What degree to be a therapist

What Degree Do You Need to Be a Therapist?

If you’re interested in becoming a therapist, having a clear understanding of the right path to get there can make the process easier and more accessible. Therapists are admirable professionals who aid people in living happier and more enjoyable lives.

In fact, the American Psychological Association reports around 75% of those who receive therapy experience beneficial results. If you’re interested in helping people maintain a state of mental well-being, a career as a therapist is a viable way to earn a living while doing what you enjoy. Given the broad nature of the therapy field and related fields — such as counseling — you can benefit from having a clear vision of what these roles entail and how to qualify.

Therapist vs. Counselor: What Are the Differences?

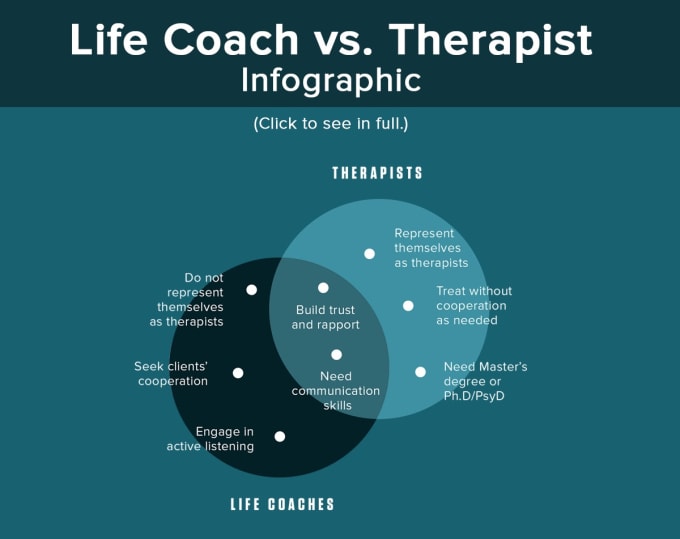

It can be tricky to distinguish between the roles of therapists and counselors. The job duties of these roles often overlap, and to make matters more convoluted, people often use the terms interchangeably. Though it may seem confusing at first, each of these roles has both qualifications and practices that are specific to themselves. To put these roles into perspective, it can be helpful to understand what each role’s responsibilities are and the qualifications required.

Therapists

Therapists are professionals who are licensed in their state to provide therapy to their clients. Therapy often involves a focus on talk therapy and usually aims to explore clients’ pasts to uncover insights about their current feelings, behaviors, or traumas. Therapists typically specialize in a specific field, such as marriage and family therapy. Therapists hold at least a master’s degree, while some choose to obtain a doctorate. If a therapist chooses to advertise their practice as “psychotherapy,” then they must be licensed in the state in which they intend to practice. A licensed therapist is often qualified to practice specific types of counseling if they choose to, and in some cases do.

Counselors

Counselors, much like therapists, aim to help their clients with specific problems. However, counselors tend to focus more on helping their clients deal with psychological, mental health, and substance abuse issues than their therapist counterparts, who may concentrate on a client’s relationship-based and social needs. It is typical for counselors to provide their clients with coping strategies and advice to deal with their problems practically and immediately. Counselors can be sought out if someone has a problem which they want to receive treatment for a short duration of time, such as anxiety about a new career. Though some counselors are certified, some are not and rules vary in states about who is allowed to practice as a counselor. Some counselors hold only a bachelor’s degree while others are master’s degree holders.

However, counselors tend to focus more on helping their clients deal with psychological, mental health, and substance abuse issues than their therapist counterparts, who may concentrate on a client’s relationship-based and social needs. It is typical for counselors to provide their clients with coping strategies and advice to deal with their problems practically and immediately. Counselors can be sought out if someone has a problem which they want to receive treatment for a short duration of time, such as anxiety about a new career. Though some counselors are certified, some are not and rules vary in states about who is allowed to practice as a counselor. Some counselors hold only a bachelor’s degree while others are master’s degree holders.

__________

Advance your career and purpose.

Start a graduate degree at PLNU.

__________

How to Become a Therapist

When pursuing a career as a therapist, there are several requirements that you’ll have to complete before beginning your career. Having a clear understanding of this process can make becoming a therapist less daunting and more manageable. Here are the steps you’ll need to complete to become a licensed therapist:

Having a clear understanding of this process can make becoming a therapist less daunting and more manageable. Here are the steps you’ll need to complete to become a licensed therapist:

Step #1: Obtain a Bachelor’s Degree

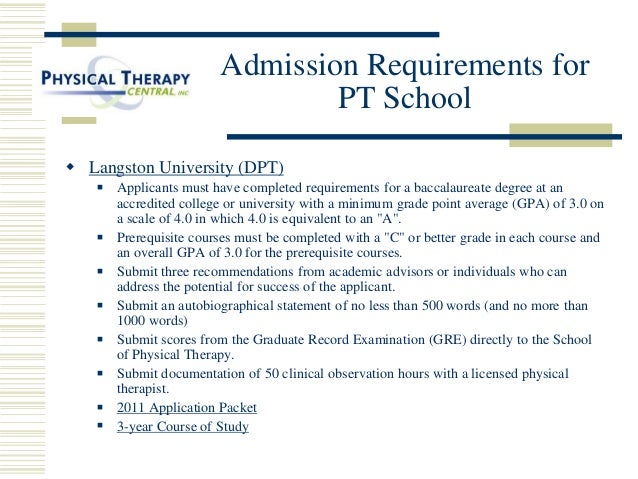

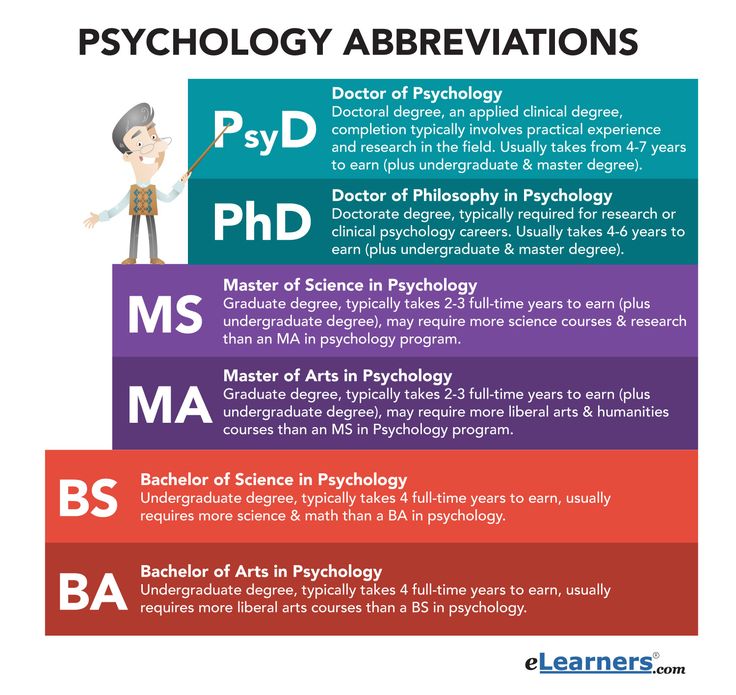

The first thing you’ll need to do to become a licensed therapist is earn a bachelor’s degree. If you’re intent on becoming a therapist, then you should major in psychology or a related field. Gaining a foundational degree that exposes you to principles and practices of psychology will help prepare you for graduate school, and ultimately, a career as a licensed therapist.

Step #2: Obtain a Master’s Degree

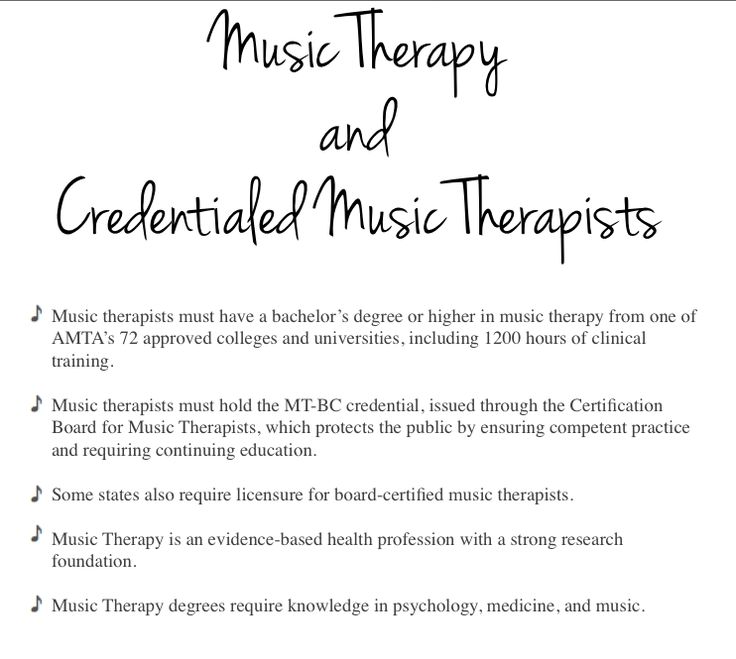

Once you’ve obtained your bachelor’s degree, it’s time to pursue a master’s degree. When choosing your master’s program, it’s important to be clear about which specific field of therapy you wish to enter. Most fields of therapy require you to have a certification before practicing, and many certificates require that you have a master’s degree before certification.

The master’s degree you pursue will depend on which certification you eventually intend to obtain. It will typically be a master’s degree in counseling, psychology, or social work. Be sure to know the specific requirements of your prospective certification before applying to a graduate degree program to ensure that you’re meeting the necessary requirements.

Step #3: Gain Clinical Experience

To become a certified therapist, you’ll need to gain around 3,000 hours of supervised clinical hours, though this can vary depending on different certification and state requirements. Master’s degree programs that meet the requirements of specific licenses will often offer guidance and support when it comes to gaining the hours needed to become a licensed therapist.

Step #4: Become Licensed or Certified

There are several avenues you can pursue to become a licensed therapist. Examples include the Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist (LMFT) certification and Licensed Professional Clinical Counseling (LPCC) certification. Each certification has unique requirements, such as a certain amount of supervised clinical work and master’s degrees that meet specific standards. It’s important to have a clear idea of which certification you eventually intend to obtain, as this will inform which program you’ll choose when pursuing your master’s degree.

Each certification has unique requirements, such as a certain amount of supervised clinical work and master’s degrees that meet specific standards. It’s important to have a clear idea of which certification you eventually intend to obtain, as this will inform which program you’ll choose when pursuing your master’s degree.

Therapist Licensing Requirements and Salary

To become a licensed therapist, you’ll need to finish all of the requirements of the specific licensure path you wish to pursue. There are various licenses, each with its own requirements, which typically include at least a bachelor’s degree, clinical experience, and in many cases, a master’s degree.

For example, If you plan on becoming a licensed marriage and family therapist in the state of California, you’ll need to obtain a Licensed Marriage and Family Therapist (LMFT) certificate to practice. The LMFT requires that you first receive a master’s degree in a relevant field and gain a certain amount of clinical experience before becoming certified. Whatever certification you plan to pursue, be sure to choose a program that meets the requirements for that license. Choosing a program that doesn’t meet the criteria for the license you’re pursuing can cost you a tremendous amount of time and money unnecessarily. One program that does meet the requirements for certification is Point Loma Nazarene University’s Master of Arts in Clinical Counseling.

Whatever certification you plan to pursue, be sure to choose a program that meets the requirements for that license. Choosing a program that doesn’t meet the criteria for the license you’re pursuing can cost you a tremendous amount of time and money unnecessarily. One program that does meet the requirements for certification is Point Loma Nazarene University’s Master of Arts in Clinical Counseling.

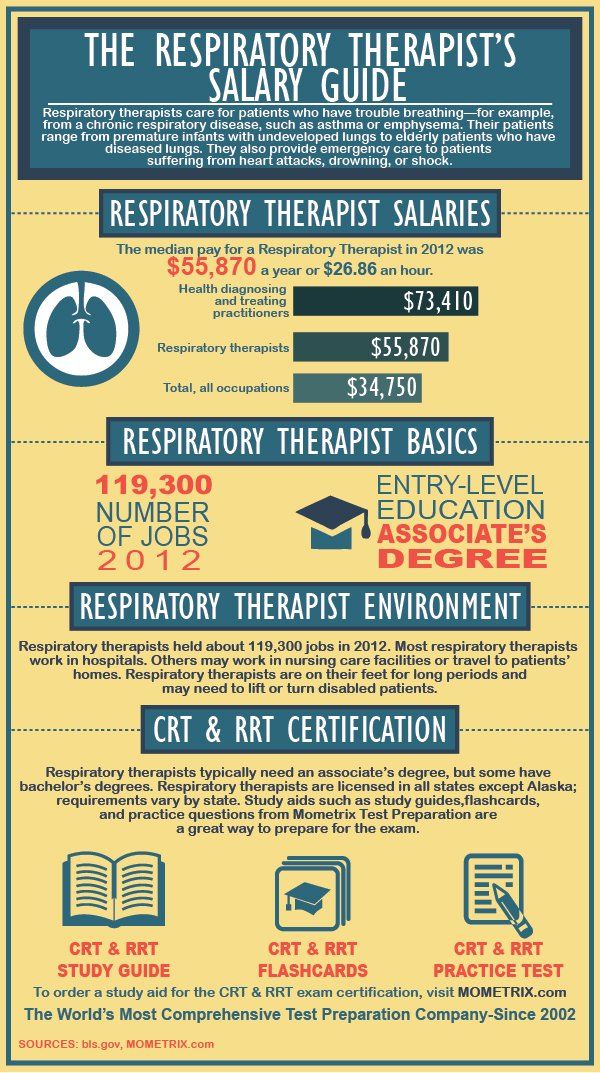

Therapist salaries can vary widely based on field, level of education, location, and industry. According to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the average annual salary of a licensed marriage and family therapist is $49,880 while they report that the annual median income of all other therapists is $59,500. To gain a clearer view of licensed marriage and family therapist salaries, it’s important to unserstand that salaries can vary depending on both region and industry. For example, according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, the annual mean wage for marriage and family therapists who work in the home health industry was $97,780 as of 2021 while the annual mean wage for marriage and family therapists practicing in Utah was $86,490. Other industries that boast higher than average marriage and family therapist salaries includephysician’s offices and schools.

Other industries that boast higher than average marriage and family therapist salaries includephysician’s offices and schools.

How Long Does It Take To Become a Therapist?

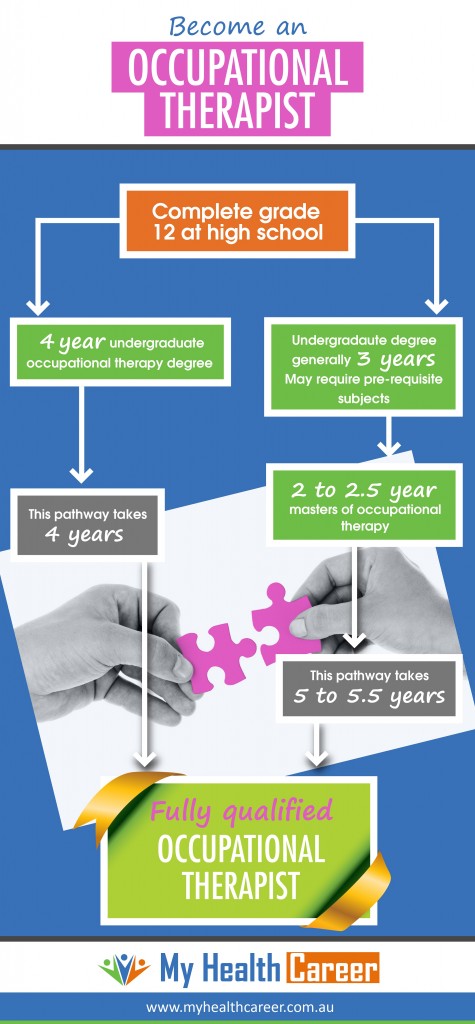

The process of becoming a therapist can vary depending on which path you choose and the amount of education you choose to pursue. Those who intend to stop schooling after a master’s degree can typically expect to spend around seven to ten years studying and becoming certified before becoming a therapist. This includes the typical four years and two to three years typically needed to obtain a bachelor’s degree and master’s degree respectively.

After schooling, most certification requires you to gain clinical work under the supervision of other professionals for a certain amount of time. This amount differs depending on the license, but you can typically expect to need around 3,000 hours to meet therapist licensure requirements.

Discover How a Master of Arts in Clinical Counseling Can Elevate Your Career

By gaining on-campus clinical experience, professional training, and career guidance, Point Loma Nazarene University can help you elevate your career and pursue the therapist role you’ve always aspired to reach. PLNU’s Master of Arts in Clinical Counseling program offers you the opportunity to meet the requirements you need to gain LMFT and LPCC certification and take your professional career to the next level. Request more info here or apply today to begin your journey of becoming a licensed therapist.

PLNU’s Master of Arts in Clinical Counseling program offers you the opportunity to meet the requirements you need to gain LMFT and LPCC certification and take your professional career to the next level. Request more info here or apply today to begin your journey of becoming a licensed therapist.

How to Become a Therapist

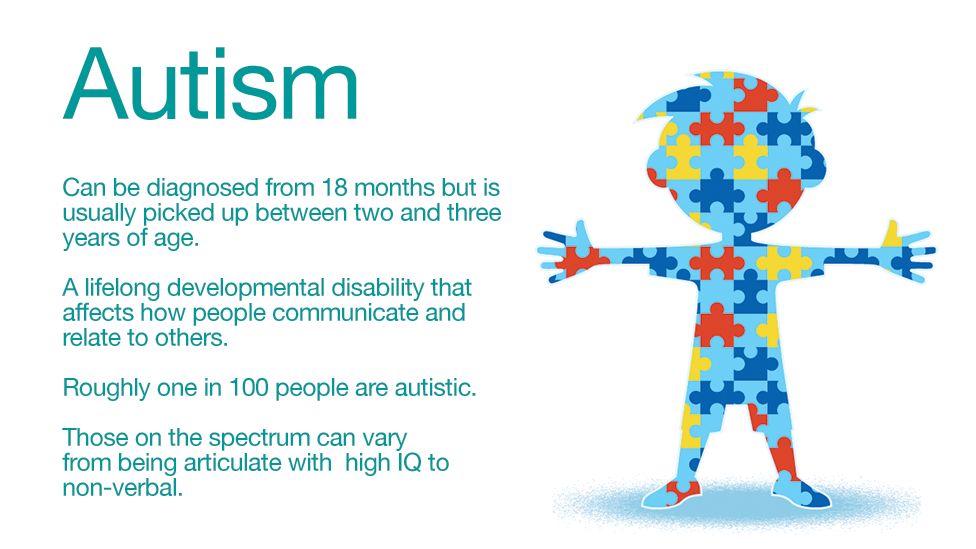

The word “therapist” is a broad term that can encompass many mental health professionals. Counselors, social workers, marriage and family therapists, and psychologists are all considered therapists.

Depending on the individual, the geographic area in which they practice and their respective state licensure or regulatory practices, many mental health professionals use the term “therapist” to speak broadly about themselves. Regardless of what term is used, providing mental health services to clients is a meaningful way to offer help and support to others at the individual and community levels.

While the term “therapist” is often used as a general term to encompass the mental health field as a whole, “it is important to note that there are very real and significant differences between and among the mental health professions,” said Kristi B. Cannon, PhD, LPC, NCC, director of counseling programs, assessment and evaluation at Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU).

Cannon, PhD, LPC, NCC, director of counseling programs, assessment and evaluation at Southern New Hampshire University (SNHU).

These differences include:

- The client population being served

- The types of intervention being offered

- The depth of the issue being addressed

While the term “therapist” can be used across professions, state licensure boards restrict the use of particular terms such as “licensed professional counselor” or “licensed psychologist” to “those who have received specific educational, exam and practice requirements for licensure in that area,” Cannon said.

And, because educational training, ethical guidelines and licensure are critical to each of these fields, “it is important for potential clients to understand that the term ‘therapist’ is not regulated,” Cannon said. Therefore, the term “therapist” can be used by anyone across the profession.

What’s the Difference Between a Therapist and a Counselor?

These terms are often used interchangeably. “Both a therapist and a counselor engage in a helping relationship,” said

Metoka L. Welch, PhD, LCMHC (NC), director of counseling programs for the learning environment at SNHU. The difference between the two lies within the goal of the professional.

“Both a therapist and a counselor engage in a helping relationship,” said

Metoka L. Welch, PhD, LCMHC (NC), director of counseling programs for the learning environment at SNHU. The difference between the two lies within the goal of the professional.

A therapist “provides mental health therapy to clients,” Cannon said, while a counselor is a specific type of mental health professional whose offerings “align with a wellness model of healing” and who “believes in the empowerment of clients to accomplish their goals in mental health, career and education.” According to Cannon, there are many different counselor roles to consider.

Just like with the term “therapist,” there can be distinct educational, training and licensure requirements for each of these professions.

The type of professional counselor most often associated with “therapist” is a clinical mental health counselor. This person “is someone who provides direct client counseling in a private practice, hospital or community-based setting,” Cannon said.

Learn more about how to become a mental health counselor.

What Does it Take to Become a Therapist?

The first step toward becoming a therapist is to decide which type of therapy you wish to provide.

These are some common pairings of interests and career pathways, according to Welch:

- Counseling or individual therapy is suitable for people who want to work with clients one-on-one

- Clinical mental health counseling can be good for people who want a broad scope of knowledge to help people with a variety of mental health needs

- Marriage and family therapy might be a good fit if you know you want to provide services to couples and families in a group setting

- Social work is a good fit if you are interested in connecting people to resources

After you determine which area of counseling you would like to pursue, go to your state’s licensing board website to determine what educational credentials you need. “Then, look into programs that offer the qualifying curriculum,” said Welch.

“Then, look into programs that offer the qualifying curriculum,” said Welch.

What Degree Do You Need to Become a Therapist?

Most therapist positions require at least a master's degree, meaning you must first earn a bachelor's degree. Welch suggests choosing a major in the social sciences, such as:

- Bachelor's degree in psychology: Study how the mind works and develop research skills through courses such as lifespan development, abnormal psychology and statistics. You can choose to add concentrations relevant to therapist specializations such as addictions, child and adolescent development and mental health.

- Bachelor's degree in sociology: Explore human behavior as it relates to social interactions and dynamics with an undergraduate degree in sociology. This degree program can help you gain new and broad perspectives and develop skills in research, analysis and problem-solving.

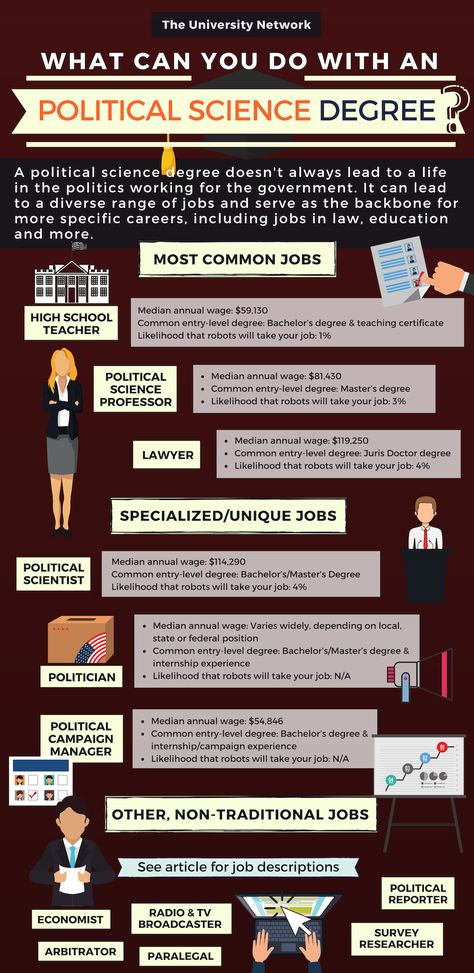

If you already have a bachelor’s degree in another field, do not worry. “It has been my experience that counseling programs are understanding that people are often enrolling in counseling programs as a second career, so their undergraduate degree could be in political science or, in my case, English," Welch said. Most bachelor’s degrees will provide the foundational concepts and information you will need to pursue graduate degrees.

“It has been my experience that counseling programs are understanding that people are often enrolling in counseling programs as a second career, so their undergraduate degree could be in political science or, in my case, English," Welch said. Most bachelor’s degrees will provide the foundational concepts and information you will need to pursue graduate degrees.

For most therapist specialties, such as clinical mental health counseling or clinical social work, the minimum education needed is a master’s degree. You might consider one of these master's degrees:

- Master's degree in counseling: Learn how to provide mental health counseling to a range of clients. Through studying theories, strategies and techniques, you can grow skills relating to all aspects of counseling practice, including consultation, treatment, intervention and prevention. This degree is designed to help you become a counselor.

- Master's degree in psychology: Dive deeper into the world of cognitive and social psychology with a degree that can help you become a psychologist.

If you know you want to work with a particular audience, you might also consider specializing your psychology degree. For example, you might pursue a master's in child psychology and development.

If you know you want to work with a particular audience, you might also consider specializing your psychology degree. For example, you might pursue a master's in child psychology and development.

Karen Raquel Quezada '21G became an in-home therapist shortly after earning her master's degree in psychology at SNHU. She first became interested in this field of work while obtaining a criminal justice degree – another discipline within the social sciences.

While working on her master's degree, Quezada felt each of her instructors and their varying backgrounds brought a lot of value to her. "The instructors were of great help (to) me," she said. "Their feedback allowed me to have a sense of knowledge of my strengths and things that I needed to work on."

Completing her capstone project was especially eye-opening for Quezada. It allowed her to reflect on all that she learned in her program and emerge important takeaways involving ethics, boundaries and more that she uses in her role as an in-home therapist.

"I do feel that my degree was worth it," she said. "It opened doors for me. It allowed me to grow in my personal and professional life."

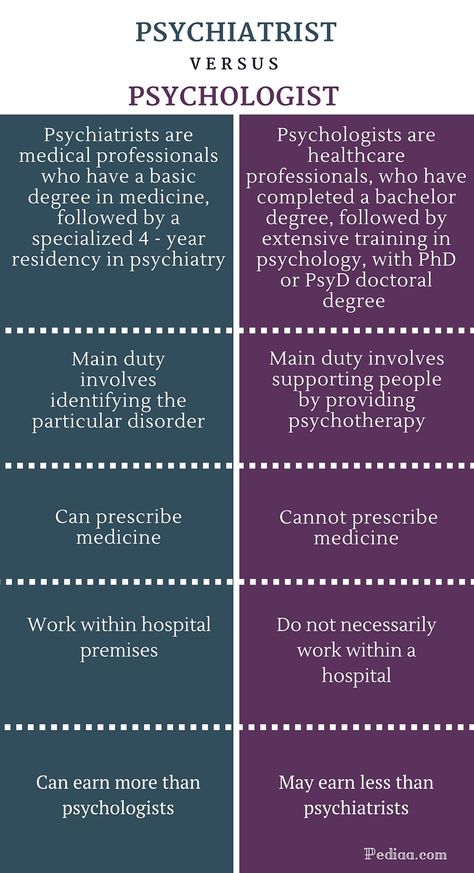

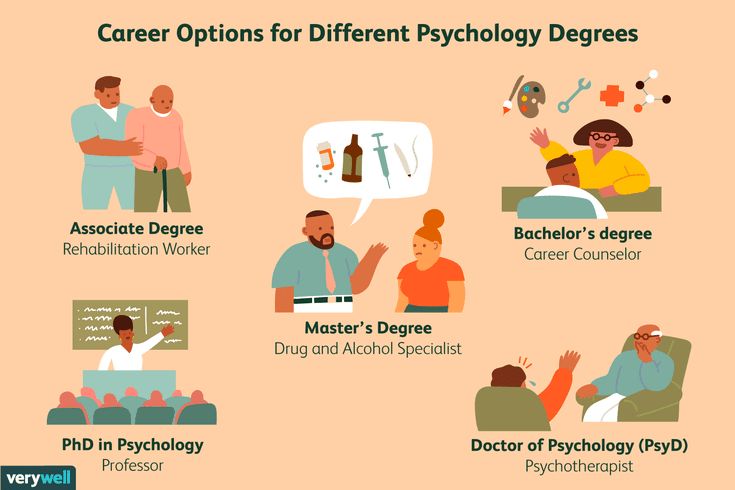

You may find that a doctorate is required for certain specialty areas, such as a clinical psychologist or counselor educator. And to become a psychiatrist, “you need (to) be a medical doctor,” Welch said. If you're wondering how these professions vary, discover the difference between a psychologist and a psychiatrist.

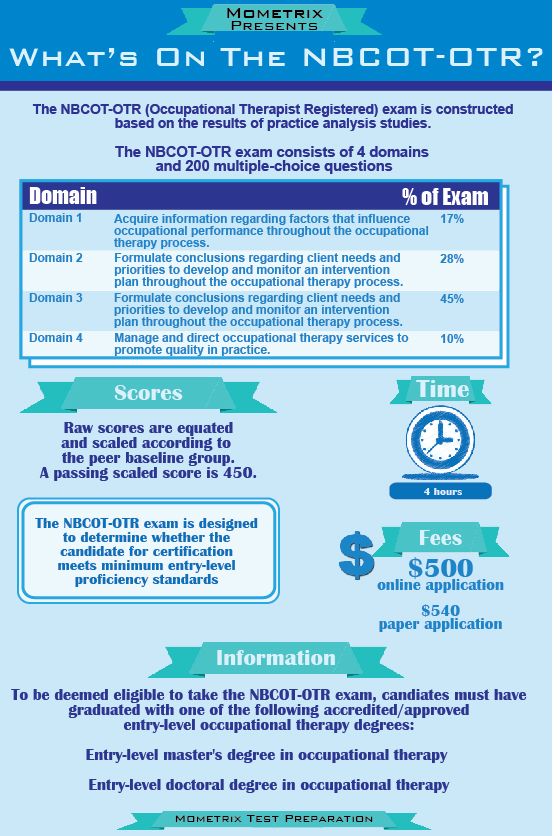

What Kind of License is Needed?

It's important to note that there are different types of licenses required for different counseling specialties. The type of license required is determined by the mental health field you choose and the state in which you intend to practice.

“Requirements for licensure include a set number of clinical hours completed under the supervision of an approved supervisor as well as passing required state licensure exams,” Cannon said.

Different types of licenses include:

- Licensed clinical mental health counselor (LCMHC)

- Licensed clinical professional counselor (LCPC)

- Licensed clinical psychologist (LCP)

- Licensed marriage and family therapist (LMFT)

- Licensed professional counselor (LPC)

Licensure requirements are top of mind at some counseling schools. For example, SNHU's online CACREP-accredited clinical mental health counseling degree is designed to help you meet the educational requirements in most U.S. states. It's important to see if there are any additional qualifications in your state to achieve licensure.

For example, SNHU's online CACREP-accredited clinical mental health counseling degree is designed to help you meet the educational requirements in most U.S. states. It's important to see if there are any additional qualifications in your state to achieve licensure.

How Long Does it Take to Become a Therapist?

You'll need to start your higher education with a bachelor's degree, which is often referred to as a four-year degree. A graduate degree is needed as well. The time it takes to get a master's degree varies by school and your pacing, but they are typically known to take two years.

Quezada's master's degree took her two years to complete as a mom working full-time. "This program had the opportunity for online classes, which was something I really needed as a single working parent," she said.

If you're wondering how online classes work, exactly, the format is similar to that of a face-to-face class; you can expect to participate in class discussions and complete assignments such as academic papers. The difference is you have the flexibility to decide when and where you complete your work each week.

The difference is you have the flexibility to decide when and where you complete your work each week.

Some types of therapy practice, such as a counseling psychologist, “will need a PhD in Counseling Psychology as the minimum requirement for licensure,” said Cannon. Other types of therapy practice require a master’s degree.

Licensed professional counselors must have a master’s degree in counseling, “which includes the educational requirements established by the state counseling licensure board” to practice, said Cannon.

While in school, you will likely complete a practicum and gain internship experience. Depending on your state and area of specialty, “you will need to complete 2-4 years of post-graduate experience in order to be licensed,” Welch said. “I often tell students that (becoming a therapist) is a 2–5-year investment.”

Some master's-level graduates land therapist positions right away. As Quezada wrapped her final term at SNHU, she said her supervisor was already considering her growth within the organization. This led to her promotion to a master's-level clinician.

This led to her promotion to a master's-level clinician.

Are Therapists in Demand?

The demand is growing for therapists and mental health professionals. “This is due to a combination of factors,” Cannon said, “including the fact that mental health issues have gained more prominence in society over the last few years.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has increased the need for services, and, right now, “many licensed therapists have waitlists,” said Welch.

In addition to the pandemic, an increase in awareness of concepts like self-care, work-life balance and even mental health days, have helped “normalize mental health issues as part of a collective sense of overall health,” Cannon said.

There are many possibilities to build a robust and meaningful career as a therapist. Often, when people think of being a therapist, “they think of working in private practice,” Welch said.

Welch also noted that therapists could work in areas such as:

- Agency settings, where you could help connect clients with community resources

- Community settings, where you could provide mental health support in a prison, rehabilitation facility or mental health center.

- Hospitals, where you could help connect patients to services after they are discharged, as well as provide substance abuse counseling to patients, geriatric mental health and more

- Schools, where you could provide services as the school psychologist

The combined awareness, acceptance and prominence of mental health issues and the need for care “is only growing the field, and I fully anticipate this will continue,” said Cannon.

In fact, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) projects that employment of substance abuse, behavioral disorder, and mental health counselors will grow 23% from 2020 to 2030, which is much faster than the average for all other occupations.

Do Therapists Make Good Money?

Because becoming a therapist is a tremendous time investment, you may not see a higher salary until you are licensed or working in a specialty. “Most people who go into this line of work do so because they had a personal experience with a counselor,” said Welch, “or because they want to make a difference in the world. So, a good bit of the reward of being a therapist is intrinsic.”

So, a good bit of the reward of being a therapist is intrinsic.”

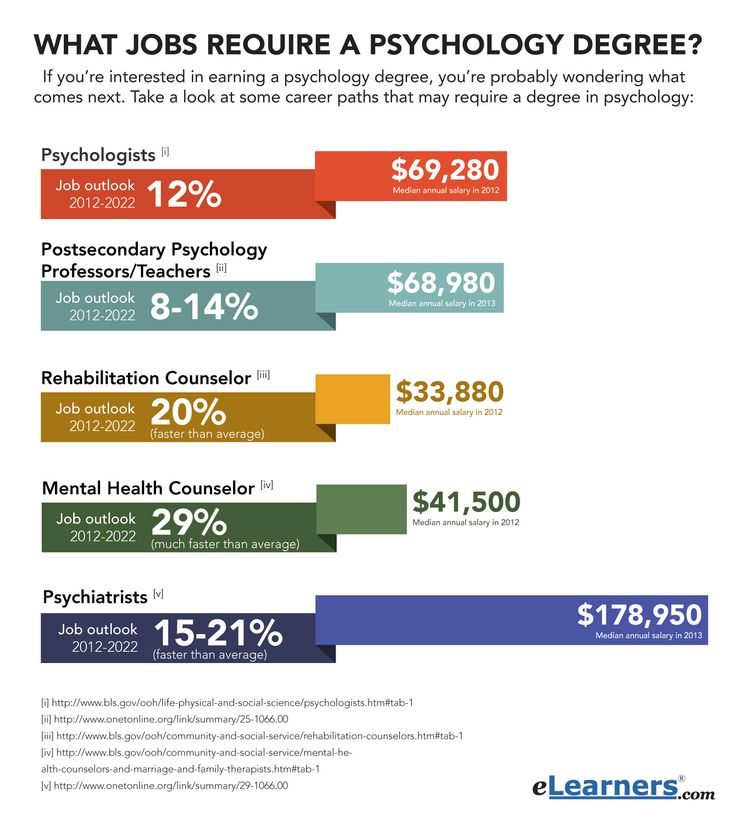

Depending on the educational background, license, area of client focus and geographic location, salaries can vary considerably. For example, BLS notes the median pay for mental health counselors was $48,520 in 2021. Psychologists made a median of $81,040, BLS reported.

Within psychology, there are many paths you can consider. For example, you could become a child psychologist. Marriage and family therapists made a median of $49,880 last year, BLS reported, similar to the median salary for social workers, which was $50,390.

What Makes a Good Therapist?

Being flexible, adaptable and empathetic are at the top of the list of traits that both Cannon and Welch say are important for a therapist to be successful. Welch also notes the ability to be courageous and set boundaries as necessary traits. The willingness to “constantly work on yourself, your biases and hidden assumptions” are essential traits for any therapist to succeed, said Welch. “The willingness to be a client yourself, and to recognize the strength of human resilience” are also important, she said.

“The willingness to be a client yourself, and to recognize the strength of human resilience” are also important, she said.

All of these skills together enable therapists to help their clients strengthen their internal resources. “We want clients to use their own coping skills for the issues that come up in their lives,” Welch said. This skill can take years to build, so the ability to continuously grow and learn is key as well.

The ability to embrace and weather change is also crucial. “I cannot stress enough how important it is to be able to deal with ambiguity,” Welch said. “Often graduate programs in counseling are difficult for type-A perfectionists. You have to have a willingness to let go of what you think and become a student of the client’s work.”

What is the Job of a Therapist Like?

In clinical terms, a therapist “works directly with clients and provides some form of psychotherapy,” Cannon said. In more personal terms, the role of the therapist is to “hold space for the broken places of their clients and allow space for people to grow and change,” said Welch.

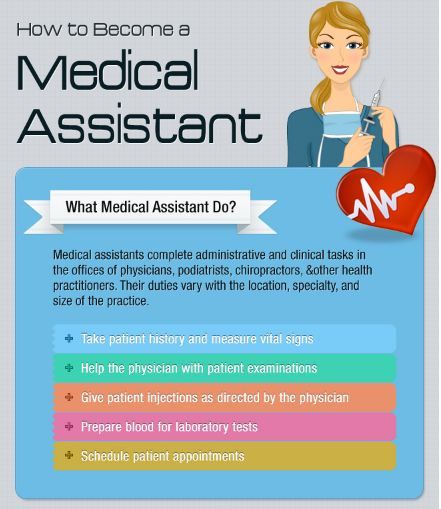

In terms of day-to-day responsibilities, the job can vary based on specialty. As a mental health counselor, Cannon works with clients one-on-one, with couples or families or in groups to provide direct mental health counseling services. The type of issues addressed can range from “life transitions to more significant and pervasive diagnosable mental health issues,” Cannon said.

Therapy can occur in:

- Community mental health agencies

- Hospitals

- Outpatient programs

- Private practice settings, such as in an office or via telehealth

- Schools

The job itself can look very different setting by setting, therapist by therapist, because “the needs of clients and the services provided to those clients can vary” so widely, Cannon said. Regardless of the setting, the overall focus of a clinical mental health counselor is to “utilize a specific set of counseling skills, driven by an empirically valid theoretical orientation and interventions, to empower client growth and well-being,” said Cannon.

Is Counseling a Good Career?

Both Cannon and Welch agree that being a therapist is a tremendously rewarding career in the helping professions. Welch acknowledges that helping clients work through issues can result in both small and large changes. The reward comes not from the size of the change that you help your client make but from helping clients “realize the possibility that things can change,” she said.

For Cannon, being a clinical mental health counselor is a highly rewarding career. “In my work, I have the capacity to empower and support people in meaningful ways every day of my life," she said.

Whether she's helping a client work through a difficult decision or significant life trauma, she feels she's making a difference in their lives. "I am hard-pressed to think of many other careers that center on such meaningful change and offer opportunities for such significant long-term impact,” Cannon said.

What Are Some of the Biggest Challenges of This Profession?

As you might imagine, while the rewards of being a therapist are great, there are some significant challenges as well. “As much as this career can be rewarding,” said Cannon, “it can also be emotionally and mentally taxing.”

“As much as this career can be rewarding,” said Cannon, “it can also be emotionally and mentally taxing.”

The biggest challenge, according to both Cannon and Welch, is the risk of burnout. “Therapists need to know their limits and ensure they are seeking good self-care” as part of their practice, said Cannon. The importance of self-care and personal therapy is often a part of therapist training, according to Welch.

What Advice Would You Give Someone Who is Considering This Profession?

Becoming a therapist is a big investment of time and energy. Because it can take years to achieve licensure and become qualified to establish a practice or work full-time in your chosen area, this is not a career field to enter into lightly.

This is also a field that can be very rewarding for some but is not the right fit for everyone. For that reason, it’s worth taking the time upfront to research the different options within the field of therapy to decide if this is the right career for you. “This is not a profession you can just try out to see if you like it,” Cannon said. Becoming a therapist takes some "front-end research, identity alignment and a commitment to the profession” before deciding if it's right for you, she said.

“This is not a profession you can just try out to see if you like it,” Cannon said. Becoming a therapist takes some "front-end research, identity alignment and a commitment to the profession” before deciding if it's right for you, she said.

Welch advocates the importance of becoming a client yourself because “it takes a great deal of vulnerability to sit in the client’s seat and reveal deep, often painful parts of your life to a stranger,” she said. “Once you respect that position, you realize how sacred this work is.” For that reason, she recommends having your own therapist because if the idea of that is off-putting to you, “reconsider why you want to do this.”

Welch believes that the key difference between a good therapist and a great one is as simple as having the willingness to seek therapy yourself.

A degree can change your life. Find the SNHU psychology or counseling program that can best help you meet your goals.

Marie Morganelli, PhD, is a freelance content writer and editor.

Definition of therapeutic relationship in CBT //Psychological newspaper

Chapter from the book by N. Kazantis, F. M. Dattilio, K.S. Dobson, Psychotherapy for Psychologists: Defining the Therapeutic Relationship in CBT:

Defining Therapeutic Relationships in Cognitive Behavioral Therapy

The therapeutic relationship is more than just a prerequisite for psychological intervention - it is essential to effective work. Since the client-therapist interaction takes place in the context of therapeutic processes and interventions, one could even say that everything within the session is related to relationships, not meaning that all therapeutic effects are associated with generally accepted factors (Kazantzis, Cronin, Norton, Lai , & Hofmann, 2015). However, a clear definition of the therapeutic relationship and its implications for CBT is lacking in our professional literature.

The therapeutic relationship can best be defined as an exchange between therapist and client who appears to share intimate thoughts, beliefs, and emotions to promote change. These relationships are characterized by a safe, open, nonjudgmental atmosphere that inspires trust and confidence. This definition differs from the therapeutic alliance in that an alliance is an alliance based on a therapeutic relationship and includes the coherence of strategies and exchanges that bring about change. The alliance is formed from the therapeutic relationship and is based on the knowledge and skills of the therapist, together with the provision of appropriate care. It combines the will and motivation of the client with the passion of the therapist to bring about change.

These relationships are characterized by a safe, open, nonjudgmental atmosphere that inspires trust and confidence. This definition differs from the therapeutic alliance in that an alliance is an alliance based on a therapeutic relationship and includes the coherence of strategies and exchanges that bring about change. The alliance is formed from the therapeutic relationship and is based on the knowledge and skills of the therapist, together with the provision of appropriate care. It combines the will and motivation of the client with the passion of the therapist to bring about change.

In the early years of the evolution of CBT, the field of psychology and psychotherapy was dominated by psychoanalytic thinking. Psychoanalysis emphasizes the therapeutic interaction between client and therapist as the mechanism by which change occurs. Aaron T. Beck, himself trained in psychoanalysis, later went on to do research that supported the idea that clients could learn to make their own intentional changes in the content and process of their thinking, and that this method of conducting psychotherapy could reduce emotional distress and improve functioning. client. Beck was also influenced by the work of Carl Rogers and his therapeutic triad of empathy, sincerity, and positive appreciation. Those of us who have witnessed Beck's work firsthand have noticed these influences. Beck is kind and empathetic towards his clients and uses his sense of humor appropriately to express appreciation and optimism for improvement in achievement and functioning. He also has a clear and strong belief in the client's ability to be a change agent.

client. Beck was also influenced by the work of Carl Rogers and his therapeutic triad of empathy, sincerity, and positive appreciation. Those of us who have witnessed Beck's work firsthand have noticed these influences. Beck is kind and empathetic towards his clients and uses his sense of humor appropriately to express appreciation and optimism for improvement in achievement and functioning. He also has a clear and strong belief in the client's ability to be a change agent.

In this chapter, we will define the main dimensions of the therapeutic relationship in CBT and reflect on some of the above qualities that are critical to the formation of an effective therapeutic relationship.

General elements

Any effective assessment or intervention in therapy depends on several components. First, clients need a sense of respect, value, and comfort so that they can show their vulnerability and share their personal experience, regardless of the emotional significance of their perspective. Sometimes we may encounter the client's anger in the very first session, which can make us become even better listeners as we see the client's pain and fear. This complex kind of interaction requires a calm, steady and sincere empathic response, which is not always easy to achieve.

Sometimes we may encounter the client's anger in the very first session, which can make us become even better listeners as we see the client's pain and fear. This complex kind of interaction requires a calm, steady and sincere empathic response, which is not always easy to achieve.

There are several common elements of the therapeutic relationship in CBT (see Table 1), including the therapist's counseling and listening skills, expressed empathy, and appropriate expressions of positive attitude (eg, encouragement and positive affirmation). Other common elements include seeking customer feedback, achieving congruence and authenticity, and the result of these efforts is customer trust, mutual respect, and positive interpersonal communication.

We often provide our clients with a relationship experience that is different from what they have experienced before. And this new experience gives them the opportunity to take a broader view of other people, relationships and the world. The more information we have about the client and her or his relationship history in the cognitive conceptualization of the case, the more effectively we can connect these common elements in order to begin the process of belief change. We often help our clients to look at the world from a new point of view, opening doors for them to new opportunities.

The more information we have about the client and her or his relationship history in the cognitive conceptualization of the case, the more effectively we can connect these common elements in order to begin the process of belief change. We often help our clients to look at the world from a new point of view, opening doors for them to new opportunities.

A great example of this relationship process is a story told by one of our senior colleagues about an experience he had a few years ago. One day, while he was sitting in his office, he received a call from a former patient whom he treated 30 years ago. The caller said that he had just received a promotion to a senior position in his company and was cleaning his desk in anticipation of the move. He apparently stumbled upon our colleague's business card and decided to take a chance and call him: "I don't know if you remember me, but you treated me decades ago when I was in college."

Not surprisingly, the therapist did not remember him, but tried to be polite and sincere with whoever called. The man spoke quite forcefully about his memories when he was a student in college and how he approached our colleague because he was suicidal. "I was very close to committing suicide in those days and you really helped me change my life." The caller then went on to describe how well he had settled in life and said that he was now married with several children and had achieved significant success in the business world. When our colleague selfishly asked, "Well, could you tell me a little about what I did that helped you make such a monumental change?" The man thought for a minute and replied, "Oh, I don't know, really, you were just yourself." Many of our clients appreciate our sincerity, honesty and communication. However, this value means more than just being a "good person" as a therapist: our way of relating can radically change our clients' deepest beliefs about other people and about the world.

The man spoke quite forcefully about his memories when he was a student in college and how he approached our colleague because he was suicidal. "I was very close to committing suicide in those days and you really helped me change my life." The caller then went on to describe how well he had settled in life and said that he was now married with several children and had achieved significant success in the business world. When our colleague selfishly asked, "Well, could you tell me a little about what I did that helped you make such a monumental change?" The man thought for a minute and replied, "Oh, I don't know, really, you were just yourself." Many of our clients appreciate our sincerity, honesty and communication. However, this value means more than just being a "good person" as a therapist: our way of relating can radically change our clients' deepest beliefs about other people and about the world.

The second major common element in the therapeutic relationship is the working alliance. This concept has a long history in the psychotherapeutic literature, but Bordin's (1979) definition has been widely accepted and empirically validated. Bordin suggested that the alliance included a relational "bond" and emphasized mutual respect and sympathy, as well as an open statement of "agreements" regarding session priorities and treatment in general. Any session that does not deal with the issues that led the client into therapy or what worries them most is a bad session. Relationships become strained if there is a mismatch in priorities, if the therapist's ideas dominate those of the client, or if the client insists on an agenda for the session that the therapist does not share. Similarly, problems can arise if the stated objectives of the session and the actual work of the session are inconsistent.

This concept has a long history in the psychotherapeutic literature, but Bordin's (1979) definition has been widely accepted and empirically validated. Bordin suggested that the alliance included a relational "bond" and emphasized mutual respect and sympathy, as well as an open statement of "agreements" regarding session priorities and treatment in general. Any session that does not deal with the issues that led the client into therapy or what worries them most is a bad session. Relationships become strained if there is a mismatch in priorities, if the therapist's ideas dominate those of the client, or if the client insists on an agenda for the session that the therapist does not share. Similarly, problems can arise if the stated objectives of the session and the actual work of the session are inconsistent.

The early therapeutic interaction described in Johan's case presented in chapter 1 illustrates the potential difficulties of the therapeutic alliance. In this case, the therapist diligently went through the appropriate informed consent steps and tried to get more specific information about the difficulties that brought Johan into therapy, while Johan tried to better understand the person he was seeing for the first time in his life. Johan's "Not Quite" response to the therapist's question, "Would you like to start by telling me what brings you here today?" clearly demonstrates that his agenda for the session was different from that of the therapist. This response also showed much of the anxiety Johan felt in the world, the difficulty in understanding himself in the context of his relationships with other people, and a persistent pattern of suspicion when considering other people's motives. The therapist's thoughtful response to Johan was at odds with the responses he usually received from those around him, and as it turned out, this was also different from the responses of his previous therapists who "give up". Johan also acted inappropriately in the session when he angrily noted the association between prostitution and paid therapy; this hint finally showed Johan's ideas about the "falseness, insincerity and dishonesty of the motives of other people."

Johan's "Not Quite" response to the therapist's question, "Would you like to start by telling me what brings you here today?" clearly demonstrates that his agenda for the session was different from that of the therapist. This response also showed much of the anxiety Johan felt in the world, the difficulty in understanding himself in the context of his relationships with other people, and a persistent pattern of suspicion when considering other people's motives. The therapist's thoughtful response to Johan was at odds with the responses he usually received from those around him, and as it turned out, this was also different from the responses of his previous therapists who "give up". Johan also acted inappropriately in the session when he angrily noted the association between prostitution and paid therapy; this hint finally showed Johan's ideas about the "falseness, insincerity and dishonesty of the motives of other people."

Table 1. Summary of therapist-specific activities and expected outcome of general and CBT-specific elements of the therapeutic relationship

Effective therapists must learn not to take personal credit for their clients' indecent or rude behavior, but instead must work with these clients to find productive uses for what they share. In the first session with Johan, the therapist made the wise decision to spend the session sharing values, which helped change the tone of the interaction to one of mutual exchange and allowed Johan to realize that his own values of "honesty, integrity, and consideration for others" were shared by the psychology profession, even if specialists could express these values in different ways. This discussion allowed the process of reaching an understanding with Johan and his concerns to begin. It turned out that Johan not only believed that he should be careful with other people, but when they mistreated him (and paradoxically, this was often caused by his own behavior towards others), he viewed these actions as a sign that they need to be "put in place." The therapist elaborated, "Now, if it seemed to you that I would end up judging and rejecting you, then it's not surprising that you would meet this with some hostility - this is certainly one way to test the waters."

In the first session with Johan, the therapist made the wise decision to spend the session sharing values, which helped change the tone of the interaction to one of mutual exchange and allowed Johan to realize that his own values of "honesty, integrity, and consideration for others" were shared by the psychology profession, even if specialists could express these values in different ways. This discussion allowed the process of reaching an understanding with Johan and his concerns to begin. It turned out that Johan not only believed that he should be careful with other people, but when they mistreated him (and paradoxically, this was often caused by his own behavior towards others), he viewed these actions as a sign that they need to be "put in place." The therapist elaborated, "Now, if it seemed to you that I would end up judging and rejecting you, then it's not surprising that you would meet this with some hostility - this is certainly one way to test the waters."

Other common elements of the therapeutic relationship include the therapist's ability to work with the client to create session structure, to follow that structure at an appropriate pace, and to seek feedback before, during, and after interventions and sessions.

Specific elements of KPT

The three main elements of CBT are cooperation, empiricism, and Socratic dialogue. These elements are constantly emphasized throughout this text, especially in the cases described in subsequent chapters.

With respect to the first element, cooperation, CBT invites clients to take an active role in the therapeutic process, while the therapist takes on the role of collaborator or guide - a person who can assist the client's progress towards his or her desired goal(s). This emphasis on the client as the agent of change is very different from other therapies in which the client may take a more passive role. CBT prioritizes active participation, which is also different from approaches where the therapist takes a passive role, acting as the so-imposed "reflective tool for change", or in therapies where the therapist can tell or advise the client what to do. (Kazantzis, Freeman, Fruzetti, Persons, & Smucker, 2013). For example, we don't usually talk about "consenting" to treatment. Rather, we will think of "commitment" to a treatment plan that has been co-created, but we can also consider "commitment" as a final term that reflects a mutual therapeutic partnership. In fact, the term "collaboration" in CBT means "working together" (Beck,1995; Dattilio & Hanna, 2012; Tee & Kazantzis, 2011), and this encourages the client's active participation in the therapeutic exchange as a special function of the therapeutic relationship in CBT. While these relationships ideally reflect a balance of contributions made by the participants in therapy, there are times when the therapist can take the lead, as well as times when the client is asked to take the lead, either in or between sessions. We will pay special attention to cooperation in later chapters, but for now, it is important to highlight it as the first, CBT-specific element of the therapeutic relationship. We invite you to participate in the second self-reflection exercise about your own style of therapy at the end of the chapter.

Rather, we will think of "commitment" to a treatment plan that has been co-created, but we can also consider "commitment" as a final term that reflects a mutual therapeutic partnership. In fact, the term "collaboration" in CBT means "working together" (Beck,1995; Dattilio & Hanna, 2012; Tee & Kazantzis, 2011), and this encourages the client's active participation in the therapeutic exchange as a special function of the therapeutic relationship in CBT. While these relationships ideally reflect a balance of contributions made by the participants in therapy, there are times when the therapist can take the lead, as well as times when the client is asked to take the lead, either in or between sessions. We will pay special attention to cooperation in later chapters, but for now, it is important to highlight it as the first, CBT-specific element of the therapeutic relationship. We invite you to participate in the second self-reflection exercise about your own style of therapy at the end of the chapter.

The second element of relationship CBT, empiricism, describes how we help the client develop a more "scientific" way of evaluating his or her experience. In contrast to how clients can sometimes come to therapy heavily influenced by various cognitions and emotions, we help the client look at these experiences as indirect measurements of events occurring in their environment, and we pay special attention to explaining how to evaluate and deal with these events. It is important to remember that a client's emotions are valuable indicators of their initial distress as well as their progress in therapy. Just as changes in clients' thought processes are an important aspect of CBT, changes in their emotional experiences are also important. Indeed, focusing on emotions helps CBT therapists tailor interventions for each client and keep them engaged in therapy, endure difficult times, and see adversity as an opportunity for growth. Using the client's experience as a measure of the effectiveness of interventions helps them become inquisitive, exploratory, and reinforces them in asking difficult questions that may call into question the very fabric of their existence.

Socratic dialogue, the third element of CBT, involves a range of counseling skills such as questioning, summarizing, empathic listening, and enabling the client to identify and resolve conflicting points of view. If clients can explore their own psychological processes in the same way that a therapist does in a session, then they can develop the ability to ask questions and increase distance and observe their subjective experience. If the therapist draws on the Socratic Dialogue as a way to discover new ideas, then the client may develop a greater sense of ownership of their therapy. Chapter 5 details the use of Socratic dialogue in guided opening.

Cognition and emotions of the therapist

The early interaction described in Johan's case illustrates how a CBT therapist can communicate his personal values as a professional, and to some extent, those values that are generally important as a person. This communication serves as part of the process of collaborative treatment. A therapist who has the personal values of attention, kindness, and thoughtfulness will most likely take the extra effort to remember details about the lives of each of their clients, and then bring those details into the therapy session when appropriate. This unique value of each client can be important for clients with longstanding relational problems, otherwise they may feel insecure and vulnerable to one-way communication. Of course, the extent to which the therapist's attention to the client's privacy is limited by boundaries that are important for ethical reasons (see Chapter 12 on ethical and safety issues). Some therapists may use appropriate self-disclosure to create a different relational experience for the client. In many ways, developing and maintaining a focus on the client's problems requires great strength and resilience.

A therapist who has the personal values of attention, kindness, and thoughtfulness will most likely take the extra effort to remember details about the lives of each of their clients, and then bring those details into the therapy session when appropriate. This unique value of each client can be important for clients with longstanding relational problems, otherwise they may feel insecure and vulnerable to one-way communication. Of course, the extent to which the therapist's attention to the client's privacy is limited by boundaries that are important for ethical reasons (see Chapter 12 on ethical and safety issues). Some therapists may use appropriate self-disclosure to create a different relational experience for the client. In many ways, developing and maintaining a focus on the client's problems requires great strength and resilience.

In order to keep the focus of therapy on the client, we advocate conceptualizing the therapist's belief system and focusing on activating the therapist's beliefs in training and supervision. It is obvious that the emotions and physiological manifestations that the therapist exhibits in sessions are often an additional useful indicator. The items in Table 2 show the association of certain positive and negative core beliefs of the therapist about self and others with schemas and values.

It is obvious that the emotions and physiological manifestations that the therapist exhibits in sessions are often an additional useful indicator. The items in Table 2 show the association of certain positive and negative core beliefs of the therapist about self and others with schemas and values.

Table 2. Illustration of the relationship between values, schemas, and core beliefs in the therapist's belief system

We encourage our readers to use two useful assumptions when they are trying to maintain nonjudgmental acceptance with a client. First, we assume that psychotherapy involves a relationship that is limited primarily to discussions of the client, his world, his problems, and his ability to cope with life. While there are differing views as to the extent to which therapist self-disclosure is useful and important in therapy, disclosure of personal information about the therapist is not always beneficial. In fact, in some cases it may even be counter-therapeutic, depending on the timing and manner in which this information is provided.

First self-reflection exercise

We invite you to consider some specific assumptions about forming a therapeutic relationship with your clients:

- “If I have negative thoughts and/or feelings about a client, he or she is likely to notice this reaction and respond negatively”;

- "I can serve as ... the world, as a kind, patient and accepting person who appreciates every person sitting in this room with me";

- "Accepting clients means not judging or trying to change them, but it is my duty to support them if they want to change their views or behavior."

Second, the therapist's style ensures attentiveness when he or she takes into account his or her cognitions and emotions. What is normal for one therapist may be uncomfortable for another. Each therapist has different strengths and weaknesses, and the ability to develop general skills such as empathic understanding. Many therapists who study the psychotherapy model will try to adopt the style of the lead figure or advocate. While this strategy may be initially beneficial, we encourage practitioners to develop their own self-understanding and their own most comfortable style, as this allows them to better focus on needs

While this strategy may be initially beneficial, we encourage practitioners to develop their own self-understanding and their own most comfortable style, as this allows them to better focus on needs

In Chapter 1, we challenged you to identify your own values. We now invite you to relate these values to your way of working in therapy. For some therapists, the value of "doing things right" may come through in a well-structured approach, while others will prefer fluidity and flexibility. For other therapists, being out of control and out of control of others, showing warmth, generosity, and a supportive manner of interaction can be crucial in the therapeutic relationship. Again, similar values can lead therapists to adopt different interpersonal styles in working with clients. These values may be expressed by some in a calm manner, while other therapists may prefer to be more active.

Therapists who choose to be more thoughtful, kind, tolerant, forgiving, determined, disciplined, reflective, efficient, patient, or humorous would probably display such different meanings of these concepts, depending on who identified them. Obviously, these terms do not have "universal" definitions. We invite you to reflect on what makes your therapy practice unique in your own style with your particular workload. This process accepts that everyone practices CBT differently and what we call today may change in a year or 20 years.

Obviously, these terms do not have "universal" definitions. We invite you to reflect on what makes your therapy practice unique in your own style with your particular workload. This process accepts that everyone practices CBT differently and what we call today may change in a year or 20 years.

Second self-reflection exercise

We invite you to take five minutes to reflect on which end of the continuum you prefer to work from and see how your values manifest in practice. For example, you might note on the "Instructive" continuum how flexible or structured your session agenda is, and consider what values underlie that style. The purpose of this exercise is to connect your values with your therapy style, not to judge or judge.

Instructional: Flexible - structured

Operational: Planned - Spontaneous

Emotional expression: Low - high

Active participation: Distant - expressed

Spotlight: Focused - Wide

Customize according to customer needs

Just as every client is unique, so is every therapeutic relationship. Our goal is to tailor our CBT interventions to the strengths and abilities of each of our clients. With current knowledge and research methods, we are limited to observing behavior during a session. A client's smile or yawn in response to a naked smile or yawn may lead to the hypothesis of mirror neuron activation, but ultimately we must depend on our understanding of the client's session behavior to understand his or her daily interpersonal style.

Our goal is to tailor our CBT interventions to the strengths and abilities of each of our clients. With current knowledge and research methods, we are limited to observing behavior during a session. A client's smile or yawn in response to a naked smile or yawn may lead to the hypothesis of mirror neuron activation, but ultimately we must depend on our understanding of the client's session behavior to understand his or her daily interpersonal style.

Many of the CBT techniques involve clients in the process of identifying thoughts and emotions, which involves understanding their own emotional experiences and being able to recognize the emotions of others. CBT therapists need to closely monitor and accurately read emotion expression in a session or avoidance of emotions, and understand relationship difficulties described by clients in other areas of life.

(Klumpp, Fitzgerald, Angstadt, Post, & Phan, 2014; Mayer, Salovey, & Caruso, 2008; Samoilov & Goldfried, 2000; Siegle, Carter, & Thase,

2006). So, in a very real sense, we help our clients develop emotional intelligence. (Hezel & McNally, 2014; Muris, Mayer, Vermeulen, & Hiemstra, 2007; Spek, Nyklíc̆ek, Cuipers, & Pop, 2008). CBT also involves dealing with the present moment, which requires a certain amount of executive function to keep track of aspects of experience during communication and deliberately discourage the use of non-working strategies from the past. (Johnco, Wuthrich, & Rapee, 2014; Mohlman, 2013; Snyder, 2013).

So, in a very real sense, we help our clients develop emotional intelligence. (Hezel & McNally, 2014; Muris, Mayer, Vermeulen, & Hiemstra, 2007; Spek, Nyklíc̆ek, Cuipers, & Pop, 2008). CBT also involves dealing with the present moment, which requires a certain amount of executive function to keep track of aspects of experience during communication and deliberately discourage the use of non-working strategies from the past. (Johnco, Wuthrich, & Rapee, 2014; Mohlman, 2013; Snyder, 2013).

Rice. 1. A brief description of the client attributes that are required when using CBT.

CBT invites clients to monitor and analyze their thought processes, such as selective attention, memory bias, and other potentially dysfunctional ways in which their experience is shaped. Similarly, identifying and evaluating beliefs about thoughts and thought processes (i.e., meta-cognition) requires certain aspects of intellectual functioning, such as receptive and expressive language, and the ability to think abstractly (Sasso & Strunk, 2013; Waters, Mogg , & Bradley, 2012). Clients with low intelligence, literacy issues, fetal alcohol syndrome, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, psychosis, or a history of traumatic brain injury or excessive alcohol or drug use, or who may be experiencing the onset of dementia, will need special attention. sensitivity of the therapist and skills in the use of CBT. (See Fig. 3).

Clients with low intelligence, literacy issues, fetal alcohol syndrome, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, psychosis, or a history of traumatic brain injury or excessive alcohol or drug use, or who may be experiencing the onset of dementia, will need special attention. sensitivity of the therapist and skills in the use of CBT. (See Fig. 3).

Cognitive Case Conceptualization and Relationship Adaptation

Although the competent use of CBT depends on learning and effective use of fundamental counseling skills, these elements require skilled and responsive adaptation for each client in each session. What may be perceived as empathic and supportive by one client may be construed as patronizing and demeaning by another. Each therapist's behavior is viewed through a set of clients' values, beliefs, and assumptions. Therefore, CBT therapists must constantly walk a fine and ever-changing line to ensure that their skills are appropriately adapted and of benefit to their clients. In the next chapter, we will discuss how cognitive conceptualization serves as the basis for adapting our general therapeutic relationship skills to each client in each session.

In the next chapter, we will discuss how cognitive conceptualization serves as the basis for adapting our general therapeutic relationship skills to each client in each session.

Source: Nikolaos Kazantzis, Frank M. Dattilio, and Keith S. Dobson: PSYCHOTHERAPY FOR PSYCHOLOGISTS: Defining the therapeutic relationship in CBT. Guilford press: UK.: 8-19p. - 2017

Authors: Nikolaos Kazantzis, Frank M. Dattilio, Keith S. Dobson. Translation: Billig-Gorbunova E. A., member of the Association for Cognitive Behavioral Psychotherapy (ACP), head of the ACP department in Germany

26 - 29April in St. Petersburg, May 4, Moscow will host the IV International Congress of the Association of Cognitive-Behavioral Psychotherapy

Program | Moscow Gestalt Institute

Preparation Structure Basic Course

Certification Requirements >>

Requirements for Certification Cases

Requirements for Accreditation >>

Recommendations for writing a review of the Certificates >>

First stage - 1. 5 years (180 hours) - "Fundamentals of Gestalt Therapy" - getting to know the method, teaching the basic concepts and principles of the Gestalt approach, personal therapeutic experience in a group, working with an individual therapist, participating in an intensive in client position.

5 years (180 hours) - "Fundamentals of Gestalt Therapy" - getting to know the method, teaching the basic concepts and principles of the Gestalt approach, personal therapeutic experience in a group, working with an individual therapist, participating in an intensive in client position.

Second stage — 2.5 years (420 hours) — Theory and Practice of Gestalt Therapy — professional training for Gestalt therapists, culminating in certification (see Certification Requirements). Includes theoretical training, personal therapy, supervision, work in small groups, participation in intensives (in client and therapeutic positions), in conferences, choosing and completing a specialization (or attending a special course), as well as starting one's own practice under supervision. The specialization ends with a graduation event, which is supervised by one of the leading MGI trainers. Specializations and special courses are held in parallel with the main basic program, and can also be taken after its completion.

The topics of the basic course include 1 and 2 steps, defined in 4 large theoretical blocks: 1) acquaintance with the theoretical and philosophical issues of Gestalt therapy, 2) methodology of practice, 3) clinical and other specific issues of Gestalt therapy, 4) supervision. The logic of placement of individual topics in the learning process depends on the head of the program and the dynamics of the group. Those who want to continue their education at the 2nd stage apply to the MGI or the program manager. That. the 2nd stage group can be an association of participants from different 1st stage groups motivated for vocational training. For a certain number of participants, education will be end-to-end.

If the dates of the basic course and other events coincide, the participant may not pay for participation in the latter, and the head of the event must ensure that the participant can work out the pass.

Stage 2 ends with a supervisory certification session in the group (the so-called internal certification) with the invitation of an independent supervisor - a trainer who has releases of his own programs and (or) a therapist and in the presence of the head (heads) of the program.

After fulfilling the certification requirements (see "Certification Requirements"), the program participant submits a record book and all materials (description of cases with a review, confirmation of hours of personal therapy, supervision, intensives, accompanied by the recommendation of the head of the program to the educational unit and enrolls for open certification. Open certification is carried out by the MHI Certification Commission, the composition of which is formed for a period of one year and is approved by the MHI Professional Council. The Certification Commission works with a group consisting of participants from different programs who have prepared materials by this deadline. Open certification dates are indicated on the MHI website. Certification can be complete , conditional (indicating the conditions necessary for successful completion), a retake may be recommended, i.e., a re-demonstration of work at other times. In some cases, in particular in violation of ethical standards, re-certification may be denied.

After the materials are considered by the commission and the student demonstrates work at an open certification recognized as corresponding to the professional level, he is issued an MHI certificate on the successful completion of a training program in the field of the Gestalt approach with the qualification of a Gestalt therapist.

To recognize a graduate of the program as a therapist by the professional community, it is necessary to accredit him for a certain period (3 years), after which the question of confirming the status of a therapist again arises.

The accreditation procedure requires:

1 - a certificate of completion of the program,

2 - recommendation of the program manager, supervisor and two therapists who have seen the work and confirm its professional level,

3 - a description of the experience of their own practice (individual clients, groups, families, organizations), an indication of participation in intensives (in which, and in what role), in supervisory and thematic groups, in conferences, holding workshops, speeches, articles, etc.

4 — application to a public organization of the society of practicing psychologists "Gestalt approach" or to the regional representative office of the society for accreditation in the professional community as a therapist.

The third stage - 360 hours - is focused on the training of supervisors, teachers of Gestalt therapy, as well as an in-depth study of the theory and methodology of practice. Level 3 programs exist at MGI at the moment in the standard version. A separate issue of the bulletin will be devoted to their description. There are also author's supervisory improvement programs in Gestalt therapy.

TRAINING PROGRAM FOR GESTALT THERAPISTS

Basic course

Training standards aligned with EAGT standards

MAIN TOPICS:

Theoretical introduction, historical roots, founders of Gestalt therapy, schools of Gestalt therapy, authors, modern Gestalt approach, literature. Basic concepts and principles of Gestalt therapy (field - organism-environment, phenomenological approach in Gestalt therapy, dialogue, awareness, figure and background, contact, contact boundary, cycle of experience, creative adaptation).

2. Field theory in Gestalt therapy. Theory and functions of self. The dynamics of self. Resistance. Loss of ego function, main types of interruption of contact.

3. Creative methods in Gestalt therapy. Work with the internal phenomenology of the client. The theory of paradoxical change. Working with polarities. Art therapy, work with drawing, metaphors, dreams. Languages of Gestalt Therapy. contact modalities. therapeutic metaphors.

4. Gestalt and body-oriented approach. Alienation and awakening of corporality. The dynamics of bodily experiences in personal history.

5. Gestalt philosophy and practice methodology. Psychotherapeutic worldview and psychotherapeutic thinking. Therapeutic position and professional self-awareness of a Gestalt therapist. Therapeutic relationship, transference and countertransference. The main strategies of the Gestalt therapist. Work at the contact boundary. Process-analysis of the therapeutic session.

6. Theories of development. Child development. Gestalt therapy with children and parents. Family Gestalt Therapy.

Child development. Gestalt therapy with children and parents. Family Gestalt Therapy.

7. Crisis and trauma.

8. Gestalt therapy in clinical practice. Health and disease. Principles of clinical diagnostics in Gestalt therapy. Dynamic concept of personality in Gestalt therapy. Analysis of early violations. Gestalt therapist strategies in working with endogenous disorders, borderline disorders, addictions, neuroses and psychosomatic disorders.

9. Gestalt approach to working with groups. Field phenomena in group dynamics. Gestalt and systems approach. Work with pairs, small systems. therapeutic community. Organizational Gestalt Consulting.

10. Principles and applications of ethics.

The listed topics reflect the content of the training and do not correspond to the list of thematic sessions. The logic and focus of the presentation is determined by the program manager and depends on the dynamics and composition of a particular group.

The program includes 20 sessions - 14 thematic, 2 therapeutic and 4 supervisory.

CERTIFICATION REQUIREMENTS:

1. Theoretical training — 700-810 hours (1+2 level), including

- 14 thematic sessions - 420 hours

- specialization or special course of choice - 120-180 hours

(in the absence of specializations in certain regions, they can be replaced by author's thematic seminars)

- lecture courses in the absence of them in basic education (psychiatry for psychologists and teachers, personality theories and psychological developmental theories for doctors) - 60 hours

- intensive theoretical training (hours of lectures and classes in study groups by levels) −100-150 hours.

2. Personal therapy - 240 hours, includes a minimum of 60 hours of individual therapy (recommended at least 50 hours of work with one therapist, possibly with two, but not at the same time, hours of intensive therapy are also taken into account), 60 hours of group therapy sessions, included to the program, intensive process groups - 20 hours, small therapeutic groups parallel to the program - 100 hours.

3. Supervision — 150 hours, including 120 hours of group supervision included in the program and 30 hours of individual supervision (supervision at intensive courses, regular external dynamic supervision of work with real clients when preparing cases (it is recommended to apply for supervision 1 time in 4 -5 meetings with a client), individual face-to-face supervision in small groups for 3-4 years of study - with an invited external supervisor).

4. The workshop includes 400 hours, including: (A) 200 hours of work in small groups - "triples". Of these, 50 hours are a workshop for 1-2 years of study and 150 hours under supervision for 3-4 years of study. Troika meets every 1-2 weeks and invites a supervisor to every fifth meeting. (B) 200 hours of consultative and therapeutic work with clients, families, groups, organizations, as well as the use of the Gestalt approach in the practice of their professional activities during the second stage of study, its brief description.

5. Writing a written paper on the clinical and theoretical application of Gestalt therapy in your professional practice - a description of 3 cases of continuous work, one of them with regular remote supervision.

Case description requirements for certification:

1 case - at least 25 meetings,

2 case - at least 10 meetings,

3 case - at least 6 meetings. The format of the 3rd case is at the discretion of the program manager. This may be the case of working with a child, or a teenager, or a family, or a group, or an organization. This may be a description of a case of intensive work.

It is recommended to start conducting cases for describing work with clients for certification from the last year of the program, always under supervision. In all cases, the contact with the supervisor must be described.

6. Diploma of higher education in psychology or related specialties.

7. Participation in at least two intensives (preferably three), in the position of the client and in the position of the therapist. Client intensive (one) can be replaced by a shuttle. Participation in at least one, preferably two conferences in the field of the Gestalt approach, at least 50 hours of acquaintance with the theory and practice of Gestalt through lectures, workshops, participation in round tables, etc.

Client intensive (one) can be replaced by a shuttle. Participation in at least one, preferably two conferences in the field of the Gestalt approach, at least 50 hours of acquaintance with the theory and practice of Gestalt through lectures, workshops, participation in round tables, etc.

8. Program Manager's recommendation

9. Demonstration of work at the certification session that ends the program in the presence of an invited independent supervisor.

10. In case of non-certification of a program participant, a corresponding entry is made in his account book. Re-certification is possible after 1 year.

MGI FINAL STANDARDS - February 2007.

1) 700-810 hours of theory and methodology

2) 240 hours of personal therapy

3) 150 hours of supervision

4) 400 hours of workshop

5) 50 hours of conference

Total: 1540 - 1650 hours.

EAGT Training Standards - minimum 1450 hours

1) 600 hours of theory and methodology

2) 250 hours of personal therapy

3) 150 hours of supervision

4) 400 hours of clinical practice by preference

.

The MHI educational standards exceed the EAGT standards in terms of theory and methodology hours (due to taking into account intensive teaching hours).

EVALUATION CRITERIA FOR THE FINAL CERTIFICATION SESSION IN GESTALT THERAPY UNDER THE MHI PROGRAM:

1. Certification is the final part of the evaluation of training in Gestalt therapy. In addition, the final assessment includes the assessment of the program manager, assessment of written works (case descriptions and essays).

2. During the certification session

A) the behavior of the therapist during the simulation session, which can be directly observed

B) Therapist's reasoning during the discussion after the simulation session.

Both components are of equal importance for the final grade.

3. Criteria according to which the certification session is not counted, since the listed phenomena indicate the loss of the therapeutic position:

A) the therapist ignores the phenomenology of the client;

B) the therapist uses the client to relieve his tension;

C) The therapist is unable to discuss his work.

4. Criteria for a session to be counted as a Gestalt session, as these listed phenomena are indicative of supporting the client's awareness and creative adjustment:

- during the therapist's work:

A) Attentive and sensitive to the client's phenomenology here and now ;

B) maintains the integrity of the client's experience, works with figure/ground dynamics;

C) maintains a dialogical relationship with the client;

D) correlates his actions with the sequence of the cycle of experience.

- during the discussion, the therapist:

E) can use Gestalt theory to diagnose the client;

E) can describe his choices and strategies in terms of Gestalt therapy.