Psychology meditation techniques

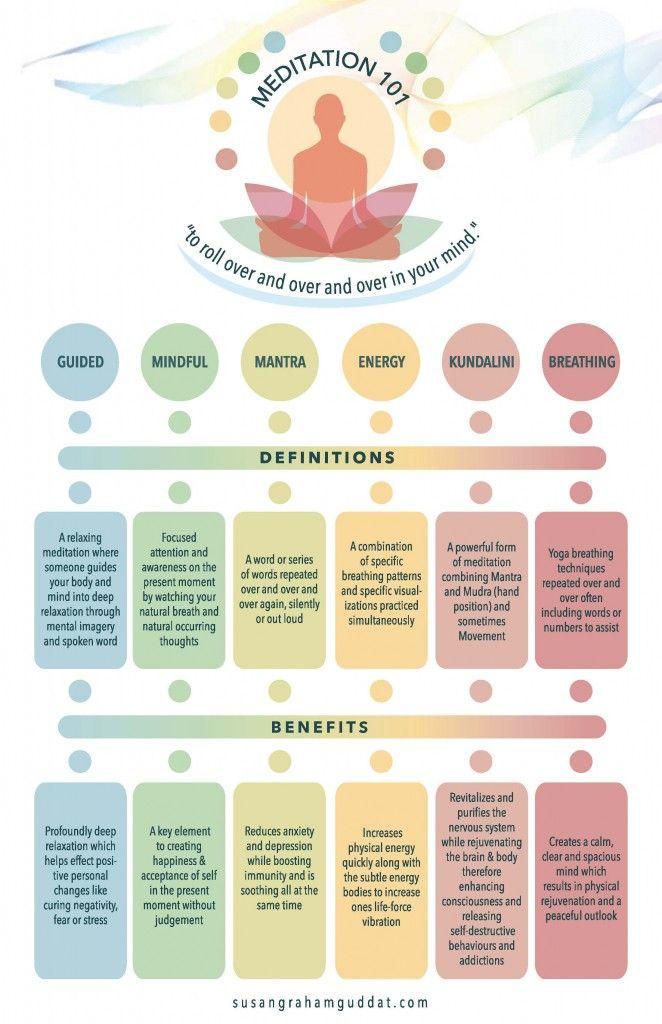

Five Meditation Techniques Used by Mental Health Professionals

- Guided Imagery

- Progressive Muscle Relaxation

- Hypnosis

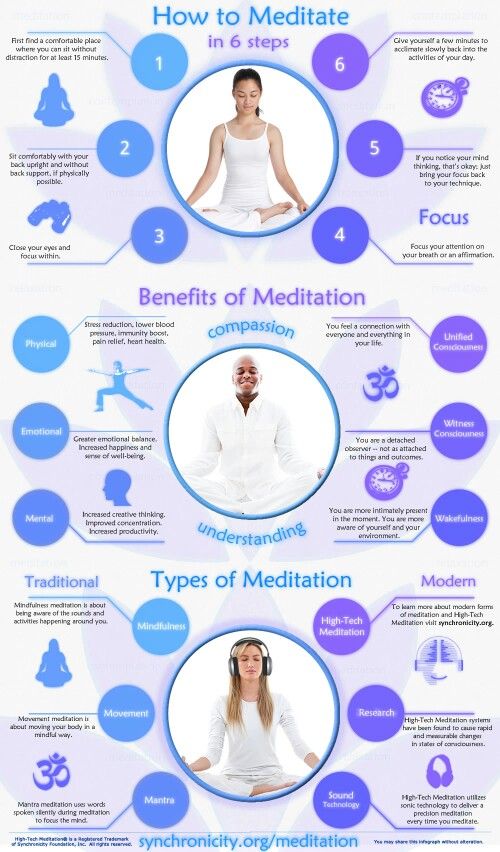

- Mindfulness Meditation

- Focused Breathing

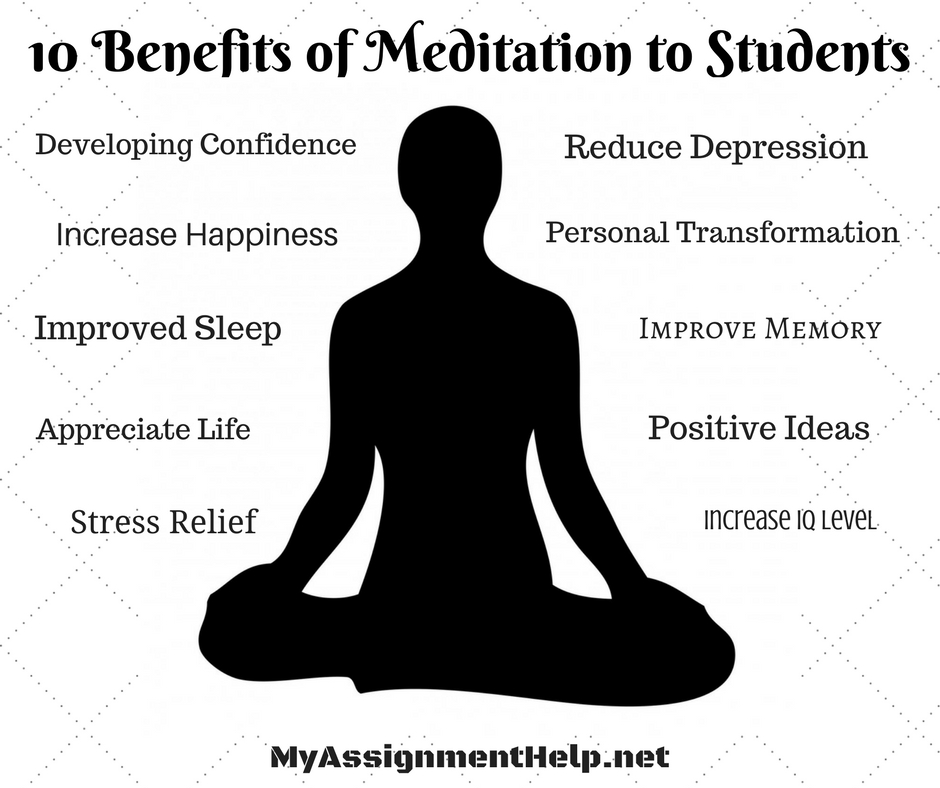

Now is an exciting time to become a mental health professional! Increasingly, therapists are including meditation techniques in their treatment plans. Regular meditation helps clients achieve the goals of counseling. Here are five therapeutic methods and how to employ them in your future practice.

The Relaxation Response

All types of meditation share the same objective – prompting a relaxation response. This is a deeply serene state, induced by the release of calming hormones. In a quiet setting, by fixing one’s attention on a single object, a person receives immense benefit.

The mind grows still, muscles relax, and blood pressure gradually drops. Breathing and heart rate slow. Neurons in the brain forge new connections.

These physiologic changes help clients better manage challenges. Following is an overview of guided imagery, progressive muscle relaxation, hypnosis, mindfulness meditation, and focused breathing.

1. Guided Imagery

For this meditation method, the therapist leads a client in visualizing pleasing objects or scenes. For guided imagery to be effective, the counselor must first take a thorough client history. Then, knowing what objects relax a patient, the counselor suggests images on which to focus.

Here’s an example. With eyes closed, a patient is asked to picture a peaceful beach on a sunny day. Next, sensory impressions are explored. The client describes the sights, sounds, and aromas evoked by the scene.

To conjure the sense of texture, the counselor might ask, “What does the sand feel like on your bare feet?” The therapist may also play instrumental music that complements the visualization. The goal is to mentally engage all five senses, if possible.

Meanwhile, the counselor observes the client for signs of contentment, such as changes in posture, facial expression, and voice tone. As breathing slows, muscles loosen, and mental activity wanes.

As breathing slows, muscles loosen, and mental activity wanes.

Applications

Therapists may teach guided imagery in both private and group sessions. This technique is effective for treating anxiety, grief, addiction, depression, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It can aid quitting smoking and reduce the awareness of pain.

For instance, a cancer patient might picture vibrant cells and organs glowing inside them. An arthritic client can soften pain by turning down the volume on an imaginary radio. Positive visualizations can diffuse relationship tension and resolve family issues. In this way, guided imagery is both relaxing and helpful in achieving a desired outcome.

Training

Certification in guided imagery is available. To be eligible, you must first earn your degree and obtain licensure as a mental health professional. Then, apply to the Academy for Guided Imagery. The course involves 33 hours of independent study and 150 hours of formal training, which you can complete in two years. You can opt to select a home-study module or participate in group study online.

You can opt to select a home-study module or participate in group study online.

2. Progressive Muscle Relaxation (PMR)

With this type of meditation, the therapist instructs the client to tense a muscle group, hold the contraction for 15 seconds, and then release it while slowly exhaling. After a brief pause, the therapist addresses another muscle group. This process is repeated systematically, beginning with the toes and ascending to the head.

Muscles are gently tightened, not to the point of strain. After each pause, the client notes the sensory difference between tautness and relaxation. At the end of PMR, a client feels body-wide tranquility.

Applications

Through PMR, clients gain self-awareness of muscle tension when under stress. Then, they can choose to relax tight muscles and quell unpleasant emotions, such as anxiety, anger, and frustration. Following are two examples.

- When upset, a client habitually clenches their fists.

After learning PMR, they can catch themselves, and release their agitation.

After learning PMR, they can catch themselves, and release their agitation.

- A client suffers from chronic headaches. After mastering PMR, they can sense the initial tensing of their neck and shoulders. By pausing to relax the involved muscles, they avoid the pain cycle.

Additionally, PMR can alleviate panic attacks, social anxiety, PTSD, and insomnia.

3. Hypnosis

This technique is similar to guided imagery. However, hypnosis emphasizes verbal suggestions, rather than sensory engagement. Therapists use this meditation technique to help clients adopt new habits, change behaviors, and relieve symptoms.

First, the therapist leads the client into a “hypnotic trance,” a state of deep relaxation. Then, the client receives goal-oriented suggestions.

Initially, mental health professionals may dedicate entire sessions to hypnosis. Then, at subsequent visits, hypnosis occupies 15 minutes of treatment time. Once a client is fully versed in the technique, they can practice self-hypnosis independently.

Applications

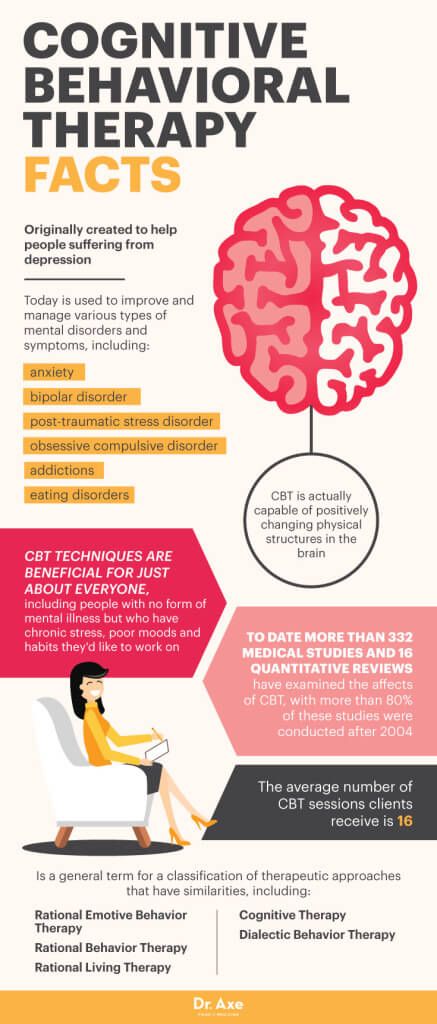

Some therapists make audio tapes for their patients. They may also use hypnosis in group therapy. Research shows that this meditation technique enhances cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for anxiety, phobias, addiction, and stress management.

For example, for a client struggling to quit smoking, the therapist might state that the habit is no longer enjoyable. As a post-hypnotic suggestion, the counselor could plant the idea that whenever the patient reaches for a cigarette, the desire to smoke evaporates.

Training

After becoming a licensed mental health professional, you can obtain training at any of the following professional hypnosis organizations.

- American Society of Clinical Hypnosis – To be eligible for training and certification by the ASCH, you must have a master’s degree in clinical psychology or counseling.

- Hypnosis Motivation Institute – This college is accredited for teaching hypnosis therapy.

- Milton H. Erikson Foundation – This federally supported non-profit corporation provides hypnosis training for mental health therapists worldwide.

- Society for Clinical and Experimental Hypnosis – Members of this organization include psychologists, social workers, and psychiatrists.

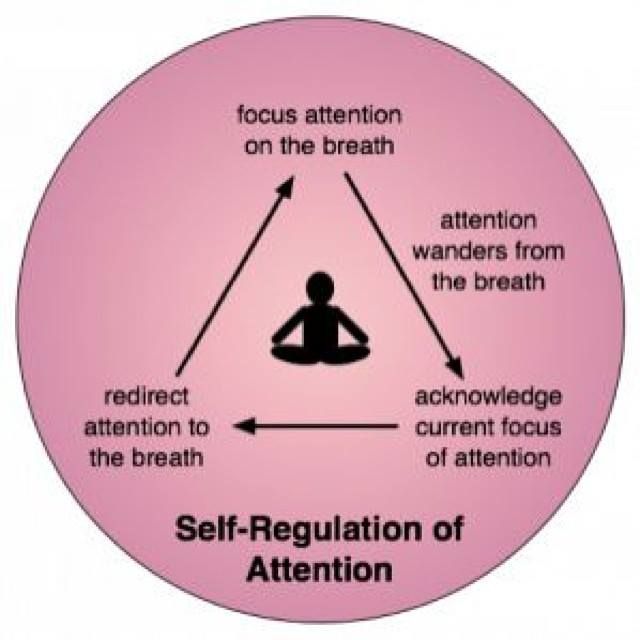

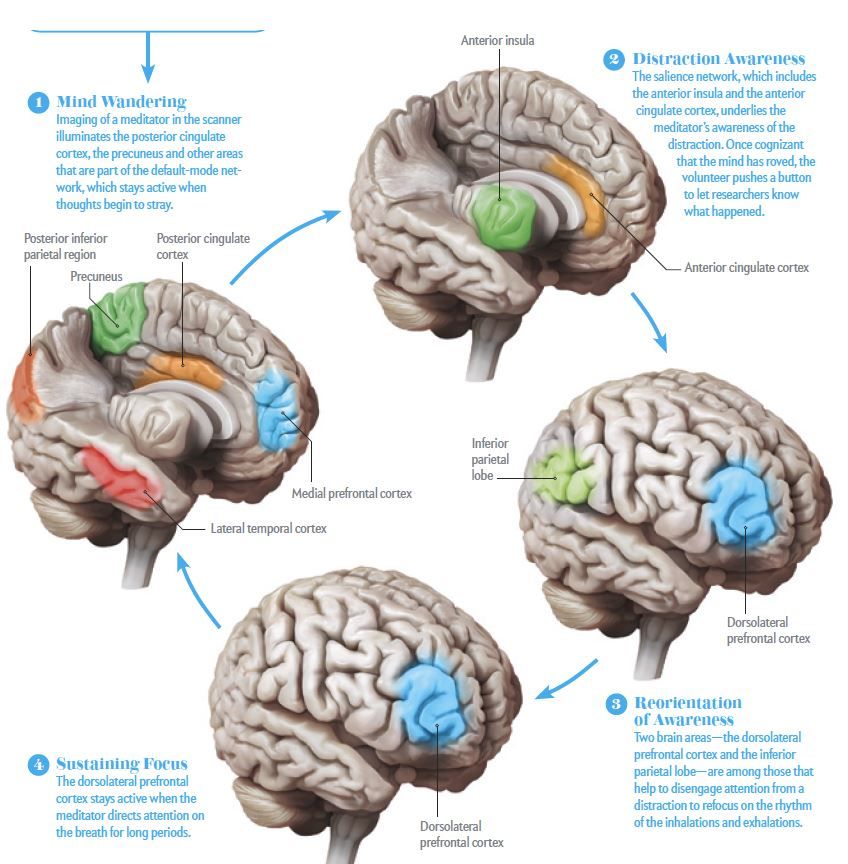

4. Mindfulness Meditation

This technique involves watching thoughts, emotions, and sensations, without reacting to them. Counselors specializing in CBT often teach mindfulness, to help clients control negative thinking.

To instruct a client in mindfulness meditation, the therapist directs them to focus on a particular object. When thoughts cause attention to waver, the client observes them, like clouds floating by, without judgment. Then, they draw their mind back to the anchor. Examples of mental anchors for meditation are the sound of a ticking clock or a pleasing image.

Once a client becomes skilled in mindfulness meditation, they’re encouraged to maintain this stance throughout their daily lives. By calmly watching thoughts, patients acquire the ability to change their beliefs and behaviors.

By calmly watching thoughts, patients acquire the ability to change their beliefs and behaviors.

Applications

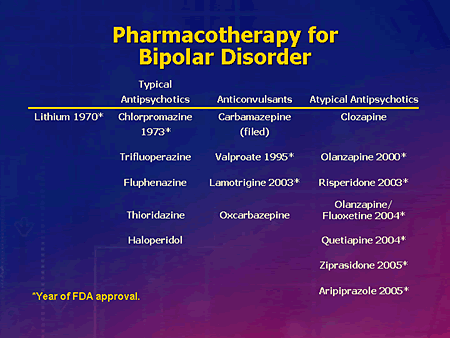

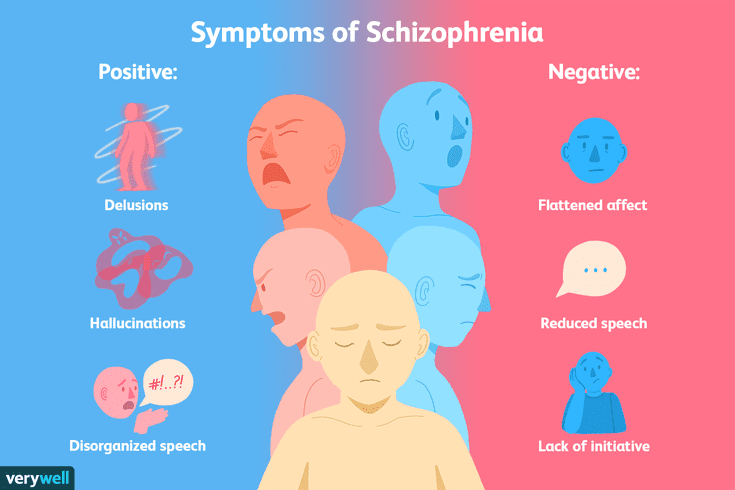

Mental health professionals use this meditation method to treat anxiety, PTSD, depression, eating disorders, panic attacks, suicidal ideation, addiction, poor self-image, and bipolar disorder. This technique works by bridging new neural networks in the brain.

5. Focused Breathing

This type of meditation is also called paced respiration, alternate nostril breathing, and belly, abdominal, deep, slow, and diaphragmatic breathing. During deep inhalations, air expands the lungs, and the lower abdomen rises. Breathing is done slowly, gently, and smoothly.

While following the breath, a meditator scans their body for tense areas, such as the jaw, lips, and shoulders. Then, during the out-breath, they sequentially release the tightness in each body region. While breathing in, they focus on the vitalizing sensation.

Alternate nostril breathing involves isolating the in-breath and out-breath, one nostril at a time. First, you close one nostril with your thumb, and breathe through the open nostril. Then, you switch the process. Using the same hand, close the other nostril with your index finger, and slowly inhale and exhale.

First, you close one nostril with your thumb, and breathe through the open nostril. Then, you switch the process. Using the same hand, close the other nostril with your index finger, and slowly inhale and exhale.

You can also pair slow breathing with counting. The in-breath is shorter than the out-breath. For example, during the inhale, the meditator can steadily count to four. The out-breath is done to a count of eight.

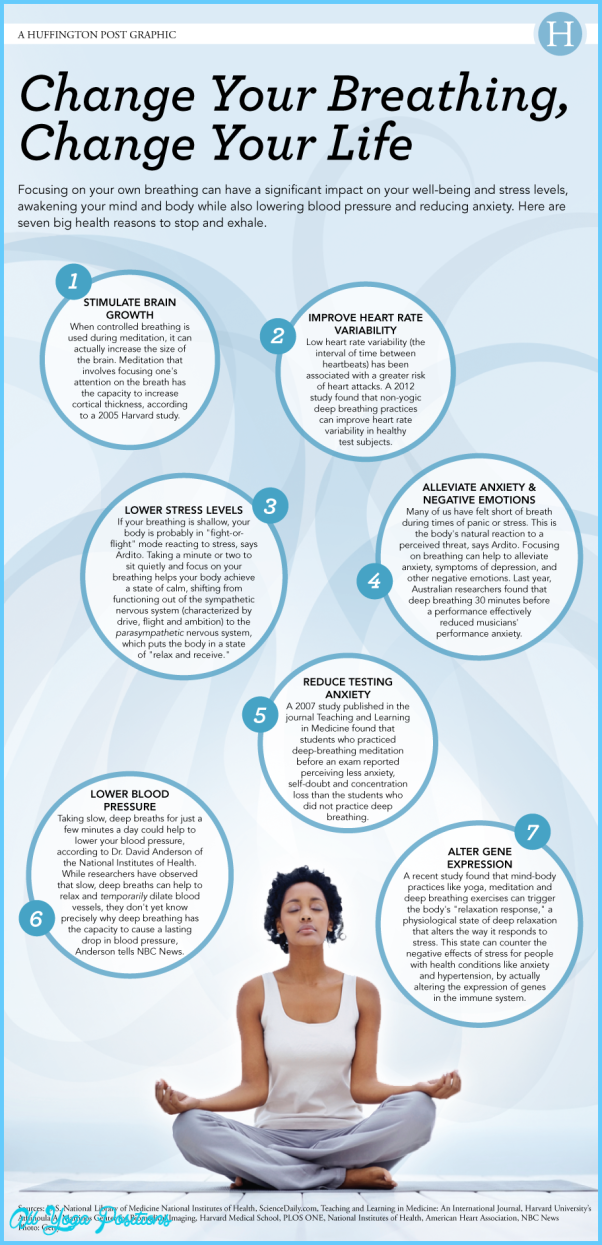

Applications

Physiologic benefits of paced respiration include heightened alertness, lower blood pressure, and slower heart rate. Similar to mindfulness meditation, this practice helps clients distance themselves from distressing thoughts and feelings.

Therapists use this meditation technique to treat patients with anxiety, panic attacks, and PTSD. Slow breathing also helps to control bipolar disorder, addiction, and insomnia.

- From a 2011 issue of the Journal of Evidence-Based Complementary & Alternative Medicine, here are case study examples of mental health professionals using meditation techniques.

Amazing Breakthroughs!

Mental health professionals use meditation techniques to foster positive change in their patients. After becoming licensed, you won’t need additional training to teach progressive muscle relaxation, mindfulness meditation, or focused breathing. To practice guided imagery, you may want to obtain training and certification. To employ hypnosis with clients, you’ll need formal instruction by a professional hypnosis organization.

As a counselor, you can use these meditation methods to fuel your clients’ progress. You’ll be so heartened by their breakthroughs!

Related resources:

- 20 Best Online ABA Master’s Degree Programs 2020

- 10 Best ABA PhD Degree Programs 2020

- 10 Best Online ABA Degree Programs (Bachelor’s) 2020

- Top 20 Online Master’s in Educational Psychology 2020

- Top 30 Online Master’s in School Counseling 2020

- 10 Best Online RBT (Registered Behavioral Technician) Training Programs 2020

- 10 Best ABA Master’s Degree Programs 2020

- 10 Best ABA Master’s Degree Programs in the East 2020

- 10 Best ABA Master’s Degree Programs in the West 2020

- 20 Most Affordable Online ABA Graduate Certificate Programs 2020

- 5 Podcasts for Educational Psychologists

- 5 TED Talks About Mental Health

- 5 Conditions that Benefit from ABA Therapy

- Five Podcasts for Applied Behavior Analysts

- Five Most Common Mental Health Conditions in America

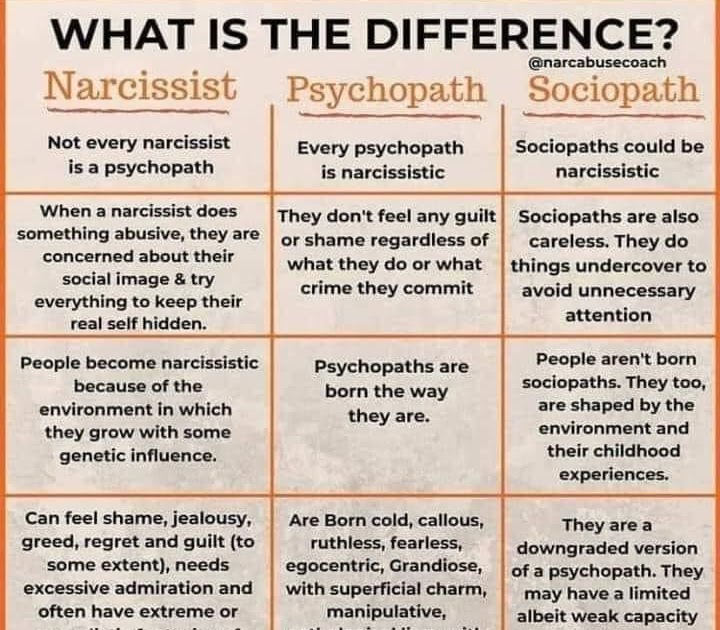

- Five Most Common Personality Disorders

Meditation in psychotherapy - Harvard Health

An ancient spiritual practice is finding new uses in the treatment of mental illness.

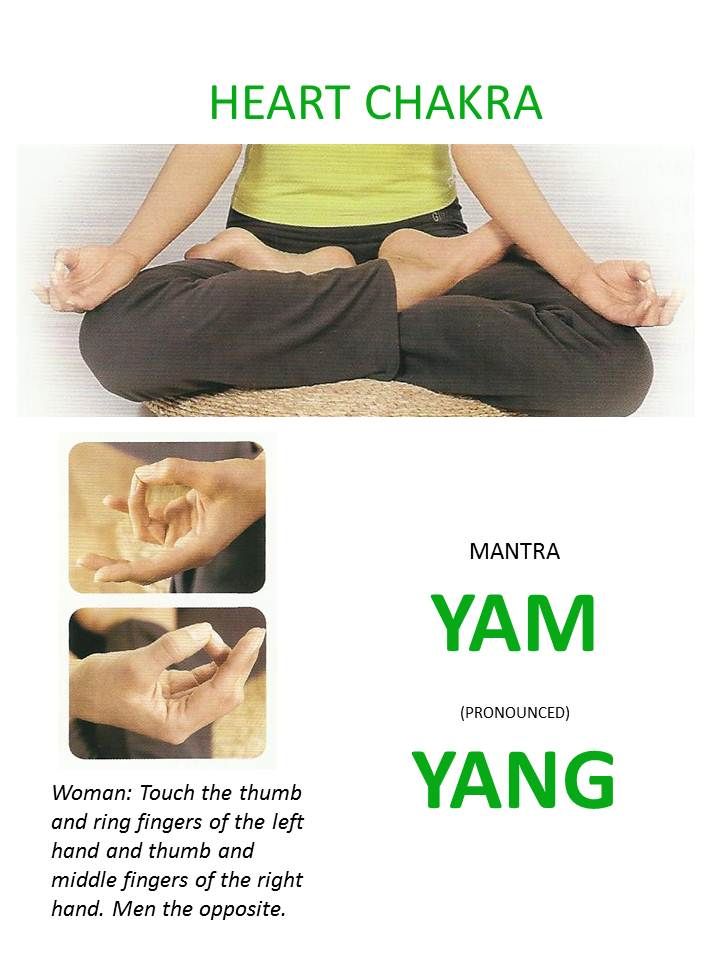

The systematic method of regulating attention known as meditation is now being incorporated into psychotherapeutic practice and linked in surprising ways to other healing traditions, including cognitive behavioral therapy. The most highly developed forms of meditation are associated with Buddhism, but there are parallels in other spiritual and religious traditions, as well as modern secular versions under the names of relaxation response training or mindfulness meditation.

One typical practice is to choose a word, sound, or short phrase (sometimes called a mantra) and repeat it with each breath while sitting in a relaxed position with eyes closed, while calmly dismissing distracting thoughts and feelings. In the slightly different mindfulness meditation, there is less emphasis on the mantra. Practitioners sit and remain aware of their breathing while observing thoughts and feelings as they come and go in a quiet and detached way. If they notice that their attention is wandering, they are supposed to observe the process without trying to disengage from it and simply return to awareness of their breathing. The rule is not to fight it — whatever internal state "it" may be — and not to encourage it either. The aim is to suspend habits of selecting, judging, and interpreting, and attend to the present moment without allowing oneself to be distracted by fantasies, memories, and anxieties.

The rule is not to fight it — whatever internal state "it" may be — and not to encourage it either. The aim is to suspend habits of selecting, judging, and interpreting, and attend to the present moment without allowing oneself to be distracted by fantasies, memories, and anxieties.

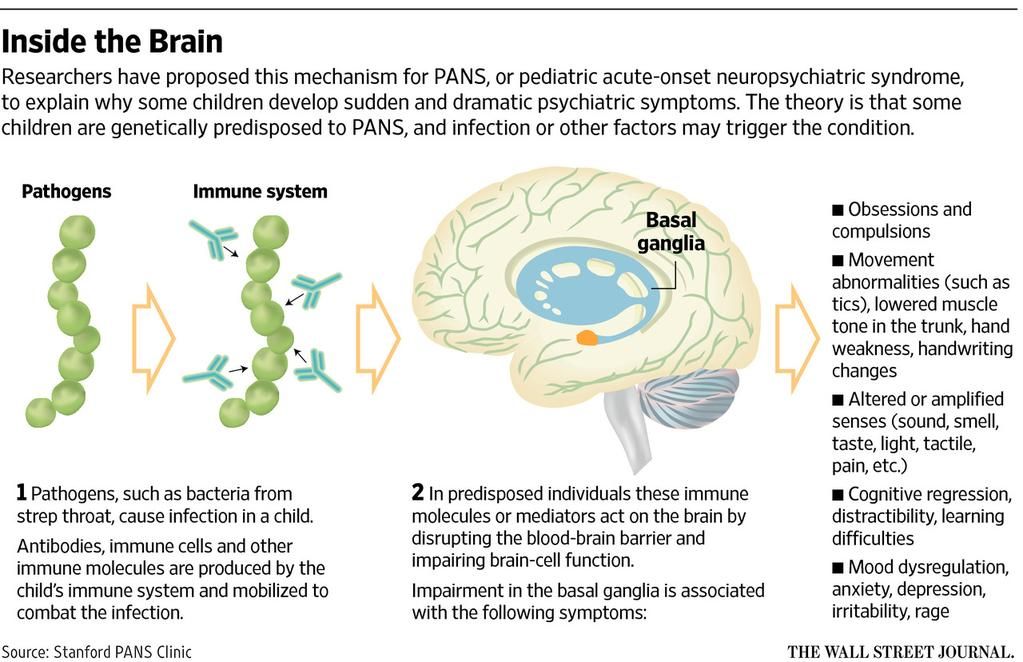

There is evidence that these practices have distinct effects on the brain. In one study, brain scans indicated that Buddhist monks who were longtime meditators, compared with controls who had just a week of training, showed a high proportion of a type of brain wave that reflects large-scale coordination of neural circuits. In another recent study, researchers measured brain electrical activity before, immediately after, and four months after a two-month course in mindfulness meditation. They found persistent increased activity on the left side of the prefrontal cortex, which is associated with joyful and serene emotions. They also found increased antibody responses to an influenza vaccine. Studies are now looking at the effects of meditation on the amygdala, the brain's fear center, and the caudate nucleus, which is associated with obsessional thoughts and compulsive behavior.

Psychotherapeutic uses

In meditative traditions, the purpose of drawing attention away from the outside world and abandoning habitual patterns of perceiving and thinking is to facilitate personal change. The focused attention, self-forgetfulness, and heightened awareness of body states are supposed to open the mind to decreased preoccupation with one's own suffering, a move from self-deception to self-understanding, and resulting changes in attitudes and behavior.

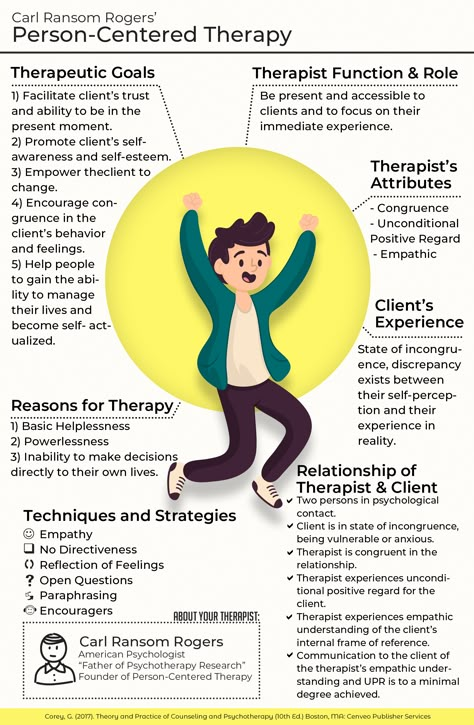

The resemblance to the aims of psychotherapy is no accident, as practitioners of both traditions increasingly recognize. But the psychotherapeutic tradition now taking meditation most seriously, to the surprise of some, is cognitive behavioral therapy.

Behavioral theory and therapy in their original forms were concerned only with stimulus and response and tangible rewards and punishments. Making almost no reference to the mind or internal experience and concentrating on action, behaviorism was seemingly at the farthest possible remove from meditation. But eventually the need to take account of thoughts and feelings became apparent, and behavior therapy was enhanced by cognitive techniques — testing, questioning, and correcting irrational thinking, and the use of observational learning and problem-solving strategies.

But eventually the need to take account of thoughts and feelings became apparent, and behavior therapy was enhanced by cognitive techniques — testing, questioning, and correcting irrational thinking, and the use of observational learning and problem-solving strategies.

The purpose of cognitive behavioral therapy is to change self-defeating ways of thinking about the world, the self, and the future. Cognitive therapists analyze what they call thought schemas, underlying attitudes that are not explicit and mostly out of awareness: Everyone must like me or I will die lonely and unmourned; if I'm not perfect I am a failure; it is always best to assume the worst; anyone who tells me what to do is saying that I am incompetent. These schemas are the basis for automatic misinterpretations of everyday situations: My heart is beating so fast that I must be having a heart attack; he will snub me, so I must cross the street to avoid him.

Pessimistic and self-deprecating explanations become self-fulfilling prophecies, as they result in selective attention to anxiety-provoking and depressing experiences. The cognitive therapist helps patients bring schemas and automatic thoughts to awareness so that they can be questioned and alternatives can be offered.

The cognitive therapist helps patients bring schemas and automatic thoughts to awareness so that they can be questioned and alternatives can be offered.

Now some therapists have gone further, contemplating a merger between cognitive techniques and meditation that they call the "third wave" of cognitive behavioral therapy. Some names given to the new approaches are dialectical behavior therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy, and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy.

The new tendency began with dialectical behavior therapy, which uses standard behavioral and cognitive techniques along with mindfulness meditation in a form of individual and group treatment originally developed to prevent self-mutilation and suicide attempts in women with borderline personality. Dialectical behavior therapy has also been used for eating disorders, addictions, and other conditions. Marsha Linehan, the originator of the technique, refers to a "dialectic of acceptance and change" in which meditation serves as a means for the patient to accept feelings that she has been rejecting because family members and friends have declared them unjustified or invalid.

Acceptance and commitment therapy, developed by Stephen Hayes and others, further breaks down the distinction between cognitive behavioral therapy and older spiritual teachings. Its motto is, "Control is the problem, not the solution." The idea is that to suppress or avoid bad feelings and depressing thoughts only makes matters worse by, in effect, committing oneself to an internal war. The goal of therapy should be to change the patient's relationship to symptoms rather than treat them as an enemy to be eliminated. The patient must accept without struggling — "don't fight it" — anxious and depressing thoughts, even hallucinatory voices. In that way, according to the theory, they will eventually lose their power. This truce in the internal battle is well captured by what the Buddha is supposed to have said: "Pitting what you like against what you do not like is a disease of the mind."

Acceptance and commitment therapists oppose what they call cognitive fusion and experiential avoidance. Cognitive fusion is an effect of our need for networks of words and concepts. For example, a person constantly worries about or is even terrified by many places and situations that bear some resemblance to the situation in which a panic attack occurred. Trying to prevent or suppress this cognitive fusion directly is impossible because it brings to mind what you are trying to avoid. A favorite example is the impossible demand, "Do not think about a white bear." A person who tries not to feel anxious will become anxious about the anxiety; a person trying hard to sleep will only make the insomnia worse.

Cognitive fusion is an effect of our need for networks of words and concepts. For example, a person constantly worries about or is even terrified by many places and situations that bear some resemblance to the situation in which a panic attack occurred. Trying to prevent or suppress this cognitive fusion directly is impossible because it brings to mind what you are trying to avoid. A favorite example is the impossible demand, "Do not think about a white bear." A person who tries not to feel anxious will become anxious about the anxiety; a person trying hard to sleep will only make the insomnia worse.

The solution recommended is to loosen the grip of language and generalization by promoting the opposite — experiential acceptance and cognitive defusion. Cognitive behavioral therapists have always believed that the first step is distancing oneself from depressive and anxious thoughts, treating them objectively as events in the world — much in the way meditation works. Cognitive therapists go on to question the content of the thoughts and test their validity in real-life situations, but some research suggests that the distancing has the most profound therapeutic effects.

Cognitive therapists go on to question the content of the thoughts and test their validity in real-life situations, but some research suggests that the distancing has the most profound therapeutic effects.

Acceptance and commitment therapy rejects the assumption that what needs to be changed is the content of a thought or feeling. Anxiety is not the problem in anxiety disorders, according to this theory, and thoughts are not the problem in thought disorders. The reason for wanting relief from anxiety or depression is to live a better life. But trying to eliminate specific symptoms does not accomplish that end.

The alternatives include meditation and a variety of mental exercises, metaphors, and stories that resemble Zen paradoxes and parables. For example:

-

Think of your good feelings and your bad feelings as the players holding the white and black pieces in a chess game. Struggling against your bad feelings means joining a meaningless and futile contest with yourself.

-

Imagine your situation as a tug-of-war in which you are pulling harder and harder against an opponent who is dragging you toward a pit. Instead you have to drop the rope.

-

Sit and picture thoughts passing through your mind in the form of words on signs held by people in a parade you are watching from a reviewing stand. Eventually you may find that you can't keep your thoughts on that kind of helpful distance. Back up and try to recall what you were thinking when the shift occurred. Then try again.

-

Imagine that you are connected to a device that infallibly detects anxiety. Would this help you avoid or control the anxiety, or would the effort simply create more discomfort?

Eventually, commitment is supposed to follow acceptance. The therapist uses standard cognitive behavioral therapy techniques such as establishing goals for behavior change and working toward those goals in small steps. But the emphasis is on what patients must do, not on what they must not do, and the aim is to enhance the overall quality of life rather than concentrate on eliminating specific kinds of behavior. For example, to establish goals, the therapist might ask a patient to write out what she would most like to hear in a eulogy delivered at her funeral.

For example, to establish goals, the therapist might ask a patient to write out what she would most like to hear in a eulogy delivered at her funeral.

Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy uses similar methods to prevent relapse in depressed patients and avoid the need for indefinite use of antidepressant drugs. It is based on the idea that a patient who has recovered from depression remains vulnerable because of associations the mind has learned. Any sadness, disappointment, or frustration reactivates pessimism, self-deprecation and gloomy generalizations about failure, weakness, and worthlessness, which in turn exacerbate the mood in a vicious downward spiral. It happens in the same way that reminders of the drug experience put recovered addicts in peril of re-addiction.

The therapy is conducted in weekly group sessions, with daily homework, several months after the patient has recovered and stopped taking antidepressant drugs. The therapist helps patients disengage from self-defeating thoughts. Instead of struggling against depressive thoughts, patients are asked to adopt an attitude of detached "kindly curiosity" that resembles the experience cultivated in mindfulness meditation. They are taught to notice when mood begins to change and break the chain of depressive thinking by observing thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations as they come and go.

Instead of struggling against depressive thoughts, patients are asked to adopt an attitude of detached "kindly curiosity" that resembles the experience cultivated in mindfulness meditation. They are taught to notice when mood begins to change and break the chain of depressive thinking by observing thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations as they come and go.

Therapeutic effects

Both meditation and the psychotherapeutic methods that incorporate it have been used in a variety of ways to improve physical and mental health. Meditation techniques are applied to relieve discomfort in physical conditions including psoriasis, irritable bowel syndrome, fibromyalgia, and rheumatoid arthritis. A combination of yoga and meditation with diet has been claimed to reverse coronary artery disease. Mindfulness meditation has also been used to enhance well-being in people with early breast and prostate cancer; to decrease criminal offenses committed by juvenile delinquents; to help women with binge eating disorder; and to relieve stress and depression in people caring for dementia victims. It has been proposed for the treatment of addiction, phobias, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

It has been proposed for the treatment of addiction, phobias, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Controlled studies have shown that dialectical behavior therapy can lower the rate of self-mutilation and suicidal behavior in women with borderline personality disorder. In one study, acceptance and commitment therapy helped psychotic patients dismiss their hallucinatory voices and reduced the rehospitalization rate by 50% over four months. In another study, depressed patients who received mindfulness-based cognitive therapy were only half as likely to relapse as those who had only standard counseling and medication. These methods have also been used in the treatment of eating disorders, work-related stress, and addictions.

Different types of psychotherapy are becoming more alike as they borrow ideas and techniques from one another, and therapists may use several different approaches with a single patient. For example, the methods of cognitive therapists are often compared to the analysis of rationalization, denial, and other ego mechanisms of defense in psychodynamic therapy. This tendency toward eclecticism and integration is encouraged by evidence that many forms of psychotherapy are equally effective. The incorporation of practices derived from meditation in the third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy could be another stage in a historical process that is transforming psychotherapy.

This tendency toward eclecticism and integration is encouraged by evidence that many forms of psychotherapy are equally effective. The incorporation of practices derived from meditation in the third wave of cognitive behavioral therapy could be another stage in a historical process that is transforming psychotherapy.

| Resources Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Web Site www.acceptanceandcommitmenttherapy.com Center for Mindfulness in Medicine, Health Care, and Society, University of Massachusetts Medical School508-856-2656www.umassmed.edu/cfm Mind/Body Medical Institute617-632-9543www.mbmi.org National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institutes of Health888-644-6226 (toll free)nccam.nih.gov |

| References Bach P, et al. Brown KW, et al. "The Benefits of Being Present: Mindfulness and Its Role in Psychological Well-Being," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology (April 2003): Vol. 84, No. 4, pp. 822–48. Hayes SC, et al., eds. Mindfulness and Acceptance: Expanding the Cognitive-Behavioral Tradition. Guilford Press, 2004. Kabat-Zinn J, et al. "Effectiveness of a Meditation-Based Stress Reduction Program in the Treatment of Anxiety Disorders," American Journal of Psychiatry (July 1992): Vol. 149, No. 7, pp. 936–43. Teasdale JD, et al. "Prevention of Relapse/Recurrence in Major Depression by Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy," Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (Aug. For more references, please see /mentalextra. |

Meditation: three techniques used by psychologists

104,094

Anti-stress

“It is like endless rest. It is better than the deepest sleep. It is a calming of the mind that sharpens everything, especially the perception of your surroundings. Meditation makes life fresh,” Hugh Jackman describes his twenty years of meditation experience. The actor captured the essence of the process, which the Dalai Lama calls "the path of bliss", with amazing accuracy.

Meditation in Buddhism is the basis of spiritual practices. Many psychologists have adopted meditative techniques, but not everyone knows what a variety of results can be achieved with their help.

“In the West, meditation is perceived solely as a way to bring oneself to a state of peace. But its possibilities are wider. Moreover, if you engage in peace meditation too much, you can, on the contrary, become too nervous, says Orientalist philosopher Andrey Paribok. - In the practice of meditation, we achieve the ability to control the spontaneous flow of consciousness, to direct attention to a specific object. As a result, if an emotional or mental turmoil arises, one who owns meditative techniques can interrupt it, not allowing the spontaneous mind to mock itself.

- In the practice of meditation, we achieve the ability to control the spontaneous flow of consciousness, to direct attention to a specific object. As a result, if an emotional or mental turmoil arises, one who owns meditative techniques can interrupt it, not allowing the spontaneous mind to mock itself.

Shamatha - achieving concentration

Shamatha is one of the main types of meditation. According to psychologist Daniel Goleman, it aims to return the mind to a point of highest concentration, which he calls focus.

Daniel Goleman notes that in the process of meditation, the frontal lobes of the brain, which are responsible for self-control and will, are “pumped”. In our world, where information flows from the screens of smartphones, TV screens, billboards, from the pages of newspapers, it is extremely important to learn to stop, prioritize and move towards the goal.

Meditation becomes a tool that helps us calm the storm and focus on the essentials

Due to distraction, we may notice too late that life has turned into chaos. We are like a boat in the middle of a hurricane and we can hardly get the situation under control.

We are like a boat in the middle of a hurricane and we can hardly get the situation under control.

Meditation becomes the tool that helps calm the storm and focus on the most important, standing in the position of an observer. Experienced practitioners warn that the effect is not achieved immediately, but as a result of regular training: it should be done daily, at about the same time, gradually increasing the intensity of the exercises.

Technique #1 Mind Concentration Exercise

Take time, find a place where you won't be disturbed, sit comfortably with your back straight, close your eyes and focus on your breathing. Inhale and exhale, and inhale and exhale again. Our consciousness is rhythmic, this respiratory cycle will be pleasant to it. Watch how the air enters and exits through the nose, fills the lungs and diaphragm. Feeling distracted, gently come back.

Most likely, thoughts and memories will distract you. It `s naturally. Just bring yourself back to tracking your breath. At the end of the practice, slowly open your eyes, sit a little longer, thank yourself for the practice.

At the end of the practice, slowly open your eyes, sit a little longer, thank yourself for the practice.

Working with emotions

Buddhist teaching pays great attention to working with emotions. It comes from the fact that anger and envy cloud the mind, while love and joy ennoble it. Compassion for others is a mandatory quality for a Buddhist. Practices of generosity and caring for others are impossible for someone who is immersed in a state of despondency or anger.

Meditation helps to expand the emotional range, enhance the experience of joy, happiness, unconditional love and acceptance in relation to the world and people. Compassion, rejoicing and equanimity Buddhist teachers recommend practicing together, as one feeling supports the other.

Technique #2 Metta Meditation, or Loving-Kindness Meditation

This practice is especially valuable if you want to change your relationships with others so that they become more warm and understanding.

Find a quiet place, sit up straight, close your eyes. Concentrate on your breath for the first couple of minutes, watching your mind settle down. When extraneous thoughts stop filling your mind, wish yourself joy, health, happiness. Say to yourself: “I wish myself to be happy”, “I wish myself health”. It is better to pronounce these words in time with the breath. If you start to have negative feelings, dissolve them into an experience of self-love.

Concentrate on your breath for the first couple of minutes, watching your mind settle down. When extraneous thoughts stop filling your mind, wish yourself joy, health, happiness. Say to yourself: “I wish myself to be happy”, “I wish myself health”. It is better to pronounce these words in time with the breath. If you start to have negative feelings, dissolve them into an experience of self-love.

Then imagine your best friend or loved one. Give him love, wish him happiness and health. If you feel tension in the body, observe it, slowly dissolving it in a state of joy and love. Imagine a friend: a colleague, a salesperson from a nearby store, a neighbor - someone to whom you are neutral, and wish him happiness and kindness, freedom and joy. It is difficult to feel love for a stranger, but gradually, in the process of practice, it will become easier to do this.

The most difficult thing is to wish happiness to someone who is unpleasant to you. But this is also the most important thing in developing loving-kindness. Actor Richard Gere, who has been fascinated by Buddhism for many years, mentally wishes every person happiness, and this, according to him, gives joy, first of all, to himself.

Actor Richard Gere, who has been fascinated by Buddhism for many years, mentally wishes every person happiness, and this, according to him, gives joy, first of all, to himself.

A sincere wish for good and health to someone who has done bad things to you is a real breakthrough in mastering emotions. And this is the penultimate stage of metta meditation, after which you can wish happiness to all living beings. Stay in this state, observe the changes that have happened to you. Thank yourself for the practice.

Analytical Meditation

Once you have mastered the ability to focus on your breath, you can move on to the next level of meditation. It refers to the practice of Vipassana, aimed at developing awareness and wisdom. The essence of analytical meditation is concentration on an object, internal or external, in order to develop a certain quality, such as compassion.

Meditation is not a static exercise that is performed in the same way every time

“Analytical meditation in the East is just reflection,” Andrey Paribok clarifies, “but at the same time, the one who thinks strives to take a position above the situation. For example, in meditation, the thought comes to him: "Ivan is a bad person." But he does not dwell on it, does not “hang”, but notes that such a thought came to him, but this is just an assessment. He looks at this assessment from the outside, gradually disengaging from it. The task is not to cling to the thought, to the object, but to let them go.”

For example, in meditation, the thought comes to him: "Ivan is a bad person." But he does not dwell on it, does not “hang”, but notes that such a thought came to him, but this is just an assessment. He looks at this assessment from the outside, gradually disengaging from it. The task is not to cling to the thought, to the object, but to let them go.”

You can think about different things — about life and death, about the happiness of loved ones and your own, about the importance of caring in this world. It is important to choose a specific topic, focus on it, and concentrate on the breathing cycle, which will help maintain focus.

Technique #3 Empathy Meditation

Sit up straight. Begin by doing the practice of focusing on the breath and calming the stream of consciousness. When you feel ready, focus on a specific thought. For example, think of a time when you suffered and someone took care of you. What feelings did you have? What did this person feel? How did it change him?

Recall a time when you showed concern for someone. What was the reaction? What did you feel about it? Think how many sentient beings suffer every day. Wish them deliverance from suffering, mentally lend a helping hand. Be in a state of meditation for as long as necessary.

What was the reaction? What did you feel about it? Think how many sentient beings suffer every day. Wish them deliverance from suffering, mentally lend a helping hand. Be in a state of meditation for as long as necessary.

Breathe in and out a few times, come back gently. Thank yourself for the practice. In the future, note the quality that you have in the process of meditation, and develop it.

Meditation is not a static exercise that is done the same way every time. As the spiritual growth of the practitioner, the technique becomes more complicated. Her ultimate goal will be to constantly use this way of thinking in order to experience life in all its colors.

Text:Daria YaushevaPhoto Source:Getty Images

New on the site

“Reason is the only peaceful weapon”: Albert Einstein’s 5 life lessons

“We love each other, but something always gets in the way. Is the relationship worth it?

"A man doesn't propose, and I don't want to be a cohabitant"

"Napoleon complex" really exists. Who should beware?

Who should beware?

How to stop being afraid of death: 3 tips - observations from a nursing home

Incest, abuse, sexual abuse: why it is so difficult to remember childhood traumas

"18 is childhood": a psychologist explains why this is so why swearing becomes part of everyday vocabulary

Three Techniques of Meditation - Psychology PRO

I haven't talked about meditation for a long time. Sometimes they ask for advice on some technique for self-soothing. I noticed that I advise almost everyone the same soft type of meditation. I decided to describe it on the site, preceded by a review article.

I'll start with a little explanation of what meditation is not. Settle in a benign atmosphere, tune in a positive way, listen to the new age, burn incense, smoke a hookah, dynamically jump and yell in a semi-trance, mentally attract money and sexual partners - all this, anything, but not meditation.

Of course, there are many techniques, and almost all of them, in their purest form, come down to contemplation. At the same time, external attributes are deeply secondary.

At the same time, external attributes are deeply secondary.

What follows is how I understand the main types of meditation. This is not a retelling of canonical texts, but just how my mind began to interpret the consequences of personal practice - a kind of private esotericism. And if you want classical descriptions, read yogic and Buddhist primary sources.

One-pointed meditation - psychic drill

This is a classic meditation technique to keep the attention fixed. For this purpose, any phenomenon that can be seen, heard, or touched is used: a point on the wall, the tip of the nose, a burning candle, internal and external sounds, mantras.

If everyday, jumping from thought to thought, scattered perception is focused in a single channel, the same effect occurs when quantity turns into quality - attention undergoes a kind of quantum leap, igniting in a bright flash, and a person feels as if he has woken up , awakening then the trance of his everyday life.

At the same time, meditation can be likened to a laser beam, which sometimes smoothly, sometimes jerkily burns a hole in the “granite” of the unconscious. Perception overcomes the usual barriers - consciousness expands.

From contemplative one-pointed meditation, as they say among practitioners, “sausage”, “karma is cleansed”, “stresses come out”. Behind all this is something like revealing the psychic depths - yesterday's territory of the unconscious, from where the once suppressed information begins to randomly fall out - as a rule, not the most pleasant experiences.

If the practice does not stop, then the “split” can last for many years without any guarantee of completion. And this is one of the main problems that people face after meditation - sometimes constant, sometimes unexpected breaking, which can occur in any conditions.

Imagine a person who lived without any special difficulties, but decided that it would not hurt him to improve - and ordered a series of study problems for himself. And then - if you want, you don’t want, you know how, you don’t know how, you have to deal with them somehow.

And then - if you want, you don’t want, you know how, you don’t know how, you have to deal with them somehow.

Such techniques use persistent practices, for example, aiming at spiritual enlightenment. One-pointed meditation fits more organically not into urban life, but into reclusive life, like Buddhist monks under the supervision and guidance of an experienced mentor.

Meditation of dissolution – bleaching of consciousness

Meditation of dissolution is what I call practice, because, unlike classical techniques, it does not so much provoke breakthroughs of perception into psychic depths as it works to eliminate actual blockages. That is, practice does not lead to an unexpected breakdown, which you just have to endure until you let go, but rather, on the contrary, it allows you to get rid of it - it includes working through difficult experiences directly during execution.

Therefore, the role of the object of meditation this time is concrete experiences - for example, any negative emotion. At the same time, attention is not constrained by rigid unidirectional immobility, otherwise its focused beam will again drill into mental barriers, leading to unexpected "emissions" from the unconscious.

At the same time, attention is not constrained by rigid unidirectional immobility, otherwise its focused beam will again drill into mental barriers, leading to unexpected "emissions" from the unconscious.

That is, in the meditation of dissolution, attention is not focused at a point, but gently permeates the observed experience - as if tasting it in any form accessible to perception. Temporary distraction by thought is not forbidden.

Returning to the aforementioned analogy of a person who has decided to develop himself, in this case he does not order unknown problems for himself, but is taken to solving actual ones.

To this type of practice I attribute yoga nidra, a relaxation technique, and one of the vipassana meditation techniques, where attention glides over emerging bodily and sensory sensations.

I also include the self-study of Ramana Maharshi. It is necessary to explore with the help of this technique one's own "I". I have been doing this for several years with varying degrees of success. What has been revealed has already been described in the articles:

What has been revealed has already been described in the articles:

- Self-awareness of a small person

- Reality consumer

- Self-examination

This meditation technique is subtle and requires great sensitivity. Otherwise, it is impossible to grasp with attention that "sacred" substance that makes up the very core of the personality - one's own "I".

Meditative self-exploration relatively painlessly dissolves one of the main internal “problems” – images of oneself, which are guarded by fear in everyday life. I recently cited a similar technique on the site.

I can say for myself that the practice over the years really calms and in a good way empties the head. The sense of "I" becomes so elusive, as if it were not there at all. Of course, this is not yet enlightenment, but only a certain stage of simplifying one's own insides.

By enlightenment, I mean a state when the mind goes out of focus altogether, the feeling of choice with all doubts completely disappears - and you perceive yourself as a being in which everything happens spontaneously. This state of affairs is familiar to me in practice. But it is impossible to control it, and my ordinary perception personally dominates.

This state of affairs is familiar to me in practice. But it is impossible to control it, and my ordinary perception personally dominates.

At first, such experiences turn everything upside down. I remember that once life did not seem surprising to me, but was normal and understandable. Now I can hardly remember this state of normality of what is happening. Probably, one of the layers, where seriousness was projected onto life, burned out.

I, like everyone else, have all kinds of emotions. They can temporarily take over. Not the roots of emotions have disappeared, but most of the reasons for their occurrence, every year something peels off. According to my observations, when a person, in principle, systematically works on himself, then negative emotions do not so much become quieter, losing in intensity, but are reduced in time, sometimes disappearing completely from the habitually hackneyed planes. The garden is not entangled with weeds, but they are periodically found in all their glory.

Objectless meditation - resistance is useless

The most refined practice. It is emphasized and taught by Dzogchen masters, one of the schools of Tibetan Buddhism. And it is also the main one among the masters of Advaita Vedanta - the Indian philosophical system.

It is interesting that here the primordial Eastern teachings resonate with modern Western psychology, as if offering with one voice to stop remaking yourself and come to terms with yourself. Acceptance of what is happening is, in general, a universal principle of mental well-being. Whenever I mention it, I ask you not to confuse it with passivity and irresponsibility.

Sometimes the masters say that this practice is not meditation, like you don't need to meditate to become yourself. It is sometimes said that it is true meditation, and all others are only preparations for it.

We can say that objectless meditation is when consciousness is aware of itself. The famous dictum from the Indian Upanishads "thou art that" points to this subtle maneuver.

Technique is described as if it could not be approached by effort; on the contrary, it works on its own when the practitioner, as if giving up, gives up efforts and allows himself to remain in the so-called natural state.

To do this, the state of nature is first described theoretically until the viewer finally realizes that all this time it was about himself.

In this perspective, in the present, every object is being. Distinguishing objects is being. This being is just there right now.

For the implementation of the practice, you do not need to do anything, change, achieve, nothing is required other than direct awareness that you already exist here and now, you are already existence itself.

If you didn't get enlightened after these words, don't despair. Despair can be worked out by meditation of dissolution, or, for example, in communication with a psychologist.

And next time, I will probably try to describe one effective meditation technique that is relevant for about everyone.

"The Use of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to Prevent the Rehospitalization of Psychotic Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial," Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (Oct. 2002): Vol. 70, No. 5, pp. 1129–39.

"The Use of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy to Prevent the Rehospitalization of Psychotic Patients: A Randomized Controlled Trial," Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology (Oct. 2002): Vol. 70, No. 5, pp. 1129–39. 2000): Vol. 68, No. 4, pp. 615–23.

2000): Vol. 68, No. 4, pp. 615–23.