Adhd and social cues

Relationships & Social Skills - CHADD

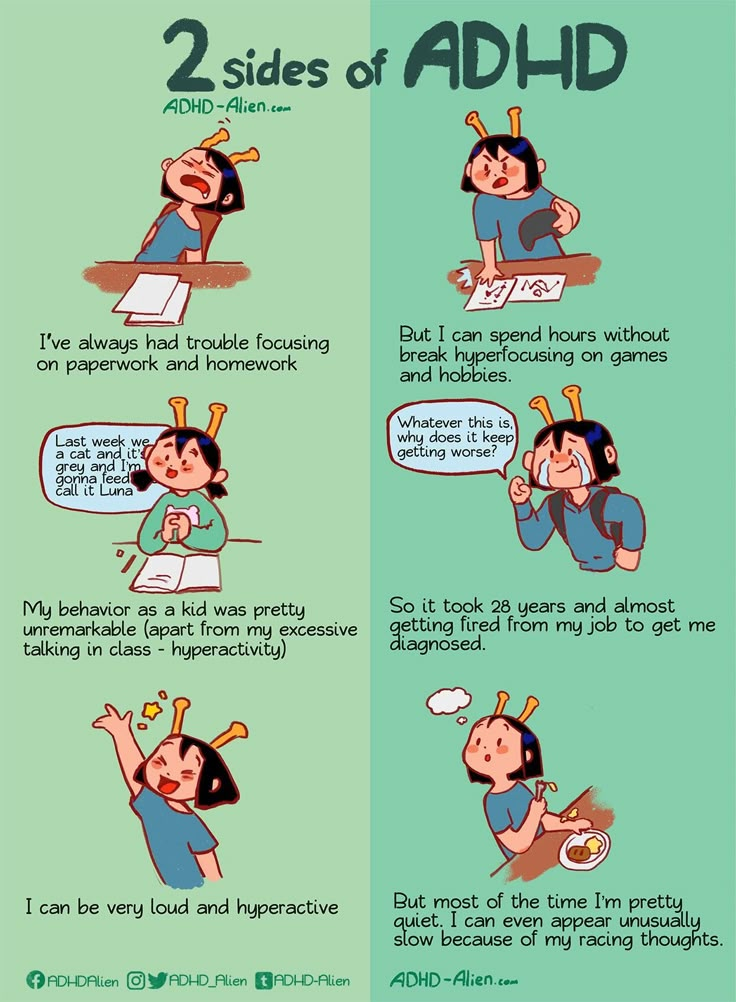

Individuals with ADHD exhibit behavior that is often seen as impulsive, disorganized, aggressive, overly sensitive, intense, emotional, or disruptive. Their social interactions with others in their social environment — parents, siblings, teachers, friends, co-workers, spouses/partners — are often filled with misunderstanding and mis-communication.

Those with ADHD have a decreased ability to self-regulate their actions and reactions toward others. This can cause relationships to be overly tense and fragile.

The topics in this section address some of the particular relationship issues faced by individuals with ADHD and others in their lives.

Social Skills in Adults with ADHD

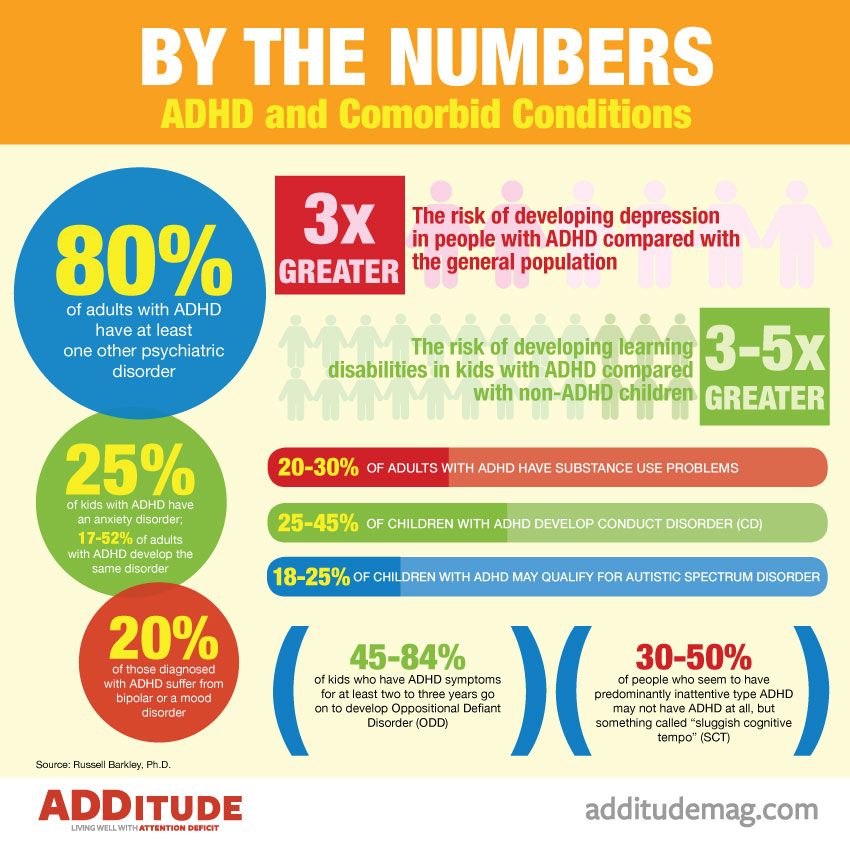

Individuals with ADHD often experience social difficulties, social rejection, and interpersonal relationship problems as a result of their inattention, impulsivity and hyperactivity. Such negative interpersonal outcomes cause emotional pain and suffering.

They also appear to contribute to the development of co-morbid mood and anxiety disorders.

Because very little research has been published regarding social skills in adults with ADHD, the suggestions given in this sheet are based primarily upon sound clinical practices and upward extrapolations from the research on children’s social skills and ADHD.

Overall impact of ADHD on social interactions

It is not difficult to understand the reasons why individuals with ADHD often struggle in social situations. Interacting successfully with peers and significant adults is one of the most important aspects of a child’s development, yet 50 to 60 percent of children with ADHD have difficulty with peer relationships. Over 25 percent of Americans experience chronic loneliness. One can only speculate that the figure is much higher for adults with ADHD.

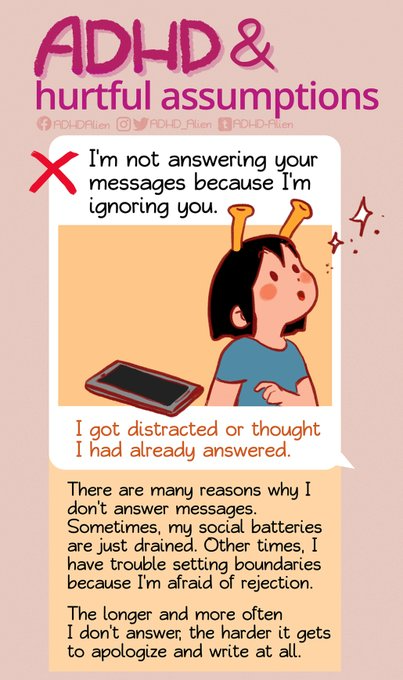

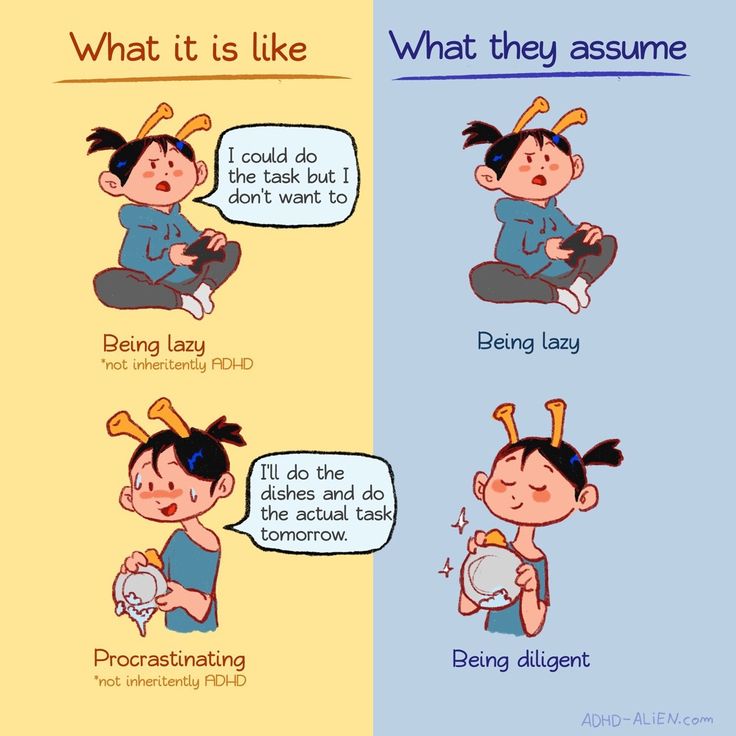

To interact effectively with others, an individual must be attentive, responsible and able to control impulsive behaviors. Adults with ADHD are often inattentive and forgetful and typically lack impulse control. Because ADHD is an “invisible disability,” often unrecognized by those who may be unfamiliar with the disorder, socially inappropriate behaviors that are the result of ADHD symptoms are often attributed to other causes. That is, people often perceive these behaviors and the individual who commits them as rude, self-centered, irresponsible, lazy, ill-mannered, and a host of other negative personality attributes. Over time, such negative labels lead to social rejection of the individual with ADHD. Social rejection causes emotional pain in the lives of many of the children and adults who have ADHD and can create havoc and lower self-esteem throughout the life span. In relationships and marriages, the inappropriate social behavior may anger the partner or spouse without ADHD, who may eventually “burn out” and give up on the relationship or marriage.

Adults with ADHD are often inattentive and forgetful and typically lack impulse control. Because ADHD is an “invisible disability,” often unrecognized by those who may be unfamiliar with the disorder, socially inappropriate behaviors that are the result of ADHD symptoms are often attributed to other causes. That is, people often perceive these behaviors and the individual who commits them as rude, self-centered, irresponsible, lazy, ill-mannered, and a host of other negative personality attributes. Over time, such negative labels lead to social rejection of the individual with ADHD. Social rejection causes emotional pain in the lives of many of the children and adults who have ADHD and can create havoc and lower self-esteem throughout the life span. In relationships and marriages, the inappropriate social behavior may anger the partner or spouse without ADHD, who may eventually “burn out” and give up on the relationship or marriage.

Educating individuals with ADHD, their significant others, and their friends about ADHD and the ways in which it affects social skills and interpersonal behaviors can help alleviate much of the conflict and blame. At the same time, the individual with ADHD needs to learn strategies to become as proficient as possible in the area of social skills. With proper assessment, treatment and education, individuals with ADHD can learn to interact with others effectively in a way that enhances their

At the same time, the individual with ADHD needs to learn strategies to become as proficient as possible in the area of social skills. With proper assessment, treatment and education, individuals with ADHD can learn to interact with others effectively in a way that enhances their

social life.

ADHD and the acquisition of social skills

Social skills are generally acquired through incidental learning: watching people, copying the behavior of others, practicing, and getting feedback. Most people start this process during early childhood. Social skills are practiced and honed by “playing grown-up” and through other childhood activities. The finer points of social interactions are sharpened by observation and peer feedback.

Children with ADHD often miss these details. They may pick up bits and pieces of what is appropriate but lack an overall view of social expectations. Unfortunately, as adults, they often realize “something” is missing but are never quite sure what that “something” may be.

Social acceptance can be viewed as a spiral going up or down. Individuals who exhibit appropriate social skills are rewarded with more acceptance from those with whom they interact and are encouraged to develop even better social skills. For those with ADHD, the spiral often goes downward. Their lack of social skills leads to peer rejection, which then limits opportunities to learn social skills, which leads to more rejection, and so on. Social punishment includes rejection, avoidance, and other, less subtle means of exhibiting one’s disapproval towards another person.

It is important to note that people do not often let the offending individual know the nature of the social violation. Pointing out that a social skill error is being committed is often considered socially inappropriate. Thus, people are often left on their own to try to improve their social skills without understanding exactly what areas need improvement.

Research on children with ADHD and social skills

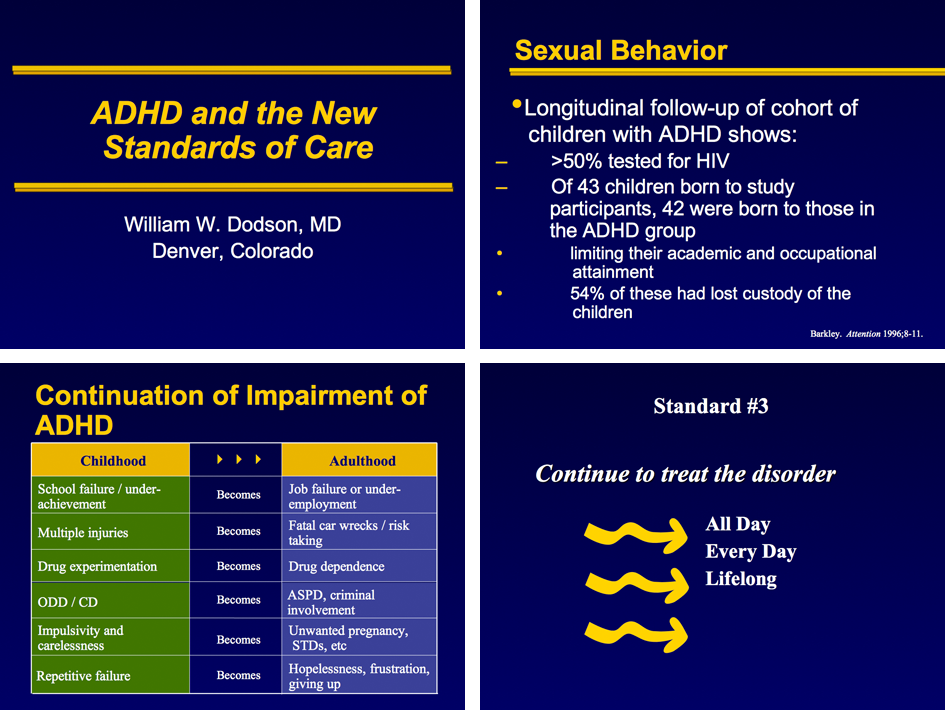

Researchers have found that the social challenges of children with ADHD include disturbed relationships with their peers, difficulty making and keeping friends, and deficiencies in appropriate social behavior. Long-term outcome studies suggest that these problems continue into adolescence and adulthood and impede the social adjustment of adults with ADHD.

Long-term outcome studies suggest that these problems continue into adolescence and adulthood and impede the social adjustment of adults with ADHD.

At first, these difficulties of children with ADHD were conceptualized as a deficit in appropriate social skills, such that the children had not acquired the appropriate social behaviors. Based upon this model, social skills training, which is commonly conducted with groups of children, became a widely accepted treatment modality. In the typical social skills training group, the therapist targets specific social behaviors, provides verbal instructions and demonstrations of the target behavior, and coaches the children to role-play the target behaviors with one another. The therapist also provides positive feedback and urges the group to provide positive feedback to one another for using the appropriate social behavior. The children are instructed to apply their newly acquired skills in their daily lives.

More recently, ADHD has been re-conceptualized as an impairment of the executive or controlling functions of the brain. It follows from this conceptualization that the social deficits of the individual with ADHD may not be primarily the result of a lack of social skills, but rather a lack of efficiency in reliably using social skills that have already been acquired. Social skills training addresses the lack of skills, but does not address inefficient use of existing skills. Medication produces direct changes in the executive function of the brain and may therefore help children with ADHD more reliably use newly acquired social skills. Researchers have also added components to social skills training that help children with ADHD reliably apply what they have learned in various settings. To accomplish this goal, parents and teachers are trained to prompt and reinforce children with ADHD to use newly acquired social skills at home and in school.

It follows from this conceptualization that the social deficits of the individual with ADHD may not be primarily the result of a lack of social skills, but rather a lack of efficiency in reliably using social skills that have already been acquired. Social skills training addresses the lack of skills, but does not address inefficient use of existing skills. Medication produces direct changes in the executive function of the brain and may therefore help children with ADHD more reliably use newly acquired social skills. Researchers have also added components to social skills training that help children with ADHD reliably apply what they have learned in various settings. To accomplish this goal, parents and teachers are trained to prompt and reinforce children with ADHD to use newly acquired social skills at home and in school.

Only a small number of controlled investigations have studied the effectiveness of social skills training for children with ADHD. These studies have found that social skills training improves the children’s knowledge of social skills and improves their social behavior at home as judged by parents, and these positive changes last up to the 3 or 4 month follow-up periods in the studies. However, these changes only partially generalize to school and other environments.

However, these changes only partially generalize to school and other environments.

Researchers have also found that embedding social skills training within an intensive behavioral intervention, such as a specialized summer camp program, is a highly effective way of increasing the chances that the children will maintain and generalize the gains that they have made. There is no research yet that addresses the question of whether children with ADHD who benefit from social skills training have more friends, are better accepted by their peers, and have better interpersonal relationships as they move into adolescence and adulthood. Clearly, this is an area where more research is necessary.

Specific ADHD symptoms and social skills

Inattention

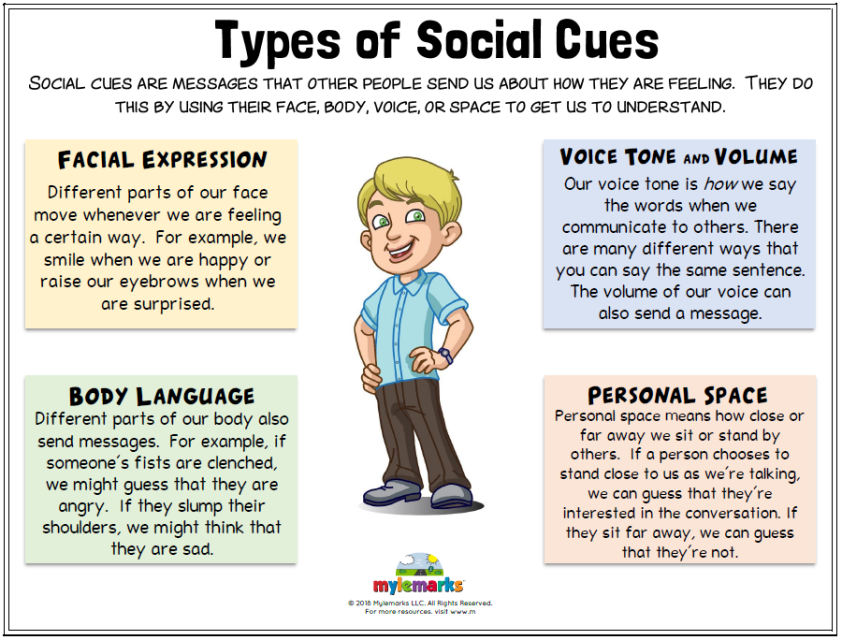

Tips for identifying subtext:

- Look for clues in your environment to help you decipher the subtext. Be mindful of alternative possibilities. Be observant.

- Be aware of body language, tone of voice, behavior, or the look of someone’s eyes to better interpret what they are saying.

- Look at a person’s choice of words to better detect the subtext. (“I’d love to go” probably means yes. “If you want to” means probably not, but I’ll do it.)

- Actions speak louder than words. If someone’s words say one thing but their actions reveal another, it would be wise to consider that their actions might be revealing their true feelings.

- Find a guide to help you with this hidden language. Compare your understanding of reality with their understanding of reality. If there is a discrepancy, you might want to try the other person’s interpretation and see what happens, especially if you usually get it wrong.

- Learn to interpret polite behavior. Polite behavior often disguises actual feelings.

- Be alert to what others are doing. Look around for clues about proper behavior, dress, seating, parking and the like.

- A momentary lapse in attention may result in the adult with ADHD missing important information in a social interaction. If a simple sentence like “Let’s meet at the park at noon,” becomes simply “Let’s meet at noon,” the listener with ADHD misses the crucial information about the location of the meeting.

The speaker may become frustrated or annoyed when the listener asks where the meeting will take place, believing that the listener intentionally wasn’t paying attention and didn’t value what they had to say. Or even worse, the individual with ADHD goes to the wrong place, yielding confusion and even anger in the partner. Unfortunately, often neither the speaker nor listener realizes that important information has been missed until it is too late.

The speaker may become frustrated or annoyed when the listener asks where the meeting will take place, believing that the listener intentionally wasn’t paying attention and didn’t value what they had to say. Or even worse, the individual with ADHD goes to the wrong place, yielding confusion and even anger in the partner. Unfortunately, often neither the speaker nor listener realizes that important information has been missed until it is too late.

A related social skills difficulty for many with ADHD involves missing the subtle nuances of communication. Those with ADHD will often have difficulty “reading between the lines” or understanding subtext. It is difficult enough for most to attend to the text of conversations without the additional strain of needing to be aware of the subtext and what the person really means . Unfortunately, what is said is often not what is actually meant.

Impulsivity

Impulsivity negatively affects social relationships because others may attribute impulsive words or actions to lack of caring or regard for others. Failure to stop and think first often has devastating social consequences. Impulsivity in speech, without self-editing what is about to be said, may appear as unfiltered thoughts. Opinions and thoughts are shared in their raw form, without the usual veneer that most people use to be socially appropriate. Interruptions are common.

Failure to stop and think first often has devastating social consequences. Impulsivity in speech, without self-editing what is about to be said, may appear as unfiltered thoughts. Opinions and thoughts are shared in their raw form, without the usual veneer that most people use to be socially appropriate. Interruptions are common.

Impulsive actions can also create difficulties as individuals with ADHD may act before thinking through their behavior. Making decisions based on an “in the moment” mentality often leads to poor decision-making. Those with ADHD often find themselves lured off task by something more inviting. Impulsive actions can include taking reckless chances, failure to study or prepare for school- or work-related projects, affairs, quitting jobs, making decisions to relocate, financial overspending, and even aggressive actions, such as hitting others or throwing items.

Rapid and excessive speech can also be a sign of impulsivity. The rapid-fire speech of an individual with ADHD leaves little room for others who might want to participate in the conversation. Monologues rather than dialogues leave many with ADHD without satisfying relationships or needed information.

Monologues rather than dialogues leave many with ADHD without satisfying relationships or needed information.

Hyperactivity

Physical hyperactivity often limits the ability to engage in leisure activities. Failure to sit still and concentrate for concerts, religious ceremonies, educational events, or even leisure vacations and the like may be interpreted by others as a lack of caring or concern on the part of the person with ADHD. In addition, difficulties lookingattentive leave others feeling unattended.

Assessment of social skills

Interviews and self-report questionnaires are the primary tools for assessing social skill deficits and interpersonal interaction problems in adults with ADHD. During the course of a diagnostic evaluation for ADHD (see What We Know #9, “Diagnosis of ADHD in Adults”), a mental health professional will thoroughly assess the social interactions of the adult. When questionnaires are used, it is important to include both a self-report by the individual with ADHD and reports by spouses, significant others, and friends on a comparable version of the questionnaire. The questionnaire may include the following types of items:

The questionnaire may include the following types of items:

- Difficulty paying attention when spoken to, missing pieces of information

- Appears to ignore others

- Difficulty taking turns in conversation (tendency to interrupt frequently)

- Difficulty following through on tasks and/or responsibilities

- Failure to use proper manners

- Missed social cues

- Disorganized lifestyle

- Sharing information that is inappropriate

- Being distracted by sounds or noises

- Become flooded or overwhelmed, shutting down

- Disorganized or scattered thoughts

- Rambling or straying off topic during conversations

- Ending a conversation abruptly

Treatment strategies

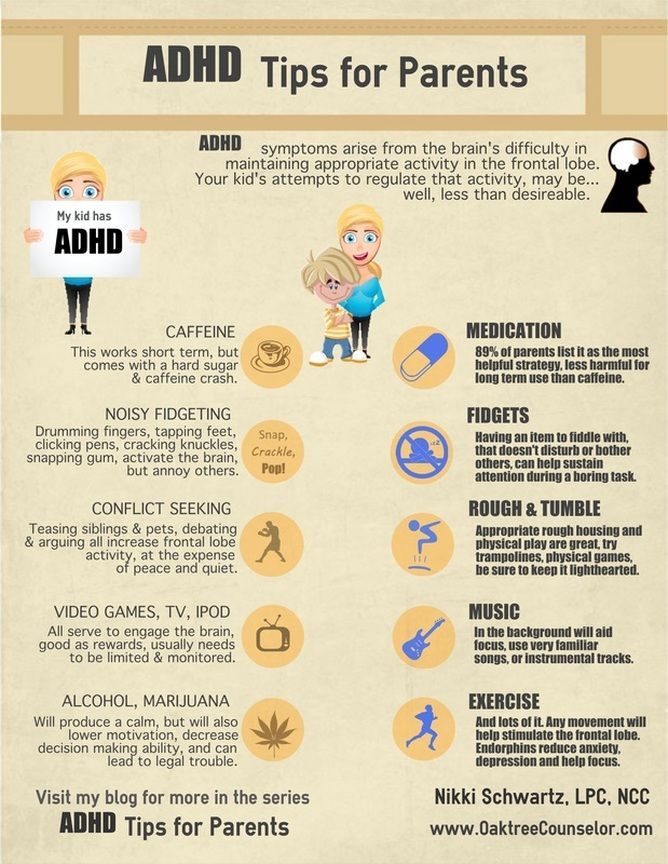

When the social skill areas in need of strengthening have been identified, obtaining a referral to a therapist or coach who understands how ADHD affects social skills is recommended (see Coaching). Medications are often helpful in the management of ADHD symptoms; in many cases, an effective dose of medication will give the adult with ADHD the boost in self-control and concentration necessary to utilize newly acquired social skills at the appropriate time. However, medications alone are usually not sufficient to help gain the necessary skills (see Medication Management).

However, medications alone are usually not sufficient to help gain the necessary skills (see Medication Management).

As discussed earlier, social skills training for children and adolescents with ADHD usually involves instruction, modeling, role-playing, and feedback in a safe setting such as a social skills group run by a therapist. In addition, arranging the environment to provide reminders has proven essential to using the correct social behavior at the opportune moment. These findings suggest that adults with ADHD wishing to work on their social skills should consider the following elements when seeking an effective intervention. It is important to note that these treatment strategies are suggestions based on clinical practice, rather than empirical research.

9 Ways to Master Social Skills

Knowledge. Oftentimes social skills can be significantly improved when there is an understanding of social skills as well as the areas in need of improvement. Reading books such as What Does Everybody Know That I Don’t, ADD and Romance, or You, Your Relationship & Your ADD can provide some of that knowledge .

Reading books such as What Does Everybody Know That I Don’t, ADD and Romance, or You, Your Relationship & Your ADD can provide some of that knowledge .

Attitude. Individuals with ADHD should have a positive attitude and be open to the growth of their social skills. It is also important to be open and appreciative of feedback provided by others.

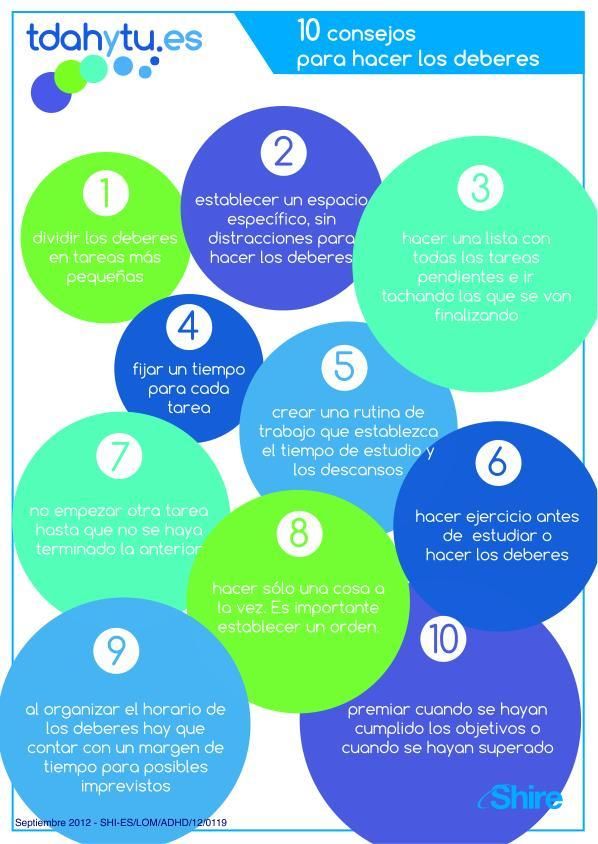

Goals. Adults with ADHD may want to pick and work on one goal at a time, based on a self-assessment and the assessments of others. Tackling the skill areas one at a time allows the individual to master each skill before moving on to the next.

The echo. Those who struggle with missing pieces of information due to attentional difficulties during conversation may benefit from developing a system of checking with others what they heard. “I heard you say that. Did I get it right Is there more ” Or an individual with ADHD could ask others to check with them after providing important information. “Please tell me what you heard me say.” In this way, social errors due to inattention can be avoided.

“Please tell me what you heard me say.” In this way, social errors due to inattention can be avoided.

Observe others. Adults with ADHD can learn a great deal by watching others do what they need to learn to do. They may want to try selecting models both at work and in their personal lives to help them grow in this area. Television may also provide role models.

Role play. Practicing the skills they need with others is a good way for individuals with ADHD to receive feedback and consequently improve their social skills.

Visualization. Visualization can be used to gain additional practice and improve one’s ability to apply the skill in other settings. Those who need practice in social skills can decide what they want to do and rehearse it in their minds, imagining actually using the skill in the setting they will be in with the people they will actually be interacting with. They can repeat this as many times as possible to help “overlearn” the skill. In this manner, they can gain experience in the “real” world, which will greatly increase the likelihood of their success.

In this manner, they can gain experience in the “real” world, which will greatly increase the likelihood of their success.

Prompts. Adults with ADHD can use prompts to stay focused on particular social skill goals. The prompts can be visual (an index card), verbal (someone telling them to be quiet), physical (a vibrating watch set every 4 minutes reminding them to be quiet), or a gesture (someone rubbing their head) to help remind them to work on their social skills.

Increase “likeability.” According to social exchange theory, people maintain relationships based on how well those relationships meet their needs. People are not exactly “social accountants,” but on some level, people do weigh the costs and benefits of being in relationships. Many with ADHD are considered to be “high maintenance.” Therefore, it is helpful to see what they can bring to relationships to help balance the equation. Investigators have found that the following are characteristics of highly likeable people: sincere, honest, understanding, loyal, truthful, trustworthy, intelligent, dependable, thoughtful, considerate, reliable, warm, kind, friendly, happy, unselfish, humorous, responsible, cheerful, and trustful. Developing or improving any of the likeability characteristics should help one’s social standing.

Developing or improving any of the likeability characteristics should help one’s social standing.

Although ADHD certainly brings unique challenges to social relationships, information and resources are available to help adults with ADHD improve their social skills. Most of this information is based upon sound clinical practice and research on social skills and ADHD in children and adolescents; there is a great need for more research on social skills and ADHD in adults. Seek help through reading, counseling, or coaching and, above all, build and maintain social connections.

Parenting Help for Social Skills

Most parents know that ADHD symptoms can be a problem in the classroom. Not being able to sit still, pay attention, or complete work has its consequences, none of them good. Those same symptoms — hyperactivity, inattention, problems with organization and time planning, and impulsivity — also prevent kids from making and keeping friends. The good news is that using appropriate attention deficit disorder (ADHD or ADD) medications, attending social skills classes, and using cognitive behavioral therapy can help a child improve socially.

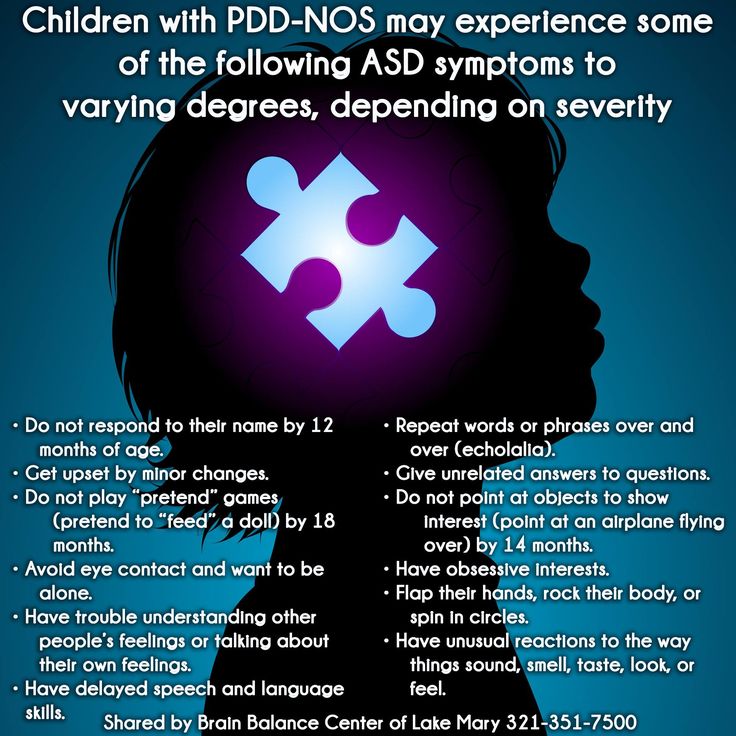

This is not the case for the challenges called pragmatic social skills problems. These are neurologically based, and are related to the brain’s ability to receive and process visual and auditory social cues. These problems are a major obstacle to a child trying to make and hold on to friends.

Missing the Cues

Some children, adolescents, and adults with ADHD can’t read others’ social cues, and don’t perceive how their body language and tone of voice are read by others.

Communicating with friends involves more than words. We communicate with facial expressions, gestures, eye contact, posture, and tone of voice. These make up nonverbal communication. Current studies suggest that nonverbal communication is a fully developed language, different from verbal communication (words) and processed in different areas of the brain than visual or auditory communication. Nonverbal communication is not taught. It is learned through observation, interactions, and feedback from others.

Nonverbal communication problems generally take one of two forms. In one scenario, the child or adult is unable to correctly read the nonverbal social cues of others. For example, the teacher stands in front of Billy’s desk, looking directly at him, her face taut. But it’s not until she says, “Stop that right now!” that Billy looks up, surprised. Billy did not pick up on the earlier cues that indicated his behavior was upsetting the teacher.

[[Self-Test] Could Your Child Have ADHD?]

In other cases, a child or adult is unable to recognize how others perceive her nonverbal cues. Ellen talks to a friend but is standing so close that she is almost in her face. Ellen’s voice is loud, and she is jumping up and down. Her friend pushes her away and says, “Leave me alone.” Ellen is hurt because her friend rejected her.

Listening and Seeing Incorrectly

Nonverbal communication problems can be auditory or visual. Auditory problems involve using the wrong tone of voice, rate of speech, and variations in volume and word emphasis. For instance, a child might speak too loudly or his tone might not match the emotional message he wants to convey.

For instance, a child might speak too loudly or his tone might not match the emotional message he wants to convey.

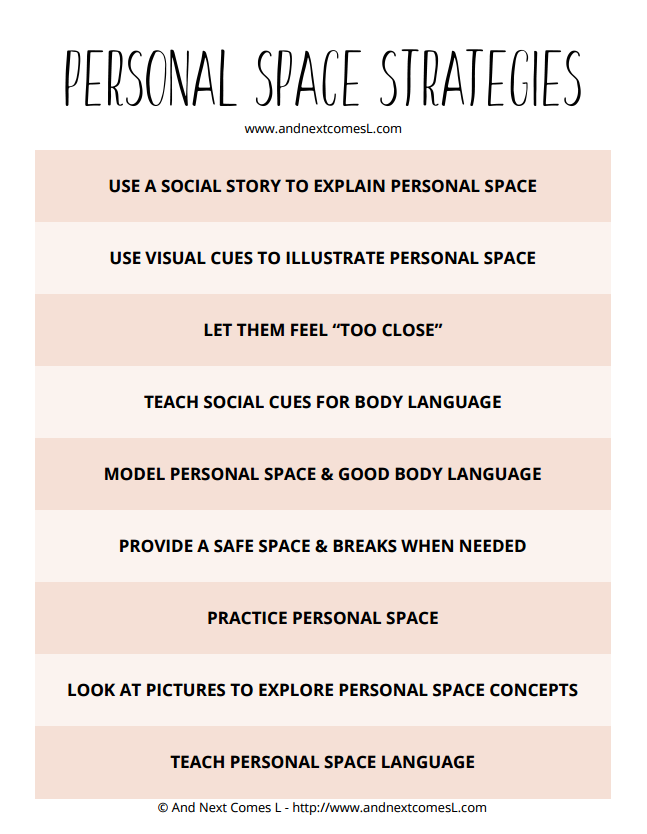

Visual communication problems involve everything from not being able to recognize the emotions expressed by others’ facial expressions to violating another’s personal space. For instance, a child may not be able to recognize a happy or fearful face. He may stand too close to someone while talking, or hug and kiss a stranger. His posture may indicate anger when he intends to express friendliness.

Social Smarts

Nonverbal communication challenges rarely respond to the typical social skills training groups that help many ADHD kids. Children with this challenge need specialized training.

[Free Friendship Guide for Kids with ADHD]

In specialized social skills groups, the child is made aware of and sensitive to his social problems. This step is critical. Some children have little awareness of their difficulties and may deny their problems or blame others for them. Once the individual begins to accept the problem, the second step is to help the child develop new strategies for interacting with others. The third step requires the child to practice these new strategies outside of the group and to report back on how they worked.

Once the individual begins to accept the problem, the second step is to help the child develop new strategies for interacting with others. The third step requires the child to practice these new strategies outside of the group and to report back on how they worked.

The children in a specialized group are taught to recognize social cues. The leader might say, “Kids, let’s look at these pictures. This one is a happy face. What makes it look like a happy face? This one is an angry face. What makes it look angry?” As children learn, the leader asks one of the children to show a happy face and another to show an angry face. As the class progresses, training may include asking a child to make or draw a face — a fearful one, say — and seeing if others in the group can guess the feeling that she is actually expressing.

If you suspect that your child has nonverbal communication problems, consult with a mental health professional. If he or she concurs, seek a referral to a pragmatic social skills group. It could make the difference between your child being lonely and being able to make and keep friends throughout life.

It could make the difference between your child being lonely and being able to make and keep friends throughout life.

[Your Free 13-Step Guide to Raising a Child with ADHD]

Larry Silver, M.D., is a member of ADDitude’s ADHD Medical Review Panel.

Previous Article Next Article

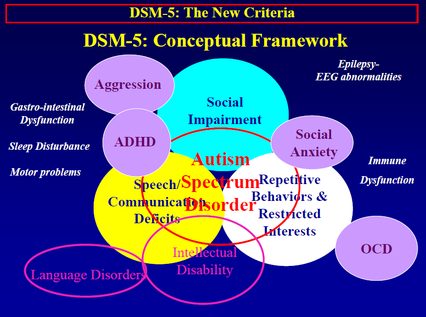

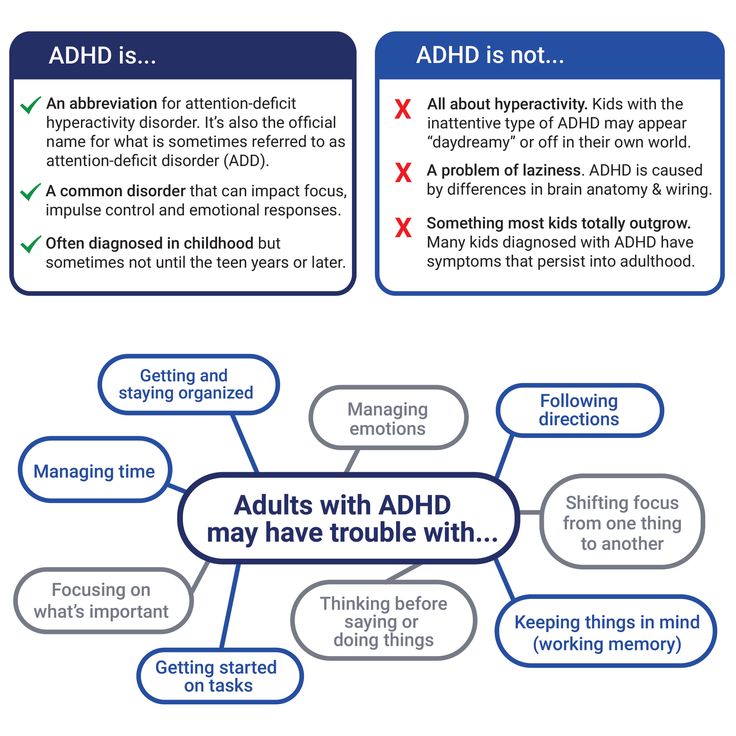

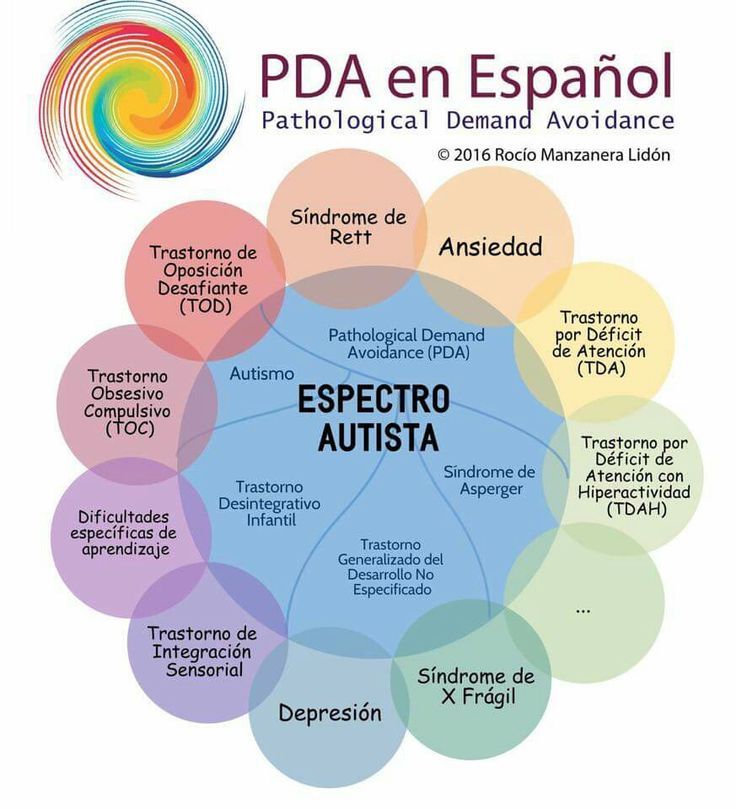

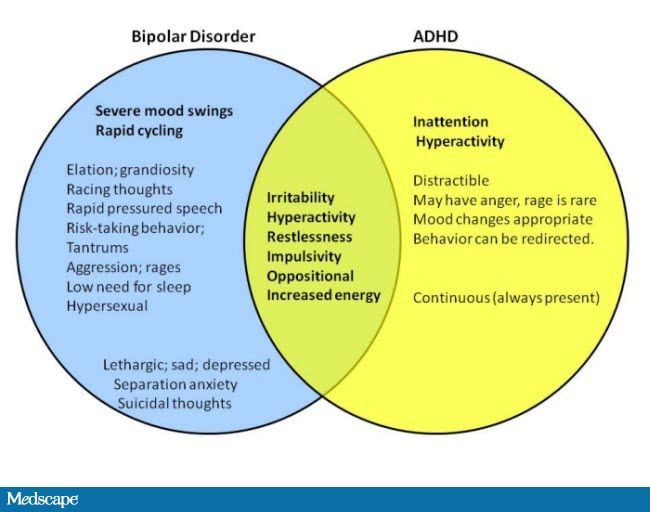

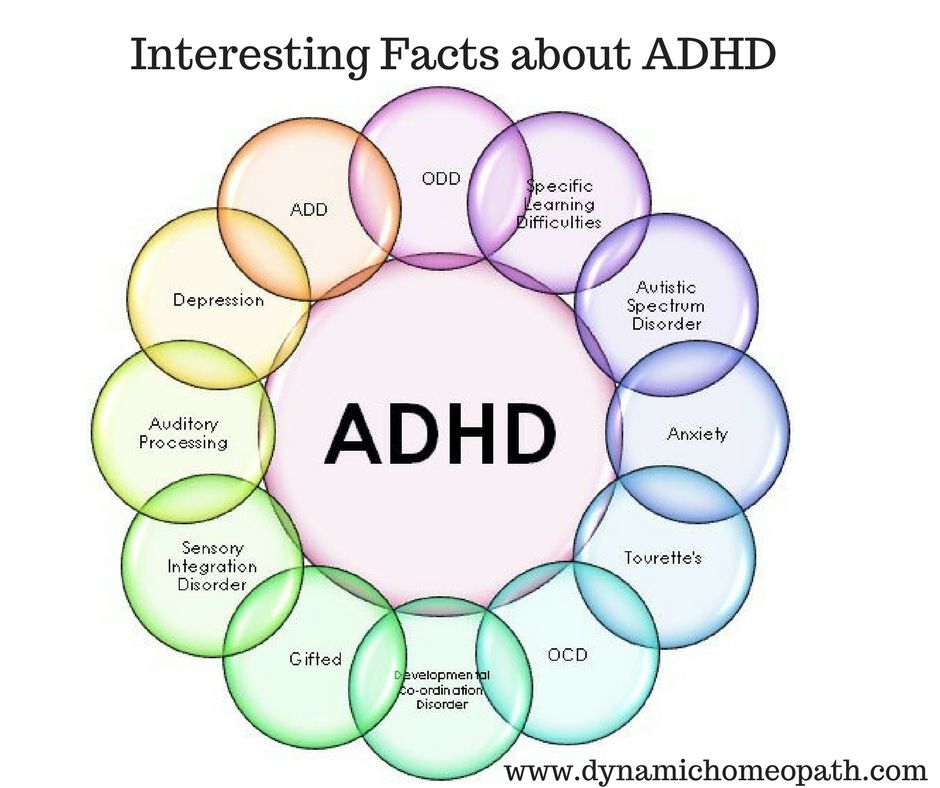

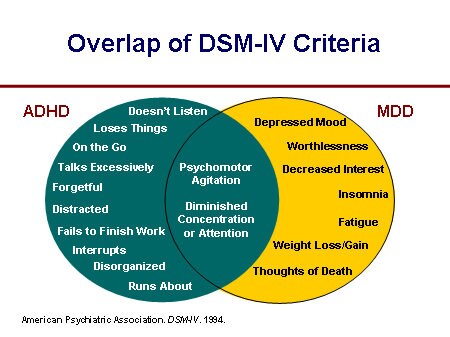

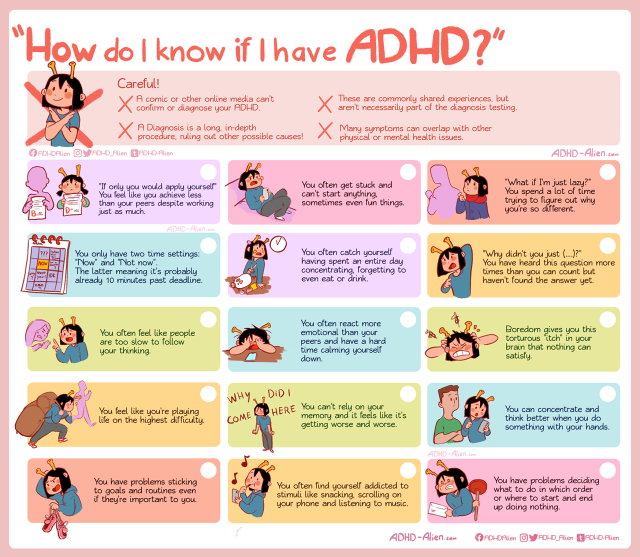

Difference between attention disorders with similar symptoms.

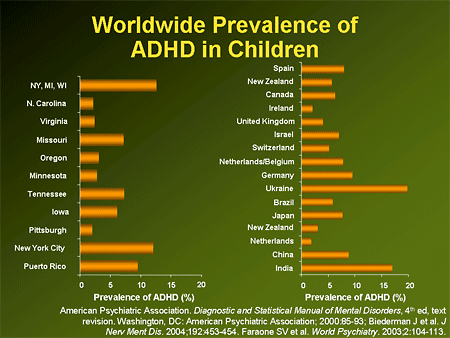

ADHD is the most commonly diagnosed conduct disorder in children under 18, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

When a child suffers from forgetfulness, restlessness, absent-mindedness and sleep problems, they are most often diagnosed with ADHD, but there are many other disorders and diseases that could also cause these symptoms.

When the symptoms of different disorders overlap, it can easily be confusing. Searching for symptoms like impulsivity, poor concentration, and more can lead you to Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Auditory Perception Disorder (ASD), Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), and more.

You need to work with a professional you trust to get a comprehensive assessment of your child. Sometimes it happens that a child has more than one disorder, and sometimes it happens that a child is misdiagnosed. The types of correction can be very different for each diagnosis, so the key to proper treatment is understanding what exactly you are dealing with.

If you liked the illustration, order your own from qwerkid!

When preparing for an appointment with a specialist, you need to be extremely careful and record all the details of your child's behavior so that you can provide a complete picture of what is happening at home. Understanding your child's symptoms can be tricky, so we've listed the three most common disorders that share symptoms with ADHD to help you better understand the similarities and differences between these disorders.

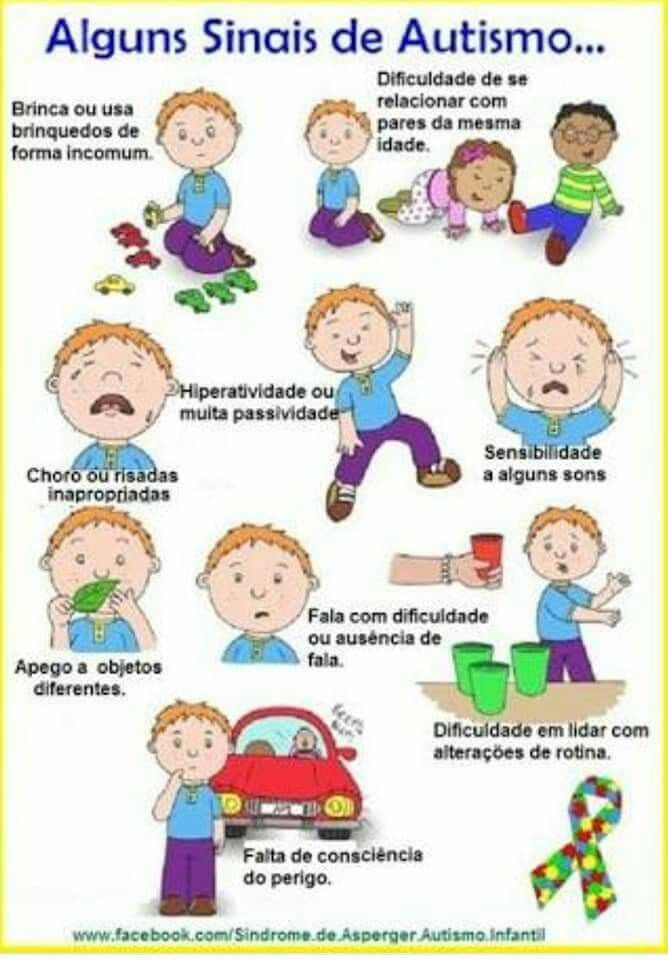

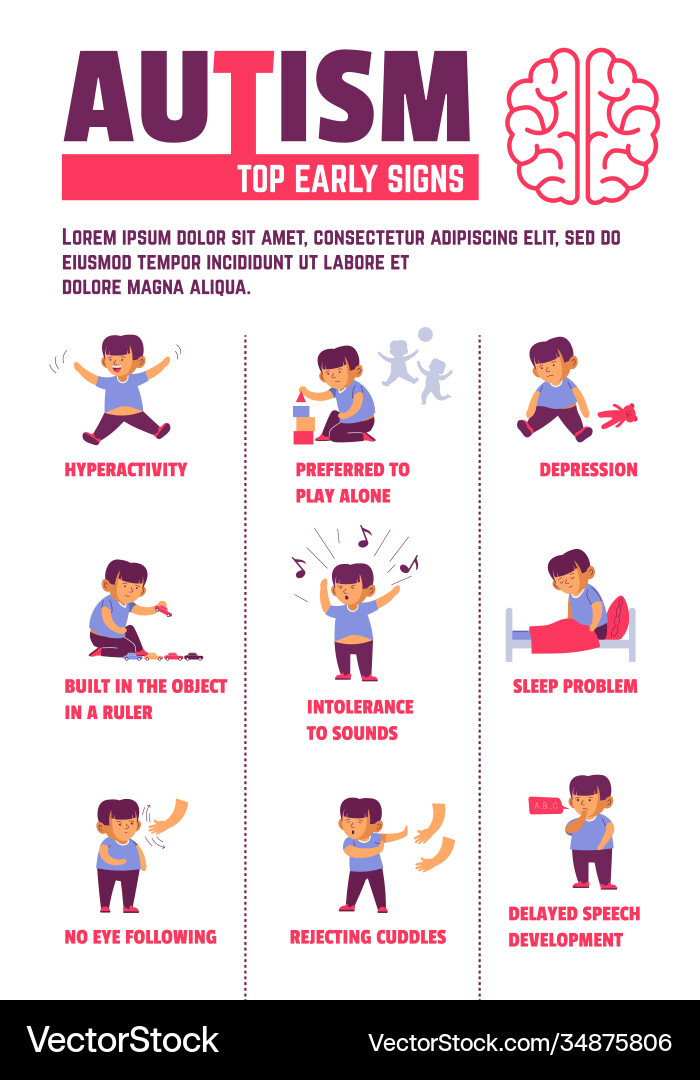

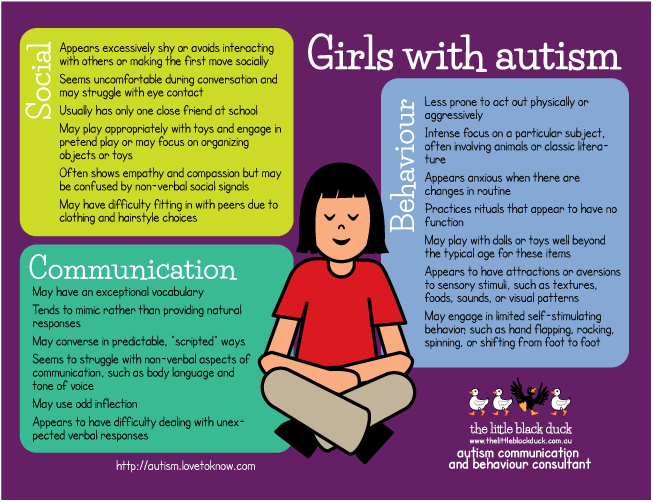

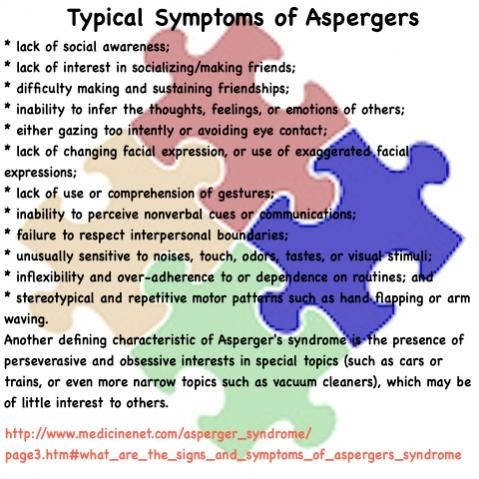

ADHD and Autism (ASD)

The two disorders have many similar symptoms, but it is important to remember that they are different. A child can have ADHD and ASD at the same time, but ADHD is a physiological disorder and autism is a variation of a neurological disorder. Depending on the diagnosis of ADHD, autism, or both, you will receive different treatment recommendations. Listed below are symptoms for each of the disorders, as well as similar symptoms for both disorders.

A child can have ADHD and ASD at the same time, but ADHD is a physiological disorder and autism is a variation of a neurological disorder. Depending on the diagnosis of ADHD, autism, or both, you will receive different treatment recommendations. Listed below are symptoms for each of the disorders, as well as similar symptoms for both disorders.

ADHD

-

Easily distracted

-

Always in the clouds

-

Forgetful

-

Does not listen when spoken to

-

Does not follow directions well

-

Poor impulse control

-

Has difficulty finishing things

-

Problems with self-organization

-

Impatient, unable to wait in line

-

Interrupts others

-

Acting without regard for consequences

-

plays rough

General symptoms

-

When a child is upset, it often leads to scandals

-

Difficulty making friends, holding conversations and responding appropriately

-

Constantly fidgets, moves and touches objects in his hands

-

Does not understand nonverbal cues

Autism

-

Avoids eye contact

-

Shy to touch

-

Speech problems

-

Frequently repeats the same phrases

-

Gets used to the routine and gets upset if it changes

-

Calms down with repetitive body movements (rocking, snapping fingers, etc.

)

) -

Obsessed with an interest in something

-

Problem with understanding the feelings of others and expressing empathy

ADHD and HSI (hearing impairment)

Although they are two physiological disorders with several similar symptoms, ADHD and HCW are very different. Distinguishing their symptoms is not always easy, but necessary in order to find the right help. Children with ADHD have trouble concentrating, and children with NSW have difficulty processing the information they hear. Hearing loss affects language skills, and children with ADHD have impaired executive function and memory and find it difficult to manage their emotions. Listed below are similarities and differences in symptoms.

ADHD

-

Always in the clouds

-

Poor impulse control

-

Has difficulty finishing things

-

Problems with self-organization

-

Impatient, unable to wait his turn

-

Interrupts others

-

Acting without regard for consequences

-

Playing rough

-

When a child is upset, it often leads to scandals

-

Difficulty making friends, holding conversations and responding appropriately

-

Constantly fidgets, moves and touches objects in his hands

-

Does not understand nonverbal cues

General symptoms

-

Does not listen when spoken to, as if dropped out of the conversation

-

Forgetful

-

Does not follow directions well

-

Easily distracted

NSV

-

Difficulty holding a conversation

-

Difficult to answer if asked aloud

-

Frequently asks to repeat what has been said

-

Frequently asks: “huh?” "What?"

-

Doesn't follow verbal directions well

-

May have speech problems, possibly confusing similar sounds

-

Can't rhyme

-

Poor listening comprehension

-

Prefers to read a book by himself rather than having someone read to him

Help your child quickly develop auditory perception, concentration, memory and other key cognitive functions!

Learn more

ADHD and learning disorders (dyslexia, dysgraphia, dyscalculia, etc.

)

)

The symptoms of ADHD and learning disorders can be very similar, depending on which learning disorder the child has. Although 30-50% of children with ADHD also have some form of learning disorder, ADHD itself is not considered a learning disorder. You may see similar behaviors and symptoms, or you may have a child with both ADHD and a learning disorder. Since the causes of a child's difficulties can be very different, interventions (methods of assistance) should be selected individually, depending on the situation. Here are some symptoms of ADHD and learning disorders that can show up in children:

ADHD

-

Does not listen when spoken to, as if dropped out of the conversation

-

Always in the clouds

-

Does not follow directions well

-

Impatient, unable to wait his turn

-

Interrupts others

-

Acting without regard for consequences

-

plays rough

-

When a child is upset, it often leads to scandals

-

Difficulty making friends, holding conversations and responding appropriately

-

Constantly fidgets, moves and touches objects in his hands

-

Does not understand nonverbal cues

General symptoms

-

Forgetful, "lazy and unmotivated"

-

Does not follow directions well

-

Problems with self-organization

-

Problems with concentration

-

Inappropriate reaction in various situations

-

Easily distracted

Learning disorders

-

Speech delay

-

Poorly developed social skills and coordination

-

Difficulties with written words and rapid letter recognition

-

Difficulties with pronunciation of words aloud

-

Difficulties with independent reading and memorization

-

Difficulty in organizing thoughts

-

Poor understanding of the concept of time and everything related to it

Recognizing symptoms or understanding the causes of disorders is not always easy, especially when disorders have so many similar symptoms. Explore different attention disorders to better understand them and the behaviors associated with them. You need to work with a qualified professional to accurately evaluate your child and find the best support programs for them.

Explore different attention disorders to better understand them and the behaviors associated with them. You need to work with a qualified professional to accurately evaluate your child and find the best support programs for them.

Retrieved

Now you can help your child develop concentration and other cognitive skills without leaving home!

Train with the neuro-innovative Fast ForWord method, it has repeatedly proven its effectiveness in ADHD, ASD, NSV and learning disorders!

Sign up for online trial classes, don't delay helping your child with attention disorder!

SIGN UP

Summing up the symptoms:

Useful article? Share with friends!

Read useful materials on the topic:

-

Learn more about Fast ForWord

-

Why do some children have difficulty following instructions?

-

"Hyperactivity decreased by 70 percent, in just 10 weeks of classes - fantastic!"

-

Find out more about NSV

-

How do weak cognitive skills affect learning?

-

How Fast ForWord Helped Matthew Woodward Diagnosed with ADHD in Elementary School

-

How to eliminate speech disorders and train attention using Fast ForWord

-

How to discipline a child with ADHD before you reach the boiling point

-

Ear glasses will help develop speech and auditory information processing speed!

-

Find out how Mia Robinson, thanks to her Fast ForWord program, got over her habit of attacking people in fits of anger

-

Three ways to help your child with ADHD think realistically

-

5 common myths about auditory processing disorder

-

How to assess the correctness of the diagnosis of "auditory processing disorder"?

-

The influence of working memory on the learning and development of the child

-

10 tips for talking to your child about attention problems

-

What about the child: ADHD, Auditory Perception Impairment or Specific Language Development Disorder?

Read useful materials on our pages in social networks!

Subscribe!

To play, press and hold the enter key. To stop, release the enter key.

To stop, release the enter key.

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children | Zinov'eva

1. Polanczyk G, de Lima MS, Horta BL, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: a systematic review and metaregression analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164(6):942–8. DOI:

2. Bryazgunov IP, Kasatikova EV. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children. Moscow: Medpraktika; 2002. 128 p. [Bryazgunov IP, Kasatikova EV. Defitsit vnimaniya s giperaktivnost'yu u detei [Deficiency of attention with a hyperactivity at children]. Moscow: Medpraktika; 2002. 128 p. (In Russ.)]

3. Zavadenko NN. Hyperactivity and attention deficit in childhood. Moscow: ACADEMIA; 2005. 256 p. [Zavadenko N.N. Giperaktivnost' i defitsit vnimaniya v detskom vozraste [Hyperactivity and deficiency of attention at children's age]. Moscow: ACADEMIA; 2005. 256 p. (In Russ.)]

4. Biederman J, Kwon A, Aleardi M, et al. Absence of gender effects on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: findings in nonreferred subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1083–9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1083.

Absence of gender effects on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: findings in nonreferred subjects. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162(6):1083–9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.162.6.1083.

5. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed.: DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association. 2013.

6. Aleksandrov AA, Karpina NV, Stankevich LN. Negativity of mismatch in evoked potentials of the brain in adolescents in the norm and with attention deficit upon presentation of acoustic stimuli of short duration. Russian Physiological Journal. THEM. Sechenov. 2003;33(7):671–5. [Aleksandrov AA, Karpina NV, Stankevich LN. Mismatch negativity in evoked brain potentials in adolescents in normal conditions and attention deficit in response to presentation of short-duration acoustic stimuli. Rossiiskii fiziologicheskii zhurnal im. I.M. Sechenova = Neuroscience and behavioral physiology. 2003;33(7):671–5. (In Russ.)]

7. Becker SP, Langberg JM, Vaughn AJ, Epstein JN. Clinical utility of the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic parent rating scale comorbidity screening scales. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33(3):221–8. DOI: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318245615b.

Clinical utility of the Vanderbilt ADHD diagnostic parent rating scale comorbidity screening scales. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2012;33(3):221–8. DOI: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e318245615b.

8. Gorbachevskaya NL, Zavadenko NN, Sorokin AB, Grigorieva NV. Neurophysiological study of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Siberian Bulletin of Psychiatry and Narcology. 2003;(1):47–51. [Gorbachevskaya NL, Zavadenko NN, Sorokin AB, Grigor'eva NV. Neurophysiological research of a syndrome of deficiency of attention with a hyperactivity. Sibirskii vestnik psikhiatrii i narkologii. 2003;(1):47–51. (In Russ.)]

9. Biederman J, Faraone S. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Lancet. 2005;366(9481):237–48. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66915-2.

10. Mick E, Faraone SV. Genetics of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2008;17(2):261–84, vii-viii. DOI: 10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.011.

11. Haavik J, Blau N, Thö ny B. Mutations in human monoamine-related neurotransmitter pathway genes. Hum Mutat. 2008;29(7):891–902. DOI: 10.1002/humu.20700.

Hum Mutat. 2008;29(7):891–902. DOI: 10.1002/humu.20700.

12. Schulz KP, Himelstein J, Halperin JM, Newcorn JH. Neurobiological models of attentiondeficit/hyperactivity disorder: a brief review of the empirical evidence. CNS spectra. 2000;5(6):34–44.

13. Arnsten AFT, Pliszka SR. Catecholamine influences on prefrontal cortical function: relevance to treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and related disorders. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2011;99(2):211–6. DOI: 10.1016/j.pbb.2011.01.020. Epub 2011 Feb 2.

14. McNally MA, Crocetti D, Mahone EM, et al. Corpus callosum segment circumference is associated with response control in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). J Child Neurology. 2010;25(4):453–62. DOI: 10.1177/0883073809350221. Epub 2010 Feb 5.

15. Nakao T, Radua J, Rubia K, Mataix-Cols D. Gray matter volume abnormalities in ADHD: voxelbased meta-analysis exploring the effects of age and stimulant medication. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(11):1154–63. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020281. Epub 2011 Aug 24.

2011;168(11):1154–63. DOI: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.11020281. Epub 2011 Aug 24.

16. Valera EM, Faraone SV, Murray KE, Seidman LJ. Meta-analysis of structural imaging findings in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(12):1361–9. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.06.011. Epub 2006 Sep 1.

17. Finger AB. Lectures on developmental neurology. Moscow: MEDpressinform; 2012. 376 p. [Pal'chik AB. Lektsii po nevrologii razvitiya [Lectures on development neurology]. Moscow: MEDprecsinform; 2012. 376 p. (In Russ.)]

18. Reddy DS. Neurosteroids: Endogenous role in the human brian and therapeutic potentials. Prog. Brain Res. 2010;186:113–137.

19. Shaw P, Eckstrand K, Sharp W, et al. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder is characterized by a delay in cortical maturation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(49):19649–54. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0707741104. Epub 2007 Nov 16.

20. Fair DA, Posner J, Nagel BJ, et al. Atypical default network connectivity in youth with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychology. 2010;68(12):1084–91. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.003. Epub 2010 Aug 21.

Atypical default network connectivity in youth with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Biological psychology. 2010;68(12):1084–91. DOI: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.07.003. Epub 2010 Aug 21.

21. Makris N, Biederman J, Monuteaux MC, Seidman LJ. Towards Conceptualizing a Neural Systems-Based Anatomy of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Dev Neurosci. 2009;31(1–2):36–49. DOI: 10.1159/000207492. Epub 2009 Apr 17.

22. Kaplan RF, Stevens MC. A review of adult ADHD: a neuropsychological and neuroimaging perspective. CNS Spectrums. 2002;7(5):355–62.

23. Krause J. SPECT and PET of the dopamine transporter in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(4):611–25. DOI: 10.1586/14737175.8.4.611.

24. Zametkin A, Liebenauer L, Fitzgerald G, et al. Brain metabolism in teenagers with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:333–40. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1993.01820170011002.

25. Arns M, Conners CK, Kraemer HC. A decade of EEG Theta/Beta ratio research in ADHD – a meta-analysis. J Atten Discord. 2013;17(5):374–83. DOI: 10.1177/1087054712460087. Epub 2012 Oct 19.

Arns M, Conners CK, Kraemer HC. A decade of EEG Theta/Beta ratio research in ADHD – a meta-analysis. J Atten Discord. 2013;17(5):374–83. DOI: 10.1177/1087054712460087. Epub 2012 Oct 19.

26. Anjana Y, Khaliq F, Vaney N. Event-related potentials study in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Funct Neurol. 2010;25(2):87–92.

27. Oades RD, Dittman-Balcar A, Schepker R, et al. Auditory event-related potentials (ERPs) and mismatch negativity (MMN) in healthy children and those with attention-deficit or tourettetic symptoms. Biol Psychol. 1996;43(2):163–85. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0301-0511(96)05189-7.

28. Meisel V, Servera M, Garcia-Banda G, et al. Neurofeedback and standard pharmacological intervention in ADHD: a randomized controlled trial with six-month follow-up. Biol Psychol. 2013;94(1):12–21. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2013.04.015.

29. Wilens T, Spencer T, Biederman J. A large, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of methylphenidate in the treatment of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.