Why would someone hit themselves in the head

Self-Injurious Behaviors | Student Health and Counseling Services

Overview of Self-Injurious Behaviors

Self-injurious behaviors are behaviors that people engage in that cause intentional physical bodily harm to themselves. Self-harm is often carried out when individuals attempt to deal with difficult or overwhelming emotions, and are not sure how manage their emotions in a more effective manner. Self-injury may take on several forms, most commonly cutting, scraping, burning, biting or hitting. Self-destructive behaviors are not to be confused with body piercings or tattoos that are sought for the purpose of self-decoration.

Why Do People Self-Injure?

Based on research, people who engage in self-injurious behaviors claim to experience little to no pain while they are hurting themselves. Rationales for self-injury include feeling anger toward themselves or others, or relieving pain, anger and tension. Self-injurious behaviors are not necessarily suicidal gestures, but individuals who engage in self-injurious behaviors may be experiencing symptoms of anxiety or depression.

Since there is a strong link between suicide and depression, it is important for concerned others to invite open communication about self-injury and suicide. A common myth is that asking individuals if they are contemplating suicide affects their likelihood to attempt or complete suicide. Rather, asking about self-injury or suicide may help people know that you care about them and welcome open communication.

If you have concerns about the endangerment of someone’s life, whether they self-injure or not, contact a local hospital, police, or SHCS Counseling Services.

What Can be Done

People generally do not wish to hurt themselves, but see no better way of managing their emotions. The suggestions below are for people who have made the decision to quit self-injuring, and are looking for alternative strategies to deal with their emotions.

Techniques to Try

- Distract yourself, get away from the situation you are in, and do something else.

- Talk with someone who is supportive, such as a family member, friend, RA, hall director, or counselor.

- Engage in another activity that requires stimulation. Give yourself a massage, take a hot or cold shower, squeeze ice, finger paint, or squish Play-doh.

- Exercise is a way of quickly managing emotions. Go for a brisk walk or run, punch a pillow, swim, lift weights, or engage in other aerobic activities that require physical exertion.

- Pamper yourself by doing something soothing. Read, listen to music, take a relaxing bath, look at the moon or clouds, open a window to get some fresh air.

- Make a list of activities to engage in that have been helpful in the past when you had the urge to self-injure. Keep this list handy to refer to if you do have the urge to self-injure.

Activity Log During Urge to Self-Injure

- Rate the intensity of your urge to hurt yourself on a scale from 1-10.

- Identify which emotions you are feeling.

- Rate the intensity of each emotion on a scale from 1-10.

- Identify the situation you were in prior to your urge to hurt yourself.

- Identify the unhelpful/impulsive thoughts present when you had the urge to hurt yourself.

- Identify more helpful/more realistic thoughts to dispute the unhelpful ones.

- Rate the intensity of your emotions a scale from 1-10 after completing this log.

It may also be helpful to think about the first time self-injury occurred, the situations and emotional factors at that time, and how they were dealt with.

How Can I Break Free From Self-Injury?

Recognizing that there is hope beyond self-injury is the first step, and SHCS can be great support. People often fear that self-injury will be seen as shameful or secretive, but it does not have to be. A counselor can be the empathic encourager that coaches individuals to help them meet their goals. A counselor can also work with individuals to help educate about other coping mechanisms, and to provide support as people look more deeply at their emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. By looking at factors associated with self-injury, and the underlying concerns, many can begin to break free from self-injury.

A counselor can also work with individuals to help educate about other coping mechanisms, and to provide support as people look more deeply at their emotions, thoughts, and behaviors. By looking at factors associated with self-injury, and the underlying concerns, many can begin to break free from self-injury.

Concerned for Others

It can be difficult to learn that ones you care about deliberately injure themselves. It can also be difficult to not want to rush in and “save” them from their pain. People engaging in self-injurious behaviors need to be the ones making the decision to change their behaviors. You can share your concern, and urge them to ask for help and you can let them know that you are available to call if they have the urge to self-injure, feel emotionally overwhelmed, or want to be with someone. Unconditionally showing them that they do not need to self-injure to get love and attention from you can be helpful. Asking if you can take them out to a movie, or to get a snack is a way to provide a distraction, and gives them the chance to accept your offer.

If you are living in the residence halls, asking an RA or hall director to become a part of a support team can be an important step in empowering the person self-injuring, especially if the self-injury is distressing others, or endangering the safety of the one you care about.

How We Can Help

SHCS provides acute care, drop-in services, brief individual therapy, group therapy, and referrals for on-going therapy.

You can schedule an intake with a counselor at North Hall by calling (530) 752-2349. Acute Care drop-in services are available on the first floor of the Student Health and Wellness Center.

Resources

- SHCS Counseling Services

- S.A.F.E Alternatives

A new look at self-injury

What makes young people cut, scratch, carve or burn their skin, hit or punch themselves, or even bang their heads against a wall?

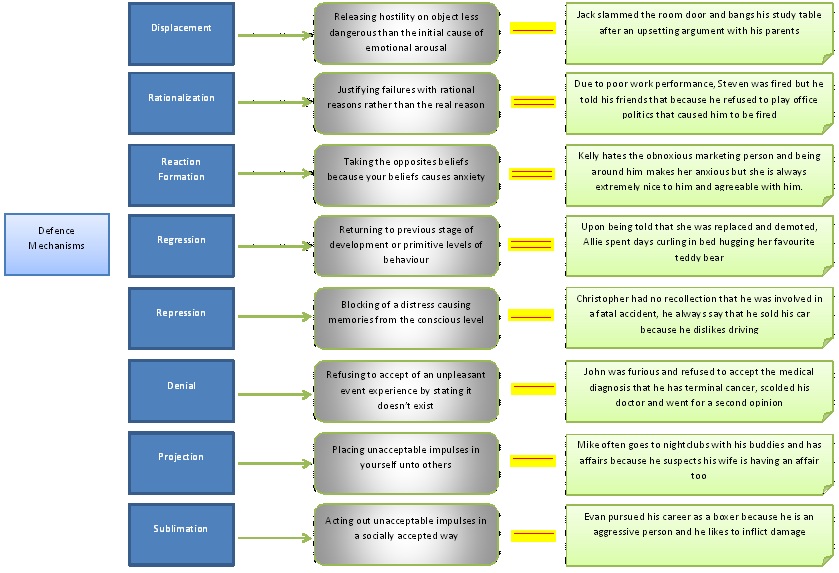

For years, psychologists theorized that such self-harming behaviors helped to regulate these sufferers' negative emotions. If a person is feeling bad, angry, upset, anxious or depressed and lacks a better way to express it, self-injury may fill that role.

If a person is feeling bad, angry, upset, anxious or depressed and lacks a better way to express it, self-injury may fill that role.

Also known as non-suicidal self-injury, or NSSI, the condition is classified in the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (2013) as a "new disorder in need of further study," as well as a symptom of borderline personality disorder, which is marked by such tendencies as emotional instability, unstable relationships and chronic feelings of emptiness. (See companion article on who is more likely to self-injure.)

For treatment, practitioners often turn to dialectical behavior therapy because of its effectiveness in treating borderline personality disorder in general. But now, two researchers at Harvard University are taking a different tack on this inquiry. Joseph Franklin, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of suicide researcher and psychologist Matthew Nock, PhD, wanted to step back from earlier assumptions about self-injury and think more broadly about what might be driving self-harming behavior.

Although researchers generally accepted that NSSI helped people deal with strong negative emotions, Franklin wanted to understand more about why that was the case. Around the same time, Jill Hooley, DPhil, who heads Harvard's experimental psychopathology and clinical psychology program, was finding that people who engaged in NSSI would endure experimentally induced pain for much longer than control participants, and she wondered why. What factors kept self-injurers from apparently acting in their best interests and avoiding pain? And could identifying those factors help explain why people were motivated to engage in NSSI in the first place?

"We were both interested in knowing why people hurt themselves," says Hooley, "but Joe was focused on the possible [emotional] benefits of NSSI and I was looking at the motivations behind it."

While over time their interests and investigations have converged, when they first discovered each other's work, "we were like, ‘Oh, this makes so much sense!'" Hooley adds. "This is how the various findings fit together. It was very exciting."

"This is how the various findings fit together. It was very exciting."

Why self-injury?

Franklin started his investigation with one of the central questions in the field: Why would people report feeling better after hurting themselves?

"It seemed very strange to me, and to a lot of other people," says Franklin. Most studies on the topic had relied on self-reports, "but I wanted to look at this experimentally and biologically to see if it was really true."

In a 2010 study in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology, Franklin and colleagues used a task that measured people's defensive eye-blink responses before and after they dipped their hands into ice-cold water. The results indicated that self-injurers do in fact feel better afterward, he found.

A second finding was more surprising.

"Everyone else reported feeling better, too," he says.

That is, healthy controls showed exactly the same degree of physiological defensiveness and subsequent physiological relief as those who engaged in self-injury. In a 2013 paper in Clinical Psychological Science, Franklin's team replicated the finding and also showed that most people had equivalent changes in positive emotions in response to shocking stimuli.

In a 2013 paper in Clinical Psychological Science, Franklin's team replicated the finding and also showed that most people had equivalent changes in positive emotions in response to shocking stimuli.

Franklin then turned to the pain literature to see if he could gain more understanding. There, he discovered something described by psychologists 70 years ago: a phenomenon called pain offset relief. According to this concept, virtually everyone experiences an unpleasant physical reaction to a painful stimulus. Removing the stimulus does not return the individual to their pre-stimulus state, however. Rather, it leads them into a short but intense state of euphoria.

Using a technique called pain offset relief conditioning, those scientists also found that if you paired the pain with a stimulus, over time, people would react more favorably to the pain because they had learned to associate it with pain relief. For example, when researchers shocked rats and then presented them with a pleasant odor, over time, the rats began seeking out the smell.

Testing this paradigm with various types of shocks and physiological measures, Franklin continued to find powerful pain-offset relief effects in all of his participants, self-injurers and controls alike. People who self-injure may unwittingly be tapping into this mechanism, Franklin surmises. The first time they hurt themselves, they experience unpleasant pain. But when they keep doing it and experience pain relief, they begin to associate cutting or other forms of self-injury with relief, and they return for more.

"That is contrary to what a lot of people assumed and what a lot of treatments focus on," Franklin says. "People, including myself, were thinking there was something unique about these folks" — that if they were injuring themselves repeatedly, they must perceive or experience pain differently from others.

"But that doesn't appear to be the case at all," he says. "It looks like it's this natural phenomenon that [people who self-injure] happen to be tapping into. "

"

Harmonic convergence

The next research question may seem obvious: If anyone can experience pain relief by inflicting pain on themselves, why don't more of us do it? To ask the question a different way, why do self-injurers harm themselves instead of opting for healthier or more pleasant ways of relieving emotional pain, such as watching a movie, meeting a friend or going to a yoga class?

As Franklin was pondering this question in light of possible benefits to the self-injurer, Hooley and her team wondered about psychological explanations. She already knew that self-injurers would endure physical pain for longer, but why? Was this increased pain endurance linked to some of the psychological factors that are commonly associated with self-injury — depression, hopelessness or dissociation, for instance?

Somewhat surprisingly, her team found no significant associations. So having interviewed all of her self-injuring research participants in detail, she returned to her notes in search of clues.

That's when one factor stood out: How often they spontaneously described themselves as being "bad," "defective" or "deserving of punishment."

"It was as if harming themselves or experiencing pain was somehow congruent with their highly negative self-image," she explains.

To test this possibility, her team developed a measure that specifically assesses self-beliefs about being "bad" and deserving criticism. This time, they found an answer: The higher a person's score on negative self-beliefs, the longer they were willing or able to endure pain.

Given his conversations with Hooley, Franklin was thinking along similar lines. When he asked himself why people would undertake this behavior, he looked at it in context of the fact that most people probably like themselves and therefore don't want to hurt themselves. In ongoing, still unpublished work, he asked participants to rate words like "me," "myself" and "I" on a 10-point scale ranging from most unpleasant to most pleasant. Most people rated themselves between a seven and eight, but self-injurers gave themselves only a two or a three.

Most people rated themselves between a seven and eight, but self-injurers gave themselves only a two or a three.

Likewise, Franklin reasoned that most people would not be overly fond of stimuli that depict blood, wounds, knives or equivalent images. But he surmised that people who self-injure might feel differently, partly because his findings suggested they would associate such images with pain relief. A 2014 study in Clinical Psychological Science shows this is the case: People who had engaged in NSSI over the past year or who had 10 or more lifetime episodes of self-cutting were much less likely to report aversion to these kinds of stimuli than non-injuring controls.

Meanwhile, Hooley has recently completed a neuroimaging study looking at how people process such stimuli.

"We're predicting that images of self-injury will activate reward-processing areas in the brains of people who engage in NSSI," she says, "but not in non-self-injuring controls."

Treatment targets

Now, based on some of these findings, the researchers and their colleagues are exploring new ways to treat self-injury.

In keeping with her discovery that self-worth is an important intervention variable, Hooley is taking a cognitive route. Clinicians might be able to lift self-injurers' inclination to do bad things to themselves, she thinks, by helping them change what are often deeply engrained negative self-views.

In a 2014 paper in Clinical Psychological Science, Hooley and then-graduate student Sarah A. St. Germain report on the results of a five-minute intervention they developed that seeks to change beliefs about self-worth, but in ways that are believable, grounded in reality and relatively subtle.

"You can't do this by simply telling people who self-injure that they should think more positively about themselves," she comments.

The team asked people with NSSI and controls to choose which positive characteristics on a list best described themselves, and then to elaborate on some of those characteristics in detail using examples. Before and after the intervention, the researchers tested people's pain endurance by recording how long they kept their fingers clamped in a pressure device. (To control for noncognitive effects of good mood, the researchers also included a "happy music" condition with NSSI and healthy controls.)

(To control for noncognitive effects of good mood, the researchers also included a "happy music" condition with NSSI and healthy controls.)

After the intervention, self-injurers in the cognitive condition kept their fingers in the device for only about half the time they did initially. And the more their sense of self-worth increased, the less willing they were to stay in the painful situation. Meanwhile, the pain endurance of those in all other conditions remained the same. She has not yet looked at effect duration.

"The natural and adaptive response is to say, ‘I'm done with this.' But people who engage in self-injury don't necessarily see pain as something to escape from," Hooley explains. Instead, experiencing pain validates their sense of being a bad or damaged person.

Increasing their sense of self-worth may undermine this propensity, she adds.

"The more valuable that people feel, the less willing they are to endure a bad situation," she says. "Conversely, the worse people feel about themselves, the more inclined they will be to try [painful] methods of mood regulation that most other people would not even consider. " Franklin, meanwhile, is using his findings to test a behavioral intervention using novel counter-conditioning techniques. The intervention targets self-injurers' propensity to pair pain images with relief, and to harbor negative associations to self-related words. The study is under review, but preliminary evidence suggests that changing people's feelings about self-related words and NSSI-related images can be effective treatments, Franklin says.

" Franklin, meanwhile, is using his findings to test a behavioral intervention using novel counter-conditioning techniques. The intervention targets self-injurers' propensity to pair pain images with relief, and to harbor negative associations to self-related words. The study is under review, but preliminary evidence suggests that changing people's feelings about self-related words and NSSI-related images can be effective treatments, Franklin says.

Studies also show that associating pain with relief and negative thoughts with self-related words are good predictors of future self-injury, suggesting such tasks could be used as early screening tools for NSSI, report Franklin and colleagues in a 2014 article in the Journal of Abnormal Psychology.

These efforts are a step toward effectively treating people who self-injure, and Hooley and Franklin hope that psychologists who create and study interventions will add their own insights to the mix.

"We hope that our research is improving our knowledge about how self-injury works and providing novel treatment targets," Franklin says. "Our goal is for researchers and clinicians to use their creativity to attack these targets in new ways."

"Our goal is for researchers and clinicians to use their creativity to attack these targets in new ways."

Self-injurious behavior

In this article, we provide a brief overview of the main issues related to self-injurious behavior in people with autism, its possible causes and ways to deal with this problem.

One of the biggest challenges faced by people with autism spectrum disorders and their families and friends is the need to cope with self-injurious behavior. Such behavior is usually caused by a complex of reasons, and can pose a serious threat to the safety and well-being of an individual. The traditional behavioral approach is not always effective on its own when dealing with self-harm. To cope with this difficult problem, you need to seek the help of specialists.

For more information on behavioral work with people with ASD, please visit: www.autism.org.uk/behavior

What is self-injurious behavior?

Self-injurious behavior (it is also self-aggression) - actions as a result of which a person inflicts physical harm on himself:

- Head beating

- Biting hands

- Pulling one's own hair

- Eye scratching

- Blows to the face or head

- Pinching, scratching and rubbing to abrasions of the skin

- Strong head shaking

Self-injurious behavior is most common in people with reduced intelligence, who, in addition to autism, have other disorders. But in one form or another, anyone with an autism spectrum disorder can face this problem. If they have dealt with self-harmful behavior in the past, it may return at times of stress, illness, or when significant changes are taking place in a person's life.

But in one form or another, anyone with an autism spectrum disorder can face this problem. If they have dealt with self-harmful behavior in the past, it may return at times of stress, illness, or when significant changes are taking place in a person's life.

Causes

The reasons why a person develops self-injurious behavior are extremely diverse. Most often it is caused by a combination of various factors. The head-banging habit, which originated as a form of sensory stimulation, can later be used as a way to avoid a difficult task. Blows to the ear, provoked by severe otitis, can then occur as an attempt to get what you want from others. Below you will find some more possible causes of self-injurious behavior.

Medical problems or toothache

If your child is having self-injurious behavior, the first and most important thing to check is whether he is suffering from toothache or other health problems. People with autism usually find it difficult to communicate their condition, especially if they are not feeling well. Sometimes self-injurious behavior (for example, if a person hits his ear, banging his head against a wall, etc.) can be provoked by the inability to report their condition, or be one of the ways to cope with pain. Here is a list of possible problems that self-injurious behavior can signal:

Sometimes self-injurious behavior (for example, if a person hits his ear, banging his head against a wall, etc.) can be provoked by the inability to report their condition, or be one of the ways to cope with pain. Here is a list of possible problems that self-injurious behavior can signal:

Infectious diseases (colds, flu, runny nose, ear infections or diseases of the genitourinary system)

Pain (migraine, ear, toothache or menstrual pain)

Seizure activity (various types of epilepsy)

General health problems (constipation, digestion, skin diseases)

Researchers also suggest that there may be a link between some types of self-harm, various types of compulsive behavior and tics. It is believed that the frequency of self-injurious behavior increases in stressful situations (Clements and Zarkowska, 2000).

Neurochemical theories

Researchers have also suggested that there may be a link between self-injurious behavior and features of the body's neurochemical systems.

Endogenous Opiodine System

Research has shown that some people with ASD have elevated levels of beta-endorphins, which increase pain threshold and may thus lead to self-injurious behavior. It has also been suggested that self-harm may promote the release of opioids, which cause a feeling similar to euphoria and help reinforce unwanted behavior.

Serotonin

Some researchers have suggested that the increased blood levels of serotonin found in some people with ASD may cause problem behaviors, including self-harm (Gillberg and Cole, 1992).

Dopamine

Studies have shown that in the brain structures of people with Losch-Niechen syndrome (a hereditary disease, one of the symptoms of which is self-injurious behavior), there is an imbalance in the production of dopamine. Scientists believe that this may have an impact on the development of self-injurious behavior.

Sensory stimulation (increase or decrease in stimulus)

Similar to the opioid effects discussed above, self-injurious behavior can be triggered by a desire for additional sensory stimulation (especially if the person has an elevated pain threshold due to high levels of beta-endorphins) , or to cope with sensory overload (for example, hitting the head may be an attempt to cope with exposure to loud or unpleasant sounds, such as a dog barking or a lawn mower).

Developmental stages

Some self-injurious behaviors are residual manifestations of motor actions characteristic of earlier stages of development (eg, hand biting, a characteristic of infants, may persist into older age).

Communication and learned behavior

Very often self-injurious behavior occurs in people who otherwise cannot communicate their needs, needs and feelings. If a person begins to bang his head terribly, there is a high probability that he will get what he wants, whether it be the attention of loved ones, an object, access to a pleasant activity, or the ability to avoid a difficult task.

Blows to the head may signal that the person is upset and trying to control their feelings. For some, the habit of biting their hands helps to cope not only with grief, but also with great joy. Some people start pinching themselves or pressing on their eyeballs if they lack sensory input or are simply bored.

By analyzing the reactions of others, people quickly realize that self-injurious behavior is a powerful way to keep them in check. Thus, self-harm (such as hitting the head), which initially occurred in response to physical pain or discomfort, gradually becomes a way to get the desired behavior from others (for example, to keep the mother on the TV).

Thus, self-harm (such as hitting the head), which initially occurred in response to physical pain or discomfort, gradually becomes a way to get the desired behavior from others (for example, to keep the mother on the TV).

Repetitive behaviors

Repetitive behaviors, obsessions, and states are common in people with autism spectrum disorders. One form of such conditions can be self-injurious behavior.

Mental disorders

In some cases, self-injurious behavior may be caused by underlying mental problems such as depression or an anxiety disorder. This is especially true for people with high-functioning forms of autism, or Asperger's syndrome.

Strategies

Here are some basic ideas to help you prevent or respond to self-harming behavior in your loved ones. However, if self-injurious behavior could cause serious injury to oneself, we strongly recommend seeking professional help first.

How to prevent

What daily activities can prevent self-injurious behavior.

Eliminate health problems and toothache

Make an appointment with your patient's lead doctor and, if necessary, get a referral from him to the necessary specialists. Gather and take with you in advance data on all instances of self-injurious behavior: what day, what time the episode occurred, how often the behavior occurs, when it starts, how long it lasts, etc. Your notes will help your doctor figure out if the self-injurious behavior could be caused by physical discomfort or pain.

Determine the behavior function

Try to understand the function of the self-injurious behavior in this situation. The function of self-harm can be both the search for sensory stimulation and the reaction to pain. In general, a functional analysis of behavior is a rather complicated procedure, and in this matter it is better to resort to the help of a specialist.

Develop Communication Skills

Teach your client to communicate their needs, wants, and discomforts in a way that is more acceptable than self-injurious behavior such as cards.

Use a schedule and maintain a structured environment

Try to keep a consistent schedule so that events throughout the day are predictable and, as a result, cause your client less anxiety. Try not to be bored and busy all the time, limit opportunities to resort to self-injurious behavior. Separately plan how you will deal with difficult situations or difficult moments during the day. During this time, try to structure the environment even more and provide the ward with additional support and assistance.

Provide opportunities for sensory stimulation

If the cause of self-injurious behavior is seeking sensory stimulation, provide opportunities to experience similar sensations in a more acceptable way and make these activities part of your daily routine. Jumping on a trampoline or riding a merry-go-round can stimulate the vestibular apparatus just as much as the habit of shaking or banging your head. By giving your litter a whole bag of chewable items (either edible or not): gum, carrots, dry pasta, nougat, you can greatly reduce his need to bite his hands.

Exercise in mind

Scientists suggest that regular aerobic exercise not only improves emotional and physical well-being, but also reduces self-injurious and aggressive behavior (Rosenthal-Malek & Mitchell, 1997). Aerobic activities include running, swimming, cycling, trampolining, dancing, aerobics, etc. It is best if classes take place at least three times a week. Think about what might be of interest to your ward, and include sports activities in your daily schedule. In some cases, before starting training, you will need to enlist the support of a professional trainer.

Reinforce desired behaviors

Make a habit of reinforcing alternative behaviors and situations throughout the day where your client does not harm himself. This will help him understand that when he behaves differently, it leads to pleasant consequences. Thus, he will more often choose an alternative form of behavior in order to receive encouragement. Encouragement in this case can be both verbal praise and attention, and joint pleasant activities, toys, tokens or favorite treats in small quantities. Make it clear which behavior deserves a reward (“Jane, you are looking forward to it”) and try to provide reinforcement immediately after the desired behavior (“Now you can play 10 minutes on the computer”). Be aware that not all people with ASD appreciate social rewards. For some, verbal praise may not be a pleasure, but another stressor that will reduce the likelihood that a person will behave the way you want again in the future.

Make it clear which behavior deserves a reward (“Jane, you are looking forward to it”) and try to provide reinforcement immediately after the desired behavior (“Now you can play 10 minutes on the computer”). Be aware that not all people with ASD appreciate social rewards. For some, verbal praise may not be a pleasure, but another stressor that will reduce the likelihood that a person will behave the way you want again in the future.

Medication intervention

There is evidence to suggest that certain medications can significantly reduce self-injurious behavior in some people. However, along with physical restraint, drug therapy is considered one of the last means by which to influence a person who is faced with such a problem. Prescribing drugs and the treatment itself should be carried out under the strict supervision of a specialist, but even in this case, it is necessary to combine treatment with constant attempts to teach the person new skills and alternative behavior.

How to Respond

Responding quickly is the key to safety

All self-injurious behavior should be dealt with as quickly as possible and addressed immediately. Even if the function of behavior is to attract attention, it is unacceptable to ignore a situation in which a person can cause serious harm to himself. The correct response to self-injurious behavior depends on many circumstances, but below we will give some general advice. It is very important that, despite the use of all these strategies, a person retains the opportunity to learn communication and self-regulation skills.

- Try to respond to self-harming behavior as calmly as possible. Don't comment, keep a straight face. Your emotional response may inadvertently reinforce the unwanted behavior. Speak calmly, clearly, without raising your voice.

- Lower requirements if that's the issue. If your mentee is unable to complete the task (it turned out to be too difficult, or he is not able to do it at the moment), reduce the requirements, or completely abandon them.

You will return to work later when he calms down.

You will return to work later when he calms down. - Remove the unpleasant sensory stimulus (sound, smell, light), or try to reduce its effect.

- Help with physical discomfort (eg, pain medication).

- Try to get the person's attention, call them by name and give them simple instructions they can follow instead of self-injurious behavior. For example: "David, fold your hands." Use visual cues to reinforce understanding of instructions.

- Quickly move the person to another activity that will prevent them from continuing to hurt themselves (eg, something that needs to be done with both hands), provide encouragement and praise (“David, you are good at cars”).

- If your client is having a hard time stopping self-harm, you can help them gently, such as keeping their hands from hitting their heads. Try to immediately switch it to another activity, but be prepared to keep from trying to harm yourself again. This approach should be used with the utmost care as there is a good chance that you will reinforce the unwanted behavior, or force the person to direct their aggression towards others.

- You can also set up a physical barrier that will prevent a person from harming themselves, for example:

- If your ward hits himself on the head, place your hand or a pillow under his arm.

- If he bites his hands, let him bite another object.

If your target starts hitting their head against hard surfaces, have a pillow or bolster ready to place under their head to soften the impact. Also in special stores you can order a soft coating for the floor and walls, which will minimize possible injuries.

Get help

If the situation is out of control, contact the relevant authorities for help.

Physical restraint

In a situation where self-harming behavior poses a serious threat to human health, it may make sense to consider the use of protective equipment such as knee pads, elbow pads and helmets. Clements and Zarkowska (2001) suggest that such defenses will be easier to abandon later on than physical restraint (when you yourself restrain the ward from self-harm). Anyway, physical restraint and protective equipment is a last resort, they should be used with extreme caution and only under the supervision of a specialist.

Anyway, physical restraint and protective equipment is a last resort, they should be used with extreme caution and only under the supervision of a specialist.

In addition to ethical and safety considerations, even if protective equipment and physical restraints are applied very carefully, their use can increase the incidence of self-injurious behavior (Howlin, 1998). These measures do not affect the behavior itself, so it is very important that your ward learn new skills in parallel that will help him add what he wants in more acceptable ways.

Resume:

- Eliminate toothache and other health problems

- Define the behavior function

- Help your client learn alternative ways of communicating so they can communicate their needs.

- Structure your child's environment, set a schedule, and make sure he gets enough opportunities for sensory stimulation throughout the day.

- Frequently reward your client when he behaves appropriately or refrains from self-harm

- Respond quickly to self-injurious behaviors by interrupting them (gently restraining the person from harming themselves, or putting up a physical barrier if necessary) and divert their attention to another activity.

- In extreme cases, call the emergency services

- If you find it difficult to cope with self-injurious behavior in your caregiver, it occurs systematically, and you do not know what to do, seek help from a specialist.

Translation: Marina Lelyukhina.

Original article: http://www.autism.org.uk/living-with-autism/understanding-behaviour/challenging-behaviour/self-injurious-behaviour.aspx

Why does a child hit himself?

- Tags:

- Parent lecture hall

- 3-7 years

- 7-12 years old

- small children

When a child hits himself, it always causes great anxiety in the parents. Externally, self-punishment manifests itself as a whim: the child is irritable, he can tensely pull his hair, or he can violently beat his head against the wall or floor. And although such behavior can be considered a childish prank, its main reason is improper upbringing.

What is the reason for this behaviour?

Self-punishment refers to aggressive behavior, its only difference is that this aggression is suppressed due to incorrect parental upbringing. As a result, aggressiveness has become passive.

As a result, aggressiveness has become passive.

And until this behavior is recognized and restructured, the child will retain the power of unspoken pain. As he gets older, he will look for solace in food, stealing, and other forms of “calming”.

The reasons for allowing a child to react in this way are varied and depend in part on his temperament. Let's consider each of them.

A child may hit himself in protest

If babies are completely subject to the will of their parents, then children from the age of 2 years begin to seriously resist submission. Protest itself is the quality of a leader, so the trait of such children is exactingness. It is difficult for such a child to refuse something to which, as it seems to him, he has an innate right.

Such a violent reaction is formed in response to the excessive severity of parents, the abundance of prohibitions and rules in education. If our will were repeatedly suppressed, then the direct expression of aggression towards the offender, as well as the desire for intimacy (for example, to ask for what is forbidden to him), would give rise to great fear in us.

Thus, the child struggles with his own humiliation and restriction of freedom by using force against himself.

Wrong punishment in this case: shout at the child, hit the child.

Result of punishment: baby cries even louder.

Effective mother's reaction: gently hold the child when he hits himself. Sit next to, calm, hug. In this situation, the most credible interpretation of the child's feelings will be. “Mom didn’t let me eat candy now, and you got really mad at mom. You can eat two at once after dinner.”

Note: to revise unnecessary requirements for the child, to remove some of the prohibitions. Learn to compromise.

The child may hit himself when he feels guilty

Another option is children, who differ from the first ones in a weak nervous system. These are children who grew up surrounded by parents who verbally limit children's opposition. Such parents often scold their children, hang labels, call offensive nicknames.

Consider the usual situation at home. The child broke the toy and is trying to fix it. He doesn't succeed, he gets angry and hits his ear. If a child often hears offensive words for some kind of oversight, he, doing something that his mother does not like, mentally scolds himself.

Patting on the ear is an unconscious reaction that communicates that the baby is hurt by being called names. You can recognize children belonging to this type by their behavior. When struck, the child does not rebel, unlike the first type. Crying occurs as a reaction to pain.

Wrong punishment in this case: lock in a room, ignore.

The result of the punishment: the child continues to beat himself.

Effective mother's reaction: relieve internal tension, offer something interesting. Mom's comment: "Is the toy broken? Nothing, my sun, do not be upset, I still love you. Even if mom is angry, she will always love you. Let's try to fix it together."

Note: Avoid excessive verbal criticism. Show love more often.

Show love more often.

A child may hit himself to get what he wants and feel his influence

Children manipulate their parents for several reasons: to get a portion of love and attention, to hide their tricks, and also to make their parents feel guilty and sorry for themselves.

Children are very talented observers, and most often the reason for children's manipulation lies precisely in the behavior of their parents. Parents of little manipulators are used to pleasing their beloved baby with might and main. Children's tears cause a feeling of guilt, and now we are already strenuously patronizing them, appeasing, fawning, becoming overly lenient in cases where we need to show firmness and consistency.

It is easy to figure out such a trickster: as a rule, the child strikes himself in such cases and watches the mother's reaction.

Wrong punishment: immediately change anger to mercy. The manifestation of attention and tenderness will only reinforce unwanted behavior in the child.