Vitamin c depression

SAMHSA’s National Helpline | SAMHSA

Your browser is not supported

Switch to Chrome, Edge, Firefox or Safari

Main page content

-

SAMHSA’s National Helpline is a free, confidential, 24/7, 365-day-a-year treatment referral and information service (in English and Spanish) for individuals and families facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

Also visit the online treatment locator.

SAMHSA’s National Helpline, 1-800-662-HELP (4357) (also known as the Treatment Referral Routing Service), or TTY: 1-800-487-4889 is a confidential, free, 24-hour-a-day, 365-day-a-year, information service, in English and Spanish, for individuals and family members facing mental and/or substance use disorders.

This service provides referrals to local treatment facilities, support groups, and community-based organizations.

Also visit the online treatment locator, or send your zip code via text message: 435748 (HELP4U) to find help near you. Read more about the HELP4U text messaging service.

The service is open 24/7, 365 days a year.

English and Spanish are available if you select the option to speak with a national representative. Currently, the 435748 (HELP4U) text messaging service is only available in English.

In 2020, the Helpline received 833,598 calls. This is a 27 percent increase from 2019, when the Helpline received a total of 656,953 calls for the year.

The referral service is free of charge. If you have no insurance or are underinsured, we will refer you to your state office, which is responsible for state-funded treatment programs. In addition, we can often refer you to facilities that charge on a sliding fee scale or accept Medicare or Medicaid. If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

If you have health insurance, you are encouraged to contact your insurer for a list of participating health care providers and facilities.

The service is confidential. We will not ask you for any personal information. We may ask for your zip code or other pertinent geographic information in order to track calls being routed to other offices or to accurately identify the local resources appropriate to your needs.

No, we do not provide counseling. Trained information specialists answer calls, transfer callers to state services or other appropriate intake centers in their states, and connect them with local assistance and support.

-

Suggested Resources

What Is Substance Abuse Treatment? A Booklet for Families

Created for family members of people with alcohol abuse or drug abuse problems. Answers questions about substance abuse, its symptoms, different types of treatment, and recovery. Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.

Addresses concerns of children of parents with substance use/abuse problems.It's Not Your Fault (NACoA) (PDF | 12 KB)

Assures teens with parents who abuse alcohol or drugs that, "It's not your fault!" and that they are not alone. Encourages teens to seek emotional support from other adults, school counselors, and youth support groups such as Alateen, and provides a resource list.After an Attempt: A Guide for Taking Care of Your Family Member After Treatment in the Emergency Department

Aids family members in coping with the aftermath of a relative's suicide attempt. Describes the emergency department treatment process, lists questions to ask about follow-up treatment, and describes how to reduce risk and ensure safety at home.Family Therapy Can Help: For People in Recovery From Mental Illness or Addiction

Explores the role of family therapy in recovery from mental illness or substance abuse. Explains how family therapy sessions are run and who conducts them, describes a typical session, and provides information on its effectiveness in recovery.

For additional resources, please visit the SAMHSA Store.

Last Updated: 08/30/2022

High Vitamin C Status Is Associated with Elevated Mood in Male Tertiary Students

1. Blanchflower D.G., Oswald A.J., Stewart-Brown S. Is Psychological Well-Being Linked to the Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables? Soc. Indic. Res. 2013;114:785–801. doi: 10.1007/s11205-012-0173-y. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2. Conner T.S., Brookie K.L., Richardson A.C., Polak M.A. On carrots and curiosity: Eating fruit and vegetables is associated with greater flourishing in daily life. Br. J. Health Psychol. 2015;20:413–427. doi: 10.1111/bjhp.12113. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

3. Tsai A.C., Chang T.L., Chi S.H. Frequent consumption of vegetables predicts lower risk of depression in older Taiwanese—Results of a prospective population-based study. Public Health Nutr. 2012;15:1087–1092. doi: 10.1017/S1368980011002977. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

4. Bishwajit G., O’Leary D.P., Ghosh S., Sanni Y., Shangfeng T., Zhanchun F. Association between depression and fruit and vegetable consumption among adults in South Asia. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:15. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1198-1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Bishwajit G., O’Leary D.P., Ghosh S., Sanni Y., Shangfeng T., Zhanchun F. Association between depression and fruit and vegetable consumption among adults in South Asia. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17:15. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1198-1. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. Mujcic R., Oswald J. Evolution of Well-Being and Happiness After Increases in Consumption of Fruit and Vegetables. Am. J. Public Health. 2016;106:1504–1510. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303260. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Rooney C., McKinley M.C., Woodside J.V. The potential role of fruit and vegetables in aspects of psychological well-being: A review of the literature and future directions. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2013;72:420–432. doi: 10.1017/S0029665113003388. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. Kaplan B.J., Crawford S.G., Field C.J., Simpson J.S. Vitamins, minerals, and mood. Psychol. Bull. 2007;133:747–760. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.747. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Levine M., Conry-Cantilena C., Wang Y., Welch R.W., Washko P.W., Dhariwal K.R., Park J.B., Lazarev A., Graumlich J.F., King J., et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: Evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:3704–3709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Levine M., Conry-Cantilena C., Wang Y., Welch R.W., Washko P.W., Dhariwal K.R., Park J.B., Lazarev A., Graumlich J.F., King J., et al. Vitamin C pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers: Evidence for a recommended dietary allowance. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:3704–3709. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3704. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Crandon J.H., Lund C.C., Dill D.B. Experimental human scurvy. N. Engl. J. Med. 1940;223:353–369. doi: 10.1056/NEJM194009052231001. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. Englard S., Seifter S. The biochemical functions of ascorbic acid. Annu. Rev. Nutr. 1986;6:365–406. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nu.06.070186.002053. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

11. Delgado P.L. Depression: The case for a monoamine deficiency. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2000;61:7–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

12. Du J., Cullen J.J., Buettner G.R. Ascorbic acid: Chemistry, biology and the treatment of cancer. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1826:443–457. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.06.003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2012.06.003. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Minor E.A., Court B.L., Young J.I., Wang G. Ascorbate induces ten-eleven translocation (Tet) methylcytosine dioxygenase-mediated generation of 5-hydroxymethylcytosine. J. Biol. Chem. 2013;288:13669–13674. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C113.464800. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Blaschke K., Ebata K.T., Karimi M.M., Zepeda-Martinez J.A., Goyal P., Mahapatra S., Tam A., Laird D.J., Rao A., Lorincz M.C., et al. Vitamin C induces Tet-dependent DNA demethylation and a blastocyst-like state in ES cells. Nature. 2013;500:222–226. doi: 10.1038/nature12362. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Zhang T.Y., Meaney M.J. Epigenetics and the environmental regulation of the genome and its function. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2010;61:439–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163625. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. Lindblad M., Tveden-Nyborg P. , Lykkesfeldt J. Regulation of vitamin C homeostasis during deficiency. Nutrients. 2013;5:2860–2879. doi: 10.3390/nu5082860. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Lykkesfeldt J. Regulation of vitamin C homeostasis during deficiency. Nutrients. 2013;5:2860–2879. doi: 10.3390/nu5082860. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Hornig D. Distribution of ascorbic acid, metabolites and analogues in man and animals. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1975;258:103–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1975.tb29271.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

18. Hughes R.E., Hurley R.J., Jones P.R. The retention of ascorbic acid by guinea-pig tissues. Br. J. Nutr. 1971;6:433–438. doi: 10.1079/BJN19710048. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Vissers M.C., Bozonet S.M., Pearson J.F., Braithwaite L.J. Dietary ascorbate intake affects steady state tissue concentrations in vitamin C-deficient mice: Tissue deficiency after suboptimal intake and superior bioavailability from a food source (kiwifruit) Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2011;93:292–301. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.110.004853. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Gariballa S. Poor vitamin C status is associated with increased depression symptoms following acute illness in older people. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2014;84:12–17. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831/a000188. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2014;84:12–17. doi: 10.1024/0300-9831/a000188. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Cheraskin E., Ringsdorf W.M., Jr., Medford F.H. Daily vitamin C consumption and fatigability. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 1976;24:136–137. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1976.tb04284.x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Prohan M., Amani R., Nematpour S., Jomehzadeh N., Haghighizadeh M.H. Total antioxidant capacity of diet and serum, dietary antioxidant vitamins intake, and serum hs-CRP levels in relation to depression scales in university male students. Redox Rep. 2014;19:133–139. doi: 10.1179/1351000214Y.0000000085. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. De Oliveira I.J., de Souza V.V., Motta V., Da-Silva S.L. Effects of Oral Vitamin C Supplementation on Anxiety in Students: A Double-Blind, Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 2015;18:11–18. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2015.11.18. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Wang Y. , Liu X.J., Robitaille L., Eintracht S., MacNamara E., Hoffer L.J. Effects of vitamin C and vitamin D administration on mood and distress in acutely hospitalized patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013;98:705–711. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.056366. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Liu X.J., Robitaille L., Eintracht S., MacNamara E., Hoffer L.J. Effects of vitamin C and vitamin D administration on mood and distress in acutely hospitalized patients. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2013;98:705–711. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.056366. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Carr A.C., Bozonet S.M., Pullar J.M., Vissers M.C. Mood improvement in young adult males following supplementation with gold kiwifruit, a high-vitamin C food. J. Nutr. Sci. 2013;2:e24. doi: 10.1017/jns.2013.12. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Huck C.J., Johnston C.S., Beezhold B.L., Swan P.D. Vitamin C status and perception of effort during exercise in obese adults adhering to a calorie-reduced diet. Nutrition. 2013;29:42–45. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2012.01.021. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Zhang M., Robitaille L., Eintracht S., Hoffer L.J. Vitamin C provision improves mood in acutely hospitalized patients. Nutrition. 2011;27:530–533. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2010.05. 016. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

016. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. McNair D., MaH J.W.P. Profile of Mood States Technical Update. North Tonawnada; New York, NY, USA: 2005. [Google Scholar]

29. Carr A.C., Pullar J.M., Moran S., Vissers M.C. Bioavailability of vitamin C from kiwifruit in non-smoking males: Determination of ‘healthy’ and ‘optimal’ intakes. J. Nutr. Sci. 2012;1:e14. doi: 10.1017/jns.2012.15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Carr A.C., Bozonet S.M., Pullar J.M., Simcock J.W., Vissers M.C. A randomized steady-state bioavailability study of synthetic versus natural (kiwifruit-derived) vitamin C. Nutrients. 2013;5:3684–3695. doi: 10.3390/nu5093684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Lykkesfeldt J., Poulsen H.E. Is vitamin C supplementation beneficial? Lessons learned from randomised controlled trials. Br. J. Nutr. 2010;103:1251–1259. doi: 10.1017/S0007114509993229. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. Bourre J.M. Effects of nutrients (in food) on the structure and function of the nervous system: Update on dietary requirements for brain. Part 1: Micronutrients. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2006;10:377–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Effects of nutrients (in food) on the structure and function of the nervous system: Update on dietary requirements for brain. Part 1: Micronutrients. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2006;10:377–385. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

33. Gomez-Pinilla F. Brain foods: The effects of nutrients on brain function. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2008;9:568–578. doi: 10.1038/nrn2421. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. Kaplan B.J., Fisher J.E., Crawford S.G., Field C.J., Kolb B. Improved mood and behavior during treatment with a mineral-vitamin supplement: An open-label case series of children. J. Child Adolesc. Psychopharmacol. 2004;14:115–122. doi: 10.1089/104454604773840553. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

35. Rucklidge J.J., Eggleston M.J.F., Johnstone J.M., Darling K., Frampton C.M. Vitamin-mineral treatment improves aggression and emotional regulation in children with ADHD: A fully blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry. 2018;59:232–246. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12817. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12817. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

36. Rucklidge J., Taylor M., Whitehead K. Effect of micronutrients on behavior and mood in adults With ADHD: Evidence from an 8-week open label trial with natural extension. J. Atten. Disord. 2011;15:79–91. doi: 10.1177/1087054709356173. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

37. Sarris J., Logan A.C., Akbaraly T.N., Amminger G.P., Balanza-Martinez V., Freeman M.P., Hibbeln J., Matsuoka Y., Mischoulon D., Mizoue T., et al. Nutritional medicine as mainstream in psychiatry. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:271–274. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00051-0. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

38. Mischoulon D., Freeman M.P. Omega-3 fatty acids in psychiatry. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2013;36:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2012.12.002. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

39. Polak M.A., Richardson A.C., Flett J.A.M., Brookie K.L., Conner T.S. Measuring Mood: Considerations and Innovations for Nutrition Science. In: Dye L., Best T., editors. Nutrition for Brain Health and Cognitive Performance. Taylor Japan and Francis; London, UK: 2015. pp. 93–119. [Google Scholar]

In: Dye L., Best T., editors. Nutrition for Brain Health and Cognitive Performance. Taylor Japan and Francis; London, UK: 2015. pp. 93–119. [Google Scholar]

40. Diliberto E.J., Daniels A.J., Jr., Viveros O.H. Multicompartmental secretion of ascorbate and its dual role in dopamine beta-hydroxylation. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1991;54:1163S–1172S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/54.6.1163s. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

41. Hoehn S.K., Kanfer J.N. Effects of chronic ascorbic acid deficiency on guinea pig lysosomal hydrolase activities. J. Nutr. 1980;110:2085–2094. doi: 10.1093/jn/110.10.2085. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

42. Deana R., Bharaj B.S., Verjee Z.H., Galzigna L. Changes relevant to catecholamine metabolism in liver and brain of ascorbic acid deficient guinea-pigs. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1975;45:175–182. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

43. Bornstein S.R., Yoshida-Hiroi M., Sotiriou S., Levine M., Hartwig H.G., Nussbaum R.L., Eisenhofer G. Impaired adrenal catecholamine system function in mice with deficiency of the ascorbic acid transporter (SVCT2) FASEB J. 2003;17:1928–1930. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1167fje. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2003;17:1928–1930. doi: 10.1096/fj.02-1167fje. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

44. May J.M., Qu Z.C., Meredith M.E. Mechanisms of ascorbic acid stimulation of norepinephrine synthesis in neuronal cells. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;426:148–152. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.08.054. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

45. Kuzkaya N., Weissmann N., Harrison D.G., Dikalov S. Interactions of peroxynitrite, tetrahydrobiopterin, ascorbic acid, and thiols: Implications for uncoupling endothelial nitric-oxide synthase. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:22546–22554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302227200. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

46. May J.M. Vitamin C transport and its role in the central nervous system. Subcell. Biochem. 2012;56:85–103. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

47. Berk M., Williams L.J., Jacka F.N., O‘Neil A., Pasco J.A., Moylan S., Allen N.B., Stuart A.L., Hayley A.C., Byrne M.L., et al. So depression is an inflammatory disease, but where does the inflammation come from? BMC Med. 2013;11:200. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

2013;11:200. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-11-200. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

48. Udina M., Castellvi P., Moreno-Espana J., Navines R., Valdes M., Forns X., Langohr K., Sola R., Vieta E., Martin-Santos R. Interferon-induced depression in chronic hepatitis C: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Clin. Psychiatry. 2012;73:1128–1138. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12r07694. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

49. Zou W., Feng R., Yang Y. Changes in the serum levels of inflammatory cytokines in antidepressant drug-naive patients with major depression. PLoS ONE. 2018;13:e0197267. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197267. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

50. Jeon S.W., Kim Y.K. The role of neuroinflammation and neurovascular dysfunction in major depressive disorder. J. Inflamm. Res. 2018;11:179–192. doi: 10.2147/JIR.S141033. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

51. Liu T., Zhong S., Liao X., Chen J., He T., Lai S., Jia Y. A Meta-Analysis of Oxidative Stress Markers in Depression. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0138904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138904. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

A Meta-Analysis of Oxidative Stress Markers in Depression. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0138904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138904. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

52. Carr A.C., Rosengrave P.C., Bayer S., Chambers S., Mehrtens J., Shaw G.M. Hypovitaminosis C and vitamin C deficiency in critically ill patients despite recommended enteral and parenteral intakes. Crit Care. 2017;21:300. doi: 10.1186/s13054-017-1891-y. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

53. Carr A.C., Maggini S. Vitamin C and Immune Function. Nutrients. 2017;9:e1211. doi: 10.3390/nu9111211. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

54. Johnston C.S., Solomon R.E., Corte C. Vitamin C status of a campus population: College students get a C minus. J. Am. Coll. Health. 1998;46:209–213. doi: 10.1080/07448489809600224. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

55. Szczuko M., Seidler T., Stachowska E., Safranow K., Olszewska M., Jakubowska K., Gutowska I., Chlubek D. Influence of daily diet on ascorbic acid supply to students. Roczniki Państwowego Zakładu Higieny. 2014;65:213–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Influence of daily diet on ascorbic acid supply to students. Roczniki Państwowego Zakładu Higieny. 2014;65:213–220. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

56. Cahill L., Corey P.N., El-Sohemy A. Vitamin C deficiency in a population of young Canadian adults. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2009;170:464–471. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwp156. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

57. Pullar J.M., Bayer S., Carr A.C. Appropriate Handling, Processing and Analysis of Blood Samples Is Essential to Avoid Oxidation of Vitamin C to Dehydroascorbic Acid. Antioxidants. 2018;7:29. doi: 10.3390/antiox7020029. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7 vitamins to help cope with the autumn blues - Bobruisk news portal Bobrlife

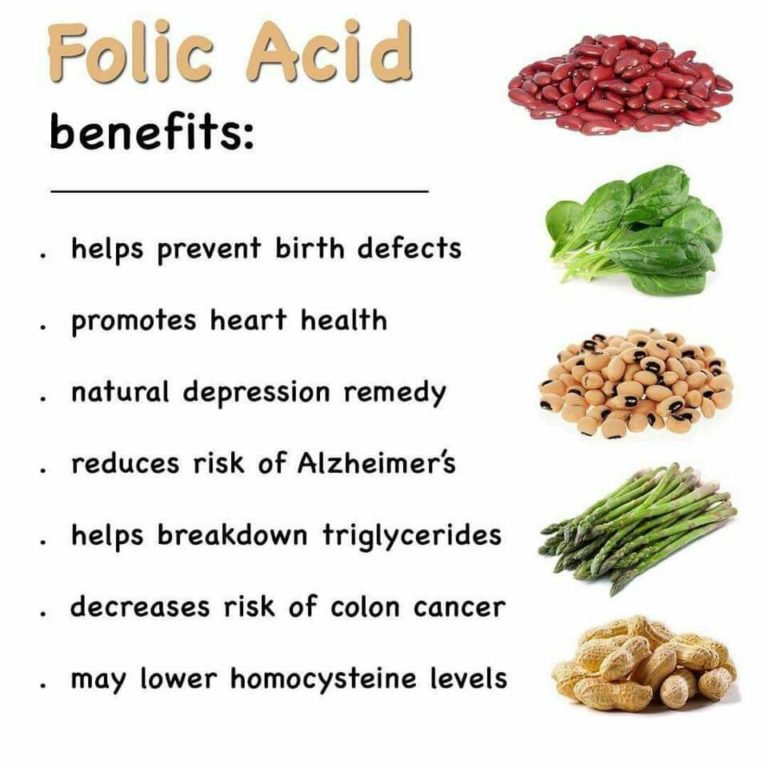

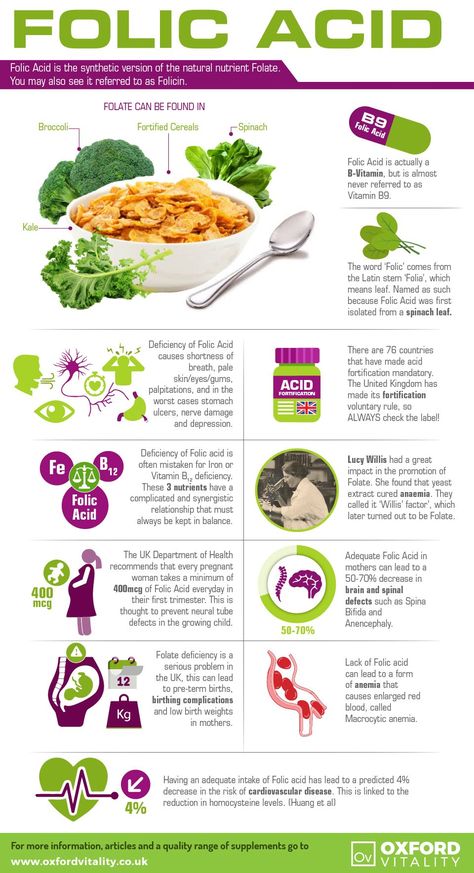

FOLIC ACID:

Deficiency of this representative of vitamins leads to low levels of serotonin in the brain - a substance important for maintaining a happy and contented mood. Folic acid is found in foods such as: watermelon, melon, tomatoes, citrus fruits (oranges, tangerines, grapefruits, lemons, etc. ), apples, pears, grapes, pomegranates, apricots, sea buckthorn, currants, avocados, bananas, kiwi, fresh dates, pumpkin, green and leafy vegetables (celery, lettuce, onions, spinach, asparagus, cucumbers, cabbage - cabbage, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, etc.), legume sprouts (soybeans, beans, chickpeas, lentils, etc.) and whole grain products (wheat, green buckwheat, etc.), nuts, peanuts, sunflower germinated grains, chestnuts, root crops (carrots, beets, turnips, etc.) and other plant products.

), apples, pears, grapes, pomegranates, apricots, sea buckthorn, currants, avocados, bananas, kiwi, fresh dates, pumpkin, green and leafy vegetables (celery, lettuce, onions, spinach, asparagus, cucumbers, cabbage - cabbage, cauliflower, Brussels sprouts, broccoli, etc.), legume sprouts (soybeans, beans, chickpeas, lentils, etc.) and whole grain products (wheat, green buckwheat, etc.), nuts, peanuts, sunflower germinated grains, chestnuts, root crops (carrots, beets, turnips, etc.) and other plant products.

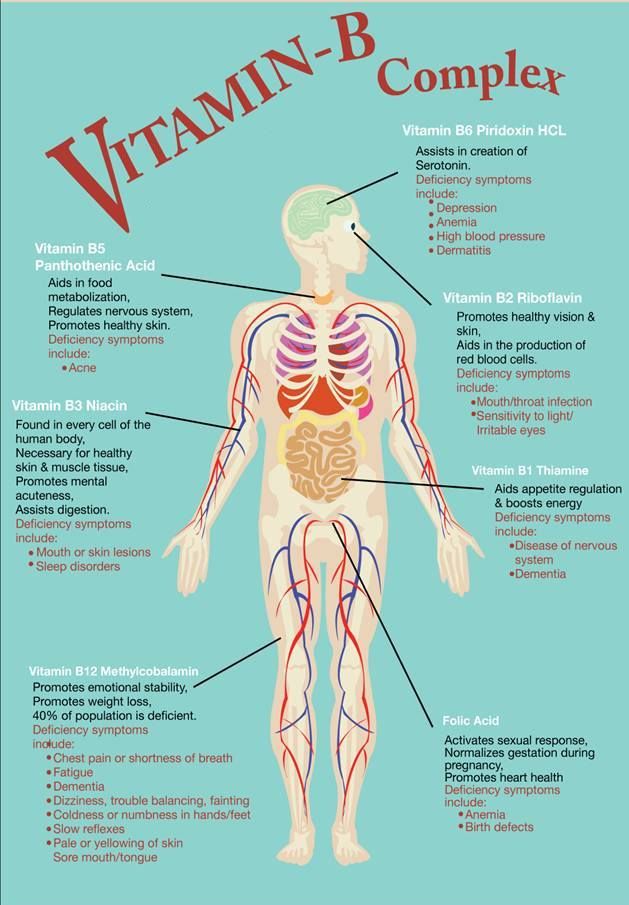

VITAMIN B6:

Serotonin production also requires vitamin B6. It is of the greatest importance in the regulation of emotional disorders, therefore it is most often included in the groups of vitamins that are associated with depression and are used to treat it. Most of all, vitamin B6 is contained, as well as the rest of the B vitamins, found in yeast, liver, sprouted wheat, bran and unrefined grains. There is a lot of it in potatoes (220 - 230 mcg / 100 g), molasses, bananas, pork, raw egg yolk, cabbage, carrots and dry beans (550 mcg / 100 g), walnuts and hazelnuts, peanuts and sunflower seeds. Rich sources of vitamin B6 are: chicken meat, fish; from cereals - buckwheat, bran and flour from unrefined grains. When you bake pies, you should replace at least 10% of the flour with bran!

Rich sources of vitamin B6 are: chicken meat, fish; from cereals - buckwheat, bran and flour from unrefined grains. When you bake pies, you should replace at least 10% of the flour with bran!

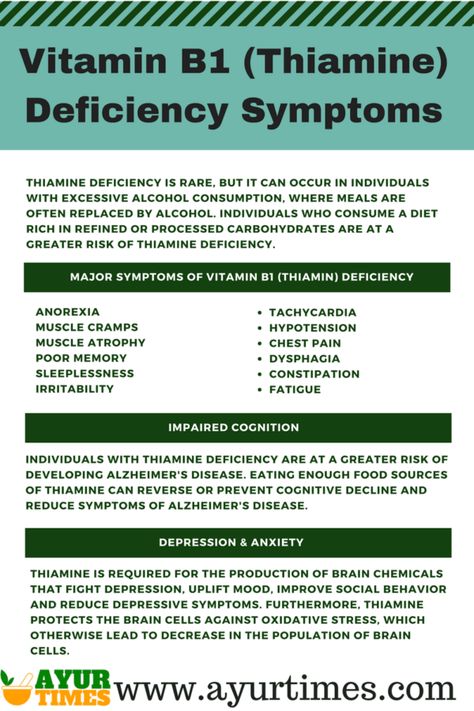

VITAMIN B1:

Vitamin B1 is necessary for the stimulation of the nervous system, it is also involved in the metabolism of carbohydrates, which provides both mental and physical energy. Deficiency symptoms include mood disorders, anxiety, insomnia, restlessness, and night terrors. This vitamin can be obtained from foods such as: brewer's yeast, sprouted wheat grains, bran, liver - the richest sources of vitamin B1. Sunflower seeds and sesame seeds are also rich in thiamine. Raw oatmeal is also recommended. Quite a lot of this vitamin is in beans and potatoes if the potatoes are baked or steamed. Vitamin B1 is found in black bread, pork entrails, rice, buckwheat, asparagus, leafy greens (parsley, dill, cilantro, lettuce, spinach and beet tops), hazelnuts, dried fruits and other foods.

VITAMIN B3:

Vitamin B3 is to the brain what calcium is to the bones. Vitamin B3 deficiency is associated with anxious depression. Its reception helps with increased irritability and other mental disorders. B3 is found in all foods that contain other B vitamins, but in different quantities (meat, kidneys, liver, dairy products). For example, in 100 g of liver it is about 14 mg, in 100 g of tuna - about 19 mg. Turkey meat is especially rich in them. There is a lot of B3 in sunflower seeds and ground nuts - peanuts (in 1 glass of roasted nuts - about 24 mg). A good source of vitamin B3 can be considered unrefined grains - germinated wheat, buckwheat, cereals from uncrushed cereals - oats, corn, rye, barley, and so on. In addition, they are rich in beans and peas, soybeans and mushrooms. But brewer's yeast is especially rich in vitamin B3.

VITAMIN E:

Responsible for mental and physical performance. The main food sources of vitamin E are the following foods: whole grain cereals, vegetable oils, eggs, lettuce, chestnuts, liver, nettle leaves, mint leaves, carrot tops, celery, asparagus, broccoli, bran. Vitamin E should be consumed in combination with vitamins A and C (butter, cream, egg yolk, sour milk, as well as vegetables - potatoes, cabbage, lettuce, carrots, green parts of plants).

Vitamin E should be consumed in combination with vitamins A and C (butter, cream, egg yolk, sour milk, as well as vegetables - potatoes, cabbage, lettuce, carrots, green parts of plants).

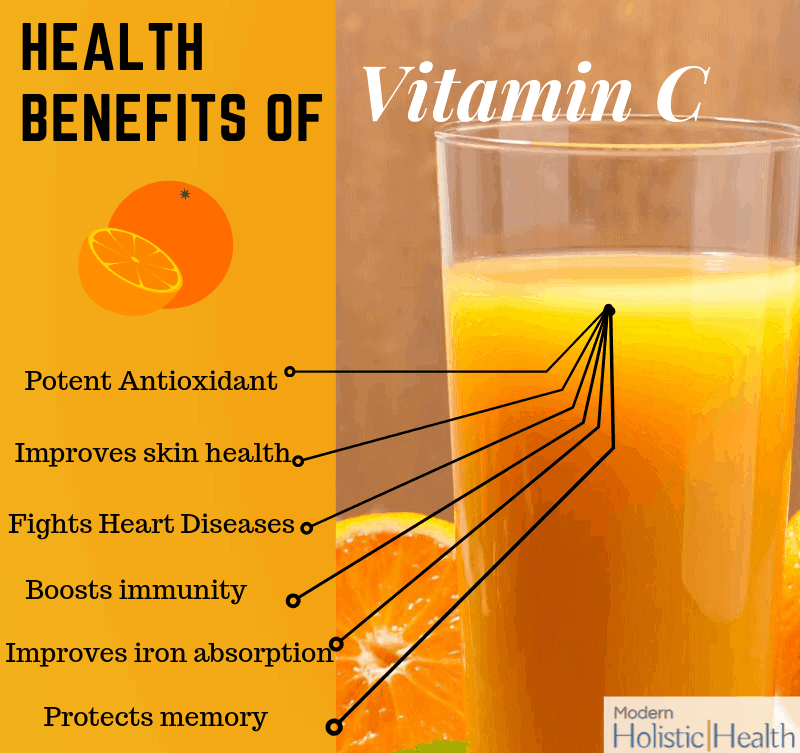

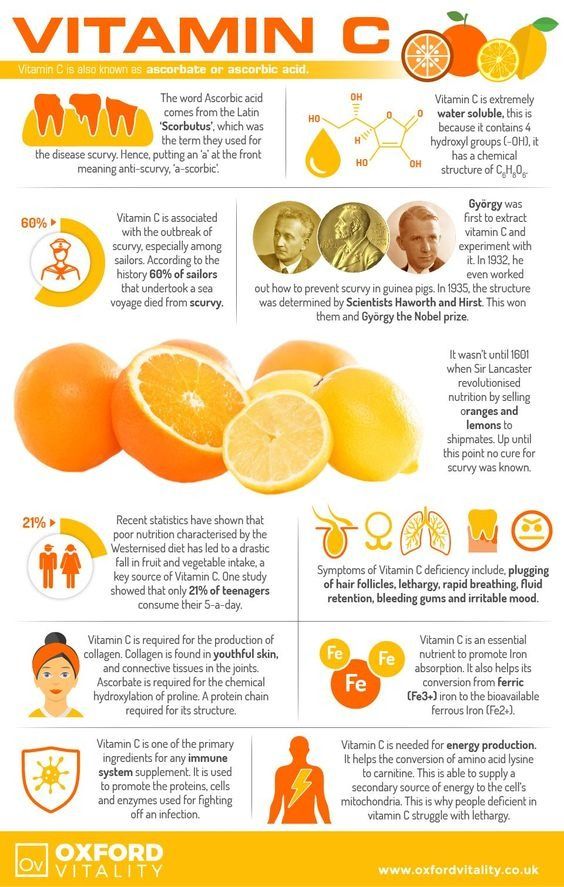

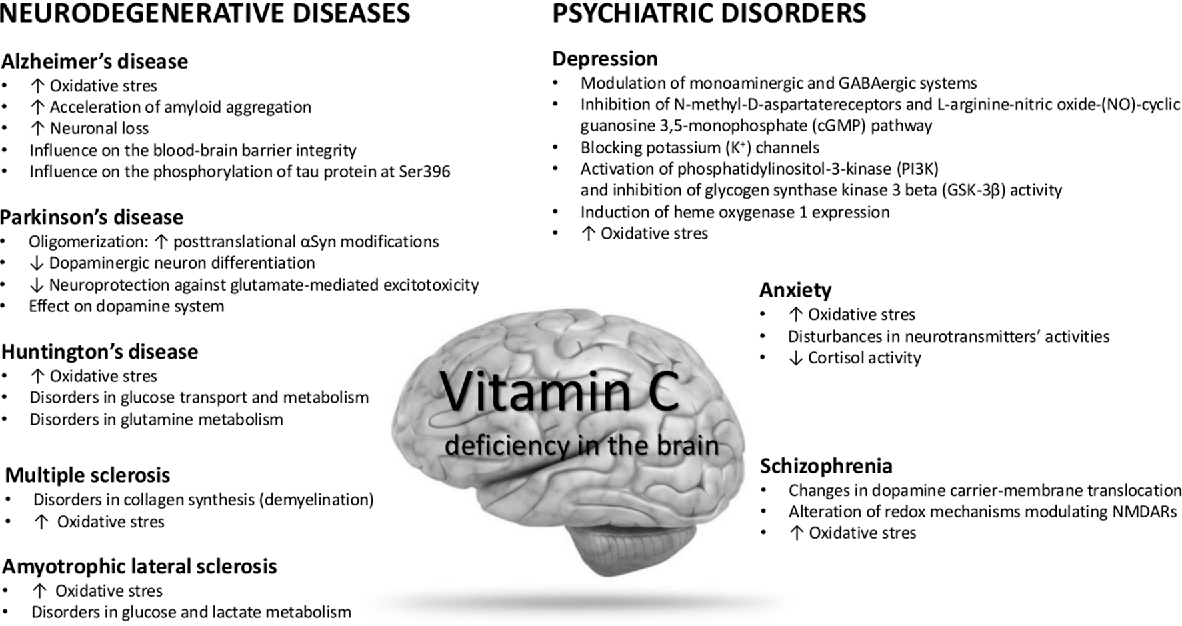

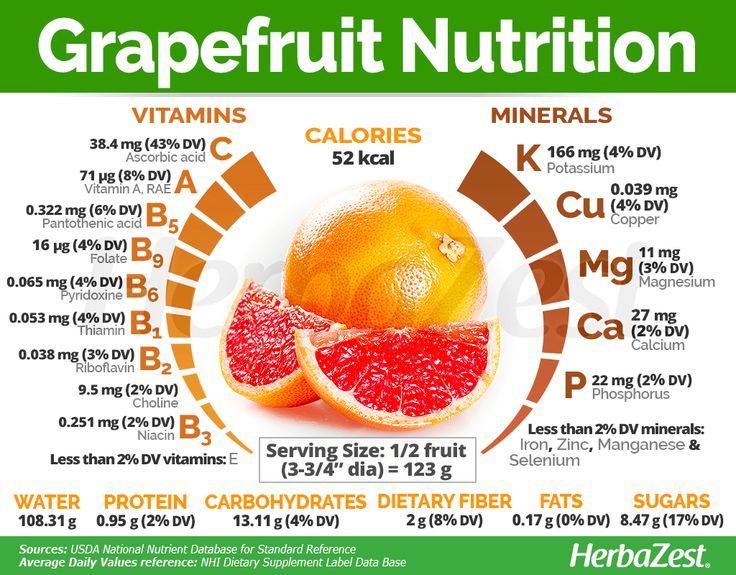

VITAMIN C:

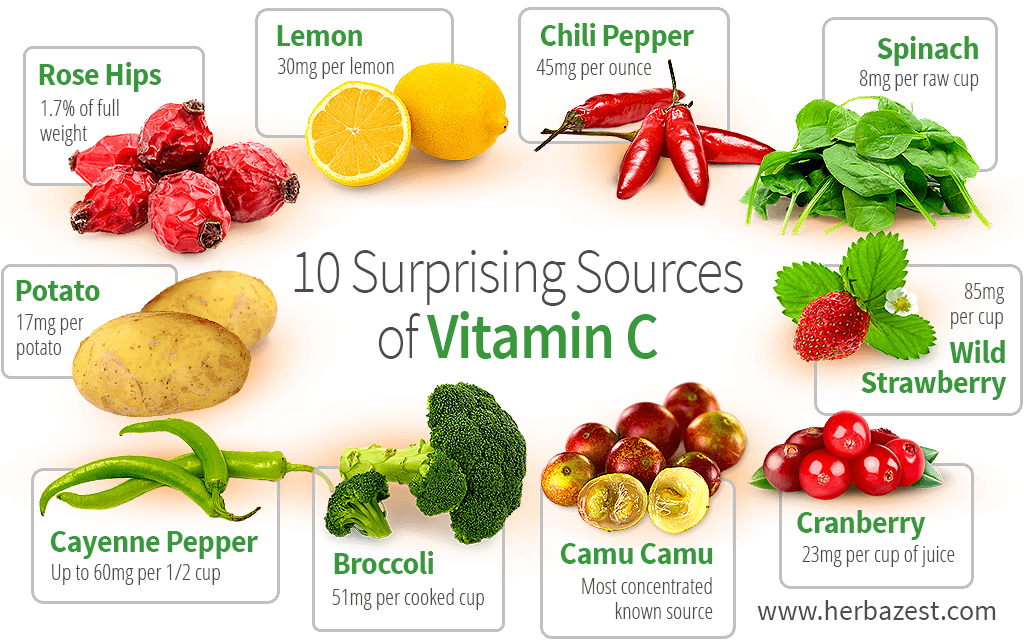

Those who lack ascorbic acid often complain of fatigue, drowsiness, depression. Scientists have not identified any connection between the lack of vitamin C and chronic fatigue, but it helps to increase efficiency and focus when tired. In addition, taking ascorbic acid increases the amount of adrenaline in the blood - it protects adrenaline from oxidation. Therefore, vitamin C is especially necessary for us to overcome stress more easily. In addition, it is a wonderful adaptogen: it prevents the development of the so-called maladjustment neurosis that occurs due to too short daylight hours - for example, in northern latitudes. Due to its properties as an adaptogen, it also accelerates the process of acclimatization during long-haul flights. A large amount of vitamin C is found in citrus fruits, rose hips, parsley, dill, black currants, green peas, red peppers, sea buckthorn berries, Brussels sprouts, red and cauliflower, strawberries, rowan berries. Its best absorption occurs in the presence of vitamin P (or rutin), which is found in rose hips, buckwheat, herbs and black currants.

Its best absorption occurs in the presence of vitamin P (or rutin), which is found in rose hips, buckwheat, herbs and black currants.

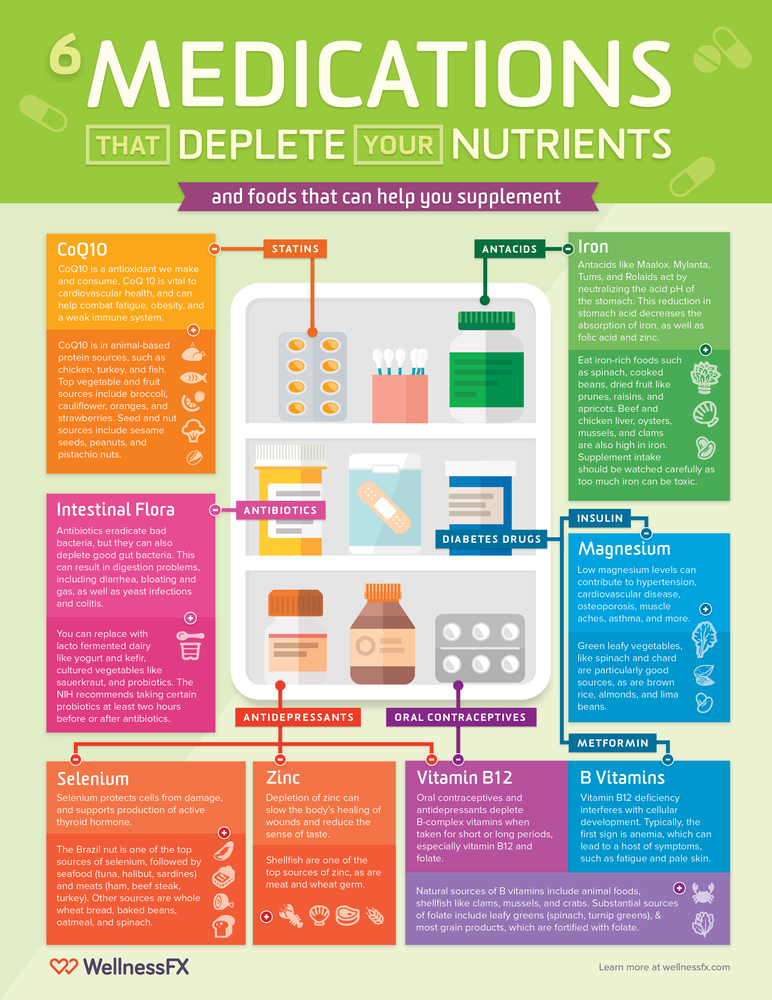

MAGNESIUM:

Scientists suggest that many cases of depression are the result of magnesium deficiency, which leads to extreme anxiety and stress. Other symptoms of low magnesium levels include high blood pressure, insomnia, brain fog, poor memory, sensation of a lump in the throat, ringing in the ears. The main sources of magnesium are: nuts (walnuts, hazelnuts, almonds), sesame seeds, some types of cereals (buckwheat, millet, and bran), baguettes and loaves with bran, apricots, peaches, raspberries, blackberries, strawberries, wild strawberries, ripe bananas, soybeans, white and red beans, lentils, potatoes, spinach, carrots. Spinach is best eaten raw. Magnesium is also found in animal products, especially meat and dairy products. To get enough magnesium, you should introduce lean meat (lean beef, turkey, chicken), cottage cheese, milk and kefir, soft cheeses into your daily diet. In addition, fish, especially fatty ones, such as Baltic herring, mackerel, horse mackerel, will also help to fill the lack of magnesium.

In addition, fish, especially fatty ones, such as Baltic herring, mackerel, horse mackerel, will also help to fill the lack of magnesium.

The best vitamins for depression and stress

Stress is the body's reaction to the impact of negative external factors.

Every person has had to deal with various stresses (emotional or physical). Someone suffered because of parting with a loved one, someone was betrayed by a best friend, someone lost a prestigious job. There are many such situations. Everyone experiences stress differently. He tempers some people, makes them stronger, wiser. Others cannot cope with stress, fall into despair and are at the mercy of depression.

Most often, depression is a reactive or situational disorder. If negative emotions, depressed mood, apathy, feelings of worthlessness, decreased sexual activity, headaches, loss of appetite and insomnia do not disappear for more than two weeks, the help of a qualified doctor is needed.

But before you seek medical help, you can try to cope with depression yourself, unless, of course, it is caused by a mental illness.

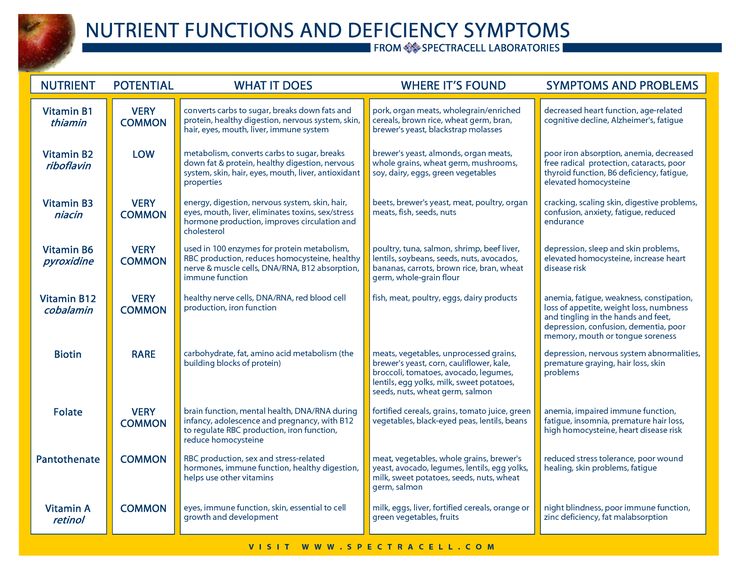

Prevention of side effects and the development of depression can be achieved through proper nutrition, the use of foods containing vitamins C, E, H, B vitamins, folic acid and other important substances.

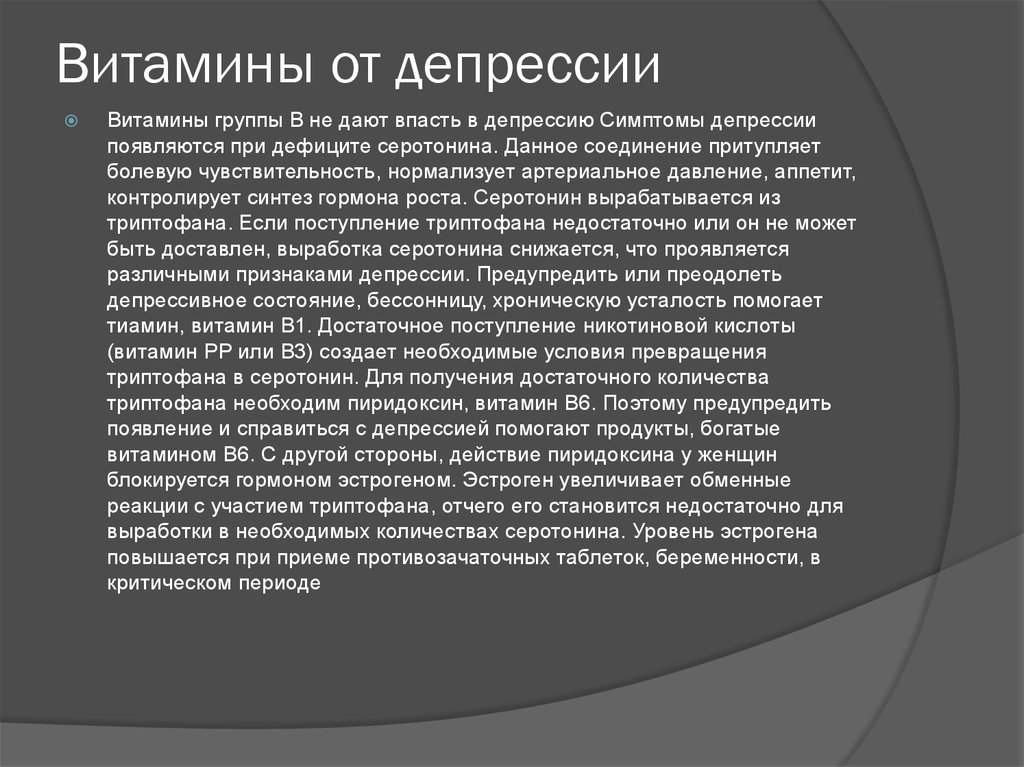

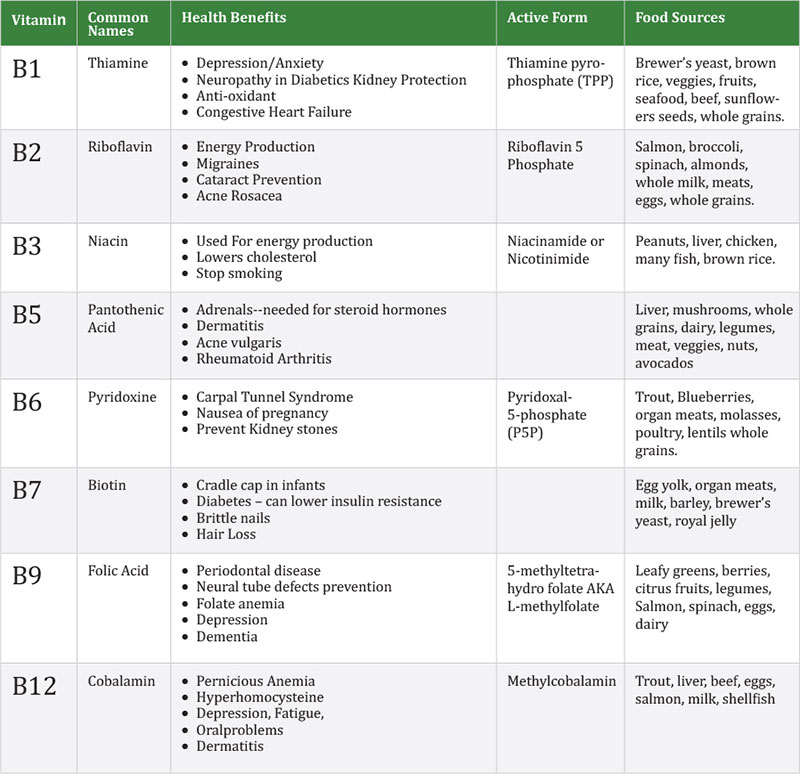

B vitamins

The most powerful vitamins in the fight against depression are B vitamins.

They have a beneficial effect on nerve cells, strengthen the immune system, restore the cardiovascular system, help the body absorb nutrients and participate in the synthesis of important compounds.

This group consists of 8 elements that complement each other. Therefore, vitamin complexes for depression contain all 8 components of this group:

• B1 - thiamine

• B3 - niacin

• B5 - pantothenic acid

• B6 - pyridoxine

• B7 (vitamin H in some sources) - biotin

• B9 - folic acid

• B12 - cyanocobalamin.

The body receives them only from the outside, they are not synthesized by themselves.

Vitamins of this group are found in large quantities in pork and beef liver, chicken, flounder, eggs, nuts, potatoes, bananas, legumes, fish, bread, herbs, peppers, squids, dairy products, mackerel, cod, seeds, brown rice.

By consuming these products, a person can prevent the development of chronic fatigue.

Vitamin C

Vitamin C regulates the functions of the adrenal glands and is involved in the production of cortisol. This element strengthens nails, hair, restores the skin and thereby improves the appearance of a person. In addition, it is involved in the formation of bone tissue.

Vitamin C is most active in the presence of a sufficient amount of flavonoids, carotenoids and vitamin E.

The body does not synthesize this vitamin either. It is found in tomatoes, cauliflower, broccoli, red peppers, strawberries, watermelons, citrus fruits, and black currants.

Vitamin A

Vitamin A, known as the growth vitamin, has antioxidant properties. It helps to strengthen the immune system and maintain the health of the eyes, mucous membranes, prostate gland, uterus, lungs, and protects against respiratory diseases.

It helps to overcome emotional instability and chronic fatigue.

Natural sources of vitamin - carrots, pumpkins, tomatoes, red peppers, apples, apricots.

Vitamin E

Vitamin E (tocopherol) supports the proper functioning of internal organs, is responsible for the immune system and the production of sex hormones. In the people it is called the "female" vitamin and beauty vitamin.

It is found in spinach, lettuce, beets, tomatoes, asparagus, turnips, lard, eggs, nuts.

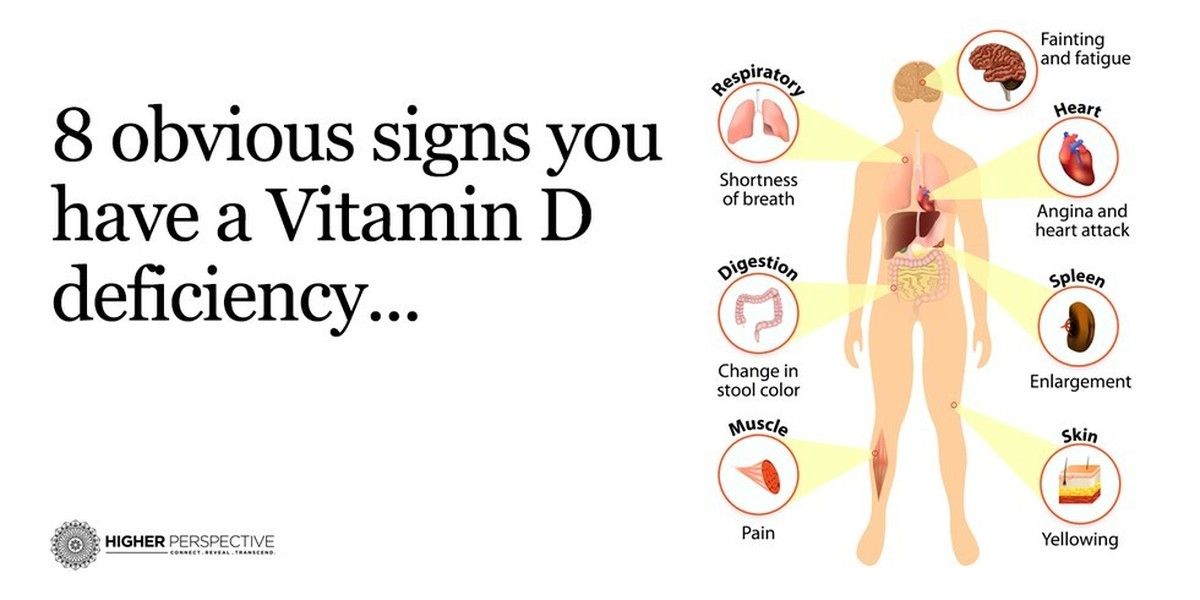

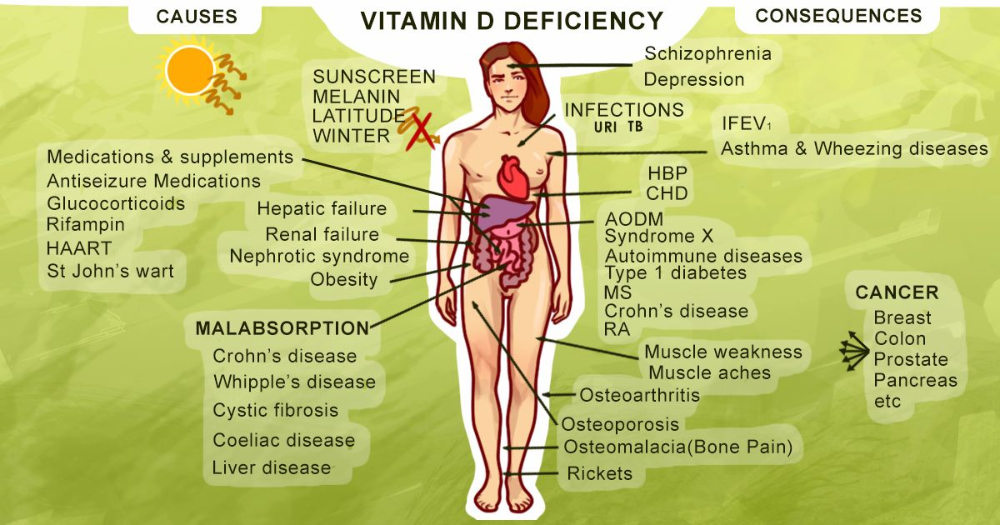

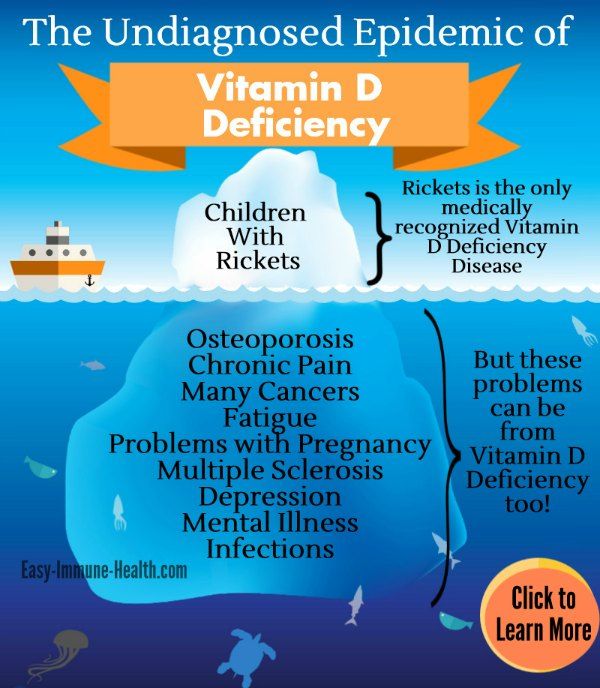

Vitamin D3

Vitamin D3 strengthens the nervous system, affects the state of the heart muscle, strengthens the immune system, helps maintain a normal emotional state. In addition, it is responsible for proper metabolism, restful and long sleep, emotional stability and reduced susceptibility to negative situations.

It is synthesized by the body when sunlight hits the skin. Included in butter, egg yolk, fish oil.

Biologically active substances

The human body is such a complex mechanism that in order to maintain it in a normal, healthy state, not only vitamins are needed, but also a huge number of various elements.

1. Among them, a special place is occupied by tryptophan, which enters the body with foods rich in carbohydrates and proteins. Tryptophan is found in dates, turkey meat, cheese, and bananas.

Tryptophan is an amino acid that is a precursor of serotonin. Its deficiency causes apathy and general depression.

2. Equally important is dopamine. Despite the fact that it is not a neurotransmitter (a special conductor of cells), it facilitates the transmission of nerve impulses. It is synthesized in the body from the amino acid tyrosine, which is found in bananas, beans, sesame seeds, homemade cheese, avocados, dairy products, and peanuts. Synthesis occurs with the participation of magnesium, vitamins B12 and B9.

3. Fatty acids are indispensable in the treatment of depressive disorders. They serve as a material for the synthesis of prostaglandins, which help maintain a good mood. A diet for depression should include sea fish, beef, spinach, walnuts, shrimp, as all these foods contain a lot of fatty acids.

4. Known to many, glycine is a building component, a neurotransmitter. It regulates metabolic processes, activates the processes of protective inhibition. Its deficiency leads to increased irritability, fatigue. The substance is synthesized within the body.

Depression and unhealthy nutrition

Both deficiency and excess of vitamins and minerals can cause depression. Thus, high levels of magnesium contribute to the development of persistent depressive disorder. A special blood test can be used to determine magnesium levels.

Contributes to the development of depression and the appearance of suicidal thoughts eating large amounts of fat. For this reason, nutrition in depression should be balanced, fatty meat should be replaced with lean protein found in dairy products, poultry meat, and fish.