Trichotillomania dsm v

Trichotillomania (hair-pulling Disorder): Causes, Symptoms, Treatment DSM-5 312.39 (F63.2)

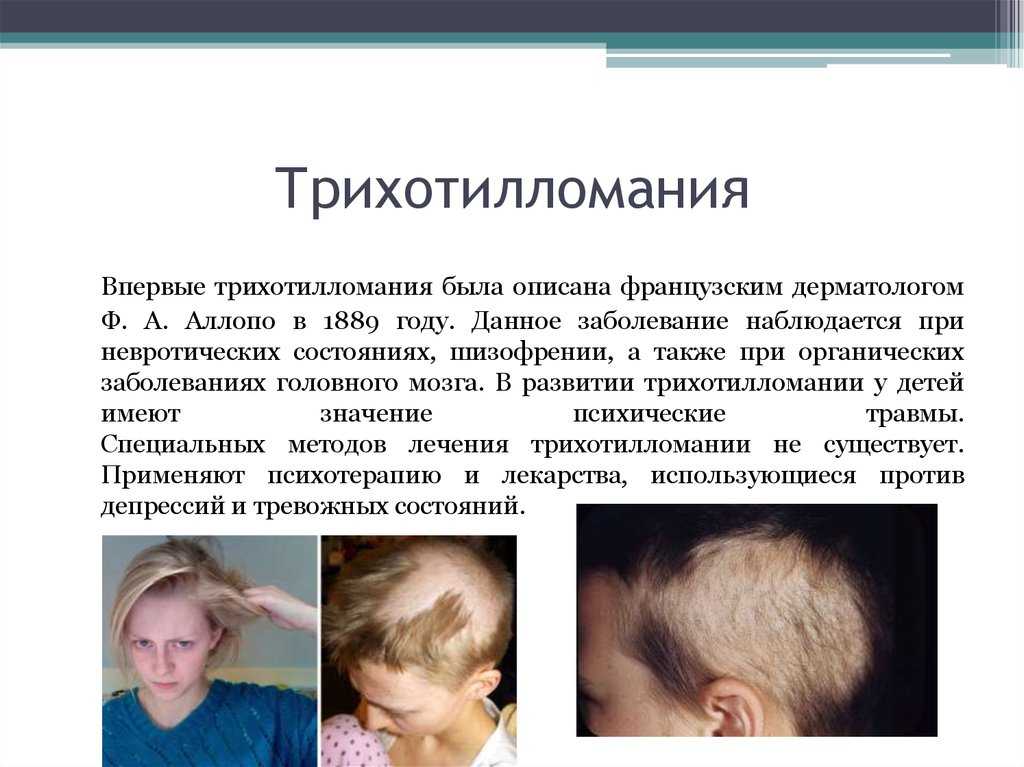

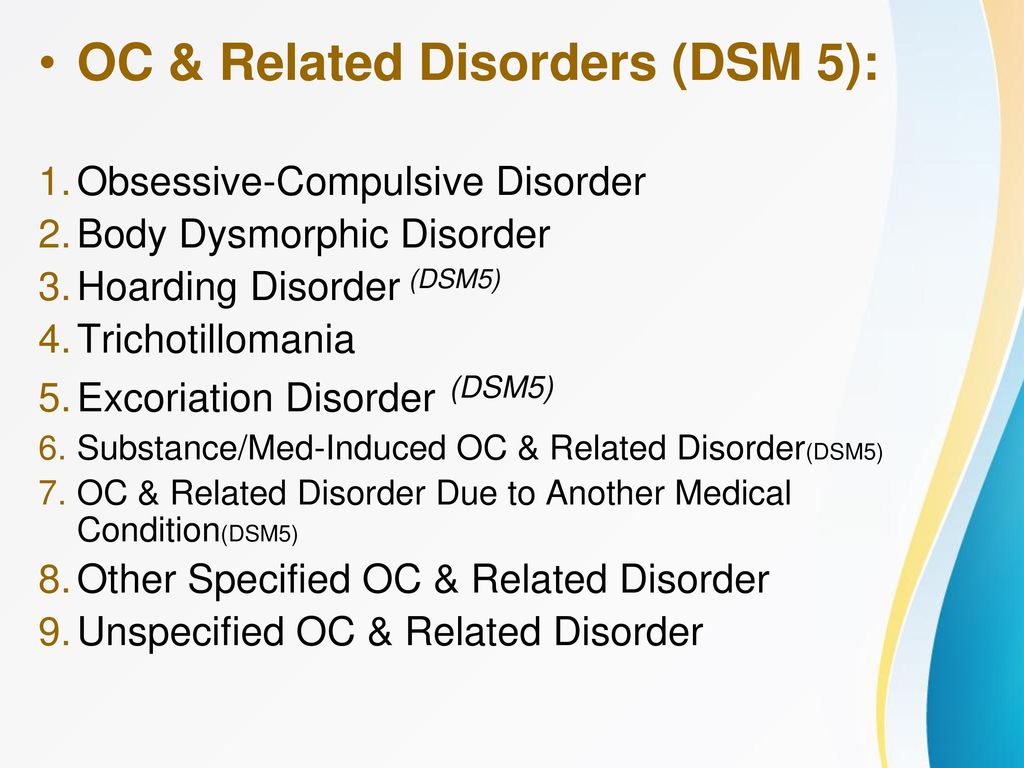

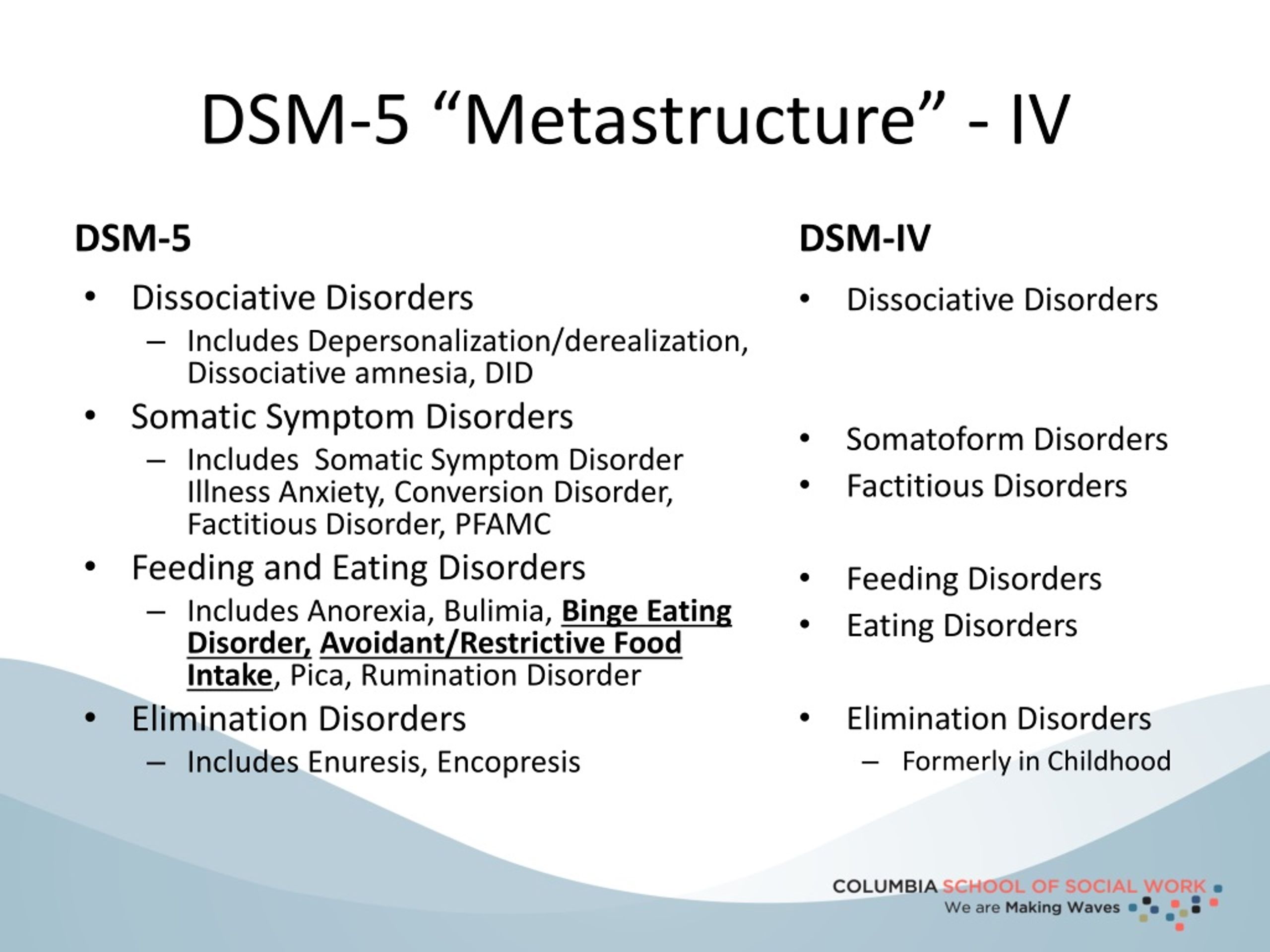

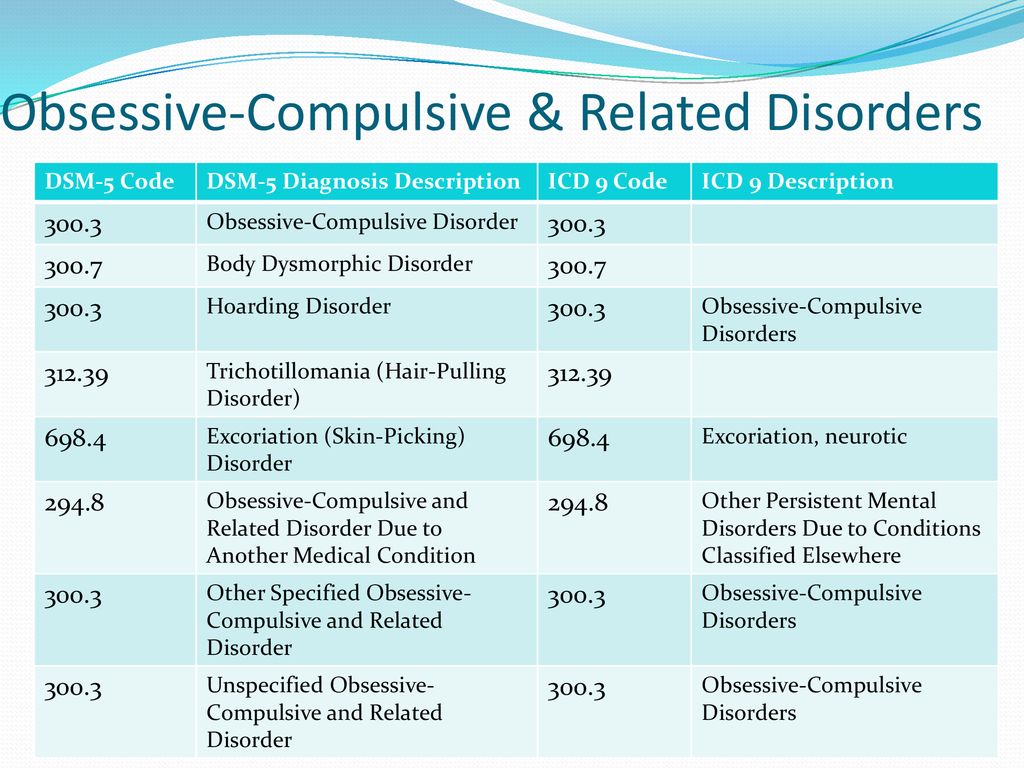

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), categorizes trichotillomania as an obsessive-compulsive or related disorder. Someone who suffers with the disorder pulls out their hair on a consistent basis, whether it be hair from the scalp, eyebrows, or any other region of their body. The individual may do this in short instances throughout the day or spend longer periods, hours even, hair-pulling. It can sometimes be difficult to notice when someone has this disorder if he or she pulls hair in a widely distributed fashion or conceals their hair loss with hats or makeup, for example.

Diagnostic Criteria for Determining Trichotillomania (Hair-Pulling Disorder) DSM-5 312.39 (F63.2)

Hair-pulling may come with a wide variety of rituals involving hair. However, the following are specific criteria that must be met in order for a trichotillomania diagnosis to be made:

- The individual pulls out his or her hair regularly, which results in hair loss.

- The individual makes a consistent effort to stop hair-pulling.

- The individual’s hair-pulling causes him or her clinically significant distress or impairment in their everyday life.

- The individual’s hair loss is not due to another medical condition.

- The individual’s hair-pulling is not attributable to symptoms of another mental disorder

Supporting Features

Individuals who suffer with trichotillomania can develop habits alongside hair-pulling such as examining the hair after pulling it out, eating the hair, and playing with the hair. A wide variety of emotions also follow the acts, including feelings of gratification or relief, while some alternatively cause them, such as anxiety and boredom.

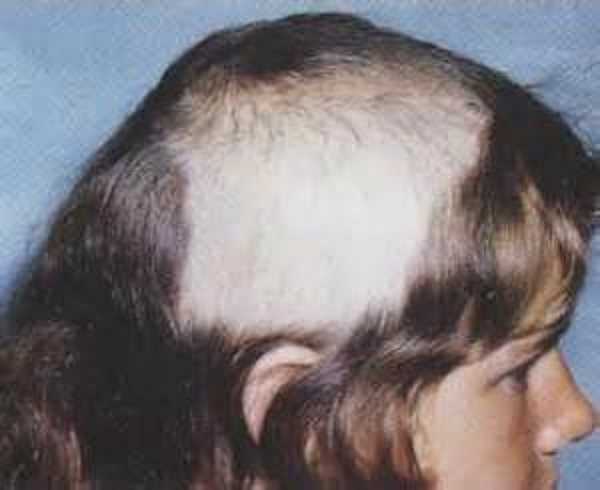

Certain individuals engage in hair-pulling without even realizing they’re doing it, while others become very focused on this task at hand. Whichever the case, hair loss is the outcome, though variable—for example, areas of hair may simply thin or completely bald. These individuals typically hide their hair-pulling habits from others as well as deny the acts when confronted.

These individuals typically hide their hair-pulling habits from others as well as deny the acts when confronted.

Who Is at Risk of Developing Trichotillomania (Hair-Pulling Disorder) DSM-5 312.39 (F63.2)?

Those at a greater risk of developing trichotillomania are individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and those who have close relatives who suffer from hair-pulling disorder. Otherwise, there is normal risk. In individuals that do develop trichotillomania, onset typically occurs during puberty. If they don’t get help for the disorder, it’s course will likely be chronic. Additionally, symptoms may worsen during hormonal changes in women, such as during menstruation or menopause. It is also possible for the disorder to come and go for any period of time.

Differential Diagnosis

Only careful analysis of the aforementioned criteria should result in a diagnosis of trichotillomania or hair-pulling disorder. This is due in part to the following possibly explaining the chronic hair-pulling:

-

Normative hair removal.

It is normal to engage in the standard cosmetic removal of hair, used to improve one’s appearance

It is normal to engage in the standard cosmetic removal of hair, used to improve one’s appearance - Other obsessive-compulsive or related disorders. For example, people with OCD may pull out hair as part of one of their rituals and those with body dysmorphic disorder may remove hair they find unappealing.

- Neurodevelopmental disorders. Hair-pulling may be the result of tics (though rarely), for example.

- Psychotic disorder. People who suffer with a psychotic disorder may pull out their hair during a hallucination or delusion.

- Another medical condition. Dermatological conditions, such as inflammation of the skin, may be to blame for the hair-pulling. And in individuals who deny hair-pulling but have a noticeable loss of hair, other causes of hair loss must be considered.

- Substance-related disorders. Though they’re unlikely to be the cause of hair-pulling, these substances may worsen it.

Is There Treatment for Trichotillomania (Hair-Pulling Disorder) DSM-5 312.39 (F63.2)?

A few different forms of therapy are available for those seeking treatment for hair-pulling:

- Cognitive Therapy: This form of therapy focuses on helping the individual identify and fix distorted beliefs related to their hair-pulling.

- Habit Reversal Training: Habit reversal training is a form of behavior therapy and is the primary treatment for hair-pulling disorder. It helps the individual recognize situations that lead to pulling his or her hair and introduces new, healthier behaviors to perform instead. For example, the therapist may suggest the individual try clenching their fists every time they have the urge to hair-pull.

- Acceptance and commitment therapy: This therapy focuses on helping the individual accept their hair-pulling tendencies and urges without actually acting on them.

Consequences of Hair-Pulling

Hair-pulling can have some irreversible as well as temporary effects on an individual, including:

- Social and occupational impairment

- Damage to hair growth and/or quality

- Abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting in cases that involve swallowing of the hair

- Digit purpura, musculoskeletal injury, and dental damage—rare, but possible

Trichotillomania Diagnosis and the DSM5

Tasneem Abrahams

Dec 28th, 2014

Online test

Find out the severity of your symptoms with this free online test

Take the test

It is not uncommon for people to subconsciously play with, twirl or pull at their hair when anxious, tired or bored, nor is it uncommon for people to routinely pull out grey hairs or split ends. For many repetitive hair pulling is just a bad habit that has no real impact on their daily lives. But for some, this practice can be so consuming that it starts to have a negative impact on day to day functioning, their social lives, and can cause significant emotional distress. In these instances, hair pulling has evolved from a bad habit into a recognized clinical disorder known as trichotillomania, or compulsive hair pulling disorder. Because of the poor awareness by the general public that such a disorder even exists, hair trichotillomania often goes undiagnosed and therefore untreated, with many sufferers suffering in silence for many years.

For many repetitive hair pulling is just a bad habit that has no real impact on their daily lives. But for some, this practice can be so consuming that it starts to have a negative impact on day to day functioning, their social lives, and can cause significant emotional distress. In these instances, hair pulling has evolved from a bad habit into a recognized clinical disorder known as trichotillomania, or compulsive hair pulling disorder. Because of the poor awareness by the general public that such a disorder even exists, hair trichotillomania often goes undiagnosed and therefore untreated, with many sufferers suffering in silence for many years.

How will I know if I have hair pulling disorder?

There is such a fine line between hair pulling as a bad habit and the onset of a clinical diagnosis that is is often shrugged off and dismissed by those affected by it, as well as by health professionals who are not knowledgable about trichotillomania, and perceived as a habit the person simply needs to 'get over'. Yet when the behviour has escalated to the level of a diagnosis, this is exactly what they struggle with most. One of the key clues that behaviour may have a clinical component is if the individual has tried to stop pulling on several occassions and failed, often leading to the beaviour actually increasing as a result. Some of the warning signs that hair pulling is affecting your function include:

Yet when the behviour has escalated to the level of a diagnosis, this is exactly what they struggle with most. One of the key clues that behaviour may have a clinical component is if the individual has tried to stop pulling on several occassions and failed, often leading to the beaviour actually increasing as a result. Some of the warning signs that hair pulling is affecting your function include:

- Not being able to go out in public without covering up the pulling site, e.g. wearing hats, scarves, sunglasses

- Avoidance of social situations when conditions are windy or wet, e.g. swimming

- Constantly being late due to spending extended periods of time pulling

- Feeling you are not in control of the ability to stop pulling

Do I Have Trichotillomania?

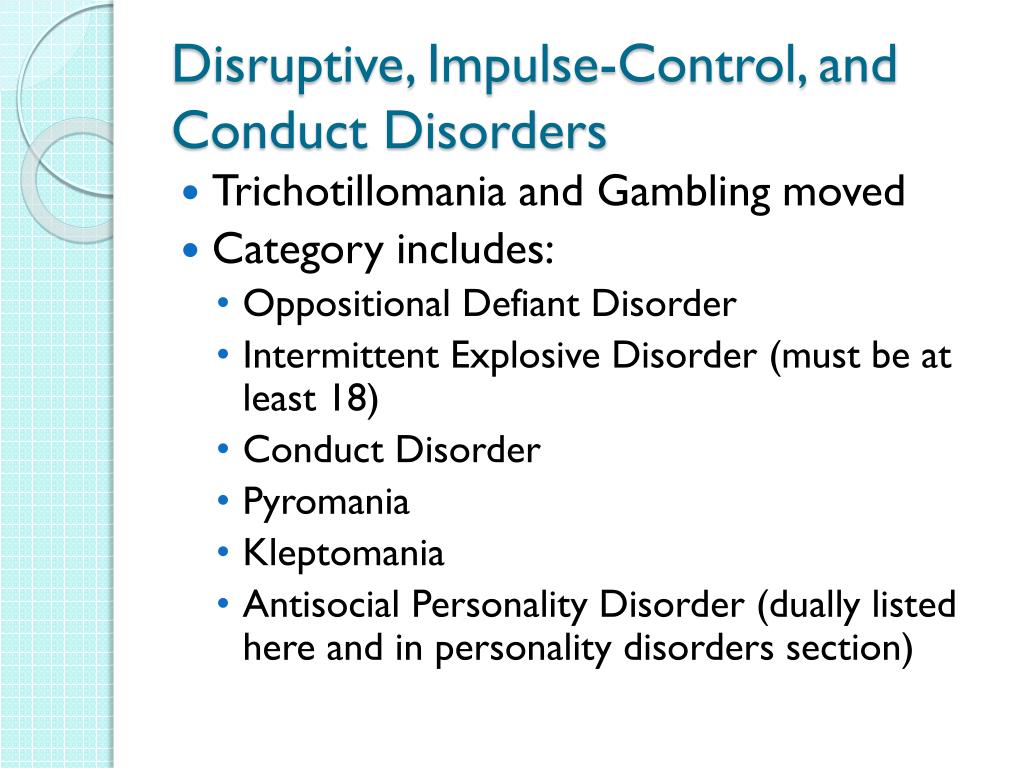

Classification and the DSM

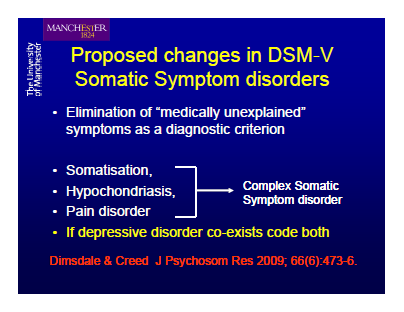

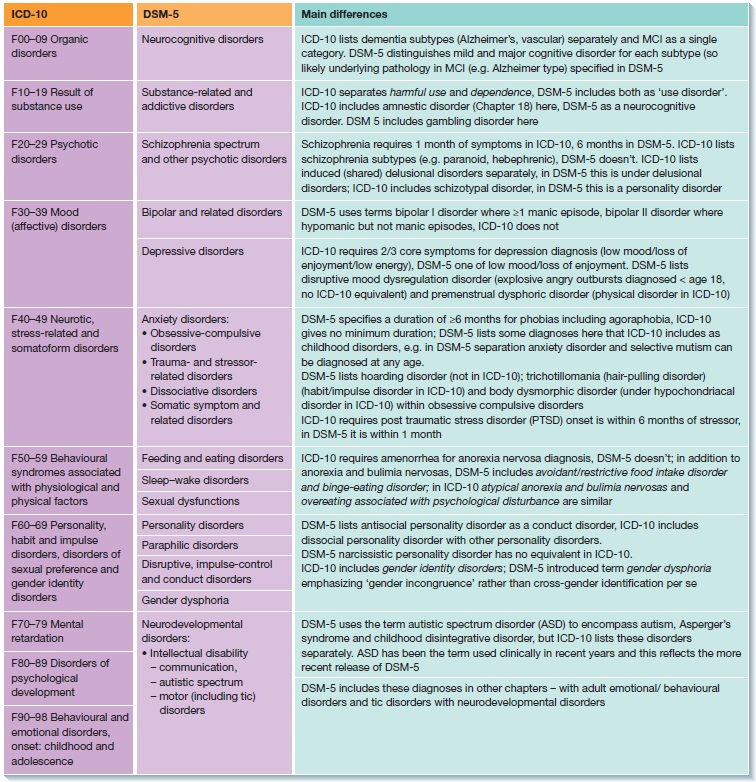

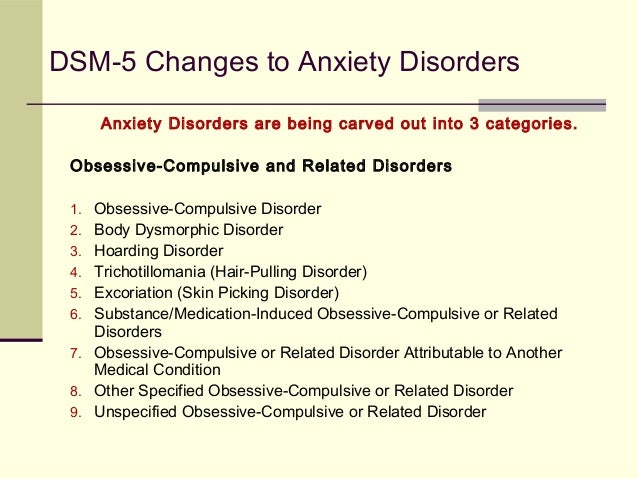

In a previous article on this site we outlined the history of trichotillomania classification in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of the American Psychiatric Association. Trichotillomania was only first recognized in the DSM-III Revised edition (DSM-III-R) in 1987. Since then the diagnostic criteria have been revised to the current version found in the DSM-5. The DSM-5 clearly differentiates hair pulling as a disorder from other non-clinical hair pulling behaviours. For example it states that “Trichotillomania should not be diagnosed when hair removal is performed solely for cosmetic purposes”. The DSM-5 also recognizes the diversity of the disorder, so one cannot determine whether you have trichotillomania solely by comparison to others who have the disorder. The DSM-5 characterizes trichotillomania by recurrent repetitive behaviour (hair pulling) and repeated attempts to decrease or stop the behaviour. The behaviour can occur during both relaxed and stressful times, but there is often a mounting sense of tension before hair pulling occurs or when attempts are made to resist the behaviour. Trichotillomania is categorized under obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (OCRD) and the criteria for diagnosis are as follows:

Trichotillomania was only first recognized in the DSM-III Revised edition (DSM-III-R) in 1987. Since then the diagnostic criteria have been revised to the current version found in the DSM-5. The DSM-5 clearly differentiates hair pulling as a disorder from other non-clinical hair pulling behaviours. For example it states that “Trichotillomania should not be diagnosed when hair removal is performed solely for cosmetic purposes”. The DSM-5 also recognizes the diversity of the disorder, so one cannot determine whether you have trichotillomania solely by comparison to others who have the disorder. The DSM-5 characterizes trichotillomania by recurrent repetitive behaviour (hair pulling) and repeated attempts to decrease or stop the behaviour. The behaviour can occur during both relaxed and stressful times, but there is often a mounting sense of tension before hair pulling occurs or when attempts are made to resist the behaviour. Trichotillomania is categorized under obsessive-compulsive and related disorders (OCRD) and the criteria for diagnosis are as follows:

- Recurrent hair pulling or plucking resulting in visible hair loss

- Repeated attempts to decrease or stop hair pulling

- The hair pulling causes clinically significant distress or impairment in social, occupation, or other important areas of functioning

- The hair pulling is not attributable to the psychological effects of a substance (e.

g., cocaine) or another medical condition (e.g., scabies)

g., cocaine) or another medical condition (e.g., scabies) - The hair pulling is not better explained by symptoms of another mental disorder (e.g., delusions or tactile hallucinations in a psychotic disorder, attempts to improve a perceived defect or flaw in appearance in body-dysmorphic disorder, stereotypes in stereotypic movement disorder, or intention to harm oneself in non-suicidal self-injury)

The inclusion of trichotillomania as well as excoriation (skin picking) disorder in the DSM5 indicate huge progress in the awareness and understanding of the condition. However there is still a long way to go with a working group being tasked to make recommendations for the classification of these conditions in the eleventh edition of the International Classification of Disease (ICD-11), which is the global classification of disease endorsed by the World Health Organization (WHO). A recently published report by members of the working group recommended that consideration be made for the classification of trichotillomania and excoriation disorder in a unique category of body-focussed repetitive behaviors (BFRBs) along with the other BFRBs in both the ICD and the DSM, whilst maintaining the definition presently used in the DSM5. This is because it is widely accepted that trichotillomania and skin picking disorder most closely resembles characteristics of the other BFRBs. Currently trichotillomania and excoriation disorder are categorized under obsessive compulsive and related disorders, while body-focussed repetitive behaviours such as onychphagia are categorized under "Other Specified and Unspecified Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders".

This is because it is widely accepted that trichotillomania and skin picking disorder most closely resembles characteristics of the other BFRBs. Currently trichotillomania and excoriation disorder are categorized under obsessive compulsive and related disorders, while body-focussed repetitive behaviours such as onychphagia are categorized under "Other Specified and Unspecified Obsessive-Compulsive and Related Disorders".

Awareness is Key!

What is clear is that there are definitive guidelines for the diagnosis of these conditions and that health professionals should be educated to identify the signs and symptoms in their patients, and the stigma attached to these behaviors need to be addressed to ensure that more people are diagnosed sooner and receive the help they need.

Tasneem Abrahams

Online test

Find out the severity of your symptoms with this free online test

Take the test

Speak Life: Words are powerful.

Trudi Griffin - LPC | 27 Nov, 2018

Teens Dealing With Trichotillomania (Hair Pulling Disorder)

Tasneem Abrahams | 27 Mar, 2016

Does pulled out hair grow back?

Tasneem Abrahams | 25 Feb, 2017

What to do if your parents or guardians refuse to let you have access to mental healthcare

Tasneem Abrahams | 28 May, 2017

Start your journey with TrichStop

Take control of your life and find freedom from hair pulling through professional therapy and evidence-based behavioral techniques.

Start Now

Trichotillomania, or compulsive hair-pulling

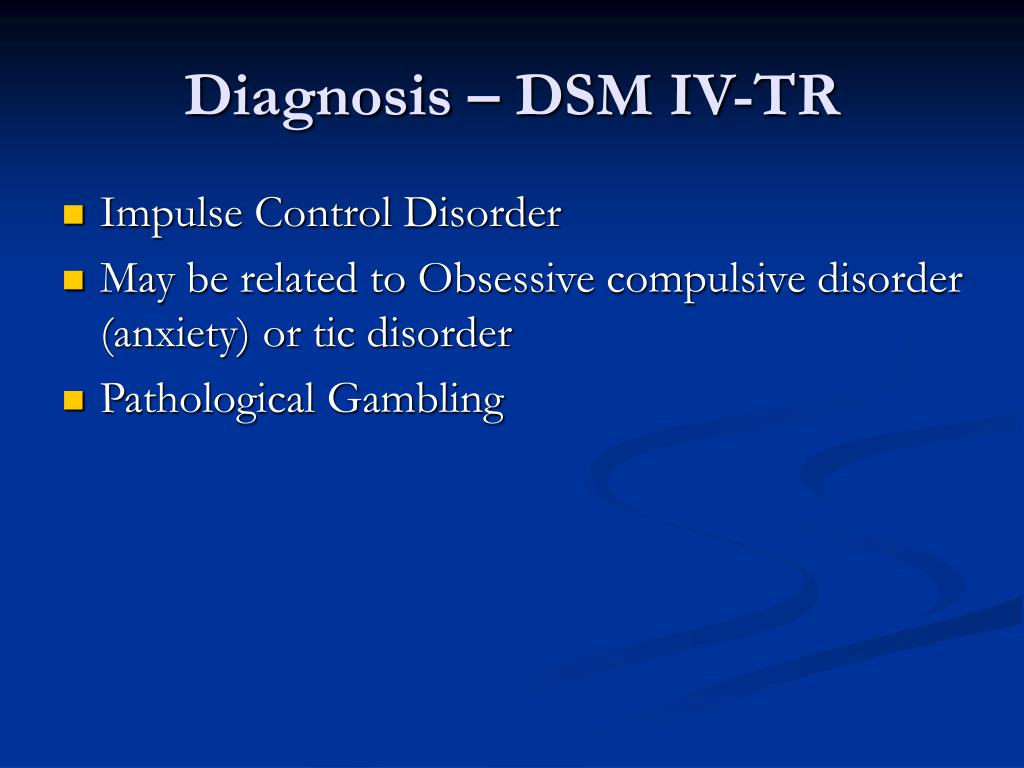

Disorders such as pathological gambling, pyromania (which I have already discussed in a previous article), kleptomania, and intermittent explosive disorder were only diagnosed in the DSM III (American Psychiatric Association). , 1980). Only seven years later, the DSM III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) also gave trichotillomania diagnostic value.

, 1980). Only seven years later, the DSM III-R (American Psychiatric Association, 1987) also gave trichotillomania diagnostic value.

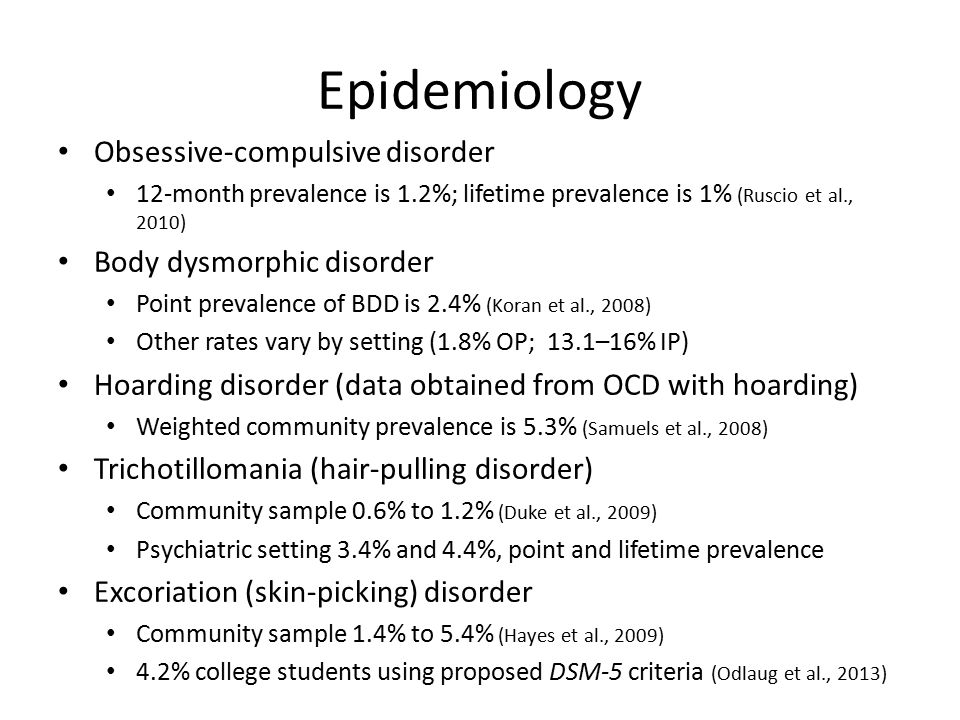

Hair pulling usually begins shortly before or after puberty. At any given time, about 1-2% of people have this condition. nine0003

About 80-90% of adults with trichotillomania are women.

Trichotillomania, or hair-pulling disorder, is characterized by excessive and repetitive hair-pulling or hair-pulling behavior.

The patient may exhibit this behavior for short, repetitive periods of time during the day or less often, but in this case the duration of the episode may last for hours.

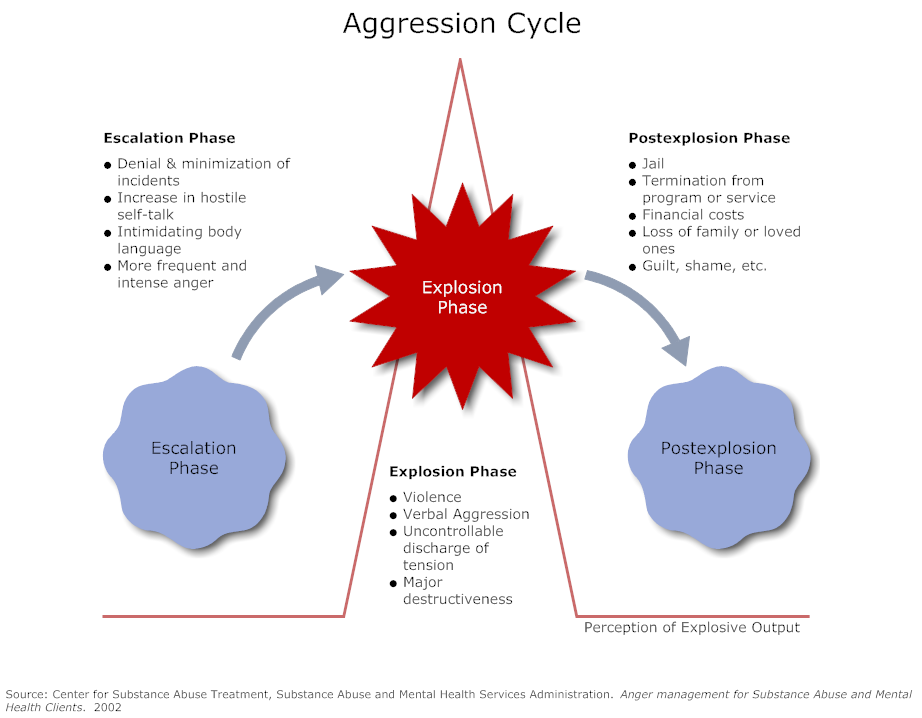

Before and during seizures, people may experience a variety of strong emotions such as anxiety, boredom, excitement, as well as pleasure and relief at the moment of pulling hair or hair. nine0003

Most people with trichotillomania also have other repetitive body activities such as skin picking, nail or lip biting.

SYMPTOMS PRESENT IN PEOPLE WITH TRICHOTILLOMANIA

- Periodic hair-pulling or hair-pulling resulting in hair loss;

- Repeated attempts to reduce or stop this behavior;

- Disturbance and impairment of normal functioning in important areas of life, such as social and professional.

nine0024

nine0024

Many people with trichotillomania have other repetitive activities such as nail biting or skin picking.

The disorder is very common in people with symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD).

These trichotillomania symptoms may persist for months or even years.

In most cases, the onset occurs in adolescence and is chronic.

TRICHOTILLOMANIA: CONSEQUENCES OF THE DISEASE

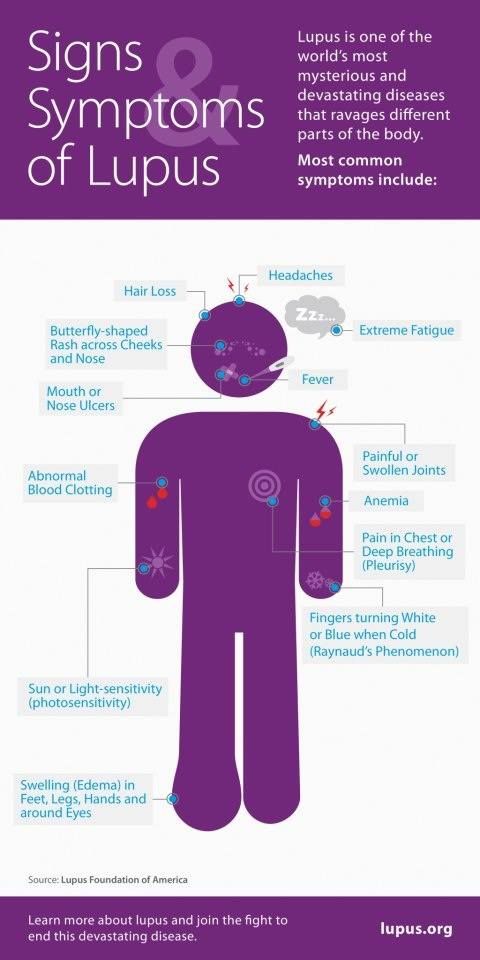

Plucking hair, hair, eyelashes and eyebrows can cause irritation and injury, and in some cases irreversible deterioration in hair growth or quality.

Usually this also leads to a deterioration in work and social life, as the person is ashamed of his image and isolates himself.

In addition, if hair is swallowed, a number of gastrointestinal problems may occur, such as nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, intestinal obstruction and perforation.

TREATMENT OF TRICHOTILLOMANIA

An effective treatment for trichotillomania is cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), which helps to identify and change the thought patterns that determine behavior; increase the patient's awareness of their behavior; identify and implement alternative behavior; and deal with anxiety and stress.

Article written by Dr. Letizia Ciabattoni

Read also:

Impulse control disorders: kleptomania

Impulsive control disorders: ludopathy or gambling disorder

Facebook, social media addiction and narcissistic personality traits

sources:

https://istitutodineuroscienze.it/index.php/tricotillomania/

www.msdmanuals.com/it-it/professionale/disturbi-psichiatrici/disturbo-ossessivo-compulsivo-e-disturbi-correlati/tricotillomania

https://www.psicoterapiascientifica.it/tricotillomania/

https://centroclinicocrocetta.it/psicoterapia-cognitiva/tag/tricotillomania/

Grant J.E., Odlaug B.L., Kim S.W.: N-acetylcysteine, a glutamate modulator, in the treatment of trichotillomania: dual blind placebo-controlled study. Arch Gen Psychiatry 66 (7): 756–763, 2009. doi: 10.1001 / archgenpsychiatry.2009.60

Bloch MH, Panza KE, Grant JE, et al: N-acetylcysteine in the treatment of pediatric trichotillomania: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled adjunctive study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52(3):231–240, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.12.020

J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 52(3):231–240, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.12.020

Biondi M. (kura di) (2014). DSM-5. A guide to the diagnosis and statistics of mental disorders. Raffaello Cortina Editore, Milan.

Nardone G., Portelli K. (2013). Ossessioni compulsioni manie. Capirle e sconfiggerle in tempi brevi. Ponte alle Grazie, Milan.

Kaplan. Clinical Psychiatry >> TRICHOTILLOMANIA DEFINITION AND DIAGNOSIS According to DSM - III

TRICHOTILLOMANIA DEFINITION AND DIAGNOSIS According to DSM - III - R, an essential feature of trichotillomania is the recurrent inability to resist pulling out one's hair. The diagnosis should not be made when the hair-pulling is associated with a previous inflammation of the skin or when it occurs in response to delusions or hallucinations. The following are diagnostic criteria for trichotillomania. AND. An intermittent inability to resist impulses to pull out one's own hair, resulting in a great reduction in the number of hairs. B. Increased feeling of tension just before pulling out the hair. AT. Satisfaction or feeling of relief during hair pulling. G. Lack of association with pre-existing skin inflammations, as well as with delusions and hallucinations. nine0003

B. Increased feeling of tension just before pulling out the hair. AT. Satisfaction or feeling of relief during hair pulling. G. Lack of association with pre-existing skin inflammations, as well as with delusions and hallucinations. nine0003

EPIDEMIOLOGY According to DSM - III - R, trichotillomania appears to be more common in women. There is no information on the influence of heredity on this disorder, although one study in children showed that 5 of 19 subjects had a history of baldness. No prevalence data are available, but trichotillomania may be more common than thought. It is more common in mentally retarded individuals and may be more common in patients with schizophrenia and those with borderline personality disorders. It is also noted that this disorder is more common in the first or only child in the family. The disorder usually begins in childhood but can occur at any age. nine0003

ETIOLOGY According to DSM - III - R, trichotillomania is considered as, its onset is associated with stressful situations in more than 1/4 of cases. Disruption of the mother-child bond, fear of being alone, and recent bereavement are considered critical contributing factors to this disorder. Substance abuse can also contribute to the development of this disorder. Often a predisposing factor is depressive dynamics. Some authors consider hair pulling as a variant of self-stimulation. nine0003

Disruption of the mother-child bond, fear of being alone, and recent bereavement are considered critical contributing factors to this disorder. Substance abuse can also contribute to the development of this disorder. Often a predisposing factor is depressive dynamics. Some authors consider hair pulling as a variant of self-stimulation. nine0003

CLINICAL FEATURES According to DSM - III - R, before the onset of pathological behavior, the subject experiences tension, and as a result of hair pulling, a feeling of relief and satisfaction occurs. All areas of the body may be affected. The most common location is the scalp. Frequent localization are also eyebrows, eyelashes and beard, less frequent - torso, armpits and navel. No pathological features on the skin are found. Trichophagia, or trapping of hair in the mouth, may follow hair-pulling. As a rule, hair pulling is not accompanied by pain, although itching and burning sensation may occur in the affected areas. nine0003

Hair follicles show characteristic purely pathological changes known as trichomalacia, which can be detected on biopsy and help distinguish trichotillomania from other forms of alopecia. Patients usually do not admit that they are pulling out their hair, and often hide the cause of baldness. This disorder may include head bobbing, nail biting, skin scratching, skin gnawing and peeling, and other self-stimulating activities. nine0003

Patients usually do not admit that they are pulling out their hair, and often hide the cause of baldness. This disorder may include head bobbing, nail biting, skin scratching, skin gnawing and peeling, and other self-stimulating activities. nine0003

COURSE AND PROGNOSIS Trichotillomania is usually a childhood disorder, but it can sometimes begin in late adolescence. Some believe that if this disorder begins in adults, this is evidence in favor of the presence of psychosis in them. According to DSM - III - R, the dynamics of this disorder is poorly understood. There are reports that in some cases it can last more than two decades. Persons seeking medical help note that the disorder lasts for about a year or less, with frequent exacerbations and remissions. DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS According to the DSM-III-R, manipulation and play with one's hair are common and normal events. In obsessive-compulsive disorders, this behavior is of particular importance; it must prevent or cause certain events or situations in the future. Patients with an artificially demonstrated disorder with somatic manifestations actively turn to doctors, play a role and deliberately simulate this disease. Patients with stereotypical or ritual disorders have stereotypical or rhythmic movements and are not distressed by these manifestations. This condition is difficult to distinguish from focal alopecia. nine0003

Patients with an artificially demonstrated disorder with somatic manifestations actively turn to doctors, play a role and deliberately simulate this disease. Patients with stereotypical or ritual disorders have stereotypical or rhythmic movements and are not distressed by these manifestations. This condition is difficult to distinguish from focal alopecia. nine0003

TREATMENT There is no consensus on the treatment of trichotillomania. It is usually carried out with the participation of psychiatrists and dermatologists who work together. Of the psychopharmacological methods used to treat psychodermatological disorders, hydroxycin hydrochloride is used, an anxiolytic with dual properties - anxiolytic and antihistamine, antidepressants and antipsychotics. Many psychotropic substances are used to treat dermatological diseases and their effect once again proves the involvement of emotional factors in this pathology. When antidepressants are used for depression, the skin condition sometimes improves.