What it feels like to have adhd

What It Really Feels Like

I’m a health and business writer, author, mom of two grown adults, and the founder of a business that helps adults with learning and attention differences gain confidence, get hired, and ask for what they need to do their best work.

I see patterns, make connections, and find workarounds that others don't. My relationships—at home and at work—have benefited from my creativity, energy, and unusual skill set. But my biggest strength is sometimes also my biggest challenge.

I was diagnosed as having attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, ADHD, dyscalculia, and sensory processing disorder in my 40s. In some ways, mine is a classic story, particularly because ADHD can be challenging to diagnose in girls and adults.

It’s common to hear of parents learning of their child’s diagnosis and thinking, "Wow, that sounds a lot like me". That’s what happened when I took my then 7-year-old son to an amazing neuropsychologist.

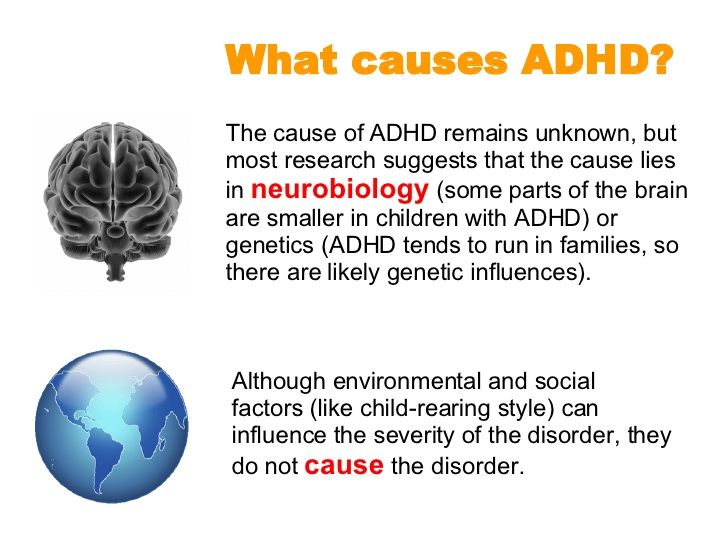

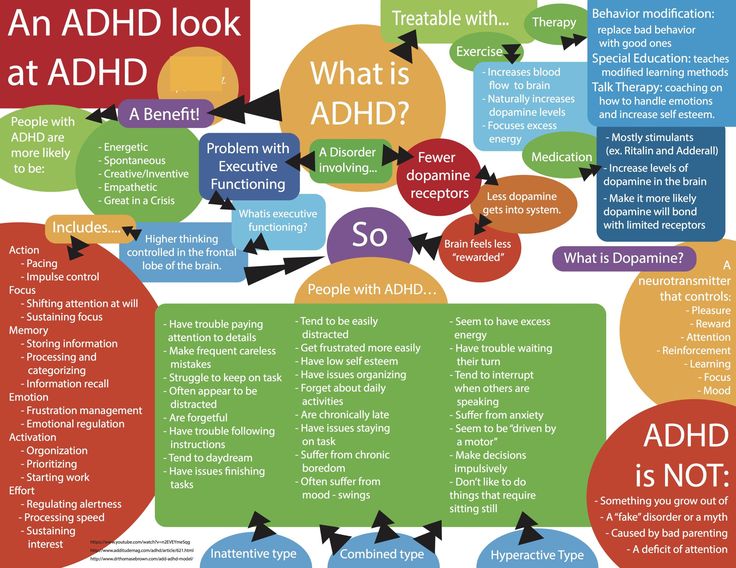

Thanks to her guidance, we learned the positives before the negatives. She explained that ADHD is a genetic, neurodevelopmental disorder, which means that the part of the brain involved in planning, focus, and follow through works differently than it does in people who are neurotypical.

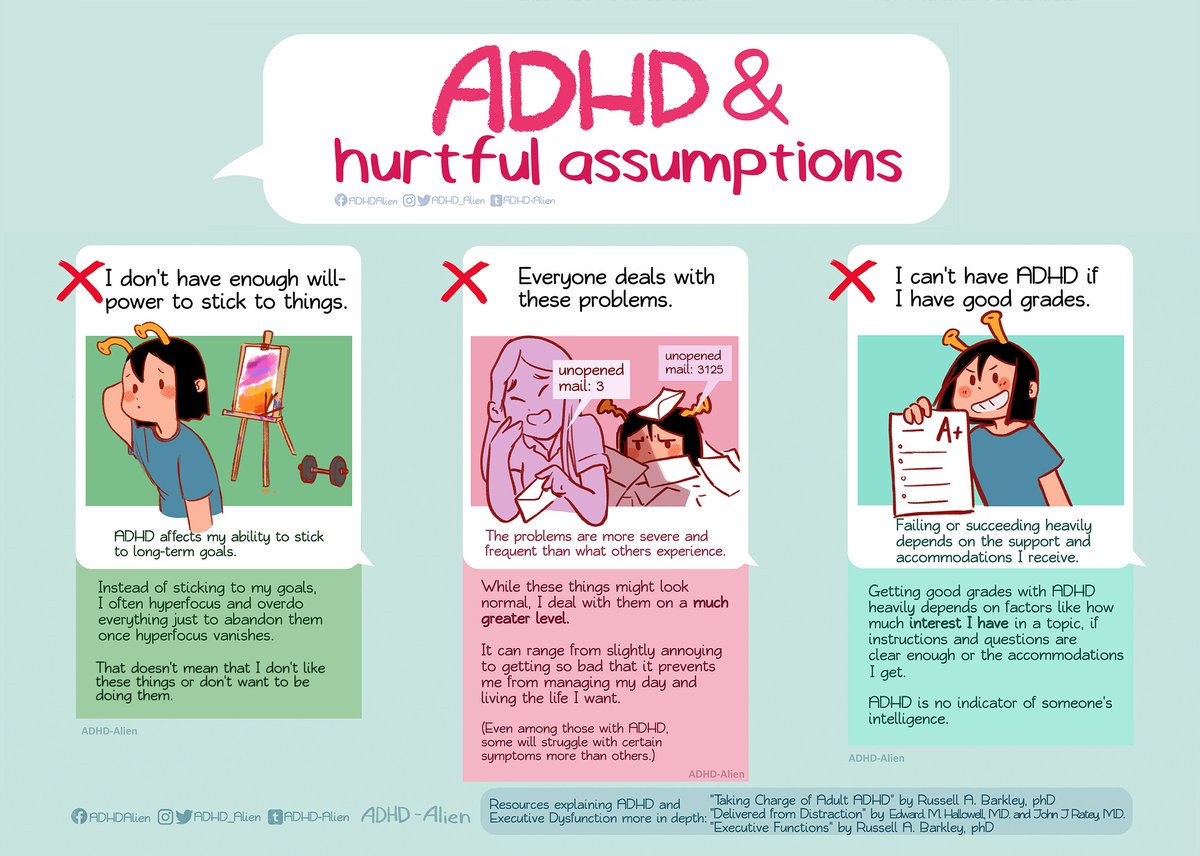

But in a classroom, or at work, these traits can look like laziness or an inability to learn. They are not. As a child, I was often described by teachers as “stubborn and moody;” a “daydreamer”. As an adult that morphed into another common theme—not performing up to my potential.

I wish someone had helped me to understand what I am about to explain to you now.

ADHD Has an Upside: Our Quirks Are Also Strengths

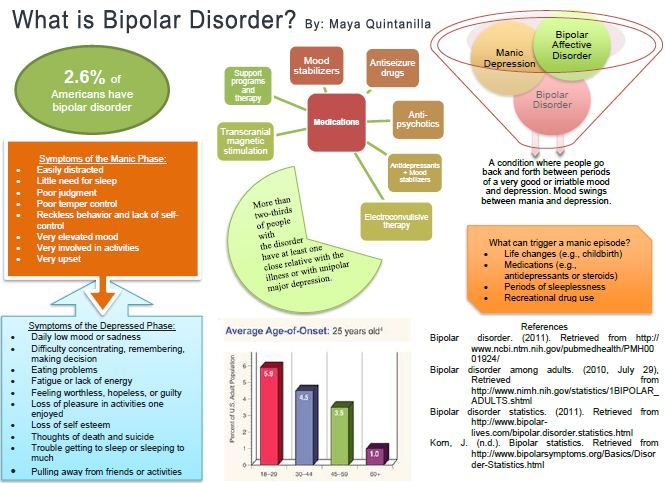

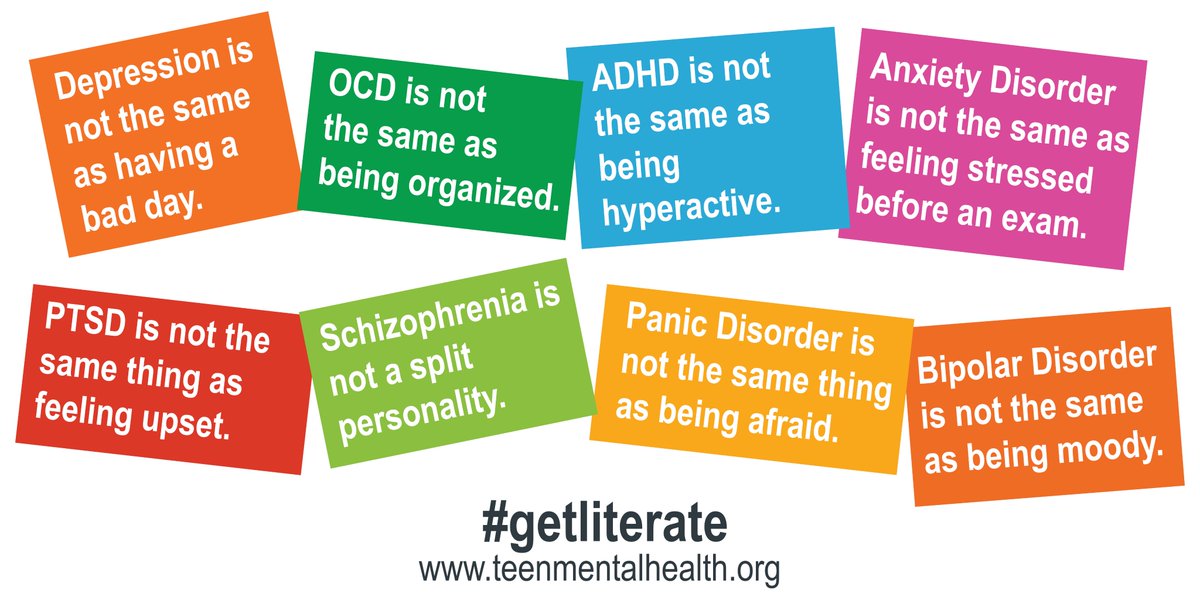

ADHD is not a one-size-fits-all explanation for behavior and difficulties. The disorder puts you at an increased risk of anxiety, depression, eating disorders, substance use, and suicide. Factors like stress, boredom, disinterest, lack of sleep, being hungry, feeling overwhelmed by noise, or lack of downtime impact how well we adapt to certain work and social environments.

What I know now is that people of all ages can learn and succeed not in spite of, but often because of, their creativity, empathy, imagination, sense of humor, and experience managing stress.

What people don’t hear enough: ADHD and all its unruly bedfellows can be managed and even make some people better at coping in extreme situations, such as a global pandemic, lockdowns, or layoffs. Effective strategies include accommodations at work (like wearing noise-canceling headphones to block out distracting noise) or school (like receiving extra time to complete tests). Tutoring, therapy, coaching, peer support, and medication (usually some combination of all of those) along with a hearty dose of patience, all work well, too.

ADHD is not a trend or a fad. About 1 in 5 Americans live with learning/attention disabilities. That includes children, adolescents, and adults.¹ Those numbers are likely even higher since many are undiagnosed due to factors like stigma and lack of access to care and treatment.

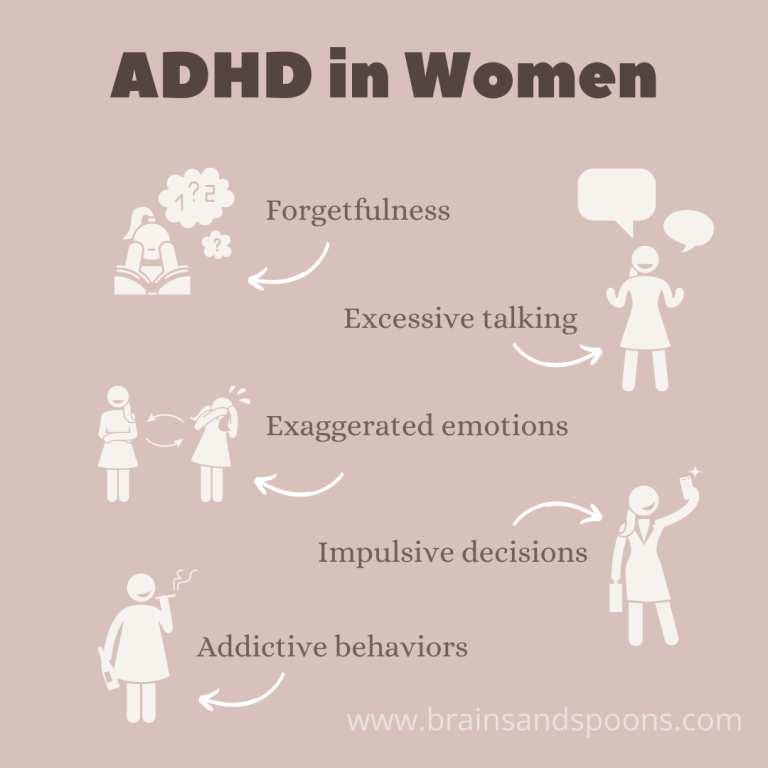

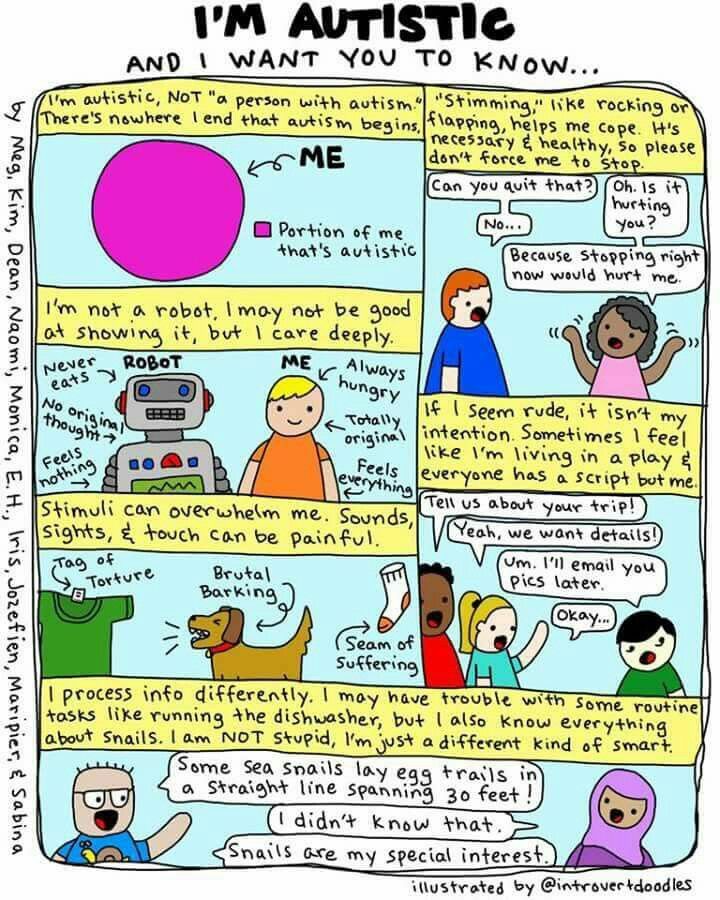

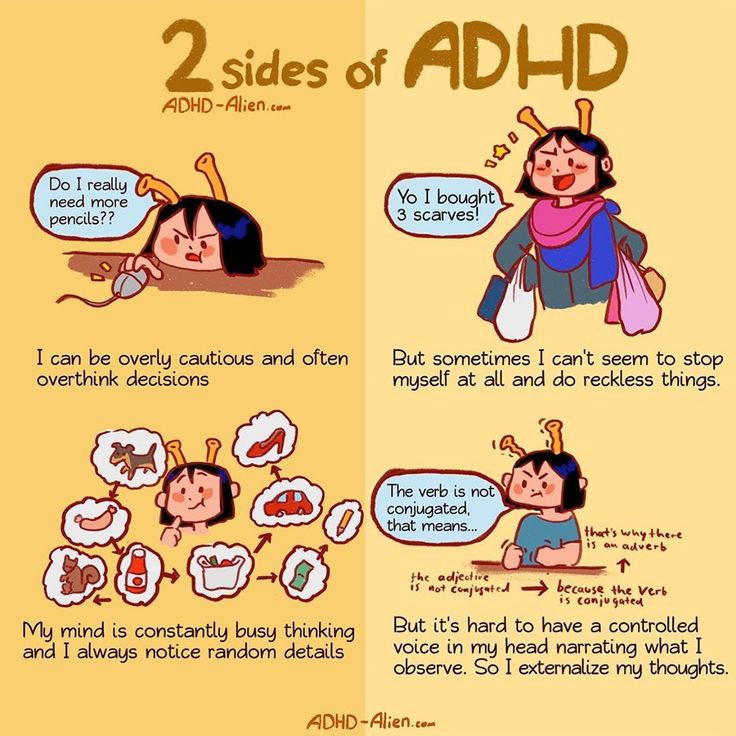

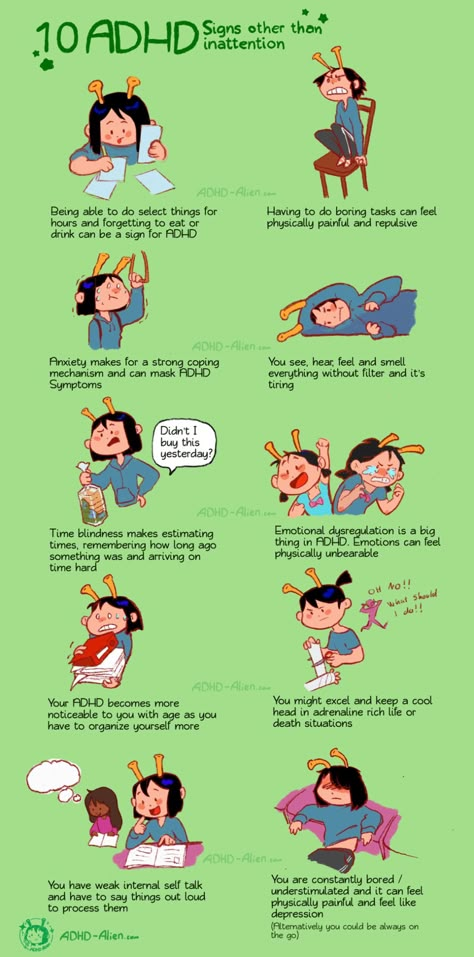

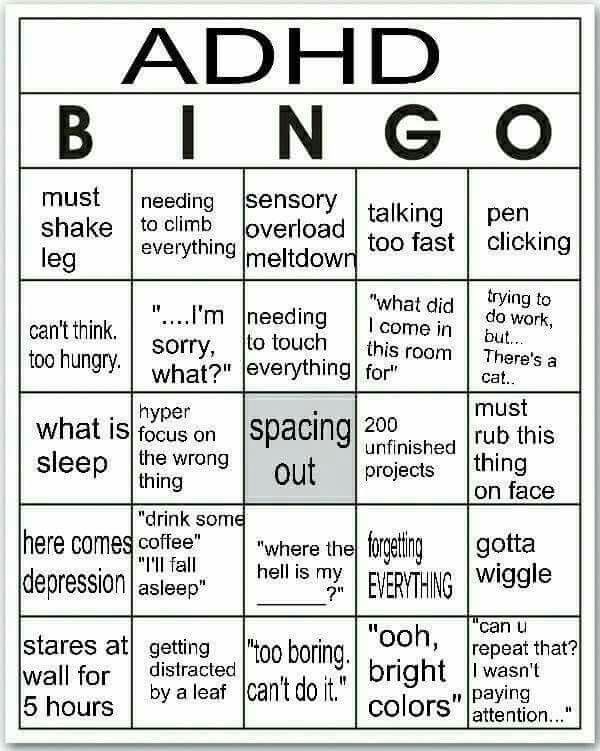

People with ADHD will have at least two or three of the following challenges: difficulty staying on task, paying attention, daydreaming or tuning out, organizational issues, and hyper-focus, which causes us to lose track of time. ADHD-ers are often highly sensitive and empathic. Over the years, I’ve been called quirky and weird—and while that’s true that's not a negative for me. I'll keep my quirks, thank you very much.

Navigating the Choppy Waters of ADHD

There is no standard diagnostic test for ADHD. Most clinicians use neuropsychological tests to see where on a spectrum of skills and behaviors a person fits in. But it can be more art than science, which makes for a lot of grey areas.

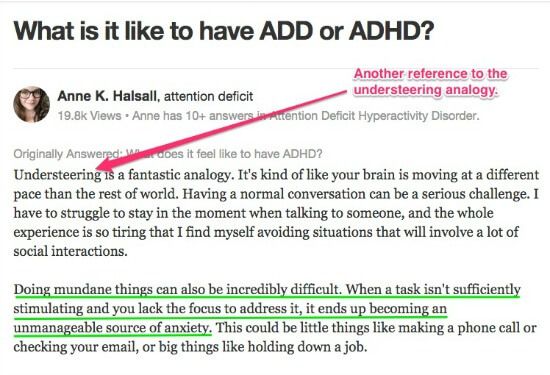

Edward Hallowell, MD, psychologist, and author of the best-selling ADHD guide Driven to Distraction, also has ADHD. He famously describes it as having the brain of a Ferrari with the brakes of a bicycle. (I would add that there are a lot of cool things about Ferrari’s, of course, but if that’s how you roll, you’re going to need better brakes. )

)

Even today, the simplest things—finding my way back to a lecture hall from the bathroom or getting nauseated by the noise of a colleague chewing loudly at lunch—agitate me. But I find workarounds (leaving a trail of rubber bands on the floor for navigation purposes or humming to drown out the chewing, for instance) and work hard to compensate for any shortcomings.

To help neurotypicals (that means you) understand us, I’ve created a composite of an ADHD adult. My hope is that in reading this you will gain respect for these differences, see value in our quirks and talents, and be more sensitive to how we think, feel, work, and experience life.

Adult ADHD Show and Tell

A good place to start is by watching Jessica McCabe TedX talk, Failing at Normal which is both humorous and educational. (Jessica is also the host of a popular YouTube channel, How to ADHD.) Then, read on for an insider look at the ADHD experience, with the help of a few online tools. If it explains a lot—or sounds like someone you love—seek a medical diagnosis. Getting the care and treatment you need to thrive with ADHD requires it.

Getting the care and treatment you need to thrive with ADHD requires it.

#1. Adult ADHD Symptom: Staying on Task

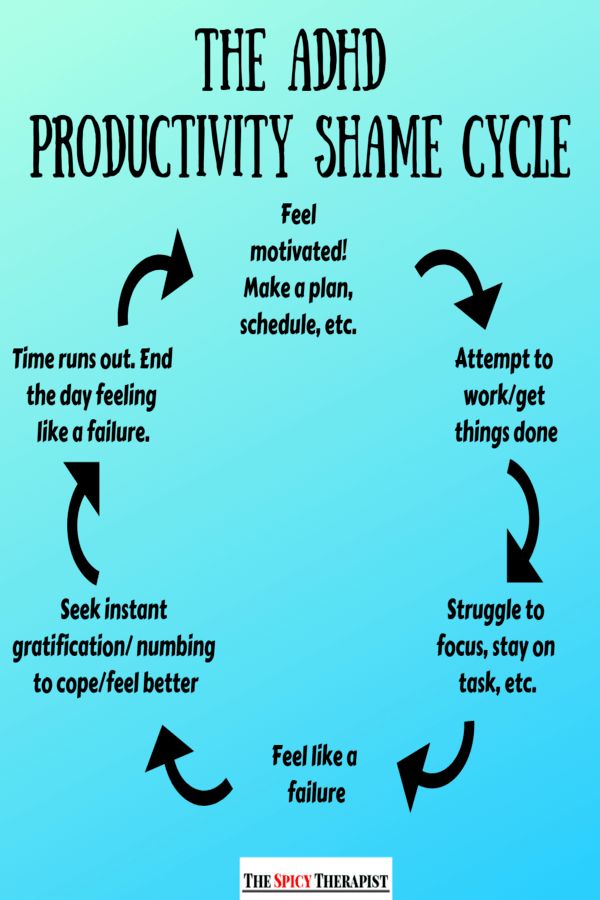

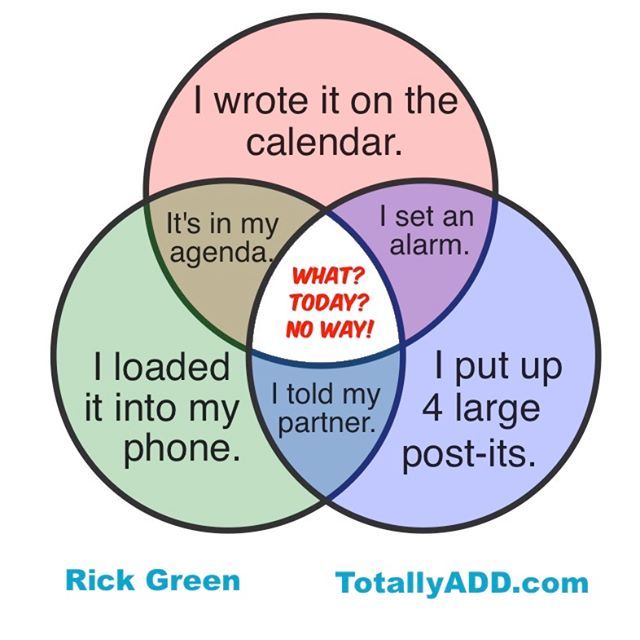

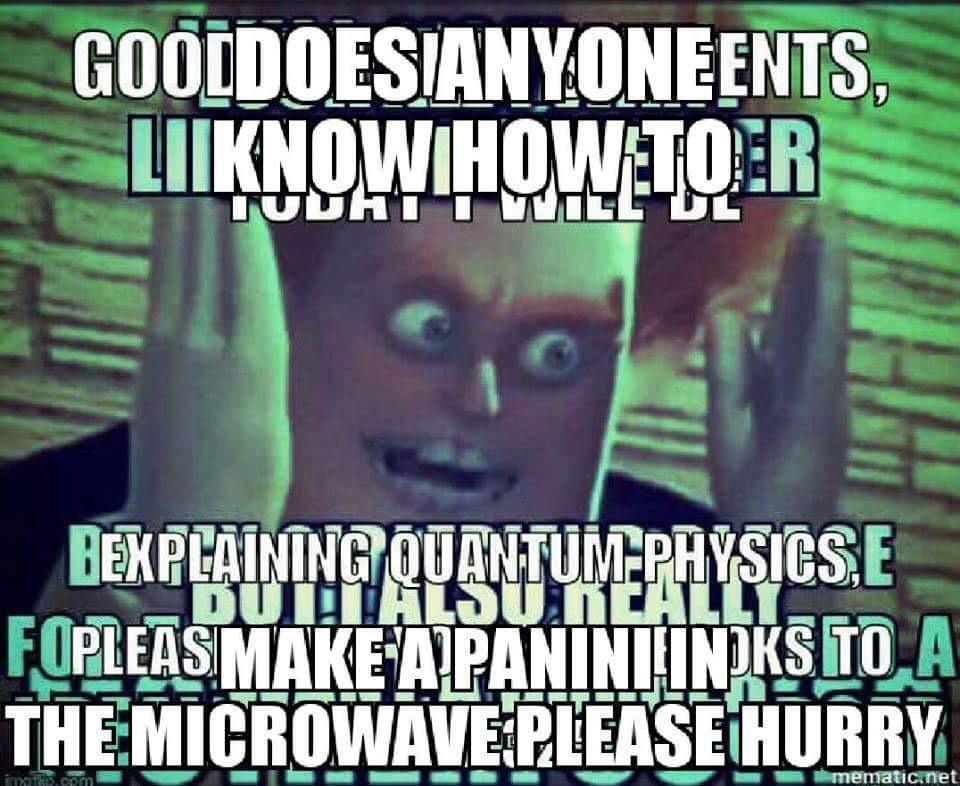

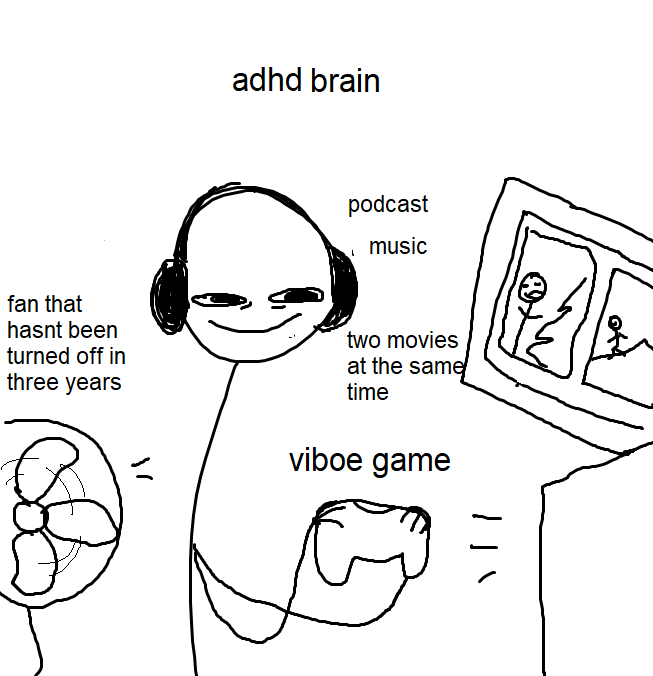

Concentrating on one task until it is finished is an issue that we all have at times because our minds are naturally disorderly places. The ADHD brain, however, hatches new plans and ideas constantly and can easily skip and jump from one idea to the next, forgetting to loop back to the original task, as average people might. Being online can be especially challenging for ADHD-ers (hello information rabbit hole). I set timers or limit myself to allowing only a fixed number of tabs open on my computer (eight is fine; 10 is too many). There are other tricks, old-fashioned tools like paper planners and calendars, and apps, like RescueTime and Freedom, that are designed to keep us productive.

To be clear, adults don’t need babysitters—we need prompters, tools, and allies, and the confidence to ask for them. With proper support, ADHD-ers are big thinkers and do extraordinary work. We just need a little help getting through tasks we may find boring.

We just need a little help getting through tasks we may find boring.

What it feels like: On a busy day, it’s not unusual for me to overestimate how much I can get done. I sometimes start up to five tasks during the day—writing thank you notes at breakfast, chopping vegetables for soup at lunch, researching a new smartphone, and creating a spreadsheet of expenses in the afternoon. They are all works in progress, which is fine until a deadline pops up (the mailman arrives for those letters or the soup is still just a pile of vegetables). I give myself two days to complete tasks, one day to start and one day to finish, so I am not constantly berating myself for not finishing them.

What you can do: Doing tasks I don’t enjoy for long periods of time trips my brain’s “off” switch, signaling it’s time for a short break, some exercise, or food.

#2. Adult ADHD Symptom: Working Memory Challenges

My understanding of big concepts, patterns, and ideas is huge and enviable. My ability to remember names and dates or end a sentence when I am distracted is poor. I’ve been called out for seemingly careless spelling mistakes and not paying attention. It’s not because I don’t give a hoot, it’s that my brain lacks a strong working memory meaning it lacks the ability to retain and remember short-term.²

My ability to remember names and dates or end a sentence when I am distracted is poor. I’ve been called out for seemingly careless spelling mistakes and not paying attention. It’s not because I don’t give a hoot, it’s that my brain lacks a strong working memory meaning it lacks the ability to retain and remember short-term.²

Spoken information or detail on a screen—rather than on a physical piece of paper—are the most difficult to recall. Heap on a measure of anxiety or depression (which usually exists on some level in people with ADHD) and it becomes even more difficult to summon facts in working memory.

In ADHD adults like me who also struggle due to dyslexia and dyscalculia this can manifest as skipping words or seeing $50,000 as $5000, somewhat problematic when filing your taxes, for example.

What it feels like: I used to be bewildered by my inability to pay attention (especially when I wanted to!) so I began tracking the problem. Noting when and where it occurred helped me understand that my brain melts down in noisy, crowded places. Big meeting halls, bustling airports, busy restaurants—you get the idea. It’s not unusual for me to forget my gate number at the airport and become frustrated when I can’t recall the Wi-Fi system password that was just flashed before me in a slide presentation moments ago.

Big meeting halls, bustling airports, busy restaurants—you get the idea. It’s not unusual for me to forget my gate number at the airport and become frustrated when I can’t recall the Wi-Fi system password that was just flashed before me in a slide presentation moments ago.

Grocery shopping when you have ADHD can also be a daunting task. Preparing a list, navigating the aisles, selecting the right brand, size, variety (hold the artificial sweetener, please!), and trying to stay on task all tax the working memory and can trigger sensory overload. This ADHD Simulator video, which I find brain-rattling (I don’t experience food shopping this intensely), you’ll see why a routine trip to the grocery store is anything but routine for people with ADHD.

What you can do:Try noise-canceling headphones if grocery shopping exhausts your brain, or consider having your food delivered.

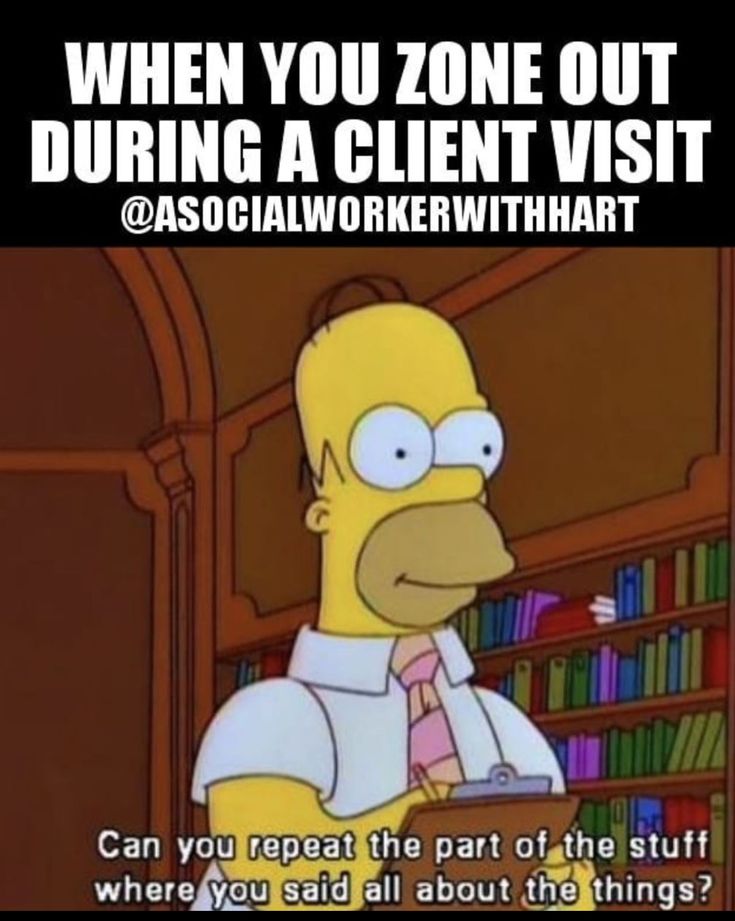

#3. Adult ADHD Symptom: The Blank Stare

In general, stress and anxiety (and anxiety about being stressed) tax my whole body. Loud noise, intense conversations, five Zoom meetings in a row, pop-up advertising, and other unexpected disruptions are exhausting. Here’s how that causes me to zone out.

Loud noise, intense conversations, five Zoom meetings in a row, pop-up advertising, and other unexpected disruptions are exhausting. Here’s how that causes me to zone out.

What it feels like: Right now, a jackhammer is outside my window busting through the street. Leaf blowers and loud motorcycles are equally unbearable. Tolerating noises like these zaps all the energy in my brain temporarily, literally causing me to stop talking mid-sentence. This deer-in-the-headlights look can also be a reaction to a swirling or distracting graphic or a series of pop-up advertisements on a page. (I use the ‘reader’ function on my computer to read copy without pop-ups).

What you can do: Give yourself a break by doing something you enjoy. My go-to's are listening to music, exercise, baking, or gardening.

#4. Adult ADHD Symptom: Daydreaming

Not to be confused with zoning out (see above), daydreaming is different. ADHDers are curious by nature. It's easy for us to get lost exploring passions and seeking answers to our many questions. Our daydreaming might look like a deep dive into Instagram or re-living an awesome vacation.

Our daydreaming might look like a deep dive into Instagram or re-living an awesome vacation.

If I’m not interested in what a person is yammering on about—even if I know it’s an important presentation and I should be paying close attention—my mind starts to wander.

What it feels like: This elementary school classroom simulation offers a look at what struggling to pay attention is like.

What you can do: To keep me focused I've trained myself to find at least one thing about the person or presentation that’s interesting. (During a televised debate, for example, I’ll play Candidate Bingo or keep track of how many times a person says a long word, like ‘democratization’. Sometimes that’s all it takes to keep my head in the game.)

#5. Adult ADHD Symptom: Constantly Losing Things

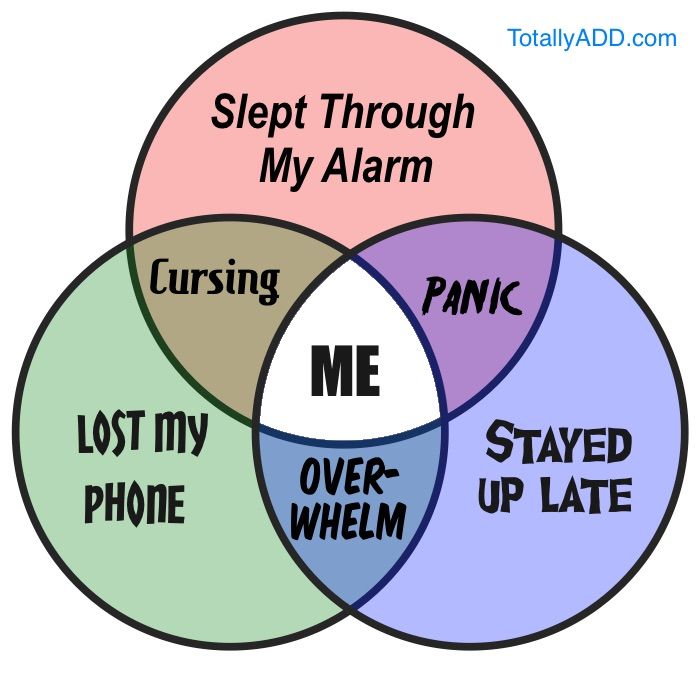

If you’ve ever seen someone wait patiently in line for the Starbucks and then drive off with it on the top of their car, you know these kinds of gaffs can be humiliating—and costly. Another favorite is calling a friend to tell her I’m running late because I can’t find my phone, which I am talking to her on. It’s maddening.

Another favorite is calling a friend to tell her I’m running late because I can’t find my phone, which I am talking to her on. It’s maddening.

What if feels like: Living with ADHD means constantly fighting distraction, overstimulation, anxiety, and being disorganized. All these challenges (mostly related to working memory deficits) strain our ability to retain information.

If my forgetfulness is causing a serious issue—losing my keys makes me constantly miss important appointments or not remembering where I put a daily medication compromises my health, I practice a routine or ritual to trigger my memory.

What you can do: To help me remember my keys and wallet I place them on a silver tray near the door. (Since the pandemic I've added a mask to the tray!) Before I leave I do a body check—umbrella, tote bag, disinfectant, phone, keys, wallet, snack, and….oh, yes, the mask. Do that enough times and it can take as little as 10 seconds to recall what you’re missing.

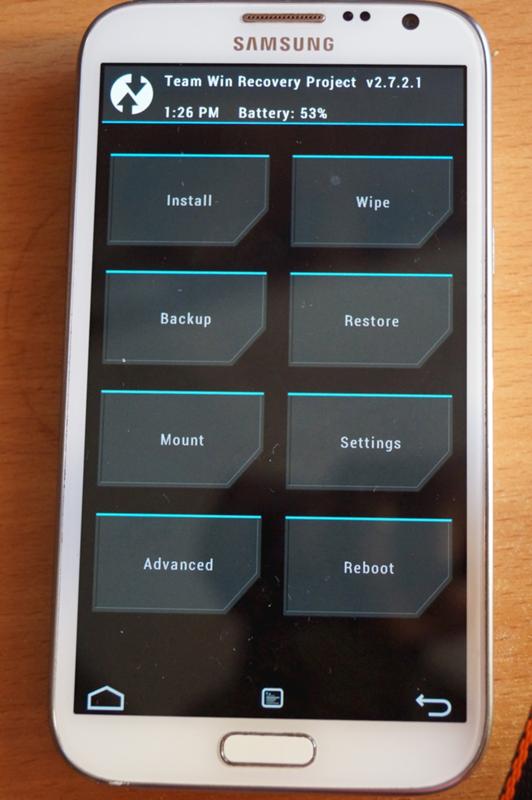

#6. Adult ADHD Symptom: Not Following Directions

Following directions requires active listening, attention to detail, and staying on task. My ADHD brain also likes to find creative solutions to problems that can be misunderstood as willfulness. Doing things my own way has led to a lot of harsh and unwanted criticism even bullying at work.

What it feels like: In some cases, following directions is not possible for me. My brain doesn’t process directions as quickly as others and I have zero sense of geography and time. I’m constantly begging the lady inside my GPS to ‘say that again’ or shushing my kids because I need to focus when looking for an exit.

Distractions, even the smallest ones, can hinder my ability to use step-by-step instructions, whether I am cooking, putting together a lamp, or behind the wheel of a moving vehicle. This ADHD Struggles Video explains it a bit more.

What you can do: Saying directions out loud sometimes help me. If it is a long set of instructions, I underline each part I’ve completed in pencil, so I know where I’ve stopped if I get distracted. Repeating directions someone else has given you and saying them again can help, as in, "Thanks, sir. It’s a right, left, sharp left." Then repeat for good measure.

Repeating directions someone else has given you and saying them again can help, as in, "Thanks, sir. It’s a right, left, sharp left." Then repeat for good measure.

So there you have it. That's what living with ADHD feels like. Now get out there and start using your ADHD energy, creativity, and unique problem-solving skills to set the world on fire.

- National Institute of Mental Health. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Available atL https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/attention-deficit-hyperactivity-disorder-adhd.shtml. Last Updated November 2017. Accessed October 6, 2020.

- Cowan N. Working Memory Underpins Cognitive Development, Learning, and Education. Educ Psychol Rev. 2014;26(2):197-223. doi:10.1007/s10648-013-9246-y Accessed October 6, 2020.

Notes: This article was originally published October 7, 2020 and most recently updated April 19, 2022.

Denise Brodey

Denise Brodey is a senior contributor at Forbes covering mental health and disability in the workplace. In 2020, she founded Rebel Talent, where diverse minds discover how to do their best work. Follow on Instagram @TalentRebel.

In 2020, she founded Rebel Talent, where diverse minds discover how to do their best work. Follow on Instagram @TalentRebel.

What Does ADHD Feel Like On a Really Bad Day?

Mood swing concept. Many emotions surround young female with Bipolar disorder. Woman suffers from hormonal with a change in mood. Mental health vector illustration1 of 10

When My Thoughts Don’t Translate

I may look just like everyone else, but I know I’m different. I feel the most disconnected and dissimilar when I try — and fail — to communicate my unique perspective. No one understands what I’m talking about; it’s almost as if I’m speaking a foreign language. At these times, I either feel as if I am the only sane and observant person present, or I feel isolated and misunderstood. Or both, especially when I see their eyes rolling as I speak. They don’t say anything, but I know what they’re thinking.

2 of 10

When I’m Alone, But Surrounded

I love people. Conversation is like an indulgent dessert — most days. But on bad days, my racing brain drowns out all sound and paralyzes my brain and my tongue. When I sit among friends engaged in conversation on those bad days, my body is there, but my mind is elsewhere. You think I hear what you're saying, but all I hear is mumbling. I try to focus on your words, but my darting mind sabotages me. When my emotions are this strong, I have no words. It’s hard to speak; it’s even harder to listen.

Conversation is like an indulgent dessert — most days. But on bad days, my racing brain drowns out all sound and paralyzes my brain and my tongue. When I sit among friends engaged in conversation on those bad days, my body is there, but my mind is elsewhere. You think I hear what you're saying, but all I hear is mumbling. I try to focus on your words, but my darting mind sabotages me. When my emotions are this strong, I have no words. It’s hard to speak; it’s even harder to listen.

3 of 10

When Worry Takes Over

The imagination is a wonderful trait when used for good. But my ADHD imagination has a habit of running wild, meandering down harmful paths filled with negative thoughts that stick like Velcro. Catastrophic images appear. Every situation is accompanied by a what-if, worst-case scenario; and that’s when the spiraling cycle begins. How could the same imaginative power that allows some people with ADHD to compose symphonies, paint masterpieces, and develop computer programs, be so crippling? I beat myself up over this some more.

But my ADHD imagination has a habit of running wild, meandering down harmful paths filled with negative thoughts that stick like Velcro. Catastrophic images appear. Every situation is accompanied by a what-if, worst-case scenario; and that’s when the spiraling cycle begins. How could the same imaginative power that allows some people with ADHD to compose symphonies, paint masterpieces, and develop computer programs, be so crippling? I beat myself up over this some more.

[Get This Free Download: How to Rein In Intense ADHD Emotions]

A woman with ADHD sleeps on a sofa with a book over her face.4 of 10

When I Can’t Physically Relax

I dream of sinking into a comfy couch and just relaxing my whole body — feeling totally comfortable and content. It’s such a simple pleasure that I’ve never known. I’m always adjusting my legs, arms, back… one minute I’m fine, but a moment later, the chair is stabbing me in the back or the pillow is too soft. I’m restless. I squirm constantly. I know people are looking at me, but how can I begin to explain the discomfort of having senses in perpetual overdrive? It’s easier to keep my discomfort to myself. But this can make it hard to enjoy being with others. My discomfort takes up space in my mind, and I’m sure I’m not fun to be with when I’m constantly complaining. It’s easier to stay home and hang out in a baggy shirt and drawstring pants.

I’m restless. I squirm constantly. I know people are looking at me, but how can I begin to explain the discomfort of having senses in perpetual overdrive? It’s easier to keep my discomfort to myself. But this can make it hard to enjoy being with others. My discomfort takes up space in my mind, and I’m sure I’m not fun to be with when I’m constantly complaining. It’s easier to stay home and hang out in a baggy shirt and drawstring pants.

5 of 10

When My Senses Overload

On a recent trip to a vineyard, my friends and I were driving down a very narrow dirt road in a beat-up old rented van that wouldn’t go in reverse. When we became wedged between barbed wire and bushes scraping the side of the car, I panicked. We weren’t in danger, but I began screaming out loud, “Get me out of here! Help!” Everyone else was fine. One person was laughing. Another one was quiet. Not me. I was screaming, despite the fact that I was safe and with friends. They still love me. But boy, did I feel embarrassed. Some days it would be nice to react normally to small setbacks and sensory challenges.

When we became wedged between barbed wire and bushes scraping the side of the car, I panicked. We weren’t in danger, but I began screaming out loud, “Get me out of here! Help!” Everyone else was fine. One person was laughing. Another one was quiet. Not me. I was screaming, despite the fact that I was safe and with friends. They still love me. But boy, did I feel embarrassed. Some days it would be nice to react normally to small setbacks and sensory challenges.

6 of 10

When Focus Just Won’t Come

ADHD is frustrating. People don’t understand why I can’t focus when I need to. "Just do it," they say. Really?!? I am. But as I focus, new ideas emerge like shooting stars, bursting through my mind. I can’t ever find a quiet space to focus because my mind is so noisy and busy all the time. Even when its bandwidth is full and I feel overloaded, my brain is capable of receiving more data. This is when my focus wanders, and I feel isolated, alone, and misunderstood.

This is when my focus wanders, and I feel isolated, alone, and misunderstood.

7 of 10

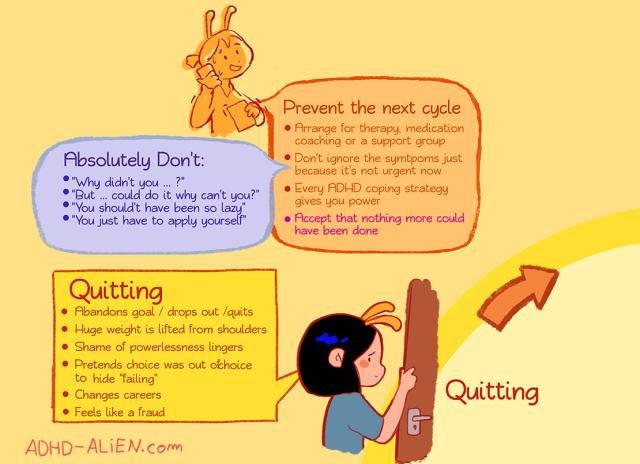

When I Feel Like a Fraud

I doubt myself. I may appear tough on the outside, but inside my mind I’m criticizing every action, every word, and every decision I make. Behind the façade, there is a woman who feels misunderstood. I act as if I’ve got it together, and sometimes I do. But there are many times when I feel like a fraud and my mind begins telling me, “Who am I kidding? The truth will come out. People will see how incapable I am.”

[Your Free Expert Guide: Unraveling the Mysteries of Your ADHD Brain]

Close-up of ADHD person wearing boxing gloves over white background8 of 10

When I’m Fighting My Own Mind

ADHD is a largely invisible condition (except for those times I run around the house frantically searching for my keys, of course). Everyone has an invisible self, but most people seem to behave according to their thoughts. People with ADHD, on the other hand, have so many competing thoughts vying loudly for attention and action in our brains that it becomes hard to move. Our speeding minds freeze our bodies because we don’t know where or how to begin. At the times when bombarding thoughts physically disable me, I have no choice but to stop and reset. Observers might assume I’m being selfish or slow or lazy, but I challenge them to spend 10 minutes inside my head without a time-out, too.

Everyone has an invisible self, but most people seem to behave according to their thoughts. People with ADHD, on the other hand, have so many competing thoughts vying loudly for attention and action in our brains that it becomes hard to move. Our speeding minds freeze our bodies because we don’t know where or how to begin. At the times when bombarding thoughts physically disable me, I have no choice but to stop and reset. Observers might assume I’m being selfish or slow or lazy, but I challenge them to spend 10 minutes inside my head without a time-out, too.

9 of 10

When My Inner Struggle Feels Endless

Oh, if only others knew the battle I fight all day. “I want” is in constant combat with “I should” in my brain. My adult self knows what I should be doing, but the child inside me says, no. I watch other adults performing responsible tasks like paying bills, making appointments, doing laundry, and managing mail. But for me, those “simple” tasks can easily cause me to fall into the black hole of shame and guilt. At those times, paying a bill is not paying a bill; it is coming face-to-face with a lifetime of financial disorganization that can’t be fixed in an afternoon.

At those times, paying a bill is not paying a bill; it is coming face-to-face with a lifetime of financial disorganization that can’t be fixed in an afternoon.

10 of 10

When I Forget My Survival Systems

In spite of the intense internal struggle of ADHD, I do mostly maintain a healthy, responsible lifestyle thanks to prioritized self-care. Even though the simple tasks continue to challenge me, my systems help me function and keep me on track. ADHD is never easy. But with self-awareness — knowing my strengths and knowing how to manage my weaknesses — ADHD is easier to live with. The trick is trusting in those systems and that self-awareness when you need them most.

[Read This Next: ADHD-Friendly Tools for Handling Emotional Stress]

ADHD and neuroscience | Encyclopedia of early childhood development

1 Samuel Cortese, MD, PhD, 2 Francisco Xavier Castellanos, MD

1. 2 NYU Langone Medical Center for Children, USA 2 Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, USA nine0008 (English). Translation: November 2015

2 NYU Langone Medical Center for Children, USA 2 Nathan Kline Institute for Psychiatric Research, USA nine0008 (English). Translation: November 2015

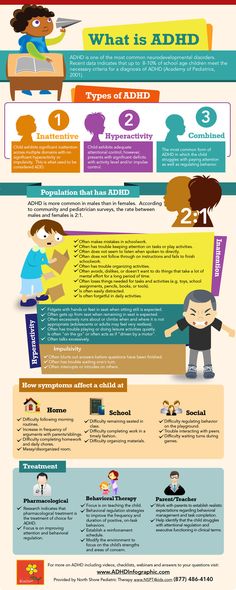

Introduction

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a common neuropsychiatric disorder among children, which is estimated to affect 3 to 7% of school-age children worldwide. 1 Because of the symptoms of ADHD and the often associated psychiatric comorbidities, individuals with ADHD are at risk of family conflict, adverse peer interactions, and school/work failures. Thus, ADHD places a heavy burden on society. nine0004 2

Issues

- ADHD is currently diagnosed according to a set of behavioral criteria, 1 , which contributes to the debate about the “subjective” nature of the diagnosis.

- Individuals with ADHD may have different clinical presentations, leading to confusion both in the clinical setting and in research.

- Current classification does not explain developmental variation in symptoms. nine0032 There is currently no long-term treatment available. 3

Subject

An understanding of the growing field of pediatric neuroscience is essential to move from a classification based on clinical description of symptoms to a model based on the causes of a disorder. Such mechanistic models are believed to lead to an objective characterization of patients with more precisely defined ADHD subtypes and to the possibility of developing effective pathophysiology-based treatments. nine0016

Scientific context

The most productive contribution to the understanding of ADHD can be made through multidisciplinary applied research, including physiology, psychology, neurology, psychiatry, bioinformatics, neurogenetics, cell and molecular biology, and systems neuroscience.

Key questions

Among the questions being studied by the methods of neuroscience, the following are central:

- Does the brain of people with ADHD differ in morphological features from the brain of people without ADHD from the control group?

- Do the brains of people with ADHD function differently?

- Does the neurochemistry of the brain differ when a person has ADHD?

- What are the causes of the alleged dysfunctions?

- What are the developmental trajectories of brain anomalies?

Recent research results

Does the brain of people with ADHD differ in morphological features? nine0081

Early studies using structural MRI (magnetic resonance imaging) showed some significant morphological differences in individuals with ADHD from the control group, although the results obtained are not always consistent with each other. 4 A meta-analysis of 5 has shown that the areas of the brain that have the largest areas or decrease in volume in the presence of ADHD compared with the control group include some specific brain regions involved in the organization and control of movement, as well as and total volume and right hemisphere volume. However, many of these studies have been based on a single area, focusing too much on a relatively small number of easily measurable brain structures. More recent meta-analysis 6 voxel-based morphometric studies (which are spatially objective) found that only reduction in volume of the right putamen basalis was significant across all studies, although this conclusion remains tentative given the limited number (seven) of available studies. Recently, such previously unnoticed aspects as the thickness, curvature, depth of the brain convolutions and the shape of the brain structures are also taken into account. Atypical shape and decreased surface area have been reported, as well as anomalies in the shape of structures almost unexplored in early studies, such as the limbic system and thalamus. nine0004 7

However, many of these studies have been based on a single area, focusing too much on a relatively small number of easily measurable brain structures. More recent meta-analysis 6 voxel-based morphometric studies (which are spatially objective) found that only reduction in volume of the right putamen basalis was significant across all studies, although this conclusion remains tentative given the limited number (seven) of available studies. Recently, such previously unnoticed aspects as the thickness, curvature, depth of the brain convolutions and the shape of the brain structures are also taken into account. Atypical shape and decreased surface area have been reported, as well as anomalies in the shape of structures almost unexplored in early studies, such as the limbic system and thalamus. nine0004 7

Finally, recent studies of diffusion tensor imaging, which makes it possible to quantitatively study the white matter of the brain, indicate an altered structural connection in the channels connecting the right prefrontal cortex with the basal ganglia and the cingulate gyrus with the entorial cortex. 8

8

Do the brains of people with ADHD function differently?

The literature on ADHD functional imaging is too extensive to present systematically here. We report the results of the main systematic reviews/meta-analyses available. nine0016

Mean data 9 functional MRI studies show frontal hypofunction affecting different areas of the cerebral cortex (anterior cingulate, dorsolateral, prefrontal, inferior prefrontal and orbitofrontal), as well as dependent areas (such as the lobes of the basal ganglia, thalamus and parietal cortex). Interestingly, these data reflect the overall anatomy revealed by structural MRI.

A quantitative EEG meta-analysis showed an increase in theta waves and a decrease in beta waves in individuals with ADHD compared with controls. nine0004 10 The most reliable result of studies of evoked potentials is a decrease in the posterior P3 (posterior P3) when performing an oddball task. 11 Together, the structural and functional findings point to widespread abnormalities involving many brain structures.

Indeed, at the moment, researchers in this field are focusing on the study of dysfunction of distributed neural networks in the brain. A relatively new approach that assesses functional connectivity at rest and in the problem-solving state seems to be very promising in understanding the essence of the complex anomalies of the networks that supposedly underlie ADHD. nine0004 12 Preliminary evidence supports the so-called default-mode interference hypothesis of ADHD, according to which inefficient modulation of the oscillations of the default mode networks of the brain affects the optimal functioning of the neural circuit, underlying the execution of the current task. 13

Does the neurochemistry of the brain differ in the presence of ADHD?

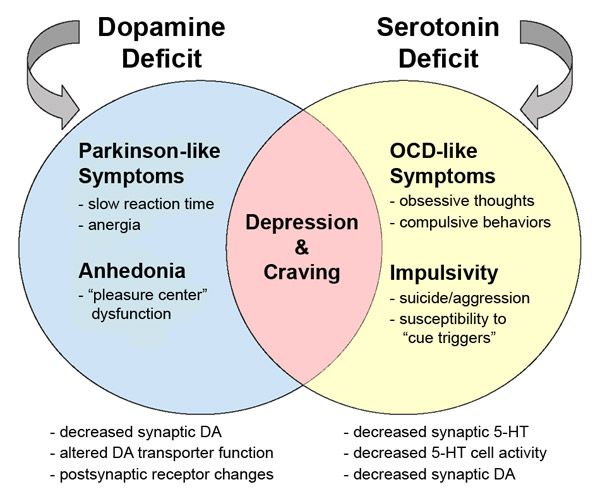

Using combined data from genetics, neuroimaging, neuropsychopharmacology, and animal experiments, it is suggested that several neurotransmitter systems (such as the dopaminergic, noradrenergic, serotonergic, and possibly nicotinic cholinergic systems) are involved in the pathophysiology of ADHD. nine0004 14

nine0004 14

Altered levels of some compounds (choline derivatives, N-acetyl aspartate and glutamate/glutamine [dopamine regulator]) relative to creatinine have been reported in a number of preliminary studies. 15

What are the causes of the alleged dysfunctions?

ADHD is highly heritable (heritability ~0.76). 16 However, the data of genetic studies at the moment are disappointing. A meta-analysis of whole genome-scanning studies found significant genome-wide linkage only for a region on chromosome 16, suggesting that there are hardly many genes that make a relatively large individual contribution. nine0004 17 A recent meta-analysis of studies using whole genome scanning failed to find any significant association. 18 A small but significant contribution from several individual candidate genes, involving mostly the dopaminergic system (DRD4, DRD5, DAT1, HTR1B and SNAP25) has been confirmed in meta-analyses, but for many other candidate genes the data are inconsistent. 19 The recently established association, which is significant at the genome-wide level, and the linkage found in positional cloning with confirmation in independent replication studies, support a possible role for the newly discovered latrophilin 3 (LPHN3) gene. nine0004 20-21

19 The recently established association, which is significant at the genome-wide level, and the linkage found in positional cloning with confirmation in independent replication studies, support a possible role for the newly discovered latrophilin 3 (LPHN3) gene. nine0004 20-21

Among a number of putative environmental risk factors, a recent systematic review 22 confirmed the most likely role of early birth and smoking during pregnancy.

What are the developmental trajectories of brain anomalies?

A recent longitudinal study reported an approximately three-year delay in brain development in the presence of ADHD. Long-term ADHD was characterized by a deviant developmental trajectory, while remission was tended to be associated with normalization of anatomical disorders. nine0004 7

Unexplored areas

- At what developmental stages do neural network disorders first appear and are easily detected?

- Is it possible to identify genetic factors with small individual contributions if we collect large enough samples? What would be the appropriate phenotypes for such large scale approaches?

- What is the role of genetic factors other than single nucleotide polymorphisms? A recent study found an increase in the frequency of copy-number variations (CNV) in ADHD.

nine0004 23 Structural variations in DNA such as insertions, deletions and duplications appear frequently in the population, but their specific clinical significance is unclear.

nine0004 23 Structural variations in DNA such as insertions, deletions and duplications appear frequently in the population, but their specific clinical significance is unclear. - How can one best understand the interactions of genes and environmental (both biological and psychosocial) variables?

- How do different etiological factors lead to neuronal abnormalities?

- What are the potential benefits of a pathophysiology-based intervention? For example, biofeedback 24 and, to a lesser extent, transcranial magnetic stimulation 25 are promising approaches, although scientific evidence is still required to confirm this.

Findings

Research in neuroscience has shown unequivocally that the brains of children with ADHD differ from those of children in the control group. More recently, the neurobiological study of ADHD has shifted from a model based on differences in brain regions to a pattern of changing connections between multiple brain regions. At the moment, we are still mostly collecting information about the individual elements of these networks. In the near future, we need to understand the essence of how these parts fit together. nine0016

At the moment, we are still mostly collecting information about the individual elements of these networks. In the near future, we need to understand the essence of how these parts fit together. nine0016

We are also discovering, although technical and methodological difficulties still remain, the genetic basis of these dysfunctions and possible environmental factors that interact in complex ways with the genetic basis.

Labor-intensive and costly longitudinal studies have begun to provide unique insights into the trajectories of brain anomalies and their relationship to ADHD symptoms. The clearer these elements become, the better this field of research can construct an etiopathophysiologically sound intervention for ADHD with the possibility of long-term efficacy. nine0016

Recommendations for parents, services, and administrative policies

Although neuroscience has contributed to our understanding of the etiopathophysiology of ADHD, we have not yet identified susceptible and specific neurobiological markers. Therefore, parents need to be aware that the diagnosis of ADHD is still based on behavioral criteria.

Therefore, parents need to be aware that the diagnosis of ADHD is still based on behavioral criteria.

However, the explosion of neuroscience-based ADHD research, coupled with rapid technological advances, will make the next years exciting and fruitful in understanding ADHD. It is possible that future neurobiological testing for ADHD will not replace clinical evaluation. However, in the near future, services will need to introduce methods from neuroscience into medical practice. Large networks of researchers in the field of diagnostic imaging and genetics will be needed to combat future challenges in research. Significant funding will inevitably be needed to support this work, but the potential results and their public health implications are expected to justify the economic costs. nine0016

Literature

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSMIV-TR) . 4th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing inc; 2000.

- Biederman J, Faraone SV. Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet 2005;366:237-248.

- Vitiello B. Long-term effects of stimulant medications on the brain: possible relevance to the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. nine0080 Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 2001;11:25-34.

- Castellanos FX. Toward a pathophysiology of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Pediatrics 1997;36:381-393.

- Valera EM, Faraone SV, Murray KE, Seidman LJ. Meta-analysis of structural imaging findings in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biological Psychiatry 2007;61:1361-1369.

- Ellison-Wright I, Ellison-Wright Z, Bullmore E. Structural brain change in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder identified by meta-analysis. nine0080 BMC Psychiatry 2008;8:51.

- Shaw P, Rabin C. New insights into attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder using structural neuroimaging.

Current Psychiatry Reports 2009;11:393-398.

Current Psychiatry Reports 2009;11:393-398. - Konrad K, Eickhoff SB. Is the ADHD brain wired differently? A review on structural and functional connectivity in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Human Brain Mapping 2010;31:904-916.

- Dickstein SG, Bannon K, Castellanos FX, Milham MP. The neural correlates of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: an ALE meta-analysis. nine0080 Journal of Child Psychology Psychiatry 2006;47:1051-1062.

- Snyder SM, Hall JR. A meta-analysis quantitative of EEG power associated with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology 2006;23:440-455.

- Barry RJ, Johnstone SJ, Clarke AR. A review of electrophysiology in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: II. event-related potentials. Clinical Neurophysiology 2003;114:184-198.

- Castellanos FX, Kelly C, Milham MP. The restless brain: attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, resting-state functional connectivity, and intrasubject variability.

nine0080 Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2009;54:665-672.

nine0080 Canadian Journal of Psychiatry 2009;54:665-672. - Sonuga-Barke EJ, Castellanos FX. Spontaneous attentional fluctuations in impaired states and pathological conditions: a neurobiological hypothesis. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews 2007;31:977-986.

- Russell VA. Reprint of “Neurobiology of animal models of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder”. Journal of Neuroscience Methods 2007;166(2):I-XIV.

- Perlov E, Philipsen A, Matthies S, Drieling T, Maier S, Bubl E, Hesslinger B, Buechert M, Henning J, Ebert D, Tebartz Van Elst L. Spectroscopic findings in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: review and meta- analysis. nine0080 World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 2009;10:355-365.

- Mick E. Molecular genetics of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatry Clinics of North America 2010;33:159-180.

- Zhou K, Dempfle A, Arcos-Burgos M, Bakker SC, Banaschewski T, Biederman J, Buitelaar J, Castellanos FX, Doyle A, Ebstein RP, Ekholm J, Forabosco P, Franke B, Freitag C, Friedel S, Gill M , Hebebrand J, Hinney A, Jacob C, Lesch KP, Loo SK, Lopera F, McCracken JT, McGough JJ, Meyer J, Mick E, Miranda A, Muenke M, Mulas F, Nelson SF, Nguyen TT, Oades RD, Ogdie MN, Palacio JD, Pineda D, Reif A, Renner TJ, Roeyers H, Romanos M, Rothenberger A, Schäfer H, Sergeant J, Sinke RJ, Smalley SL, Sonuga-Barke E, Steinhausen HC, van der Meulen E, Walitza S , Warnke A, Lewis CM, Faraone SV, Asherson P.

Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage scans of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. nine0080 American Journal of Medicine Genetics part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 2008;147B:1392-1398.

Meta-analysis of genome-wide linkage scans of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. nine0080 American Journal of Medicine Genetics part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 2008;147B:1392-1398. - Neale BM, Medland SE, Ripke S, Asherson P, Franke B, Lesch KP, Faraone SV, Nguyen TT, Schäfer H, Holmans P, Daly M, Steinhausen HC, Freitag C, Reif A, Renner TJ, Romanos M, Romanos J, Walitza S, Warnke A, Meyer J, Palmason H, Buitelaar J, Vasquez AA, Lambregts-Rommelse N, Gill M, Anney RJ, Langely K, O'Donovan M, Williams N, Owen M, Thapar A, Kent L , Sergeant J, Roeyers H, Mick E, Biederman J, Doyle A, Smalley S, Loo S, Hakonarson H, Elia J, Todorov A, Miranda A, Mulas F, Ebstein RP, Rothenberger A, Banaschewski T, Oades RD, Sonuga -Barke E, McGough J, Nisenbaum L, Middleton F, Hu X, Nelson S; Psychiatric GWAS Consortium: ADHD Subgroup. Meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. nine0080 Journal of the American Academy Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2010;49:884-897.

- Banaschewski T, Becker K, Scherag S, Franke B, Coghill D. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an overview. European Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 2010;19:237-257.

- Arcos-Burgos M, Jain M, Acosta MT, Shively S, Stanescu H, Wallis D, Domené S, Vélez JI, Karkera JD, Balog J, Berg K, Kleta R, Gahl WA, Roessler E, Long R, Lie J , Pineda D, Londoño AC, Palacio JD, Arbelaez A, Lopera F, Elia J, Hakonarson H, Johansson S, Knappskog PM, Haavik J, Ribases M, Cormand B, Bayes M, Casas M, Ramos-Quiroga JA, Hervas A , Maher BS, Faraone SV, Seitz C, Freitag CM, Palmason H, Meyer J, Romanos M, Walitza S, Hemminger U, Warnke A, Romanos J, Renner T, Jacob C, Lesch KP, Swanson J, Vortmeyer A, Bailey -Wilson JE, Castellanos FX, Muenke M. A common variant of the latrophilin 3 gene, LPHN3, confers susceptibility to ADHD and predicts effectiveness of stimulant medication. nine0080 Molecular Psychiatry 2010.

- Ribasés M,Ramos-Quiroga JA, Sánchez-Mora C, Bosch R, Richart C, Palomar G, Gastaminza X, Bielsa A, Arcos-Burgos A, Muenke M, Castellanos FX, Cormand B, Bayés M, Casas M.

Contribution of Latrophilin 3 (LPHN3) to the genetic susceptibility to ADHD in adulthood: a replication study. Genes Brain and Behavior . In press.

Contribution of Latrophilin 3 (LPHN3) to the genetic susceptibility to ADHD in adulthood: a replication study. Genes Brain and Behavior . In press. - Faraone S.V. The aetiology of ADHD: Current challenges and future prospects. Paper presented at the 1st International EUNETHYDIS meeting. May 26-28, 2010. Amsterdam, Netherlands. nine0035

- Williams N.M. Rare chromosomal deletions and duplications in attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder: a genome-wide analysis. Lancet . In press.

- Arns M, de RS, Strehl U, Breteler M, Coenen A. Efficacy of neurofeedback treaArns M, de RS, Strehl U, Breteler M, Coenen A. Efficacy of neurofeedback treatment in ADHD: the effects on inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity: a meta-analysis. Clinical & EEG Neuroscience Journal 2009;40:180-189. nine0035

- Bloch Y, Harel EV, Aviram S, Govezensky J, Ratzoni G, Levkovitz Y. Positive effects of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on attention in ADHD Subjects: a randomized controlled pilot study.

World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 2010;11:755-758.

World Journal of Biological Psychiatry 2010;11:755-758.

For citation:

Cortese S, Castellanos FC. ADHD and neuroscience. In: Tremblay RE, Buavan M, Peters RDeV, eds. Shakhar R, eds. themes. Encyclopedia of Early Childhood Development [online]. https://www.encyclopedia-deti.com/giperaktivnost-i-nevnimatelnost-sdvg/ot-ekspertov/sdvg-i-neyronauka. Published: December 2010 (English). Viewed on January 30, 2023

Text copied to clipboard ✓

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder - LabyrinthMed Medical Center Krasnoyarsk

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) is a disorder that manifests itself in preschool or early school age. It is difficult for such children to control their behavior and concentrate. It has been found that 3 to 5 percent of children suffer from ADHD. This means that in a class of 25-30 children, it is likely that at least one will have ADHD. nine0016

This means that in a class of 25-30 children, it is likely that at least one will have ADHD. nine0016

ADHD was first described by Dr. Heinrich Hoffmann in 1845. In 1902, Sir George F. Still published a series of lectures that described a group of impulsive children with significant problems due to genetic dysfunction rather than poor parenting - children who are today diagnosed with ADHD.

A child with ADHD faces difficult but not insurmountable challenges. For these children to reach their full potential, they need the help, guidance and understanding of parents, school teachers and the education system. nine0016

The medical center "LabyrinthMed" practices an integrated approach to the diagnosis and treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder . Comprehensive examination includes:

- reception of a psychotherapist;

- appointment with a neurologist;

- session of a medical psychologist, correctional session of a defectologist.

According to the results of the examination, a corrective program with specific recommendations is prescribed and treatment is prescribed.

You can make an appointment with a specialist or undergo a comprehensive examination on this problem by calling (391) 235-00-15, 217-80-30 or through the website in the Appointment with a doctor section.

In this article you can learn in detail about the features of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Clinic

The main symptoms of ADHD are attention deficit, hyperactivity and impulsivity . These signs appear at a very early age. Since many healthy children also have these symptoms, but to a lesser extent, or caused by another disorder, it is important for the child to have a thorough examination and an appropriate diagnosis made by a highly qualified specialist. nine0016

Symptoms of ADHD appear over many months, usually symptoms of impulsivity and hyperactivity precede symptoms of inattention, which may not appear for a year or more. In different social conditions, different symptoms appear, depending on the requirements for self-control of the child in a particular situation. A child who "can't sit still" or who ruins everything is visible at school, but an inattentive dreamer may not be noticed. An impulsive child who acts first and thinks later may be thought to have "discipline problems", while a passive or slow child may simply be considered not very motivated. However, both can have different types of ADHD. All children are sometimes restless, sometimes they do something without thinking, sometimes they float away somewhere in their dreams. When hyperactivity, distractibility, poor concentration, or impulsivity begin to affect school performance, relationships with other children, or behavior at home, ADHD may be suspected in a child. Since symptoms vary greatly depending on social conditions, it is very difficult to diagnose ADHD. This is especially true in cases where attention deficit is the primary symptom.

In different social conditions, different symptoms appear, depending on the requirements for self-control of the child in a particular situation. A child who "can't sit still" or who ruins everything is visible at school, but an inattentive dreamer may not be noticed. An impulsive child who acts first and thinks later may be thought to have "discipline problems", while a passive or slow child may simply be considered not very motivated. However, both can have different types of ADHD. All children are sometimes restless, sometimes they do something without thinking, sometimes they float away somewhere in their dreams. When hyperactivity, distractibility, poor concentration, or impulsivity begin to affect school performance, relationships with other children, or behavior at home, ADHD may be suspected in a child. Since symptoms vary greatly depending on social conditions, it is very difficult to diagnose ADHD. This is especially true in cases where attention deficit is the primary symptom. nine0016

nine0016

There are three types of ADHD. There is a hyperactivity/impulsivity predominance type (where there are few signs of inattention), a attention-deficit predominance type (minor signs of hyperactivity/impulsivity; and a mixed type (which has both attention deficit hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms).

Hyperactive/impulsive

Hyperactive children seem to be constantly on the move and on their feet They destroy everything around them by grabbing and playing with everything in sight or talking incessantly They find it difficult to sit still at the table during lunch and school, or calmly communicate They squirm and fidget in chairs, or roam around the room Or twirl their feet, touch everything, tap loudly with a pencil Hyperactive teenagers or adults feel inner anxiety They often tell that they need to be busy and may try to do nes how many things at the same time. nine0016

Impulsive children cannot control their immediate reaction or think before doing something. They often blurt out inappropriate comments, show their emotions uncontrollably, and act without considering the consequences of their behavior. Their impulsiveness prevents them from waiting for something they want or their turn in the game. They may take a toy from another child or hit if they are upset. Even teenagers or adults impulsively choose activities that bring even a small but immediate return, instead of doing something that requires a lot of effort, but also provides a much larger reward - but later. nine0016

They often blurt out inappropriate comments, show their emotions uncontrollably, and act without considering the consequences of their behavior. Their impulsiveness prevents them from waiting for something they want or their turn in the game. They may take a toy from another child or hit if they are upset. Even teenagers or adults impulsively choose activities that bring even a small but immediate return, instead of doing something that requires a lot of effort, but also provides a much larger reward - but later. nine0016

Some signs of hyperactivity-impulsivity are manifested in the fact that children:

- Feel restless, often wiggle their arms and legs or fidget in a chair

- Run, climb and leave their place in situations where they need to sit and be quiet

- Shout out answers before the whole question is heard

- Having difficulty standing in line or waiting their turn in a game

Carelessness

It is difficult for inattentive children to concentrate on one thing, the task can tire them after a few minutes after it has begun. If they are doing something they really enjoy, they have no problem concentrating. But on purpose, consciously focusing on organizing and completing a task, on learning something new, is hard for them.

If they are doing something they really enjoy, they have no problem concentrating. But on purpose, consciously focusing on organizing and completing a task, on learning something new, is hard for them.

Homework is especially difficult for these children. They forget to write it down or leave it at school. They forget to bring a textbook or bring the wrong one. If, nevertheless, homework is done, it is full of mistakes and blots. Homework often causes despair in both the child and the parent. nine0016

Criteria for attention deficit disorder are as follows:

- Children are easily distracted by irrelevant sights and sounds

- They do not pay attention to details and make mistakes due to their carelessness

- Rarely follow instructions carefully and completely, forget or lose things such as small toys, pencils, books and tools needed to complete the task

- Often rushing from one unfinished business to another

Children diagnosed with ADHD with attention disorders rarely have problems due to hyperactivity or impulsivity, but have significant difficulty concentrating. They appear dreamy, "absent," easily embarrassed, and move slowly and sluggishly. They find it difficult to process information as quickly and accurately as other children. When a teacher gives verbal or written instructions, it is difficult for such a child to understand what he or she should do, and they make many mistakes. In addition, such a child may sit still, be well-behaved, and even seem immersed in work, but he does not pay enough attention to it or does not fully understand the task or instructions. nine0016

They appear dreamy, "absent," easily embarrassed, and move slowly and sluggishly. They find it difficult to process information as quickly and accurately as other children. When a teacher gives verbal or written instructions, it is difficult for such a child to understand what he or she should do, and they make many mistakes. In addition, such a child may sit still, be well-behaved, and even seem immersed in work, but he does not pay enough attention to it or does not fully understand the task or instructions. nine0016

These children do not have serious problems with impulsivity or hyperactivity in the classroom, at school or at home. They get along better with other children than those with the more impulsive and hyperactive type of ADHD. They may not experience the social problems of mixed ADHD at all. Too often, their attention problems are overlooked. And they need help just as much as kids with other forms of ADHD who have more obvious problems in the classroom.

Is it really ADHD? nine0019

Not everyone with excessive hyperactivity, inattention or impulsivity has ADHD. Since most people sometimes say things they didn't want to say, jump from one task to another, be disorganized and forgetful, the question arises: how experts determine whether a child has ADHD or not.

Since most people sometimes say things they didn't want to say, jump from one task to another, be disorganized and forgetful, the question arises: how experts determine whether a child has ADHD or not.

Since every child has these problems from time to time, this diagnosis requires that such behavior be unacceptable for a person of this age. The diagnostic standards also contain specific criteria for identifying symptoms that are indicative of ADHD. Behavioral problems should start in early childhood, before age 7, and last for at least 6 months. Most importantly, such behavior must actually create severe problems in at least two areas of a person's life: at school, on the playground, at home, in the group of people to which he belongs, or in the environment where he has to communicate. Therefore, if a person has these symptoms, but they do not disrupt their school life and relationships with friends, then they will not be diagnosed with ADHD. Nor would such a diagnosis be given to a child who is overly active on the playground but has no difficulty in other social settings. nine0016

nine0016

To determine if a child has ADHD, psychiatrists consider several crucial questions: is the behavior excessive, how long has it been present, is it creating difficulties in life? That is, does this behavior occur more often in a child than in peers? Is this a permanent problem or is it a response to a temporary situation? Do these behavioral problems occur in multiple social settings, or only in one particular place—on the playground or at school?

Diagnosis

Some parents notice signs of inattention, hyperactivity and impulsivity in their infant long before they start school. The child may lose interest in the game and the TV show, or run aimlessly back and forth, not listening to the parents at all. But since all children develop differently and vary greatly in personality traits, temperament and activity, it would be useful to hear the opinion of an expert on how acceptable such behavior is at a given age. Parents can see a pediatrician, child psychologist, or psychiatrist to determine if their child has attention deficit hyperactivity disorder or, more commonly at that age, it's just immaturity or unusually high energy. nine0016

nine0016

ADHD may be suspected by a parent or caregiver, or may go unnoticed until the child has problems at school. Due to the fact that ADHD most strongly affects a child's activities in school, sometimes the teacher is the first to determine that the child is hyperactive or not attentive enough, and can point this out to parents and / or the school psychologist. Since educators work with many children, they begin to understand how "average" children usually behave in lessons that require attention and self-control. However, teachers sometimes fail to notice the needs of children who are inattentive and passive, and also quiet and cooperative, such as children with an inattentive form of ADHD. nine0016

Specialists who can diagnose

If ADHD is suspected, who is the first place a family can contact? Which specialists should be contacted?

Diagnosis should ideally be made by a specialist in the field of ADHD. Psychiatrists, pediatricians, neurologists - these are the specialties most often involved in the differential diagnosis of ADHD.

Parents can start by contacting their pediatrician. Some pediatricians can make the diagnosis themselves, but more often they refer parents to a suitable psychiatrist they know and trust. nine0016

Psychiatrists are doctors who specialize in the diagnosis and treatment of childhood mental disorders. A psychiatrist can provide treatment and prescribe any necessary medications. Psychologists can also treat ADHD. They can help the family develop ways to deal with the disorder. Neurologists—doctors who treat disorders of the central and peripheral nervous systems—can also diagnose ADHD and prescribe medications. But unlike psychiatrists and psychologists, they cannot provide treatment and correction of the emotional aspects of the disorder. nine0016

The main task of the specialist is to collect information that excludes other possible reasons for the child's behavior. Here are the possible causes of behavior similar to ADHD:

- A sudden change in a child's life - the death of a parent or grandparent; divorce of parents; job loss by parents

- Undiagnosed epilepsy

- Otitis media causing hearing loss

- Somatic diseases affecting brain functions nine0032 Teaching below the level of one's ability due to learning disabilities

- Anxiety or depression

In most cases, the child's social adaptation and mental health are assessed. He is given tests to determine the level of intelligence and school knowledge to see if the child has learning difficulties and in what subjects these problems occur.

He is given tests to determine the level of intelligence and school knowledge to see if the child has learning difficulties and in what subjects these problems occur.

After that, the specialist creates a general picture of the child's behavior. What type of ADHD behavior is the child exhibiting? How often? In what situations? How long ago did he have it? How old was the child then? Are the behavior problems chronic and permanent, or are they temporary due to some cause? How seriously do behavioral problems interfere with the child's friendships, school activities, home life, or participation in social activities? Does the child have other related problems? The answers to these questions will help determine whether the child's hyperactivity, impulsivity, and inattention are indeed significant and have been around for a long time. If so, the child may be diagnosed with ADHD. nine0016

A correct diagnosis often clears up confusion by clarifying the causes of a child's problems, and this allows parents and children to move on with more accurate information about what is wrong and what can be done to help. Once the disorder is diagnosed, the child and family can begin to receive the combination of educational, medical, and emotional support they need. This may include providing guidance to school staff, selecting the most appropriate class, selecting the correct drug, and helping parents establish and maintain control over their child's behavior. nine0016

Once the disorder is diagnosed, the child and family can begin to receive the combination of educational, medical, and emotional support they need. This may include providing guidance to school staff, selecting the most appropriate class, selecting the correct drug, and helping parents establish and maintain control over their child's behavior. nine0016

What causes ADHD

One of the very first questions parents ask is "Why? What went wrong?" "Am I to blame for what happened?" There is currently little direct evidence that ADHD can only arise from adverse social factors or poor parenting. The most well-founded causes seem to lie in the fields of neuroscience and genetics. This does not mean that environmental factors do not affect the severity of the disease, in particular, the degree of damage and suffering inflicted on the child may depend on them, but such factors do not cause ADHD by themselves. nine0016

Parents should focus on the future and look for the best possible ways to help their child. Scientists are studying the causes in an effort to find better treatments, and perhaps someday even ways to prevent ADHD. They are finding more and more evidence that ADHD does not depend on the situation in the family, but follows from biological causes. Knowing this, you can remove a heavy burden of guilt from parents who may blame themselves for the child's misbehavior.

Scientists are studying the causes in an effort to find better treatments, and perhaps someday even ways to prevent ADHD. They are finding more and more evidence that ADHD does not depend on the situation in the family, but follows from biological causes. Knowing this, you can remove a heavy burden of guilt from parents who may blame themselves for the child's misbehavior.

Over the past decades, scientists have proposed several theories of ADHD. Some of these theories have stalled, while others lead to new lines of research. nine0016

Environmental factors

Studies have shown that there is a possible relationship between smoking and drinking during pregnancy and the likelihood of ADHD. To avoid this, it is better to refrain from using cigarettes and alcohol during pregnancy.

Another environmental factor that may be associated with an increased likelihood of ADHD is high lead levels in young children. Since the use of lead in paint was banned, it can only be found in older buildings, and exposure to toxic levels of lead is not as dominant a cause of ADHD as it once was. Children living in older homes where lead is found in plumbing and lead-based paint surfaces that have been repainted are at risk. nine0016

Children living in older homes where lead is found in plumbing and lead-based paint surfaces that have been repainted are at risk. nine0016

Brain injury

One of the first theories claimed that attention disorders were caused by brain injury. Some children who have had accidents that lead to brain injury may exhibit some of the behaviors that are characteristic of ADHD. But it was found that only a small percentage of children with ADHD had suffered a traumatic brain injury.

Heredity

ADHD is often present in several family members, therefore genetic causes are likely. Studies show that 25% of close relatives of children with ADHD also have this syndrome, while in the general population this figure is approximately 5%. Most studies of twins have now shown that heredity strongly influences the occurrence of this disorder. nine0008 Scientists continue to study the influence of genetics on ADHD and identify the genes responsible for a person's predisposition to ADHD

ADHD treatment

Every family wants to know what treatment will be most effective for their child. Each family should answer this question to their attending physician.

Each family should answer this question to their attending physician.

The results of the study showed that the combined treatment was the most effective. An additional benefit of combination treatment was that these children were successfully treated with lower doses of drugs compared to the drug-only group. nine0016

What treatment should my child receive?

No single treatment can be considered one size fits all for every child with ADHD. Sometimes a child may have unwanted side effects, and this may make the use of drug therapy unacceptable. And if the child also suffers from anxiety or depression in addition to ADHD, then the combination of drug treatment and psychotherapy is the best option. The child's needs and personal medical history must be carefully considered. nine0016

Things to remember about ADHD medications

• ADHD medications help many children concentrate and be more successful at school, at home or on the playground. The ability to avoid negative experiences can really help children avoid alcohol or drug addiction in the future and cope with other emotional problems.

The ability to avoid negative experiences can really help children avoid alcohol or drug addiction in the future and cope with other emotional problems.

• About 80 percent of children who need medication for ADHD continue to take medication into adolescence. More than 50 percent need the drug as adults. nine0016

Family and child with ADHD

Drug therapy can help a child in his daily life. It will be easier for him to control some of the behavior problems that lead to difficulties in relationships with parents and siblings. But in order to remove the despair accumulated over a long period of time, the habit of blaming and anger takes time. Both parents and children may need specialized help to learn how to manage their child's behavior. In such cases, psychiatrists and psychotherapists can counsel the family and the child, helping them develop new skills, attitudes, and ways of communicating with each other. During individual conversations, a psychotherapist helps children with ADHD learn to improve their self-esteem. In addition, a psychotherapist can help them find and build on strengths, deal with everyday problems, and control attention and aggression. Sometimes psychological counseling is necessary only for a child. But more often, because a child's disorder affects the family as a whole, all family members need help. The therapist helps the family find the most appropriate ways to deal with the child's destructive behavior and suggests new options. If the child is small, the therapist works mainly with the parents, teaching them how to cope with the child and improve his behavior. nine0016

In addition, a psychotherapist can help them find and build on strengths, deal with everyday problems, and control attention and aggression. Sometimes psychological counseling is necessary only for a child. But more often, because a child's disorder affects the family as a whole, all family members need help. The therapist helps the family find the most appropriate ways to deal with the child's destructive behavior and suggests new options. If the child is small, the therapist works mainly with the parents, teaching them how to cope with the child and improve his behavior. nine0016

There are different methods of influence. Having information about various methods of influence, it is easier for the family to choose the right psychotherapist.

Psychotherapy aims to help people with ADHD love and accept themselves for who they are, despite the disorder. It does not deal with the symptoms or causes of the disorder. During psychotherapy, patients talk to the therapist about sad thoughts and feelings, identify self-destructive behaviors, and look for alternative ways to manage their emotions. During the conversation, the therapist tries to help them understand how they can change, or how best to cope with their disorder. nine0016

During the conversation, the therapist tries to help them understand how they can change, or how best to cope with their disorder. nine0016

Psychological Correction helps people develop more effective ways of dealing with immediate problems. It helps the child to change his way of thinking and psychologically adapt rather than to understand his feelings and actions - and thus can change the behavior of the child. Support can take the form of practical help, such as help with homework or schoolwork, or in dealing with emotionally stressful situations. Or support can be about self-control of behavior, self-reward, and self-rewarding for actions performed in a desired way - say, if a person coped with anger or thought before doing something. nine0016

Communication training can also help children learn new behaviors. By teaching communication skills, the therapist discusses and models appropriate behaviors that are important for developing and maintaining relationships with others in situations such as waiting in line, sharing toys, asking for help, or responding appropriately to teasing. Subsequently, the children are given an attempt to practice these skills. For example, a child may learn to read other people's facial expressions and tone of voice in order to answer them correctly. Communication skills training helps a child find better ways to play or interact with other children. nine0016

Subsequently, the children are given an attempt to practice these skills. For example, a child may learn to read other people's facial expressions and tone of voice in order to answer them correctly. Communication skills training helps a child find better ways to play or interact with other children. nine0016

support groups help parents connect with others who have similar problems and who are concerned about their children with ADHD. Members of support groups meet regularly (eg, monthly) to hear lectures from ADHD specialists, share frustrations and successes, get referrals to qualified professionals, and learn about their work. Their strength lies in numbers, and by sharing their experiences with others who have similar problems, they learn things that they could never have known if they were alone. nine0016

Parenting Skills Training , provided by psychotherapists, provides parents with methods and techniques to manage their child's behavior. One such method is the use of badges or points systems to immediately assess good behavior or performance. Another method is to "time out" or isolate the child in a chair or in the bedroom when he becomes too rebellious or out of control. During "time-outs" the child is removed from the disturbing situation and sits quietly alone for a while to calm down. Parents are also sometimes advised to spend time with their child every day doing something enjoyable and relaxing. During this time spent with the child, the parent looks for opportunities to note and point out what the child is doing well and to praise him or her for success and ability. nine0016

One such method is the use of badges or points systems to immediately assess good behavior or performance. Another method is to "time out" or isolate the child in a chair or in the bedroom when he becomes too rebellious or out of control. During "time-outs" the child is removed from the disturbing situation and sits quietly alone for a while to calm down. Parents are also sometimes advised to spend time with their child every day doing something enjoyable and relaxing. During this time spent with the child, the parent looks for opportunities to note and point out what the child is doing well and to praise him or her for success and ability. nine0016

Rewards and penalties can be an effective way to change a child's behavior. The parent (or teacher) identifies several good behaviors that they want to encourage in the child (for example, asking for a toy rather than grabbing it, or completing a simple task in its entirety). The child is directly told what he must do in order to receive a reward. The child is rewarded when he performs the desired behavior and moderately punished when he does not. The reward may be small - for example, a badge of honor is given to a child for special merits - but it must be something desired for the child to want to earn it. As a punishment, you can remove the badge of honor or give a short "time-out". The goal is to eventually teach the child to control his behavior and choose the most desirable way of behavior. This method works well with all children, although children with ADHD may need additional, more frequent encouragement. nine0016

The child is rewarded when he performs the desired behavior and moderately punished when he does not. The reward may be small - for example, a badge of honor is given to a child for special merits - but it must be something desired for the child to want to earn it. As a punishment, you can remove the badge of honor or give a short "time-out". The goal is to eventually teach the child to control his behavior and choose the most desirable way of behavior. This method works well with all children, although children with ADHD may need additional, more frequent encouragement. nine0016

In addition, parents can learn to create situations for their children in which they can succeed. This may be the case, for example, when parents allow only one or two partners to take part in the game so that their child cannot become overexcited. Or, when a child has trouble completing tasks, they must learn to help their child, break a large task into several smaller ones, and reward the child for completing each small part. Regardless of how parents specifically influence their child's behavior, some general principles will be helpful to most children with ADHD. These principles call for more frequent and even immediate responses to a child's actions (this applies to both rewards and punishments), to take the necessary measures in advance to prevent potentially problematic situations, to look after children more closely and to encourage them in situations when they are not interested or boring. nine0016

Regardless of how parents specifically influence their child's behavior, some general principles will be helpful to most children with ADHD. These principles call for more frequent and even immediate responses to a child's actions (this applies to both rewards and punishments), to take the necessary measures in advance to prevent potentially problematic situations, to look after children more closely and to encourage them in situations when they are not interested or boring. nine0016

Parents can also learn how to use stress management techniques, such as meditation, relaxation techniques and exercise, to help them cope when things go wrong and to respond more calmly to their children's behavior.

Some Simple Ways to Influence Behavior

Children with ADHD may need organizational help. Therefore, you need:

• Schedule. Organize the same routine for every day from the moment you wake up until you go to bed. The schedule should allocate time for homework and play (including outdoor walks and home activities like computer games). Hang this schedule on your refrigerator door or on a stand in your kitchen. If changes need to be made to the schedule, make them as early as possible. nine0016

Hang this schedule on your refrigerator door or on a stand in your kitchen. If changes need to be made to the schedule, make them as early as possible. nine0016

• Get all the essentials in order. Everything must have its own place, and everything must be kept in its place. This applies to clothing, backpacks and school supplies.

• It is necessary to use diaries to control homework. Emphasize the importance of writing down assignments and having all the necessary books at home.

Children with ADHD need a consistent set of rules that are clear and strict. If children follow these rules, give them small rewards. Children with ADHD are often criticized, and they are already waiting for criticism. Try to find examples of your child's good behavior and praise for it. nine0016

Your child with ADHD and the school

You are your child's best advocate. To be a good advocate for your child, learn as much as you can about ADHD and how it affects your child at home, at school, and in community life.

If your child has ADHD symptoms at an early age, has been evaluated, diagnosed and treated with behavior modification, medication, or a combination of both, notify the child's teachers when the child enters school. Then they will be better prepared to assist the child in entering this new world away from home. nine0016