Uncontrolled rapid eye movement

Nystagmus: MedlinePlus Medical Encyclopedia

URL of this page: //medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003037.htm

To use the sharing features on this page, please enable JavaScript.

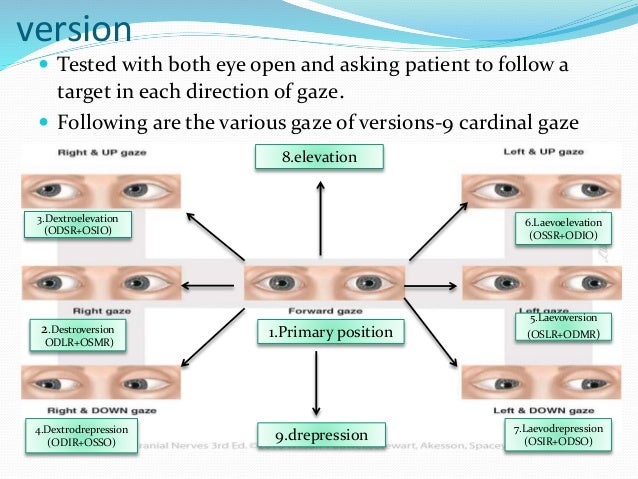

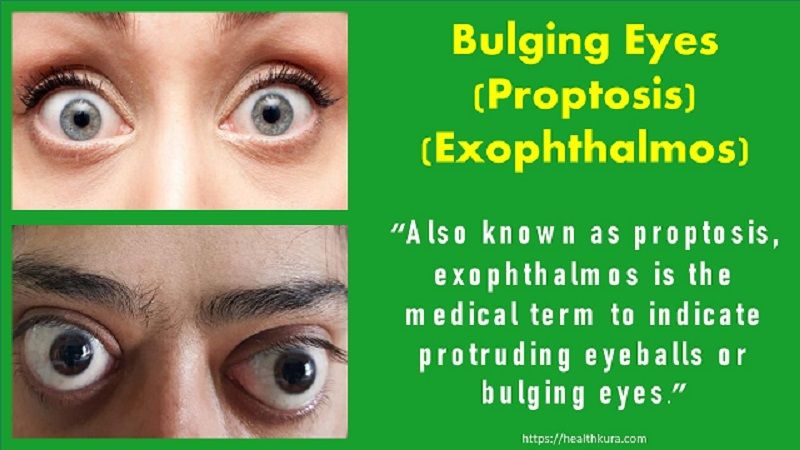

Nystagmus is a term to describe fast, uncontrollable movements of the eyes that may be:

- Side to side (horizontal nystagmus)

- Up and down (vertical nystagmus)

- Rotary (rotary or torsional nystagmus)

Depending on the cause, these movements may be in both eyes or in just one eye.

Nystagmus can affect vision, balance, and coordination.

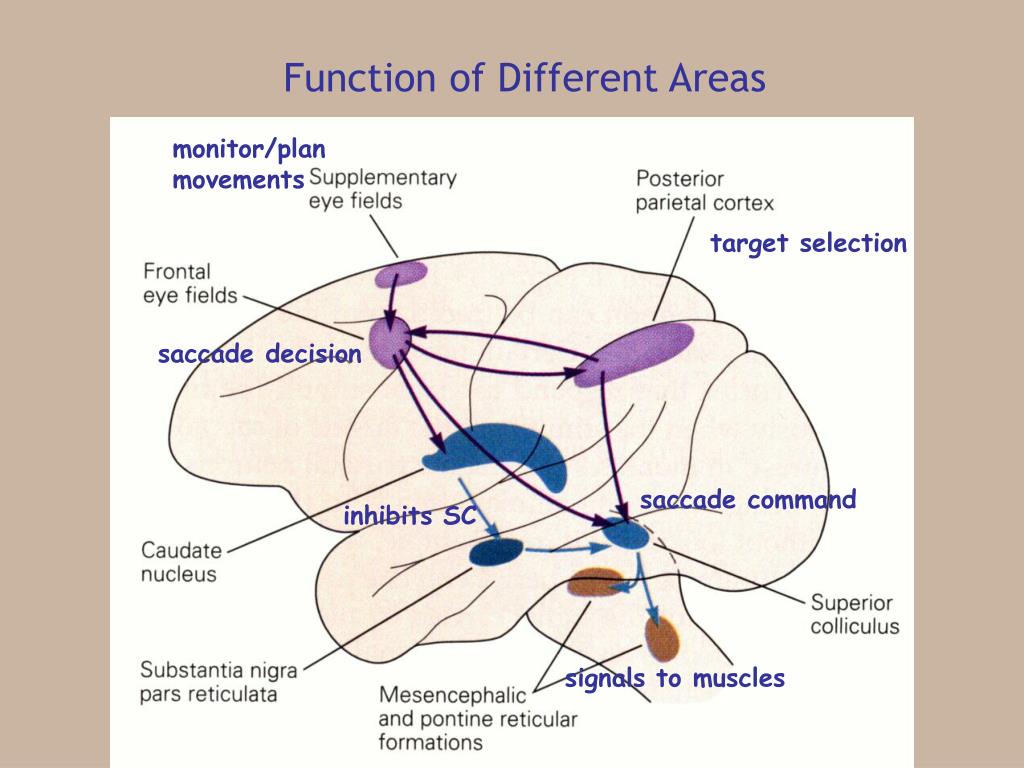

The involuntary eye movements of nystagmus are caused by abnormal function in the areas of the brain that control eye movements. The part of the inner ear that senses movement and position (the labyrinth) helps control eye movements.

There are two forms of nystagmus:

- Infantile nystagmus syndrome (INS) is present at birth (congenital).

- Acquired nystagmus develops later in life because of a disease or injury.

NYSTAGMUS THAT IS PRESENT AT BIRTH (infantile nystagmus syndrome, or INS)

INS is usually mild. It does not become more severe, and it is not related to any other disorder.

People with this condition are usually not aware of the eye movements, but other people may see them. If the movements are large, sharpness of vision (visual acuity) may be less than 20/20. Surgery may improve vision.

Nystagmus may be caused by congenital diseases of the eye. Although this is rare, an eye doctor (ophthalmologist) should evaluate any child with nystagmus to check for eye disease.

ACQUIRED NYSTAGMUS

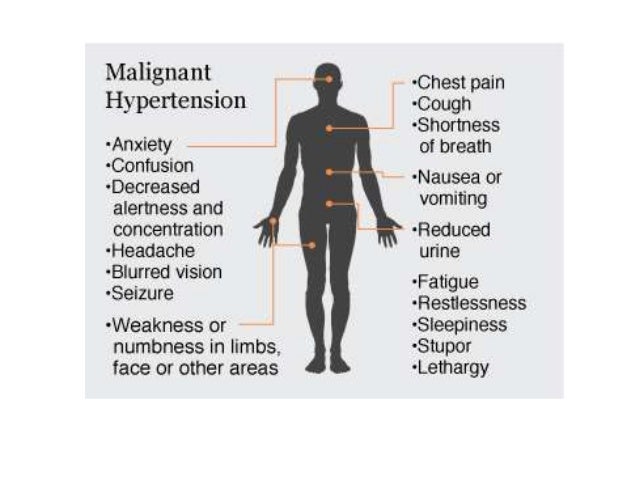

The most common cause of acquired nystagmus is certain drugs or medicines. Phenytoin (Dilantin) - an antiseizure medicine, excessive alcohol, or any sedating medicine can impair the labyrinth's function.

Other causes include:

- Head injury from motor vehicle accidents

- Inner ear disorders such as labyrinthitis or Meniere disease

- Stroke

- Thiamine or vitamin B12 deficiency

- Multiple sclerosis

- Brain tumors

You may need to make changes in the home to help with dizziness, visual problems, or nervous system disorders.

Call your health care provider if you have symptoms of nystagmus or think you might have this condition.

Your provider will take a careful history and perform a thorough physical examination, focusing on the nervous system and inner ear. The provider may ask you to wear a pair of goggles that magnify your eyes for part of the examination.

To check for nystagmus, the provider may use the following procedure:

- You spin around for about 30 seconds, stop, and try to stare at an object.

- Your eyes will first move slowly in one direction, then will move quickly in the opposite direction.

If you have nystagmus due to a medical condition, these eye movements will depend on the cause.

You may have the following tests:

- CT scan of the head

- Electro-oculography: An electrical method of measuring eye movements using tiny electrodes

- MRI of the head

- Vestibular testing by recording the movements of the eyes

There is no treatment for most cases of congenital nystagmus. Treatment for acquired nystagmus depends on the cause. In some cases, nystagmus cannot be reversed. In cases due to medicines or infection, the nystagmus usually goes away after the cause has gotten better.

Treatment for acquired nystagmus depends on the cause. In some cases, nystagmus cannot be reversed. In cases due to medicines or infection, the nystagmus usually goes away after the cause has gotten better.

Some treatments may help improve the visual function of people with infantile nystagmus syndrome:

- Prisms

- Surgery such as tenotomy

- Drug therapies for infantile nystagmus

Back and forth eye movements; Involuntary eye movements; Rapid eye movements from side to side; Uncontrolled eye movements; Eye movements - uncontrollable

- External and internal eye anatomy

Olitsky SE, Marsh JD. Disorders of eye movement and alignment. In: Kliegman RM, St. Geme JW, Blum NJ, Shah SS, Tasker RC, Wilson KM, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics. 21st ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2020:chap 641.

Quiros PA, Chang MY. Nystagmus, saccadic intrusions, and oscillations. In: Yanoff M, Duker JS, eds. Ophthalmology. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 9.19.

Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2019:chap 9.19.

Rucker JC, Lavin PJM. Neuro-ophthalmology: ocular motor system. In: Jankovic J, Mazziotta JC, Pomeroy SL, Newman NJ, eds. Bradley and Daroff's Neurology in Clinical Practice. 8th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2022:chap 18.

Updated by: Evelyn O. Berman, MD, Assistant Professor of Neurology and Pediatrics at University of Rochester, Rochester, NY. Review provided by VeriMed Healthcare Network. Also reviewed by David Zieve, MD, MHA, Medical Director, Brenda Conaway, Editorial Director, and the A.D.A.M. Editorial team.

Nystagmus: Causes, Symptoms and Treatments

We include products we think are useful for our readers. If you buy through links on this page, we may earn a small commission. Here’s our process.

Healthline only shows you brands and products that we stand behind.

Our team thoroughly researches and evaluates the recommendations we make on our site. To establish that the product manufacturers addressed safety and efficacy standards, we:

To establish that the product manufacturers addressed safety and efficacy standards, we:

- Evaluate ingredients and composition: Do they have the potential to cause harm?

- Fact-check all health claims: Do they align with the current body of scientific evidence?

- Assess the brand: Does it operate with integrity and adhere to industry best practices?

We do the research so you can find trusted products for your health and wellness.

Read more about our vetting process.What is nystagmus?

Nystagmus is a condition that causes involuntary, rapid movement of one or both eyes. It often occurs with vision problems, including blurriness.

This condition is sometimes called “dancing eyes.”

The symptoms include fast, uncontrollable eye movements. The direction of movement determines the type of nystagmus:

- Horizontal nystagmus involves side-to-side eye movements.

- Vertical nystagmus involves up-and-down eye movements.

- Rotary, or torsional, nystagmus involves circular movements.

These movements may occur in one or both eyes depending on the cause.

Nystagmus occurs when the part of the brain or inner ear that regulates eye movement and positioning doesn’t function correctly.

The labyrinth is the outer wall of the inner ear that helps you sense movement and position. It also helps control eye movements. The condition can be either genetic or acquired.

Infantile nystagmus syndrome

Congenital nystagmus is called infantile nystagmus syndrome (INS). It may be an inherited genetic condition. INS typically appears within the first six weeks to three months of a child’s life.

This type of nystagmus is usually mild and isn’t typically caused by an underlying health problem. In rare cases, a congenital eye disease could cause INS. Albinism is one genetic condition associated with INS.

Most people with INS won’t need treatment and don’t have complications later in life. In fact, many people with INS don’t even notice their eye movements. However, vision challenges are common.

In fact, many people with INS don’t even notice their eye movements. However, vision challenges are common.

Vision problems can range from mild to severe, and many people require corrective lenses or decide to have corrective surgery.

Acquired nystagmus

Acquired, or acute, nystagmus can develop at any stage of life. It often occurs due to injury or disease. Acquired nystagmus typically occurs due to events that affect the labyrinth in the inner ear.

Possible causes of acquired nystagmus include:

- stroke

- certain medications, including sedatives and antiseizure medications like phenytoin (Dilantin)

- excessive alcohol consumption

- head injury or trauma

- diseases of the eye

- diseases of the inner ear

- B-12 or thiamine deficiencies

- brain tumors

- diseases of the central nervous system, including multiple sclerosis

See your doctor if you begin to notice symptoms of nystagmus. Acquired nystagmus always occurs due to an underlying health condition. You’ll want to determine what that condition is and how best to treat it.

You’ll want to determine what that condition is and how best to treat it.

If you have congenital nystagmus, you’ll need to see an eye doctor called an ophthalmologist if the condition worsens or if you’re concerned about your vision.

Your ophthalmologist can diagnose nystagmus by performing an eye exam. They’ll ask you about your medical history to determine if any underlying health problems, medications, or environmental conditions may be contributing to your vision problems. They may also:

- measure your vision to determine the type of vision problems you have

- conduct a refraction test to determine the correct lens power you’ll need to compensate for your vision problems

- test how your eyes focus, move, and function together to look for problems that affect control of your eye movements or make it hard to use both eyes together

If your ophthalmologist diagnoses you with nystagmus, they may recommend that you see your primary care physician to address any underlying health conditions. They may also give you some tips for what to do at home to help you cope with nystagmus.

They may also give you some tips for what to do at home to help you cope with nystagmus.

Your primary care physician can help determine what’s causing your nystagmus. They’ll first ask about your medical history and then perform a physical exam.

If your doctor can’t determine the cause of your nystagmus after taking your history and performing a physical exam, they’ll run various tests. Blood tests can help your doctor rule out any vitamin deficiencies.

Imaging tests, such as X-rays, CT scans, and MRIs, can help your doctor determine if any structural abnormalities in your brain or head are causing your nystagmus.

Treatment for nystagmus depends on whether the condition is congenital or acquired. Congenital nystagmus doesn’t require treatment, although the following may help improve your vision:

- eyeglasses

- contact lenses

- increased lighting around the house

- [Affiliate link: magnifying devices]

Sometimes, congenital nystagmus lessens over the course of childhood without treatment. If your child has a very severe case, their doctor may suggest a surgery called a tenotomy to change the position of the muscles that control eye movement.

If your child has a very severe case, their doctor may suggest a surgery called a tenotomy to change the position of the muscles that control eye movement.

Such surgery can’t cure nystagmus, but it can reduce the degree to which your child needs to turn their head to improve their vision.

If you have acquired nystagmus, treatment will focus on the underlying cause. Some common treatments for acquired nystagmus include:

- changing medications

- correcting vitamin deficiencies with supplements and dietary adjustments

- medicated eye drops for eye infections

- antibiotics for infections of the inner ear

- botulinum toxin to treat severe disturbances in vision caused by eye movement

- special glasses lenses called prisms

- brain surgery for central nervous system disorders or brain diseases

Nystagmus may improve over time with or without treatment. However, nystagmus usually never goes away completely.

The symptoms of nystagmus can make daily tasks more challenging. For instance, those with severe nystagmus may not be able to get a driver’s license, which can limit their mobility and require them to make transportation arrangements on a regular basis.

For instance, those with severe nystagmus may not be able to get a driver’s license, which can limit their mobility and require them to make transportation arrangements on a regular basis.

Sharp eyesight is also important if you’re handling or operating potentially dangerous equipment or equipment requiring precision. Nystagmus can limit the types of occupations and hobbies you have.

Another challenge of severe nystagmus is finding caregiver help. If you have very poor eyesight, you may need help carrying out daily activities. If you need assistance, it’s important to ask for it. Limited eyesight may increase your chances of injury.

The American Nystagmus Network has a list of helpful resources. You should also ask your doctor about the resources they recommend.

Nystagmus: neurological eye disease, types, causes, symptoms, treatment.

From All About Vision

Nystagmus is an involuntary eye movement disorder that affects both eyes. The eyeballs can move quickly in vertical or horizontal directions, as well as in a circle (partial rotation).

Nystagmus is usually accompanied by a decrease in visual acuity and depth perception, which can affect balance and coordination.

Nystagmus is often congenital, presenting between 6 weeks and a few months of age and may be inherited. However, nystagmus can affect people of any age, especially those with neurological conditions.

The prevalence of nystagmus in the world population is unknown. However, a UK study estimates it is 2.4 cases per 1000 people. The study also showed that nystagmus is significantly more common among white European populations than among Asian (Indian, Pakistani, other Asian peoples) populations.

Types of nystagmus

The following types of nystagmus are distinguished:

Congenital nystagmus present at birth. In this state, the eyes simultaneously move in one direction and the other (like a pendulum). Most other types of childhood nystagmus are also classified as forms of strabismus , which means that the eyes do not always move together.

Manifest nystagmus always present, while latent nystagmus appears only when one eye is closed.

Manifest-latent nystagmus is always present, but worsens when one eye is closed.

Acquired nystagmus can be caused by a medical condition (multiple sclerosis, brain tumor, diabetic neuropathy ), an accident (head injury), or a neurological problem (drug side effect). In rare cases, hyperventilation, flashes of light in front of one eye, nicotine, and even vibration have been known to cause nystagmus.

Some acquired forms of nystagmus can be treated with medication or surgery.

Causes, symptoms and complications associated with nystagmus

As mentioned above, most people with nystagmus are born with this condition or it appears at an early age.

If nystagmus is not caused by injury or disease, it is almost always due to neurological problems.

Two main types of nystagmus:

People with inner ear involvement can develop a condition called "clonic (jerky) nystagmus" - the eyes slowly drift in one direction and then quickly move back in the other. Due to eye movement, people with this condition may develop nausea and dizziness.

This type of nystagmus, usually temporary, can also occur in people with Meniere's disease (an inner ear disorder) or when water gets into one ear. This type of nystagmus can sometimes be treated with a decongestant.

All forms of nystagmus are involuntary, meaning people with the disease cannot control their eyes.

Sometimes nystagmus lessens slightly as the person comes of age, but it worsens with fatigue and stress.

The presence of nystagmus affects both vision and self-esteem. Most people with nystagmus have limited vision because the eyes are constantly moving around the object they are looking at, making it impossible to get a clear image.

Some people with nystagmus have so many visual problems that they can officially be considered blind.

If you have nystagmus, it affects more than just your appearance. You see differently than people who do not have this condition. Your eyes are in constant motion.

To see better, you may need to turn your head and fix your eyes on the so-called "zero point". This is the specific head angle that causes the eyes to move the least, stabilizing the image for better vision.

When you have nystagmus, you have to deal with the personal and social consequences of this condition.

Nystagmus can affect almost every aspect of your life, including how you relate to others, your educational and work opportunities, and your self-esteem.

If you experience social and personal problems, often associated with nystagmus, it may be helpful to consult a doctor.

Can nystagmus be cured?

There are several medical and surgical treatments that sometimes help people with nystagmus.

Surgery usually reduces the zero position, head tilt, and provides a cosmetic improvement.

Drugs such as Botox or Baclofen can sometimes reduce the involuntary eye movements of nystagmus, although the results are usually temporary.

For some people with nystagmus, self-management training helps.

If you have nystagmus, be sure to get regular eye exams to monitor both your health and vision.

Glasses and contact lenses can help people with nystagmus see better. Because contact lenses move with the eyes, the vision provided by contact lenses is sometimes clearer than with glasses. Your optometrist can advise you on which vision correction method is best for your needs.

Page published on Monday, November 16, 2020

Involuntary eye movements

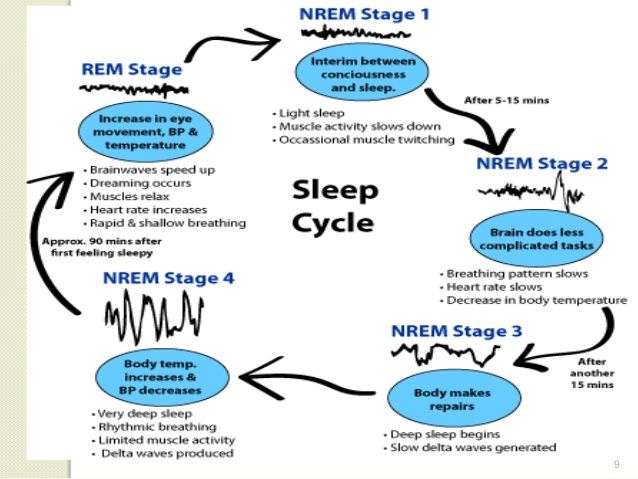

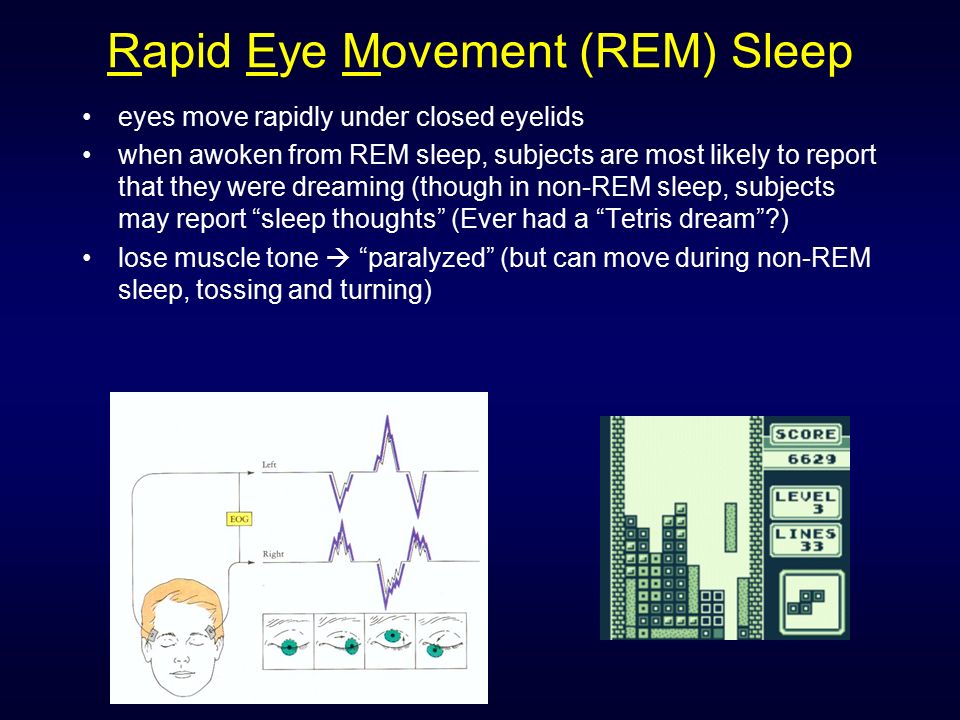

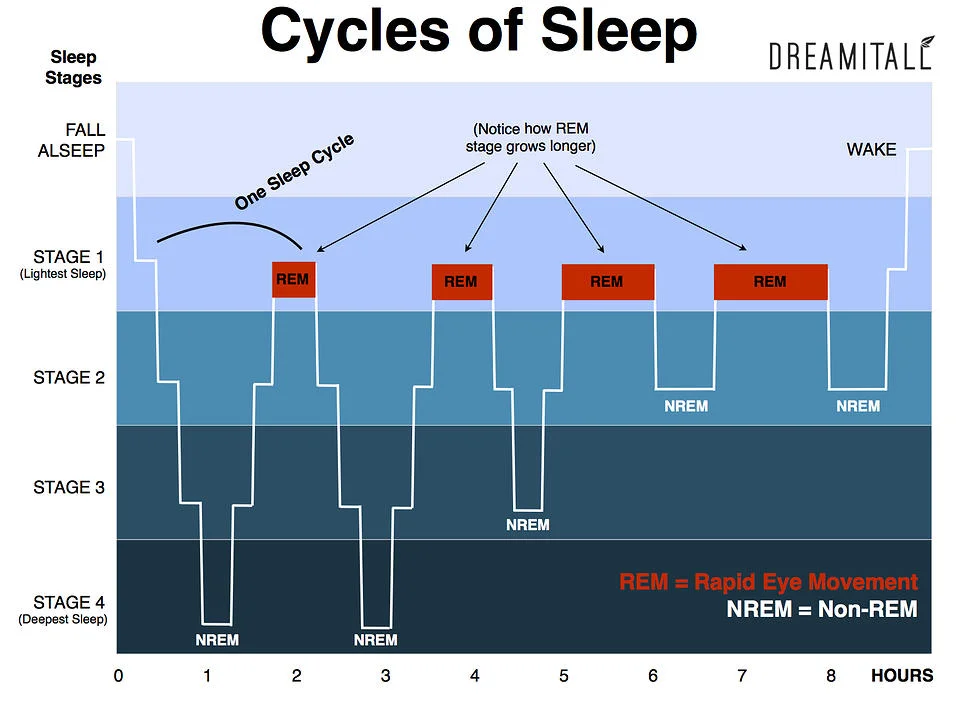

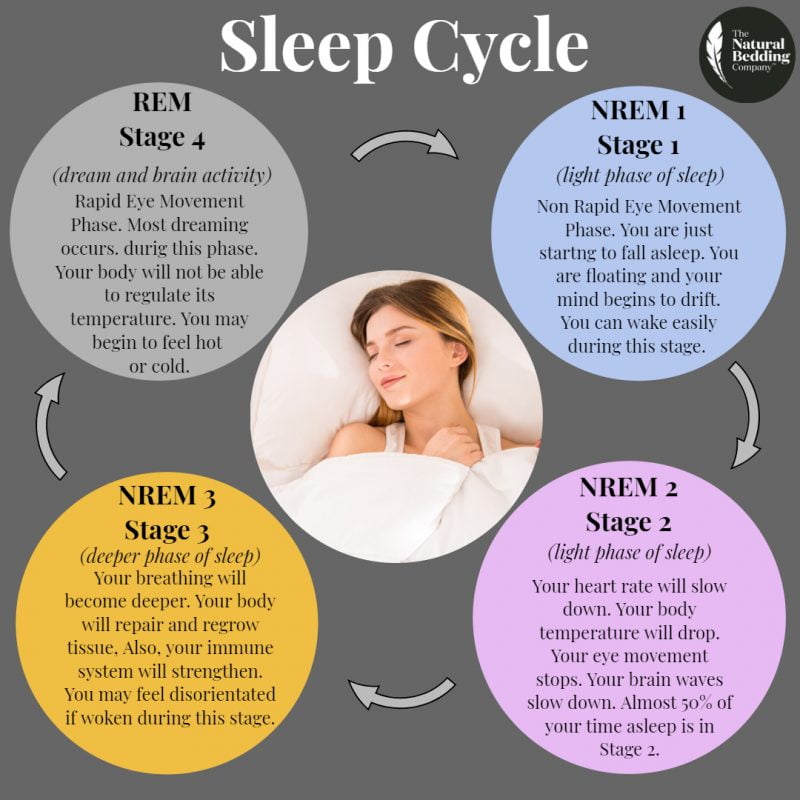

Involuntary rapid eye movements are called “nystagmus” by eye specialists. This term is of ancient Greek origin and literally means drowsiness, which quite accurately describes the nature of this phenomenon - rapid jumps of the eyes resemble the movements that they make during the REM phase of sleep.

The frequency of eyeball vibrations can reach several hundred times per minute, and the direction of these vibrations can vary, and there are cases of a mixed type. The most common eye movement is horizontal; vertical nystagmus is somewhat less common. Diagonal and rotational direction of movement are among the rarest forms of the disease.

Typically, nystagmus is accompanied by a sensitive deterioration in the patient's vision. It is necessary to distinguish involuntary eye movements from the usual ones that occur when observing the rapid movements of any objects. For example, a person watching the train cars passing by him looks very similar to a patient with horizontal nystagmus from the outside - his eyes make almost the same movements. The main difference is that in a patient, the movements of the eyeballs are observed on their own, without concentration on moving objects, and the frequency of oscillations is usually much higher.

Causes of involuntary movements

All causes of nystagmus can be divided into two groups - pathology can be congenital or acquired as a result of other diseases. Note that in any of these cases, the primary cause is a disturbance in the functioning of the motor apparatus of the eye. There are a number of factors and diseases that can influence the formation of nystagmus:

Note that in any of these cases, the primary cause is a disturbance in the functioning of the motor apparatus of the eye. There are a number of factors and diseases that can influence the formation of nystagmus:

- various eye diseases;

- infectious diseases of the ears;

- head injury, dysfunction of the vestibular apparatus;

- inflammatory diseases of different parts of the brain, pituitary gland;

- CNS overstrain;

- intoxication with drugs and other chemicals.

Symptoms

The main symptom of nystagmus is very rapid involuntary eye movements. This is what an outside observer can notice, and during such “attacks” the patient himself may feel blurry vision, blurry, flickering of what he is looking at, double vision, sometimes even feel dizzy.

Diagnosis and treatment of nystagmus

To make a diagnosis of nystagmus, an ophthalmologist will need to conduct a comprehensive examination of the retina, motor apparatus, fundus and general condition of vision.