Why do people like conspiracy theories

Why people believe in conspiracy theories, with Karen Douglas, PhD

Kim Mills: Over the past year as COVID-19 rocketed around the world, conspiracy theories quickly followed. Last spring, dozens of cell phone towers were set a flame across Europe, amid conspiracy theories that the 5G towers were spreading COVID-19. In January, a Wisconsin pharmacist was charged with deliberately destroying hundreds of doses of the newly available COVID 19 vaccine because he believed a conspiracy theory that the vaccine would change human DNA. And some people are asserting that the virus itself was engineered by the Chinese.

These aren't the only conspiracy theories making inroads right now. A September Pew Research Center survey found that more than half of Americans have heard at least a little about QAnon, the complicated web of pro-Trump conspiracy theories that originated on the message board 4chan. In November, two candidates who voiced support for QAnon theories were elected to Congress.

So how do conspiracy theories like these get started and why do they persist?

Who is most likely to believe them and why? Is there any way to combat conspiracy theories once they're out there? And what are the consequences for individuals and societies when they spread? Welcome to Speaking of Psychology, the flagship podcast of the American Psychological Association that examines the links between psychological science and everyday life.

I'm Kim Mills. Our guest today is Dr. Karen Douglas, a professor of social psychology at the University of Kent in the UK. Dr. Douglas has spent more than a decade studying conspiracy theories, and she joins us to talk about their history, causes, and consequences. Thank you for joining us, Dr. Douglas.

Karen Douglas, PhD: Hi Kim. Thank you very much for your invitation. Hi everybody.

Mills: So let's start with a definition. That's always a good place to launch. What counts as a conspiracy theory? I gave a few examples in the introduction, but how do you define conspiracy theories in your research? What are their common characteristics?

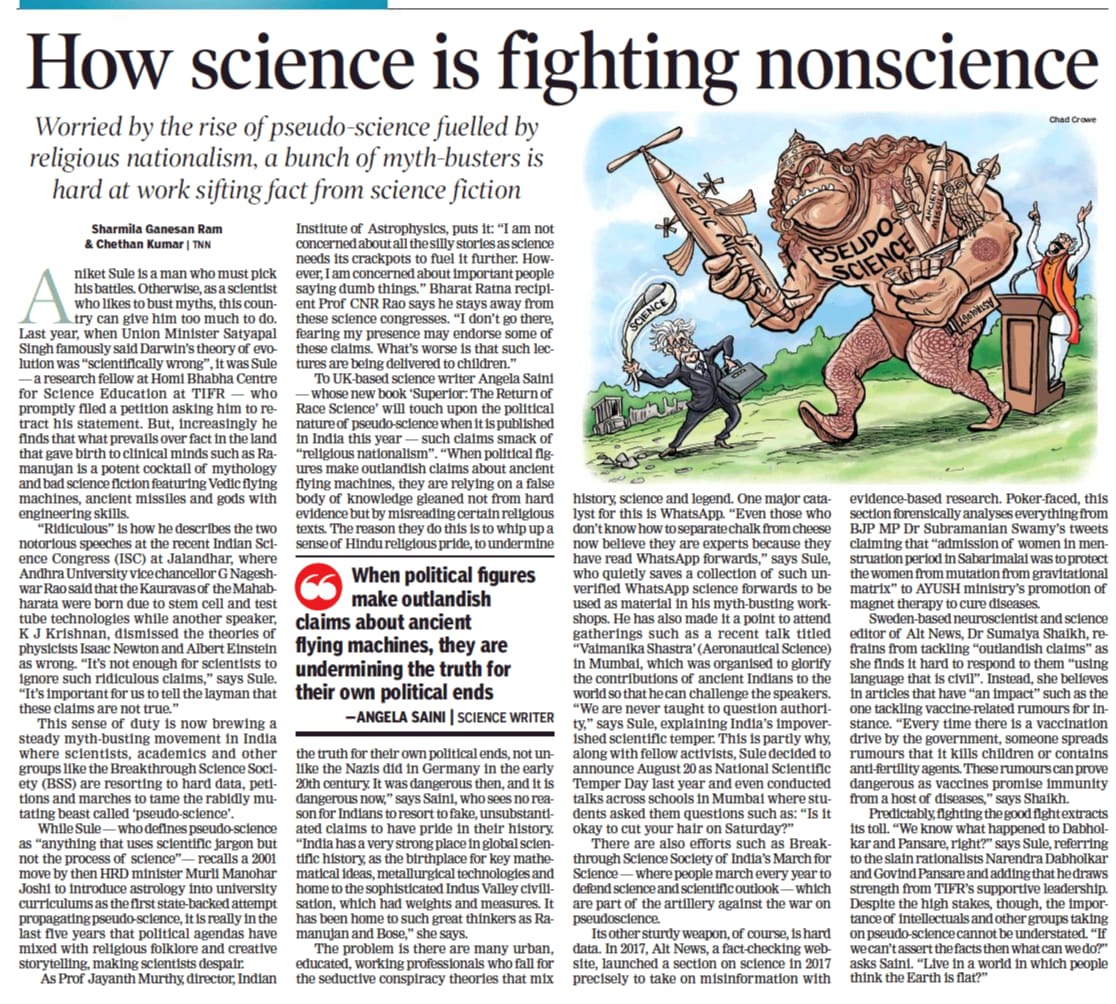

Douglas: Well, a conspiracy theory can normally be defined as a proposed plot carried out in secret, usually by a powerful group of people who have some kind of sinister goal.![]() So something to gain from what they're doing and they usually don't have people's best interests at heart. Usually, their own interests at heart.

So something to gain from what they're doing and they usually don't have people's best interests at heart. Usually, their own interests at heart.

Mills: Some people think that the belief in conspiracy theorists has been on the rise in recent years fueled by social media, but in a paper a few years ago, you concluded that wasn't necessarily true. Instead, you found that conspiracy theories have always thrived during times of crisis and social upheaval with examples going back as far as the burning of Rome while Nero was away, and that the last decade hasn't been particularly more conspiracy prone than the past. Can you talk about that and how do researchers measure this?

Douglas: Sure. Yes, it is definitely the case that the conspiracy theories have ways being with us. Believing in conspiracy theories and being suspicious about the actions of others is in some ways quite an adaptive thing to do. We don't necessarily want to trust everybody and trust everything that's happening around us. And so they have always been with us and to some extent, people are all, I guess you could call everybody a conspiracy theorist if you want to use that term at one point or another.

And so they have always been with us and to some extent, people are all, I guess you could call everybody a conspiracy theorist if you want to use that term at one point or another.

And so yeah, they've always been there. People have always believed in conspiracy theories. As far back as we can remember, people have been having these conspiracy beliefs and having these suspicions about the actions of hostile collectives of individuals. This is just the way that we are wired up to some degree. And in terms of how we measure the extent to which people believe in conspiracy theories, you can do this in a variety of different ways. And as a social psychologist now, we would normally measure a belief in conspiracy theories by simply asking people questions about the extent to which they endorse a particular idea or the extent to which they believe a particular statement is true.

And you can measure these sorts of beliefs on specific issues. So for example, if you want to know how much somebody believes in anti-vaccine conspiracy theories, then you can ask people to read a bunch of statements about anti-vaccine conspiracy theories. So for example, that the pharmaceutical companies are hiding information about vaccine efficacy and safety. And then you ask them how much they believe that statement or how much they agree with it, how much they think it's plausible. There are various different ways that you can do this. And another way to tap into what some would argue is an underlying tendency to just believe conspiracy theories more generally.

So for example, that the pharmaceutical companies are hiding information about vaccine efficacy and safety. And then you ask them how much they believe that statement or how much they agree with it, how much they think it's plausible. There are various different ways that you can do this. And another way to tap into what some would argue is an underlying tendency to just believe conspiracy theories more generally.

You can ask more general questions or ask people to rate the extent to which they believe in statements such as governments often hide secrets from people to suit their own ends. So more general notions of conspiracy like that. So we'll just ask participants to read these sort of segments and write the extent to which they agree with them. Usually on a scale from I strongly disagree to I strongly agree that kind of thing. And then usually what we will do is come up with an average conspiracy belief measure or score I suppose total for each individual. And then we'll look for associations between that kind of belief and various other psychological factors as well.

Mills: So the belief is generally, always out there. The conspiracies may change over time, but I'm wondering, have there been times in history that you've seen when conspiracy theories have spiked?

Douglas: Not necessarily, it's not something I really research in my own studies, but naturally a lot of people are very concerned at the moment that we're seeing a bit of a spike and believing conspiracy theories with the whole coronavirus situation and also in the USA with the recent presidential election. And I guess time will tell if conspiracy theories have I guess, been on the rise in this particular point in time compared to times in the past or times in the future.

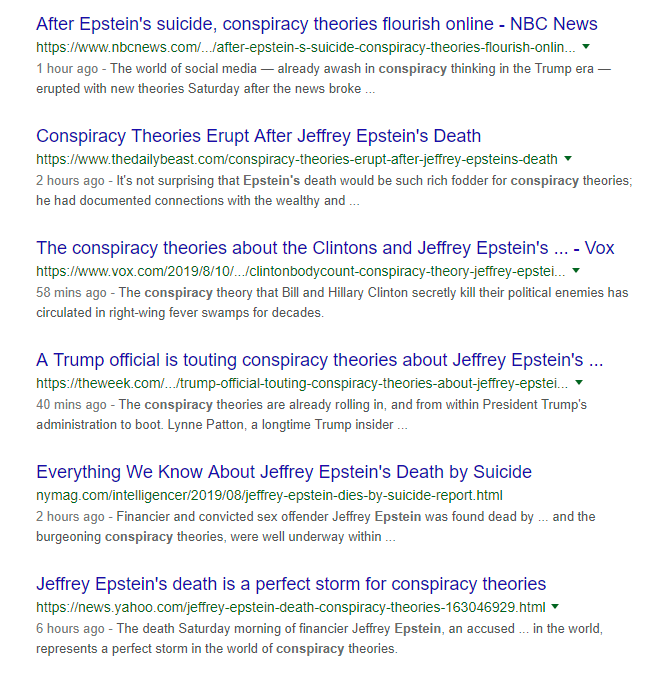

But there is definitely quite a lot of concern that conspiracy theories are on the rise. It's difficult for me to say whether or not they are, because I don't really have the data to support one way or another. But I think that it is definitely the case that even if we can't say for sure that social media has increased conspiracy theories, it's certainly changed the way in which people access this information, the ways in which they share this information, and also I feel that in many cases, for people who do have, I guess, an underlying tendency to believe in a particular conspiracy theory or conspiracy theories in general, it's much easier for people to find this sort of information now than it ever has been before.

And people can become consumed by this information. They can only seek out this information online. So they can go to particular sources, disregard other sources that contradict their views so that they end up, if anything, their attitudes about these particular alleged conspiracies rather sorry, can become even more polarized. So people's attitudes might become stronger. So I guess what I'm trying to say is that even if we don't have evidence that conspiracy theorizing has increased, and time will tell whether or not that's true. I do think that people's attitudes have become stronger as a result of interacting and sharing and consuming this information on social media and on the internet generally.

Mills: I'm just wondering, I think I read that there may have been a measurable increase in conspiracy theorizing around the turn of the 20th century because of the industrial revolution. And then also around the end of the Second World War in the beginning of the Cold War. Is that accurate?

Is that accurate?

Douglas: I think I have come across one study which suggests that that's the case. But yeah the evidence is really quite limited and only drawn from a particular type of sources, like letters to newspapers and that sort of thing. So it's really difficult to tell, but it does make sense to me that there would have been particular periods in history that conspiracy theories would have been more prominent. And personally, I think we might be in one of those periods right now.

Mills: Let's talk a little bit about the psychological factors that motivate people to believe in conspiracy theories. I know you've laid out in your research three areas that you call epistemic, existential and social motives. Can you explain what they are, what those terms mean?

Douglas: Yes, of course. We argue that people are drawn to conspiracy theories in order to satisfy or in an attempt to satisfy three important psychological motives. The first of these motives are epistemic motives. I guess in a nutshell, epistemic motives really just refer to the need for knowledge and certainty and I guess the motive or desire to have information. And when something major happens, when a big event happens, people naturally want to know why that happened. They want an explanation and they want to know the truth. But they also want to feel certain of that truth.

The first of these motives are epistemic motives. I guess in a nutshell, epistemic motives really just refer to the need for knowledge and certainty and I guess the motive or desire to have information. And when something major happens, when a big event happens, people naturally want to know why that happened. They want an explanation and they want to know the truth. But they also want to feel certain of that truth.

And some psychological evidence suggests that people are drawn to conspiracy theories when they do feel uncertain either in specific situations or more generally. And there are other epistemic reasons why people believe in conspiracy theories as well in relation to this sort of need for knowledge and certainty. So people with lower levels of education tend to be drawn to conspiracy theories. And we don't argue that's because people are not intelligent. It's simply that they haven't been allowed to have, or haven't been given access to the tools to allow them to differentiate between good sources and bad sources or credible sources and non-credible sources. So they're looking for that knowledge and certainty, but not necessarily looking in the right places.

So they're looking for that knowledge and certainty, but not necessarily looking in the right places.

The second set of motives, we would call existential motives. And really they just refer to people's needs to be or to feel safe and secure in the world that they live in. And also to feel that they have some kind of power or autonomy over the things that happen to them as well. So again, when something happens, people don't like to feel powerless. They don't like to feel out of control. And so reaching to conspiracy theories might, I guess, at least allow people to feel that they have information that at least explains why they don't have any control over this situation. Research has shown that people who do feel powerless and disillusioned do tend to gravitate more towards conspiracy theories.

The final set of motives we would call social motives and those refer to people's desire to feel good about themselves as individuals and also feel good about themselves in terms of the groups that they belong to. And I guess at the individual level, people like to feel... Well, they like to have high self-esteem. They like to feel good about themselves. And potentially one way of doing that is to feel that you have access to information that other people don't necessarily have.

And I guess at the individual level, people like to feel... Well, they like to have high self-esteem. They like to feel good about themselves. And potentially one way of doing that is to feel that you have access to information that other people don't necessarily have.

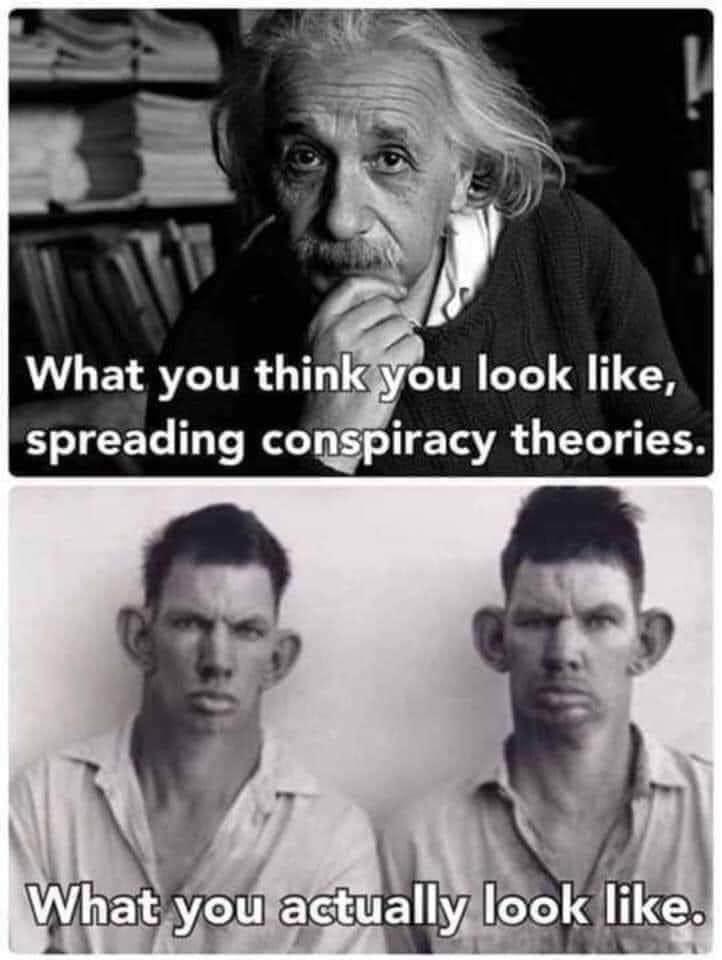

And this is quite a common rhetorical tool that people use when they talk about conspiracy theories, that everybody else is some kind of sheep, but that they know the truth. They have the truth. And having that kind of belief, I guess, feeling that you're in possession of information that other people don't have, can give you a feeling of superiority over others. And we have found, and others have shown as well that a need for uniqueness and a need to have, I guess, stand out from others is associated with belief in conspiracy theories.

And this happens at the level of the group as well. So people who have an overinflated sense of the importance of the groups that they belong to, but at the same time, the feeling that those groups are underappreciated, those kinds of feelings as well, draw people towards conspiracy theories, especially conspiracy theories about their groups. So in having those sorts of beliefs, you can maintain the idea that your group is good and moral and upstanding, whereas others are the evil doers out there who are trying to ruin it for everybody else.

So in having those sorts of beliefs, you can maintain the idea that your group is good and moral and upstanding, whereas others are the evil doers out there who are trying to ruin it for everybody else.

Those three main motives... Those three psychological motives, the epistemic, existential and social, it's possible to summarize, I guess, the psychological literature on conspiracy theories into those three motivations. So yeah, that's what we argue.

Mills: What role, if any, does narcissism play in belief in conspiracy theories? People who tend to be more narcissistic also believe in these theories as a means of getting the social capital?

Douglas: Yes, absolutely. That is true. And that's kind of what I was referring to. It's linked to the idea of need for uniqueness, as well. That's another, I guess, narcissistic notion that you have. You're in possession of information that other people don't have. You're different to other people and it makes you stand apart. But yes, narcissism at an individual level has been associated in quite a few studies now with belief in conspiracy theories.

But yes, narcissism at an individual level has been associated in quite a few studies now with belief in conspiracy theories.

And also this narcissism at the group level as well, so an over inflated sense of the importance of your own group. That kind of insecure feeling about your own group is also associated with belief in conspiracy theories. So yes, narcissism is one of those individual differences, variables that correlate with belief in conspiracy theories.

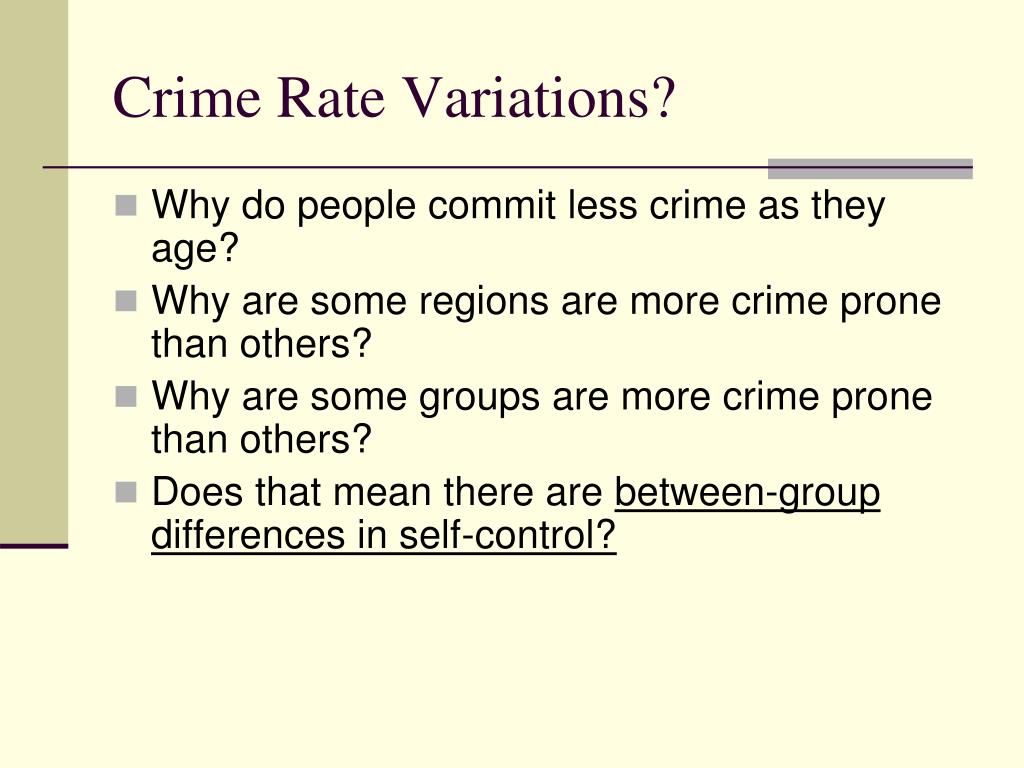

Mills: So a few moments ago, you talked about education level as being a factor. And I'm wondering what about other demographic categories such as age or gender? Do you see any associations between those and tendency to believe in conspiracy theories?

Douglas: Yes. In terms of age, we do. In our research, we generally find that older people believe in conspiracy theories less than younger people do. That tends to show up in most of the studies that we have run. So there's simply a correlation between conspiracy belief and age. That is a negative correlation, so the older you are, the less you believe in conspiracy theories. Or the other way around the younger you are, the more you believe in conspiracy theories. And that does tend to show up pretty much all of the time. In terms of gender, at least in the research that myself and my colleagues have conducted, we've never found any gender differences in terms of conspiracy belief. So as we measure belief in conspiracy theories using these psychological scales, we have never found that men believe more than women or women believe more than men or whatever. We've never found anything like that.

That is a negative correlation, so the older you are, the less you believe in conspiracy theories. Or the other way around the younger you are, the more you believe in conspiracy theories. And that does tend to show up pretty much all of the time. In terms of gender, at least in the research that myself and my colleagues have conducted, we've never found any gender differences in terms of conspiracy belief. So as we measure belief in conspiracy theories using these psychological scales, we have never found that men believe more than women or women believe more than men or whatever. We've never found anything like that.

I think one or two studies may have shown gender differences for specific conspiracy theories. I know of a recent study that, and I can't remember which direction it went in actually, but that showed that in terms of COVID-19 conspiracy theories, there was some kind of gender difference. But personally, I've never found that, which I think is very interesting and counter-intuitive in a way. Because if people think about the prototypical conspiracy theorist, again, if you want to use that term to describe people, then they do tend to think of a middle-aged white man, usually. And that may be the case for the prominent conspiracy theorists. Your well-known people who propagate these conspiracy theories, but not necessarily your everyday person who's consuming this information on the internet and deciding whether or not it's true. We don't really find those gender differences there.

Because if people think about the prototypical conspiracy theorist, again, if you want to use that term to describe people, then they do tend to think of a middle-aged white man, usually. And that may be the case for the prominent conspiracy theorists. Your well-known people who propagate these conspiracy theories, but not necessarily your everyday person who's consuming this information on the internet and deciding whether or not it's true. We don't really find those gender differences there.

Mills: That's really interesting. I mean, because it is when we just had this overrun of the U.S. Capitol here in Washington and it looked like there were a lot of younger and middle-aged men out there. I mean, certainly there were women involved, but that was the sense. And of course that is the conspiracy theory that the Trump election was stolen.

Douglas: Yes. Yeah, that's true. That's extremely interesting. And of course I was watching this on the news as well and thinking very much the same thing. But I think that there probably is a difference in the person who sits at home and reads this information on the internet and then decides whether or not it's true and the individuals who are prepared to actually go and storm a building or to go out and actively cause trouble based on these conspiracy beliefs. So there's probably a lot going on there, but in terms of the way we measure belief in conspiracy theories, we just don't, with these sorts of gender differences that might seem obvious, don't seem to play out really in the research that we do on the everyday population, I suppose.

But I think that there probably is a difference in the person who sits at home and reads this information on the internet and then decides whether or not it's true and the individuals who are prepared to actually go and storm a building or to go out and actively cause trouble based on these conspiracy beliefs. So there's probably a lot going on there, but in terms of the way we measure belief in conspiracy theories, we just don't, with these sorts of gender differences that might seem obvious, don't seem to play out really in the research that we do on the everyday population, I suppose.

Mills: Another of your studies found that people who believe in one conspiracy theory are more likely to believe in others, even when those theories directly contradict each other. So for instance, the more your participants believe that Princess Diana faked her own death, the more they also believe that she was murdered. And of course, that doesn't make any sense. Can you help explain that?

Douglas: Yeah, of course. Yes. We feel that is a very interesting finding. Obviously we kind of, I guess, started from the point that in the literature it's often been found that if people believe in one conspiracy theory, then they're likely to believe in others. So in other words, there's something that kind of holds these beliefs together. So we were interested to find out, well, what is this? This underlying belief system or underlying attitude that might mean that these conspiracy beliefs are held at the same time, even if they do contradict one another.

Yes. We feel that is a very interesting finding. Obviously we kind of, I guess, started from the point that in the literature it's often been found that if people believe in one conspiracy theory, then they're likely to believe in others. So in other words, there's something that kind of holds these beliefs together. So we were interested to find out, well, what is this? This underlying belief system or underlying attitude that might mean that these conspiracy beliefs are held at the same time, even if they do contradict one another.

So we set to do these studies, and so we asked participants in these studies to rate the extent to which they agree with different conspiracy theories. One, for example, that Princess Diana was assassinated by the royal family. Another one that she was assassinated by MI5, nothing to do with the royal family or others, also, but crucially, I think, one that she was assassinated and is dead. And another, that she was helped to fake her own death and that she's sort of living it up somewhere on an island having a great time. So basically, it's not possible to be dead and alive at the same time. And also, participants-

So basically, it's not possible to be dead and alive at the same time. And also, participants-

Mills: Unlike Schrodinger's cat.

Douglas: Yeah, well, that's it. We thought people would not entertain these two conspiracy theories at the same time, but it turned out that they did, or at least they were prepared to entertain the idea that both of those things might be true.

But we also measured the extent to which people believed in, I guess, an underlying conspiracy theory that something just isn't right. Something's up and something is being covered up. And what we found was that some people did indeed endorse these contradictory conspiracy theories, or again, at least were likely to entertain those two ideas at the same time. But once we also took into account the extent to which they believed that there was just something up, then that relationship actually disappeared. So it was the relationship between the contradictory beliefs was explained by the, I guess, underlying belief that just something is being covered up.

So you can explain why people will entertain these contradictory ideas, because both of those ideas are consistent with the underlying idea that there's just something not quite right. So it's not necessarily to say that they will definitely believe that Princess Diana is dead and at the same time believe that she's still alive, but they'll be happy to entertain the idea that those two things are possible, as long as they also entertain the belief that there was just something that wasn't right about those events.

Mills: Yeah. That helps explain it, at least a little bit. Well, what makes a conspiracy theory catch on and have staying power? Are there certain types of theories that are stickier than others or some that are more enduring? Like the earth is flat has been around since forever. So are there characteristics that make them stickier?

Douglas: That's not something that I've done research on myself, to be honest, but I think it's a fascinating question. It's very true that some conspiracy theories stand the test of time and others just disappear. I think that there must be certain features of conspiracy theories, the ones that last and the ones that don't. I don't personally know exactly what they are, but I guess one thing that tends to be very, very common is that the event is very, very large. The event that is explained by the conspiracy theory is very, very large and important and usually involving something of great political or social significance. A lot of other conspiracy theories that you might come across just sort of disappear. I guess a lot of the time we just don't really know why they don't catch on. But plenty of them do. Yeah. It's a really interesting question.

It's very true that some conspiracy theories stand the test of time and others just disappear. I think that there must be certain features of conspiracy theories, the ones that last and the ones that don't. I don't personally know exactly what they are, but I guess one thing that tends to be very, very common is that the event is very, very large. The event that is explained by the conspiracy theory is very, very large and important and usually involving something of great political or social significance. A lot of other conspiracy theories that you might come across just sort of disappear. I guess a lot of the time we just don't really know why they don't catch on. But plenty of them do. Yeah. It's a really interesting question.

Mills: It's a line of research for you to pursue.

Douglas: Yeah, yeah. Oh, yeah. There definitely is. Yeah. I think that other researchers have started to ask these sorts of questions, and I have tried myself to, I guess, not taxonomize, but sort of almost, I guess, not even categorize conspiracy theories, but try to isolate some of these features. But it's actually very difficult, because there are so many of them about so many different events.

But it's actually very difficult, because there are so many of them about so many different events.

And you pointed out the flat earth conspiracy theory, which has been around forever but kind of died away for a long time and then in recent years just seems to have gotten popular again, and I do find it quite difficult to explain that. I mean, I have a theory about that conspiracy theory, that just generally people are becoming less trustful of science and scientists at the present time, which is why we might be seeing these sorts of ideas making a bit of a comeback. But yeah, no. I think it's a really, really fascinating question, because it's not that even though some of them disappear, they go away, but then they come back again or come back again in a different form or certain conspiracy theories about particular things, like say anti-vaccine or health-related conspiracy theories can kind of reinvent themselves for new things that happen, like 5G conspiracy theories about people getting sick from [inaudible 00:25:10] masks and things like that.

So these sorts of conspiracy theories have always been there. They kind of mutate, I suppose, if you like. They change. But yeah, I think it is a really fascinating question and one that I can't, as a social psychologist, can't really answer very well, unfortunately.

Mills: Is there any way to effectively debunk a conspiracy theory once it's out there? I mean, can you just present the facts? Like you talked about the anti-vaxxers, the fact that the Lancet article that led to a lot of beliefs that children were becoming autistic as a result of vaccines. And then it turned out that that article was bogus. It was based on faulty data and it was retracted, and yet some people are still hanging on to that. So is there a way to stop these theories from continuing to swirl?

Douglas: Yes. There are ways to do this, but of course, it's extremely challenging. It's very, very difficult. Once these conspiracy theories are out there and people believe them, then sometimes people can very, very strongly hold on to these beliefs and defend them very, very strongly as well. And once these attitudes are very, very strong, of course, from other areas of psychology we know that attitudes that are very strongly held are difficult to dispute, I guess. Difficult to change. It's very difficult to change these sorts of attitudes.

And once these attitudes are very, very strong, of course, from other areas of psychology we know that attitudes that are very strongly held are difficult to dispute, I guess. Difficult to change. It's very difficult to change these sorts of attitudes.

And so, yes, it is a challenge, but there are things that that can be done. And a lot of research that, especially in very, very recent years as well, has started to come out in terms of how do you address misinformation? How do you address conspiracy theories? And giving people the facts does work under certain situations. In some of our own research, we've actually found that it's quite effective to provide people with factual information, provide people with the facts. And this was particularly about vaccines before they're exposed to conspiracy theories, and then the conspiracy theory fails to gain traction. But once the people have been exposed to the conspiracy theory, they're giving them the, I guess,... Sorry, the appropriate or correct information afterwards doesn't really work. So, others have taken this information and have started to look at ways to inoculate people against misinformation and to inoculate people against conspiracy theories and fake news and all sorts of other things, which seems to be working as well. So, in other words, you give people either the correct information or some piece of weak misinformation before they're exposed to the worst of it, then that helps them to be able to resist it.

So, others have taken this information and have started to look at ways to inoculate people against misinformation and to inoculate people against conspiracy theories and fake news and all sorts of other things, which seems to be working as well. So, in other words, you give people either the correct information or some piece of weak misinformation before they're exposed to the worst of it, then that helps them to be able to resist it.

There are other techniques that people have used, that researchers have used, as well, and just to give you one other example, some researchers have looked at the idea of presenting people with a pre-warning or a forewarning that they might be exposed to misinformation. And if people believe that information that they might receive could be misleading, and they have that information up front, then that can sometimes help them to resist the misinformation as well. Now, I think these are all really, really valuable tools, but of course, sometimes the misinformation is all ready out there so it's difficult to get to people beforehand. So, then, you have to resort to, I guess, traditional debunking techniques, such as going in with consistent, strong counter arguments.

So, then, you have to resort to, I guess, traditional debunking techniques, such as going in with consistent, strong counter arguments.

But I think that these other techniques provide real opportunities to help people to resist conspiracy theories in general that they might come across in the future. So, if you give people these sorts of, I guess, ways to critically think about information and think, "Well, okay, I could be exposed to misinformation. That misinformation is out there, so I'm going to be on the lookout for it," then it might actually help people to resist it when they come across it next time. If that makes sense.

Mills: Yeah. It sounds like the techniques that they're trying to use right now with the COVID-19 vaccines, telling people up front that if you happen to be particularly allergic, you might have a reaction. This is what to expect. And yet, it's like a game of whack-a-mole because they talk about all of this and they're trying to be as transparent as possible, and yet, along comes somebody who says that the mRNA that's involved in this is actually going to change the DNA in your body. How do you fight that?

How do you fight that?

Douglas: Yeah. It is very, very difficult, and there are new conspiracy theories all the time. It is exactly like that game. You've got one and then you're constantly trying to hit another one away. It is very, very challenging. There's a lot out there, a lot going on out there.

Mills: And of course, this is all complicated by the fact that sometimes conspiracies do exist and sometimes people may have deep-seated, valid reasons to distrust authority. So, for example, public opinion polls have found that Black Americans are less likely to say they'll take the COVID vaccine and more wary of its safety because they have a long history of being abused and mistreated by the medical establishment. So, is there a way for people to balance this awareness with a healthy skepticism of conspiracy theories?

Douglas: Yes. Again, this is extremely challenging, and you're absolutely right, that some people have very good reasons to be suspicious of these sorts of things because of past events. And so, the challenge becomes even greater. And I don't know the solution to this, apart from the fact that people who are attempting to fight the misinformation will need to be sensitive to these concerns and perhaps be more targeted in their efforts to debunk misinformation, being sensitive to these historical events as well.

And so, the challenge becomes even greater. And I don't know the solution to this, apart from the fact that people who are attempting to fight the misinformation will need to be sensitive to these concerns and perhaps be more targeted in their efforts to debunk misinformation, being sensitive to these historical events as well.

So, it can't necessarily be a one size fits all approach to misinformation, just can't be because everybody's circumstances are different, and we know that different communities feel differently about vaccines and various other things as well, for very good reasons. So, that, of course, is a huge challenge for anybody trying to deal with potential misinformation about vaccines and other things, but also, yeah, particularly with COVID, a reluctance to take the vaccine.

Mills: So, what aspects of conspiracy theory are you looking at today? What's your research heading toward?

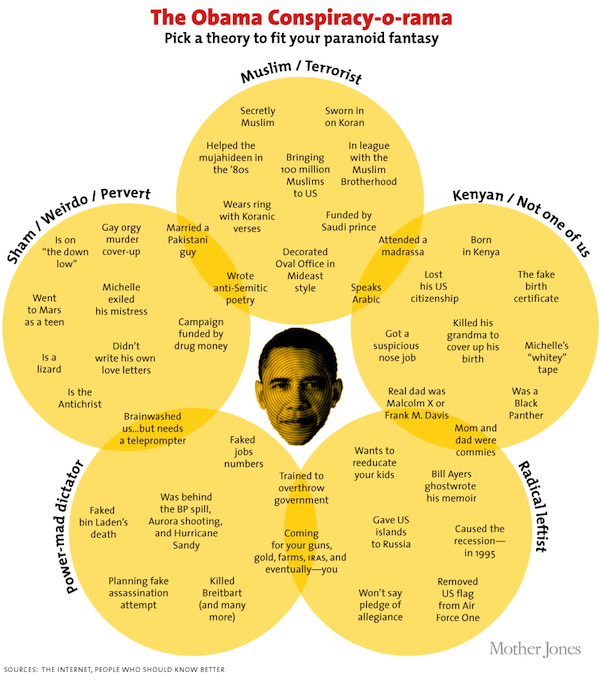

Douglas: Quite a few things going on at the moment, actually. I'm really interested in, I guess, the deliberate use of conspiracy theories as a political device. So, I've been doing some research, I guess, looking at how people perceive others who seem to use conspiracy theories, and whether or not they see those actions as intentional or deliberate, and also what the effects are of that. I've also been interested in the term conspiracy theory itself and the term conspiracy theorist and how people use those terms, whether they use them to, I guess, specifically put down other people's ideas, or if they simply use these terms when they just don't believe... that they don't believe a particular idea, and also the effects of these terms on whether or not someone will actually believe something.

I'm really interested in, I guess, the deliberate use of conspiracy theories as a political device. So, I've been doing some research, I guess, looking at how people perceive others who seem to use conspiracy theories, and whether or not they see those actions as intentional or deliberate, and also what the effects are of that. I've also been interested in the term conspiracy theory itself and the term conspiracy theorist and how people use those terms, whether they use them to, I guess, specifically put down other people's ideas, or if they simply use these terms when they just don't believe... that they don't believe a particular idea, and also the effects of these terms on whether or not someone will actually believe something.

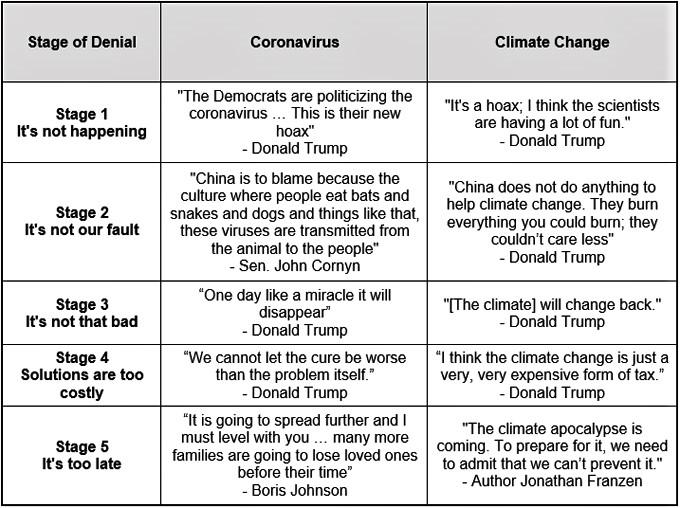

What else have I been doing? Oh, quite quite a few things going on. I've been writing quite a bit about COVID-19 conspiracy theories, and also, quite generally, my research is focused a lot on the consequences of believing in conspiracy theories as well. So, in different areas like in vaccines, climate change, politics in various different domains, specifically what impact do conspiracy theories have on people's attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. So, I've been doing a lot on that sort of thing.

So, in different areas like in vaccines, climate change, politics in various different domains, specifically what impact do conspiracy theories have on people's attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors. So, I've been doing a lot on that sort of thing.

Mills: Well, it's an amazing area for a scrutiny, and appreciate the work that you're doing here and helping us to better understand some of the ways that people's minds work. So, thank you so much for joining us today, Dr. Douglas.

Douglas: Well, thank you. It's been a pleasure.

Mills: If you'd like to learn more about psychological research on conspiracy theories and other types of misinformation, check out the Monitor on Psychology, the magazine of the American Psychological Association. You can find it at www.apa.org/monitor. You can find previous episodes of Speaking of Psychology on our website at www.speakingofpsychology.org, or wherever you get your podcasts. If you have comments or ideas for future podcasts, email us at speakingofpsychology@apa. org. That's speakingofpsychology, all one word, @apa.org. Speaking of Psychology is produced by Lea Winerman. Our sound editor is Rob Aneiva. Thank you for listening to the American Psychological Association. I'm Kim Mills.

org. That's speakingofpsychology, all one word, @apa.org. Speaking of Psychology is produced by Lea Winerman. Our sound editor is Rob Aneiva. Thank you for listening to the American Psychological Association. I'm Kim Mills.

Why We Fall for Conspiracy Theories

By Christina Georgacopoulos | February 2020

How do conspiracies spread, and why do we believe them?

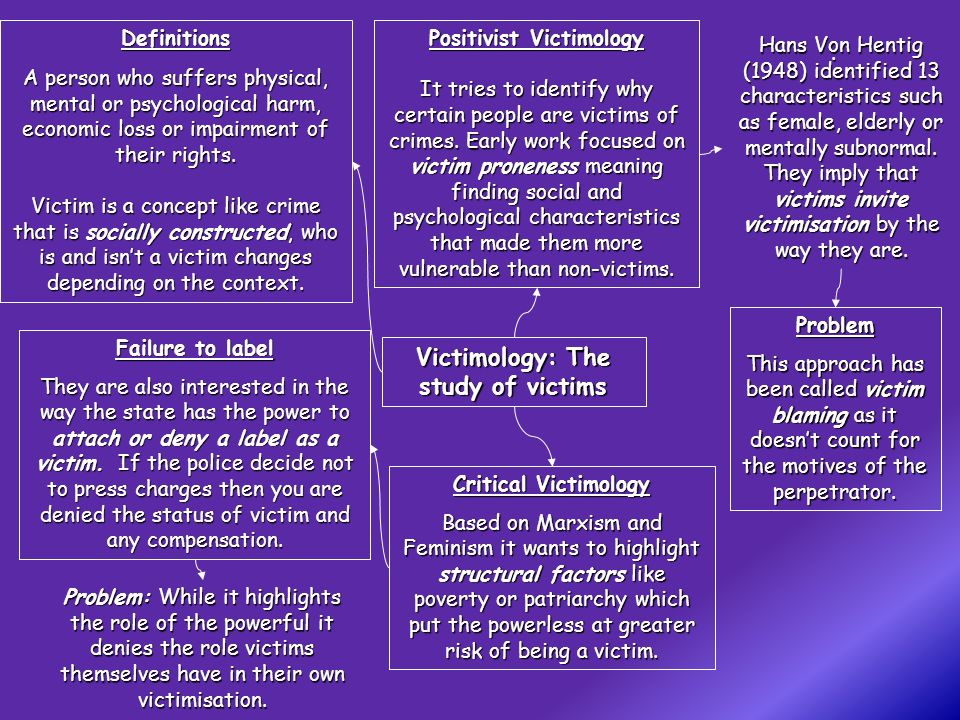

What are conspiracy theories?The “paranoid style” of thinking in American politics has a long history. The periodic emergence of narratives about clandestine, malevolent actors secretly plotting political and social calamities influences policy debate about vaccine regulations, genetically-modified food labeling, foreign diplomacy and domestic elections. But conspiracy theories are not the delusions of paranoid minds -- recent polls show that more than 50 percent of Americans believe in one conspiracy or another. What makes conspiracies an interesting phenomenon is that they have loyal followers and are believed, more or less, by ordinary people.

What makes conspiracies an interesting phenomenon is that they have loyal followers and are believed, more or less, by ordinary people.

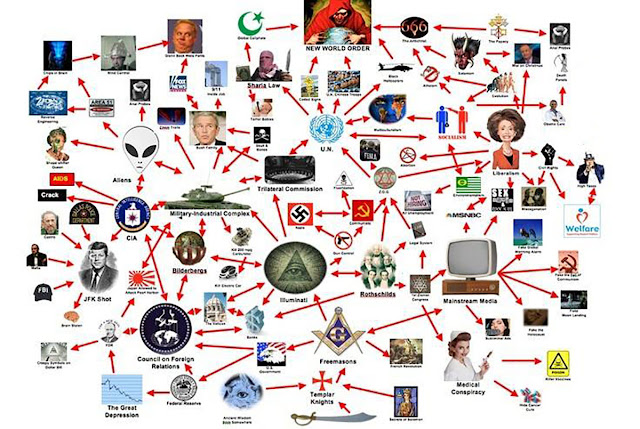

A few common characteristics of conspiracy theories are that, first, they locate the source of unusual social and political phenomena in unseen, intentional and malevolent forces. Second, they often interpret political events in terms of the struggle between good and evil. And third, most conspiracy theories suggest that mainstream reporting of public affairs is a ruse or an attempt to distract the public from a true source of power.

- According to a study conducted by the University of Chicago:

- 19% of Americans believe the government was behind the 9/11 attacks;

- 25% believe the 2008 recession was caused by a small cabal of Wall Street Bankers;

- And 11% believe the government mandated a switch to compact fluorescent lightbulbs in government buildings because “they make people obedient and easier to control”

Conspiracy theories are captivating because they provide explanations for confusing, emotional and ambiguous events especially when official explanations seem inadequate.

Conspiracies provide structured narratives of events that comport with how some people process information. Conspiratorial beliefs flourish at the extremes of the political spectrum. Political extremism fosters conspiricism due to the highly-structured thinking style of engaged individuals who construct narratives that make sense to them based on prior beliefs. Some argue that “conspiracy theories are for losers,” that they are tools used by the powerless to attack and defend against the powerful.

Finally, some people simply prefer “Manichean” narratives, which are common in religious and populist political rhetoric. Manichean narratives often attribute the source of unexplainable or extraordinary events to unseen, intentional forces, and tend toward melodramatic understandings of events as a struggle between good and evil.

Although conspiracies are frequently outlandish and implausible assertions, their power lies in the fact that they confirm what people want to believe.

People naturally try to make sense of their world. Motivated reasoning is a psychological phenomenon that describes how people rely on biased cognitive processes while assessing, constructing and evaluating beliefs. Prior beliefs and attitudes “anchor” the evaluation of new information. These motivations, or biases, affect our perceptions of an issue, and how we assign blame or causality. An important point is that the motivation to be accurate is often the driving factor while reasoning new information, however, accuracy-goals are in constant tension with the motivation to arrive at a particular conclusion that confirms one’s prior beliefs. Partisan and emotionally evocative messaging often overwhelms to desire to be accurate.

Partisan and emotionally evocative messaging often overwhelms to desire to be accurate.

Motivated reasoning occurs via three distinct processes:

- Confirmation Bias or Biased Assimilation: A person is more likely to seek out information that is consistent with their pre-existing beliefs, while simultaneously avoiding incompatible information that may challenge their beliefs.

- Disconfirmation bias: A person will spend more time and effort denigrating and counterarguing opposing arguments.

- Attitude-congruence bias: Those who hold a definite position on an issue tend to see supporting arguments as stronger than opposing arguments

Some researchers propose that the “motivational view” can be explained by psychology, that people draw self-serving conclusions not because they want to, but because certain conclusions seem more plausible given their prior beliefs and expectations.

The influence of motivated reasoning is more pronounced for highly-engaged individuals for whom an issue is most important. The more knowledge an individual accumulates about a particular issue, the more likely they are able to effectively argue against conflicting information or avoid conflicting information altogether.

Check out this video on conspiracy theories and fake news by Retro Report: Conspiracy Theories and Fake News from JFK to Pizzagate

Why people believe in conspiracy theories and conspiracy theories

Bill Gates, vaccines, nanochips, 5G towers and their "link" to COVID-19. We explain what (or who?) makes people believe in the most ridiculous conspiracy theories, and why each of us is a bit of a conspiracy theorist

Audio version of the material:

Your browser does not support audio player .

Now you can not only read but also listen to RBC Trends materials. Search for and subscribe to the Sounds Like a Trend podcast on Apple Podcasts, Yandex.Music, Castbox, or any other platform where you listen to podcasts.

Video: lecture by psychologist Vladimir Spiridonov on conspiracy theories

Conspiracy theories in the media

In early May 2020, Nikita Mikhalkov, as usual, appeared on the air of Rossiya 24. His author's program "Besogon TV" is released on the channel. The director's voice sounded uneasy. As Mikhalkov managed to find out, billionaire Bill Gates, under the guise of coronavirus vaccines, intends to implant some nanochips in people in order to control humanity. And the technology for this grand plan is patented under the number 666, the number of the Antichrist. There is a conspiracy. A similar story was shown on Channel One, on the air of "Man and the Law." Also Bill Gates, who is behind the coronavirus pandemic and is preparing the world for mass chipization.

At the same time, another "source" of the coronavirus was found - 5G towers that mysteriously irradiate people. This theory is already the brainchild of the Internet, not television. For example, it was broadcast on her Instagram with 7 million subscribers by the host and former participant of Dom-2 Victoria Bonya.

Themes of conspiracies in the Russian media over the past decade have become several times greater.

Popular conspiracy theories in the Russian media. Research by Medialogy and Vedomosti, 2018

Russians are actively told about the conspiracy of historians against Russia, the secret world government and freemasons, the danger of GMOs and vaccines, about the fact that HIV and AIDS do not exist, about the flat Earth and that Americans have not been to the moon. Now Bill Gates, 5G towers and the coronavirus have been added to this.

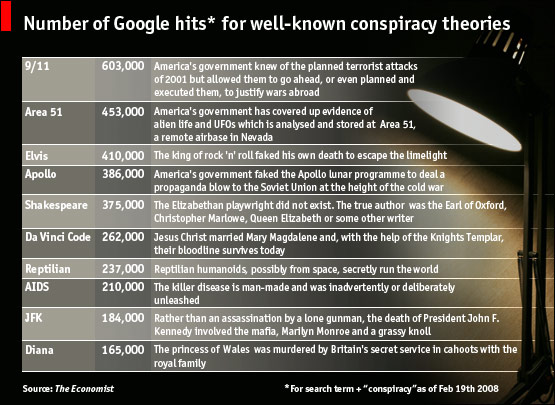

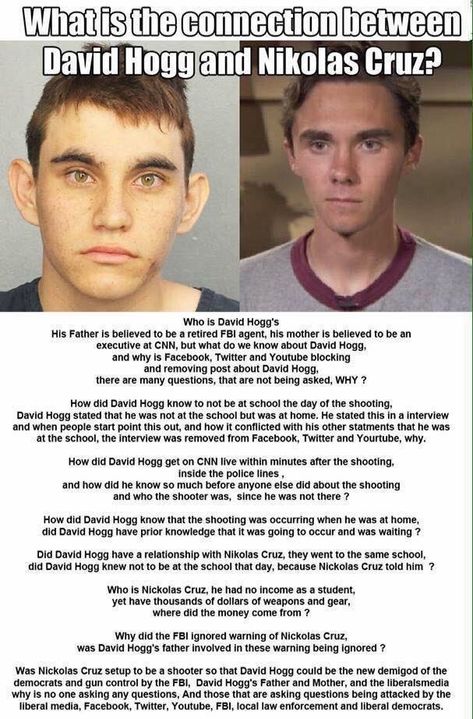

In the US, conspiracy theories are also flourishing. Unless fewer people believe in the "lunar conspiracy" - after all, a matter of national pride. Otherwise, the stories are similar: vaccines and HIV are a conspiracy of pharmaceutical companies, global warming is a conspiracy of climatologists, Kennedy was killed by special services, they also staged the September 11 attack and massacres in schools.

Otherwise, the stories are similar: vaccines and HIV are a conspiracy of pharmaceutical companies, global warming is a conspiracy of climatologists, Kennedy was killed by special services, they also staged the September 11 attack and massacres in schools.

The story about Bill Gates and chipping under the guise of vaccines against COVID-19 in the United States also sold well - according to the latest polls, 44% of members of the Republican Party believe in it.

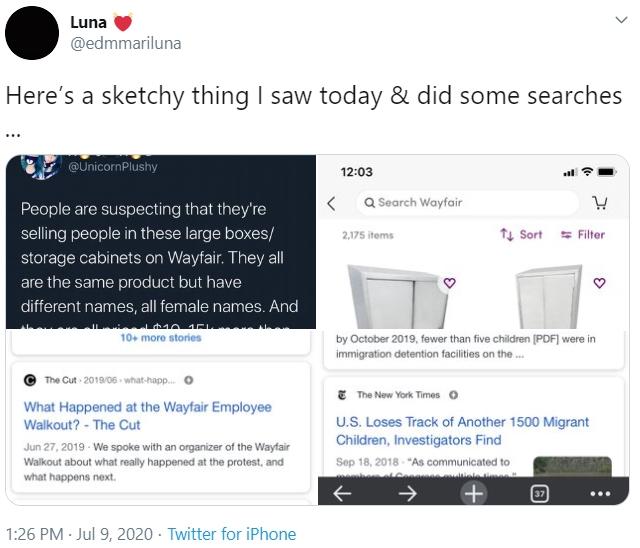

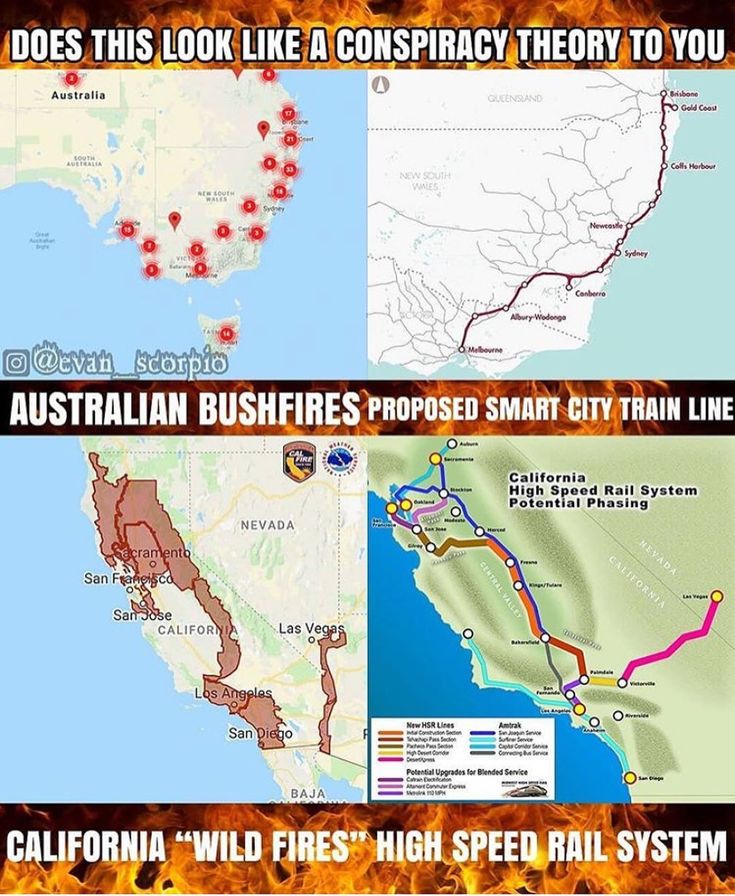

Conspiracy theory scheme linking 5G towers, vaccinations, the Spanish flu pandemic, the Third Reich, the Watergate scandal, the invention of radio, and even a tweet by President Donald Trump with the cryptic word covfefe

conspiracy," only sounds more scientific. True, the owners of such a picture of the world prefer not to call themselves conspiracy theorists. And they rarely talk about conspiracies. Now the word "skeptic" is in vogue.

The problem is that such views—sometimes naive, sometimes strange, sometimes wild—often have consequences. Some people think that 5G towers really spread the coronavirus, and they go to burn them. Others refuse to vaccinate their children, and so massively that the WHO for the first time included it in the list of threats to human health. With the advent of a vaccine for COVID-19, this could become even more of a problem.

Some people think that 5G towers really spread the coronavirus, and they go to burn them. Others refuse to vaccinate their children, and so massively that the WHO for the first time included it in the list of threats to human health. With the advent of a vaccine for COVID-19, this could become even more of a problem.

The gray area between facts and conspiracy theory

It is vain to think that conspiracy is about some other, not the smartest people and definitely not about you and your environment. A VTsIOM poll from 2018 showed that 67% of Russians believe in a secret “world government” (versus 45% in 2014), 68% of them with higher education.

Conspiracy theories are not one big story that you can either believe or not believe. Rather, it is a set of interpretations of individual facts , each of which can occupy any place on the scale from obvious absurdity to scientific data. Someone may consider the enslavement of humanity by aliens incredible, but oppose vaccination - or vice versa.

There is a big gray zone between scientific facts and explicit conspiracy theory, within which for each of us there is a completely logical explanation of the world, which to someone else will seem conspiracy theories.

Our picture of the world is influenced by rather ancient settings of the brain and psyche:

When they begin to fail, for example, against the background of stress due to external circumstances, thinking runs the risk of becoming more conspiratorial. Let's see how this happens.

Intention Detector

Take a look at the video:

Heider and Simmel Experiment

It's hard not to notice the history here. This is because the brain automatically sees not just geometric shapes, but characters and their intentions. Rob Brotherton, author of Incredulous Minds: What Conspiracy Theories Attract Us to, called this cognitive bias an intention detector.

Most of us clearly see that the big triangle is a clear abuser. In the original study, which was conducted in the 1940s, only one subject described what he saw in purely geometric terms. The rest talked about people, about characters.

In the original study, which was conducted in the 1940s, only one subject described what he saw in purely geometric terms. The rest talked about people, about characters.

Another study was done with the same animation in 2017 — people who highly rated the ability of action figures to act consciously were also more likely to perceive the world as full of motives, intentions, and to believe in conspiracy theories.

Rob Brotherton's own study two years earlier was similar. The subjects were read sentences, for example, "She stepped on the dog's tail", "He burned down the house", "She burst the balloon". The sentences could be understood in two ways, depending on the intention - stepped on the dog's tail on purpose or accidentally, without noticing. And again, the more people saw intention in these actions, the more they believed in conspiracy theories.

Fear of uncertainty

The brain immediately grasps the essence of what is happening. The first, instantaneous impression of a scene is formed in less than one heartbeat and includes automatic inferences about the thoughts, feelings, and intentions of objects. We are programmed to perceive moving triangles as rivals, although we understand that these are just shapes on the screen.

The first, instantaneous impression of a scene is formed in less than one heartbeat and includes automatic inferences about the thoughts, feelings, and intentions of objects. We are programmed to perceive moving triangles as rivals, although we understand that these are just shapes on the screen.

Colin Ellard, cognitive neuroscientist and author of Habitat, attributes this to evolutionary selection. There is too much information around to analyze in detail all the elements of an average scene. The brain, compared to a computer, processes data very slowly. Over millions of years, I had to learn to predict what this or that scene means, based on previous experience. Ignorance led to death.

Uncertainty makes us uncomfortable.

This is because in the evolutionary past certainty meant life and uncertainty meant death. The brain and behavior are sharpened in order to minimize uncertainty in any circumstances, to make the world understandable. Neuroscientist Bo Lotto writes about this in his book Refraction. The science of seeing differently. At its most basic level, the brain recognizes lines, shapes, silhouettes, and faces; at its highest, it searches for meanings and creates stories.

Neuroscientist Bo Lotto writes about this in his book Refraction. The science of seeing differently. At its most basic level, the brain recognizes lines, shapes, silhouettes, and faces; at its highest, it searches for meanings and creates stories.

Story Generator

Narrative is a set of stories that helps to cope with the unknown and the complexity of the world. These narratives form our picture of the world. For a long time, myths and religious texts were the source of narratives. Later they were joined by secular culture: literature, art, cinema. The same narratives can be found in Bible stories and superhero movies. The evolutionary task of narratives is not to describe the world with scientific precision, but to explain what to do in order to avoid threats and survive.

If the facts contradict our picture of the world, then so much the worse for the facts.

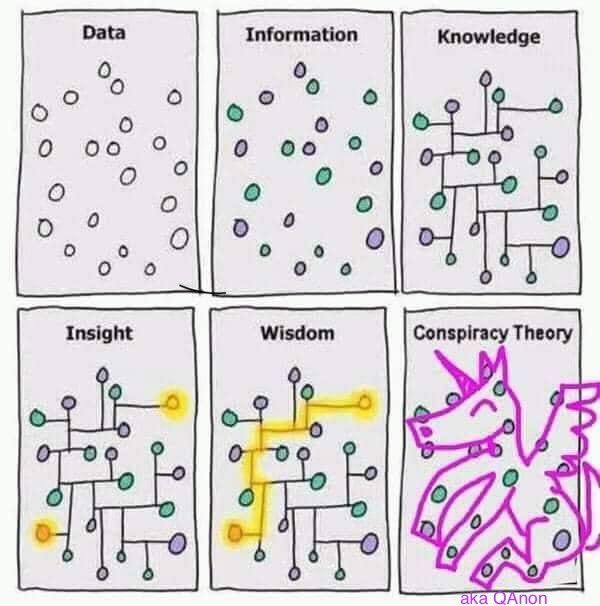

Thinking patterns like pattern recognition and storytelling make us susceptible to conspiracy theories. Rachel Runels, a conspiracy theorist, put it this way: “Patterns instead of noise. Narratives instead of facts.

Rachel Runels, a conspiracy theorist, put it this way: “Patterns instead of noise. Narratives instead of facts.

Another important function of narratives is that they unite. People are attracted to stories. We love to listen to them, we love to tell them. Moreover, when people listen to or watch the same story, their brain activity is synchronized. Culture is built on stories, values arise around them. Stories help us learn and guide our decisions.

People have needs to make sense of what is happening in other people as well. According to Runels, meaningful questions bring people together, such as "Why am I suffering?" This question can be answered like this: "I suffer because we all suffer." Or like this: "The cause of my suffering is myself." Conspiracy theories offer a different narrative: "The cause of my suffering is Them."

Distrust of strangers

“They” means “strangers”. This narrative resonates well with another of our ancient fears—invasion, threats from others. In social psychology, there is a hypothesis that we have formed a special adaptive mechanism - a "detector of dangerous coalitions".

In social psychology, there is a hypothesis that we have formed a special adaptive mechanism - a "detector of dangerous coalitions".

In the days of hunter-gatherers, hostile coalitions were common and a very real threat to survival. So being suspicious of outsiders or stronger groups is an understandable strategy. Our ancestors learned to pick up social signals about potentially dangerous coalitions. This feature of the human psyche is activated by conspiracy theories.

Some fear an immigrant invasion, others fear a reptilian invasion, and still others fear an invasion of Microsoft nanochips disguised as vaccines. This same fear of others is at the heart of the eternal theme of the Jewish conspiracy: "Zionist Occupation Government", "Protocols of the Elders of Zion" and medieval stories about Jews eating Christian babies.

Conspiracy thinking in an unstable world

Conspiracy theories tell us a lot about those who broadcast them. They say no less about ourselves - what we believe, what we doubt and what we fear. The same conspiracy around the coronavirus is no exception. Here is an overly complex global world that is difficult to understand, and new technologies that cause anxiety, and, perhaps, our most ancient fear - illness and death.

They say no less about ourselves - what we believe, what we doubt and what we fear. The same conspiracy around the coronavirus is no exception. Here is an overly complex global world that is difficult to understand, and new technologies that cause anxiety, and, perhaps, our most ancient fear - illness and death.

A recent study found that an individual's level of anxiety and stress is a good predictor of their belief in conspiracy theories. Anti-vaxxers, according to another study, worry more about the consequences of disasters and diseases and tend to exaggerate their magnitude. People in general tend to think that a big and high-profile event must have a big reason. Rob Brotherton called this cognitive distortion proportionality.

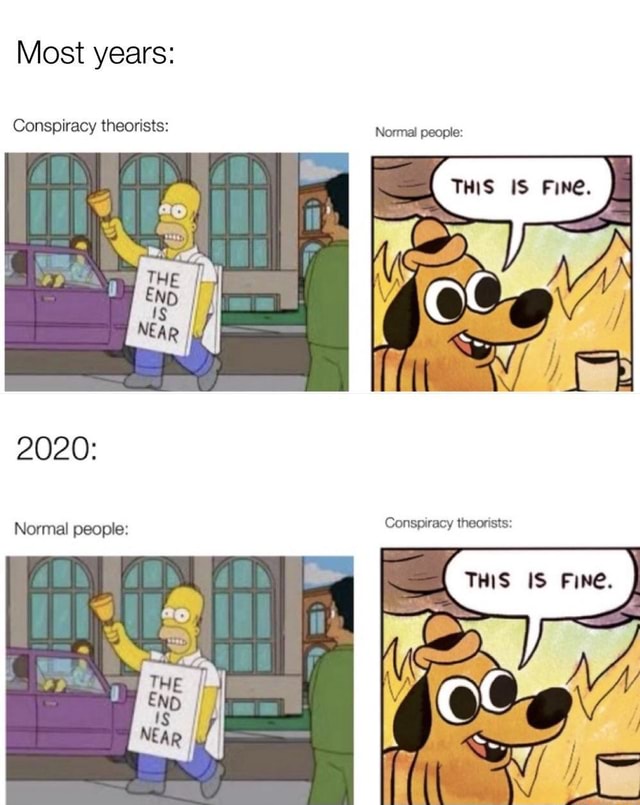

The pandemic has changed the way of life of a huge number of people: from household habits to financial stability, not to mention the risks of getting infected and dying. And not everyone is ready to come to terms with the fact that the reason is a bat from the Chinese market and a chain of random events. After all, this means that the world is too unpredictable.

After all, this means that the world is too unpredictable.

Conspiracy theories offer an alternative explanation. For example, such as Nikita Mikhalkov's: a pandemic is like a special operation by Bill Gates to chip the world's population. According to Ilya Yablokov, author of The Russian Culture of Conspiracy, conspiracy theories are “both implausible enough to explain the atypicality of what is happening, and consistent with the picture of the world of people who believe in them.”

Nikita Mikhalkov responds to critics

Conspiracy theories do not just correspond to a person's picture of the world. They are organic to how human thinking works.

A subject with specific intentions and plans - the organizer of the epidemic - is clearer to us than a series of unrelated events. It is desirable that the intentions be unkind - we evolutionarily recognize the threat much better. The subject himself must be "foreign", from another camp. The classic candidate is the elite. Strong "They" - power, corporations - against weak "us". Better even the world, overseas elite. Finally, the “enemy” must be known by sight, so a person is needed. Bill Gates is just such a candidate.

The classic candidate is the elite. Strong "They" - power, corporations - against weak "us". Better even the world, overseas elite. Finally, the “enemy” must be known by sight, so a person is needed. Bill Gates is just such a candidate.

The conspiracy narrative sets in motion the ancient mechanisms of the human psyche - to recognize intentions, avoid uncertainty, think in stories and be suspicious of outsiders.

The more vulnerable people are psychologically, socially and financially, the more attractive they will find conspiracy theory.

Conspiracy thinking is also associated with a feeling of helplessness. The team of scientists studied how people perceive optical illusions, superstitions, financial markets and conspiracy theories. The less control a person felt over circumstances, the more likely they were to see patterns where there were none.

Political scientist and author of Conspiracy Theories and the People Who Believe in Them Joseph Usinski put it this way: “Conspiracy theories are for losers. ”

”

Usinski calls losers people who:

-

unable to influence the circumstances of his life;

-

belong to a marginalized social group;

-

do not have powers and are excluded from the institutions of power.

Conspiracy theories provide a sense of security and control over an unstable and complex world.

Is it possible to convince a conspiracy theorist?

A person who has become an adherent of a conspiracy theory will defend it to the last. The stronger, the more it affects issues of politics and society (most conspiracy theories are just like that). The fact is that another psychological mechanism is turned on - the brain perceives a change in political beliefs as a threat.

Neuroscientists Jonas Kaplan, Sarah Gimbel and Sam Harris described how this happens in an article in Nature. They put 40 people of liberal convictions into the fMRI scanner and voiced theses that contradicted their views. With non-political statements - for example, that Einstein is not a great physicist, and sleep is not so important for rest - the subjects were willing to agree. Political topics—same-sex marriage, the death penalty, immigration, gun ownership, terrorism, abortion—aroused noticeably more resistance.

They put 40 people of liberal convictions into the fMRI scanner and voiced theses that contradicted their views. With non-political statements - for example, that Einstein is not a great physicist, and sleep is not so important for rest - the subjects were willing to agree. Political topics—same-sex marriage, the death penalty, immigration, gun ownership, terrorism, abortion—aroused noticeably more resistance.

The most interesting thing is that political topics activated completely different areas of the brain. In the most stubborn subjects, more ancient subcortical structures were active: the amygdala, which is responsible for fear reactions, and the insula, which is responsible for processing emotions. The default system of the brain was also active, a neural network that creates narratives about the world, about relationships with other people, and about ourselves.

All this is also relevant for conspiracy thinking, the whole essence of which is to help cope with the fear of uncertainty and the complexity of the world. Therefore, it is naive to think that a conspiracy theorist can be persuaded simply by laying out the arguments logically.

Therefore, it is naive to think that a conspiracy theorist can be persuaded simply by laying out the arguments logically.

Rachel Runels rightly points out that dissuading conspiracy theorists is more like a process of conversion. It is not so much the facts and explanations that are important here, but the inner, almost religious desire of the person himself to accept a different picture of the world.

Real conspiracies are exposed sooner or later. A conspiracy theory cannot be proven or disproven, it can only be believed. Any evidence can either be turned in your favor, or simply ignored.

Why are people attracted to conspiracy theories?

During the pandemic, many conspiracy theories have been linked to the name of Bill Gates. In the photo: a demonstration in Berlin. Copyright 2020 The Associated Press. All Rights Reserved According to a study by the University of Basel, approximately 30% of respondents in Germany and German-speaking Switzerland believe at least to some extent in one or another conspiracy theory related to the coronavirus pandemic. Why is it so, and even in our time of total availability of any information? We turned to a professor of social psychology for clarification.

Why is it so, and even in our time of total availability of any information? We turned to a professor of social psychology for clarification.

Igor Petrov prepared the original Russian version of the material.

Coronavirus was created in a laboratory by the world government in order to put everyone in the world under its control. No, you do not understand anything, the virus does not exist at all. The real motive behind the lockdown is to stop massive immigration from the global South to the global North and implement a mass human surveillance system along the way. Yes, it's all bullshit! It is clear that it was Bill Gates who created the virus in order to reduce the population of the planet in alliance with the reptilians who have long ruled over humanity.

Approximately 10% of respondents strongly believe in at least one of the conspiracy theories just listed. These are the results of the surveyExternal link , which was attended by approximately 1,600 people from Germany and German-speaking Switzerland. The survey was conducted by a team of experts from the University of Basel led by Sarah Kuhn and Thea Zander-Schellenberg. The survey also showed that another 20% of respondents support one of these theories at least "to some extent", 70% of respondents do not believe in any of these theories.

These are the results of the surveyExternal link , which was attended by approximately 1,600 people from Germany and German-speaking Switzerland. The survey was conducted by a team of experts from the University of Basel led by Sarah Kuhn and Thea Zander-Schellenberg. The survey also showed that another 20% of respondents support one of these theories at least "to some extent", 70% of respondents do not believe in any of these theories.

“Not surprising,” says Pascal Wagner-Egger ( Pascal Wagner-EggerExternal link ), a professor at the University of Fribourg (Switzerland) who studies conspiracy theories as a social psychology phenomenon. Similar polls conducted at the beginning of the pandemic in 2020 showed approximately the same percentages: 10% of respondents are convinced of the truth of at least one of the similar theories, and 20% believe in them "to some extent." Moreover, even before the start of the pandemic, all sociological studies of conspiracy theories showed approximately the same, if not higher, numbers.

Show more

Show more

“After a year of the pandemic, I'm even surprised that the percentage has not increased. Perhaps this is good news for us,” says Pascal Wagner-Egger, who nevertheless warns against overestimating this kind of data. No matter how interesting and tempting these figures are from a journalistic and political point of view, it would not be too responsible to simply extrapolate these proportions to the whole of society as a whole. Sociology as a science does not trust such surveys too much, because when someone answers “I believe”, you first need to understand what the respondent means.

How dangerous are conspiracy theories?

But even without scientific research, one only needs to look at social networks to understand how widespread this phenomenon is. When it comes to news related to the coronavirus, it's hard not to find at least one commentary based on at least one of these crazy theories. And it's not nearly as harmless as it might seem. “In the course of our research, we found that these kinds of beliefs often go hand in hand with generally anti-scientific attitudes towards reality, correlating, for example, with a negative attitude towards vaccination. During a pandemic, of course, this becomes a particular problem, because we all want to end the pandemic as soon as possible, and this can only be done with the help of vaccinations,” says P. Wagner-Egger.

And it's not nearly as harmless as it might seem. “In the course of our research, we found that these kinds of beliefs often go hand in hand with generally anti-scientific attitudes towards reality, correlating, for example, with a negative attitude towards vaccination. During a pandemic, of course, this becomes a particular problem, because we all want to end the pandemic as soon as possible, and this can only be done with the help of vaccinations,” says P. Wagner-Egger.

Show more

The sphere of politics and democracy in general also suffers. If you think that the majority of the media lie, and not only those media that I personally trust, if politicians are bought and experts are corrupt, then this is a sign of a systemic loss of trust in the institutions and structures of society, which is both a cause and a consequence of strengthening really extremist forces in society, both extreme right and extreme left, striving not just, say, to overcome the “climate crisis” or release the conditional “Assange”, but immediately “dismantle the system”, destroy democracy with its own, democracy, tools. The same thing happens with the so-called "coronaskeptics".

The same thing happens with the so-called "coronaskeptics".

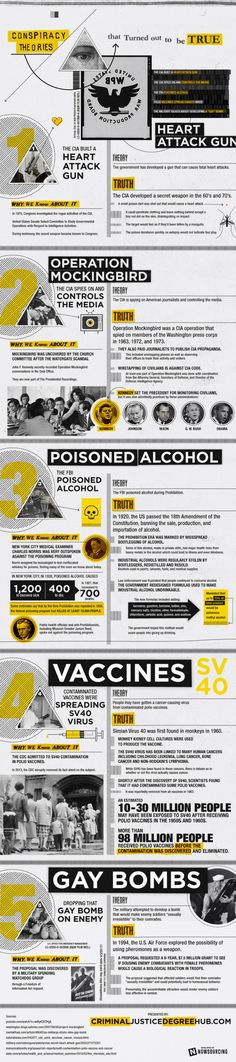

Net defamation and slander

At this point, it is important to be clear: we are talking about the dangers of believing in conspiracy theories, but both history and current events show that various kinds of conspiracies do exist in reality. A lot of things in society really "go wrong." Switzerland, for example, cannot finally establish a normal vaccination process. An ammunition depot blows up in the Czech Republic. But is it possible on this basis to conclude that any event is the result of a "conspiracy of the world government"? If you believe in "Occam's razor", then, probably, such conclusions should not be drawn.

Show more

Moreover, it is worth taking this or that theory and considering it more carefully, as it will most likely turn out that there are simply no rational proofs here. But on the other hand, such theories help, without particularly studying anything and without reading any texts “where there are a lot of letters”, not only quickly create a scientific picture of the world, but also try to earn political capital on this. “Such coronaskeptic beliefs lead nowhere and are counterproductive, even if you are truly sincerely opposed to the system. Why?

“Such coronaskeptic beliefs lead nowhere and are counterproductive, even if you are truly sincerely opposed to the system. Why?

“Because such beliefs are usually not based on any evidence, and therefore here, as nowhere else, the risk is that you will adhere to false positions and beliefs,” says P. Wagner-Egger. In other words, suspicions of a conspiracy may turn out to be true (even if most of these suspicions turn out to be, as a rule, false assumptions), but specific accusations of conspiracy without presenting specific evidence are already slander, that is, a crime.

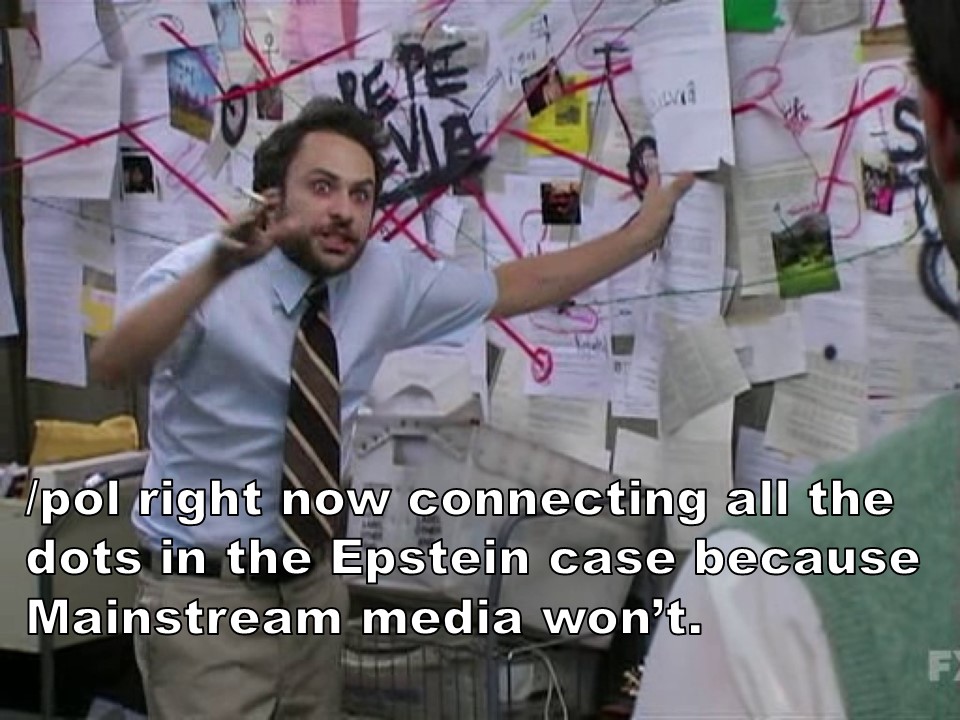

“If a real conspiracy is revealed somewhere, it almost always happens thanks to the work of law enforcement officers or investigative journalists, and certainly not thanks to people who sit in their “information bubbles” in networks and believe in all possible and conceivable conspiracies ”, says P. Wagner-Egger.

Wagner-Egger.

Where do conspiracy theories come from?

Despite the fact that the phenomenon of "conspiracy theory" today is at the very center of public attention, it is not something completely new. “Conspiracy theories began to appear immediately after human society moved to a settled life, and immediately after stable structures and institutions appeared in these societies and the struggle for power began,” explains P. Wagner-Egger.

In his opinion, there are three factors that explain the current success of all these unsubstantiated conspiracy theories. The first is the socio-political factor, already mentioned earlier. People who are hostile to public institutions and to the existing "system" tend to justify their actions with conspiracy theories.

Our manual: "How to talk to a conspiracy theorist"?

How should we deal with social media comments that spread conspiracy theories? Pascal Wagner-Egger regularly communicates with such "theorists" on social networks, and he admits that it is usually simply impossible to convince someone. “It's like arguing with a religious fanatic. If you tell him that dinosaur fossils exist in defiance of creationism, he will reply that the devil put them there to make us believe that everything in the Bible is a lie. The consciousness of a radical person cannot be changed,” he says.

“It's like arguing with a religious fanatic. If you tell him that dinosaur fossils exist in defiance of creationism, he will reply that the devil put them there to make us believe that everything in the Bible is a lie. The consciousness of a radical person cannot be changed,” he says.

Nevertheless, P. Wagner-Egger continues to engage in a dialogue with these people on the Internet, pointing out inconsistencies in their reasoning and warning them that serious allegations without evidence can become the subject of criminal proceedings. And even if the opinion of such an interlocutor is usually impossible to change, still P. Wagner-Egger does not consider the time spent talking with them lost. Why? For two reasons. Firstly, some “vague doubts” can be sown in the subconscious of conspiracy theorists with their arguments. Secondly, debates affect those who do not participate in them, but look at them from the side. Such people, as a rule, have not yet decided which camp to belong to and they are looking for the best arguments in favor of one side or another.

“People who tend to take a moderate position tend to react negatively to conspiracy theories,” says P. Wagner-Egger. The situation becomes noticeably more complicated if such a supporter of the "conspiracy theory" is someone close, for example, a family member or acquaintance. Sometimes the split line separates even spouses and parents with children on opposite sides of the barricades. In this case, you can use the technique of " epistemologicalExternal link interview", a kind of Socratic dialogue. The art here is to lead the discussion without expressing your own opinion.

“You do not state your own position, but you ask the interlocutor questions, forcing him to justify his position. Very often, these people themselves admit in the end that their beliefs have a rather fragile foundation. Epistemological interview is often used in humanistic psychology, it is a method that allows you to treat another person with respect, while creating a positive atmosphere, in contrast to social networks, where those who are only looking for something to “offend” dominate - summarizes P. Wagner-Egger.

Wagner-Egger.

End of insertion

Such beliefs are sometimes fueled by real social imbalances and real problems (the climate is indeed changing, and the problem of racism is real). It has already become a commonplace the thesis that the higher the degree of social inequality in society, the more prepared and fertilized the ground for the flourishing of the most incredible conspiracy theories, often combined with radical and extremist dreams of “revenge”, characteristic of the supposedly “infringed or "discriminated" social groups. “Although poverty in the world has been noticeably reduced, it still and by no means disappeared anywhere, and with the pandemic, its scale even began to grow again. In addition, the gap between the richest and the poorest is growing again. And this also feeds the so-called “conspiracy discourse,” says P. Wagner-Egger.

Show more

The second factor is of a psychological nature. Despite all the technological advancement, we humans as a species tend to have a naive, anti-scientific mindset, especially in fearful situations such as a terrorist threat or a pandemic. P. Wagner-Egger gives the example of a man walking alone through the forest at night: if he hears some kind of noise, then he is inclined to immediately think that it is a predator or someone who wants to harm him. Such thinking was "hardwired" into the matrix of human consciousness in the course of evolution. Our most paranoid ancestors survived precisely because they preferred to react in case of a possible danger and not rely on chance! We inherited this character trait as a genetic gift, for which we should actually be thankful.

Despite all the technological advancement, we humans as a species tend to have a naive, anti-scientific mindset, especially in fearful situations such as a terrorist threat or a pandemic. P. Wagner-Egger gives the example of a man walking alone through the forest at night: if he hears some kind of noise, then he is inclined to immediately think that it is a predator or someone who wants to harm him. Such thinking was "hardwired" into the matrix of human consciousness in the course of evolution. Our most paranoid ancestors survived precisely because they preferred to react in case of a possible danger and not rely on chance! We inherited this character trait as a genetic gift, for which we should actually be thankful.

“Cognitive distortions due to evolution fuel the belief not only in conspiracies, but also in the paranormal. Seeing ghosts or seeing some hidden motives in people's actions - all this was relevant a hundred and two hundred years ago, ”explains P. Wagner-Egger. The third factor is the Internet, in which conspiracy theories can not only spread with great speed, but also remain forever in the "global cache", so to speak. Does the Internet forget anything? Sometimes this property is very useful, and sometimes not. As soon as you start searching for information about a particular conspiracy theory, you can very easily and quickly stumble upon materials that seem to have already been deleted from everywhere. But they still remain, whereas without the Internet they would be firmly forgotten.

The third factor is the Internet, in which conspiracy theories can not only spread with great speed, but also remain forever in the "global cache", so to speak. Does the Internet forget anything? Sometimes this property is very useful, and sometimes not. As soon as you start searching for information about a particular conspiracy theory, you can very easily and quickly stumble upon materials that seem to have already been deleted from everywhere. But they still remain, whereas without the Internet they would be firmly forgotten.

Return to normal life?

How to deal with conspiracy theories? P. Wagner-Egger advises, in a Marxist way, “to start from the root causes and try to reduce the degree of social inequality, strengthen the fight against corruption, ensure the availability of impartial, competent and enlightened professional journalism, achieve a real implementation of the principle of separation of powers, when each of the branches of power (legislative, executive and judicial) is independent and independent in the exercise of its powers”. It is also desirable to have feedback between society and the authorities in the form of elections, the change of power, and even, as in Switzerland, in the format of direct democracy.

It is also desirable to have feedback between society and the authorities in the form of elections, the change of power, and even, as in Switzerland, in the format of direct democracy.

Show more

These are all important things in themselves, but they are also very useful and effective methods of dealing with such a phenomenon as conspiracy theory. From the point of view of mentality, according to P. Wagner-Egger, the most effective way to develop immunity to conspiracy theories is modern education and educational activities: this is the only way to teach young people, and not only people, to think critically, not to believe everything at once and check the information . Terribly interesting is everything that is unknown, who would argue! But without concrete evidence, trusting incomprehensible "British scientists", we run the risk of falling into an endless dead end of obscurantism and lies.

The end of the pandemic will of course lead to fewer conspiracy theories on social media, but "fake news" and government propaganda, including foreign propaganda, will remain a problem for a very long time, if not forever.