Does birth control make you crazy

Feel like a different person on the pill? Here’s how it affects your mood |

Science Mar 26, 2020 / Sarah E. Hill PhD

Dingding Hu

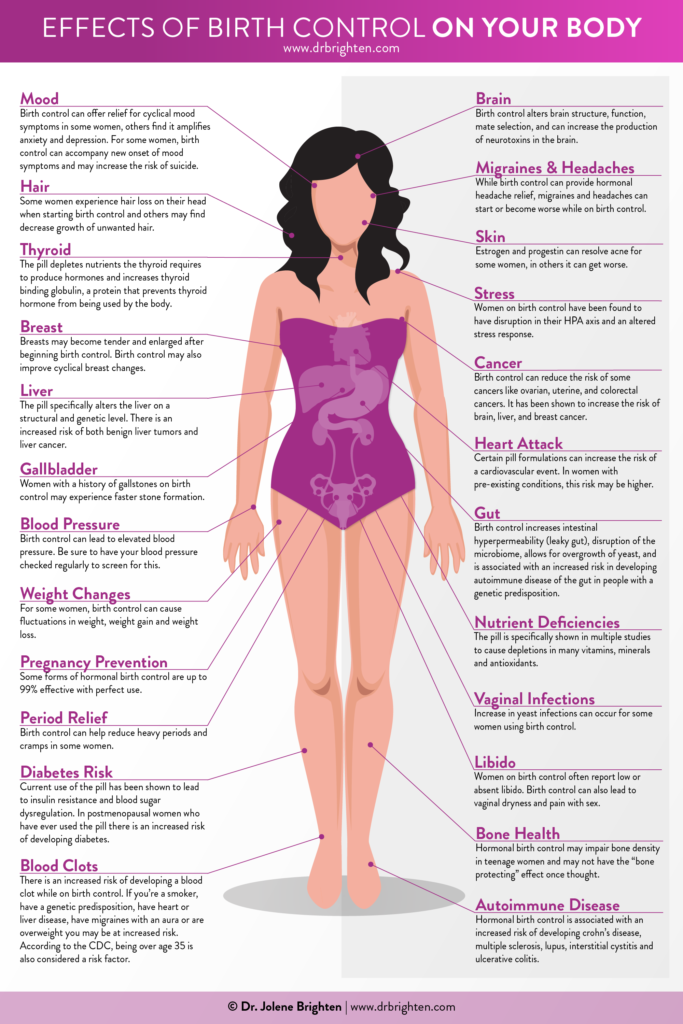

If you think your contraception is making you anxious or depressed, you’re not imagining things. Evolutionary psychologist Sarah E. Hill explains what happens to your brain on birth control.

Most women know at least one or two other women who have had a bad reaction to the pill. In fact, the question that many of us have about the pill: “Why does the pill make me crazy?”

Before I get into what the research says about all this, let me just address the elephant in the room — the whole thing about women’s sex hormones influencing mood. Which they do. This might be the world’s oldest cliché about women, but that doesn’t make it any less true. Women’s sex hormones influence women’s moods. Men’s sex hormones affect men’s moods. It would be impossible for them not to.

Back to the question. To start with, all of us feel a little crazy sometimes. Life is hard and can make anyone feel anxious and overwhelmed at times. For some women, being on the pill can magnify these feelings, leading to anxiety disorders and depression. But if these things happen to you, it doesn’t mean you’re crazy; it just means you’re on the wrong pill.

Mood-related issues like anxiety and depression are super-common among women on the pill. Almost half of all women who go on the pill stop using it within the first year because of intolerable side effects, and the one most frequently cited is unpleasant changes in mood. Sometimes it’s intolerable anxiety; other times, it’s intolerable depression; or maybe both simultaneously. And even though some women’s doctors may tell them that those mood changes aren’t real or important, a growing body of research suggests otherwise.

The Scandinavian nation of Denmark is home to a number of nationwide registers, collections of data from its citizens on different health and social issues. Because all Danish citizens have a unique personal identification number, researchers have been able to link individual people’s data across different registers, giving them access to tons of information about patterns of health and social behavior in a whole population.

Because all Danish citizens have a unique personal identification number, researchers have been able to link individual people’s data across different registers, giving them access to tons of information about patterns of health and social behavior in a whole population.

From these registers, we’ve learned valuable lessons about the powerful effects that the birth control pill can have on mood. In the first of these studies, the researchers looked at the records of all the healthy, nondepressed women living in Denmark between the ages of 15 and 34. They then followed the prescription and mental health records of these women (more than a million of them) for 14 years to see whether going on hormonal contraceptives influenced the likelihood of later being diagnosed with depression or being prescribed antidepressants.

The researchers found that women on hormonal contraceptives were 50 percent more likely to be diagnosed with depression six months later, compared with women who were not prescribed hormonal contraceptives during this time. They also found the women on hormonal contraceptives were 40 percent more likely to be prescribed an antidepressant than were women who weren’t prescribed hormonal contraceptives during this time. The results of this study, as well as others, suggest the pill can increase some women’s risk of depression. This seemed particularly true for non-oral products (such as a patch, vaginal ring or hormonal IUD) and for young women (ages 15 to 19), whose brains are not yet done developing and may be more prone to the influence of hormonal signaling.

They also found the women on hormonal contraceptives were 40 percent more likely to be prescribed an antidepressant than were women who weren’t prescribed hormonal contraceptives during this time. The results of this study, as well as others, suggest the pill can increase some women’s risk of depression. This seemed particularly true for non-oral products (such as a patch, vaginal ring or hormonal IUD) and for young women (ages 15 to 19), whose brains are not yet done developing and may be more prone to the influence of hormonal signaling.

As a scientist, I’m obliged to point out we don’t know for sure that the pills caused this increase. Correlation doesn’t equal causation. It’s possible the researchers found pill taking and depression to be related because they were each related to some other third variable. For instance, women who seek medical interventions to prevent pregnancy might be more likely to seek medical interventions for depression. Or, getting into a new sexual relationship (which can prompt a pill prescription) could be what’s increasing women’s depression risk.

However, the researchers statistically tested for the influence of a number of third variables, and each of these tests found that hormonal contraceptives predicted depression risk even after statistically controlling for these third variables. Even though this wasn’t a double-blind, placebo-controlled experiment, the researchers took great care with their study design and data analysis and the results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine, the top medical journal in the US.

More recently, the same team looked at whether hormonal contraceptives might increase women’s risk of suicide. Researchers tracked hormonal contraceptive usage and suicide attempts and deaths in all Danish women who’d turned 15 between 1996 and 2013. (As in their prior study, they did not include any women who had previously diagnosed psychological problems or who had used antidepressants. They also didn’t include women already on hormonal contraceptives when they entered the study. ) They followed the women for an average of eight years and then compared the likelihood of having attempted or successfully committed suicide among the women who were prescribed hormonal contraceptives and those who were not.

) They followed the women for an average of eight years and then compared the likelihood of having attempted or successfully committed suicide among the women who were prescribed hormonal contraceptives and those who were not.

The women on hormonal contraceptives were twice as likely to have attempted suicide during this time than the women not on hormonal contraceptives. But the risk of successful suicide attempts was actually higher: It was triple that of women not on hormonal contraceptives. As with depression risk, the biggest negative impact of hormonal contraceptives on suicide risk was found for young women (ages 15 to 19) on non-oral products.

When it comes to why the pill can mess with your mood, the two systems that shoulder most of the blame are the HPA axis and some of our neurotransmitter systems. First, the HPA axis (or hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis). It’s made up of three systems working together — the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, the adrenal glands — and plays a central role in the body’s stress response. The type of blunting of the HPA axis we tend to see in pill-taking women is a known contributor to mental health problems, including the types of mood disturbances characteristic of PTSD. Because lacking the biological tools necessary to deal with stress literally harms your ability to cope, having a broken stress response might be a key player in the development of anxiety and depression. It could also harm emotional well-being in indirect ways through its negative impact on our ability to absorb emotionally meaningful events from our environments.

The type of blunting of the HPA axis we tend to see in pill-taking women is a known contributor to mental health problems, including the types of mood disturbances characteristic of PTSD. Because lacking the biological tools necessary to deal with stress literally harms your ability to cope, having a broken stress response might be a key player in the development of anxiety and depression. It could also harm emotional well-being in indirect ways through its negative impact on our ability to absorb emotionally meaningful events from our environments.

The second piece is the role that neurotransmitter systems play in making women feel lousy on the pill. Before I explain, I need you to know three quick things.

Quick Thing 1: Neurotransmitters are chemicals that the brain uses to communicate with itself and the rest of the body.

Quick Thing 2: Excitatory neurotransmitters tell your brain cells to get ready for action, making them more likely to fire off messages to other brain cells.

Quick Thing 3: Inhibitory neurotransmitters tell your brain cells to slow their roll, making them less likely to fire off messages to other cells in the brain.

The most prevalent and frequently used inhibitory neurotransmitter in the brain is GABA. It’s often on the scene in a big way when your brain is trying to slow itself down. GABA gets released when you’re relaxing in your PJ pants, and it’s also released when doing things like meditation and yoga.

Interestingly, you can get a relaxed GABA-rific experience from other things that stimulate GABA receptors, such as alcohol and benzodiazepines like Xanax. And our bodies actually produce compounds that work much like alcohol and Xanax. One of the most powerful is allopregnanolone, a neurosteroid. It gets synthesized when progesterone is broken down in the body and has the effect of kick-starting action by your GABA receptors.

Unfortunately for women on the pill, the artificial progestins in the pill don’t seem to offer this same benefit. In fact, research suggests that women on the pill may have lower levels of these natural sedatives relative to what’s observed in its absence, regardless of the point in the cycle.

In fact, research suggests that women on the pill may have lower levels of these natural sedatives relative to what’s observed in its absence, regardless of the point in the cycle.

This can mean bad news for women’s mental health. When GABA receptors aren’t properly stimulated, it’s known to make people feel anxious, overwhelmed and depressed. A number of mental-health-related issues, including panic disorder, depression, bipolar disorder and the mood-related symptoms of PMS, are characterized by lower-than-average levels of GABAergic activity. Lack of such activity can also increase a person’s risk of alcohol dependence.

Research suggests that changes in dopamine and serotonin signaling may also play a role in mood-related changes seen on the pill. Dopamine and serotonin, like GABA, are neurotransmitters. These chemicals come on the scene when we’re spending time with people we love, eating hot fudge sundaes, falling in love, having sex and having orgasms.

Not surprisingly, these neurotransmitter systems change what they do in response to women’s cyclically changing sex hormones. In particular, the research finds that estrogen makes rewarding things feel even more rewarding than they do in its absence and that progesterone attenuates these effects. Estrogen makes sex feel sexier, chocolate taste yummier, and getting status boosts feel boost-ier.

Given that the pill keeps estrogen levels low across the cycle and stimulates progesterone receptors, it’s possible the pill might have the effect of dampening reward processing in the brain. And if the world seems unrewarding, this makes us feel depressed. One hallmark symptom of depression is that people no longer find pleasure in things that they used to find pleasure in. So it’s also possible that the pill might increase a person’s risk of depression by making pleasure less pleasurable. Consistent with this idea, research finds that pill-taking women — when compared with their naturally cycling counterparts — have a blunted positive emotional response to happy things and don’t experience activity in the reward centers of their brains when looking at pictures of their romantic partners.

It seems pretty clear from the research that the pill can cause some women some pretty serious problems with their mental health, but the science isn’t yet at a point where we can make strong predictions about exactly what’s going to happen to whom, and on what.

However, according to the research, you might have a greater risk of experiencing negative mood effects on the pill if:

- You have a history of depression or mental illness (although there is also evidence that the pill can stabilize mood in certain women with mental illness).

- You have a personal or family history of mood-related side effects on the birth control pill.

- You are taking progestin-only pills.

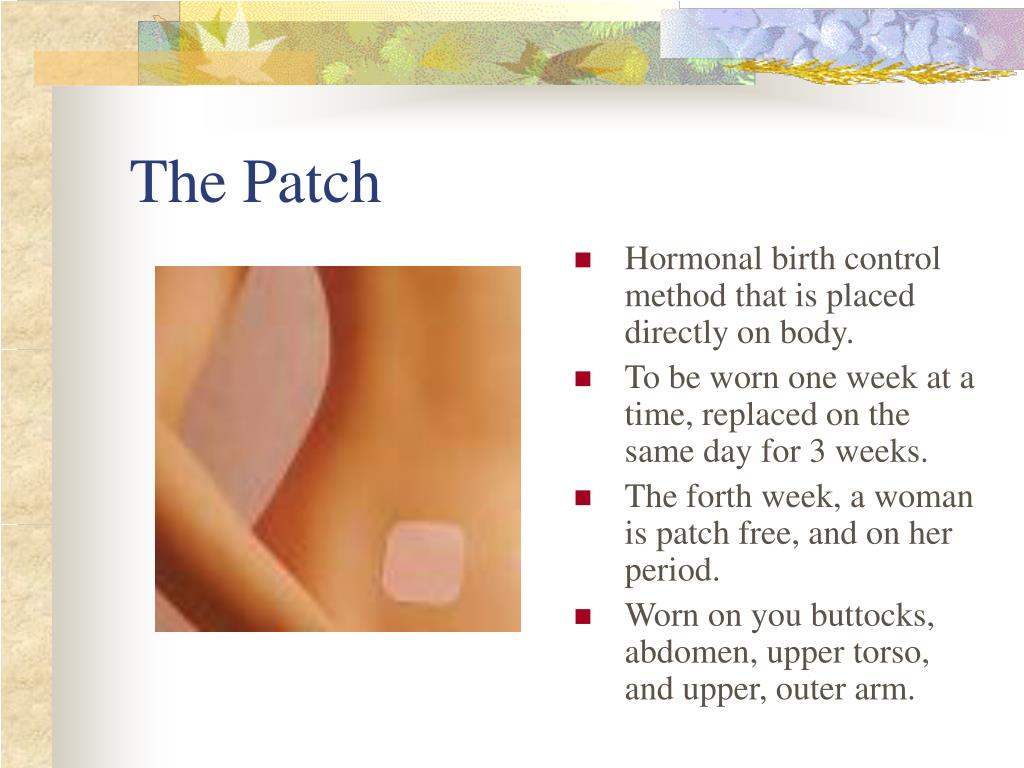

- You are using a non-oral product.

- You are taking multi-phasic pills (pills with an increasing dose of hormones across the cycle rather than a constant dose).

- You are 19 or younger.

These bullet points can give you a starting point to initiate a conversation with your doctor about any mental health concerns. They aren’t your fate, though. Even if you’re an 18-year-old with a family history of depression and you’re on the birth control patch, if you aren’t experiencing signs of troubled mental health, the chances are incredibly low that you’re going to suddenly develop mood problems from birth control. This is especially true if you’ve been on it for a while and seem to be tolerating it well.

They aren’t your fate, though. Even if you’re an 18-year-old with a family history of depression and you’re on the birth control patch, if you aren’t experiencing signs of troubled mental health, the chances are incredibly low that you’re going to suddenly develop mood problems from birth control. This is especially true if you’ve been on it for a while and seem to be tolerating it well.

What’s more, while some women experience negative mood changes on the pill, some women experience the opposite reaction. They feel a whole lot better and mentally healthier on the pill than off it. Research also finds that the pill can offer huge mood-stabilizing benefits to women who have severe PMS.

The most critical thing about the pill’s effects will come from you: How do you feel on it?

Any time you start a new pill, please let someone close to you know about it. Ask them to make note and tell you if they notice any changes in your behavior that might suggest the onset of depression.

Because the hormones in the pill influence what the brain does, it’s almost impossible to separate out what the hormones are doing from who we are. We feel like the version of reality that is created by our brain on the pill is real. This can make it difficult to notice depression creeping in. Rather than feeling like the pill is messing with our mood, it just feels like our life is getting crappier or our job has gotten more stressful. If you tell your person that you are trying a new pill, they may be able to help you recognize problems that start to develop so that you can look for a new pill or an alternative means of protecting yourself from pregnancy.

On top of this, consider keeping a journal. If possible, start it before going on the pill so you have a log of how you were feeling before and after. Having hard evidence of your mood prior to the pill can be a good way for you to think about your past more objectively, making it easier to recognize any changes. In each entry, make note of your mood, energy level and well-being using some sort of scale (1=”I feel sad/anxious” and 10=”I feel great”). This will help you keep tabs on how things change for you (or not) when trying out a new pill.

In each entry, make note of your mood, energy level and well-being using some sort of scale (1=”I feel sad/anxious” and 10=”I feel great”). This will help you keep tabs on how things change for you (or not) when trying out a new pill.

If you’re already on the pill, it’s not too late to keep track of how you’re feeling. Make a note of your patterns. If you have more happy days than sad ones, that probably means everything’s on the right track. None of us feel happy all the time, but we should feel happier more often than sad when things in our lives are going well. If you have fewer happy days than you think you should, talk to your doctor. It could be time to try a new pill or address an issue with your mental health that you’ve let go too long.

Excerpted with permission from the new book This Is Your Brain on Birth Control: The Surprising Science of Women, Hormones, and the Law of Unintended Consequences by Sarah E. Hill PhD. Published by Avery, an imprint of Penguin Random House, LLC. © 2019 by Sarah E. Hill.

© 2019 by Sarah E. Hill.

Watch her TEDxVienna Talk now:

Does Birth Control Make You Moody?

Written by Hope Cristol

Medically Reviewed by Traci C. Johnson, MD on May 06, 2021

In this Article

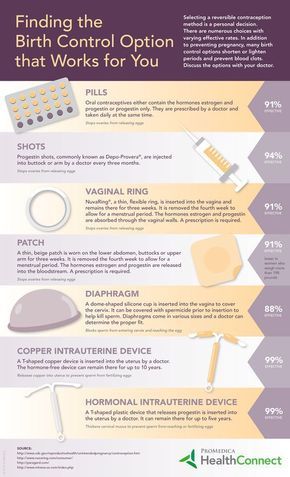

- How Hormonal Contraceptives Work

- Is There a Link Between Birth Control and Emotions?

- Benefits

- Possible Explanations

- When to See a Doctor

Lots of women get irritable, depressed, or feel out of sorts just before their monthly periods. Those can be symptoms of a common condition called premenstrual syndrome (PMS).

But could your birth control pills and other hormonal contraceptives trigger similar emotional swings? Or might they do the reverse and actually improve your moods?

How Hormonal Contraceptives Work

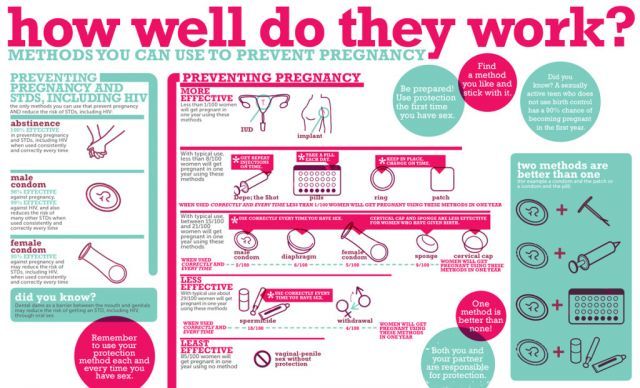

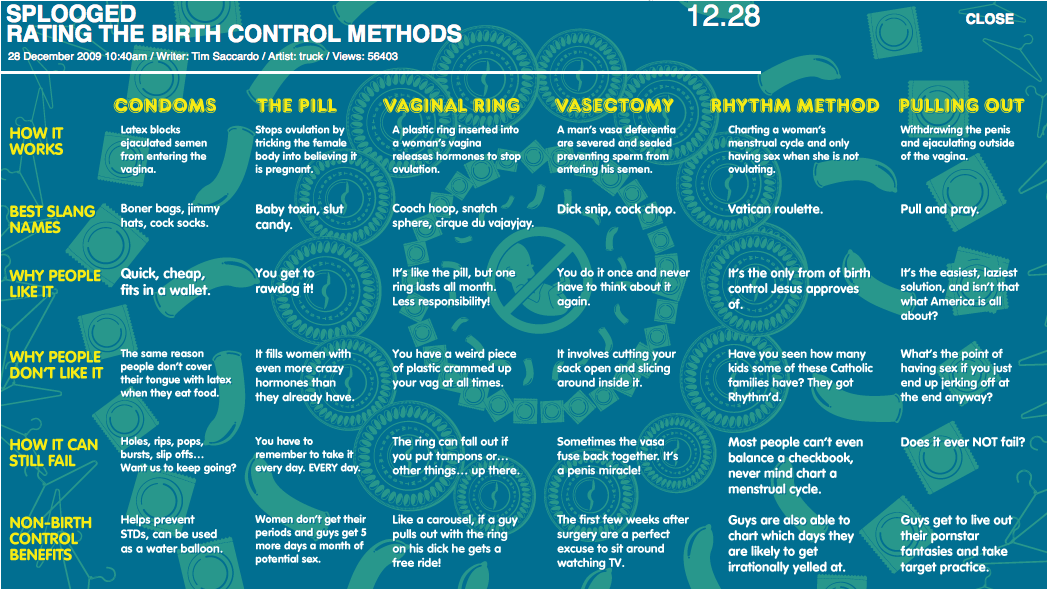

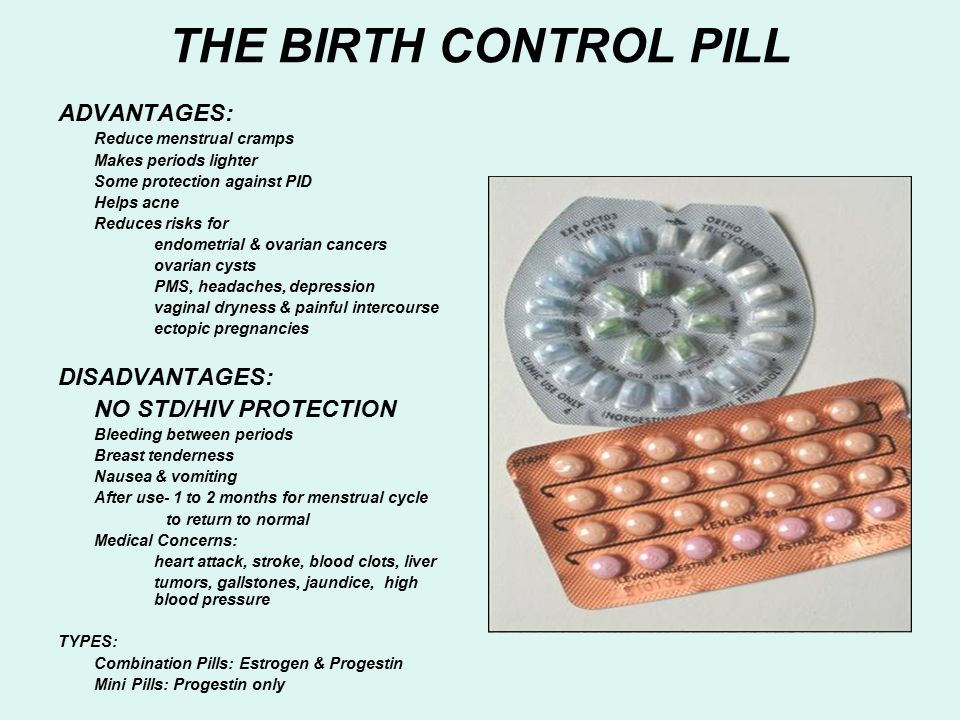

Most birth control pills, patches, and rings combine two lab-made female sex hormones, estrogen and progestin. “Minipills” have only progestin, and in a smaller amount.

“Minipills” have only progestin, and in a smaller amount.

Combined hormonal contraceptives stop the normal rise and fall of your body’s natural hormones. That blocks your body from ovulating and releasing an egg to be fertilized by sperm.

Is There a Link Between Birth Control and Emotions?

Women have complained about mood-related changes like depression and anxiety ever since the pill came out in 1960. The newest generation of pills have lower doses of hormones. Even so, a sizeable number of women still quit the pill because of side effects.

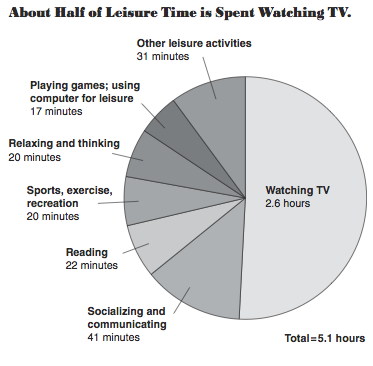

During a typical 28-day menstrual cycle, estrogen levels reach their peak around day 14. That’s when many women feel best emotionally and physically. Most hormonal contraceptives smooth this mountain-shaped hormonal cycle into an even line for the first 21 days. Then the levels of estrogen and progestin plunge during the final 7 days.

Limited research suggests that compared with women who don’t use hormonal birth control, those who do are more likely report feeling depressed, anxious, and angry. But those symptoms don’t make the list of common side effects. Other studies have turned up no significant link between hormone combinations or concentrations and differences in mood. Still more research has found that women on the pill and those taking dummy pills report similar symptoms, suggesting that any effects they noticed were unrelated to the actual pills.

But those symptoms don’t make the list of common side effects. Other studies have turned up no significant link between hormone combinations or concentrations and differences in mood. Still more research has found that women on the pill and those taking dummy pills report similar symptoms, suggesting that any effects they noticed were unrelated to the actual pills.

Benefits

Doctors sometimes prescribe hormonal contraceptives to ease the discomfort that practically every woman notices at one time or another during their monthly periods.

Symptoms of premenstrual syndrome can include:

- Angry outbursts

- Crying spells

- Confusion

- Feeling down or depressed

- Trouble sleeping

- Irritability

- Tender breasts

- Aches and pains

- Bloating or weight gain

- Headache

The FDA has approved a specific type of hormonal birth control pill -- containing drospirenone and ethinyl estradiol -- to treat a more serious form of PMS called premenstrual dysphoric disorder. But the hormones may work better to ease physical symptoms than mood-related ones. It also can take some trial and error for your doctors to hit on the right medication and dosage.

But the hormones may work better to ease physical symptoms than mood-related ones. It also can take some trial and error for your doctors to hit on the right medication and dosage.

Possible Explanations

If scientists can’t firmly connect the dots between birth control hormones and emotional turbulence, why do some women believe there’s a link?

- Greater sensitivity to changes to levels of estrogen and other hormones

- Stress from the need to avoid pregnancy and to take the pill as prescribed

- Heightened perception of possible symptoms among women with existing depression, anxiety, or other mental health conditions

When to See a Doctor

If your mood swings are mild or moderate, exercise, healthier eating, relaxation, and other lifestyle changes may bring you relief. See your doctor if you feel depressed, feel no energy, or have other severe symptoms that interfere with your daily life.

Programs to improve birth control in women after childbirth

Most women in the postpartum period do not use birth control methods as they would like. Adolescents often have re-pregnancies within a year [after giving birth]. In earlier work, we found several randomized trials of postpartum family planning education. Here we looked at other types of studies that have tested (tested) ways to improve birth control after childbirth. We wanted to see if any specific programs were associated with increased use of postpartum family planning methods.

Adolescents often have re-pregnancies within a year [after giving birth]. In earlier work, we found several randomized trials of postpartum family planning education. Here we looked at other types of studies that have tested (tested) ways to improve birth control after childbirth. We wanted to see if any specific programs were associated with increased use of postpartum family planning methods.

We conducted a computer search (until November 3, 2014) to identify studies investigating programs to improve family planning for postpartum women. We wrote to the researchers about the missing data. Programs had to provide contacts (relationship) within six weeks after birth. The special program was compared with another (different) program, regular care, or no service/help. Our main outcomes were the use of birth control and pregnancy.

We found six studies including a total of 5143 women. Of the three studies with pregnancy data, two studies showed fewer pregnancies in the treatment group compared to the control group. Programs in those studies included clinical counseling and community education. All studies showed that the special program was associated with higher birth control. In two studies, more women in the treatment group used modern birth control than in the control group. In another study, women in the treatment group were more likely to take the pill or use an IUD (intrauterine device), and less likely to use the injection method. One study assessed how well a birth control method generally works. The methods in the treatment group were rated higher than those in the control group. The IUD-focused study showed more IUD use in the treatment group and less use in the control group. Women participating in the health care program used birth control more frequently than those participating in the population education program or those receiving standard care. Also, women in the health care group were more likely to use the lactation (breastfeeding) method.

Programs in those studies included clinical counseling and community education. All studies showed that the special program was associated with higher birth control. In two studies, more women in the treatment group used modern birth control than in the control group. In another study, women in the treatment group were more likely to take the pill or use an IUD (intrauterine device), and less likely to use the injection method. One study assessed how well a birth control method generally works. The methods in the treatment group were rated higher than those in the control group. The IUD-focused study showed more IUD use in the treatment group and less use in the control group. Women participating in the health care program used birth control more frequently than those participating in the population education program or those receiving standard care. Also, women in the health care group were more likely to use the lactation (breastfeeding) method.

We believe that the data were of very low quality for pregnancy and birth control outcomes. These studies had problems in design, analysis, and reporting. Some of the studies did not adjust for factors that might influence the results. The studies assessed self-reported outcomes [by women] and used different ways to measure outcomes. All studies had a sufficient follow-up period, but in most studies, many women dropped out during the follow-up period.

These studies had problems in design, analysis, and reporting. Some of the studies did not adjust for factors that might influence the results. The studies assessed self-reported outcomes [by women] and used different ways to measure outcomes. All studies had a sufficient follow-up period, but in most studies, many women dropped out during the follow-up period.

Translation notes:

Translation: Ryspekova Saadat Zhoomartbekovna. Editing: Yudina Ekaterina Viktorovna. Russian translation project coordination: Kazan Federal University. For questions related to this translation, please contact us at: [email protected]

For 10 girls 12 boys: how birth control in China led to a shortage of women

79 years old. Forbes Woman reveals how it led to gender imbalance and affected the status of women

Recently it became known that in the next few years, China may remove restrictions on the number of children in families, sources told Reuters. The 2021 census showed that China remains the most populous country in the world and the population continues to grow: now it is 1.41 billion people, but the growth rate has critically slowed down. Birth control led to an aging population and a labor shortage, the cheapness of which has long fueled the growth of the Chinese economy. At the same time, unlike developed countries that faced a similar problem, China “aged before getting rich”: in the list of countries in terms of GDP per capita, it ranks 86th (World Bank data for 2019).year). Another feature of China is that the decline in the population growth rate was created artificially, and superimposed on patriarchal traditions, it gave rise to a gender imbalance.

The 2021 census showed that China remains the most populous country in the world and the population continues to grow: now it is 1.41 billion people, but the growth rate has critically slowed down. Birth control led to an aging population and a labor shortage, the cheapness of which has long fueled the growth of the Chinese economy. At the same time, unlike developed countries that faced a similar problem, China “aged before getting rich”: in the list of countries in terms of GDP per capita, it ranks 86th (World Bank data for 2019).year). Another feature of China is that the decline in the population growth rate was created artificially, and superimposed on patriarchal traditions, it gave rise to a gender imbalance.

The Central Bank of China called for the abandonment of birth control because of the risk of falling behind the United States

Birth control policy

In the early years of the PRC, the birth of several children was encouraged, but then the party's position changed. Birth control was supposed, among other things, to contribute to the modernization of rural areas and reduce the demographic burden of children on the working population. Attempts to introduce such a restriction have been made several times; the current program, known as "one family - one child", started at 1979 year.

Birth control was supposed, among other things, to contribute to the modernization of rural areas and reduce the demographic burden of children on the working population. Attempts to introduce such a restriction have been made several times; the current program, known as "one family - one child", started at 1979 year.

From the very beginning, the program provided exceptions that allowed, under certain conditions, to have a second child. Since the mid-1980s, birth control rules have been at the mercy of provincial administrations, in some of which representatives of national minorities could, without fear of sanctions, give birth to a third.

Despite these exceptions, the birth control policy proved effective, but caused a decline in the working-age population in the first place. At the same time, the life expectancy of the elderly has increased. Expecting lower income levels in retirement, they reduce consumption, which negatively affects the economy.

In 2016, the Chinese government officially allowed all couples to have two children, and local authorities began to turn a blind eye to the "unauthorized" birth of a third. The baby boom, however, did not happen - on the contrary, the birth rate began to fall (in 2020 - by 15%). In March of this year, experts from the Central Bank of China published a report in which they called for the abolition of the current birth restrictions - otherwise, the goals outlined in the plan for socialist modernization by 2035 will not be achieved.

- Pensioners will bring growth: how the pension reform and low birth rate created the prerequisites for a jump in the Russian economy women

The birth control policy was also presented as a logical consequence of the changing status of women and indeed gave many of them additional time to work. Sociologists Yingqi Wang and Tao Liu cite the following data: among mothers who have children under the age of five, 51.

1% work (46.1% do not work, 2.8% are registered as unemployed), while among women , who do not have children of this age, have been working for 59.4% (37% do not work, 2.7% are registered as unemployed). It is paradoxical, however, that under the current birth control policy, a woman who has given birth to an “extra” child can be fired (not to mention the fact that fertility regulation in itself is a restriction on women’s reproductive rights). In addition, all the benefits of childlessness are “eaten up”, firstly, by the growing cost of maintaining even an only child, and secondly, by unpaid housework.

1% work (46.1% do not work, 2.8% are registered as unemployed), while among women , who do not have children of this age, have been working for 59.4% (37% do not work, 2.7% are registered as unemployed). It is paradoxical, however, that under the current birth control policy, a woman who has given birth to an “extra” child can be fired (not to mention the fact that fertility regulation in itself is a restriction on women’s reproductive rights). In addition, all the benefits of childlessness are “eaten up”, firstly, by the growing cost of maintaining even an only child, and secondly, by unpaid housework. In China, traditional values are still strong, which imply that a man is a breadwinner, and a woman is a mother and a housewife. In a report released in 2004, the State Council of China explicitly acknowledged that "the customs of inequality between men and women, inherited from China's history and culture, have not yet been completely eradicated." The idea that “men should be turned to society, and women to the family” in 2010 was shared by 61.

6% of men and 54.8% of women. Chinese women spend an average of 237 minutes a day on unpaid housework, while men spend only 94 minutes (data from the International Labor Organization for 2018).

6% of men and 54.8% of women. Chinese women spend an average of 237 minutes a day on unpaid housework, while men spend only 94 minutes (data from the International Labor Organization for 2018). This work includes caring for elderly relatives - and as China's population ages, the burden on women of working age will increase. At the same time, patrilocality is preserved in some rural areas - that is, a woman, when she marries, moves to her husband's family, and her parents are left without support in old age. This, and the social privileges enjoyed by men, make sons more desirable than daughters. So much so that one of the exceptions to the one-child rule mentioned above allowed rural families to have a second child if the first child was a girl.

Gender imbalanceIn the mid-1990s, sociologist Ansley Cole drew attention to the fact that Chinese women were too few compared to men. The normal sex ratio for any human population at birth is 100 girls to 105 boys; for other age groups, it may vary depending on mortality rates.

Comparing data from various censuses since the beginning of the 20th century, Cole found that the shortage of women in China is characteristic of all age groups, including infants - in other words, many girls are either not born or die shortly after birth. If at 19In 1979, 106 boys were born for every 100 girls, then in 1990 - 111 boys.

Comparing data from various censuses since the beginning of the 20th century, Cole found that the shortage of women in China is characteristic of all age groups, including infants - in other words, many girls are either not born or die shortly after birth. If at 19In 1979, 106 boys were born for every 100 girls, then in 1990 - 111 boys. “The rate of excess early female mortality (probably infanticide) dropped sharply during the communist period, but not to zero,” writes Cole. "The recent rise in the number of 'missing' girls in China is largely driven by the rapid rise in selective abortions." Simply put, expectant couples make the decision to terminate the pregnancy if they find out they are having a daughter.

In addition, newborn girls in rural areas have less access to health care than boys. The result is high infant mortality. “When a son is sick, parents react faster and spend significant resources on his treatment,” writes sinologist Isabelle Attane.

“When their daughter is sick, they hesitate to consult a doctor or take the child to the hospital and, on average, spend less on medical care than on their son.”

“When their daughter is sick, they hesitate to consult a doctor or take the child to the hospital and, on average, spend less on medical care than on their son.” Today, the male population of China exceeds the female population by more than 30 million. Among people aged 20-24, for every 100 women, there are 114.6 men, among people aged 15-19, 118.4 men, among people aged 10-14 years old - 119 men. As today's teenagers mature, this imbalance will become more pronounced.

Marriage marketThe most obvious consequence of the surplus of men is the shortage of potential wives in the marriage market. Some researchers believe that this position increases the value of the latter and enables them to marry men of higher status. Others note that in this case, within the family, gender inequality is reinforced by social inequality. In addition, as Isabelle Attane suggests, with a shortage of brides, men will have to wait longer for the opportunity to marry, while women will be “snapped up”, which will result in a large number of couples with a large difference in age.

All this, in theory, can worsen the position of a married woman, secure her the role of a housewife and limit her economic independence.

All this, in theory, can worsen the position of a married woman, secure her the role of a housewife and limit her economic independence. At the same time, the number of men who will never get married is growing. In China, they are called "guanggun" - "bare branches". Political scientists Valerie Hudson and Andrea der Boer suggested in 2002 that this would lead to an upsurge in violence as the “bare branches” would seek to seize resources that would enable them to compete equally in the marriage market: “These theoretical predictions are supported by empirical evidence. [...] Regardless of cultural background, the vast majority of violent crime is committed by young, low-status unmarried men.” The authors of a study published in 2011 write that they found "no evidence that [single men] are prone to aggression or violence, nor reports of crime and disorder in areas known to have a high male presence." But they note that the “bare branches”, as a rule, have low self-esteem, they are closed and prone to depression.

However, the attitude towards marriage in China, especially in the cities, is changing: many young people deliberately refuse it. In 2018, 10.14 million marriages were registered in China, in 2019 - 9.27, in 2020 - 8.1 million. But the number of divorces is growing: if in 1987 580,000 in 2020 - already more than 3 million, their share over the same period increased from 0.5% to 3.4%. According to the All-China Women's Federation, 70% of divorces are initiated by wives.

The lack of potential partners has led to the flourishing of sex trafficking. Most often, its victims are women from disadvantaged regions - North Korea, Myanmar and others. Traveling to China to earn money, they end up in the hands of brokers who sell them into slavery. The authors of the Human Right Watch report directly point to gender imbalance as the reason for the high demand for sex slaves. Some of the women survivors of sex slavery they interviewed said they were raped in order to conceive a child.

Children are either used as a way to keep a slave girl from escaping, or have value of their own - some HRW informants said they were ready to be released into the wild on the condition that the child remained in a Chinese family. At the same time, children born to illegal migrants are not officially registered, they do not have access to education and healthcare. According to various estimates, there are now about 30,000 “non-existent” children in the country.

Children are either used as a way to keep a slave girl from escaping, or have value of their own - some HRW informants said they were ready to be released into the wild on the condition that the child remained in a Chinese family. At the same time, children born to illegal migrants are not officially registered, they do not have access to education and healthcare. According to various estimates, there are now about 30,000 “non-existent” children in the country. - Love in South Korea: how they build relationships and treat marriage here

- “There is nothing worse than a bad marriage”: Lyudmila Ulitskaya — about love, low self-esteem and life in conditions of uncertainty

- Not long and unfortunate: why married people get no more pleasure from life than single and free

How to get out of the demographic holeAccording to Reuters, the Chinese authorities are considering a broad plan to solve demographic problems, which will include effective ways to encourage childbearing, as well as a program raising the retirement age.

However, this is unlikely to give a quick effect: the policy of "one family - one child" has led not only to a reduction in the birth rate, but also to the fact that now there is simply no one to increase it.

However, this is unlikely to give a quick effect: the policy of "one family - one child" has led not only to a reduction in the birth rate, but also to the fact that now there is simply no one to increase it. They try to solve the problem in different ways. For example, back in the early 2000s, the National Population and Family Planning Commission launched the Care for the Girls campaign, which tried to add value to daughters. The authorities are also fighting the practice of selective abortions, but since there are not many ways to separate them from other cases of abortion, the measures are limited to limiting the ability to have an abortion after the 14th week of pregnancy - this is the period when the sex of the unborn child can be determined.

Another direction is the preservation of the institution of marriage. For example, since January 1, 2021, a law has been in force in China, according to which a divorce application must be filed twice with a difference of a month - it is assumed that during this time the couple may change their mind about divorcing.

Learn more