proportion of REM sleep in the first half of the night [14-18]. It is worth emphasizing, however, that different sensitivity to alcohol causes a wide variation in the clinical severity of the effects of alcohol when consumed in different doses. Often, small doses of ethanol do not cause significant sedation, although sleep studies will still detect changes in sleep patterns. In this regard, there is still no general opinion about the dosage sufficient for the development of sleep and changes in its structure.

Often, small doses of ethanol do not cause significant sedation, although sleep studies will still detect changes in sleep patterns. In this regard, there is still no general opinion about the dosage sufficient for the development of sleep and changes in its structure.

As alcohol is eliminated from the body, the so-called release of REM sleep occurs with an increase in its representation. This leads to a feeling of more superficial sleep due to frequent awakenings in FBS [19]. Thus, the overall representation of REM sleep throughout the night after episodic alcohol consumption does not differ significantly from normal indicators, but the described changes in sleep structure are more pronounced in women compared to men (due to the above metabolic features) and do not depend on the presence or absence of cases of alcohol abuse in a family history [14].

Repeated alcohol intake for three consecutive days develops tolerance to the sedative effect and effect on the sleep structure - indicators of deep slow wave sleep and REM sleep return to baseline. Some researchers [6] have observed a return of FBS after the cessation of a short period of alcohol intake: in this case, the proportion of REM sleep exceeded the baseline.

Some researchers [6] have observed a return of FBS after the cessation of a short period of alcohol intake: in this case, the proportion of REM sleep exceeded the baseline.

The effect of ethanol on sleep in alcoholic patients has been well studied. During periods of binges, they fall asleep very quickly, however, the duration of sleep is relatively short, and the phase of slow-wave sleep (SMS) prevails in its structure. In studies of the behavior of such patients [17], when they were provided with free access to alcohol, it was found that periods of sleep and alcohol consumption alternate at short intervals during the day. If you need to sleep for 8 hours or more, the second half of sleep becomes intermittent due to frequent awakenings in FBS [19]. Alcohol withdrawal leads to a sharp decrease in the representation of stages 3-4 of sleep, slow-wave sleep is represented mainly by stages 1-2, while the share of REM sleep increases due to an increase in the number and shortening of sleep cycles, but without an increase in duration FBS in each cycle [20]. Such changes in sleep patterns can persist even up to 2 years after cessation of alcohol intake.

Such changes in sleep patterns can persist even up to 2 years after cessation of alcohol intake.

The risk of developing insomnia in alcoholic disease is higher in women, patients with a family history of alcohol abuse, in patients who began to abuse alcohol at a later age (over 27 years), with a long history of abuse (more than 7 years), with concomitant mental pathology ( endogenous depression, anxiety disorders) [21, 22]. The described features, according to the authors of the relevant works, are evidence of the development of physical dependence on alcohol, since similar changes can be observed with dependence on other drugs (barbiturates, opiates, psychostimulants). Alcohol intake during the period of acute withdrawal eliminates these changes, but they increase again after the cessation of ethanol intake into the body.

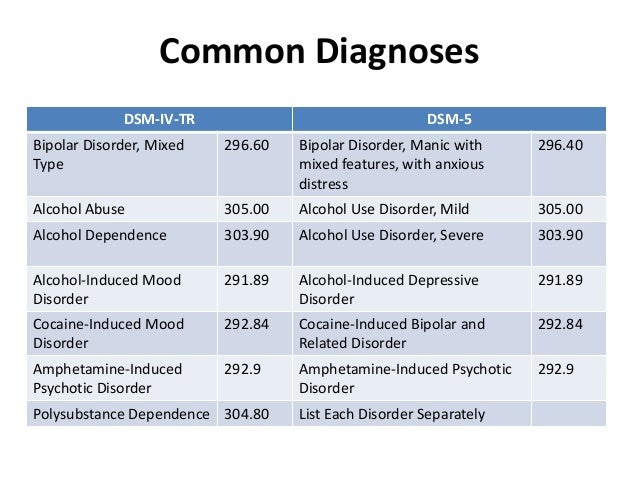

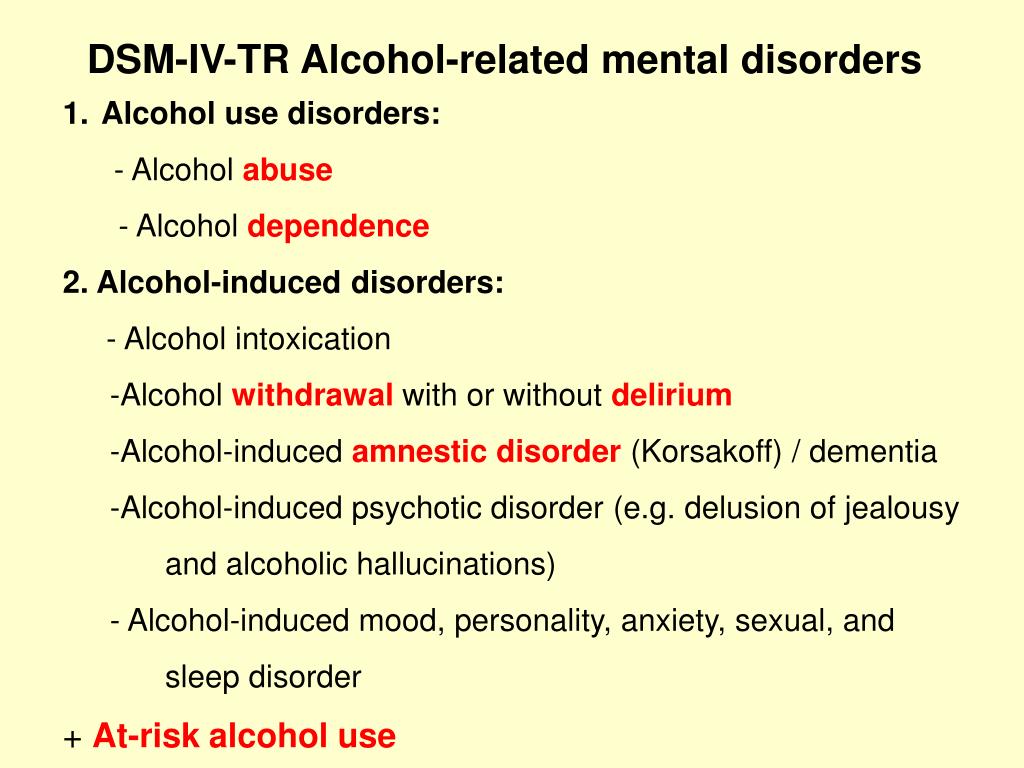

In persons suffering from alcohol dependence, during the period of withdrawal, insomnia disorders are observed in 91% of cases, while the criteria for acute insomnia syndrome are met in 61% of cases [23, 24]. Insomnia is one of the 8 symptoms of alcohol withdrawal according to DSM-V (2 of 8 signs are required for the diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal) [25]. There is an assumption that hallucinations that appear after alcohol withdrawal are an invasion of "rebound" REM sleep in the waking state [26]. However, it is questioned due to the fact that not all patients with hallucinations have the phenomenon of such a "rebound". In the period of remission of alcoholic disease, sleep characteristics such as an increase in FBS pressure (decrease in latency, high proportion, density of rapid eye movements), a decrease in the representation of stages 3–4 of non-REM sleep can be predictors of a relapse of the disease in the next 5–6 months [27] . The presence and severity of sleep disorders during the period of acute withdrawal also has a significant positive relationship with the risk of relapse [21].

Insomnia is one of the 8 symptoms of alcohol withdrawal according to DSM-V (2 of 8 signs are required for the diagnosis of alcohol withdrawal) [25]. There is an assumption that hallucinations that appear after alcohol withdrawal are an invasion of "rebound" REM sleep in the waking state [26]. However, it is questioned due to the fact that not all patients with hallucinations have the phenomenon of such a "rebound". In the period of remission of alcoholic disease, sleep characteristics such as an increase in FBS pressure (decrease in latency, high proportion, density of rapid eye movements), a decrease in the representation of stages 3–4 of non-REM sleep can be predictors of a relapse of the disease in the next 5–6 months [27] . The presence and severity of sleep disorders during the period of acute withdrawal also has a significant positive relationship with the risk of relapse [21].

Studies conducted in the UK and the USA [28, 29] have shown that people who start drinking alcohol at an earlier age and consume it in greater quantities, the daily duration of sleep is significantly less.

Studies of the effects of daytime alcohol consumption, in which subjects had free access to alcoholic beverages before bedtime, gave conflicting results in the form of both subjectively lower levels of alertness and energy, and increased performance [30]. When evaluating them, as mentioned above, one should take into account the difficulties of their interpretation without taking into account individual expectations from drinking alcohol.

With insomnia syndrome, which occurs in the general population in 6% (and some symptoms disturb 48% of people from time to time), 30% of patients resort to alcohol as a sleeping pill, 67% of whom note a positive effect [31]. Moreover, the positive effect of ethanol on the rate of falling asleep and the depth of sleep in those suffering from insomnia is manifested in doses that are lower than those required to achieve the same effect in healthy people [32]. At the same time, tolerance quickly develops to the sedative effect of alcohol both at the receptor and psychological levels - this leads to the fact that patients with insomnia increase the amount of alcohol taken before bedtime. As a result, "therapeutic" alcohol use can quietly transform into alcohol addiction. In studies with free access to alcoholic beverages, patients with insomnia were more likely to choose alcohol before bed than healthy subjects. This is also consistent with epidemiological data showing that people with sleep problems are twice as likely to suffer from alcoholism than those who did not have sleep problems: 7 and 3.8%, respectively [4, 33].

As a result, "therapeutic" alcohol use can quietly transform into alcohol addiction. In studies with free access to alcoholic beverages, patients with insomnia were more likely to choose alcohol before bed than healthy subjects. This is also consistent with epidemiological data showing that people with sleep problems are twice as likely to suffer from alcoholism than those who did not have sleep problems: 7 and 3.8%, respectively [4, 33].

In the event that alcohol abuse has developed against the background of existing insomnia, insomnia complaints intensify in the withdrawal period, which creates conditions for a relapse. Thus, a kind of "vicious circle" arises, for the destruction of which it is necessary to make great efforts both on the part of the patient and the doctor, since the selection of drug therapy in such patients is complicated by a higher risk of developing drug dependence. Thus, benzodiazepine receptor agonists, which have a high risk of developing addiction and addiction, affecting the structure of sleep and causing "rebound" insomnia upon withdrawal, are not recommended for the relief of insomnia in the withdrawal period, with the exception of cases of delirium tremens [21]. An additional risk of taking benzodiazepines is associated with the possibility of their overdose when used with alcohol.

An additional risk of taking benzodiazepines is associated with the possibility of their overdose when used with alcohol.

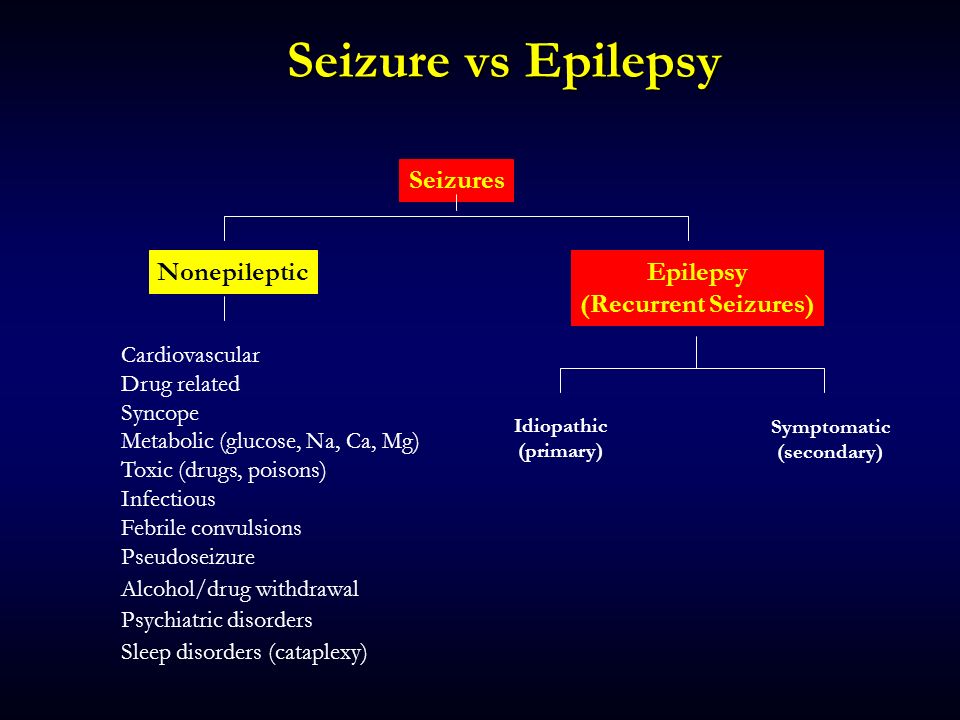

In the period of abstinence from taking alcohol, antidepressants and anticonvulsants are preferred as sleeping pills, taking into account the increased risk of developing an epileptic seizure as a result of reactivation of suppressed excitatory systems. Studies of the effect of carbamazepine and gabapentin on the symptoms of insomnia in the withdrawal period have shown that their effectiveness exceeds that of benzodiazepines [34, 35]. The more favorable spectrum of side effects of gabapentin should also be noted, the metabolism of which does not depend on liver enzymes and which has a lower potential for dependence and abuse.

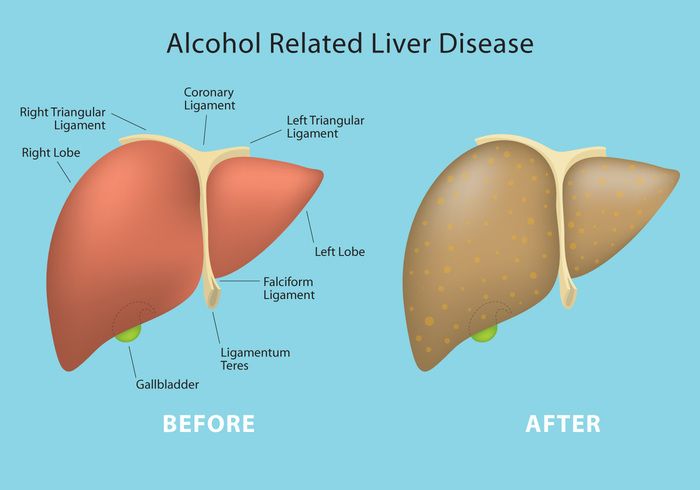

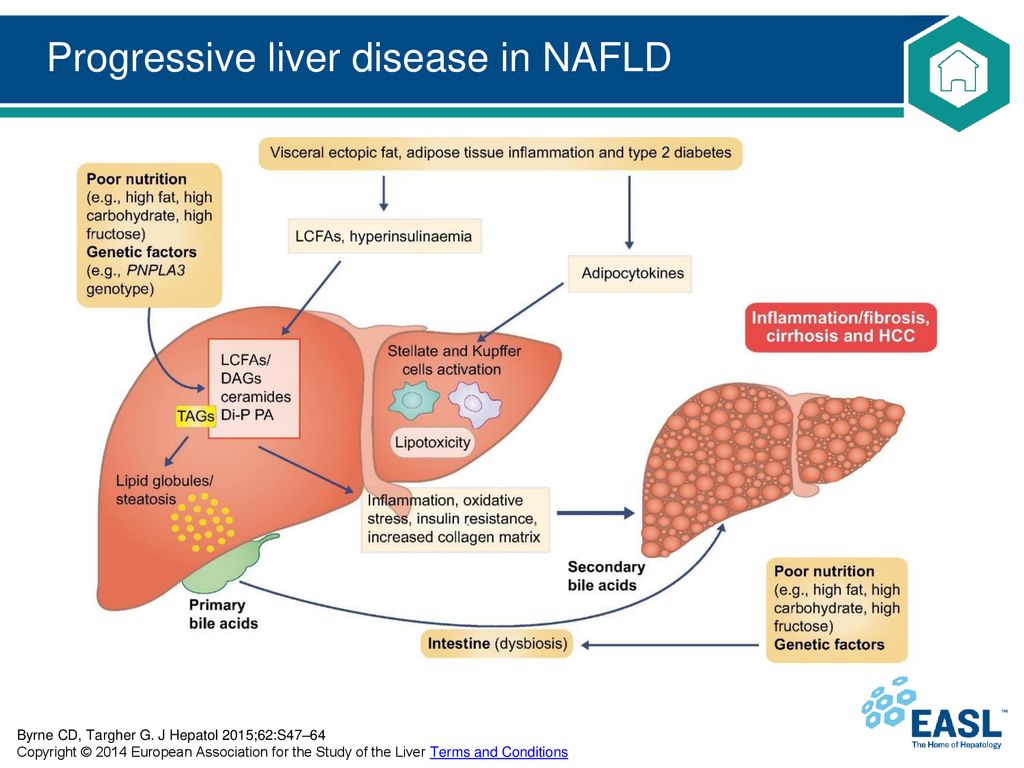

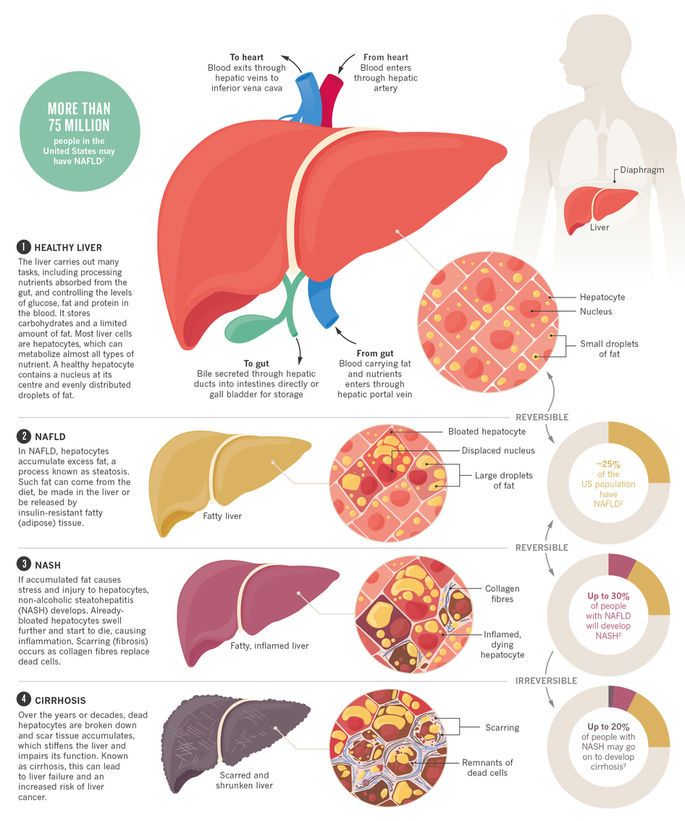

If long-term treatment of insomnia and depression, especially noted before the onset of alcohol abuse, is required, antidepressants of the sedative spectrum become the drugs of choice. The inevitable damaging effect of alcohol on the liver necessitates the choice of a drug with a minimal effect on it. High subjective and objective efficacy in relation to the symptoms of insomnia, including alcohol withdrawal, a low risk of developing dependence and abuse of trazodone (in Russia it is represented by the drug trittico) has been proven in a number of foreign and domestic studies [21, 36, 37]. The extrahepatic metabolism of this drug allows it to be prescribed to patients with liver disease.

High subjective and objective efficacy in relation to the symptoms of insomnia, including alcohol withdrawal, a low risk of developing dependence and abuse of trazodone (in Russia it is represented by the drug trittico) has been proven in a number of foreign and domestic studies [21, 36, 37]. The extrahepatic metabolism of this drug allows it to be prescribed to patients with liver disease.

Trazodone is a triazolopyridine derivative and, as an antidepressant, belongs to a unique class of serotonin receptor antagonists/serotonin reuptake inhibitors. Its multifaceted therapeutic effect is primarily explained by its effect on serotonin transmission. Trazodone is a 5HT1A receptor agonist, 5HT2A-, 5HT2B-, 5HT2C receptor antagonist, and serotonin reuptake inhibitor. In addition, it has a blocking effect on α1- and α2-adrenergic receptors and h2-histamine receptors. The drug is approved in many countries as a treatment for major depressive disorder in adults. Trazodone has been shown to be effective in clinical trials comparable to tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) and serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. It is important to note that the use of this drug does not cause serious side effects characteristic of SSRIs, such as insomnia, increased anxiety, and sexual dysfunction [38].

It is important to note that the use of this drug does not cause serious side effects characteristic of SSRIs, such as insomnia, increased anxiety, and sexual dysfunction [38].

The results of successful use of trazodone for bulimia, benzodiazepine and alcohol dependence, fibromyalgia, degenerative diseases of the central nervous system, schizophrenia, chronic pain syndromes, diabetic polyneuropathy, sexual dysfunction have been published [39].

Russian multicenter study of the effectiveness of the use of trittiko for the correction of sleep disorders in depressive disorders, was conducted in 2011-2012. [36]. It included 30 patients diagnosed with a depressive episode or recurrent depression. Trittico was used at an average dose of 150 mg for 42 days, along with a decrease in the severity of anxiety and depression, there was an improvement in sleep parameters both according to questionnaires and according to the results of an objective study (polysomnography). The authors of the study concluded that the drug is effective and safe in the treatment of patients with non-psychotic depressive disorders with sleep disorders.

Concerning other groups of drugs commonly used to treat insomnia (antipsychotics, melatonin, ethanolamines), convincing evidence of their effectiveness and safety in relation to patients suffering from alcohol dependence is not yet available.

A number of studies [40, 41] have found a positive effect of the method of cognitive behavioral therapy on the quality of sleep and the severity of daytime symptoms compared with placebo. Comparative studies of the effectiveness of this kind of non-specific therapy and drug treatment in alcohol withdrawal have not been conducted. But its further study is undoubtedly promising, taking into account the toxic effect of ethanol on all organs and systems of the patient, which causes contraindications for drug therapy.

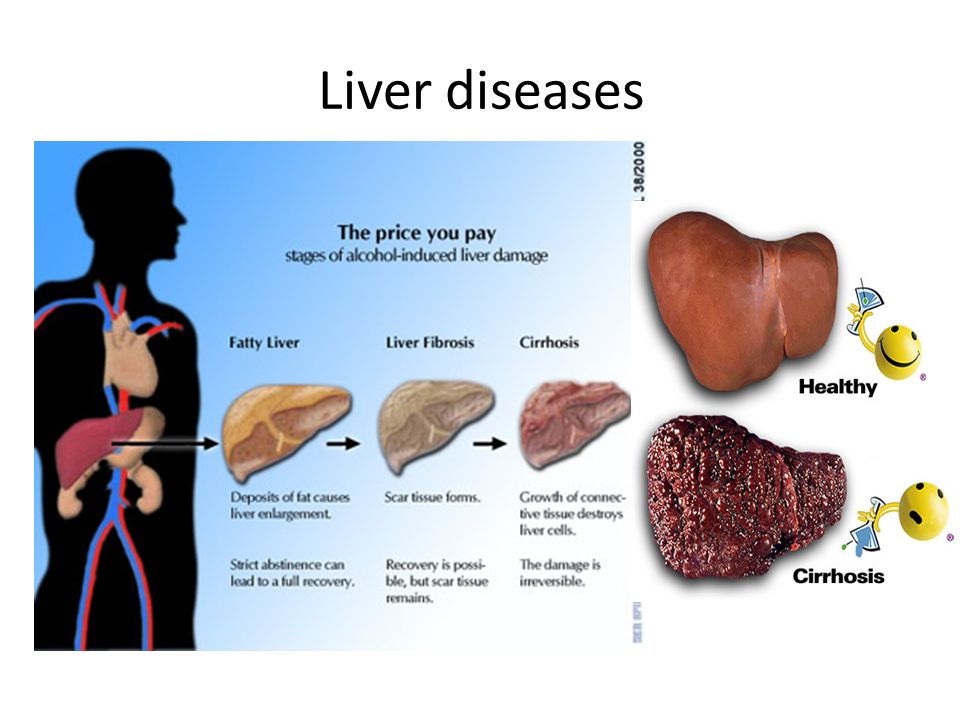

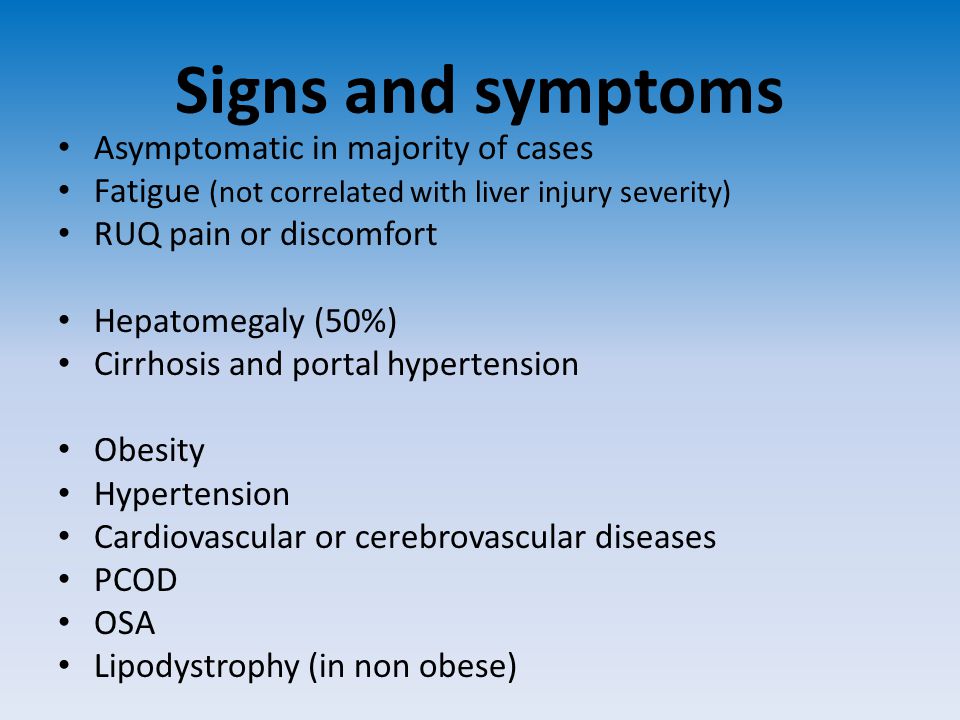

Mention should be made of the effect of alcohol consumption on sleep disorders other than those described. So, we are talking about breathing disorders during sleep, which among all sleep disorders are in second place in terms of prevalence after insomnia: 3-8% in men, 2% in women [42]. Alcohol can contribute to the manifestation of sleep apnea with an existing predisposition [43]. This is due to the ability of ethanol to inhibit the respiratory center of the medulla oblongata, reduce reflex awakening in response to respiratory arrest, and directly reduce the tone of the soft tissues of the upper respiratory tract. The considered effects of ethanol are reflected in studies [44], where alcohol consumption before bedtime led to an increase in the apnea-hypopnea index from 22 to 28 episodes per hour and a decrease in mean blood saturation from 78 to 62%, requiring the selection of a higher pressure of overmask ventilation with constant positive pressure (CPAP therapy) to eliminate breathing disorders during sleep [43]. Probably, there is also an inverse relationship, since among those suffering from alcoholism, breathing disorders during sleep are more common than among healthy people of the same age [45].

Alcohol can contribute to the manifestation of sleep apnea with an existing predisposition [43]. This is due to the ability of ethanol to inhibit the respiratory center of the medulla oblongata, reduce reflex awakening in response to respiratory arrest, and directly reduce the tone of the soft tissues of the upper respiratory tract. The considered effects of ethanol are reflected in studies [44], where alcohol consumption before bedtime led to an increase in the apnea-hypopnea index from 22 to 28 episodes per hour and a decrease in mean blood saturation from 78 to 62%, requiring the selection of a higher pressure of overmask ventilation with constant positive pressure (CPAP therapy) to eliminate breathing disorders during sleep [43]. Probably, there is also an inverse relationship, since among those suffering from alcoholism, breathing disorders during sleep are more common than among healthy people of the same age [45].

In addition to the above, it can also be added that alcohol reduces the manifestations of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movements during sleep, but this effect disappears as tolerance develops rapidly. In addition, periodic limb movements themselves can lead to awakenings and exacerbate the fragmentation of sleep caused by alcohol elimination. By increasing the representation of deep sleep, alcohol contributes to the increase in sleepwalking and other parasomnias that occur in non-REM sleep.

In addition, periodic limb movements themselves can lead to awakenings and exacerbate the fragmentation of sleep caused by alcohol elimination. By increasing the representation of deep sleep, alcohol contributes to the increase in sleepwalking and other parasomnias that occur in non-REM sleep.

Due to the development of a sedative effect, alcohol worsens the daytime manifestations of narcolepsy, which itself is characterized by bouts of imperative daytime sleepiness. Patients who have narcolepsy onset in childhood and adolescence avoid alcohol, while those with onset in adulthood are sometimes habitually prevented from giving up.

So, since alcohol has a generalized toxic effect, this cannot but affect the sleep and wake systems that are sensitive to exogenous and endogenous influences. Despite the seeming improvement in sleep with insomnia, the use of alcohol as a sleeping pill tends to increase uncontrollably and lead to difficult-to-treat sleep structure disorders and the development of addiction. It is important to remember that insomnia is often combined with other sleep disorders, which, under its mask, can cause daytime sleepiness (breathing disorders during sleep, restless legs syndrome), frequent awakenings (periodic limb movement syndrome during sleep). Drinking alcohol in these cases can not only aggravate the course of the disease, but also lead to catastrophic consequences (stopping breathing due to depression of the respiratory center during sleep apnea). Thus, alcohol, even in small doses, cannot be recommended to patients with complaints of sleep disorders. A history of abuse of alcohol or drugs that affect sleep should lead the physician to think about the risk of relapse.

It is important to remember that insomnia is often combined with other sleep disorders, which, under its mask, can cause daytime sleepiness (breathing disorders during sleep, restless legs syndrome), frequent awakenings (periodic limb movement syndrome during sleep). Drinking alcohol in these cases can not only aggravate the course of the disease, but also lead to catastrophic consequences (stopping breathing due to depression of the respiratory center during sleep apnea). Thus, alcohol, even in small doses, cannot be recommended to patients with complaints of sleep disorders. A history of abuse of alcohol or drugs that affect sleep should lead the physician to think about the risk of relapse.

Alcohol and sleep disorders | Efremov

1. Poluektov M.G., Buzunov R.V., Averbukh V.M. et al. Draft clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of chronic insomnia in adults. Neurology and rheumatology. Supplement to Consilium Medicum. 2016; 2:41-51.

2. Poluektov M. G., Pchelina P.V., Palman A.D. Sleep disorders in alcoholism. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. Special issues. 2015; 115(4):34-39. doi: 10.17116/jnevro20151154234-39

G., Pchelina P.V., Palman A.D. Sleep disorders in alcoholism. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakov. Special issues. 2015; 115(4):34-39. doi: 10.17116/jnevro20151154234-39

3. Amaral MOP, de Figueiredo Pereira CM, Martins DIS, Sakellarides CT. Prevalence and risk factors for insomnia among Portuguese adolescents. European journal of pediatrics. 2013; 172(10):1305-1311. doi: 10.1007/s00431-013-2037-0

4. Angarita GA, Emadi N., Hodges S., Morgan PT. Sleep abnormalities associated with alcohol, cannabis, cocaine, and opiate use: a comprehensive review. Addiction science & clinical practice. 2016; 11(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s13722-016-0056-7

5. Arnedt JT. Insomnia in patients with a substance use disorder. 2017 UpToDate. Retrieved from https://www.uptodate.com/contents/insomnia-inpatientswith-a-substance-use-disorder. (Accessed 03/02/2020)

6. Bernert RA, Kim JS., Iwata NG, Perlis ML. Sleep disturbances as an evidence-based suicide risk factor. Current psychiatry reports. 2015; 17(3):15. doi:10.1007/s11920-015-0554-4

2015; 17(3):15. doi:10.1007/s11920-015-0554-4

7. Blumenthal H, Taylor DJ, Cloutier RM, Baxley C, Lasslett H. The links between social anxiety disorder, insomnia symptoms, and alcohol use disorders: findings from a large sample of adolescents in the United States. Behavior therapy. 2019; 50(1): 50-59. doi: 10.1016/j.beth.2018.03.010

8. Brooks AT, Raju S, Barb JJ, Kazmi N, Chakravorty S, Krumlauf M, Wallen GR. Sleep Regularity Index in Patients with Alcohol Dependence: Daytime Napping and Mood Disorders as Correlates of Interest. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020; 17(1):331. doi:10.3390/ijerph27010331

9. Brower KJ, Perron BE. Prevalence and correlates of withdrawal-related insomnia among adults with alcohol dependence: results from a national survey. The American journal on addictions. 2010; 19(3):238-244. doi: 10.1111/j.1521-0391.2010.00035.x

10. Brower KJ, Wojnar M, Sliwerska E, Armitage R, Burmeister M. PER3 polymorphism and insomnia severity in alcohol dependence. sleep; 2012; 35(4):571-577. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1748

sleep; 2012; 35(4):571-577. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1748

11. Brower KJ. Assessment and treatment of insomnia in adult patients with alcohol use disorders. alcohol. 2015; 49(4):417-427. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.12.003

12. Canham SL, Kaufmann CN, Mauro PM, Mojtabai R, Spira AP. Binge drinking and insomnia in middle-aged and older adults: the Health and Retirement Study. International journal of geriatric psychiatry. 2015; 30(3):284-291. doi: 10.1002/gps.4139

13. Chakravorty S, Grandner MA, Mavandadi S, Perlis ML, Sturgis EB, Oslin DW. Suicidal ideation in veterans misusing alcohol: relationships with insomnia symptoms and sleep duration. Addictive behaviors. 2014; 39(2):399-405. doi: 10.1016/j.ad-dbeh.2013.09.022

14. Chakravorty S, Hanlon AL, Kuna ST, Ross RJ, Kampman KM, Witte LM, Perlis Michael L, Oslin David W. The effects of quetiapine on sleep in recovering alcohol-dependent subjects: a pilot study. Journal of clinical psychopharmacology. 2014; 34(3):350-354. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000130

doi: 10.1097/JCP.0000000000000130

15. Chaudhary NS, Kampman KM, Kranzler HR, Grandner MA, Debbarma S, Chakravorty S. Insomnia in alcohol dependent subjects is associated with greater psychosocial problem severity. Addictive behaviors. 2015; 50:165-172. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2015.06.021

16. Chen H, Bo QG, Jia CX, Liu X. Sleep problems in relation to smoking and alcohol use in Chinese adolescents. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 2017; 205(5):353-360. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000661

17. Colrain IM, Nicholas CL, Baker FC. Alcohol and the sleeping brain. In Handbook of clinical neurology. Elsevier. 2014; 125:415-431. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-62619-6.00024-0

18. Dolsen MR, Harvey AG. Life‐time history of insomnia and hypersomnia symptoms as correlates of alcohol, cocaine and heroin use and relapse among adults seeking substance use treatment in the United States from 1991 to 1994. Addiction. 2017; 112(6):1104-1111. doi: 10.1111/add.13772

19. Eban-Rothschild A, Appelbaum L, de Lecea L. Neuronal mechanisms for sleep/wake regulation and modulatory drive. neuropsychopharmacology. 2018; 43(5):937-952. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.294

Eban-Rothschild A, Appelbaum L, de Lecea L. Neuronal mechanisms for sleep/wake regulation and modulatory drive. neuropsychopharmacology. 2018; 43(5):937-952. doi: 10.1038/npp.2017.294

20. Fortuna LR, Cook B, Porche MV, Wang Y, Amaris AM, Alegria M. Sleep disturbance as a predictor of time to drug and alcohol use treatment in primary care. Sleep medicine. 2018; 42:31-37. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2017.12.009

21. Goodhines PA, Gellis LA, Kim J, Fucito LM, Park A. Self-medication for sleep in college students: Concurrent and prospective associations with sleep and alcohol behavior. Behavioral sleep medicine. 2019; 17(3):327-341. doi: 10.1080/15402002.2017.1357119

22. GortneyJS, Patel P, Raub JN, Kokoska L, Hannawa M, Argyris A. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome in medical patients. Cleveland Clinic journal of medicine. 2016; 83(1): 67-79. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.83a.14061

23. Guo R, Simasko SM, Jansen HT. Chronic alcohol consumption in rats leads to desynchrony in diurnal rhythms and molecular clocks. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016; 40(2):291-300. doi: 10.1111/acer.12944

Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2016; 40(2):291-300. doi: 10.1111/acer.12944

24. Haario P, Rahkonen O, Laaksonen M, Lahelma E, Lallukka T. Bidirectional associations between insomnia symptoms and unhealthy behaviors. Journal of sleep research, 2013; 22(1): 89-95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2012.01043.x

25. Hartwell EE, Bujarski S, Glasner-Edwards S, Ray LA. The association of alcohol severity and sleep quality in problem drinkers. Alcohol and alcoholism. 2015; 50(5):536-541. doi:10.1093/alcalc/agv046

26. Hasler BP, Kirisci L, Clark DB. Restless sleep and variable sleep timing during late childhood accel- erate the onset of alcohol and other drug in- volvement. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2016; 77(4):649-655. doi:10.15288/jsad.2016.77.649

27. Hasler BP, Martin CS, Wood DS, Rosario B, Clark DB. A longitudinal study of insomnia and other sleep complaints in adolescents with and without alcohol use disorders. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014; 38(8):2225-2233. doi: 10.1111/acer.12474

2014; 38(8):2225-2233. doi: 10.1111/acer.12474

28. Hasler BP, Soehner AM, Clark DB. Sleep and circadian contributions to adolescent alcohol use disorder. alcohol. 2015; 49(4):377-387. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.06.010

29. He S, Brooks AT, Kampman KM, Chakravorty S. The relationship between alcohol craving and insomnia symptoms in alcohol-dependent individuals. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2019; 54(3):287-294. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agz029

30. Jesse S, Bråthen G, Ferrara M, Keindl M, Ben-Menachem E, Tanasescu R et al. Alcohol withdrawal syndrome: mechanisms, manifestations, and management. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. 2017; 135(1):4-16. doi:10.1111/ane.12671

31. Kim JI, Park H, Kim JH. Alcohol use disorders and insomnia mediate the association between PTSD symptoms and suicidal ideation in Korean firefighters. depression and anxiety. 2018; 35(11):1095-1103. doi:10.1002/da.22803

32. Klimkiewicz A, Bohnert AS, Jakubczyk A, Ilgen MA, Wojnar M, Brower K. The association between insomnia and suicidal thoughts in adults treated for alcohol dependence in Poland. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2012; 122(1-2):160-163. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.021

The association between insomnia and suicidal thoughts in adults treated for alcohol dependence in Poland. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2012; 122(1-2):160-163. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.09.021

33. Ko S, Park Y, Kang M, Hong H. Influence of severity of problem drinking, circadian rhythm and sleep quality on sleep disorder in alcohol use disorder patients. J Korean Biol Nurs Sci. 2017; 19(1):48. doi:10.7586/jkbns.2017.19.1.48

34. Kolla BP, Bostwick JM. Insomnia: The Neglected Component of Alcohol Recovery. J Addict Res Ther. 2011; 2:0e2. doi: 10.4172/2155-6105.100001000e102

35. Kolla BP, Schneekloth T, Mansukhani MP, Biernacka JM, Hall-Flavin D, Karpyak, V et al. The association between sleep disturbances and alcohol relapse: A 12-month observational cohort study. The American journal on addictions. 2015; 24(4):362-367. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12199

36. Koob GF, Colrain IM. Alcohol use disorder and sleep disturbances: a feed-forward allostatic framework. neuropsychopharmacology. 2020; 45(1):141-165. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0446-0

neuropsychopharmacology. 2020; 45(1):141-165. doi: 10.1038/s41386-019-0446-0

37. Lee HK. Factors influencing sleep in people with alcoholism. Journal of Korean Academy of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing. 2010; 19(3):271-277. doi: 10.12934/jkpmhn.2010.19.3.271

38. Magnée EH, de Weert-van Oene GH, Wijdeveld TA, Coenen AM, de Jong CA. Sleep disturbances are associated with reduced health‐related quality of life in patients with substance use disorders. The American journal on addictions. 2015; 24(6):515-522. doi: 10.1111/ajad.12243

39. Martindale SL, Hurley RA, Taber KH. Chronic alcohol use and sleep homeostasis: Risk factors and neuroimaging of recovery. The Journal of neuropsychiatry and clinical neurosciences. 2017; 29(1):A6-5. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.16110307

40. Miller MB, DiBello AM, Carey KB, Pedersen ER. Insomnia moderates the association between alcohol use and consequences among young adult veterans. Addictive behaviors. 2017; 75:59-63. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.06.020

doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.06.020

41. Miller MB, Donahue ML, Carey KB, Scott-Sheldon LA. Insomnia treatment in the context of alcohol use disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2017; 181:200-207. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.09.029

42. Miller MB, Janssen T, Jackson KM. The prospective association between sleep and initiation of substance use in young adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2017; 60(2):154-160. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.08.019

43. Morioka H, Itani O, Kaneita Y, Ikeda M, Kondo S, Yamamoto R, Ohida, T. Associations between sleep disturbance and alcohol drinking: a largescale epidemiological study of adolescents in Japan. alcohol. 2013; 47(8):619-628. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2013.09.041

44. Nadorff MR, Salem T, Winer ES, Lamis DA, Nazem S, Berman ME. Explaining alcohol use and suicide risk: a moderated mediation model involving insomnia symptoms and gender. Journal of clinical sleep medicine. 2014; 10(12):1317-1323. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4288

2014; 10(12):1317-1323. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.4288

45. Nguyen-Louie TT, Brumback T, Worley MJ, Colrain IM, Matt GE, Squeglia, LM, Tapert SF. Effects of sleep on substance use in adolescents: a longitudinal perspective. Addiction biology. 2018; 23(2):750-760. doi:10.1111/adb.12519

46. Onaolapo OJ, Onaolapo AY. Melatonin in drug addiction and addiction management: Exploring an evolving multidimensional relationship. World journal of psychiatry. 2018; 8(2):64. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v8.i2.64

47. Park SY, Oh MK, Lee BS, Kim HG, Lee WJ, Lee JH et al. The effects of alcohol on quality of sleep. Korean journal of family medicine. 2015; 36(6):294. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2015.36.6.294

48. Perney P, Lehert P. Insomnia in alcohol-dependent patients: prevalence, risk factors and acamprosate effect: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Alcohol and Alcoholism. 2018; 53(5):611-618. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agy013

49. Perney P, Rigole H, Mason B, Dematteis M, Lehert P. Measuring sleep disturbances in patients with alcohol use disorders: a short questionnaire suitable for routine practice. Journal of addiction medicine. 2015; 9(1):25-30. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000063

Journal of addiction medicine. 2015; 9(1):25-30. doi: 10.1097/ADM.0000000000000063

50. Pieters S, Van Der Vorst H, Burk WJ, Wiers RW, Engels RC. Puberty-dependent sleep regulation and alcohol use in early adolescents. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2010; 34(9):1512-1518. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2010.01235.x

51. Popovici I, French MT. Binge drinking and sleep problems among young adults. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2013; 132(1-2):207-215. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.001

52. Roehrs T, Roth T. Insomnia as a path to alcoholism: tolerance development and dose escalation. Sleep. 2018; 41(8):zsy091. doi: 10.1093/sleep/zsy091

53. Samsonsen C, Myklebust H, Strindler T, Bråthen G, Helde G, Brodtkorb E. The seizure precipitating effect of alcohol: A prospective observational crossover study. epilepsy research. 2018; 143:82-89. doi: 10.1016/j.epplepsyres.2018.04.007

54. Saper CB, Fuller PM. Wake–sleep circuitry: an overview. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2017; 44:186-192. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.03.021

2017; 44:186-192. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2017.03.021

55. Siomos KE, Avagianou PA, Floros GD, Skenteris N, Mouzas OD, Theodorou K, Angelopoulos NV. Psychosocial correlates of insomnia in an adolescent population. Child Psychiatry & Human Development. 2010; 41(3):262-273. doi: 10.1007/s10578-009-0166-5

56. Sivertsen B, Skogen, JC, Jakobsen R, Hysing M. Sleep and use of alcohol and drug in adolescence. A large population-based study of Norwegian adolescents aged 16 to 19years. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2015; 149:180-186. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.01.045

57. Skarupke C, Schlack R, Lange K, Goerke M, Dueck A, Thome J, Cohrs S. Insomnia complaints and substance use in German adolescents: did we underestimate the role of coffee consumption? Results of the KiGGS study. Journal of neural transmission. 2017; 124(1):69-78. doi: 10.1007/s00702-015-1448-7

58. Smith LJ, Gallagher MW, Tran JK, Vujanovic AA. Posttraumatic stress, alcohol use, and alcohol use reasons in firefighters: the role of sleep disturbance. Comprehensive psychiatry. 2018; 87:64-71. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.09.001

Comprehensive psychiatry. 2018; 87:64-71. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.09.001

59. Sung YK, La Flair LN, Mojtabai R, Lee LC, Spivak S, Crum RM. The association of alcohol use disorders with suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in a population-based sample with mood symptoms. Archives of suicide research. 2016; 20(2):219-232. doi: 10.1080/13811118.2015.1004489

60. Thakkar MM, Sharma R, Sahota P. Alcohol disrupts sleep homeostasis. alcohol. 2015; 49(4):299-310. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2014.07.019

61. van SchrojensteinLantman M., Roth T, Roehrs T, Verster JC. Alcohol hangover, sleep quality, and daytime sleepiness. Sleep and Vigilance. 2017; 1(1):37-41. doi: 10.1007/s41782-017-0008-7

62. Vengeliene V, Noori HR, Spanagel R. Activation of melatonin receptors reduces relapse-like alcohol consumption. neuropsychopharmacology. 2015; 40(13):2897-2906. doi:10.1038/npp.2015.143

63. Wallen GR, Brooks MAT, Whiting MB, Clark R, Krumlauf MMC, Yang L, Schwandt ML, George DT, Ramchandani VA.