Toddler bipolar symptoms

Pediatric Bipolar Disorder - CHADD

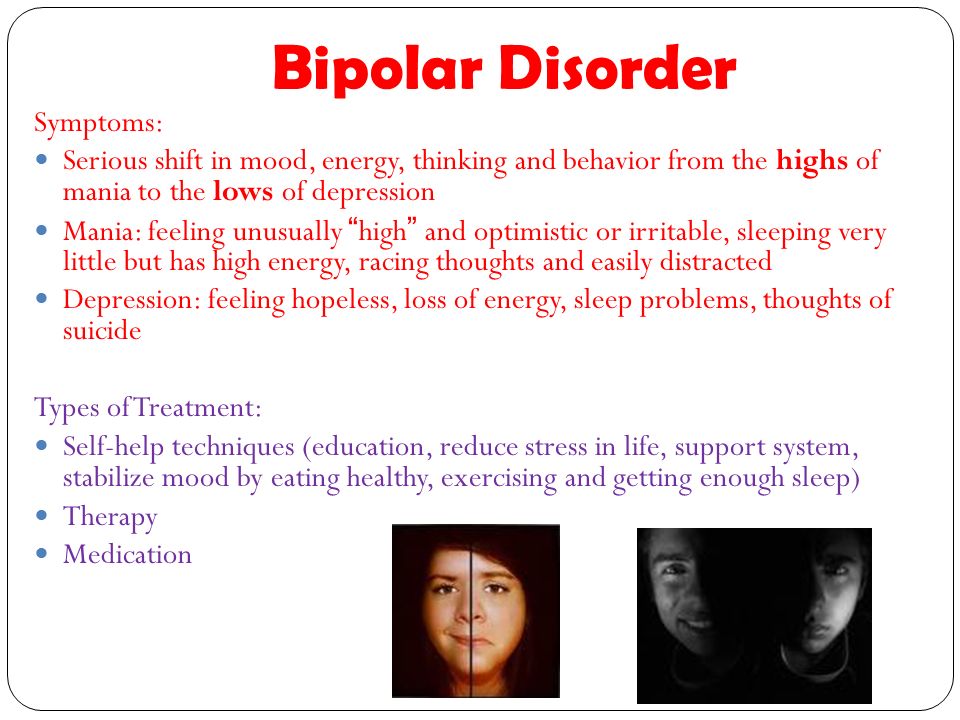

The existence of a mood disorder in adults involving severe mood swings from states of deep depression to states of elation has been recognized now for over a century. This disorder is commonly referred to as manic-depression but is now formally referred to as bipolar disorder, referring to the two “poles” of depression and mania. Until recently, however, youth were rarely diagnosed with this disorder. Bipolar disorder has also become a controversial area within the field of children’s mental health. There is little disagreement about whether it exists. The disagreement is about the symptoms of bipolar disorder in youth and how they differ from those in adults.

First, some definitions

Bipolar disorder involves episodes of both major depression and mania. (To clarify, major depression is another, separate mood disorder involving these same symptoms of depression but

without the occurrence of symptoms of mania). The diagnostic manual used by mental health professionals is based on the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in adults. The following lists consist of behaviors observed by parents of children diagnosed with bipolar disorder.

Behaviors connected to major depressive episodes:

- marked decrease in interest in or pleasure from life, sometimes expressed by boredom

- agitation and irritability

- sleeping too much or inability to sleep

- significant change in appetite

- change in observed activity level (usually slowed down or dragging)

- loss of energy

- inability to concentrate

- frequent sadness or crying

- feelings of worthlessness or guilt

- thoughts of death or suicide or self-destructive behavior

Behaviors connected to mania:

- elevated, expansive or irritable mood

- inflated self esteem or grandiosity (an unrealistic sense of one’s capabilities)

- significantly decreased need for sleep

- much more talkative or pressured speech (speech so rapid that the words bump into and overrun each other)

- racing thoughts or flight of ideas (completely disconnected thoughts)

- distractibility

- excessive involvement in multiple projects and activities

- highly risky pursuit of pleasurable activities (for example, activities involving drugs, alcohol or sex)

The combination of episodes of mania and major depressive episodes is what constitutes classic bipolar disorder. However, more than one type of bipolar disorder exists.

However, more than one type of bipolar disorder exists.

The controversy

As mentioned earlier, mental health practitioners disagree about the symptoms of bipolar disorder in youth and how they differ from those in adults. In adolescents, where the presentation of the disorder more closely resembles that seen in adults, there is much less controversy.

More controversy exists in children when there appears to be a more chronic course, including more irritability and unstable moods, including severe temper outbursts. In short, where does a child with ADHD, oppositional behaviors, and a fair degree of crankiness/moodiness end, and where does a child with bipolar disorder begin.

While no one has the definitive answers to these questions, there are competing schools of thought on this issue. Some experts feel that children with severe irritability, emotional instability, and severe temper outbursts are, in fact, suffering from bipolar disorder as it appears in childhood and should be treated accordingly. Other experts feel this approach will lead to the overdiagnosis of children who in fact suffer from disorders other than bipolar disorder. These experts argue for a narrower definition of bipolar disorder which includes episodic mood swings, elevated or expansive mood—not just irritable mood—and grandiosity or inappropriate euphoria (extreme joyfulness).

Other experts feel this approach will lead to the overdiagnosis of children who in fact suffer from disorders other than bipolar disorder. These experts argue for a narrower definition of bipolar disorder which includes episodic mood swings, elevated or expansive mood—not just irritable mood—and grandiosity or inappropriate euphoria (extreme joyfulness).

These experts clearly recognize that this definition excludes a number of children with episodes of mood instability, explosive rage episodes, extreme irritability and agitation. There is no disagreement that children with these symptoms are impaired. However, experts differ on whether or not such children should be diagnosed with bipolar disorder. Experts also differ on what would be the most appropriate and effective treatment for them.

There are also other factors that can seriously complicate the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children. A history of severe emotional trauma such as physical or sexual abuse can lead to mood swings, emotional outbursts, hallucinations, and extremely severe behavioral problems, including sexualized behaviors that can resemble bipolar disorder. Improving our understanding of all of these issues depends on further research into these disorders as they appear in children and adolescents. Fortunately, some of this research is currently underway and holds the promise of better answers to these important questions in the future.

Improving our understanding of all of these issues depends on further research into these disorders as they appear in children and adolescents. Fortunately, some of this research is currently underway and holds the promise of better answers to these important questions in the future.

Bipolar disorder in children and adolescents

In adults, bipolar disorder commonly involves separate episodes of major depression, alternating with separate episodes of mania. In children mixed states (a mix of mania and depression) and rapid cycling (mood swings) may be much more common. This can make the diagnosis of bipolar disorder much more challenging in these age groups.

Many clinicians have observed that the symptoms of bipolar disorder appear to change as children develop, though these observations have not been confirmed by long-term studies. In younger children chronic irritability and mood instability without classic mood swings may predominate. These symptoms most closely resemble a mixed state of the disorder. In older children and adolescents, episodes including euphoria, grandiosity and paranoia may predominate. In all age groups hyperactivity, distractibility and pressured speech are seen. In general, the older the individual, the more the symptoms may resemble those seen in adults.

In older children and adolescents, episodes including euphoria, grandiosity and paranoia may predominate. In all age groups hyperactivity, distractibility and pressured speech are seen. In general, the older the individual, the more the symptoms may resemble those seen in adults.

Bipolar disorder and ADHD

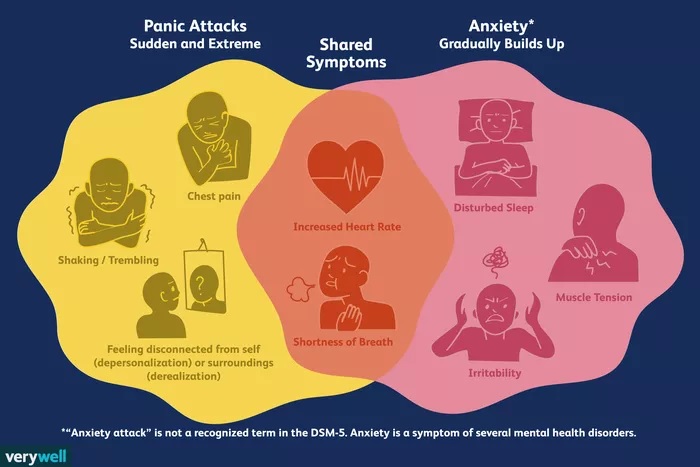

As any parent of a child with ADHD has probably already noted, there is a significant overlap in the symptoms of mania, and to a lesser extent depression, and the symptoms of ADHD. ADHD, mania and depression may all involve inability to concentrate and problems with distractibility. Mania and ADHD may both involve hyperactivity and impulsivity. Though the symptom overlap is significant there are several factors that can help to distinguish these disorders.

ADHD in children usually does not involve mood symptoms such as depression and euphoria to the extent seen in bipolar disorder. ADHD symptoms usually first appear early in childhood while the onset of bipolar disorder appears to occur later in childhood or adolescence (4). ADHD also usually involves normal sleep, at least once a child has settled down in bed and is ready for sleep. Mania, in contrast, involves decreased need for sleep with the individual still “raring to go” the next day despite little sleep. The family history can be helpful, as both disorders appear to run in families.

ADHD also usually involves normal sleep, at least once a child has settled down in bed and is ready for sleep. Mania, in contrast, involves decreased need for sleep with the individual still “raring to go” the next day despite little sleep. The family history can be helpful, as both disorders appear to run in families.

Depression and bipolar disorder

People who suffer from depression, including those who suffer from major depressive disorder, may also eventually exhibit symptoms of bipolar disorder. It is harder to tell the difference between depression and bipolar disorder in children than in adults. Children with depression more often appear irritable than sad. This presents another overlap with the irritability seen in bipolar disorder. Children and adolescents are also by their nature prone to some degree of unstable mood. Determining where this type of moodiness ends and bipolar disorder begins in a depressed young person can present a challenge. Looking for the presence of other symptoms of mania or elevated mood, including the presence of euphoria or grandiosity at some point, is important in making this diagnostic distinction.

Further complicating the picture is the fact that both adults and younger people who initially exhibit symptoms only of depression may later develop bipolar disorder. The risk of depression turning into bipolar disorder is estimated at 10 percent or less in adults but appears to be as high as 20–40 percent in children and adolescents. Several risk factors for the eventual development of bipolar disorder in addition to early onset of depression have been identified, including psychosis, sudden onset, severely slowed or retarded movement, antidepressant-induced mania or elevated mood, and family history of bipolar disorder.

Treatment

Bipolar disorder is a serious disorder that can cause significant problems in school, the family, and the community. Untreated bipolar disorder can lead to hospitalization, drug abuse, accidents, or suicide. Parents who suspect that their child has bipolar disorder should find a child psychiatrist or psychologist who can evaluate the child.

The comprehensive treatment of bipolar disorder, like all other mental illnesses in children and adolescents, involves a multi-modal approach. Of course the first step in treatment is a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation performed by a child psychiatrist or psychologist with experience in the diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children and adolescents. Once the diagnosis is established ongoing treatment can begin. Medications form the foundation of this treatment. These medications have been found effective in adults and are currently being tested in children. At this point medication treatment of bipolar disorder involves the use of a mood stabilizer, which helps to prevent symptoms of mania while also hopefully improving symptoms of depression. In cases where depression remains a problem, the physician may consider prescribing an antidepressant as well as a mood stabilizer. Antidepressants in bipolar patients must be used cautiously, however, as they may cause a manic state.

Some clinicians are reluctant to prescribe stimulant medication for children who meet criteria for ADHD but who also have, or may have, bipolar disorder, because of a concern that bipolar symptoms might become worse. Currently, there is not evidence that this is the case, and research suggests that in general, children who have both ADHD and bipolar disorder can benefit from stimulant medication. However, it is important to be extremely careful in monitoring these children’s response to medication.

Currently, there is not evidence that this is the case, and research suggests that in general, children who have both ADHD and bipolar disorder can benefit from stimulant medication. However, it is important to be extremely careful in monitoring these children’s response to medication.

Other treatments are also very important in the management of this illness. They include measures to try to ensure regular sleep, which helps to keep mood stable. Therapy that educates the child about the importance of taking medication is also important. This is especially true for adolescents where any chronic illness can make it more difficult to achieve independence. Additionally, the family will benefit from comprehensive education and support as they help their child to deal with this very challenging illness. Academic interventions may also be needed (see Education). Finally, coexisting illnesses (other illnesses also present) including ADHD need to be treated.

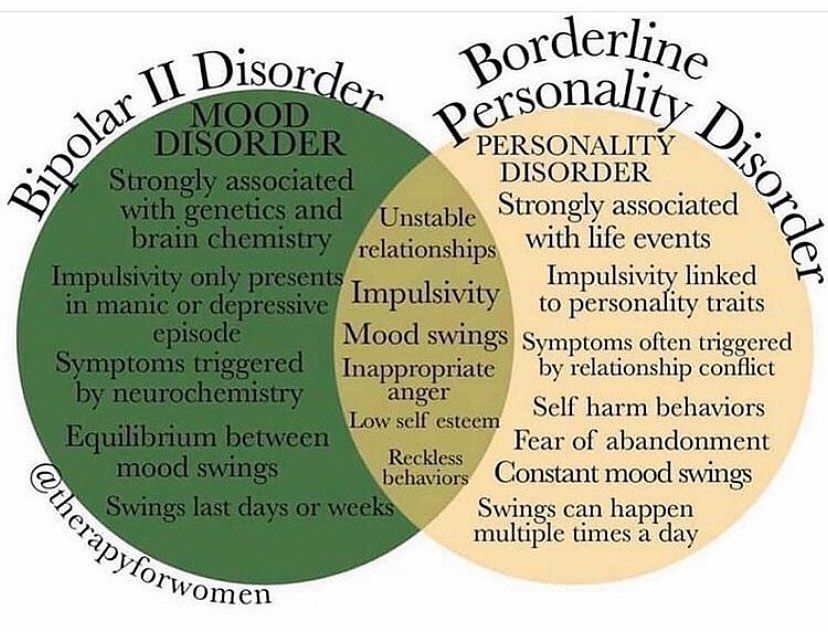

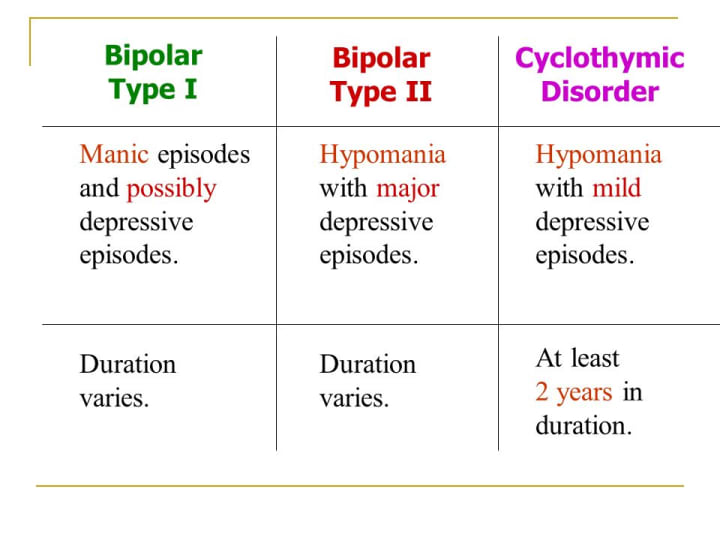

The “classic” combination of mania and major depressive episodes is now referred to as Bipolar I Disorder. Major depressive episodes combined with a less severe expression of manic symptoms (called hypomania) is referred to as Bipolar II Disorder. Hypomania combined with a less pronounced and more longstanding form of depression (known as Dysthymia) is referred to as Cyclothymia. Symptoms of mania and a major depressive episode may also occur in combination simultaneously, this is called a Mixed State of Bipolar disorder. Finally, though episodes of mania and major depression classically occur in well-defined episodes, some people suffer from rapid swings between the two mood states that is referred to as Rapid Cycling. Bipolar I Disorder, Bipolar II Disorder, Cyclothymia, Mixed States and Rapid Cycling States are all considered to be bipolar spectrum disorders.

Major depressive episodes combined with a less severe expression of manic symptoms (called hypomania) is referred to as Bipolar II Disorder. Hypomania combined with a less pronounced and more longstanding form of depression (known as Dysthymia) is referred to as Cyclothymia. Symptoms of mania and a major depressive episode may also occur in combination simultaneously, this is called a Mixed State of Bipolar disorder. Finally, though episodes of mania and major depression classically occur in well-defined episodes, some people suffer from rapid swings between the two mood states that is referred to as Rapid Cycling. Bipolar I Disorder, Bipolar II Disorder, Cyclothymia, Mixed States and Rapid Cycling States are all considered to be bipolar spectrum disorders.

References

- Weller, E.B.; Weller, R.A.;and Fristad, M.A. (1995). “Bipolar disorder in children: misdiagnosis, underdiagnosis and future directions,” Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry34:709–714, 1995.

- Weller, E.B.; Weller, R.A.; Danielyan, A.K. (2004) “Mood disorders in prepubertal children.” In Wiener, J.M., Dulcan, M.D. (editors). Textbook of child and adolescent psychiatry. Washington, D,C.: American Psychiatric Publishing: 418.

- Akiskal, H.S. (1995). “Developmental pathways to bipolarity: are juvenile onset depressions pre-bipolar “Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry . 34:754–763.

- Strober, M.; and Carlson, G. (1982). “Bipolar illness in adolescents with major depression: clinical, genetic and psychopharmacologic predictors in a three-to-four year prospective follow-up investigation,” Archives of General Psychiatry 39:549–555, 1982.

- Carlson, G.A.; Loney, J.; Salisbury, H.; Kramer, J.R.; Arthur, C. (2000). “Stimulant treatment in young boys with symptoms suggesting childhood mania: A report from a longitudinal study.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 10(3): 175–184.

NIMH » Bipolar Disorder in Children and Teens

Does your child go through extreme changes in mood and behavior? Does your child get much more excited or much more irritable than other kids? Do you notice that your child goes through cycles of extreme highs and lows more often than other children? Do these mood changes affect how your child acts at school or at home?

Some children and teens with these symptoms may have bipolar disorder, a brain disorder that causes unusual shifts in mood, energy, activity levels, and day-to-day functioning. With treatment, children and teens with bipolar disorder can get better over time.

What is bipolar disorder?

Bipolar disorder is a mental disorder that causes people to experience noticeable, sometimes extreme, changes in mood and behavior. Sometimes children with bipolar disorder feel very happy or “up” and are much more energetic and active than usual. This is called a manic episode. Sometimes children with bipolar disorder feel very sad or “down” and are much less active than usual. This is called a depressive episode.

This is called a manic episode. Sometimes children with bipolar disorder feel very sad or “down” and are much less active than usual. This is called a depressive episode.

Bipolar disorder, which used to be called manic-depressive illness or manic depression, is not the same as the normal ups and downs every child goes through. The mood changes in bipolar disorder are more extreme, often unprovoked, and accompanied by changes in sleep, energy level, and the ability to think clearly. Bipolar symptoms can make it hard for young people to perform well in school or to get along with friends and family members. Some children and teens with bipolar disorder may try to hurt themselves or attempt suicide.

Most people are diagnosed with bipolar disorder in adolescence or adulthood, but the symptoms can appear earlier in childhood. Bipolar disorder is often episodic, but it usually lasts a lifetime.

Signs and symptoms of bipolar disorder may overlap with symptoms of other disorders that are common in young people, such as attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), conduct problems, major depression, and anxiety disorders. Diagnosing bipolar disorder can be complicated and requires a careful and thorough evaluation by a trained, experienced mental health professional.

Diagnosing bipolar disorder can be complicated and requires a careful and thorough evaluation by a trained, experienced mental health professional.

With treatment, children and teens with bipolar disorder can manage their symptoms and lead successful lives.

What causes bipolar disorder?

The exact causes of bipolar disorder are unknown, but several factors may contribute to the illness.

For example, researchers are beginning to uncover genetic mechanisms that are linked to bipolar disorder and other mental disorders. Research shows that people’s chance of having bipolar disorder is higher if they have a close family member with the illness, which may be because they have the same genetic variations. However, just because one family member has bipolar disorder, it does not mean that other members of the family will have it. Many genes are involved in the disorder, and no single gene causes it.

Research also suggests that adversity, trauma, and stressful life events may increase the chances of developing bipolar disorder in people with a genetic risk of having the illness.

Some research studies have found differences in brain structure and function between people who have bipolar disorder and those who do not. Researchers are studying the disorder to learn more about its causes and effective treatments.

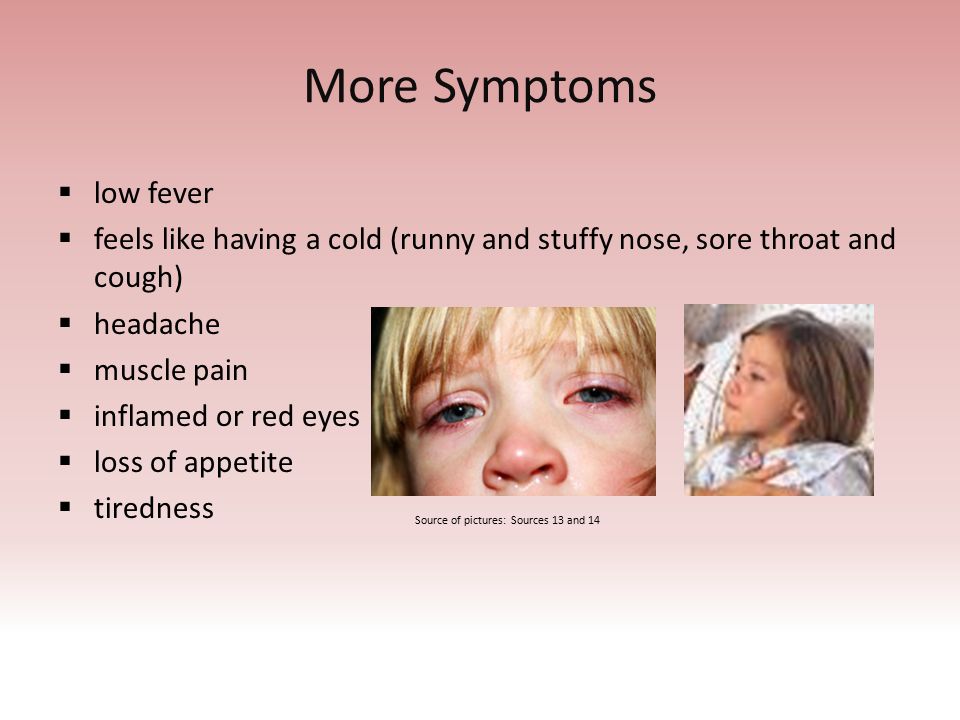

What are the symptoms of bipolar disorder?

Mood episodes in bipolar disorder include intense emotions along with significant changes in sleep habits, activity levels, thoughts, or behaviors. A person with bipolar disorder may have manic episodes, depressive episodes, or “mixed” episodes. A mixed episode has both manic and depressive symptoms. These mood episodes cause symptoms that often last for several days or weeks. During an episode, the symptoms last every day for most of the day.

These mood and activity changes are very different from the child’s usual behavior and from the behavior of healthy children and teens.

Children and teens having a manic episode may:

- Show intense happiness or silliness for long periods of time.

- Have a very short temper or seem extremely irritable.

- Talk fast about a lot of different things.

- Have trouble sleeping but not feel tired.

- Have trouble staying focused, and experience racing thoughts.

- Seem overly interested or involved in pleasurable but risky activities.

- Do risky or reckless things that show poor judgment.

Children and teens having a depressive episode may:

- Feel frequent and unprovoked sadness.

- Show increased irritability, anger, or hostility.

- Complain a lot about pain, such as stomachaches and headaches.

- Have a noticeable increase in amount of sleep.

- Have difficulty concentrating.

- Feel hopeless and worthless.

- Have difficulty communicating or maintaining relationships.

- Eat too much or too little.

- Have little energy and no interest in activities they usually enjoy.

- Think about death, or have thoughts of suicide.

Can children and teens with bipolar disorder have other problems?

Young people with bipolar disorder can have several problems at the same time. These include:

- Misuse of alcohol and drugs. Young people with bipolar disorder are at risk of misusing alcohol or drugs.

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Children and teens who have both bipolar disorder and ADHD may have trouble staying focused.

- Anxiety disorders. Children and teens with bipolar disorder also may have an anxiety disorder.

Sometimes extreme behaviors go along with mood episodes. During manic episodes, young people with bipolar disorder may take extreme risks that they wouldn’t usually take or that could cause them harm or injury. During depressive episodes, some young people with bipolar disorder may think about running away from home or have thoughts of suicide.

If your child shows signs of suicidal thinking, take these signs seriously and call your child’s health care provider.

If you think your child is in crisis and needs immediate help, call 911. You also can call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (Lifeline) at 1‑800‑273‑TALK (8255), or text the Crisis Text Line (text HELLO to 741741). These services are confidential, free, and available 24/7.

How is bipolar disorder diagnosed?

A health care provider will ask questions about your child’s mood, sleeping patterns, energy levels, and behavior. There are no blood tests or brain scans that can diagnose bipolar disorder. However, the health care provider may use tests to see if something other than bipolar disorder is causing your child’s symptoms. Sometimes health care providers need to know about medical conditions in the family, such as depression or substance use.

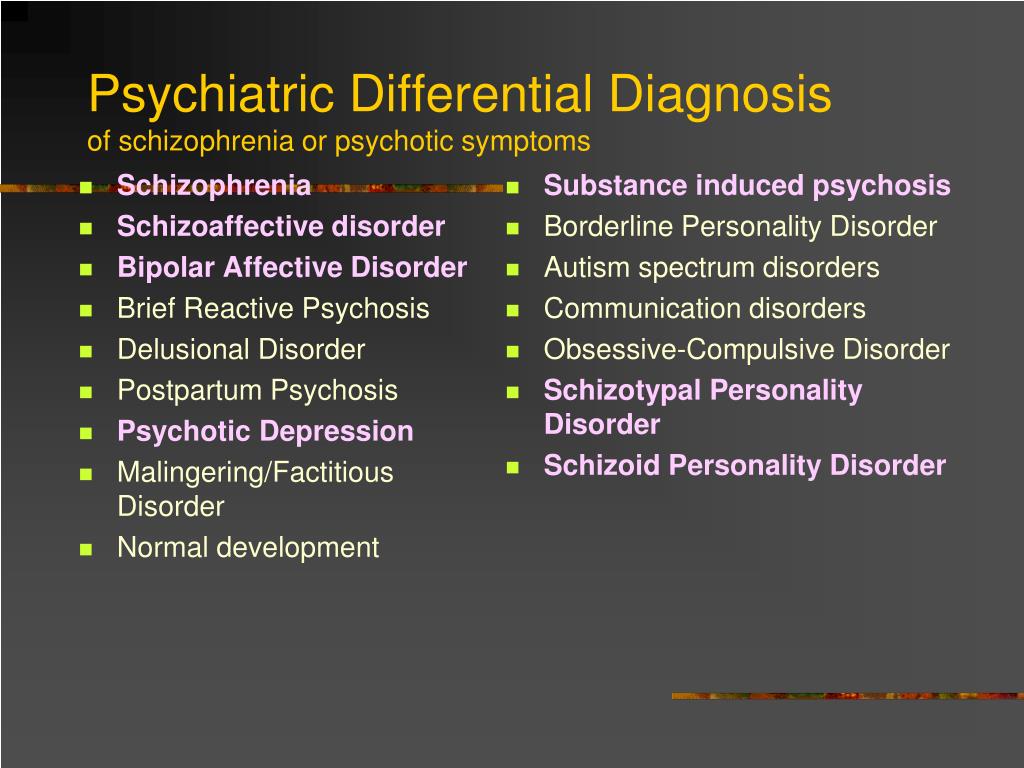

Other disorders have symptoms like those of bipolar disorder, including ADHD, disruptive mood regulation disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, conduct disorder, and anxiety disorders. It also can be challenging to distinguish bipolar disorder from depression that occurs without mania, which is referred to as “major depression.” A health care provider who specializes in working with children and teens can make a careful and complete evaluation of your child’s symptoms to provide the right diagnosis.

It also can be challenging to distinguish bipolar disorder from depression that occurs without mania, which is referred to as “major depression.” A health care provider who specializes in working with children and teens can make a careful and complete evaluation of your child’s symptoms to provide the right diagnosis.

How is bipolar disorder treated?

Children and teens can work with their health care provider to develop a treatment plan that will help them manage their symptoms and improve their quality of life. It is important to follow the treatment plan, even when your child is not currently experiencing a mood episode. Steady, dependable treatment works better than treatment that starts and stops.

Treatment options include:

- Medication. Several types of medication can help treat symptoms of bipolar disorder. Children respond to medications in different ways, so the right type of medication depends on the child.

This means children may need to try different types of medication to see which one works best for them. Some children may need more than one type of medication because their symptoms are complex. Children should take the fewest number of medications and the smallest doses possible to help their symptoms. A good way to remember this is “start low, go slow.” Medications can cause side effects. Always tell your child’s health care provider about any problems with side effects. Do not stop giving your child medication without speaking to a health care provider. Stopping medication suddenly can be dangerous and can make bipolar symptoms worse.

This means children may need to try different types of medication to see which one works best for them. Some children may need more than one type of medication because their symptoms are complex. Children should take the fewest number of medications and the smallest doses possible to help their symptoms. A good way to remember this is “start low, go slow.” Medications can cause side effects. Always tell your child’s health care provider about any problems with side effects. Do not stop giving your child medication without speaking to a health care provider. Stopping medication suddenly can be dangerous and can make bipolar symptoms worse. - Psychosocial Therapy. Different kinds of psychosocial therapy can help children and their families manage the symptoms of bipolar disorder. Therapies that are based on scientific research—including cognitive behavioral approaches and family-focused therapy—can provide support, education, and guidance to youth and their families.

These therapies teach skills that can help people manage bipolar disorder, including skills for maintaining routines, enhancing emotion regulation, and improving social interactions.

These therapies teach skills that can help people manage bipolar disorder, including skills for maintaining routines, enhancing emotion regulation, and improving social interactions.

What can children and teens expect from treatment?

With treatment, children and teens with bipolar disorder can get better over time. Treatment is more effective when health care providers, parents, and young people work together.

Sometimes a child’s symptoms may change, or disappear and then come back. When this happens, your child’s health care provider may recommend changes to the treatment plan. Treatment can take time, but sticking with the treatment plan can help young people manage their symptoms and reduce the likelihood of future episodes.

Your child’s health care provider may recommend keeping a daily life chart or mood chart to track your child’s moods, behaviors, and sleep patterns. This may make it easier to track the illness and see whether treatment is working.

How can I help my child or teen?

Help begins with the right diagnosis and treatment. Talk to your family health care provider about any symptoms you notice.

If your child has bipolar disorder, here are some basic things you can do:

- Be patient.

- Encourage your child to talk, and listen to your child carefully.

- Pay attention to your child’s moods, and be alert to any major changes.

- Understand triggers, and learn strategies for managing intense emotions and irritability.

- Help your child have fun.

- Remember that treatment takes time: sticking with the treatment plan can help your child get better and stay better.

- Help your child understand that treatment can make life better.

How does bipolar disorder affect caregivers and families?

Caring for a child or teenager with bipolar disorder can be stressful for parents and families. Coping with a child’s mood episodes and other problems—such as short tempers and risky behaviors—can challenge any caregiver.

Coping with a child’s mood episodes and other problems—such as short tempers and risky behaviors—can challenge any caregiver.

It is important that caregivers take care of themselves, too. Find someone you can talk to or consult your health care provider about support groups. Finding support and strategies for managing stress can help you and your child.

Where do I go for help?

If you’re not sure where to get help, your doctor, pediatrician, or other family health care provider is a good place to start. A health care provider can refer you to a qualified mental health professional, such as a psychiatrist or psychologist, who has experience treating bipolar disorder and can evaluate your child’s symptoms.

You can learn more about getting help and finding a health care provider on the National Institute of Mental Health website. Hospital health care providers can help in an emergency. The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has an online tool to help you find mental health services in your area.

I know someone who is in crisis. What do I do?

If you know someone who might be thinking about hurting themselves or someone else, get help quickly.

- Do not leave the person alone.

- Call 911 or go to the nearest hospital emergency room.

- Call the toll-free National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255) or the toll-free TTY number at 1-800-799-4TTY (4889). You also can text the Crisis Text Line (text HELLO to 741741) or go to the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline website.

What should I know about clinical trials?

Clinical trials are research studies that look at new ways to prevent, detect, or treat diseases and conditions. Although individuals may benefit from being part of a clinical trial, participants should be aware that the primary purpose of a clinical trial is to gain new scientific knowledge so that others may be better helped in the future.

Researchers at NIMH and around the country conduct clinical trials with patients and healthy volunteers. Talk to your health care provider about clinical trials, their benefits and risks, and whether one is right for you. For more information, visit the NIMH Clinical Trials webpage.

Reprints

This publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced or copied without permission from NIMH. Citation of NIMH as a source is appreciated. To learn more about using NIMH publications, please contact the NIMH Information Resource Center at 1-866‑615‑6464, email [email protected], or refer to our reprint guidelines.

For More Information

MedlinePlus (National Library of Medicine) (En español)

ClinicalTrials.gov (En español)

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH AND HUMAN SERVICES

National Institutes of Health

NIH Publication No. 20-MH-8081

Revised 2020

Bipolar affective disorder in children and adolescents - diagnosis and treatment at the Allianz Central Medical Health Center

2017-11-02

Mood swings happen to all people, and they are not at all uncommon in children and adolescents. These are the characteristics of growing up. However, it is necessary to separate the emotional lability inherent in adolescents from pathological manifestations, which are characterized, first of all, by abrupt changes not only in mood, but also in behavior, as well as energy levels, which clearly prevent the child or adolescent from functioning normally and maladjust him in everyday life. Such symptoms may be signs of bipolar affective disorder or, as this disease was previously called, manic-depressive psychosis.

These are the characteristics of growing up. However, it is necessary to separate the emotional lability inherent in adolescents from pathological manifestations, which are characterized, first of all, by abrupt changes not only in mood, but also in behavior, as well as energy levels, which clearly prevent the child or adolescent from functioning normally and maladjust him in everyday life. Such symptoms may be signs of bipolar affective disorder or, as this disease was previously called, manic-depressive psychosis.

Signs of bipolar affective disorder

Symptoms of bipolar disorder can be observed in children aged seven years and older, but in most cases, the onset of the disease coincides in time with a period of intense puberty. Particular attention should be paid to children and adolescents who are in a depressed state. In such cases, a thorough diagnosis is necessary to exclude bipolar disorder.

As a rule, young patients with bipolar affective disorder very quickly move from a phase of painfully elevated mood (mania or hypomania) to a pronounced decrease in the general emotional background (depression). Moreover, such differences contribute to the formation of general irritability during periods of normal state between these episodes.

Moreover, such differences contribute to the formation of general irritability during periods of normal state between these episodes.

Usually parents note the unpredictability of their children, but often attribute it to character traits and teenage behavior. The risk of developing bipolar disorder is increased in children suffering from hyperactivity, anxiety disorders and attention deficit.

When to call a specialist

Consultation with a psychiatrist-psychotherapist is necessary if the following symptoms are present, provided that they are of a permanent nature:

- Sudden mood swings from a state of euphoria to complete despondency or aggressiveness and irritability.

- Painfully high self-esteem.

- Changes and sudden changes in energy levels.

- Excessive, previously unusual activity.

- Changes in speech habits: begins to talk a lot, speech is accelerated, sometimes slurred, quickly jumps from one topic to another, not taking into account the reaction of the interlocutor.

- Use of drugs or alcohol.

- Sexual activity.

- Depression, depressed mood, tearfulness.

- Closure, reduction of the circle of communication, narrowing of the circle of interests.

- Feeling of guilt, feeling of own uselessness and worthlessness.

- Suicidal thoughts or talk, self-destructive behavior.

It should be borne in mind that bipolar disorder responds well to correction. As a rule, the first diagnosis is made by a psychotherapist, to whom parents turn in case of alarming symptoms and painful changes in the behavior and habits of the child. In the future, it is also necessary to consult a psychiatrist and, in most cases, prescribe drug therapy.

The help of a psychotherapist is required for a child or adolescent at all stages of treatment for bipolar disorder, but especially at the stage of rehabilitation.

The specialist will help the patient to adapt faster and select methods of therapy that reduce the risk of relapse.

Author: Specialist of the Alyans Mental Health Center

TsMZ "Alliance"

Bipolar disorder | Symptoms, complications, diagnosis and treatment

Bipolar disorder, formerly called manic depression, is a mental health condition that causes extreme mood swings that include emotional highs (mania or hypomania) and lows (depression). Episodes of mood swings may occur infrequently or several times a year.

When you become depressed, you may feel sad or hopeless and lose interest or pleasure in most activities. When the mood shifts to mania or hypomania (less extreme than mania), you may feel euphoric, full of energy or unusually irritable. These mood swings can affect sleep, energy, alertness, judgment, behavior, and the ability to think clearly.

Although bipolar disorder is a lifelong condition, you can manage your mood swings and other symptoms by following a treatment plan. In most cases, bipolar disorder is treated with medication and psychological counseling (psychotherapy).

In most cases, bipolar disorder is treated with medication and psychological counseling (psychotherapy).

Symptoms

There are several types of bipolar and related disorders. These may include mania, hypomania, and depression. Symptoms can lead to unpredictable changes in mood and behavior, leading to significant stress and difficulty in life.

- Bipolar I. You have had at least one manic episode, which may be preceded or accompanied by hypomanic or major depressive episodes. In some cases, mania can cause a break with reality (psychosis).

- Bipolar disorder II. You have had at least one major depressive episode and at least one hypomanic episode, but never had a manic episode.

- Cyclothymic disorder. You have had at least two years - or one year in children and adolescents - many periods of hypomanic symptoms and periods of depressive symptoms (though less severe than major depression).

- Other types. These include, for example, bipolar and related disorders caused by certain drugs or alcohol or due to health conditions such as Cushing's disease, multiple sclerosis or stroke.

Bipolar II is not a milder form of Bipolar I but is a separate diagnosis. Although bipolar I manic episodes can be severe and dangerous, people with bipolar II can be depressed for longer periods of time, which can cause significant impairment.

Although bipolar disorder can occur at any age, it is usually diagnosed in adolescence or early twenties. Symptoms can vary from person to person, and symptoms can change over time.

Mania and hypomania

Mania and hypomania are two different types of episodes, but they share the same symptoms. Mania is more pronounced than hypomania and causes more noticeable problems at work, school, and social activities, as well as relationship difficulties. Mania can also cause a break with reality (psychosis) and require hospitalization.

Both a manic episode and a hypomanic episode include three or more of these symptoms:

- Abnormally optimistic or nervous

- Increased activity, energy or excitement

- Exaggerated sense of well-being and self-confidence (euphoria)

- Reduced need for sleep

- Unusual talkativeness

- Distractibility

- Poor decision-making - for example, in speculation, in sexual encounters or in irrational investments

Major depressive episode

A major depressive episode includes symptoms that are severe enough to cause noticeable difficulty in daily activities such as work, school, social activities, or relationships. Episode includes five or more of these symptoms:

- Depressed mood, such as feeling sad, empty, hopeless, or tearful (in children and adolescents, depressed mood may present as irritability)

- Marked loss of interest or feeling of displeasure in all (or nearly all) activities

- Significant weight loss with no diet, weight gain, or decreased or increased appetite (in children, failure to gain weight as expected may be a sign of depression)

- Either insomnia or sleeping too much

- Either restlessness or slow behavior

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Feelings of worthlessness or excessive or inappropriate guilt

- Decreased ability to think or concentrate, or indecisiveness

- Thinking, planning or attempting suicide

Other features of bipolar disorder

Signs and symptoms of bipolar I and bipolar II disorder may include other signs such as anxiety disorder, melancholia, psychosis, or others.