What are the five steps of grief

The Stages of Grief: Accepting the Unacceptable

June 8, 2020

Posted by Caitlin Stanaway, Psy.D., Licensed Psychologist, UWCC

The pandemic has impacted our routines, social lives, school, work, and more. It has caused the loss of lives around the globe, as well as the loss of normalcy. The recent death of George Floyd has put police brutality, murders of Black and Brown people, racial and social injustice into the spotlight. There are many losses to grieve amidst the intensity of civil unrest, on top of more typical stressors like taking finals and looking for a job.

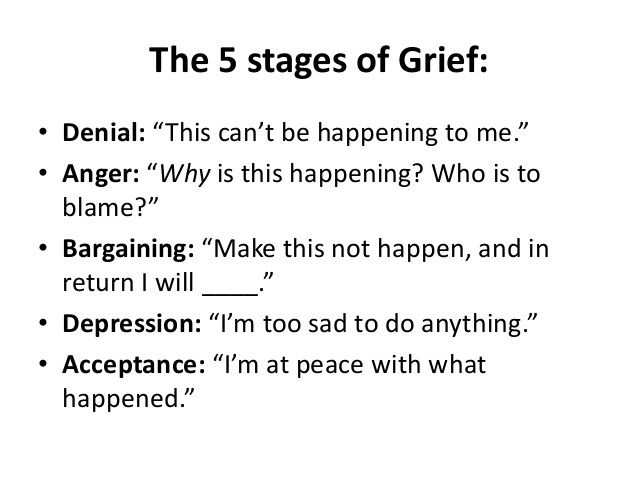

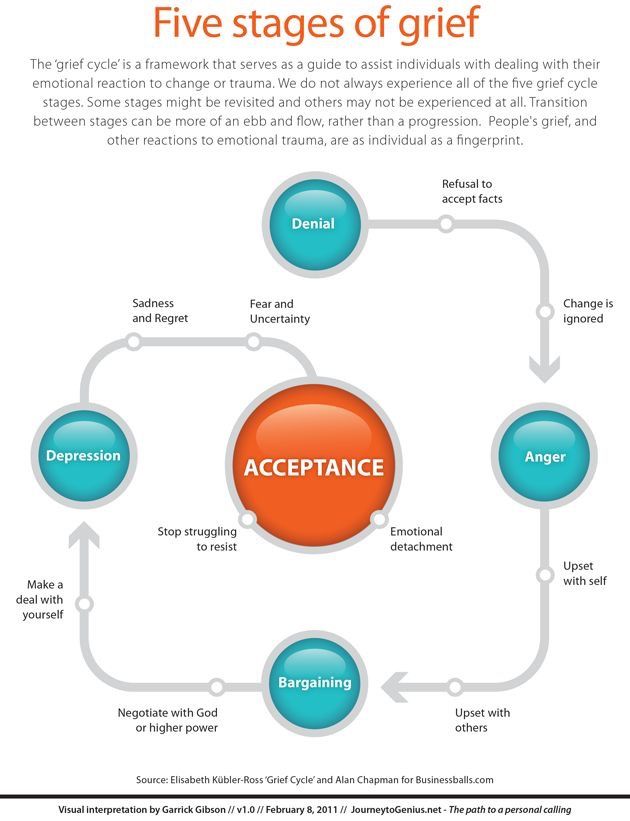

Elisabeth Kubler-Ross developed the five stages of grief in her 1969 book, On Death and Dying. Grief is typically conceptualized as a reaction to death, though it can occur anytime reality is not what we wanted, hoped for, or expected.

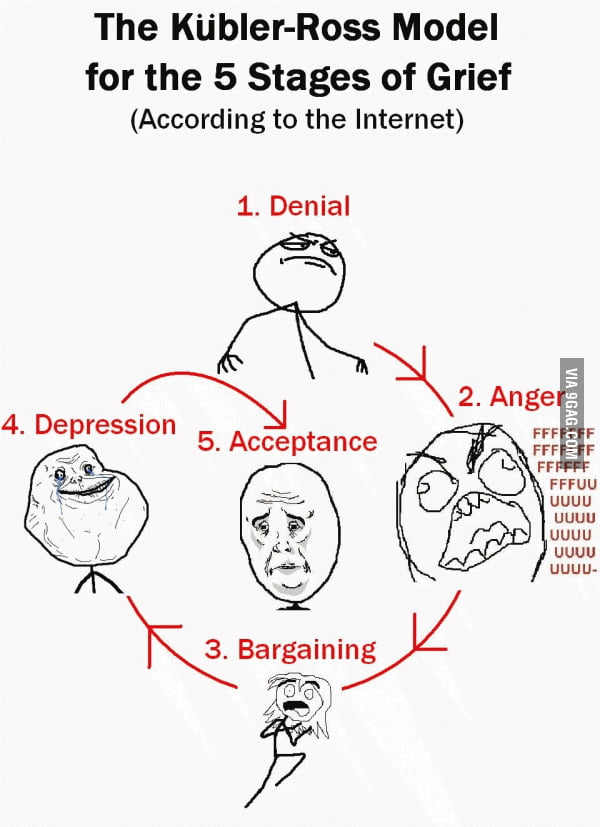

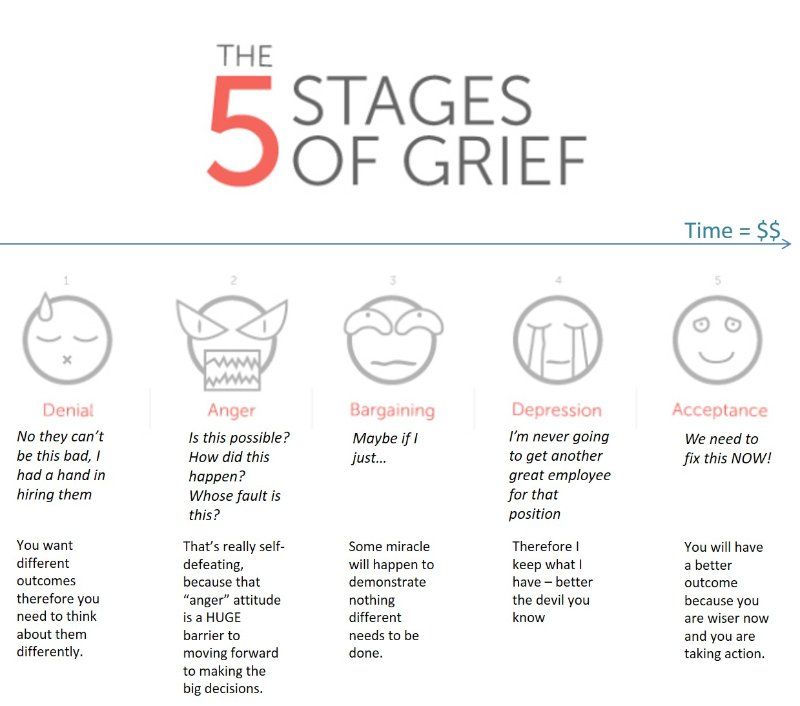

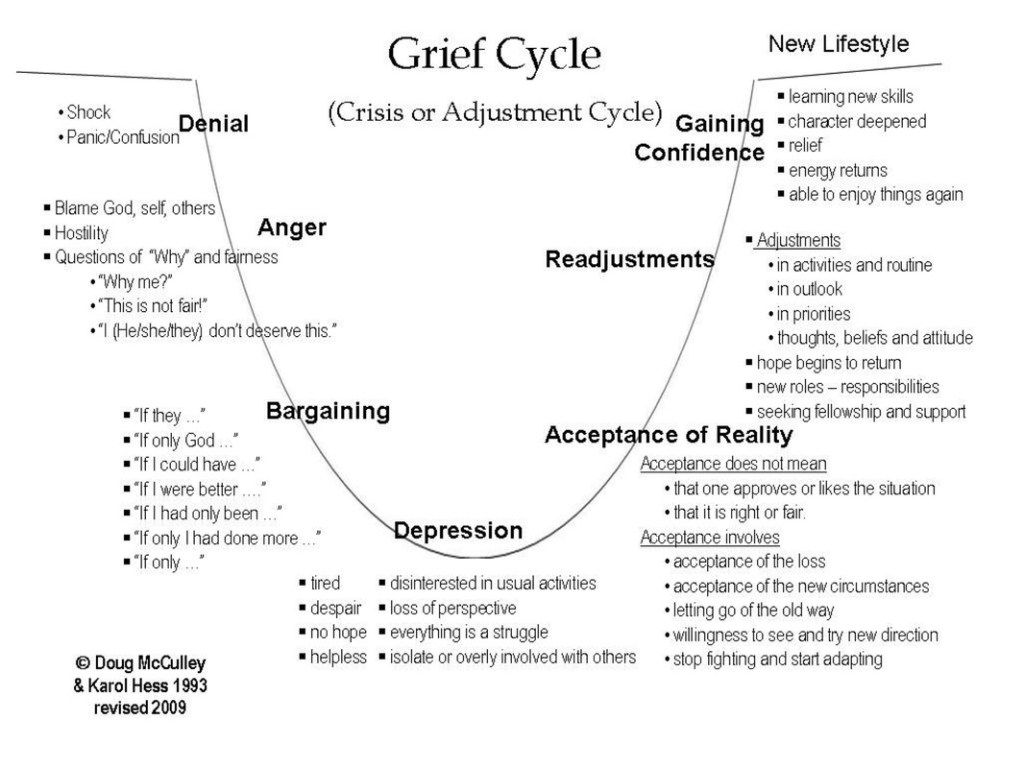

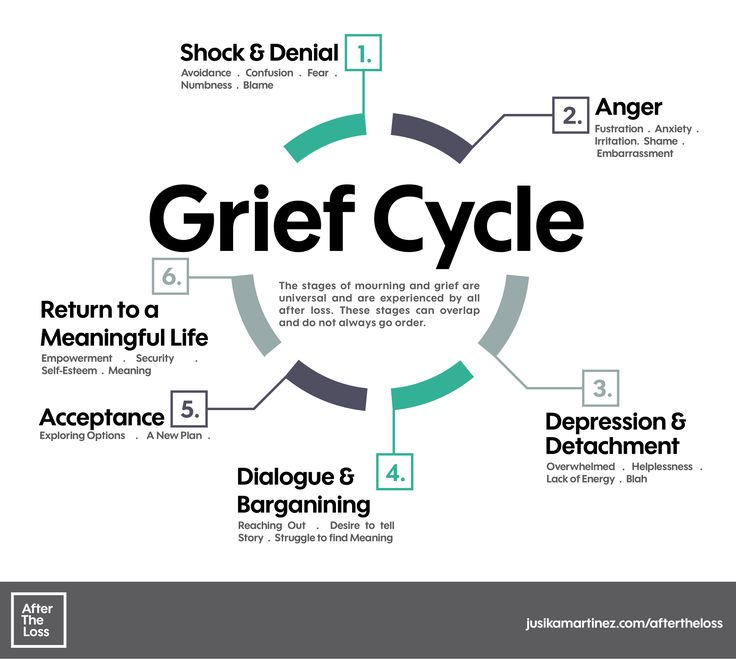

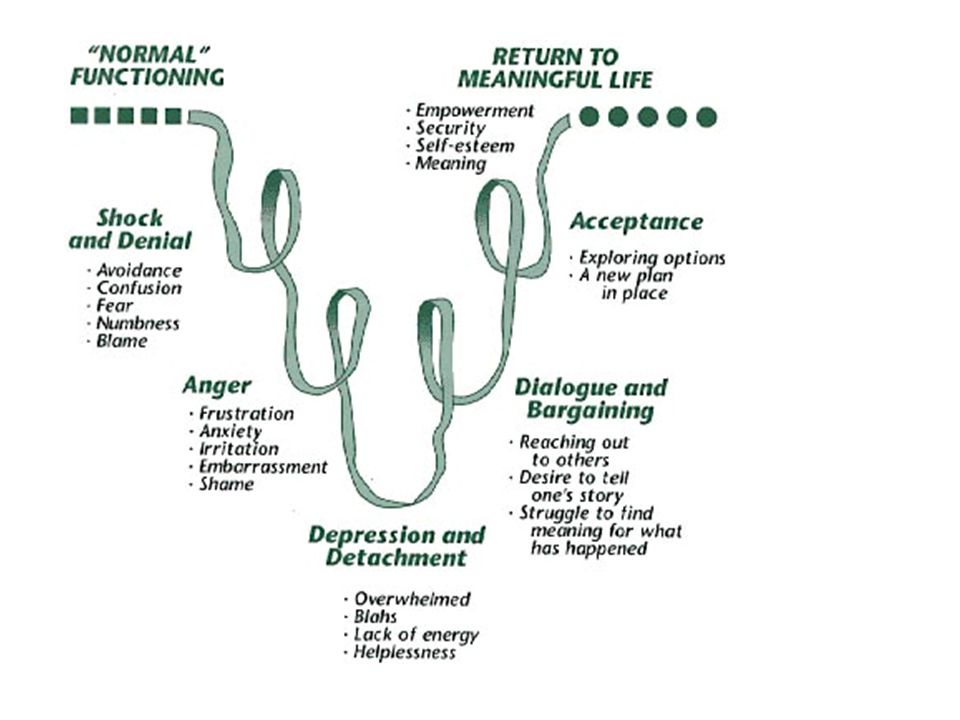

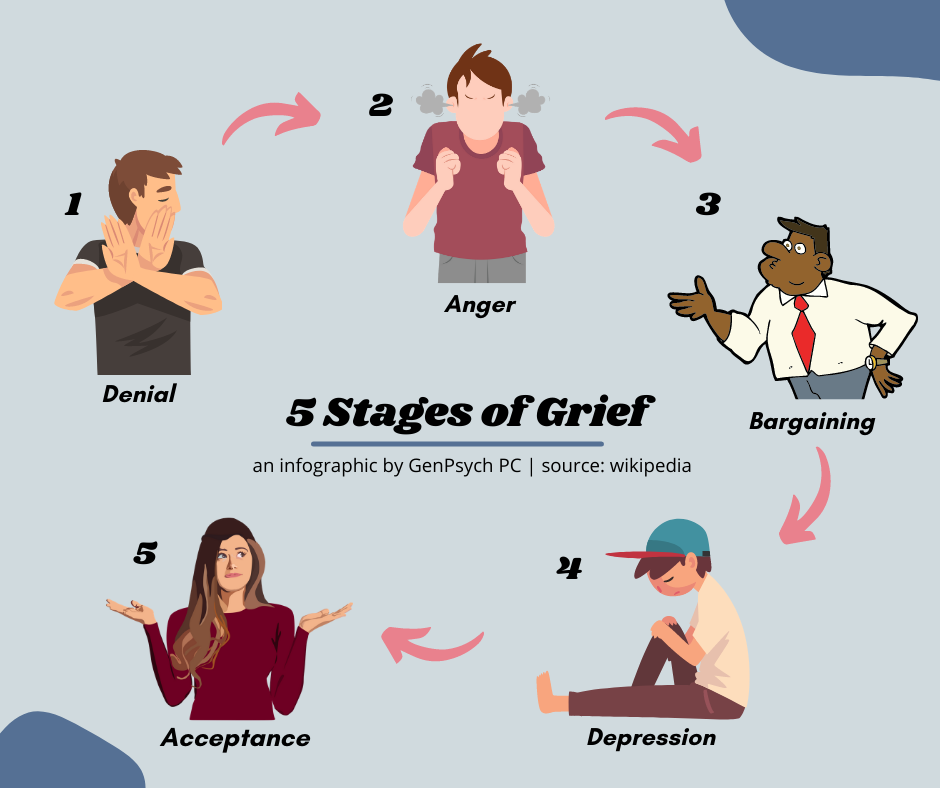

Persistent, traumatic grief can cause us to cycle (sometimes quickly) through the stages of grief: denial, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. These stages are our attempts to process change and protect ourselves while we adapt to a new reality. While there are consistent elements within each stage, the process of grieving looks different for everyone.

When you combine experiences of stress and trauma to grief, it is overwhelming. It takes a toll on our mental and physical health. Our minds and bodies are consistently being impacted by the stress response, a nervous system reaction to feeling threatened. It triggers the release of adrenaline and cortisol, impacting sleep, appetite, making it difficult to function at your best.

Symptoms of anxiety and depression may develop, as well as trauma symptoms like intrusive thoughts, nightmares, feeling disconnected from self. Trauma related to racial injustice is chronic. Resources for Black healing, including crisis support, self-care, and reducing cortisol levels in response to racial stressors can be found here.

Being aware of the grief stages and how you uniquely experience them can increase self-understanding and compassion. It can help you better understand your needs and prioritize getting them met.

It can help you better understand your needs and prioritize getting them met.

Denial

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| avoidance | shock |

| procrastination | numbness |

| forgetting | confusion |

| easily distracted | shutting down |

| mindless behaviors | |

| keeping busy all the time | |

| thinking/saying, “I’m fine” or “it’s fine” |

Anger

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| pessimism | frustration |

| cynicism | impatience |

| sarcasm | resentment |

| irritability | embarrassment |

| being aggressive or passive-aggressive | rage |

| getting into arguments or physical fights | feeling out of control |

| increased alcohol or drug use |

Bargaining

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| ruminating on the future or past | guilt |

| over-thinking and worrying | shame |

| comparing self to others | blame |

| predicting the future and assuming the worst | fear, anxiety |

| perfectionism | insecurity |

| thinking/saying, “I should have…” or ”If only…” | |

| judgment toward self and/or others |

Depression

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| sleep and appetite changes | sadness |

| reduced energy | despair |

| reduced social interest | helplessness |

| reduced motivation | hopelessness |

| crying | disappointment |

| increased alcohol or drug use | overwhelmed |

Acceptance

| can look like: | can feel like: |

|---|---|

| mindful behaviors | “good enough” |

| engaging with reality as it is | courageous |

| “this is how it is right now” | validation |

| being present in the moment | self-compassion |

| able to be vulnerable & tolerate emotions | pride |

| assertive, non-defensive, honest communication | wisdom |

| adapting, coping, responding skillfully |

Generally, if we are not in the stage of acceptance then we are in some way fighting against or avoiding reality. We might start sleeping more. Our mood or anxious thoughts might become the focus of attention, distracting from external stressors. We might use alcohol or drugs to avoid or disconnect from reality. We might keep our focus on tasks, responsibilities, or the needs of others – staying busy as much as possible to avoid feeling distress.

We might start sleeping more. Our mood or anxious thoughts might become the focus of attention, distracting from external stressors. We might use alcohol or drugs to avoid or disconnect from reality. We might keep our focus on tasks, responsibilities, or the needs of others – staying busy as much as possible to avoid feeling distress.

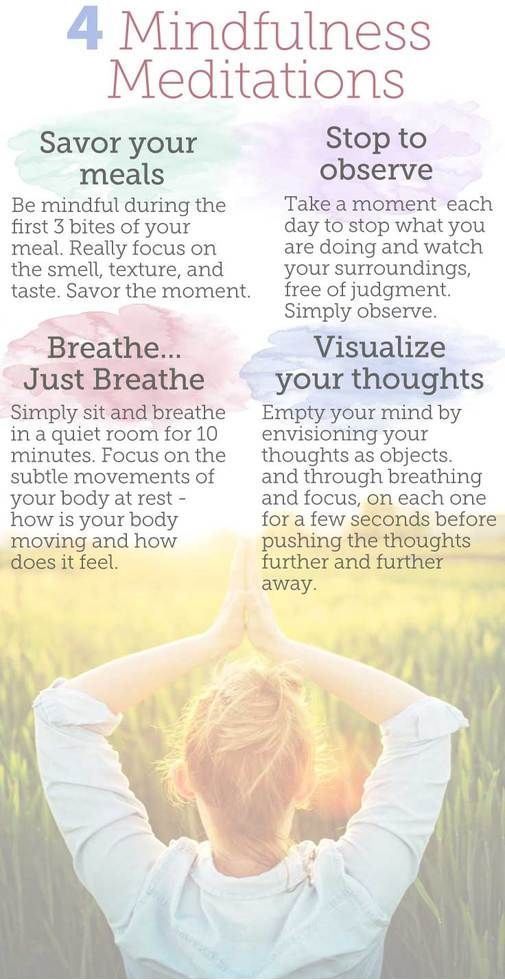

Acceptance doesn’t mean not experiencing distress, emotions or trauma. It does not mean you condone what is happening. It means noticing what you are fighting against, validating your desire to fight against it, and re-orienting yourself to the reality of the moment you are in. It means not getting stuck, or getting un-stuck, from other stages. Mindfulness and a non-judgmental, curious attitude can be a big help.

Acceptance might look like saying to yourself: “If I sleep too long today I’ll keep sleeping through the mornings. I’m going to prioritize getting my schedule regulated.” It might look like noticing: “I’m directing my anger and sadness about what’s going on toward myself and ruminating on self-criticisms. I’ll acknowledge my anger and what it’s really about.” Or reflecting, “how could I not be angry about ___? Who wouldn’t be anxious about ___? Of course it’s extremely hard to accept ___”; It might look like checking in on yourself: “If I keep neglecting my own needs and focusing on work/others, I’ll end up feeling burned out and exhausted. I’ll take time to assess how I’m doing and what I need.”

I’ll acknowledge my anger and what it’s really about.” Or reflecting, “how could I not be angry about ___? Who wouldn’t be anxious about ___? Of course it’s extremely hard to accept ___”; It might look like checking in on yourself: “If I keep neglecting my own needs and focusing on work/others, I’ll end up feeling burned out and exhausted. I’ll take time to assess how I’m doing and what I need.”

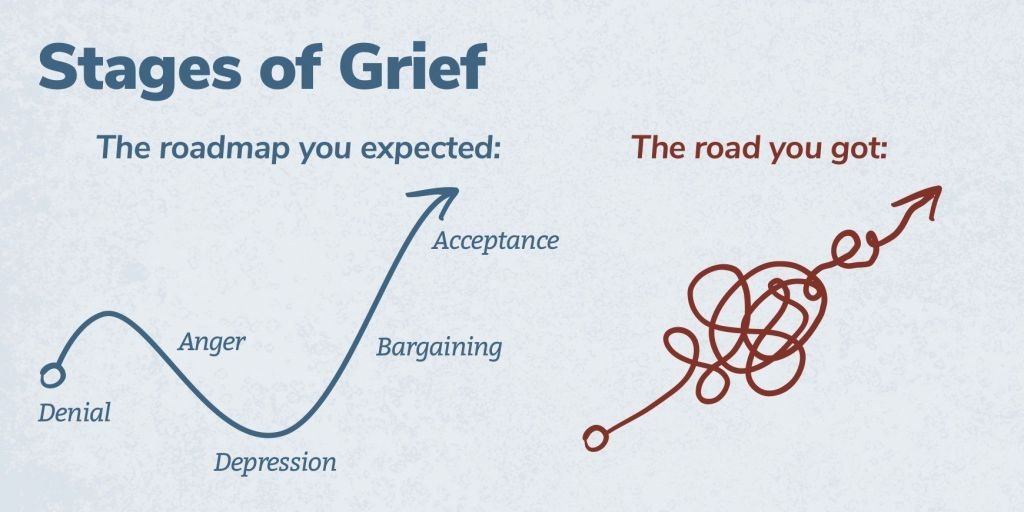

It is rare to move through the stages in a linear way. It is normal to experience ups and downs in mood, thoughts, attitudes, and behaviors. It can be difficult maintaining acceptance while things feel so unacceptable.

If you are feeling overwhelmed by grief, loss, trauma you do not have to go through it alone. The Counseling Center can offer culturally-sensitive support and guidance through the grieving process.

The 5 Stages of Grief

3 min read

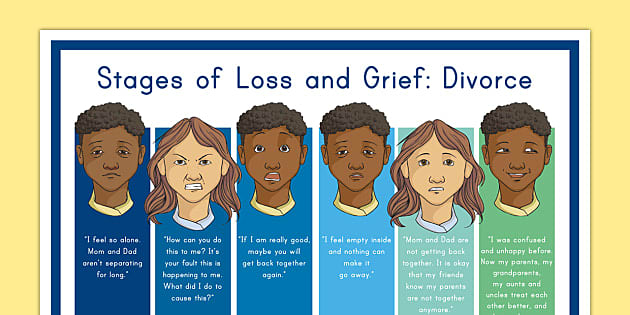

Considering the multitude of ways the pandemic has changed our lives, many people have experienced grief in reaction to all kinds of losses this year. Grief can be experienced in reaction to any significant loss, whether it be job/income loss, loss of child care, loss of routine and a sense of safety, loss of community and togetherness, or loss of a loved one.

Grief can be experienced in reaction to any significant loss, whether it be job/income loss, loss of child care, loss of routine and a sense of safety, loss of community and togetherness, or loss of a loved one.

Instead of consisting of one emotion or state, grief is better understood as a process. About 50 years ago, experts noticed a pattern in the experience of grief and they summarized this pattern as the “five stages of grief”, which are: denial and isolation, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

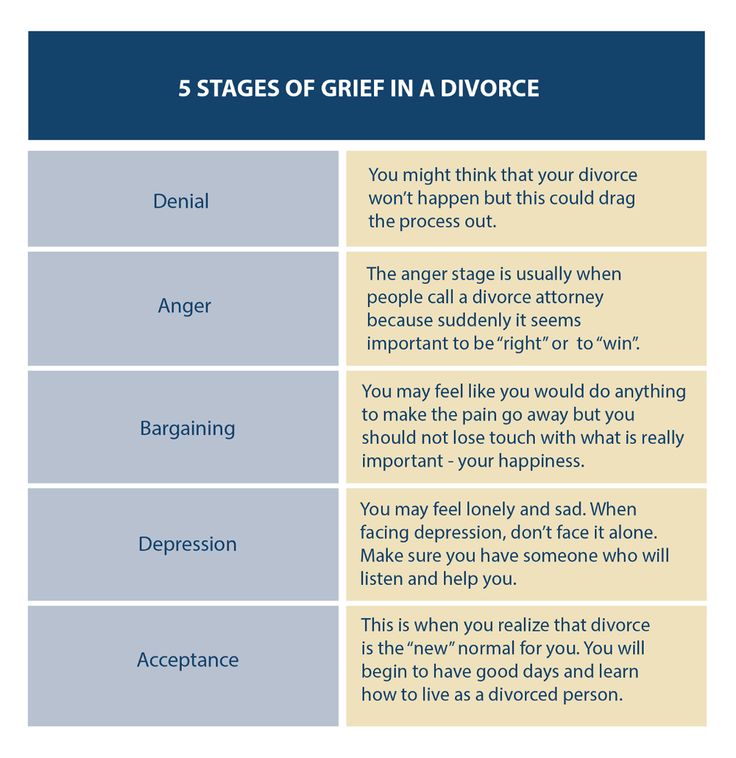

The experts who published these stages have since clarified that someone who is grieving could experience the five stages in any order, and they may experience only some of the stages as opposed to all of them. Further, there is no set amount of time for which someone grieving will remain in any one stage, and someone can be experiencing more than one of the stages at any one time. In other words, grief is a very personal and nuanced experience, and everyone grieves in their own way.

Understanding the dynamic nature of grief can help those coping through loss as well as those helping others who are grieving. Here is more information on the five stages of grief:

1. Denial and Isolation

When we lose someone or something important to us, it is natural to reject the idea that it could be true. In turn, we may isolate ourselves to avoid reminders of the truth. Others who wish to comfort us may only make us hurt more while we are still coming to terms with the loss.

2. Anger

When it is no longer possible to live in denial, it is common to become frustrated and angry. We might feel like something extremely unfair has happened to us and wonder what we did to deserve it.

3. Bargaining

In this stage, we might somehow seek to change the circumstances of the situation causing our grief. For example, a religious person whose loved one is dying might seek to negotiate with God to keep the person alive. Bargaining may help the grieving person cope by allowing them a sense of control in the face of helplessness.![]()

4. Depression

In this stage, we feel the full weight of our sadness over the loss. Feeling extremely down in the wake of a loss is normal; however, it is important to be aware that clinical depression is different from grief, and they are treated differently by mental health professionals. See “The Blurred Line Between Grief and Depression” for more information.

5. Acceptance

Eventually, the grieving person may come to terms with their loss. Accepting a loss does not necessarily mean the person is no longer grieving. In fact, many grief experts say that grief can continue for a lifetime after a major loss, and coping with the loss only becomes easier over time. Waves of grief can be triggered by reminders of the loss long after it has happened and long after the person has “accepted” it. These waves may also trigger a crossover into any of the other four stages of grief.

In sum, grief is a personal, nuanced, and complicated process; it will not look the same for any two people who are grieving. However, those who are grieving may experience similar emotions along the way.

However, those who are grieving may experience similar emotions along the way.

If you or someone you know is grieving, Great Lakes Psychology Group can help. GLPG makes it easy to get started with online therapy. If you’d prefer to start online therapy in the wake of the pandemic but anticipate that you’d prefer to switch to in-office therapy at some point, you have the option of choosing a therapist from the GLPG network located in your community.

Related Information:

- Grief Counseling

- 7 Ways to Be There for a Friend Who Is Grieving

- Online Therapy for Grief

Five stages of grief. The Rise and Fall of Kübler-Ross

- Lucy Burns

- BBC

Image copyright Getty Images

Denial. Anger. Finding a compromise. Despair. Adoption. Many people know the theory according to which grief, when receiving unbearable information for a person, goes through these steps. The scope of its application is wide: from hospices to boards of directors of companies.

The scope of its application is wide: from hospices to boards of directors of companies.

A recent interview with a psychologist in English on the Internet proves that the perception of the current quarantine is subject to the same rules. But do we all experience the same?

When Swiss psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross began working in American hospitals in 1958, she was struck by the lack of methods of psychological care for dying patients.

- A method that can predict your death

"Everything was impersonal, the attention was paid exclusively to the technical side of things," she told the BBC at 1983 year. “Terminally ill patients were left to their own devices, no one talked to them.”

She started a workshop with Colorado State University medical students based on her conversations with cancer patients about what they thought and felt.

Author photo, LIFE/Getty Images

Photo caption, Elisabeth Kübler-Ross talks to a woman with leukemia in Chicago, 1969. Seminar participants observe through a special mirror glass

Seminar participants observe through a special mirror glass

Despite the misunderstanding and resistance of a number of colleagues, soon there was nowhere for an apple to fall at the Kübler-Ross seminars.

In 1969 she published a book, On Death and Dying, in which she quoted typical statements from her patients and then moved on to discuss how to help doomed people pass from life as free of fear and pain as possible.

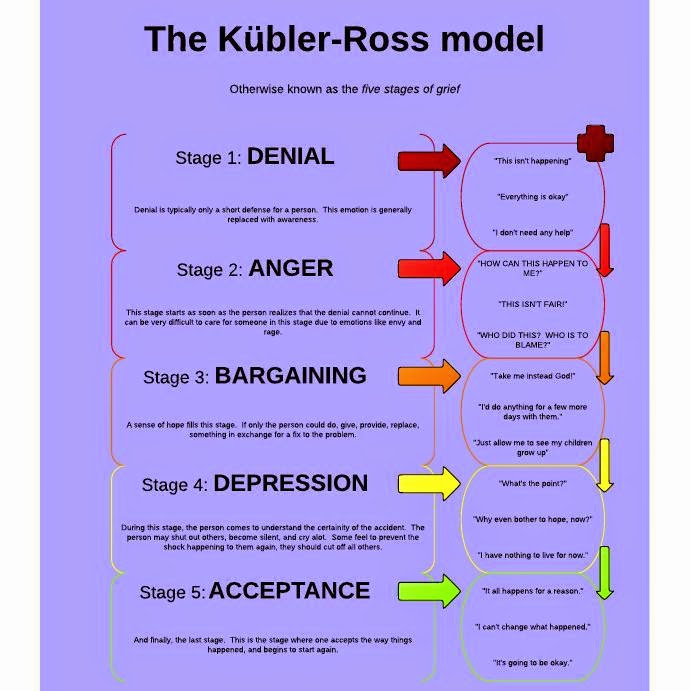

Kübler-Ross described in detail the five emotional states that a person goes through after being diagnosed with a terminal diagnosis:

- Denial: "No, that can't be true"

- Anger: "Why me? Why? It's not fair!!!"

- Bargaining: "There must be a way to save myself, or at least improve my situation! I'll think of something, I'll behave properly and do whatever is necessary!"

- Depression: "There is no way out, everything is indifferent"

- Acceptance: "Well, we must somehow live with this and prepare for the last journey"

difficult situation.

A separate chapter of the book is devoted to each of the stages. In addition to the five main ones, the author identified intermediate states - the first shock, preliminary grief, hope - from 10 to 13 types in total.

Image copyright Getty Images

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross died in 2004. Her son, Ken Ross, says she never insisted that every person must go through these five stages in sequence.

"It was a flexible framework, not a panacea for dealing with grief. If people wanted to use other theories and models, the mother did not object. She wanted to start a discussion of the topic first," he says.

- Last will: how did the photo of a dying American touch the world?

- "You hear everything, Fernando." How was the evening in honor of the terminally ill football player

The book "On Death and Dying" became a bestseller, and Elisabeth Kübler-Ross was soon inundated with letters from patients and doctors from all over the world.

"The phone kept ringing, and the postman started visiting us twice a day," recalls Ken Ross.

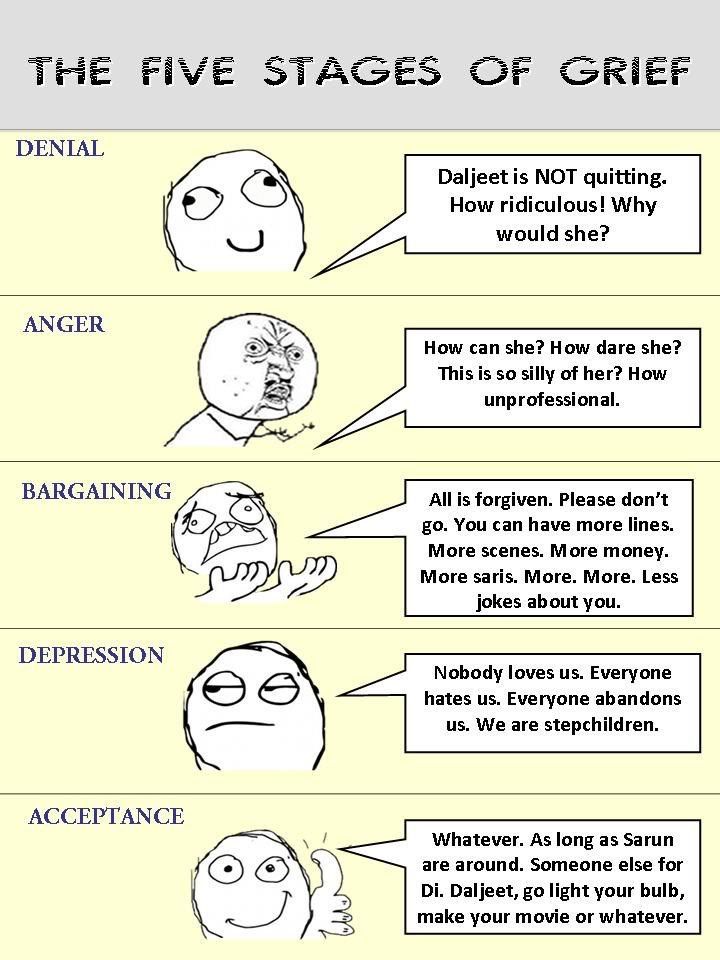

The notorious five steps took on a life of their own. Following the doctors, patients and their relatives learned about them. They were mentioned by the characters of the series "Star Trek" and "Sesame Street". They were parodied in cartoons, they gave food for creativity to the mass of musicians and artists and gave rise to many successful memes.

Literally thousands of scientific papers have been written that have applied the theory of the five steps to a wide variety of people and situations, from athletes suffering career-incompatible injuries to Apple fans' worries about the release of the 5th iPhone.

Image copyright, Getty Images

Skip the Podcast and continue reading.

Podcast

What was that?

We quickly, simply and clearly explain what happened, why it's important and what's next.

episodes

The End of History Podcast

Kübler-Ross's legacy has found its way into corporate governance: Big companies from Boeing to IBM (including the BBC) have used her "change curve" to help employees at times of great business change.

And during the coronavirus pandemic, it applies, says psychologist David Kessler.

Kessler worked with Elisabeth Kübler-Ross and co-authored her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve. His interview with the Harvard Business Review at the start of the pandemic garnered a lot of attention online as people everywhere searched for solutions to their emotional problems.

"And here, first comes denial: the virus is not terrible, nothing will happen to me. Then anger: who dares to deprive me of my usual life and force me to stay at home?! Then an attempt to find a compromise: okay, if after two weeks of social distancing it gets better, then why not? Followed by sadness: no one knows when it will end. And, finally, acceptance: the world is now like this, you have to somehow live with it, "describes David Kessler.

And, finally, acceptance: the world is now like this, you have to somehow live with it, "describes David Kessler.

"As you can see, strength comes with acceptance. It gives you control: I can wash my hands, I can keep a safe distance, I can work from home," he says.

"It's a roadmap," says George Bonanno, professor of clinical psychology and head of the Loss, Trauma, and Emotion Laboratory at Columbia University. "When people are in pain, they want to know: how long will it last? What will happen to me? something to grab on to. And the five-step model gives them that opportunity."

"This scheme is seductive," notes Charles Corr, social psychologist and author of Death and Dying, Life and Being. "It offers an easy solution: sort everyone, and it takes no more than the fingers of one hand to label each one." .

George Bonanno sees this as a possible harm.

"People who don't fit exactly into these stages - and I've seen the majority of them - may decide they're grieving the wrong way, so to speak," he explains.

According to him, over the years he has seen many cases when people themselves inspired that they must certainly experience this and that, or they were convinced of this by friends and relatives, but they did not feel it and decided, that they need a doctor.

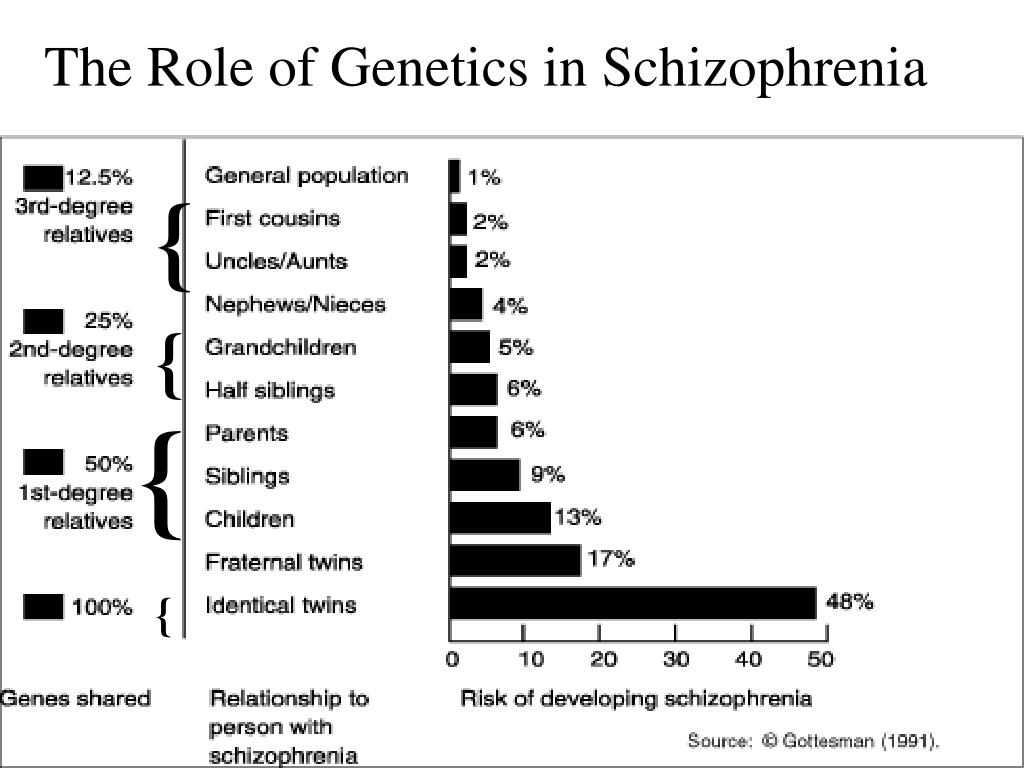

Experimental evidence of the existence of the five stages of grief is not enough. The longest and most extensive bereavement interview was conducted in 2007.

According to him, the most common state at any time is acceptance, only a few go through the stage of denial, and the second most common emotion is longing.

However, according to David Kessler, while scientists debate the nuances and terms, people who experience grief continue to find meaning in the Kübler-Ross scheme.

"I meet people who tell me, 'I don't know what's wrong with me. Now I'm angry, and a minute later I'm sad. I must be crazy.” And I say, “It has names. These are called the stages of grief. ” The person says, “Oh, so there is a special stage called 'anger'? It's about me!" And feels more normal."

” The person says, “Oh, so there is a special stage called 'anger'? It's about me!" And feels more normal."

Image copyright, Getty Images

"People need catchy statements. If Kübler-Ross hadn't called it stages and stated that there are exactly five of them, then she probably would have been closer to the truth. But then she would not have attracted to attention," says Charles Corr.

He believes that talking about the five stages distracts from the main scientific legacy of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross.

"She wanted to take on the topic of death and dying in the broadest sense: how to help terminally ill people come to terms with their diagnosis, how to help those who care for them, support these patients and cope with their own emotions, how to help everyone live a full life, realizing that we are not eternal,” says Charles Corr.

"The terminally ill can teach us everything: not only how to die, but also how to live," said Elisabeth Kübler-Ross at 1983 year.

During the 1970s and 1980s, she traveled the world, giving lectures and giving workshops to thousands of people. She was a passionate supporter of the hospice idea pioneered by British nurse Cecily Saunders.

Kübler-Ross has established hospices in many countries, the first in the Netherlands in 1999. Time magazine named her one of the 100 most important thinkers of the 20th century.

Professor Kübler-Ross' scientific reputation was shaken after she became fascinated with theories about the afterlife and began to experiment with mediums.

One of them, a certain Jay Barham, practiced non-standard religious-erotic therapy, in particular, he persuaded women to have sex, assuring that he was possessed by a person close to them from the afterlife. In 1979, because of this, a loud scandal arose.

In the late 1980s, she tried to set up a hospice for children with AIDS in rural Virginia, but faced strong local opposition to the idea.

In 1995, her house caught fire under suspicious circumstances. The next day Kübler-Ross had her first stroke.

She spent the last nine years of her life with her son in Arizona, moving around in a wheelchair.

In her last interview with the famous TV presenter Oprah Winfrey, she said that at the thought of her own death she feels only anger.

"The public wanted the famed expert on death and dying to be some kind of angelic personality and quickly get to the stage of acceptance," says Ken Ross. "But we all deal with grief and loss as best we can."

The theory of the five stages of grief is not widely taught in medical schools these days. It is more popular at corporate trainings under the name "Curve of Change".

Since then, there have been many theories about how to deal with your grief.

David Kessler, with the consent of Kübler-Ross's family, added a sixth stage to the five: the understanding that everything that is done makes sense.

"Understanding can come in a million different ways. Let's say I've become a better person after losing a loved one. Maybe my loved one passed away in a different way than it should have happened, and I can try to make the world a better place to this has not happened to others," says David Kessler.

Charles Corr recommends the "double process model". It was developed by Dutch researchers Margaret Stroebe and Nenk Schut and suggests that a person in grief is simultaneously experiencing a loss and preparing himself for new things and life challenges.

George Bonanno talks about four trajectories of grief. Some people have great stamina and do not fall into depression, or it is weakly expressed in them, others remain morally broken for many years, others recover relatively close, but then a second wave of grief rolls over them, and finally, the fourth becomes stronger from the loss.

Over time, one way or another, the vast majority of people get better.

But Professor Bonanno admits that his approach is less clear-cut than the five-stage theory.

"I can say to a person: 'Time heals.' But that doesn't sound so convincing," he says.

Grief is difficult to control and hard to endure. The thought that there is some kind of road map that suggests a way out is comforting, even if it is an illusion.

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, in her latest book, Grief and How We Grieve, wrote that she did not expect to sort out the tangled human emotions.

Everyone experiences grief in their own way, even if some patterns can sometimes be deduced. Everyone goes their own way.

how to help a person at every stage

home / Blog / 5 stages of mourning: how to help a person at each stage

Reading time: 5 minutes

|

May 23, 2022

Get our articles in messengers

The article was created with the participation of an expert

Barinova Oksana Vladimirovna

Practicing psychologist, trainer, specialist in family counseling. Candidate of Psychological Sciences, professor. Author of more than 150 scientific papers.

Candidate of Psychological Sciences, professor. Author of more than 150 scientific papers.

Experiencing grief, a person often goes through 5 stages: shock, anger, bargaining, depression, acceptance. Each of them is important and has its own characteristics. Oksana Vladimirovna Barinova, our teacher-expert, practicing psychologist, specialist in family counseling, candidate of psychological sciences, professor, spoke about how to help a person at each stage of mourning.

Read in the article:

- Shock (denial)

- Anger (guilt)

- Trade

- Depression

- Acceptance

When providing psychological assistance to people who have experienced loss, it is important to consider at what stage of experiencing the loss they are.

In the initial stages, you need to tell a person about what the process of mourning is and what its structure is. The psychologist is encouraged to use the active listening technique to reflect the feelings and emotions associated with the loss. This will help the client understand what is happening to him and help establish a trusting relationship.

This will help the client understand what is happening to him and help establish a trusting relationship.

In the later stages of mourning, focus on the specific negative consequences of the loss. And based on this, select the appropriate methods of psychological assistance.

The process of mourning is complex, and there are actually more than five stages in it. On average, a person goes through all the stages of mourning in 1–1.5 years. But the path can be bumpy. The mourner can skip stages, go back, go in his own order and pace. For example, sometimes there is no stage of denial or anger. If you or your client is not moving according to the scheme, then you need to remember that this is natural and normal.

Most people go through 5 main stages, so we will analyze them in more detail.

Cycle of grief

Shock (denial)

Peculiarities of the stage. The person acts detached or as if nothing has happened.