Trauma disorder dsm 5

Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in the DSM-5: Controversy, Change, and Conceptual Considerations

Behav Sci (Basel). 2017 Mar; 7(1): 7.

Published online 2017 Feb 13. doi: 10.3390/bs7010007

,1,2,*,1,2 and 2,3

Scott J. Hunter, Academic Editor

Author information Article notes Copyright and License information Disclaimer

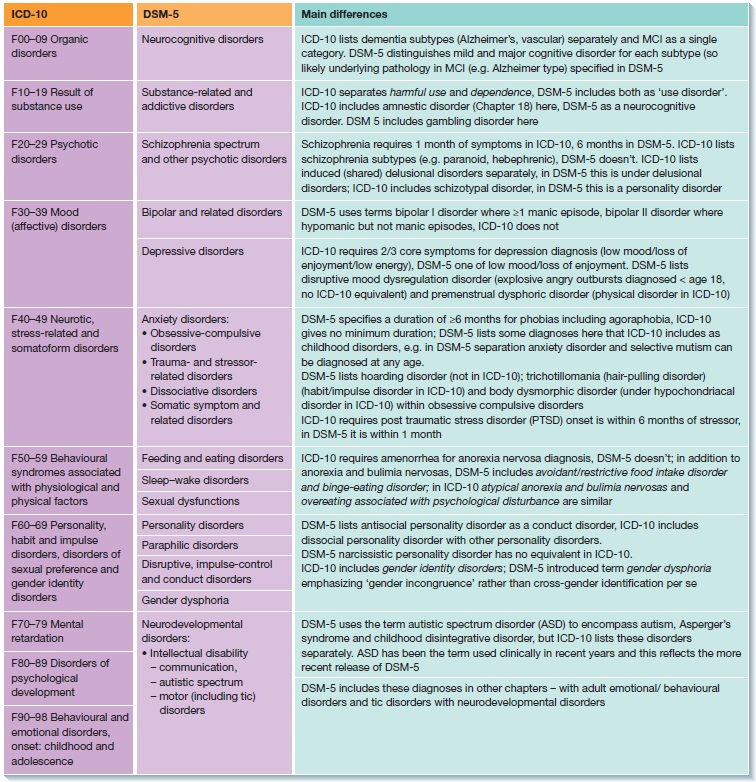

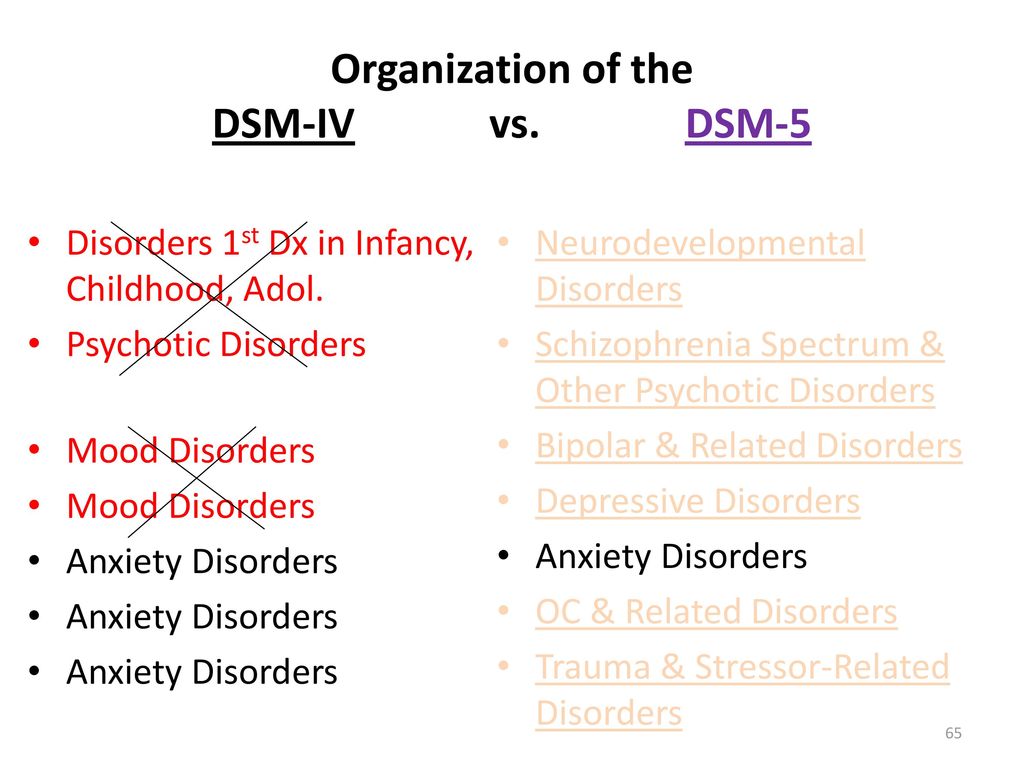

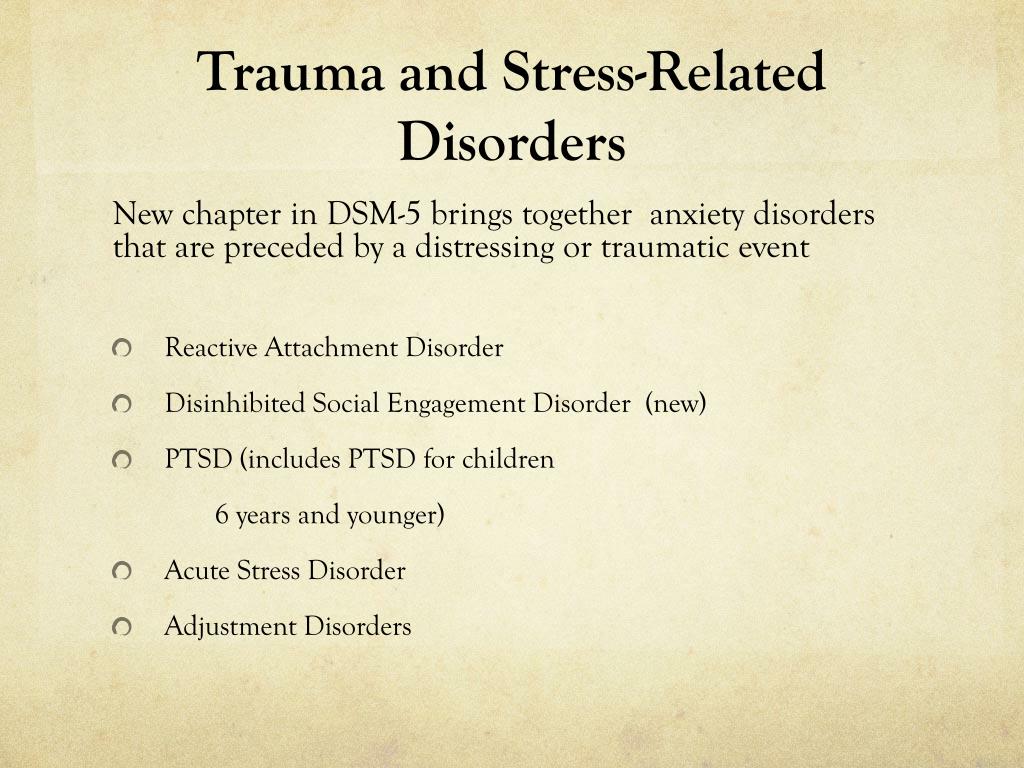

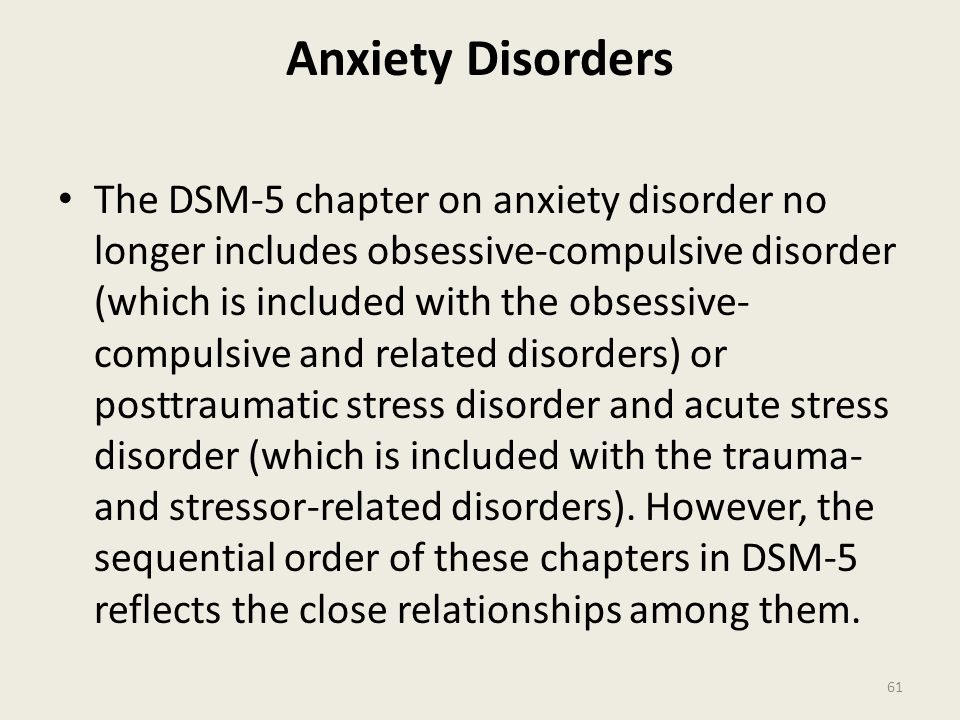

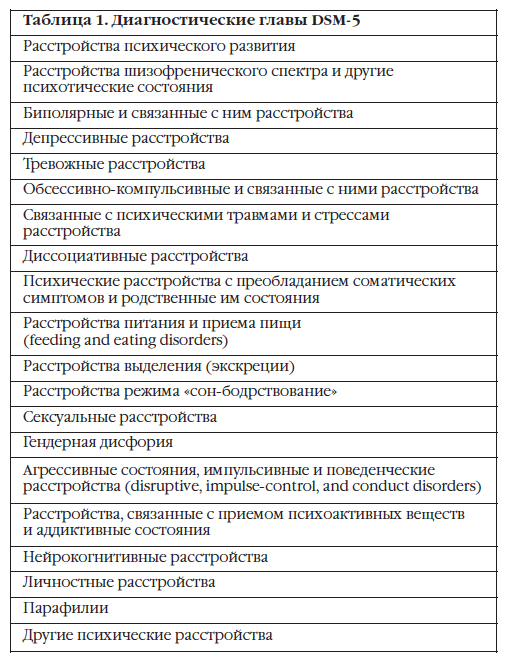

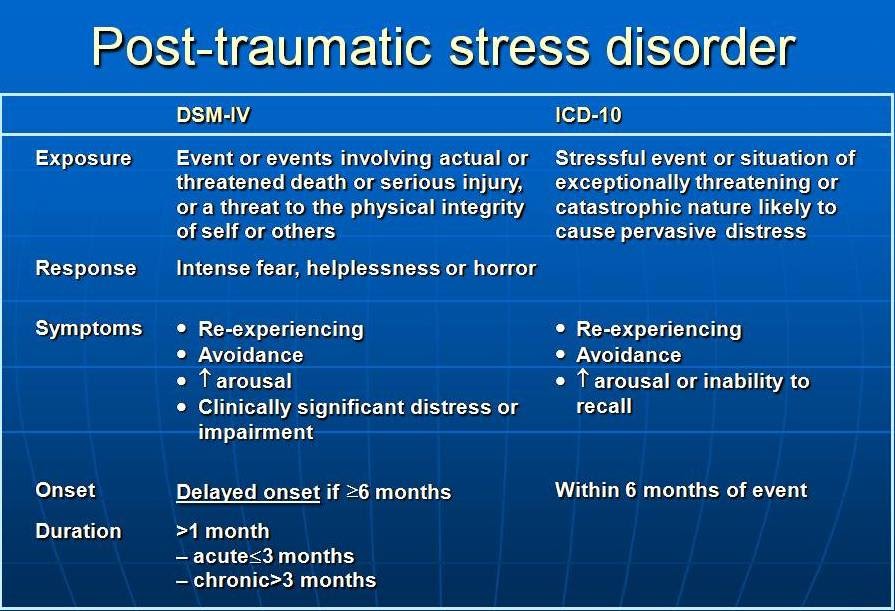

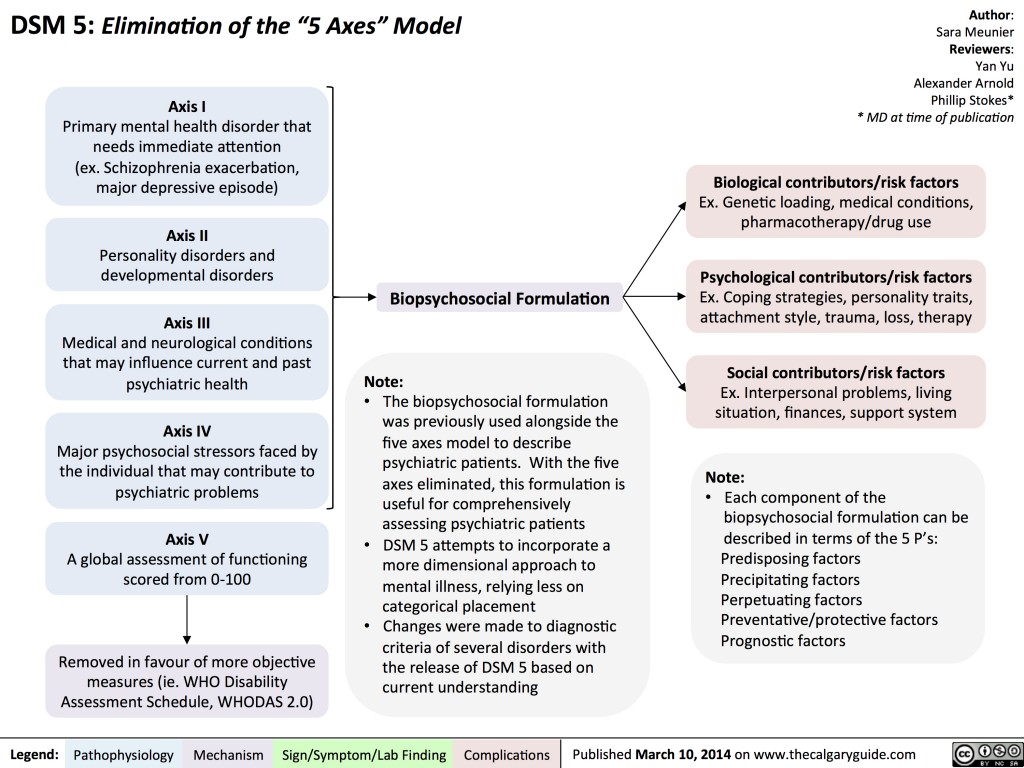

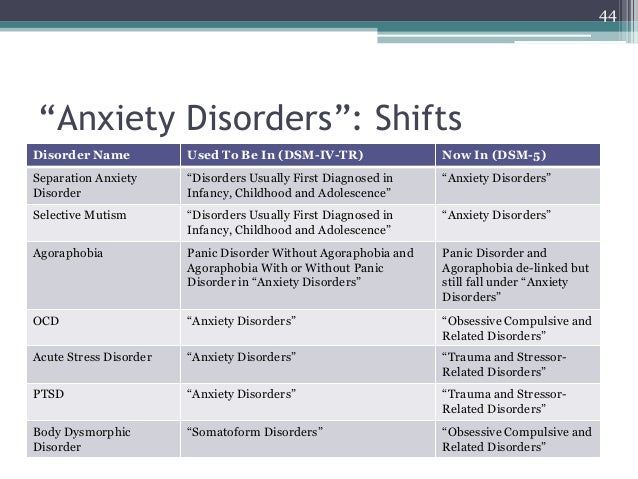

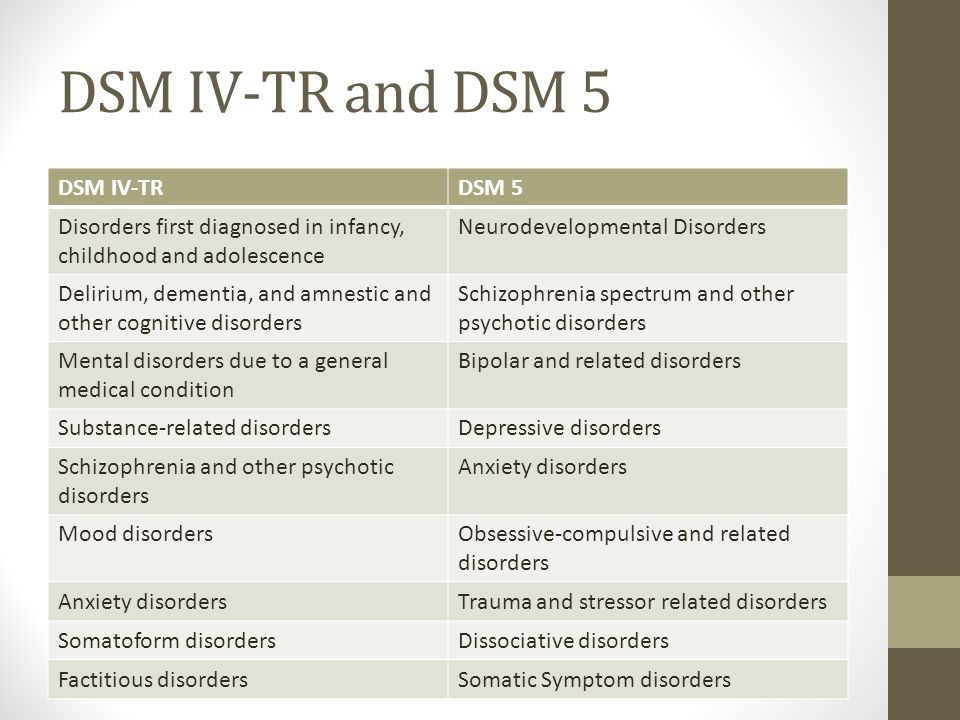

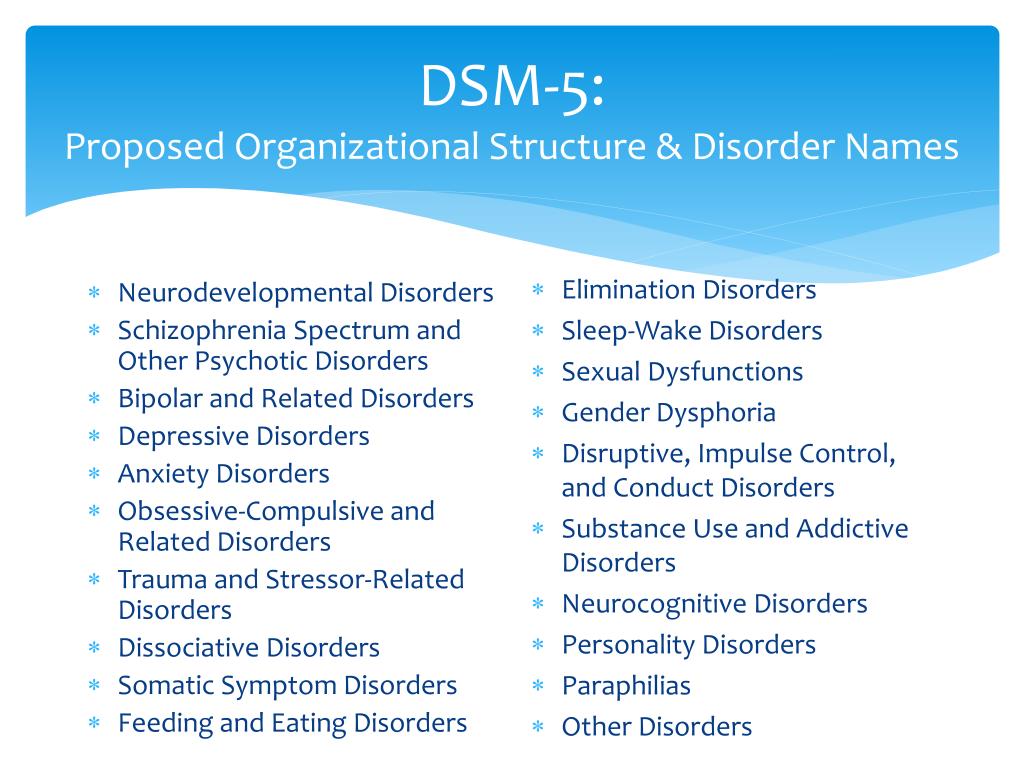

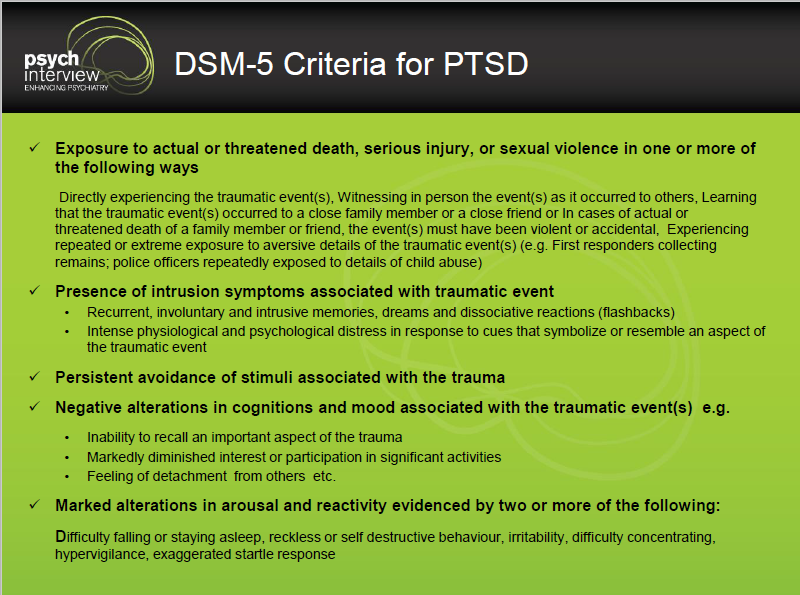

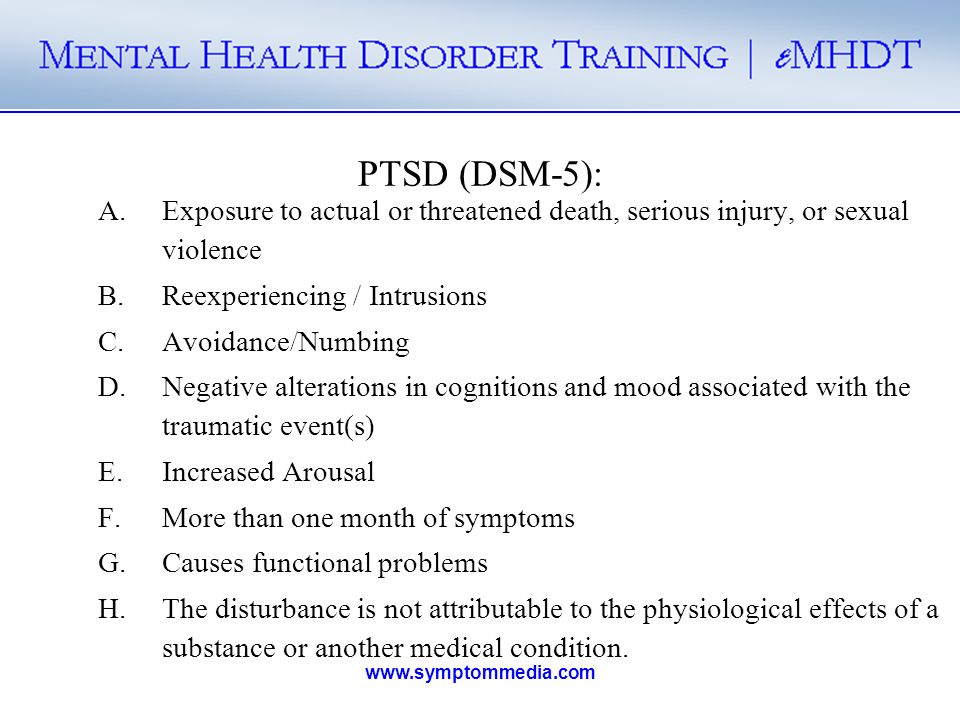

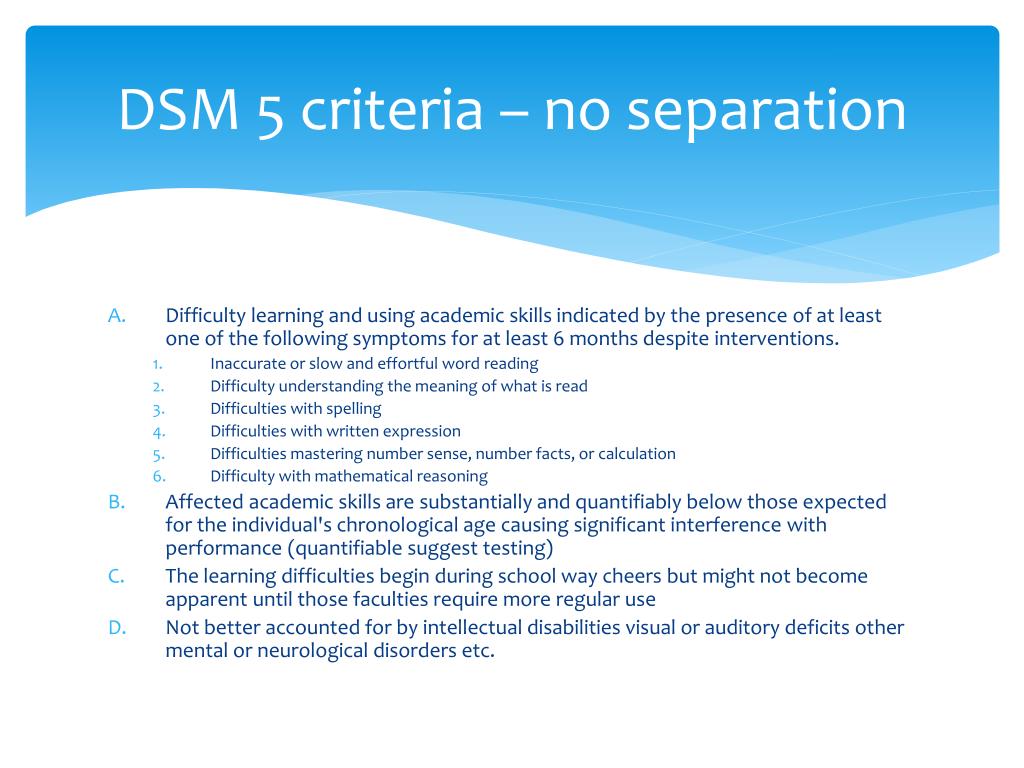

The criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder PTSD have changed considerably with the newest edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). Changes to the diagnostic criteria from the DSM-IV to DSM-5 include: the relocation of PTSD from the anxiety disorders category to a new diagnostic category named “Trauma and Stressor-related Disorders”, the elimination of the subjective component to the definition of trauma, the explication and tightening of the definitions of trauma and exposure to it, the increase and rearrangement of the symptoms criteria, and changes in additional criteria and specifiers.

This article will explore the nosology of the current diagnosis of PTSD by reviewing the changes made to the diagnostic criteria for PTSD in the DSM-5 and discuss how these changes influence the conceptualization of PTSD.

Keywords: posttraumatic stress disorder, psychiatric diagnosis, diagnostic criteria, nosology, trauma, DSM-5

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) has attracted controversy since its introduction as a psychiatric disorder in the third edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA) Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-III) in 1980 [1]. With each revision of the DSM, the criteria for PTSD have changed substantially [2]. Following publication of the fourth edition of the DSM (DSM-IV) in 1994 [3], PTSD experts criticized the criteria extensively, proposing myriad ways to address the problems they identified [4,5,6,7]. The literature accumulating during this time presented various polemical arguments concerning the definition of trauma and even questioning the need for it in the definition of PTSD [5,6,8], which and how many symptoms to include in the PTSD criteria and how they should be grouped [8], and even whether PTSD is a valid diagnosis at all [9]. Although the subsequent DSM-IV text revision edition of the manual (DSM-IV-TR) revised the text accompanying the criteria, the diagnostic criteria for PTSD did not change in this version. Therefore, this article will refer to these two versions together as DSM-IV/-TR.

Although the subsequent DSM-IV text revision edition of the manual (DSM-IV-TR) revised the text accompanying the criteria, the diagnostic criteria for PTSD did not change in this version. Therefore, this article will refer to these two versions together as DSM-IV/-TR.

The fifth edition (DSM-5) of the criteria required seven years of planning, six years of actual work group activity, and a year to finalize the materials for publication and obtain the approval of the APA Assembly and Board of Trustees. The revision efforts included an extensive review of literature, secondary analyses, professional presentations and town halls, vigorous debates among trauma experts and nosologists, and rounds of public and professional reviews of the proposed criteria [10,11]. This was described as a “very conservative approach” [12] (p. 548), with the appreciation that because important clinical and scientific consequences could result from any modifications to the diagnostic criteria, the work group needed to have very strong evidence before making any changes. Regardless, the changes in the diagnostic criteria for PTSD from DSM-IV/-TR to DSM-5 were substantial.

Regardless, the changes in the diagnostic criteria for PTSD from DSM-IV/-TR to DSM-5 were substantial.

This article will explore the nosology of the current diagnosis of PTSD. Specifically, it will critically examine the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD, review changes in the criteria made in the DSM-5, and consider how the criteria shape current conceptualizations of PTSD.

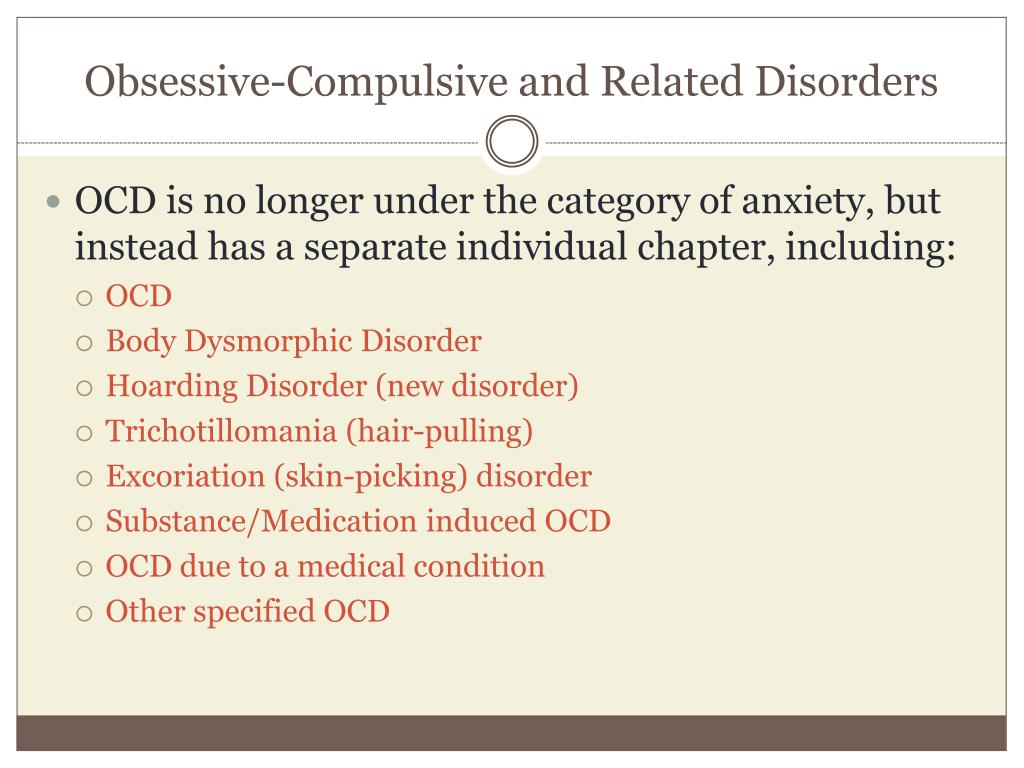

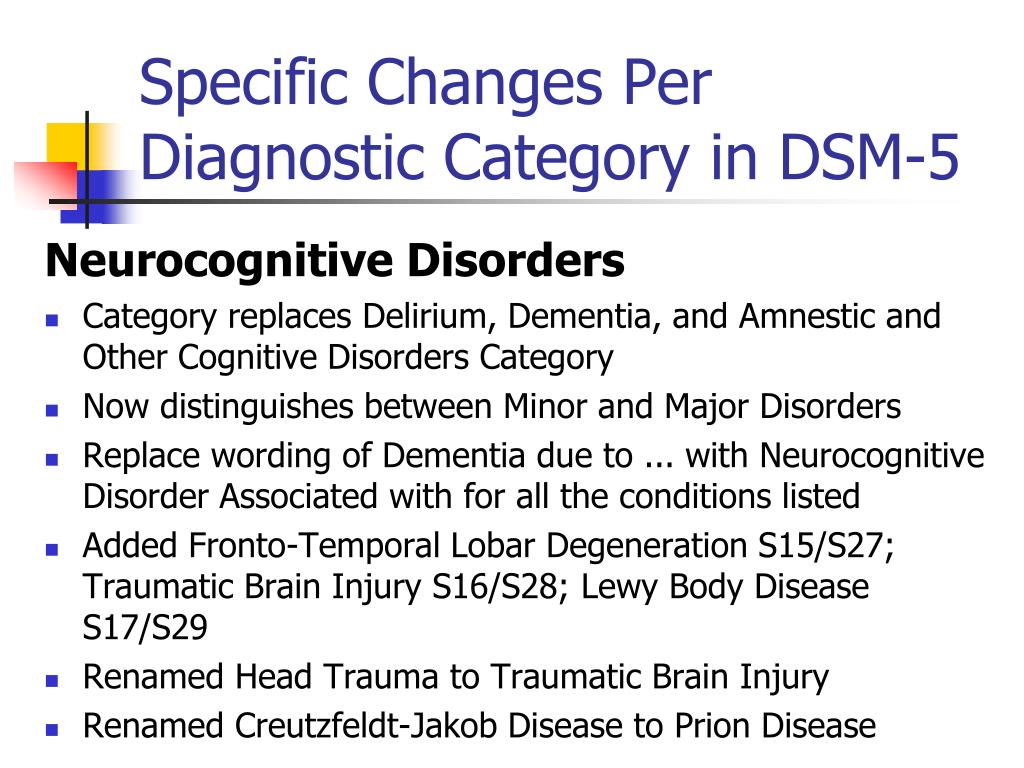

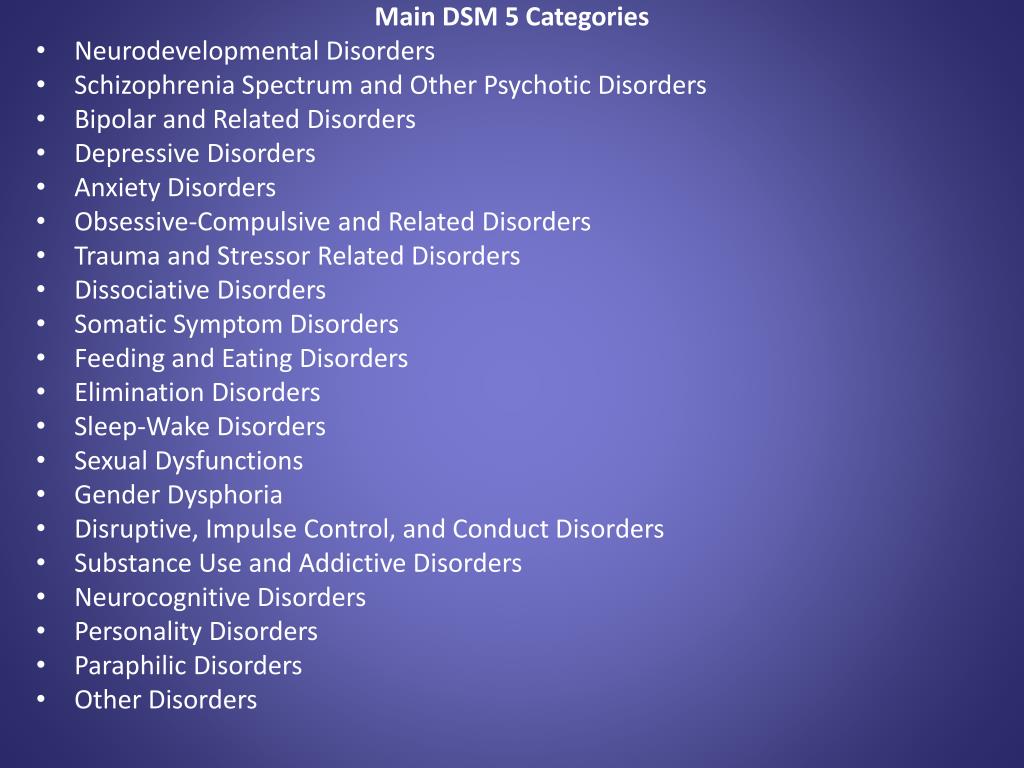

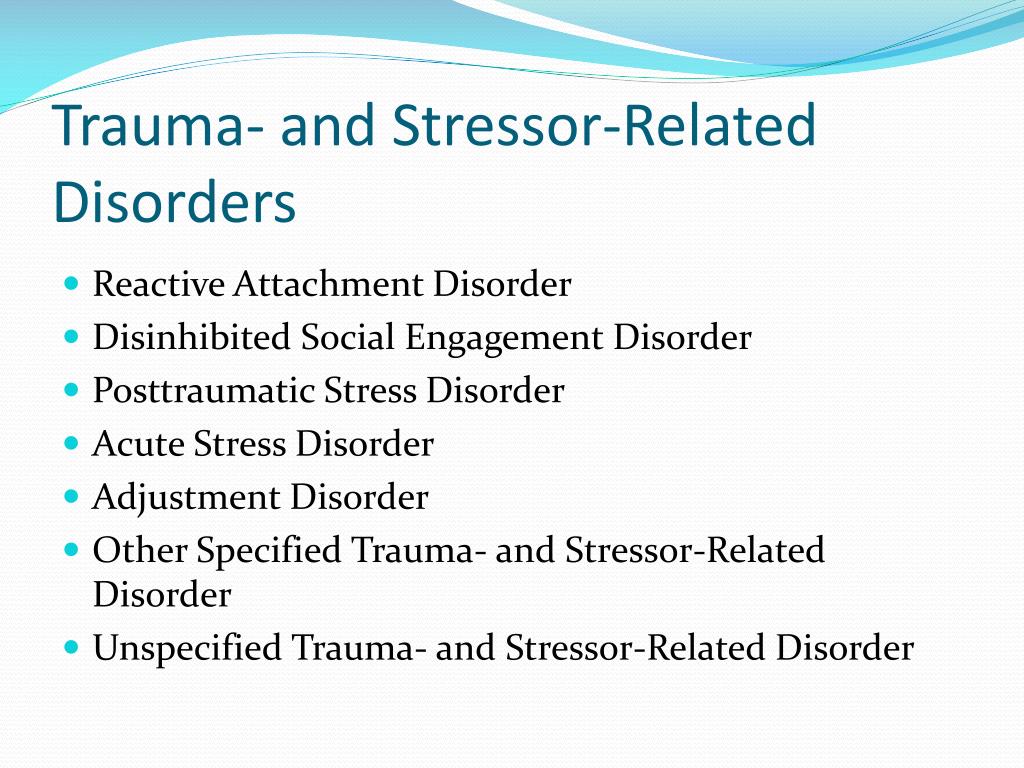

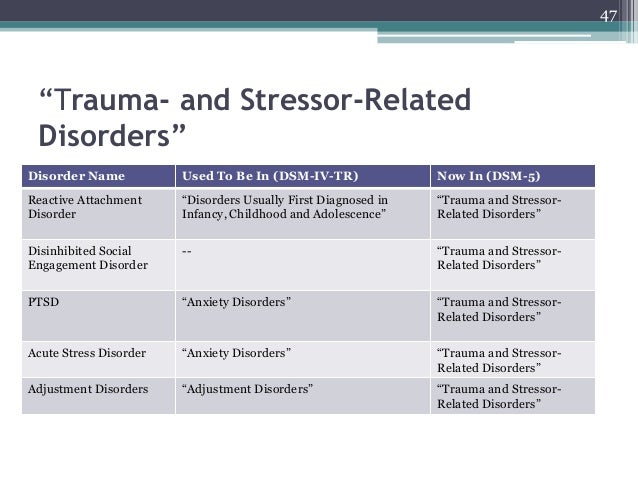

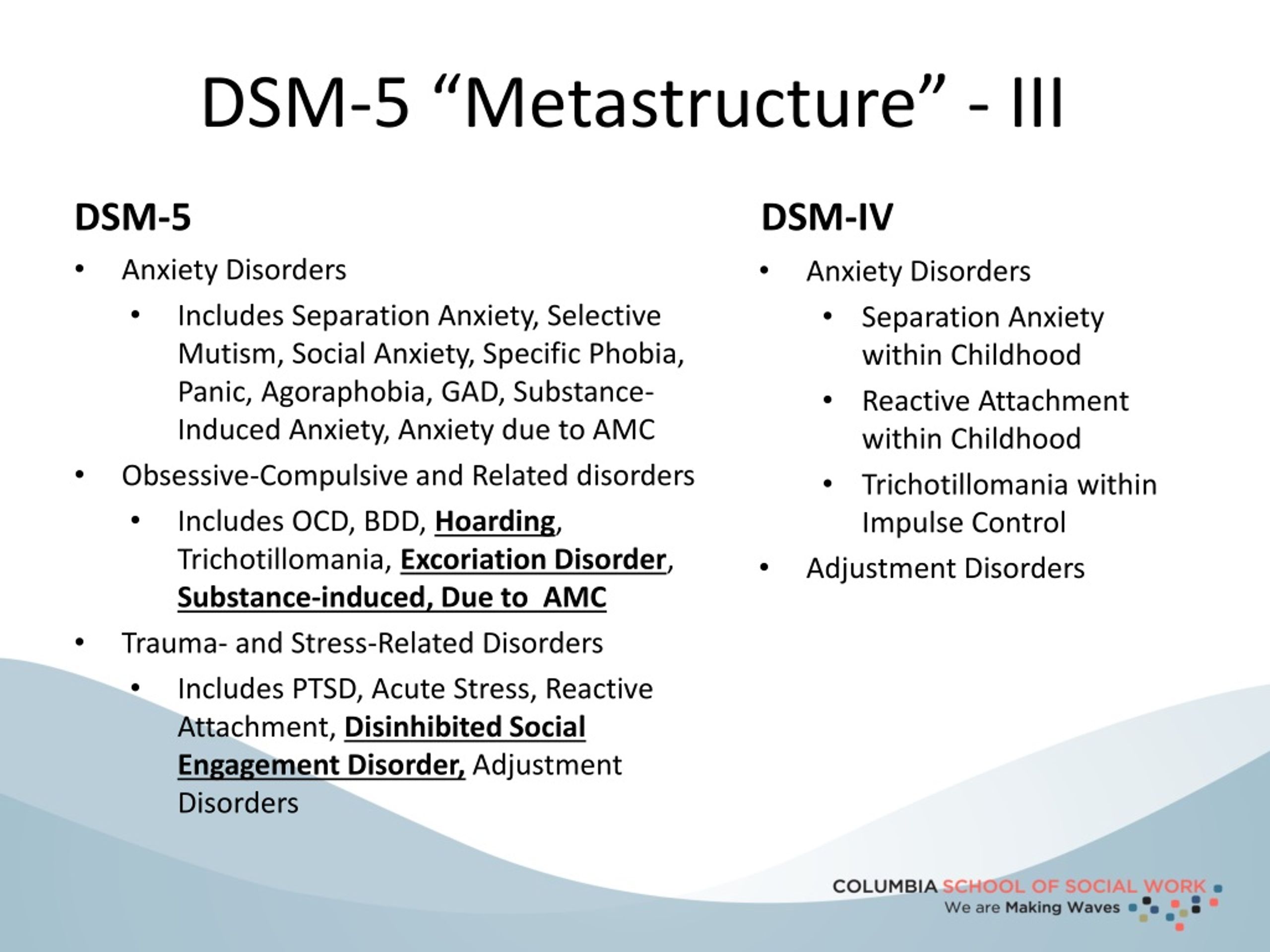

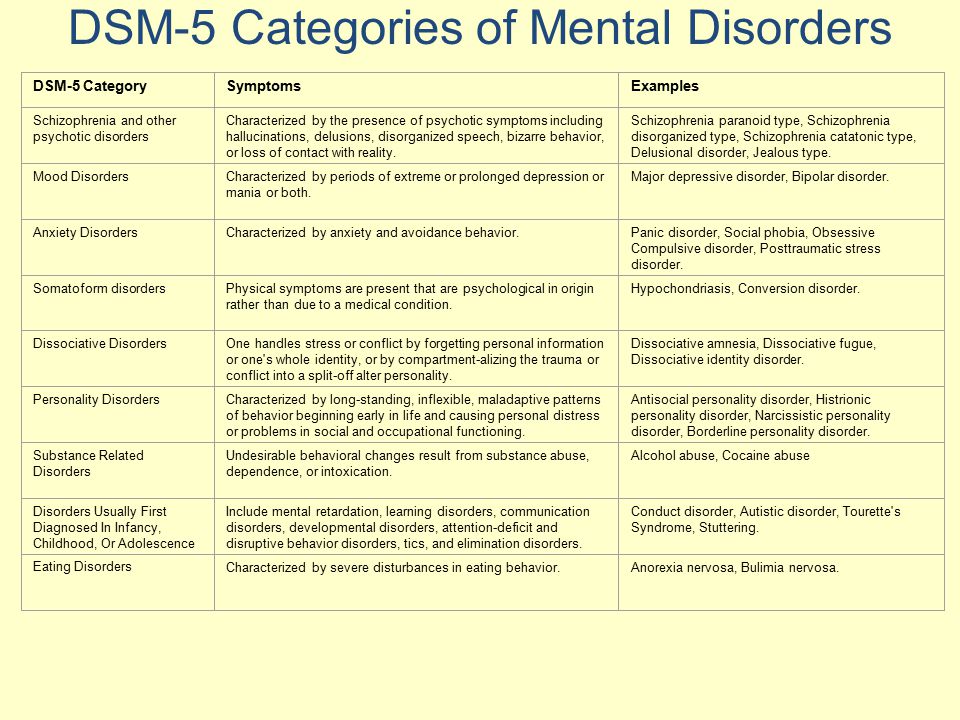

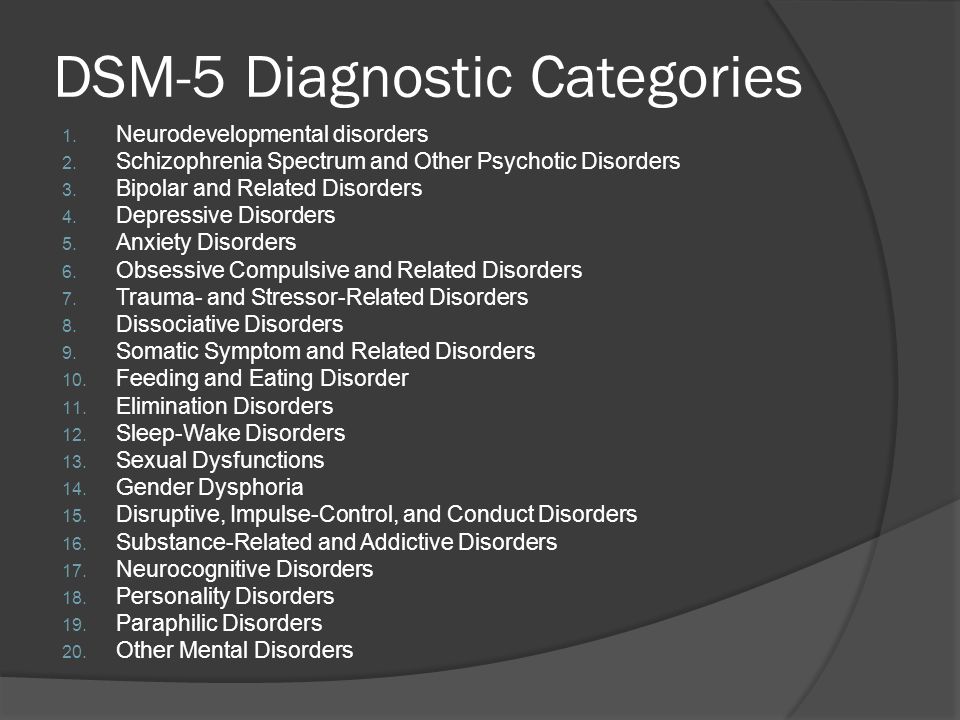

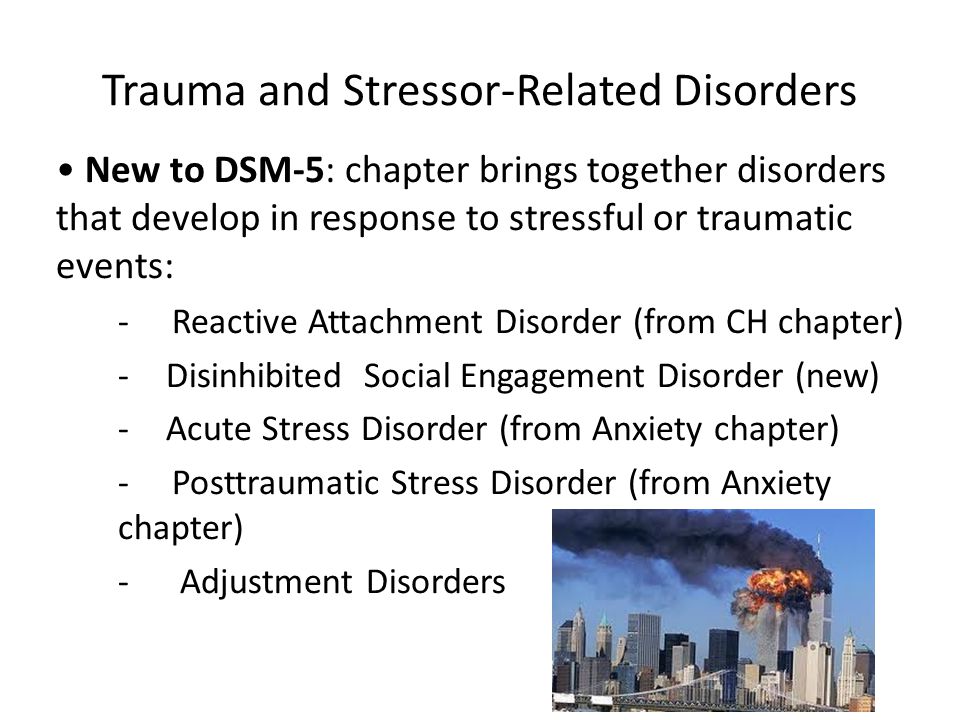

Perhaps the most substantial conceptual change in the DSM-5 for PTSD was the removal of the disorder from the anxiety disorders category. Considerable research has demonstrated that PTSD entails multiple emotions (e.g., guilt, shame, anger) outside of the fear/anxiety spectrum [13,14], thus providing evidence inconsistent with inclusion of PTSD with the anxiety disorders. In the DSM-5, PTSD was placed in a new diagnostic category named “Trauma and Stressor-related Disorders” indicating a common focus of the disorders in it as relating to adverse events. This diagnostic category is distinctive among psychiatric disorders in the requirement of exposure to a stressful event as a precondition. Other disorders included in this diagnostic category are adjustment disorder, reactive attachment disorder, disinhibited social engagement disorder, and acute stress disorder. This is the only diagnostic category in the DSM-5 that is not grouped conceptually by the types of symptoms characteristic of the disorders in it.

This diagnostic category is distinctive among psychiatric disorders in the requirement of exposure to a stressful event as a precondition. Other disorders included in this diagnostic category are adjustment disorder, reactive attachment disorder, disinhibited social engagement disorder, and acute stress disorder. This is the only diagnostic category in the DSM-5 that is not grouped conceptually by the types of symptoms characteristic of the disorders in it.

PTSD begins with criterion A, which requires exposure to a traumatic event. Criterion A is not only the most fundamental part of the nosology of PTSD, but also its most controversial aspect [12]. Some trauma experts criticized criterion A in the DSM-IV as too inclusive [5,6,15] and warned that this change had the potential to promote “conceptual bracket creep” [16] or “criterion creep” [17]. Some authors questioned the value of criterion A altogether [8,18,19], even suggesting that it should be abolished [8]. Criterion A was retained in the DSM-5, but it was modified to restrict its inclusiveness.

Criterion A was retained in the DSM-5, but it was modified to restrict its inclusiveness.

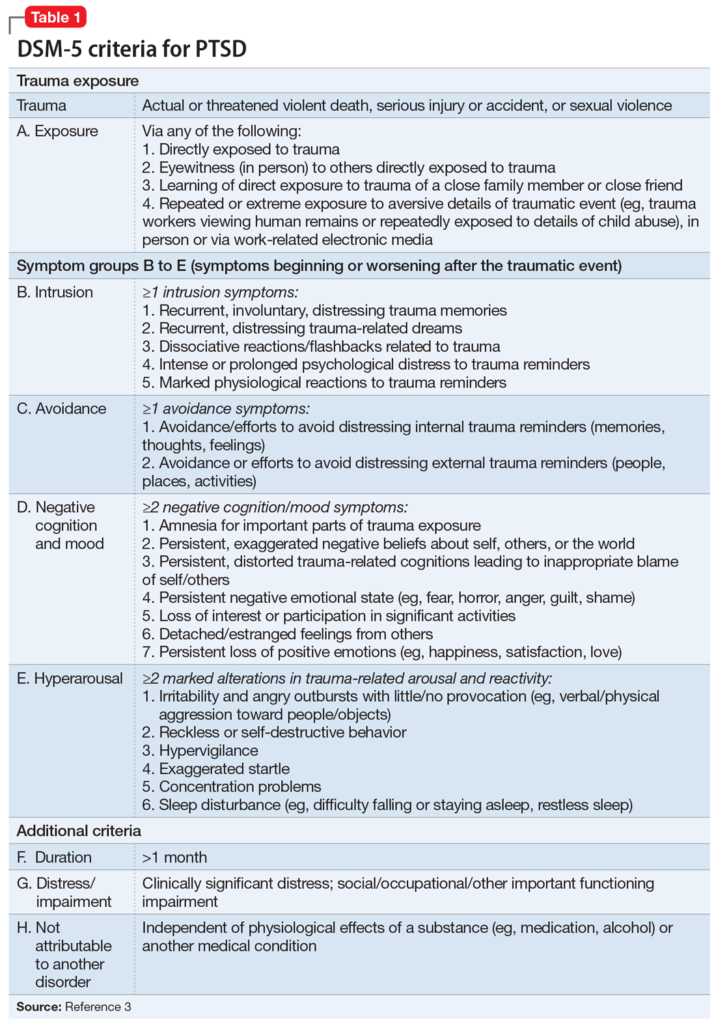

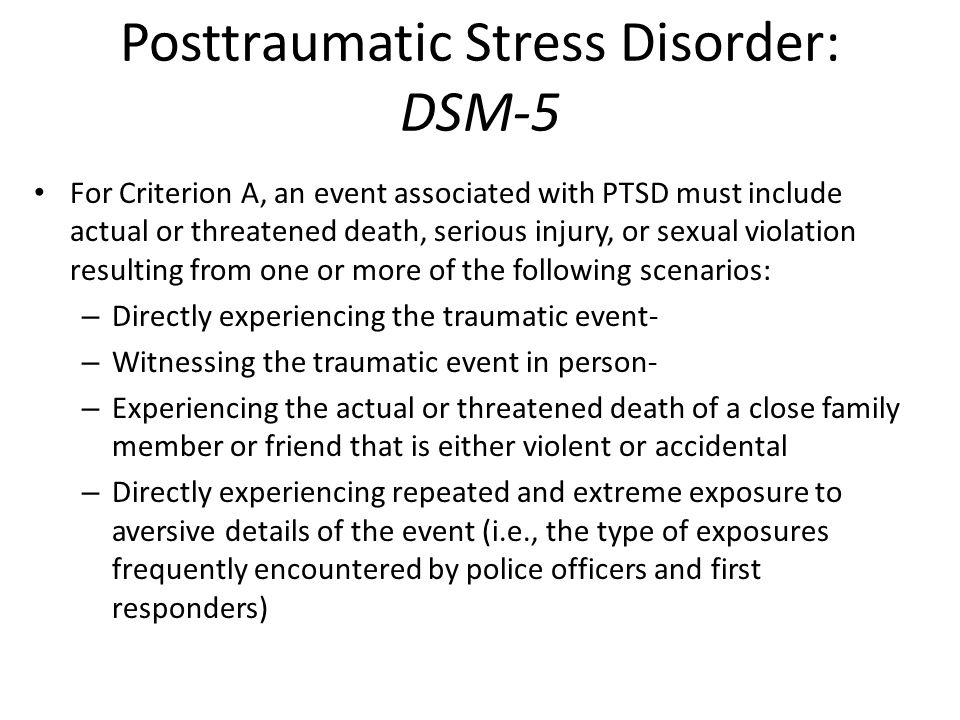

Not all stressful events involve trauma. The DSM-5 definition of trauma requires “actual or threatened death, serious injury, or sexual violence” [10] (p. 271). Stressful events not involving an immediate threat to life or physical injury such as psychosocial stressors [4] (e.g., divorce or job loss) are not considered trauma in this definition.

The DSM-5 has clarified and narrowed the types of events that qualify as “traumatic”. The ambiguous DSM-IV/-TR term “threat to physical integrity” [3] (p. 427) was removed from the definition of trauma in the DSM-5. Medically based trauma is now limited to sudden catastrophe such as waking during surgery or anaphylactic shock. Non-immediate, non-catastrophic life-threatening illness, such as terminal cancer, no longer qualifies as trauma, regardless of how stressful or severe it is. Medical incidents involving natural causes, such as a heart attack, no longer qualify (with the stated exception of life-threatening hemorrhage in one’s child, as described in the text accompanying the criteria). This seemingly minor revision of the definition of medically based trauma appears to have had a substantial influence on PTSD findings. A DSM-IV/DSM-5 comparison study conducted by Kilpatrick and colleagues [20] using highly structured self-report inventories demonstrated that 60% of PTSD cases that met DSM-IV but not proposed DSM-5 PTSD criteria were excluded from the DSM-5 because the traumatic events involved only nonviolent deaths.

This seemingly minor revision of the definition of medically based trauma appears to have had a substantial influence on PTSD findings. A DSM-IV/DSM-5 comparison study conducted by Kilpatrick and colleagues [20] using highly structured self-report inventories demonstrated that 60% of PTSD cases that met DSM-IV but not proposed DSM-5 PTSD criteria were excluded from the DSM-5 because the traumatic events involved only nonviolent deaths.

In addition to requiring the occurrence of a traumatic event, criterion A stipulates that the individual must have had a qualifying exposure to the trauma [2]. In other words, trauma is necessary, but it is not sufficient for consideration of PTSD without a qualifying exposure to that trauma. The DSM-IV/-TR provided three qualifying exposure types: direct personal exposure, witnessing of trauma to others, and indirect exposure through trauma experience of a family member or other close associate. Although some critics had argued for removal of the third (indirect) type of exposure [5,6], the DSM-5 retained all three types of exposure from the DSM-IV/-TR, now listed in the DSM-5 as A1–A3. A fourth exposure type (A4) has been added: repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of a traumatic event, which applies to workers who encounter the consequences of traumatic events as part of their professional responsibilities (e.g., military mortuary workers, forensic child abuse investigators).

A fourth exposure type (A4) has been added: repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of a traumatic event, which applies to workers who encounter the consequences of traumatic events as part of their professional responsibilities (e.g., military mortuary workers, forensic child abuse investigators).

DSM-IV/-TR used the phrase “experienced, witnessed, or was confronted with” [3] (p. 467) to refer to the three types of exposures that are now listed and explicitly defined respectively as A1–A3 in the DSM-5. The ambiguous DSM-IV/-TR term “confronted with”, in apparent reference to indirect exposure through close associates, has been completely removed from the definition of exposure to trauma in the DSM-5. The DSM-IV/-TR did not specify whether witnessed exposures had to be in person, or whether media reports could constitute a witnessed exposure. The DSM-5 has now clearly required the witnessing of trauma to others to be “in person” [10] (p. 271). Exposure through media is further narrowed in the DSM-5 by specifying that “criterion A4 does not apply to exposure through electronic media, television, movies or pictures unless it is work-related” [10] (p. 271). These specific changes to the criteria defining trauma and qualifying exposures to it have important potential ramifications for the assessment and estimation of PTSD prevalence in real-life settings. For example, using the unspecified DSM-IV/-TR definition of witnessed trauma exposure, research studies counted media reports as trauma exposures, permitting nearly anyone living in the United States of America to be trauma-exposed in the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks [5]. The nationwide incidence of “probable PTSD” related to the disaster was thus reported as 4% of the population [21], constituting an estimated total burden of 11 million cases [2]. The consequences of imprecise definitions of trauma and exposure to it are particularly extensive when large populations with non-qualifying trauma exposures are considered trauma-exposed for the purposes of measuring symptoms.

271). Exposure through media is further narrowed in the DSM-5 by specifying that “criterion A4 does not apply to exposure through electronic media, television, movies or pictures unless it is work-related” [10] (p. 271). These specific changes to the criteria defining trauma and qualifying exposures to it have important potential ramifications for the assessment and estimation of PTSD prevalence in real-life settings. For example, using the unspecified DSM-IV/-TR definition of witnessed trauma exposure, research studies counted media reports as trauma exposures, permitting nearly anyone living in the United States of America to be trauma-exposed in the 11 September 2001 terrorist attacks [5]. The nationwide incidence of “probable PTSD” related to the disaster was thus reported as 4% of the population [21], constituting an estimated total burden of 11 million cases [2]. The consequences of imprecise definitions of trauma and exposure to it are particularly extensive when large populations with non-qualifying trauma exposures are considered trauma-exposed for the purposes of measuring symptoms. Careful application of DSM-5 criteria in the future can avert substantial inaccuracies in the estimation of PTSD prevalence.

Careful application of DSM-5 criteria in the future can avert substantial inaccuracies in the estimation of PTSD prevalence.

The DSM-5 removed the subjective personal response of “intense fear, horror, or helplessness” that had been added to criterion A in the DSM-IV. The requirement of a subjective response as part of the trauma criterion created a serious conceptual error by conflating the subjective experience of trauma with objective exposure to the traumatic event [4]. The personal response to trauma exposure, including posttraumatic symptoms, needs to be separated from the definition of trauma exposure for conceptual clarity [2]. In agreement with North and colleagues, McNally [5] (p. 598) recommended the elimination of criterion A2, arguing: “In the language of behaviorism, it confounds the response with the stimulus. In the language of medicine, it confounds the host with the pathogen”. The decision to remove criterion A2 from the DSM-5, however, was instead based on two specific research findings: (1) the requirement of a subjective response would exclude individuals who did not endorse fear, helplessness, or horror during the traumatic event, yet met the rest of the diagnostic criteria for PTSD [22,23], especially military personnel [2,24]; (2) the subjective response does not add predictive ability to the objective definition [22,25].

Exposure to trauma is the foundation for the rest of the criteria that comprise the diagnosis of PTSD [4,12,16,26]. Breslau et al. [27] emphasized that the link between PTSD symptoms and exposure to a traumatic event is what makes the diagnosis of PTSD a distinct disorder. They posed the question, “Without exposure to trauma, what is posttraumatic about the ensuing syndrome?” [27] (p. 927). North et al. [4] whimsically added that without exposure to trauma, a syndrome following a nontraumatic stressor might more appropriately be named “poststressor stress disorder” and one associated with no identified stressor called “nonstressor stress disorder”.

PTSD symptoms are conditionally linked to trauma exposure. Almost all other disorders in the DSM criteria are defined based on their characteristic symptoms, and thus the conditional nature of PTSD creates complexity not encountered in other disorders. According to the current diagnostic criteria, assessment of PTSD symptoms is appropriate only if criterion A is met, i. e., the individual has had a qualifying exposure to a requisite trauma. Without this trauma exposure, psychiatric symptoms reported by an individual would not qualify as PTSD symptoms. Each symptom must be anchored to the traumatic event through a temporal and/or contextual relationship [4]. The DSM-5 stipulates that to qualify, the symptoms must begin (symptom criteria B and C) or worsen (symptom criteria D and E) after the traumatic event. Even though the symptoms must be linked to a traumatic event, this linking does not imply causality or etiology. Hence, the diagnostic criteria for PTSD are actually descriptive and agnostic toward etiology and therefore consistent with the generally descriptive and agnostic approach to defining psychiatric disorders in the American diagnostic system [4].

e., the individual has had a qualifying exposure to a requisite trauma. Without this trauma exposure, psychiatric symptoms reported by an individual would not qualify as PTSD symptoms. Each symptom must be anchored to the traumatic event through a temporal and/or contextual relationship [4]. The DSM-5 stipulates that to qualify, the symptoms must begin (symptom criteria B and C) or worsen (symptom criteria D and E) after the traumatic event. Even though the symptoms must be linked to a traumatic event, this linking does not imply causality or etiology. Hence, the diagnostic criteria for PTSD are actually descriptive and agnostic toward etiology and therefore consistent with the generally descriptive and agnostic approach to defining psychiatric disorders in the American diagnostic system [4].

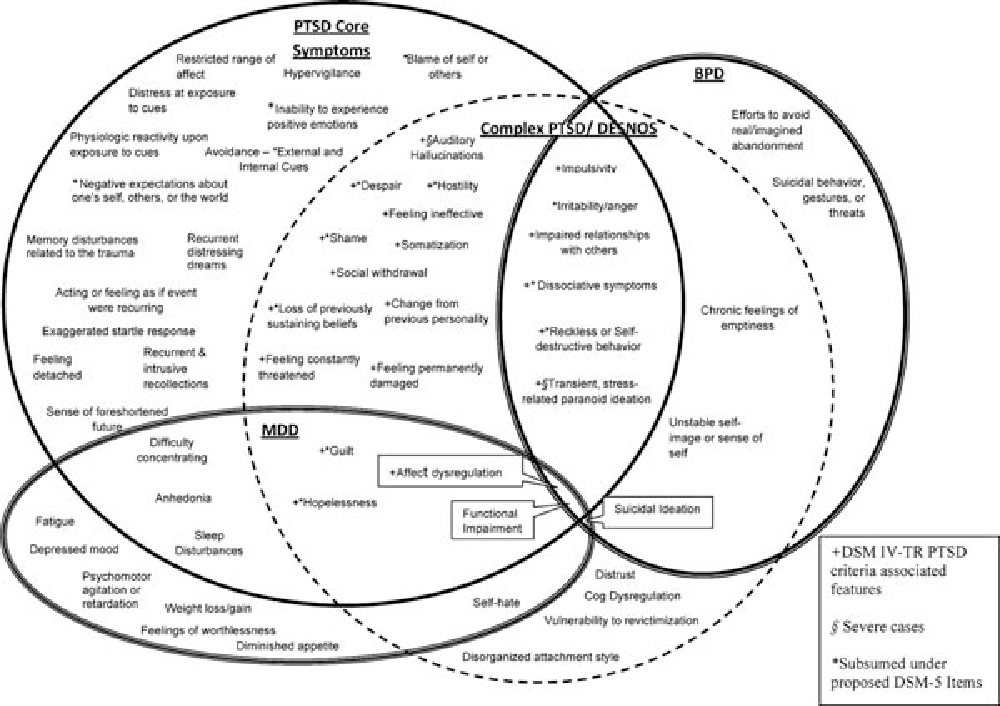

Revision of the PTSD symptom groups in the DSM-5 relied on guidance from factor analytic research; however, findings from factor analytic studies examining the latent structure of PTSD symptoms to determine the most parsimonious symptom groupings have been inconsistent [28]. Additional factor analytic research has demonstrated substantial overlap of PTSD symptoms with symptoms of other disorders (especially depressive and anxiety disorders), inviting criticism of the validity of PTSD as a distinct disorder [15]. This factor analytic research has been limited, however, by use of self-report scales not anchoring symptoms to the traumatic event as defined by the diagnostic criteria for PTSD [4]. Factor analytic studies using data collected from structured diagnostic interviews that correctly link the symptoms contextually and temporally to the trauma exposure are needed to address these unresolved problems in the conceptualization of PTSD symptom criteria.

Additional factor analytic research has demonstrated substantial overlap of PTSD symptoms with symptoms of other disorders (especially depressive and anxiety disorders), inviting criticism of the validity of PTSD as a distinct disorder [15]. This factor analytic research has been limited, however, by use of self-report scales not anchoring symptoms to the traumatic event as defined by the diagnostic criteria for PTSD [4]. Factor analytic studies using data collected from structured diagnostic interviews that correctly link the symptoms contextually and temporally to the trauma exposure are needed to address these unresolved problems in the conceptualization of PTSD symptom criteria.

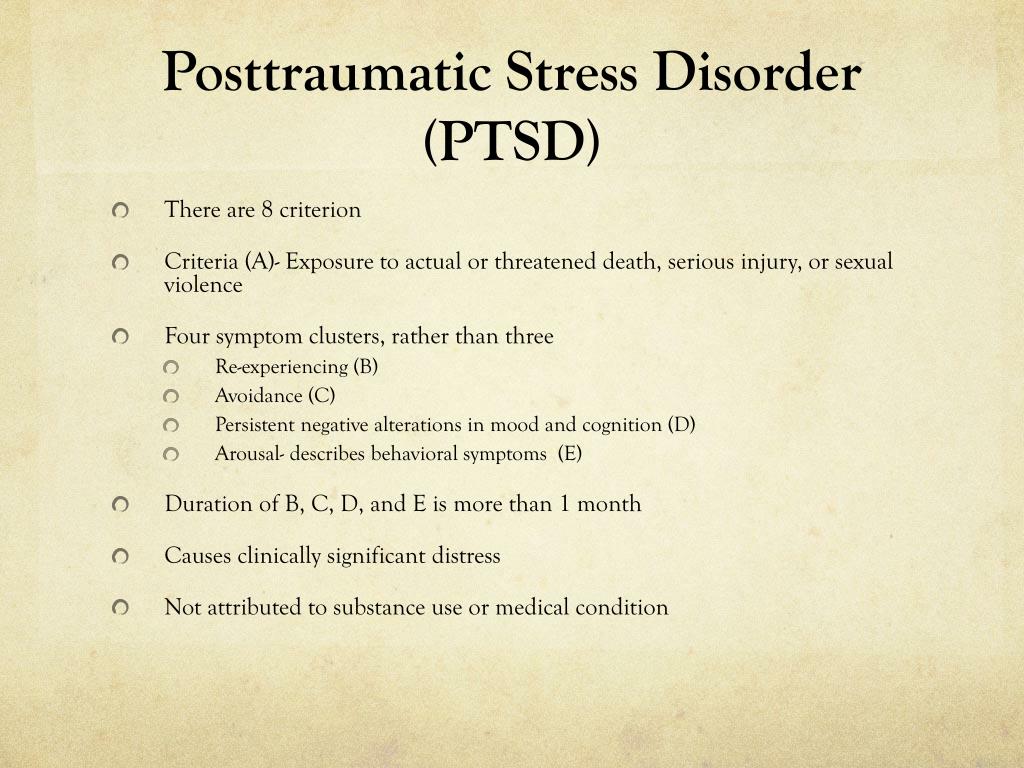

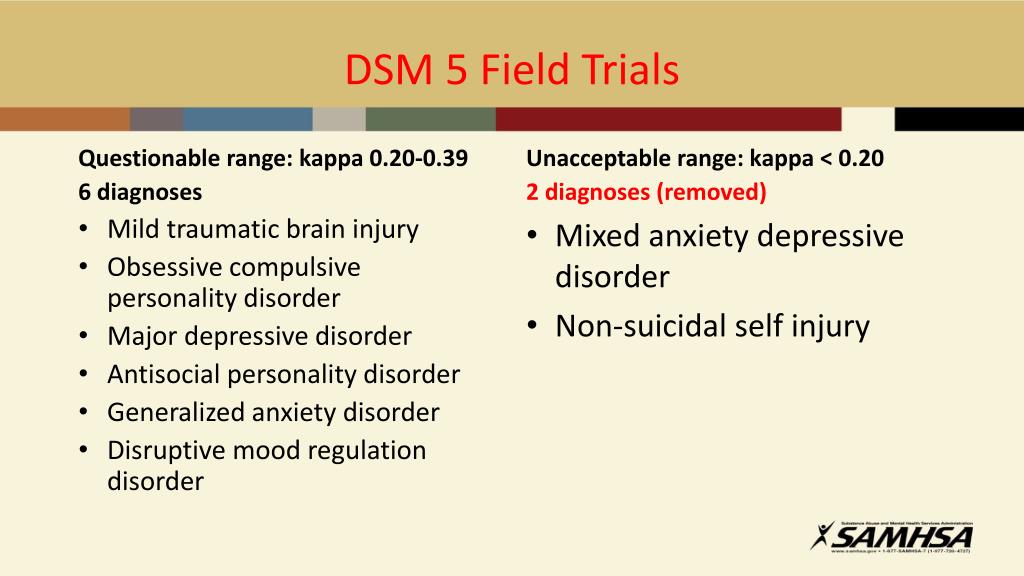

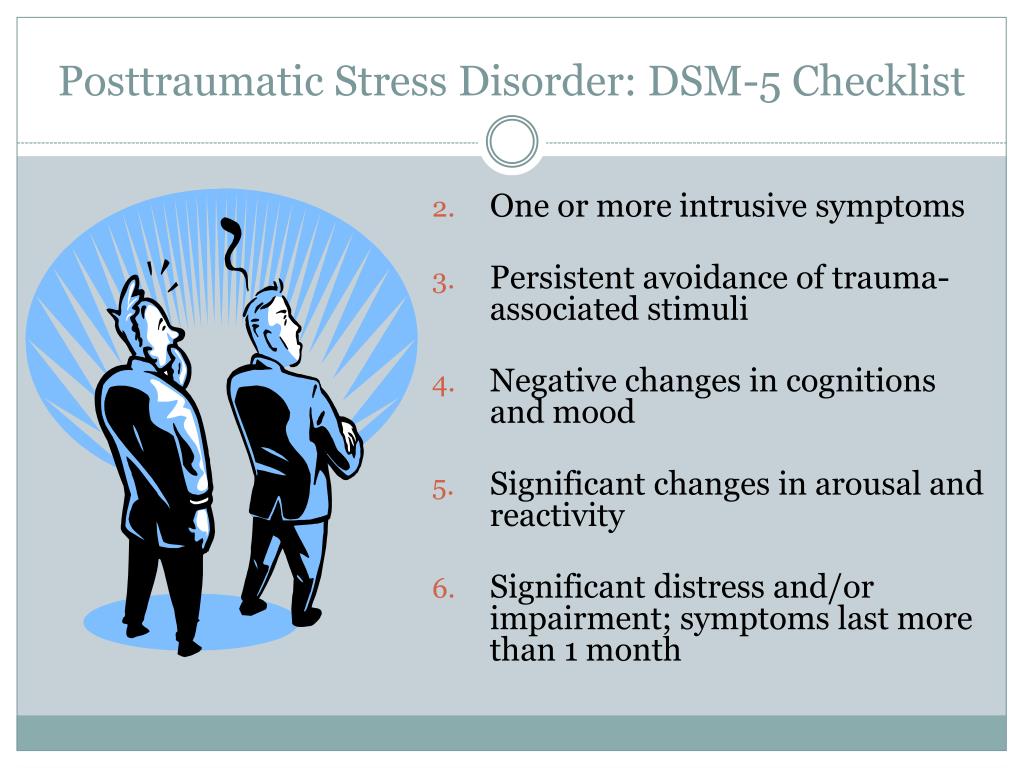

The DSM-5 increased the number of symptom groups from three to four and the number of symptoms from 17 to 20. The DSM-5 symptom groups are intrusion, avoidance, negative alterations in cognition and mood, and alterations in arousal and reactivity. To form the new group, DSM-5 separated the avoidance and numbing symptoms into different groups. The two avoidance items from the DSM-IV/-TR avoidance/numbing group (criterion C) now comprise the DSM-5 avoidance group (criterion C), and the numbing symptoms are now included with cognitive symptoms and mood symptoms in the negative cognition and mood group (criterion D). With this reorganization, at least one avoidance symptom is now required for an individual to meet diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5, in contrast to DSM-IV/-TR criteria which permitted a PTSD diagnosis even if no avoidance symptoms were endorsed.

The two avoidance items from the DSM-IV/-TR avoidance/numbing group (criterion C) now comprise the DSM-5 avoidance group (criterion C), and the numbing symptoms are now included with cognitive symptoms and mood symptoms in the negative cognition and mood group (criterion D). With this reorganization, at least one avoidance symptom is now required for an individual to meet diagnostic criteria in the DSM-5, in contrast to DSM-IV/-TR criteria which permitted a PTSD diagnosis even if no avoidance symptoms were endorsed.

Three new symptoms were added to the PTSD criteria in the DSM-5: persistent negative emotional state, persistent distorted cognitions about the cause or consequences of the trauma leading to blame of self or others, and reckless or self-destructive behavior. Reckless or self-destructive behavior was found to have low prevalence and poor factor loading in the DSM-5 field trials, and this symptom was predominantly endorsed by the subgroup reporting the most severe symptoms [12,29]. The finding that only a limited subset of people endorsing severe symptoms acknowledged reckless or self-destructive behavior suggests that this symptom represents more a characteristic of a high symptom-endorsing subgroup and less a feature of the disorder itself. Reckless or self-destructive behavior was added as a symptom to the DSM-5 criteria despite these research findings, because clinicians and researchers who observe it in the PTSD patient populations they work with believed it to represent a clinically important feature of the disorder [29]. Elsewhere it has been argued that inclusion of reckless/self-destructive behavior, persistent distorted cognitions, aggression toward others, and emphasis on dissociation have inserted cluster B personality features into PTSD, and that it may reflect selection biases based on observations of these features in specific subpopulations of PTSD, such as patients receiving psychiatric treatment [2]. Hoge and colleagues [30] criticized the added reckless/self-destructive behavior and negative emotional state symptoms as nonspecific to the psychopathology of PTSD and the persistent distorted cognitions symptom as over-pathologizing.

The finding that only a limited subset of people endorsing severe symptoms acknowledged reckless or self-destructive behavior suggests that this symptom represents more a characteristic of a high symptom-endorsing subgroup and less a feature of the disorder itself. Reckless or self-destructive behavior was added as a symptom to the DSM-5 criteria despite these research findings, because clinicians and researchers who observe it in the PTSD patient populations they work with believed it to represent a clinically important feature of the disorder [29]. Elsewhere it has been argued that inclusion of reckless/self-destructive behavior, persistent distorted cognitions, aggression toward others, and emphasis on dissociation have inserted cluster B personality features into PTSD, and that it may reflect selection biases based on observations of these features in specific subpopulations of PTSD, such as patients receiving psychiatric treatment [2]. Hoge and colleagues [30] criticized the added reckless/self-destructive behavior and negative emotional state symptoms as nonspecific to the psychopathology of PTSD and the persistent distorted cognitions symptom as over-pathologizing.

A number of DSM-IV-TR PTSD symptoms were revised in the DSM-5 [2,30]. Some of the revisions involved minor wording changes (e.g., adding the word “involuntary” to “intrusive distressing recollections of the event”), and others were more foundational (e.g., “sense of a foreshortened future” reformulated as “persistent and exaggerated negative beliefs or expectations about oneself, others, or the world”; “restricted range of affect” changed to “persistent inability to experience positive emotions”). A study comparing DSM-IV/-TR and DSM-5 symptom checklists for PTSD indicated that the changes to PTSD symptoms reflected in the checklists may have substantially altered the identification of PTSD cases [31].

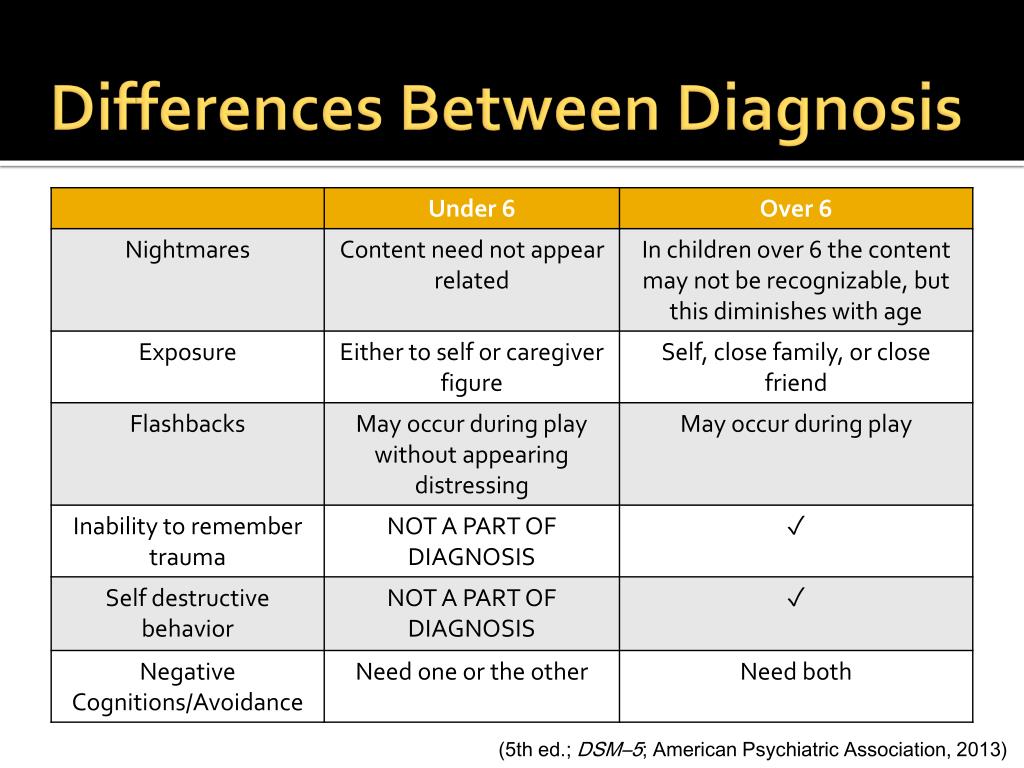

A new set of PTSD criteria was added for children six years of age or younger to reflect their levels of development. The criteria for younger children do not have the “repeated or extreme exposure to aversive details of the traumatic event” exposure type, have only three symptom groups consisting of a total of 16 symptoms, have different symptoms grouped together compared to the adult symptom criteria, and indirect trauma exposure through a close associate is limited to a parent or care-giving figure. Additionally, intrusive memories in younger children do not have to appear distressing (as in play re-enactment) and nightmares do not have to be contextually based on the traumatic event.

Additionally, intrusive memories in younger children do not have to appear distressing (as in play re-enactment) and nightmares do not have to be contextually based on the traumatic event.

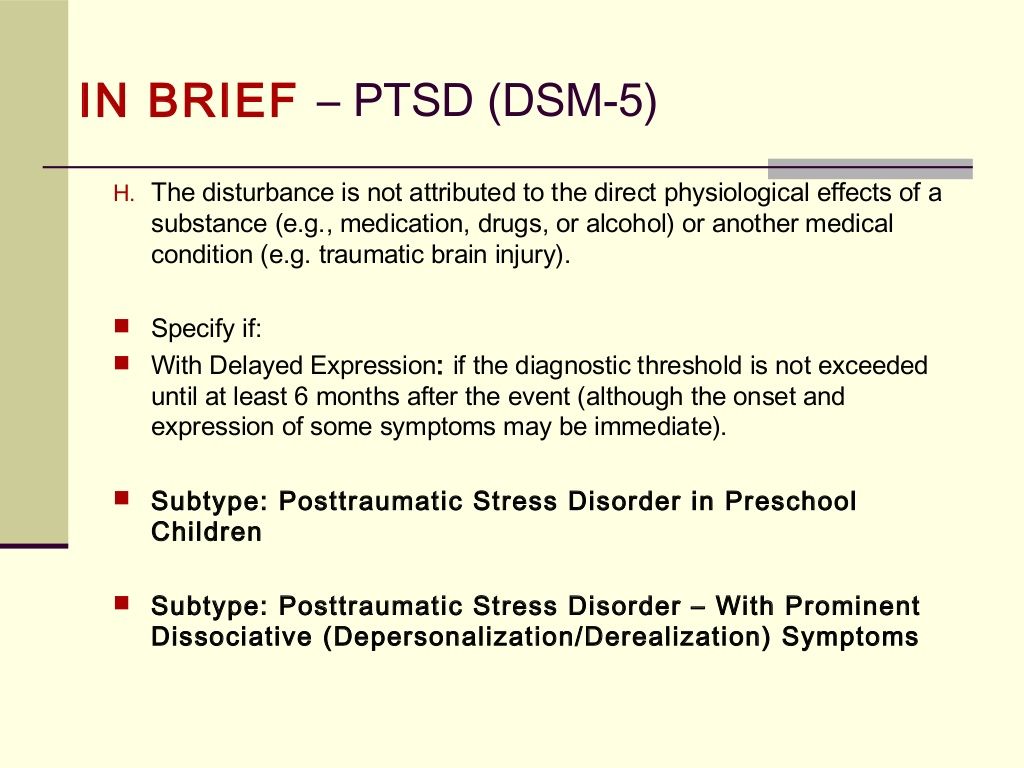

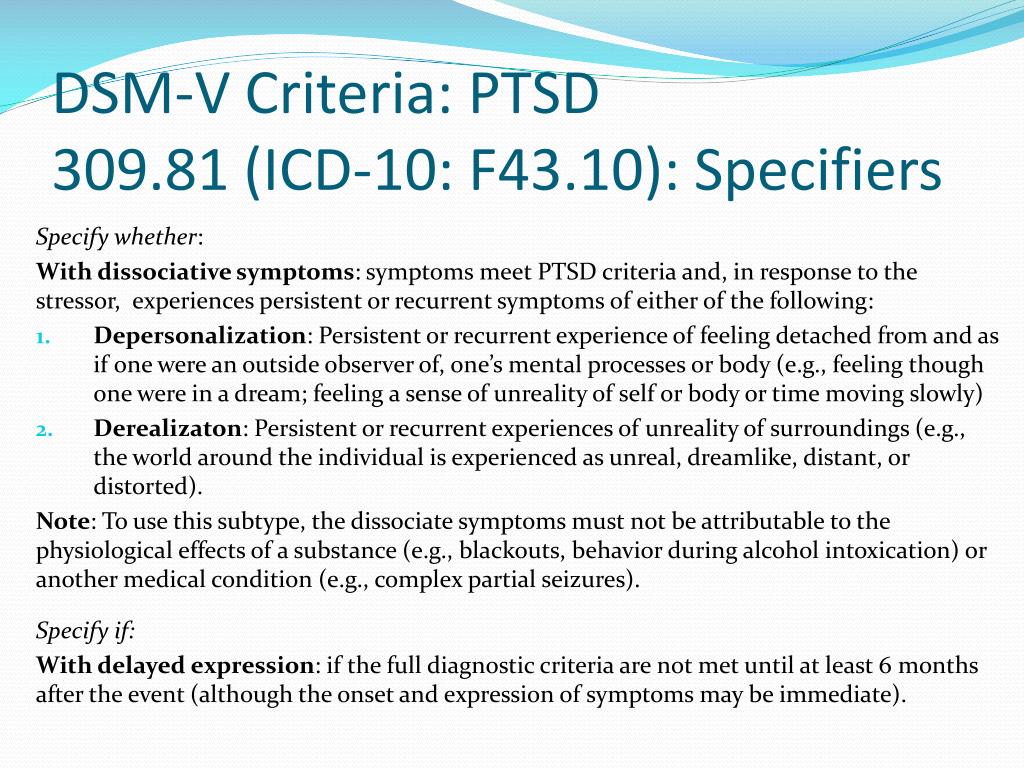

The acute and chronic PTSD specifiers were eliminated in the DSM-5, and the concept of delayed-onset PTSD was replaced with “delayed expression” defined as “the full diagnostic criteria are not met until at least 6 months after the event (although the onset and expression of some symptoms may be immediate)” [10] (p. 272). This is a diagnostic threshold definition of onset, using the point at which full diagnostic criteria are first met or last met as the point of onset or remission, respectively. Studies using repeated self-report symptom measures have used this method of determining onset and remission. Prior versions of DSM criteria have defined onset and remission of disorders as the point at which symptoms begin or end (i.e., a symptom-based definition of onset/remission), and structured diagnostic interviews have historically used this method of determining onset and remission [32]. The replacement of the previous PTSD onset criteria with the new delayed expression of onset definition in the DSM-5 has effectively substituted a diagnostic threshold-based definition (which is found to yield a higher prevalence) for the historic symptom-based definition of onset [32]. This shift is destined to make it impossible to compare the onset of PTSD across studies using the new definition with historical estimates from previous research.

The replacement of the previous PTSD onset criteria with the new delayed expression of onset definition in the DSM-5 has effectively substituted a diagnostic threshold-based definition (which is found to yield a higher prevalence) for the historic symptom-based definition of onset [32]. This shift is destined to make it impossible to compare the onset of PTSD across studies using the new definition with historical estimates from previous research.

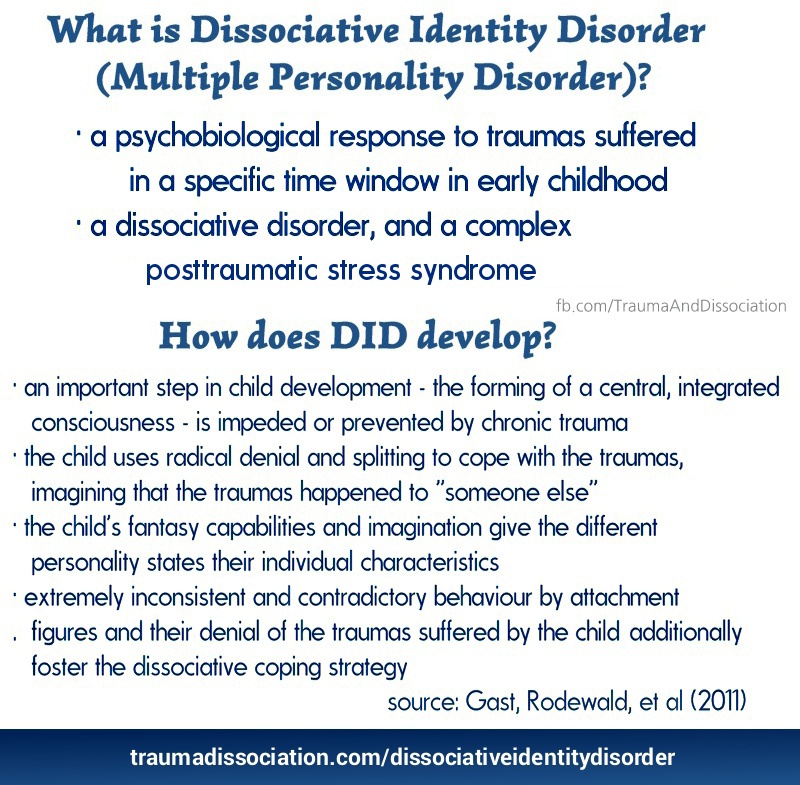

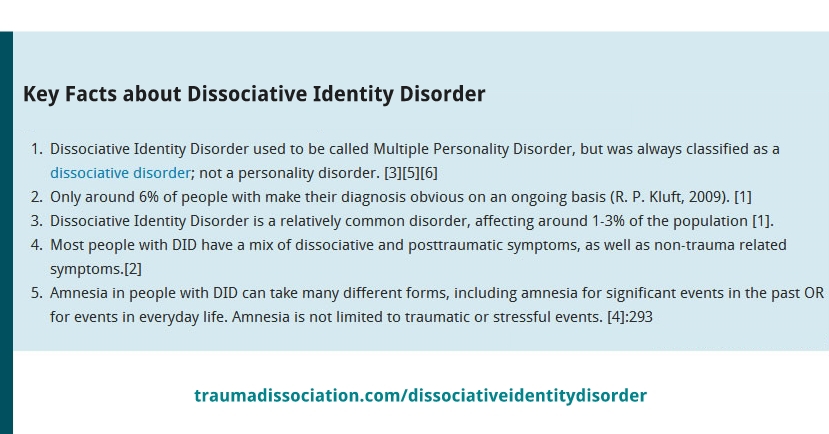

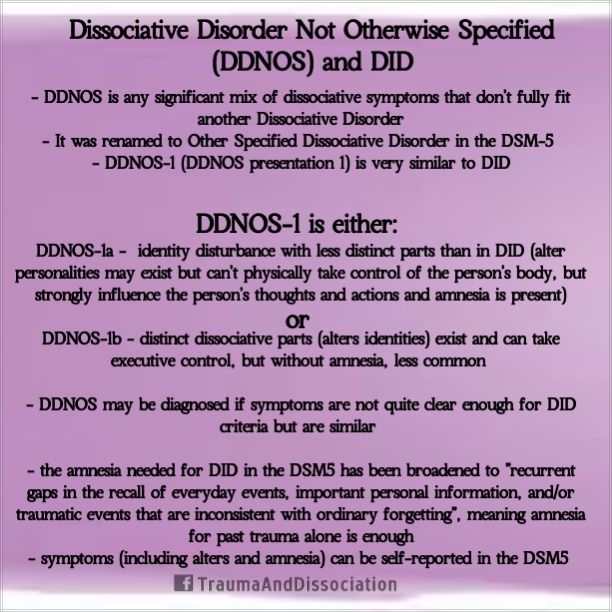

The DSM-5 introduced a new dissociative features specifier to note the presence of associated persistent or recurrent depersonalization or derealization symptoms. This new feature of the disorder is a reflection of the focus of the DSM-5 Trauma, PTSD, and Dissociative Disorders Sub-Work Group of the Anxiety Disorders Work Group committee that proposed the new PTSD criteria.

The diagnostic criteria for PTSD were substantially modified in the DSM-5, despite the revision process being described as “very conservative” by the work group [12]. The new changes in criterion A provide more conceptual clarity. Trauma exposure is objectively defined, and the subjective responses to trauma exposure (criterion A2) have been removed from criterion A, separating them from the trauma definition and confining them to the symptom criteria. This separation of the subjective response to trauma from the objective definition of trauma is an important advancement in the nosology of this conditionally-based disorder. The new criteria for trauma and exposure to it further limit the types of events that qualify as trauma for consideration of this disorder and more carefully define qualifying exposures to trauma.

The new changes in criterion A provide more conceptual clarity. Trauma exposure is objectively defined, and the subjective responses to trauma exposure (criterion A2) have been removed from criterion A, separating them from the trauma definition and confining them to the symptom criteria. This separation of the subjective response to trauma from the objective definition of trauma is an important advancement in the nosology of this conditionally-based disorder. The new criteria for trauma and exposure to it further limit the types of events that qualify as trauma for consideration of this disorder and more carefully define qualifying exposures to trauma.

Development of diagnostic criteria is an iterative process [4,33]. Additional research will be needed to validate this revision of the PTSD criteria, including study of descriptive characteristics, differential diagnosis, biological markers, and genetic factors [34]. Because the conditional definition of PTSD introduces complexity to its definition, it is paramount to study the criteria for PTSD with careful adherence to established criteria to permit testing of the criteria that are in use to inform future work.

Anushka Pai, Alina M. Suris and Carol S. North conceptualized this article and contributed to writing the manuscript together.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 3rd ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC, USA: 1980. [Google Scholar]

2. North C.S., Surís A.M., Smith R.P., King R.V. The evolution of PTSD criteria across editions of DSM. Ann. Clin. Psychiatry. 2016;28:197–208. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

3. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Washington, DC, USA: 1994. [Google Scholar]

4. North C.S., Suris A.M., Davis M., Smith R.P. Toward Validation of the Diagnosis of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Am. J. Psychiatry. 2009;166:34–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08050644. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

5. McNally R.J. Can we fix PTSD in DSM-V? Depress. Anxiety. 2009;26:597–600. doi: 10.1002/da.20586. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

Anxiety. 2009;26:597–600. doi: 10.1002/da.20586. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

6. Spitzer R.L., First M.B., Wakefield J.C. Saving PTSD from itself in DSM-V. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007;21:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.09.006. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

7. McHugh P.R., Treisman G. PTSD: A problematic diagnostic category. J. Anxiety Disord. 2007;21:211–222. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2006.09.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

8. Brewin C.R., Lanius R.A., Novac A., Schnyder U., Galea S. Reformulating PTSD for DSM-V: Life after Criterion A. J. Trauma. Stress. 2009;22:366–373. doi: 10.1002/jts.20443. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

9. Summerfield D. The invention of post-traumatic stress disorder and the social usefulness of a psychiatric category. BMJ. 2001;322:95–98. doi: 10.1136/bmj.322.7278.95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

10. American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Arlington, VA, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; Arlington, VA, USA: 2013. [Google Scholar]

11. Regier D.A., Kuhl E.A., Kupfer D.J. The DSM-5: Classification and criteria changes. World Psychiatry. 2013;12:92–98. doi: 10.1002/wps.20050. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

12. Friedman M.J. Finalizing PTSD in DSM-5: Getting Here From There and Where to Go Next: Finalizing PTSD in DSM-5. J. Trauma. Stress. 2013;26:548–556. doi: 10.1002/jts.21840. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

13. Friedman M.J., Resick P.A., Bryant R.A., Strain J., Horowitz M., Spiegel D. Classification of trauma and stressor-related disorders in DSM-5. Depress. Anxiety. 2011;28:737–749. doi: 10.1002/da.20845. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

14. Resick P.A., Miller M.W. Posttraumatic stress disorder: Anxiety or traumatic stress disorder? J. Trauma. Stress. 2009;22:384–390. doi: 10.1002/jts.20437. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

15. Rosen G.M., Spitzer R. L., McHugh P.R. Problems with the post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis and its future in DSM V. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2008;192:3–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.043083. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

L., McHugh P.R. Problems with the post-traumatic stress disorder diagnosis and its future in DSM V. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2008;192:3–4. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.043083. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

16. McNally R.J. Progress and Controversy in the Study of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2003;54:229–252. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145112. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

17. Rosen G.M. Traumatic events, criterion creep, and the creation of pretraumatic stress disorder. Sci. Rev. Ment. Health Pract. 2004;3:39–42. [Google Scholar]

18. Maier T. Post-traumatic stress disorder revisited: Deconstructing the A-criterion. Med. Hypotheses. 2006;66:103–106. doi: 10.1016/j.mehy.2005.07.028. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

19. Kraemer B., Wittmann L., Jenewein J., Maier T., Schnyder U. Is the Stressor Criterion Dispensable? Psychopathology. 2009;42:333–336. doi: 10.1159/000232976. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

20. Kilpatrick D. G., Resnick H.S., Milanak M.E., Miller M.W., Keyes K.M., Friedman M.J. National Estimates of Exposure to Traumatic Events and PTSD Prevalence Using DSM-IV and DSM-5 Criteria: DSM-5 PTSD Prevalence. J. Trauma. Stress. 2013;26:537–547. doi: 10.1002/jts.21848. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

G., Resnick H.S., Milanak M.E., Miller M.W., Keyes K.M., Friedman M.J. National Estimates of Exposure to Traumatic Events and PTSD Prevalence Using DSM-IV and DSM-5 Criteria: DSM-5 PTSD Prevalence. J. Trauma. Stress. 2013;26:537–547. doi: 10.1002/jts.21848. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

21. Schlenger W.E., Caddell J.M., Ebert L., Jordan B.K., Rourke K.M., Wilson D., Thalji L., Dennis J.M., Fairbank J.A., Kulka R.A. Psychological reactions to terrorist attacks: Findings from the National Study of Americans’ Reactions to September 11. JAMA. 2002;288:581–588. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.5.581. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

22. Breslau N., Kessler R.C. The stressor criterion in DSM-IV posttraumatic stress disorder: An empirical investigation. Biol. Psychiatry. 2001;50:699–704. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3223(01)01167-2. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

23. Karam E.G., Andrews G., Bromet E., Petukhova M., Ruscio A.M., Salamoun M. , Sampson N., Stein D.J., Alonso J., Andrade L.H., et al. The Role of Criterion A2 in the DSM-IV Diagnosis of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68:465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.032. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Sampson N., Stein D.J., Alonso J., Andrade L.H., et al. The Role of Criterion A2 in the DSM-IV Diagnosis of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. Biol. Psychiatry. 2010;68:465–473. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.04.032. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

24. Adler A.B., Wright K.M., Bliese P.D., Eckford R., Hoge C.W. A2 diagnostic criterion for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J. Trauma. Stress. 2008;21:301–308. doi: 10.1002/jts.20336. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

25. Bedard-Gilligan M., Zoellner L.A. The utility of the A1 and A2 criteria in the diagnosis of PTSD. Behav. Res. Ther. 2008;46:1062–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2008.06.009. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

26. Weathers F.W., Keane T.M. The criterion a problem revisited: Controversies and challenges in defining and measuring psychological trauma. J. Trauma. Stress. 2007;20:107–121. doi: 10.1002/jts.20210. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

27. Breslau N. , Chase G.A., Anthony J.C. The uniqueness of the DSM definition of post-traumatic stress disorder: Implications for research. Psychol. Med. 2002;32:573–576. doi: 10.1017/S0033291701004998. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Chase G.A., Anthony J.C. The uniqueness of the DSM definition of post-traumatic stress disorder: Implications for research. Psychol. Med. 2002;32:573–576. doi: 10.1017/S0033291701004998. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

28. Armour C., Műllerová J., Elhai J.D. A systematic literature review of PTSD’s latent structure in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-IV to DSM-5. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2016;44:60–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.12.003. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

29. Miller M.W., Wolf E.J., Kilpatrick D., Resnick H., Marx B.P., Holowka D.W., Keane T.M., Rosen R.C., Friedman M.J. The prevalence and latent structure of proposed DSM-5 posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in U.S. national and veteran samples. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy. 2013;5:501–512. doi: 10.1037/a0029730. [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

30. Hoge C.W., Yehuda R., Castro C.A., McFarlane A.C., Vermetten E., Jetly R., Koenen K.C., Greenberg N., Shalev A.Y. , Rauch S.A.M., et al. Unintended Consequences of Changing the Definition of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in DSM-5: Critique and Call for Action. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:750. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0647. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

, Rauch S.A.M., et al. Unintended Consequences of Changing the Definition of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in DSM-5: Critique and Call for Action. JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73:750. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.0647. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

31. Hoge C.W., Riviere L.A., Wilk J.E., Herrell R.K., Weathers F.W. The prevalence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in US combat soldiers: A head-to-head comparison of DSM-5 versus DSM-IV-TR symptom criteria with the PTSD checklist. Lancet Psychiatry. 2014;1:269–277. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70235-4. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

32. North C.S., Oliver J. Analysis of the longitudinal course of PTSD in 716 survivors of 10 disasters. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2013;48:1189–1197. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0639-x. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

33. Guze S.B. Nature of psychiatric illness: Why psychiatry is a branch of medicine. Compr. Psychiatry. 1978;19:295–307. doi: 10.1016/0010-440X(78)90012-3. [PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

[PubMed] [CrossRef] [Google Scholar]

34. North C.S., Yutzy S.H. Psychiatric Diagnosis. University Press; New York, NY, USA: 2010. PTSD; pp. 129–166. [Google Scholar]

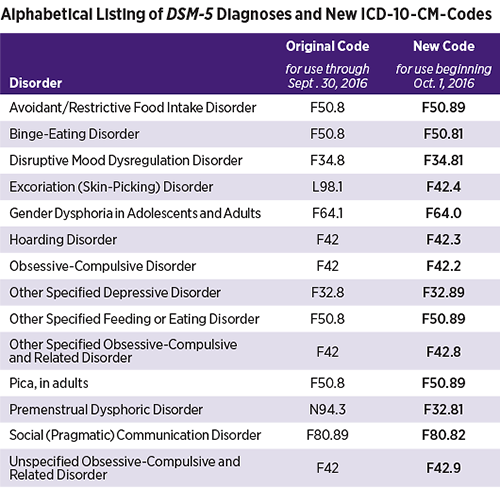

Trauma and Stressor-related Disorders with DSM-5 & ICD 10 codes

Trauma and Stressor-related Disorders with DSM-5 & ICD 10 codesThe newest guide to diagnosing mental disorders is the DSM-5, released in 2013.[4] It lists the following Trauma and Stressor-related disorders:

- Disinhibited social engagement disorder DSM-5 code 313.89, ICD-10 code F49.12

- Reactive attachment disorder DSM-5 code 313.89, ICD-10 code F49.1

- Acute stress disorder DSM-5 code 308.3, ICD-10 code F43.0

- Adjustment Disorders DSM-5 code 309 ICD-10 code F43.2

- Posttraumatic stress disorder DSM-5 code 309.81, ICD-10 code F43.10

- Other Specified Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorder DSM-5 code 309.89, ICD-10 code F43.8

- Unspecified Trauma and Stressor-Related Disorder DSM-5 code 309.

9, ICD-10 code F43.9

9, ICD-10 code F43.9

Complex Post-traumatic Stress Disorder is likely to be included in the International Classification of Diseases diagnostic manual, which is currently being revised. [2]

All these disorders result from a known cause of either traumatic or stressful situations, or events recognized explicitly in the diagnostic criteria.[1]:169

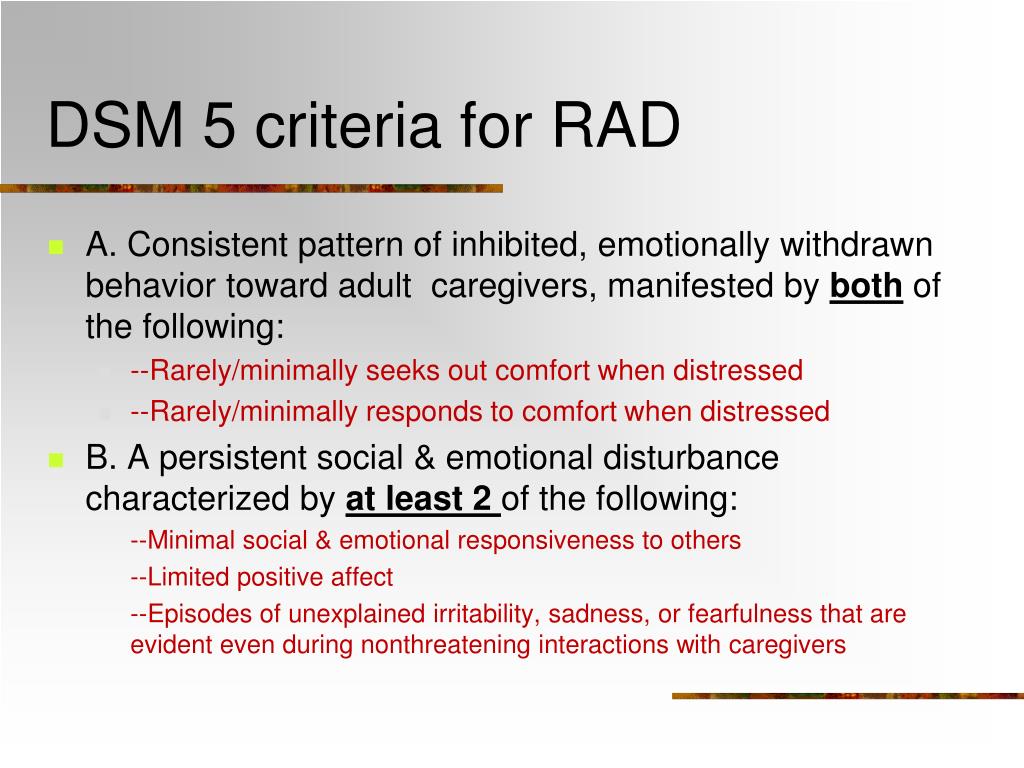

Reactive attachment disorder and Disinhibited social engagement disorder both result from social neglect during childhood (a lack of appropriate care-giving), and onset is during childhood. Posttraumatic stress disorder and acute stress disorder were moved out of the Anxiety disorders category because research showed that their presentation can vary and a wide range of different reactions may occur; they are not necessarily primarily fear- or anxiety-based reactions.[1]:170

Trauma and/or abuse are the only recognized causes of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Complex Posttraumatic Stress Disorder. However, these disorders require the trauma to be a major trauma, sometimes referred to as a 'Type I trauma'. More minor traumatic experiences, sometimes called 'Type II trauma', (e.g., emotional abuse and physical neglect), are not considered severe enough to meet the present diagnostic criteria. [3] However, the role of multiple and more minor traumatic experiences is now being increasing recognized.

However, these disorders require the trauma to be a major trauma, sometimes referred to as a 'Type I trauma'. More minor traumatic experiences, sometimes called 'Type II trauma', (e.g., emotional abuse and physical neglect), are not considered severe enough to meet the present diagnostic criteria. [3] However, the role of multiple and more minor traumatic experiences is now being increasing recognized.

See also Trauma and Abuse

See also Living with trauma

References

- Black, Donald W. (2014) (coauthors: Grant, Jon E.). DSM-5 Guidebook: The Essential Companion to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition. American Psychiatric Pub. ISBN 9781585624652.

- World Health Organization. (2014) International Classification of Diseases (ICD). Retrieved November 16, 2014, from http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/revision/en/

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5.

(5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. ISBN 0890425558.

(5th ed.). Washington, D.C.: American Psychiatric Association. ISBN 0890425558.

Trauma and Stressor-related Disorders. Traumadissociation.com. Retrieved from .

This information can be copied or modified for any purpose, including commercially, provided a link back is included. License: CC BY-SA 4.0

© Copyright TraumaDissociation.com – Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

DSM-5 PTSD - psyxotrauma - LiveJournal

DSM-V Diagnostic Criteria for PTSD (309.81)

DSM Fifth Revision classifies PTSD as a psychiatric disorder associated with stress and trauma

DSM-V for adults, teens, and children over 6 years of age.

Criterion A Exposure to mortal danger or threat of death, being or threatened with serious injury, sexual violence or its threat, which may manifest itself in one of the following ways:

1. Direct experience of the traumatic event.

Direct experience of the traumatic event.

2. Personal testimony of an event involving others.

3. News of an event that happened to close family members or close friends. In cases of imminent or possible death of a family member or friend, the event must be sudden or unexpected.

4. Repeated or excessive exposure to some aspect of the traumatic event that causes a strong negative emotional reaction (for example, those who, due to circumstances, were the first to be at the scene of a death and are busy collecting the bodies and remains of the dead; police officers who repeatedly witnessed the immediate consequences of violence over children.)

Note : Paragraph A(4) excludes indirect exposure through mass media, television, films, static images in the case, only in cases when it is connected with the performance of professional duties.

Criteria B Presence of one or more intrusion symptoms associated with the traumatic event that appeared after the traumatic event:

1. Repetitive, involuntary, and intrusive memories of a traumatic event that cause distress.

Repetitive, involuntary, and intrusive memories of a traumatic event that cause distress.

2. Recurring distressing dreams whose content and/or affect is related to the traumatic event.

3. Dissociative reactions (eg flashback effects) in which the individual feels or behaves as if a traumatic past event is happening in the present. (Such reactions can be located on a continuum of intensity, the extreme pole of which corresponds to states with a complete loss of contact with the surrounding reality).

4. Severe or prolonged psychological distress when exposed to external or internal stimuli that symbolize or resemble some aspect of the traumatic event.

5. Physiological reactivity to external or internal stimuli that symbolize or resemble some aspect of the traumatic event.

Criterion C Sustained avoidance of trauma-related stimuli after completion of the traumatic event (at least one of the following):

1. Avoiding or trying to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings that are directly or closely related to the traumatic event.

Avoiding or trying to avoid distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings that are directly or closely related to the traumatic event.

2. Avoiding or attempting to avoid external reminders (eg, certain people, places, objects, situations, durations, conversations) that result in distressing memories, thoughts, or feelings related to or closely associated with the traumatic event.

Criterion D The deterioration of cognitive functioning and mood associated with the traumatic event, which began after the end of the traumatic event (at least two of the 9,000): )

1. Inability to recall important aspects of the traumatic event (mainly due to dissociative amnesia and not related to factors such as traumatic brain injury, alcohol or drug use).

2. Persistent and exaggeratedly distorted beliefs or expectations of a negative nature about oneself or the world around them (For example, "I am bad", "No one can be trusted", "The world is dangerous", "I have lost my soul forever", ""My nervous

3. Persistent and distorted beliefs about the cause or consequences of the traumatic event, on which self-blame or blaming others is based.

Persistent and distorted beliefs about the cause or consequences of the traumatic event, on which self-blame or blaming others is based.

4. .

5. Marked significant decrease in interest or involvement in activities that were previously significant.

6. Feeling detached and alienated from other people.

7. Sustainable inability to experience positive emotions (for example, inability to experience happiness, satisfaction or feelings of love and affection)

Criterion E 9000 A marked and significant change in physiological excitability and reactivity that began or worsened after the end of the traumatic event (at least two of the following):

usually expressed in verbal or physical aggression against people or objects.

2. Self-harming behavior, reckless risk-taking behavior.

3. Increased alertness.

4. Exaggerated starting response

5. Difficulty falling or staying asleep.

6. Difficulty concentrating.

Criterion F Displexation duration (symptoms described in criteria B, C, D and F more than 1 month 9000 9000 900 900 900 900 0013

PTSD: what it is, symptoms, treatment

Psychological trauma can sit inside us for years and decades, undermining strength and exacerbating pain from time to time. A practicing psychologist talks about the nature of post-traumatic stress disorder and explains what might help to cope with it.

Arkady Volkov, psychotherapist, specialist of the service for the selection of psychologists Alter

Advertising on RBC www.adv.rbc.ru

What is PTSD

Each person has many mechanisms and resources at his disposal to help him cope with difficult events, cope with difficulties, endure grief and loss, overcome disappointments and tragedies. Nevertheless, sometimes we are faced with an event that, for one reason or another, we cannot cope with: it does not fit into our personal experience at all and turns out to be an insurmountable shock. Such events, usually associated with a real or perceived risk to life and health, are usually called traumas, and they can cause post-traumatic stress disorder - a mental disorder as a result of encountering a traumatic situation.

Such events, usually associated with a real or perceived risk to life and health, are usually called traumas, and they can cause post-traumatic stress disorder - a mental disorder as a result of encountering a traumatic situation.

Studies show that almost 4% of people suffer from PTSD at least once during their lives. At the same time, statistics in different countries vary significantly: in China, 0.3% of respondents faced the problem, in the Netherlands — 7.4%, in Canada — 9.2% [1], [2].

PTSD symptoms

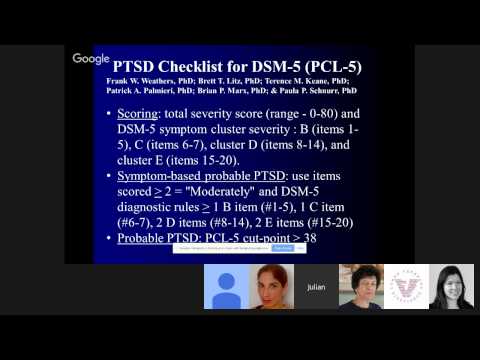

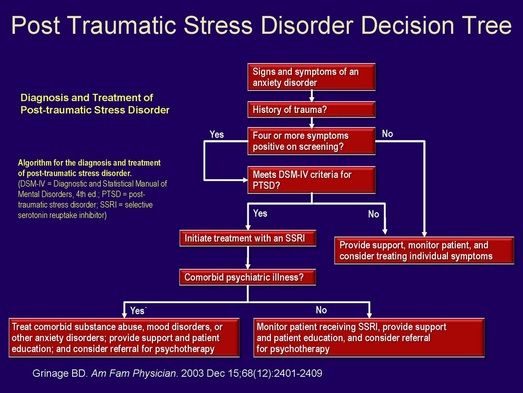

Currently, the two main medical diagnostic guidelines (DSM-5, the American Psychiatric Association's guidelines, and ICD-11, the World Health Organization's classification) state the following criteria to conclude that a person is suffering from PTSD:

- Encountered in a life or limb threatening situation. At the same time, PTSD can develop in a situation where a person has become a victim of such an event, and if he was a witness to it, or if a similar event happened to his loved ones.

This criterion also applies to professionals who, by the nature of their work, are faced with the consequences of traumatic events: doctors, firefighters, crisis psychologists, and so on.

This criterion also applies to professionals who, by the nature of their work, are faced with the consequences of traumatic events: doctors, firefighters, crisis psychologists, and so on.

- Presence of at least one of the symptoms of involuntary intrusive and disturbing memories of the event, nightmares, flashbacks, distressing experiences, or physical reaction in situations that are reminiscent of the event.

- Avoidance of memories and thoughts about the event or anything that might remind of it.

- Disturbances in thinking and emotional state due to the experienced event: inability to remember important aspects of what happened, negative thoughts and beliefs about oneself and the world around, blaming oneself or others that the traumatic event occurred, lowered mood and negative emotions, decreased interest in the world around , feelings of isolation and alienation, reduced ability to experience positive emotions.

- Changes such as irritability and outbursts of anger, aggressive and dangerous behavior to self or others, heightened alertness, startle response to minor stimuli, trouble concentrating and sleeping.

To be diagnosed, the listed symptoms must last more than one month and cause significant distress or social difficulties.

© shutterstock

It is important to note that PTSD is often accompanied by other disorders, primarily depressive ones.

Diagnosis of PTSD, like any other mental disorder, can only be diagnosed by a qualified specialist, but yes to the following questions may be a reason to seek advice and get help (or just be more attentive to yourself or a loved one).

- Have you experienced or witnessed any traumatic event during your life (such as an accident, fire, extreme disaster, physical attack on you or your loved ones)?

During the last month:

- Have you returned to this event in your thoughts (not wanting it) or dreams?

- Did you make an effort not to think about this event and avoid being reminded of it?

- Were you more tense than usual?

- Have you ever been frightened for minor reasons?

- Did you feel alienated from your usual activities and loved ones?

- Did you feel guilty or blame yourself or others for the event?

Causes and risk factors

There is still no definite answer to the question of what exactly causes PTSD. But research has led to some important assumptions.

But research has led to some important assumptions.

At the physiological level, the development of PTSD can be triggered by:

Increased levels of stress hormones

In case of danger, our body produces stress hormones, such as adrenaline, in order to switch into an active mode and somehow escape from the threat (this reaction is often called "fight or flight"). PTSD victims continue to produce large amounts of stress hormones even when the danger is no longer around. This can cause hyperarousal and emotional changes, and can also cause long-term negative health effects, including migraines, pain, and an increased risk of heart, lung, and digestive problems.

Changes in brain function

Trauma-induced stress can damage the hippocampus, the part of the brain involved in emotion and memory.

Hippocampal disorders can interfere with the proper processing of memories and dreams, so the anxiety they cause does not decrease over time. Such changes may explain the increased levels of fear and anxiety, memory and recall problems suffered by PTSD victims.

Such changes may explain the increased levels of fear and anxiety, memory and recall problems suffered by PTSD victims.

© shutterstock

Factors that can increase susceptibility to PTSD:

- Previous traumatic experiences. The stress of a trauma can have a cumulative effect, and a new traumatic experience can exacerbate the negative effects of a previous trauma.

- Experience of violence. People with a history of physical, emotional or sexual abuse tend to be more susceptible to post-traumatic stress.

- PTSD or depression in loved ones.

- Substance use experience.

- Lack of skills to cope with traumatic situations.

- Lack of social support. Good social and family relationships help mitigate the effects of stress and trauma. Conversely, people who lack supportive relationships and environments tend to be more vulnerable to stress and therefore more at risk for PTSD. Being in a social environment that cultivates shame, guilt, stigma, or self-hatred also contributes to the development of post-traumatic stress disorder.

- High level of stress in everyday life.

Treatment of PTSD

Approaches to the treatment of PTSD can be divided into two groups: medication and psychotherapy. Often methods of both groups are used in different combinations.

There are currently no medications specifically designed for the treatment of PTSD, but there are many medications that work well for other conditions such as depression and anxiety disorders and have been shown to be effective in treating the symptoms of PTSD.

When it comes to psychotherapeutic methods, or “healing with a word”, several approaches demonstrate the greatest (and research-supported) effectiveness.

Cognitive Process Therapy

In this approach, the therapist invites the client to talk about the traumatic event and its aftermath and describe the experience in detail in a diary, which allows them to better see how the trauma is reflected in thoughts and find new ways to deal with it [3 ].

© shutterstock

EMDR - eye movement desensitization and processing

This approach is based on the notion that trauma disrupts the natural coping mechanisms inherent in each person and cannot be built into his experience and memory. The person is asked to focus on an external stimulus (eye movements from side to side directed by the therapist) and in parallel work through complex memories, thoughts and emotions associated with the trauma [4].

Body and creativity oriented approaches

Body Oriented Therapy aims to find resources through attention to bodily sensations, as well as gaining the opportunity to relive the traumatic experience from the position of an active actor, not a victim. Similar goals are set by approaches that use dance and participation in theatrical productions to gain the freedom and spontaneity that PTSD often deprives its victims of [5].

Living with PTSD

Trauma has a huge impact on many areas of our lives, but this does not mean that the problem cannot be solved, even if for one reason or another you do not have access to professional help.

Of particular difficulty in working with PTSD is the very painfulness and severity of the traumatic experience, which often makes it necessary to avoid any reminders of the trauma, excluding the possibility of talking about it, as well as the destructive consequences for the view of oneself and the world around. All this makes it extremely difficult to build close relationships, seek support and help.

What can help you cope with PTSD

The first and most important step is often the recognition of the traumatic experience, which opens up opportunities for conversation and subsequent rethinking. The devastating effect of trauma on the psyche is largely due to the fact that the traumatic event is completely knocked out of the normal course of our life, and it is extremely important to return, build it into our personal history.

Research demonstrates the high effectiveness of such a simple tool as writing about your experience: writing down your thoughts and memories of a traumatic event, trying to talk about the impact it had on your life, thinking about the future.

Since trauma affects the body in one way or another, physical exercise, yoga (or regular stretching), meditation, dancing, and even theater classes can be an important help in overcoming its consequences [6].

The support of relatives and friends plays a huge role. It's important to open yourself up and find someone you can talk to about what's bothering you.

However, overcoming PTSD on your own is not easy and can take a long time. Therefore, at the first opportunity, it is worth contacting a psychotherapist.

If your loved one has PTSD

If you notice symptoms of PTSD in a loved one, you can become a support for him and help him. At the same time, it is important to take into account that it can be extremely difficult for him to talk about the trauma and even return to it in his thoughts, so it is important to indicate your willingness to help and be there without exerting any pressure. Your very understanding and supportive presence, your willingness to share activities that bring joy and pleasure, a sense of stability and confidence can be beneficial.