Adhd and epilepsy

ADHD as a Symptom | Epilepsy Foundation

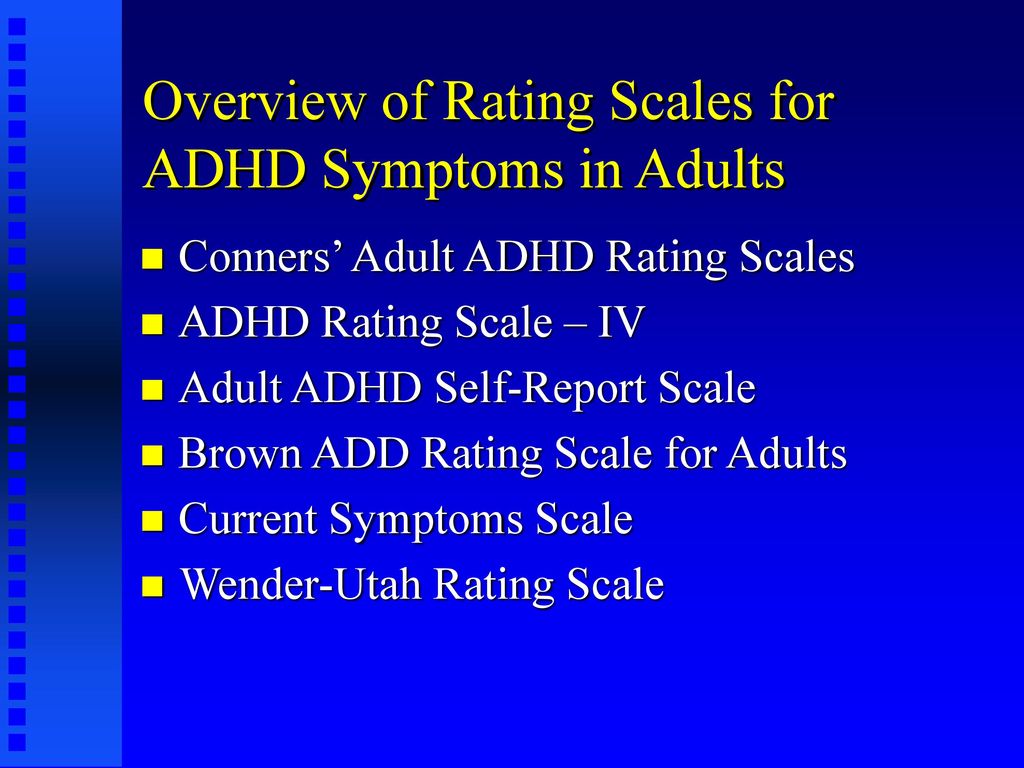

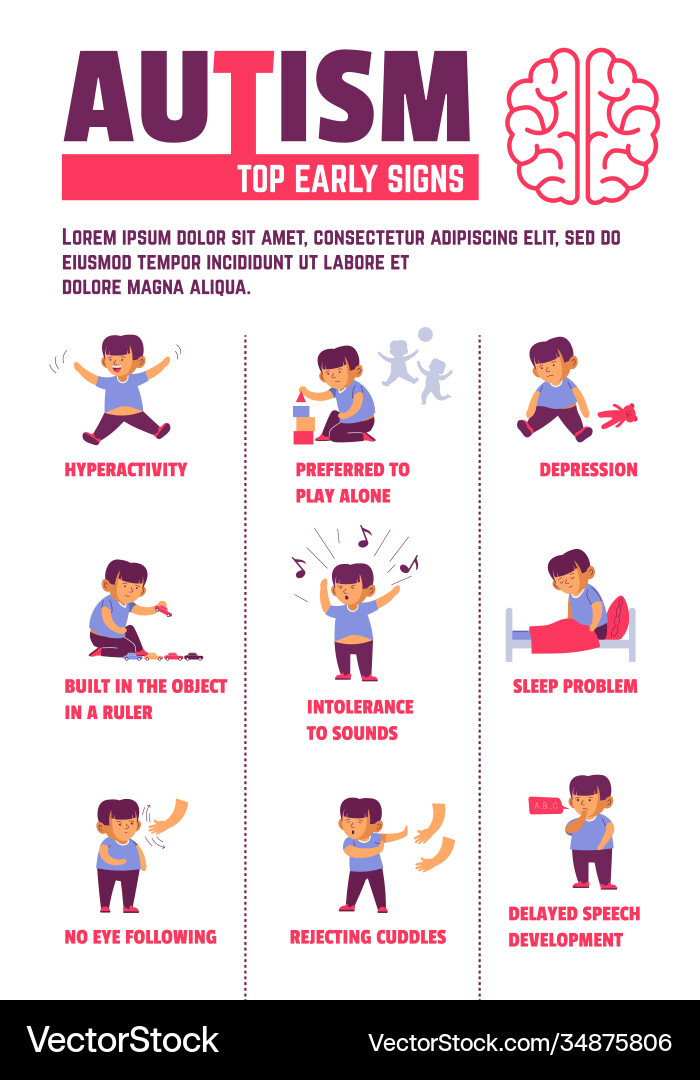

About ADHD

There are three types or “presentations” of ADHD:

- Predominantly inattentive

- Predominantly hyperactive-impulsive

- Combined

People with ADHD that is mostly inattentive typically have trouble with:

- Focusing on details or not making careless mistakes

- Difficulty paying attention for a period of time

- Listening

- Following instructions

- Organizing

- Doing tasks requiring sustained mental effort

- Keeping track of belongings

- Not getting easily distracted

- Remembering things while doing daily activities

People with ADHD hyperactive-impulsive presentation have symptoms such as:

- Constant fidgeting with their hands or feet or squirming in their chair

- Difficulty remaining seated

- Run about or climb excessively in children; extreme restlessness in adults

- Difficulty engaging in activities quietly

- Act as if driven by a motor

- Excessively talkative

- Tendency to blurt out answers before questions have been completed

- Difficulty waiting or taking turns

- Interrupts or intrudes upon others

In the combined presentation of ADHD, people have both inattentive and hyperactive/impulsive symptoms.

Treating both ADHD and Epilepsy

Treating someone with both epilepsy and ADHD can be challenging. Some seizure medicines can make ADHD symptoms worse. Some people are concerned that stimulant medication, often used to treat ADHD, can trigger seizures.

A review of research on ADHD in people with epilepsy showed that stimulant medications can effectively treat symptoms of ADHD, but the medicine’s effect may be lower than what is seen in children with ADHD without epilepsy. The risk of increased seizure frequency appears to be minimal with stimulant treatment. However, people should be warned of the possible risks and closely monitored for increased seizures. The researchers also pointed out the studies that showed this minimal risk were limited by the small amount of people participating in each study.

When people have both ADHD and epilepsy, it’s critical to work with health care professionals knowledgeable about epilepsy, behavior, and thinking. A treatment plan that addresses both the epilepsy and ADHD should be developed. The health care team needs to consider the following:

The health care team needs to consider the following:

- Symptoms of ADHD may complicate the diagnosis of epilepsy, as they may be mistaken for seizures.

- If a person is having seizures, treating these first should be the priority. If seizures can be controlled, some symptoms thought to be due to ADHD may improve.

- Tracking how symptoms progress or change on treatment will help decide next steps.

- When symptoms of ADHD remain separate from seizures or in a person with controlled epilepsy, the ADHD should be treated. Reducing symptoms of ADHD may lessen stress and improve the person’s ability to manage his or her medication and life challenges.

- Treatment plans are ongoing and should be reviewed at least annually to make sure the treatment is working and to adjust as needed.

Treatment options for ADHD include the following:

- Behavioral or cognitive behavioral therapy

- Medication

- Skills training

- Coaching

- School supports and accommodations

Interventions should be tailored to each person to help control symptoms, cope with both disorders, improve overall psychological well-being, and manage social relationships. Family involvement is important, too, in many of these therapies. Both ADHD and epilepsy affect the family. The family’s understanding of, and confidence in managing, the impact of both disorders should be addressed in the treatment plan.

Family involvement is important, too, in many of these therapies. Both ADHD and epilepsy affect the family. The family’s understanding of, and confidence in managing, the impact of both disorders should be addressed in the treatment plan.

What Research Says About the Link

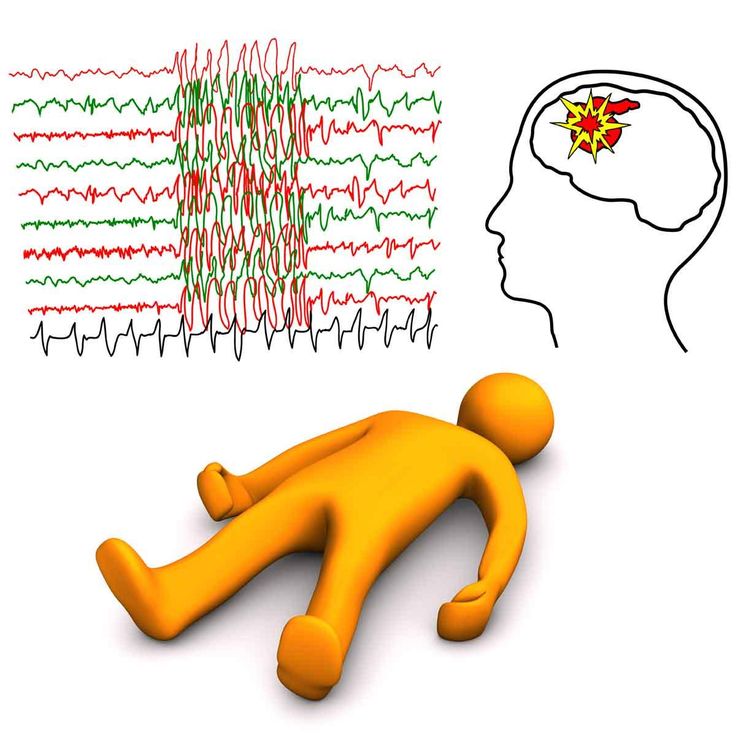

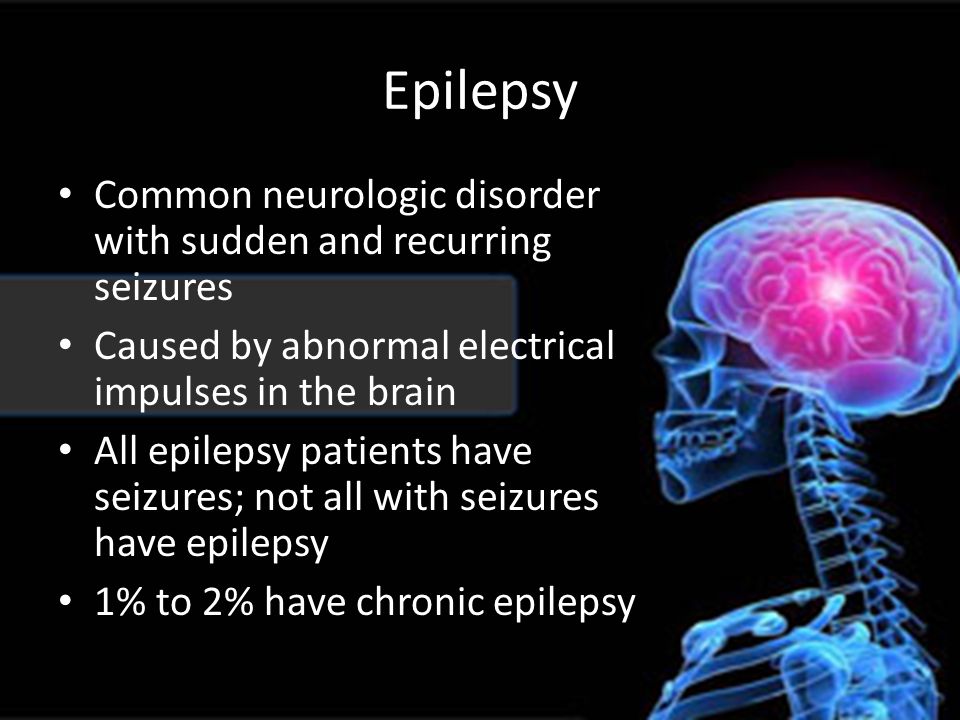

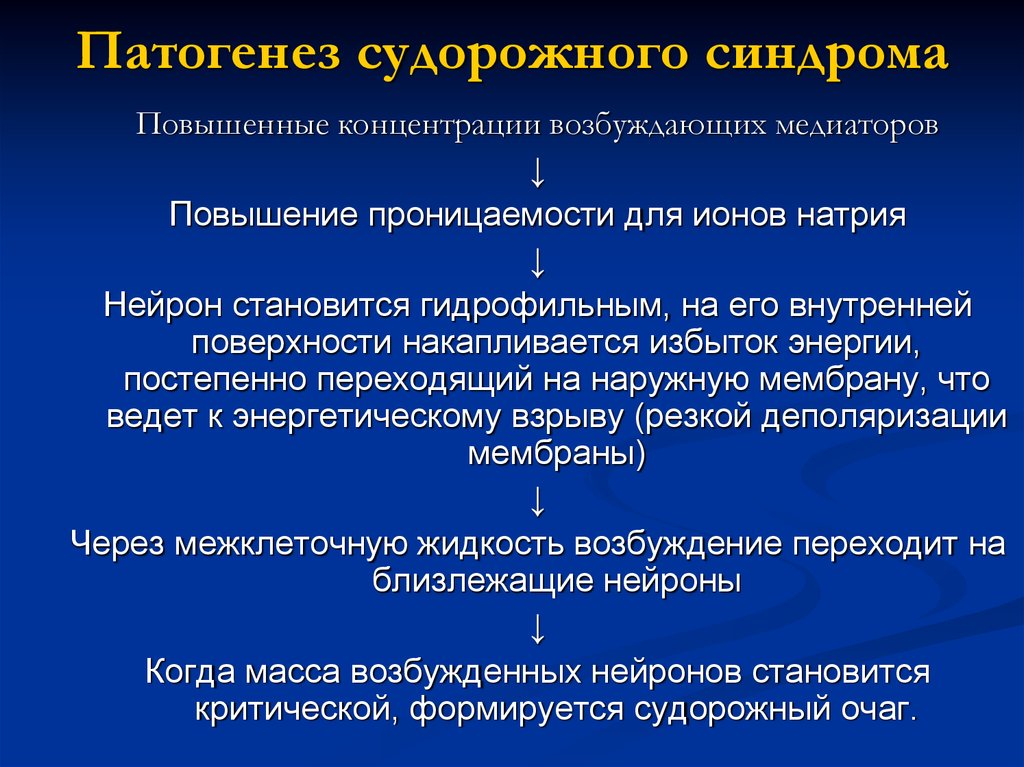

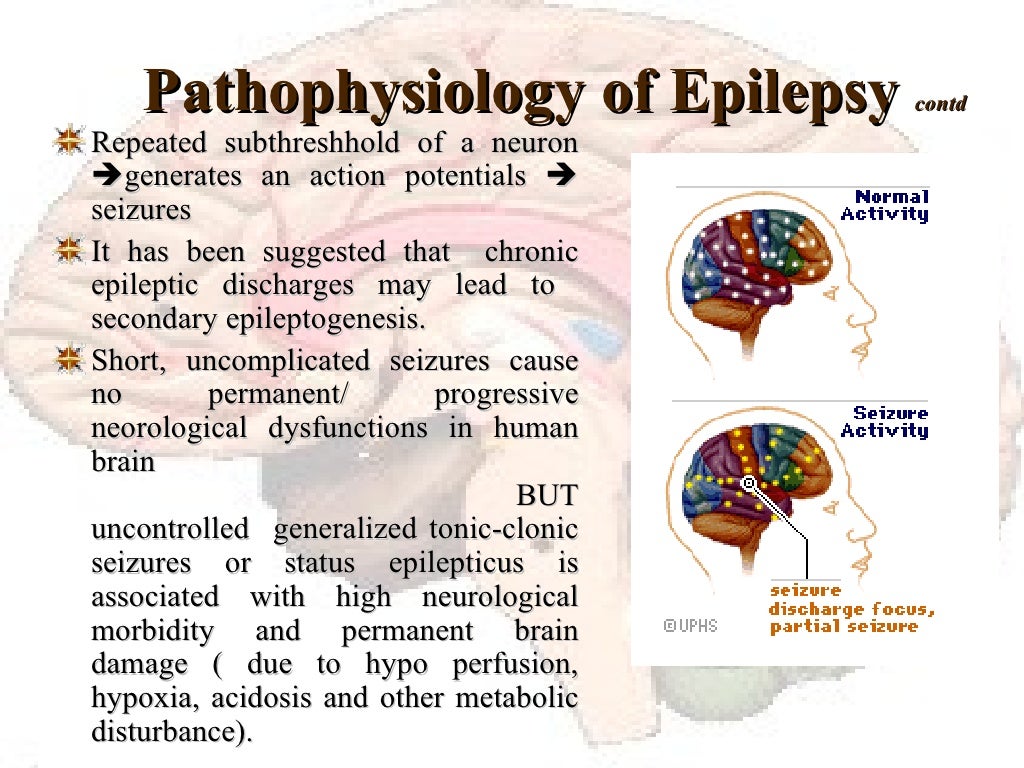

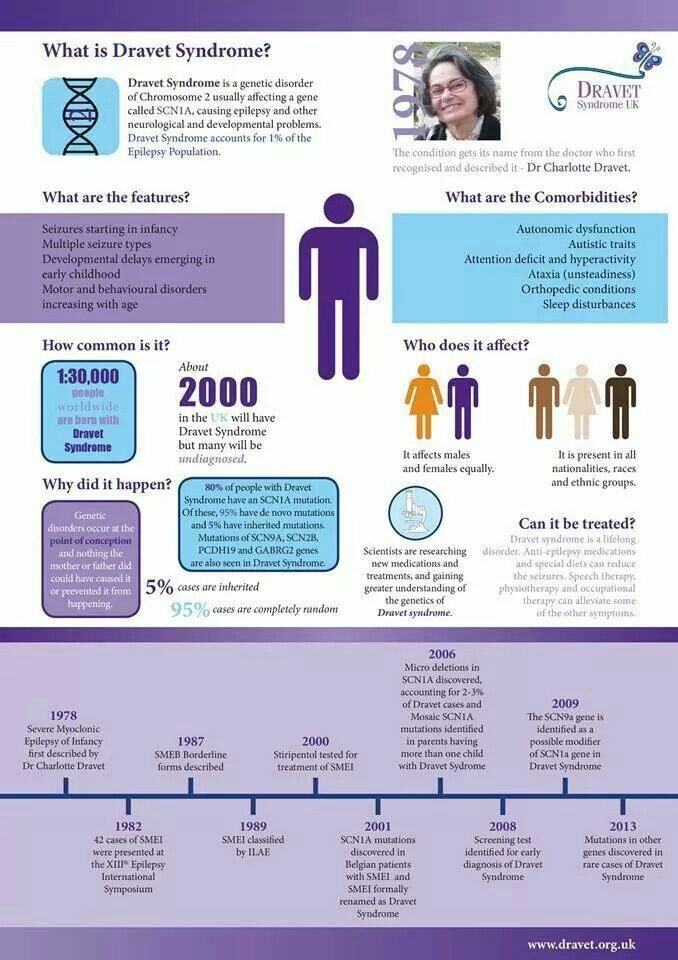

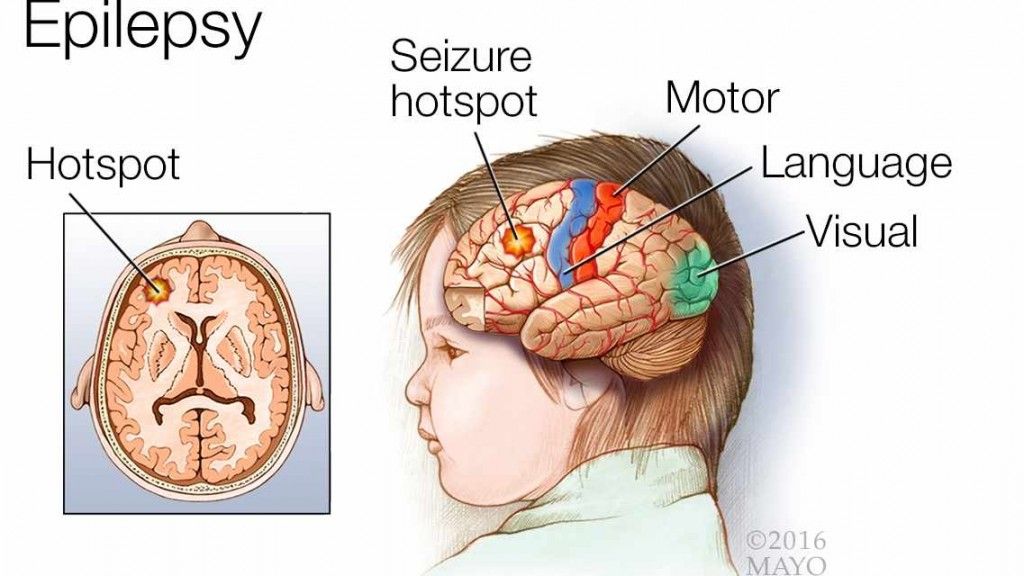

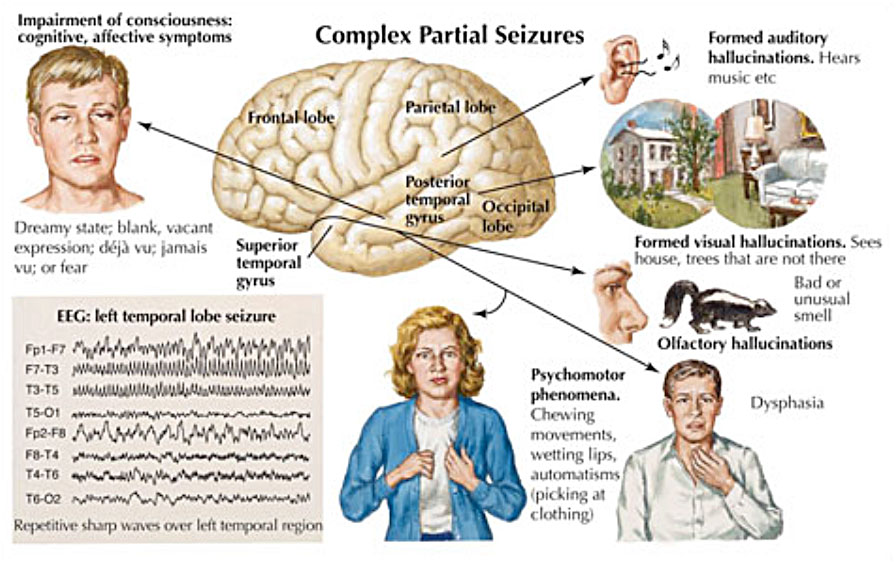

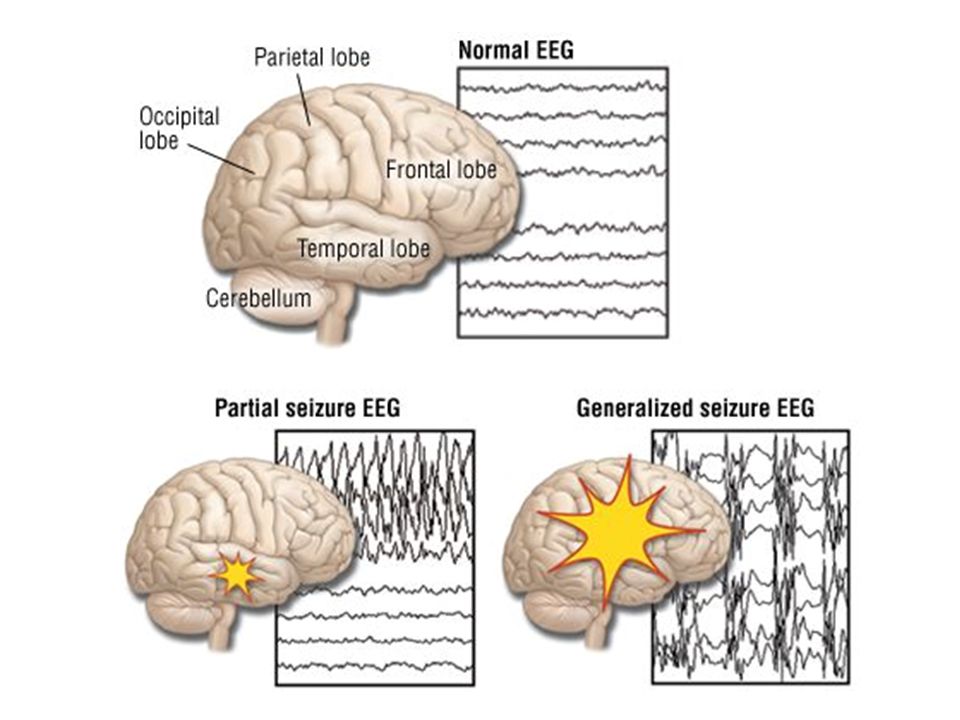

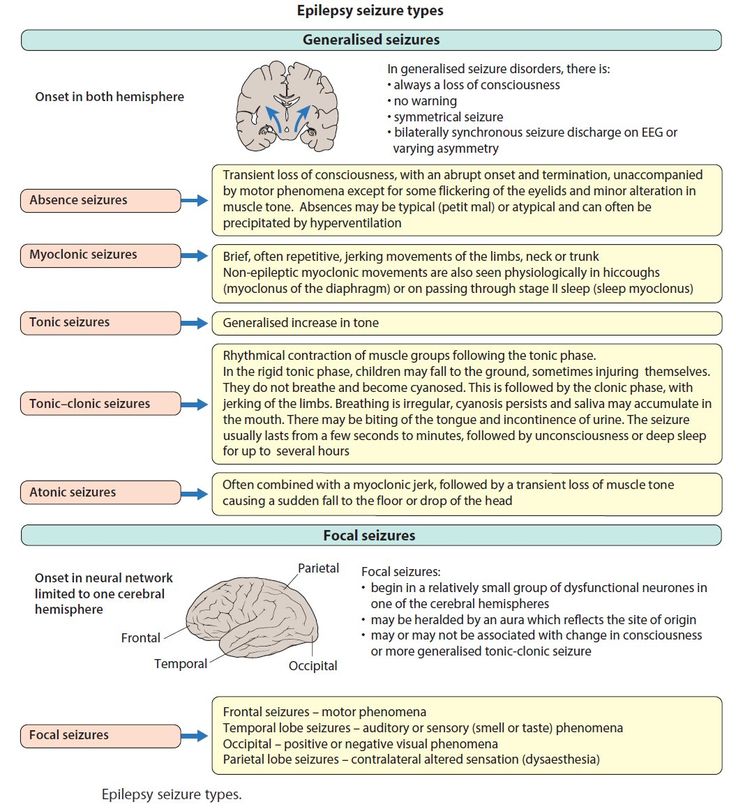

Around 1.2% of people in the United States live with epilepsy, a neurological condition that causes recurring seizures.

If you number among those 3.4 million people, you might be much more likely to have attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) than the general population.

Like epilepsy, ADHD affects your brain, though it doesn’t cause seizures. ADHD symptoms typically relate to your ability to concentrate and focus your attention, though you might also experience hyperactivity and impulsivity.

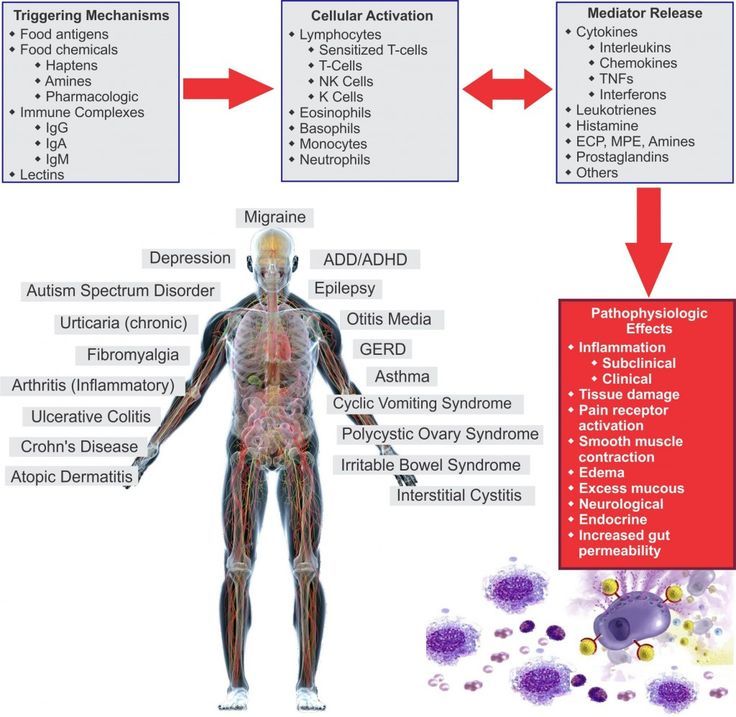

Experts have yet to determine exactly why these two conditions appear together so often, since neither condition directly causes the other. Rather, they seem to share biological roots.

Read on to learn more about the shared risk factors for ADHD and epilepsy, as well as how certain medications may have an impact on your symptoms.

FYI

ADHD, which affects 8.4% of kids and 2.5% of adults, is more common than epilepsy.

Because of this difference, most studies measure how many people with epilepsy also have ADHD, rather than the other way around.

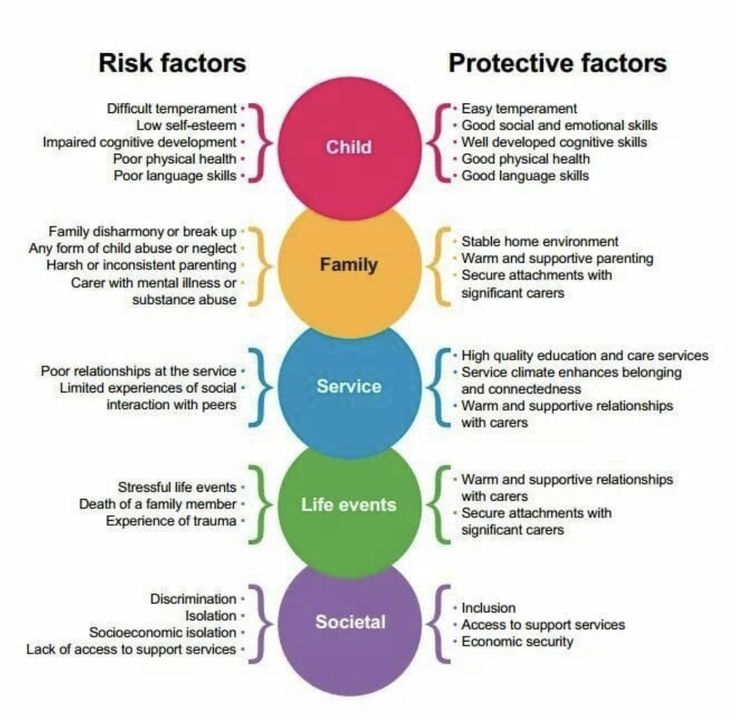

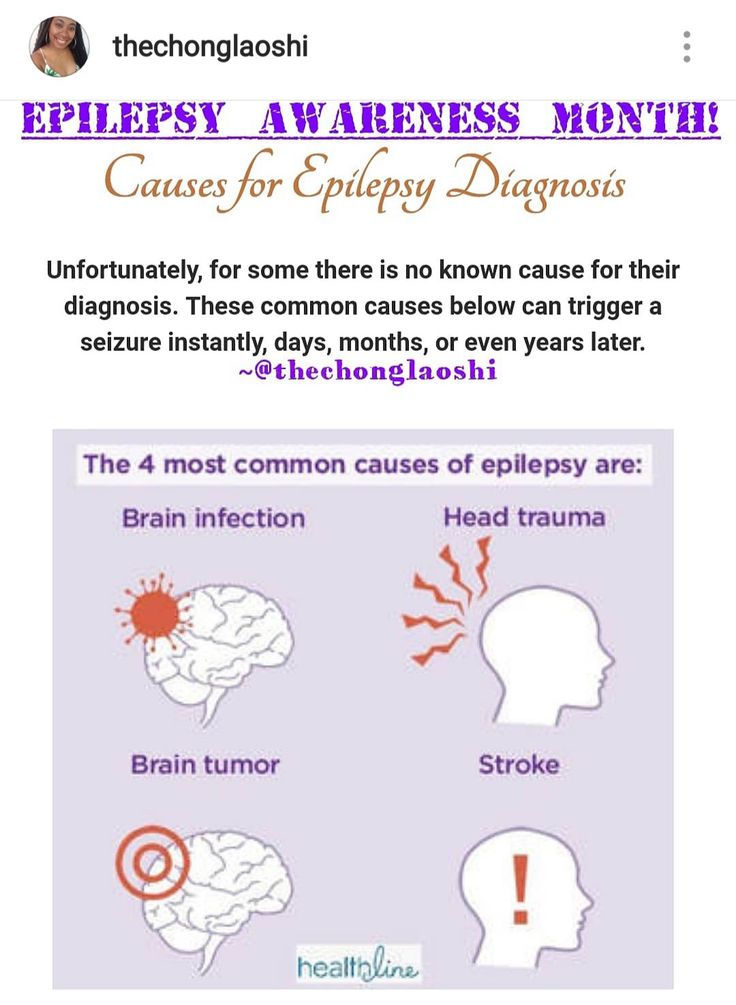

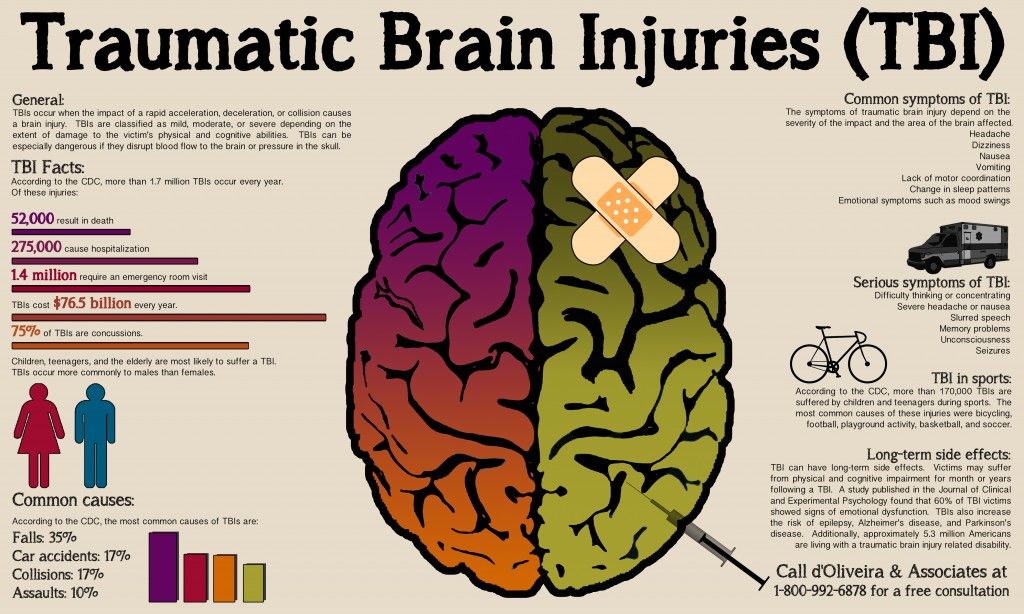

The same factors that cause epilepsy may also increase your chances of developing ADHD.

These include:

- genetics

- brain structure differences

- brain injury

- prenatal exposure to drugs or toxins, especially alcohol

If you have both epilepsy and ADHD, you may also have neurological differences that factor into certain ADHD symptoms:

- Less thalamus volume: One small 2012 study suggested that fewer nerve fibers coming out of the thalamus may lead to inattention symptoms.

- Less gray matter in the frontal lobe: The frontal lobe helps you make decisions. A small 2016 study linked less gray matter in this area to the inattentive subtype of ADHD.

- Less brain stem volume: If you have a smaller brain stem, you may have a harder time staying alert, according to a small 2014 study.

In adults vs. kids

Children with epilepsy tend to have much higher rates of co-occurring ADHD than adults with epilepsy. While up to 40% of children with epilepsy also have an ADHD diagnosis, only 13% to 18% of adults with epilepsy have an ADHD diagnosis.

Of course, some of this reported difference may relate to the fact that both epilepsy and ADHD are often diagnosed in young childhood.

The average age of onset for epilepsy is 3.7 years old, and the average age of onset for ADHD is 6 years old. As such, most screening for these conditions happens in childhood.

As an added complication, adult ADHD tends to be underdiagnosed. Symptoms like inattention and hyperactivity can be more subjective than seizures. So, you may get a diagnosis of epilepsy before an ADHD diagnosis, even if you have both conditions.

Does ADHD type make a difference?

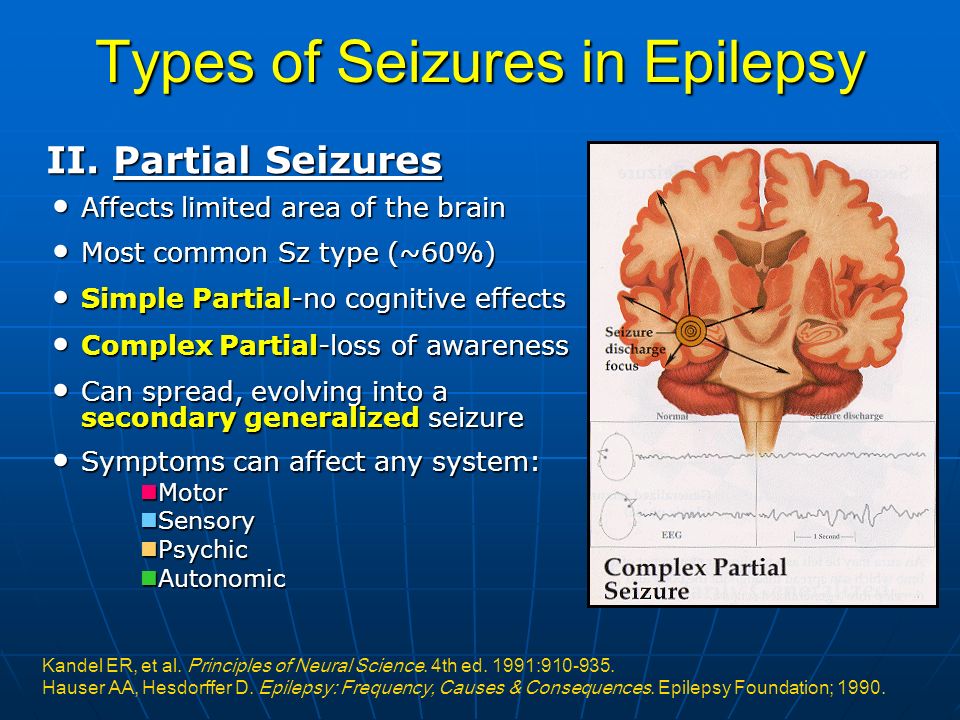

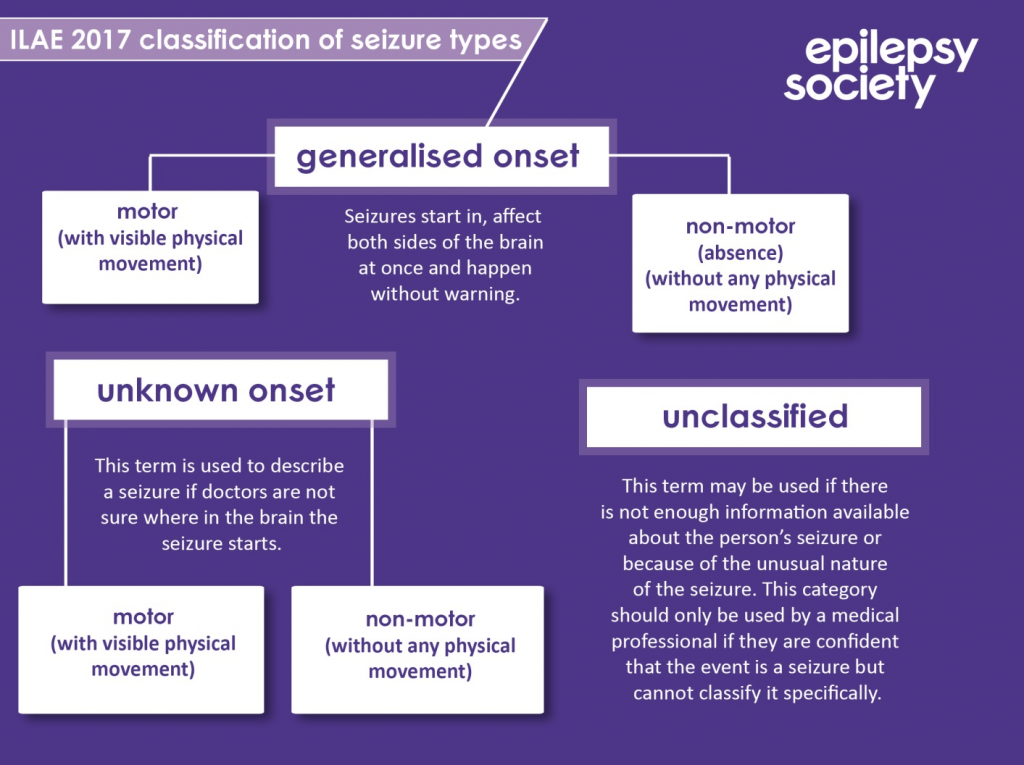

People with epilepsy may be more likely to have the inattentive type of ADHD. Inattentive type ADHD mostly involves symptoms that relate to attention and focus, so you may notice few, if any, hyperactivity symptoms.

It’s certainly possible to have epilepsy and combined type ADHD, though — and when these conditions occur together, they may involve more severe symptoms.

According to one 2007 study, children with both inattention and hyperactivity symptoms may be more likely to have:

- generalized seizures

- earlier symptom onset

- drug-resistant epilepsy

No evidence suggests epilepsy can cause ADHD, or vice versa. Yet, since the conditions often appear around the same time, it can certainly seem like one condition triggers the other.

Your family history plays a major role in whether you have both conditions. According to a 2017 study, if you have epilepsy, your chances of developing ADHD go up by:

- 56% if you have a sibling with epilepsy

- 64% if your father has epilepsy

- 85% if your mother has epilepsy

Having a family member with epilepsy or ADHD doesn’t guarantee you’ll develop either condition yourself. But if you have a family history of one or both conditions, paying attention to early signs of epilepsy and ADHD can help you get the right diagnosis and treatment sooner rather than later.

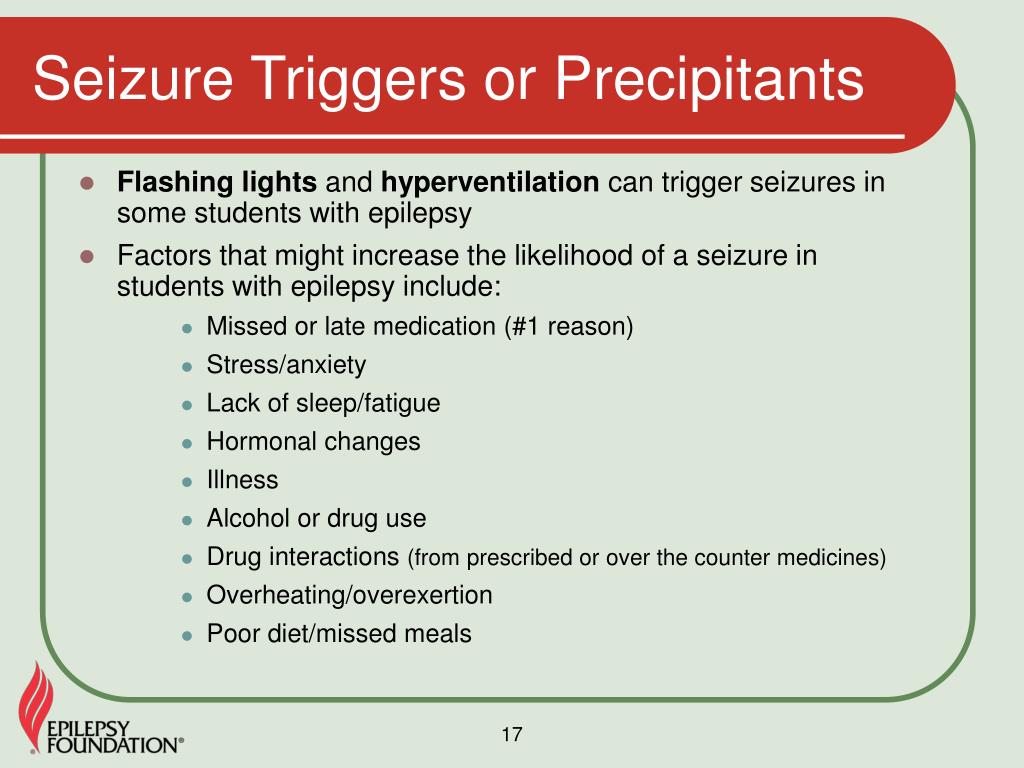

Your ADHD symptoms may worsen if you also have epilepsy.

Research from 2015 suggests epilepsy can make it difficult to sustain attention, especially if you have generalized seizures. You may also have trouble with short-term memory.

Having ADHD and epilepsy together can also be more difficult to manage than either condition alone. A study from 2015 compared adults with only epilepsy and adults with epilepsy and co-occurring ADHD symptoms. People with both conditions reported:

- a lower quality of life

- worse physical health

- more difficulties with social function

- a higher chance of being unable to work due to disability

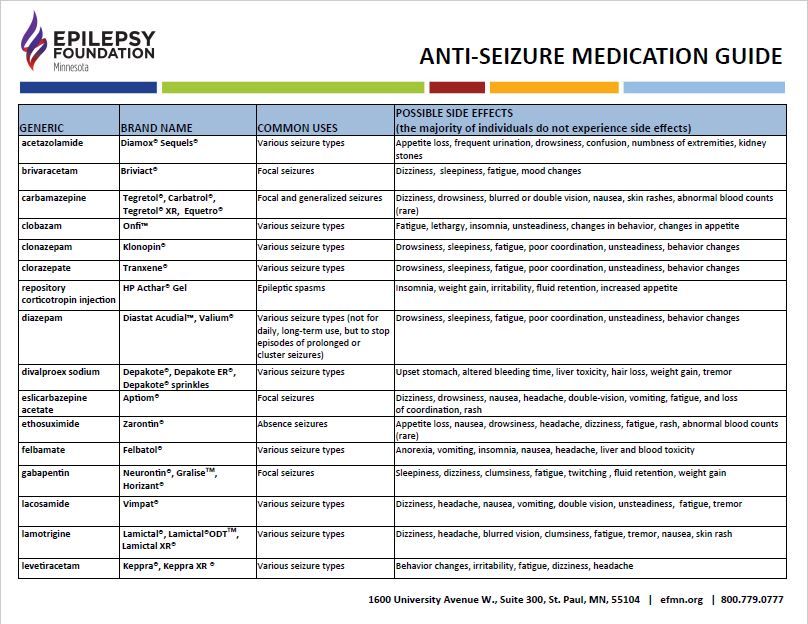

Medication often plays an essential role in both ADHD and epilepsy treatment. However, the medication for one condition may worsen symptoms of the other condition.

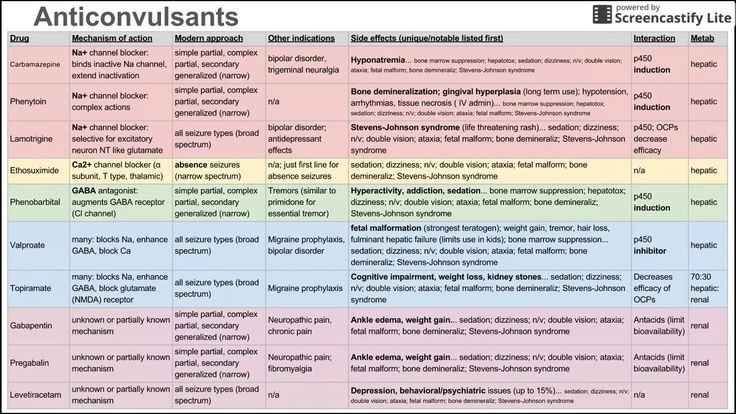

Can antiepileptic drugs worsen ADHD?

Some antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) cause side effects that resemble ADHD symptoms. They can also worsen existing ADHD symptoms, including:

- trouble focusing

- executive dysfunction, or difficulty with planning and managing impulses

- impaired short-term memory

- agitation or fidgeting

The AEDs most likely to exacerbate ADHD symptoms include:

- phenobarbital

- topiramate (Topamax)

- valproic acid

- phenytoin (Phenytek)

On the flip side, other AEDs may help improve ADHD symptoms. These medications include:

These medications include:

- carbamazepine (Carbatrol)

- lacosamide (Vimpat)

- lamotrigine (Lamictal)

Carbamazepine and lamotrigine may also help enhance attention.

Can ADHD medications worsen epilepsy?

The ADHD medication atomoxetine (Strattera) may worsen seizures for some people with epilepsy.

In a 2020 study involving 105 Korean children and adolescents with epilepsy and ADHD who took atomoxetine, about 8% said their seizures became more frequent or severe. One participant stopped taking atomoxetine as a result.

For the most part, though, ADHD medications appear safe for many people with epilepsy.

A large 2018 study examined hospitalization rates among children with epilepsy over a period of more than 10 years. Children who took stimulant medications were no more likely to be hospitalized for seizures than those who didn’t take stimulant medications. These findings held after researchers controlled for participant demographics and epilepsy type.

Could ADHD medication lower seizure risk?

In a 2019 Swedish study, researchers compared periods when participants did and didn’t take ADHD medication. When they took their medication, the risk of acute seizures dropped 27%.

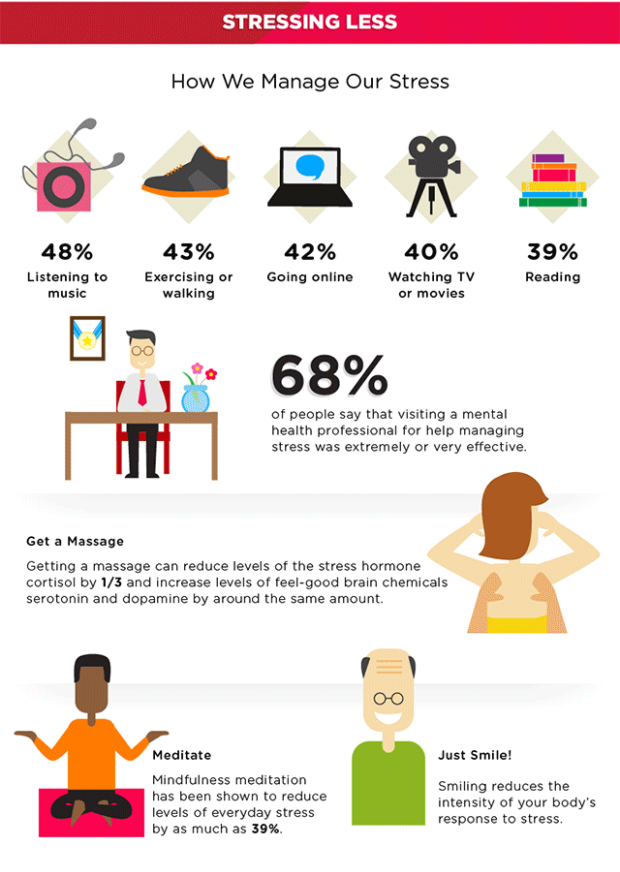

The researchers suggested treating ADHD symptoms may have helped participants remember to take their epilepsy medication. They also noted that improvements in ADHD symptoms may have helped ease stress and minimize alcohol use, both of which can prompt seizures.

It’s also possible that taking ADHD medication led to changes in the brain that helped reduce participants’ seizure risk.

If you live with both ADHD and epilepsy, finding the right treatment can go a long way toward helping you manage symptoms effectively.

Treatment for comorbid ADHD and epilepsy may involve medication, therapy, and occupational interventions.

Medication

Not much research has explored the most effective combinations of AEDs and ADHD medication. Your doctor will likely prescribe medication based on the type of ADHD and epilepsy you have.

Your doctor will likely prescribe medication based on the type of ADHD and epilepsy you have.

Always take your medications exactly as prescribed, since increasing or decreasing your dose on your own can have serious health consequences. If you experience uncomfortable side effects or worsened symptoms, your doctor or psychiatrist can adjust your dosages safely, with as little disruption to treatment as possible.

If you notice any change in your symptoms after starting a new medication, let your care team know right away so they can address it.

Psychotherapy

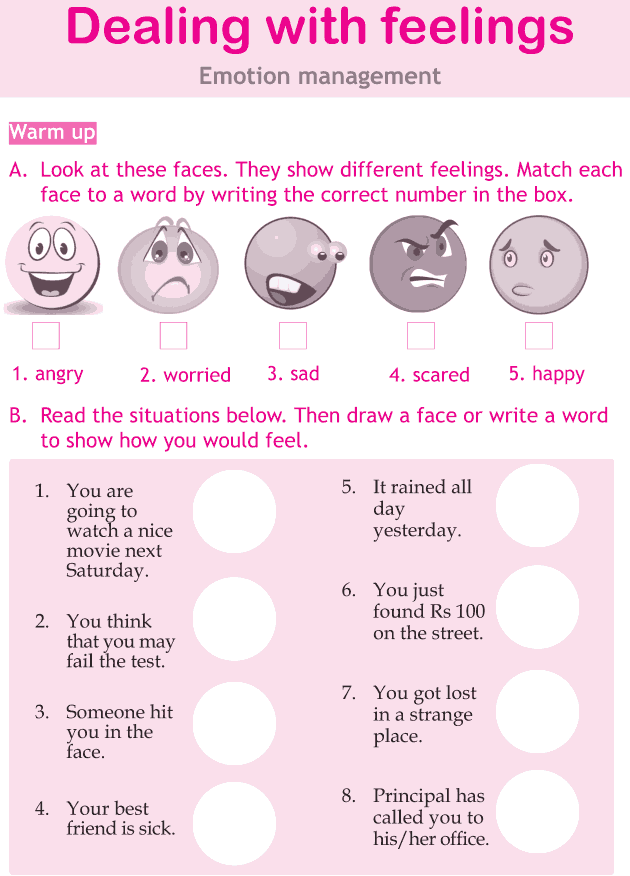

If you have both ADHD and epilepsy, therapy may help with some of your symptoms.

According to the International League Against Epilepsy Psychology Task Force, psychological interventions have the most benefit if you have:

- depression along with these conditions

- neurocognitive concerns, such as difficulty controlling impulses

- difficulty taking medication as prescribed

The specific type of therapy you find most helpful can depend on the issues you want help with. If behavioral concerns or seizures disrupt home or school life, family therapy could make a difference.

If behavioral concerns or seizures disrupt home or school life, family therapy could make a difference.

On the other hand, if you need help sticking with treatment or avoiding symptom triggers, you might consider:

- motivational interviewing

- cognitive behavioral therapy

- acceptance and commitment therapy

Learn more about treatment options for ADHD.

Occupational interventions

Children with both ADHD and epilepsy may need extra support in school. You can work with your child’s teachers to find the most effective accommodations for their specific needs.

Cooperating with your school becomes especially important if your child has a learning disability, such as dyslexia or dysgraphia.

According to the Learning Disabilities Association of America, almost 50% of people with epilepsy also have a learning disability. Among kids with ADHD, around 30% also have a learning disability.

As an adult with comorbid ADHD and epilepsy, you may be eligible for workplace accommodations. It’s also a good idea to let your co-workers know about potential seizure triggers, like flashing lights, to make your workplace as safe as possible for you.

It’s also a good idea to let your co-workers know about potential seizure triggers, like flashing lights, to make your workplace as safe as possible for you.

Many people with epilepsy also have ADHD, and having both conditions can have more of an impact on your daily life than either condition alone.

That said, getting professional treatment can make a big difference in your symptoms and your overall quality of life.

Finding the right treatment approach may involve some trial and error, since some medications designed to treat one set of symptoms can worsen other symptoms. Always inform your care team about any comfortable side effects or worsening symptoms, and talk with them before you stop taking your medication.

Emily Swaim is a freelance health writer and editor who specializes in psychology. She has a BA in English from Kenyon College and an MFA in writing from California College of the Arts. In 2021, she received her Board of Editors in Life Sciences (BELS) certification. You can find more of her work on GoodTherapy, Verywell, Investopedia, Vox, and Insider. Find her on Twitter and LinkedIn.

You can find more of her work on GoodTherapy, Verywell, Investopedia, Vox, and Insider. Find her on Twitter and LinkedIn.

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: comorbidities, focus on combination with epilepsy | Pylaeva

1. Bryazgunov I.P., Goncharova O.V., Kasatikova E.V. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children: a treatment protocol. Russian Pediatric Journal 2001;5:34–6.

2. Voronkova K.V., Petrukhin A.S. Impairments of cognitive functions in patients with epilepsy, the possibilities of prevention and correction: the current state of the problem. Effective pharmacology. 2011;4:46–51. nine0003

3. Zavadenko N.N., Simashkova N.V. New approaches to the diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakova 2014;114(1 issue 2): 45–51.

4. Zavadenko N.N., Solomasova A.A. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in combination with anxiety disorders: possibilities of pharmacotherapy. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakova 2012;112(8):44–8.

Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakova 2012;112(8):44–8.

5. Zenkov L.R., Konstantinov P.A., Shiryaeva I.Yu. Mental and behavioral disorders in idiopathic epileptiform focal discharges. Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S. S. Korsakova 2007; 107(6):39-49.

6. Zykov V.P., Begasheva O.I. Modern concepts of diagnosis and experience in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder with hopantenic acid. Pediatrics (Appendix to Consilium Medicum) 2017;1:114–8.

7. Zykov V.P., Kashirina E.S., Naugolnykh Yu.V. Methods of objective monitoring of the effectiveness of therapy in children with tics. Neurological Bulletin. Journal them. V.M. Bekhtereva 2016;2: 35–41.

8. Karlov V.A. Epilepsy in children and adult women and men. M.: Medicine, 2010. S. 543–562. nine0003

9. Muratova N.V. Pantocalcin®: clinical applications. Russian Medical Journal 2007;10:868.

10. Musatova N.M. Pantocalcin in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Difficult patient 2006;4(6):2–3.

Difficult patient 2006;4(6):2–3.

11. Mukhin K.Yu., Glukhova L.Yu., Bobylova M.Yu. etc. Epileptic syndromes. Diagnostics and therapy. 4th ed. M.: Binom, 2018. 607 p.

12. Pylaeva O.A., Mukhin K.Yu., Petrukhin A.S. Side effects of antiepileptic therapy. M.: Garnet, 2016. 232 p. [Pylaeva O.A., Mukhin K.Yu., Petrukhin A.S. Side effects of antiepileptic medication. Moscow: Granat, 2016. 232 p. (In Russ.)]. nine0003

13. Pylaeva O.A., Voronkova K.V., Petrukhin A.S. Efficacy and safety of antiepileptic therapy in children (comparative evaluation of valproic acid and barbiturates). Journal of Neurology and Psychiatry. S.S. Korsakova 2004;8:61–5.

14. Tumashenko A.F. The effectiveness of Pantocalcin in the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics (Appendix to Consilium Medicum) 2006;2:56–8.

15. Kholin AA, Ilyina Ye S. Combination of epilepsy with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (clinical examples). Bulletin of epileptology 2011;1:16–22. nine0003

Bulletin of epileptology 2011;1:16–22. nine0003

16. Aldenkamp A., Besag F., Gobbi G. et al. Psychiatric and behavioral disorders in children with epilepsy (ILAE Task Force Report): adverse and behavioral effects of cognitive antiepileptic drugs in children. Epileptic Disord 2016. PMID: 27184878. DOI: 10.1684/epd.2016.0817.

17. Aldenkamp A.P., Arzimanoglou A., Reijs R., van Mil S. Optimizing therapy of seizures in children and adolescents with ADHD. Neurology 2006;67(12 Suppl 4):49–51. PMID: 17190923.

18. Altunel A., Sever A., Altunel E.Ö. ACTH has beneficial effects on stuttering in ADHD and ASD patients with ESES: A retrospective study. Brain Dev 2017;39(2):130–7. PMID: 27645286. DOI: 10.1016/j.braindev.2016.09.001.

19. American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders DSM-5. 5th edn. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2013.

20. Barabas G., Matthews W. S. Barbiturate anticonvulsants as a cause of severe depression. Pediatrics 1988;82:284–5. PMID: 3399308.

Pediatrics 1988;82:284–5. PMID: 3399308.

21. Barkley R.A. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Sci Am 1998;279(3):66–71. PMID: 9725940.

22. Becker K., Sinzig J.K., Holtmann M. Attention deficits and subclinical epileptiform discharges: are EEG diagnostics in ADHD optional or essential? Dev Med Child Neurol 2004;46(6):431–2. PMID: 15174538.

23. Ben-Ari Y. GABA excites and sculpts immature neurons well before delivery: modulation by GABA of the development of ventricular progenitor cells. Epilepsy Curr 2007;7(6):167–9. DOI: 10.1111/j.1535-7511.2007.00214.x.

24. Bertelsen E.N., Larsen J.T., Petersen L. et al. Epilepsy, febrile seizures, and subsequent risk of ADHD. Pediatrics 2016;138(2). PII: e20154654. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2015-4654. nine0003

25. Besag F., Gobbi G., Caplan R. et al. Psychiatric and behavioral disorders in children with epilepsy (ILAE Task Force Report): epilepsy and ADHD. Epileptic Disord 2016. PMID: 27210536.

26. Brown R. T., Freeman W.S., Perrin J.M. et al. Prevalence and assessment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in primary care settings. Pediatrics 2001;107(3):E43.

T., Freeman W.S., Perrin J.M. et al. Prevalence and assessment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in primary care settings. Pediatrics 2001;107(3):E43.

27. Caplan R. ADHD in pediatric epilepsy: fact or fiction? Epilepsy Curr 2017;17(2):93–5. DOI: 10.5698/15357511.17.2.93.

28. Caplan R., Siddarth P., Stahl L. et al. Childhood absence epilepsy: Behavioral, cognitive, and linguistic comorbidities. Epilepsia 2008;49(11):1838–46. PMID: 18557780. DOI: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2008.01680.x.

29. Cardenas J.F., Rho J.M., Ng Y.T. Reversible lamotrigine-induced neurobehavioral disturbances in children with epilepsy. J Child Neurol 2010;25:182–7.

30. Chadwick D., Marson T. Choosing a first drug treatment for epilepsy after SANAD: randomized controlled trials, systematic reviews, guidelines and treating patients. Epilepsia 2007;48(7):1259-63. PMID: 17442006. DOI: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01086.x.

31. Cramer J.A., Hammer A.E., Kustra R.P. Improved mood states with lamotrigine in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2004;5(5):702–7. PMID: 15380122. DOI: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.07.005.

Epilepsy Behav 2004;5(5):702–7. PMID: 15380122. DOI: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.07.005.

32. D’Agati E., Moavero R., Cerminara C., Curatolo P. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and tuberous sclerosis complex. J Child Neurol 2009;24(10):1282–7.

33. Davis S.M., Katusic S.K., Barbaresi W.J. et al. Epilepsy in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr Neurol 2010;42(5):325–30. PMID: 20399385. DOI: 10.1016/j.pediatr-neurol.2010.01.005.

34. De Vries P.J., Gardiner J., Bolton P.F. Neuropsychological attention deficits in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). Am J Med Genet A 2009;149A(3):387–95. PMID: 19215038. DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32690.

35. Depositario-Cabacar D.F., Zelleke T.G. Treatment of epilepsy in children with developmental disabilities. Dev Disabil Res Rev 2010;16(3):239–47. PMID: 20981762. DOI: 10.1002/ddrr.116.

36. Duane D.D. Increased frequency of rolandic spikes in ADHD children. Epilepsia 2004;45(5):564–5. PMID: 15101844. DOI: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.t01-4-62803.x.

DOI: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2004.t01-4-62803.x.

37. Dunn D.W., Austin J.K., Harezlak J., Ambrosius W.T. ADHD and epilepsy in childhood. Dev Med Child Neurol 2003;45(1):50–4. PMID: 12549755.

38. Dunn D.W., Kronenberger W.G. Childhood epilepsy, attention problems, and ADHD: review and practical considerations. Semin Pediatr Neurol 2005;12(4):222–8.

39. Dussaule C., Bouilleret V. Psychiatric effects of antiepileptic drugs in adults. Geriatr Psychol Neuropsychiatr Vieil 2018;16(2):181–8. DOI: 10.1684/pnv.2018.0733. nine0003

40. Fernandez-Mayoralas D.M., FernándezJaén A., Muñoz-Jareño N. et al. Effectiveness of levetiracetam in a patient with chronic motor tics, Rolandic epilepsy and attentional and behavioral disorder. Rev Neurol 2009;49(9):502–3.

41. Gertrude H. ADHD as a risk factor for incident unprovoked seizures and epilepsy in children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61(7):731–6.

42. Glauser T.A., Cnaan A., Shinnar S. et al. Ethosuximide, valproic acid, and lamotrigine in childhood absence epilepsy. N Engl J Med 2010:362;790–9.

N Engl J Med 2010:362;790–9.

43. Gonzalez-Heydrich J., Dodds A., Whitney J. et al. Psychiatric disorders and behavioral characteristics of pediatric patients with both epilepsy and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Epilepsy Behav 2007;10(3):384–8.

44. Hamoda H.M., Guild D.J., Gumlak S. et al. Association between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and epilepsy in pediatric populations. Expert Rev Neurother 2009;9(12):1747–54.

45. Hechtman L., Weiss G. Long-term outcome of hyperactive children. Am J Orthopsychiatry 1983;53(3):532–41.

46. Heil S.H., Holmes H.W., Bickel W.K. et al. Comparison of the subjective, physiological, and psychomotor effects of atomoxetine and methylphenidate in light drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend 2002;67(2):149–56.

47. Hemmer S.A., Pasternak J.F., Zecker S.G., Trommer B.L. Stimulant therapy and seizure risk in children with ADHD. Pediatr Neurol 2001;24(2): 99–102.

48. Hermann B., Jones J., Dabbs K. et al. The frequency, complications and aetiology of ADHD in new onset pediatric epilepsy. Brain 2007;130(Pt 12):3135–48. nine0003

et al. The frequency, complications and aetiology of ADHD in new onset pediatric epilepsy. Brain 2007;130(Pt 12):3135–48. nine0003

49. Hesdorffer D.C., Ludvigsson P., Olafsson E. et al. ADHD as a risk factor for incident unprovoked seizures and epilepsy in children. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61(7):731–6.

50. Ibekwe R.C., Chidi N.A., Ebele A.A., Chinyelu O.N. Comorbidity of attention deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and epilepsy in children seen In University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital Enugu: prevalence, clinical and social correlates. Niger Postgrad Med J 2014;21(4):273–8.

51. Inaba Y., Seki C., Ogiwara Y. et al. Supplementary motor area epilepsy associated with ADHD in an abused history. No To Hattatsu 2000;32(5):435–9.

52. Kaminow L., Schimschock J.R., Hammer A.E., Vuong A. Lamotrigine monotherapy compared with carbamazepine, phenytoin, or valproate monotherapy in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2003;4(6):659–66.

53. Kang S.H., Yum M. S., Kim E.H. et al. Cognitive function in childhood epilepsy: importance of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Neurol 2015;11(1): 20–5. DOI: 10.3988/jcn.2015.11.1.20.

S., Kim E.H. et al. Cognitive function in childhood epilepsy: importance of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Neurol 2015;11(1): 20–5. DOI: 10.3988/jcn.2015.11.1.20.

54. Kanner A.M. The use of psychotropic drugs in epilepsy: what every neurologist should know. Semin Neurol 2008;28(3):379-88.

55. Kartal A., Aksoy E., Deda G. The effects of risk factors on EEG and seizure in children with ADHD. Acta Neurol Belg 2017;117(1):169–73.

56. Kaufmann R., Goldberg-Stern H., Shuper A. Attention-deficit disorders and epilepsy in childhood: incidence, causative relations and treatment possibilities. J Child Neurol 2009;24(6):727–33.

57. Kinney R.O., Shaywitz B.A., Shaywitz S.E. et al. Epilepsy in children with attention deficit disorder: cognitive, behavioral, and neuroanatomical indices. Pediatric Neurol 1990;6(1):31–7.

58. Koneski J.A., Casella E.B. Attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder in people with epilepsy: diagnosis and implications to the treatment. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2010;68(1):107–14.

Arq Neuropsiquiatr 2010;68(1):107–14.

59. Kral M.C., Lally M.D., Boan A.D. Identification of ADHD in youth with epilepsy. J Pediatr Rehabil Med 2016;9(3):223–9.

60. Kwan P., Brodie M.J. Neuropsychological effects of epilepsy and antiepileptic drugs. Lancet 2001;357(9251):216–22.

61. Laporte N., Sebire G., Gillerot Y. et al. Cognitive epilepsy: ADHD related to focal EEG discharges. Pediatr Neurol 2002;27(4):307–11. nine0003

62. Lehmkuhl G., Sevecke K., Frohlich J., Dopfner M. Child is inattentive, cannot sit still, disturbs the classroom. Is it really a hyperkinetic disorder? MMW Fortschr Med 2002;144(47):26–31.

63. Liu S.T., Tsai F.J., Lee W.T. et al. Attentional processes and ADHD-related symptoms in pediatric patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res 2011;93(1):53–65.

64. Marson A.G., Al-Kharusi A.M., Alwaidh M. et al. The SANAD study of effectiveness of carbamazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, oxcarbazepine, or topiramate for treatment of partial epilepsy: an unblinded randomized controlled trial. Lancet 2007;369(9566):1000–15.

Lancet 2007;369(9566):1000–15.

65. Moavero R., Santarone M.E., Galasso C., Curatolo P. Cognitive and behavioral effects of new antiepileptic drugs in pediatric epilepsy. Brain Dev 2017;39(6):464–9. DOI: 10.1016/j.braindev.2017.01.006.

66. Mula M., Sander J.W. Negative effects of antiepileptic drugs on mood in patients with epilepsy. Drug Saf 2007;30(7): 555–67.

67. Mulas F., Tellez de Meneses M., Hernandez-Muela S. et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and epilepsy. Rev Neurol 2004;39(2):192–5.

68. Neto F.K., Noschang R., Nunes M.L. The relationship between epilepsy, sleep disorders, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in children: A review of the literature. SleepSci 2016;9(3): 158–63.

69. Ott D., Caplan R., Guthrie D. et al. Measures of psychopathology in children with complex partial seizures and primary generalized epilepsy with absence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2001;40:907–14.

70. Ottman R., Lipton R. B., Ettinger A.B. et al. Comorbidities of epilepsy: Results from the Epilepsy Comorbidities and Health (EPIC) Survey. Epilepsia 2011;52(2):308–15. DOI: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02927.x.

B., Ettinger A.B. et al. Comorbidities of epilepsy: Results from the Epilepsy Comorbidities and Health (EPIC) Survey. Epilepsia 2011;52(2):308–15. DOI: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02927.x.

71. Parisi P., Moavero R., Verrotti A., Curatolo P. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children with epilepsy. Brain Dev 2010;32(1):10–6. PMID: 19369016. DOI: 10.1016/j.braindev.2009.03.005.

72. Pearl P.L., Weiss R.E., Stein M.A. medical mimics. Medical and neurological conditions simulating ADHD. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2001;931:97–112. PMID: 11462759.

73. Powell A.L., Yudd A., Zee P., Mandelbaum D.E. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder associated with orbitofrontal epilepsy in a father and a son. Neuropsychiatry Neuropsychol Behav Neurol 1997;10(2):151–4.

74. Rasmussen N.H., Hansen L.K., Sahlholdt L. Comorbidity in children with epilepsy. I: Behavior problems, ADHD and intelligence. Ugeskr Laeger 2007;169(19): 1767–70. PMID: 17537348.

75. Rugino T.A., Samsock T. C. Levetiracetam in autistic children: an open-label study. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2002;23(4):225–30.

C. Levetiracetam in autistic children: an open-label study. J Dev Behav Pediatr 2002;23(4):225–30.

76. Schubert R. Attention deficit disorder and epilepsy. Pediatr Neurol 2005;32(1):1–10.

77. Seidenberg M., Pulsipher D.T., Hermann B. Association of epilepsy and comorbid conditions. Future Neurol 2009;4(5):663–8. PMID: 20161538. DOI: 10.2217/fnl.09.32.

78. Semrud-Clikeman M., Wical B. Components of attention in children with complex partial seizures with and without ADHD. Epilepsia 1999;40(2):211–5. PMID: 9952269.

79. Sherman E.M., Slick D.J., Connolly M.B., Eyrl K.L. ADHD, neurological correlates and health-related quality of life in severe pediatric epilepsy. Epilepsia 2007;48(6):1083–91. PMID: 17381442. DOI: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2007.01028.x.

80. Sinclair D.B., Unwala H. Absence epilepsy in childhood: electroencephalography (EEG) does not predict outcome. J Child Neurol 2007;22(7):799–802. PMID: 17715268. DOI: 10.1177/0883073807304198.

81. Sinzig J.K., von Gontard A. Absences as differential diagnosis in children with attention-deficit disorder. Klin Padiatr 2005;217(4):230–3. PMID: 16032549. DOI: 10.1055/s-2004-820328.

Sinzig J.K., von Gontard A. Absences as differential diagnosis in children with attention-deficit disorder. Klin Padiatr 2005;217(4):230–3. PMID: 16032549. DOI: 10.1055/s-2004-820328.

82. Socanski D., Herigstad A., Thomsen P.H. et al. Epileptiform abnormalities in children diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Epilepsy Behav 2010;19(3):483–6. PMID: 20869322. DOI: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.08.005.

83. Torres A., Whitney J., Rao S. et al. Tolerability of atomoxetine for treatment of pediatric attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the context of epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2011;20(1):95–102. PMID: 21146461. DOI: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.11.002.

84. Torres A.R., Whitney J., Gonzalez-Heydrich J. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in pediatric patients with epilepsy: review of pharmacological treatment. Epilepsy Behav 2008;12(2):217–33. PMID: 18065271. DOI: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.08.001. nine0003

85. Van der Feltz-Cornelis C.M., Aldenkamp A.P. Effectiveness and safety of methylphenidate in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in patients with epilepsy: an open treatment trial. Epilepsy Behav 2006;8(3):659–62. PMID: 16504592. DOI: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.01.015.

Epilepsy Behav 2006;8(3):659–62. PMID: 16504592. DOI: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.01.015.

86. Vega C., Vestal M., DeSalvo M. et al. Differentiation of attention-related problems in childhood absence epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav 2010;19(1):82–5.

87. Weinstock A., Giglio P., Kerr S.L. et al. Hyperkinetic seizures in children. J Child Neurol 2003;18(8):517–24. PMID: 13677576. DOI: 10.1177/08830738030180080801. nine0003

88. Wernicke J.F., Holdridge K.C., Jin L. et al. Seizure risk in patients with attention-deficit-hyperactivity disorder treated with atomoxetine. Dev Med Child Neurol 2007;49(7):498–502. PMID: 17593120. DOI: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00498.x.

89. Williams A.E., Giust J.M., Kronenberger W.G., Dunn D.W. Epilepsy and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: links, risks, and challenges. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2016;12:287–96. DOI: 10.2147/NDT.S81549.

90. Wisniewska B., Baranowska W., Wendorff J. The assessment of comorbid disorders in ADHD children and adolescents. Adv Med Sci 2007;52 (Suppl 1):215–7. PMID: 18229669.

Adv Med Sci 2007;52 (Suppl 1):215–7. PMID: 18229669.

91. Young J. Common comorbidities seen in adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Adolesc Med State Art Rev 2008;19(2):216–28.

92. Zhang Z., Lu G., Zhong Y. et al. Impaired attention network in temporal lobe epilepsy: a resting FMRI study. Neurosci Lett 2009;458(3):97–101. PMID: 19393717. DOI: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.04.040.

My son (3.5 years old) has ADHD, VSD, ADHD, epilepsy. Do you take children with such diagnoses?

Elena, 3.5 years:

Hello! My son is 3.5 years old, he is being observed by a neurologist - ZRR, VSD, ADHD, and other concomitant developmental disorders. MRI - reversible effects of hypoxia. The doctor didn't find anything wrong. But! There were 4 seizures in a dream, they put epilepsy - a benign idiopathic form. EEG is normal. Taking an anticonvulsant for 2.5 years, remission - 2 years. The problem is that the child does not sleep well - screams, moans. During the day, mood swings, aggression, restlessness, negativism and other delights. Do you take children with such diagnoses, you are especially interested in the question, will there be consequences for epilepsy? nine0003

During the day, mood swings, aggression, restlessness, negativism and other delights. Do you take children with such diagnoses, you are especially interested in the question, will there be consequences for epilepsy? nine0003

Hello Elena.

Your "special" child can and should be consulted by an osteopath. A personal examination will reveal the cause of all neurological disorders. Judging by your description, there is no reason to worry about complications. The experience of treating children with similar problems by the specialists of our clinic allows us to assert that we can effectively help you.

Best regards,

Yashchina Olga Vladimirovna

Head doctor of the clinic "Ostmed"

- All doctor's answers - Yashchina Olga Vladimirovna

- All questions related to Speech Delay (SLD) and Developmental Retardation (DDD)

- Diseases and complaints:

OSTEOPATHY FOR EVERYONE Osteopathy Osteopathy for children Osteopathy in gynecology Osteopathy for pregnant women Osteopathy in dentistry Osteopathic lymphatic drainage Aesthetic osteopathy Osteopathy in psychosomatics Osteopathy in trauma nine0003 Fill out the questionnaire -

help us become better!

Name and Surname

Telephone

All news

Dmitry, 06. .06..2018

.06..2018

Hello! For more than 10 years I have been suffering from back pain.

Hello! You can reduce them. It is necessary to relax the back muscles using osteopathic techniques. By doing this, we achieve an improvement in blood supply, a decrease in soft tissue edema and an improvement in venous outflow, which leads to a decrease in the volume of the hernia and the disappearance of pain. To do this, you need to make an appointment with a doctor and bring MRI images. nine0003

Full answer

All questions and answers

Our specialistsMICHEL DOBENSKY Doctor of osteopathy.

Director of the Israel College of Osteopathic Medicine and Naturopathy.

International teacher of osteopathy and international lecturer, organizer and participant of scientific and medical symposiums and seminars.

Member of the Medical Expert Council of the Ostmed Clinic.

Learn more

JEAN FANCELLO Master of European Osteopathy

Outstanding doctor, one of the best osteopaths and kinesiotherapists in France

Leading teacher of the Higher Osteopathic School of Classical Pediatrics in Toulouse.

Member of the State Commission of the French Ministry of Health for educational activities in the field of osteopathic medicine.

Member of the regional state expert-licensing commission for professional attestation of osteopaths. nine0003

Since 2006 he has been President of the National Osteopathic Union of France.

Learn more

IOULIA DESARNAUD Doctor of Osteopathy of Europe (DOE).

French certified osteopath, specialist in pediatric and perinatal osteopathy.

Learn more

Lysenko Sofia Viktorovna osteopath, neurologist, pediatrician, chiropractor

Member of the Russian Osteopathic Association

Learn more

Aleksandrova Inna Evgenievna osteopath, dentist

Member of the Russian Osteopathic Association.

Learn more

Plotnikov Kirill Alexandrovich specialist in medical and aesthetic massage

Massage practice – 5 years.

Learn more

Litvinov Igor Anatolyevich Osteopath, neurologist, chiropractor, kinesiologist, homeopath

Osteopath, neurologist, chiropractor, kinesiologist, homeopath.

Member of the Russian Osteopathic Association.

Director of the first in Russia Private School of Postgraduate Osteopathic Education - "PILOT"

Member of the Board and Chairman of the Moscow branch of the Russian Register of Osteopaths (RRDO).

Learn more

Zharkova Alesya Aleksandrovna chiropractor, podiatrist

Manual therapist who uses osteopathic techniques, podiatrist. nine0003

Learn more

Vladimir Alexandrovich Frolov osteopath, neurologist, reflexologist, chiropractor, posturologist and podiatrist

Vladimir Alexandrovich Frolov – osteopath, neurologist, reflexologist, manual therapist, posturologist and podiatrist.

Doctor of Medicine.

Professor of the First Moscow State Medical University. THEM. Sechenov.

Academician of the Russian Academy of Natural Sciences, Academician of the Academy of Technical Sciences of the Russian Federation, full member of the National Academy of Active Longevity. nine0003

Member of the Russian Osteopathic Association.

Learn more

Ploshnitsa Maria Alekseevna Osteopath, neurologist, kinesiologist.

Member of the Russian Osteopathic Association.

Learn more

Sherstenikina Natalya Sergeevna Psychotherapist, osteopath

Member of the Russian Osteopathic Association.

Learn more

Yashchina Olga Vladimirovna Chief doctor of the clinic "Ostmed"

Osteopathic doctor, therapist, doctor of rehabilitation medicine.

Member of the Russian Osteopathic Association.

Member of the Medical Expert Council.

Director of the Foundation for the Promotion of Osteopathy.

Learn more

Urvantsev Daniil Alexandrovich Manual Therapist Experience - 3 years.

Learn more than

Nepalo Irina Evgenievna Doctor Homeop-therapist

Practice in homeopathy since 2007.

Learn more than

Grebennikova Elena Vladimirovna, 200221 Doctor Osteopatiy 9000 9000 9000 9000 in Osteopati Learn more Loshkareva Larisa Spartakovna Osteopath, surgeon, resuscitator, anesthesiologist, gerontologist Candidate of Medical Sciences. nine0003 Member of the Russian Osteopathic Association. Learn more Sergeeva Liliya Alexandrovna Osteopath, obstetrician-gynecologist, neurologist, reflexologist Member of the Russian Osteopathic Association. Learn more Elena writes: Before the treatment, my daughter could not walk normally! I would like to express my deep gratitude to the clinic Ostmed and Yashchina Olga Vladimirovna, as well as Akopyan Marianna Sergeevna. I take my daughter thereyears) for a year already - I was worried about constant pain in my legs, high fatigue, low endurance. They made special insoles, treatment is being carried out, and the result is noticeable - the daughter can walk for a long time without pain, her general health has also noticeably increased (and excess weight has decreased). But before the start of treatment, my daughter could not walk normally! Now I'm being treated by Olga Vladimirovna and I'm treating my back myself, they made special insoles, I'm going through a massage course. I started recently, but already the result is visible throughout the body. I am grateful to Ostmed from the bottom of my heart, we will continue to go there with the whole family.

Reviews