What causes your mind to go blank

What to do when your mind goes blank

Does your mind ever go blank in stressful situation, such as during an exam, an interview, or giving a speech?

Having a brain freeze can happen to anyone. “The problem doesn’t just affect those of us who generally suffer from anxiety. Virtually all of us are vulnerable to similar failures, finding it harder to recall key words at the right time and almost impossible to focus on the task at hand,” says Time.com.

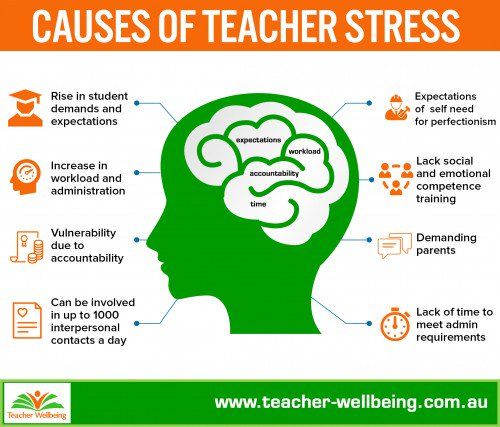

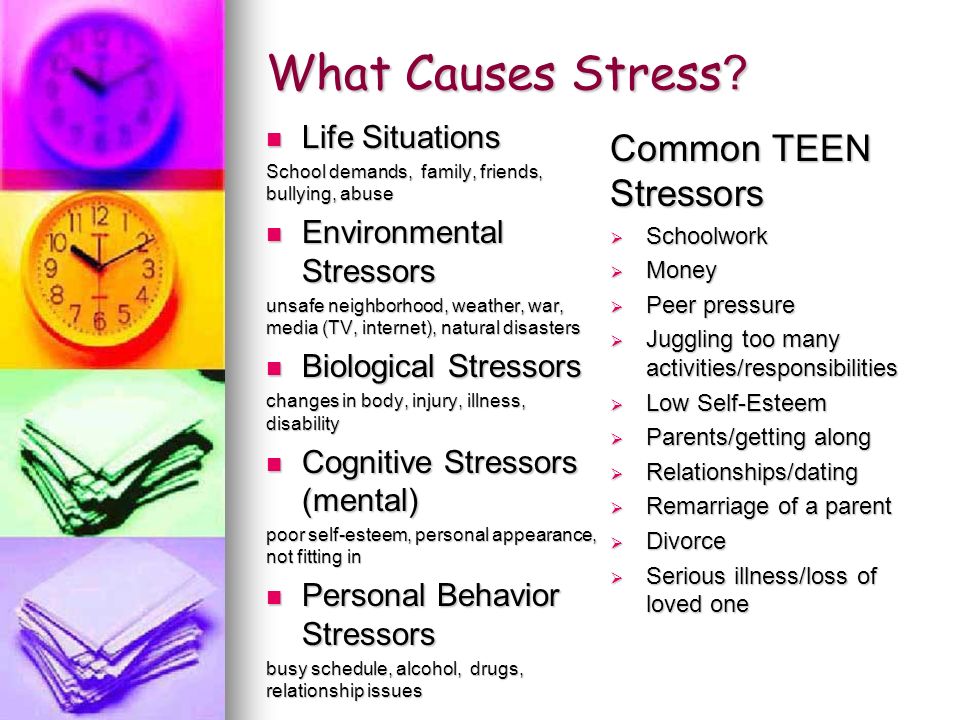

This frustrating reaction to pressure is actually caused by anxiety interfering with your memory and performance.

So, what is the science behind the reaction, and how can you deal with it?

It’s due to something called the ‘fight or flight’ response. The feeling of your mind going blank under stress happens when hormones, such as cortisol, flood our systems. These hormones “invade the brain’s pre-frontal cortex and the hippocampus, disrupting neuronal activity and our normal brain patterns”, explain olwcation.

com. As a result, our methods for factual retrieval and recall methods are disrupted.

Our ancestors needed this reaction in the body to help them fight predators or escape dangerous situations. “Taking time to consider your options is not advisable while being chased by a tiger or facing enemy fire,” explain Time.com. It’s your instincts taking over and other parts of your brain, that could get in the way of survival, being made to stand aside and make room. In stressful situations “the brain tends to shut off the cortical networks involved in creativity, contemplation, planning and thinking abstractly”. Sounds good for the escaping-wild-tigers scenario but not great news if you’re in the middle of making a speech or sitting down to an exam.

This shift in brain focus causes you to forget the information you need to take that test or make your speech, which in turn causes even more anxiety, turning the situation into a vicious circle which can be hard to escape.

There are steps you can take to help prevent this from happening, and ways to deal with the situation if your mind does go blank at an inopportune moment.

Prepare

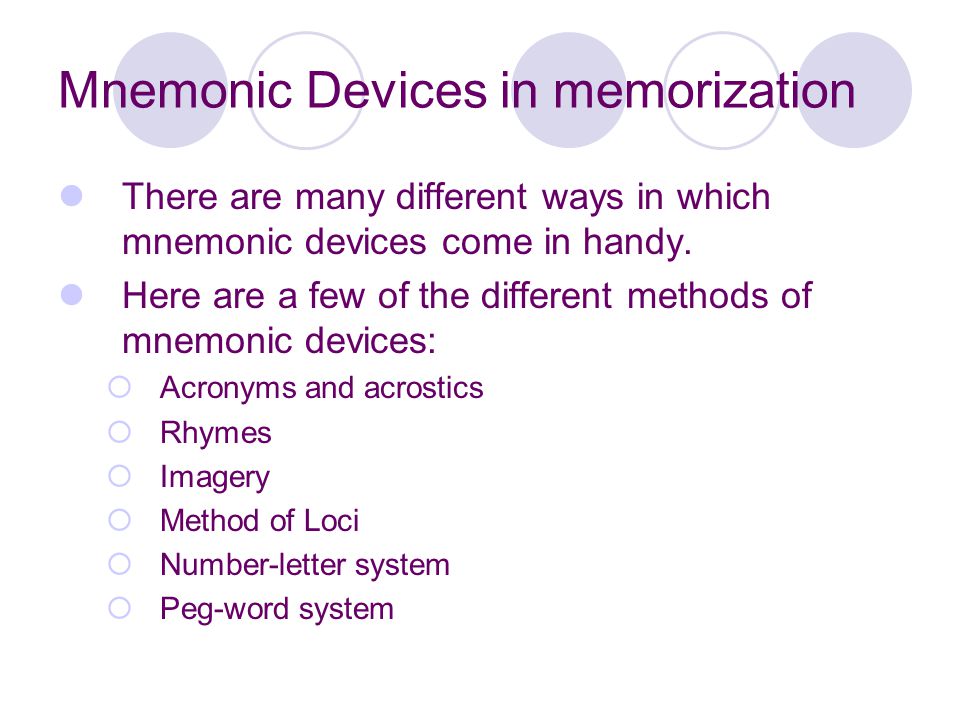

Reduce the need for worry by being as prepared as possible – practice your speech until you can say it without thinking, revise, do mock interview questions and whatever else you need to ensure your body can go through the motions for you if your mind does start to go blank.

“The reason the armed forces train new recruits in stressful situations that simulate active combat scenarios is to ensure ‘cold cognition’ during future engagements. The more a person experiences a particular situation, the less likely he or she is to perceive such a situation as threatening,” say theconversation.com.

Use relaxation techniques

The best way to combat your brain’s reaction to anxiety is arguably by preventing the anxiety in the first place. There are many ways to do this, such as meditation, breathing exercises and listening to calming music. Find out what works best for you and use it next time you need to enter a stressful situation.

Find out what works best for you and use it next time you need to enter a stressful situation.

Re-trace your steps

If you’re giving a speech or answering an interview question, repeat your previous point to give you momentum to carry on. It also helps to have your notes in front of you.

Say or write something

The longer you stay silent or stop writing, the harder it will be to carry on as your anxiety grows. If you’re giving a speech, say anything relevant, try using a ‘trigger sentence’ that you can repeat if you run out of things to say, such as ‘the main thing to remember about xyz is’ or if you’re writing, do the same and your memory will likely kick into gear.

And of course, there is nothing at all wrong with letting people know that your mind has momentarily gone blank. Remember than panicking and worrying about the potentially humiliating consequences of having nothing to say in that moment will not help your thoughts come.

Recent Posts

- How to run great meetings – online or in person

- The best apps for returning to study

- Improving your soft skills – how to manage your time

- Need a promotion? Here are the Dos and Don’ts

- SEO for newbies: The basics

- Improving your soft skills: five ways to be a better communicator

- How do internet celebrities make money?

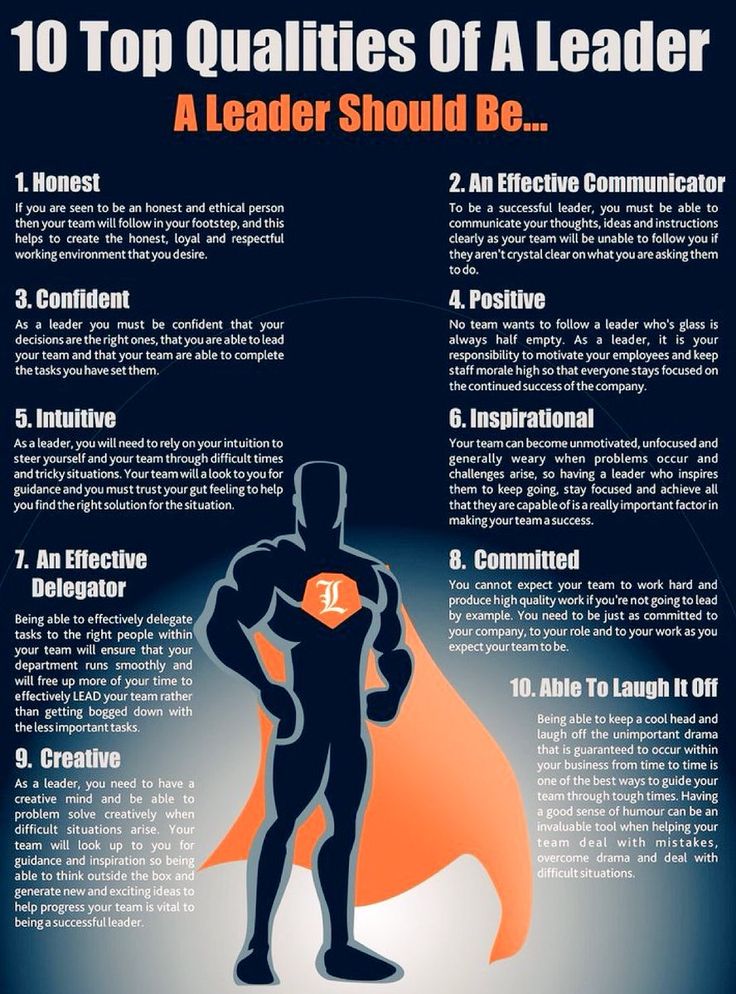

- Five factors that make a good boss

- Four valuable benefits of offering work experience (and how to make the most of it)

- The Power of Persuasion – Tips for Persuasive Writing

Categories

- Alumni

- News

Archives

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

What causes our mind to blank out or wander? It's the 'local sleep' in brains, study suggests

Bengaluru: A new study on people performing a set of boring tasks has revealed the mechanisms under which the mind starts to wander and blank out, what the nature of consequences of those lapses in attention could be, and how they are triggered.

The researchers identify localised slow waves — patterns of brain activity similar to when we are about to fall asleep — occurring in the front and back parts of the brain. The team says identifying the location of these slow waves in the brain could distinguish between sluggish and impulsive behaviours.

The waves can also help make the distinction between the mind wandering, with high brain activity, and the mind blanking, with no brain activity.

The authors conclude that attention lapses share a common origin in the brain, which is the emergence of local, sleep-like brain waves within an awake brain. These waves acts like a “functional switch”, affecting the brain network activity at that point.

Depending on the location where they occur, they could lead to different responses. The phenomenon is called local sleep, and the authors state that this occurs not just when the brain is pushed to an extreme state of sleep deprivation, but also in well-rested individuals.

The findings were published in the journal Nature this week.

Also read: You are losing 30 minutes of sleep every working day, study shows

Brain waves

The human brain directs cognitive resources towards amplification of information relevant to a specific behavioural goal when we focus on a task at hand. But this attention can also be reoriented inwards, which we commonly refer to as loss of focus or mind wandering.

Our stream of thoughts can also pause when the mind blanks out and loses attention.

When our brain wanders, there is “rich and spontaneous” mental activity, whereas when our mind blanks, there is an absence of mental activity.

A defining trait of attention is its fleeting nature, state the researchers, and the difficulty humans and other animals have to maintain it on a task. Mind blanking and mind wandering often occurs without our knowledge or even will.

These occur due to voluntary or involuntary attention lapses, and their consequences can vary. Lapses in attention can lead to a lack of responsiveness or reactions that are sluggish and slow. But they can also result in impulsive and wrong or unnecessary responses.

Mind blanking, mind wandering, sluggish responses, and impulsive responses, are all also observed in people with sleep deprivation. Previous studies have shown that attention lapses increase as fatigue increases, and that both mind wandering and mind blanking occur during times between wakefulness and sleep.

As fatigue and sleep deprivation increase, the sleep-like slow waves start occurring in localised regions, leading to a phenomenon called local sleep. An increase in these waves can affect daily brain functions and cause attention lapses. Studies have also shown that increase in these waves lead to an increase in errors in tasks.

Studies have also shown that increase in these waves lead to an increase in errors in tasks.

Also read: Afternoon nap in healthy workspace can improve productivity among urban poor workers: Study

Study design

The study was small, with only 26 participants who were healthy. They were asked to perform mentally “undemanding” tasks like watching the screen and responding to ‘Go/NoGo’ signals.

Their brain activity was monitored using high-density electroencephalography, with 63 electrodes connected all over their scalps. Their pupil dilation was also measured as a marker of vigilance.

The participants were not in a state of sleep deprivation, and were not in environments conducive to falling asleep or dozing off, such as being reclined.

They were often interrupted by the researchers and asked about whether they had been focussing on the task, or were thinking about something else (mind wandering), or were thinking about nothing (mind blanking).

At the end of this experiment, participants reported focussing only about half the time. The rest of the time, their minds were blanking or wandering. The authors also monitored the behavioral patterns before the onset of mind wandering or blanking activities.

The findings from the experiment showed that both mind blanking and wandering decrease performance. Whenever the participants failed to stay on the task, they also reported feeling more tired.

Also read: A long, unbroken night of sleep may not be enough for you, new study shows

The findings

Mind blanking led the participants to more misses and slower response times, leading to a sluggish mental state. Mind wandering too induced more misses, but the response time of all participants was much faster, which the authors say back the idea that it leads to impulsive mental states.

The authors also found that during both mind blanking and wandering, the participants were in a state of lower vigilance, with significantly smaller pupils. But the pupil size did not vary between the two kinds of brain activity. Lowered vigilance and low pupil dilation was also correlated with an increase in brain wave amplitudes, leading to an increased level of slow waves.

But the pupil size did not vary between the two kinds of brain activity. Lowered vigilance and low pupil dilation was also correlated with an increase in brain wave amplitudes, leading to an increased level of slow waves.

The authors also noted that the location of where these slow waves occurred influenced responses. When they occurred in the electrodes at the front of the brain, participants were prone to responding faster and were more likely to have their mind wandering. Slow waves occurring at the back electrodes resulted in sluggish responses.

It seems therefore that posterior slow waves (leading to MB) could be a more global local sleep event, involving more cortical regions, which is also reflected in performance or vigilance ratings.

13/n pic.twitter.com/lJbiG0qhjW— Thomas Andrillon (@thandrillon) June 29, 2021

Mind wandering or slow waves in the front part of the brain also led to more false alarms, or accidentally clicking when the participant shouldn’t. Mind blanking or slow waves at the back led to more misses by not clicking when participant should.

Mind blanking or slow waves at the back led to more misses by not clicking when participant should.

This is caused by a change in how participants evaluated incoming informational evidence, with front waves accumulating evidence slower for NoGo signals, and back waves slower for ‘Go’ signals leading to slow response times.

The findings show a spatial and temporal relationship between local sleep and behavioral errors as measured by slow waves.

Also read: Sleeping after midnight is bad for your health, so is going to bed before 10pm, finds study

What makes you write / Sudo Null IT News

evg-crystal.ru sculpture "Thinker" Perhaps I'll start with my story. The desire to constantly take notes, write down your thoughts came from the need to respond to customers in Service Desk tickets of the system. The most difficult thing was to explain in words the moments when the process of restoring an emergency service is underway. The narrow framework of KPI forced me to write quickly, to mark each stage of work. Thus, it became a habit to record all the steps of the work in the system so that there was a time stamp. In addition to working with applications, from time to time I filled the internal knowledge base on typical situations. nine0003

The narrow framework of KPI forced me to write quickly, to mark each stage of work. Thus, it became a habit to record all the steps of the work in the system so that there was a time stamp. In addition to working with applications, from time to time I filled the internal knowledge base on typical situations. nine0003

The desire to write about your thoughts came in the midst of the coronavirus, when you had to stay at home, and in order to make the usual trip to the street, you had to order a pass. Habitual, office, dynamic life was locked in the four walls of the apartment.

mosday.ru author Yury DegtyarevOddly enough, there is a lot of free time. You no longer need to spend three hours on the road to work and back. As before, out of habit, I got up early, and until the corporate messenger was turned on, I could just surf the Internet. nine0003

The first days I just lay with my laptop, monitoring the news, how the virus is spreading, how companies send everyone to work remotely. I read how people cope with loneliness at home, how they run marathons around the couch, stories of endless humanity, when people began to help each other.

I read how people cope with loneliness at home, how they run marathons around the couch, stories of endless humanity, when people began to help each other.

The days flew by one after the other behind an empty scrolling tape. Internal remorse about thoughts of more productive use of time resulted in the search for courses to improve or acquire new skills. The result was my first post on the profile forum. From time to time I added text, adapting it to the topic of the forum. Anyway, there was something wrong, I just wanted to write my own texts. nine0003

Remember how the Internet was in the early 2000s. When users discovered personal blogs. Real blogs, no imposed advertising integration, no monopoly and recommendation feed of publications. Think long and hard about the design style of the main MySpace page, create your own site on narod.ru or start a blog on LiveJournal. Where are these platforms now?

At the moment, whatever you post on public platforms, all material is moderated and becomes the property of the platform. Such an alignment can already demotivate you to start writing at the very beginning. So I started writing locally, without public access. And it became like salvation0015 method of unloading the brain from the abundance of valuable information, which in any case is forgotten over time.

Such an alignment can already demotivate you to start writing at the very beginning. So I started writing locally, without public access. And it became like salvation0015 method of unloading the brain from the abundance of valuable information, which in any case is forgotten over time.

And, it turns out, a dual state. In the first version, you write a lot and without stopping, without fear of public censure. In the second, when aimed at the general access, it is very difficult to write. You need to be an expert in the topic you are writing about so that any question from users has an answer that will suit the majority. But you really want to know the opinion of other people, get a response or just words of support. nine0003

Regarding the question in the title: "What makes you write?". I would like to know whether you really decided to write on your own, or there are some external factors that influenced you to start opening up your thoughts or experiences to the public.

Reason began when the gods stopped talking He must have looked very strange among the students, some of whom knew him as a philosophy teacher who spoke in a deep baritone. He was in his early 50s, drank quite heavily, didn't have a full-time job, and probably wasn't interested in it. His position was precarious. “I don’t think the university paid him a regular salary,” recalls Roy Baumeister, then a student at Princeton and now a professor of psychology at the University of Florida. But, while among the young inhabitants of the hostel, Janes worked on his masterpiece, which he had been working on for many years before. nine0003

From the age of six, Janes was struck by the uniqueness of consciousness. Looking at the yellow forsythia flowers, he wondered if he could be sure that others saw the same yellow as he did. As a young man, he spent three years in a Pennsylvania prison for refusing to work in support of the war. One spring, watching a worm in the prison yard, he thought about what distinguishes the unreasonable earth from the worm, and the worm from himself. Such questions occupied him until the end of his life, and the book on which he worked would capture a whole generation that began to ask similar questions. nine0024

Such questions occupied him until the end of his life, and the book on which he worked would capture a whole generation that began to ask similar questions. nine0024

Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind, published in 1976, was not a bestseller. But sold with a bang. She has been featured in scientific and psychology journals such as Time, The New York Times, and Los Angeles Times. She was nominated for a national book award in 1978. New editions continued to come out, and Janes went on tour with lectures. He died of a heart attack at 1997; his book lives on. In 2000, another edition appeared on the shelves. It is still on sale today.

At the beginning of the book, Jaynes asks the question: “It is consciousness, the most self of all selves, which is everything and at the same time nothing—what is it? Where did it come from? And why?" Jaynes answers the question by revealing a version of the story in which humans were not fully sentient until about 3,000 years ago, and before that relied on a two-part, bicameral consciousness, in which one part spoke to the other with the voice of the gods, guiding it when any difficult situation. Bicameral consciousness eventually collapsed as human societies became more complex, and our ancestors awoke to a modern self-awareness, with an inner voice rooted, according to Jaynes, in language. nine0003

Bicameral consciousness eventually collapsed as human societies became more complex, and our ancestors awoke to a modern self-awareness, with an inner voice rooted, according to Jaynes, in language. nine0003

A remarkable thesis that does not particularly coincide with modern concepts of the work of consciousness. The idea that the ancient Greeks were not self-aware makes many people doubt it. By giving consciousness a cultural source, says Christoph Koch, a senior fellow at the Allen Institute for Neuroscience, "Janes denies the biological nature of consciousness."

But Koch and other neuroscientists and philosophers acknowledge that James' wild book is influential. “He was an old-fashioned autodidact who reached remarkable depths, had extraordinary ambition, followed his curiosity,” says philosopher Daniel Dennett. And the quest that Janes was involved in - trying to describe and explain the inner voice, the inner world in which we live - echoes today. The study of consciousness is gaining momentum in neuroscience laboratories around the world, but science has not yet come close to isolating subjective sensations. This is exactly what Jaynes has done so well in illuminating what it means to be alive and to be aware of it. nine0003

This is exactly what Jaynes has done so well in illuminating what it means to be alive and to be aware of it. nine0003

Janes was the son of a Unitarian minister in West Newton, Massachusetts. Although his father died when Janes was two years old, his voice lived on in the 48 volumes of his sermons, with which Janes apparently spent a lot of time growing up. In college, he experimented with philosophy and literature, but decided that the answers to his questions should be sought in psychology, which is chasing real data about the physical world. He went to college in 1941, but shortly thereafter the United States entered World War II. Janes, who consciously opposed the war, was sent to a civil service camp. He soon wrote a letter to the US Attorney General announcing that he was leaving the camp because he felt the camp's goals were not in line with his principles. “Can we work within the logic of a bad system to destroy it? Jesus didn't think so. I don't think so either." He was sent to prison, where he had plenty of time to think about the problem of consciousness. “Janes was a man of principles, and some might even say that he was too impulsive or reckless,” recalls a former student and neighbor. "He was fueled by energy by attacking windmills." nine0003

“Janes was a man of principles, and some might even say that he was too impulsive or reckless,” recalls a former student and neighbor. "He was fueled by energy by attacking windmills." nine0003

Released after three years, Jaynes was convinced that the emergence of consciousness as a result of evolution would help clarify animal experiments, and spent the next three years at Yale University. For a while, he believed that if a being is able to learn from experience, it has some experience, and therefore consciousness. He drove herds of Paramecia through labyrinths carved in wax on Bakelite, shocking them if they took a wrong turn. “I moved on to creatures with synaptic nervous systems, flatworms, earthworms, fish, reptiles that could learn, and did so under the naive assumption that I was chronicling the evolution of consciousness,” he recalls in his book. — Ridiculous! I'm afraid that it took several years when I finally realized that this assumption does not make any sense. Many beings are trainable, but they do not introspect. That was what tormented Jaynes. nine0003

That was what tormented Jaynes. nine0003

He also conducted more traditional studies of maternal behavior in animals under the direction of Frank Beach. At that time it was not easy to be interested in consciousness. One of the dominant psychological theories was behaviorism, which studied the external responses of humans and animals to stimuli. Electric shock training was in full swing, no one thought about the intangible world of thoughts, which is understandable - behaviorism was a reaction to earlier and less rigorous trends in psychology. But for most of Jaynes's career, inner feelings were out of control. For some members of the community, the study of consciousness was equated with an interest in occult practices. nine0003

In 1949, Jaynes left the institute without earning a degree, apparently refusing to submit a dissertation. It is not known exactly why this happened - someone says that his committee demanded corrections to it that he did not like, some claim that he was tired of the academic hierarchy, others - that he was just sick of everything. He once said that he simply did not want to pay a fee of $25. In 1977, while the book was already on the market, Jaynes completed his doctorate from Yale. But he doesn't seem to be disappointed by the lack of progress. He later wrote that a psychology based on rats in mazes rather than the human mind was like "bad poetry pretending to be science". nine0003

He once said that he simply did not want to pay a fee of $25. In 1977, while the book was already on the market, Jaynes completed his doctorate from Yale. But he doesn't seem to be disappointed by the lack of progress. He later wrote that a psychology based on rats in mazes rather than the human mind was like "bad poetry pretending to be science". nine0003

This was the beginning of an unusual journey. In the fall of 1949, he moved to England and became a playwright and actor, and for the next 15 years he darted back and forth across the ocean, alternating between plays and teaching, ending up at Princeton University in 1964. And all this time he read a lot and pondered the question of what consciousness is and how it could appear. By 1969, he was thinking about a paper that would describe the origin of consciousness as a fundamental cultural shift rather than the evolutionary phenomenon he was looking for. The work was to be a grandiose synthesis of science, archeology, anthropology and literature, and to use materials collected over the past two decades of his life. He thought he finally heard something snap into place. nine0003

He thought he finally heard something snap into place. nine0003

Although Janes, who died in 1997, wrote no other book, The Origin of Consciousness will carry his name to eternity. John Updike wrote in The New Yorker that when Jaynes “suggests that before the end of the second millennium B.C. man had no consciousness, and he automatically obeyed the voices of the gods, we are amazed, but forced to follow the development of this remarkable thesis through all the evidence supporting it, which he finds in ancient literature, modern behaviorism and such aberrant psychological phenomena as hypnotism, possession , glossolalia, prophecy, poetry and schizophrenia". nine0050

The book sets a lofty goal from the first lines. “Oh, what a world of unseen visions and heard silence, this illusory land of the mind!” Janes starts. "A secret theater of silent monologue and antecedent advice, an invisible estate of all moods, reflections and riddles, an endless refuge of disappointments and discoveries. "

"

To explore the origins of his inner earth, Jaynes first offers a masterful summary of what consciousness is not. This is not an intrinsic property of matter. This is not a learning process. It, oddly enough, is not required in various complex processes. Conscious concentration is needed to learn how to solve puzzles, serve tennis, or even play the piano. But after learning the skill, he goes beyond the horizon, into the blurry world of the subconscious. It is more difficult to perform if you think about it. From Jaynes' point of view, most of what is happening to you at the moment is not part of your consciousness until you pay attention to it. Did you feel the pressure of a chair on your back a second ago? Or did you feel it just now, when you asked yourself this question? nine0003

Consciousness, Jaynes tells readers, in a sentence that can be seen as a challenge to future scientists in the fields of philosophy and cognitive science, "is a much smaller part of our mental life than we are aware of, since we cannot be aware of the unconscious. " He illustrates this point wonderfully. “It's like asking a flashlight in a dark room to illuminate something that is not lit. A flashlight, since its light is shed in whatever direction it is turned, will have to conclude that there is light everywhere. It may also seem that consciousness fills the entire mind, although in fact, this is not so. nine0003

" He illustrates this point wonderfully. “It's like asking a flashlight in a dark room to illuminate something that is not lit. A flashlight, since its light is shed in whatever direction it is turned, will have to conclude that there is light everywhere. It may also seem that consciousness fills the entire mind, although in fact, this is not so. nine0003

Perhaps Jaynes is most struck by the fact that knowledge and even creative insights come to us without our participation. You can tell which of the two glasses of water is heavier without any conscious thought—you just know it right after you pick it up. In the case of problem solving, creative or otherwise, we give our minds information that needs to be processed, but are unable to get it to come up with an answer. He comes to us later, in the shower or on a walk. Janes told his neighbor that his theory finally took shape when he watched the ice drift on the St. Johns River. Something is at work that we have no idea about. nine0003

Jaynes paints a picture in which consciousness is just a thin frost on a sea of habits, instincts, or other processes, capable of doing much more than we think. “If our reasoning were correct,” he writes, “then it would be quite possible for there to be a race of people who can talk, judge, reason, solve problems, do most of everything that we can, and at the same time have no consciousness at all” .

“If our reasoning were correct,” he writes, “then it would be quite possible for there to be a race of people who can talk, judge, reason, solve problems, do most of everything that we can, and at the same time have no consciousness at all” .

Jaynes believes that language must have appeared before what he defines as consciousness was possible. So he decided to read the early texts, including the Iliad and the Odyssey, to look for signs of people not capable of introspection - only the sea, no frost. And he thinks he found it in the Iliad. He writes that the characters in the Iliad do not look inward and take no independent initiative. They only do what the gods advise them to do. When something is about to happen, the god appears and begins to speak. Without these voices, the heroes would stand motionless on the beaches of Troy like dolls. nine0003

It is already known that speech is localized in the left hemisphere and does not spread to both hemispheres. Jaynes suggests that the right hemisphere lacks language capabilities because it was previously used for something else—a source of instructional messages flowing to the speech centers on the left side of the brain. They manifested themselves in the form of hallucinations that helped people deal with situations that require a difficult response - for example, making decisions about government or a dangerous journey. nine0003

They manifested themselves in the form of hallucinations that helped people deal with situations that require a difficult response - for example, making decisions about government or a dangerous journey. nine0003

The combination of instincts and voices - bicameral consciousness - allowed people to survive for quite a long time, as long as their communities were subject to a clear hierarchy, Jaynes writes. But about 3,000 years ago, the stress of migration, natural disasters, and waves caused an overflow of limited voices. At this moment of collapse of the bicameral mind, pieces of consciousness began to come to awareness of themselves, and the voices stopped broadcasting. This led to a more flexible, if frightening, way of dealing with day-to-day decisions—more befitting of the chaos that began when the gods fell silent. By the time of The Odyssey, the characters are already capable of something like internal reflection, he says. The modern mind appears with its inner monologue and thirst for guidance from higher powers. nine0003

nine0003

The remainder of the book - 400 pages - describes what Jaynes sees as evidence of bicameralism and its collapse around the world from the Old Testament, Mayan stone carvings, Sumerian records. He gives an example of a carving of an Assyrian king kneeling on one knee in front of the god's empty throne, around 1230 BC. The frequent and successive migrations of population that took place at about the same time in what is now known as Greece, he considers the turmoil caused by the collapse. Jaynes discusses how this transition might affect today. “We, being at the end of the second millennium AD, are in a sense still immersed in this transition to a new mentality. Everywhere around us lie the remnants of our recent bicameral past,” he writes, admiring the breadth of his idea, captured by the pathos of the situation. "Our kings, presidents, judges, officials begin their service with oaths to the now silent deities, taking them on the records of the people who heard them last." nine0003

This is a book of wide scope and strange content. But she was extremely attractive. Part of it was that some readers had never thought about what consciousness was before. Perhaps for the first time, many people decided to touch the certainty of themselves, and found it was not what they expected. Jaynes's book came at a time when such upheavals were unusually powerful. In the 1970s, many people felt an increase in interest in questions of consciousness. Baumeister, who respects Jaynes and read proofs of the book before it was published, says that Jaynes tapped into the "spiritual scene" of the emerging New Age movement. nine0003

But she was extremely attractive. Part of it was that some readers had never thought about what consciousness was before. Perhaps for the first time, many people decided to touch the certainty of themselves, and found it was not what they expected. Jaynes's book came at a time when such upheavals were unusually powerful. In the 1970s, many people felt an increase in interest in questions of consciousness. Baumeister, who respects Jaynes and read proofs of the book before it was published, says that Jaynes tapped into the "spiritual scene" of the emerging New Age movement. nine0003

And the language - what a language! Wealth comparable to Nabokov. There is elegance, power and believability in his prose. She sounds prophetic. Seems true. And this greatly affects perception. Truth and beauty are intertwined in such a way that it is difficult to separate them. Physicist Ben Lilly, who runs the Storycollider project, recalls the time he discovered Janes' book. “I was in a group of people who hung out at newspaper and yearbook offices and talked about all sorts of intellectual things, dressing mostly in black,” says Lilly. - Somebody read it. I don't remember who was first, it wasn't me. And all of a sudden we thought it sounded great and everyone was reading it. You had to be a rebel, because she went against common sense. nine0003

- Somebody read it. I don't remember who was first, it wasn't me. And all of a sudden we thought it sounded great and everyone was reading it. You had to be a rebel, because she went against common sense. nine0003

It's easy to find holes in logic. For example, in the Iliad there are passages in which the characters look inside themselves, although Janes decided that they were added later or incorrectly translated. But these holes do not detract from the influence of the book. For readers such as Paul Haynes, founder of the science and philosophy journal Aeon, Jaynes's central thesis does not come first in the book's appeal. “I was attracted by his approach, style, inspiring and nostalgic mood of the text; not the specific details of the argument, albeit rather intriguing, writes Hynes. “Janes was willing to explore the cutting edge of consciousness on his own terms, without explaining its mysterious properties.” nine0003

In the meantime, over the last four decades, the winds have changed direction, as they often do in science when researchers hunt for the best questions to ask. Huge projects like the Allen Institute for Neuroscience and the Institute for Brain and Mind at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology are trying to understand the structure and function of the brain in order to answer many questions, including what consciousness is in the brain and how it is created, down to the level of individual neurons. A whole new field has emerged, behavioral economics, describing and using those moments in which we are not aware of what we are doing - the main theme of Jaynes's book - the ideas of which earned its founders, Daniel Kahneman and Vernon Smith the Nobel Prize. nine0003

Huge projects like the Allen Institute for Neuroscience and the Institute for Brain and Mind at the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology are trying to understand the structure and function of the brain in order to answer many questions, including what consciousness is in the brain and how it is created, down to the level of individual neurons. A whole new field has emerged, behavioral economics, describing and using those moments in which we are not aware of what we are doing - the main theme of Jaynes's book - the ideas of which earned its founders, Daniel Kahneman and Vernon Smith the Nobel Prize. nine0003

Eric Schwitzgebel, professor of philosophy at the University of California, Riverside, has been doing experiments to find out how aware we are of things we don't focus on, reflecting Jaynes's view that consciousness is essentially awareness. "It's not counterintuitive to think that you're only aware of what you're paying attention to at the moment," says Schwitzgebel. “But it's also reasonable to say that there's a lot going on in the background and on the periphery. Beyond concentration, we all have these sensations.” Schwitzguebel says the questions Jaynes was fascinated with are indeed hot topics in psychology and neuroscience. But at the same time, Jaynes's book remains on the verge of science. “The claim that the ancient Greeks were not conscious is still far from conventional wisdom,” he says. nine0003

Beyond concentration, we all have these sensations.” Schwitzguebel says the questions Jaynes was fascinated with are indeed hot topics in psychology and neuroscience. But at the same time, Jaynes's book remains on the verge of science. “The claim that the ancient Greeks were not conscious is still far from conventional wisdom,” he says. nine0003

Dennett, who called the book "wonderful and wacky," likes to use the benefit of the doubt on Jaynes. “Among the completely wild nonsense, there are a lot of great ideas,” he says. In particular, he finds very exciting the idea Jaynes insists that there is a difference between what goes on in the minds of animals and those of humans, and that this difference is rooted in language.

“I was on the edge of that idea myself, and Julian just sort of pushed me over the edge,” says Dennett. “There is such a difference between chimpanzee consciousness and human consciousness that it requires a special explanation, an explanation based on human recognition of natural language,” although this, of course, is far from exhaustive. "It's an eccentric position," he admits with a wry smile. “I haven’t been able to push conventional wisdom in that direction.” nine0003

"It's an eccentric position," he admits with a wry smile. “I haven’t been able to push conventional wisdom in that direction.” nine0003

Add to Jaynes' ideas, which are periodically mentioned by neuroscientists studying consciousness. In the 2010 book Self Comes to Mind, Antonio Damasio, professor of neuroscience and director of the USC Institute for Brain and Creativity, sympathizes with Janes' idea that something happened to the human mind in the relatively recent past. “In the accumulation of knowledge about people and the universe, constant reflection could well change the structure of one's autobiographical self and lead to a greater convergence of relatively little comparable aspects of data processing in the mind; the coordination of the work of the brain, first working on the principles of value, and then moving on to the principles of sanity, worked in our favor, ”he writes. But such approvals are quite rare. More common are the responses given by neurophilosopher Patricia Churchland, professor emeritus at the University of California, San Diego. "She's trendy," she says of Janes' book. “I don’t think she added anything tangible to our understanding of the nature of consciousness and how consciousness comes about as a result of how the brain works.” nine0003

"She's trendy," she says of Janes' book. “I don’t think she added anything tangible to our understanding of the nature of consciousness and how consciousness comes about as a result of how the brain works.” nine0003

Jaynes himself considered his theory a scientific contribution and was disappointed by the reaction of the research community. Although he enjoyed the public interest in his work, a fight with these windmills in particular could upset even an experienced black sheep. Janes began to drink more. The second book, which was supposed to develop the ideas of the first, was never completed.

That's how his, albeit strange, legacy lives on. Over the years, Dennett occasionally mentioned in his conversations that he was sure Jaynes had stumbled upon something worthwhile. After all the hype, when the crowd has dispersed and the public discussions have ended, every time there is someone who can say: “Now I can step out of the shadows. I also think Jaynes has written a wonderful book. " nine0003

" nine0003

Marcel Kuijsten is an IT professional who leads the "Julian Jaynes Community", which he estimates has 500-600 enthusiasts from all over the world. The group has an online forum where they discuss Jaynes's theory, and in 2013 they held a conference for the first time, meeting in Virginia for a couple of days to speak. “It was an incredible experience,” he says.

Kuijsten believes that Jaynes's many critics have simply not bothered to try to understand his reasoning, which he admits is rather difficult to grasp. “They have ingrained preconceived notions about what consciousness means to them,” he says. “Perhaps they are just reading a book review.” But he is patient. “I'm not going to change anyone's point of view - it's just a waste of time. I want to provide the best quality information and good resources for people who have read the book and want to discuss it." nine0003

To this end, Kuijsten and the "community" have published books containing Jaynes' work and new essays on him and his work.