Zinc for anxiety

How it Helps Anxiety and Depression I Psych Central

Zinc is an essential nutrient that has many health benefits, including helping to reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression for some people.

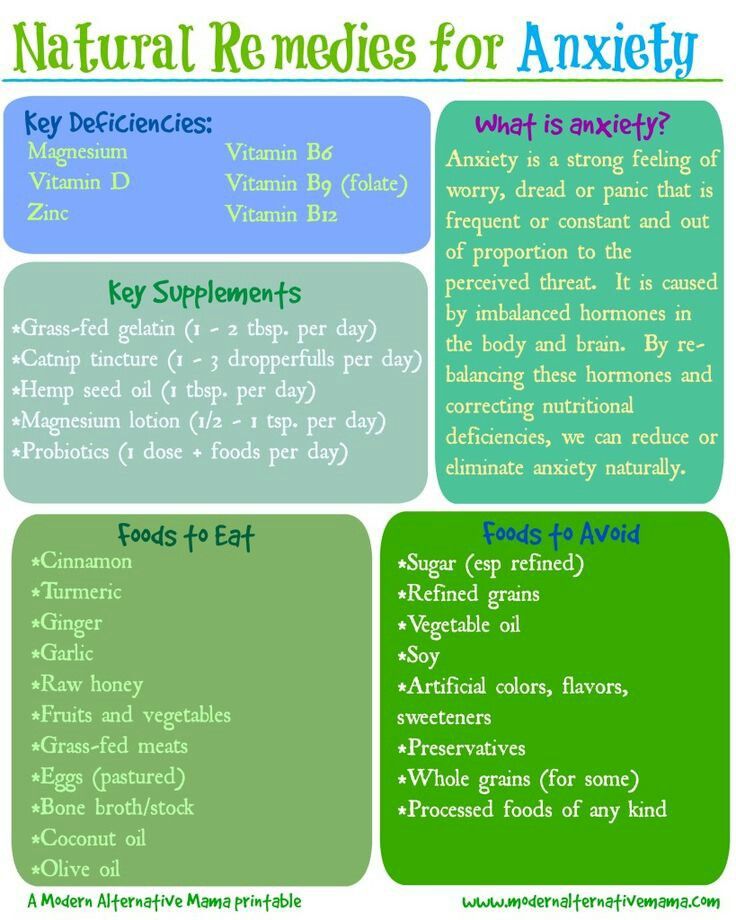

Many factors can contribute to feelings of anxiety and depression. While stress, hormones, or genetics often play a role in these feelings, diet can also affect our mood.

Not getting enough specific minerals and nutrients can throw a wrench in how we feel. This includes getting enough zinc in our daily diet.

Zinc is essential for physical function, but it may also play a role in mental wellness. Maintaining adequate zinc levels can improve your overall well-being, helping you feel healthier and happier.

Zinc is crucial for brain growth and development and several other body functions, including:

- immune function

- protein synthesis

- DNA synthesis

- wound healing

- cellular health

- general growth and development

The body can’t produce or store zinc on its own, so it must come from your diet or supplements.

Zinc is generally obtained through a variety of plant and animal foods. Foods that don’t have zinc naturally, such as baking flour and snack bars, often contain synthetic forms of zinc.

You can also find supplements with zinc.

Because zinc plays a role in immune function, it can also be found in various cold medications, lozenges, and nasal sprays.

Zinc not only plays an essential role in the way our immune system functions, but it also affects our neural (aka brain) processes, according to a 2017 study. The study also links zinc and specific hormones or neurotransmitters — namely our “happiness” hormones, serotonin, and dopamine.

According to a 2021 study, zinc does this by helping elevate levels of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) in the areas of our brain that control our emotions. When zinc is in low supply, BDNF levels drop, and so does our mood.

Other research supports this, finding ties between zinc and anxiety across different groups of people:

- A 2011 study suggests that low levels of zinc may lead to lower gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) levels in the brain — a neurotransmitter that blocks specific signals to reduce fear, worry, and stress.

Zinc supplementation can help raise levels of GABA, thereby improving symptoms of anxiety.

Zinc supplementation can help raise levels of GABA, thereby improving symptoms of anxiety. - A 2019 study found that regular use of multivitamin mineral supplements may improve anxiety in young adults between ages 18 and 24.

- In a 2019 study of Japanese workers, mental health conditions and diet were linked, with researchers concluding that low levels of zinc, magnesium, and copper contributed to feelings of depression and anxiety for workers.

- A 2020 study suggests that zinc deficiency in older adults was tied to higher rates of depression and anxiety. A 2021 study of this age group showed that using zinc supplements significantly reduced signs and symptoms of anxiety and depression.

Studies have also linked low levels of zinc and depression.

A 2017 review reported that several studies found a link between lower levels of zinc and depression. It also found that adding zinc supplementation in combination with other treatments may help improve symptoms of depression.

According to a 2011 review, zinc may improve signs of depression or mood disorder because it helps reduce inflammation, inhibiting brain function and cognitive performance.

When our bodies get enough zinc, inflammation is reduced or eliminated, and our immune and brain systems can function at peak levels, which all contribute to a healthier body and mind.

Maintaining healthy zinc levels can have a positive impact on your overall physical and mental well-being.

According to the National Institutes of Health (NIH), besides reducing symptoms of anxiety, zinc may also help:

- support immune function

- promote wound healing

- treat or prevent chronic diseases such as diabetes, high blood pressure, and metabolic syndrome

- prevent age-related macular degeneration or vision loss

- promote sexual health

- treat diarrhea

- maintain healthy skin

- treat acne

- prevent osteoporosis

- reduce common cold symptoms

- treat neurological symptoms

- boost cognitive function

- reduce inflammation

- lower risk of infection

How much zinc do I need?

The appropriate amount of zinc you should be getting each day generally depends on your age and gender.

The recommended dietary amount (RDA) is as follows:

- Adult men: 11 mg

- Adult women: 8 mg

- Teen boys (ages 14 – 18): 11 mg

- Teen girls (ages 14 – 18): 9 mg

- Children (under age 13*): 2 mg – 8 mg

The RDA of zinc for women who are pregnant or nursing may be higher, so it’s important to talk with your doctor about how much you need.

*Babies and children need less zinc than teens and adults. Talk with your child’s pediatrician for more information and to make sure your child is getting the right amount for their age.

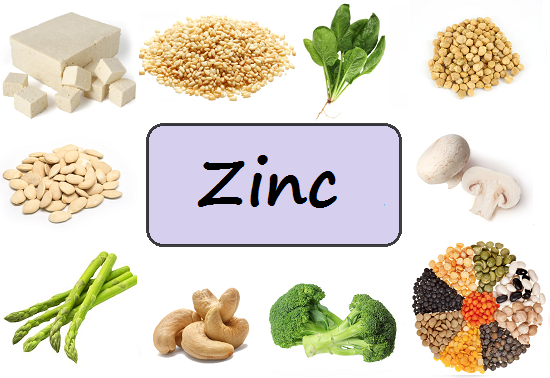

There are multiple ways to get your recommended daily amount of zinc. The easiest is through diet. Many foods contain enough zinc to meet your RDA, and they’re likely items you already eat regularly.

Zinc-rich foods include:

- red meat

- fish and seafood such as crabs and oysters

- poultry

- nuts and seeds

- beans, chickpeas, lentils, and other legumes

- certain vegetables such as mushrooms, asparagus, and kale

- eggs

- milk and other dairy products

- whole grains

- certain fortified foods such as breakfast cereals and snack bars

Supplements are another way to get your daily dose of zinc, particularly if your diet isn’t cutting it.

Zinc supplements can be especially helpful for those who have or are at chance of having zinc deficiency. According to NIH, this can include:

- people with gastrointestinal diseases such as Crohn’s disease

- women who are pregnant or nursing

- vegetarians or vegans

- people with sickle cell anemia

- older infants who are exclusively nursing

- people with chronic kidney disease

- those who misuse alcohol

There are several types of zinc supplements, and they can come in various formats, including capsules, tablets, liquids, and even topicals.

Dosage can depend on your current diet and zinc levels, so you may consider speaking with your doctor before adding a zinc supplement to your routine. They can recommend specific types and amounts tailored to your needs.

Getting too much or too little zinc can lead to some serious — and seriously unpleasant — side effects.

Nearly 1 billion people worldwide have some level of zinc deficiency due to not having enough zinc in their diet, according to a 2015 study. While more severe cases are rare, not getting enough zinc can still wreak havoc on your health.

While more severe cases are rare, not getting enough zinc can still wreak havoc on your health.

Zinc deficiency can cause:

- weakened immune system

- cold symptoms

- skin rash

- skin ulcers

- weight fluctuations

- diarrhea

- poor concentration

- hair loss

- vision problems

- breathing problems

A 2017 review also suggests that low zinc levels can increase your chance of contracting infections, including pneumonia, malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV.

Getting too much zinc can also create issues, including toxicity. Zinc toxicity can be serious and can cause various acute or chronic side effects, such as:

- cramps

- diarrhea

- changes in appetite

- changes in cholesterol levels

- weakened immune function

- nausea

- vomiting

- headaches

High levels of zinc are often caused by supplement use. Figuring out supplement dosage can be tricky because you also need to account for the zinc you’re getting through your diet. Taking too much zinc can increase your levels and lead to toxicity.

Taking too much zinc can increase your levels and lead to toxicity.

A 2015 study shows that too much zinc can also affect how your body absorbs copper and iron — two other essential minerals. Excessive amounts of zinc can even lead to a copper deficiency.

Zinc can also interfere with the effectiveness of some medications, including antibiotics and diuretics.

Zinc is an essential nutrient that supports many of our body’s functions, including immune function, cellular health, and certain brain functions.

It can also affect our mood, with zinc deficiencies often linked to anxiety and depression. By maintaining proper zinc levels, we can help improve our overall well-being.

Because our bodies don’t produce zinc, it must come through outside sources, such as diet or supplements.

It’s crucial to be cautious when using zinc supplements — it can be easy to overdo it. This can lead to zinc toxicity, which can cause immune issues, cramping, and changes in your cholesterol.

If you’re experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression, consider speaking with a healthcare or mental health professional.

They can work with you to determine whether a zinc deficiency is behind how you feel or whether there’s another underlying cause. They can then help you develop a treatment plan tailored to your unique needs.

Decreased Zinc and Increased Copper in Individuals with Anxiety

1. Weinberger DR. Anxiety at the frontier of molecular medicine. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:1247–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

2. Gross C, Hen R. The developmental origins of anxiety. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:545–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. Leman S, Le Guisquet A, Belzung C. Liens anxiété-mémoire: Études expérimentales. In: Ferreri M, editor. Anxiété, anxiolytiques et troubles cognitifs. Paris: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 71–9. [Google Scholar]

4. Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime Prevalence and Age-of-Onset Distributions of DSM-IV Disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

5. Alonso J, Lépine JP. Overview of key data from the European Study of Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:3–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

6. ESEMed/MHEDEA 2000 investigators, author Prevalence of mental disorders in Europe: results from the European Study of the Epidemiology of Mental Disorders (ESEMeD) project. Acta Psychiat Scand. 2004;109:21–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

7. Wittchen HU, Jacobi F. Size and burden of mental disorders in Europe-a critical review and appraisal of 27 studies. Eur J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2005;15:357–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

8. Tuthill A, Slawik H, O’Rahilly S, Finer N. Psychiatric co-morbidities in patients attending specialist obesity services in the UK. QJM: Monthly Journal of the Association of Physicians. 2006;99:317–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

9. De Graaf R, Bijl RV, Smit F, Vollebergh WAM, Spiker J. Risk factors for 12-month comorbidity of mood, anxiety and substance use disorders: Findings from the Netherlands Mental Health Survey and Incidence Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:620–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:620–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

10. Issakidis C, Andrews G. Service utilisation for anxiety in an Australian community sample. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2002;37:153–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

11. Eisenberg DM, Davis RB, Ettner SL, Appel S, Wilkey S, van Rompay M, et al. Trends in alternative medicine use in the United States, 1990–1997: Results of a follow-up national survey. JAMA. 1998;280:1569–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Lépine JP. The epidemiology of anxiety disorders: prevalence and societal costs. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:4–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

13. Raulin J. Etudes clinique sur la vegetation. Annales des Scienceas Naturelle: Botanique. 1869;11:93–299. [Google Scholar]

14. Maze P. Influences respectives des elements de la solution gmineral du mais. Annales de l’Institut Pasteur (Paris) 1914;28:21–69. [Google Scholar]

15. Todd WR, Elvehjem CA, Hart EB. Zinc in the nutrition of the rat. American Journal of Physiology. 1934;107:146–56. [Google Scholar]

American Journal of Physiology. 1934;107:146–56. [Google Scholar]

16. Vallee BL, Auld DS. Zinc coordination, function, and structure of zinc enzymes and other proteins. Biochemistry. 1990;29:5647–59. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

17. Miller WJ, Blackmon DM, Gentry RP, Pitts WJ, Powell GW. Absorption, excretion, and retention of orally administered zinc-65 in various tissues of zinc-deficient and normal goats and calves. Journal of Nutrition. 1967;92:71–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

18. Brown RS, Sander C, Argos P. The primary structure of transcription factor IIIA has 12 consecutive repeats. FEBS Letters. 1985;186:271–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

19. McNulty TJ, Taylor CW. Extracellular heavy-metal ions stimulate Ca2+ mobilization in hepatocytes. Biochemical Journal. 1999;339(Pt 3):555–61. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

20. Zalewski PD, Forbes IJ, Betts WH. Correlation of apoptosis with change in intra-cellular labile Zn(II) using zinquin [(2-methyl-8-p-toluenesulphonamido-6 quinolyloxy)acetic acid], a new specific fluorescent probe for Zn(II) Biochemical Journal. 1993;296:403–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

1993;296:403–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

21. Prasad AS. Clinical manifestations of zinc deficiency. Annual Review of Nutrition. 1985;5:341–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

22. Cunnane SC. Role of zinc in lipid and fatty acid metabolism and in membranes. Progress in Food and Nutrition Science. 1988;12:151–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

23. Endre L, Katona Z, Gyurkovits K. Zinc deficiency and cellular immune deficiency in acrodermatitis enteropathica. Lancet. 1975;2:119–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

24. Aggett PJ. Acrodermatitis enteropathica. Journal of Inherited Metabolic Disease. 1983;1:39–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

25. Halsted JA, Ronaghy HA, Abadi P. Zinc deficiency in man. American Journal of Medicine. 1972;53:277–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

26. Prasad AS. Role of zinc in human health. Boletin de la Asociacion Medica de Puerto Rico. 1991;83:558–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

27. Vallee BL, Falchuk KH. The biochemical basis of zinc physiology. Physiological Reviews. 1993;73:79–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Physiological Reviews. 1993;73:79–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

28. Hambidge M. Human zinc deficiency. J Nutr. 2000;130(5S Suppl):1344S–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

29. Ho E, Ames B. Low intracellular zinc induces oxidative DNA damage, disrupts p53, NFκB, and AP1 DNA binding, and affects DNA repair in a rat glioma cell line. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99(26):16770–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

30. Song Y, et al. Zinc Deficiency Affects DNA Damage, Oxidative Stress, Antioxidant Defenses, and DNA Repair in Rats. Journal of Nutrition. 2009;139:1626–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

31. Powell S. The Antioxidant Properties of Zinc. Journal of Nutrition. 2000;130:1447S–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

32. Tanner S, Baranov V, Bandura D. Reaction cells and collision cells for ICP-MS: a tutorial review. Spectrochimica Acta. 2002;57:1361–452. [Google Scholar]

33. Little KY, Castellanos X, Humphries LL, Austin J. Altered zinc metabolism in mood disorder patients. Biol Psychiatry. 1989 Oct;26(6):646–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biol Psychiatry. 1989 Oct;26(6):646–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

34. Maes M, de Vos N, Demedts P, Wauters A, Neels H. Lower serum zinc in major depression in relation to changes in serum acute phase proteins. J Affect Disord. 1999 Dec;56(2–3):189–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

35. Desnyder R. Lower serum zinc in major depression is a sensitive marker of treatment resistance and of the immune/inflammatory response in that illness. Biol Psychiatry. 1997 Sep 1;42(5):349–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

36. Russo AJ. Increased Serum Cu/Zn SOD in Individuals with Clinical Depression Normalizes After Zinc and Anti-oxidant Therapy. Nutrition and Metabolic Insights. 2010;3:1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

37. Russo AJ. Decreased Serum Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) in Individuals with Anxiety Increases After Zinc Therapy. Nutrition and Metabolic Insights. 2010;3:1–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

38. Russo AJ. Decreased Serum Hepatocyte Growth Factor (HGF) in Individuals with Depression Correlates with Severity of Disease. Biomarker Insights. 2010;5:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Biomarker Insights. 2010;5:1–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

39. Nowak G, Zieba A, Dudek D, Schlegel-Zawadzka M, Pilc A.Zinc homeostasis and glutamatergic system in the pathogenesis and treatment of depression Psychiatr Pol 2001March–Apr352257–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

40. Crayton J, Walsh W. Elevated serum copper levels in women with a history of post-partum depression. Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology. 2007;14:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

41. Walter G, Lyndon B. Depression in hepatolenticular degeneration (Wilson’s disease) Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31(6):880–2. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

42. Kalueff A, Nutt D. Role of gaba in anxiety and depression depression and anxiety. 2007;24:495–517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Xie X, Smart T. Properties of GABA-mediated synaptic potentials induced by zinc in adult rat hippocampal pyramidal neurones. J Physiol. 1993;460:503–23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

44. Ben-Ari Y, Cherubini E. Zinc and GABA in developing brain. Nature. 1991;353:220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Ben-Ari Y, Cherubini E. Zinc and GABA in developing brain. Nature. 1991;353:220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

45. Takeda A, Hirate M, Tamano H, Oku N. Release of glutamate and GABA in the hippocampus under zinc deficiency. J Neurosci Res. 2003;72(4):537–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

46. Takeda A, Itoh H, Imano S, Oku N. Impairment of GABAergic neurotransmitter system in the amygdala of young rats after 4-week zinc deprivation. Neurochem Int. 2006;49(8):746–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. McClain CJ, Adams L, Shedlofsky S. Zinc and the gastrointestinal system. In: Prasad AS, editor. Essential and Toxic Trace Elements in Human Health and Disease. New York: Alan R. Liss Inc; 1988. pp. 55–73. [Google Scholar]

48. McNall AD, Etherton TD, Fosmire GJ. The impaired growth induced by zinc deficiency in rats is associated with decreased expression of the hepatic insulin-like growth factor I and growth hormone receptor genes. J Nutr. 1995;125:874–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

49. Pfaffl MW, Gerstmayer B, Bosio A, Windisch W. Effect of zinc deficiency on the mRNA expression pattern in liver and jejunum of adult rats: monitoring gene expression using cDNA microarrays combined with real-time RT-PCR. J Nutr Biochem. 2003;14:691–702. 2002;283:C623–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Pfaffl MW, Gerstmayer B, Bosio A, Windisch W. Effect of zinc deficiency on the mRNA expression pattern in liver and jejunum of adult rats: monitoring gene expression using cDNA microarrays combined with real-time RT-PCR. J Nutr Biochem. 2003;14:691–702. 2002;283:C623–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

50. Dieck HT, Döring F, Roth HP, Daniel H. Changes in rat hepatic gene expression in response to zinc deficiency as assessed by DNA arrays. J Nutr. 2003;133:1004–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

51. Masood A, Nadeem A, Mustafa SJ, O’Donnell JM. Reversal of oxidative stress-induced anxiety by inhibition of phosphodiesterase-2 in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2008;326:369–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

52. Bouayed J, Rammal H, Dicko A, Younos C, Soulimani R. Chlorogenic acid, a polyphenol from Prunus domestica (Mirabelle), with coupled anxiolytic and antioxidant effects. J Neurol Sci. 2007;262:77–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

53. Zhou Z, Wang L, Song Z, Saari JT, McClain CJ, Kang YJ.![]() Zinc supplementation prevents alcoholic liver injury in mice through attenuation of oxidative stress. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1681–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Zinc supplementation prevents alcoholic liver injury in mice through attenuation of oxidative stress. Am J Pathol. 2005;166:1681–90. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

54. Kang X, et al. Zinc Supplementation Enhances Hepatic Regeneration by Preserving Hepatocyte Nuclear Factor-4 in Mice Subjected to Long-Term Ethanol Administration. The American Journal of Pathology. 2008;172:916–25. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Anxiety in my soul... | Articles

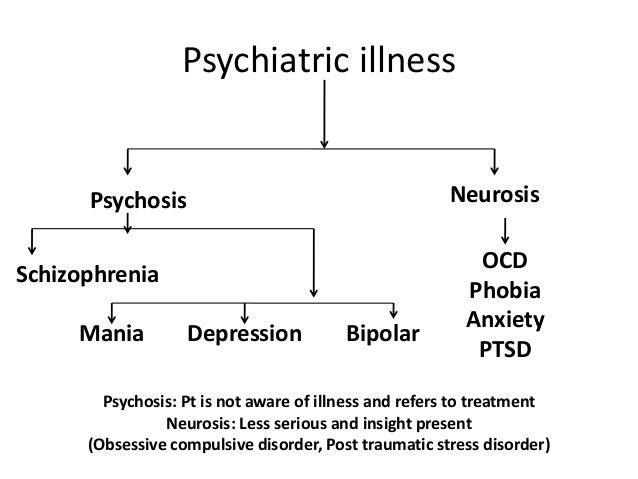

March 26, 2019The main reason why the diagnosis and correction of mental and psychological problems is carried out late is the fear of being labeled as "mentally ill".

Anxiety is the most common phenomenon in the mental sphere of modern man. Without a shadow of a doubt, we are all anxious, only the level of anxiety differs. The Dalai Lama may be less anxious than you, but that's not the case.

The Dalai Lama may be less anxious than you, but that's not the case.

By definition, anxiety is a constant internal readiness to confront a threat. In this case, any uncertainty can be a threat. The greater the uncertainty, the greater the tension. The missile forces have a color definition of the degree of threat: green, yellow, red. The red level requires maximum resource mobilization.

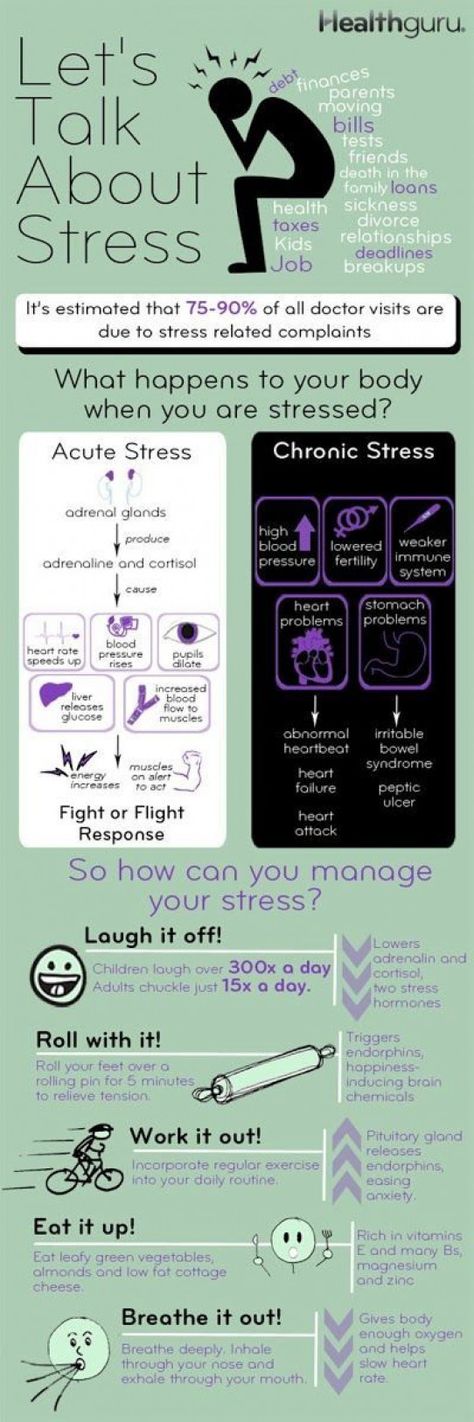

If such states of strong tension are short-lived, then we can endure them without any damage to health. If anxiety exists for a long time and at a high level, then this will lead to destabilization of the control systems of body functions. Everyone has heard about vegetative-vascular dystonia (VVD), which, it seems, does not exist; so: this is it! The autonomic nervous system begins to work incorrectly. And since it controls the entire internal mechanics of the body, interruptions in well-being begin. At first, this can be manifested by functional disorders in the form of fluctuations in blood pressure, malfunctions of the gastrointestinal tract, headaches, a feeling of lack of air, tension in the body. Hands and feet may feel chilly and sweaty, body temperature may fluctuate. At the same time, problems with sleep and appetite may appear.

Hands and feet may feel chilly and sweaty, body temperature may fluctuate. At the same time, problems with sleep and appetite may appear.

At the level of the psyche, anxiety is manifested by constant anxiety, fuss, negative premonitions about the future, disturbing thoughts, irritability, irascibility, tearfulness. In some people, anxiety can occasionally manifest itself clearly, in the form of anxiety attacks, the so-called "panic attacks".

If the anxiety state exists for a long time, then it can lead to psychosomatic diseases. The most common are gastritis and duodenitis, peptic ulcer, irritable bowel syndrome, and other motor disorders; hypertension, coronary heart disease, Raynaud's syndrome.

But there is an absolutely fair view that all our diseases are ultimately psychosomatic, including oncology. Long-term tension leads to the depletion of the body and its reserves.

But that's not all the news, because anxiety has a "sweet couple": it is often accompanied by depression. Then they talk about an anxiety-depressive state: lethargy, apathy join the manifestations of anxiety, and self-confidence decreases. The future is beginning to be seen in a bleak light. The ability to enjoy life and enjoy life is also reduced. Everything seems gray and dull. The state of depression leads to a deterioration in functioning, which ultimately, in a vicious circle, maintains a dreary mood. Depression can lead to a decrease in the body's defenses and problems with immunity.

Then they talk about an anxiety-depressive state: lethargy, apathy join the manifestations of anxiety, and self-confidence decreases. The future is beginning to be seen in a bleak light. The ability to enjoy life and enjoy life is also reduced. Everything seems gray and dull. The state of depression leads to a deterioration in functioning, which ultimately, in a vicious circle, maintains a dreary mood. Depression can lead to a decrease in the body's defenses and problems with immunity.

According to the World Health Organization, depression is one of the most pressing human problems worldwide. And its importance is growing every year.

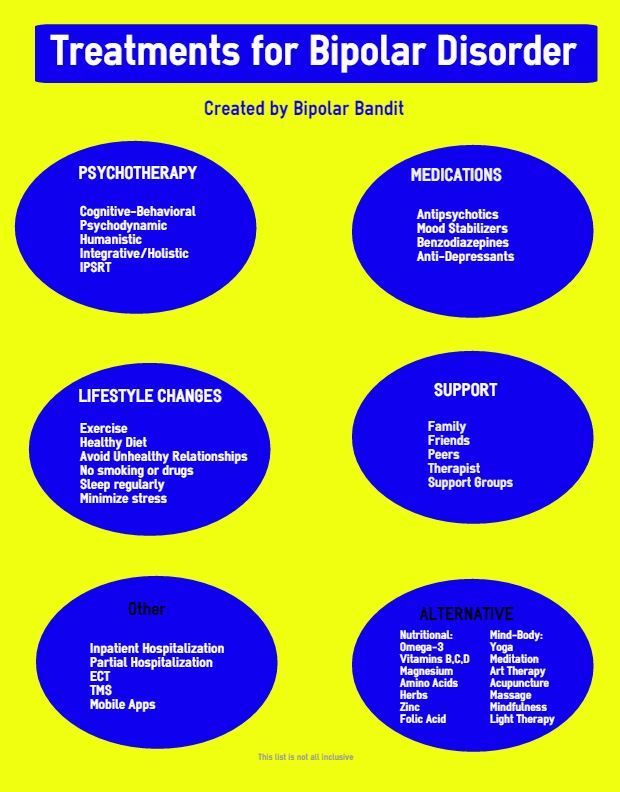

Now for some good news: anxiety-depressive states are well corrected within the framework of psychotherapy, which is an excellent opportunity to work with a psychologist or psychotherapist.

Emotions and nutrients

What we eat affects not only physical well-being, but also mental health. How are our diet and mood connected?

Top 5 Nutrients for Nervous System Health:

-

Omega-3 fatty acids are vital for the normal development and functioning of the brain at all stages of life, from infancy to old age.

They are necessary for mental activity and behavior, affect mood and emotions, improve connections between neurons.

They are necessary for mental activity and behavior, affect mood and emotions, improve connections between neurons. -

The importance of vitamin D has long transcended the boundaries of bone health - we need the sunshine vitamin to protect against cancer and autoimmune diseases, the synthesis of sex hormones and ... good mood. Studies have shown that vitamin D affects the synthesis of serotonin, which is responsible for the emotional state.

-

Magnesium is indispensable in the fight against stress, it protects the nervous system from overexertion and has a beneficial effect on mental health. No wonder it is called the mineral of tranquility.

-

Provision of the body with zinc is extremely important for the coordinated work of the central nervous system in all periods of life. Zinc regulates the proper development of nerve cells and connections between them, and also has neuroprotective properties - it protects them from damage by free radicals and toxins.

-

B vitamins help the nervous system with significant mental stress and stress. They ensure the proper functioning of the nerves, the transmission of impulses between neurons, the absorption of nutrients and oxygen by them.

But alcohol, caffeine and sugar increase the level of lactate (lactic acid), which, in turn, contributes to the emergence and intensification of anxiety, causes a feeling of panic in stress-sensitive people.

A serious problem cannot be dealt with with the help of nutrients alone, but it is quite possible to prevent it.

Iron and zinc deficiency in the body: symptoms, causes and signs

IRON (Fe)

This trace element enters the human body with animal and plant foods. Also, a certain proportion comes with drinking water (about 10–20 mg per day). This trace element is best absorbed from animal products. About 60% of the iron contained in the body is part of hemoglobin (3–5 g).

Determining the provision of the body with a microelement

Here is a list of negative conditions (NS), the cause of which in most cases lies in iron deficiency in the body. This requires a mandatory correction. Most often, with iron deficiency, experts recommend optimal nutrition and supplementation.

The method of information testing is based on self-assessment of identified NAs, which, in turn, requires a balanced and objective approach. You should pay attention to conditions (observed quite often or constantly) that are pronounced. On the other hand, some NS may occur rarely, for random reasons. In this case, such negative conditions are mostly not associated with iron deficiency, so they should not be isolated.

In the presented list, it is necessary to highlight the NS that are characteristic of your state of health. Then count their number.

- Headaches.

- Nervousness and restlessness.

- Reduced concentration.

- Vertigo.

- Depression.

- Irritability.

- Frequent feeling of chills.

- Memory deterioration.

- Reduced performance.

- Slow decision making.

- General weakness.

- Increased fatigue.

- Deterioration of visual acuity in low light.

- Immunodeficiency states.

- Frequent colds.

- Prolonged tonsillitis.

- Pale skin.

- A sharp increase in the number of wrinkles.

- Pinpoint hemorrhages on the skin.

- Increased hair loss.

- Skin tone change.

- Deformation of the nail plates.

- Cold hands and/or feet.

- Puffiness.

- Inflammation of the mucous membranes of the mouth, tongue.

- Rapid heartbeat.

- Anemia (anemia).

If you have noted 7 or less HC, then the supply of your body with iron can be assessed as normal or as close as possible to it. 8–12 negative conditions correspond to a mild degree of a decrease in the amount of this microelement. If you excreted 13 or more HC, this indicates an iron deficiency.

If you excreted 13 or more HC, this indicates an iron deficiency.

Each of the listed negative conditions is a symptom that can sometimes be observed with insufficient micronutrient supply of the body with iron. But the analysis becomes more complicated, since the cause of each of the listed NS can be not only iron deficiency, but also a lack of bioelements and vitamins.

Possible reasons for such a negative state as a tendency to depression may be insufficient supply of iron to the body (deficiency), as well as a lack of another fifteen bioelements and vitamins. In this regard, it is required to take into account tens of NS.

It is important to note that in addition to participation in oxidative processes and oxygen transport, iron performs many important functions in the human body. An essential role in providing immune protection, in energy metabolism, etc. Iron deficiency is often hidden and manifests itself in various disorders of tissues and organs, which can be periodic or mild.

According to WHO (World Health Organization), iron deficiency is one of the most common micronutrient deficiencies among the entire population of the Earth. It should be noted that this dynamics is increasing every year.

When symptoms of iron deficiency are detected, it is necessary to replenish this trace element. Often the reason for its deficiency is too little intake of iron-containing foods. Therefore, experts for the fight and prevention of iron deficiency in the body recommend that the following foods be included in the diet - beef and beef liver, fish, seafood, pumpkin, peas, leafy vegetables, oatmeal and buckwheat, brewer's yeast, apples, pomegranates, figs, grapes, cocoa

Today, the pharmaceutical market includes many different preparations and dietary supplements that contain iron (including in combination with vitamins). MIRRA recommends special dietary supplement MIRRA-FERRUM . The drug is based on highly digestible iron lactate.

ZINC (Zn)

This micronutrient is supplied with various foods (approximately 10–15 mg per day). The body of an adult contains about 3-5 g of zinc. It is present in all organs. Basically, zinc is concentrated in the prostate gland, muscle tissue, red blood cells, skin, nails, hair.

The body of an adult contains about 3-5 g of zinc. It is present in all organs. Basically, zinc is concentrated in the prostate gland, muscle tissue, red blood cells, skin, nails, hair.

Below is a list of negative conditions that can result from the same cause - zinc deficiency in the body. In this regard, doctors recommend adjusting the diet and taking dietary supplements.

Zinc sufficiency assessment

The method of information testing is based on self-assessment of identified NS. Special attention should be paid to conditions that are observed quite often or constantly, which are pronounced. But on the other hand, some NS can be mild or rare and occur for random reasons, so such conditions should not be isolated, because in most cases they are not symptoms of zinc deficiency in the body.

In the presented list, it is necessary to highlight the negative conditions that are characteristic of your state of health. After that, the number of signs of zinc deficiency should be counted.

- Reduced appetite.

- Sleep disorders.

- Depression.

- Weight loss.

- Memory deterioration.

- Irritability.

- Increased fatigue.

- Cellulite.

- Decreased or loss of taste sensations.

- Olfactory disorders.

- Decreased visual acuity.

- Allergic reactions.

- Frequent colds.

- Inflammation of the skin.

- Slow wound healing.

- Excessive dry skin.

- The appearance of a small amount of blackheads.

- Excessive peeling of the skin.

- Increased hair loss.

- Dandruff.

- Slow hair growth.

- Caries.

- Dullness of hair.

- The appearance of spots on the nails.

- Lamination of nails.

- Irregular menses.

- Premature aging.

If 8 or less NS were identified in the list below, then the level of zinc supply to the body can be assessed as normal or close to it. Number of negative states within 9-14 corresponds to a moderate or mild deficiency of this trace element. Isolation of 15 or more HC can be regarded as zinc deficiency.

Number of negative states within 9-14 corresponds to a moderate or mild deficiency of this trace element. Isolation of 15 or more HC can be regarded as zinc deficiency.

In addition to the negative conditions listed above, there are many systemic disorders. They are mainly associated with sexual or age characteristics of the body, as well as zinc deficiency.

Zinc is present in many enzymes. It performs various functions in the human body. In particular, the microelement is necessary for the synthesis of proteins (collagen, etc.). Experts believe that zinc deficiency in newborn boys in the future can lead to disruption of the full development of the reproductive system, as well as to increased cravings for alcohol. Doctors have traced the link between impotence, male infertility and zinc deficiency.

Organs and tissues are very sensitive to the content of zinc, as well as violations of its metabolism. Therefore, in order for all body systems to function normally, you should regularly consume foods rich in this trace element.