Who said insanity is doing the same thing

Einstein's Parable of Quantum Insanity

Share on Facebook

Share on Twitter

Share on Reddit

Share on LinkedIn

Share via Email

Print

From Quanta Magazine (find original story here).

“Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results.”

That witticism—I’ll call it “Einstein Insanity”—is usually attributed to Albert Einstein. Though the Matthew effect may be operating here, it is undeniably the sort of clever, memorable one-liner that Einstein often tossed off. And I’m happy to give him the credit, because doing so takes us in interesting directions.

First of all, note that what Einstein describes as insanity is, according to quantum theory, the way the world actually works. In quantum mechanics you can do the same thing many times and get different results. Indeed, that is the premise underlying great high-energy particle colliders. In those colliders, physicists bash together the same particles in precisely the same way, trillions upon trillions of times. Are they all insane to do so? It would seem they are not, since they have garnered a stupendous variety of results.

Of course Einstein, famously, did not believe in the inherent unpredictability of the world, saying “God does not play dice.” Yet in playing dice, we act out Einstein Insanity: We do the same thing over and over—namely, roll the dice—and we correctly anticipate different results. Is it really insane to play dice? If so, it’s a very common form of madness!

We can evade the diagnosis by arguing that in practice one never throws the dice in precisely the same way. Very small changes in the initial conditions can alter the results. The underlying idea here is that in situations where we can’t predict precisely what’s going to happen next, it’s because there are aspects of the current situation that we haven’t taken into account. Similar pleas of ignorance can defend many other applications of probability from the accusation of Einstein Insanity to which they are all exposed. If we did have full access to reality, according to this argument, the results of our actions would never be in doubt.

Similar pleas of ignorance can defend many other applications of probability from the accusation of Einstein Insanity to which they are all exposed. If we did have full access to reality, according to this argument, the results of our actions would never be in doubt.

This doctrine, known as determinism, was advocated passionately by the philosopher Baruch Spinoza, whom Einstein considered a great hero. But for a better perspective, we need to venture even further back in history.

Parmenides was an influential ancient Greek philosopher, admired by Plato (who refers to “father Parmenides” in his dialogue the Sophist). Parmenides advocated the puzzling view that reality is unchanging and indivisible and that all movement is an illusion. Zeno, a student of Parmenides, devised four famous paradoxes to illustrate the logical difficulties in the very concept of motion. Translated into modern terms, Zeno’s arrow paradox runs as follows:

- If you know where an arrow is, you know everything about its physical state.

- Therefore a (hypothetically) moving arrow has the same physical state as a stationary arrow in the same position.

- The current physical state of an arrow determines its future physical state. This is Einstein Sanity—the denial of Einstein Insanity.

- Therefore a (hypothetically) moving arrow and a stationary arrow have the same future physical state.

- The arrow does not move.

Followers of Parmenides worked themselves into logical knots and mystic raptures over the rather blatant contradiction between point five and everyday experience.

The foundational achievement of classical mechanics is to establish that the first point is faulty. It is fruitful, in that framework, to allow a broader concept of the character of physical reality. To know the state of a system of particles, one must know not only their positions, but also their velocities and their masses. Armed with that information, classical mechanics predicts the system’s future evolution completely. Classical mechanics, given its broader concept of physical reality, is the very model of Einstein Sanity.

Classical mechanics, given its broader concept of physical reality, is the very model of Einstein Sanity.

With that triumph in mind, let us return to the apparent Einstein Insanity of quantum physics. Might that difficulty likewise hint at an inadequate concept of the state of the world?

Einstein himself thought so. He believed that there must exist hidden aspects of reality, not yet recognized within the conventional formulation of quantum theory, which would restore Einstein Sanity. In this view it is not so much that God does not play dice, but that the game he’s playing does not differ fundamentally from classical dice. It appears random, but that’s only because of our ignorance of certain “hidden variables.” Roughly: “God plays dice, but he’s rigged the game.”

But as the predictions of conventional quantum theory, free of hidden variables, have gone from triumph to triumph, the wiggle room where one might accommodate such variables has become small and uncomfortable. In 1964, the physicist John Bell identified certain constraints that must apply to any physical theory that is both local—meaning that physical influences don’t travel faster than light—and realistic, meaning that the physical properties of a system exist prior to measurement. But decades of experimental tests, including a “loophole-free” test published on the scientific preprint site arxiv.org last month, show that the world we live in evades those constraints.

In 1964, the physicist John Bell identified certain constraints that must apply to any physical theory that is both local—meaning that physical influences don’t travel faster than light—and realistic, meaning that the physical properties of a system exist prior to measurement. But decades of experimental tests, including a “loophole-free” test published on the scientific preprint site arxiv.org last month, show that the world we live in evades those constraints.

Ironically, conventional quantum mechanics itself involves a vast expansion of physical reality, which may be enough to avoid Einstein Insanity. The equations of quantum dynamics allow physicists to predict the future values of the wave function, given its present value. According to the Schrödinger equation, the wave function evolves in a completely predictable way. But in practice we never have access to the full wave function, either at present or in the future, so this “predictability” is unattainable. If the wave function provides the ultimate description of reality—a controversial issue!—we must conclude that “God plays a deep yet strictly rule-based game, which looks like dice to us. ”

”

Einstein’s great friend and intellectual sparring partner Niels Bohr had a nuanced view of truth. Whereas according to Bohr, the opposite of a simple truth is a falsehood, the opposite of a deep truth is another deep truth. In that spirit, let us introduce the concept of a deep falsehood, whose opposite is likewise a deep falsehood. It seems fitting to conclude this essay with an epigram that, paired with the one we started with, gives a nice example:

“Naïveté is doing the same thing over and over, and always expecting the same result.”

Frank Wilczek was awarded the 2004 Nobel Prize in physics for his work on the theory of the strong force. His most recent book is A Beautiful Question: Finding Nature’s Deep Design. Wilczek is the Herman Feshbach Professor of Physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Reprinted with permission from Quanta Magazine, an editorially independent publication of the Simons Foundation whose mission is to enhance public understanding of science by covering research developments and trends in mathematics and the physical and life sciences.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR(S)

Frank Wilczek is the Herman Feshbach Professor of Physics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He won the Nobel Prize in Physics in 2004 for his work on the theory of the strong force. Credit: Nick Higgins

Insanity Is Doing the Same Thing Over and Over Again and Expecting Different Results – Quote Investigator

Albert Einstein? Al-Anon? Narcotics Anonymous? Max Nordau? George Bernard Shaw? Samuel Beckett? George A. Kelly? Rita Mae Brown? John Larroquette? Jessie Potter? Werner Erhard?

Dear Quote Investigator: It’s foolish to repeat ineffective actions. One popular formulation presents this point harshly:

The definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting a different result.

These words are usually credited to the acclaimed genius Albert Einstein. What do you think?

Quote Investigator: There is no substantive evidence that Einstein wrote or spoke the statement above. It is listed within a section called “Misattributed to Einstein” in the comprehensive reference “The Ultimate Quotable Einstein” from Princeton University Press.[1] 2010, The Ultimate Quotable Einstein, Edited by Alice Calaprice, Section: Misattributed to Einstein, Quote Page 474, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey. (Verified on paper)

It is listed within a section called “Misattributed to Einstein” in the comprehensive reference “The Ultimate Quotable Einstein” from Princeton University Press.[1] 2010, The Ultimate Quotable Einstein, Edited by Alice Calaprice, Section: Misattributed to Einstein, Quote Page 474, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey. (Verified on paper)

The earliest strong match known to QI appeared in October 1981 within a Knoxville, Tennessee newspaper article describing a meeting of Al-Anon, an organization designed to help the families of alcoholics. The journalist described the “Twelve Steps” of Al-Anon which are based on similar steps employed in Alcoholics Anonymous. The newspaper began with these two steps:[2] 1981 October 11, The Knoxville News-Sentinel Al-Anon Helps Family, Friends to Orderly Lives by Betsy Pickle (Living Today Staff Writer), Quote Page F17, Column 2, Knoxville, Tennessee. (GenealogyBank)

Step 1: We admitted we were powerless over alcohol – that our lives had become unmanageable.

Step 2: Came to believe that a Power greater than ourselves could restore us to sanity

One of the attendees at the meeting hesitated to accept the accuracy of second step. Emphasis added to excerpts by QI:

Not all the women are willing to admit they needed to be “restored to sanity.” In fact, one of them adamantly maintains that she had never reached a point of insanity. But another remarks, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.”

The second earliest strong match known to QI appeared in a pamphlet printed by the Narcotics Anonymous organization in November 1981:[3]1981, Narcotics Anonymous Pamphlet, (Basic Text Approval Form, Unpublished Literary Work), Chapter Four: How It Works, Step Two, Page 11, Printed November 1981, Copyright 1981, W.S.C.-Literature … Continue reading

The price may seem higher for the addict who prostitutes for a fix than it is for the addict who merely lies to a doctor, but ultimately both pay with their lives.

Insanity is repeating the same mistakes and expecting different results.

QI acquired a PDF of the document with the quotation above on the website amonymifoundation.org back in February 2011. The document stated that is was printed in November 1981, and it had a 1981 copyright notice. The website was subsequently reorganized, but the document remains available via the Internet Archive Wayback Machine database.

Below are additional selected citations in chronological order.

The linkage between insanity and repetition has a long history. The controversial book “Degeneration” by Max Nordau was published in German in 1892 and translated into English by 1895. Nordau examined the works of a variety of artists and savagely attacked those that contained repetition which he believed evinced a mental defect in the creator. For example, he criticized Maurice Maeterlinck’s “La Princesse Maleine”:[4] 1895 Copyright, Degeneration by Max Nordau (Max Simon Nordau) (Translated from the Second Edition of the German Work), Quote Page 238, D. Appleton and Company. (Google Books Full View) link

Appleton and Company. (Google Books Full View) link

Has anyone anywhere in the poetry of the two worlds ever seen such complete idiocy? These ‘Ahs’ and ‘Ohs,’ this want of comprehension of the simplest remarks, this repetition four or five times of the same imbecile expressions, gives the truest conceivable clinical picture of incurable cretinism. These parts are precisely those most extolled by Maeterlinck’s admirers.

When George Bernard Shaw reviewed Nordau’s opus he turned the criticism of repetition back upon the author and suggested that Nordau might diagnose himself as mentally unsound:[5]1895 July 27, Liberty, Volume 11, Number 6, A Degenerate’s View of Nordau by Bernard Shaw, Quote Page 2, Column 1, Published by Benj. R Tucker, New York. (Reprint in 1970 by Greenwood Reprint … Continue reading

I have read Max Nordau’s “Degeneration” at your request,—two hundred and sixty thousand mortal words, saying the same thing over and over again.

That, as you know, is the way to drive a thing into the mind of the world, though Nordau considers it a symptom of insane “obsession” on the part of writers who do not share his own opinions. His message to the world is that all our characteristically modern works of art are symptoms of disease in the artists, and that these diseased artists are themselves symptoms of the nervous exhaustion of the race by overwork.

The 1955 book “The Psychology of Personal Constructs” by George A. Kelly included a definition that corresponded to the saying under investigation although it employed a different vocabulary:[6] 1955, The Psychology of Personal Constructs by George A. Kelly, Volume 2: Clinical Diagnosis and Psychotherapy, Quote Page 831, Published by W. W. Norton & Company, New York. (Verified on paper)

From the standpoint of the psychology of personal constructs we may define a disorder as any personal construction which is used repeatedly in spite of consistent invalidation.

This is an unusual definition, as psychological thinking ordinarily goes.

In October 1981 an educator and counselor on family relationships delivered a speech containing a thematically related adage:[7] 1981 October 24, The Milwaukee Sentinel, Search For Quality Called Key To Life by Tom Ahern, Quote Page 5, Column 5, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. (Google News Archive)

“If you always do what you’ve always done, you always get what you’ve always gotten.” That was the advice of Jessie Potter, the featured speaker at Friday’s opening of the seventh annual Woman to Woman conference.

More information about the quotation above is available here.

In October 1981 the saying was spoken by an attendee of an Al-Anon meeting as noted previously:

Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again and expecting different results.

In November 1981 a pamphlet from Narcotics Anonymous contained a close match as noted previously:

Insanity is repeating the same mistakes and expecting different results.

The 1983 novel “Sudden Death” by Rita Mae Brown included an instance credited to Jane Fulton who was a character within the book:[8] 1983, Sudden Death by Rita Mae Brown, Chapter 4, Quote Page 68, Published by Bantam Books, New York. (Verified with scans)

The trouble with Susan was that she made the same mistakes repeatedly. She’d fall in love with a woman and consume her. Susan thought that her mere presence was enough. What more was there to give? When she tired, usually after a year or so, she’d find another woman.

Unfortunately, Susan didn’t remember what Jane Fulton once said. “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting different results.”

A June 1983 book review of “Sudden Death” in “The Clarion-Ledger” of Jackson, Mississippi reprinted the saying:[9]1983 June 19, The Clarion-Ledger, “Sudden Death” a complex metaphor by Stephen L. Silberman, (Book review of “Sudden Death” by Rita Mae Brown), Quote Page 7H, Column 2, … Continue reading

Women’s tennis gets a thorough dissecting in this story.

Jane Fulton is the critical sports writer who contends “Modern professional sports rewards players for function instead of character. Responsibility is normally defined as doing a job better than anyone else.” She looks askance at professional tennis and says “Win and become a god. Lose and be forgotten.” Finally after following the lives and careers of the players, and the game itself, she concludes, “Insanity is doing the same thing over and over and over again, but expecting different results.”

Also in 1983 Samuel Beckett, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, offered a counterpoint perspective in his work “Worstward Ho”:[10] 1983, Worstward Ho by Samuel Beckett, Quote Page 7, Grove Press Inc., New York. (Verified with scans)

All of old. Nothing else ever. Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.

In January 1986 the Emmy-winning actor John Larroquette who was a star in the television comedy series “Night Court” shared the definition during a newspaper interview:[11]1986 January 5, The Sydney Morning Herald, Television with Jacqueline Lee Lewes: From drugs, drink to… Night Court: ‘Confessions of an Emmy Star, Quote Page 31, Column 3, Sydney, New … Continue reading

He pops in a definition of insanity – “It’s the repetition of the same action expecting different results.

Like jumping out of a 40-storey building, breaking every bone, spending six months in hospital, going back to the same building, up to the 39th floor, jumping and expecting it to be different. It is NEVER different.”

In April 1986 an opinion piece by Baltazar A. Acevedo Jr in “The Dallas Morning News” of Texas included the saying:[12] 1986 April 25, The Dallas Morning News, Leadership Beyond Ethnicity Should Be Goal of Dallasites by Baltazar A. Acevedo Jr., Dallas, Texas. (NewsBank Access World News)

I once heard insanity defined as a process by which an individual or a system does something over and over again in the same way while yet expecting different results. To continue to evaluate and address issues in our community strictly along ethnic, instead of human, considerations is insane if only for one reason: It will lead to the polarization that is the standard of paranoid societies.

The 1988 book “Raising Self-Reliant Children in a Self-Indulgent World” included an instance:[13]1988 Copyright, Raising Self-Reliant Children in a Self-Indulgent World: Seven Building Blocks for Developing Capable Young People by H. Stephen Glenn and Jane Nelsen, Quote Page 174, Published by … Continue reading

Stephen Glenn and Jane Nelsen, Quote Page 174, Published by … Continue reading

Flexibility is the ability to bend when we find ourselves in unworkable positions. A universal characteristic of insanity is inflexibly doing the same thing over and over while hoping for different results. Flexibility in the face of changing circumstances, by contrast, is a hallmark of mental health.

By 1990 the saying was being attributed to Einstein. For example, the “Austin American-Statesman” of Austin, Texas published the following remark made by Travis County District Attorney Ronnie Earle:[14]1990 November 19, Austin American-Statesman, Section: News, Prison Puzzle – Threat of cost explosion poses difficult choices by Mike Ward, Quote Page A1, Austin, Texas. (NewsBank Access World … Continue reading

Einstein once said that insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different result.

In 1991 “The Seattle Times” printed the thoughts of an Indiana judge who ascribed another version of the saying to Einstein:[15] 1991 July 4, The Seattle Times, Section: Editorial, Getting Out of the Freedom Business by Don Williamson, Quote Page A8, Seattle, Washington. (NewsBank Access World News)

The jurist from the Hoosier State subscribes to Albert Einstein’s definition of insanity: “doing the same thing over and over and expecting a different outcome.”

In 2000 a columnist working for the Knight Ridder News Service ascribed a version of the saying to the influential lecturer and trainer Werner Erhard although the name was misspelled as “Erhart”:[16] 2000 July 30, The Indianapolis Star, Get a plan to overcome trouble spots by Tim O’Brien (Knight Ridder News Service), Quote Page J3, Column 1, Indianapolis, Indiana. (Newspapers_com)

Werner Erhart described insanity as ‘repeating identical behavior and expecting a different result.

’ If we repeatedly have difficulties in an area of life, doesn’t it make sense that our behaviors cause the problems?

In 2016 the webcomic “xkcd” depicted two characters conversing; the first mentioned the now well-known definition of insanity, and the second replied with a remark that implicitly and cleverly applied the logic of the definition to his companion:[17]Website: xkcd Comic, Comic title: Insanity, Comic author: Randall Munroe, Date on website: March 18, 2016, Website description: A webcomic of romance, sarcasm, math, and language. (Accessed xkcd.com … Continue reading

You’ve been quoting that cliché for years. Has it convinced anyone to change their mind yet?

In conclusion, based on current evidence the saying originated in one of the twelve-step communities. Anonymity is greatly valued in these communities, and no specific author has been identified by the many researchers who have explored the provenance of this adage. The linkage to Albert Einstein occurred many years after his death and is unsupported.

The linkage to Albert Einstein occurred many years after his death and is unsupported.

Image Notes: Two arrows pointing at one another from OpenClipart-Vectors at Pixabay. Portrait of Albert Einstein circa 1921 by Ferdinand Schmutzer accessed via Wikimedia Commons. Images have been retouched, cropped and resized.

(Great thanks to MJ Redman, Kevin Ashton, Melinda Denson, Linda Sternhill Davis, The Muser, Mededitor, Santanu Vasant, Simon Lancaster, Michael Cochran, David Meadows, J Carson, Guilherme Simões, Ed Darrell, Lee Winkelman, and Fabius Maximus (Ed.) whose inquiries led QI to formulate this question and perform this exploration. Special thanks to the volunteer researchers Quora and Wikiquote who mentioned the Narcotics Anonymous citation. Also, thanks to the valuable research conducted by Barry Popik, Ben Zimmer, and Daniel Gackle. Many thanks to Bill Mullins who located the important October 11, 1981 citation.)

Update History: On July 31, 2019 the October 11, 1981 citation was added to the article.

References

| ↑1 | 2010, The Ultimate Quotable Einstein, Edited by Alice Calaprice, Section: Misattributed to Einstein, Quote Page 474, Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey. (Verified on paper) |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | 1981 October 11, The Knoxville News-Sentinel Al-Anon Helps Family, Friends to Orderly Lives by Betsy Pickle (Living Today Staff Writer), Quote Page F17, Column 2, Knoxville, Tennessee. (GenealogyBank) |

| ↑3 | 1981, Narcotics Anonymous Pamphlet, (Basic Text Approval Form, Unpublished Literary Work), Chapter Four: How It Works, Step Two, Page 11, Printed November 1981, Copyright 1981, W.S.C.-Literature Sub-Committee of Narcotics Anonymous], World Service Conference of Narcotics Anonymous. (Accessed at amonymifoundation.org on October 3, 2011; website has been restructured; text is available via Internet Archive Wayback Machine Snapshot January 1, 2013 link PDF of pamphlet link |

| ↑4 | 1895 Copyright, Degeneration by Max Nordau (Max Simon Nordau) (Translated from the Second Edition of the German Work), Quote Page 238, D. Appleton and Company. (Google Books Full View) link Appleton and Company. (Google Books Full View) link |

| ↑5 | 1895 July 27, Liberty, Volume 11, Number 6, A Degenerate’s View of Nordau by Bernard Shaw, Quote Page 2, Column 1, Published by Benj. R Tucker, New York. (Reprint in 1970 by Greenwood Reprint Corporation, Westport, Connecticut)(HathiTrust Full View) link |

| ↑6 | 1955, The Psychology of Personal Constructs by George A. Kelly, Volume 2: Clinical Diagnosis and Psychotherapy, Quote Page 831, Published by W. W. Norton & Company, New York. (Verified on paper) |

| ↑7 | 1981 October 24, The Milwaukee Sentinel, Search For Quality Called Key To Life by Tom Ahern, Quote Page 5, Column 5, Milwaukee, Wisconsin. (Google News Archive) |

| ↑8 | 1983, Sudden Death by Rita Mae Brown, Chapter 4, Quote Page 68, Published by Bantam Books, New York. (Verified with scans) |

| ↑9 | 1983 June 19, The Clarion-Ledger, “Sudden Death” a complex metaphor by Stephen L. Silberman, (Book review of “Sudden Death” by Rita Mae Brown), Quote Page 7H, Column 2, Jackson, Mississippi. (Newspapers_com) Silberman, (Book review of “Sudden Death” by Rita Mae Brown), Quote Page 7H, Column 2, Jackson, Mississippi. (Newspapers_com) |

| ↑10 | 1983, Worstward Ho by Samuel Beckett, Quote Page 7, Grove Press Inc., New York. (Verified with scans) |

| ↑11 | 1986 January 5, The Sydney Morning Herald, Television with Jacqueline Lee Lewes: From drugs, drink to… Night Court: ‘Confessions of an Emmy Star, Quote Page 31, Column 3, Sydney, New South Wales, Australia. (Newspapers_com) |

| ↑12 | 1986 April 25, The Dallas Morning News, Leadership Beyond Ethnicity Should Be Goal of Dallasites by Baltazar A. Acevedo Jr., Dallas, Texas. (NewsBank Access World News) |

| ↑13 | 1988 Copyright, Raising Self-Reliant Children in a Self-Indulgent World: Seven Building Blocks for Developing Capable Young People by H. Stephen Glenn and Jane Nelsen, Quote Page 174, Published by Prima Publishing & Communications, Rocklin, California. (Verified on paper) (Verified on paper) |

| ↑14 | 1990 November 19, Austin American-Statesman, Section: News, Prison Puzzle – Threat of cost explosion poses difficult choices by Mike Ward, Quote Page A1, Austin, Texas. (NewsBank Access World News) |

| ↑15 | 1991 July 4, The Seattle Times, Section: Editorial, Getting Out of the Freedom Business by Don Williamson, Quote Page A8, Seattle, Washington. (NewsBank Access World News) |

| ↑16 | 2000 July 30, The Indianapolis Star, Get a plan to overcome trouble spots by Tim O’Brien (Knight Ridder News Service), Quote Page J3, Column 1, Indianapolis, Indiana. (Newspapers_com) |

| ↑17 | Website: xkcd Comic, Comic title: Insanity, Comic author: Randall Munroe, Date on website: March 18, 2016, Website description: A webcomic of romance, sarcasm, math, and language. (Accessed xkcd.com on March 23, 2017) link |

I didn't say that: 5 fake quotes attributed to famous people - www.

ellegirl.ru

ellegirl.ru Trending

How often do we believe the authorship of quotes written on the Internet. Often such words this person did not even think to say. Find out what is true and what is fiction.

“Insanity is the exact repetition of the same action. Time after time, in the hope of change. This is madness”

Attributed to: Albert Einstein

Actually: This quote, taken as if from the lips of a maniac from a thriller, was attributed to Benjamin Franklin, Mark Twain and Albert Einstein. Most often on the Internet, a quote is signed with the name of the latter.

But initially the phrase was never associated with the mentally ill. The first version of it was written in a book by Narcotics Anonymous and was intended to help people in rehab: "Insanity is repeating the same mistakes over and over expecting different results." That's a turn, isn't it?

- Photo

- Giphy.com

to be attributed: Sherlock Holmes, Hero Arthur Conan-Dula

In fact: The most famous phrase, with which the image is blessed Sherlock Holmes, was never pronounced sleuth in the books. The quote was first used in P. G. Wodehouse's novel Psmith the Journalist and was not associated with the detective. The hero used it in an ironic context, grinning at someone else's narrow-mindedness.

The phrase was first used in cinema in 1929, in the British film adaptation of The Return of Sherlock Holmes.

- photo

- Giphy.com

“Decent women rarely make history”

who is attributed: Marilyn Monroe

In fact: How often did you meet this quote in publics, which is attributed to the public legendary actress? So, the words belong to a completely different person. In 1976, historian and professor Laurel Thatcher Ulrich published an essay in a scientific journal - from there the quote floated "to the people" and into popular culture.

In 1976, historian and professor Laurel Thatcher Ulrich published an essay in a scientific journal - from there the quote floated "to the people" and into popular culture.

- Photo

- Giphy.com

to be attributed: Joseph Stalin

In fact: The phrase is actually taken from the play by 1942 “Front” “Front” of the playwright of Alexander Korneychychik . The writer, in turn, simply translated a phrase spoken in the 19th century by French commissioner Joseph Le Bon in response to a request for pardon for an aristocrat. Allegedly, this man was smart, strong and could be useful to the republic - but, as you know, there are many such people in the world.

- Photo

- giphy.com

“If I fall asleep and wake up in a hundred years and they ask me what is happening in Russia now, I will answer without hesitation: they drink and steal”

Attributed to : Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin

Actually: Words are often given as an epigraph in articles or in VKontakte statuses, but the Russian writer himself did not write or say anything of the kind.

In the collection of short stories The Blue Book, Mikhail Zoshchenko attributes very similar words to the authorship of another Russian writer, Nikolai Karamzin. Originally the phrase sounded differently:

“If one were to answer the question: what is being done in Russia, one would have to say: ‘they steal’.”

- Photos

- giphy.

com

com

Angelina Privalova

Tags

- quotes

Richard Shane. Nietzsche: The Will to Madness

Preface

(N. Speranskaya)

The question of Nietzsche's madness is one of the key to understanding the Dionysian spirit of his philosophy. Since 1889Nietzsche signs his letters with the names of the Crucified and Dionysus (then this image merges together, giving rise to Dionysus the Crucified) and announces that God has returned to earth. This gives his acquaintances a good reason to suspect insanity. But was it really so? If we discard all the restless and, I must say, obvious remarks of those who visited him in the Binswanger psychiatric hospital, is it possible to consider the situation in a different way? Moreover, Köselitz twice pointed out Nietzsche's clear thinking, which would hardly coexist with the complete disintegration of the personality seen by the emotional Overbain. It is high time to cite excerpts from two letters of Köselitz: "How clearly Nietzsche thinks follows from the fact that he demonstrated to Dr. Langben a mathematically provable thesis about the endless repetition of all stages of the development of the universe and, in general, discussed all his problems with him in an absolutely conscious way" and, finally, more important words: "I I saw Nietzsche in such states when it seemed to me with eerie distinctness that he was feigning madness. What, in fact, inspired such horror in the townsfolk, if not Nietzsche's buffoonery? Have all its addressees forgotten that Nietzsche hid behind masks throughout his life?

It is high time to cite excerpts from two letters of Köselitz: "How clearly Nietzsche thinks follows from the fact that he demonstrated to Dr. Langben a mathematically provable thesis about the endless repetition of all stages of the development of the universe and, in general, discussed all his problems with him in an absolutely conscious way" and, finally, more important words: "I I saw Nietzsche in such states when it seemed to me with eerie distinctness that he was feigning madness. What, in fact, inspired such horror in the townsfolk, if not Nietzsche's buffoonery? Have all its addressees forgotten that Nietzsche hid behind masks throughout his life?

The man who confessed to being Buddha and Dionysus, Alexander and Caesar, Lord Bacon and Voltaire, the man who sings and laughs aloud—has he not comprehended the coniunctio oppositorum, has he not become a living proof of the principle "All in All" ”, has he not ascended to that stage, whence there is no longer any difference between Dionysus and the Crucified? Doesn't Nietzsche reveal the riddle in the words: "Sometimes madness itself is a mask behind which hides fatal and too certain knowledge"? Friedrich Jünger believed that Nietzschean madness was connected with the forces of Dionysian catharsis.

Socrates, in the Phaedrus dialogue, distinguishes four types of divine fury (madness), anticipating this classification with the remark: “the greatest blessings for us arise from fury, it is true, when it [fury] is given to us as a gift from God”:

— Prophetic fury , whose patron is Apollo,

- Ritual and, I would even say, mystical frenzy, under the auspices of Dionysus,

- Creative frenzy coming from the Muses,

- Love fury bestowed by Eros and Aphrodite.

Let us dwell mainly on the second, Dionysian form of madness , and note that it must be considered from two positions: either as a GIFT of the god Dionysus, or as his CURSE and punishment. Based on this difference, Vyach. Ivanov came to the concept of "right madness" and "left madness". Let us turn to the well-known legend about the leader of the Thessalian armies, Eurypyle, as presented by Ivanov:

“There is an ancient myth. When the Hellenic heroes were dividing the spoils and captivity of Troy, the dark lot was cast by Euripilus, the leader of the Thessalian armies. Ardent Cassandra threw at the feet of the victors, from the threshold of the flaming royal treasuries, the glorious, from ancient times closed concealment, the work of Hephaestus. Zeus himself gave it to the once old Dardanus, the builder of Troy, as a gift - a pledge of divine patronymic. By the providence of a secret god, the decrepit shrine came to the Thessalian with a vengeance. In vain do the comrades-leaders persuade Eurypylus to beware of the machinations of the furious prophetess: it is better to throw him his gift to the bottom of the Scamander. But Eurypylus burns to taste the mysterious lot, carries away the ark - and, turning it around, sees in the glow of the fire - not a bearded husband in a coffin, crowned with spreading branches, - a wooden, fig tree idol of King Dionysus in an ancient cancer. As soon as the hero looked at the image of the god, his mind became confused.

Ardent Cassandra threw at the feet of the victors, from the threshold of the flaming royal treasuries, the glorious, from ancient times closed concealment, the work of Hephaestus. Zeus himself gave it to the once old Dardanus, the builder of Troy, as a gift - a pledge of divine patronymic. By the providence of a secret god, the decrepit shrine came to the Thessalian with a vengeance. In vain do the comrades-leaders persuade Eurypylus to beware of the machinations of the furious prophetess: it is better to throw him his gift to the bottom of the Scamander. But Eurypylus burns to taste the mysterious lot, carries away the ark - and, turning it around, sees in the glow of the fire - not a bearded husband in a coffin, crowned with spreading branches, - a wooden, fig tree idol of King Dionysus in an ancient cancer. As soon as the hero looked at the image of the god, his mind became confused.

Ivanov saw in this legend a mythical representation of the fate of Friedrich Nietzsche. We may ask ourselves: wasn't it the same image that Gerard Labruni, better known as Gerard de Nerval, saw and, unable to endure a fierce battle with the sacred, fixed his vertical with a rope and a lamppost? Doesn't Vrubel's demonic insight give us the right to guess that he saw the image of the god Dionysus? And how not to ask how Hölderlin's search for the Dionysian secret of Hellas ended, at the end of the path he revealed the dark Scardanelli to the world?

We may ask ourselves: wasn't it the same image that Gerard Labruni, better known as Gerard de Nerval, saw and, unable to endure a fierce battle with the sacred, fixed his vertical with a rope and a lamppost? Doesn't Vrubel's demonic insight give us the right to guess that he saw the image of the god Dionysus? And how not to ask how Hölderlin's search for the Dionysian secret of Hellas ended, at the end of the path he revealed the dark Scardanelli to the world?

The madness of poets, the madness of artists, the madness of musicians "burning to taste the mysterious lot" bears the fiery trace of Dionysian epiphanies. Involved in the game of magical transformations of Dionysus, they lose the languid bliss of the everyday "I", acquiring in return hundreds of images animated by the presence of God. Thus, Nietzsche had every right to exclaim: “…Among the Hindus I was the Buddha, in Greece I was the Dionysus; Alexander and Caesar are my incarnations, so is Shakespeare's poet Lord Bacon; in the end, I was also Voltaire and Napoleon, possibly Richard Wagner. .. Besides, I hung on a cross; i Prado; I am also Prado's father; I venture to say that I am also Lesseps and Shambij; I am every name in history."

.. Besides, I hung on a cross; i Prado; I am also Prado's father; I venture to say that I am also Lesseps and Shambij; I am every name in history."

The peak and the abyss have merged into one. The abyss, calling the abyss, closes in a preexistence embrace, plunging the person who has experienced this shock into a state of entasis, deep self-contemplation; every line between Dionysus and Apollo, Zeus and Hades disappears - only the divine game, continuous metamorphosis remains. The person himself, being in such a state, goes mad. A return to a normal state, where a person again becomes a prisoner of social models and acceptable behavioral reactions, is no longer possible. The one who returns is unable to endure the revealed squalor of the objective world; he begins to look for "gaps", gaps through which the sounds of the divine paean can be let in. To do this, he does not need to go in search of a "new heaven". The way through the abyss to the top and the way through the top to the abyss are the same. After Nietzsche had this experience, he refused to pretend. His only diagnosis is boundless honesty.

After Nietzsche had this experience, he refused to pretend. His only diagnosis is boundless honesty.

The author of the article "Nietzsche: The Will to Madness" expresses a bold idea - Nietzsche deliberately plunged into a state of madness. He crossed the Rubicon and cut off his path to return.

Richard Shane is a thinker who left the scientific world to pursue independent philosophy. Three authors had a decisive influence on him: Friedrich Nietzsche, who showed how to “write with blood”; Nikolai Berdyaev, who taught him to distinguish philosophy from science; Fernando Pessoa, who demonstrated that one can engage in intellectual activity without paying attention to wealth and fame. Shane refers philosophy to the world of art, not science, and here he is incredibly close to Yakov Golosovker. The direction in which he prioritizes, he calls radical metaphysics. Shane, in addition to numerous publications, has a very interesting project - philosophical maxims "dwelling" in the spatial structure of wall art boards (art boards). This idea goes back to the classical period of Greek philosophy, when the walls at Delphi and other shrines were covered with philosophical Graphai, inscriptions. Let us recall, for example, the famous gnomes (sayings) of the seven wise men, carved on the wall of the Delphic temple. Philosophical maxims, according to Richard Shane, turn intuition into a short linguistic expression. And the essence of this expression is more like an art object than like discursive or descriptive prose.

This idea goes back to the classical period of Greek philosophy, when the walls at Delphi and other shrines were covered with philosophical Graphai, inscriptions. Let us recall, for example, the famous gnomes (sayings) of the seven wise men, carved on the wall of the Delphic temple. Philosophical maxims, according to Richard Shane, turn intuition into a short linguistic expression. And the essence of this expression is more like an art object than like discursive or descriptive prose.

For Shane, a philosopher is an artist. However, I would like to add that not every artist is a philosopher. Of course, Nietzsche was an exception - an artist who argued that "the existence of the world can only be justified as an aesthetic phenomenon", and a philosopher who embarked on the path of the most difficult self-overcoming, who did not seek solace in philosophy. He knew that philosophy never consoled anyone, it put a person in front of a high risk of thinking, stigmatized its adherents, led to the line where the question of arche, primary potentialities, cosmogonic forces became decisive and at the same time inevitable. Philosophy does not bring any consolation, it is designed to DISTURB (!) "Dare to take up philosophy" said Schelling. “Knowledge requires courage, wisdom and power; courage, for it is dangerous; wisdom, for it commands only him to follow; power, for the next one already belongs to him alone,” insisted Rabelais. As for the fate of Nietzsche, who not only did not avoid danger, but also deliberately sought it, it turned out to be the best possible, because at the end of his life he comprehended the merger of peak and abyss.

Philosophy does not bring any consolation, it is designed to DISTURB (!) "Dare to take up philosophy" said Schelling. “Knowledge requires courage, wisdom and power; courage, for it is dangerous; wisdom, for it commands only him to follow; power, for the next one already belongs to him alone,” insisted Rabelais. As for the fate of Nietzsche, who not only did not avoid danger, but also deliberately sought it, it turned out to be the best possible, because at the end of his life he comprehended the merger of peak and abyss.

Nietzsche: The Will to Madness

Around the last week of December 1888, Friedrich Nietzsche must have fallen into complete madness. Many reasons have been given for his mental disorder. The thesis advanced in this article is that Nietzsche made a conscious decision to experience "madness". Evidence of this can be found in his published writings, correspondence and personal circumstances. Like the insane Mr. Hyde in Robert Louis Stevenson's The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, there was no way back to so-called "normality" for him. Since mid-November, a year earlier, Nietzsche's letters openly reveal his thoughts about breaking with reality, as well as about something majestic and grandiose, which turned out to be excessive even for a person like him. But a total break did not seem to occur until December 31, when he sent a letter to August Strindberg, in which he announced that he intended to shoot the young Kaiser and added that they needed to get a divorce. Signature: Nietzsche-Caesar (“I convened an assembly of hereditary monarchs in Rome, I want to shoot the young Kaiser. Goodbye! For we will meet again. But on one condition: We will get a divorce ...” - translator’s note). Subsequently, during the first week of January 1889a year later, he sent at least a dozen letters and perhaps a few more short notes to friends, former colleagues, and the King of Italy announcing his madness. The last long letter, dated 6 January, was sent to Jacob Burckhardt in Basel.

Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, there was no way back to so-called "normality" for him. Since mid-November, a year earlier, Nietzsche's letters openly reveal his thoughts about breaking with reality, as well as about something majestic and grandiose, which turned out to be excessive even for a person like him. But a total break did not seem to occur until December 31, when he sent a letter to August Strindberg, in which he announced that he intended to shoot the young Kaiser and added that they needed to get a divorce. Signature: Nietzsche-Caesar (“I convened an assembly of hereditary monarchs in Rome, I want to shoot the young Kaiser. Goodbye! For we will meet again. But on one condition: We will get a divorce ...” - translator’s note). Subsequently, during the first week of January 1889a year later, he sent at least a dozen letters and perhaps a few more short notes to friends, former colleagues, and the King of Italy announcing his madness. The last long letter, dated 6 January, was sent to Jacob Burckhardt in Basel. It frightened both Burckhardt and Nietzsche's longtime friend Franz Overbeck, who also received the "mad" message. On the advice of the Basel psychiatrist, Professor Ludwig Wille, it was decided that Overbeck should immediately go to Turin to rescue Nietzsche.

It frightened both Burckhardt and Nietzsche's longtime friend Franz Overbeck, who also received the "mad" message. On the advice of the Basel psychiatrist, Professor Ludwig Wille, it was decided that Overbeck should immediately go to Turin to rescue Nietzsche.

When Overbeck arrived at Nietzsche’s chamber on January 8, he described the state in which he found his friend in a letter to Peter Gast (aka Heinrich Köselitz):

, - as it turned out later, the last proofreading of Nietzsche contra Wagner. He looked completely downcast. Seeing me, he rushes to me, impulsively embraces me, tears gushed from his eyes, shaking with sobs, he again sinks onto the sofa, I myself cannot stand on my feet from the shock. Did the abyss in which he is, or rather, into which he fell, open up to him at that moment? In any case, this did not happen again. The whole Fino family was present at this, as soon as Nietzsche, groaning and shuddering, was again on the sofa, they gave him bromine standing on the table to drink. He calmed down instantly and began to talk with a laugh about the big reception that was allegedly being prepared this evening. At the same time, he was in captivity of some crazy illusions, from which he never freed himself again until our parting. Regarding me and all other people in general, all this time he kept complete clarity, about himself he was in the dark. For example, several times, singing loudly and pounding on the piano keys, with some frenzy shouted out fragments of those ideas in the world of which he had been living lately, and at the same time, in short phrases uttered in an indescribably strangled voice, he gave out thin, amazingly sharp-sighted and unspeakably terrible things about himself as the heir of a dead God, as if placing punctuation marks in them with the sounds of a piano, after which convulsions and explosions of inexpressible suffering again followed.

He calmed down instantly and began to talk with a laugh about the big reception that was allegedly being prepared this evening. At the same time, he was in captivity of some crazy illusions, from which he never freed himself again until our parting. Regarding me and all other people in general, all this time he kept complete clarity, about himself he was in the dark. For example, several times, singing loudly and pounding on the piano keys, with some frenzy shouted out fragments of those ideas in the world of which he had been living lately, and at the same time, in short phrases uttered in an indescribably strangled voice, he gave out thin, amazingly sharp-sighted and unspeakably terrible things about himself as the heir of a dead God, as if placing punctuation marks in them with the sounds of a piano, after which convulsions and explosions of inexpressible suffering again followed.

(translated by I.A. Ebanoidze. Nietzsche, Friedrich. Letters / Comp., translated from German by I. A. Ebanoidze. - M: Cultural Revolution, 2007.).

A. Ebanoidze. - M: Cultural Revolution, 2007.).

In his letter to Gast, Overbeck omitted some details. For example, the fact that Nietzsche danced naked in the room, and his dance was reminiscent of ancient rituals of sacred sexual madness. Note that all this left Overbeck with no doubt that his friend had experienced an absolute mental breakdown. He arranged to be taken to Basel immediately. There, Nietzsche quickly entered the Basel Psychiatric Clinic, headed by Dr. Wille. He was diagnosed with progressive paralysis (general paresis), a common diagnosis in psychiatric clinics of that era. In 1888, it was suspected that progressive paralysis was a late manifestation of syphilis. At 19In the year 02, when Nietzsche gained fame (he died in 1900), a monograph by the prominent neuropathologist Paul Möbius was published, in which it was first publicly disclosed that Nietzsche suffered from general paresis, a syphilitic brain lesion, which led to insanity. Since then, the general medical conclusion has been that Nietzsche suffered from syphilis (which had a late onset) and, as a result, brain degeneration, which was expressed in the alternation of euphoria with emotional instability. The only question is: did he have this disease or not, and how could it affect his philosophical activity? Opinions on this matter differed.

The only question is: did he have this disease or not, and how could it affect his philosophical activity? Opinions on this matter differed.

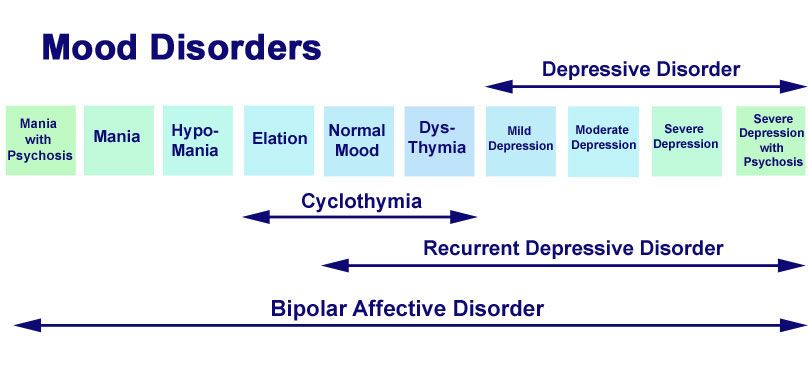

Doubts were often expressed about the validity of the diagnosis. The course of Nietzsche's disease was not typical of the usual course of general paresis. This diagnosis in the 19th century became a common "paper basket" and was made to many people with an unspecified neuropsychiatric disease. With the advent of laboratory diagnosis of syphilis, the number of diagnosed cases has rapidly decreased. Other reasons have been cited to explain Nietzsche's nervous breakdown: drugs (his sister's version), latent cerebrovascular disease, schizophrenia, manic depressive illness, frontotemporal degeneration, and even Lyme disease. None of these assumptions has gained general acceptance.

There are good reasons to believe that Nietzsche's "madness" was not caused by any external agent, nor by any internal mental disorder. It was an act of will. Many indications in his past and in his writings suggest that this was the case. In one of his earliest published books, Dawn, or Thoughts on Moral Prejudices (1881), written after Nietzsche left his professorship at Basel, one finds a passage entitled "The Significance of Madness in the History of Morals":

Many indications in his past and in his writings suggest that this was the case. In one of his earliest published books, Dawn, or Thoughts on Moral Prejudices (1881), written after Nietzsche left his professorship at Basel, one finds a passage entitled "The Significance of Madness in the History of Morals":

“If, despite that terrible oppression of moral customs under which humanity began to live several millennia before our era, if, despite this, more and more new thoughts, views, goals constantly arose, then this happened with terrible accompaniment: almost everywhere madness paved the way for new thoughts; it also broke respected customs and superstitions.”

(translated by V.M. Bakusev)

Further in the same fragment:

"Ah, give me madness, gods! Madness for me to believe in myself! give me convulsions and delirium, instantly change light and darkness, frighten me with cold and heat, such as no mortal has ever experienced, frighten me with noise and wandering shadows, make me howl, squeal, crawl on the ground, but only give me faith in yourself ! Doubt devours me, I killed the law, the law frightens me, as a corpse frightens a living person; if I am not more than the law, the most reprobate of men. "

"

(translated by V. M. Bakusev)

I wonder if this is the scenario of what followed seven years later in the book of Nietzsche's own life. The following essay, "Merry Science" (1882), contains a passage in the same spirit, but much more depressing, despite the title of the book:

"Homo poeta. I myself, I who created this tragedy of tragedies with my own hands, to the extent that it is ready; I, who for the first time tied the knot of morality into existence and tightened it so much that only some god could unravel it - this is exactly what Horace demands! - I myself have now destroyed all the gods in the fourth act - for moral reasons! What will come out of the fifth now! Where else to get a tragic denouement! "Shouldn't I start thinking about a comic denouement?"

(translated by K.A. Svasyan)

E.F. Podach believes that Nietzsche found this denouement in a passage from Beyond Good and Evil:

only continuous proof that a long, genuine tragedy is over—assuming that all philosophy in its origin was a long tragedy. ”

”

(translated by N. Polilov)

I will quote the last passage - although there are others - from Nietzsche's work "Beyond Good and Evil" already mentioned here. He is full of a mood of extreme pessimism:

“The death, the fall of higher people, alien souls, is precisely the rule: it is terrible to have such a rule constantly before our eyes. The manifold torments of the psychologist who discovered this doom, who once discovered and then almost continuously re-discovers throughout history this general inner "incurability" of the higher man, this eternal "too late!" in every sense, may perhaps one day become the reason that he will violently rise up against his own fate and make an attempt to destroy himself - that he himself will "perish".

(translated by N. Polilov)

You can find other evidence of his craving for madness in the correspondence of late December and early January. A hint of his intentions is easy to spot in a letter to Peter Gast dated December 16th. In the middle of the letter, he suddenly remarks sharply: “I don’t understand why I had to hasten the tragic catastrophe of my life that began with Esse so much.” But then Nietzsche probably changed his mind, since in a letter to Gast dated December 31 he writes: “Ah, friend! What a moment! When your postcard arrived, what was I doing?... It was the famous Rubicon... I no longer know my address: let's suppose that soon it will be the Palazzo del Quirinale."

In the middle of the letter, he suddenly remarks sharply: “I don’t understand why I had to hasten the tragic catastrophe of my life that began with Esse so much.” But then Nietzsche probably changed his mind, since in a letter to Gast dated December 31 he writes: “Ah, friend! What a moment! When your postcard arrived, what was I doing?... It was the famous Rubicon... I no longer know my address: let's suppose that soon it will be the Palazzo del Quirinale."

This is a very important announcement. The Rubicon was the fatal river in Italy through which Julius Caesar led his legion to eventually become Emperor. It marks the point of no return for those who cross it. Nietzsche identified himself with Caesar and signed a letter to Strindberg with the double name "Nietzsche-Caesar". We have reason to believe that for Nietzsche the Rubicon meant a transition into madness, a break with reality. Nietzsche never wrote anything that did not make sense for his own life.

In Europe, August Strindberg was perhaps the most able person to understand Nietzsche at that time. Like Nietzsche, he was a brilliant and versatile writer. He had just gone through a difficult period of mental illness, which he used to write two of his most outstanding works. Nietzsche and Strindberg admired each other's writings, and Nietzsche even asked Strindberg to translate his "Ecce Homo" into French. However, Strindberg was forced to refuse due to financial circumstances, due to which he never found the opportunity to meet with his friend.

Like Nietzsche, he was a brilliant and versatile writer. He had just gone through a difficult period of mental illness, which he used to write two of his most outstanding works. Nietzsche and Strindberg admired each other's writings, and Nietzsche even asked Strindberg to translate his "Ecce Homo" into French. However, Strindberg was forced to refuse due to financial circumstances, due to which he never found the opportunity to meet with his friend.

When Strindberg received one of Nietzsche's "mad" letters, he immediately understood its meaning. He responded with a quote in Latin and Greek:

Carissime Doctor!

Qelw, Qelw manhuaz!

Litteras tuas non sine perturbatione accepi et tibi gratias ago.

Rectius vives, Licini, neque altum

Semper urgendo, neque dum procellas0131

Litus iniquum.

Interdum juvat insanire!

Vale et Fave!

Strindberg (Deus, optimus, maximus).

Transfer:

Holtibus, on the eve of Jan. 1889.

Dear doctor!

I want, I want to go crazy!

I received your letters not without excitement. Thank you.

You will live properly, Licinius, as soon as you start

You will no longer go to the open sea and, fearing a storm of verses,

You will not approach such a dangerous shore.

It's nice, however, to fool around!

Be healthy and supportive!

Strindberg (God, best, greatest) (lat., other Greek).

(translated by I.A. Ebanoidze)

But Nietzsche did not follow the advice of Horace (and Strindberg). What may have originally been a "simulation" of insanity eventually became a fixed state that left no chance to return to "normal" life.

It is noteworthy that in the first week of January 1889 Nietzsche sent several messages to his publisher C. G. Naumann in Leipzig. Clear, concise, without any trace of madness. In them, he gives instructions about the urgent publication of "Ecce Homo", anticipating the publication of "Nietzsche contra Wagner", and about the return of two poems: "Send me the poem that stands at the end, as well as the last poem sent to you" Glory and Eternity ". Forward with "Ecce"!" Herr Gast received notification of a change of plans. Characteristically, Nietzsche's last letter ends with the words: "The address is the same, Turin." Two days before, in his letter to Peter Gast about crossing the Rubicon, he said that he no longer knew his address, and perhaps it was the Palazzo del Quirinale. In the midst of his "crazy" letters, Nietzsche could obviously, if he wanted to, write the most ordinary letter. Shortly after his arrival in Basel, he was placed in a psychiatric clinic in Jena to be constantly near his mother's house (although she was allowed to see her son only occasionally). Nietzsche was under the tutelage of Otto Binswanger, a well-known neuropsychiatrist and specialist in the pathology of neurosyphilis.

G. Naumann in Leipzig. Clear, concise, without any trace of madness. In them, he gives instructions about the urgent publication of "Ecce Homo", anticipating the publication of "Nietzsche contra Wagner", and about the return of two poems: "Send me the poem that stands at the end, as well as the last poem sent to you" Glory and Eternity ". Forward with "Ecce"!" Herr Gast received notification of a change of plans. Characteristically, Nietzsche's last letter ends with the words: "The address is the same, Turin." Two days before, in his letter to Peter Gast about crossing the Rubicon, he said that he no longer knew his address, and perhaps it was the Palazzo del Quirinale. In the midst of his "crazy" letters, Nietzsche could obviously, if he wanted to, write the most ordinary letter. Shortly after his arrival in Basel, he was placed in a psychiatric clinic in Jena to be constantly near his mother's house (although she was allowed to see her son only occasionally). Nietzsche was under the tutelage of Otto Binswanger, a well-known neuropsychiatrist and specialist in the pathology of neurosyphilis. He remained in the clinic for 14 months. Hospital records for this period, detailed by E.F. Submission, indicate that Nietzsche behaved noisily, often violently, inconsistently and, apparently, was in an absolutely delusional state.

He remained in the clinic for 14 months. Hospital records for this period, detailed by E.F. Submission, indicate that Nietzsche behaved noisily, often violently, inconsistently and, apparently, was in an absolutely delusional state.

Shortly after entering the clinic in Jena, Peter Gast visited Nietzsche and found that his friend looked pretty good. In a letter to their common comrade Karl Fuchs, he writes:

“I saw Nietzsche in such states when it seemed to me with eerie distinctness that he was feigning madness, that he was glad that everything had ended like that!”

He believed that Nietzsche “would be as grateful to his saviors as a man who jumped into the water to drown himself would be grateful to that idiot from the Coast Guard who pulled him ashore” (E.F. Podach). Overbeck expressed a similar view in a later publication: "I cannot get rid of the disturbing suspicion that arises in me at certain moments, namely, that he is feigning madness. This impression can only be explained by the general understanding I had about Nietzsche, about his self-concealment, his spiritual mask. But even here I bow to the facts that take precedence over all personal thoughts and speculations. However, what Overbeck considered to be facts is highly doubtful.

This impression can only be explained by the general understanding I had about Nietzsche, about his self-concealment, his spiritual mask. But even here I bow to the facts that take precedence over all personal thoughts and speculations. However, what Overbeck considered to be facts is highly doubtful.

Nietzsche was released from the clinic and placed in the care of his mother in March 1890 years. He lived for another 10 years. At first, he could take long walks with his mother, but at the same time, he was characterized by outbursts of rage. There was one thing left from his past life that he could still do - improvisation on the piano. But gradually Nietzsche fell into apathy and became bedridden. Some visitors who had the honor of seeing the philosopher spoke of the strange "aura" that seemed to surround him. In August 1900, he developed a cold that quickly progressed to pneumonia. He died on 25 August 1900, six weeks before his 56th birthday. Strangely enough, no autopsy was performed, despite numerous questions about the cause of his nervous breakdown (and even though his physician, Dr. Binswanger, was an authority on brain pathology).

Binswanger, was an authority on brain pathology).

His sister Elisabeth Nietzsche gave a magnificent funeral. Many pretentious "anti-Nietzschean" words were spoken at the ceremony. A more appropriate and concise epitaph could be the one that Horatio composed for Hamlet in Shakespeare's play. Hamlet was Nietzsche's favorite literary character. His association with masks, buffoonery and suicide makes him the philosopher's alter ego.

“The lofty spirit has died. Sleep, sweet prince.

Sleep, lulled by the singing of cherubs!”

At the time of his destruction, Nietzsche was almost unknown to anyone, except perhaps a few people outside of Germany. But soon after he entered the psychiatric institution, the German press reported on a philosopher who had gone mad and was institutionalized. Interest in Nietzsche and his writings began to grow. Like a match placed on a woodpile, Nietzsche's glory began to engulf the world in its flames - first Germany, and then other countries of Europe. The clever publicity spawned by his sister, who seized the philosopher's literary heritage, certainly hastened this process. By the time of his death, Nietzsche had gained fame. German soldiers during World War I were reported to have carried copies of Thus Spoke Zarathustra in their duffel bags. And all this happened at a time when Nietzsche himself was in the grip of a deep apathy and was not even able to realize his glory. Perhaps it was the most poignant tragedy in his life.

The clever publicity spawned by his sister, who seized the philosopher's literary heritage, certainly hastened this process. By the time of his death, Nietzsche had gained fame. German soldiers during World War I were reported to have carried copies of Thus Spoke Zarathustra in their duffel bags. And all this happened at a time when Nietzsche himself was in the grip of a deep apathy and was not even able to realize his glory. Perhaps it was the most poignant tragedy in his life.

More than a century after his death, it is still impossible to say with absolute certainty that we know the cause of his mental disorder. Perhaps this is not so important, because it was his writings, and not his personality, that had a profound impact on the literary world. But people want to know about the lives of the writers who raised them to new dimensions of thought. It is quite possible that without Nietzsche's madness, his writings would have sunk into oblivion or been reduced to a few footnotes in scientific treatises. Whatever the root cause of his madness, it played its part. At that time, Nietzsche lived in very cramped conditions (one rented room), he had neither friends nor relatives nearby, he had a very mediocre command of the language of the country in which he lived. His Basel pension was shrinking, his books were not being sold; he had to pay for the publication of his writings. Probably Nietzsche was, as he himself claimed, three-quarters blind. All of these factors must have been putting pressure on him (despite his protestations that they weren't) and they most likely contributed to the decision to fall out of the "normal" world, although Nietzsche may not have been fully aware of what the consequences might be.

Whatever the root cause of his madness, it played its part. At that time, Nietzsche lived in very cramped conditions (one rented room), he had neither friends nor relatives nearby, he had a very mediocre command of the language of the country in which he lived. His Basel pension was shrinking, his books were not being sold; he had to pay for the publication of his writings. Probably Nietzsche was, as he himself claimed, three-quarters blind. All of these factors must have been putting pressure on him (despite his protestations that they weren't) and they most likely contributed to the decision to fall out of the "normal" world, although Nietzsche may not have been fully aware of what the consequences might be.

Probably even more important was the understanding that he, the herald of the Superman, the will to power, the domination of instincts, was only a meek, insignificant, almost blind German philosopher, whom no one then paid attention to. His several clumsy attempts to have sexual relations ended in sad failures. What if he was a unique German writer-stylist? What if he had a few dedicated, if distant, readers? German intellectuals ignored or laughed at him. He rejected metaphysics, so no god could help him anymore. Zarathustra was a figment of his imagination, not a reality. As a classical philologist, he had long known that Plato taught that for a philosopher, madness surpasses ordinary reason, and Nietzsche has dealt with this topic repeatedly in his books. The desire to assert oneself through madness must have been very great. For all the reasons given here, this article argues that Nietzsche deliberately entered the halls of madness. Finally, he crossed his Rubicon.

What if he was a unique German writer-stylist? What if he had a few dedicated, if distant, readers? German intellectuals ignored or laughed at him. He rejected metaphysics, so no god could help him anymore. Zarathustra was a figment of his imagination, not a reality. As a classical philologist, he had long known that Plato taught that for a philosopher, madness surpasses ordinary reason, and Nietzsche has dealt with this topic repeatedly in his books. The desire to assert oneself through madness must have been very great. For all the reasons given here, this article argues that Nietzsche deliberately entered the halls of madness. Finally, he crossed his Rubicon.

The question may arise whether any person is capable of voluntarily putting himself into a state of permanent insanity (and not into a state of transient insanity, or into a temporary clouding of reason and loss of contact with the "real" world). The currently generally accepted psychiatric point of view is that chronic psychoses of unknown origin (“madness”) are caused by an anomaly in the functioning of the brain, which involuntarily affects the human psyche.