War feelings and emotions

Soldiers: The War Within

“Guilt is a part of the battlefield that often goes unrecognized,” writes Nancy Sherman, a professor at Georgetown University, in her book The Untold War: Inside the Hearts, Minds and Souls of Our Soldiers. But along with profound guilt comes a variety of emotions and moral issues that tug at soldiers, creating an inner war.

Sherman, who also served as the Inaugural Distinguished Chair in Ethics at the Naval Academy, delves into the emotional toll war takes on soldiers. Her book is based on her interviews with 40 soldiers. Most of the soldiers fought in Iraq and Afghanistan, while some fought in Vietnam and the World Wars.

She poignantly looks at their stories from the lens of philosophy and psychoanalysis, using these frameworks to better understand and analyze their words.

Sherman writes:

And so I have listened to soldiers with both a philosopher’s ear and a psychoanalyst’s ear. Soldiers are genuinely torn by the feelings of war — they desire raw revenge at times, though they wish they wanted a nobler justice; they feel pride and patriotism tinged with shame, complicity, betrayal and guilt.

They worry if they have sullied themselves, if they love their war buddies more than their wives or husbands, if they can be honest with a generation of soldiers that follow. They want to feel whole, but they see in the mirror that an arm is missing, or having bagged their buddies’ body parts, they feel guilty for returning home intact.

In Chapter 4, “The Guilt They Carry,” Sherman reveals the various ways soldiers feel culpability. For instance, before their first deployment, soldiers worry about killing another human being. They worry how they’ll judge themselves or be judged by a higher power. Even if soldiers aren’t legally or even morally culpable, as Sherman writes, they still struggle with guilt.

This struggle can stem from accidental misfires that have killed soldiers or from minor but murky transgressions. One Army Major in charge of an infantry company in Iraq doesn’t go a day without thinking, at least in passing, about the young private who was killed when the gun from a Bradley Fighting Vehicle accidentally misfired. He still struggles with his “own personal guilt.”

He still struggles with his “own personal guilt.”

A World War II veteran, who was part of the Normandy invasion, still feels uneasy about stripping their own dead soldiers, even though they were — understandably — taking their weapons. Another vet who served in the Canadian army in WWII wrote his family about the tension he felt eating German chickens. Yet another felt great guilt after seeing the wallet of a dead enemy soldier. It had contained family photos just like the American soldier had carried.

Soldiers also feel a kind of survival guilt, or what Sherman refers to as “luck guilt.” They feel guilty if they survive, and their fellow soldiers don’t. The phenomenon of survivor guilt is not new, but the term relatively is. It was first introduced in the psychiatric literature in 1961. It referred to the intense guilt Holocaust survivors felt — as though they were the “living dead,” as though their existence was a betrayal to the deceased.

Being sent home while others are still on the frontlines is another source of guilt. Soldiers spoke with Sherman about “needing to return to their brothers and sisters in arms.” She described this guilt as “a kind of empathic distress for those still at war, mixed with a sense of solidarity and anxiety about betraying that solidarity.”

Soldiers spoke with Sherman about “needing to return to their brothers and sisters in arms.” She described this guilt as “a kind of empathic distress for those still at war, mixed with a sense of solidarity and anxiety about betraying that solidarity.”

As a society, we typically worry that soldiers get desensitized to killing. While Sherman acknowledged that this might happen to some soldiers, this wasn’t what she heard in her interviews.

The soldiers with whom I have talked feel the tremendous weight of their actions and consequences. Sometimes they extend their responsibility and guilt beyond what is reasonably within their dominion: they are far more likely to say, “If only I hadn’t” or “If only I could have,” than “It’s not my fault” or simply leave things at “I did my best.”

Their guilty feelings often get mixed with shame. Sherman writes:

[The topic of guilt] is often the elephant in the room. And this is so, in part, because guilt feelings are often borne with shame.

Shame, like guilt, is also directed inward. Its focus, unlike guilt, is not so much an action that harms others as on personal defects of character or status, often felt to be exposed before others and a matter of social discredit.

Sherman stresses the importance of having a society that understands and appreciates the inner war soldiers also fight. As she concludes in the Prologue:

Soldiers, both men and women, often keep their deepest struggles in waging war to themselves. But as a public, we, too, need to know how war feels, for war’s residue should not just be a soldier’s private burden. It ought to be something that we, who do not don the uniform, recognize and understand as well.

* * *

You can learn more about Nancy Sherman and her work at her website.

4 Major Emotions of War and Peace in the Middle Ages

Date published: June 1, 2017

According to Assistant Professor of History Kelly Gibson, early medieval writers gave lessons on how one should feel by describing the good emotions of good people and the bad emotions of bad people. These authors were usually close to their rulers, so their writings reflected current political ideals and could have influenced political practices. They recorded history in a way that flattered their rulers, so the emotions ascribed to these rulers in these writings must be viewed as paragons and perhaps not accurate representations of how these people actually behaved all of the time.

These authors were usually close to their rulers, so their writings reflected current political ideals and could have influenced political practices. They recorded history in a way that flattered their rulers, so the emotions ascribed to these rulers in these writings must be viewed as paragons and perhaps not accurate representations of how these people actually behaved all of the time.

“For example, Einhard's Life of Charlemagne highlights Charlemagne's patience and does not portray him as angry, although he may have been angry,” said Gibson. “This source illustrates a change in the acceptability of royal anger in the later eighth century. In contrast to sources from the early eighth century, which describe lots of angry kings, sources from the later eighth century through much of the ninth century generally omit the Carolingian ruler's anger. Some authors working during this time copied earlier histories but left out that the king was angry.”

Some authors working during this time copied earlier histories but left out that the king was angry.”

1. Anger and 2. Pride: Emotions of War

“Pride went hand in hand with anger as one of the two big emotions of disorder; patience and humility were the opposites of these and could check them,” said Gibson.

Carolingian-era authors, usually monks and clerics, read and wrote biblical commentaries as well as histories, using Scripture and earlier commentaries to understand the conflicts of their own time. They tended to start at the beginning, with the Book of Genesis, and work through the books, paying special attention to “first conflicts”: the first conflict between good and evil, the first conflict between brothers. The story of Cain and Abel, for example, illustrated the emotions that led to conflict: Cain killed Abel out of anger, greed, jealousy and pride.

In contrast to largely emotionless Carolingian rulers, their enemies have the same emotions that characterized Cain in biblical commentaries. Historians describing rebellions against the king consistently ascribed anger (particularly wild rage, sometimes verging on insanity or perhaps demonic possession), fear, greed and pride to the rebels. Scholars also applied these negative emotions to enemies of the church, accusing heretics of anger and pride in the treatises that refuted their ideas. Anger caused disorder not only in one's mind but in society, church and kingdom at large.

3. Love and 4. Joy: Emotions of Peace

On the other hand, love — especially of God or of one’s brother — created social bonds that led to peace, and acting in loving or peaceful ways led to joy. At the same time that anger became a less acceptable emotion in rulers, the joy of military conquest and the treasures obtained through war shifted instead to emphasize joy from peacemaking. If Charlemagne, for example, handled a situation in a peaceful way, he would return home happy. Joy also came from religious festivals and from seeing one’s family.

At the same time that anger became a less acceptable emotion in rulers, the joy of military conquest and the treasures obtained through war shifted instead to emphasize joy from peacemaking. If Charlemagne, for example, handled a situation in a peaceful way, he would return home happy. Joy also came from religious festivals and from seeing one’s family.

Because clergy were often the authors of these histories, they perhaps also became the basis of sermons for laypeople, adapted from the original Latin and forming a broader pastoral program. However, they also addressed the war leaders of the world: kings and their followers.

“People tend to think of the Middle Ages as violent, and there were a lot of wars, but there were also attempts to encourage certain emotions that would create peace and harmony,” said Gibson.

How to understand our feelings during the war

Sometimes it is difficult to understand what we feel, it seems that this is an emotional whirlwind that is difficult to survive and easier to block. Experts at the Institute for Cognitive Modeling report that it can be difficult to let go of control over your emotions and allow them to be experienced. If you feel overwhelmed, stop, ask yourself if you are now in conditional safety. If yes, switch to an activity that calms and relaxes you.

Our psyche is so arranged that we can work with our feelings while being safe. In conditions of real danger, the survival mode is triggered.

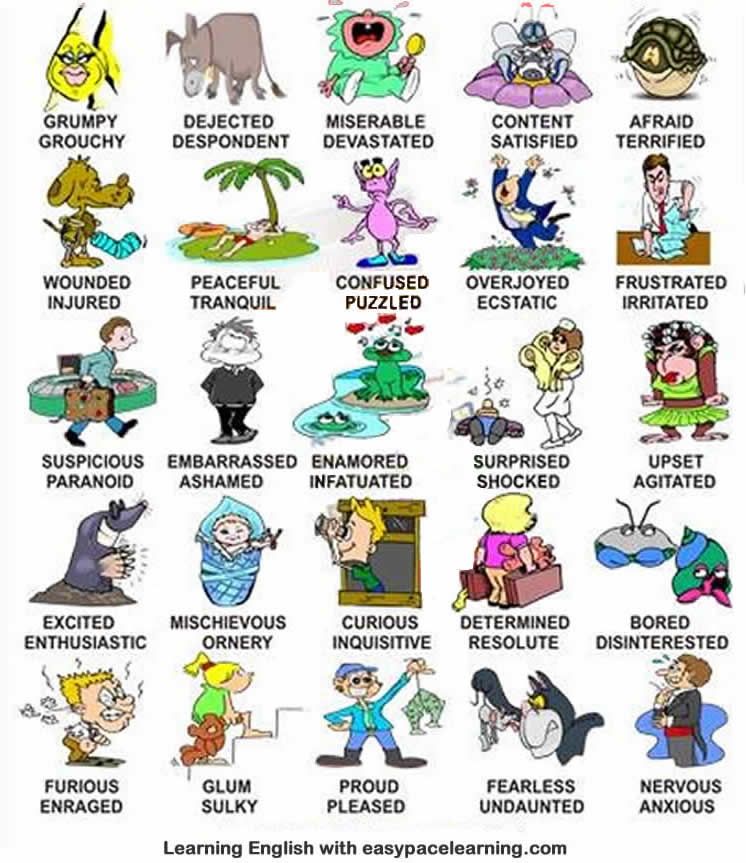

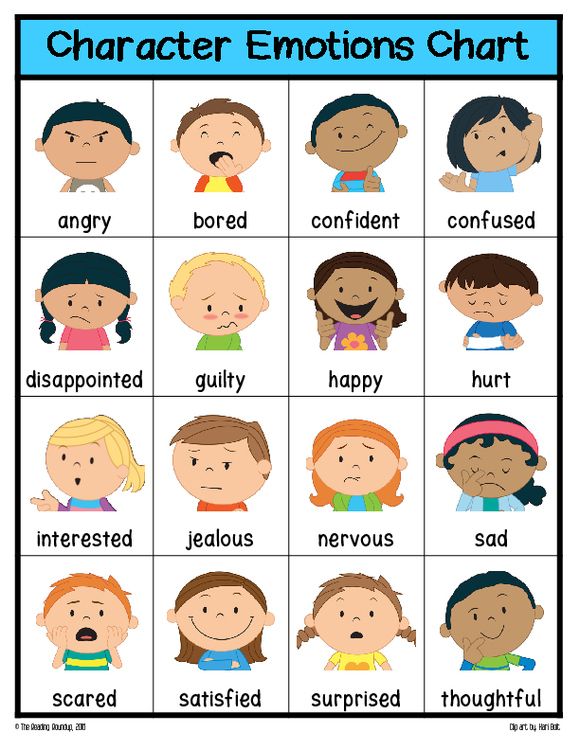

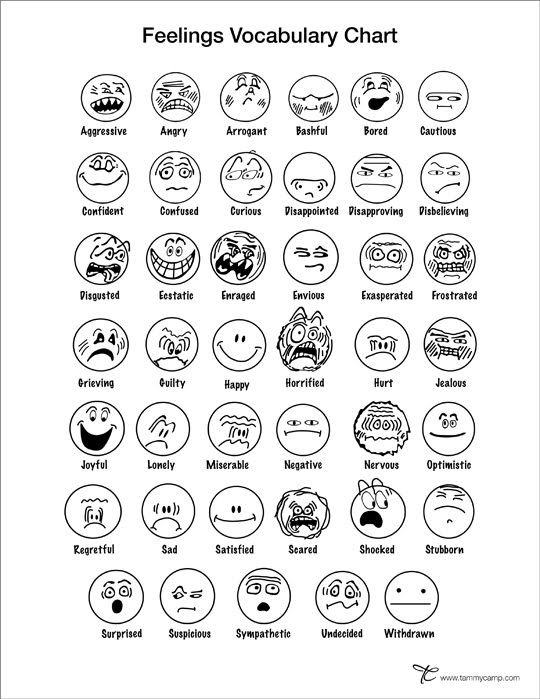

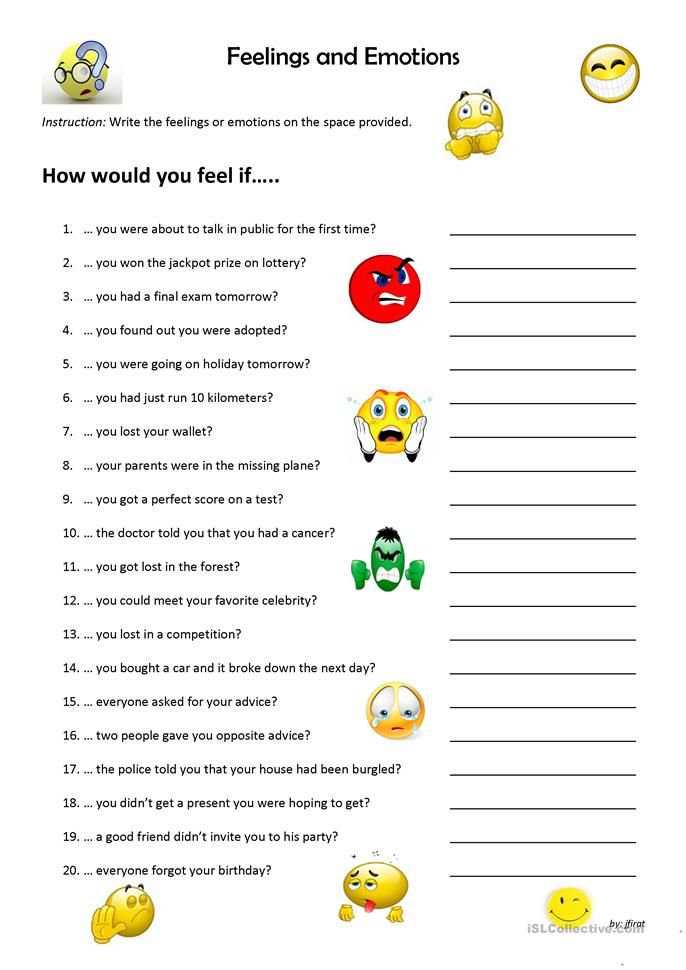

Identifying your feelings

Allow yourself to feel your emotions in a safe place. This will help you recognize them.

Try to relax. Go where you feel comfortable and safe. Close your eyes, take a deep breath and try to relax.

Pay attention to your body. You may be expressing your emotions physically. This can help you understand what emotions you are experiencing. For example, if your heart is beating fast and your breathing is shallow, this could indicate fear or panic. If your muscles are tense, you may become angry.

This can help you understand what emotions you are experiencing. For example, if your heart is beating fast and your breathing is shallow, this could indicate fear or panic. If your muscles are tense, you may become angry.

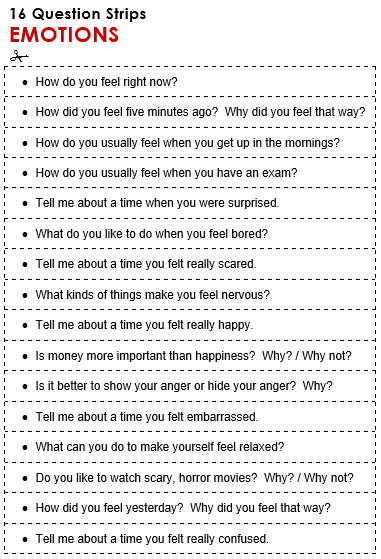

Turn your attention inward and try to focus on what you are feeling. Try not to judge your emotions, just allow them to be. If you can, try to name your feelings.

How strong are your feelings? It may be helpful for you to rate your emotions from one to ten. For example, how many out of ten do you feel angry? Sadness? Fear?

Emotions are complex, and we rarely experience just one emotion at a time. You may experience a mix of emotions that change throughout the day.

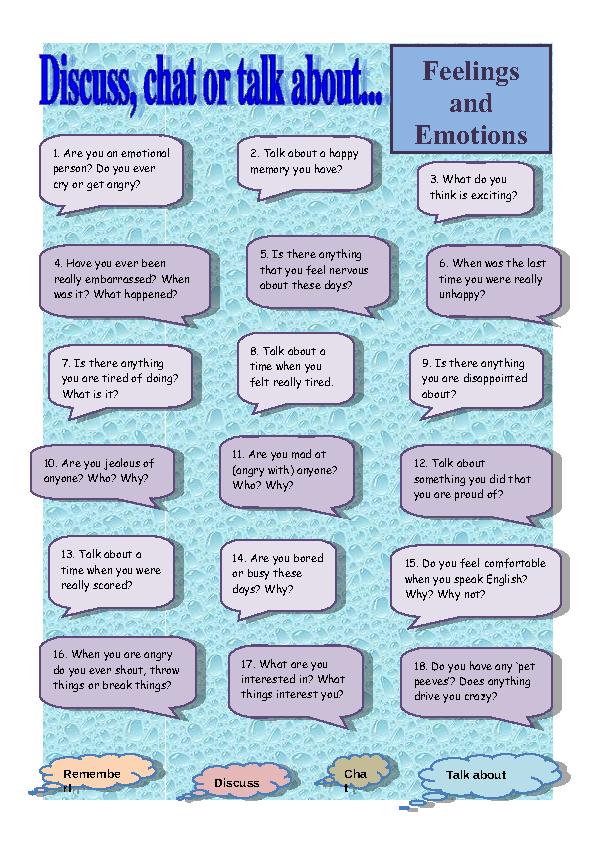

Understanding your feelings

Once you have identified the feeling, try to analyze why you are feeling it.

Take time to ask yourself: Why do I feel this way? This can help you identify the thoughts or beliefs behind your feelings.

You can then begin to work through these thoughts and beliefs to see how useful they are to you.

Whatever you feel, remind yourself that this is a sincere answer.

It's normal to be really upset, worried, or scared, and it's normal to feel that way months, years, or decades after a traumatic event has happened to you.

No one should ever blame you for how you feel or expect you to just "get over it".

If you need help and support, the 24/7 online mental health platform Tell Me can help. You need to briefly describe your request and submit an application through the site. Consultations are free online.

Tags: ukraine2022, psychology blog, war in Ukraine

Advertising

Featured Materials

Cauliflower steaks: an elementary recipe

5 biographies of women that inspire you to become the author of your life...

Cultural guide: where to go in December 2022

90,000 During the war, many Ukrainians experience emotional ups and downs.

The psychologist explains how to learn how to manage emotions and move on to the stage of adaptation

The psychologist explains how to learn how to manage emotions and move on to the stage of adaptation “The mental state of Ukrainians is not very stable now: we are in abnormal circumstances,” says psychologist Oksana Efremova. Such instability is a normal reaction to abnormal circumstances. Changes in emotional states during the war - this is typical. The question is how we act and return ourselves to a rational state

Forbes launched the YouTube project "Land of Heroes". Watch the new episode about how Kyivstar and Vodafone suffered from the war

Together with Oksana Efremova, Forbes compiled a memo on how to manage your emotions and use them most constructively.

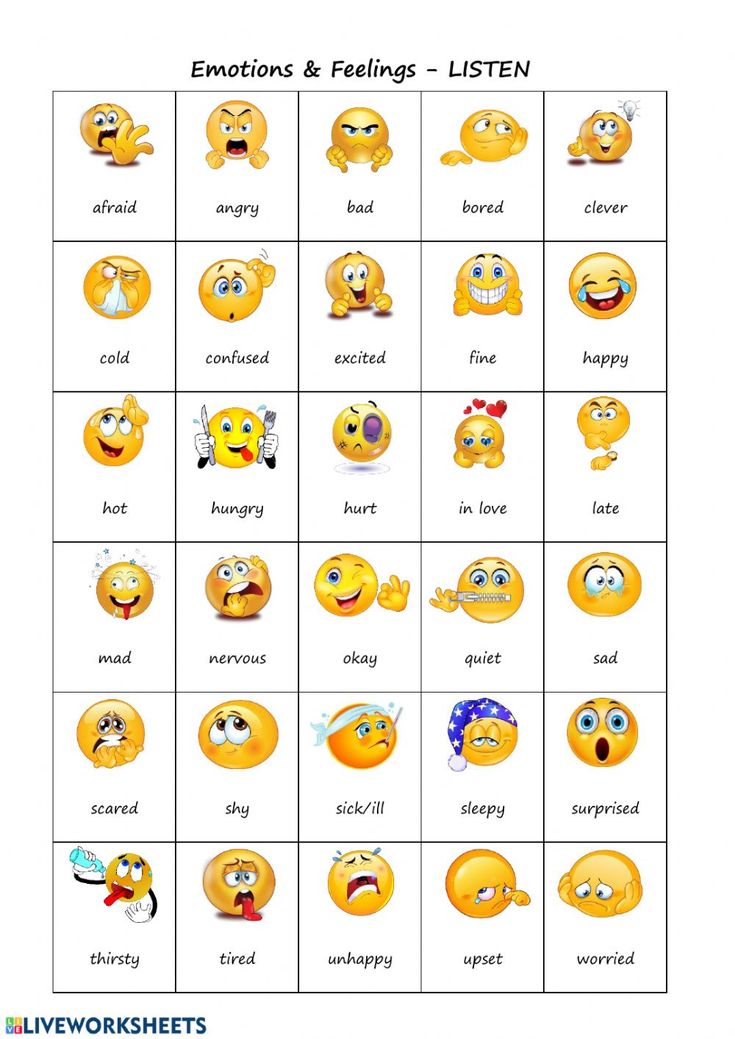

Emotional waves have a certain sequence, Efremova explains. “Of course, each person has his own specifics,” adds the psychologist. During the day, personal mood changes can occur, when at first a person is sad, then anxious, then he feels angry. But, if we consider the average state of society, emotions alternate as follows:

- confusion

- anxiety, fear, panic

- anger, irritation

- euphoria

- apathy, depressive symptoms

Apathy, fatigue and depressive symptoms occur on about 10 days of normal stress. So it can be assumed that the Ukrainians are now more or less somewhere at this stage. “In parallel, those who left may experience the guilt of the survivor: “I am safe as long as someone risks their life,” Efremova warns.

So it can be assumed that the Ukrainians are now more or less somewhere at this stage. “In parallel, those who left may experience the guilt of the survivor: “I am safe as long as someone risks their life,” Efremova warns.

After the apathy phase, we enter the stabilization phase. “Emotional waves will be repeated, but since we are already familiar with them, they will go more gently,” says Efremova. What happens during the adaptation period? We think about what will happen next, how to act in the new reality, get used to uncertainty and still make plans for the future. We realize that everything has changed and we need to live in accordance with the new conditions.

It is very important to enter the adaptation phase, in which we will act rationally, consciously and more steadily. “Remember: we need not only to survive, but also to live during the war, earn money, pay taxes,” Efremova notes. “After the war, we will also have a lot of work to restore everything that was destroyed. ”

”

In a state of adaptation, you need to understand: we are in a new environment for an indefinite period. You have to learn how to work with them.

Universal tips for managing emotions

There is a separate work protocol for each emotion, notes Efremova. Therefore, it is somewhat difficult to give universal advice, so there will be few of them.

The main thing to remember is that your emotions are normal. Analyze what exactly is happening to you, what emotion you are experiencing and help each other. “Right now it is very important to be in society, if possible,” emphasizes the psychologist. Then it will be easier to remind the other, “I think you are in the irritable stage right now. But let's think, is it for me or for the war and for Putin, who unleashed this war?

Plan. It will be useful to plan the day and prescribe a routine. Not necessarily in the format of a timetable, because the plan depends on the conditions in which you are. Conventionally, you can plan that after waking up, you will immediately go to brush your teeth, and not lie in bed for an hour, flipping through the news feed.

Conventionally, you can plan that after waking up, you will immediately go to brush your teeth, and not lie in bed for an hour, flipping through the news feed.

Efremova lists three tasks that must be completed during the day.

- Social task. We must communicate. This is very important, because in certain emotional waves we may want to separate from people. This can come either from the mood "I'm bad, I won't bother anyone with my experiences", or from "I'm offended, no one loves me." Whatever it is, we need to communicate with those with whom we feel good.

- Sports task. We should do something physically active: sit down, walk in circles, mop the floor.

- Cognitive task. It is important for us to learn something new every day, at least one foreign word, instructions for first aid or the use of weapons. “You need to be aware of this new information, and not look at it automatically, like a news feed,” Efremova notes.

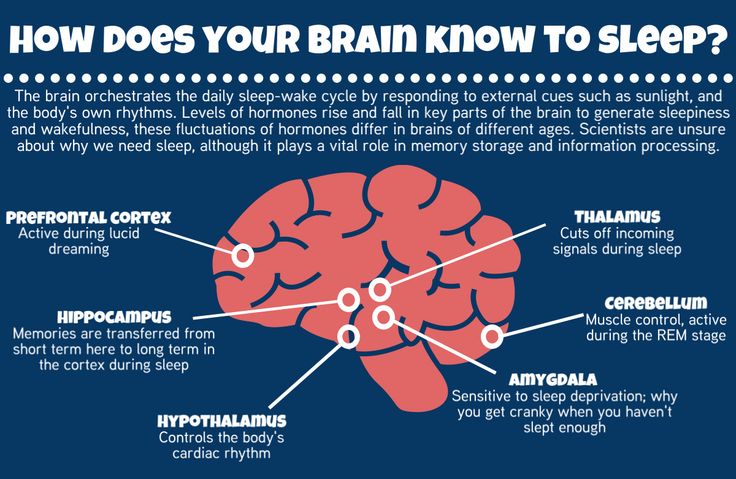

So we gradually load the memory, and this is necessary both for the activation of the prefrontal cortex and for the prevention of PTSD.

So we gradually load the memory, and this is necessary both for the activation of the prefrontal cortex and for the prevention of PTSD.

Remember your own values. They help you keep going and do your job no matter what. “Even in a state of apathy, which is now the most urgent for us, it is important to do what we have planned,” says the psychologist. – Even if the values are not visible, they are there, they do not disappear. This is what we live by.

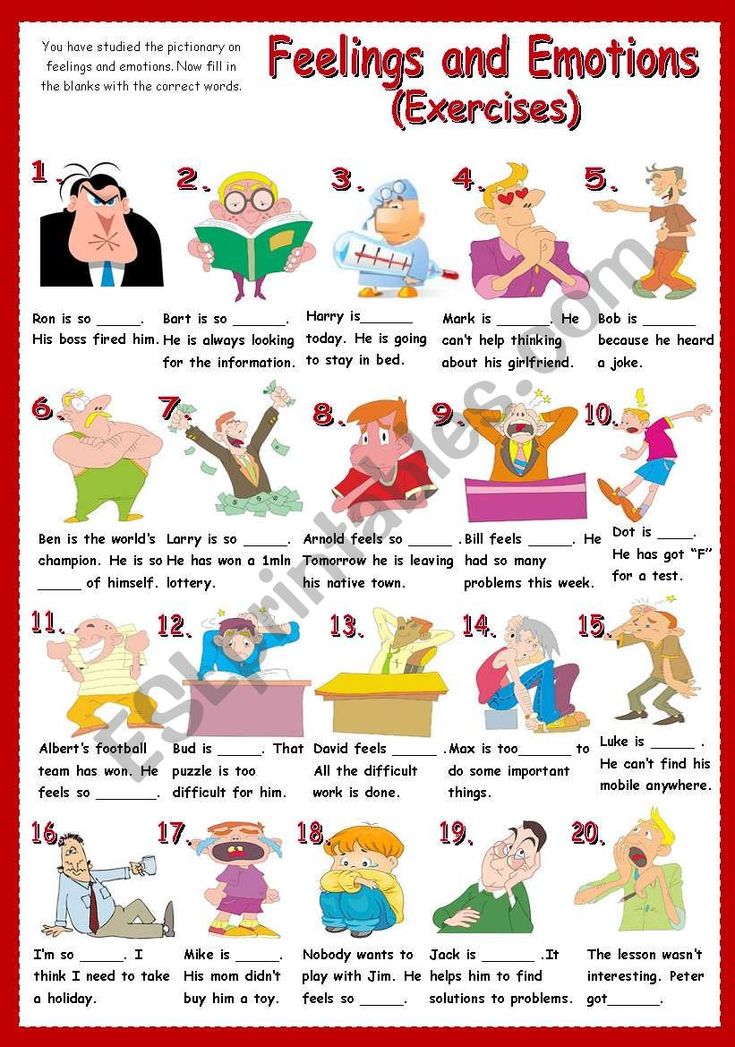

How to manage feelings in different phases of the "emotional swing"

Depressive symptoms phase

This is the most difficult of the stages: you can get stuck in it for a long time. “Depressive symptoms are an absolutely physiological and normal phase, because we run out of neurotransmitters and strength,” says the psychologist.

In a strategy to overcome apathy, the balance of two components is important. On the one hand, if possible, you need to sleep, wash, eat and rest. On the other hand, rest should not be confused with the desire to lie in a corner and look at the wall. “We rested, slept and went to do business,” calls Efremova.

On the other hand, rest should not be confused with the desire to lie in a corner and look at the wall. “We rested, slept and went to do business,” calls Efremova.

It is important not to remain in apathy, not to go deep into it. “If you see that you don’t want anything but curl up, don’t wait for motivation and the moment when you finally want to,” notes the psychologist. Instead, you need to do simple useful tasks on an alarm clock that will help you take care of yourself and your loved ones: wash dishes, cook food, comb your hair, wash your face.

It is also necessary to pull loved ones out of apathetic states. The formula will help: “I understand that you don’t want to, but please wash the dishes - there is no one but you. You will do this task - and it will become easier for you.

“It is worth doing what someone knows how to do: who advises, who prepares dinner, who, relatively speaking, washes the tank,” adds the psychologist. This gives a sense of usefulness and belonging to the community.

Phase of panic, anxiety, fear

It will be useful to master breathing exercises and try to breathe in a “square”: inhale for four counts, pause for four counts, exhale for four counts, pause for four counts. Efremova also recommends drinking water and communicating with loved ones.

A separate scenario is useful if a person is in a state of crisis and shock, when emotions are running high. “One of the tasks in the case of such acute emotions is not to discuss the emotional state, not to ask questions like “How are you feeling right now?” This is very important, ”Efremova notes. What will help?

Physical exercises:

- when emotions are running high, do a breathing exercise with an emphasis on a long exhalation. This will be effective in both severe stress and moderate;

- If the person next to you or you yourself is literally shaking from stress, Efremova advises not to stop it, but rather to consciously increase it.

“If, say, your hands are shaking a little, you need to shake them from the very shoulder. It’s the same with the legs, and with the shoulders – figuratively speaking, this is how we try to shake out the stress.”

“If, say, your hands are shaking a little, you need to shake them from the very shoulder. It’s the same with the legs, and with the shoulders – figuratively speaking, this is how we try to shake out the stress.”

In case of panic and a storm of emotions, a person next to him can start a dialogue. It is worth saying things like: “Hear my voice”, “What is your name?”, “Tell me what you see around you?” etc. “In this state, you need to try to ground people - this is very useful,” says Efremova. Ask him to name five blue objects in his field of vision, ask what sounds and smells he can distinguish around him.

What to do if you yourself are in this state? Breathing exercises and grounding practices will also help: remind yourself who you are, where you are, what color the walls are, name your five favorite football teams or movies. “You can even just open a list of psychological tips and do them according to the instructions,” the psychologist advises. If there is no one near you who can help, there are psychologists and hotlines working online.

A storm of emotions and stress can leave behind palpable muscle tension and spasm. To combat this, progressive muscle relaxation exercises can be done. To do this, you must first inhale shallowly, strain your body while inhaling, hold your breath and tension for 2-3 seconds, and then release with exhalation. It helps to relax and fall asleep if you have trouble sleeping;

Annoyance phase

“Anger is a very powerful and useful emotion. It is important to direct it rationally,” emphasizes Efremova. This means not getting angry at relatives sitting next to each other in the bunker, but thinking about what can be done using anger: for example, help dig a trench, reach the hedgehog to the middle of the street, carry water to everyone in the shelter. Anger is, in a sense, strength. The challenge is to remind ourselves of this and make something useful out of that power while it lasts.

The euphoria phase

The euphoria phase will not last long and it is important to use it constructively.